Abstract

Flagellar operons are divided into three classes with respect to their transcriptional hierarchy in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. The class 1 gene products FlhD and FlhC act together in an FlhD2C2 heterotetramer, which binds upstream of the class 2 promoters to facilitate binding of RNA polymerase. Class 2 expression is known to be enhanced by a disruption mutation in a flagellar gene, fliT. In this study, we purified FliT protein in a His-tagged form and showed that the protein prevented binding of FlhD2C2 to the class 2 promoter and inhibited FlhD2C2-dependent transcription. Pull-down and far-Western blotting analyses revealed that the FliT protein was capable of binding to FlhD2C2 and FlhC and not to FlhD alone. We conclude that FliT acts as an anti-FlhD2C2 factor, which binds to FlhD2C2 through interaction with the FlhC subunit and inhibits its binding to the class 2 promoter.

Bacterial flagellum consists of three structural parts, a basal body, a hook, and a filament, and is constructed in this order. More than 50 genes are specifically required for flagellar formation and function in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and Escherichia coli (18). These flagellar genes are organized into at least 15 operons, and their expression forms a highly organized cascade called a flagellar regulon (16, 20). In this regulon, flagellar operons are divided into three classes with respect to their transcriptional hierarchy. The flhDC operon is the sole one belonging to class 1, whose products, FlhD and FlhC, are absolutely required for class 2 expression (20, 22). Class 2 contains operons encoding component proteins of the hook-basal body structure and the flagellum-specific type III export apparatus as well as the flagellum-specific sigma factor σ28 (FliA) essential for class 3 expression (26). Class 3 contains operons encoding proteins involved in filament assembly and flagellar function. The σ28 activity is negatively controlled by an anti-σ28 factor, FlgM (19, 27). FlgM is excreted out of the cell through the flagellum-specific type III export apparatus upon completion of the hook-basal body structure, which achieves a tight coupling of the class 3 expression to the flagellar assembly process (8, 13).

Class 2 operons are transcribed by σ70-RNA polymerase in the presence of FlhD and FlhC, which assemble into an FlhD2C2 heterotetramer and bind to the DNA region upstream of the class 2 promoter (10, 21, 22). The FlhD2C2-binding site shows an imperfect symmetry comprising two 17- to 18-bp inverted repeats, called the FlhD2C2 box, separated by a 10- to 11-bp spacer (5, 10, 15, 22). In the FlhD2C2 complex, the FlhC subunit bears a DNA-binding activity, while the FlhD subunit strengthens its DNA-binding specificity and stabilizes the protein-DNA complex (4).

Several global regulators are known to affect class 2 expression. They include CsrA of E. coli and ClpXP and DnaK of S. enterica. The RNA-binding protein CsrA and the DnaK chaperone positively regulate class 2 expression through enhancing translation of flhDC mRNA (34) and through converting the native FlhD2C2 heterotetramer into a functional form (32), respectively. On the other hand, the ATP-dependent protease ClpXP negatively regulates class 2 expression through degradation of FlhD2C2 (33). In addition to these factors, two genes within the flagellar regulon, fliT and fliZ, have been shown to regulate class 2 transcription in S. enterica (17). Disruption of the fliT or fliZ gene increases or decreases, respectively, class 2 transcription without affecting class 1 transcription, suggesting that FliT and FliZ are negative and positive regulators, respectively, specific for class 2 operons. The fliT and fliZ genes belong to the fliDST and fliAZ operons, respectively, both of which are transcribed from both class 2 and class 3 promoters (9, 15, 38).

FliT is known also to be an export chaperone for the filament capping protein FliD (3, 7). Therefore, FliT is a dual-function protein involved in the control of protein export and gene expression. The chaperone function of FliT has been characterized at a molecular level, and FliT is believed to bind FliD to prevent its oligomerization prior to its export through the flagellum-specific type III export pathway (3, 7). However, molecular mechanisms underlying FliT-mediated transcriptional regulation of the class 2 operons remained unknown. This work was carried out to address this issue.

Overproduction and purification of FlhD/FlhC complex and His-FliT protein.

