Abstract

Regulated degradation of RpoS requires RssB and ClpXP protease. Mutations in hns increase both RpoS synthesis and stability, causing a twofold increase in synthesis and almost complete stabilization of RpoS, independent of effects on synthesis and independent of phosphorylation of RssB. This suggests that H-NS regulates an RssB inhibitor or inhibitors.

RpoS, a stress or stationary-phase sigma factor (σS), is regulated at multiple levels, including transcriptional regulation, translation by multiple small RNAs, and protein stability (for reviews, see references 8 and 12). One of the major regulators of RpoS turnover is RssB (SprE), a response regulator. RssB is necessary for degradation of RpoS, which usually occurs rapidly during exponential growth and slows down during stationary phase or stress responses (for a review, see reference 8). RssB can be phosphorylated by acetyl phosphate in vitro (2). The phosphorylated form of RssB binds RpoS with high affinity and presents it to the ATP-dependent ClpXP protease for degradation in vitro (23). The level of RssB is low and may be limiting for proteolysis under some conditions (18, 19). The specific sensor kinase(s) or phosphatase(s) that can phosphorylate or dephosphorylate RssB has not been identified.

H-NS is an abundant nucleoid-associated protein. The major role of H-NS is as a global transcriptional repressor for a large number of genes (for a review, see reference 5). Surprisingly, H-NS affects both RpoS mRNA translation and RpoS turnover in logarithmic growth; it was previously reported that there is a 10-fold increase in the RpoS synthesis rate, as well as a 10-fold increase in RpoS stability, in hns mutants (1, 22). The work described here was undertaken to ask whether these two effects are linked, for instance, by increased synthesis leading to inefficient degradation by swamping (titrating) the degradation machinery. We found that hns mutants have a strong effect on RpoS turnover, independent of any effect on RpoS synthesis, contrary to the titration model. The effect of hns mutants on RpoS degradation is an effect on RssB activity, leading to RpoS stabilization.

RpoS stability is increased dramatically in an hns mutant.

To confirm the involvement of H-NS in RssB-mediated RpoS degradation, isogenic strains carrying two different translational fusions of RpoS-LacZ were used. One fusion is a “long fusion,” RpoS750::LacZ, carrying 250 amino acids of RpoS, including the RssB interaction site at amino acid lysine-173; this fusion protein is subject to RssB-dependent ClpXP degradation (24). The other fusion, a “short fusion,” RpoS477::LacZ, carries the same upstream region but only 159 amino acids of RpoS; this fusion protein is stable (E. Massé, unpublished data). Cells were grown in LB medium at 37°C, and samples were taken. There was a 12-fold increase in β-galactosidase activity with the long fusion in an hns mutant (Table 1). However, the activity of β-galactosidase with the short fusion was increased only twofold in the hns cells (Table 1). This result suggests that there was a strong (sixfold) increase in stability and a modest (twofold) increase in synthesis. Consistent with a twofold increase in RpoS synthesis in the hns mutant, the same twofold increase was seen in the long RpoS750::lacZ fusion in an rssB hns double mutant compared to an rssB mutant (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Accumulation of RpoS-lacZ in hns mutants

| Strain or mutation(s) | β-Galactosidase activity

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Long fusiona | Short fusionb | |

| Wild type | 0.16 ± 0.07 | 0.89 ± 0.11 |

| hns | 1.91 ± 0.11 | 1.58 ± 0.025 |

| rssB | 1.02 ± 0.10 | ND |

| hns rssB | 1.93 ± 0.01 | ND |

Cells were grown in LB medium at 37°C, and ß-galactosidase was assayed as previously described (24). Units are arbitrary specific activity machine units about 25-fold lower than Miller units. This fusion protein is subject to RssB-dependent degradation. The strains used were strains SG30013 (wild-type, RpoS750::LacZ), SG30059 (hns::kan), SG30018 (rssB::tet), and YN534 (hns::kan rssB::tet), all derivatives of SG30013 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Cells were grown as described in footnote a. The fusion protein is stable. The strains used were strains EM1246 (wild-type, RpoS477::LacZ) and YN714 (hns::kan), a derivative of EM1246. ND, not determined.

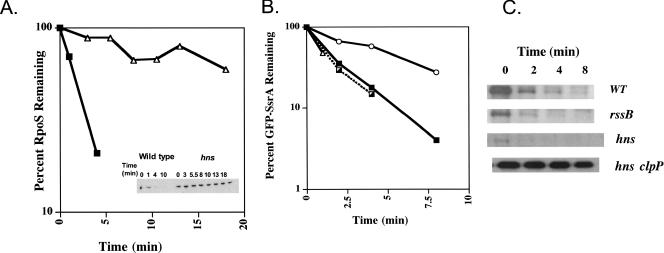

hns effects on RpoS turnover are independent of synthesis signals.

