Abstract

Clostridium difficile toxin B (TcdB) has been studied extensively by using cell-free systems and tissue culture, but, like many bacterial toxins, the in vivo targets of TcdB are unknown and have been difficult to elucidate with traditional animal models. In the current study, the transparent Danio rerio (zebrafish) embryo was used as a model for imaging of in vivo TcdB localization and organ-specific damage in real time. At 24 h after treatment, TcdB was found to localize at the pericardial region, and zebrafish exhibited the first signs of cardiovascular damage, including a 90% reduction in systemic blood flow and a 20% reduction in heart rate. Within 72 h of exposure to TcdB, the ventricle chamber of the heart became deformed and was unable to contract or pump blood, and the fish exhibited extensive pericardial edema. In line with the observed defects in ventricle contraction, TcdB was found to directly disrupt coordinated contractility and rhythmicity in primary cardiomyocytes. Furthermore, using a caspase-3 inhibitor, we were able to block TcdB-related cardiovascular damage and prevent zebrafish death. These findings present an insight into the in vivo targets of TcdB, as well as demonstrate the strength of the zebrafish embryo as a tractable model for identification of in vivo targets of bacterial toxins and evaluation of novel candidate therapeutics.

Keywords: bacterial toxin, Clostridium difficile-associated disease, large clostridial toxins

Protein toxins are produced by bacterial pathogens during disease and have evolved different functions, ranging from pore formation in plasma membranes to enzymatic activities that alter intracellular signaling, cell cycle, apoptosis, and protein synthesis in targeted cells (1). Mechanisms of receptor binding, cell entry, membrane insertion, and enzymology are routinely determined by using a broad range of cell types in vitro, yet for many toxins, the cell types targeted during disease are unknown (2).

Clostridium difficile toxin B (TcdB) is an example of a bacterial toxin studied extensively in vitro, but the in vivo activities remain poorly understood (3). TcdB is a potent (LD50 = 200 ng/kg) intracellular bacterial toxin; the protein enters cells by receptor-mediated endocytosis; translocates to the cytosol; hydrolyzes UDP-glucose; and transfers the liberated sugar to a reactive threonine in the effector-binding loops of the small GTPases Rho, Rac, and Cdc42 (4–7). As a result, cultured cells treated with TcdB exhibit changes in cell morphology and undergo apoptosis, eventually leading to the death of the cell (8–10). TcdB intoxicates numerous cell types in vitro, including fibroblasts, neuronal cells, epithelial cells, endothelial cells, lymphocytes, and hepatocytes (4, 11–15), yet whether any of these cell types are targeted during C. difficile-associated disease (CDAD) is unknown.

In addition to TcdB, C. difficile also produces toxin A (TcdA), which is known to function as an enterotoxin, causing gastrointestinal damage (16, 17). Previous studies have shown that TcdB is effective only when the intestinal mucosa is damaged (17), suggesting that the intestinal effects of TcdA facilitate the entry of TcdB into the bloodstream. The TcdA-mediated release of TcdB could explain the systemic complications observed in life-threatening cases of CDAD, including cardiopulmonary arrest (18), acute respiratory distress syndrome (19), multiple organ failure (20), renal failure (21), and liver damage (22). Hence, identification of the cells targeted in vivo by TcdB is needed to gain relevant insight into the disease-related activities of this toxin and advance our understanding of CDAD.

Identification of systemic targets of bacterial toxins such as TcdB has been limited, because it is difficult to directly visualize the impact of these proteins on major organs in real time. To overcome this problem, zebrafish embryos were used herein to characterize the systemic impact of TcdB in real time. Unlike other vertebrates, zebrafish embryos are transparent, and major organs can be visualized by standard light microscopy (23). Thus, zebrafish embryos provide a unique system for directly visualizing the temporal and spatial effects of TcdB intoxication. By using the zebrafish embryo as a model, in the current work, we have found that TcdB functions as potent cardiotoxin, reducing blood flow and ventricle contraction. Furthermore, corresponding to TcdB's known proapoptotic activity, a caspase-3 inhibitor was found to alleviate the cardiotoxic effects of TcdB. These findings provide important insight into the in vivo activities of TcdB and present the zebrafish embryo as a model for determining the systemic targets of bacterial toxins.

Results

Localizaton of TcdB in Zebrafish Embryos.