Plasmid pKK1211 carries the entire flhDC operon from S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain KK1004 (Table 1). Using this plasmid as a template, the flhC gene was PCR amplified with primers PTHHC1 and PTHHC2 (Table 2). The amplified product was digested with NdeI and BamHI and inserted into the corresponding site of pET19b to obtain pTH-hC. Similarly, the flhD gene was PCR amplified with primers PTHHCHD1 and PTHHD2 (Table 2). The amplified product was digested with BamHI and inserted into the corresponding site of pTH-hC. A plasmid carrying the flhD gene in the correct orientation was selected to obtain pTH-hCD. In this plasmid, the flhC and flhD genes are both transcribed from the T7 promoter, FlhC being synthesized in a His10-tagged form (His-FlhC) while FlhD was synthesized in its native form. Strain HMS174(DE3), harboring both pLysS and pTH-hCD, was grown at 30°C with shaking in 100 ml of LB containing 100 μg of ampicillin and 10 μg of chloramphenicol/ml. When the cell growth reached an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.4, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 1 mM. After further cultivation for 5 h, cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 1 ml of NA buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.0). After disruption of cells by sonication, the sample was centrifuged and the resulting supernatant was mixed with 50 μl of Ni+-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) agarose (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). After the mixture was shaken gently at 4°C for 30 min, the Ni+-NTA agarose was collected by centrifugation, washed five times with 1 ml of NB buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, pH 8.0), and resuspended in 50 μl of NC buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, pH 8.0). After centrifugation, the supernatant fractions were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and those containing His-FlhC (25 kDa) were pooled. Through this purification procedure, FlhD (13 kDa) was copurified with His-FlhC (data not shown), since these proteins exist as an FlhD2/His-FlhC2 complex (22). The pooled fractions were dialyzed twice against 1,000 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS: 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 4.3 mM Na2HPO4 · 7H2O, 1.4 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.5) and used in this study.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in the present study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium KK1004 | LT2 Δflj | 16 |

| E. coli | ||

| HMS174(DE3) | T7 expression host | 31 |

| JM109 | Cloning and expression host | 37 |

| Plasmidsa | ||

| pKK1012 | pBR322 fliC fliD′, Apr | 11 |

| pKK1211 | pBR322 flhD flhC, Apr | 14, 16, 36 |

| pSYIT1 | pHSG398 fliT, Cmr | 17 |

| pLysS | pACYC184 lys, Cmr | 31 |

| pSIIA100 | pTrc97A Δ(Ptac) PfliA-trrnB, Apr | 9 |

| pET19b | T7 expression vector for His10 tagging, Apr | 31 |

| pTH-hC | pET19b flhC(His-FlhC) | This study |

| pTH-hCD | pTH-hC flhD | This study |

| pTrc99A | tac expression vector, Apr | 2 |

| pTrc99A-hDC | pTrc99A flhD flhC | This study |

| pQE80L | T5 expression vector for His6 tagging, Apr | QIAGEN |

| pQE80L-iT | pQE80L fliT(His-FliT) | This study |

All of the flagellar genes on the plasmids were derived from S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain KK1004.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in the present studya

| Primer name | Nucleotide sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| CifOp1S | GGGGGTCGACGAATAATGATGCATAAAGCG |

| ICE4B | GGGGGATCCCTTCAGTGGTCTGCGCAATGG |

| ITf1B | GGGGGATCCACCTCAACCGTGGAGTTTAT |

| ITr1S | GGGGTCGACTTATGAGGCGCCAGGCGCAT |

| HDP3 | GGGGATCCGGAACAATGCATACATCCGA |

| MOTAP4 | GGCTGCAGGACAATGAACGCCCCTAT |

| PTHHC1 | GGGGCATATGAGTGAAAAAAGCATTGTTCA |

| PTHHC2 | GGGGATCCTTAAACAGCCTGTTCGATC |

| PTHHCHD1 | GCCTTCCCGGATCCATCACGGGGTGCGGCT |

| PTHHD2 | GGGGGATCCTCATGCCCTTTTCTTACG |

All of the primers were purchased from Hokkaido System Science (Sapporo, Japan).

