Abstract

Besides the established central role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (Parp-1) and Parp-2 in the maintenance of genomic integrity, accumulating evidence indicates that poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation may modulate epigenetic modifications under physiological conditions. Here, we provide in vivo evidence for the pleiotropic involvement of Parp-2 in both meiotic and postmeiotic processes. We show that Parp-2-deficient mice exhibit severely impaired spermatogenesis, with a defect in prophase of meiosis I characterized by massive apoptosis at pachytene and metaphase I stages. Although Parp-2−/− spermatocytes exhibit normal telomere dynamics and normal chromosome synapsis, they display defective meiotic sex chromosome inactivation associated with derailed regulation of histone acetylation and methylation and up-regulated X- and Y-linked gene expression. Furthermore, a drastically reduced number of crossover-associated Mlh1 foci are associated with chromosome missegregation at metaphase I. Moreover, Parp-2−/− spermatids are severely compromised in differentiation and exhibit a marked delay in nuclear elongation. Altogether, our findings indicate that, in addition to its well known role in DNA repair, Parp-2 exerts essential functions during meiosis I and haploid gamete differentiation.

Of all epigenetic regulatory mechanisms that control chromatin structure and genome integrity in response to DNA damage, the modifications of histones and other nuclear proteins by poly(ADP-ribose) polymers catalyzed by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs) play an immediate and crucial role. PARP enzymes contain a conserved catalytic domain and constitute a superfamily of 17 proteins, encoded by 17 different genes (1). PARP-1, the founding member, and PARP-2 are so far the only characterized enzymes whose catalytic activity is stimulated by DNA strand breaks and are active players in the base excision repair process (2, 3). Parp-1 and Parp-2 knockout mice and their derived cells are more sensitive both to ionizing radiation and to alkylating agents than their WT counterparts, thus supporting a role of both Parp-1 and Parp-2 proteins in the cellular response to DNA damage (4). Moreover, double Parp-1−/−Parp-2−/− embryos die at gastrulation, whereas a specific female lethality related to X chromosome instability is associated with the Parp-1+/−Parp-2−/− genotype (4).

Spermatogenesis is a highly ordered differentiation process that includes two successive cellular divisions (meiosis I and II) taking place without any intervening DNA replication and yielding genetically diverse haploid gametes. During meiotic prophase I, homologous chromosomes align, pair, and undergo meiotic recombination, three steps essential to ensure correct chromosome segregation in the reductional meiosis I division. These processes are dependent on accurate telomere clustering and subsequent formation of a meiosis-specific protein zipper, the synaptonemal complex, between paired homologues (5).

Several lines of evidence emphasize the prominent role of an increasing number of DNA repair-associated proteins, including ATM (6), BRCA1 (7), H2AX (8), MLH1 (9), and MSH5 (10) in mammalian gametogenesis. Knockout mouse models in which one of these genes is inactivated display male and/or female sterility. Epigenetic modifications also play a critical role at both meiotic and postmeiotic stages of spermatogenesis. Indeed, posttranslational modifications of histones were shown to promote double-strand break formation (11), facilitate recognition of homologous chromosomes (12), regulate chromosome segregation (13), and control spermatid differentiation (14). Thus, mice carrying mutations in genes encoding epigenetic regulators such as Suv39h (13), HR6B (14), UBR2 (15), and HR23B (16) display male infertility associated with pleiotropic defects of spermatogenesis.

Quite remarkably, poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation contributes substantially to both DNA repair mechanisms (4, 17) and epigenetic information in various physiological conditions (18–20). However, the functional relevance of these properties for mammalian meiosis remains elusive.

We have recently reported distinct expression patterns of Parp-1 and Parp-2 in the seminiferous epithelium (3). The expression of Parp-1 is restricted to the peripheral cell layer containing proliferating spermatogonia, whereas the Parp-2 signal is very homogeneously distributed throughout the seminiferous tubules, thus suggesting that Parp-2 could be crucial for several aspects of spermatogenesis. Here, we describe male hypofertility in Parp-2-deficient mice that relates to defects in both meiosis I and spermiogenesis.

Results

Parp-2-Deficient Male Mice Are Hypofertile Because of Abnormalities in Meiosis I and Spermiogenesis.

