Abstract

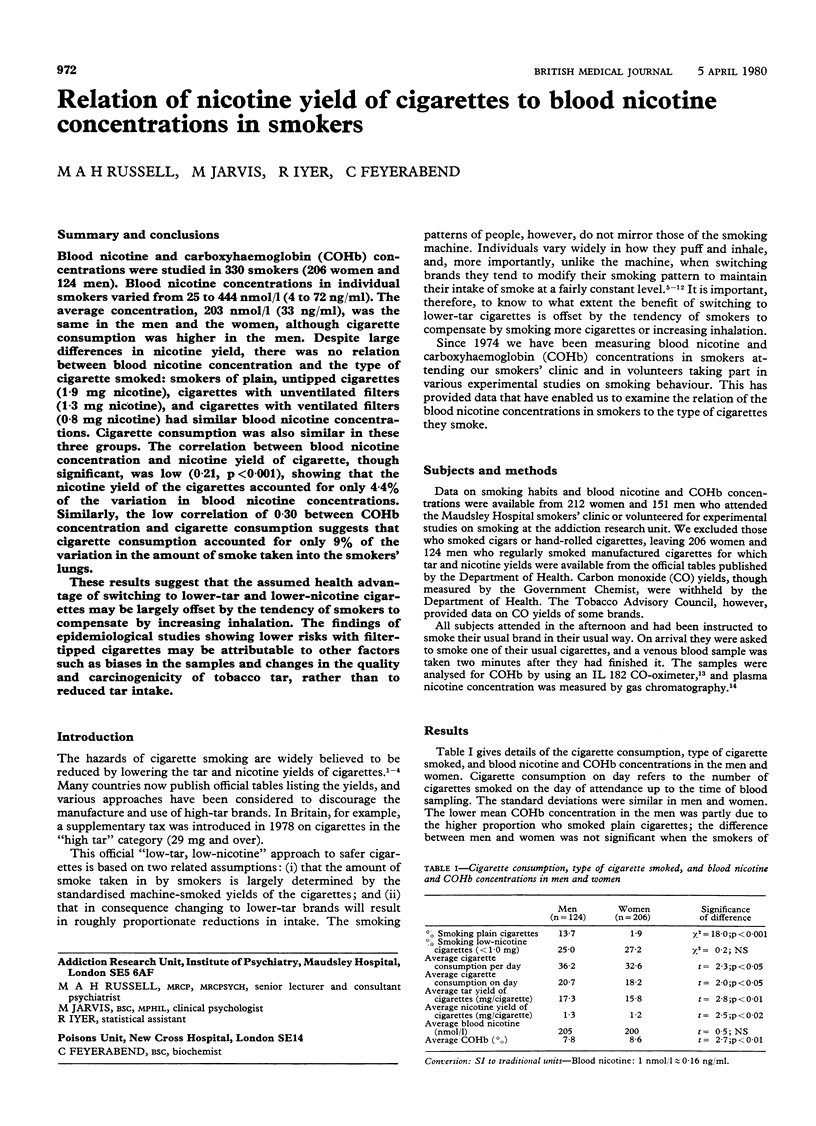

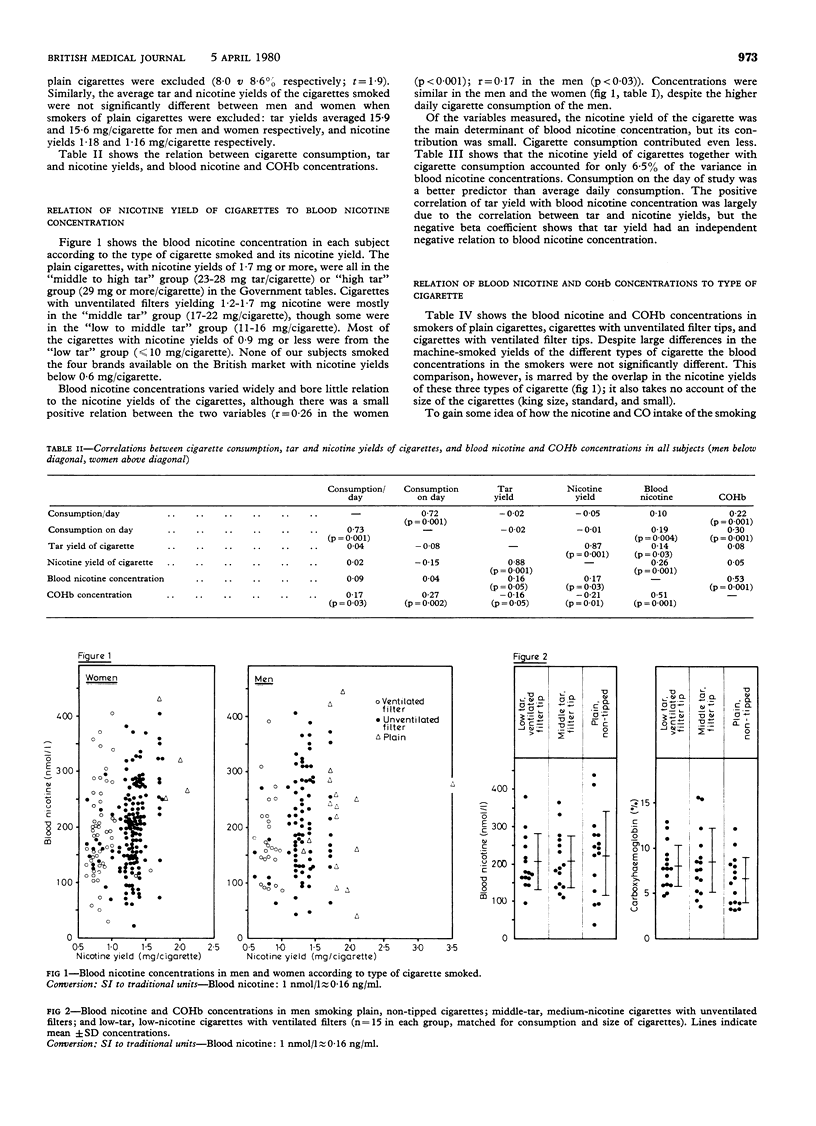

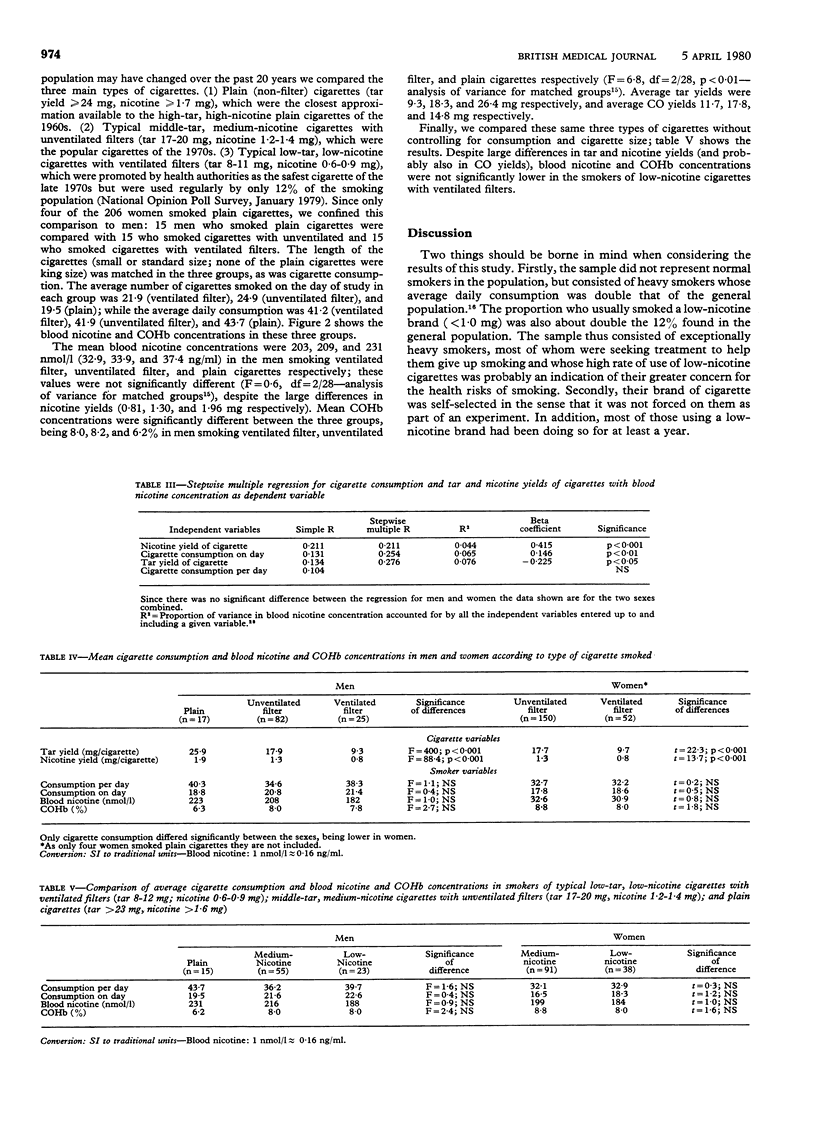

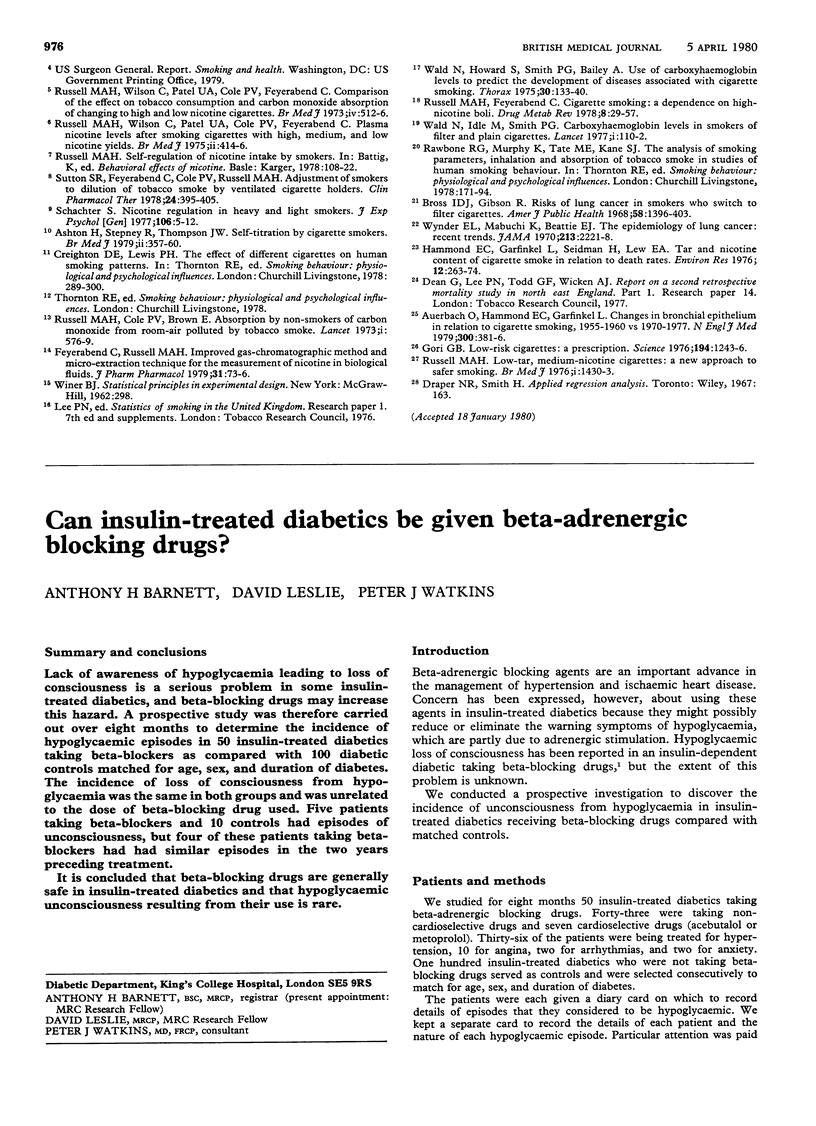

Blood nicotine and carboxyhaemoglobin (COHb) concentrations were studied in 330 smokers (206 women and 124 men). Blood nicotine concentrations in individual smokers varied from 25 to 444 nmol/l (4 to 72 ng/ml). The average concentration, 203 nmol/l (33 ng/ml), was the same in the men and the women, although cigarette consumption was higher in the men. Despite large differences in nicotine yield, there was no relation between blood nicotine concentration and the type of cigarette smoked: smokers of plain, untipped cigarettes (1.9 mg nicotine), cigarettes with unventilated filters (1.3 mg nicotine), and cigarettes with ventilated filters (0.8 mg nicotine) had similar blood nicotine concentrations. Cigarette consumption was also similar in these three groups. The correlation between blood nicotine concentration and nicotine yield of cigarette, though significant, was low (0.21, p < 0.001), showing that the nicotine yield of the cigarettes accounted for only 4.4% of the variation in blood nicotine concentrations. Similarly, the low correlation of 0.30 between COHb concentration and cigarette consumption suggests that cigarette consumption accounted for only 9% of the variation in the amount of smoke taken into the smokers' lungs. These results suggest that the assumed health advantage of switching to lower-tar and lower-nicotine