Plasmid pSYIT1 carries the fliT gene from KK1004 (Table 1). Using this plasmid as a template, the fliT gene was PCR amplified with primers ITf1B and ITr1S (Table 2). The amplified product was digested with BamHI and SalI and inserted into the corresponding site of pQE80L to obtain pQE80L-iT. In this plasmid, FliT is expressed in a His6-tagged form (His-FliT). The His-FliT protein synthesized in strain JM109 harboring pQE80L-iT in the presence of 1 mM IPTG was affinity purified according to the method described previously (35). The purified His-FliT protein exhibited a single band at a position corresponding to 14.5 kDa in SDS-PAGE (data not shown).

FliT inhibits FlhD2C2-dependent transcription in vitro.

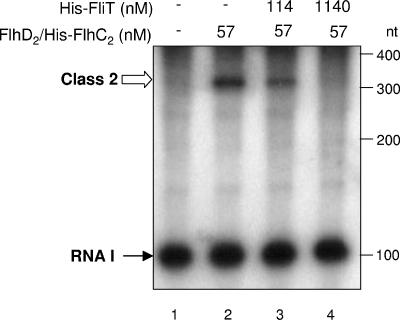

The His-FliT protein and FlhD2/His-FlhC2 complex purified above were used for in vitro analysis of σ70-dependent transcription from the class 2 promoter. For this analysis, plasmid pSIIA100 (Table 1) carrying the fliAZ promoter was used as a template. In this plasmid, first 31 nucleotides of the fliAZ mRNA fused to a 310-nucleotide RNA derived from the vector sequence are expressed from the fliAZ promoter, and the transcription terminates at the rrnB terminator (9). Therefore, if transcription occurred from the class 2 promoter, a 341-nucleotide RNA should be produced from this plasmid. In vitro transcription experiments were performed as described previously (35) with a reaction mixture (70 μl) containing 11.4 nM template DNA, 1 U of E. coli RNA polymerase holoenzyme (Epicenter, Madison, WI), 40 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 50 U of RNase inhibitor (Takara), 57 nM FlhD2/His-FlhC2, and various concentrations (0 to 1,140 nM) of His-FliT. After preincubation for 30 min at 37°C, the transcription reaction was initiated by addition of 4 nucleotides containing [α-32P]UTP (Amersham Biosciences, NJ) at a final concentration of 0.2 mM. After incubation for 20 min at 37°C, the reaction was terminated by addition of 116 μl of a stop solution (0.6 M sodium acetate [pH 5.5], 20 mM EDTA, 200 μg of tRNA/ml). RNAs were precipitated by ethanol and separated on 6% polyacrylamide gel containing 6 M urea. The labeled transcripts were detected by autoradiography. In the absence of FlhD2/His-FlhC2, only RNA I transcribed from the vector sequence was produced (Fig. 1, lane 1). In contrast, in the presence of FlhD2/His-FlhC2, both RNA I and the class 2 transcript were produced (Fig. 1, lane 2). When FliT was added to the transcription reaction mixture, the amount of class 2 transcript decreased in an FliT concentration-dependent manner, whereas that of RNA I was not affected (Fig. 1, lanes 3 and 4). This result indicates that FliT specifically inhibits transcription from the class 2 promoter in vitro, which is consistent with our previous result obtained from in vivo transcription analysis (17).

FIG. 1.

Effect of FliT on FlhD2C2-dependent transcription in vitro. Plasmid pSIIA100 carrying the fliAZ promoter was transcribed in vitro with E. coli RNA polymerase holoenzyme with or without 57 nM FlhD2/His-FlhC2 in the presence of [α-32P]UTP. His-FliT was added to the reaction mixture at the final concentration shown above each lane. Synthesized RNAs were separated on a 6% polyacrylamide gel containing 6 M urea and detected by autoradiography. nt, nucleotides.

FliT inhibits binding of FlhD2C2 to class 2 promoter.

