Abstract

Genes for superoxide reductase (Sor), rubredoxin (Rub), and rubredoxin:oxygen oxidoreductase (Roo) are located in close proximity in the chromosome of Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. Protein blots confirmed the absence of Roo from roo mutant and sor-rub-roo (srr) mutant cells and its presence in sor mutant and wild-type cells grown under anaerobic conditions. Oxygen reduction rates of the roo and srr mutants were 20 to 40% lower than those of the wild type and the sor mutant, indicating that Roo functions as an O2 reductase in vivo. Survival of single cells incubated for 5 days on agar plates under microaerophilic conditions (1% air) was 85% for the sor, 4% for the roo, and 0.7% for the srr mutant relative to that of the wild type (100%). The similar survival rates of sor mutant and wild-type cells suggest that O2 reduction by Roo prevents the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) under these conditions; i.e., the ROS-reducing enzyme Sor is only needed for survival when Roo is missing. In contrast, the sor mutant was inactivated much more rapidly than the roo mutant when liquid cultures were incubated in 100% air, indicating that O2 reduction by Roo and other terminal oxidases did not prevent ROS formation under these conditions. Competition of Sor and Roo for limited reduced Rub was suggested by the observation that the roo mutant survived better than the wild type under fully aerobic conditions. The roo mutant was more strongly inhibited than the wild type by the nitric oxide (NO)-generating compound S-nitrosoglutathione, indicating that Roo may also serve as an NO reductase in vivo.

Desulfovibrio spp. are anaerobically living, sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) that generate energy via dissimilatory sulfate reduction in the absence of air. Nevertheless, because Desulfovibrio spp. may be periodically exposed to air in their natural environment, they have evolved oxygen survival strategies. Completion of the genome sequence (18) has indicated that D. vulgaris Hildenborough has genes for oxygen reductases, including those for membrane-bound cytochrome c oxidase (Cox, DVU1811-1815) and cytochrome bd oxidase (Cbd, DVU3270-3271) and cytoplasmic rubredoxin:oxygen oxidoreductase (Roo, DVU3185); genes for inactivation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), including those for superoxide dismutase (Sod, DVU2140), catalase (DVUA0091), superoxide reductase (Sor, DVU3183), and rubrerythrins Rbr1 (DVU3094), Rbr2 (DVU2310), and Ngr (DVU0019); and genes for oxygen chemotaxis (13, 33), including those for DcrA (DVU3182) and DcrH (DVU3155). The importance of D. vulgaris Sor has been demonstrated by comparing the survival of a sor mutant with that of the wild type upon incubation in air-saturated medium (11, 21, 31). The genome sequence has indicated that roo is immediately downstream from the sor-rub operon, encoding Sor (formerly referred to as rubredoxin oxidoreductase [Rbo]; 3) and rubredoxin (Rub, DVU3184). Roo has been proposed to be the terminal oxidase of a cytoplasmic, non-energy-conserving chain (8, 12), whereas the function of Sor as an enzyme that inactivates superoxide by reduction to H2O2 has been firmly established (9, 19). The adjacent localization of the sor-rub and roo genes suggests that Rub may serve as an electron carrier in both the Sor- and Roo-catalyzed reactions (5, 12, 15).

Silaghi-Dumitrescu et al. (27) referred to D. vulgaris Roo as a flavodiiron protein (FprA) in recent biochemical studies, which indicated that the purified enzyme serves more efficiently as a nitric oxide (NO) than as an O2 reductase in vitro. Because transformation of plasmids harboring D. vulgaris or Moorella thermoacetica fprA (roo) into an Escherichia coli norV mutant protected the recombinant E. coli against inactivation by exogenous NO, these authors suggested that D. vulgaris Roo (FprA) functions as an NO and not as an O2 reductase in vivo. Further testing of this suggestion must include the study of a D. vulgaris roo mutant. The construction of such a mutant and its physiological properties are reported here.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Reagent grade chemicals were from BDH, Fisher, or Sigma. Restriction and DNA modification enzymes and bacteriophage λ DNA were from Pharmacia. Mixed gases (10% [vol/vol] CO2, 5% H2, balance N2; 10% CO2, 0.2% O2, balance N2; NO) were obtained from Praxair Products Inc. Deoxyoligonucleotide primers were from University Core DNA Services of the University of Calgary.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli and D. vulgaris strains were grown as described elsewhere (13, 16).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, vectors, and primers used in this study

| Strain, plasmid(s), primer, or vector | Genotype, phenotype, comment(s), reference, or sequence |

|---|---|

| Strains | |

| D. vulgaris subsp. vulgaris strain Hildenborough | NCIMB 8303; isolated from clay soil near Hildenborough, United Kingdom; 22 |

| D. vulgaris L2 | Δsor; Sucr Cmr; 31 |

| D. vulgaris ROO100 | Δroo; Sucr Cmr; this study |

| D. vulgaris SRR100 | Δsor-rub-roo; Sucr Cmr; this study |

| E. coli S17-1 | thi pro hsdR hsdM+recA RP4-2 (Tc::Mu Km::Tn7); 28 |

| Plasmids and vectors | |

| pUC19Cm | pUC19 containing the Cm gene; 13 |

| pNOT19 | Cloning vector pUC19; NdeI site replaced with NotI site; 24 |

| pMOB2 | Contains oriT of plasmid RP4 and B. subtilis sacBR genes on a 4.5-kb NotI fragment; Kmr Cmr; 24 |

