Abstract

Objective:

Review of available literature on the topic of breast reconstruction and radiation is presented. Factors influencing the decision-making process in breast reconstruction are analyzed. New trends of immediate breast reconstruction are presented.

Summary Background Data:

New indications for postmastectomy radiation have caused a dramatic increase in the number of radiated patients presenting for breast reconstruction. The major studies and their impact on breast cancer management practice are analyzed. Unsatisfactory results of conventional immediate reconstruction techniques followed by radiotherapy led to a new treatment algorithm for these patients. If the need for postoperative radiation therapy is known, a delayed reconstruction should be considered. When an immediate reconstruction is still desired despite the certainty of postoperative radiotherapy, reconstructive options should be based on tissue characteristics and blood supply. Autologous tissue reconstruction options should be given a priority in an order reflecting superiority of vascularity and resistance to radiation: latissimus dorsi flap, free TRAM or pedicled TRAM without any contralateral components of tissue, pedicled TRAM/midabdominal TRAM, and perforator flap.

Conclusions:

When the indications for postoperative radiotherapy are unknown, premastectomy sentinel node biopsy, delayed-immediate reconstruction, or delayed reconstruction is preferable.

An increasing population of postmastectomy patients is indicated for postoperative radiation therapy. Complications caused by radiation are best avoided with delayed breast reconstruction. Does the new trend in breast cancer management mean an end of immediate breast reconstruction?

The role of radiation therapy in the treatment of breast cancer is dramatically changing. Breast-conserving therapy has been used in an increasing proportion of patients with early-stage disease beginning in the 1980s. At the same time as breast-conserving therapy was reducing the number of mastectomies, the use of postmastectomy irradiation was decreasing due to the perception that it did not improve survival.1–8 During this period, perhaps partly due to the example set by breast-conserving therapy, plastic surgeons began offering immediate breast reconstruction (instead of delayed reconstruction) to patients. This trend allowed the development of the “skin-sparing” mastectomy with immediate autologous breast reconstruction, which clearly improved the long-term esthetic results of reconstruction without increased number of operations or complications.9,10 However, since about 1990, there has been a resurgence in the use of postmastectomy radiotherapy due to the results of randomized trials demonstrating survival benefits for patients with positive axillary nodes. These findings were summarized in guidelines published by American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO).11 Plastic surgeons therefore face the challenge of integrating radiotherapy and breast reconstruction to an increasing number of breast cancer patients.

This article will review the interaction of radiotherapy and reconstructive surgical procedures following either breast-conserving surgery or mastectomy. In addition, we propose an approach to the management of patients considering mastectomy in an effort to optimize their choice of reconstructive procedure and outcome.

Reconstruction and Breast-Conserving Therapy

Local Recurrence After Breast-Conserving Therapy

The success of breast-conserving therapy (confirmed by the NSABP-B06 trial and other studies, showing survival rates equal to that of patients treated with mastectomy) set the stage for partial mastectomy followed by radiation to become the preferred treatment of stage I and II invasive breast cancer.12–17 With current patient selection rules (which require uninvolved margins and an acceptable esthetic result) and treatment techniques, the risk of ipsilateral breast cancer recurrence is 1% or less per year.18

Complication Rates and Cosmetic Results of Breast-Conserving Therapy

The reported complication rates of breast conservation procedures are low (between 2 and 9%) and include breast necrosis and fibrosis, arm edema, decreased range of motion, pneumonitis, brachial plexus pain and paresis, fat necrosis, and rib fracture.19,20 Almost half of the complications are related to the accompanying axillary dissection, rather than to breast surgery or radiotherapy.

Cosmetic results tend to decline markedly for the first 3 years after treatment but then progress at a very slow rate.21 The cosmetic results of breast-conserving treatment performed today are superior to those performed in the past, especially when only the breast is treated and chemotherapy is not used. For example, in a series of 157 such patients treated at the Joint Center for Radiation Therapy (JCRT), Boston, from 1982 to 1985, cosmetic results 3 years after radiotherapy were scored by the treating physician as “excellent” (essentially the same appearance as the contralateral breast) in 75% of patients and “good” (minimal but identifiable effects of treatment) in 23%. Only 2% of patients had unacceptable cosmetic results.22

A number of factors clearly influence the effect of radiotherapy on reconstruction outcomes. Cosmesis decreases with increasing doses of radiation.23–27 Greater breast size has been associated with increased retraction after radiotherapy, but this problem can be largely overcome by the use of higher photon energies.28 The amount of tissue resected appears to be the most important factor responsible for cosmetic outcome. In patients treated at the JCRT from 1982 to 1985, the only factors significantly affecting the cosmetic outcome were the volume of surgical resection and the use of chemotherapy, especially when given concurrently with radiotherapy.22 Lumpectomy in the lateral quadrants causes less distortion than in medial quadrants. Even a sizable lumpectomy may be less obvious in large breast.

