Abstract

We determined whether therapy for human renal cell carcinoma (HRCC) that grows in the kidney of nude mice by the specific epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor, PKI166, is directed against phosphorylated EGFR on tumor cells or on tumor-associated endothelial cells. EGFR+/transforming growth factor α (TGF-α)- SN12-PM6 HRCC cells were transfected with full-length sense TGF-α cDNA or vector control. SN12-PM6 cells expressing low or high levels of TGF-α were implanted into the kidney of nude mice. Only tumors produced by TGF-α+ HRCC cells contained tumor-associated endothelial cells expressing activated EGFR. Oral administration of PKI166 produced significant therapy only in TGF-A+ tumors, which correlated with apoptosis of tumor-associated endothelial cells. These data suggest that the production of TGF-α by HRCC cells leads to the activation of EGFR on tumor-associated endothelial cells that serve as an essential target for therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Keywords: Kidney cancer, EGFR, tumor endothelium, endothelial apoptosis, antivascular therapy

Introduction

One third of patients with renal cell carcinoma (RCC) present with metastasis on diagnosis and, over the course of the disease, metastasis develops in another 50% of patients [1]. Despite early diagnosis and systemic chemotherapy, the outcome for patients with RCC remains poor, with < 10% of them surviving for 5 years [2]. Clearly, the identification of novel therapeutic targets is urgently needed.

We previously reported that human renal cell carcinoma (HRCC) cells growing in the kidneys or bones of nude mice express epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and phosphorylated EGFR (pEGFR) [3,4]. Systemic therapy with the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor PKI166 [5] (in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy) inhibited the activation of EGFR and was associated with therapy for orthotopically growing HRCC cells [3,4]. We also reported that the expression of pEGFR on tumor cells was constitutive [i.e., independent of the local production of transforming growth factor α (TGF-α)/EGF] [6]. Immunohistochemical (IHC) analyses of tumor tissues revealed that tumor-associated endothelial cells (but not endothelial cells in tumor-free kidneys or bones) also expressed activated EGFR. The activation of EGFR on endothelial cells, however, was only found in tumors producing TGF-α/EGF. Whether the primary target of PKI166 was the EGFR on tumor cells or tumor-associated endothelial cells, or both, was not clear [6].

The growth and survival of all neoplasms are dependent on vascular development. Because the genetic instability of tumor cells is a major cause of failure to eradicate tumors, targeting the tumor vasculature is an attractive alternative. In normal human tissues, endothelial cells are long-lived and recycle every 2 to 3 years, whereas in human tumors, endothelial cells recycle every 30 to 40 days [7]. Clearly, dividing endothelial cells in neoplasms are targets for therapy. The expression of various cytokines, growth factors, and their relevant receptors on tumor cells and organ-specific endothelial cells differs among various organ microenvironments [6,8], and the binding of ligands (i.e., vascular endothelial growth factor, TGF-α. EGF, and platelet-derived growth factor) to their receptors leads to receptor activation, thereby increasing the expression of antiapoptotic proteins and cell survival [6,8–13].

The purpose of this study was to determine whether therapy mediated by the tyrosine kinase inhibitor PKI166 against HRCC cells growing orthotopically in nude mice is directed primarily against activated EGFR on tumor cells or against tumor-associated endothelial cells. Our findings show that the production of TGF-α by HRCC is essential for increasing the expression of EGFR and for its activation on tumor-associated endothelial cells, which are primary targets of PKI166.

Materials and Methods

Kidney Cancer Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

For this study, we used the highly metastatic SN12-PM6 HRCC cell line [14]. DNA sequence analysis identified no EGFR mutations [15,16]. The cells were maintained and cultured as previously described [14]. Cultures were maintained for no longer than 12 weeks after recovery from frozen stocks.

Transfection and Selection of SN12-PM6 Cells Expressing TGF-α

Sense TGF-α expression plasmids were created using a stable mammalian transfection kit from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). The target sequence used was 5′-AGAACCGCTTGCTGCCACTCA-3′. Oligonucleotides corresponding to this sequence with flanking EcoRI (5′)-EcorRI (3′) ends were purchased from Genscript (Piscataway, NJ) and ligated into the pcDNA3/neo expression vector. Constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing. SN12-PM6 tumor cells were plated onto 100-mm dishes at a density of 1 x 106 per dish, and monolayers (60–70% confluent) were transfected using routine transfection procedures [17]. Cells were maintained in G418-selective media and frozen after one to three in vitro passages. Negative controls were transfected with empty vector target sequences and pcDNA3 plasmids with identical conditions. To avoid clonal variations, six TGF-α+ SN12-PM6 (TGF-α) and six TGF-α- SN12-PM6 clones were pooled for in vitro and in vivo studies.