| pNOT212/214, pNOTΔroo, pNOTΔrooCm, pNOTΔrooCmMob | This study |

| pNOT-SR, pNOTΔSR, pNOTΔSRCm, pNOTΔSRCmMob | This study |

| Primers | |

| p212-f | 5′-cccctgcagCCGTCGGTTCCGTGGCCCACC (187 to 207)a |

| p213-r | 5′-cccggtaccTGGCGCACGCCCGTGGTGTGG (2372 to 2392) |

| p214-r | 5′-cccggatccGGGTTCCTCGTGTGTTGCGCG (666 to 686) |

| p215-f | 5′-cccggatccTAGCTGACGCTACGCATCGTC (1893 to 1913) |

| p242-f | 5′-ggggctgcaGCCCAGAGGCTTGAGGCCCTC (−382 to −362) |

| p120-r | 5′-cccggatccCTTTTCCTTGGCCCCGTCAGA (123 to 143) |

| p122-f | 5′-ccgaattcatATGCCCAACCAGTACGAAATC (1 to 21) |

| p123-r | 5′-cccggatccCATCGTGGATTCCTCGGGGTT (379 to 399) |

Positions relative to the sor coding region (bp +1 to +378). Lowercase letters are bases added to create restriction endonuclease cleavage sites.

Construction of roo and sor-rub-roo mutants.

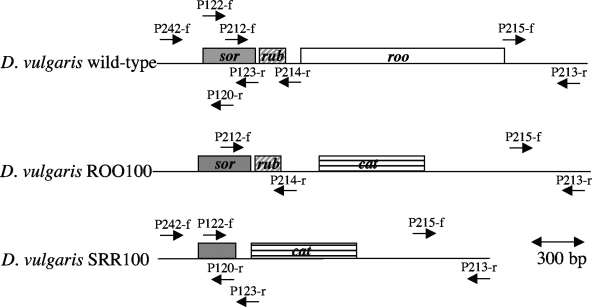

The 500-bp region upstream from roo was PCR amplified with primers p212-f and p214-r, cleaved with PstI and BamHI, and ligated to similarly digested pNOT19 to generate pNOT212/214. The 500-bp region downstream from roo was amplified with p215-f and p213-r, digested with BamHI and KpnI, and ligated to similarly cleaved pNOT212/214 to generate pNOTΔroo. Insertion of the cat gene-containing BamHI fragment from pUC19Cm into pNOTΔroo gave pNOTΔrooCm, and insertion of the 4.5-kb NotI fragment from pMOB2 gave pNOTΔrooCmMob. The latter was transferred to D. vulgaris by conjugation with E. coli S17-1 on fumarate-containing medium E plates containing chloramphenicol (CM) and kanamycin as described elsewhere (13, 16). A selected single-crossover integrant was grown in the presence of sucrose and CM to obtain the roo gene replacement mutant D. vulgaris ROO100 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Maps of the sor-rub-roo region of the wild type and the ROO100 (roo) and SRR100 (srr) mutants. The hybridization positions of primers p212-f, p213-r, p214-r, p215-f, p120-r, p122-f, p123-r, and p242-f and the locations of the sor, rub, roo, and cat genes are indicated. The scale of 300 bp applies to all of the maps. A map of the sor mutant has been shown elsewhere (31). Relative to the start of the sor coding region (+1), SalI sites yielding a DNA fragment hybridizing with the p212f and p214r or p122f and p123r labeled probes are present at positions −546 and +547 (wild type), −546 and +4500 (roo mutant), and −546 and +3957 (srr mutant).

For construction of the sor-rub-roo mutant, a 2.8-kb fragment was PCR amplified with primers p242-f and p213-r (Fig. 1), cleaved with PstI and KpnI, and ligated to similarly cut plasmid pNOT19 to give plasmid pNOT-SR. PCR with primers p215-f and p120-r and religation gave pNOTΔSR, in which part of the sor gene and all of the rub and roo genes were deleted. Insertion of the cat gene-containing BamHI fragment from pUC19Cm into pNOTΔSR gave pNOTΔSRCm, and insertion of the 4.5-kb NotI fragment from pMOB2 gave pNOTΔSRCmMob. Conjugal transfer of the latter to D. vulgaris gave a single-crossover integrant, from which the desired gene replacement mutant (D. vulgaris SRR100; Fig. 1) was selected by growth on sucrose and CM.

Southern blotting and PCR analysis for genotypic verification.

PCR with primers p212-f and p213-r or primers p242-f and p213-r was done to confirm the genotype of the ROO100 and SRR100 strains, respectively. These were also confirmed by Southern blot analysis with PCR fragments obtained with p212-f and p214-r or with p122-f and p123-r as probes, respectively. Probes were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP by the random-hexamer procedure, and probe hybridization was visualized with a Fuji BAS1000 Bioimaging Analyzer.

Anaerobic culturing.

Cultures of the wild-type or mutant strains were grown in sidearm flasks containing 50 ml of medium C (21) in an anaerobic hood (Forma Scientific Inc. or Coy Laboratory Products Inc.) equipped with a constant-temperature incubator and a Klett meter (Manostat Corp.) allowing monitoring of growth of liquid cultures without their removal from the anaerobic atmosphere. Cultures were grown to mid-log phase (40 to 70 Klett units; 150 Klett units corresponds to an optical density at 600 nm of 1) in 85% (vol/vol) N2, 10% CO2, and 5% H2 at 32°C before use.

Protein blotting.

Purified Roo and polyclonal antibodies against Roo generated in rabbits (27) were kindly provided by Don Kurtz, Jr., University of Georgia. Cultures (10 ml) of D. vulgaris wild-type and sor, roo, and srr mutant strains were grown in medium C, collected by centrifugation, resuspended in 400 μl of sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer, and boiled for 10 min. The samples were then run on 12.5% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels. Immunoblotting and immunodetection of Roo were done according to standard procedures (31), with a 1:1,000 dilution of the primary antibody and an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody as the secondary antibody.

ORRs.