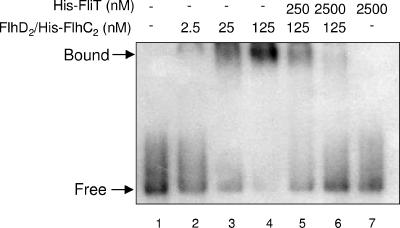

Next, these purified proteins were used for the gel mobility shift assay of the DNA fragment containing an FlhD2C2 box. A 433-bp DNA fragment containing the FlhD2C2 box of the fliDST promoter was PCR amplified from pKK1012 (Table 1), using primers CifOp1S and ICE4B (Table 2). The amplified product was gel purified and then labeled at the 5′ end with [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham Biosciences) by T4 polynucleotide kinase (Toyobo) and used as a probe. The binding reaction mixture (20 μl) contained 0.05 nM labeled probe DNA, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 5% glycerol, and various concentrations of FlhD2/His-FlhC2 (0 to 125 nM) and His-FliT (0 to 2,500 nM). The reaction mixture was incubated for 30 min at 37°C and subjected to electrophoresis at 4°C on a native 5% polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× TBE buffer (46 mM Tris base, 46 mM boric acid, 1 mM EDTA). Labeled DNAs were detected by autoradiography. As reported previously (22), the addition of FlhD2/His-FlhC2 to the binding reaction mixture gave the shifted band in an FlhD2/His-FlhC2 concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2, lanes 2 to 4). When 250 nM His-FliT was added together with 125 nM FlhD2/His-FlhC2, the amount of the shifted band decreased and a free probe band appeared (Fig. 2, lane 5). The shifted band disappeared when His-FliT was added at a 20-fold molar excess over FlhD2/His-FlhC2 (Fig. 2, lane 6). The addition of His-FliT alone gave no shifted band even at a 50,000-fold molar excess over the probe DNA (Fig. 2, lane 7), suggesting that FliT per se has no DNA-binding activity. These results indicate that FliT inhibits binding of FlhD2C2 to DNA.

FIG. 2.

Effect of FliT on binding of FlhD2C2 to the class 2 promoter. A 433-bp DNA fragment containing the FlhD2C2 box for the fliDST promoter was 5′-end labeled with 32P. Each reaction mixture contained 0.05 nM labeled DNA. After incubation with FlhD2/His-FlhC2 and/or FliT at the final concentrations indicated above the lanes, the DNA-protein mixtures were separated on a native 5% polyacrylamide gel and labeled DNA was detected by autoradiography. Positions of free and bound DNAs are indicated by arrows to the left.

Interaction of FliT with FlhD2C2.

The above results suggested that FliT binds to FlhD2C2 to inhibit its binding to DNA. In order to test this, a pull-down assay with His-FliT was applied to a cell lysate containing FlhD and FlhC. For this purpose, plasmid pTrc99A-hDC was constructed as follows. Using pKK1211 as a template, the flhDC operon was PCR amplified with primers HDP3 and MOTAP4 (Table 2). The amplified product was digested with BamHI and PstI and inserted into the corresponding site of pTrc99A to obtain pTrc99A-hDC. In this plasmid, the flhD and flhC genes were transcribed from the trc promoter, and FlhD and FlhC were synthesized in their native forms.