Northern Blot Analysis of TGF-α

Polyadenylated mRNA was extracted from 1 x 108 SN12-PM6 cells growing in culture using a FastTrack mRNA isolation kit (Invitrogen Co., San Diego, CA). mRNA was electrophoresed onto 1% denatured formaldehyde agarose gels, electrotransferred to Gene-Screen nylon membranes (DuPont Co., Boston, MA), and cross-linked with an ultraviolet Stratalinker 1800 (Stratagene) at 120,000 mJ/cm2. Filters were prehybridized with rapid hybridization buffer [30 mmol/sodium chloride, 3 mmol/sodium citrate, and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (wt/vol)] (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) at 65°C for 1 hour. Membranes were then hybridized and probed for TGF-α using a Rediprime random labeling kit (Amersham); the presence of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used to control for loading. The cDNA probe used was a 0.9-kb EcoRI endonuclease cDNA fragment from the PMI-TGF1 plasmid corresponding to the human TGF-α gene [18]. The steadystate expression of TGF-α mRNA transcript was quantified through densitometry of autoradiographs using the Image-Quant software program (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). Each sample measurement was calculated as the ratio of the average areas of specific mRNA transcript to the 1.3-kb GAPDH mRNA transcript in the linear range of the film.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) for TGF-α

Viable cells (5 x 106) were seeded in a 96-well plate. Conditioned medium was removed after 24 hours. The cells were washed with 200 µl of Hanks buffered saline solution (HBSS), and 200 µl of fresh serum-free minimum essential medium was added. Twenty-four hours later, TGF-α in cell-free culture supernatants was determined by ELISA, according to the manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Western Blot Analysis of EGFR and pEGFR

Adherant SN12-PM6 and SN12-PM6 (TGF-α) were cultured in serum-free medium and lysed 24 hours later. EGFR and pEGFR proteins were detected using polyclonal rabbit anti-human EGFR (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or monoclonal antiphosphotyrosine (4G10,1:2000; Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY). Immunoblotting was performed as previously described [19,20].

Detection of EGFR Cell Surface Expression by Flow Cytometry

SN12-PM6 and SN12-PM6 (TGF-α) cells grown under basal conditions were harvested with trypsin and washed twice in fluorescent-activated cell sorter (FACS) buffer [2% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 0.1% sodium azide in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)]. Cells were then incubated with the anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody C225 (1:100 dilution; ImClone Systems Incorporated, Somerville, NJ) in FACS buffer for 1 hour on ice and washed twice with ice-cold PBS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Cells were incubated in the dark with goat anti-human AlexaFluor 488 antibody (1:200 dilution; Invitrogen Co.) in FACS buffer for 1 hour on ice and then washed, resuspended in ice-cold PBS/BSA, and analyzed by FACS. Using Coulter software, the percentage of EGFR+ cells and median fluorescence intensity were determined.

Animals and Orthotopic Implantation of Tumor Cells

Male athymic nude mice (NCI-nu) were purchased from the Animal Production Area of the National Cancer Institute's Frederick Cancer Research and Development Center (Frederick, MD). The mice were housed and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in facilities approved by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care and in accordance with current regulations and standards of the US Department of Agriculture, the US Department of Health and Human Services, and the National Institutes of Health. The mice were used in accordance with institutional guidelines when they were 8 to 12 weeks old. To produce tumors, HRCC cells were harvested from subconfluent cultures by brief exposure to 0.25% trypsin and 0.02% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. Trypsinization was stopped with medium containing 10% FBS, and the cells were washed once in serum-free medium and resuspended in HBSS. Suspensions consisting of single cells with > 90% viability were injected into the renal subcapsule of each mouse, as previously described [14]. The mice were killed when moribund (5 weeks after injections) and subjected to necropsy, as described below.

Treatment of Established Orthotopic TGF-α- and TGF-α+ Human Kidney Cancers

Seven days after the implantation of HRCC cells into the renal subcapsule of nude mice, the mice were randomized into two groups (n = 10): 1) oral vehicle solution for PKI166 (dimethyl sulfoxide/0.5% Tween 80 diluted 1:20 in water), or 2) thrice-weekly (Monday, Wednesday, and Friday) oral administration of 50 mg/kg PKI166 alone.

