Abstract

Goals of work

Prostate cancer, the most common life-threatening cancer among American men, increases risk of psychosocial distress and negatively impacts quality of life for both patients and their spouses. To date, most studies have examined the relationship between patient coping and distress; however, it is also likely that what the spouse does to cope, and ultimately how the spouse adjusts, will affect the patient’s adjustment and quality of life. The present study examined the relationships of spouse problem-solving coping, distress levels and patient distress in the context of prostate cancer. The following mediational model was tested: Spouses’ problem-solving coping will be significantly inversely related to patients’ levels of distress, but this relationship will be mediated by spouses’ distress levels.

Patients and methods

One hundred seventy-one patients with prostate cancer and their spousal caregivers were assessed for mood; spouses were assessed for problem-solving coping skills. Structural equation modeling was used to test model fit.

Main results

The model tested was a good fit to the data. Dysfunctional spousal problem-solving was a significant predictor of spouse distress level but constructive problem-solving was not. Spouse distress was significantly related to patient distress. Spouse dysfunctional problem-solving predicted patient distress, but this relationship was mediated by spouse distress. The same mediational relationship did not hold true for constructive problem-solving.

Conclusions

Spouse distress mediates the relationship between spouse dysfunctional coping and patient distress. Problem-solving interventions and supportive care for spouses of men with prostate cancer may impact not only spouses but the patients as well.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Caregivers, Spouses, Problem-solving, Quality of life

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer afflicting men in the United States, with an estimated 230,110 new cases diagnosed each year. It is also the second leading cause of cancer death, killing 29,900 men every year [2]. In addition to mortality, the diagnosis of prostate cancer and the side effects of its treatment can negatively impact patients’ quality of life and well-being [13, 18, 28].

Research has shown that prostate cancer is an experience that affects both the patient and his spouse. Couples coping with prostate cancer have reported feeling unprepared to cope with treatment decisions and treatment-related effects [21, 30]. Kornblith et al. found that spouses report high psychosocial distress that is related to the patients’ treatment side effects [26]. Several studies have found strong correlations between the psychosocial adjustment of cancer patients and their spouses, emphasizing the highly interdependent relationship between patients and their spouses throughout the cancer experience [11, 25, 26, 29].

A recent study by Banthia et al. showed that the relationship between prostate cancer patients’ maladaptive coping strategies and patient distress was moderated by good dyadic adjustment, such that patients who engaged in maladaptive coping but reported positive marital adjustment suffered less individual distress. Interestingly, the same relationship was not shown for the spouses [4]. These results are consistent with the notion that the female partner, through the relationship, may be playing a particularly important role in helping the patient to cope better. While it is established that patient and their spouse are both affected by the cancer experience, the mechanisms by which the couple’s distress are related are less well understood. Baider et al. found that the cancer patients were less distressed if they perceived less stress from their spouses and a good sense of family cohesion [3]. In another study, spouses were found to be more likely to focus on problem-solving while the patients reported using more emotion-focused coping, such as seeking support [20]. Hence, the literature suggests that the spouse’s distress may be more related to her coping skills while the patient’s distress is more related to his perceptions of support and cohesion.

Studies have documented relationships between problem-solving coping skills and psychological stress, depression, anxiety, coping, positive affectivity, negative affectivity, optimism, pessimism, and knowledge acquisition [12, 14, 16]. Cancer studies suggest the patient’s problem-solving is related to his/her own adjustment [1, 8]. Allen et al. found that women with breast cancer who received a 12-week problem-solving intervention reported lower unmet needs and better mental health at the conclusion of the intervention compared to the control group [1]. A recent study by Nezu et al. showed that adult cancer patients with elevated distress levels significantly improved after a ten-session problem-solving intervention compared with a waitlist control group [31].