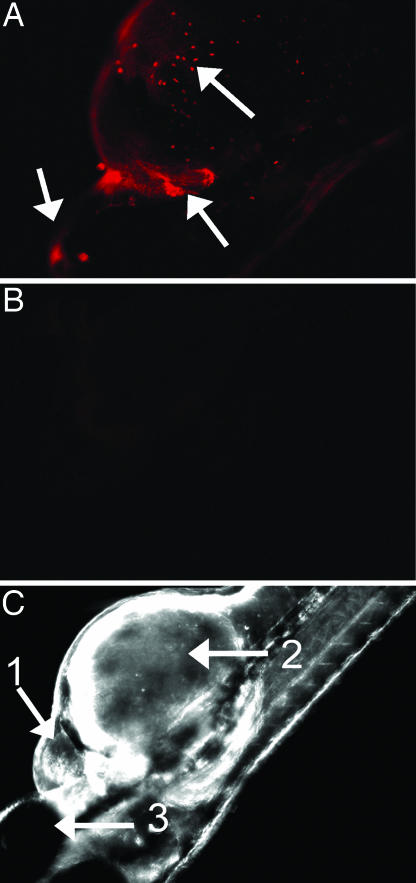

To determine the localization of TcdB, zebrafish were treated with TcdBAlexa-546 and examined by fluorescence microscopy for sites of toxin tropism. As shown in Fig. 1, after a 24-h treatment with the toxin, TcdBAlexa-546 localized at the frontal ventral portion of the fish, with specific foci formed within the pericardial region. Localization of TcdBAlexa-546 was also observed in an anatomical region corresponding to the outflow chamber of the heart (see arrow in Fig. 1A). Magnified views, as shown in Fig. 9 A and B, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, reveal intense localization near the cardiac region. In contrast, the negative control, BSAAlexa-546 did not show detectable anatomical localization within the zebrafish (Fig. 9 C and D).

Fig. 1.

TcdB localization observed in zebrafish. Fluorescently labeled TcdB was used to follow localization of the toxin to specific anatomical regions. (A) Zebrafish treated with 37 nM TcdBAlexa-546 for 24 h. Arrows indicate toxin accumulation around the pericardial sac as well as distinct foci on the yolk sac and upper cranial region. (B) Zebrafish treated with 37 nM TcdBAlexa-546 and 370 nM TcdB (RBD). (C) Brightfield image of zebrafish treated with 37 nM TcdBAlexa-546 and 370 nM TcdB (RBD). Arrows 1, 2, and 3 denote the heart, yolk sac, and eye of zebrafish, respectively.

To further demonstrate specificity of TcdB localization, competition experiments were performed by using the putative receptor-binding domain (RBD) of TcdB. As shown in Fig. 1B, cotreatment with a 30-fold molar excess of the TcdB RBD reduced the detectable levels of labeled toxin to that observed in the BSA control. Collectively, these observations suggested TcdB exhibits specific tissue tropism in the zebrafish, with the toxin primarily localizing to the yolk-sac, pericardial, and cardiac regions of the zebrafish.

Treatment of Zebrafish Embryos with TcdB Results in Damage to the Cardiovascular System.

Experiments were performed to determine the effects of TcdB on zebrafish physiology. For initial analysis, zebrafish embryos were collected 24 h after fertilization and exposed to TcdB, heat-inactivated TcdB, or buffer alone. Treatment with doses ranging from 0.037 to 0.37 nM did not cause detectable damage to the zebrafish embryos (data not shown). However, exposure of the embryos to doses of toxin ranging from 3.7 to 37 nM resulted in distinct dose-dependent changes in zebrafish physiology and anatomy.

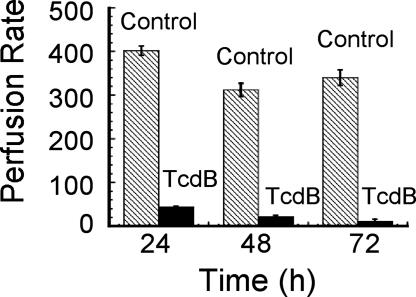

The time course and specific changes in physiology are summarized in Table 2, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. A decrease in heart rate was the first physiological change observed [72 ± 6 beats per 30 s in the control compared with 57 ± 3 beats per 30 s in TcdB-treated fish (P < 0.001)]. Corresponding to the reduced heart rate, a visible reduction in blood flow [calculated as the RBC perfusion rate] was also observed. In control fish, the RBC perfusion rate within the intersegmental veins was 402 ± 10.6 RBC per 30 s at 24 h after treatment. In comparison, in TcdB-treated zebrafish, the RBC perfusion rate within intersegmental veins was 44 ± 1.49 RBC per 30 s (P < 0.0001; see Fig. 2 and Movies 1 and 2, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Reduced blood flow was observed in the caudal and intersegmental veins and appeared to occur in the absence of detectable damage to the vascular endothelium. To confirm this, fli1::EGFP zebrafish, which express GFP in endothelial cells, were used to assess vein integrity after treatment with TcdB. As shown in Fig. 10B, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, despite a loss in blood flow, the veins of toxin-treated zebrafish appeared to be intact.

Fig. 2.

