Abstract

The CspA family of cold shock genes in Escherichia coli K-12 includes nine paralogs, cspA to cspI. Some of them have been implicated in cold stress adaptation. Screening for mutations among common laboratory E. coli strains showed a high degree of genetic diversity in cspC but not in cspA and cspE. This diversity in cspC was due to a wide spectrum of variations including insertions of IS elements, deletion, and point mutation. Northern analysis of these mutants showed loss of cspC expression in all but one case. Further analysis of the loss-of-function cspC mutants showed that they have a fitness advantage in broth culture after 24 h over their isogenic wild-type derivatives. Conversely, introduction of mutated cspC alleles conferred a competitive fitness advantage to AB1157, a commonly used laboratory strain. This provides the evidence that loss of cspC expression is both necessary and sufficient to confer a gain of fitness as seen in broth culture over 24 h. Together, these results ascribe a novel role in cellular growth at 37°C for CspC, a member of the cold shock domain-containing protein family.

The evolution of a microbial population in a competitive environment is shaped by natural selection. The understanding of such processes has been aided by identification and characterization of mutants that show altered fitness over the parent. Investigations of mutations that decrease fitness have identified genes that are under selective pressure to be maintained (8, 29, 31, 35). Similarly, genes that confer selective advantage when mutated have been identified by analyzing mutant strains that exhibit a gain of fitness over its parent (4, 22, 37). This advantage due to gain of fitness under specific conditions can lead to the fixation of mutation by replacement of the parental population (4, 22). A classic example is RpoS, a global regulator involved in adaptation to various stresses in Escherichia coli, which is frequently lost under nutrient-limiting conditions (22). Mutations in rpoS are commonly encountered in natural and laboratory populations of E. coli (12, 13). Similarly, an E. coli strain with a mutation in the leucine response protein (lrp) has been shown to have a growth advantage enabling it to outgrow the parent upon prolonged stationary-phase incubation (37).

CspC, previously described as a regulator of rpoS (24), is a member of the CspA cold shock protein (CSP) family consisting of nine paralogs (CspA to CspI) in E. coli. Of the nine CSPs, only CspA, CspB, CspE, CspG, and CspI are cold inducible to various magnitudes (9, 10). Although they are part of the cold shock response, a simultaneous deletion of cspA, cspB, cspG, and cspE is required to make the cells cold sensitive (32). CspD appears to play a role in nutrient stress response (34). Unlike other CSPs, CspC and CspE are expressed even at 37°C and have been implicated in chromosome condensation and cell division (11, 33). Though CspC has also been shown to be involved in transcription antitermination (2) and regulation of expression of RpoS and UspA (24), its exact role in cellular physiology is not understood. In this article, we report the occurrence of a high degree of genetic variations in the cspC locus among our laboratory strains. Physiological characterization of these mutants showed that loss of cspC confers a net fitness advantage in broth culture after 24 h compared to that of wild-type cspC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

All bacterial strains used were derivatives of E. coli K-12 and are described in Table 1. The bacterial cultures were grown at 37°C in Luria broth (LB) and supplemented with tetracycline (12.5 μg ml−1) where required.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| E. coli K-12 strain | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| AB1157 | F−thi-1 thr-1 leuB6 Δ(gpt-proA)62 his4 argE3 ara-14 lacY1 galK2 xyl-5 mtl-1 rpsL31kdg K-51 tsx-33 supE44 wild-type cspC | E. coli Genetic Stock Centre |

| MG1655 | F− λ−rph-I; wild-type cspC | E. coli Genetic Stock Centre |

| MD1157 | AB1157 gicA1 gicB1 gicC1 ΔcspCa | 17 |

| MD11571 | F− AB1157; (G18R) substitution in CspCa | Lab collection |

| MD2223 | HfrC relA1 tonA22 T2rcspC-IS150ab | Lab collection |

| W3110 | F− IN (rrnE-rrnD)1; wild-type cspC | 15 |

| MD15502 | AB1157 recD1009 cspC::IS5a | Lab collection |

| CAG18486 | MG1655, eda-51::Tn10 | 28 |

| DR1001 | As MD2223 but transduced with eda-51::Tn10 and wild-type cspC | This study |

| DR1003 | As MD2223 but transduced with eda-51::Tn10; retains cspC-IS150 | This study |

| DR1012 | As MD11571 but transduced with eda-51::Tn10 and wild-type cspC | This study |

| DR1017 | As MD1157 but transduced with eda-51::Tn10 and wild-type cspC | This study |

| DR1016 | As MD1157 but transduced with eda-51::Tn10, retains ΔcspC | This study |

| DR1031 | As AB1157 but having cspC-IS150 allele from MD2223 | This study |

| DR1033 | As AB1157 but having ΔcspC allele from MD1157 | This study |

Alleles characterized in this study.