Oxygen reduction rates (ORRs) were measured with a Yellow Springs Instrument model 5300 biological oxygen monitor with Clark-type polarographic oxygen probes. Cultures (50 ml) were grown in medium C to mid-log phase. The cell density was recorded, and 35 ml was then transferred into a closed centrifuge tube and centrifuged for 15 min at 9,000 rpm in a Sorvall RC-5B centrifuge. Medium C has lactate (38 mM) as the electron donor for reduction of sulfate (32 mM) and also contains 1 g/liter yeast extract. The centrifuge tubes were then returned to the anaerobic hood, where the pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of medium C. The concentrated cell suspension was placed in a glass vial sealed with a rubber stopper and kept at room temperature. Air-saturated medium C (3 ml) was added to the magnetically stirred sample chamber of the oxygen monitor, and the oxygen sensor was inserted into the chamber, excluding all air. The monitor was calibrated by removing all oxygen with excess (2 mg) sodium dithionite. ORRs were determined by injecting 100 μl of cell suspension into the chamber and recording the oxygen concentration for at least 10 min. Because the ORR often decreased in the first few min of recording, ORRs were calculated from the tangents drawn at 4 min. In a typical experiment, the ORR of the wild type was recorded within 5 min after the cells were resuspended (t = 0) and then again at 60 and 120 min. ORRs of the sor mutant were measured at 15, 75, and 135 min, those of the roo mutant were measured at 30, 90, and 150 min, and those of the srr mutant were measured at 45, 105, and 165 min. The ORRs of the mutant strains at 120 min were interpolated from the data obtained. The specific ORR (micromoles of O2 per minute per milligram of dry biomass) was calculated by dividing by the cell density of the culture before centrifugation in Klett units (147 Klett units = 1 U of optical density at 600 nm = 0.309 mg of biomass [dry weight]/ml). Specific ORRs were the averages of three to five independent experiments. The specific ORR of the wild type was also measured with medium C containing 3.0 mM acetate and no lactate. Note that D. vulgaris oxidizes lactate incompletely (H2O + lactate → acetate + CO2 + 4H+ + 4e). Acetate is used as a carbon source, not as an electron donor.

ORRs were also determined in defined Widdel-Pfennig medium (WP) lacking yeast extract. WP-lactate contained 38 mM lactate and 28 mM sulfate (32). Cultures were grown, washed by centrifugation, and resuspended in WP-lactate as for medium C. The sample chamber of the oxygen monitor was filled with 3 ml of WP-lactate in these experiments. The ORR of the wild type was also measured with cells washed with and suspended in WP-acetate (3.0 mM acetate; no lactate), i.e., in the absence of an exogenous electron donor.

Exposure to 1% (vol/vol) air.

Aliquots (1 ml) of cultures grown in 50 ml medium C to mid-log phase were anaerobically diluted in 100 ml of medium C in 250-ml Erlenmeyer flasks fitted with a sampling port closed with a butyl rubber stopper. The flasks were closed with rubber stoppers fitted with a glass tube (inner diameter, 4 mm) reaching to the bottom. These were connected to a cylinder of 10% (vol/vol) CO2, 0.2% O2 (equivalent to 1% air), and a balance of N2. A needle was inserted into the rubber stopper, and the gas flow was adjusted to 150 ml/min per flask. Samples were withdrawn periodically through the sampling port. N0 and Nt (CFU per milliliter) were determined as described for incubation with 100% (vol/vol) air below.

Incubation on plating medium under microaerophilic conditions.

Appropriate dilutions of the wild-type and mutant strains, corresponding to 102 to 104 CFU in 100 μl, were plated in duplicate (the air-exposed set and the anaerobic control set) on medium E plates (22) in the anaerobic hood. The sets were placed in separate 2-liter steel jars (Torbal model AJ-3; The Torsion Balance Co.) closed with a steel lid modified to allow air injection through butyl rubber stoppers. Following injection of 20 ml of air into the jar, containing the air-exposed set, the jars were incubated for 5 days in the anaerobic hood at room temperature. The jars were then opened, and the plates were placed in a 32°C incubator under anaerobic conditions for another 5 days. Colonies, representing cells that survived the 5 days of exposure to 1% (vol/vol) air or that grew in the control set were then counted as Nair and Nanaerobic, respectively. The fraction of mutant, relative to wild-type, survivors was calculated as F = [(Nair/Nanaerobic)mutant]/[(Nair/Nanaerobic)wild type] × 100%.

Exposure to 100% (vol/vol) air.

A 10-μl aliquot of mid-log-phase cultures was diluted 104-, 105-, 106-, and 107-fold, and 100 μl of these dilutions was spread on medium E plates to determine the viable cell count prior to air exposure (N0) in CFU per milliliter. Aliquots of 0.5 ml were then diluted into 50 ml of air-saturated medium C in 250-ml Erlenmeyer flasks, which were continually shaken in air on an orbital shaker at 60 rpm at room temperature. At various times t (0 < t < 72 h), 100-μl aliquots of these air-exposed, diluted suspensions were transferred back to the anaerobic hood, serially diluted, and plated on medium E. Nt, the surviving number of CFU per milliliter after t hours, was determined by counting colonies following 5 days of anaerobic incubation at 32°C.

NO sensitivity of the wild type and the roo mutant.

Aliquots (100 μl) of mid-log-phase cultures in medium C were spread evenly onto medium C plates with a glass spreader. Paper disks (Schleicher & Schuell no. 740-E special-purpose filter paper; diameter = 12.7 mm) were then placed in the center of the plates and 30 μl of 100, 75, 50, 25, or 0 mM S-nitrosoglutathione was applied. Following 3 days of anaerobic incubation at 30°C, the zones of inhibition were traced and transposed to weighing paper (VWR Scientific). The inhibited surface area was measured by cutting and weighing.

RESULTS

Verification of genotype of marker replacement mutants.