RBC perfusion rate and vein integrity of TcdB-treated zebrafish. RBC perfusion rate was used as a measurement of blood flow and calculated as the average number of RBC per 30 s in the intersegmental veins (n = 27), with error bars representing standard error. Zebrafish treated with TcdB (solid bars) had a reduced RBC rate compared with the heat-inactivated TcdB control (hatched bars).

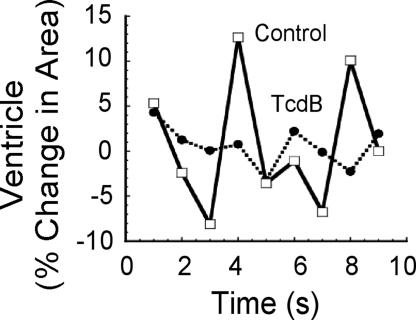

TcdB-treated zebrafish were examined for cardiac damage, as a possible explanation for the reduction in blood flow. Between 24 and 48 h after treatment, there was a decrease in ventricle chamber contractility and a loss in heart looping (see Fig. 3; see also Fig. 11 and Movies 3 and 4, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). As shown in Fig. 3, in control fish, the ventricle exhibited a dynamic change in size of 20% during contraction and expansion (see Movie 3). However, treatment with TcdB substantially reduced the change in ventricle size during beating (see Movie 4), indicating the heart was unable to contract and expand in a normal fashion. At ≈48 h after treatment, both the atrium and ventricle were deformed (Fig. 4). By 7 days after treatment, 100% of TcdB-treated fish exhibited pericardial edema, with 70% developing whole-body edema (Fig. 5). TcdB-treated fish survived between 7 and 10 days after initial exposure to TcdB, but by 11 days after treatment, 100% of the fish succumbed to the effects of the toxin. Similar cardiovascular defects were observed in fish treated with TcdB 24, 72, and 96 h after fertilization, indicating that toxin effects did not depend upon treatment at a particular stage of development (data not shown). Collectively, these observed defects indicated TcdB disrupts cardiac function.

Fig. 3.

Comparisons of contraction and expansion dynamics of the ventricle in control- and TcdB-treated zebrafish embryos. Plot of relative changes in ventricle size over a 10-s time period in zebrafish treated for 24 h with 37 nM heat-inactivated TcdB (solid line) or 37 nM TcdB (dotted line).

Fig. 4.

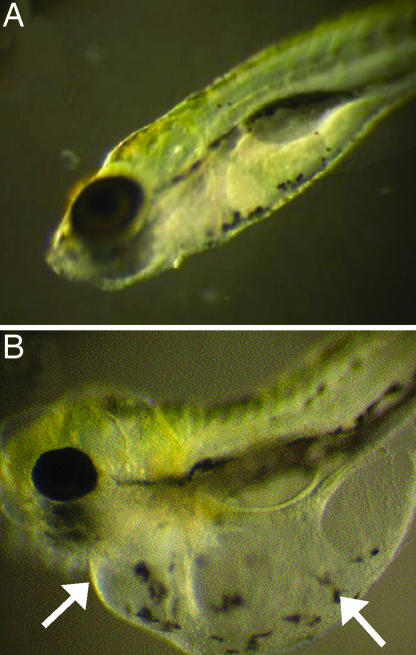

Morphological changes in zebrafish heart after exposure to TcdB. (A) Zebrafish embryos treated with 37 nM heat-inactivated TcdB for 48 h. (B) Zebrafish embryos treated with 37 nM TcdB for 48 h.

Fig. 5.

Representative photographs of zebrafish after exposure to TcdB. (A) Zebrafish treated with heat-inactivated 37 nM TcdB for 72 h. (B) Zebrafish treated with 37 nM TcdB for 72 h. Arrows indicate regions of massive edema observed after cardiac damage.

Delivery of the TcdB Enzymatic Domain with a Surrogate System Results in Systemic Damage.

Experiments were next performed to determine whether the cardiotoxicity of TcdB was due to heightened sensitivity of this organ to the toxin's enzymatic activity, or whether this effect results from a preferential localization of the toxin to the heart. Arguably, if TcdB cardiotoxicity were due to specific toxin tropism, then delivery of the enzymatic domain with a system that targets multiple tissues, should reduce these effects, because the enzymatic domain would be distributed throughout the body. Alternatively, if cardiotoxicity were due to heightened sensitivity of cardiac tissue to the enzymatic activity of TcdB, the heart should be preferentially impacted despite localization of the enzymatic domain to multiple tissues. To address this issue, we took advantage of a previously described heterologous delivery system derived from the cell entry components of anthrax lethal toxin, which consists of Bacillus anthracis protective antigen (PA) and anthrax toxin lethal factor (LFn)TcdB1–556, a fusion protein consisting of the translocation active nontoxic 255 N-terminal residues of LFn and the enzymatic glucosylation region of TcdB (amino acids 1–556; refs. 24–26). Previous studies have shown that PA can target multiple tissues within the zebrafish (27, 28). As shown in Fig. 6, zebrafish embryos treated with PA and LFnTcdB1–556 exhibited widespread tissue damage, which differed substantially from that observed in TcdB-treated zebrafish. These findings suggest that TcdB-related cardiac damage may involve a specific tropism for cardiac tissue.