Necropsy Procedures and Histologic Studies

The mice were killed, and their body weights were recorded. Primary tumors in the kidney were excised, measured, and weighed. For IHC and hematoxylin and eosin staining procedures, part of the primary tumor tissue was fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin. Another part of the tumor was embedded in OCT compound (Miles, Inc., Elkhart, IN), rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -70°C. Kidney tumor volume was analyzed using unpaired Student's t test.

IHC Analysis

Frozen tissues of HRCC cell lines growing in the kidney of nude mice were sectioned (8–10 µm), mounted on positively charged Plus slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), and air-dried for 30 minutes. Sections were fixed in cold acetone for 5 minutes, in 1:1 acetone/chloroform (vol/vol) for 5 minutes, and in acetone for 5 minutes. Sections analyzed for TGF-α were incubated at 4°C for 18 hours with a 1:100 dilution of polyclonal rabbit anti-human TGF-α (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). A positive reaction was visualized by incubating the slides for 1 hour with a 1:200 dilution of AlexaFluor 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at room temperature for 1 hour, avoiding exposure to light. IHC procedures for CD31/PECAM-1 were performed as previously described [21]. Samples were also stained for EGFR and activated EGFR (pEGFR).

Sections analyzed for activated EGFR were pretreated with goat anti-mouse IgG1 F(ab′)2 fragment (1:10 dilution in PBS; Jackson Research Laboratories, West Grove, CA) for 8 to 12 hours before incubation with a primary antibody. The samples were then incubated at 4°C for 18 hours with a 1:200 dilution of polyclonal rabbit anti-human EGFR antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and a 1:200 dilution of monoclonal mouse anti-human antibody for activated EGFR (Chemicon, Temecula, CA). A positive reaction was visualized by incubating the slides for 1 hour with a 1:200 dilution of AlexaFluor 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or AlexaFluor 594-conjugated goat anti-mouse (Molecular Probes) at room temperature for 1 hour, avoiding exposure to light. Fluorescent bleaching was minimized by covering the slides with 90% glycerol and 10% PBS. Sections analyzed for CD31/EGFR and CD31/pEGFR were fixed and washed as described above. IHC procedures were performed as previously described [6]. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase biotin dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay was performed using a commercially available apoptosis detection kit, with modifications as previously described [19,20]. Fluorescent bleaching was minimized by covering the slides with 90% glycerol and 10% PBS. Immunofluorescence microscopy was performed using a x20 objective. The results were analyzed, and images were captured as previously described [19,20].

Quantification and Statistical Analysis of Microvessel Density (MVD)

For the quantification of MVD, 10 random 0.159-mm2 fields at x100 magnification were captured for each tumor, and microvessels were quantified as described previously [22,23]. The quantification of CD31 was determined using unpaired Student's t test.

Result

In Vitro Expression of TGF-α and EGFR and pEGFR

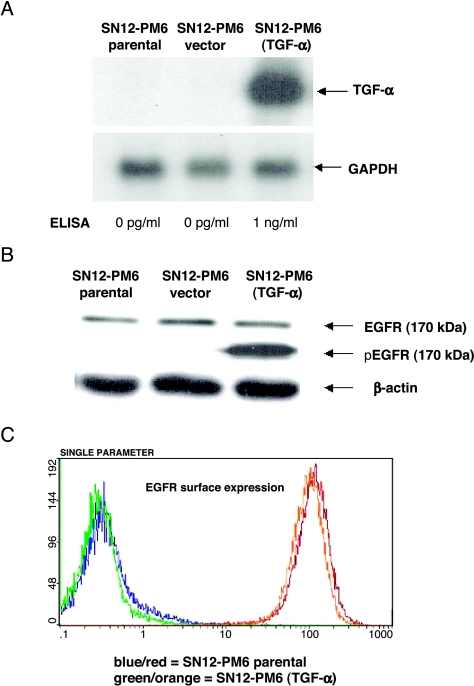

Northern blot analysis (Figure 1A) illustrated that the SN12-PM6 (TGF- ) cell line expressed high levels of TGF-α mRNA, whereas there was an undetectable level of TGF-α mRNA transcript in SN12-PM6 cells and vector control cells. Production of TGF-α by SN12-PM6 (TGF-α) cells, as determined by ELISA, also increased significantly to 1 ng/ml (Figure 1A).