Amplification of wild-type and ROO100 DNA with primers p212-f and p213-r gave 2.2-kb and 2.4-kb PCR products, respectively, confirming replacement of roo with the cat gene marker (results not shown). Hybridization of Southern blots of SalI-digested genomic DNAs with a labeled p212-f-p214-r amplicon as the probe indicated bands of 1.1 kb for the wild type, of 8.6 and 1.1 kb for the single-crossover integrant, and of 5.0 kb for the ROO100 replacement mutant, in agreement with the expected restriction maps (results not shown). Amplification of wild-type and SRR100 DNAs with primers p242-f and p213-r gave 2.8-kb and 2.4-kb PCR products, confirming replacement of the sor-rub-roo genes with the smaller cat gene (results not shown). SRR100 and wild-type DNAs displayed hybridizing SalI fragments of 4.5 kb and 1.1 kb, respectively, when Southern blots were hybridized with the labeled PCR product obtained with primers p122-f and p123-r (results not shown).

Protein blotting.

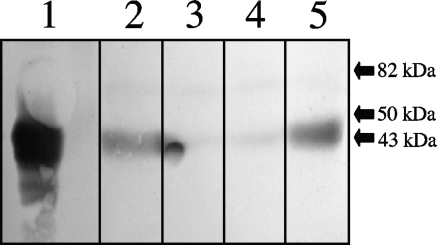

Protein blotting indicated that, in anaerobically grown cultures, the Roo protein is present in wild-type and sor mutant cells (Fig. 2, lanes 2 and 5), whereas it is absent from roo and srr mutant cells (Fig. 2, lanes 3 and 4). Hence, insertion of the cat marker into the sor gene did not eliminate the expression of roo, indicating that this gene is transcribed independently of its own promoter and/or the cat promoter, which is oriented correctly for this purpose (31). The content of Roo did not change significantly upon aeration of wild-type cells (results not shown).

FIG. 2.

Protein blot of purified Roo (lane 1) and total cell extracts of the D. vulgaris wild-type (lane 2), roo mutant (lane 3), srr mutant (lane 4), and sor mutant (lane 5) strains probed with anti-Roo polyclonal antibodies. The positions of three molecular mass markers are shown. Native Roo is a dimer of 43-kDa subunits.

Oxygen reduction rates.

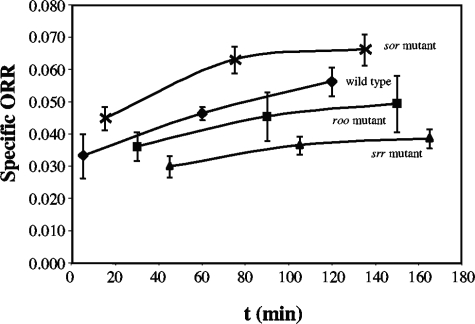

When concentrated cell suspensions of wild type or mutant D. vulgaris Hildenborough were kept in stoppered vials at room temperature, their ORRs increased as a function of time (Fig. 3). Because this increase was substantial (on average, 30% in 2 to 3 h), it was essential that the time dependence of ORR be determined and that data be reported for the same time elapsed since preparation of the cell suspension. In order to be able to average results from different experiments, we adhered to a strict measuring schedule, as described in Materials and Methods. The resulting data (Fig. 3), averaged from three to five independent experiments, were used to determine the ORR at 2 h, where the rate of increase had slowed down in most cases. Kjeldsen et al. also reported ORRs for D. desulfuricans cell suspensions stored under anaerobic conditions at room temperature for 2 h (20).

FIG. 3.

Change in the specific ORRs (micromoles of O2 per minute per milligram of dry biomass) of the wild-type and roo, sor, and srr mutant strains with time. These data were used to obtain the specific ORRs at 2 h.

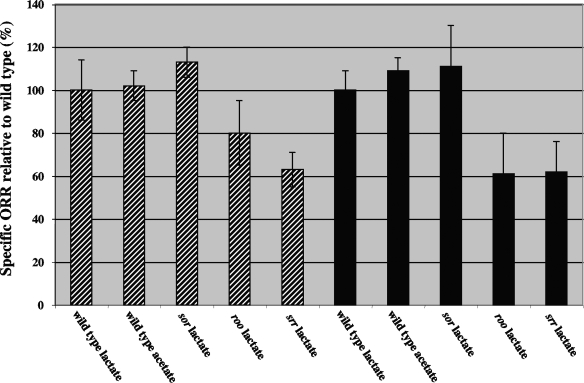

Using these precautions, we were able to show that deletion of roo decreases the specific ORR. Relative to that of the wild type in medium C (specific ORR = 0.058 μmol min−1 mg−1; 100% ± 14%; n = 4), the specific ORR was 80% ± 15% for the roo mutant (n = 3) and 63% ± 8% for the srr mutant (n = 3). Surprisingly, the sor mutant had a higher specific ORR of 113% ± 7% (n = 5) relative to the wild type. The ORR of wild-type cells resuspended in medium C with acetate was very similar to that obtained with lactate (Fig. 4, 102% ± 7%; n = 5).

FIG. 4.

Specific ORRs of mutants relative to the wild type (100%) in either medium C (hatched bars) or WP medium (solid bars). Data for the wild type in medium C or in WP with lactate or acetate are shown.

The time dependence of ORRs was also measured in defined medium lacking yeast extract, and specific ORRs were similarly calculated for cells 120 min after resuspension. Wild-type cells in WP-lactate had a specific ORR that was slightly lower than that in medium C with lactate, i.e., 0.054 μmol min−1 mg−1. Relative to that of the wild type (100% ± 18%; n = 5), the specific ORRs of wild-type cells in WP-acetate or in WP without lactate or acetate were 110% ± 7% (n = 2) and 100% ± 16% (n = 2), respectively. Hence, the ORRs of wild-type cells were comparable, irrespective of whether the cells had been grown in WP-lactate or in medium C-lactate and were resuspended in the same medium with lactate or acetate or without either. These results suggest that externally added lactate is not used as an electron donor for oxygen reduction.