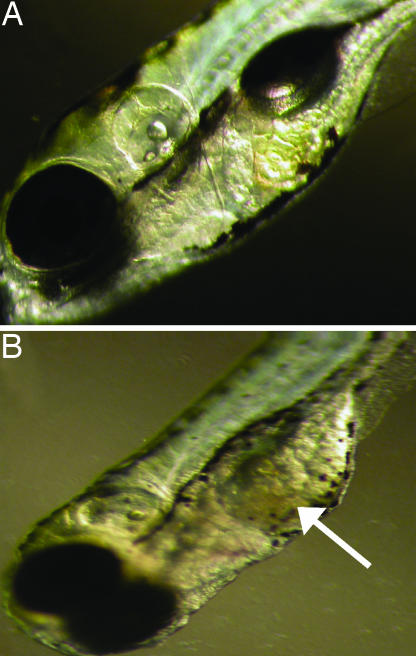

Fig. 6.

Representative photographs of zebrafish after a 72-h exposure to PA plus LFn-TcdB1–556. (A) Zebrafish treated with 0.85 nM LFn-TcdB1–556 alone at 72 h after fertilization resembled untreated zebrafish. (B) Zebrafish treated with 0.85 nM PA and LFn-TcdB1–556. Arrow indicates tissue damage (visualized as tissue discoloration).

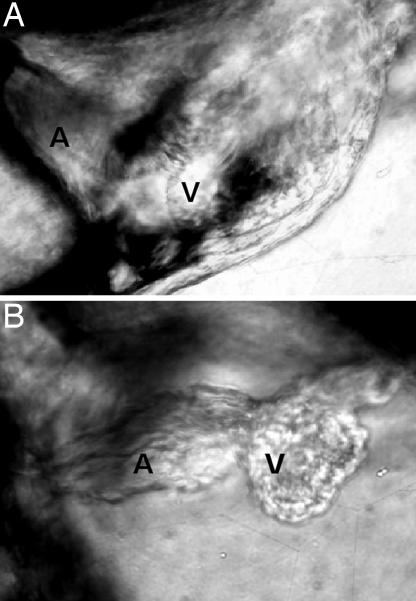

TcdB Modulates Cardiomyocyte Physiology.

Results from the zebrafish treatments indicated that TcdB could influence cardiac function, perhaps by directly targeting functional cells of the heart. To further elucidate TcdB-cardiotoxic effects, experiments next sought to determine whether this toxin is capable of disrupting the physiology of cardiomyocytes. In these experiments, cultured cardiomyocytes were treated with TcdB and examined for changes in overall morphology, contraction, and viability. Within 2 h of toxin treatment, the cardiomyocytes exhibited morphological changes. Phalloidin staining of actin in TcdB-treated cardiomyocytes revealed distinct changes in cellular structure when compared with cardiomyocytes treated with heat-inactivated TcdB (see Fig. 7A and B). Control cells had numerous dense bodies of fibrils and bundled Z bands (Fig. 7A), whereas these structures were undetectable in cardiomyocytes treated with TcdB (Fig. 7B). By 5 h after treatment, the cardiomyocyte contractions were less coordinated and arrhythmic (Fig. 7C; see also Movies 5 and 6, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Finally, 48 h after treatment, there was a 60% decline in cardiomyocyte viability (data not shown).

Fig. 7.

Impact of TcdB on primary RCm. (A) Rhodamine phalloidin actin stain of RCm treated with heat-inactivated TcdB (7.4 nM). (B) RCm treated with TcdB (7.4 nM) and stained for actin. (C) Plot of changes in the number of RCm contractions over time. RCm cells were treated with heat-inactivated TcdB (solid line) or TcdB (dotted line). Contractions were measured 4 h after treatment as number of contractions per 60 s.

Caspase-3 Inhibitor Reduces Cardiovascular Damage in TcdB-Treated Zebrafish.

