Abstract

Osteoma is a common benign tumor. It occurs dominantly at the skull bone. Outside skull osteoma is rare, and primary intra-canal osteoma is extremely rare. To the author’s knowledge, only 14 cases of osteomas of the spine had been reported, in which only seven cases were in English literature. The authors reported two rare cases of intra-canal osteoma of the upper cervical spine with cord compression. Included are pertinent history, physical examination, rontgenographic evaluation before and after operation, surgical interventions, pathological study, and outcome. The available literature is also reviewed. On systemic examination and rontgenographic study, these two cases were found to have bone tumor in the upper cervical canal. Surgical interventions were performed, one with an en bloc excision, the other with a subtotal excision. The pathological study demonstrated a diagnosis of osteoma. After a follow-up with 20 and 15 months, the clinical symptoms of both cases significantly improved.

Keywords: Osteoma, Cervical spine, Myeolopathy, Intra-canal, Operative treatment

Introduction

Osteomas are rare, slow growing lesions composed of compact bone that occur almost exclusively in the skull [2, 7], most often in the inner and outer table of the calvarium or in the bones of the face or mandible [1, 12, 13]. The prevalence of this disease amounting those who have had sinus radiographs has been estimated to be 0.42% [7]. Although these lesions may cause sinusitis or exophthalmos when they arise from the wall of the nasal sinuses or the orbit, cranial osteomas often cause no symptoms and are discovered incidentally.

Primary intra-canal osteomas are extremely rare. To the authors’ knowledge, at the time of writing, only 14 cases of osteomas of the spine had been reported, in which only seven cases were in the English literature [4–6, 8, 9, 11].

The purpose of this article is to report on two patients who presented with cervical intra-canal osteoma.

Case report

Case One

A 56-year-old man had presented with paresis and weakness of his extremities after a hyperextension injury of the cervical spine in August 2002. The man had been asymptomatic prior to the accident.

Physical examination demonstrated limitation in neck rotation, and motor weakness of the extremities with strength 3/5 in upper extremities and 4/5 in lower extremities. He could eat with chopsticks to a limited degree. He could walk. However, he needed cane or aid on stairs. Hypoesthesia was present at the upper extremities, bilaterally. The biceps tendon reflex, patellar tendon reflex, and Achilles tendon reflex were hyperactive, and the Hoffman and Babinski reflex were positive bilaterally. Sustained ankle clonus was present, bilaterally. Neurological examination was consistent with upper neuron cell injury. The Japanese orthopedic association (JOA) score for cervical myelopathy was 11.

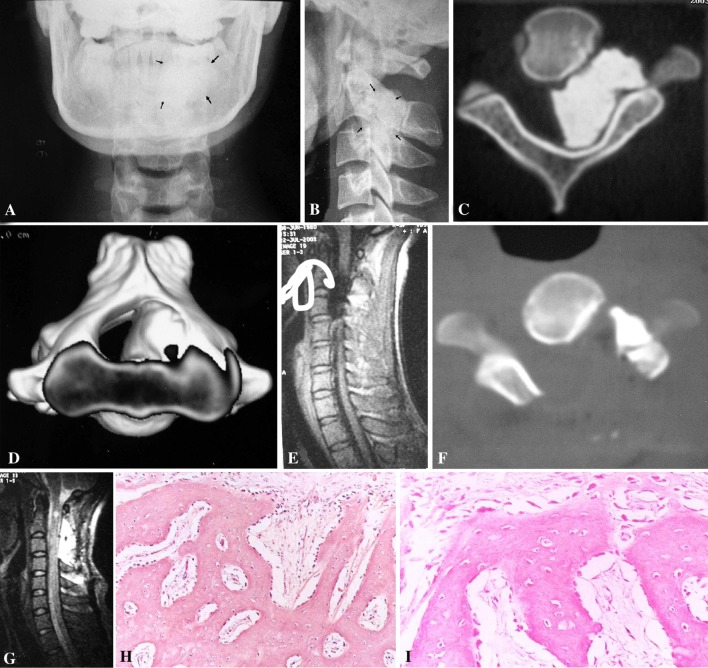

Preoperative imaging study demonstrated a cortical like solid lesion. The results were shown in Fig. 1a–e.