IS150 insertion 61 bp downstream of cspC ORF.

Construction of strains.

P1-mediated transduction as described by Miller (18) was used to construct isogenic pairs having wild-type cspC or its mutated allele. P1vir grown on CAG18486 was used to construct DR1001, DR1012, and DR1017, the wild-type cspC derivatives of MD2223, MD11571, and MD1157, respectively. Similarly, P1vir grown on transductants DR1003 (Tetr MD2223) and DR1016 (Tetr MD1157) were used to transfer the mutated cspC alleles to AB1157, resulting in construction of DR1031 and DR1033, respectively. The status of cspC in the transductants was checked by PCR.

Genomic DNA preparation.

The E. coli cultures were grown overnight in LB at 37°C with aeration. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation, and the genomic DNA was prepared using an Ultrapure genomic DNA prep kit (Bangalore Genei, Bangalore, India) as per the manufacturer's instructions.

Southern blot analysis.

Southern blot analysis was carried out essentially by the method of Sambrook et al. (25). Briefly the method is as follows. Genomic DNA (5 μg) digested with restriction endonuclease (NEB) was fractionated on agarose gel by electrophoresis, transferred to Hybond N+ membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Inc., Piscataway, NJ), and cross-linked by UV irradiation. The membrane was prehybridized for 2 h at 68°C with high-sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) buffer (sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, 250 mM; sodium chloride, 250 mM; EDTA, 1 mM; SDS, 7%). The probe, a 1.8-kb fragment, obtained by PCR amplification using DSR41 and DSR42 primers (Fig. 1), was labeled with [α-32P]dATP using a Megaprime labeling kit (Amersham) and hybridized at 68°C in the above-mentioned buffer. After overnight incubation, the membrane was serially washed twice at each step with 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) plus 0.1% SDS for 5 min at room temperature, 1× SSC plus 0.1% SDS for 15 min at 65°C, and 0.1× SSC plus 0.1% SDS for 10 min at 65°C. An autoradiogram was developed on a storage phosphor (Phosphorimager, SF-425; Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyville, CA).

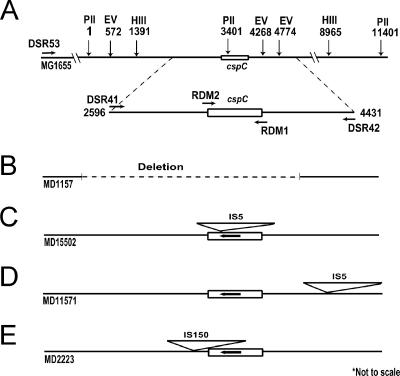

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the physical structure of the cspC gene from wild-type and mutant strains of E. coli and the relative positions of different primers on E. coli genome. The numbers indicating the distance between the restriction sites are relative to the first PvuII site. PII, PvuII; EV, EcoRV; HIII, HindIII. (A) MG1655, W3110, and AB1157 show the wild-type allele. (B) Deletion spanning cspC in MD1157. (C) IS5 insertion in the ORF in MD15502. (D) IS5 insertion 600 bp upstream and G-to-C transversion of the 52nd nucleotide of the ORF in MD11571. (E) IS150 insertion 61 bp downstream of the cspC ORF in MD2223.

Northern blot analysis.

Total RNA from cells grown to log phase at 37°C was isolated by the hot phenol method (1). RNA (10 μg) was separated in a 1.5% formaldehyde-agarose gel and blotted to Hybond N+ membrane by capillary transfer with 20× SSC. A 235-bp PCR product generated using primers RDM1 and RDM2, corresponding to the cspC open reading frame (ORF) (Fig. 1), was labeled as described above and used as a probe. The blots were prehybridized for 1.5 h at 68°C in hybridization buffer (7% SDS, 5× SSC, 2% casein, 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, 0.1% [wt/vol] N-laurylsarcosine). After prehybridization, the buffer was replaced with fresh hybridization buffer containing cspC probe and incubated at 65°C overnight. Following hybridization, blots were washed twice at room temperature in 2× SSC for 15 min and twice at 68°C in 0.5× SSC for 15 min and in 0.1× SSC for 5 min. The autoradiogram was developed on a storage phosphor (described above).