) cell line expressed high levels of TGF-α mRNA, whereas there was an undetectable level of TGF-α mRNA transcript in SN12-PM6 cells and vector control cells. Production of TGF-α by SN12-PM6 (TGF-α) cells, as determined by ELISA, also increased significantly to 1 ng/ml (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

In vitro expression of TGF-α, EGFR, and pEGFR. (A) Northern blot analysis of mRNA for TGF-α in kidney cancer SN12-PM6 and SN12-PM6 (TGF-α) cell lines. GAPDH served as the control for loading. SN12-PM6 (TGF-α) expressed high levels of TGF-α-specific mRNA, whereas SN12-PM6 (parental and empty vectors) did not express detectable levels of TGF-α-specific mRNA. This is one of three representative experiments. Production of TGF-α by SN12-PM6 (TGF-α) cells, as determined by ELISA, significantly increased to 1 ng/ml. (B). Adherent SN12-PM6 and SN12-PM6 (TGF-α) were cultured for 24 hours, and the levels of EGFR protein (170 kDa) and pEGFR (170 kDa) were determined by Western blot analysis. The expression of EGFR did not differ between groups. The activation of pEGFR was dependent on the production of TGF-α. (C) EGFR surface expression, as detected by FACS, illustrated a similar right shift in fluorescent intensity for both SN12-PM6 (blue line) and SN12-PM6 (TGF-α) (green line) cells compared with control cells stained with secondary antibody only (red and orange, respectively).

SN12-PM6 and SN12-PM6 (TGF-α) cells exhibited similar levels of EGFR protein (170-kDa band) (Figure 1B). The expression level of pEGFR (170-kDa band) depended on the sufficient production of TGF-α (Figure 1B). EGFR surface expression detected by flow cytometry (Figure 1C) illustrated a similar right shift in fluorescence intensity for both SN12-PM6 (blue line) and SN12-PM6 (TGF- ) (green line) cells compared with control cells stained with secondary antibody only (red and orange, respectively). The percentage of EGFR+ cells for SN12-PM6 and SN12-PM6 (TGF-α) was 99.8% and 99.9%, respectively. The median fluorescence intensity was 121.1 and 110, respectively.

) (green line) cells compared with control cells stained with secondary antibody only (red and orange, respectively). The percentage of EGFR+ cells for SN12-PM6 and SN12-PM6 (TGF-α) was 99.8% and 99.9%, respectively. The median fluorescence intensity was 121.1 and 110, respectively.

Activation of EGFR on Tumor Cells and Tumor-Associated Endothelial Cells

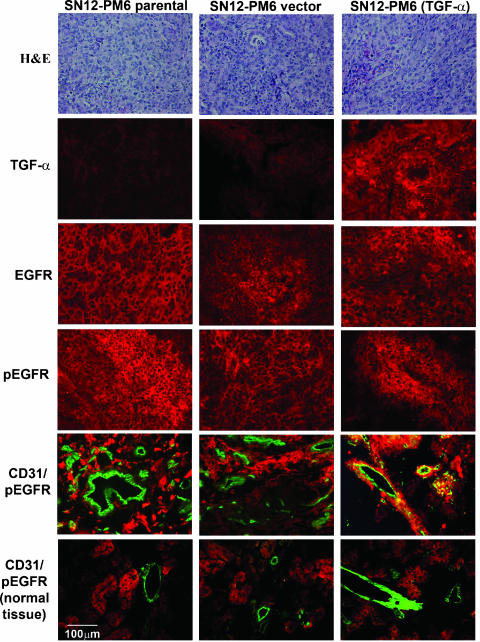

We first determined whether the activation of EGFR on tumor and tumor-associated endothelial cells was dependent on the expression of TGF-α. SN12-PM6 and SN12-PM6 (TGF-α) cells were injected into the kidney of nude mice. Three weeks after injection, the mice were killed. In all of the mice, there was tumor in the kidney. We demonstrated by IHC analyses that only tumors producing TGF-α had endothelial cells expressing activated EGFR (i.e., significant colocalization of CD31 and activated EGFR) (Figure 2). In contrast, endothelial cells in TGF-α- tumors or in adjacent tissues did not express detectable levels of activated EGFR.

Figure 2.

