Abstract

Metaphase-based comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) has identified recurrent regions of gain on different chromosomes in bladder cancer, including 6p22. These regions may contain activated oncogenes important in disease progression. Using quantitative multiplex polymerase chain reaction (QM-PCR) to study DNA from 59 bladder tumors, we precisely mapped the focal region of genomic gain on 6p22. The marker STS-X64229 had copy number increases in 38 of 59 (64%) tumors and the flanking markers, RH122450 and A009N14, had copy number gains in 33 of 59 (56%) and 26 of 59 (45%) respectively. Contiguous gain was present for all three markers in 14 of 59 (24%) and for two (RH122450 and STS-X64229) in 25 of 59 (42%). The genomic distance between the markers flanking STS-X64229 is 0.5 megabases, defining the minimal region of gain on 6p22. Locus-specific interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization confirmed the increased copy numbers detected by QM-PCR. Current human genomic mapping data indicates that an oncogene, DEK, is centrally placed within this minimal region. Our findings demonstrate the power of QM-PCR to narrow the regions identified by CGH to facilitate identifying specific candidate oncogenes. This also represents the first study identifying DNA copy number increases for DEK in bladder cancer.

Urothelial carcinomas, or transitional cell carcinomas, represent the vast majority of human bladder cancers. Early molecular events associated with superficial bladder cancers include losses on chromosome 9p/9q and mutations in the p53 and retinoblastoma tumor suppressor genes.1,2 The genomic alterations associated with disease progression, defined as the evolution of superficial bladder tumors to higher pathological stages, are complex and poorly understood. Conventional metaphase-based comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) has been used by several groups of investigators to study copy number imbalances in bladder cancer specimens of all stages and grades. These studies have illustrated the genomic complexity of bladder cancer and have identified recurrent regions of DNA copy number increase or high level amplification on several chromosomes including; 1q, 5p, 6p, 8q, 10p, 12q, 17q, and 20q.3–9 These genomic regions are thought to contain oncogenes that may be important in tumor progression.

Metaphase CGH studies have demonstrated copy number gains or high level amplifications at 6p22 in 7 to 55% of urothelial carcinomas, involving primarily the bladder,3–9 but also those arising in the renal pelvis.10 In addition, Bruch et al11 reported 6p22 gains in 6 of 8 bladder cancer cell lines. Recently, Veltman et al12 confirmed the metaphase CGH findings using array-based CGH to show copy number gains at 6p22 in 11 of a series of 41 bladder tumors. The changes at 6p22 in bladder cancer have been associated with high tumor cell proliferative activity,9 tumors of high histological grade that are predominantly invasive,3–9 and patients with distant metastases at initial presentation.8 Based on these findings, 6p22 gains in bladder cancer are well documented and there is good evidence that the acquisition of additional copies of specific genes from this region is associated with aggressive tumor behavior.

Since the resolution of metaphase CGH is limited to 10 to 20 megabases (Mb), techniques with greater mapping resolution such as microarray CGH12, and quantitative-multiplex PCR (QM-PCR) are being used increasingly to precisely map copy number alterations of within subregions of chromosome bands that are thought to be involved in tumorigenesis. Interestingly, copy number aberrations on 6p22 are not unique to bladder cancer.13,14 We (B.L.G. and J.S.) recently identified a novel candidate oncogene, RBKIN, at this location in retinoblastoma (RB).15 The identification of RBKIN was facilitated by the use of QM-PCR to systematically define a minimal critical region within the area of gain previously identified by CGH.16 In the present study, we have used an identical strategy to define a minimal region of recurrent gain within subregions of chromosome band 6p22 in a series of 59 primary urothelial carcinomas of the bladder. In addition, copy number gains identified by QM-PCR were supported by interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) studies using a locus-specific 6p22 probe. Interphase FISH using centromeric probes for chromosome 6 and chromosome 10, the reference chromosome used for the QM-PCR experiments, was used to assess ploidy status and to give insight into potential mechanisms underlying the genomic gain detected by QM-PCR. An analysis of genes that map within the minimal region of gain at 6p22 indicate that the DEK oncogene is centrally placed, and thus this gene is an important candidate for involvement in the pathogenesis of bladder cancer. This study also provides the first systematic high-resolution map of regions of recurrent genomic gain at chromosome 6p22 in human primary bladder tumors.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Tumor Samples

Fresh tissue samples were collected from a total of 70 bladder tumors from 63 patients (37 males and 26 females with mean ages of 57.0 (range, 44 to 87) years and 65.1 (range, 45 to 86) years, respectively. Forty-seven of the patients were from the University Health Network (UHN) in Toronto, Ontario and the remaining 18 samples were derived from the bladder cancer clinical program based in Laval, Quebec. The protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the University Health Network and informed consent was obtained from each patient. Tumors were pathologically staged according to the TNM staging system for bladder cancer17 and graded using the system recommended by the International Society of Urological Pathologists.18 Thirty-five of the samples were obtained from transurethral resection of bladder tumor specimens (TURBTs) and 35 were obtained from radical cystectomy specimens. No samples were taken from tumors of patients who had received pre-operative radiation treatment or systemic chemotherapy. Only urothelial (transitional cell) carcinomas were included in the analysis. Frozen sections were obtained from all samples entered into the UHN bladder tumor tissue bank. Specifically, only samples in which tumor represented at least 75% of the total surface area (relative to stroma) on the frozen section were banked. Samples meeting the above criteria were then placed in RNA later (Ambion, Austin, TX) for 12 to 24 hours at 4°C. High molecular weight genomic DNA was bulk-extracted following standard digestion of the tissue with proteinase K and subsequent extraction with phenol:chloroform.19

