Abstract

The lytic lactococcal phage Q54 was previously isolated from a failed sour cream production. Its complete genomic sequence (26,537 bp) is reported here, and the analysis indicated that it represents a new Lactococcus lactis phage species. A striking feature of phage Q54 is the low level of similarity of its proteome (47 open reading frames) with proteins in databases. A global gene expression study confirmed the presence of two early gene modules in Q54. The unusual configuration of these modules, combined with results of comparative analysis with other lactococcal phage genomes, suggests that one of these modules was acquired through recombination events between c2- and 936-like phages. Proteolytic cleavage and cross-linking of the major capsid protein were demonstrated through structural protein analyses. A programmed translational frameshift between the major tail protein (MTP) and the receptor-binding protein (RBP) was also discovered. A “shifty stop” signal followed by putative secondary structures is likely involved in frameshifting. To our knowledge, this is only the second report of translational frameshifting (+1) in double-stranded DNA bacteriophages and the first case of translational coupling between an MTP and an RBP. Thus, phage Q54 represents a fascinating member of a new species with unusual characteristics that brings new insights into lactococcal phage evolution.

Lactococcus lactis is a low-G+C gram-positive bacterium extensively used by the dairy industry for its ability to convert sugars into lactic acid, leading to various fermented milk products. However, L. lactis strains are susceptible to attacks by lytic bacteriophages with concomitant low-quality products and economic losses (56). Different strategies have been developed over the past 70 years with the aim of better controlling the indigenous phage population within the dairy environment (54, 71). Nevertheless, the phage population is constantly evolving and new phage isolates are still frequently isolated. Some of these phages are emerging due to current manufacturing practices (49).

Classification of the phages is still controversial, and different propositions have been made in recent years (10, 65, 74). Previous classification studies relied on the comparison of virus morphology and DNA-DNA hybridizations using whole genomes. According to these criteria, 12 lactococcal phage species representing distinct phage groups were proposed (37, 38). This classification of lactococcal phages was recently revisited, and 10 genetically diverse groups of phages, sharing very limited nucleotide similarities, were proposed (26). Among these, two new species were identified, one of which was the type phage Q54.

Phage genomics has considerably expanded in the last 5 years, and as of June 2006, 362 complete genomes are available at GenBank. Of those, 14 are from lactococcal phages. Among the available genomes, only members of the three main groups of L. lactis phages are represented, namely, the 936, c2, and P335 species. Ten of the genomes are from phages of the P335 species (4, 9, 15, 40, 50, 68, 74, 75), whereas only four sequences are from 936- and c2-like phages, namely, bIL170 and sk1 (936 species) as well as c2 and bIL67 (c2 species) (12, 18, 48, 67). The lack of genome sequences from the less frequently isolated phage species is probably explained by the higher industrial incidences of failed fermentations due to the members of the three above predominant species (37, 39).

According to the proposed classification scheme, lactococcal phages are highly diverse between species but rather homogeneous within the same species. For example, virulent phages within the 936 or c2 species are highly similar at the DNA level and up to 90% of their genome length can be aligned with over 70% nucleotide identity (15, 18, 48). As a result, most of the open reading frames (ORFs) share more than 80% amino acid identity, some being almost identical. Point mutations and small insertion/deletions (indels) were shown to account for most of the differences in the genome sequences of lytic phages (18, 48). Due to the lack of temperate members, homologous recombination between members of the 936 and c2 species is not expected to occur frequently, although it may occur during coinfection (15). On the other hand, the P335 group of phages, comprising both temperate and lytic members, is less conserved and has a polythetic nature. Indeed, several P335-like phages share conserved modules, but there is no single ORF shared by all members of this group (4, 9, 15, 23, 24, 40). Comparative genomics of these P335-like phages thus revealed a highly mosaic structure, defining functional modules that are exchangeable through homologous recombination, in addition to point mutations and indels (15, 23, 57).

Structural proteins that make up the viral particle have been studied for only a few lactococcal phages including c2 (48) and p2/936 species (69) as well as the P335-like phages ul36 (40), r1t (75), BK5-T (50), and TP901-1 (76). Posttranslational modifications of structural proteins, especially the major capsid protein (MCP), have been well documented for a number of model phages such as the coliphage HK97 (29). The MCP from the lactococcal phage c2 was also shown to undergo proteolytic cleavage and cross-linking during capsid assembly (48). Although proteolysis of the capsid has been reported for a number of other members, cross-linking among lactococcal phages has been so far reported only for phages c2 and r1t (48, 75). In other phages, cross-linking of viral subunits does not appear to be frequent, except perhaps for mycobacteriophages, where this mechanism seems to be more common (28, 34).

Programmed translational frameshifting is well documented in double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) bacteriophages, including Escherichia coli phage λ (44). Generally, it involves tail proteins, more specifically the major tail protein (MTP) and an overlapping ORF preceding the tape measure protein (79). Most of the frameshift events recognized so far are of the −1 type, where a slippery sequence composed of repeated nucleotides enables the ribosome to slip one nucleotide backward before continuing translation on the corresponding overlapping frame. An unusual −2 frameshift was recently demonstrated in tail proteins from phage Mu (79). Only a few examples of +1 frameshifting have been documented in E. coli, with the well-described examples of release factor 2 (RF2) (17) and an expression system involving human transferrin (Tf) (25). In the case of Tf, a “shifty stop” with the sequence CCC.UGA was found to be responsible for ribosome frameshifting (25). Recently, the first case of programmed +1 translational frameshifting in dsDNA phages was reported for the Listeria monocytogenes temperate phage PSA, where elongated versions of the capsid protein and MTP were identified (80). In the MTP frameshift, a CCC.UGA “shifty stop” at the end of the tail gene was also found to be responsible for the event. Notably, a pseudoknot 3′ to the slippery signal was probably also involved in the mechanism (80). Secondary structures downstream from slippery signals have been shown to promote frameshifting (43).

Here, we report the microbiological and molecular characterization of a novel lactococcal phage species, for which the lytic phage Q54 is currently the only member. Complete genomic and transcriptional analyses are provided which reveal an unusual module configuration and shed light on its peculiar origin. A detailed analysis of the structural proteins uncovered interesting features, including cross-linking of the MCP and a programmed +1 translational frameshift between the MTP and the receptor-binding protein (RBP). To our knowledge, this is only the second case of programmed +1 translational frameshifting in dsDNA phages and the first case of a translational coupling between a major tail protein and an RBP, the latter being involved in host recognition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial and phage amplification.

Lactococcus lactis SMQ-562 and L. lactis LM0230 were grown at 30°C in M17 broth (72) supplemented with 0.5% glucose (GM17) (Difco) unless otherwise specified. Glycine (0.5%) was also added to the top agar to increase plaque size and facilitate phage enumeration (45). CaCl2 (final concentration of 10 mM) was added whenever phages were used. When high phage titers were required, lysates were concentrated with polyethylene glycol and purified by two CsCl gradient ultracentrifugations (14). The first centrifugation was performed at 35,000 rpm for 3 h in a discontinuous-step CsCl gradient using a Beckman SW41 Ti rotor. The phage band was picked up and further purified by ultracentrifugation at 60,000 rpm for 18 h in a continuous single-phase CsCl gradient using a Beckman NVT65 rotor (66).

Microbiological assays.

One-step growth curve assays were performed as reported elsewhere (55). The burst size was determined by dividing the average phage titer after the exponential phase by the average titer before infected cells began to release virions (55). The efficiency of plaque formation (EOP) was calculated by dividing the phage titer on the tested L. lactis strain by the titer on the sensitive control L. lactis strain.

Phage DNA analysis.

Phage Q54 genomic DNA was isolated using the Maxi Lambda DNA purification kit (QIAGEN). Genome sequencing was first performed using a shotgun cloning strategy (Integrated Genomics Inc., Chicago, Ill.). Completion of the genome was done by direct sequencing of the phage DNA with primers and using an ABI Prism 3700 apparatus from the genomic platform at the research center of the Centre Hospitalier de l'Université Laval. The cos site was determined by direct sequencing of the phage DNA and by sequencing of a PCR product encompassing the T4-ligated cohesive termini. Standard PCR and ligation procedures were used (66).

RNA isolation and Northern blot analysis.

Two hundred milliliters of GM17 was inoculated (1%) with an overnight culture of L. lactis SMQ-562, and cells were grown at 30°C until the optical density at 600 nm reached 0.1. CaCl2 was added to a final concentration of 5 mM, and incubation was continued for 5 min. Cells were then centrifuged at room temperature for 2 min at 10,000 rpm in a Beckman GSA rotor. The pellet was suspended in 20 ml of GM17 containing 5 mM CaCl2 to obtain a final optical density at 600 nm of 1.0. At time zero, a sample of 1.5 ml was removed and quickly centrifuged for 15 s, the supernatant was removed, and the cell pellet was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Cells were stored at −80°C until RNA extraction. Phage Q54 was added to the remaining culture at a multiplicity of infection of 10. Aliquots of 1.5 ml were withdrawn at various time intervals and processed as described above. Lysis of the remaining phage-infected culture after 45 min was indicative of the completion of the phage lytic cycle.