TcdB is known to cause cytotoxicity by apoptosis, and blocking caspase activity in cell culture slows the rate of death after treatment with TcdB (10). Hence, experiments were designed to determine whether cardiotoxicity correlates with the ability of TcdB to induce apoptosis, and whether inhibition of apoptosis could provide protection against the systemic effects of this toxin. In these experiments, zebrafish embryos were treated with TcdB and cotreated with Ac-DMQD-CHO, a water-soluble tetrapeptide inhibitor of caspase-3. TcdB-treated and control zebrafish were observed for changes in heart beat and overall blood flow. As shown in Table 1, zebrafish treated with TcdB exhibited a significant decrease in heartbeats per 30 s as compared with the control, yet zebrafish cotreated with caspase-3 inhibitor presented heart rates similar to control zebrafish along with a normal RBC perfusion rate (Fig. 8). The events quantified in Fig. 8 can be viewed as a video (see Movie 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Furthermore, the addition of caspase-3 inhibitor decreased the frequency and severity of damage observed in the TcdB-treated zebrafish (see Fig. 12, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). These results indicate the cardiotoxic effects of TcdB can be alleviated by a caspase-3 inhibitor.

Table 1.

Heart rate of treated zebrafish

| Treatment | Heartbeat per 30 s, 72 h after treatment |

|---|---|

| Heat-inactivated TcdB | 72 ± 6 |

| Caspase-3 inhibitor | 76 ± 7 |

| TcdB | 57 ± 3 |

| TcdB + caspase-3 inhibitor | 78 ± 2 |

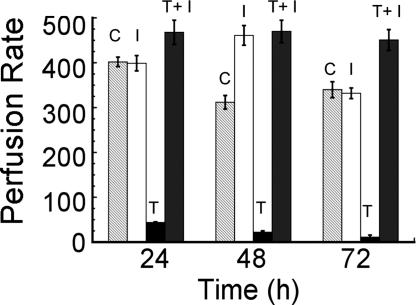

Fig. 8.

Caspase-3 inhibitor reduces the cardiotoxic effects of TcdB. After concomitant exposure to TcdB and caspase-3 inhibitor, zebrafish were examined for reduction of TcdB-related phenotype, specifically decrease in heart function. The RBC perfusion rate of treated zebrafish over time (C, heat-inactivated TcdB control; I, caspase-3 inhibitor IV; and T, TcdB). RBC perfusion rate is calculated as the average number of RBC per 30 s in the intersegmental veins (n = 27), with error bars representing standard error. Heart rate (Inset) was determined 72 h after exposure to heat-inactivated TcdB, caspase-3 inhibitor IV, TcdB plus caspase-3 inhibitor IV, or TcdB. Heart rate was determined in triplicate for each condition and is reported as the mean and standard error of five experimental samples.

Discussion

Tissue damage and inactivation of specific cell types by bacterial toxins are an integral part of many infections and are important for colonization, immune evasion, and progression of disease. Thus, toxin immunogenicity and mechanisms of action have been studied for over a century, leading to new vaccines and an understanding of these virulence factors at the molecular level. Yet, despite numerous advances in the study of bacterial toxins, little is known about cell types targeted in vivo (2). In particular, and important to the current study, are the facts that, although TcdB is a potent cytotoxin, has a low LD50, and causes rapid death in animal models, the overall physiological systems impacted by this toxin have not been identified.

Although in vitro studies have provided important insight into TcdB's mechanisms of cell entry, membrane translocation, and enzymatic activity, it is difficult to apply this knowledge to the in vivo setting. In vitro analysis can neither mimic toxin receptor availability within the host nor reflect overall organ sensitivity to TcdB. Therefore, to characterize TcdB's systemic effects, we sought an animal model that would allow direct in vivo visualization of events leading to death after exposure to the toxin. Contemporary models, such as higher-order primates, rodents (29), Drosophila melanogaster (30–32), and Caenorhabditis elegans (33, 34), were considered for assessing the systemic effects of TcdB, but these lacked many of the qualities needed for the current study. It is difficult to directly visualize all of the major organs in higher-order models, and the fruit-fly and nematode systems lack the organ complexity needed for a thorough study of systemic damage. In contrast, the zebrafish embryo provides several distinct advantages over these traditional models. In addition to having many of the major organs found in humans, zebrafish embryos are transparent, which allows direct visualization of labeled toxin and toxin-induced changes in anatomy and physiology (23). Indeed, these same characteristics have made the zebrafish a widely accepted model for the study of embryonic development and genetics (35) and infectious diseases (36–42).

The phenotypes of TcdB-treated zebrafish support the notion that intoxication with TcdB leads to cardiovascular damage. Indeed, many of the changes observed in the TcdB-treated embryos have been reported in mutant lines of zebrafish defective in genes necessary for a functional heart. For example, dead beat (ded; refs. 43 and 44) and heartstrings (hst; ref. 45) are documented to possess cardiac defects that result in poor contractility and pericardial edema (ded) or stretching and loss of function of cardiac chambers as well as a loss in circulation (hst). These phenotypes were observed in the TcdB-treated embryos, further suggesting that the toxin impacts cardiac function. Additionally, results from toxin localization experiments using TcdB labeled with a trackable marker and the delivery of the TcdB enzymatic domain with PA and LFn support the idea that the toxin preferentially localizes to the heart. A specific in vivo affinity for cardiac tissue may explain why TcdB can damage many cell types in vitro but primarily impacts the heart in the zebrafish.