Problem-solving interventions have also been shown to help improve quality of life for cancer patients’ family members, including spouses. A recent study by Sahler et al. demonstrated that mothers of children with cancer had enhanced problem-solving skills and decreased negative affect after an 8-week problem-solving intervention [32]. Bucher et al. offered a 90-minute problem-solving intervention to advanced cancer patients and their families and showed that both reported feeling more informed about community resources and scored higher in problem-solving ability [8]. In a study specifically focusing on spouses, Blanchard, Toseland, and McCallion found that distressed spousal caregivers of prostate cancer patients who underwent a problem-solving intervention experienced better physical, role, and social functioning, as well as better ability to cope, than those in the control group. Those in the intervention group reported improvement in their perceptions of their ability to cope with pressing problems while those in the control group reported unchanged levels. Similar results were found in another randomized trial by the same group of researchers in which spouses of patients with different cancers who were in the problem-solving intervention group were significantly less depressed after the intervention than were those in the control group [7]. In addition, a qualitative study by Malinski et al. described how couples used problem definition and cognitive reappraisal techniques to gather information about the disease, make informed treatment decisions, and regain a sense of control in their life. Couples reported less distress after using these problem-solving techniques [29].

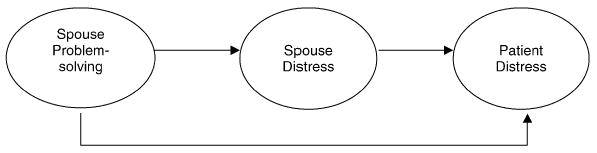

In sum, the literature suggests that, in prostate cancer: (1) patient and spouse distress is closely related, and (2) spouses’ problem-solving skills are predictors of their own adjustment and quality-of-life outcomes. In the current study, we examined a conceptual model that investigated whether spousal problem-solving may indirectly impact patient distress through its influence on spouse distress (Fig. 1). Specifically, we sought to answer the following questions: (1) Are prostate cancer patients’ distress levels related to those of their spouses? (2) Is spouse problem-solving related to spouse distress? and (3) Does spouse problem-solving predict patient distress, and is this relationship mediated by spouse distress?

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model

Patients and methods

Sample

One hundred seventy-one men diagnosed with prostate cancer and their spouses were recruited to a randomized clinical trial to assess the value of a problem-solving therapy program for spouses/partners of men with prostate cancer. Patients and their spouses were eligible to participate if: (1) the patient had been diagnosed with prostate cancer within 18 months of entry into the study, (2) the patient and spouse/significant other were living together, (3) they lived in San Diego County or close proximity, and (4) they both had basic English language proficiency. Spouse and patient demographic data can be found in Table 1; these data include age, ethnicity, highest level of education completed, and combined annual income, as well as patient and relevant medical information such as stage of cancer and months since diagnosis. Date of diagnosis and stage of cancer self-reported medical information were verified by patients’ providers.

Table 1.

Demographics. SD standard deviation

| Variable | Patient (male) | Spouse (female) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age: mean/range | 65.45 (SD=9.96)/41–89 years | 61.32 (SD=10.64)/32–86 years | ||

| Income | <20,000 | 12 (7%) | <20,000 | 11 (6.4%) |

| 20,001–30,000 | 15 (8.8%) | 20,001–30,000 | 19 (11.1%) | |

| 30,001–50,000 | 40 (23.4%) | 30,001–50,000 | 45 (26.3%) | |

| 50,001–75,000 | 47 (27.5%) | 50,001–75,000 | 36 (21.1%) | |

| >75,000 | 52 (30.4%) | >75,000 | 47 (27.5%) | |

| Not reported | 5 (2.9%) | Not reported | 13 (7.6%) | |

| Education | High school graduate or less | 26 (15.1%) | High school graduate or less | 45 (26.3%) |

| Some college | 50 (29.1%) | Some college | 56 (32.8%) | |

| College graduate | 36 (20.9%) | College graduate | 31 (18.1%) | |

| Graduate/professional school | 59 (34.3%) | Graduate/professional school | 37 (21.6%) | |

