Abstract

Objective:

First, to analyze the strategy for 184 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma seen and treated at a single interdisciplinary hepatobiliary center during a 10-year period. Second, to compare long-term outcome in patients undergoing surgical or palliative treatment, and third to evaluate the role of photodynamic therapy in this concept.

Summary Background Data:

Tumor resection is attainable in a minority of patients (<30%). When resection is not possible, radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy have been found to be an ineffective palliative option. Recently, photodynamic therapy (PDT) has been evaluated as a palliative and neoadjuvant modality.

Methods:

Treatment and outcome data of 184 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma were analyzed prospectively between 1994 and 2004. Sixty patients underwent resection (8 after neoadjuvant PDT); 68 had PDT in addition to stenting and 56 had stenting alone.

Results:

The 30-day death rate after resection was 8.3%. Major complications occurred in 52%. The overall 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates were 69%, 30%, and 22%, respectively. R0, R1, and R2 resection resulted in 5-year survival rates of 27%, 10%, and 0%, respectively. Multivariate analysis identified R0 resection (P < 0.01), grading (P < 0.05), and on the limit to significance venous invasion (P = 0.06) as independent prognostic factors for survival. PDT and stenting resulted in longer median survival (12 vs. 6.4 months, P < 0.01), lower serum bilirubin levels (P < 0.05), and higher Karnofsky performance status (P < 0.01) as compared with stenting alone. Median survival after PDT and stenting, but not after stenting alone, did not differ from that after both R1 and R2 resection.

Conclusion:

Only complete tumor resection, including hepatic resection, enables long-term survival for patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Palliative PDT and subsequent stenting resulted in longer survival than stenting alone and has a similar survival time compared with incomplete R1 and R2 resection. However, these improvements in palliative treatment by PDT will not change the concept of an aggressive resectional approach.

R0 resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma resulted in a 5-year survival rate of 27%. Palliative photodynamic therapy (PDT) and stenting resulted in longer median survival than stenting alone. Median survival after PDT and stenting, but not after stenting alone, did not differ from that after both R1 and R2 resection.

Relevant clinical experience in managing hilar cholangiocarcinoma has been limited to a few referral centers. Fewer than 30% of patients are suitable for formally curative resection (R0 resection).1 Standard treatment of patients with unresectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma is biliary drainage. Chemotherapy for advanced biliary tract cancer has not been proved to prolong survival significantly.2 Likewise, in a prospective analysis, radiation had no effect on survival among resected and palliated patients with perihilar cholangiocarcinoma.3 Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has recently been described as a technically feasible method for the treatment of nonresectable cholangiocarcinoma.4–7 In a randomized prospective study, including our group, palliative treatment with PDT and subsequent stenting led to improvement of survival, quality of life, and cholestasis compared with endoscopic stenting alone.8 Preliminary data of a prospective single-arm phase II study from our center using PDT in a neoadjuvant setting showed effective selective tumor destruction before surgery.9

This report analyzes 184 consecutive patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma seen and treated at a single interdisciplinary hepatobiliary institution during a 10-year period. This is the first study that provides results and comparison of resectional and nonresectional therapy for patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma in one center. The studies by Jarnagin et al1 and Nakeeb et al10,11 also analyzed staging and resectability of all patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma seen in one center, but the outcome data focused on the results of resectional surgery. This report, comprising the largest published series of PDT for hilar cholangiocarcinoma, also evaluates the efficacy and role of PDT in the concept of available treatment modalities based on previous reports from our group.6,8,9,12,13

METHODS

Patients

From January 01, 1994, through May 31, 2004, 194 consecutive patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma were evaluated and treated. Seven patients could not be analyzed because of missing follow-up data and 3 patients died of septic complications during diagnostic workup. Thus, 184 patients remained for outcome analysis. Clinical, radiologic, histopathologic, therapy, and survival data were entered prospectively.

Pretreatment Workup

Transabdominal duplex ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT), and endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) were performed in all 184 patients. Magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC)/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), intraductal ultrasonography (IDUS), 18-FDG positron emission tomography (PET), and percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) were applied in 154, 63, 52, and 36 patients, respectively. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) was carried out in 25 patients in whom vascular involvement was suspected. The location and longitudinal extent of the tumor, according to the modified Bismuth-Corlette classification,14 were assessed by ERC as standard method and definitively classified after resection by the surgeon. The depth of tumor infiltration was measured routinely by CT and MRI and facultatively by IDUS. Biopsies from the tumor were taken during ERC in 101 patients. The tumors of all patients were clinically staged according to the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC)15 classification system. Resectable tumors were pathohistologically classified after surgery. The tumors of the patients who were treated before 2003 were clinically and pathohistologically converted to the current UICC 2002 classification system.15