In zebrafish embryo studies, loss in chamber contractility was observed, allowing for the identification of a relevant candidate cell type, cardiomyocytes, for further studies in cell culture. Whether cardiomyocytes are the only cardiac cells impacted by TcdB is not known; however, loss of cardiomyocytes will have the most dramatic impact on the heart and may provide an explanation for TcdB-related defects in contractility. These cells are central to heart contraction and the movement of blood; thus, even subtle intoxication events could have dramatic effects. Furthermore, unlike cardiac fibroblasts and endothelial cells, cardiomyocytes are not renewable, and loss of these cells can result in chronic heart problems (46, 47). It seems reasonable to predict that if other cells are impacted by TcdB within the heart, death of cardiomyocytes would have a more severe and sustained effect on the host.

In cardiac diseases that involve activation of apoptosis in cardiomyocytes, caspase inhibitors have been promoted as promising treatments (48–50). Moreover, prior work has shown that inhibitors of apoptosis, caspase inhibitors in particular, reduce the cytotoxic effects of TcdB (10). Thus, it was hypothesized that inhibition of caspase-3 would alleviate the cardiac damage caused by this toxin. The results of our study show that TcdB's damaging and fatal cardiotoxic effects could be prevented through the use of a caspase-3 inhibitor. This is an example in which a caspase inhibitor blocked in vivo effects of a bacterial exotoxin, which has not been previously described. Moreover, these results suggest these compounds and other modulators of apoptosis could be promising therapeutics for treating advanced CDAD.

It is important to consider the current findings in the context of CDAD in humans. Cardiotoxicity could explain many of the observed clinical signs of serious CDAD. Patients with advanced CDAD experience multiorgan failure, and decreases in cardiac function could be among the factors contributing to this event (20). Death of CDAD patients has also been directly associated with cardiac arrest (18, 51–53). Collectively, these data suggest that inactivation of Rho, Rac, and Cdc42 by TcdB leads to altered cardiac activity and cell death in the heart of CDAD patients. Ongoing studies assessing cardiac damage in infectious models of CDAD will help in directly addressing this hypothesis.

In summary, results from the current study provide insight into a possible mechanism by which C. difficile causes severe systemic damage during CDAD. By functioning as a cardiotoxin, TcdB may directly or indirectly cause much of the systemic damage observed in CDAD patients. These findings also indicate that the zebrafish embryo is a valuable model for identifying systemic targets of bacterial virulence factors, and that this model is useful in the in vivo assessment of toxin therapeutics.

Materials and Methods

Protein Isolation.

TcdB was isolated as described (54). Bacillus anthracis PA and LFnTcdB1–556 were isolated as described (24–26). The 2,165 nucleotides from the 3′ end of the tcdb gene, which encode for the putative RBD of TcdB, were cloned in-frame into the pET15b plasmid (Novagen, San Diego, CA). All recombinant proteins were expressed as a His6 fusion in Escherichia coli/BL-21 DE3 and isolated by using Ni2+ affinity chromatography according to the manufacturer's protocol (Novagen).

Fluorescent Labeling of Protein.

TcdB and BSA were labeled with a reactive fluorescent dye Alexa-Fluor-546, according to the manufacturer's instructions [Molecular Probes/Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA)]. The relative activity of labeled TcdB to unlabeled TcdB was determined by using a standard cytotoxicity assay. Labeling of TcdB did not reduce the effective cytotoxic dose of the toxin by >20%.

Zebrafish Maintenance and Care.

Wild-type zebrafish were obtained from Aquatic Eco-System (Apopka, FL), and mutant fli1::EGFP fish were obtained from the Zebrafish Information Network (ZFIN, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR). Zebrafish were maintained at 28.5°C on a 14-h light/10-h dark cycle in a Z plex unit (Aquatic Habitats, Apopka, FL) and matings, embryo collection, and preparation were performed as described (23).

In Vivo Toxin Localization Studies Using Fluorescently Labeled TcdB.

Zebrafish embryos were placed into a 96-well plate (five embryos per well) 24 h after fertilization and allowed to incubate with TcdBAlexa-546 (3.7–100 nM) or TcdBAlexa-546 (3.7–100 nM) and a 30-fold molar excess of TcdB RBD for 24 h. Control zebrafish were incubated with 100 nM BSAAlexa-546. Subsequently, zebrafish were rinsed 10 times in embryo water for 20 min and visualized by using an Olympus (Melville, NY) BX81 epifluorescent microscope. Images were captured and processed by using the Nikon (Florham Park, NJ) Spot Software.