The impact of other aspects of surgery on the cosmetic outcome has not been well studied. For example, many general surgeons do not reapproximate the breast tissue after performing a lumpectomy. These parenchymal defects are left to fill with serous fluid and may slowly contract over a period of several weeks. In general, plastic surgeons in the United States are not involved in the closure of these wounds, and their potential expertise for local tissue rearrangement is absent.

Correction of Cosmetic Defects of Breast-Conserving Therapy

Unfavorable esthetic outcomes are probably underreported. While most patients and general surgeons rank their results as excellent or good, consulting plastic surgeons seem to be much more critical in their evaluation of the cosmetic result. The disparity can be substantial (80% vs. 50% of patients considered to have an acceptable result in a study by Matory et al29).

Plastic surgeons usually see patients treated with breast-conserving therapy due to complaints of asymmetry, volume discrepancy, or breast inframammary fold or nipple-areola complex dislocation. Such patients often complain of other radiation side effects, such as pain, hyperpigmentation, and the presence of telangiectasias.

Some surgeons have performed immediate reconstructions at the time of performing very wide excisions.30–33 However, most groups have abandoned performing immediate reconstruction of partial mastectomy defects because the margins are not known at the time of operation, and hence some patients may go on to require mastectomy. For patients who later become dissatisfied with their results due to excessive tissue loss from excision, the defect can often be repaired following radiotherapy treatment using myocutaneous flaps.34–36 However, the use of such flaps reduces the patient's options in future if they develop a recurrence. Further, patients often do not want to suffer the loss of function with sacrifice of a major muscle, such as the rectus abdominis or latissimus dorsi. The use of silicone implants to replace lost tissue has also been described; however, these prostheses can interfere with visualization of recurrent or new lesions on mammogram.

Additionally, there is a high rate of complications and poor cosmetic results in patients receiving postoperative radiotherapy due mostly to periprosthetic fibrosis and subsequent distortion of breast contour.37

Reconstructive Surgery After Local Recurrence/Salvage Mastectomy

Many patients treated with mastectomy for local failure following breast-conserving therapy desire breast reconstruction. Immediate reconstruction with a myocutaneous flap at the time of mastectomy is psychologically advantageous and also promotes tissue healing in the previously irradiated field.38–40 Since the results of reconstruction in radiated patients appear similar to those treated with initial mastectomy, the results in patients requiring such salvage treatment are included in the section below.

Reconstruction and Postmastectomy Radiation Therapy

Indications for Postmastectomy Radiotherapy

Following the milestone publications in 1997 in the New England Journal of Medicine of randomized trials performed in Denmark41 and British Columbia studies,42 the use of postmastectomy radiation has been increasing. There are at least 18 randomized studies containing more than 6300 patients which have compared systemic therapy to systemic therapy plus postmastectomy radiotherapy in (predominantly) node-positive patients treated with modified radical mastectomy.11,43 All trials showed that postmastectomy radiotherapy substantially reduced the risk of local-regional failure (by roughly two thirds to three fourths, proportionally). The chance of observing a benefit in relapse-free and overall survival rates appeared related to trial size. In the 10 studies with fewer than 200 evaluated patients (which contained a total of 1132 evaluated patients), sometimes the control arm fared better, sometimes the radiotherapy arm did. Eight of the 9 trials containing 200 or more patients (which together contained 5214 evaluated patients) showed trends favoring the radiotherapy arm, with absolute improvements of 2% to 17% in recurrence-free and 2% to 11% in overall survival rates in the irradiated cohort. Only 3 trials (the Danish Breast Cancer Group trials 82b41 and 82c44 and the British Columbia trial45) showed statistically significant improvements in the overall survival rate for the combined-modality arm. However, the power of the trials to show that such differences as were observed were statistically significant was limited, as only 2 of them contained more than 1000 patients. A meta-analysis using published data from these trials showed that postmastectomy radiotherapy reduced overall mortality, with an odds ratio of 0.83 (95% confidence interval, 0.74–0.94, P = 0.004).46