Evaluation for Treatment

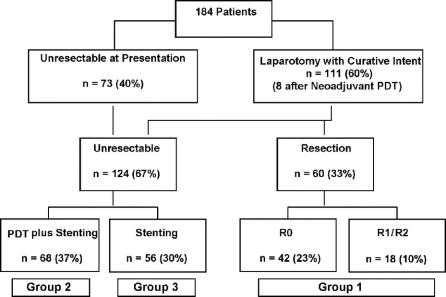

Locoregional tumor resectability was defined according to the criteria of Vauhtey et al16 and Burke et al17 and definitively assessed by one surgeon and one gastroenterologist. The distribution of patients by treatment is summarized in Figure 1. A total of 111 patients (60%) considered to have potentially resectable tumors underwent surgical exploration. Eight out of these patients were treated with neoadjuvant PDT followed by surgery as described previously.9 Sixty patients underwent resection. The standard palliative treatment was endoscopic or percutaneous stenting. Between 1996 and 1999, 23 patients with unresectable tumors were treated with PDT and subsequent biliary stenting in a prospective single-arm phase II trial.6,13 Encouraged by the beneficial effect of PDT observed in this phase II trial and other uncontrolled studies5,7,18 15 patients with unresectable disease were enrolled in a prospective randomized multicenter study comparing stenting alone with PDT in addition to stenting (PDT plus stenting, n = 8; stenting alone, n = 7).8 Based on the results of this trial showing superiority of PDT and stenting compared with simple stenting treatment, a further 37 patients underwent PDT plus stenting. Overall, 60 patients underwent resection (group 1), 68 had PDT plus stenting (group 2), and 56 had stenting only (group 3). Out of group 1, one patient received radiation therapy (49 Gy), another patient chemotherapy, and a third patient chemoradiation (45 Gy) when recurrence occurred. In group 2, chemotherapy and chemoradiation (45 Gy) was administered in 6 and 2 patients, respectively. In group 3, 5 patients received chemotherapy and 1 patient had 145Iridium implants placed via transhepatic biliary stent.

FIGURE 1. Distribution of patients by treatment depending on pretherapeutic workup and surgical findings. PDT, photodynamic therapy; R0, curative resection; R1, microscopic infiltration of the resection and dissection margins; R2, evidence of gross residual disease.

Surgery

The surgical procedures comprised right-sided hemihepatectomy (segments 5–8; n = 20), right trisegmentectomy (segments 4–8; n = 17), left hemihepatectomy (segments 2–4; n = 15), hilar resection alone (n = 7), and liver transplantation (n = 1). Hilar resection alone with curative intent was performed in 4 patients with Bismuth-Corlette type I and II carcinoma and high risk of postoperative liver failure and in 3 patients with Bismuth-Corlette type IIIb carcinoma, treated in the first 2 years of the study. Four patients with liver resection and 1 patient with hilar resection alone underwent additional Kausch-Whipple partial pancreatoduodenectomy. In 1 patient with advanced Bismuth-Corlette type IV tumor, liver transplantation and partial pancreatoduodenectomy were performed, as has been described by Neuhaus et al.19 The caudate lobe (segment 1) was resected in 20 patients (33%) with tumors involving the left hepatic duct. In 11 patients (18%), resection of the portal vein bifurcation and in 2 patients (3%) resection of the hepatic artery was performed. Biliary-enteric reconstruction was done with a Roux-en-Y jejunum segment. Transhepatic stents were placed across the anastomosis and removed 4 to 6 weeks after surgery. Preoperative portal vein embolization was not used. All resections were performed by 3 experienced surgeons.

Biliary Drainage

Stenting was not performed in patients with potentially resectable tumors without a history of cholangitis, bilirubin level <10 mg/dL, and surgery within approximately 10 days. Cholangitis was defined according to the criteria of Csendes et al.20 When stenting was indicated in patients with potentially resectable tumors, in principle, unilateral biliary decompression of the future remnant liver lobe was performed. In patients with nonresectable tumors, at least two, 9-, or 11.5-Fr plastic endoprostheses were placed above the main strictures. Successful drainage after technically successful stenting was defined as a decrease in bilirubin level >50% 3 months after stent insertion. In the palliatively treated patients, stents were exchanged every 3 months as recommended by Prat et al.21 According to this concept, 155 patients received biliary drainage during the first diagnostic workup, 85 of them in the referring institution. Stenting was not performed in 29 patients prior to laparotomy, 6 of whom finally underwent resection.

Photodynamic Therapy

As described previously,6 the photosensitizing drug sodium porfimer (2 mg/kg body weight; Photofrin, Axcan Pharma Inc., Mount-Saint-Hilaire, Canada), was injected intravenously and photoactivation was performed after 1 to 4 days. Local response had been defined as when more than 50% of occluded segmental bile ducts were found to be reopened, stable local disease when less than 50% of occluded ducts had been reopened, and progressive local disease when segmental duct occlusions or total length of stenosis had progressed by more than 25%.6 Palliative PDT was repeated if any follow-up examination showed evidence of local tumor progression. In the neoadjuvant group, PDT was followed by surgery after a median period of 3.4 weeks (range, 2.4–10.0 weeks) except for 1 patient who underwent combined liver transplantation and Kausch-Whipple pancreatoduodenectomy 308 days after PDT. Informed consent was obtained from all patients undergoing PDT. The PDT study protocols of the 2 phase II6,9 and the phase III8 trials had been approved by the Ethics Committee at the University of Leipzig.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical calculations were performed using SPSS, version 10.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Numeric data were presented as median with range or as mean value with standard error of the mean (SEM). Intergroup comparisons were performed with the Student t test and the Mann-Whitney U test. Patient survival rates were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by means of the log-rank test. For the survival rates, all deaths related and unrelated to surgery were included. Cox regression was used to determine independent predictors of outcome, using survival as the dependent variable and factors significant (P < 0.05) on univariate analysis as covariates. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics and Resectability