| Not reported | 1 (.6%) | Not reported | 2 (1.2%) | |

| Ethnicity | Caucasian | 147 (86.0%) | Caucasian | 139 (81.3%) |

| Black/African American | 11 (6.4%) | Black/African American | 9 (5.3%) | |

| Latino/Hispanic | 3 (1.8%) | Latino/Hispanic | 9 (5.3%) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 5 (2.9%) | Asian/Pacific Islander | 8 (4.7%) | |

| Other | 5 (2.9%) | Other | 4 (2.3%) | |

| Not reported | 2 (1.1%) | |||

| Work status | Full time | 54 (31.6%) | Full-Time | 39 (22.8%) |

| Part time | 17 (9.9%) | Part-Time | 27 (15.8%) | |

| Retired | 95 (55.6%) | Retired | 96 (56.1%) | |

| No job/not reported | 5 (2.9%) | No job/not reported | 9 (5.3%) | |

| Stage of cancer | A | 85 (49.7%) | ||

| B | 46 (26.9%) | |||

| C | 18 (10.5%) | |||

| D | 7 (4.1%) | |||

| Not sure | 15 (8.8%) | |||

| Treatment | Radical Prostatectomy | 61 (35.5%) | ||

| Radiation | 29 (16.9%) | |||

| Orchiectomy | 6 (3.5%) | |||

| Lupron/Zoladex shots | 54 (31.4%) | |||

| Flutamide pills | 21 (12.2%) | |||

| Variable | Patient (male) | Spouse (female) | ||

| Latency since diagnosis | 5.37 mos (SD=4.71 mos) |

Procedures

Flyers were used to recruit couples to participate in the larger randomized clinical trial that was testing the efficacy of a problem-solving intervention for improving quality of life for spouses of men with prostate cancer. In addition, physicians, support group leaders, and leaders of community businesses and organizations made personal one-to-one appeals to potential participants. Posters were displayed in waiting rooms of collaborating physicians, medical centers, churches, beauty salons, and barber shops. In addition, physicians sent a personal letter as well as a study flyer to their eligible patients, and several made personal phone calls to invite participation. Print (e.g., flyers, newsletters, newspaper press releases, newspaper advertisement) and electronic (radio and Internet) media were also utilized to recruit participants. Patients or spouses who called to express interest in the study were given information about study requirements, then underwent a brief telephone screening to confirm eligibility.

A baseline assessment was then scheduled. Research assistants conducted these assessments in participants’ homes or at a place that was convenient for them. At the baseline assessment, the project and eligibility requirements were again explained as part of the consenting process. Baseline assessments included a packet of self-report questionnaires as well as a general inquiry form regarding the couple’s demographic characteristics. After baseline assessments were completed, couples were randomly assigned to intervention versus control conditions. Spouses were randomized into either the intervention arm, which received six to eight sessions of a problem-solving intervention [17] in addition to encouragement to continue with their standard supportive care, or to the standard supportive care control arm where the spouses were encouraged to continue receiving support from their usual sources (doctors, therapists, family members, etc). Approximately 2 months after the baseline assessment, participants completed another set of self-report measures to assess distress and coping. To measure long-term effects of the intervention, participants also completed a final assessment 6 months after baseline. For the current cross-sectional study, we examined data from the baseline assessments that were completed before randomization.

Measures

Social Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised (SPSI-R) [15]: This measure was completed by the spouse. The SPSI-R is a 52-item self-report questionnaire that measures five dimensions of social problem-solving: two problem-orientation dimensions (positive and negative) and three problem-solving dimensions (rational problem-solving, impulsivity/carelessness style, and avoidance style). An SPSI-R total score is calculated to reflect the person’s general level of problem-solving, with higher scores indicating better problem-solving skills. Studies have also demonstrated a robust two-factor structure of the measure: constructive problem-solving (positive problem orientation and rational problem-solving subscales) and dysfunctional problem-solving (avoidance style, impulsive/carelessness style, and negative problem orientation subscales) [32, 34]. Psycho-metrically, the SPSI-R is characterized by strong reliability estimates and has been shown to have construct validity [15].