PCR and sequencing.

The relative positions of the primers in the cspC region are described in Fig. 1. Primers RDM1(5′-GAATTTTTCATATGGCAAAGATTAAAGGTC-3′) and RDM2 (5′-ATCAGTGGATCCTATCAGATAGCTGTTACG-3′) were used to amplify the cspC ORF. DSR41 (5′-CCTTCCAGTTGTTCTGCATGAGGT-3′) and DSR42 (5′-GGTCGCCGAACGATAATCCTT-3′) were used to amplify an ∼1.8-kb fragment corresponding to cspC with flanking sequences. DSR53 (5′-CTACTGCCCTATACTCCATGGTTG-3′) and DSR42 were used to amplify an ∼6.5-kb fragment spanning cspC to characterize the size of deletion in MD1157. VRS1 (5′-CAGGCGAATTCTTGCTGACG-3′) and VRS2 (5′-GTCTGGAATTCACCGCTGGCG-3′) and VRS7 (5′-GGGGATCCAGACGCGTGAAGC-3′) and VRS8 (5′-GTGAATTCAACACAGAGCTGGAAT-3′) were used to amplify the cspE and cspA genes, respectively. PCR amplification was performed using the Expand high-fidelity PCR system (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The PCR product was treated with shrimp alkaline phosphatase and exonuclease I (USB Corp., Cleveland, Ohio) for 30 min at 37°C. The enzymes were inactivated by boiling at 80°C for 20 min. Sequencing was done with an ABI Prism 377-18 automated DNA sequencer using the Big Dye terminator kit (ABI, Foster City, CA).

Fitness assays and growth analysis.

Estimation of the relative fitness of two strains was done with an adaptation of an earlier described protocol (6). Isogenic strains carrying either wild-type or a mutated cspC allele were competed against each other. One of the competing pair carried a selective marker (tetracycline) that was found to be neutral under the conditions tested. The competing strains were individually grown in LB to saturation at 37°C. Equal volumes of each strain were diluted (1:1,000) into the same flask containing 5 ml of LB and allowed to compete for the same pool of nutrients at 37°C for 24 h. The density of the competing pair of cells at the start of the experiment and 24 h after competition was determined by plating appropriate dilutions on LB plates with or without tetracycline. Each competition assay was performed with fivefold replication. Growth of the strains during competition was monitored by plating appropriate dilutions at periodic intervals on LB plates with or without antibiotic.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

Sequence data have been submitted to the GenBank database under accession no. DQ445810, DQ445811, DQ445812, DQ445313, and DQ445814.

RESULTS

Variation in the cspC region.

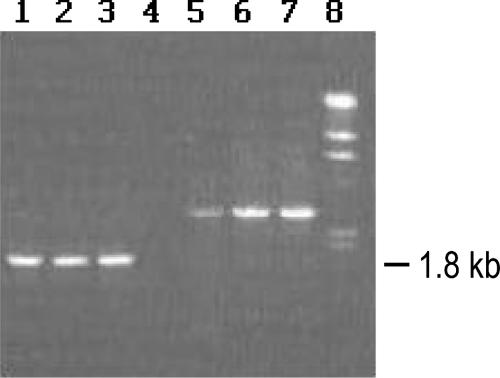

The cspC region from different E. coli strains was analyzed by PCR amplification using various primers as shown in Fig. 1. Primers DSR41 and DSR42 amplified an expected 1.8-kb product in AB1157, MG1655, and W3110, whereas the products obtained from MD2223, MD11571, and MD15502 were longer (Fig. 2). Amplification with ORF primers RDM1 and RDM2 yielded a product of the expected size (235 bp) in AB1157, MG1655, W3110, MD2223, and MD11571, whereas MD15502 yielded a 1.4-kb product (data not shown). These results suggested an insertion within the cspC ORF of MD15502 and insertions outside the ORF in MD2223 and MD11571. However, in MD1157 the PCR product was not obtained with either of these primer combinations, suggesting a genetic rearrangement involving cspC in this strain. These results indicate a high degree of genetic variation in the cspC region.

FIG. 2.