Fig. 1.

a Cervical A–P view X-ray showed densification at left side at C2–3 level. b Cervical lateral view X-ray showed high density at C2–3 level, the facet joints between C2\C3 were obscure. c CT scan through the intervertebral foramen between C2 and C3 showed the tumor occupied more than 60% canal and the vertebral shape changed, caused by the chronic pressure. d Three dimensions CT reconstruction showed the three-dimension relationship between the tumor and the cervical spinal canal. e Middle sagittal plane T1WI MRI showed the spinal cord was pressed by the tumor. The signal of the tumor was low. f The same plane as c after operation, showed the whole decompression of the spinal canal, part of the tumor, near the vertebral artery was left. g The same plane as e after operation, showed the whole decompression of the cord and spinal canal. h, i The pathological study showed that the lesion was composed of uniformly dense, compact, cortical-like mature lamellar bone. H: ×100, I: ×400

We performed a leminectomy of C2 and C3. In the operation, we found that the tumor was adhesive with the left side vertebral artery. To avoid the injury of the artery, part of the tumor, near the vertebral artery, was left. However the decompression of the spinal cord was enough (Fig. 1f–g). The pathological study showed that the lesion was composed of uniformly dense, compact, cortical-like, mature lamellar bone (Fig. 1h–i), and a diagnosis of osteoma was made. Two weeks after the operation, this patient’s clinical symptoms improved significantly. Then, with hard cervical brace protection, the patient was permitted to ambulate. He noted gradual improvement of strength in his upper extremity. Three months later, the brace was removed. Twenty months later, the muscle strength was 5/5 in all extremities. He could eat with chopsticks, but awkwardly. He could walk with no disability. No hypoesthesia was present. The patient’s JOA score increased from 11 to 16 (Table 1).

Table 1.

JOA score of the two cases before and after therapy

| Before therapy | Follow-up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 1 | Case 2 | |

| Motor | ||||

| Upper extremity | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Lower extremity | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| Feeling | ||||

| Upper extremity | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Trunk | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Lower extremity | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Sphincter | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Total | 11 | 10 | 16 | 15 |

Case two

A 49-year-old man had experienced paresis and weakness of his extremities after a weight-hit injury of the head in November 2002. The man had been asymptomatic before the accident. Physical examination showed moderate motor weakness and hypoesthesia of the upper extremity, with strength 3/5 in upper extremities and 4/5 in lower extremities. He could eat with spoon but could not with chopsticks. He could walk. However, he needed a cane or aid on stairs. The feel of trunk and lower extremity is fair. The biceps, patellar, and Achilles tendon reflexes were hyperactive, and the Hoffman and Babinski reflexes were positive bilaterally. Ankle clonus was noted continuously on both sides.

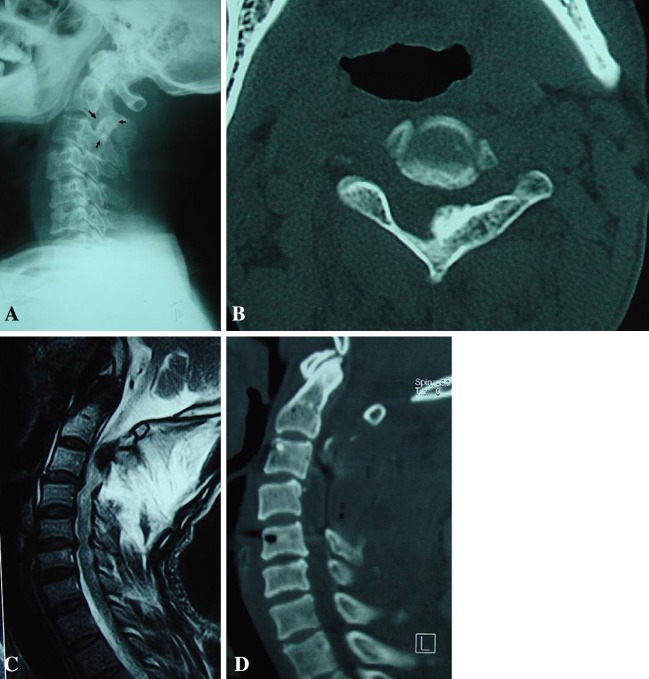

Preoperative imaging study demonstrated lamina fracture of C3, traumatic instability of C3–5, and a cortical like solid lesion at the left side of C2 lamina. The results were shown in Fig. 2a–c.