Compared to that of the wild type (100% ± 17%; n = 5), the ORRs of the mutants in WP-lactate were 111% ± 19% for the sor mutant (n = 5), 61% ± 19% for the roo mutant (n = 5), and 62% ± 14% for the srr mutant (n = 5), as shown in Fig. 4. Hence, the absence of Roo from the cytoplasm led to a 20 to 40% reduction in the specific ORR relative to that of the wild type. The increased specific ORR of the sor mutant points to increased expression of roo from the cat promoter, which is located upstream. A dcrA mutant in which the cat gene was inserted upstream of sor had increased expression of the sor gene (13, 31). This caused increased survival under fully aerobic conditions (13), the expected phenotype of a Sor-overexpressing strain.

Survival under microaerophilic conditions.

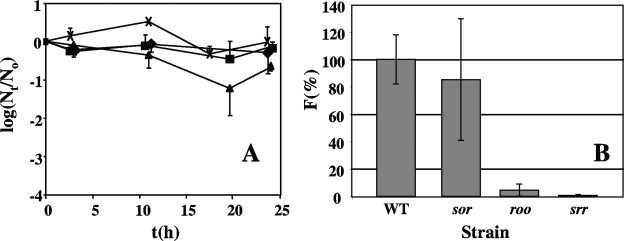

A gas mixture of 90% (vol/vol) N2, 10% CO2, and 0.2% O2 (corresponding to the O2 concentration in 1% air) was continuously bubbled at a flow rate of 150 ml/min through 100-fold-diluted cultures in medium C. The oxygen input into the culture (12 μmol O2/min) exceeds the estimated ORR (0.006 μmol O2/min) by 2,000-fold, which should be sufficient to maintain a constant dissolved-oxygen concentration. No significant increase in (i.e., growth) or loss of viable wild-type cells was observed under these conditions during 24 h. The doubling time of D. vulgaris in this medium under anaerobic conditions is 4.6 h. Hence, Nt would have increased by 1 to 2 log units had growth occurred. The roo and sor mutants were also not strongly affected, whereas the viable-cell numbers of the srr mutant appeared to decrease about 10-fold (Fig. 5A). Determining survival of cells spread on plates was found to be a more reliable method for long-term incubation in 1% (vol/vol) air. Because the exposed biomass is extremely small in these experiments (104 to 105 cells), little oxygen is reduced and the oxygen concentration in the 2-liter steel jars is constant, even for long incubation times. No growth of cells into colonies was observed following 5 days of incubation at room temperature in 1% (vol/vol) air, whereas the similarly incubated anaerobic controls had slight growth. Following 5 more days of anaerobic incubation at 32°C, colonies were counted. The survival of wild-type cells, relative to that of the anaerobic control, was 30.6% ± 3.4%. Relative to the wild type (100% ± 11%), the sor mutant survived much better (85.4% ± 44.4%) than the roo mutant (4.5% ± 4.5%) and the srr mutant (0.7% ±0.7%). These results (Fig. 5B) suggest that Roo is effective in removing oxygen that diffuses into the cytoplasm under these conditions, preventing ROS formation. Sor is only important when Roo is absent; i.e., the srr mutant has a sixfold-decreased survival rate relative to that of the roo mutant.

FIG. 5.

Survival of D. vulgaris wild-type (WT) and mutant strains under microaerophilic conditions. (A) Survival in liquid cultures bubbled with 150 ml/min of 1% (vol/vol) air. The fraction of surviving cells (logNt/N0) is plotted against time t (h) for the wild-type (closed diamonds) and roo mutant (closed squares), sor mutant (crosses), and srr mutant (closed triangles) strains. The data shown are averages of three or four independently conducted experiments; standard errors from the mean are shown. (B) Survival of single cells on plates following incubation in 1% (vol/vol) air for 5 days. Survival was calculated as the fraction (F) of surviving cells relative to the wild type (100%). The actual survival of the wild type in 1% (vol/vol) air relative to anaerobic conditions was 30.6% ± 3.4%. The standard errors of the means are for three independently conducted experiments.

Exposure to 100% (vol/vol) air.

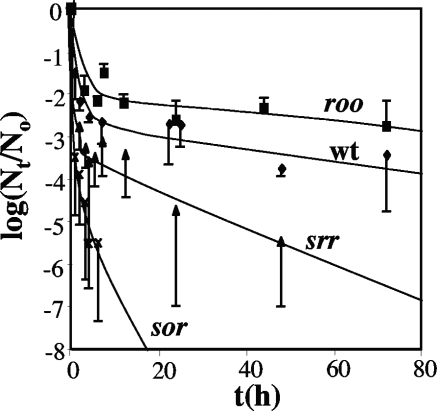

The transfer of anaerobic log-phase cells to fully aerated conditions (verified by direct measurement with an oxygen electrode) gave biphasic inactivation kinetics, in which 99 to 99.9% of the cells died rapidly (e.g., for the wild type within 10 h), after which the remaining viable cells died more slowly (Fig. 6). The first-order inactivation rate constant k (h−1) at the beginning (t = 0) and at the end of the experiment decreased from 0.66 to 0.012 h−1 for the wild type, from 0.36 to 0.006 h−1 for the roo mutant, from 3.0 to 0.25 h−1 for the sor mutant, and from 1.3 to 0.045 h−1 for the srr mutant. Values for k of the same order of magnitude, 0.083 and 0.272 h−1 for the wild type and the sor mutant, respectively, were found previously (9). It should be pointed out that in these previous studies, these represented averages for both inactivation phases and for both log-phase and stationary-phase cells. Hence, log-phase sor mutant cells were the most oxygen sensitive; of the viable-cell concentration of 106 to 107 CFU/ml at the start of the experiment, no surviving cells remained after 10 h (Fig. 6). In contrast, the roo mutant was the least oxygen sensitive, outliving the wild type by approximately 1 order of magnitude at 72 h. Because the srr mutant was significantly more resistant than the sor mutant and the roo mutant was more resistant than the wild type (Fig. 6), it appears that removal of roo increases survival under fully aerobic conditions.