Profile of Mood States (POMS) [31]: This self-report questionnaire was completed by both the patient and spouse. The POMS is a 65-item, five-point adjective rating scale with six factor-analytically derived scales designed to measure: (1) tension–anxiety, (2) depression–dejection, (3) anger–hostility, (4) vigor–activity, (5) fatigue–inertia, and (6) confusion–bewilderment. As a global measure of affective state, a total mood disturbance score can be calculated by summing the six scale scores. High scores in each of the scales (except for vigor-activity) represent worse mood while low scores signify better mood. The POMS has well-documented reliability and validity and has been widely used in studies of cancer patients [22, 35, 37, 38] and spouses [9], including patients coping with prostate cancer [10].

Analyses

After the descriptive statistics were evaluated, latent variable modeling was conducted to determine the factorial structure of the target measures via confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and the structural relations between the latent variables representing these measures via structural equation modeling (SEM). In CFA the commonality among the observed variables (e.g., items from the POMS) is modeled as a latent variable (e.g., representing general distress), thus reducing the amount of measurement error in the target latent variable. This (these) latent variable(s) can then be used in a structural model in which the directional relations among these latent variables are analyzed (Fig. 1). While latent variable modeling does impose a directional model on the relations between variables, it does not mean that one has established causality. To determine if the hypothesized CFA and SEM models fit well, EQS was used [6]. Past research has shown that using the chi-square likelihood ratio test to determine overall model fit is unsatisfactory for numerous reasons [36]. Because of these limitations, researchers [23] have suggested using multiple measures of descriptive model fit. In the current study, the following measures were employed: (a) the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) [5] with values greater than 0.93 indicating reasonable model fit, and (b) the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) [24] with values less than 0.08 indicating reasonable model fit. In addition, the chi-square difference test was used to compare the relative fit of two nested models.

Results

Sample characteristics

Sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. Patients’ ages ranged from 41–89 (mean=65.5, SD=9.96) years. Spouses’ ages ranged from 32–86 (mean=61.29, SD= 10.68) years. A majority of the sample was Caucasian (86% of patients and 81% of spouses), and over half of the sample had combined annual incomes over $75,000. The sample was also fairly well educated with 55% of patients and 40% of spouses reporting having completed at least a college degree. Most (77%) of the patients were diagnosed with stages A and B neoplasms. Means and standard deviations of study measures are presented in Table 2. In general, POMS and SPSI-R scores were comparable to reported means in other studies with cancer populations [22, 31, 35, 37, 38], which have typically shown patterns of elevation in depression, tension-anxiety, fatigue, confusion-bewilderment, and total mood disturbance [31].

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations of measures used. SD standard deviation, POMS Profile of Mood States, SPSI-R Social Problem-Solving Inventory Revised

| Measure | Range of scores | Patient mean scores (SD) | Spouse mean scores (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| POMS total mood disturbance | −32 to 168 | 17.15 (33.22) | 26.70 (37.04) |