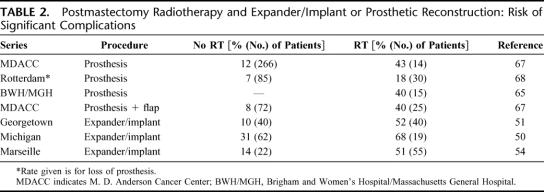

A number of groups, such as ASCO, have promulgated guidelines for the use of postmastectomy radiotherapy.11 Nearly all such guidelines agree that patients with tumors larger than 5 cm, those with “locally advanced” (T3–T4) cancers, and those with 4 or more positive axillary nodes should be irradiated. However, there is substantial controversy regarding whether other patient subgroups (such as those with tumors smaller than 5 cm and 1–3 positive axillary nodes, or patients receiving “neoadjuvant,” or preoperative, chemotherapy) benefit sufficiently from postmastectomy radiotherapy that it should be used routinely. These “gray zones” are a subject to institutional or personal policies, and certainly are of great interest for a reconstructive surgeon. (The guidelines currently used by one of the coauthors [A.R.], which do not reflect ASCO policy, are given in Table 1.)

TABLE 1. Indications for Postmastectomy Radiotherapy

Since it is the pathologic status of lymph nodes that determines the need for postoperative radiotherapy, it is clear that this is the key information that plastic surgeons need to know. One way to overcome this problem may be to use sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) prior to mastectomy. By definition, the sentinel node(s) is the first node or nodes to which lymph drainage and metastasis from breast cancer occurs. Usually, this node is in axillary level I or II, but these nodes can also be subpectoral, infraclavicular, supraclavicular, or even intrapectoral or an internal mammary node. With adequate training and experience, SLNB has been proven to be comparable in accuracy to conventional axillary dissection for patients with T1–T2 breast cancer. In a series from the Memorial-Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, the false-negative rate was 11% (5 of 47) when looking at all cases operated on; however, when each surgeon's first 6 cases were eliminated, the rate dropped to 5% and, when each surgeon's first 15 cases were eliminated to 2%.47 Thus, if a sentinel node biopsy is negative, the chance of recommending postmastectomy radiotherapy based on findings that can be known only after mastectomy (eg, margin status) is likely to be very low. (There is a substantial debate about the prognostic value of micrometastasis of 0.2–2 mm size or submicrometastasis smaller than 0.2 mm, detected by the polymerase chain reaction or immunohistochemistry, but until resolved this issue cannot be part of the decision making process.)

Breast Reconstruction and Preoperative Versus Postoperative Radiation

Expander/Implant Sequence

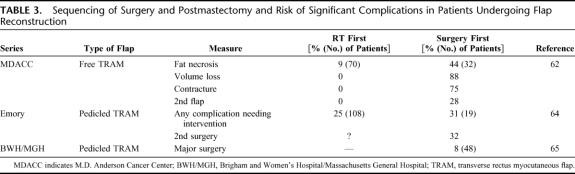

The risk of complications has been shown to increase substantially when patients undergo reconstruction using a tissue expander and implant or implant alone and radiation.48–50 (Some examples of these results are listed in Table 2.) Spear and Onyewu40 recently found that, of 40 patients treated from 1990 to 1998 who underwent staged breast reconstruction with an expander and implant and received radiation before, during, or after the expansion, 47.5% required an additional flap procedure to improve, correct, or salvage the implant. The overall complication rate was 52.5%, compared with 10% of a control group of 40 patients who did not undergo irradiation who were randomly sampled from 200 such patients treated during the same period. They found that the risk of complications and need for salvage using a transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap (TRAM) or latissimus flap was the same whether the expander reconstruction was performed before, during, or after radiotherapy.

TABLE 2. Postmastectomy Radiotherapy and Expander/Implant or Prosthetic Reconstruction: Risk of Significant Complications

Other investigators have also reported that submuscularly placed tissue expanders are poorly tolerated by patients initially undergoing breast-conserving therapy.51–54 A study from Marseille, France found complications occurred in 5 of 8 patients undergoing reconstruction as part of salvage mastectomy for a local recurrence following breast-conserving therapy.54 One such patient developed a concave deformity of the chest wall following tissue expansion.55 Other types of subpectoral prostheses may be less subject to complications, at least in carefully selected individuals.56–58

In summary, radiation causes complex tissue changes presenting as interstitial fibrosis, arteriolar wall thickening and obliteration that manifests in increased rates of capsular contractures at the implant/tissue interface, as well as impaired skin healing. This sequence further involves impaired immune response and abnormal healing resulting in increased rate of infections. Healing can be facilitated if autologous flaps are transferred to the radiated bed.