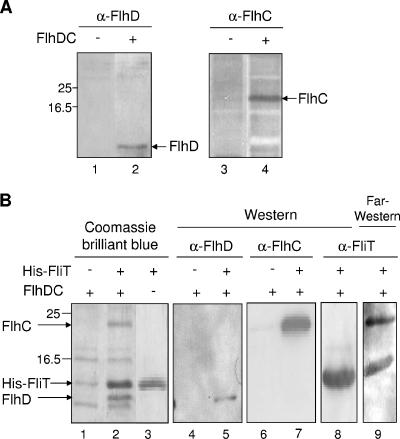

Strain JM109 harboring pTrc99A-hDC was grown at 30°C with shaking in 100 ml of LB containing 100 μg of ampicillin/ml. When the cell growth reached an OD600 of 0.4, IPTG was added to a final concentration of 1 mM. After further cultivation for 6 h, cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 1 ml of NA buffer containing 1 mg of lysozyme (Seikagaku Kogyo, Tokyo, Japan). After incubation on ice for 30 min, the cells were disrupted by sonication. Production of FlhD and FlhC in the cell was confirmed by Western blotting with anti-FlhD and anti-FlhC rabbit polyclonal antibodies (Fig. 3A). The sonicated sample was centrifuged, and 500 μl of the resulting supernatant was mixed with 50 μl of Ni+-NTA agarose in the presence of 17 μg of His-FliT. After the mixture was shaken gently at 4°C for 2 h, the Ni+-NTA agarose was collected by centrifugation, washed three times with 1 ml of NB buffer, and resuspended in 50 μl of NC buffer. After centrifugation, proteins in the supernatant were separated by SDS-PAGE and detected by Coomassie brilliant blue staining or Western blotting with anti-FlhD or anti-FlhC antibody. As shown in Fig. 3B, FlhD and FlhC were specifically recovered from the Ni+-NTA agarose containing His-FliT. This indicates that FliT interacts with either FlhD or FlhC in FlhD2C2 complex or with both of them.

FIG. 3.

Pull-down and far-Western blotting analyses of the interaction between FliT and FlhD2C2. (A) Detection of FlhD and FlhC proteins in the cell lysate used in the pull-down assay. The FlhD and FlhC proteins were detected by Western blotting with anti-FlhD (α-FlhD) and anti-FlhC (α-FlhC) antibodies, respectively. The following strains were used: lanes 1 and 3, JM109 harboring pTrc99A; lanes 2 and 4, JM109 harboring pTrc99A-hDC. Positions of FlhD and FlhC are indicated by arrows. Positions of molecular mass markers are shown to the left. (B) Interaction between His-FliT and FlhD2C2. Cell lysates described above were treated with Ni+-NTA agarose containing His-FliT (lanes 2, 3, 5, and 7 to 9) or no protein (lanes 1, 4, and 6). Proteins eluted with 250 mM imidazole were separated by SDS-PAGE and detected by Coomassie brilliant blue staining (lanes 1 to 3) or Western blotting with antibodies against FlhD (lanes 4 and 5), FlhC (lanes 6 and 7), and FliT (lane 8). Several nonspecific bands were seen in lanes 1 and 2. For far-Western blotting analysis, the same blotted membrane was treated with His-FliT, which was then detected with anti-FliT antibody (lane 9). The following cell lysate were subjected to pull-down assay: lanes 1, 2, and 4 to 9, JM109 harboring pTrc99A-hDC; lane 3, no cell lysate.

In order to determine which of the subunits is the target of FliT, FlhD and FlhC were analyzed by far-Western blotting with His-FliT according to the procedure described previously (25). The protein mixture obtained in the pull-down assay was separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. After treated for 30 min at room temperature in PBS containing 0.5% skim milk (Difco, Detroit, Mich.), the membrane was soaked in 20 ml of PBS containing 85 μg of His-FliT for 18 h at room temperature. After the membrane was washed twice with PBS, the His-FliT protein was detected using anti-FliT antibody (Fig. 3B, lane 9). A positive signal was specifically observed in the FlhC position as well as in the His-FliT position but not in the FlhD position. This indicates that FliT binds specifically to FlhC.

FliT acts as an anti-FlhD2C2 factor.

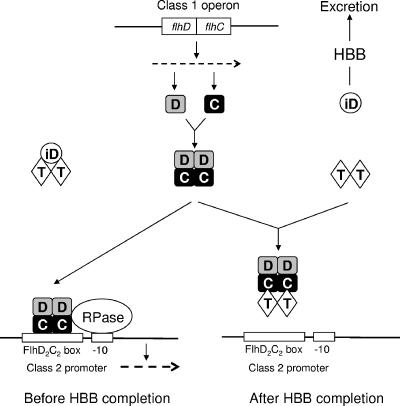

On the basis of the results obtained above, we conclude that FliT binds to FlhD2C2 through interaction with the FlhC subunit and inhibits its binding to the class 2 promoter, resulting in decreased expression of the class 2 operons. Since both FlhD and FlhC were copurified with His-FliT in the pull-down assay (Fig. 3B), FliT binding to the FlhC subunit is unlikely to dissociate the FlhD2C2 complex into individual subunits. Taken together, we propose that FliT is an anti-FlhD2C2 factor, which acts as an anti-activator factor specific for the flagellar master regulator (Fig. 4). However, because FliT can bind to FlhC that does not form FlhD2C2 complex (Fig. 3B, lane 9), we cannot exclude a possibility that FliT binds to FlhC monomer or dimer to inhibit formation of the FlhC2 or FlhD2C2 complex.