Treatment of Zebrafish Embryos with TcdB and LFnTcdB1–556.

For TcdB studies, zebrafish embryos were placed (five embryos per well) into a 96-well plate and treated with 37 nM TcdB, heat-inactivated TcdB, or 20 mM Tris·HCl buffer in replicates of 10 (50 embryo per experimental condition). Similarly, LFnTcdB1–556-treated zebrafish were placed (five embryos per well) into a 96-well plate and treated with 0.42–0.85 nM PA and LFnTcdB1–556 in replicates of 10 (50 embryos per treatment). Controls included 0.85 nM PA or LFnTcdB1–556 and 20 mM Tris·HCl. The embryos were observed for 7 days after treatment for morphological changes by using a SZX-7 microscope with a DP70 camera (Nikon). All still and video images were captured and processed by using DP controller and DP manager software (Nikon). To calculate blood circulation, the RBC perfusion rate was measured by using the SZX-7 Nikon microscope with a DP70 video camera and is recorded as the number of blood cells detected within the intersegmental veins over a 30-s time period. RBC perfusion rate was measured in replicate countings in three separate veins in three separate fish and is reported as number of RBC per 30 s.

Treatment of Rat Cardiomyocytes with TcdB.

Rat cardiomyocyte (RCm) cells (Cell Applications, San Diego, CA) were seeded into 96-well plates, treated in triplicate with 7.4 nM TcdB or heat-inactivated TcdB for 5 h, and subsequently stained with rhodamine phalloidin according to the manufacturer's instructions (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen). Images were acquired by using a TCS NT confocal microscope (Leica, Deerfield, IL) and processed by using Confocal Software (Leica). RCm cell viability after TcdB treatment was quantified across a 72-h time period by using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo, Gaithersburg, MD).

Caspase-3 Inhibitor Assays.

Zebrafish embryos were placed into a 96-well plate (five embryos per well) in sterile embryo water, treated concomitantly with TcdB (37 nM) and caspase-3 inhibitor IV (Calbiochem, 500 μM), and observed up to 1 wk after treatment. Controls for this experiment included 500 μM caspase-3 inhibitor IV, TcdB (37 nM), and heat-inactivated TcdB (37 nM). The embryos were examined for changes in heart rate and RBC perfusion rate, as well as a phenotype using an SZX-7 Nikon microscope with a DP70 camera. All still and video images were captured and processed by using the DP controller and manager software.

Statistical Analysis of Data.

All statistical data were calculated by using Student's two-tailed t test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Public Health Service, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant HD044861.