It has been suggested that changes in RpoS levels may be sufficient to lead to titration of RssB under some growth conditions (18). While we saw only a twofold effect of hns mutants on RpoS synthesis, we further checked for the effect of hns mutants on RpoS turnover in the absence of the normal synthesis signals. RpoS was cloned under pBAD transcriptional control, deleting the normal signals for transcriptional and translational regulation. Two other control proteins, green fluorescent protein (GFP)-SsrA, which is also a substrate of ClpXP (10, 20) but does not require RssB, and LacZ, which is not a substrate of ClpXP, were also cloned under pBAD control. Isogenic hns+ and hns strains carrying a chromosomal mutation inactivating rpoS and carrying plasmid pBAD-RpoS or pBAD-LacZ were grown in LB medium at 37°C in the absence of inducer. Under these conditions, the amount of the RpoS was slightly less than the amount from a chromosomal single-copy gene (data not shown). The half -life of the proteins expressed from pBAD was determined by a spectinomycin chase experiment. Cells were grown to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.4 to 0.45, spectinomycin (final concentration, 100 μg/ml) was added to the cultures to inhibit further protein synthesis, and samples were removed and analyzed by Western blotting. Consistent with the accumulation of the RpoS750::LacZ fusion protein (Table 1), the RpoS half-life was increased 10-fold (to 20 min or more) in an hns mutant compared to the 2-min half-life in a wild-type strain (Fig. 1A), which is consistent with previous reports (1, 22). As expected, LacZ was stable with a half-life of more than 20 min in both wild-type and hns strains; the amount of LacZ at zero time was the same in both strains, ruling out an effect of hns on expression from the pBAD promoter (data not shown). To assess the effect of the hns mutation on degradation of an RssB-independent ClpXP substrate, the stability of GFP-SsrA was examined. The SsrA tag renders proteins, including GFP, sensitive to ClpXP-dependent degradation (6, 7). pBAD-GFP-SsrA was induced for 30 min, followed by treatment with spectinomycin as described above for pBAD-RpoS. The GFP-SsrA protein was unstable, with a 1.5-min half-life in a wild-type strain (Fig. 1B and C), which is consistent with data from other labs (6). GFP-SsrA was at least as unstable in an hns mutant, with a much lower initial level of accumulation (Fig. 1C). A clpP mutant stabilized the protein in the hns mutant strain, as expected (Fig. 1B and C). We concluded that hns mutants do not lead to stabilization of all ClpXP substrates and therefore appear to be specific to the RssB-dependent pathway.

FIG. 1.

RpoS is stabilized specifically in an hns mutant. Cells were grown in LB broth at 37°C to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.3 to 0.5; a sample was removed, and 100 μg/ml spectinomycin was added to the remaining culture. Samples were removed at different times, precipitated with 5% trichloroacetic acid in cold conditions, and analyzed by Western blotting. For quantitation, estimates were extrapolated from a series of sample dilutions that showed a linear response on film after scanning with an Eagle Eye II scanner (24), using 3 min as zero time on the graphs (there was a modest increase in signal between the addition of spectinomycin and 3 min). (A) The only source of RpoS is from the uninduced pBAD plasmid, and the levels of RpoS are comparable to those from the chromosome. Symbols: ▪, wild-type strain YN559 (rpoS::tet/pBAD-RpoS); ▵, hns strain YN561 (rpoS::tet hns::kan/pBAD-RpoS). (B and C) Symbols: ▪, wild-type strain YN783/pBAD-GFP-ssrA; ▵, hns strain YN788 (hns/pBAD-GFP-ssrA); ┌, rssB strain YN791 (rssB/pBAD-GFP-ssrA); ○, hns clpP strain YN792 (hns clpP/pBAD-GFP-ssrA). WT, wild type.

hns mutant does not decrease RssB amounts or act via phosphorylation levels.