PCR amplification of cspC using primers DSR41 and DSR42 from different strains. Lane 1, AB1157; lane 2, MG1655; lane 3, W3110; lane 4, MD1157; lane 5, MD2223; lane 6, MD11571; lane 7, MD15502; lane 8, molecular size markers (λ DNA digest of HindIII).

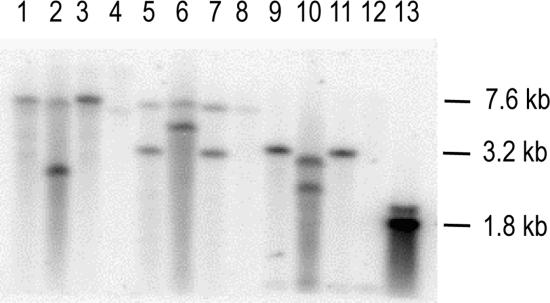

Southern hybridization analysis of the genomic DNA from these strains (Fig. 3) confirmed the insertions in MD15502, MD2223, and MD11571. The results also showed a deletion spanning cspC in MD1157. To characterize the variations in the cspC region, the ORF along with flanking region was PCR amplified using primers DSR41 and DSR42 from MD15502, MD2223, and MD11571 and sequenced. Sequence analysis showed that MD15502 has an IS5 insertion within cspC ORF, 44 bp downstream of the translation start site (GenBank accession no. DQ445813 and DQ445814). In MD11571, an IS5 insertion 600 bp upstream of the translation start site of the cspC ORF was detected (accession no. DQ445811). In addition, a G-to-C transversion of the 52nd nucleotide from the translation start site leading to a change in the 18th amino acid from GGC (Gly) in the wild type to CGC (Arg) in MD11571 was also observed (accession no. DQ445810). The IS5 insertion sites in MD15502 and MD11571 both conformed to the preferred consensus target sequence for IS5, YTAR (16). The cspC sequences of AB1157, MG1655, and W3110 were identical and matched the published wild-type sequence of MG1655.

FIG. 3.

Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of cspC region using a 1.8-kb probe from MG1655 spanning the cspC gene. Lanes 1, 5, and 9, MG1655 chromosomal DNA digested with HindIII, PvuII, and EcoRV, respectively; lanes 2, 6, and 10, MD2223 chromosomal DNA digested with HindIII, PvuII, and EcoRV, respectively; lanes 3, 7, and 11, AB1157 chromosomal DNA digested with HindIII, PvuII, and EcoRV, respectively; lanes 4, 8, and 12, MD1157 chromosomal DNA digested with HindIII, PvuII, and EcoRV, respectively; lane 13, cspC (PCR-amplified 1.8-kb DSR41-plus-DSR42 fragment).

An IS150 insertion 61 bp downstream of the cspC ORF was seen in MD2223 (accession no. DQ445812). Although the primer pairs RDM1 plus RDM2 and DSR41 plus DSR42 did not yield any PCR product in MD1157, an ∼100-bp PCR band was obtained with primers DSR42 and RDM2. Analysis of the sequence showed that this ∼100-bp band resulted from nonspecific binding of primer RDM2 close to the DSR42 site. Combining this serendipitous finding with the earlier result in which DSR41 failed to give a PCR product in combination with DSR42, we concluded that the deletion in MD1157 was to the left of DSR42, spanning the cspC gene and extending at least up to the DSR41 binding site (Fig. 1). The extent of deletion in MD1157 was further characterized by PCR using a series of primers binding at different locations downstream (to the left of DSR41) of the cspC ORF in combination with DSR42. One of the primer pairs tested (DSR42 plus DSR53) gave an amplification product. Comparison of the size of the PCR product obtained with expected size showed that the deletion was approximately 2 kb in size, including the cspC gene (data not shown). The results (summarized in Fig. 1) show that diverse genetic mechanisms contributed to the high degree of genetic variations seen in and around the cspC region.

Genetic changes in the cspC region affect its expression.

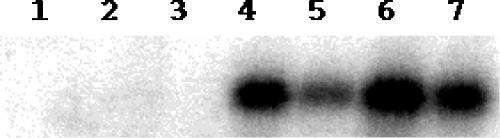

Whether the polymorphism in and around cspC affected its expression was investigated. Among the seven strains, cspC transcript was detected in MG1655, AB1157, MD11571, and W3110 (Fig. 4, lanes, 4, 5, 6, and 7) and not in MD15502, MD2223, and MD1157 (Fig. 4, lanes, 1, 2, and 3). The absence of cspC transcript in MD1157 that has a deletion in the cspC region was expected. However, lack of cspC transcript in MD2223 that has an IS150 insertion 61 bp downstream of cspC ORF was intriguing. The Northern blot analysis showed that a majority of these genetic changes in cspC region resulted in loss of cspC expression.

