Abstract

Percutaneous vertebroplasty (PVP) is an effective treatment for lesions of the vertebral body that involves a percutaneous injection of polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA). Although PVP is considered to be minimally invasive, complications can occur during the procedure. We encountered a renal embolism of PMMA in a 57-year-old man that occurred during PVP. This rare case of PMMA leakage occurred outside of the anterior cortical fracture site of the L1 vertebral body, and multiple tubular bone cements migrated to the course of the renal vessels via the valveless collateral venous network surrounding the L1 body. Although the authors could not explain the exact cause of the renal cement embolism, we believe that physicians should be aware of the fracture pattern, anatomy of the vertebral venous system, and careful fluoroscopic monitoring to minimize the risks during the PVP.

Keywords: Percutaneous vertebroplasty, Bone cement, Embolism, Vertebral venous system

Introduction

Percutaneous vertebroplasty (PVP) is an effective, minimally invasive procedure in which polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) cement is injected into a diseased vertebral body. This technique provides pain relief and strengthens weakened vertebral bodies. Vertebroplasty has gained widespread popularity for the treatment of benign or malignant compression fractures since its initial description 21 years ago [9]. However, complications can still occur during the procedure even though PVP is considered to be minimally invasive. The reported complication rates range from 1 to 10%, but are generally minor [3]. This paper reports our experience of a renal cement embolism during PVP, with a review of the literature.

Case report

A 57-year-old man, who had fallen from a 2.4 m ladder 4 months earlier, complained of severe back pain. He had been a healthy farmer prior to the accident. However, since his fall, he had suffered from debilitating back pain refractory to conservative treatment for 2 months. In particular, he complained of activity-related pain corresponding to the level of a compression fracture. The outside computed tomography (CT) scans demonstrated a compression fracture of the L1 body without destruction of the posterior wall and significant vertebral collapse. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a slight step-off of the anterior cortical margin of the compressed L1 vertebral body, with lower marrow signal intensity on T1-weighted image (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The T1 weighted sagittal magnetic resonance image of the lumbar spine demonstrates a slight step-off of the anterior cortical margin of the compressed L1 vertebral body, with decreased marrow signal intensity

It was decided to proceed with PVP of the L1. The patient was placed in the prone position. An 11-gauge needle was advanced into the vertebral body via the left unilateral transpedicular approach using sterile technique and fluoroscopic guidance under local anesthesia. The PMMA (Zimmer Inc., IN, USA) cement has two components: an ampule of liquid and a fine powder of PMMA containing barium sulfate, e.g., 10 ml ampoule of liquid to 20 g of powder. Under careful fluoroscopic visualization, the mixture of PMMA cement and barium sulfate powder having a consistency similar to that of toothpaste was slowly injected into the vertebral body, diffusing throughout the intertrabecular marrow space. Before its injection, the mixture was loaded into several 1 ml syringes. However, when approximately 8 cc of PMMA had been injected unilaterally, multiple bone cement was detected at the bilateral renal fossae. The procedure was immediately stopped. After the procedure, the back pain had improved by more than 50%, but he still complained of severe right flank pain and fever. His renal function was impaired and the BUN to Cr ratio was high (27.2/1.3). On the same day, both kidneys were swollen (13 cm), and were found to contain a large amount of hyperechoic materials on the abdominal ultrasound (Fig. 2). The DMSA (99mTc dimercaptosuccinic acid) scan has been found to be quite useful for examining the bilateral kidney damage in detail, but the patient refused this. The CT scans showed the origin of the leak arising at the level of the vertebroplasty, and showed cement in the left anterior external venous plexus draining into both renal veins. Multiple tubular opacities, which corresponded to the course of the renal vessels, were detected, with some of the cement scattered through the left posterior external venous plexus on the CT scans (Fig. 3). The patient was diagnosed with a renal embolism and was treated conservatively. On the sixth day after the procedure, the BUN to Cr ratio had returned to normal, and the patient was released from hospital without pain. A follow-up ultrasound 8 months later revealed prominent atrophy of the right upper renal cortex with compensatory hypertrophy of the left kidney. However, the patient is currently doing well and has no subjective symptoms.