The next day, cells were thawed on ice and resuspended in a total volume of 100 μl of a sucrose solution (0.5 M) containing 120 mg/ml lysozyme. The mixture was incubated 10 min at 37°C prior to the addition of 1 ml of Trizol (Invitrogen), as recommended by the supplier. This step was necessary to achieve rapid and complete cell lysis. Following its isolation, the RNA was treated with 30 units RNase-free DNase I (Roche) for 30 min at 37°C in the presence of Protector RNase inhibitor (Roche) and quantified by UV spectrometry at 260 nm. Northern blotting was performed after separation of 5 μg of RNA through a 1% agarose-formaldehyde denaturing gel (66). Probes used to detect mRNAs consisted of 32P-labeled oligonucleotides (25- to 35-mer; sequences available upon request) complementary to the coding strand of the gene of interest. Labeling reaction mixtures consisted of 2 pmol of oligonucleotide, 1× reaction buffer, 30 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (GE Healthcare), and 20 units of T4 polynucleotide kinase (Roche) in a final volume of 20 μl. Incubation was performed at 37°C for 30 min, after which 50 μl of distilled water was added. Probes were quickly purified using Micro Bio-Spin 30 columns (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The efficiency of labeling of the purified probes was determined by liquid scintillation counting. A minimum specific activity of 2 × 106 cpm/pmol oligonucleotide was our cutoff in order to use the labeled probe in the hybridization experiments. Membranes were prehybridized at 42°C for at least 1 h in 5 ml of UltraHyb-Oligo hybridization buffer (Ambion) in a 50-ml disposable screw-cap tube. Hybridization was performed overnight at 42°C in the presence of 5 × 106 cpm of the freshly labeled probe. Membranes were washed twice at 42°C for 30 min in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) plus 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and then exposed to Kodak XOMAT-AR films at −80°C with intensifying screens.

SDS-PAGE analysis of structural proteins.

Purified phages (∼1 × 1011 PFU/ml) were analyzed for structural proteins by standard Tris-glycine 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) procedures (42). Samples were mixed with 2× sample loading buffer and boiled for 10 min before loading. Proteins were detected after Coomassie blue staining. For phage Q54, further concentration of the phage suspension was required before electrophoresis. This was achieved by centrifuging 1.5 ml of CsCl-purified phage suspension through Nanosep 3k columns (Pall), which led to a further 1-log concentration factor. Protein bands were cut out of the gel, digested with trypsin, and identified by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) (Génome Québec Innovation Centre, McGill University). For comparison purposes, the structural proteins of the reference phage c2 (48) were also analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Bioinformatics analysis.

DNA sequence analysis, contig assembly, and editing were done using the Staden package 1.5.3 (available at http://staden.sourceforge.net/). Some editing was also done using BioEdit 7.0.5.2 (33). Protein sequence comparisons were performed using BLASTP 2.2.13 (2), and conserved domains were identified using RPS-BLAST 2.2.11 and the Conserved Domains Database (CDD) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (51, 52). PSI-BLAST was also used to search for more distant homologous proteins when standard BLAST hits gave only proteins with putative or unknown functions. InterProScan at EMBL-EBI (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/InterProScan/) was used to identify conserved domains in some proteins that did not show any significant similarity by BLAST searches. Putative RNA secondary structures were determined using Vienna RNA secondary structure prediction v1.5 at http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/cgi-bin/RNAfold.cgi and MFOLD at http://bioweb.pasteur.fr/seqanal/interfaces/mfold-simple.html (81).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence data reported in this paper have been deposited in EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ databases under accession number DQ490056.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Q54 and its lytic cycle.

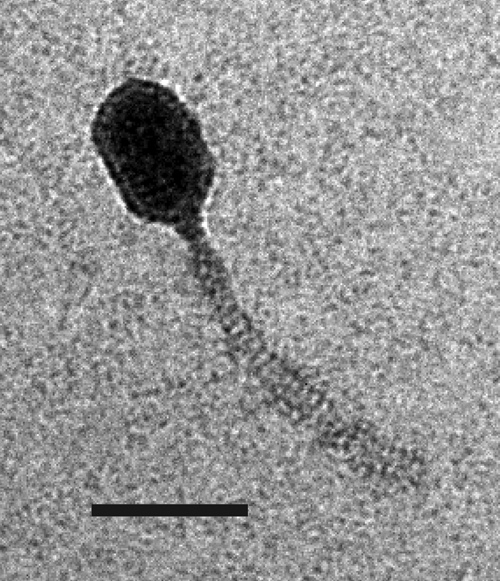

The lytic phage Q54 was previously isolated from a failed sour cream production, which used Lactococcus lactis SMQ-562 in its starter culture. Transmission electron microscopy analysis revealed a morphology similar to that of phage c2, with a prolate capsid (56 × 43 nm) and a noncontractile tail (109 nm) (Fig. 1) (26). Thus, phage Q54 belongs to the Siphoviridae family of the Caudovirales order. It was recently reported that DNA-DNA hybridization experiments failed to show any homology between Q54 and genomic probes from the nine other known lactococcal phage species, c2, 936, P335, 1358, P087, 1706, 949, P034, and KSY1 (26). Based on these observations, Q54 was classified as a new lactococcal phage species, and this prompted us to further characterize this phage.

FIG. 1.

Electron micrograph of phage Q54. Bar, 50 nm.

The phage Q54 host range was assessed using 58 L. lactis strains, and this phage was shown to infect only L. lactis SMQ-562. Of note, this L. lactis strain is also sensitive to the reference phages 1706 and 949, which are members of two other lactococcal phage species that bear their names. A single-step growth curve assay of phage Q54 was performed at 30°C with L. lactis SMQ-562. The phage has a latent period of 40 min and a burst size of 42 ± 8 PFU. The permissive temperature range for propagation of Q54 is 22 to 33°C. Interestingly, at 34°C and above (up to 38°C), we could not detect a single plaque on L. lactis SMQ-562.

The sensitivity of phage Q54 towards three phage resistance mechanisms, namely, AbiK (32), AbiQ (31), and AbiT (6), was determined. Numerous phage resistance mechanisms are currently used by the dairy industry to control the three main phage species (936, c2, and P335). Thus, we were interested to know if the new phage species Q54 could be controlled by these abortive infection mechanisms (Abis). High-copy-number plasmids expressing the three Abi systems were transferred into L. lactis strain SMQ-562, and the resulting transformants were challenged with Q54. AbiQ and AbiT were very effective against Q54, with mean EOP values of ≤10−8 and 3.3 × 10−7 ± 2.2 × 10−7, respectively. On the other hand, AbiK was ineffective against this phage (EOP of 0.81 ± 0.54). AbiK is generally very efficient against the three main phage species (32), which confirms the distinct nature of Q54.

Complete nucleotide sequence of Q54 genome.

A shotgun cloning strategy was used to sequence ∼90% of the Q54 genome. Primer walking and direct sequencing of the phage DNA were performed to complete the remaining 10% covering both genome extremities. Runoff sequencing reactions enabled us to locate the exact ends of the linear phage genome. No terminal redundancy was observed, suggesting a cos-type phage. Confirmation was made by ligating the cohesive termini with T4 DNA ligase followed by sequencing of a PCR fragment spanning the resulting junction (Fig. 2). The cohesive termini are composed of single-stranded 10-bp 3′ overhangs (Fig. 3A). The complete genome sequence of 26,537 bp has a molar G+C content of 37.1 mol%, which is similar to those of L. lactis and other lactococcal phages (5, 12, 40, 48).

FIG. 2.

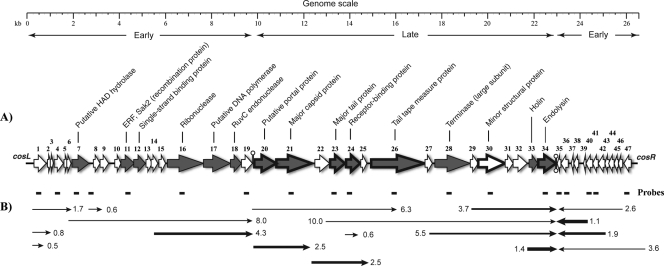

Q54 complete genome (26,537 bp). (A) Genomic organization. A scale (in kilobases) is shown above the genetic map. Each arrow represents a putative ORF, and the numbering refers to Table 1. Gray arrows represent ORFs for which a putative function could be inferred from bioinformatics analyses (indicated above the ORFs). White arrows represent ORFs for which no putative function could be attributed. Hairpins represent putative Rho-independent transcriptional terminators. Arrows with heavy outlines represent gene products detected by LC-MS/MS analysis (Fig. 4). (B) Phage Q54 mRNA transcripts detected in the course of an infection of L. lactis SMQ-562. Short thick lines above the transcripts indicate probes. The size (in kilobases) is indicated on the right or left of each transcript (arrows), and the line thickness is representative of their relative abundance, with the thicker line corresponding to the highest concentration. Arrowheads show the direction of transcription, and the temporal expression (early or late) is indicated below the genome scale.

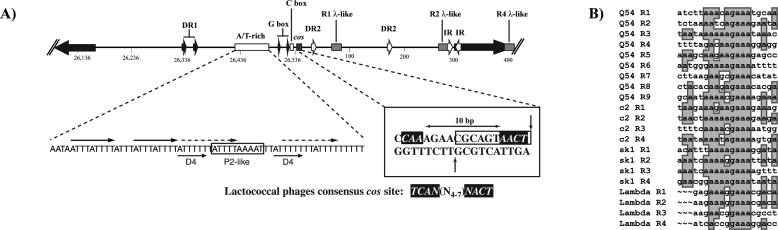

FIG. 3.