Autologous Flaps

The muscular or musculocutaneous flap is indicated for reconstruction of radiation induced wounds or contractures, and for delayed breast reconstruction after previous radiation. The addition of nonradiated, well-vascularized tissue results in improved healing and prevents complications. The concept of delayed breast reconstruction was derived from chest wall reconstruction/resurfacing, and similarly uses flap donor sites from abdomen, and dorsum. Delayed breast reconstruction has many advantages, including the certainty of skin flap viability as the mastectomy wound is fully healed, and finalized pathologic status of the cancer. Perhaps the most important advantage is knowing not to use an implant in this situation. In addition, the radiation damage to the skin can be assessed more accurately, and any tissues severely damaged by radiation can be discarded at the time of reconstruction. The skin paddle of the designed flap can be then tailored to replace the missing breast surface skin, eliminating negative side effects of radiation such as discoloration, induration, and telangiectasia formation. Major drawbacks associated with delayed reconstruction are the need for large skin paddles for recreation of the breast mound, a second anesthesia, and significant psychologic stress for the patient forced to live with body deformity until the reconstruction. Flap selection can be limited in such cases, particularly when large skin paddles are needed, and even flaps such as latissimus dorsi may not be able to provide enough skin. However, delayed breast reconstruction procedures generally have had excellent and stable long-term esthetic results.59

The risk of complications in patients undergoing postmastectomy radiotherapy or radiotherapy for breast-conserving therapy who have a “delayed” reconstruction with a TRAM flap months to years later appears comparable to those patients who have not been irradiated. Williams et al described results in patients treated with pedicle flaps from 1981 to 1993 at Emory University in Atlanta, who underwent radiotherapy followed by delayed reconstruction.60 The risk of complications showed little difference between the 572 nonirradiated patients (17%) and the 108 irradiated patients. Complication rates in one series of patients undergoing reconstruction after local recurrence following breast-conserving therapy were higher when latissimus flaps were used (47%) than when TRAM flaps were used (25%),61 but many of these were minor, and no patient in this series suffered complete flap loss.

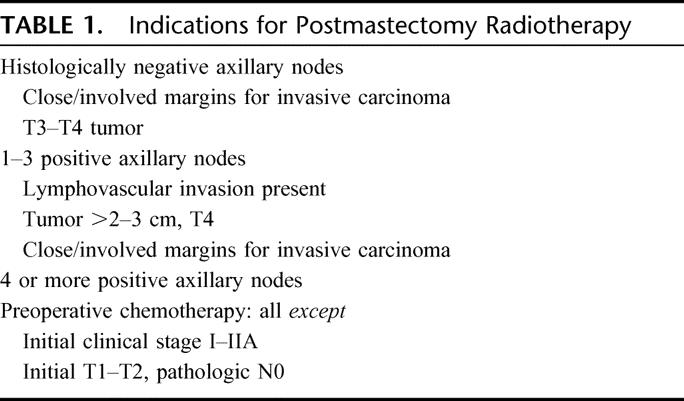

The results in patients who undergo reconstruction before radiotherapy, however, have been much more varied (Table 3). Tran et al found a significantly higher rate of delayed complications (fat necrosis, volume loss, and flap contracture) among patients undergoing immediate free-flap reconstructions, followed by radiotherapy, as compared with those having a delayed reconstruction (after radiotherapy).62 Poor results have also been reported for patients who undergo irradiation after a deep inferior epigastric perforator (“DIEP”) flap compared with nonirradiated patients.63 Groups from Emory University64 and the Brigham and Women's Hospital have reported increased rates of complications and the need for major corrective surgery in patients irradiated after pedicled TRAM flap reconstruction, however, markedly better than high rates of postoperative complications with implants (up to 40%). Hence, the exact type of reconstructive flap used may be critical to the outcome of patients undergoing immediate reconstruction and irradiation.