The pretreatment clinical characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. At presentation, the disease of 73 patients was judged to be unresectable on the basis of imaging data (Fig. 1). Thirty-four patients presented locally advanced disease with tumors extending bilaterally to secondary hepatic duct radicles (n = 32) or extensive portal vein/hepatic artery invasion (n = 2). Ten patients had distant metastases (liver, peritoneum, lymph nodes, lung) and 29 patients were considered unfit for a major operation. At laparotomy, a further 51 patients were judged to be unresectable due to locally advanced disease (n = 10), extensive involvement of the portal vein bifurcation (n = 3), hepatic artery invasion (n = 1), gross lymph node metastases at the common hepatic artery and the celiac trunk level (n = 6), peritoneal metastases (n = 8), liver metastases (n = 2), liver cirrhosis (n = 8), or a combination of the above (n = 13). Overall, the most common reason for unresectability was locally advanced disease (n = 54; 44%).

TABLE 1. Pretreatment Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population

Resection (Group 1)

Operative Morbidity and Mortality

Major complications occurred in 31 of 60 patients (52%) and required relaparotomy in 22 patients (37%). The most common complication was bile leakage (n = 8). Hepatic failure rate was higher in patients with right trisegmentectomy than in those who underwent minor resections (18% vs. 5%, not significant). The 30- and 60-day death rates were 8.3% (n = 5) and 11.7% (n = 7), respectively. The most common cause of death was multiple organ failure because of infective complications (n = 4), followed by liver failure (n = 2) and heart failure (n = 1).

Biliary Drainage

Hemihepatic biliary drainage of only the future remnant liver lobe was performed in 20 patients, and both liver lobes were drained in 34 patients. In 34 patients (63%), biliary drainage resulted in a decrease of bilirubin level >50%. Median preoperative (day before surgery) bilirubin levels in patients with and without biliary drainage were 2.1 mg/dL (range, 0.3–36.1 mg/dL) and 1.5 mg/dL (range, 0.4–6.6 mg/dL), respectively. The corresponding postoperative levels (5th postoperative day) were 2.8 mg/dL (range, 0.3–21.9 mg/dL) and 1.8 mg/dL (range, 0.4–4.5 mg/dL), respectively. In the subgroup of patients with neoadjuvant PDT, the median pretreatment, preoperative, and postoperative serum bilirubin levels were 10.5 mg/dL (range, 0.5–34.9 mg/dL), 1.4 mg/dL (range, 0.3–3.6 mg/dL), and 1.3 mg/dL (range, 0.8–12.0 mg/dL), respectively. Of the postoperative 60-day deaths, 6 patients died in the drainage group (n = 54) and 1 patient in the nondrainage group (n = 6).

Histopathology

All resected specimens were confirmed as adenocarcinomas. In 42 of 60 patients (70%), curative (R0) resection was achieved, including 7 of 8 patients with neoadjuvant PDT. Microscopic infiltration of the resection and/or dissection margins (R1 resection) was found in 11 patients (18%). The remaining 7 patients (12%) had gross residual disease (R2 resection). Metastases in regional lymph nodes were observed in tumors of 15 patients (25%), and 53 patients (88%) had well or moderately differentiated tumors. Postoperatively, UICC IA, IB, IIA, IIB, III, and IV tumor stages had 2, 11, 30, 12, 3, and 2 patients, respectively.

Survival and Recurrence

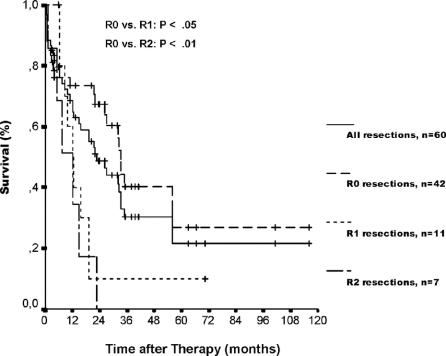

Median follow-up time of patients who underwent resection was 19.3 months (range, 0.9–116.7 months). The survival rates, including postoperative deaths, according to the residual tumor status are depicted in Figure 2. Overall 1-, 3-, and 5-year actuarial survival rates, including postoperative deaths, were 69%, 30%, and 22%, respectively, with a median survival of 22.8 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 14.6–31.0). Curative (R0) resection (n = 42), including postoperative deaths, resulted in 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates of 73%, 40%, and 27%, respectively. The corresponding 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates without postoperative deaths were 86%, 57%, and 31%, respectively. Neoadjuvant PDT before surgery resulted in 1-, 3-, and 5-year actuarial survival rates of 88%, 42%, and 42% as compared with 66%, 28%, and 19% after surgery alone (not significant).