Parp-2 is highly expressed throughout the prepubertal wave of mouse spermatogenesis, as well as in elutriated pachytene spermatocytes and spermatids of adult mice (Fig. 1A), suggesting a role of this protein in the complex process of spermatogenesis. To test this hypothesis further, we performed breeding experiments with Parp-2 knockout mice and found that Parp-2-deficient males display an incompletely penetrant hypofertility (Fig. 1B). We therefore undertook an in-depth analysis of spermatogenesis in the sterile Parp-2-null males. At necropsy, the Parp-2−/− testes were markedly smaller than age-matched WT testes, and their weight was reduced by ≈70% (Fig. 1C). The epididymal sperm counts were reduced to less than 0.1% of those of WT mice, and the rare mutant spermatozoa were immobile and displayed a necrotic appearance (Fig. 1D). On histological sections, the twelve (I-XII) stages of the seminiferous epithelium cycle could be identified. However, this epithelium was clearly abnormal because (i) a large number of spermatocytes in meiotic prophase and metaphase I displayed obvious features of apoptosis or necrosis (compare dP in Fig. 1Eb with P in Fig. 1Ea and dM in Fig. 1Ef with M in 1Ee, and Fig. 5A, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site); and (ii) elongation of all of the spermatids beyond step 12 was delayed (compare St7, St9, St12, and St15 in Fig. 1 Ea, Ec, Ee, and Eg and 1 Eb, Ed, Ef, and Eh), and fully elongated, mature (step 16) spermatids, normally observed during epithelial stage VII, were either absent or displayed picnotic nuclei (compare dSt16 in Fig. 1Eb with St16 in Fig. 1Ea and Fig. 5A). All these abnormal germ cell types filled the Parp-2−/− epididymides, which only rarely contained spermatozoa, whereas WT epididymides contained spermatozoa only (Fig. 5 A and B). In keeping with these observations, FACS analysis of the frequency of the testicular cell types of Parp-2−/− versus WT mice revealed a relative increase of tetraploid cells, possibly reflecting meiosis I delay or demise of subsequent stages, and a corresponding drop in haploid cells (Fig. 6A, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Fig. 1.

Impaired spermatogenesis in Parp-2-deficient mice. (A) Parp-2 protein level in mouse germinal cells. Parp-2 expression in testis from WT newborn males between the ages of 1 and 5 weeks (Aa), testis from WT, Parp-1−/−, and Parp-2−/− adult males (Ab), and WT Sertoli cells, spermatocytes I, and spermatids purified by elutriation (Ac). (B) Impaired reproductive function in Parp-2-deficient male mice. A test experiment is shown in which 2-month-old males and females of WT (n = 7 mating pairs) and Parp-2−/− mice (n = 13 mating pairs) were mated over a period of 4 months. Although normal litter size (eight pups per litter) was obtained in WT intercrosses, a significant reduced litter size (less than or equal to three pups per litter) was observed in 15% of the Parp-2−/− intercrosses (P = 0.002 compared with WT), and no offspring were produced in 46% of the Parp-2−/− intercrosses (P = 0.002 compared with WT). Only males were affected because mutant females produced normal litters when mated with WT males (data not shown). (C) Overall size and weight of WT and Parp-2−/− testis from 6-month-old sterile mice. (D) Abnormal morphology of the rare spermatozoa present in Parp-2−/− caudal epididymides. Light microscope view of representative individual spermatozoa. (E) Histological analysis of spermatogenesis in Parp-2−/− and WT mice. The series (WT in Ea, Ec, Ee, and Eg; and Parp2−/− mutant in Eb, Ed, Ef, and Eh) follow the maturation sequence of spermatids from step 7, just before the onset of nuclear elongation, to step 15 corresponding to fully condensed and elongated spermatids. (Ea–Ed) Nuclei of Parp-2−/− spermatids are undistinguishable from their WT counterparts before and at the onset of nuclear elongation. This observation is in sharp contrast with the condition of immediate spermatozoa precursors (i.e., St16 in Ea), which display numerous elongated nuclear profiles in the WT testis, but scarce and picnotic nuclei in the mutant (dSt16 in Eb). (Ee and Ef) Nuclear elongation is markedly delayed in mutant spermatids at epithelial stage XII. (Eg and Eh) Nuclei of mutant spermatids show abnormal oval shapes at the time when nuclear elongation is completed in WT spermatids. (Ea–Eh) Note also the frequent occurrence of degenerating spermatocytes (dP and dM) and the absence of spermatid flagella (F) in the mutant seminiferous epithelium. F, spermatid, flagella; M, and dM metaphase and degenerating metaphase spermatocytes, respectively; P and dP, pachytene and degenerating pachytene spermatocytes, respectively; S, Sertoli cells; St5, St7, St 9, St12, St15, and St16, step 5, 7, 9, 12, 15, and 16 spermatids; dSt16, degenerating St16. Roman numerals indicate the stages of the seminiferous epithelium cycle. Semithin sections were stained with toluidine blue. (Scale bar in Eh: Ea and Eb, 12 μm; Ec–Eh, 8 μm.)

Increased Apoptosis in Parp-2-Deficient Testis.