Analysis of Q54 cos region. (A) Analysis of the cos site and flanking regions. Typical features found in the cos vicinity of other phages, such as direct repeats (DR1 and DR2), inverted repeats (IR), A/T-rich region, G- and C-rich segments (G and C box, respectively), and λ-R-like sequences (λ-like), are indicated. Details of the cohesive termini are also shown. The sites of cleavage resulting in 3′-overhang termini are indicated by vertical arrows. Italic characters with reverse highlighting represent nucleotides that are identical to a consensus sequence found in all lactococcal phages for which the cos region has been sequenced (see text for details). (B) Multiple alignment of λ-R-like sequences from Q54, c2, and sk1 with those of λ-R sequences from phage λ. Conserved nucleotides are shaded.

Analysis of Q54 cos region.

Analysis of the DNA sequence surrounding the cos site revealed features common to other lactococcal phages of the 936 and c2 species, including several direct and inverted repeats and G- and C-rich clusters (G and C boxes) as well as an A/T-rich region (16 A + 47 T) (Fig. 3A) (13, 47, 61, 62). However, the cos site of phage Q54 lacks a conserved T in one of the inverted repeats (4 bp, TCAN) typically found within a 15-bp segment spanning the cos site of lactococcal phages (61, 62). The phage Q54 cos region also contains nine λ-like R consensus sequences (19). In λ, the R sites are 16 nucleotides long whereas in Q54 the consensus was extended to 19 nucleotides from comparison with those previously reported for phages c2 and sk1 (Fig. 3B) (62). The λ-R sites are involved in terminase recognition and binding as well as termination of packaging. However, in contrast to phages λ and c2, the Q54 λ-R sequences are unevenly distributed across a 900-bp region. In the former, the λ-R sites are regularly spaced (∼250 bp between R sites). Alignment of the R sites from λ with the λ-like R sites from phages Q54, c2, and sk1 (Fig. 3B) highlighted common bases likely involved in the packaging process.

Comparison of Q54 ORFs and functional assignment.

Further bioinformatics analyses enabled the identification of 47 putative ORFs of 35 amino acids or more (Fig. 2A; Table 1) in the genome of phage Q54. The standard ATG start codon and also alternative start codons were used to locate ORFs. These were determined on the basis of the presence of a suitable ribosome binding site complementary to the 3′ end of the 16S rRNA of L. lactis located upstream of the selected start codon as well as the absence of extensive overlapping between ORFs. The longest gap observed was 286 bp between ORFs 9 and 10, and the longest overlap tolerated was 13 bp between ORFs 10 and 11 (Table 1). There are two main groups of ORFs in Q54: one group spanning almost the entire genome and which is on the upper strand and a second group of 10 ORFs (orf35 to orf47) encoded by the lower strand (approximately 3.5 kb) at the right end of the genome (Fig. 2A).

TABLE 1.

Putative ORFs deduced from Q54 genome sequence and their predicted functions

| ORF | Position

|

Size (aa) | Molecular mass (kDa) | pI | Putative RBSa and start codon (AGAAAGGAGGT------ATG)b | Predicted functionc | Best match (extent no. identical/no. total; % amino acid identity) | E value | Sizef (aa) | Accession no. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | Stop | ||||||||||

| 1 | 290 | 820 | 176 | 20.6 | 9.6 | AGAAAGAAtaatatagttttTTG | — | ORF47 L. lactis phage sk1 (48/117; 41%) | 1E-12 | 230 | NP_044993 |

| 2 | 858 | 1025 | 55 | 6.6 | 8.9 | AGAAAGAGGtgctaacATG | — | ||||

| 3 | 1022 | 1150 | 42 | 4.9 | 9.4 | AGAGAGGGTGgaaaaATG | — | ||||

| 4 | 1165 | 1563 | 132 | 15.2 | 8.7 | ATTAAGGAGaaataaaaaaATG | — | ORF131 L. lactis phage P335 (71/131; 54%) | 2E-33 | 131 | AAR14302 |

| 5 | 1580 | 1747 | 55 | 6.5 | 5.8 | AGAAAGGAaaaataaaaATG | — | ||||

| 6 | 1734 | 1925 | 63 | 7.5 | 9.9 | AATTTGGAGGgtggaatcATG | — | ||||

| 7 | 1927 | 2682 | 251 | 28.4 | 5.0 | AGAAAAGcacgagggcgaataatTTG | Putative HADd hydrolase | Protein GK1056 Geobacillus kaustophilus HTA426 (60/246; 24%) | 2E-8 | 258 | BAD146909 |

| 8 | 2842 | 3150 | 102 | 12.1 | 8.8 | GAAAGGAaaaaatagATG | — | ||||

| 9 | 3157 | 3507 | 116 | 13.4 | 4.6 | AGAAAGGAtaaaatgatATG | — | ||||

| 10 | 3792 | 4052 | 86 | 10.3 | 6.6 | AGAAAGGttaaagaatcATG | — | ||||

| 11 | 4036 | 4629 | 197 | 22.6 | 5.0 | AAAAAGAGGGTataaataTTG | ERF; recombination protein | Sak2 L. lactis phage P335 (67/152; 44%) | 7E-22 | 202 | AAR14303 |

| 12 | 4616 | 5113 | 165 | 18.8 | 9.0 | AGAGGAGATtctaacagATG | SSB protein | Single-stranded binding protein L. lactis IL1403 (105/168; 62%) | 4E-47 | 166 | AAK06288 |

| 13 | 5128 | 5391 | 87 | 9.9 | 4.8 | AGAAAGGGGtaaaaaATG | — | ||||

| 14 | 5388 | 5702 | 104 | 11.8 | 4.8 | AGAAAGaAtaatgtattTTG | — | ||||

| 15 | 5696 | 5992 | 98 | 11.4 | 5.4 | AAGAAGTAGGcggggtttttgaATG | — | ||||

| 16 | 6051 | 7637 | 528 | 59.6 | 7.2 | AGAAAGGGTTTaacctATG | RNase | Exoribonuclease R L. lactis SK11 (227/517; 43%) | 1E-108 | 810 | ZP_00382703 |

| 17 | 7637 | 8800 | 387 | 43.8 | 6.3 | AGAAAAAAGGgaaacgaaaataATG | Putative DNA polymerase | ORF80 L. monocytogenes phage P100 (91/321; 28%) | 4E-23 | 423 | YP_406456 |

| 18 | 8797 | 9279 | 160 | 18.0 | 9.3 | AATTAGGAGGaattacTTG | RuvC endonuclease | SpyM3_1128 S. pyogenes prophage 315.3 (47/158; 29%) | 7E-6 | 170 | NP_795506 |

| 19 | 9284 | 9754 | 156 | 18.3 | 5.1 | GAAAGGACTTtaaaacaATG | — | ||||

| 20 | 9837 | 10799 | 320 | 35.7 | 5.0 | AGAAGAAAGGggagctaATG | Putative portal | ORF14 L. lactis phage c2 (46/210; 21%) | 2E-5 | 279 | NP_043552 |

| 21 | 10783 | 12336 | 517 | 56.5 | 5.5 | GAAAGTAAAggcggagATG | Major capsid | ORF15 L. lactis phage c2 (117/428; (27%)) | 3E-21 | 480 | NP_043553 |

| 22 | 12449 | 13102 | 217 | 23.3 | 4.9 | AGAAAGAGGaataaATG | — | ||||

| 23 | 13119 | 13757 | 212 | 22.8 | 4.7 | GAAAGGAAATaaaaaaATG | Major tail protein | ORF17 L. lactis phage c2 (61/205; 29%) | 2E-12 | 205 | NP_043555 |

| 24 | 13825 | 14436 | 203 | 23.0 | 4.8 | AGAAAGattcacgactATT | Receptor binding | ORF45 L. lactis phage 4268 (120/201; 59%) | 5E-65 | 1,579 | NP_839936 |

| 25 | 14448 | 14711 | 87 | 10.2 | 4.9 | AGAAAGGcaaaaaATG | — | ||||

| 26 | 14907 | 17216 | 769 | 81.3 | 8.8 | AAGGGAGGcgttaagaaATG | Tail tape measure | ORF110 L. lactis phage c2 (193/567; 34%) | 9E-85 | 706 | NP_043558 |

| 27 | 17234 | 17545 | 103 | 12.0 | 7.7 | AGAAAGGGGcaagcATG | — | ORF111 L. lactis phage c2 (34/101; 33%) | 8E-9 | 95 | NP_043559 |

| 28 | 17665 | 19209 | 514 | 58.5 | 7.1 | AAAAAGTTCTTcgtaaaATG | Terminase | ORF32 L. lactis phage bIL67 (172/505; 34%) | 8E-74 | 518 | AAA74327 |

| 29 | 19203 | 19541 | 112 | 12.8 | 5.1 | GAAAGGAatacaaaaacATG | — | ORF113 L. lactis phage c2 (31/101; 30%) | 0.032 | 99 | NP_043561 |

| 30 | 19538 | 20713 | 391 | 42.5 | 6.6 | AGCGGAGGgacttctATG | Minor structural | ||||

| 31 | 20715 | 21062 | 115 | 13.0 | 4.5 | ATAGGAGaataaaATG | — | ||||

| 32 | 21062 | 21679 | 205 | 23.1 | 6.7 | ATATTTGAGGgggaaattttataATG | — | ||||

| 33 | 21754 | 22131 | 125 | 13.8 | 6.5 | AGGAGGgacaaaaaaATG | Holine | ||||

| 34 | 22146 | 22922 | 256 | 29.0 | 7.7 | AAAAAGGAGGTattcaATG | Endolysin | ORF122 L. lactis phage bIL170 (154/250; 61%) | 1E-83 | 233 | AAR26447 |