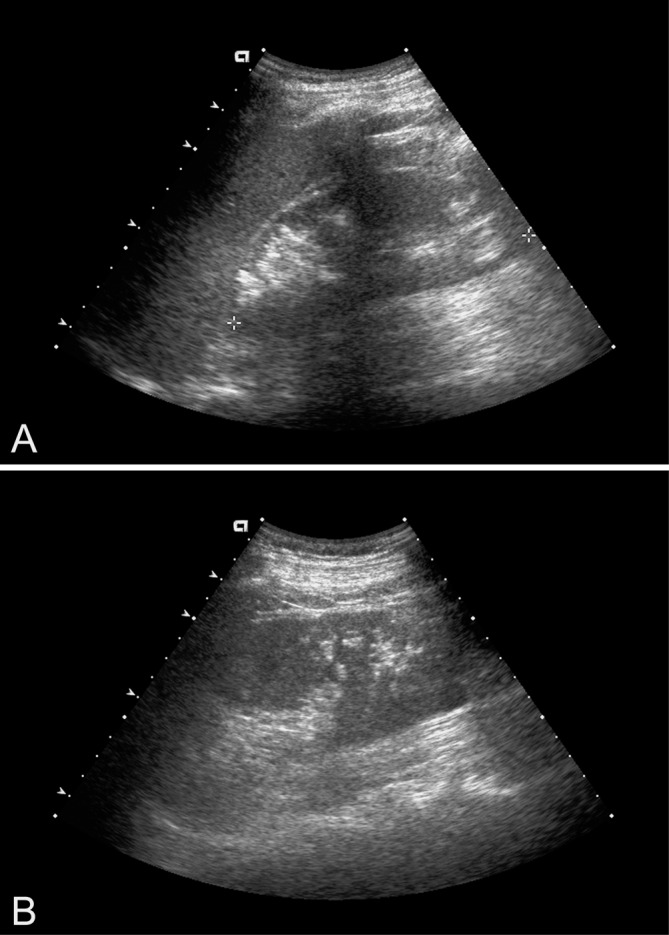

Fig. 2.

Both kidneys are swollen (13 cm), and the abdominal ultrasound shows large amounts of hyperechoic materials (a, right kidney; b, left kidney)

Fig. 3.

Computed tomography scans show the origin of the leak arising at the level of the vertebroplasty (a), revealing cements in the left anterior external venous plexus draining into both renal veins (b)

Discussion

Image-guided percutaneous vertebral augmentation or PVP, was first performed in France in 1984, when Deramond and Galibert et al. [9] injected PMMA into the C2 vertebra, which had been partially destroyed by an aggressive hemangioma. Over the next 15 years, many groups advocated expanding the indications for PVP to include osteoporotic compression fractures, traumatic compression fractures, and painful vertebral metastasis [2, 6, 7, 11, 18, 19]. Our case had the anterosuperior fracture of the L1 body without destruction of the posterior wall and significant vertebral collapse so that it might not lead to a technically difficult vertebroplasty procedure; or might not constitute relative contraindications [6].

Even though PVP has many advantages including its simplicity, easy approach, and minimally invasiveness, many authors have reported several complications. The reported complication rates range from 1 to 10%, with a higher incidence of complications in cases with metastatic lesions [3]. However, complications are rare (1~2%) with osteoporosis, and are generally asymptomatic and transient [2, 11, 19]. The reported complications associated with these procedures include hypotension, rib fractures [18], dural tear [1], pulmonary cement embolism [1, 4, 14], adult respiratory distress syndrome [18], cerebral cement embolism [15], root compression due to intraforaminal cement leakage [6], paraplegia due to spinal cord [6] and cauda equina compression [16], intravascular extension of cement [1], infection, and cement toxicity [12].