Abbreviations

- TcdB

Clostridium difficile toxin B

- CDAD

Clostridium difficile-associated disease

- PA

protective antigen

- LFn

anthrax toxin lethal factor

- RBD

receptor-binding domain

- RCm

rat cardiomyocyte(s).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Schmitt CK, Meysick KC, O'Brien AD. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:224–234. doi: 10.3201/eid0502.990206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galan JE. J Exp Med. 2005;201:321–323. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Voth DE, Ballard JD. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:247–263. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.2.247-263.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bette P, Oksche A, Mauler F, von Eichel-Streiber C, Popoff MR, Habermann E. Toxicon. 1991;29:877–887. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(91)90224-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Florin I, Thelestam M. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983;763:383–392. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(83)90100-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Just I, Fritz G, Aktories K, Giry M, Popoff MR, Boquet P, Hegenbarth S, von Eichel-Streiber C. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10706–10712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Just I, Selzer J, Wilm M, von Eichel-Streiber C, Mann M, Aktories K. Nature. 1995;375:500–503. doi: 10.1038/375500a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boquet P. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;886:83–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang TW, Lin PS, Gorbach SL, Bartlett JG. Infect Immun. 1979;23:795–798. doi: 10.1128/iai.23.3.795-798.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qa'Dan M, Ramsey M, Daniel J, Spyres LM, Safiejko-Mroczka B, Ortiz-Leduc W, Ballard JD. Cell Microbiol. 2002;4:425–434. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wedel N, Toselli P, Pothoulakis C, Faris B, Oliver P, Franzblau C, LaMont T. Exp Cell Res. 1983;148:413–422. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(83)90163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linseman DA, Hofmann F, Fisher SK. J Neurochem. 2000;74:2010–2020. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0742010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torres J, Camorlinga-Ponce M, Munoz O. Toxicon. 1992;30:419–426. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(92)90538-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daubener W, Leiser E, von Eichel-Streiber C, Hadding U. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1107–1112. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.5.1107-1112.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazuski JE, Panesar N, Tolman K, Longo WE. J Surg Res. 1998;79:170–178. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1998.5398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donta ST, Sullivan N, Wilkins TD. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;15:1157–1158. doi: 10.1128/jcm.15.6.1157-1158.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lyerly DM, Saum KE, MacDonald DK, Wilkins TD. Infect Immun. 1985;47:349–352. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.2.349-352.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson S, Kent SA, O'Leary KJ, Merrigan MM, Sambol SP, Peterson LR, Gerding DN. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:434–438. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-6-200109180-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacob SS, Sebastian JC, Hiorns D, Jacob S, Mukerjee PK. Heart Lung. 2004;33:265–268. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dobson G, Hickey C, Trinder J. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1030. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1754-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cunney RJ, Magee C, McNamara E, Smyth EG, Walshe J. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:2842–2846. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.11.2842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakurai T, Hajiro K, Takakuwa H, Nishi A, Aihara M, Chiba T. Scand J Infect Dis. 2001;33:69–70. doi: 10.1080/003655401750064112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Westerfield M. The Zebrafish Book: A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Brachydanio rerio) Portland, OR: University of Oregon Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arora N, Leppla SH. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:3334–3341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milne JC, Blanke SR, Hanna PC, Collier RJ. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:661–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spyres LM, Qa'Dan M, Meader A, Tomasek JJ, Howard EW, Ballard JD. Infect Immun. 2001;69:599–601. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.1.599-601.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tucker AE, Salles II, Voth DE, Ortiz-Leduc W, Wang H, Dozmorov I, Centola M, Ballard JD. Cell Microbiol. 2003;5:523–532. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voth DE, Hamm EE, Nguyen LG, Tucker AE, Salles II, Ortiz-Leduc W, Ballard JD. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:1139–1149. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buer J, Balling R. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:195–205. doi: 10.1038/nrg1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D'Argenio DA, Gallagher LA, Berg CA, Manoil C. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:1466–1471. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.4.1466-1471.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dionne MS, Ghori N, Schneider DS. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3540–3550. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3540-3550.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mansfield BE, Dionne MS, Schneider DS, Freitag NE. Cell Microbiol. 2003;5:901–911. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alegado RA, Campbell MC, Chen WC, Slutz SS, Tan MW. Cell Microbiol. 2003;5:435–444. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ewbank JJ. Microbes Infect. 2002;4:247–256. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(01)01531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grunwald DJ, Eisen JS. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:717–724. doi: 10.1038/nrg892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pradel E, Ewbank JJ. Annu Rev Genet. 2004;38:347–363. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.092528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davis JM, Clay H, Lewis JL, Ghori N, Herbomel P, Ramakrishnan L. Immunity. 2002;17:693–702. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00475-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller JD, Neely MN. Acta Trop. 2004;91:53–68. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2003.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prouty MG, Correa NE, Barker LP, Jagadeeswaran P, Klose KE. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;225:177–182. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neely MN, Pfeifer JD, Caparon M. Infect Immun. 2002;70:3904–3914. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.7.3904-3914.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Sar AM, Appelmelk BJ, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Bitter W. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:451–457. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van der Sar AM, Musters RJ, van Eeden FJ, Appelmelk BJ, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Bitter W. Cell Microbiol. 2003;5:601–611. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stainier DY, Fouquet B, Chen JN, Warren KS, Weinstein BM, Meiler SE, Mohideen MA, Neuhauss SC, Solnica-Krezel L, Schier AF, et al. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1996;123:285–292. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rottbauer W, Just S, Wessels G, Trano N, Most P, Katus HA, Fishman MC. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1624–1634. doi: 10.1101/gad.1319405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garrity DM, Childs S, Fishman MC. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2002;129:4635–4465. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.19.4635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.MacLellan WR. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2000;15:128–135. doi: 10.1097/00001573-200005000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Itescu S, Schuster MD, Kocher AA. J Mol Med. 2003;81:288–296. doi: 10.1007/s00109-003-0432-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang JQ, Radinovic S, Rezaiefar P, Black SC. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;402:139–142. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00477-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holly TA, Drincic A, Byun Y, Nakamura S, Harris K, Klocke FJ, Cryns VL. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1999;31:1709–1715. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1999.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yaoita H, Ogawa K, Maehara K, Maruyama Y. Circulation. 1998;97:276–281. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.3.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Turk EE, Sperhake JP, Tsokos M. Leg Med (Tokyo) 2002;4:246–250. doi: 10.1016/s1344-6223(02)00050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Briel A, Veber B, Dureuil B. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 1997;16:911–912. doi: 10.1016/s0750-7658(97)89841-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Siarakas S, Damas E, Murrell WG. Toxicon. 1995;33:635–649. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(95)00003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qa'Dan M, Spyres LM, Ballard JD. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2470–2474. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2470-2474.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.