Fig. 2.

a Cervical lateral view X-ray showed high density at C2–3 level, the facet joints between C2\C3 were obscure, traumatic instability of C3–5. b CT scan through C2 showed the tumor at the left side of the lamina, occupied about 20% canal, and the left side lamina of the C2 became thicker. c Sagittal plane T2WI MRI showed the spinal cord was pressed by the tumor. The signal of the tumor was low. d Three-dimension CT reconstructive image showed complete decompression

We performed a laminectomy of C3–C4 and part of C2, as well as internal fixation of C3–5, using pedicle screw system. The tumor was removed completely and the spinal cord was decompressed. The pathological study showed that the lesion was also composed of uniformly dense, compact, cortical-like, mature lamellar bone without nidus (not shown). Lateral view X-ray after operation showed the reconstruction of the stability by the pedicle screw system and lamina decompression of C3–4 and part of C2. Three dimension CT reconstructive image showed complete decompression of the spinal cord (Fig. 2d).

A month after the operation, this patient’s clinical symptoms improved significantly. Then, with hard cervical brace protection, the patient was permitted to ambulate, and he noted gradual improvement of strength in his upper extremity also. Three months later, the brace was removed. After 15 months, the muscle strength was 4/5 in upper extremity and 5/5 in lower extremity. He could eat with chopsticks, but awkwardly. He could walk without cane or aid, but slowly. No hypoesthesia was present. The JOA score increased from 10 to 15 (Table 1).

Discussion

Congenital disease, rheumatoid arthritis, fracture and dislocation, and other systemic diseases can cause the compression of the upper cervical spinal cord [14]. However, osteoma is one of the rare reasons. Osteoma is defined by WHO as a benign lesion consisting of well differentiated mature bone tissue with a predominantly laminar structure, and showing very slow growth. Osteomas are bosselated, round to oval sessile tumors that project from the subperiosteal or endosteal surfaces of the cortex [3]. They are composed of a composite of woven and lamellar bone that is frequently deposited in a cortical pattern with haversian-like systems. Some variants contain a component of trabecular bone in which the intertrabecular spaces are filled with hematopoietic marrow [10]. Osteoma usually occurs in the skull. Only occasionally have these lesions been reported in extracranial locations (Table 2). In 1980, Pecker et al. reported the first osteoma in cervical inter-vertebral foramen. They used a Lateral interscalenic approach to excise the lesion [8]. In 1986, Lantsman reported six cases of osteoma in spine, but the article was in Russian, no more details could be reviewed [4]. In 1993 [5] and 1996 [6] Laus reported the same case in Italian and English. To excise the lesion, they performed an anterior prevascular extra oral approach. In 1996 [9], Peyser reported 11 cases of extracranial osteoma, in which five were in spine, one in the cervical spine, two in the lumbar spine and two in the scrum spine. In 1998 [11], Rengachary reported that another osteoma affected the cervical spine.

Table 2.

Cases reported in the literature

| References | Article language | Case number | Site of the lesion | Recurred |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rengachary [11] | English | 1 | Cervical | No |

| Peyser [9] | English | 5 | Cervical (1), lumbar (2), sacrum (2) | One pain recurred |

| Laus [6] | English | 1 | Cervical | No |

| Laus [5] | Italy | 1 | Cervical | No |

| Lantsman [4] | Russian | 6 | Spine | No |

| Pecker [8] | French | 1 | Cervical | No |

| Total | 14a |

aLaus M. reported the same case in English and Italy

The diagnosis of intra-canal osteoma is still confusing. In Peyser’s series [9], none of the cases had correct diagnosis before the operation. In our cases, the rontgenographic study before operation could give some clues, but the final diagnosis still depended on the pathological findings. Histologically, the reactive bone induced by infection and trauma may be similar with a true osteoma [10]. However the differential diagnosis can be made by the tumor’s site and pertinent history. Traumatic reactive bones are most frequently observed in relation to the femur, beneath the quadriceps, in relation to the adductor magnus (the so-called rider’s bone) or in relation to the medial collateral ligament of the knee joint. The condition is also not infrequent at the elbow, the exostosis forming in the intermuscular planes of the brachialis following dislocation. Injury leads to the formation of a subperiosteal hemorrhage, the periosteum being detached by muscular traction. If the periosteum remains intact, the hematoma may become absorbed; but if the periosteal reapposition and the absorption of the blood clot are prevented, traumatic bone overgrowth may occur. However, this condition could not occur at the endosteum. In the case of infective reactive bones, an infection history of relevant site should be noted.