FIG. 4.

Northern blot analysis for cspC transcripts from different E. coli strains. Total RNA (5 μg) was used and probed with 235-bp DNA corresponding to cspC ORF. Lane 1, MD15502; lane 2, MD2223; lane 3, MD1157; lane 4, MG1655; lane 5, AB1157; lane 6, MD11571; lane 7, W3110.

Analysis of cspA and cspE regions.

CspA family proteins in E. coli are characterized by a high degree of sequence similarity among them. A comparison of CspC with other CspA family proteins shows 83% identity and 91% similarity between CspC and CspE and 69% identity and 79% similarity between CspC and CspA (33). It is therefore not surprising that CspA family proteins have similar activities and can also functionally complement each other (2, 11, 24, 30, 32). In view of the above findings, whether variations are limited to the cspC region alone or could also be found in cspA and cspE was investigated. cspE and cspA were amplified from the seven strains using primer pairs VRS1 plus VRS2 and VRS7 plus VRS8, respectively, and sequenced. Except for cspE from MD1157, which had a point mutation in the promoter region 121 bp upstream of the translation start site (26), no differences were observed (data not shown) in cspA and cspE sequences. The above results show that even though three genes are highly similar with overlapping functions, the genetic variations are found to accumulate only in and around cspC.

Selective advantage of loss of cspC expression.

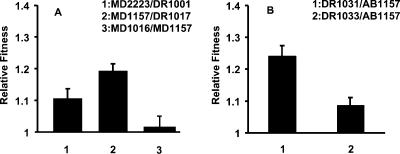

The involvement of multiple mechanisms in bringing about variations in the cspC region in diverse genetic backgrounds suggested a selection for loss of cspC expression. This was studied by investigating whether strains with mutation in cspC had any fitness advantage over their derivatives isogenic for wild-type cspC during competitive growth. The results of competition experiments using isogenic pairs MD2223 plus DR1001, MD1157 plus DR1017, and MD1157 and DR1016 are presented in Fig. 5A. The mutant cspC strains showed higher fitness in broth culture after 24 h relative to their wild-type cspC derivatives. The relative fitness of MD2223 was approximately 11% higher than that of its wild-type cspC derivative, while for MD1157, the fitness advantage was 19%. In other words, introduction of wild-type cspC decreased the competitive fitness of both MD2223 and MD1157. A competition between DR1016 (eda-51::Tn10, MD1157) and MD1157 showed that the presence of Tn10 in eda did not alter the relative fitness of MD1157 in broth culture. However, in the case of MD11571, replacement of the existing allele with wild-type cspC did not have any discernible effect on competitive fitness (data not shown). These results indicate that the fitness gain is associated with loss of cspC expression.

FIG. 5.

Relative fitness of strains as measured by competition assays. (A) Mutant strains MD2223 and MD1157 competed with wild-type cspC derivatives DR1001 and DR1017, respectively. MD1157 competed with eda::Tn10 derivative DR1016. (B) Mutant derivatives DR1031 and DR1033 competed with parental strain AB1157. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals based on fivefold replication for each competition assay.

In order to determine whether mutated cspC allele associated with a complete lack of expression imparted a significant fitness advantage in broth culture and whether it alone was sufficient to confer a gain of fitness, the cspC alleles from MD1157 and MD2223 were introduced into AB1157 by P1 transduction. The mutant cspC derivatives were competed against the parental AB1157, and the results are presented in Fig. 5B. Introduction of the mutated cspC allele from MD2223 resulted in ∼24% fitness gain, while the MD1157 allele imparted ∼9% gain. The cspC allele of MD15502 could not be tested in competition experiments, as attempts to replace it with the wild type or move this allele to the AB1157 background did not succeed. These results show that gain of fitness in broth culture after 24 h of competition associated with loss of cspC expression is irrespective of the genetic background.