IHC determination of TGF-α, EGFR, activated EGFR, and CD31/pEGFR in kidney cancers growing in the kidney of nude mice. Note the positive staining for CD31/pEGFR only in TGF-α+ tumors. Endothelial cells in TGF-α- tumors or adjacent tissues did not express detectable levels of activated EGFR.

Therapy of TGF-α- and TGF-α+ Kidney Cancer

Next, we evaluated the therapeutic efficacy of the specific EGFR inhibitor PKI166 against SN12-PM6 and SN12-PM6 (TGF-α) cells growing in the kidney of nude mice. Seven days after the implantation of HRCC cells into the kidney, the mice received thrice-weekly oral administration of vehicle alone or thrice-weekly oral administration of 50 mg/kg PKI166. The mice were treated for 4 weeks, killed, and necropsied.

Detailed necropsy revealed that, in all of the mice, there was tumor in the kidney (Table 1). In mice injected with TGF-α- cells, PKI166 (administered orally three times a week at 50 mg/kg) did not decrease the median tumor volume, compared with control (118 and 205 mm3, respectively). In contrast, in mice injected with TGF-α+ cells, treatment with PKI166 significantly decreased the median tumor volume, compared with control (78 and 303 mm3, respectively; P > .001).

Table 1.

Treatment of Orthotopically Implanted Human Kidney SN12-PM6 Parental or SN12-PM6 TGF-α Sense-Transfected Cancer Cells by PKI166.

| Treatment Group* | Tumor Incidence† | Kidney Tumors | Body Weight (g) | ||||

| Tumor Volume (mm3) | Tumor Weight (g) | Median | Range | ||||

| Median | Range | Median | Range | ||||

| SN12-PM6, parental | |||||||

| Saline control | 10/10 | 205 | 141–377 | 0.4 | 0.2–0.5 | 33 | 3–41 |

| PKI166 (50 mg/kg) | 10/10 | 118‡ | 67–242 | 0.2 | 0.2–0.3 | 34 | 30–37 |

| SN12-PM6 TGF-α, sense-transfected | |||||||

| Saline control | 10/10 | 303 | 187–505 | 0.5 | 0.2–0.5 | 33 | 32–34 |

| PKI166 (50 mg/kg) | 10/10 | 78§ | 2–197 | 0.1§ | 0.1–0.3 | 30 | 28–36 |

SN12-PM6 (parental or TGF-α sense-transfected) human kidney cancer cells (1 x 106) were injected into the kidney of nude mice. Seven days later, different groups of mice were treated with vehicle solution or thrice-weekly oral PKI166 (50 mg/kg). All mice were killed on day 35.

Number of positive mice/number of mice injected.

P < .05, compared to controls.

P < .001, compared to controls.