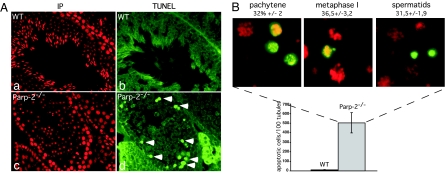

To investigate the causes of the morphological defects, we performed TUNEL staining on histological sections from Parp-2-deficient and WT testes. Parp-2−/− seminiferous tubules showed a high frequency of apoptotic cells in the spermatocyte and spermatid layers, whereas the peripheral germ cell layer containing the spermatogonia and preleptotene spermatocytes was unaffected (Fig. 2A, compare Ad with Ab). WT tubule sections only occasionally contained TUNEL-positive cells. Closer examination of the tubule sections identified cell death occurring at the same frequency (≈30%) in pachytene spermatocytes, spermatocytes in metaphases I, and round spermatids in accordance with the histological analysis (Fig. 2B). Accordingly, a high level of DNA fragmentation was detected by alkaline Comet assay in both primary spermatocytes and haploid cells (Fig. 6B). The identification of apoptosis in three different Parp-2-deficient germ cell types suggests a pleiotropic involvement of Parp-2 at both meiotic and postmeiotic stages of spermatogenesis. To gain deeper insights into the in vivo roles of Parp-2, we next looked for possible defects preceding apoptosis.

Fig. 2.

Increased apoptosis in Parp-2-deficient testis. (A) Increased TUNEL staining (green nuclear signal in Ad) in Parp-2−/− testis compared with a WT testis. (Aa and Ac) Same seminiferous tubule as in Ab and Ad, respectively: nuclei are stained in red with propidium iodide. (B) Histogram comparing the total number of apoptotic cells counted in 100 seminiferous tubule sections from Parp-2−/− and WT testes (Lower). Shown are high magnification of Parp-2−/− testis sections illustrating apoptosis in pachytene spermatocytes (stages VII and VIII), metaphase I cells (stage XII), and round spermatids (stage VI); the percentage of each apoptotic cell population is indicated (Upper).

Normal Telomere Clustering in Parp-2-Deficient Spermatocytes.

Apoptosis during prophase I has previously been associated with defects in telomere arrangement as described for Atm (21), H2ax (22, 23), and Sycp3 (24) knockout mice. We have recently identified an interaction of Parp-2 with the telomeric protein TRF2 (2), whose ortholog in Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Taz1, was found to be necessary for normal telomere clustering (25). In mouse spermatocytes, telomere repeats and associated proteins localize to telomere/nuclear envelope attachments (24). To determine whether Parp-2 may be involved in meiotic telomere dynamics, telomere and centromere redistribution was investigated by FISH to spermatocyte nuclei of WT and Parp-2−/− mice (Fig. 7A, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). In contrast to Parp-2's role in the maintenance of telomere integrity in somatic cells (2), we found normal telomere dynamics in Parp-2−/− spermatocytes, suggesting that it is dispensable for telomere attachment and clustering during the first meiotic prophase (Fig. 7A).

Impaired Meiotic Sex Chromosome Inactivation (MSCI) in Parp-2-Deficient Spermatocytes.

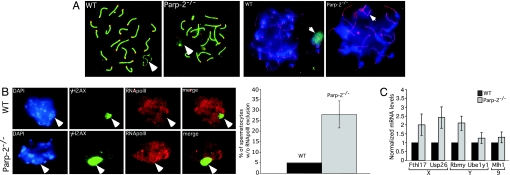

Pachytene spermatocyte apoptosis is often observed in cases of defects in chromosome structure or synaptic failure (10, 26). We therefore performed immunofluorescence on chromosome spreads using an anti-Sycp3 antibody specific for chromosome cores and staining the synaptonemal complex in combination with a CREST antiserum to label the centromeres. At pachytene, all autosomal homologues were fully synapsed in Parp-2−/− spermatocytes, as was the case in WT spermatocytes (Fig. 3A Left and Fig. 7B), suggestive of normal chromosomal synapsis of autosomes in the absence of Parp-2. Interestingly, in the same experiment, ≈30% of Parp-2−/− pachytene spermatocytes showed aberrant Sycp3 staining of the XY bivalent (Fig. 3A Left, full arrow). To further investigate this abnormality, we first carried out combined immunostaining of Sycp3 and Parp-2 on chromosomes spreads. In WT pachytene spermatocytes, but not in their mutant counterparts, Parp-2 was concentrated in the heterochromatic subnuclear region of the XY body (Fig. 3A Right). Additionally, Parp-2 and poly(ADP-ribose) formation colocalized with macrohistone H2A1 onto the XY body in elutriated WT pachytene spermatocytes (Fig. 8A, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Together, these findings suggest an involvement of Parp-2 in the function of the sex body during the pachytene stage of meiosis.

Fig. 3.