| 35 | 23116 | 22955 | 53 | 6.5 | 4.7 | AGAAAGGAaaaaaaATG | — | ORFe25 L. lactis phage bIL170 (14/50; 28%) | 1.8 | 53 | AAR26450 |

| 36 | 23444 | 23130 | 104 | 11.7 | 10.4 | AAAGAGTATGaccctagaccgtccgcaATG | — | ||||

| 37 | 23683 | 23570 | 37 | 4.3 | 9.2 | AAATGATGacaaaaacagaaATT | — | ||||

| 38 | 23909 | 23676 | 77 | 9.5 | 9.7 | AAACGAGGgttaaaaaaATG | — | ||||

| 39 | 24221 | 24108 | 37 | 4.3 | 7.9 | AGAATGGGAGggtaaaaaATG | — | ||||

| 40 | 24505 | 24218 | 95 | 11.3 | 8.7 | ATTAATGGGGaaaatacaaaATG | — | ORFe24 L. lactis phage bIL170 (45/102; 44%) | 1E-14 | 102 | NP_047149 |

| 41 | 24758 | 24492 | 88 | 10.7 | 9.4 | AAGTATGataaaatagaattATG | — | ORF41 L. lactis phage sk1 (26/78; 33%) | 5E-6 | 88 | NP_044987 |

| 42 | 25042 | 24755 | 95 | 11.5 | 9.0 | AGAAAGGAAGatttacgggtggactaaATG | — | ||||

| 43 | 25212 | 25039 | 57 | 6.6 | 9.6 | AGAAATGATTTgttctATG | — | ||||

| 44 | 25444 | 25202 | 80 | 9.8 | 9.3 | AAGAGGTaaaaaaATG | — | ||||

| 45 | 25614 | 25441 | 57 | 6.8 | 4.3 | AAGGAGtaaaaaaaaATG | — | ||||

| 46 | 25797 | 25621 | 58 | 6.9 | 9.6 | AAGGAGGGTatgaaATG | — | ||||

| 47 | 26179 | 25856 | 107 | 12.0 | 4.9 | ACTAAGGAGGTacatactATG | — | ||||

RBS, ribosomal binding site.

Underlining indicates nucleotides identical to the RBS consensus; lowercase indicates spacer nucleotides between the RBS and start codon; boldface indicates the start codon.

—, no predicted function.

HAD, haloacid dehalogenase-like hydrolase.

Identified by secondary structure analyses using InterProScan at EMBL-EBI (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro).

Size of the aligned protein.

The 47 deduced proteins were compared with protein databases using BLASTP in order to assign a putative function. Since there was only limited similarity between phage Q54 proteins and other proteins in the databases, the assignment of putative functions was further reinforced by position-based comparison with the genomes of other known phages, by the presence of conserved domains and/or secondary structures, and by experimental identification of structural proteins. Functional assignments and the best matches in databases are presented in Table 1, and further details are given below, but only for some of the ORFs.

(i) ORF11.

The best BLAST result for ORF11 is a protein with no predicted function from L. lactis SK11 (39% identity; 77/197) (accession no. ZP_00382242). Similarities were also found with proteins of the essential recombination factor (ERF) family, including Sak2 from phage P335 (44% identity; 67/152) (8). A conserved ERF domain (pfam04404) was also identified in ORF11. This domain is present in DNA single-stranded annealing proteins of the ERF superfamily of proteins, which function in RecA-dependent and RecA-independent DNA recombination pathways, such as RecT, Red-β, and Rad52. In phages with cohesive ends (such as Q54), the role of such a recombination protein was proposed to be similar to that of Red from phage λ, which increases the amount of packageable DNA (67).

(ii) ORF12.

ORF12 shows similarity with several bacterial single-stranded binding (SSB) proteins including those of L. lactis strains IL1403 (5) and SK11 (Table 1). Similarity was also observed with phage-encoded SSB proteins such as ORF9 from Streptococcus thermophilus phage 7201 (59% identity; 97/153) (70) and ORF1 from Streptococcus pneumoniae phage VO1 (58) (55% identity; 98/180). SSB proteins are involved in protection of single-stranded DNA segments generated during DNA replication (60, 78).

(iii) ORF16.

CDD searches revealed the presence of conserved domains within ORF16, namely, S1 (ribosomal protein S1-like RNA-binding domain: smart00316 and pfam00575), RNB (RNB-like protein: pfam00773), and VacB (exoribonuclease R: COG0557). These domains are found in RNA-binding proteins involved in RNA metabolism (e.g., transcription). Comparison with protein databases showed similarity with several chromosome-encoded RNases and exoribonucleases from diverse bacterial origins (Table 1).

(iv) ORF17.

The deduced protein ORF17 is similar to gp80 from Listeria phage P100 (Table 1) (11) and ORF98 from Staphylococcus aureus phage K (29% identity; 75/251) (59), which have unknown functions. After PSI-BLAST analysis (four iterations), we also found homologues for which a DNA polymerase function was predicted. The most significant hits included a DNA-directed DNA polymerase from the uncultured archaeon GZfos19C8 (15% identity; 49/315, E = 1E-49) and a DNA polymerase delta small subunit from Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus strain Delta H (14% identity; 47/314, E = 3E-47) (accession no. AAU82757 and AAB85882, respectively). An InterProScan analysis also revealed the presence of a metallophosphoesterase domain (IPR004843) found in a large number of proteins involved in phosphorylation, including DNA polymerases, exonucleases, and other phosphatases.

(v) ORF18.

ORF18 is similar to a putative protein from Streptococcus pyogenes prophage 315.3 (29% identity; 47/158) (3) and also to a conserved phage-associated protein from Streptococcus suis 89/1591 (24% identity; 39/157) (accession no. ZP_00875013). There is also similarity with a crossover junction endodeoxyribonuclease, RuvC from Chlorobium limicola DSM 245 (25% identity; 34/131, E = 0.016) (accession no. ZP_00511492). After two iterations of PSI-BLAST analysis, further hits were obtained with RuvC-like Holliday junction resolvases, including ORFm3 from lactococcal phages bIL170 (936 species, 25% identity; 40/157) (18) and ORF53 from phage sk1 (936 species, 25% identity; 40/158) (12). No hits were found with gene products from phages of the c2 species. However, BLAST analyses using ORF55 from phage sk1 revealed significant similarity with ORFl2 from phages c2 (44% identity; 71/161) and ORF23 from phage bIL67 (42% identity; 69/161) (67), which was recently demonstrated to be a RuvC-like resolvase (21).

Structural genes and morphogenesis.

Phage Q54 morphology is similar to that of the prolate-headed phages of the c2 species, and compared using BLAST analyses, most of the structural proteins were related to phage c2 or bIL67, or other members of the c2 species for which partial sequences are available.

(i) ORF20.

The only significant hits are ORFl4 from phage c2 (21% identity; 46/210), ORF25 from phage bIL67 (20% identity; 37/177), and a putative portal protein from a Streptococcus agalactiae prophage (17% identity; 28/159, E = 0.006) (accession no. AAN00717). The similarity with the latter protein and its location upstream from the capsid protein suggest that ORF20 from Q54 might be the putative portal protein. Also, a protein corresponding to this ORF was identified in the virion structure by SDS-PAGE mass spectrometry analysis (Fig. 4). It was previously suggested that ORFl4 of phage c2 might be a portal protein (22).

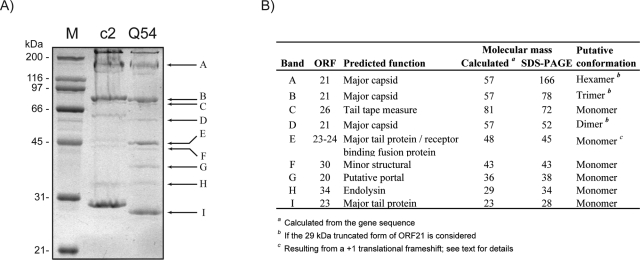

FIG. 4.

LC-MS/MS analysis of structural proteins of phage Q54. (A) Coomassie blue staining of a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel showing structural proteins from phages Q54 and c2. Arrows and letters on the right indicate bands cut out from the gel and identified by LC-MS/MS. The sizes (in kilodaltons) of the different proteins from the broad-range molecular mass standard (M) are indicated on the left. (B) Identification of Q54 viral proteins from corresponding bands shown in panel A.

(ii) ORF21.

The ORF21 protein was also detected in the structure of phage Q54 (Fig. 4). The deduced protein has similarity with the major capsid proteins (pfam05065) of phages of the lactococcal c2 species, including ORFl5 from phage c2 (27% identity; 117/428) (48) and ORF26 from phage bIL67 (25% identity; 134/518) (67). However, the percentage of identity was very low, as opposed to the 93 to 97% identity observed between the MCPs of c2-like phages such as c2, bIL67, Q38, Q44, and eb1.

(iii) ORF23.

ORF23 is most likely the MTP, because it is similar to homologues in phages c2 (ORFl7) and bIL67 (ORF28) (29% identity; 61/205 and 62/211, respectively) (48, 67). Again, a very low percentage of amino acid identity was observed, contrasting with the 88% identity (182/205) found between ORFl7 and ORF28 from phages c2 and bIL67, respectively. We also detected the corresponding protein in the structure of the virion (Fig. 4).

(iv) ORF24.