TABLE 3. Sequencing of Surgery and Postmastectomy and Risk of Significant Complications in Patients Undergoing Flap Reconstruction

Details of Radiotherapy Technique and the Risk of Complications

There is little information on how the details of postoperative radiotherapy affect the risk of complications after either tissue expander/implant or autologous flap techniques. Many variables exist including: the daily dose (“fraction size”); the total dose given to the chest wall as a whole; whether a “boost” dose is given to the mastectomy scar or a portion of the chest wall; the use of tissue-equivalent material placed on the skin (“bolus”) to increase the skin dose; the homogeneity of the dose deposited within the treated area, which in turn depends on the patient's body size, the photon or electron beam energy used, and the dose-prescription convention; and the possible adverse affects of overlaps between treatment fields. In addition, chemotherapy (especially if given concurrently with radiotherapy) and tamoxifen might potentially increase the risk of complications.

One of the most careful studies of how these parameters affect the risk of complications after expander/implant reconstruction was performed by investigators of the Michigan Breast Reconstruction Outcome study.50 The risks of complications and reconstruction failure were not substantially affected by whether regional nodes were irradiated, by total dose (< or >60 Gy), by the use of a boost or bolus, or by the timing of radiotherapy and reconstruction. They did find that the use of tamoxifen increased the risk of complications (75% vs. 57%) and the rate of expander/implant reconstruction failure (58% vs. 0%). However, there were only 19 irradiated patients in this study (of whom 12 received tamoxifen). In contrast, a study from Massachusetts General Hospital and Boston Medical Center of 48 patients treated with either tissue/expander implant or TRAM flap and radiotherapy found tamoxifen did not affect the risk of complications.66

DISCUSSION

Reconstructive Techniques and Irradiated Patient

Nonirradiated patients are candidates for all immediate reconstructive techniques, customized to their need. Irradiated patients have been treated both with expander/implants, and autologous flaps. Based on the available data, the expander/implant is a worse option for irradiated patients than purely autologous flap reconstruction, regardless of the timing of the surgery in relation to when radiotherapy is given. It is also becoming clear that radiation to the reconstructive flap causes unpredictable changes and worsens the final esthetic outcome. Under ideal circumstances, an immediate reconstruction would still be the preferred option due to previously mentioned reasons. How would one spare the flap from radiation and prevent radiation induced contraction of the native skin flaps? A possible solution would be to insert an expander as a spacer at the time of mastectomy, leave the prosthesis in during the radiation period to lessen the skin flaps' contraction, and remove it at the time of the final reconstruction. An autologous flap reconstruction could be performed after the radiation treatment is completed, avoiding the known harmful effects. Potential problems with this approach would include expander/spacer perioperative infection or radiation induced wound complications such as extrusion of the prosthesis, which could have adverse effect by delaying the radiotherapy.

Currently, the evidence suggests that most irradiated patients (as well as patients who are smokers or obese) will likely obtain the best esthetic results with the fewest complications from delayed free or pedicled TRAM flap reconstruction (without a contralateral skin/subcutaneous tissue component) based on surgeon's preference. For small-breasted patients, a latissimus dorsi flap without an implant would perhaps be a better alternative, as the muscle resists atrophy following radiation better than flaps with high fat content. (To date, however, despite the use of latissimus muscle or musculocutaneous flaps to treat radiation-induced wounds on the chest, there are no studies of outcomes of latissimus flaps placed prior to irradiation.)

Reconstructive Strategies for Patients With Unclear Indications for Postmastectomy Radiotherapy

The above conclusions pose a major dilemma for patients needing mastectomy, reconstructive plastic surgeons, and radiation oncologists. Is there a way to reconcile the patient's desire for immediate reconstruction with the increasing use of postmastectomy radiotherapy in a way that minimizes her risk of complications while maximizing her potential satisfaction from the results? We suggest 2 possible approaches.

As noted above, the key factor needed to decide whether postmastectomy radiotherapy will be used for patients with tumors smaller than 5 cm is the pathologic status of the axillary lymph nodes. Sentinel node biopsy performed before mastectomy could be the solution for this difficult problem. One option, therefore, would be to have patients desiring reconstruction with a prosthesis or expander/implant undergo sentinel lymph node sampling prior to mastectomy. If the sentinel nodes are negative, then almost certainly postmastectomy radiotherapy will not be needed, and the patient can proceed accordingly.