Impaired MSCI in Parp-2-deficient spermatocytes. (A Left) Indirect immunofluorescence of WT and Parp-2−/− pachytene spermatocytes. Merged image of anti-Sycp3 (green) staining the synaptonemal complex and the centromere antisera CREST (red). A representative Parp-2−/− cell displaying complete synapsis of autosomes but an aberrant staining of Sycp3 on the XY body (depicted by an arrow) is shown. (A Right) Indirect immunofluorescence of WT and Parp-2−/− pachytene spermatocytes. Shown are merged images of anti-Sycp3 (red) and anti-PARP-2 (green) showing the accumulation of Parp-2 in the XY body of WT cells and the absence of Parp-2 staining in Parp-2−/− cells. The XY body is identified as the highly heterochromatic DAPI-rich region localized at the nuclear periphery and displaying a typical α-like staining of Sycp3. (B Left) γH2AX (green)/RNA polymerase II (red) coimmunostaining of spread WT and Parp-2−/− pachytene spermatocytes, respectively, counterstained with DAPI (blue). RNA polII is excluded from the XY body (γH2AX-stained domain) in WT cells but not in a representative Parp-2−/− cell. Note the particular extended domain marked by γH2AX in the Parp-2−/− cell compared with the WT cell. (B Right) Histogram showing the accumulation of Parp-2−/− spermatocytes without RNA polII exclusion as compared with WT cells. (C) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of WT and Parp-2−/− testis RNA for X and Y chromosome genes known to be targets of MSCI and for one autosomal gene. Fthl17, Usp26, and Rbmy transcript levels (normalized against β-actin control) are increased in Parp-2−/− cells (2.01-fold, 2.42-fold, and 2.1-fold, respectively) whereas no significant change is observed for Ube1y1 and Mlh1 transcript levels. Chromosome localization of the genes analyzed is indicated.

The XY subnuclear domain is characterized by the transcriptional silencing of X- and Y-linked genes, an event termed MSCI, which is known to be mediated by dynamic histone modifications (27) and exclusion of RNA polymerase II (28). To investigate a potential involvement of Parp-2 in MSCI, we stained meiotic chromosome spreads of WT and Parp-2−/− testis with combined anti-γH2AX (labeling the sex body) and anti-RNA polymerase II antibodies. In WT pachytene cells, RNA polII was always excluded from the sex body, indicating normal MSCI. In contrast, we identified a homogeneous distribution of RNA polII, including the XY body in ≈30% of Parp-2−/− pachytene spermatocytes (Fig. 3B), suggesting failure in sex chromosome inactivation. We next determined whether specific X and Y genes that were previously reported to be targets of MSCI were affected by the absence of Parp-2. We compared the expression of the X-linked genes Fthl17 and Usp26, the Y-linked genes Rbmy and Ube1y1, and the autosomal gene Mlh1 in WT and Parp-2−/− testis by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 3C). As reported for H2ax−/− (22) and Brca1−/−;Trp-53+/− (29) mice, our data show that the sex-linked genes Fthl17, Usp26, and Rbmy were up-regulated by >2-fold in Parp-2-deficient mice relative to WT mice whereas the Y-linked gene Ube1y1 and the autosomal gene Mlh1 were not significantly affected. Together, these results provide evidence for defective transcriptional inactivation of the X- and/or Y-linked genes in Parp-2−/− spermatocytes that results in pachytene loss (Fig. 2B) as described for BRCA1 (7) and H2AX (22) mutant cells, although the alternative possibility of pachytene checkpoint-mediated spermatocyte elimination cannot be excluded (30).

Chromosome Missegregation in Parp-2-Deficient Metaphase I Cells.

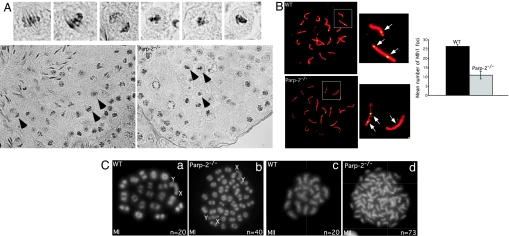

We next examined the defect in Parp-2−/− testes at metaphase I. Indeed, histological analysis of Parp-2−/− tubule sections at epithelial stage XII showed clusters of metaphase I spermatocytes undergoing cell death (Figs. 4A and 1E). Closer examination of these cells and coimmunostaining of sections using anti-phosphohistone H3, a metaphase marker, and anti-tubulin antibodies indicated the presence of abnormal metaphase I figures displaying essentially misaligned or lagging chromosomes combined with apparent abnormal bipolar spindle formation (Fig. 8B).

Proper orientation of homologous chromosomes in the meiotic spindle and accurate segregation at the first meiotic division depend on the formation of chiasmata that hold homologous chromosomes together (31). To investigate maintenance of chiasmata, we coimmunostained WT and Parp-2−/− chromosome spreads for detection of Sycp1, which identifies pachytene cells with complete synapsis (32), and Mlh1, a mismatch repair protein that marks sites of future chiasmata (33) (Fig. 4B). In WT spermatocytes, we observed an average of 26.3 ± 1 Mlh1 foci per nucleus (n = 100). By contrast, Parp-2−/− spermatocytes displayed an average of 10.8 ± 4 Mlh1 foci per spermatocyte (n = 100), indicating a failure to either form or maintain chiasmata in the absence of Parp-2. Accordingly, air-dried DAPI-stained chromosomal preparations of WT and Parp-2−/− spermatocytes revealed univalent chromosomes in ≈36 ± 6% (P = 0,006) of Parp-2−/− metaphase I cells (n = 75), translating in some cases to abnormal Parp-2−/− metaphase II figures, with more than the 20 chromosomes observed in WT metaphase I cells (Fig. 4C). The extensive occurrence of these chromosomal misconfigurations, together with the abnormal metaphase figures observed at the histological level, likely suggests premature separation of the abnormal bivalents, which can be expected to activate the spindle checkpoint and trigger the observed apoptosis.