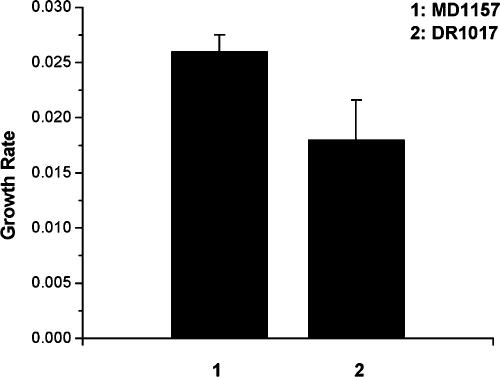

To understand the physiological basis of competitive advantage shown by the loss-of-function cspC alleles, the growth of isogenic pairs MD1157 plus DR1017 and MD2223 plus DR1001 was monitored during competitive growth. MD1157 exhibited a higher growth rate relative to its isogenic wild-type cspC derivative DR1017 (Fig. 6). Similar results were obtained for MD2223 and its derivative DR1001 (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Growth rate of cspC mutant (MD1157) and cspC wild-type (DR1017) strain during competition. Growth rate, R (the number of generations per hour), was calculated by the formula 3.3(log10 N − log10 N0)/t, where N is population density after time t, and N0 is the initial population density. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals based on threefold replication of the experiment.

DISCUSSION

Earlier work in our laboratory has focused on regulation of CspE and its interaction with CspA and CspC. Screening of the cspC locus by PCR in routinely used E. coli strains detected genetic variations in and around the cspC locus in four out of seven strains. Molecular characterization of these variations revealed that diverse independent genetic processes were responsible for these changes, which included insertion of IS5 and IS150 and deletion as well as point mutation (Fig. 1). The parallel and repeated evolution of a genotype has been considered as an evidence for adaptation by natural selection (4, 5, 21). The appearance of cspC mutations in many strains, which showed the repeatability of the phenomenon, indicated that this could be a result of evolutionary selection under some specific condition.

The CspA family of E. coli comprises nine homologous proteins, CspA to CspI, characterized by high sequence similarity and functional interchangeability (32). This redundancy could lead to accumulation of mutations in cspC, particularly if other csp genes have functions overlapping with cspC. This can potentially explain the diversity seen in cspC. However, our results show that cspC has a unique role in cellular physiology, and this apparently cannot be complemented by other csp genes. Since members of CspA family are characterized by their dispensable nature and functional redundancy (10, 30, 32), accumulation of mutations as a result of genetic drift should be expected in other CSPs as well. Among the CspA family members, CspC shares the highest degree of similarity and identity with CspE and CspA (33). In spite of such close similarity between these homologs, the variations were not detected either in cspE or cspA.

The ubiquity of variations in cspC gene region in strains having different genetic backgrounds coupled with the fact that different molecular processes were involved in the creation of these changes suggested that cspC was subjected to a strong selection pressure that may be linked to its physiological role. This notion was reinforced by the results of Northern analysis, which showed that mutations in three out of the four cases resulted in loss of cspC expression. A particularly striking case was that of MD2223, where insertion of IS150 downstream of the cspC ORF still knocked off the expression, while in the case of MD11571, which had a point mutation in the structural region and an IS5 insertion 600 bp upstream of cspC, the expression was not altered (Fig. 4).

Whether a genotype with mutated cspC has a fitness gain over the wild-type allele was analyzed among all the three strain backgrounds of MD2223, MD11571, and MD1157. Competition analysis (Fig. 5A) showed that replacement of cspC alleles in strains MD2223 and MD1157 with wild-type cspC decreased fitness of the cells in broth culture after 24 h. It was also observed that the replacement of cspC allele of MD11571 with a wild-type cspC did not alter the fitness of the strain. It is possible that MD11571 CspC in spite of the Gly→Arg (G18R) substitution retained its functional activity, and therefore its replacement with a wild-type allele showed no alteration in fitness in a competition experiment. In reverse crosses, introduction of two different cspC alleles from MD2223 (cspC-IS5) and MD1157 (ΔcspC) into AB1157 conferred significant (at 95% confidence interval) gains of fitness (24% and 9%, respectively) to AB1157 (Fig. 5B) in broth culture after 24 h of competition, strengthening our argument that the loss of cspC expression leads to gain of fitness. The difference in the relative fitness advantage observed shows its dependency on both the cspC allele and the strain background. These results conclusively show that the gain of fitness in E. coli strains was contingent upon loss of CspC alone.