RpoS degradation depends on the response regulator RssB, in addition to ATP-dependent ClpXP in vivo and in vitro (11, 23). The active (phosphorylated) form of RssB is necessary for its maximal activity in RpoS degradation in rapidly growing cells, although the ability of RssB to be phosphorylated is not required for signal transduction (i.e., stabilization in response to carbon starvation [16]). Given that an hns mutant did not stabilize another RssB-independent ClpXP substrate (Fig. 1B), the effect on RpoS might have been due to a decrease in either RssB level or RssB activity. We examined the activity of the rssB promoter, using an rssA-rssB′::lacZ transcriptional fusion (19). Contrary to the prediction of less rssB expression, we found a two- to threefold increase in β-galactosidase activity in the hns cells compared to the wild-type cells (data not shown). Furthermore, an hns double mutant with either sprE19::cam or rssA2::cam, alleles of rssB that modestly increase the expression of RssB and remove it from control by its normal promoter (13, 17), still exhibited high levels of RpoS accumulation, ruling out a cis effect of the hns mutant not measured by the transcriptional fusion (data not shown). In the rssA2::cam strain, RssB levels were shown not to change when hns was mutated (data not shown). These results are consistent with previously reported results of experiments directly measuring RssB levels in an hns mutant by Western blotting (11). Therefore, lower RssB levels cannot account for the stabilization of RpoS in an hns strain.

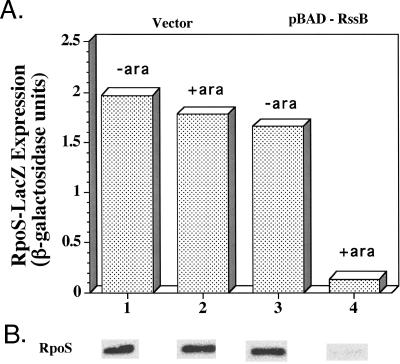

Using a plasmid with rssB under pBAD control, we measured RpoS and RpoS750::LacZ expression when RssB was overproduced at a high level in the hns mutant strain. Overnight cultures of hns mutant strains carrying either a vector or the pBAD24-RssB plasmid were diluted into LB media with or without arabinose at 37°C. Samples were taken at mid-exponential phase, amounts of RpoS were measured by Western blotting, and RpoS750::LacZ expression was determined by a β-galactosidase assay. The amounts of both RpoS and RpoS750::LacZ were dramatically (10-fold) reduced when RssB was induced in the hns mutant (Fig. 2, lane 4). This result, coupled with the rapid degradation of GFP-SsrA in an hns mutant, rules out an effect of hns mutants on ClpXP activity and suggests that RssB activity was inhibited but not abolished in the hns mutant; the inhibition could be overcome by excess RssB.

FIG. 2.

Suppression of hns by RssB overproduction. (A) Strains containing an RpoS::LacZ reporter that measures transcription, translation, and protein degradation were grown in LB medium at 37°C with and without 0.02% arabinose (ara); samples were taken at an optical density at 600 nm of 0.4, and β-galactosidase activity was assayed with a SpectraMax plate reader, as previously described (24). The strains used were vector strain YN513 (hns::kan/pBAD24) and pBAD-RssB strain YN514 (hns::kan/pBAD24-RssB). (B) Samples were removed at the same time as described above for panel for A, and RpoS levels were determined by Western blotting as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

One major mode of regulating RssB activity is via phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Possibly the hns mutant, by changing the level of expression of a kinase or phosphatase, could affect RssB activity. Therefore, we asked whether phosphorylation was essential for the effect of the hns mutant. Asp58 of RssB is the site of phosphorylation (2), but mutant derivatives of RssB carrying substitutions at this position still retain some activity in vivo (15, 16).

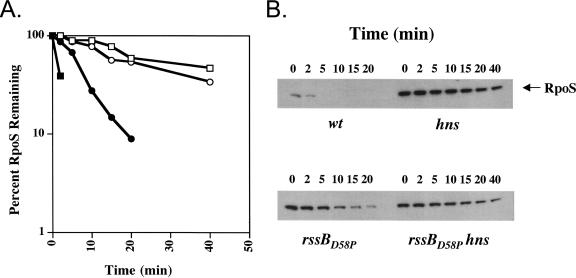

We constructed a chromosomal nonphosphorylatable rssB mutation, replacing the wild-type allele of rssB with rssBD58P by recombineering (4); this allele has been shown to have some activity when it is overexpressed, but it cannot be phosphorylated (11). RpoS stability was determined by Western blotting after a spectinomycin chase (Fig. 3). Consistent with our previous results (Fig. 1), in an rssB+ host, RpoS was 10-fold more stable in an hns mutant than in an hns+ strain (Fig. 3A and B). Also, as previously found for an rssBD58A allele (16), RpoS turnover was modestly (2.5-fold) slower in the rssBD58P strain than in an rssB+ strain (Fig. 3). We noted that the effect of changing the Asp58 residue in the chromosome (16; this study) is apparently less dramatic in terms of RpoS stability than it is in experiments in which the mutant form of RssB is expressed from a plasmid, even when expression was at levels believed to be similar to those from the chromosome (11, 14). We do not currently have an explanation for this difference.