Fig. 4.

Chromosome missegregation in Parp-2-deficient metaphase I cells. (A Lower) PAS-stained sections through WT and Parp-2−/− testis (stage XII) showing the accumulation of abnormal metaphase I cells in Parp-2−/− sections. (A Upper) Higher magnification of selected metaphases I (arrows) showing control metaphase and anaphase figures in WT sections and aberrant metaphase I figures containing lagging chromosomes and abnormal spindle configuration in Parp-2−/− sections. (B Left) Immunolabeling of WT and Parp-2−/− pachytene chromosome spreads with anti-Sycp1 (red) to label the synaptonemal complex and anti-Mlh1 (green) to label sites of future crossovers. Higher magnification of two autosomal bivalents showing one to two Mlh1 foci (arrows) per bivalent in WT cells and smaller or completely absent Mlh1 foci in Parp-2−/− cells. (B Right) Histogram for the comparative mean number of Mlh1 foci in WT and Parp-2−/− pachytene spermatocytes. (C) DAPI-stained, air-dried chromosome preparations of metaphase spermatocytes from WT and Parp-2-deficient spermatocytes. (Ca) Normal metaphase I chromosome from WT mice displaying 20 bivalents. (Cb) Metaphase I chromosomes from Parp-2−/− mice showing complete loss of bivalent association leading to an increase in univalents. (Cc) Normal metaphase II from WT mice displaying 20 chromosomes. (Cd) Aberrant metaphase II from Parp-2−/− mice (73 chromosomes counted) resulting from massive chromosome segregation in the preceding meiosis I division. MI, metaphase I; MII, metaphase II; n, number of bivalents or chromosomes counted in the representative cell.

Discussion

So far, no spontaneous phenotype has been ascribed to Parp-2-deficient mice. Here, we show that the absence of Parp-2 in mice leads to male hypofertility associated with important abnormalities at various steps throughout spermatogenesis that are in line with the high level of Parp-2 in meiotic and postmeiotic cells. Parp-2-deficient mice display defective MSCI linked with an up-regulation of X- and Y-linked genes, defective meiosis I characterized by segregation failure in the first meiotic division and delayed spermiogenesis. The initiation of meiotic recombination seems unaffected by the absence of Parp-2, because we found a WT-like distribution of γH2AX in the early prophase stages of Parp-2−/− spermatocytes, indicating that Spo11-dependent double-strand breaks are formed and repaired with WT-like kinetics (Fig. 9A, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Therefore, the numerous defects observed are probably not limited to an early, single defect but underline an essential and pleiotropic role of Parp-2 in both meiotic and postmeiotic processes.

The preferential localization of Parp-2 and poly(ADP-ribose) on the XY body in pachytene spermatocytes associated with a failure of Parp-2−/− spermatocytes to inactivate gonosomal genes suggests a role of Parp-2 in MSCI. How might Parp-2 activity regulate this process? The conserved intense signal of γH2AX on the sex body of Parp-2−/− spermatocytes indicates normal sex body formation and suggests that Parp-2 might not be required for the initiation of X- and Y-linked gene silencing by unpaired DNA (34, 35) but may rather be involved in the maintenance of an inactive chromatin state. Recently, the important and specific property of dynamic histone modifications in the regulation and the maintenance of the silenced transcriptional state of the XY body has been revealed (27, 36, 37). Accordingly, we found derailed regulation of histone methylation and acetylation in Parp-2−/− spermatocytes (Fig. 9B), providing evidence for an interplay between Parp-2 dependent poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation and different histone modifications that could account for various meiotic defects including MSCI. Alternatively, possible functional interaction of Parp-2 and a specific partner in the XY body that might govern transcriptional repression formally cannot be excluded. Based on the recent observations that sex-linked gene silencing initiated by MSCI might persist during spermiogenesis (35, 37), it will be pertinent to ask whether the absence of Parp-2 might also impair postmeiotic repression in spermatids. In addition, if this preinactivation process might control imprinted X chromosome inactivation in female embryos, as suggested (38, 39), it is tempting to propose that the impaired sex chromosome inactivation in Parp-2−/− spermatocytes could be related to the embryonic lethality of the Parp-1+/−Parp-2−/− mice (4). This hypothesis opens new challenging avenues in the quest for a potential function of Parp-2 activity in the epigenetic modifications regulating X chromosome inactivation.