| POMS tension–anxiety scale | 0–36 | 8.10 (6.27) | 10.26 (7.28) |

| POMS depression–dejection scale | 0–60 | 7.61 (9.27) | 10.06 (10.41) |

| POMS anger–hostility scale | 0–48 | 6.38 (6.99) | 7.83 (8.09) |

| POMS vigor–activity scale | 0–32 | 18.67 (6.39) | 17.49 (7.17) |

| POMS fatigue–inertia scale | 0–28 | 7.95 (6.39) | 8.91 (7.33) |

| POMS confusion–bewilderment scale | 0–28 | 5.77 (4.53) | 7.12 (5.19) |

| SPSI-R total score | 0–20 | N/A | 14.26 (2.34) |

| SPSI-R constructive problem-solving | 0–100 | N/A | 61.31 (15.88) |

| SPSI-R dysfunctional problem-solving | 0–108 | N/A | 25.24 (15.36) |

| SPSI-R positive problem orientation | 0–20 | N/A | 13.22 (3.57) |

| SPSI-R negative problem orientation | 0–40 | N/A | 10.14 (6.55) |

| SPSI-R rational problem-solving | 0–80 | N/A | 48.09 (13.32) |

| SPSI-R avoidance style | 0–28 | N/A | 6.23 (4.97) |

| SPSI-R impulsive/careless style | 0–40 | N/A | 8.86 (6.85) |

Confirmatory factor analysis of measured variables

Before model fit was evaluated, confirmatory factor analyses were conducted to check the factor structure of the latent variables. Goodness of fit indices on the factor structures of each latent variable are presented in Table 3. Multivariate analyses of normality revealed non-normal item distributions for patient and spouse POMS but because it is a well-established measure with good psychometric properties and its factors had robust factor loadings (see Table 3), normality was assumed in running the structural equation modeling.

Table 3.

Summary of goodness-of-fit statistics for confirmatory factor analysis of measured variables. POMS Profile of Mood States, SPSI-R Social Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised, DF degrees of freedom, χ2chi square, CFI comparativefit index, SRMR standard root mean squared residual

| Factor | DF | χ2 | CFI | SRMR | Factor Loadings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spouse POMSa | 9 | 16.49, p=0.057 | 0.988 | 0.034 | 0.595–0.914 |

| Patient POMSb | 9 | 46.04, p=0.0001 | 0.948 | 0.058 | 0.626–0.932 |

| Spouse SPSI-R five factora | 5 | 125.85, p=0.0001 | 0.578 | 0.159 | 0.255–0.803 |

| Spouse SPSI-R two factora | 5 | 40.61, p=0.0001 | 0.876 | 0.052 | 0.651–1.00 |

predictor variables

outcome variables

Non-normality and poor fit were shown when the items of the SPSI-R were tested (Table 3). The five-factor structure was shown to have poor fit, so the two-factor structure was tested based on literature suggesting that SPSI-R scores are more robust using these two composite scores than using the five subscales and total scores [32, 34]. Subsequent confirmatory analyses demonstrated that factor loadings significantly improved when a two-factor structure was used (Table 3).

Structural equation modeling analyses

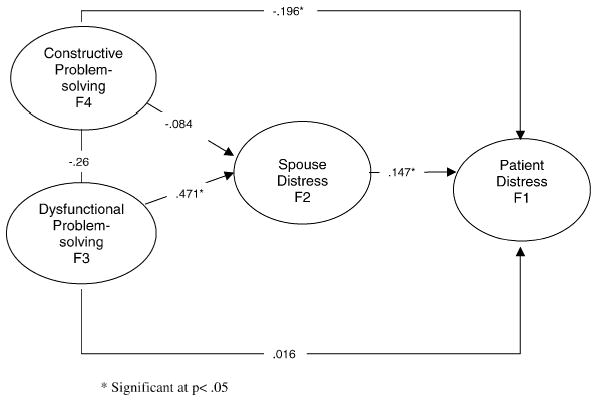

These two factors of the SPSI-R (constructive versus dysfunctional problem-solving) were incorporated into the conceptual model. The model was tested using EQS, and fit statistics indicated that the fit was good: X2(115, N=172) =273, p<0.05; CFI=0.91; and SRMR=0.075. Factor loadings for all latent variables were significant (all were above 0.4) (Table 4). The paths were all significant, except for those between constructive problem-solving and spouse distress and between dysfunctional problem-solving and patient distress. The final model is shown in Fig. 2.

Table 4.

Standardized factor loadings. TA tension–anxiety, DD depression–dejection, AH anger–hostility, VA vigor–activity, FI fatigue–inertia, CB confusion–bewilderment, PPO positive problem orientation, NPO negative problem orientation, ICS impulsivity/carelessness scale, AS avoidance scale, RPS rational problem-solving