Histologic and IHC Analyses

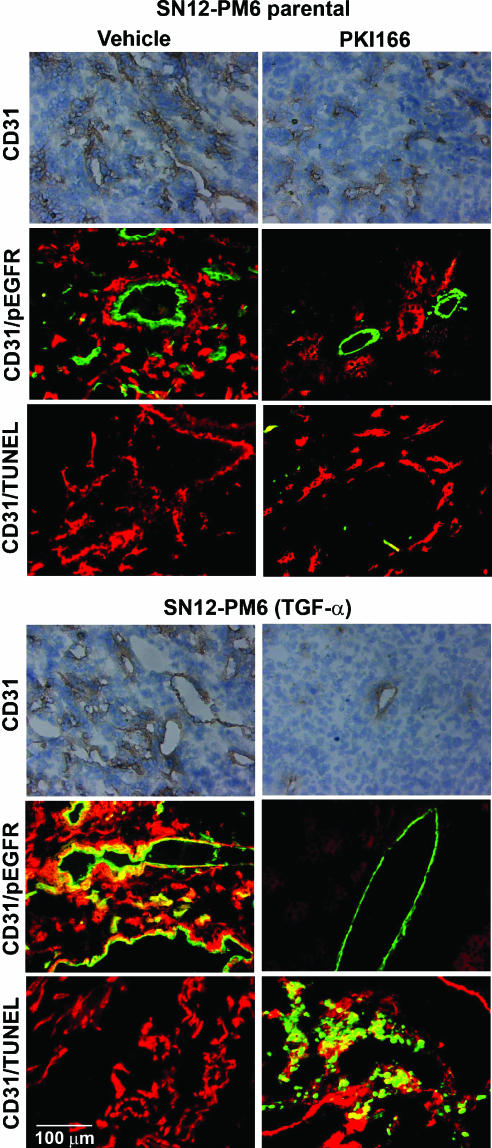

Kidney tumors of mice from different treatment groups were prepared for IHC analysis to determine the expression of TGF-α, EGFR, pEGFR, CD31, and TUNEL The expression of TGF-α did not correlate with the expression of pEGFR on tumor cells. The immunofluorescence double-labeling technique for CD31 and pEGFR revealed that only endothelial cells in TGF-α+ tumors expressed activated EGFR. Treatment with PKI166 inhibited the phosphorylation of EGFR in tumor cells that did or did not express TGF-α. In contrast, inhibition of pEGFR on endothelial cells was found only in TGF-α+ tumors (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

IHC analysis of MVD, activated EGFR, and TUNEL (apoptosis) in kidney tumors from mice treated with vehicle-control or PKI166. Kidney tumors were harvested after 4 weeks of treatment, and sections were stained for CD31/PECAM-1 (brown) or were double-labeled for CD31 (green) and pEGFR (red), or CD31 (red) and TUNEL (green). Only endothelial cells in TGF-α+ tumors expressed activated EGFR. Treatment with PKI166 inhibited the phosphorylation of EGFR in tumor cells that did or did not express TGF-α. Inhibition of pEGFR on endothelial cells was only found in TGF-α+ tumors. Treatment with PKI166 induced endothelial cell apoptosis only in TGF-α+ tumors, which correlated with reduction in MVD.

The MVD in tumors produced by HRCC TGF-α- cells was reduced from 41 ± 11 in control tumors to 22 ± 6 in tumors of mice receiving thrice-weekly oral administration of 50 mg/kg PK1166. Even more striking, the MVD in tumors produced by HRCC TGF-α cells was reduced from 55 ± 9 in control tumors to 4 ± 3 in tumors of mice receiving thrice-weekly oral administration of 50 mg/kg PK1166. In addition, there was a significant decrease in the size of microvessels in tumors produced by both HRCC TGF-α- and TGF-α+ cells and treated with PKI166.

The CD31/TUNEL immunofluorescence double-labeling technique did not detect apoptotic endothelial cells in TGF-α- tumors. However, treatment with PKI166 produced significant apoptosis of endothelial cells in TGF-α+ tumors. This induction of apoptosis correlated with a significant reduction in MVD. Collectively, these data suggest that pEGFR on tumor-associated endothelial cells serves as a major target for therapy by the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor PKI166.

Discussion

Our present results demonstrate that pEGFR on tumor-associated endothelial cells in HRCC is a primary target for therapy by the specific EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor PKI166. Preliminary studies have shown that the expression of activated EGFR by tumor-associated endothelial cells is influenced by local production of TGF-α/EGF [6], which suggests that activated EGFR on tumor-associated endothelial cells, in response to TGF-α/EGF, could be directly targeted by an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor. We confirmed that the activation of EGFR on tumor-associated endothelial cells (but not on endothelial cells in tumor-free kidneys) is indeed dependent on the production of TGF-α by adjacent tumor cells. We showed that TGF-α- kidney tumor cells growing in the kidney of nude mice were relatively resistant to treatment with PKI166. In sharp contrast, PKI166 treatment against TGF-α+ kidney tumors produced a significant decrease in tumor volume. PKI166 inhibited the phosphorylation of EGFR in tumor cells in both TGF-α+ and TGF-α- tumors. However, inhibition of EGFR phosphorylation on endothelial cells was found only in TGF-α+ tumors.

In recently reported clinical trials of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors, an overall modest activity has been demonstrated, and detailed analysis has concluded that the content of EGFR on tumor cells does not determine response. Most recently, in studies of Iressa [24,25], responses in human tumors and in human cell lines have been associated with EGFR levels ranging from very low to very high [26–31]. One implication of these data is that EGFR content does not reflect the level of receptor activation. Furthermore, clinical trials of the EGFR inhibitor Iressa in lung cancer were originally based on the rationale that many such cancers have high levels of EGFR protein. In early trials, however, little correlation was found between the response of individual cancers and the levels of EGFR protein in lung cancer [32,33]. More recent studies have suggested that most lung cancers responding to Iressa have somatic activating mutations in the EGFR gene [15,16], whereas in lung cancers that did not respond to Iressa, the frequency of such EGFR mutations was much lower. In our current study, DNA sequence analysis identified no EGFR mutations in HRCC cells.