Our data further show a reduced number of Mlh1 foci in Parp-2−/− spermatocytes associated with an accumulation of aberrant metaphase I spermatocytes displaying univalents and leading to aneuploid metaphase II spermatocytes. The latter may also contribute to the elevated number of tetraploids measured by FACS. Together, these data indicate segregation failure in the first meiotic division and assign an essential role of Parp-2 in the control of meiotic chromosome segregation. How could Parp-2 be connected to chiasmata integrity and faithful bivalent segregation? Although a possible direct participation of Parp-2 and/or poly (ADP-ribose) in the repair of double-strand breaks remains unclear, we can speculate that, during spermatogenesis, Parp-2 could participate in the resolution of recombination intermediates during double-strand break repair, which may be achieved by the association with, and poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of, yet-to-be identified recombination proteins. Accordingly, we have observed specific high affinity of Parp-2 for recombination intermediates (our unpublished data). Alternatively, by analogy to the proposed role of Parp-2 in the maintenance of centromeric heterochromatin integrity in somatic cells (4), it is likely that meiotic chromosome missegregation could be a direct consequence of defective centromeric heterochromatin in Parp-2−/− metaphase I spermatocytes. This hypothesis would then implicate Parp-2 in the control of centromeric integrity and/or cohesion either by the functional association with specific interactants or by its participation in the definition of the centromeric heterochromatin structure. Interestingly, a similar phenotype was previously described in mice knockout for the epigenetic regulator Suv39h (13). Additionally, Parp-2−/− metaphase I figures display abnormal spindle configurations. In this respect, it is interesting to note that poly(ADP-ribose) has been previously shown to be required for spindle assembly and maintenance in somatic cells (40). Together, these observations suggest that the metaphase I defect could additionally be related to a defect in spindle formation and argue for a possible unexpected role of Parp-2 in the maintenance of meiotic spindle integrity.

Another important observation reported here is the markedly retarded nuclear elongation process that leads to derailed spermiogenesis. These data suggest that Parp-2, in addition to the transition proteins, protamines, and histone variants, is required for normal spermatid differentiation (41, 42). It remains to be determined whether Parp-2-dependent poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of the testis-specific histone variants and/or basic proteins contributes to their sequential and highly regulated replacement necessary for proper chromatin condensation. This study would identify Parp-2 as an epigenetic regulator controlling the differentiation process of spermatids into spermatozoa in addition to the previously described chromatin modifier enzyme HR6B (14).

In conclusion, the present study provides in vivo evidence for the pleiotropic involvement of Parp-2 in both meiosis and spermiogenesis and opens the way to forthcoming fascinating issues that will investigate the multifunctional role of this protein throughout spermatogenesis. Finally, the essential roles of Parp-2 in spermatogenesis reported here raise the possibility that an impairment of this protein could be a novel and so far unrecognized cause of infertility in humans.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

Parp-2-deficient mouse lines (C57BL/6;129sv background) have been described (4). Six-month-old WT and Parp-2-deficient (Parp-2−/−) mice were used in all experiments. Incomplete penetrant hypofertility associated with derailed spermatogenesis was also identified in the 129sv background mice, thus likely ruling out any major influence of the genetic background (data not shown).

Testicular Cell Elutriation and Western Blot Analysis.

Testes were collected from 15 WT 6-week-old mice, and populations of primary spermatocytes and round spermatids were purified by centrifugal elutriation as described by Meistrich et al. (43). Sertoli cell cultures were prepared as reported (44). Testes at different ages of development and purified testicular cells were lysed in Laemmli buffer. Equivalent amounts of proteins were separated onto 10% SDS polyacrylamide gels, and Parp-2 was detected by using an anti-Parp-2 antibody (Yuc, 1:4,000) according to standard protocols (4).

Histology and TUNEL Assay.

For histological analysis, testes were perfusion-fixed with 2.5% buffered glutaraldehyde and embedded in epon, and 2 μm-thick sections were stained with toluidine blue. Stages of the seminiferous epithelium cycle were identified according to established morphological criteria (45). For TUNEL assays, testes were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned at 5 μm. The TUNEL assays were performed with the ApoAlert DNA Fragmentation Assay Kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cytology and Immunocytochemistry.

For immunostaining, meiotic cell spreads were prepared by the drying-down technique (46) and stained according to standard protocols (2). Primary antibodies used for immunofluorescence were rabbit anti-Sycp1 (1:500), rabbit anti-Sycp3 (1:500) (C. Hoog, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden), rabbit anti-Parp-2 (Yuc 1:200), human anti-CREST (1:400; K. H. A. Choo, Murdoch Childrens Research Institute, Parkville, Australia), rabbit anti-γH2AX (F3 1:500; S. Muller, Institut de Biologie Moléculaire et Cellulaire, Strasbourg, France), mouse anti-RNA polymerase II (1:2,000; M. Vigneron, UMR7175, Strasbourg, France), mouse anti-Mlh1 (1:50; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). For studies of metaphase chromosomes, testis cell suspensions were prepared according to Wiltshire et al. (47) and exposed to 5 μM okadaic acid for 6 h to induce pachytene cells to enter metaphase I. Chromosome spreads were made by using the air-drying method and DAPI-stained (48).