FIGURE 2. Actuarial patient survival after resection (group 1), including postoperative deaths, stratified by residual tumor status. Median survival time was 33.1 months (95% CI, 31.2–34.9), 12.2 months (95% CI, 7.7–16.7), and 12.2 months (95% CI, 4.4–20.0) after R0, R1, and R2 resection, respectively (P < 0.05, R0 vs. R1; P < 0.01, R0 vs. R2). Individual patients still alive during follow-up are indicated by marks on the curves.

At the time of this analysis, in 27 patients (51%), excluding 60-day postoperative deaths, recurrent tumor was observed. Fourteen patients (52%) had recurrent tumor at the former resection line, 5 patients (19%) distant metastases, and 8 patients (29%) both. Univariate and multivariate analysis of 12 clinicopathological parameters revealed that residual tumor status and grading were the only independent predictors of outcome (Table 2).

TABLE 2. Resection Group: Univariate and Multivariate Analysis of Factors Associated With Survival

Palliative Treatment (Groups 2 and 3)

The pretreatment clinical characteristics did not differ between the PDT and stenting group (group 2) and the stenting alone group (group 3) (Table 1).

Histology and Procedures

At the initial diagnostic workup, histopathologic examination of biopsies confirmed adenocarcinomas in 36 patients (29%) (Table 1). During follow-up, diagnosis of adenocarcinoma was confirmed by histology in further 32 patients (26%). The median number of endoscopic procedures was 6 (range, 1–19) in group 2, including a median number of 2 (range, 1–6) PDT treatments. The patients in group 3 required a median number of 2 (range, 1–15) endoscopic procedures. Because of duodenal tumor obstruction, 6 patients in group 2 and 2 patients in group 3 underwent duodenal stent insertion (Wallstent Enteral; Boston Scientific Microvasive, Natick, MA).

Response to Treatment

According to the definition in Methods, local response rates after the first, second, third, and fourth photodynamic laser therapy in the PDT plus stenting group were 75%, 70%, 58%, and 50%, respectively. Stable local disease was observed in 25%, 23%, 37% and 30%, respectively. Both PDT plus stenting and stenting alone resulted in a decrease of mean serum bilirubin levels relative to baseline 3 months after the first treatment. However, the decrease was significant only in the PDT plus stenting group (P < 0.001) and mean bilirubin concentration revealed lower levels in group 2 as compared with group 3 (4.1 mg/dL vs. 7.3 mg/dL, P < 0.05). Successful drainage (decrease of bilirubin levels >50% after 3 months) was achieved in 75% of patients in group 2 and in 39% of patients in group 3 despite the higher percentage of Bismuth-Corlette type IV tumors in group 2 (78% vs. 54%). Pretreatment median body mass index did not differ between group 2 and group 3 (24.3 kg/m2 vs. 25.4 kg/m2) and remained stable in patients of both groups surviving 3 to 24 months. Median pretreatment Karnofsky performance status improved by 2.3% in group 2 and showed a decrease of 8.3% in group 3 at 3 months after the first treatment (P < 0.01, group 2 vs. group 3).

Adverse Events

Stenting- and PDT-associated mortality was not observed. Eight patients (12%) in the PDT group suffered from skin phototoxicity grade I to II. Stenting-related complications occurred in 5 patients (pancreatitis, n = 2; bleeding, n = 2; perforation, n = 1). Bacterial cholangitis was observed in 38 patients (56%) of group 2 and in 32 patients (57%) of group 3 (not significant).

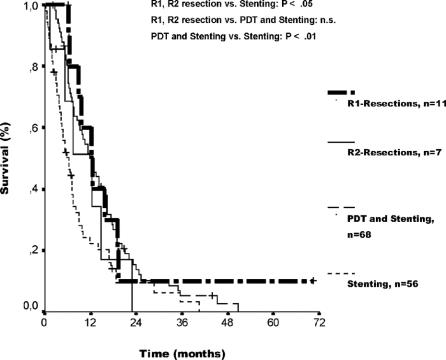

Survival Time and Causes of Death

Median follow-up time was 11.5 months (range, 2.1–50.8 months) for group 2 and 5.4 months (range, 0.3–40.5 months) for group 3. One- and two-year actuarial survival rates were 51% and 16% after treatment with PDT plus stenting and 23% and 10% after stenting alone. Median survival time was 12.0 months (95% CI, 8.8–15.3) for group 2 as compared with 6.4 months (95% CI, 4.2–8.5) for group 3 (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3). The median survival of patients with and without histologically proven adenocarcinoma did not differ within group 2 (12.0 vs. 9.9 months, P = 0.94) and within group 3 (5.3 vs. 7.0 months, P = 0.71). One patient each in group 2 and 3 with a histologically confirmed diagnosis had a history of primary sclerosing cholangitis. At the end of this analysis, 63 patients of group 2 and 51 patients of group 3 had died. The most frequent causes of death in the 2 groups were tumor progression (n = 45 [71%], group 2; n = 37 [73%], group 3) and complications of chronic cholangitis (n = 16 [25%], group 2; n = 12 [24%], group 3).