FIG. 6.

Loss of cell viability (logNt/N0) with time t (hours) upon exposure of liquid cultures to 100% (vol/vol) air. Data are presented for the wild type (wt), as well as for the roo, sor, and srr mutants, as indicated. Data are averages for three or four independently conducted experiments; standard errors of the means are also shown.

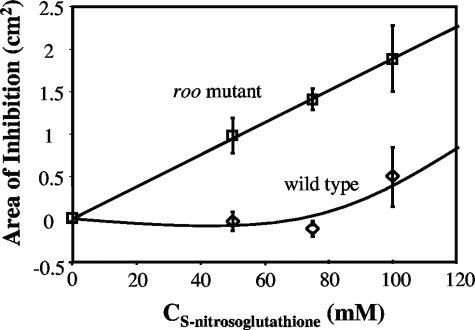

Exposure to S-nitrosoglutathione.

The roo mutant was more sensitive to the NO-releasing compound S-nitrosoglutathione than was the wild type, as judged by disk diffusion assays in two independently conducted experiments, of which one is shown in Fig. 7. The results indicate that, in addition to serving as an O2 reductase, Roo contributes to NO reduction. However, it should be pointed out that no difference was observed in the survival of D. vulgaris wild-type and roo mutant strains when liquid culture dilutions were exposed to 0.001 to 1% (vol/vol) NO injected directly into the headspace (results not shown).

FIG. 7.

Disk diffusion assay of inhibition of D. vulgaris wild-type and roo mutant strains by various concentrations of the NO-generating agent S-nitrosoglutathione. S-Nitrosoglutathione (30 μl of the indicated concentration) was added to a paper disk placed on a plate spread with 100 μl of exponentially growing wild-type or roo mutant cells. Following incubation for 3 days at 32°C, the inhibition zones surrounding the disks were quantitated. Duplicates were done for each concentration and strain.

DISCUSSION

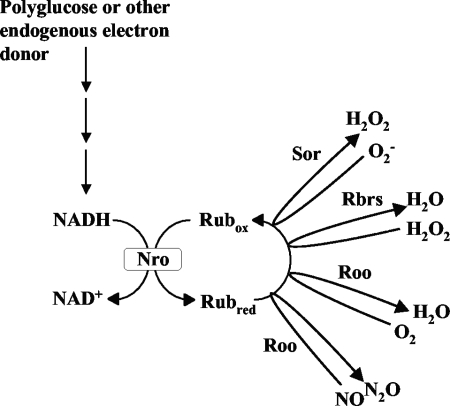

The existence of a cytoplasmic, oxygen-reducing electron transport chain in D. gigas consisting of NADH:rubredoxin oxidoreductase (Nro), Rub, and Roo (Fig. 8) was first suggested by Chen et al. (4). Although the Roo component of the chain has since been well characterized and appears to be conserved in a wide variety of anaerobic bacteria, much less is known about the Nro component. In M. thermoacetica, the gene for the Roo homolog FprA (locus tag Moth_1287) is flanked by genes for rubrerythrin (Moth_1286) and high-molecular-weight rubredoxin (Hrb; Moth_1288). Hrb, consisting of a flavin mononucleotide-containing N-terminal domain (residues 1 to 163) and a rubredoxin C-terminal domain (residues 164 to 229), transfers electrons from NADH to FprA and thus serves as a combined Nro-Rub in the scheme of Fig. 8. The Hrb-FprA combination has NADH:O2, as well as NADH:NO, oxidoreductase activity (26). The N-terminal Hrb domain, referred to as Fla-Hrb, catalyzes the NADH-dependent reduction of D. vulgaris rubredoxin (27), which in turn supports D. vulgaris Roo-mediated reduction of O2 or NO (Fig. 8). In E. coli, NADH:NO oxidoreductase activity is catalyzed by NorV/NorW. NorV, flavorubredoxin, is FprA (Roo) with an added C-terminal rubredoxin domain. NorW, NADH:flavorubredoxin oxidoreductase, functions as NorV's cognate reductase. Desulfovibrio spp. have a NorW homolog (DVU3212 and Dde0374 in D. vulgaris and D. desulfuricans G20, respectively). The N-terminal Hrb domain is homologous to flavoredoxin (Flr), a 190-amino-acid protein in D. vulgaris and D. desulfuricans G20 (locus tags DVU0384 and Dde0187, respectively), which has been characterized most extensively in D. gigas (1). A D. gigas flr mutant appeared deficient in electron transport from H2 to thiosulfate (2). However, Flr is widely distributed in bacteria that are not dissimilatory sulfate reducers, making an exclusive function of this redox enzyme in dissimilatory sulfite reduction unlikely.

FIG. 8.

Proposed pathway for cytoplasmic oxygen, NO, and ROS reduction in D. vulgaris. NADH resulting from glycolytic breakdown of polyglucose is used by NADH:rubredoxin oxidoreductase (Nro) to reduce the oxidized rubredoxin pool (Rubox). The reduced rubredoxin pool (Rubred) serves as the electron donor for oxygen and NO reduction by Roo for superoxide reduction by Sor and for H2O2 reduction by the rubrerythrins (Rbrs).