Quantitative RT-PCR.

Quantitative RT-PCR using total testis RNA samples was performed by using the LightCycler FastStart DNA MasterPLUS SYBR Green I kit following the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany) in combination with the LightCycler Detection System. The PCR products were analyzed with the manufacturer's software. The following primer sequences were used : Fthl17-5′, 5′-CAGCAGGTCGACATTTTGAA-3′; Fthl17-3′, 5′-GGCTGAGCTTGTCAAAGAGG-3′; Usp26-5′, 5′-GAGGCCCAAAAGTACCAACA-3′; Usp26-3′, 5′-TTCCTGGGAGATTGGTTTTG-3′; Rbmy-5′, 5′-CAAGAAGAGACCACCATCCT-3′; Rbmy-3′, 5′-CTCCCAGAAGAACTCACATT-3′; Ube1y1-5′, 5′-TTCTTCCAAAAGCTGGATGG-3′; Ube1y1-3′, 5′-TTCCAGCAGAGGCTTACGAT-3′; β-actin-5′, 5′-CTGGCACCACACCTTCTACA-3′; β-actin-3′, 5′-CTTTTCACGGTTGGCCTTAG-3′; Mlh1-5′, 5′-GGGAGGACTCTGATGTGGAA-3′; Mlh1-3′, 5′-ACTCAAGACGCTGGTGAGGT-3′.

Supporting Materials and Methods.

Flow cytometric analysis of DNA content of testis cells, Comet assays of testis cells, analysis of meiotic telomere behavior, and additional cytology and immunocytochemistry are described in Supporting Materials and Methods, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank K. H. A. Choo, C. Hoog, B. Spyropoulos (York University, Toronto, ON, Canada), P. Moens (York University), C. Heyting (Wageningen University and Research Center, Wageningen, The Netherlands), S. Muller, and M. Vigneron for generous gifts of antibodies and protocols for meiotic chromosome spreads; N. Magroun for providing assistance with animal care; and S. Kimmins, A. P. Sibler, and N. Messadeq for insightful technical assistance. This work was supported by funds from Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer, Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer, Electricité de France, and Commissariat à l'Energie Atomique.