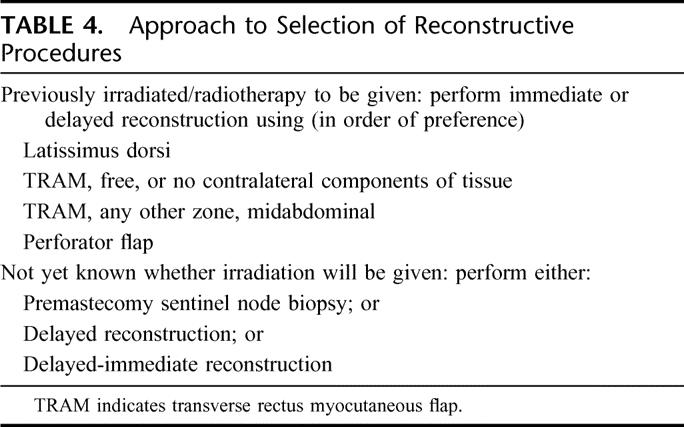

A second approach would be to perform the modified radical mastectomy, wait 3 to 5 days for the final pathologic report, and then perform reconstruction on a “delayed-immediate” basis. This approach has the advantage that all the information needed to decide whether postmastectomy radiotherapy is indicated is available (eg, pathologic tumor size, the exact number of nodes involved, tumor size, lymphovascular invasion, and margin status). It creates a disadvantage by requiring a patient to undergo general anesthesia twice in a short period of time, but there are no data suggesting that the cumulative risk of several anesthesias increases morbidity or mortality. Many patients, however, may not be agreeable to 2 successive major operations over a few days. If the patient requires radiotherapy and undergoes immediate reconstruction, latissimus dorsi without an implant appears to be the best solution for small breasted patients as the muscle does not atrophy following radiation as much as tissues with high fat content (eg, TRAM). A tissue expander could be placed beneath the flap in anticipation of a later need for an implant. Since well-vascularized tissues are best able to resist the harmful effects of radiotherapy, a free TRAM or pedicled TRAM flap without any contralateral component could be included on the list of options. Similarly, perforator flaps based on the selected dominant muscle perforators might constitute yet another option, despite the apparent diminished vascularity of a flap lacking the nondominant and random part of muscular perferators present in pedicled TRAM flaps.

Our proposed approach is summarized in Table 4.

TABLE 4. Approach to Selection of Reconstructive Procedures

CONCLUSION

The reconstructive plastic surgeon plays an important role in the care of patients with breast cancer who are treated with either breast-conserving therapy or mastectomy. Changes in the oncologic management of patients are leading to radiotherapy being used in more patients, particularly those undergoing mastectomy. This trend poses new challenges for patients seeking breast reconstructive surgery. While there is no consensus about the best reconstructive option for patients undergoing postoperative radiation, we think that the proposed approaches may be valuable guides for solving these dilemmas.