This protein is the third most conserved in Q54, showing similarity with several tail host specificity proteins and accessory tail fibers from diverse phages infecting both L. lactis and S. thermophilus. We noted 59% identity (120/201) with ORF45 from the lytic lactococcal phage 4268 of the P335 species (74). Similarity was also observed, although with slightly lower E values, with ORFl15 from L. lactis phage c2 (29% identity; 62/211) (48). InterProScan analyses also revealed the presence of a galactose-binding-like domain (IPR008979) within ORF24 of phage Q54. This domain is involved in binding to cell surface-attached galactose-containing carbohydrates of prokaryotes and eukaryotes (36). Moreover, ORF24 was found to be similar to the variable region 1 (VR1) of S. thermophilus phages Sfi11, Sfi19, Sfi21, MD2, and DT2, which were previously shown to be involved in host recognition (30). These findings further support the predicted function of ORF24 as the receptor-binding protein (73).

(v) ORF26.

ORF26 shares similarity with several c2-like phage tail proteins, and the best match was with the tape measure protein (ORFl10) of phage c2 (34% identity; 193/567). Other matches included the industrial lactococcal phage isolates 5469 (35% identity; 180/507) and 5440 (28% identity; 148/528) (64). ORF26 was also found in the structure of Q54 as revealed by SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry analyses (Fig. 4).

(vi) ORF28.

The ORF28 gene product has similarities with ORF32 of phage bIL67 (34% identity; 172/505) and ORFl12 of phage c2 (33% identity; 171/505), both predicted to be terminases (48, 67). A conserved Terminase_1 domain (pfam03354; COG4626) was also identified in ORF28 while CDD searches were being performed. The size of the gene product also suggests that it is the large terminase subunit, although no putative small terminase subunit could be identified by bioinformatic analysis. The presence of only one identifiable subunit of the terminase is not unusual, as it was observed for various lactococcal phages such as c2 (48), 4268 (74), and φLC3 (4) as well as for the Lactobacillus phage φadh (1).

Lysis module of phage Q54. (i) ORF33.

No significant BLAST hit was obtained with the deduced protein ORF33. However, the size and the location of this ORF within the genome suggest that it may encode the phage holin. Using InterProScan, we found three transmembrane-spanning segments (amino acids [aa] 10 to 30, 45 to 65, and 77 to 99) and 14 charged amino acids (including six lysine residues) within the 26 C-terminal residues of ORF33. These two elements are characteristics of holins, and the presence of three transmembrane segments would place this protein into class I of the holins (41, 77). Similar to the holins of the c2-like phages, no dual-start motif could be identified in the N terminus of ORF33, as opposed to the holin from phages of the 936 species (41).

(ii) ORF34.

This protein is predicted to be the endolysin, and it is one of two gene products of phage Q54 showing an amino acid identity greater than 60%. CDD searches revealed the presence of an N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase conserved domain (smart00644, pfam01510). BLAST searches revealed several hits with the endolysins from various phages, especially those of the lactococcal phages of the 936 species, including bIL170 (ORFl22, 61% identity; 154/250) (18) and sk1 (ORF20, 59% identity; 125/211) (12). Notably, a pairwise alignment of the orf34 of Q54 with orfl22 of phage bIL170 showed 60% nucleotide identity over the entire gene, which makes this gene the most conserved at the nucleotide level.

(iii) ORF35, ORF40, and ORF41.

BLAST searches with ORF35 gave no significant result, at least based on a threshold E value of 1.0 or below. Nevertheless, a single hit was found with ORFe25 from phage bIL170 when a lower stringency was used for the search (28% identity; 14/50, E = 1.8) (18). ORF40 was found to be similar to ORFe24 from phage bIL170 (44% identity; 45/102) (18) and ORFe26 from phage sk1 (38% identity; 39/102) (12). Finally, ORF41 is similar to early gene products from 936-like phages, including ORF41 from phage sk1 (33% identity; 26/78) and ORFe7 from phages bIL66M1 (27) and bIL170 (both 36% identity; 27/74). Despite these similarities, no function could be assigned to ORF35, ORF40, and ORF41.

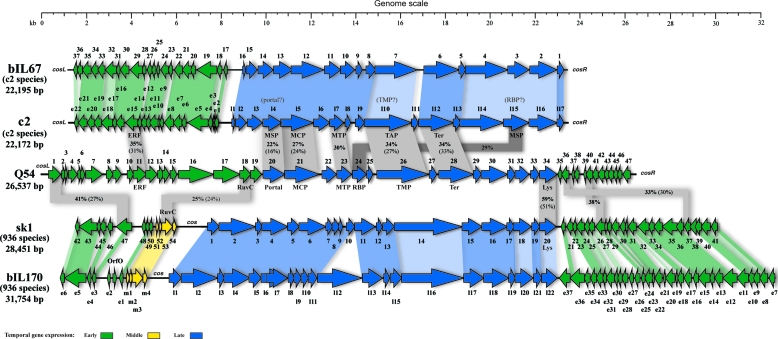

Comparative genomics of Q54 versus phages of the 936 and c2 species.

To better visualize the similarities between phage Q54 and the lactococcal phages from the c2 and 936 species described above, a whole-genome comparison was performed. Phages c2 and sk1 are closer to Q54 because several BLAST hits (although not always the best) were associated with these phages. As shown in Fig. 6, most of the ORFs present in the morphogenesis module of phage Q54 could be aligned with those of phage c2 (blue arrows). The order, number, and size of ORFs 20 to 29 were well conserved between the two phages. However, other ORFs are more closely related to phage sk1. For example, the protein similarity of Q54 endolysin (ORF34) with that of sk1 (ORF20) suggests that it might originate from a phage of the 936 species such as sk1.

FIG. 6.

Comparative genomics between Q54 and phages of the 936 and c2 species. Genome alignments present similarities between proteins of Q54 and phages c2 (accession no. NC_001706) and sk1 (accession no. NC_001835). ORFs from Q54 showing similarity to ORFs from these phages are linked by gray shading. The absence of shading means there was no significant similarity. The percent amino acid identity indicated inside the shading is representative of the aligned region only, whereas values in parentheses represent the percent amino acid identity over the entire length of the smaller of the two aligned proteins. Phages bIL67 (accession no. L33769) and bIL170 (accession no. NC_001909) were added into the alignment to show the extensive homology existing between phages of the same species. Color shading was used when two genomes from phages of the same species were aligned to discriminate between similarity of >80% amino acid identity (dark color) and similarity of ≤79% amino acid identity (light color).

Transcriptome analysis.

Temporal gene expression of phage Q54 was assessed by standard Northern blotting. Twenty radiolabeled probes were used to cover the genome and ORFs with predicted functions. Transcript sizes ranged from 0.5 to 10 kb and were detected over the entire genome (Fig. 2B). The level of mRNA transcripts was variable; some were detected as faint signals (thin arrows), and others were highly expressed (thick arrows) (Fig. 2B). According to our results, all ORFs are encoded by at least one mRNA, but most of them are encoded by more than one mRNA species, generally of different length and abundance. Transcripts that were detected at 5 min after the infection were classified as early mRNAs (orf1 to orf19 and orf35 to orf47) whereas transcripts that were detected after 10 to 15 min were considered late mRNAs (ORFs 20 to 34). The abundance and relative decay of the early mRNAs were highly variable. For example, the 8.0-kb transcript (covering ORFs 7 to 19) was detected at 5 min but almost completely disappeared after 15 min, whereas other transcripts like the 4.3-kb (covering ORFs 15 to 19) and 3.6-kb (covering ORFs 35 to 47) transcripts decreased gradually from 5 min to 30 min but were still easily detectable after 30 min (data not shown). Conversely, all late transcripts were detected after only 10 to 15 min and the signal continued to increase until the end of the assay. Based on the above transcriptional analysis and further bioinformatics analyses, three putative rho-independent terminators were identified (Fig. 2B). The first is located between ORFs 19 and 20 on the upper strand, and the two others are located between ORFs 34 and 35 on both strands and would probably function as a bidirectional terminator. A similar bidirectional terminator was also found between the early and late gene clusters in lactococcal phage sk1 (12).

SDS-PAGE analysis of Q54 structural proteins.

The protein composition of Q54 virions was characterized by SDS-PAGE coupled with LC-MS/MS. Since phage Q54 and the reference phage c2 share morphological and some protein sequence similarities, we included a purified sample from phage c2 for comparison purposes. Strikingly, the protein profiles from the two phages were highly similar (Fig. 4A). Mass spectrometry analysis of the nine bands detected after Coomassie blue staining of the gel enabled us to identify the corresponding coding gene in the genome of Q54 and make the correlation with the predicted functions (Fig. 4B). The molecular masses estimated by SDS-PAGE were in agreement with the masses calculated from the gene sequence for six proteins. Discrepancies were observed for proteins detected in bands A, B, D, and E (Fig. 4B).

Three bands of different sizes (A, B, and D) corresponded to the MCP. Additionally, the vast majority of peptides detected by LC-MS/MS from these three bands were mapped within the last 273 aa of the protein. These data strongly suggest that the N-terminal amino acids (250 aa) of the MCP are cleaved off during capsid assembly, as observed for phage c2 (48). Surprisingly, the molecular masses of bands A, B, and D were well over the molecular mass calculated from the gene sequence of the orf21 product, which is 56 kDa. However, inclusion of only the last 273 aa of the protein, as suggested by the LC-MS/MS analyses, would lead to a calculated mass of 29 kDa. Thus, dimers, trimers, and hexamers of this protein would correspond to masses of 59, 88, and 176 kDa, respectively, and would reasonably fit with the observed masses for bands A, B, and D on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4A). In phage c2, two major bands of 175 kDa and 90 kDa comigrated with bands A and B from Q54 and were previously proposed to be hexamers and trimers of the MCP, respectively (48). Additionally, there was a high-molecular-mass protein complex that barely penetrated the gel in the lanes for Q54 and c2. Although we did not try to identify this protein complex here, it was previously shown for phage c2 that this band contains a higher multimeric form of the MCP (48). According to the above data, the MCP subunits of Q54 are most likely processed and cross-linked during capsid assembly.

