Abstract

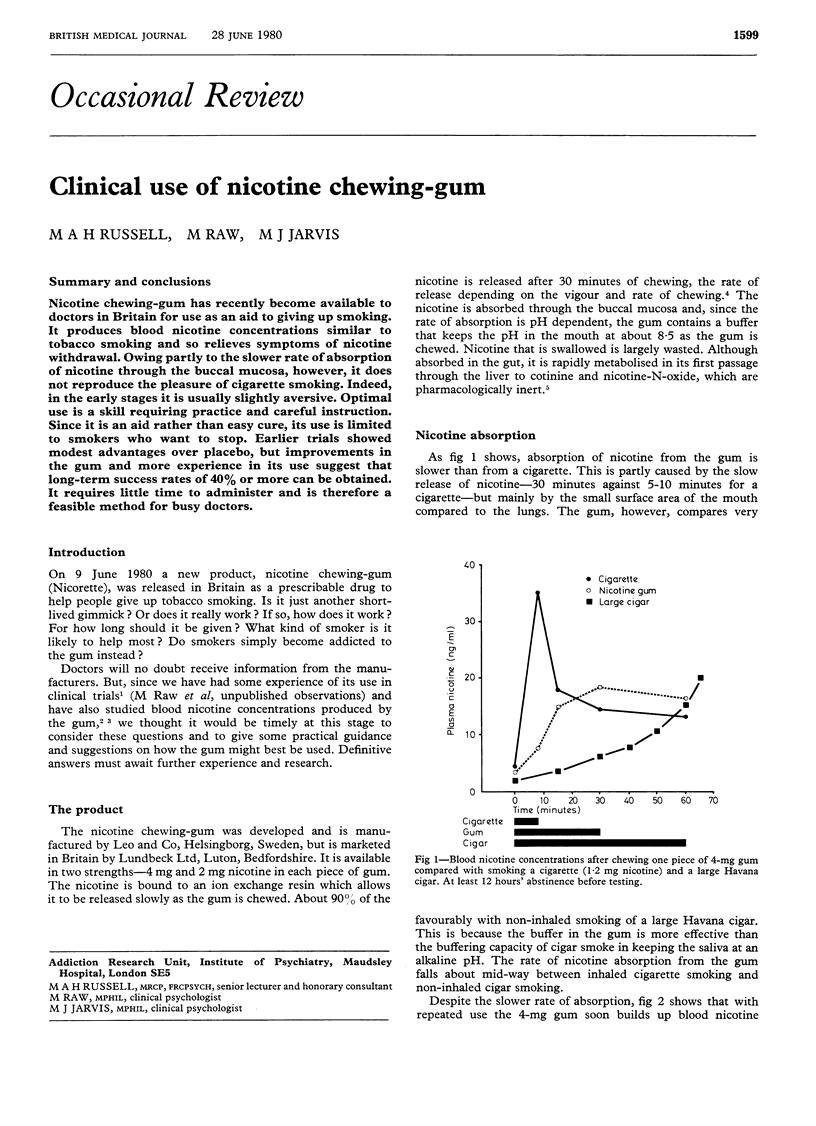

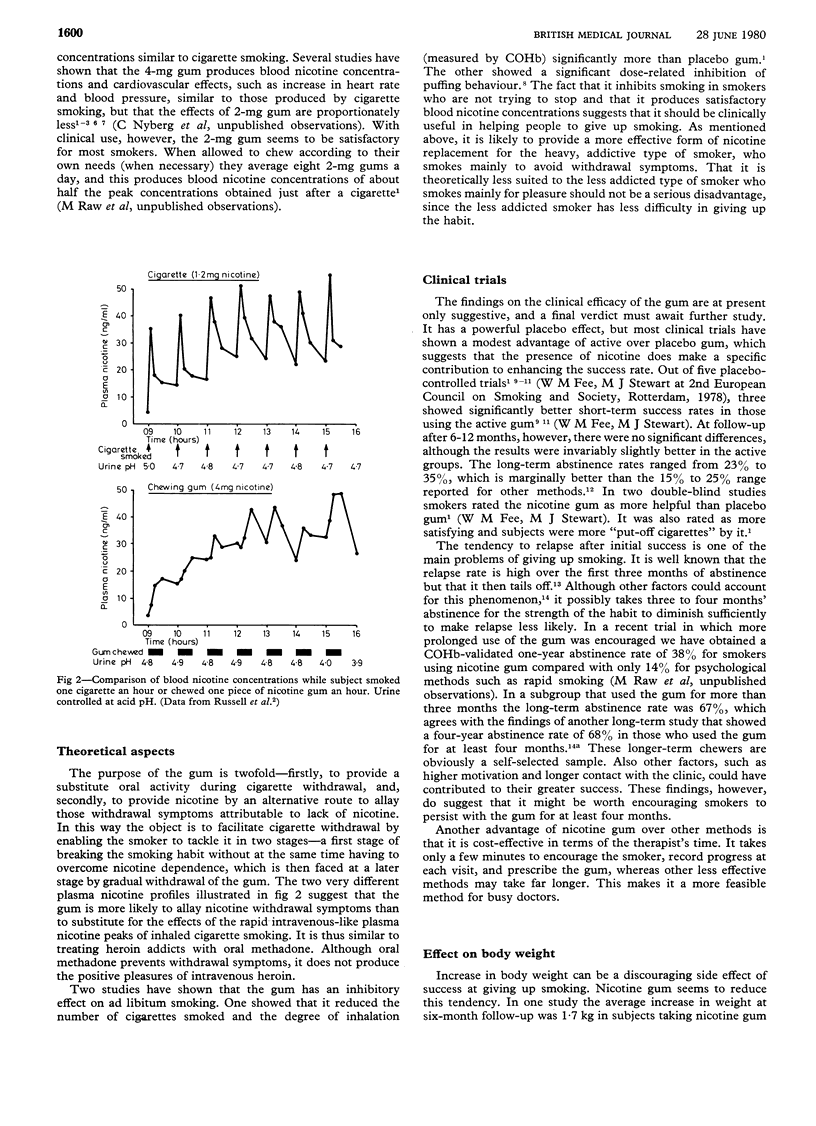

Nicotine chewing-gum has recently become available to doctors in Britain for use as an aid to giving up smoking. It produces blood nicotine concentrations similar to tobacco smoking and so relieves symptoms of nicotine withdrawal. Owing partly to the slower rate of absorption of nicotine through the buccal mucosa, however, it does not reproduce the pleasure of cigarette smoking. Indeed, in the early stages it is usually slightly aversive. Optimal use in a skill requiring practice and careful instruction. Since it is an aid rather than easy cure, its use is limited to smokers who want to stop. Earlier trials showed modest advantages over placebo, but improvements in the gum and more experience in its use suggest that long-term success rates of 40% or more can be obtained. It required little time to administer and is therefore a feasible method for busy doctors.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Brantmark B., Ohlin P., Westling H. Nicotine-containing chewing gum as an anti-smoking aid. Psychopharmacologia. 1973 Jul 19;31(3):191–200. doi: 10.1007/BF00422509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernö O. A substitute for tobacco smoking. Psychopharmacologia. 1973 Jul 19;31(3):201–204. doi: 10.1007/BF00422510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt W. A., Bespalec D. A. An evaluation of current methods of modifying smoking behavior. J Clin Psychol. 1974 Oct;30(4):431–438. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(197410)30:4<431::aid-jclp2270300402>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski L. T., Jarvik M. E., Gritz E. R. Nicotine regulation and cigarette smoking. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1975 Jan;17(1):93–97. doi: 10.1002/cpt197517193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puska P., Bjorkqvist S., Koskela K. Nicotine-containing chewing gum in smoking cessation: a double blind trial with half year follow-up. Addict Behav. 1979;4(2):141–146. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(79)90048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M. A., Feyerabend C. Cigarette smoking: a dependence on high-nicotine boli. Drug Metab Rev. 1978;8(1):29–57. doi: 10.3109/03602537808993776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M. A., Feyerabend C., Cole P. V. Plasma nicotine levels after cigarette smoking and chewing nicotine gum. Br Med J. 1976 May 1;1(6017):1043–1046. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6017.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M. A., Jarvis M., Iyer R., Feyerabend C. Relation of nicotine yield of cigarettes to blood nicotine concentrations in smokers. Br Med J. 1980 Apr 5;280(6219):972–976. doi: 10.1136/bmj.280.6219.972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M. A., Sutton S. R., Feyerabend C., Cole P. V., Saloojee Y. Nicotine chewing gum as a substitute for smoking. Br Med J. 1977 Apr 23;1(6068):1060–1063. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6068.1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M. A., Wilson C., Feyerabend C., Cole P. V. Effect of nicotine chewing gum on smoking behaviour and as an aid to cigarette withdrawal. Br Med J. 1976 Aug 14;2(6032):391–393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6032.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton S. R. Interpreting relapse curves. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1979 Feb;47(1):96–98. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]