FIG. 3.

RpoS turnover in rssBD58P strains. Strains were grown in LB medium at 37°C, and RpoS turnover was analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Symbols: ▪, wild-type strain YN879 (rpoS::tet/pBAD24-RpoS); □, hns strain YN881(rpoS::tet hns::kan/pBAD24-RpoS); •, rssBD58P strain YN872 (rpoS::tet rssBD58P/pBAD24-RpoS); ○, rssBD58P hns strain YN873 (rpoS::tet hns::kan rssBD58P/pBAD24-RpoS).

In strains carrying the chromosomal rssBD58P allele, an hns mutation still increased the RpoS half-life threefold, resulting in turnover that was essentially identical to that for the hns mutant in an rssB+ host (Fig. 3). This result is inconsistent with the hns mutant acting primarily to change the phosphorylation state of RssB. The phosphorylation-independent action of an hns mutant confirms and extends the result previously reported for the effect of carbon starvation and phosphate starvation, which also lead to RpoS stabilization independent of phosphorylation (3, 16). ArcB, a histidine kinase, has recently been implicated in phosphorylation of RssB in vivo and in vitro; an arcB mutant was found to slow RpoS turnover in a phosphorylation-dependent manner (14). Consistent with the ability of an hns mutant to stabilize RpoS in a strain with a nonphosphorylatable rssB allele, we also found that an hns mutant also increased the half-life of RpoS in the arcB mutant (data not shown).

Conclusions.

The results presented here show that an hns mutant had a profound effect on RpoS stability, independent of any effect of hns on synthesis of RpoS or RssB and without leading to stabilization of other ClpXP substrates. Thus, the hns effect on RpoS stability is specific to the RssB-dependent degradation pathway. Surprisingly, this effect is also independent of RssB phosphorylation, but it can be overcome by high levels of RssB. Our results suggest that in the hns mutant, RssB is present but inactive.

One explanation for these results postulates a protein(s) that is capable of protecting RpoS from degradation, possibly by blocking RssB access to RpoS, since overproduction of RssB can bypass the defect (Fig. 2). If the protein is synthesized only in hns cells and is not abundant in hns+ cells under the growth conditions used here, the effect of hns mutants would be explained. What is the role of the proposed H-NS repression of a gene or genes that, in turn, regulate RpoS stability? We predict that, as for other H-NS-repressed genes, H-NS repression is overcome by binding of a positive regulator under specific environmental conditions. This would allow specific stabilization of RpoS under whatever stress condition leads to activation of the specific RssB inhibitor. If in fact H-NS regulation of this putative gene is negative, this supports the idea that rapid degradation of RpoS may be the default situation, and stabilization under specific conditions underlies regulated proteolysis.

Recent results in our laboratory provide a further basis for understanding this phenomenon. A genetic screen led to the identification of a small protein, IraP, that stabilizes RpoS when it is overproduced, apparently by binding to RssB. It too acts even on the nonphosphorylatable form of RssB (3). IraP is not solely responsible for the stabilization of RpoS in hns mutants, however, since mutation of iraP in an hns mutant does not restore rapid RpoS degradation (A. Bougdour, unpublished observations). We propose that one or more functional homologs of IraP are responsible for stabilization of RpoS in the hns mutant. One candidate for such a gene, yhhP, was identified by Yamashino and coworkers as contributing to the stabilization of RpoS in hns strains (21), but this gene has recently been shown to encode a tRNA modification enzyme, suggesting a thus-far-unexplained level of complexity in regulation of RpoS degradation (9).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Silhavy for providing the rssA-rssB′::lacZ fusion and N. Majdalani for providing the NM300 strain. We are grateful to E. Massé for making the RpoS-lacZ short fusion for this study. We thank members of the Gottesman laboratory, Sue Wickner, and Michael Maurizi for useful discussions and comments on the manuscript.