Footnotes

Reprints: Sumner A. Slavin, MD, 1101 Beacon Street, Brookline, MA 02446. E-mail: sslavin@bidmc.harvard.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cuzick J, Stewart H, Rutqvist L, et al. Cause-specific mortality in long-term survivors of breast cancer who participated in trials of radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:447–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group: Effects of radiotherapy and surgery in early breast cancer: an overview of the randomized trials. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1444–1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group: Favourable and unfavourable effects on long-term survival of radiotherapy for early breast cancer: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2000;355:1757–1770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Recht A. The return (?) of postmastectomy radiotherapy [Editorial]. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2861–2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris JR, Morrow M. Local management of invasive breast cancer. In: Harris JR, Lippman ME, Morrow M, et al, eds. Diseases of the Breast. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1996:485–545. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pierce LJ, Lichter AS. Defining the role of post-mastectomy radiotherapy: the new evidence. Oncology (Huntingt). 1996;10:991–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fowble B. Postmastectomy radiotherapy: then and now. Oncology (Huntingt). 1997;11:213–239.9057176 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris JR, Halpin-Murphy P, McNeese M, et al. Consensus statement on postmastectomy radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;44:989–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toth BA, Lappert P. Modified skin incisions for mastectomy: the need for plastic surgical input in preoperative planning. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87:1048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlson GW, Bostwick J III, Styblo TM, et al. Skin-sparing mastectomy: oncologic and reconstructive considerations. Ann Surg. 1997;225:570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Recht A, Edge SB, Solin LJ, et al. Postmastectomy radiotherapy: guidelines of the American Society of Clinical Oncology [Special Article]. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1539–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Veronesi U, Marubini E, Mariani L, et al. Radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery in small breast carcinoma: long-term results of a randomized trial. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:997–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1233–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arriagada R, Lê M, Rochard F, et al. Conservative treatment versus mastectomy in early breast cancer: patterns of failure with 15 years of follow-up data. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1558–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blichert-Toft M, Rose C, Andersen JA, et al. A Danish randomized trial comparing breast conservation with mastectomy in mammary carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1992;11:19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poggi MM, Danforth DN, Sciuto LC, et al. Eighteen-year results in the treatment of early breast carcinoma with mastectomy versus breast conservation therapy: the National Cancer Institute Randomized Trial. Cancer. 2003;98:697–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Dongen JA, Bartelink H, Fentiman IS, et al. Randomized clinical trial to assess the value of breast-conserving therapy in Stage I and II breast cancer, EORTC 10801 Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1992;11:15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Recht A. Breast carcinoma: in situ and early-stage invasive cancers. In: Gunderson LL, Tepper JE, eds. Clinical Radiation Oncology. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 2000:968–998. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shapiro CL, Recht A. Side effects of adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1997–2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meric F, Buchholz TA, Mirza NQ, et al. Long-term complications associated with breast-conservation surgery and radiotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:543–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olivotto IA, Rose MA, Osteen RT, et al. Late cosmetic outcome after conservative surgery and radiotherapy: analysis of causes of cosmetic failure. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;17:747–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De la Rochefordière A, Abner A, Silver B, et al. Are cosmetic results following conservative surgery and radiotherapy for early breast cancer dependent on technique? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;23:925–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor ME, Perez CA, Halverson KJ, et al. Factors influencing cosmetic results after conservation therapy for breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31:753–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris JR, Levene MB, Svensson G, et al. Analysis of cosmetic results following primary radiation therapy for Stages I and II carcinoma of the breast. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1979;5:257–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dewar JA, Benhamou S, Benhamou E, et al. Cosmetic results following lumpectomy axillary dissection and radiotherapy for small breast cancers. Radiother Oncol. 1988;12:273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Limbergen E, Rijnders A, van der Scheuren E, et al. Cosmetic evaluation of breast conserving treatment for mammary cancer: 2. A quantitative analysis of the influence of radiation dose, fractionation schedules and surgical treatment techniques on cosmetic results. Radiother Oncol. 1989;16:253–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dodwell DJ, Povall J, Gerrard G, et al. Skin telangectasia: the influence of radiation dose delivery parameters in the conservative management of early breast cancer. Clin Oncol. 1995;7:248–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monson JM, Chin L, Nixon A, et al. Is machine energy (4–8 MV) associated with outcome for Stage I–II breast cancer patients? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37:1095–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matory WE, Wertheimer M, Fitzgerald TJ, et al. Aesthetic results following partial mastectomy and radiation therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;85:739–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Love SM, Troyan S, Mills D, et al. Partial mastectomy with immediate reconstruction and radiation for extensive breast cancers: a pilot study [Abstract]. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1992;23:142. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noguchi M, Minami M, Earashi M, et al. Oncologic and cosmetic outcome in patients with breast cancer treated with wide excision, transposition of adipose tissue with latissimus dorsi muscle, and axillary dissection followed by radiotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1995;35:163–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monticciolo DL, Ross D, Bostwick J, et al. Autologous breast reconstruction with endoscopic latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flaps in patients choosing breast-conserving therapy: mammographic appearance. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:385–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petit JY, Garusi C, Gruese M, et al. One hundred and eleven cases of breast reconstruction treatment with simultaneous reconstruction at the European Institution of Oncology (Milan). Tumori. 2002;88:41–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pagliari C, Bonetta A, Morrica B. Central quadrantectomy with plastic surgery plus RT: a feasibility study [Abstract]. 