The enzyme that functions as Nro in Desulfovibrio spp. is thus unknown. Flr and NorW homologs are candidates. Because of Roo's homology with flavorubredoxin, a known NO reductase in E. coli (7, 14), it has been suggested that the function of Roo in Desulfovibrio spp. is also primarily to reduce NO, not O2. In vitro studies showing that Roo is degraded when it functions as an oxygen reductase, but not as an NO reductase, provided further evidence for this suggestion (27). NO exposure of SRB in the environment could result from the activity of nitrate-reducing, sulfide-oxidizing bacteria, which denitrify nitrate to nitrogen with nitrite, NO, and N2O as intermediates (17). The decreased resistance of the D. vulgaris roo mutant, compared to the wild type, to inactivation by S-nitrosoglutathione is consistent with a function in NO detoxification. However, in contrast to those of Rodrigues et al. (23), who reported no differences between the wild-type and roo mutant strains of D. gigas upon exposure to oxygen, our results also indicate that Roo functions as an O2 reductase in vivo (Fig. 4) and that this activity protects the cell from oxygen inactivation under microaerophilic conditions (Fig. 5). O2 reduction activity by Roo appears to account for 20 to 40% of the total specific ORR of D. vulgaris, which at 54 to 58 nmol O2 min−1 mg of dry biomass−1 (108 to 116 nmol O2 min−1 mg of protein−1) is within the range of specific ORRs reported for SRB (20 to 140 nmol O2 min−1 mg protein−1; 30). Under the conditions of oxygen reduction assays, D. vulgaris is unable to use externally provided lactate as an electron donor for O2 reduction. Glycolytic breakdown of stored polyglucose has been shown to be a source of NADH for O2-, NO-, and ROS-reducing enzymes during oxygen stress in D. gigas (8, 10). D. vulgaris is known to contain enzymes for the synthesis and glycolytic breakdown of polyglucose (18) and has been found to accumulate polyglucose, especially under conditions of ammonium or iron limitation (29). Polyglucose, or another endogenous electron donor, is therefore proposed as the source of NADH used for reduction of the rubredoxin pool, which serves as an electron donor for O2, NO, and ROS (O2− and H2O2) reduction reactions (Fig. 8). Under conditions of air saturation, O2 reduction by Roo does not appear to be as critical for survival as under microaerophilic conditions. In fact, we found, unexpectedly, that survival improves when roo is deleted (Fig. 6). This may indicate that the Roo, Sor, and Rbr proteins compete for a limited pool of reduced rubredoxin under these conditions. Hence, survival of the roo mutant is improved compared to that of the wild type and survival of the srr mutant is improved compared to that of the sor mutant because the limited pool of reduced rubredoxin is targeted more efficiently to ROS reduction in the roo and srr mutants under full air exposure conditions.

SRB do not appear capable of using energy derived from the reduction of O2 for growth (6). Environments like saline cyanobacterial mats, which are periodically exposed to high oxygen concentrations, have been targeted as possible sources of isolates that might be able to switch from growth with sulfate to growth with O2 as the terminal electron acceptor. However, although survival and growth of SRB isolated from these environments in the presence of O2 have been demonstrated in mixed cultures (25), a pure culture capable of growth with O2 at a low biomass concentration (i.e., single cells on plates) in the absence of sulfate has never been obtained. It has been concluded, therefore, that O2 reduction serves a protective function. In SRB, Roo supports that function under microaerophilic conditions in addition to serving as an NO reductase. This dual physiological function of Roo may have evolved into strictly NO reduction in aerobically living bacteria.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a discovery grant from the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada to G.V. J.D.W. was supported by a Province of Alberta Graduate Scholarship and an NSERC graduate scholarship.