Analysis of genetic changes that accompany alteration of population dynamics under controlled experimental evolution has identified loci with beneficial mutations (3, 4, 36, 37). Many of these changes are mediated by IS elements, and their role in genomic evolution is well documented (19, 20, 23, 27). Our results show that in the case of cspC, the majority of the changes involve either IS5 or IS150, though deletion is also observed. Cooper and colleagues (4) have documented a similar observation pertaining to the deletion of the rbs operon in evolving populations of E. coli apparently mediated by IS150. It has been shown that deletion of the rbs operon imparts a small fitness advantage (1.4% ± 0.4%), which is seen after a 6-day competition experiment. In contrast, our results (Fig. 5A) show that loss of cspC in two independent genetic backgrounds gives a substantial gain of fitness that is observed within 24 h of competition in broth culture.

Faure and colleagues (7) have shown the loss of genomic segments in long-term stab cultures of E. coli and the involvement of IS5 in generating these deletions. They have argued that mutations in genes that regulate rpoS and consequently the rpoS regulon may give a selective advantage as loss-of-function alleles of rpoS are well known to give a stationary-phase growth advantage. Furthermore, the concept of regulatory diversity caused by various RpoS protein levels and its effect on nutritional properties of various strains has been shown by King and colleagues (14). They have shown differing endogenous levels of RpoS in various strains, including E. coli K-12 lineages. Interestingly, CspC has been shown to positively regulate the expression of rpoS and uspA (24). Whether the fitness gain in liquid culture imparted by loss of cspC expression is mediated through rpoS needs to be investigated.

In conclusion, we have observed occurrence of mutations in cspC leading to its loss of expression. We have demonstrated that loss of cspC expression confers a significant growth advantage to E. coli K-12 cells. Occurrence of cspC mutations in independent strains shows that they have a selective advantage. This selective advantage is manifested irrespective of the molecular mechanism that leads to loss of cspC function. Though CspC is designated as a “cold shock protein,” this work describes a novel role for CspC in cellular growth at 37°C and adds cspC to the small list of genes in E. coli whose loss-of-function alleles confer a selective advantage to the cells.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank S. K. Mahajan for his encouragement during the initial part of these studies. We thank S. H. Mangoli for his help with fitness assays and A. V. S. S. N. Rao, S. Uppal, and M. Goswami for their help with the discussion. We thank A. Saini for help with manuscript preparation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aiba, H., S. Adhya, and B. deCrombrugghe. 1981. Evidence for two functional gal promoters in intact Escherichia coli cells. J. Biol. Chem. 256:11905-11910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bae, W., B. Xia, M. Inouye, and K. Severinov. 2000. Escherichia coli CspA-family RNA chaperones are transcription antiterminators. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:7784-7789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper, T. F., D. E. Rozen, and R. E. Lenski. 2003. Parallel changes in gene expression after 20,000 generations of evolution in E. coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:1072-1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper, V. S., D. Schneider, M. Blot, and R. E. Lenski. 2001. Mechanisms causing rapid and parallel losses of ribose catabolism in evolving populations of Escherichia coli B. J. Bacteriol. 183:2834-2841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cunningham, C. W., K. Jeng, J. Husti, M. Badgett, I. J. Molineux, D. M. Hillis, and J. J. Bull. 1997. Parallel molecular evolution of deletions and nonsense mutations in bacteriophage T7. Mol. Biol. Evol. 14:113-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elena, S. F., and R. E. Lenski. 1997. Test of synergistic interactions among deleterious mutations in bacteria. Nature 390:395-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faure, D., R. Fredrick, D. Włoch, P. Portier, M. Blot, and J. Adams. 2005. Genomic changes arising in long-term stab cultures of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 186:6437-6442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finkel, S. E., and R. Kolter. 2001. DNA as a nutrient: novel role for bacterial competence gene homologs. J. Bacteriol. 183:6288-6293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldstein, J., N. S. Pollitt, and M. Inouye. 1990. Major cold shock protein of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:283-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gualerzi, C. O., A. M. Giuliodori, and C. L. Pon. 2003. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional control of cold-shock genes. J. Mol. Biol. 331:527-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu, K. H., E. Liu, K. Dean, M. Gingras, W. DeGraff, and N. J. Trun. 1996. Overproduction of three genes leads to camphor resistance and chromosome condensation in Escherichia coli. Genetics 143:1521-1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ivanova, A. 1992. DNA base sequence variability in katF gene of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:5479-5480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jishage, M., and A. Ishihama. 1997. Variation in RNA polymerase sigma subunit composition within different stocks of Escherichia coli W3110. J. Bacteriol. 179:959-963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King, T., A. Ishihama, A. Kori, and T. Ferenci. 2004. A regulatory trade-off as a source of strain variation in the species Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 186:5614-5620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohara, Y., K. Akiyama, and K. Isono. 1987. The physical map of the whole E. coli chromosome: application of a new strategy for rapid analysis and sorting of a large genomic library. Cell 50:495-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahillon, J., and M. Chandler. 1998. Insertion sequences. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:725-774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mangoli, S. H., Y. Ramanathan, V. R. Sanzgiri, and S. K. Mahajan. 1997. Identification, mapping and characterization of two genes of Escherichia coli K-12 regulating growth and resistance to streptomycin in cold. J. Genet. 76:73-87. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller, J. H. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 19.Naas, T., M. Blot, W. M. Fitch, and W. Arber. 1994. Insertion sequence related genetic variation in resting Escherichia coli K-12. Genetics 136:721-730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naas, T., M. Blot, W. M. Fitch, and W. Arber. 1995. Dynamics of IS-related genetic rearrangements in resting Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Biol. Evol. 12:198-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakatsu, C. H., R. Korona, R. E. Lenski, F. J. de Bruijn, T. L. Marsh, and L. J. Forney. 1998. Parallel and divergent genotypic evolution in experimental populations of Ralstonia sp. J. Bacteriol. 180:4325-4331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Notley-McRobb, L., T. King, and T. Ferenci. 2002. rpoS mutations and loss of general stress resistance in Escherichia coli populations as a consequence of conflict between competing stress responses. J. Bacteriol. 184:806-811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papadopoulos, D., D. Schneider, J. Meier-Eiss, W. Arber, R. E. Lenski, and M. Blot. 1999. Genomic evolution during a 10,000-generation experiment with bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:3807-3812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phadtare, S., and M. Inouye. 2001. Role of CspC and CspE in regulation of expression of RpoS and UspA, the stress response proteins in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:1205-1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 26.Sanzgiri, V. R. 1997. Ph.D. thesis. University of Mumbai, Mumbai, India.