| Item | Factor | Standardized solution |

|---|---|---|

| Patient POMS TA a | Patient distress | 0.888 |

| Patient POMS DDa | Patient distress | 0.931 |

| Patient POMS AHa | Patient distress | 0.739 |

| Patient POMS VA a | Patient distress | −0.626 |

| Patient POMS FIa | Patient distress | 0.692 |

| Patient POMS CBa | Patient distress | 0.855 |

| Spouse POMS TA b | Spouse distress | 0.910 |

| Spouse POMS DDb | Spouse distress | 0.876 |

| Spouse POMS AHb | Spouse distress | 0.645 |

| Spouse POMS VAb | Spouse distress | −0.593 |

| Spouse POMS FIb | Spouse distress | 0.763 |

| Spouse POMS CBb | Spouse distress | 0.837 |

| Spouse SPSI-R PPOb | Constructive problem-solving | 0.905 |

| Spouse SPSI-R NPOb | Dysfunctional problem-solving | 0.823 |

| Spouse SPSI-R ICSb | Dysfunctional problem-solving | 0.628 |

| Spouse SPSI-R ASb | Dysfunctional problem-solving | 0.761 |

| Spouse SPSI-R RPSb | Constructive problem-solving | 0.717 |

outcome variables

predictor variables

Fig. 2.

Final model

Discussion

Previous studies have documented that spouses are affected by the diagnosis of cancer [11, 19, 25, 26, 29]. Results of this study show that patient and spouse distress are related. This suggests that it is important to study both patient and spouse distress and quality of life. Spouse coping is conceptualized as constructive problem-solving (rational problem-solving; positive problem orientation) and dysfunctional problem-solving (avoidance style, impulsivity/carelessness, and negative problem orientation). Spouse coping has also been shown to be related to spouse distress. Interestingly, only dysfunctional problem-solving is significantly related to spouse distress (r=0.471). This is consistent with the literature that the negative problem orientation is related to negative affect and psychological distress [12]. This has implications for future interventions, suggesting that targeting dysfunctional problem-solving rather than constructive problem-solving might be more helpful in reducing distress.

Results show that spouse coping is also related to patient distress. There is a significant negative correlation between constructive problem-solving and patient distress, suggesting that better spouse coping is equated with less patient distress. Spouse dysfunctional problem-solving is also related to patient distress, but unlike constructive problem-solving, this relationship is fully mediated by spouse distress. Therefore, it is through spouse distress that spouse dysfunctional problem-solving affects patients.

These results have implications for future interventions. It is important for spouses of patients with prostate cancer to have good problem-solving skills since the spouse’s constructive coping has a direct inverse relationship with the patient’s distress. However, dysfunctional problem-solving may be a more important area of intervention since it not only directly affects spouse distress, it also indirectly affects patient distress as well.

There are several limitations to this study. Participants were from one geographic region and were mostly well educated, Caucasian couples of upper socioeconomic levels. It was not possible to collect information on persons who were exposed to information about the study through recruitment efforts and would have been eligible but decided not to participate; therefore, it is difficult to ascertain whether results can be generalized to all prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Same-sex dyads were considered eligible for the study; however, none enrolled. Measurement of problem-solving and distress was limited to self-report, paper-and-pencil questionnaires, and the instruments used were not specific to prostate cancer in their focus. Other ways of measuring the impact of the diagnosis should be included in future studies, such as biological assays, functional dyadic impairment, or real-life coping of spouses, not just a self-report of their coping styles.

Results of this study demonstrate that the spouse’s distress mediates the relationship between the spouse’s dysfunctional problem-solving and the patient’s distress, underscoring the importance of assessing spouse distress and coping. However, the cross-sectional design of the present study lends caution to interpretation of these results. The larger randomized clinical trial testing the efficacy of problem-solving therapy may provide richer results about the relationships of problem-solving and spouse and patient distress. Clinicians may also find it helpful to identify those spouses who are distressed and assess their coping styles. A recent study by Sahler et al. showed that mothers with cancer exhibited changes in mood that were influenced by dysfunctional problem-solving rather than constructive problem-solving. Interventions on avoidant coping or impulsive decision making may be important areas for future studies [32].