We thank Claire Stillwell for technical assistance in NO inactivation studies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agostinho, M., S. Oliveira, M. Broco, M.-Y. Liu, J. LeGall, and C. Rodrigues-Pousada. 2000. Molecular cloning of the gene encoding flavoredoxin, a flavoprotein from Desulfovibrio gigas. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 272:653-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Broco, M., M. Rousset, S. Oliveira, and C. Rodrigues-Pousada. 2005. Deletion of flavoredoxin gene in Desulfovibrio gigas reveals its participation in thiosulfate reduction. FEBS Lett. 579:4803-4807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brumlik, M. J., and G. Voordouw. 1989. Analysis of the transcriptional unit encoding the genes for rubredoxin (rub) and a putative rubredoxin oxidoreductase (rbo) in Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. J. Bacteriol. 171:4996-5004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, L., M.-Y Liu, J. LeGall, P. Fareleira, H. Santos, and A. V. Xavier. 1993. Rubredoxin oxidase, a new flavo-hemo protein, is the site of oxygen reduction to water by the “strict anaerobe” Desulfovibrio gigas. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 193:100-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coulter, E. D., and D. M. Kurtz, Jr. 2001. A role for rubredoxin in oxidative stress protection in Desulfovibrio vulgaris: catalytic electron transfer to rubrerythrin and two-iron superoxide reductase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 394:76-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cypionka, H. 2000. Oxygen respiration by Desulfovibrio species. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:827-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Da Costa, P. N., M. Teixeira, and L. M. Saraiva. 2003. Regulation of the flavorubredoxin nitric oxide reductase gene in Escherichia coli: nitrate repression, nitrite induction, and possible post-transcription control. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 218:385-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dos Santos, W. G., I. Pacheco, M.-Y. Liu, M. Texeira, A. V. Xavier, and J. LeGall. 2000. Purification and characterization of an iron superoxide dismutase and a catalase from the sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio gigas. J. Bacteriol. 182:796-804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emerson, J. P., E. D. Coulter, R. S. Phillips, and D. M. Kurtz, Jr. 2003. Kinetics of the superoxide reductase catalytic cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 278:39662-39668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fareleira, P., J. LeGall, A. V. Xavier, and H. Santos. 1997. Pathways for utilization of carbon reserves in Desulfovibrio gigas under fermentative and respiratory conditions. J. Bacteriol. 179:3972-3980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fournier, M., Y. Zhang, J. D. Wildschut, A. Dolla, J. K. Voordouw, D. C. Schriemer, and G. Voordouw. 2003. Function of oxygen resistance proteins in the anaerobic, sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. J. Bacteriol. 185:71-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frazao, C., G. Silva, C. M. Gomes, P. Matias, R. Coelho, L. Sieker, S. Macedo, M. Y. Liu, S. Oliveira, M. Teixeira, A. V. Xavier, C. Rodrigues-Pousada, M. A. Carrondo, and J. Le Gall. 2000. Structure of a dioxygen reduction enzyme from Desulfovibrio gigas. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7:1041-1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu, R., and G. Voordouw. 1997. Targeted gene replacement mutagenesis of dcrA, encoding an oxygen sensor of the sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. Microbiology 143:1815-1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gardner, A. M., R. A. Helmick, and P. R. Gardner. 2002. Flavorubredoxin, an inducible catalyst for nitric oxide reduction and detoxification in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 277:8172-8177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomes, C. M., G. Silva, S. Oliveira, J. LeGall, M. Liu, A. V. Xavier, C. Rodrigues-Pousada, and M. Teixeira. 1997. Studies on the redox centers of the terminal oxidase from Desulfovibrio gigas and evidence for its interaction with rubredoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 272:22502-22508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haveman, S. A., E. A. Greene, C. P. Stilwell, J. K. Voordouw, and G. Voordouw. 2004. Physiological and gene expression analysis of inhibition of Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough by nitrite. J. Bacteriol. 186:7944-7950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haveman, S. A., E. A. Greene, and G. Voordouw. 2005. Gene expression analysis of inhibition of Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough by nitrate-reducing, sulfide-oxidizing bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 7:1461-1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heidelberg, J. F., R. Seshadri, S. A. Haveman, C. J. Hemme, I. A. Paulsen, J. F. Kolonay, J. A. Eisen, N. Ward, B. Methe, L. M. Brinkac, S. C. Daugherty, R. T. Deboy, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, R. Madupu, W. C. Nelson, S. A. Sullivan, D. Fouts, D. H. Haft, J. Selengut, J. D. Peterson, T. M. Davidsen, N. Zafar, L. Zhou, R. Radune, G. Dimitrov, M. Hance, K. Tran, H. Khouri, J. Gill, T. R. Utterback, T. V. Feldblyum, J. D. Wall, G. Voordouw, and C. M. Fraser. 2004. The genome sequence of the anaerobic, sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough: consequences for its energy metabolism, biocorrosion and reductive metal bioremediation. Nat. Biotechnol. 22:554-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenney, F. E., M. F. J. M. Verhagen, X. Cui, and M. W. W. Adams. 1999. Anaerobic microbes: oxygen detoxification without superoxide dismutase. Science 286:306-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kjeldsen, K. U., C. Joulian, and K. Ingvorsen. 2005. Effects of oxygen exposure on respiratory activities of Desulfovibrio desulfuricans strain DvO1 isolated from activated sludge. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 53:275-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lumppio, H. L., N. V. Shevni, R. P. Garg, A. O. Summers, G. Voordouw, and D. M. Kurtz, Jr. 2001. Rubrerythrin and rubredoxin oxidoreductase in Desulfovibrio vulgaris: a novel oxidative stress protection system. J. Bacteriol. 183:101-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Postgate, J. R. 1984. The sulphate-reducing bacteria, 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 23.Rodrigues, R., J. B. Vicente, R. Felix, S. Oliveira, M. Texeira, and C. Rodrigues-Pousada. 2006. Desulfovibrio gigas flavodiiron protein affords protection against nitrosative stress in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 188:2745-2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schweizer, H. P. 1992. Allelic exchange in Pseudomonas aeruginosa using novel ColE1-type vectors and a family of cassettes containing a portable oriT and the counter-selectable Bacillus subtilis sacB marker. Mol. Microbiol. 6:1195-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sigalevich, P., and Y. Cohen. 2000. Oxygen-dependent growth of the sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio oxyclinae in coculture with Marinobacter sp. strain MB in an aerated sulfate-depleted chemostat. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:5005-5012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silaghi-Dumitrescu. R., E. D. Coulter, A. Das, L. G. Ljungdahl, G. N. L. Jameson, B. H. Huynh, and D. M. Kurtz, Jr. 2003. A flavo-diiron protein and high molecular weight rubredoxin from Moorella thermoacetica with nitric oxide reductase activity. Biochemistry 42:2806-2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silaghi-Dumitrescu. R., K. Y. Ng, R. Viswanathan, and D. M Kurtz, Jr. 2005. A flavo-diiron protein from Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough with oxidase and nitric oxide reductase activities. Evidence for an in vivo nitric oxide scavenging function. Biochemistry 44:3572-3579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simon, R., U. Priefer, and A. Pühler. 1983. A broad-host-range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology 1:784-791. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stams, F. J. M., M. Veenhuis, G. H. Weenk, and T. A. Hansen. 1983. Occurrence of polyglucose as a storage polymer in Desulfovibrio species and Desulfobulbus propionicus. Arch. Microbiol. 136:54-59. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Niel, E. W. J., and J. C. Gottschal. 1998. Oxygen consumption by Desulfovibrio strains with and without polyglucose. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1034-1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Voordouw, J. K., and G. Voordouw. 1998. Deletion of the rbo gene increases the oxygen sensitivity of the sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2882-2887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Voordouw, G. 2002. Carbon monoxide cycling by Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. J. Bacteriol. 184:5903-5911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiong, J., D. M. Kurtz, Jr., J. Ai, and J. Sanders-Loehr. 2000. A hemerythrin-like domain in a bacterial chemotaxis protein. Biochemistry 39:5117-5125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]