The studies cited above have focused their attention on the content and the level of EGFR (total and activated) in tumor cells. The possibility that tumor-associated endothelial cells are targets of protein tyrosine kinase inhibitors of the EGFR has been overlooked. Thus, based on our current findings, we suggest that the clinical use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors specific to EGFR will be more effective against neoplasms that express high levels of TGF-α. In these tumors, both tumor cells and tumor-associated endothelial cells can express activated EGFR (i.e., targets for therapy). Our current studies warrant future investigation of key signaling/survival pathways that are activated in the vasculature (as well as in tumor cells) in response to TGF-α and of the effect of EGFR inhibition on these key proteins/pathways. In summary, destruction of tumor-associated endothelial cells leads to apoptosis of surrounding tumor cells and to enhanced cancer therapy.

Acknowledgements

We thank Fahao Zhang for technical support, and Arminda Martinez and Donna Schade for help in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported, in part, by Cancer Center Support Core Grant CA16672 and grant 74-600118 from the Gillson Longenbaugh Foundation.

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Russo P. Renal cell carcinoma: presentation, staging, and surgical treatment. Semin Oncol. 2000;27:160–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartmann JT, Bokemeyer C. Chemotherapy for renal cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:1541–1544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber KL, Doucet M, Price JE, Baker CH, Kim SJ, Fidler IJ. Blockade of the epidermal growth factor receptor signaling leads to inhibition of renal cell carcinoma growth in the bone of nude mice. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2940–2947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kedar D, Baker CH, Killion JJ, Dinney CPN, Fidler IJ. Blockade of the epidermal growth factor receptor signaling inhibits angiogenesis leading to the regression of human renal cell carcinoma growing orthotopically in nude mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3592–3600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Traxler P, Buchdunger E, Furet P, Gschwind H-P, Ho P, Mett H. Preclinical profile of PKI166—a novel and potent EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor for clinical development. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:3750. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker CH, Kedar D, McCarty MF, Tsan R, Weber KL, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ. Blockade of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling on tumor cells and tumor-associated endothelial cells for therapy of human carcinomas. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:929–938. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64253-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eberhard A, Kahlert S, Goede V, Hemmerlein B, Plate KH, Augustine HG. Heterogeneity of angiogenesis and blood vessel maturation in human tumors: implications for antiangiogenic tumor therapies. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1388–1393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langley RR, Ramirez KM, Tsan RZ, Van Arsdall M, Nilsson MB, Fidler IJ. Tissue-specific microvascular endothelial cell lines from H-2K(b)-tsA58 mice for studies of angiogenesis and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2971–2976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langley RR, Fan D, Tsan RZ, Rebhun R, He J, Kim SJ, Fidler IJ. Activation of the platelet-derived growth factor-receptor enhances survival of murine bone endothelial cells. Cancer Res. 2004;11:3727–3730. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim SJ, Uehara H, Karashima T, Shepherd DL, Killion JJ, Fidler IJ. Blockade of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling in tumor cells and tumor-associated endothelial cells for therapy of androgen-independent human prostate cancer growing in the bone of nude mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;3:1200–1210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bancroft CC, Chen Z, Yeh J, Sunwoo JB, Yeh NT, Jackson S, Jackson C, Van Waes C. Effects of pharmacologic antagonists of epidermal growth factor receptor, PI3K and MEK signal kinases on NF-kappaB and AP-1 activation and IL-8 and VEGF expression in human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma lines. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:538–548. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirata A, Ogawa S, Kometani T, Kuwano T, Naito S, Kuwano M, Ono M. ZD 1839 (Iressa) induces antiangiogenic effects through inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2554–2560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirata A, Uehara H, Izumi K, Naito S, Kuwano M, Ono M. Direct inhibition of EGF receptor activation in vascular endothelial cells by gefitinib (“Iressa,” ZD 1839) Cancer Sci. 2004;95:614–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb02496.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naito S, Walker SM, Fidler IJ. In vivo selection of human renal cell carcinoma cells with high metastatic potential in nude mice. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1989;7:381–389. doi: 10.1007/BF01753659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paez JG, Janne PA, Lee JC, Tracy S, Greulich H, Gabriel S, Herman P, Kaye FJ, Lindeman N, Boggon TJ, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to Gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, Gurubhagavatula S, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, Harris PL, Haserlat SM, Supko JG, Haluska FG, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to Gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inoue K, Slaton JW, Kim SK, Perrotte P, Eve BY, Bar-Eli M, Radinsky R, Dinney CP. Interleukin 8 expression regulates tumori-genicity and metastasis in human bladder cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2290–2299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clarke R, Brunner N, Katz D, Glanz P, Dickson RB, Lippman ME, Kern FG. The effects of a constitutive expression of transforming growth factor-α on the growth of MCF-7 human breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Mol Endocrinol. 1989;3:372–380. doi: 10.1210/mend-3-2-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruns CJ, Solorzano CC, Harbison MT, Ozawa S, Tsan R, Fan D, Abbruzzese J, Traxler P, Buchdunger E, Radinsky R, et al. Blockade of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling by a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor leads to apoptosis of endothelial cells and therapy of human pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2926–2935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solorzano CC, Baker CH, Tsan R, Traxler P, Cohen P, Buchdunger E, Killion JJ, Fidler IJ. Optimization for the blockade of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling for therapy of human pancreatic carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2563–2572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rak J, Filmus J, Kerbel RS. Reciprocal paracrine interactions between tumor cells and endothelial cells: the “angiogenesis progression” hypothesis. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:2438–2450. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(96)00396-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoneda T, Kuniyasu H, Crispens MA, Price JE, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ. Expression of angiogenesis-related genes and progression of human ovarian carcinomas in nude mice. J Natl Cancer Inst (Bethesda) 1998;90:447–454. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.6.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radinsky R, Risin S, Fan D, Dong Z, Bielenberg D, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ. Level and function of epidermal growth factor receptor predict the metastatic potential of human colon carcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1:19–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albanell J, Rojo F, Averbuch S, Feyereislova A, Mascaro JM, Herbst R, LoRusso P, Rischin D, Sauleda S, Gee J, et al. Pharmacodynamic studies of the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor ZD1839 in skin from cancer patients: histopathologic and molecular consequences of receptor inhibition. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:110–124. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baselga J, Rischin D, Ranson M, Calvert H, Raymond E, Kieback DG, Kaye SB, Gianni L, Harris A, Bjork T, et al. Phase I safety, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic trial of ZD1839, a selective oral epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with five selected solid tumor types. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4292–4302. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.03.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sirotnak FM, Zakowski MF, Miller VA, Scher HI, Kris MG. Efficacy of cytotoxic agents against human tumor xenografts is markedly enhanced by coadministration of ZD1839 (Iressa), an inhibitor of EGFR tyrosine kinase. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:4885–4892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ciardiello F, Caputo R, Bianco R, Damiano V, Pomatico G, De Placido S, Bianco AR, Tortora G. Antitumor effect and potentiation of cytotoxic drugs activity in human cancer cells by ZD-1839 (Iressa), an epidermal growth factor receptor-selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2053–2063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saltz L, Rubin M, Hochster H, Tchekmeydian NS, Waksal H, Needle M. Cetuximab (IMC-225) plus irinotecan (CPT-11) is active in CPT-11-refractory colorectal cancer that expresses epidermal growth factor receptors. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2001;20:3. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moasser MM, Basso A, Averbuch SD, Rosen N. The tyrosine kinase inhibitor ZD1839 (“Iressa”) inhibits HER2-driven signaling and suppresses the growth of HER2-overexpressing tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7184–7188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moulder SL, Yakes FM, Muthuswamy SK, Bianco R, Simpson JF, Arteaga CL. Epidermal growth factor receptor (HER1) tyrosine kinase inhibitor (Iressa) inhibits HER2/neu (erbB2)-overexpressing breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8887–8895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arteaga CL, Baselga J. Clinical trial design and end points for epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted therapies: implications for drug development and practice. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1579–1589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giaccone G, Herbst RS, Manegold C, Scagliotti G, Rosell R, Miller V, Natale RB, Schiller JH, VonPawel J, Pluzanska A, et al. Gefitinib in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced nonsmall-cell lung cancer: a phase III trial—INTACT 1. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:777–784. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herbst RS, Giaccone G, Schiller JH, Natale RB, Miller V, Manegold C, Scagliotti G, Rosell R, Oliff I, Reeves JA, et al. Gefitinib in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III trial—INTACT 2. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:785–794. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]