cigarettes may be largely offset by the tendency of smokers to compensate by increasing inhalation. The findings of epidemiological studies showing lower risks with filter-tipped cigarettes may be attributable to other factors such as biases in the samples and changes in the quality and carcinogenicity of tobacco tar, rather than to reduced tar intake.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ashton H., Stepney R., Thompson J. W. Self-titration by cigarette smokers. Br Med J. 1979 Aug 11;2(6186):357–360. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6186.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach O., Hammond E. C., Garfinkel L. Changes in bronchial epithelium in relation to cigarette smoking, 1955-1960 vs. 1970-1977. N Engl J Med. 1979 Feb 22;300(8):381–385. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197902223000801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bross I. D., Gibson R. Risks of lung cancer in smokers who switch to filter cigarettes. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1968 Aug;58(8):1396–1403. doi: 10.2105/ajph.58.8.1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feyerabend C., Russell M. A. Improved gas chromatographic method and micro-extraction technique for the measurement of nicotine in biological fluids. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1979 Feb;31(2):73–76. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1979.tb13435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gori G. B. Low-risk cigarettes: a prescription. Science. 1976 Dec 11;194(4271):1243–1246. doi: 10.1126/science.996552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gori G. B., Lynch C. J. Toward less hazardous cigarettes. Current advances. JAMA. 1978 Sep 15;240(12):1255–1259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond E. C., Garfinkel L., Seidman H., Lew E. A. "Tar" and nicotine content of cigarette smoke in relation to death rates. Environ Res. 1976 Dec;12(3):263–274. doi: 10.1016/0013-9351(76)90036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M. A., Cole P. V., Brown E. Absorption by non-smokers of carbon monoxide from room air polluted by tobacco smoke. Lancet. 1973 Mar 17;1(7803):576–579. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)90718-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M. A., Feyerabend C. Cigarette smoking: a dependence on high-nicotine boli. Drug Metab Rev. 1978;8(1):29–57. doi: 10.3109/03602537808993776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M. A. Low-tar medium-nicotine cigarettes: a new approach to safer smoking. Br Med J. 1976 Jun 12;1(6023):1430–1433. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6023.1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M. A., Wilson C., Patel U. A., Cole P. V., Feyerabend C. Comparison of effect on tobacco consumption and carbon monoxide absorption of changing to high and low nicotine cigarettes. Br Med J. 1973 Dec 1;4(5891):512–516. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5891.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M. A., Wilson C., Patel U. A., Feyerabend C., Cole P. V. Plasma nicotine levels after smoking cigarettes with high, medium, and low nicotine yields. Br Med J. 1975 May 24;2(5968):414–416. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5968.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton S. R., Feyerabend C., Cole P. V., Russell M. A. Adjustment of smokers to dilution of tobacco smoke by ventilated cigarette holders. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1978 Oct;24(4):395–405. doi: 10.1002/cpt1978244395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wald N., Howard S., Smith P. G., Bailey A. Use of carboxyhaemoglobin levels to predict the development of diseases associated with cigarette smoking. Thorax. 1975 Apr;30(2):133–140. doi: 10.1136/thx.30.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wald N., Idle M., Smith P. G. Carboxyhaemoglobin levels in smokers of filter and plain cigarettes. Lancet. 1977 Jan 15;1(8003):110–112. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)91702-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynder E. L., Hoffmann D. Tobacco and health: a societal challenge. N Engl J Med. 1979 Apr 19;300(16):894–903. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197904193001605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynder E. L., Mabuchi K., Beattie E. J., Jr The epidemiology of lung cancer. Recent trends. JAMA. 1970 Sep 28;213(13):2221–2228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]