- 27.Schneider, D., E. Duperchy, E. Coursange, R. E. Lenski, and M. Blot. 2000. Long-term experimental evolution in Escherichia coli. IX. Characterization of IS-mediated mutations and rearrangements. Genetics 156:477-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singer, M., T. A. Baker, G. Schnitzler, S. M. Deischel, M. Goel, W. Dove, K. J. Jaacks, A. D. Grossman, J. W. Erickson, and C. A. Gross. 1989. A collection of strains containing genetically linked alternating antibiotic resistance elements for genetic mapping of Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Rev. 53:1-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Visick, J. E., H. Cai, and S. Clarke. 1998. The l-isoaspartyl protein repair methyl transferase enhances survival of aging Escherichia coli subjected to secondary environmental stresses. J. Bacteriol. 180:2623-2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weber, M. H. W., C. L. Beckering, and M. A. Marahiel. 2001. Complementation of cold shock proteins by translation initiation factor IF1 in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 183:7381-7386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiner, L., and P. Model. 1994. Role of an Escherichia coli stress-response operon in stationary phase survival. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:2191-2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xia, B., H. Ke, and M. Inouye. 2001. Acquirement of cold sensitivity by quadruple deletion of the cspA family and its suppression by PNPase S1 domain in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 40:179-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamanaka, K., T. Mitani, T. Ogura, H. Niki, and S. Hiraga. 1994. Cloning, sequencing, and characterization of multicopy suppressors of a mukB mutation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 13:301-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamanaka, K., and M. Inouye. 1997. Growth-phase-dependent expression of cspD, encoding a member of the CspA family in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179:5126-5130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yeiser, B., E. D. Pepper, M. F. Goodman, and S. E. Finkel. 2002. SOS-induced DNA polymerases enhance long-term survival and evolutionary fitness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:8737-8741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zambrano, M. M., and R. Kolter. 1996. GASPing for life in stationary phase. Cell 86:181-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zinser, E. R., and R. Kolter. 2000. Prolonged stationary-phase incubation selects for lrp mutations in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 182:4361-4365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]