FIG. 4.

Model for molecular mechanism of FliT-mediated negative regulation of the flagellar class 2 operons. FliT acts as an anti-FlhD2C2 factor, which binds to FlhD2C2 through interaction with the FlhC subunit and inhibits its binding to class 2 promoters. FliD acts as an anti-anti-FlhD2C2 factor, which binds to FliT to prevent its interaction with FlhD2C2. After hook-basal body completion, FliD is excreted outside the cell through the hook-basal body complex with the aid of the flagellum-specific type III export apparatus. The horizontal line and broken arrow indicate DNA and mRNA, respectively. Abbreviations used: C, FlhC; D, FlhD; iD, FliD; T, FliT; RPase, σ70-RNA polymerase holoenzyme; −10, Pribnow box; HBB, hook-basal body.

FlhD2C2 acts not only as a master regulator for the flagellar regulon but also as a global regulator of various nonflagellar genes (29, 30). Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that FliT may also act as a global regulator via interaction with FlhC. Experiments are now in progress to test this possibility.

As an export chaperone, FliT was shown to possess two functional domains: one residing in the N-terminal region is required for its homodimerization, and the other residing in the C-terminal region forms amphipathic helices required for binding to FliD (3). However, because FlhC shows no apparent sequence similarity to FliD (data not shown), it is unclear whether FliT utilizes the same structural motif for recognition of FlhC and FliD. It was shown that FliT exists as a homodimer and binds to FliD at a 2:1 stoichiometry of FliT to FliD (3). At present, we have no data on the binding stoichiometry of FliT and FlhC, because our attempts to detect FliT-FlhC or FliT-FlhD2C2 complex by gel filtration chromatography or by chemical cross-linking analysis have not been successful (our unpublished result).

Connection between transcriptional regulation and protein export.

Recently, several substrate-specific chaperones for type III export systems have been shown not only to facilitate the export of their substrate proteins but also to regulate gene expression. They include SicA of S. enterica (6) and Spa15 of Shigella flexneri (28). This led to a hypothesis that the interaction between the type III chaperones and their substrates may play a role in coordinating cellular activities of protein export and gene expression (23). In the flagellum-specific type III export system, FlgN, an export chaperone for hook-filament junction proteins FlgK and FlgL (3, 7), was shown to regulate positively the translation of the class 3-specific anti-sigma factor gene flgM (1, 12). Because the flgN and flgKL genes are transcribed from both class 2 and class 3 promoters, their gene products are synthesized in the cytosol both before and after completion of hook-basal body assembly (13, 15). However, FlgK and FlgL are exported efficiently only after completion of hook-basal body assembly (24). On the basis of these facts, FlgK and FlgL were postulated to bind to FlgN within the cytosol during assembly of the hook-basal body structure, acting as anti-FlgN factors that inhibit flgM translation (1). This mechanism may play a role in the fine-tuning of class 3 expression in response to the stage of flagellar assembly.

By analogy with this, we would like to propose that the interplay among FlhD2C2, FliT, and FliD may play a role in the fine-tuning of class 2 expression in response to the stage of flagellar assembly (Fig. 4). Like FlgK and FlgL, FliD is exported outside the cell only after completion of hook-basal body assembly (24), though it is synthesized both before and after its completion (15). Therefore, during assembly of the hook-basal body structure, FliD may be accumulated within the cytosol and bind to FliT. In this condition, FlhD2C2 may be freed from FliT to activate class 2 transcription, leading to efficient expression of the component proteins of hook-basal body structure. This may enhance assembly of the hook-basal body complex. Once the hook-basal body is completed, FliD is exported outside the cell and FliT now freed from FliD binds to FlhD2C2 to inhibit the expression of class 2 operons. This results in lowered production of the hook-basal body components, which may contribute to saving biosynthetic energy in the bacterial cell. If this scenario were the case, FliD should act as an anti-anti-FlhD2C2 factor.