The fourth striking difference was the LC-MS/MS analysis of band E (Fig. 4), which revealed the presence of two proteins, namely, the major tail protein (ORF23/MTP) and receptor-binding protein (ORF24/RBP). An equivalent number of peptides covering the two proteins were detected, suggesting an equimolar ratio. This finding was rather surprising as band I (Fig. 4A) also corresponded to ORF23 and the molecular mass observed on SDS-PAGE was close to the mass calculated from the orf23 sequence. Since orf23 is translated from frame 3 and orf24 from frame 1, we investigated the possibility of a translational frameshift occurring between these two ORFs.

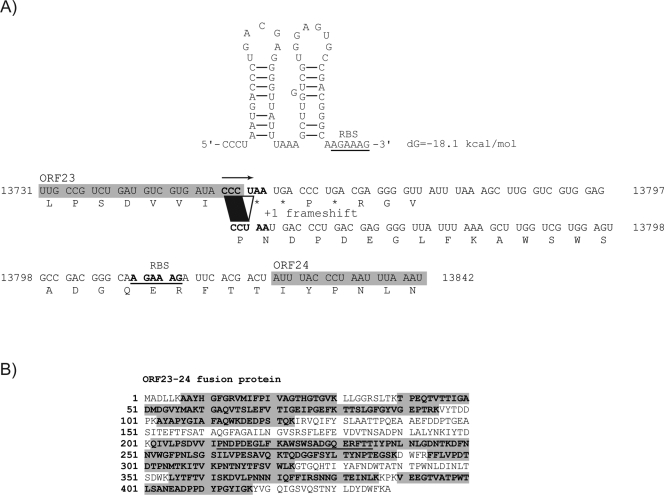

A detailed analysis of the intergenic region between orf23 and orf24 revealed the presence of a CCC.UAA codon at the end of orf23 which could act as a putative +1 “shifty stop” (Fig. 5A). Forward slippage (+1) of the translational machinery from this location would cause translation to occur on frame 1, the same as orf24. The frame 1 translational product covering the intergenic region starting from the CCU codon was found to be highly similar to a segment upstream from the region of ORF45 from lactococcal phage 4268 that matched Q54 RBP (Table 1). Importantly, a −2 frameshift would also lead to the same result, i.e., translation in frame 1, but with the addition of a supplementary amino acid (a tyrosine) between the isoleucine (I) and the last proline (P) residue from ORF23. Obviously, this additional amino acid would not be observed in a +1 frameshift. Thus, to confirm the occurrence of a frameshift event and to discriminate between the two possible frameshift mechanisms (+1 or −2), we searched for a matching peptide in band E. Analysis of the LC-MS/MS data enabled the identification of specific peptides mapping to this region and lacking a tyrosine residue, thus corresponding to the translational product resulting from a +1 frameshift (Fig. 5B). The result is an ORF23-ORF24 fusion protein with a calculated mass of 48 kDa, which fits well with the mass observed on SDS-PAGE for band E (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 5.

Programmed +1 translational frameshift. (A) Programmed +1 translational frameshift identified between orf23 and orf24 leading to translation of the 48-kDa protein (band E). A potential hairpin structure, shown above the sequence, was found next to the orf23 stop codon using the MFold program. (B) LC-MS/MS peptide mapping of ORF23-ORF24 fusion protein. The sequence represented here corresponds to that resulting from a +1 translational frameshift. The peptides detected by LC-MS/MS are shaded, and the translated intergenic region between ORF23 and ORF24 is underlined.

In L. lactis, the CCC codon, which encodes a proline residue, is ∼5 times less frequent than the CCU codon, also encoding a proline (http://www.kazusa.or.jp/codon/index.html). According to the proposed models, the translation machinery would make a pause at the CCC codon, which eventually would force a certain proportion of the ribosomes to slip forward (+1) to the next CCU codon. Translation would then continue downstream in the overlapping frame until the next stop codon. The presence of a two-stem-loop secondary structure next to the stop codon at the end of orf23 of phage Q54 (Fig. 5A) probably favors ribosome stalling as proposed by others (43, 80). Notably, the second stem-loop structure overlaps the ribosome-binding site upstream of orf24 and this could also regulate its translation. Accordingly, we did not detect ORF24 alone on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4A), suggesting that translation initiation upstream of ORF24 is probably infrequent or may not occur at all.

DISCUSSION

This paper describes the microbiological and molecular characterization of Q54, a prolate-headed virulent lactococcal phage that was recently proposed to form a new lactococcal phage species (26). So far, phage Q54 is unique, and it was isolated after causing a fermentation failure during the manufacture of sour cream. Its very narrow host spectrum combined with its relative sensitivity to temperature (inability to propagate above 34°C) and to natural phage resistance mechanisms (AbiQ and AbiT) probably explains why this phage has been rarely isolated in fermentation facilities.

Determination of the complete genomic sequence of Q54 confirmed that this phage clearly belongs to a different group, despite its morphological relatedness to the prolate-headed c2 species. The 26,537-bp dsDNA genome was shown to have cohesive termini (cos-type phage) with several features common to other lactococcal phages such as direct and inverted repeats, as well as an A/T-rich region close to the cos site (13, 19, 20, 61, 62). Nonetheless, the cos site [CCAA(N10)AACT] of phage Q54 is atypical. To our knowledge, this is the first L. lactis phage to deviate from the lactococcal phage consensus cos site [TCAN(N4-7)NACT] (62).

Another distinctive feature of phage Q54 is the very low degree of conservation of its deduced ORFs with proteins in databases. Globally, only limited protein similarity was observed with structural proteins of lactococcal c2-like phages (22 to 34% amino acid identity). Interestingly, a few early gene products from Q54 (ORF1, ORF35, ORF40, and ORF41) were similar to early expressed proteins from lactococcal phages of the 936 species. A whole-genome comparison between Q54 and c2 (Fig. 6), clearly suggests the presence of an extra module at the end of the late gene cluster of Q54. Transcriptional analyses demonstrated that this extra module is transcribed early after infection. Two diverging early modules separated by the cos site are thus present in the phage Q54 genome. This is, to our knowledge, the first report of a lactic acid bacterial phage with such a genomic organization. It is tempting to propose that phage Q54 is the result of past recombination events involving 936- and c2-like phages. Genetic drift and recombination events would have then modified the genome of Q54 to its present form. A notable supporting observation was the presence of a conserved DNA region between Q54 and a 936-like phage that is located at the boundary of the late and early module and falls within the endolysin gene (orf34). This region might have been a point of homologous recombination. Phage Q54 is clearly not adapted for optimum propagation, as suggested by its relatively long latent period (for a lactococcal phage) and small burst size. It is possible that Q54 is currently evolving to gain more fitness in order to replicate more efficiently.

Three of the putative ORFs encoded by Q54 (ORF4, ORF11, and ORF24) were more closely related to proteins from P335-like phages than to those from any other phages. ORF131 and Sak2 from the type phage P335, which are homologous to ORF4 and ORF11 of phage Q54, respectively, were previously shown to be involved in homologous recombination events with the host chromosome (7). In phage P335, sak2 is flanked by orf131 on one side and a gene encoding an SSB protein on the other side. In phage Q54, six genes showing no relatedness to any lactococcal phage or bacterial strain separate orf4 and orf11. However, a gene coding for an SSB protein from a lactococcal host immediately follows orf11 in the genome of phage Q54. These observations strongly suggest that Q54 acquired these genes through homologous recombination with prophages from the chromosome of an L. lactis host. Whether these three genes were acquired simultaneously as a functional module, followed by genetic drift and insertion of six additional genes, or whether they were acquired separately through two or more recombination events is unknown.

For strict lytic phages such as members of the 936 and c2 lactococcal phage groups, homologous recombination is less likely to occur due to the absence of temperate members (15). Consequently, finding Q54 genes homologous to bacterial or prophage sequences is intriguing. Some authors suggested that temperate/lytic phages evolve by horizontal gene transfer with prophages residing in the host chromosome, whereas strictly virulent phages evolve by point mutations and small indels but rarely exchange DNA outside their group (15, 35). It is not excluded that Q54 could have had a temperate lifestyle before losing its lysogeny module to become strictly virulent. However, no remnant of a lysogeny module could be found in Q54, which could support this hypothesis.

Posttranslational modifications of structural proteins.

The SDS-PAGE and LC-MS/MS analyses strongly suggest that the MCP of phage Q54 is processed. Cleavage of the N-terminal part of the protein, in addition to cross-linking, appears necessary for building the mature viral capsid. A similar observation was made for the type phage c2 where N-terminal sequencing showed that the MCP was lacking its 205 N-terminal residues, in addition to being cross-linked (48). Cross-linking and proteolytic cleavage of the MCP subunits during assembly have been reported for a number of other phages (1, 16, 29, 34, 46, 53, 63).

Programmed +1 translational frameshifting in tail structural genes.