The vascular leakage of PMMA, although rare, might have disastrous consequences.

The viscosity of the PMMA cement is a crucial aspect during the procedure, and progressively increases as a result of methyl methacrylate polymerization. The rate of polymerization depends on several difficult-to-evaluate factors, including the ambient temperature and the quantity of the solvent. A paste is preferred to a liquid consistency because the latter may cause leakage of the PMMA into the venous system, particularly when the lesion is a highly vascular or extensive osteolytic tumor [5, 6]. However, it is not always possible to maintain the appropriate viscosity of PMMA at all times prior to the injection because the viscosity of the PMMA changes over time. The possibility that the renal cement embolism was caused by insufficient polymerization of the PMMA at the time of injection could not be excluded.

An adequate amount of the infusing PMMA is also recommended. Cotten et al. [6] reported that pain relief does not appear to be proportional to the degree of lesion filling by the PMMA. In addition, Martin et al. [13] reported that complications were mainly related to an excessive PMMA injection.

Good-quality fluoroscopy is essential for the early detection of a minimal cement leakage into the perivertebral vein. Jensen et al. [11] recommended a barium/tungsten combination in order to allow for adequate visualization of venous flow as well as early detection of venous PMMA migration during fluoroscopy. In our case, renal cement embolism caused by perivertebral venous migration was not early recognized. Injection was performed under lateral fluoroscopy, paying particular attention to the epidural space, the spinal canal, and the perivertebral veins. But real-time detection of laterovertebral leakage remained difficult owing to overlap of the cement filling vertebral body, even though intermittent anteroposterior fluoroscopy could not overcome this problem. Gangi et al. [8] recommended that CT guidance increases precision, improves the results, and reduces complications. But this is also the lack of real-time visualization of cement leak.

The vertebral venography should be carried out before the PMMA injection. However, its value is also contentious. Jensen et al. [11] advocated the use of antecedent venography to decrease the incidence of complications associated with the needle placement within the basivertebral venous plexus and to delineate the route of cement egress. However, Deramond et al. [7] reported that the lesion is stained by the injection of contrast media in the case of spinal tumors, which interrupts the early venous leakage, and that the different flow characteristics of the contrast material and PMMA hamper the predictive value of venography [14]. Venography is not usually performed at our center. In our case, the PMMA leaked outside of the left anterior cortical fracture site of the L1 vertebral body and multiple tubular bone cement migrated to the course of the renal vessels via the anterior external vertebral venous plexus. Anatomically, the vertebral venous system is a large valveless collateral venous network within and around the vertebral column, extending from the sacral hiatus along the entire length of the vertebral column up to the foramen magnum [10]. There are also a large number of connections to the subcutaneous and vertebral veins as well as the sacral venous plexus. We do not know whether the cause of the renal cement embolism was via the vertebral venous network or the inappropriate PMMA viscosity.

The patient’s position is also clinically important. Vogelsang reported that the intraosseous pressure recorded in the lumbar spinous process increased by compressing the inferior vena cava, which he called “retrograde congestion” [17]. Under this condition, the vertebral pressure is increased, which might reduce the risk of fat, bone marrow, air and bone cement extrusion into the IVVP and EVVP. Our procedure used a hand injection method for the PMMA in order to prevent an increase in the injection velocity.

We could not determine the precise cause after a lengthy review of the whole procedure, but it is possible that there might have been some vascular anomaly, such as congenital communication, between the vertebral venous system and renal vessels.

Conclusion

The authors encountered an unexpected renal embolism during PVP. We could not explain the exact cause of the renal cement embolism, but we believe that physicians should be aware of the fracture pattern, anatomy of the vertebral venous system, and careful fluoroscopic monitoring to minimize the risk during the PVP.