5th EORTC Breast Cancer Working Conference. Leuven, Belgium, 1991:A153. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noguchi M, Saito Y, Mizukami Y, et al. Breast deformity, its correction, and assessment of breast conserving surgery. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1991;18:111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grisotti A. Problems of breast reconstruction after segmental mastectomy [Abstract]. 5th European Conference on Clinical Oncology. London, 1989:S72. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas PRS, Ford HT, Gazet JC. Use of silicone implants after wide local excision of the breast. Br J Surg. 1993;80:868–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bostwick J, Paletta C, Hartrampf CR. Conservative treatment for breast cancer: complications requiring reconstructive surgery. Ann Surg. 1986;203:481–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salmon RJ, Razaboni R, Soussaline M. The use of the latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap following recurrence of cancer in irradiated breasts. Br J Plast Surg. 1988;41:41–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bostwick J. Reconstruction after mastectomy. Surg Clin North Am. 1990;70:1125–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Overgaard M, Hansen PS, Overgaard J, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy in high-risk premenopausal women with breast cancer who receive adjuvant chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:949–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ragaz J, Jackson SM, Le N, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy in node-positive premenopausal women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:956–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Recht A, Edge SB. Evidence-based indications for postmastectomy irradiation. Surg Clin North Am. 2003;83:995–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Overgaard M, Jensen M-J, Overgaard J, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy in high-risk postmenopausal breast-cancer patients given adjuvant tamoxifen: Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group DBCG 82c randomized trial. Lancet. 1999;353:1641–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ragaz J, Jackson S, Le N, et al. Postmastectomy radiation (RT) outcome in node (N) positive breast cancer patients among N 1–3 versus N4+ subset: impact of extracapsular spread (ES). Update of the British Columbia randomized trial [Abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1999;18:73. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whelan TJ, Julian J, Wright J, et al. Does locoregional radiation therapy improve survival in breast cancer? A meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1220–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cody HS, Hill ADK, Tran KN, et al. Credentialing for breast lymphatic mapping: how many cases are enough? Ann Surg. 1999;229:723–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vandeweyer E, Deraemaecker R. Radiation therapy after immediate breast reconstruction with implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106:56–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Forman DL, Chiu J, Restifo RJ, et al. Breast reconstruction in previously irradiated patients using tissue expanders and implants: a potentially unfavorable result. Ann Plast Surg. 1998;40:360–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krueger EA, Wilkins EG, Strawderman M, et al. Complications and patient satisfaction following expander/implant breast reconstruction with and without radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;49:713–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spear SL, Onyewu C. Staged breast reconstruction with saline-filled implants in the irradiated breast: recent trends and therapeutic implications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:930–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dickson MG, Sharpe DT. The complications of tissue expansion in breast reconstruction: a review of 75 cases. Br J Plast Surg. 1987;40:629–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Olenius M, Jurell G. Breast reconstruction using tissue expansion. Scand J Plast Reconstr Hand Surg. 1992;26:83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tallet AV, Salem N, Moutardier V, et al. Radiotherapy and immediate two-stage breast reconstruction with a tissue expander and implant: complications and esthetic results. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;57:136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fodor PB, Swistel AJ. Chest wall deformity following expansion of irradiated soft tissue for breast reconstruction. NY State J Med. 1989;89:419–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fowble B, Solin L, Schultz D, et al. Breast recurrence following conservative surgery and radiation: patterns of failure, prognosis, and pathologic findings from mastectomy specimens with implications for treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1990;19:833–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barreau-Pouhaer L, Lê MG, Rietjens M, et al. Risk factors for failure of immediate breast reconstruction with prosthesis after total mastectomy for breast cancer. Cancer. 1992;70:1145–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.LaRossa D. Reconstructive surgery. In: Fowble B, Goodman RL, Glick JH, et al., eds. Breast Cancer Treatment: A Comprehensive Guide to Management. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book, 1991:311–324. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schuster RH, Kuske RR, Young VL, et al. Breast reconstruction in women treated with radiation therapy for breast cancer: cosmesis, complications, and tumor control. Plas Reconstr Surg. 1992;90:445–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Williams JK, Bostwick J, Bried JT, et al. TRAM flap breast reconstruction after radiation treatment. Ann Surg. 1995;221:756–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kroll SS, Schusterman MA, Reece GP, et al. Breast reconstruction with myocutaneous flaps in previously irradiated patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93:460–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tran NV, Chang DW, Gupta A, et al. Comparison of immediate and delayed free TRAM flap breast reconstruction in patients receiving postmastectomy radiation therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:78–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rogers NE, Allen RJ. Radiation effects on breast reconstruction with the deep inferior epigastric perforator flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:1919–1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Williams JK, Carlson GW, Bostwick J, et al. The effects of radiation treatment after TRAM flap breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100:1153–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wong JS, Kaelin CM, Ho A, et al. Incidence of subsequent major corrective surgery after postmastectomy breast reconstruction and radiation therapy [Abstract]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54(2 suppl.):4–5. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chawla AK, Kachnic LA, Taghian AG, et al. Radiotherapy and breast reconstruction: complications and cosmesis with TRAM versus tissue expander/implant. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54:520–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Evans GRD, Schusterman MA, Kroll SS, et al. Reconstruction and the irradiated breast: is there a role for implants? Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:1111–1115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Contant CME, van Geel AN, van der Holt B, et al. Morbidity of immediate breast reconstruction (IBR) after mastectomy by a subpectorally placed silicone prosthesis: the adverse effect of radiotherapy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26:344–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]