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge all the couples who agreed to participate in this study and who shared very intimate details about their lives with us. The following institutions, organizations, and health providers in San Diego County were very generous with their time and effort in helping us recruit for this study: American Cancer Society; Kaiser Permanente; Naval Medical Center San Diego; Informed Prostate Cancer Support Group; Oncology Therapies of Vista; Prostate Cancer Research and Education Foundation; Radiation Medical Group; San Diego Prostate Cancer Support Group; Solana Beach Presbyterian Church; The Wellness Community San Diego; UCSD Rebecca and John Moores Cancer Center; UCSD Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT); UCSD Stein Institute for Research in Aging; Veterans Health Administration San Diego. The following were key figures in recruitment: Christopher Amling, M.D; Israel Barken, M.D; Donald Fuller, M.D.; Robert W. Hathorn, M.D.; Peter Johnstone, M.D.; Mehdi Kamarei, M.D.; Francisco Pardo, M.D.; Marilyn Sanderson, R.N.; Carol Salem, M.D., Joseph Schmidt, M.D; Stephen Seagren, M.D.; Kenneth Shimizu, M.D; Clayton Smiley, M.D.; and Reverend Doctor Tom Theriault. The authors would also like to acknowledge all the undergraduate and graduate students who contributed time, energy, and hard work in completing this research project. This project was made possible from funding from the National Cancer Institute R2564745 and the California Cancer Research Program (CCRP) 99–00556V-10049.