References

- 1.Amar AP, Larsen DW, Esnaashari N, Albuquerque FC, Lavine SD, Teitelbaum GP. Percutaneous transpedicular polymethylmethacrylate vertebroplasty for the treatment of spinal compression fractures. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:1105–1115. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200111000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barr JD, Barr MS, Lemley TJ, McCann RM. Percutaneous vertebroplasty for pain relief and spinal stabilization. Spine. 2000;25:923–928. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200004150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barr MA, Barr JD. Invited commentary. RadioGraphics. 1998;18:320–322. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernhard J, Heini PF, Villiger PM. Asymptomatic diffuse pulmonary embolism caused by acrylic cement: an unusual complication of percutaneous vertebroplasty. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:85–86. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cotten A, Dewarte F, Coret B, Assaker R, Leblond D, Duquesnoy B, Chastanet P, Clarisse J. Percutaneous vertebroplasty for osteolytic metastases and myeloma; effects of the percentage of lesion filling and the leakage of methylmethacrylate at clinical follow-up. Radiology. 1996;200:525–530. doi: 10.1148/radiology.200.2.8685351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cotten A, Boutry N, Cortet B, Assaker R, Demondion X, Leblond D, Chastanet P, Duquesnoy B, Deramon H. Percutaneous vertebroplasty: state of the art. Radiographics. 1998;18:311–320. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.18.2.9536480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deramond H, Galibert P, Debussche C. Percutaneous vertebroplasty with methylmethacrylate: technique, method, result. Radiology. 1990;177:352. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gangi A, Kastler BA, Dietemann JL. Percutaneous vertebroplasty guided by a combination of CT and fluoroscopy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15:83–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galibert P, Deramond H, Rosat P, Le Gars D. Preliminary note on the treatment of vertebral angioma by percutaneous acrylic vertebroplasty. Neurochirurgie. 1987;33:166–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groen RJ, du Toit DF, Phillips FM, Hoogland PV, Kuizenga K, Coppes MH, Muller CJ, Grobbelaar M, Mattyssen J. Anatomical and pathological considerations in percutaneous vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty: a reappraisal of the vertebral venous system. Spine. 2004;29:1465–1471. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000128758.64381.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen ME, Evans AJ, Mathis JM, Kallmes DF, Cloft HJ, Dion HE. Percutaneous polymethylmethacrylate vertebroplasty in the treatment of osteoporotic vertebral body compression fractures: technical aspects. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:1897–1904. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lane JM, Johnson CE, Khan SN, Girardi FP, Cammisa FP., Jr Minimally invasive options for the treatment of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. Orthop Clin North Am. 2002;33:431–438. doi: 10.1016/S0030-5898(02)00003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin JB, Jean B, Sugiu K, San Millan Ruiz D, Piotin M, Murphy K, Rufenacht B, Muster M, Rufenacht DA. Vertebroplasty: clinical experience and follow-up results. Bone. 1999;25:11S–15S. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(99)00126-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Padovani B, Kasriel O, Brunner P, Perretti-Viton P. Pulmonary embolism caused by acrylic cement: a rare complication of percutaneous vertebroplasty. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:375–377. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scroop R, Eskridge J, Brz GW. Paradoxical cerebral arterial embolization of cement during intraoperative vertebroplasty: a case report. Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23:868–870. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 16.Shapiro S, Abel T, Purvines S. Surgical removal or epidural and intradural polymethymethacrylate extravasation complicating percutaneous vertebroplasty for an osteoporotic lumbar compression fracture. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:90–92. doi: 10.3171/spi.2003.98.1.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vogelsang H. Intraosseous spinal venography. Amsterdam: Excerpta Medica; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watts NB, Harriw ST, Genant HK. Treatment of painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures with percutaneous vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12:429–437. doi: 10.1007/s001980170086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weill A, Chiras J, Simon JM, Rola-Martinez T, Enkaoua E. Spinal metastases: indications for and results of percutaneous injection of acrylic surgical cement. Radiology. 1996;199:241–247. doi: 10.1148/radiology.199.1.8633152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]