FIGURE 3. Actuarial patient survival comparing R1/R2 resection and palliative treatment. Median survival was longer after both R1 (12.2 months, 95% CI, 7.7–16.7) and R2 resection (12.2 months, 95% CI, 4.4–20.0) in comparison to stenting alone (6.4 months, 95% CI, 4.2–8.5) (P < 0.05, R1, R2 resection vs. stenting alone). Median survival did not differ between R1 and R2 resection and PDT plus stenting. Median survival time was longer after PDT plus stenting than after stenting alone (P < 0.01). Individual patients still alive during follow-up are indicated by marks on the curves.

Resection Versus Palliative Treatment

Median survival, including treatment-related deaths, of the group of patients who underwent resection (group 1: 22.8 months, 95% CI, 14.6–31.0) was longer than of those patients who underwent nonresectional treatment (group 2: 12.0 months, 95% CI, 8.8–15.3; group 3: 6.4 months, 95% CI, 4.2–8.5) (P < 0.001, group 1 vs. group 2 and group 3). Furthermore, median survival was longer after both R1 (12.2 months, 95% CI, 7.7–16.7) and R2 resection (12.2 months, 95% CI, 4.4–20.0) in comparison to group 3 with stenting alone (P < 0.05, R1 and R2 resection vs. group 3). However, there was no significant difference in median survival between both R1 and R2 resection and group 2 with PDT plus stenting (Fig. 3). At the time of this analysis, the actual 3-year survival rates according to therapy and including treatment-related deaths were as follows: R0 resection, 45% (9 of 20 patients at risk); R1 resection, 13% (1 of 8 patients at risk); R2 resection, 0% (0 of 4 patients at risk); PDT plus stenting, 7% (3 of 43 patients at risk); stenting alone, 3% (1 of 38 patients at risk). Actual 5-year survivors were observed only after R0 resection (4 of 14 patients at risk) and R1 resection (1 of 5 patients at risk) but not after R2 resection (0 of 3 patients at risk), PDT plus stenting (0 of 26 patients at risk), and stenting alone (0 of 22 patients at risk). Of the 5 actual 5-year-survivors, 3 had liver resection, 1 had liver transplantation, and 1 had hilar resection. Two of these 5 patients, including the 1 with R1 resection, developed a tumor recurrence 54 and 33 months after surgery. The overall median hospital stay amounted to 47.5 days (range, 9–165 days) or 17% (range, 1%–100%) of the follow-up period in group 1, 65 days (range, 3–197 days) or 31% (range, 3%–96%) in group 2, and 44 days (range, 7–207 days) or 40% (range, 3%–100%) in group 3.

DISCUSSION

This study presents analysis and results of resectional and palliative treatment of all patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma referred to the surgical and gastroenterological unit of one center during a 10-year period. The resectability rate was 33% in the present series as compared with 36% and 24% in the studies by Jarnagin et al1,22 and Nakeeb et al,11 both comprising surgically and palliatively treated patients. This report represents the largest published series of PDT of unresectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma. It focuses on comparing survival after resection and palliative treatment modalities. The data from the present series show that survival after PDT added to placement of stents is prolonged compared with stenting alone and comparable to that of patients who underwent incomplete R1–R2 resection.

Resection

Despite nonconclusive data with respect to preoperative biliary drainage, the authors of the majority of recent studies dealing with hilar cholangiocarcinoma recommend biliary drainage to decrease the serum bilirubin level below 2 to 5 mg/dL before resection.23–30 We performed preoperative biliary drainage according to these criteria and obtained a median preoperative bilirubin level of 2.1 mg/dL. Recovery of hepatic function after biliary decompression takes about 4 weeks, so that surgery should be done not too early.25

High complication rates ranging from 14% to 85% were observed in this study and in the literature and were dominated by infective complications and bile leaks.1,19,22,24–35 The high relaparotomy rate of 37% in the present study is based on the fact that we were very stringent with the indication for relaparotomy in patients with severe intraabdominal complications. The in-hospital mortality rates from 7.5% to 18% in studies, which included at least 40 patients and used an aggressive resectional approach,1,19,22,26–36 are consistent with the data of this study. In these series, liver failure was the cause of death in 25% to 100%.1,19,26,30–33,35 However, there are 2 recent series with 0%24,25 and one report with 1.3%23 in-hospital mortality. In all 3 of these studies that were performed in Japan, routinely preoperative biliary drainage was performed to reduce bilirubin levels below 2 mg/dL and portal vein embolization depending on the remnant hepatic lobar volume.23–25 Using this procedure, no liver failure was observed in these studies23–25 and the delay before surgery resulting from the need for preoperative treatment was not detrimental to survival.25 In contrast, the most recent series of Jarnagin et al22 showed an operative mortality rate of 2.9% during the time period 2000 to 2003 without the use of portal vein embolization and routine biliary drainage.