Acknowledgments

We thank Megumi Hayashida and Shusuke Katoh for their assistance in construction of plasmids, without which this work could not have been carried out. Radioisotope facilities were provided by the Advanced Science Research Center Tsushima Division, Okayama University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aldridge, P., J. Karlinsey, and K. T. Hughes. 2003. The type III secretion chaperone FlgN regulates flagellar assembly via a negative feedback loop containing its chaperone substrates FlgK and FlgL. Mol. Microbiol. 49:1333-1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann, E., B. Ochs, and K.-J. Abel. 1988. Tightly regulated tac promoter vectors useful for the expression of unfused and fused proteins in Escherichia coli. Gene 69:301-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett, J. C. Q., J. Thomas, G. M. Fraser, and C. Hughes. 2001. Substrate complexes and domain organization of the Salmonella flagellar export chaperones FlgN and FliT. Mol. Microbiol. 39:781-791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Claret, L., and C. Hughes. 2000. Functions of the subunits in the FlhD2C2 transcriptional master regulator of bacterial flagellum biogenesis and swarming. J. Mol. Biol. 303:467-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claret, L., and C. Hughes. 2002. Interaction of the atypical prokaryotic transcription activator FlhD2C2 with early promoters of the flagellar gene hierarchy. J. Mol. Biol. 321:185-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darwin, K. H., and V. L. Miller. 2001. Type III secretion chaperone-dependent regulation: activation of virulence genes by SicA and InvF in Salmonella typhimurium. EMBO J. 20:1850-1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraser, G. M., J. C. Q. Bennett, and C. Hughes. 1999. Substrate-specific binding of hook-associated proteins by FlgN and FliT, putative chaperones for flagellum assembly. Mol. Microbiol. 32:569-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes, K. T., K. L. Gillen, M. J. Semon, and J. E. Karlinsey. 1993. Sensing structural intermediates in bacterial flagellar assembly by export of a negative regulator. Science 262:1277-1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikebe, T., S. Iyoda, and K. Kutsukake. 1999. Structure and expression of the fliA operon of Salmonella typhimurium. Microbiology 145:1389-1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikebe, T., S. Iyoda, and K. Kutsukake. 1999. Promoter analysis of the class 2 flagellar operons of Salmonella. Genes Genet. Syst. 74:179-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inoue, Y. H., K. Kutsukake, T. Iino, and S. Yamaguchi. 1989. Sequence analysis of operator mutants of the phase-1 flagellin-encoding gene, fliC, in Salmonella typhimurium. Gene 85:221-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karlinsey, J., J. Lonner, K. T. Brown, and K. T. Hughes. 2000. Translation/secretion coupling by type III secretion systems. Cell 102:487-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kutsukake, K. 1994. Excretion of the anti-sigma factor through a flagellar substructure couples the flagellar gene expression with flagellar assembly in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Gen. Genet. 243:605-612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kutsukake, K. 1997. Autogenous and global control of the flagellar master operon, flhD, in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Gen. Genet. 254:440-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kutsukake, K., and N. Ide. 1995. Transcriptional analysis of the flgK and fliD operons of Salmonella typhimurium which encode flagellar hook-associated proteins. Mol. Gen. Genet. 247:275-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kutsukake, K., and T. Iino. 1994. Role of the FliA-FlgM regulatory system on the transcriptional control of the flagellar regulon and flagellar formation in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 176:3598-3605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kutsukake, K., T. Ikebe, and S. Yamamoto. 1999. Two novel regulatory genes, fliT and fliZ, in the flagellar regulon of Salmonella. Genes Genet. Syst. 74:287-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kutsukake, K., and T. Nambu. 2000. Bacterial flagellum: a paradigm for biogenesis of transenvelope supramolecular structures. Recent Res. Dev. Microbiol. 4:607-615. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kutsukake, K., S. Iyoda, K. Ohnishi, and T. Iino. 1994. Genetic and molecular analyses of the interaction between the flagellum-specific sigma and anti-sigma factors in Salmonella typhimurium. EMBO J. 13:4568-4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kutsukake, K., Y. Ohya, and T. Iino. 1990. Transcriptional analysis of the flagellar regulon of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 172:741-747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu, X., N. Fujita, A. Ishihama, and P. Matsumura. 1995. The C-terminal region of the α subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase is required for transcriptional activation of the flagellar level II operons by the FlhD/FlhC complex. J. Bacteriol. 177:5186-5188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu, X., and P. Matsumura. 1994. The FlhD/FlhC complex, a transcriptional activator of the Escherichia coli flagellar class II operons. J. Bacteriol. 176:7345-7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller, V. L. 2002. Connections between transcriptional regulation and type III secretion? Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5:211-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minamino, T., H. Doi, and K. Kutsukake. 1999. Substrate specificity switching of the flagellum-specific export apparatus during flagellar morphogenesis in Salmonella typhimurium. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 63:1301-1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nambu, T., and K. Kutsukake. 2000. The Salmonella FlgA protein, a putative periplasmic chaperone essential for flagellar P ring formation. Microbiology 146:1171-1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohnishi, K., K. Kutsukake, H. Suzuki, and T. Iino. 1990. Gene fliA encodes an alternative sigma factor specific for flagellar operons in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Gen. Genet. 221:139-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohnishi, K., K. Kutsukake, H. Suzuki, and T. Iino. 1992. A novel transcriptional regulation mechanism in the flagellar regulon of Salmonella typhimurium: an anti-sigma factor inhibits the activity of the flagellum-specific sigmar factor, σF. Mol. Microbiol. 6:3149-3157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parsot, C., E. Ageron, C. Penno, M. Mavris, K. Jamoussi, H. d'Hauteville, P. Sansonetti, and B. Demers. 2005. A secreted anti-activator, OspD1, and its chaperone, Spa15, are involved in the control of transcription by the type III secretion apparatus activity in Shigella flexneri. Mol. Microbiol. 56:1627-1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pruss, B. M., X. Liu, W. Hendrickson, and P. Matsumura. 2001. FlhD/FlhC-regulated promoters analyzed by gene array and lacZ gene fusions. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 197:91-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stafford, G. P., T. Ogi, and C. Hughes. 2005. Binding and transcriptional activation of non-flagellar genes by the Escherichia coli flagellar master regulator FlhD2C2. Microbiology 151:1779-1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Studier, F. W. 1991. Use of bacteriophage T7 lysozyme to improve an inducible T7 expression system. J. Mol. Biol. 219:37-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takaya, A., M. Matsui, T. Tomoyasu, M. Kaya, and T. Yamamoto. 2006. The DnaK chaperone machinery converts the native FlhD2C2 hetero-tetramer into a functional transcriptional regulator of flagellar regulon expression in Salmonella. Mol. Microbiol. 59:1327-1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomoyasu, T., A. Takaya, E. Isogai, and T. Yamamoto. 2003. Turnover of FlhD and FlhC, master regulator proteins for Salmonella flagellum biogenesis, by the ATP-dependent ClpXP protease. Mol. Microbiol. 48:443-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wei, B. L., A. M. Brun-Zinkernagel, J. W. Simecka, B. M. Pruss, P. Babitzke, and T. Romeo. 2001. Positive regulation of motility and flhDC expression by the RNA-binding protein CsrA of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 40:245-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamamoto, S., and K. Kutsukake. 2006. FljA-mediated posttranscriptional control of phase 1 flagellin expression in flagellar phase variation of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 188:958-967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yanagihara, S., S. Iyoda, K. Ohnishi, T. Iino, and K. Kutsukake. 1999. Structure and transcriptional control of the flagellar master operon of Salmonella typhimurium. Genes Genet. Syst. 74:105-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yokoseki, T., K. Kutsukake, K. Ohnishi, and T. Iino. 1995. Functional analysis of the flagellar genes in the fliD operon of Salmonella typhimurium. Microbiology 141:1715-1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]