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH National Cancer Institute Center for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barth, M., C. Marschall, A. Muffler, D. Fischer, and R. Hengge-Aronis. 1995. Role for the histone-like protein H-NS in growth phase-dependent and osmotic regulation of σS and many σS-dependent genes in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 177:3455-3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouché, S., E. Klauck, D. Fischer, M. Lucassen, K. Jung, and R. Hengge-Aronis. 1998. Regulation of RssB-dependent proteolysis in Escherichia coli: a role for acetyl phosphate in a response regulator-controlled process. Mol. Microbiol. 27:787-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bougdour, A., S. Wickner, and S. Gottesman. 2006. Modulating RssB activity: IraP, a novel regulator of σS stability in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 20:884-897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Court, D. L., S. Swaminathan, D. Yu, H. Wilson, T. Baker, M. Bubunenko, J. Sawitzke, and S. K. Sharan. 2003. Mini-lambda: a tractable system for chromosome and BAC engineering. Gene 315:63-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dorman, C. J. 2004. H-NS: A universal regulator for a dynamic genome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:391-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farrell, C. M., A. D. Grossman, and R. T. Sauer. 2005. Cytoplasmic degradation of ssrA-tagged proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 57:1750-1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gottesman, S., E. Roche, Y.-N. Zhou, and R. T. Sauer. 1998. The ClpXP and ClpAP proteases degrade proteins with carboxy-terminal peptide tails added by the SsrA-tagging system. Genes Dev. 12:1338-1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hengge-Aronis, R. 2002. Signal transduction and regulatory mechanisms involved in control of the σS (RpoS) subunit of RNA polymerase. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66:373-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikeuchi, Y., N. Shigi, J. Kato, A. Nishimura, and T. Suzuki. 2006. Mechanistic insights into sulfur relay by multiple sulfur mediators involved in thiouridine biosynthesis at tRNA wobble positions. Mol. Cell 21:97-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim, Y. I., R. E. Burton, B. M. Burton, R. T. Sauer, and T. A. Baker. 2000. Dynamics of substrate denaturation and translocation by the ClpXP degradation machine. Mol. Cell 5:639-648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klauck, E., M. Lingnau, and R. Hengge-Aronis. 2001. Role of the response regulator RssB in σS recognition and initiation of σS proteolysis in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 40:1381-1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Majdalani, N., C. K. Vanderpool, and S. Gottesman. 2005. Bacterial small RNA regulators. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 40:93-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mandel, M. J., and T. J. Silhavy. 2005. Starvation for different nutrients in Escherichia coli results in differential modulation of RpoS levels and stability. J. Bacteriol. 187:434-442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mika, F., and R. Hengge. 2005. A two-component phosphotransfer network involving ArcB, ArcA, and RssB coordinates synthesis and proteolysis of σS (RpoS) in E. coli. Genes Dev. 19:2770-2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moreno, M., J. P. Audia, S. M. Bearson, C. Webb, and J. W. Foster. 2000. Regulation of sigma S degradation in Salmonella enterica var. typhimurium: in vivo interactions between sigma S, the response regulator MviA (RssB) and ClpX. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2:245-254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peterson, C. N., N. Ruiz, and T. J. Silhavy. 2004. RpoS proteolysis is regulated by a mechanism that does not require the SprE (RssB) response regulator phosphorylation site. J. Bacteriol. 186:7403-7410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pratt, L. A., and T. J. Silhavy. 1996. The response regulator SprE controls the stability of RpoS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:2488-2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pruteanu, M., and R. Hengge-Aronis. 2002. The cellular level of the recognition factor RssB is rate-limiting for σS proteolysis: implications for RssB regulation and signal transduction in σS turnover in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 45:1701-1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruiz, N., C. N. Peterson, and T. J. Silhavy. 2001. RpoS-dependent transcriptional control of sprE: regulatory feedback loop. J. Bacteriol. 183:5974-5981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh, S. K., R. Grimaud, J. R. Hoskins, S. Wickner, and M. R. Maurizi. 2000. Unfolding and internalization of proteins by the ATP-dependent proteases ClpXP and ClpAP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:8898-8903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamashino, T., M. Isomura, C. Ueguchi, and T. Mizuno. 1998. The yhhP gene encoding a small ubiquitous protein is fundamental for normal cell growth of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 180:2257-2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamashino, T., C. Ueguchi, and T. Mizuno. 1995. Quantitative control of the stationary phase-specific sigma factor, σS, in Escherichia coli: involvement of the nucleoid protein H-NS. EMBO J. 14:594-602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou, Y., S. Gottesman, J. R. Hoskins, M. R. Maurizi, and S. Wickner. 2001. The RssB response regulator directly targets σS for degradation by ClpXP. Genes Dev. 15:627-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou, Y.-N., and S. Gottesman. 1998. Regulation of proteolysis of the stationary-phase sigma factor RpoS. J. Bacteriol. 180:1154-1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.