The clinical features of osteoma in the spine may be confusing. Cranial osteomas often cause no symptoms and are discovered incidentally, although these lesions may cause sinusitis or exophthalmus when they arise from the wall of the nasal sinuses or the orbit. It would be expected that the symptoms of spinal osteoma would depend on the location of the lesion and its relationship with the peripheral tissue. As Rengachary [11] and Laus [5, 6] reported, the symptom of the spinal osteoma was caused from spinal cord or nerve root pressure. However in Peyser’s series all but one of the patients was symptomatic and had dull, aching pain at the time of the initial presentation. In our series, the two cases had no symptom before the injuries. It may be because osteomas are benign and very slow-growing lesions. And the spinal cord and never roots may adapt to the chronic pressure. Since the lesions cause spinal canal stenosis, they can cause the spinal cord to be more easily damaged by minor injury.

The growth potential of osteoma remains unclear, as we know the cranial osteomas grow very slowly. Peyser’s excellent work showed us the growth potential feature of the spinal osteoma [9]. In their series, one patient who had a juxtacortical osteoma of the cervical spine, showed no major change on serial CT scans performed twelve years apart. However, another patient’s sacral osteoma showed significant growth on serial radiographs performed 18 years apart. The method of surgical management of an osteoma depends on the growth feature of the tumor. Cranial osteoma does not need surgical excision if there are no symptoms. The aim of surgical management of spinal osteoma is decompression and stabilization if instability exists. Rengachary and Laus performed total excision of the lesion, with no tumor recurrences. Peyser performed three total and two subtotal excisions, in the case series of osteomas, none recurred. However in one of the patients, partial resection of an osteoma from the body of the fifth lumbar vertebra resulted in no relief of pain and necessitated an additional procedure to remove the remainder of the lesion. In our series, it was relatively easy to perform an en bloc excision in the second case. In the first case, in view of a patient’s age and risk of vertebral artery injuries, a subtotal excision was performed, also with satisfied short time outcome. However, the follow-up was not long enough to observe the recurrence.

Conclusion

The incidence of intra-canal osteomas is rare. It can cause upper cervical myeolopathy. The rontgenographic study before operation can give some clues, but the final diagnosis still depends on the pathological findings. Surgical treatment, either en bloc or subtotal excision of the lesion, may be effective.

Reference

- 1.Campanacci M (1990) Osteoma. In: Bone and soft tissue tumors. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York, pp 349–354

- 2.Fechner RE, Mills SE. Tumors of the bones and joints. In: Rosai J, Sobin LH, editors. Atlas of tumor pathology, Maryland: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1993. pp. 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fritz Schajowicz (1994) Bone-forming tumors. In: Tumors and tumor like lesions of bone, pathology, radiology, and treatment, 2nd edn. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York, p 29

- 4.Lantsman IuV Spine osteomas. Vopr Onkol. 1986;32:24–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laus M, Alfonso C, Laguardia AM, Giunti A. Anterior surgery of the upper part of the cervical spine by prevascular extraoral approach. Chir Organi Mov. 1993;78:65–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laus M, Pignatti G, Malaguti MC, Alfonso C, Zappoli FA, Giunti A. Anterior extraoral surgery to the upper cervical spine. Spine. 1996;21:1687–1693. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199607150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirra JM (1989) Osteoma. In: Bone tumors: clinical, radiologic and pathologic correlations. Lea and Febiger, Philadelphia, pp 174–182

- 8.Pecker J, Vallee B, Desplat A, Guegan Y. Lateral interscalenic approach for tumors of the cervical intervertebral foramina. Neurochirurgie. 1980;26:165–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peyser AB, Makley JT, Callewart CC, Brackett B, Carter JR, Abdul-Karim FW. Osteoma of the long bones and the spine. A study of eleven patients and a review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1996;78:1172–1180. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199608000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cotran RS, Kumar V, Collins T (1999) Robbins pathologic basis of disease, 6 edn. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 1235–1236

- 11.Rengachary SS, Sanan A. Ivory osteoma of the cervical spine: case report. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:182–185. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199801000-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Resnick D, Niwayama G (1988) Osteoma. In: Diagnosis of bone and joint disorders. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 4081–4084

- 13.Schajowicz F (1981) Osteoma. In: Tumors and tumorlike lesions of bone and joints. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York, pp 25–34

- 14.Wang W, Kong L, Zhao H, Jia Z. Ossification of the transverse atlantal ligament associated with fluorosis. A report of two cases and review of the literature. Spine. 2004;29:E75–E78. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000109762.46805.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]