Of 13 studies, residual tumor stage proved to be an independent prognostic factor in 11 series, including the present series,1,19,22,23,26,28,30,31,36,37 and showed prognostic significance on the basis of univariate analysis in 2 reports.25,29 Further, clear superiority of curative (R0) resection to incomplete R1 and R2 resection was documented in multiple recent reports1,23,26,27,30,31,36 and was observed in this series. However, in the study reported by Seyama et al,25 no difference in survival was seen between R0 resection with a margin <5 mm and R1 resection.

Consistent with the present series, all reports, except for 2 studies,25,30 revealed grading as significant prognostic factor in multivariate1,19,22,24,26,28,29,37 or univariate analysis.36 All 5 long-term survivors in the present series and all 32 5-year survivors in the study by Klempnauer et al38 had well- or moderately differentiated tumors.

The frequency of lymph node metastases ranged from 21% to more than 50% in previous reports1,19,22–26,28,30,33,35 and was 25% in this series. There are studies in which regional lymph node metastases did not influence survival, including our series,1,24,30,35 and on the other hand reports confirming lymph node status as an independent prognostic factor.11,23,25,26,28,29,33,36 This difference can be partly explained by more extensive lymphadenectomy in the studies that show an impact of lymph node status on survival.23,25,28,33

A decisive argument in favor of resectional surgery of hilar cholangiocarcinoma is a percentage of actual long-term survival up to 20%.1,22,23,28,29,33,38 Five-year actuarial survival rates, including operative deaths and R0, R1, and R2 resections, ranged between 22% and 32% in 10 studies and in the present series.1,19,26–28,31,33–36 According to these criteria, only 3 reports documented higher 5-year survival rates of 34%,11 35%30 (with adjuvant radiochemotherapy after R1 resection), and 40%,25 respectively. The 5-year survival of 42% in the small subgroup of neoadjuvant PDT in the present study remains to be proved in the future. Calculating only R0 resections and including operative deaths, 5-year survival rates between 27% and 51.6% were reported.23,26,27,30,31,35

Palliative Treatment

The median survival time of patients with nonresectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma is approximately 3 months without intervention39 and 4 to 10 months with biliary drainage.22,23,30,31,39–43 Because surgical drainage procedures do not reveal any advantage to nonsurgical palliation,26,31 biliary stenting is regarded as the palliative method of choice. Despite controversial data with respect to the benefit of unilateral or bilateral biliary drainage,40,43–46 in this report all palliatively treated patients were drained bilaterally by at least 2 endoprostheses. In recent studies, successful endoscopic drainage rate with plastic stents was 41% (20% reduction of bilirubin within the first week),42 53% (30% reduction of bilirubin within the first week),41 74% (30% reduction of bilirubin within the first month),47 and 80% (30% reduction of bilirubin within the first month),43 respectively. The randomized study by Ortner et al,8 which contained 79% Bismuth type IV tumors, showed a decrease of cholestasis by at least 50% within the first week in only 21% with stenting alone. In all prospective trials5–8,48 and in the present series, palliative PDT led to a relevant reduction of cholestasis to bilirubin levels, ranging from 1.4 to 6.0 mg/dL. The better relief of obstructive cholestasis by PDT as compared with stenting alone contributes substantially to the survival benefit of these patients. Four prospective single-arm studies,5,7,13,48 one randomized trial,8 and the present series comprising 150 PDT treated patients demonstrated that PDT in addition to stenting results in a relevant prolongation of median survival in the range of 9.3 to 16.3 months after diagnosis. Since the local response rate remained at 50% even after the fourth PDT retreatment, the authors consider more than one PDT necessary to manage the multiple intrahepatic biliary strictures. The more effective improvement of cholestasis after PDT as compared with stenting alone resulted in a significant better Karnofsky performance status after PDT in this nonrandomized analysis and in the randomized study by Ortner et al.8 Moreover, in this series, quality of life was improved by a shorter hospital stay relative to overall survival after PDT as compared with stenting alone. The diagnosis of adenocarcinoma was confirmed histologically in 55%, which is in accordance with other studies.49–52 A few patients out of the group without histologically confirmed adenocarcinoma may have benign fibrosing disease despite comparable survival time. In the near future, the recently described methods of digital imaging analysis,53 fluorescence in situ hybridization,54 and analysis of p16INK4a and p14ARF methylation for bile duct fluids may further improve the sensitivity of diagnosis.55

Comparison of Resection Versus Palliative Treatment

The clear superiority of curative (R0) resection over palliative endoprosthesis placement is confirmed in this series as well as in other studies.1,31,36 As found in our analysis, even resection with a histologically positive margin offers a survival benefit as compared with palliative treatment in most reports,23,26,30,31 except for the study by Jarnagin et al.1 We report the first prospective, uncontrolled trial in patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma which compared outcome after palliative PDT and resectional therapy. As expected, survival after palliative PDT was inferior to R0 resection. However, patients treated with PDT showed a similar survival time to that of patients with incomplete R1–R2 resection, although the former were more ill. Despite these improvements in palliative treatment by PDT, an aggressive resectional approach is justified in view of the facts that even during surgery completeness of tumor resection can hardly be defined and long-term survival is observed after complete resection of advanced tumor stages22,25,26,28,31,33,38 and even after R1 resection.19,23,28,30,38 Because of limitations of current diagnostic tools, laparotomy is indicated in any patients except for those with distant metastases, poor general condition, or obviously locally advanced tumor. New preoperative staging systems for prediction of resectability should be considered, such as the proposed T-staging of Jarnagin et al,1 which is based on the extent of ductal involvement and the presence of portal vein invasion and/or hepatic lobar atrophy.