Abbreviations

- PARP

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- MSCI

meiotic sex chromosome inactivation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Amé J-C, Spenlehauer C, de Murcia G. Bio Essays. 2004;26:882–893. doi: 10.1002/bies.20085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dantzer F, Giraud-Panis M-J, Jaco I, Amé J-C, Schultz I, Blasco M, Koering CE, Gilson E, Ménissier-de Murcia J, de Murcia G, et al. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1595–1607. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.4.1595-1607.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schreiber V, Amé J-C, Dollé P, Schultz I, Rinaldi B, Fraulob V, Ménissier-de Murcia J, de Murcia G. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23028–23036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202390200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ménissier-de Murcia J, Ricoul M, Tartier L, Niedergang C, Huber A, Dantzer F, Schreiber V, Amé J-C, Dierich A, LeMeur M, et al. EMBO J. 2003;22:2255–2263. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Page SL, Hawley RS. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:525–558. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.155141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barlow C, Liyanage M, Moens PB, Tarsounas M, Nagashima K, Brown K, Rottinghaus S, Jackson SP, Tagle D, Ried T, et al. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1998;125:4007–4017. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.20.4007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu X, Aprelikova O, Moens P, Deng CX, Furth PA. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2003;130:2001–2012. doi: 10.1242/dev.00410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Celeste A, Petersen S, Romanienko PJ, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Chen HT, Sedelnikova OA, Reina-San-Martin B, Coppola V, Meffre E, Difilippantonio MJ, et al. Science. 2002;296:922–927. doi: 10.1126/science.1069398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker SM, Plug AW, Prolla TA, Bronner CE, Harris AC, Yao X, Christie DM, Monell C, Arnheim N, Bradley A, et al. Nat Genet. 1996;13:336–342. doi: 10.1038/ng0796-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edelmann W, Cohen PE, Kneitz B, Winand N, Lia M, Heyer J, Kolodner R, Pollard JW, Kucherlapati R. Nat Genet. 1999;21:123–127. doi: 10.1038/5075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maleki S, Keeney S. Cell. 2004;118:404–406. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prieto P, Shaw P, Moore G. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:906–908. doi: 10.1038/ncb1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters AH, O'Carroll D, Scherthan H, Mechtler K, Sauer S, Schofer C, Weipoltshammer K, Pagani M, Lachner M, Kohlmaier A, et al. Cell. 2001;107:323–337. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00542-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roest HP, van Klaveren J, de Wit J, van Gurp CG, Koken MH, Vermey M, van Roijen JH, Hoogerbrugge JW, Vreeburg JT, Baarends WM, et al. Cell. 1996;86:799–810. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80154-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwon YT, Xia Z, An JY, Tasaki T, Davydov IV, Seo JW, Sheng J, Xie Y, Varshavsky A. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:8255–8271. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.22.8255-8271.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ng JM, Vrieling H, Sugasawa K, Ooms MP, Grootegoed JA, Vreeburg JT, Visser P, Beems RB, Gorgels TG, Hanaoka F, et al. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1233–1245. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1233-1245.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ménissier-de Murcia J, Niedergang C, Trucco C, Ricoul M, Dutrillaux B, Mark M, Oliver FJ, Masson M, Dierich A, LeMeur M, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7303–7307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saxena A, Wong LH, Kalitsis P, Earle E, Shaffer LG, Choo KH. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2319–2329. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.19.2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu W, Ginjala V, Pant V, Chernukhin I, Whitehead J, Docquier F, Farrar D, Tavoosidana G, Mukhopadhyay R, Kanduri C, et al. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1105–1110. doi: 10.1038/ng1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tulin A, Spradling A. Science. 2003;299:560–562. doi: 10.1126/science.1078764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scherthan H, Jerratsch M, Dhar S, Wang YA, Goff SP, Pandita TK. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7773–7783. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.20.7773-7783.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fernandez-Capetillo O, Mahadevaiah SK, Celeste A, Romanienko PJ, Camerini-Otero RD, Bonner WM, Manova K, Burgoyne P, Nussenzweig A. Dev Cell. 2003;4:497–508. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00093-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernandez-Capetillo O, Liebe B, Scherthan H, Nussenzweig A. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:15–20. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liebe B, Alsheimer M, Hoog C, Benavente R, Scherthan H. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:827–837. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-07-0524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chikashige Y, Hiraoka Y. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1618–1623. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Revenkova E, Eijpe M, Heyting C, Hodges CA, Hunt PA, Liebe B, Scherthan H, Jessberger R. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:555–562. doi: 10.1038/ncb1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khalil AM, Boyar FZ, Driscoll DJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16583–16587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406325101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richler C, Ast G, Goitein R, Wahrman J, Sperling R, Sperling J. Mol Biol Cell. 1994;5:1341–1352. doi: 10.1091/mbc.5.12.1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turner JM, Aprelikova O, Xu X, Wang R, Kim S, Chandramouli GV, Barrett JC, Burgoyne PS, Deng CX. Curr Biol. 2004;14:2135–2142. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roeder GS, Bailis JM. Trends Genet. 2000;16:395–403. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerton JL, Hawley RS. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:477–487. doi: 10.1038/nrg1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meuwissen RL, Offenberg HH, Dietrich AJ, Riesewijk A, van Iersel M, Heyting C. EMBO J. 1992;11:5091–5100. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05616.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderson LK, Reeves A, Webb LM, Ashley T. Genetics. 1999;151:1569–1579. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.4.1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turner JM, Mahadevaiah SK, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Nussenzweig A, Xu X, Deng CX, Burgoyne PS. Nat Genet. 2005;37:41–47. doi: 10.1038/ng1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turner JM, Mahadevaiah SK, Ellis PJ, Mitchell MJ, Burgoyne PS. Dev Cell. 2006;10:521–529. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baarends WM, Wassenaar E, van der Laan R, Hoogerbrugge J, Sleddens-Linkels E, Hoeijmakers JH, de Boer P, Grootegoed JA. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1041–1053. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.3.1041-1053.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Namekawa SH, Park PJ, Zhang LF, Shima JE, McCarrey JR, Griswold MD, Lee JT. Curr Biol. 2006;16:660–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huynh KD, Lee JT. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:410–418. doi: 10.1038/nrg1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reik W, Ferguson-Smith AC. Nature. 2005;438:297–298. doi: 10.1038/438297a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang P, Jacobson MK, Mitchison TJ. Nature. 2004;432:645–649. doi: 10.1038/nature03061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meistrich ML, Mohapatra B, Shirley CR, Zhao M. Chromosoma. 2003;111:483–488. doi: 10.1007/s00412-002-0227-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Govin J, Caron C, Lestrat C, Rousseaux S, Khochbin S. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:3459–3469. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meistrich ML, Longtin J, Brock WA, Grimes SR, Jr, Mace ML. Biol Reprod. 1981;25:1065–1077. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod25.5.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tamai KT, Monaco L, Alastalo TP, Lalli E, Parvinen M, Sassone-Corsi P. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:1561–1569. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.12.8961266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Russel LD, Ettlin RA, Sinha-Hikim AP, Clegg ED. Histological and Histopathological Evaluation of the Testis. Clearwater, FL: Cache River Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peters AH, Plug AW, van Vugt MJ, de Boer P. Chromosome Res. 1997;5:66–68. doi: 10.1023/a:1018445520117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wiltshire T, Park C, Caldwell KA, Handel MA. Dev Biol. 1995;169:557–567. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Evans EP, Breckon G, Ford CE. Cytogenetics. 1964;15:289–294. doi: 10.1159/000129818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.