References

- 1.Allen S, Shah A, Nezu A, Nezu C, Ciambrone D, et al. A problem-solving approach to stress reduction among younger women with breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94:3089–3100. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2004. Cancer facts and figures 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baider L, Koch U, Esacson R, De-nour A. Prospective study of cancer patients and their spouses: The weakness of marital strength. Psychooncology. 1998;7:49–56. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199801/02)7:1<49::AID-PON312>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banthia R, Malcarne V, Varni J, Ko C, Sadler G, Greenbergs H. The effects of dyadic strength and coping styles on psychological distress in couples faced with prostate cancer. J Behav Med. 2003;26:31–52. doi: 10.1023/a:1021743005541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psych Bull. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bentler PM, Wu EJC. Multivariate Software; Encino: 1995. EQS for Windows User’s Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanchard C, Toseland R, McCallion P. The effects of problem-solving intervention with spouses of cancer patients. J Psych Oncol. 1996;14:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bucher J, Loscalzo M, Zabora J, Houts P, Hooker C, BrintzenhofeSzoc K. Problem-solving cancer care education for patients and caregivers. Cancer Pract. 2001;9:66–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2001.009002066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bultz B, Speca M, Brasher P, Geggie P, Page S. A randomized controlled trial of a brief psychoeducational support group for partners of early stage breast cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2000;9:303–313. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200007/08)9:4<303::aid-pon462>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlson LE, Speca M, Patel KD, Goodey E. Mindfulness-based stress reduction in relation to quality of life, mood, symptoms of stress, and immune parameters in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:571–581. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000074003.35911.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cassileth B, Lusk E, Miller D, Brown L, Miller C. Psychosocial correlates of survival in advanced malignant disease. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1551–1555. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198506133122406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang E, D’Zurilla T. Relations between problem orientation and optimism, pessimism, and trait affectivity: A construct validation study. Behavior Res Ther. 1996;34:185–194. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark J, Inui T, Silliman R, Bokhour B, Krasnow S, et al. Patients’ perceptions of quality of life after treatment for early prostate cancer. J Clin Psychol. 2003;21:3777–3784. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Zurilla T, Sheedy C. Relation between social problem-solving ability and subsequent level of psychological stress in college students. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61:841–846. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.5.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Zurilla T, Chang E, Nottingham E, Faccini L. Social problem-solving deficits and hopelessness, depression, and suicidal risk in college students and psychiatric inpatients. J Clin Psychol. 1998;54:1091–1107. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199812)54:8<1091::aid-jclp9>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.D’Zurilla T, Nezu A, Maydeu-Olivares A. Multi-Health Systems; North Tonawanda: 2002. Social Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised (SPSI-R) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eton D, Lepore S. Prostate cancer and health-related quality of life: A review of the literature. Psychooncology. 2002;11:307–326. doi: 10.1002/pon.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Given C, Stommel M, Given B, Osuch J, Kurtz M, Kurtz J. The influence of cancer patients’ symptoms and functional states on patients’ depression and family caregivers’ reaction and depression. Health Psychol. 1993;12:277–285. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.4.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gotay C. The experience of cancer during early and advanced stages: The views of patients and their mates. Soc Sci Med. 1984;18:605–613. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(84)90076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harden J, Schafenacker A, Northouse L, Mood D, Smith D, et al. Couples’ experiences with prostate cancer: focus group research. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29:701–709. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.701-709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holland J, Korzun A, Tross S, Silberfarb P, Perry M, et al. Comparative psychological disturbance in patients with pancreatic and gastric cancer. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:982–986. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.8.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoyle RH. Confirmatory factor analysis. Handbook of applied multivariate statistics and mathematical modeling. In: Tinsley HEA, Brown SD, editors. Academic Press; San Deigo: 2000. pp. 465–497. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaye J, Gracely E. Psychological distress in cancer patients and their spouses. J Cancer Educ. 1993;8:47–52. doi: 10.1080/08858199309528207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keitel M, Zevon M, Rounds J, Petrelli N, Karakousis C. Spouse adjustment to cancer surgery: Distress and coping responses. J Surg Oncol. 1990;43:148–53. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930430305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kornblith A, Herr H, Ofman U, Scherr H, Holland J. Quality of life of patients with prostate cancer and their spouses. Cancer. 1994;73:2791–2802. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940601)73:11<2791::aid-cncr2820731123>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kunkel E, Bakker J, Myers R, Oyesanmi O, Gomella L. Biopsychosocial aspects of prostate cancer. Psychosomatics. 2000;41:85–94. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.41.2.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurtz M, Kurtz J, Given C, Given B. Relationship of caregiver reactions and depression to cancer patients’ symptoms, functional states and depression-A longitudinal view. Soc SciMed. 1995;40:837–846. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00249-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malinski S, Heilemann M, McCorkle R. From “death sentence” to “good cancer”: Couples’ transformation of a prostate cancer diagnosis. Nurs Res. 2002;51:391–397. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200211000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McNair D, Lorr M, Droppleman L. EdiTS/Educational and Industrial Testing Service; San Diego: 1992. EdiTS manual for the profile of mood states. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nezu A, Nezu C, McClure K, Felgoise S, Houts P. Project Genesis: Assessing the efficacy of problem-solving therapy for distressed adult cancer patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:1036–1048. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sahler O, Varni J, Fairclough D, Butler R, Noll R, et al. Problem-solving skills training for mothers of children with newly diagnosed cancer: A randomized trial. J Dev Beh Pediatr. 2002;23:77–86. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200204000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sahler O, Fairclough D, Phipps S, Mulhern R, Dolgin M, et al. Using problem-solving skills training to reduce negative affectivity in mothers of children with newly diagnosed cancer: Report of a multi-site randomized trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004 doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.272. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spiegel D, Bloom J, Yalom I. Group support for patients with meta-static cancer. A randomized outcome study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:527–533. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780300039004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanaka JS. Multifaceted conceptions of fit in structural equation models. In: Bollen KA, Long, JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Sage; Newbury Park: 1993. pp. 10–39. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taylor SE, Lichtmain RR, Wood JV. Attributions, beliefs about control and adjustment to breast cancer. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1984;46:489–502. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.46.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor SE, Lichtmain RR, Wood JV, Bluming AZ, Dosik GM, Leibowitz RL. Illness-related and treatment-related factors in psychosocial adjustment to breast cancer. Cancer. 1985;55:2503–2513. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850515)55:10<2506::aid-cncr2820551033>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Visser A, van Andel G. Psychosocial and educational aspects in prostate cancer patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;49:203–206. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(03)00024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]