Programmed translational frameshifting (−1 type) seems to be relatively common among dsDNA phages, as revealed by a recent study (79), which identified potential signals for such frameshifting in about 70% of the analyzed phage genomes. Typical frameshift signals were found within the major tail protein and an overlapping gene. Only one example of a natural −2 frameshift event was demonstrated for phage Mu (79). Two examples of +1 translational frameshifting have been confirmed in E. coli, which includes RF2 (17), and for recombinant human transferrin (25). In the latter case, frameshifting occurred at a rate of 2 to 4% and was due to the presence of a CCC.UGA “shifty stop” at the end of the gene. This frequency was much lower than the 50% rate observed for RF2 (17). In phages, however, +1 translational frameshifts have been reported only for the temperate phage PSA from L. monocytogenes (80). In this case, the major capsid protein and major tail protein were both extended in the C-terminal ends at an estimated frequency of 25%. The CCC.UGA and CCC.UCA slippery sequences were shown to be involved in this mechanism (80). Our LC-MS/MS analysis revealed a programmed + 1 translational frameshifting event involving a “shifty stop” and secondary structures and occurring between the major tail protein (ORF23) and the receptor-binding protein (ORF24) of phage Q54. According to the recent study by Xu et al. (2004), this would represent the first case of translational coupling between an MTP and an RBP (79). Also, based on the relative band intensities on SDS-PAGE, we estimate this event to occur at a frequency of approximately 25%. Since the RBP (ORF24) alone was not detected in the virion structure, it suggests that only a fraction of the MTP is fused to the RBP. This chimeric protein would be most likely located at the distal part of the tail for host recognition, while the other single units of the MTP would probably be associated with the chimeric MTP/RBP for completion of the tail.

In summary, we have shown that the lytic phage Q54 represents a new lactococcal phage species. Despite a familiar morphology, phage Q54 has a novel genome architecture and a distinctive transcriptional map, both of which suggest past recombination events with the genomes of members of the three most common L. lactis phage groups. However, the degree of protein relatedness is very low, suggesting that the breakpoint likely occurred a long time ago. Such DNA shuffling through evolution may have led to the unusual +1 translational frameshifting in the tail structural genes of phage Q54.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Tremblay for phage DNA preparation and J. Garneau for host range assays.

This study was funded by a strategic grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altermann, E., J. R. Klein, and B. Henrich. 1999. Primary structure and features of the genome of the Lactobacillus gasseri temperate bacteriophage (phi)adh. Gene 236:333-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beres, S. B., G. L. Sylva, K. D. Barbian, B. Lei, J. S. Hoff, N. D. Mammarella, M.-Y. Liu, J. C. Smoot, S. F. Porcella, L. D. Parkins, D. S. Campbell, T. M. Smith, J. K. McCormick, D. Y. M. Leung, P. M. Schlievert, and J. M. Musser. 2002. Genome sequence of a serotype M3 strain of group A Streptococcus: phage-encoded toxins, the high-virulence phenotype, and clone emergence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:10078-10083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blatny, J. M., L. Godager, M. Lunde, and I. F. Nes. 2004. Complete genome sequence of the Lactococcus lactis temperate phage phiLC3: comparative analysis of phiLC3 and its relatives in lactococci and streptococci. Virology 318:231-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolotin, A., P. Wincker, S. Mauger, O. Jaillon, K. Malarme, J. Weissenbach, S. D. Ehrlich, and A. Sorokin. 2001. The complete genome sequence of the lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis IL1403. Genome Res. 11:731-753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouchard, J. D., E. Dion, F. Bissonnette, and S. Moineau. 2002. Characterization of the two-component abortive phage infection mechanism AbiT from Lactococcus lactis. J. Bacteriol. 184:6325-6332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bouchard, J. D., and S. Moineau. 2000. Homologous recombination between a lactococcal bacteriophage and the chromosome of its host strain. Virology 270:65-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouchard, J. D., and S. Moineau. 2004. Lactococcal phage genes involved in sensitivity to AbiK and their relation to single-strand annealing proteins. J. Bacteriol. 186:3649-3652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brondsted, L., S. Ostergaard, M. Pedersen, K. Hammer, and F. K. Vogensen. 2001. Analysis of the complete DNA sequence of the temperate bacteriophage TP901-1: evolution, structure, and genome organization of lactococcal bacteriophages. Virology 283:93-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brüssow, H., and F. Desiere. 2001. Comparative phage genomics and the evolution of Siphoviridae: insights from dairy phages. Mol. Microbiol. 39:213-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlton, R. M., W. H. Noordman, B. Biswas, E. D. de Meester, and M. J. Loessner. 2005. Bacteriophage P100 for control of Listeria monocytogenes in foods: genome sequence, bioinformatic analyses, oral toxicity study, and application. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 43:301-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chandry, P. S., S. C. Moore, J. D. Boyce, B. E. Davidson, and A. J. Hillier. 1997. Analysis of the DNA sequence, gene expression, origin of replication and modular structure of the Lactococcus lactis lytic bacteriophage sk1. Mol. Microbiol. 26:49-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chandry, P. S., S. C. Moore, B. E. Davidson, and A. J. Hillier. 1994. Analysis of the cos region of the Lactococcus lactis bacteriophage sk1. Gene 138:123-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chibani Azaiez, S. R., I. Fliss, R. E. Simard, and S. Moineau. 1998. Monoclonal antibodies raised against native major capsid proteins of lactococcal c2-like bacteriophages. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4255-4259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chopin, A., A. Bolotin, A. Sorokin, S. D. Ehrlich, and M. Chopin. 2001. Analysis of six prophages in Lactococcus lactis IL1403: different genetic structure of temperate and virulent phage populations. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:644-651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conway, J. F., R. L. Duda, N. Cheng, R. W. Hendrix, and A. C. Steven. 1995. Proteolytic and conformational control of virus capsid maturation: the bacteriophage HK97 system. J. Mol. Biol. 253:86-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Craigen, W. J., and C. T. Caskey. 1986. Expression of peptide chain release factor 2 requires high-efficiency frameshift. Nature 322:273-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crutz-Le Coq, A. M., B. Cesselin, J. Commissaire, and J. Anba. 2002. Sequence analysis of the lactococcal bacteriophage bIL170: insights into structural proteins and HNH endonucleases in dairy phages. Microbiology 148:985-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cue, D., and M. Feiss. 1993. The role of cosB, the binding site for terminase, the DNA packaging enzyme of bacteriophage lambda, in the nicking reaction. J. Mol. Biol. 234:594-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cue, D., and M. Feiss. 1993. A site required for termination of packaging of the phage lambda chromosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:9290-9294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curtis, F. A., P. Reed, and G. J. Sharples. 2005. Evolution of a phage RuvC endonuclease for resolution of both Holliday and branched DNA junctions. Mol. Microbiol. 55:1332-1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desiere, F., S. Lucchini, and H. Brüssow. 1999. Comparative sequence analysis of the DNA packaging, head, and tail morphogenesis modules in the temperate cos-site Streptococcus thermophilus bacteriophage Sfi21. Virology 260:244-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Desiere, F., S. Lucchini, C. Canchaya, M. Ventura, and H. Brüssow. 2002. Comparative genomics of phages and prophages in lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 82:73-91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Desiere, F., C. Mahanivong, A. J. Hillier, P. S. Chandry, B. E. Davidson, and H. Brüssow. 2001. Comparative genomics of lactococcal phages: insight from the complete genome sequence of Lactococcus lactis phage BK5-T. Virology 283:240-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Smit, M. H., J. van Duin, P. H. van Knippenberg, and H. G. van Eijk. 1994. CCC.UGA: a new site of ribosomal frameshifting in Escherichia coli. Gene 143:43-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deveau, H., S. J. Labrie, M. C. Chopin, and S. Moineau. 2006. Biodiversity and classification of lactococcal phages. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:4338-4346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Domingues, S., A. Chopin, S. D. Ehrlich, and M.-C. Chopin. 2004. The lactococcal abortive phage infection system AbiP prevents both phage DNA replication and temporal transcription switch. J. Bacteriol. 186:713-721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duda, R. L. 1998. Protein chainmail: catenated protein in viral capsids. Cell 94:55-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duda, R. L., K. Martincic, Z. Xie, and R. W. Hendrix. 1995. Bacteriophage HK97 head assembly. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 17:41-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duplessis, M., and S. Moineau. 2001. Identification of a genetic determinant responsible for host specificity in Streptococcus thermophilus bacteriophages. Mol. Microbiol. 41:325-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emond, E., E. Dion, S. A. Walker, E. R. Vedamuthu, J. K. Kondo, and S. Moineau. 1998. AbiQ, an abortive infection mechanism from Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4718-4756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emond, E., B. J. Holler, I. Boucher, P. A. Vandenbergh, E. R. Vedamuthu, J. K. Kondo, and S. Moineau. 1997. Phenotypic and genetic characterization of the bacteriophage abortive infection mechanism AbiK from Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1274-1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall, T. A. 1999. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41:95-98. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hatfull, G. F., and G. J. Sarkis. 1993. DNA sequence, structure and gene expression of mycobacteriophage L5: a phage system for mycobacterial genetics. Mol. Microbiol. 7:395-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hendrix, R. W., M. C. M. Smith, R. N. Burns, M. E. Ford, and G. F. Hatfull. 1999. Evolutionary relationships among diverse bacteriophages and prophages: all the world's a phage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:2192-2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ito, N., S. E. V. Phillips, C. Stevens, Z. B. Ogel, M. J. McPherson, J. N. Keen, K. D. S. Yadav, and P. F. Knowles. 1991. Novel thioether bond revealed by a 1.7 Å crystal structure of galactose oxidase. Nature 350:87-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jarvis, A. W. 1984. Differentiation of lactic streptococcal phages into phage species by DNA-DNA homology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 47:343-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jarvis, A. W., G. F. Fitzgerald, M. Mata, A. Mercenier, H. Neve, I. B. Powell, C. Ronda, M. Saxelin, and M. Teuber. 1991. Species and type phages of lactococcal bacteriophages. Intervirology 32:2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Josephsen, J., N. Andersen, H. Behrndt, E. Brandsborg, G. Christiansen, M. B. Hansen, S. Hansen, E. W. Nielsen, and F. K. Vogensen. 1994. An ecological study of lytic bacteriophages of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris isolated in a cheese plant over a five year period. Int. Dairy J. 4:123-140. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Labrie, S., and S. Moineau. 2002. Complete genomic sequence of bacteriophage ul36: demonstration of phage heterogeneity within the P335 quasi-species of lactococcal phages. Virology 296:308-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Labrie, S., N. Vukov, M. J. Loessner, and S. Moineau. 2004. Distribution and composition of the lysis cassette of Lactococcus lactis phages and functional analysis of bacteriophage ul36 holin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 233:37-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Larsen, B., R. F. Gesteland, and J. F. Atkins. 1997. Structural probing and mutagenic analysis of the stem-loop required for Escherichia coli dnaX ribosomal frameshifting: programmed efficiency of 50%. J. Mol. Biol. 271:47-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levin, M. E., R. W. Hendrix, and S. R. Casjens. 1993. A programmed translational frameshift is required for the synthesis of a bacteriophage lambda tail assembly protein. J. Mol. Biol. 234:124-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lillehaug, D. 1997. An improved plaque assay for poor plaque-producing temperate lactococcal bacteriophages. J. Appl. Microbiol. 83:85-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu, J., and A. Mushegian. 2004. Displacements of prohead protease genes in the late operons of double-stranded-DNA bacteriophages. J. Bacteriol. 186:4369-4375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lubbers, M. W., L. J. Ward, T. P. Beresford, B. D. Jarvis, and A. W. Jarvis. 1994. Sequencing and analysis of the cos region of the lactococcal bacteriophage c2. Mol. Gen. Genet. 245:160-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lubbers, M. W., N. R. Waterfield, T. P. Beresford, R. W. Le Page, and A. W. Jarvis. 1995. Sequencing and analysis of the prolate-headed lactococcal bacteriophage c2 genome and identification of the structural genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:4348-4356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Madera, C., C. Monjardin, and J. E. Suarez. 2004. Milk contamination and resistance to processing conditions determine the fate of Lactococcus lactis bacteriophages in dairies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:7365-7371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mahanivong, C., J. D. Boyce, B. E. Davidson, and A. J. Hillier. 2001. Sequence analysis and molecular characterization of the Lactococcus lactis temperate bacteriophage BK5-T. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3564-3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marchler-Bauer, A., J. B. Anderson, P. F. Cherukuri, C. DeWeese-Scott, L. Y. Geer, M. Gwadz, S. He, D. I. Hurwitz, J. D. Jackson, Z. Ke, C. J. Lanczycki, C. A. Liebert, C. Liu, F. Lu, G. H. Marchler, M. Mullokandov, B. A. Shoemaker, V. Simonyan, J. S. Song, P. A. Thiessen, R. A. Yamashita, J. J. Yin, D. Zhang, and S. H. Bryant. 2005. CDD: a Conserved Domain Database for protein classification. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:192-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marchler-Bauer, A., and S. H. Bryant. 2004. CD-Search: protein domain annotations on the fly. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:327-331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martin, A. C., R. Lopez, and P. Garcia. 1998. Pneumococcal bacteriophage Cp-1 encodes its own protease essential for phage maturation. J. Virol. 72:3491-3494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moineau, S. 1999. Applications of phage resistance in lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 76:377-382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moineau, S., E. Durmaz, S. Pandian, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1993. Differentiation of two abortive mechanisms by using monoclonal antibodies directed toward lactococcal bacteriophage capsid proteins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:202-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moineau, S., and C. Levesque. 2005. Control of bacteriophages in industrial fermentations, p. 285-296. In E. Kutter and A. Sulakvelidze (ed.), Bacteriophages: biology and applications. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla.