CONCLUSION

Approximately one third of patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma present with resectable disease. Only complete tumor resection, including hepatic resection, enables long-term survival of patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Neoadjuvant selective tumor destruction with PDT is feasible and safe. Comparable survival time of patients treated with PDT and subsequent stenting and those who underwent incomplete R1 and R2 resection will not change the therapeutic strategy of an aggressive resectional approach. Optimum control of cholestasis and cholangitis by palliative PDT will render those patients suitable for other antitumor therapies.

Footnotes

Reprints: Helmut Witzigmann, MD, Department of Surgery II, University of Leipzig, Liebigstrasse 20a, 04103 Leipzig, Germany. E-mail: Helmut.Witzigmann@medizin.uni-leipzig.de.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jarnagin WR, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, et al. Staging, resectability, and outcome in 225 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2001;234:507–517; discussion 517–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Khan SA, Davidson BR, Goldin R, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cholangiocarcinoma: consensus document. Gut. 2002;51(suppl 6):VI1–VI9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pitt HA, Nakeeb A, Abrams RA, et al. Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: postoperative radiotherapy does not improve survival. Ann Surg. 1995;221:788–797; discussion 797–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.McCaughan JS Jr, Mertens BF, Cho C, et al. Photodynamic therapy to treat tumors of the extrahepatic biliary ducts: a case report. Arch Surg. 1991;126:111–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ortner MA, Liebetruth J, Schreiber S, et al. Photodynamic therapy of nonresectable cholangiocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:536–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berr F, Wiedmann M, Tannapfel A, et al. Photodynamic therapy for advanced bile duct cancer: evidence for improved palliation and extended survival. Hepatology. 2000;31:291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rumalla A, Baron TH, Wang KK, et al. Endoscopic application of photodynamic therapy for cholangiocarcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:500–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ortner MEJ, Caca K, Berr F, et al. Successful photodynamic therapy for nonresectable cholangiocarcinoma: a randomized prospective study. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1355–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiedmann M, Caca K, Berr F, et al. Neoadjuvant photodynamic therapy as a new approach to treating hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a phase II pilot study. Cancer. 2003;97:2783–2790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Sohn TA, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma: a spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors. Ann Surg. 1996;224:463–473; discussion 473–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Nakeeb A, Tran KQ, Black MJ, et al. Improved survival in resected biliary malignancies. Surgery. 2002;132:555–563; discission 563–564. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Berr F, Tannapfel A, Lamesch P, et al. Neoadjuvant photodynamic therapy before curative resection of proximal bile duct carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2000;32:352–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiedmann M, Berr F, Schiefke I, et al. Photodynamic therapy in patients with non-resectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma: 5-year follow-up of a prospective phase II study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bismuth H, Corlette MB. Intrahepatic cholangioenteric anastomosis in carcinoma of the hilus of the liver. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1975;140:170–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sobin LH, Wittekind C, eds. UICC: TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors, 6th ed. New York: Wiley-Liss, 2002:74–85. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vauthey JN, Blumgart LH. Recent advances in the management of cholangiocarcinomas. Semin Liver Dis. 1994;14:109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burke EC, Jarnagin WR, Hochwald SN, et al. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: patterns of spread, the importance of hepatic resection for curative operation, and a presurgical clinical staging system. Ann Surg. 1998;228:385–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zoepf T, Jakobs R, Arnold JC, et al. Photodynamic therapy for palliation of nonresectable bile duct cancer: preliminary results with a new diode laser system. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2093–2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neuhaus P, Jonas S, Bechstein WO, et al. Extended resections for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 1999;230:808–818; discussion 819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Csendes A, Diaz JC, Burdiles P, et al. Risk factors and classification of acute suppurative cholangitis. Br J Surg. 1992;79:655–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prat F, Chapat O, Ducot B, et al. A randomized trial of endoscopic drainage methods for inoperable malignant strictures of the common bile duct. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jarnagin WR, Bowne W, Klimstra DS, et al. Papillary phenotype confers improved survival after resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2005;241:703–712; discussion 712–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Kawasaki S, Imamura H, Kobayashi A, et al. Results of surgical resection for patients with hilar bile duct cancer: application of extended hepatectomy after biliary drainage and hemihepatic portal vein embolization. Ann Surg. 2003;238:84–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kondo S, Hirano S, Ambo Y, et al. Forty consecutive resections of hilar cholangiocarcinoma with no postoperative mortality and no positive ductal margins: results of a prospective study. Ann Surg. 2004;240:95–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seyama Y, Kubota K, Sano K, et al. Long-term outcome of extended hemihepatectomy for hilar bile duct cancer with no mortality and high survival rate. Ann Surg. 2003;238:73–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kosuge T, Yamamoto J, Shimada K, et al. Improved surgical results for hilar cholangiocarcinoma with procedures including major hepatic resection. Ann Surg. 1999;230:663–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyazaki M, Ito H, Nakagawa K, et al. Aggressive surgical approaches to hilar cholangiocarcinoma: hepatic or local resection? Surgery. 