- 57.Moineau, S., S. Pandian, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 1994. Evolution of a lytic bacteriophage via DNA acquisition from the Lactococcus lactis chromosome. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1832-1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Obregon, V., P. Garcia, R. Lopez, and J. L. Garcia. 2003. VO1, a temperate bacteriophage of the type 19A multiresistant epidemic 8249 strain of Streptococcus pneumoniae: analysis of variability of lytic and putative C5 methyltransferase genes. Microb. Drug Resist. 9:7-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.O'Flaherty, S., A. Coffey, R. Edwards, W. Meaney, G. F. Fitzgerald, and R. P. Ross. 2004. Genome of staphylococcal phage K: a new lineage of Myoviridae infecting gram-positive bacteria with a low G+C content. J. Bacteriol. 186:2862-2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ostergaard, S., L. Brondsted, and F. K. Vogensen. 2001. Identification of a replication protein and repeats essential for DNA replication of the temperate lactococcal bacteriophage TP901-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:774-781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Parreira, R., R. Valyasevi, A. L. Lerayer, S. D. Ehrlich, and M. C. Chopin. 1996. Gene organization and transcription of a late-expressed region of a Lactococcus lactis phage. J. Bacteriol. 178:6158-6165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Perrin, R., P. Billard, and C. Branlant. 1997. Comparative analysis of the genomic DNA terminal regions of the lactococcal bacteriophages from species c2. Res. Microbiol. 148:573-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Popa, M. P., T. A. McKelvey, J. Hempel, and R. W. Hendrix. 1991. Bacteriophage HK97 structure: wholesale covalent cross-linking between the major head shell subunits. J. Virol. 65:3227-3237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rakonjac, J., P. W. O'Toole, and M. Lubbers. 2005. Isolation of lactococcal prolate phage-phage recombinants by an enrichment strategy reveals two novel host range determinants. J. Bacteriol. 187:3110-3121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rohwer, F., and R. Edwards. 2002. The phage proteomic tree: a genome-based taxonomy for phage. J. Bacteriol. 184:4529-4535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 67.Schouler, C., S. D. Ehrlich, and M. C. Chopin. 1994. Sequence and organization of the lactococcal prolate-headed bIL67 phage genome. Microbiology 140:3061-3069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Seegers, J. F., S. McGrath, M. O'Connell-Motherway, E. K. Arendt, M. van de Guchte, M. Creaven, G. F. Fitzgerald, and D. van Sinderen. 2004. Molecular and transcriptional analysis of the temperate lactococcal bacteriophage Tuc2009. Virology 329:40-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Spinelli, S., V. Campanacci, S. Blangy, S. Moineau, M. Tegoni, and C. Cambillau. 2006. Modular structure of the receptor binding proteins of Lactococcus lactis phages: the RBP structure of the temperate phage TP901-1. J. Biol. Chem. 281:14256-14262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stanley, E., L. Walsh, A. van der Zwet, G. F. Fitzgerald, and D. van Sinderen. 2000. Identification of four loci isolated from two Streptococcus thermophilus phage genomes responsible for mediating bacteriophage resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 182:271-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sturino, J. M., and T. R. Klaenhammer. 2004. Bacteriophage defense systems and strategies for lactic acid bacteria. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 56:331-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Terzaghi, B. E., and W. E. Sandine. 1975. Improved medium for lactic streptococci and their bacteriophages. Appl. Microbiol. 29:807-813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tremblay, D. M., M. Tegoni, S. Spinelli, V. Campanacci, S. Blangy, C. Huyghe, A. Desmyter, S. Labrie, S. Moineau, and C. Cambillau. 2006. Receptor-binding protein of Lactococcus lactis phages: identification and characterization of the saccharide receptor-binding site. J. Bacteriol. 188:2400-2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Trotter, M., O. McAuliffe, M. Callanan, R. Edwards, G. F. Fitzgerald, A. Coffey, and R. P. Ross. 2006. Genome analysis of the obligately lytic bacteriophage 4268 of Lactococcus lactis provides insight into its adaptable nature. Gene 366:189-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.van Sinderen, D., H. Karsens, J. Kok, P. Terpstra, M. H. Ruiters, G. Venema, and A. Nauta. 1996. Sequence analysis and molecular characterization of the temperate lactococcal bacteriophage r1t. Mol. Microbiol. 19:1343-1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vegge, C. S., F. K. Vogensen, S. McGrath, H. Neve, D. van Sinderen, and L. Brondsted. 2006. Identification of the lower baseplate protein as the antireceptor of the temperate lactococcal bacteriophages TP901-1 and Tuc2009. J. Bacteriol. 188:55-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang, I. N., D. L. Smith, and R. Young. 2000. Holins: the protein clocks of bacteriophage infections. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:799-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Weigel, C., and H. Seitz. 2006. Bacteriophage replication modules. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 30:321-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Xu, J., R. W. Hendrix, and R. L. Duda. 2004. Conserved translational frameshift in dsDNA bacteriophage tail assembly genes. Mol. Cell 16:11-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zimmer, M., E. Sattelberger, R. B. Inman, R. Calendar, and M. J. Loessner. 2003. Genome and proteome of Listeria monocytogenes phage PSA: an unusual case for programmed +1 translational frameshifting in structural protein synthesis. Mol. Microbiol. 50:303-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zuker, M., D. H. Mathews, and D. H. Turner. 1999. Algorithms and thermodynamics for RNA secondary structure prediction: a practical guide in RNA biochemistry and biotechnology. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.