1998;123:131–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Todoroki T, Kawamoto T, Koike N, et al. Radical resection of hilar bile duct carcinoma and predictors of survival. Br J Surg. 2000;87:306–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ebata T, Nagino M, Kamiya J, et al. Hepatectomy with portal vein resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: audit of 52 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2003;238:720–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hemming AW, Reed AI, Fujita S, et al. Surgical management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2005;241:693–699; discussion 699–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Pichlmayr R, Weimann A, Klempnauer J, et al. Surgical treatment in proximal bile duct cancer: a single-center experience. Ann Surg. 1996;224:628–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerhards MF, van Gulik TM, de Wit LT, et al. Evaluation of morbidity and mortality after resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma-a single center experience. Surgery. 2000;127:395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kitagawa Y, Nagino M, Kamiya J, et al. Lymph node metastasis from hilar cholangiocarcinoma: audit of 110 patients who underwent regional and paraaortic node dissection. Ann Surg. 2001;233:385–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.IJitsma A, Appeltans BM, de Jong KP, et al. Extrahepatic bile duct resection in combination with liver resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a report of 42 cases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:686–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Capussotti L, Muratore A, Polastri R, et al. Liver resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: in-hospital mortality and long term survival. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;195:641–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klempnauer J, Ridder GJ, von Wasielewski R, et al. Resectional surgery of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:947–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tojima Y, Nagino M, Ebata T, et al. Immunohistochemically demonstrated lymph node micrometastasis and prognosis in patients with otherwise node-negative hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2003;237:201–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klempnauer J, Ridder GJ, Werner M, et al. What constitutes long-term survival after surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma? Cancer. 1997;79:26–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farley DR, Weaver AL, Nagorney DM. ‘Natural history' of unresected cholangiocarcinoma: patient outcome after noncurative intervention. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:425–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deviere J, Baize M, de Toeuf J, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with hilar malignant stricture treated by endoscopic internal biliary drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 1988;34:95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ducreux M, Liguory C, Lefebvre JF, et al. Management of malignant hilar biliary obstruction by endoscopy: results and prognostic factors. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:778–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu CL, Lo CM, Lai EC, et al. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic endoprosthesis insertion in patients with Klatskin tumors. Arch Surg. 1998;133:293–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Polydorou AA, Cairns SR, Dowsett JF, et al. Palliation of proximal malignant biliary obstruction by endoscopic endoprosthesis insertion. Gut. 1991;32:685–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Palma GD, Galloro G, Siciliano S, et al. Unilateral versus bilateral endoscopic hepatic duct drainage in patients with malignant hilar biliary obstruction: results of a prospective, randomized, and controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:547–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Palma GD, Pezzullo A, Rega M, et al. Unilateral placement of metallic stents for malignant hilar obstruction: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:50–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang WH, Kortan P, Haber GB. Outcome in patients with bifurcation tumors who undergo unilateral versus bilateral hepatic duct drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:354–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Polydorou AA, Chisholm EM, Romanos AA, et al. A comparison of right versus left hepatic duct endoprosthesis insertion in malignant hilar biliary obstruction. Endoscopy. 1989;21:266–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dumoulin FL, Gerhardt T, Fuchs S, et al. Phase II study of photodynamic therapy and metal stent as palliative treatment for nonresectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:860–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schoefl R, Haefner M, Wrba F, et al. Forceps biopsy and brush cytology during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for the diagnosis of biliary stenoses. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:363–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sugiyama M, Atomi Y, Wada N, et al. Endoscopic transpapillary bile duct biopsy without sphincterotomy for diagnosing biliary strictures: a prospective comparative study with bile and brush cytology. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:465–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pugliese V, Conio M, Nicolo G, et al. Endoscopic retrograde forceps biopsy and brush cytology of biliary strictures: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:520–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kubota Y, Takaoka M, Tani K, et al. Endoscopic transpapillary biopsy for diagnosis of patients with pancreaticobiliary ductal strictures. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1700–1704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baron TH, Harewood GC, Rumalla A, et al. A prospective comparison of digital image analysis and routine cytology for the identification of malignancy in biliary tract strictures. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:214–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kipp BR, Stadheim LM, Halling SA, et al. A comparison of routine cytology and fluorescence in situ hybridization for the detection of malignant bile duct strictures. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1675–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Klump B, Hsieh CJ, Dette S, et al. Promoter methylation of INK4a/ARF as detected in bile-significance for the differential diagnosis in biliary disease. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1773–1778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]