We isolated DNA from a total of 70 tumors that represented all stages and histological grades. Specifically, the stage distribution of the tumors was 11 pTa, 11 pT1, and 48 pT2–4. The grade distribution was 8 low grade and 54 high grade. Eleven of the 70 tumors from which we took samples were excluded, leaving 59 tumors for the final analysis. Seven of these (2 pTa and 5 pT2–4) were excluded due to poor quality or insufficient quantities of DNA. The other four tumors (all pT2–4) were excluded following review of final pathology reports that were based on histological assessment of all of the resected tissue in the TURBT specimens or the whole tumor in the cystectomy specimens. Three of these were poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinomas and the fourth was a moderately poorly differentiated primary adenocarcinoma of urachal type.

Quantitative Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction (QM-PCR)

We used the same nine sequence tagged sites (STS) from NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/sts/) used previously in our analysis of copy number alterations of 6p in retinoblastoma.15 These STS’s span 16 Mb between 6p21.3–6p23.1 and the PCR product from each primer pair is 200 bp or more. As before, we used the STS marker P4HA1 (WI-7221) on human 10q21 as an internal control. Published metaphase CGH data indicates that every chromosome arm, including 10q, may potentially show copy number aberrations in bladder cancer. However, an analysis of pooled CGH data from 237 bladder tumors determined that copy number aberrations on 10q21 were relatively infrequent.20 In each reaction, we amplified three of the 6p22 STS markers, the 10q21 internal control and normal male 2-copy DNA as a diploid reference control. Each set of PCR reactions also included the validated retinoblastoma external controls (RB1950 copy number 3.9, consistent with isochromosome 6p, and RB1925 copy number 2.1, consistent with no copy number gain) described previously.15

The reactions were carried out in triplicate for each STS marker in every tumor. All forward primers for the STS markers were labeled with the fluorescent dye Cy5.0 (Integrated DNA Technologies Inc.). PCR reactions were performed in a total reaction volume of 20 μl containing 150 ng of template genomic DNA, 2 to 4 pmol of each primer, 1X Taq polymerase buffer, 200 μmol/L dNTPs, and 2 units of Taq polymerase (Amersham). The templates were amplified for only 18 cycles to maintain the linearity of PCR product generation. The PCR conditions included the hot-start method with an initial denaturing step at 94°C for 10 minutes. This was followed by 18 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 40 seconds), annealing (59°C for 32 seconds) and extension (72°C for 30 seconds) using a PTC 100 thermal cycler (M & J Research, Watertown, MA). The PCR products were resolved on a 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel using the VGI Micro-Gene Clipper sequencer (Visible Genetics Incorporated, Toronto, Canada). The areas under all STS marker peaks were measured using Gene Objects 3.1 software (VGI). These values were used to calculate the ratio of the area under the curve of each 6p22 STS marker to that of the 10q21 internal control marker which provided calibration as the 2-copy reference standard in all experiments.

Threshold ratio copy number values used to identify bladder tumors with 6p22 gain were derived from previously published QM-PCR determinations performed on a large series of retinoblastoma tumors (Figure 1A).15 In our previous study, the mean copy numbers for 18 retinoblastoma tumors consistent with contiguous gain of 6p due to acquisition of isochromosome 6p [i(6p)] resulted in copy number ratio values that ranged from 4.3 to 5.1 for all markers except RH-122450, which showed a higher mean value of 7.1. Since i(6p) typically results in four copies of 6p, these ratios were considerably elevated when compared to the combined mean ratio values for 20 retinoblastoma tumors with two copies of 6p which had a range of 2.1 to 2.3 for all 6p markers. The mean threshold ratio value used to assign 6p gain in the bladder tumors was a copy number of ≥2.4, based on our retinoblastoma data. Specifically, this value was determined by comparing the copy number distribution curves of retinoblastoma tumors within the 2-copy and >2-copy data sets. The threshold value represents the basal copy number at which the number of samples in the overlapping upper tail of the 2-copy data set is equal to the number of samples in the lower tail of the >2-copy data set (with copy number values of 2.3 to 2.4 for all of the 6p markers). Contiguous STS markers showing the greatest frequency of genomic gain defined the minimal region of 6p gain. The mean of the relative copy numbers for each STS marker in the bladder samples was tested for the likelihood of being the same as the retinoblastoma 2-copy data using a t-test with two samples assuming unequal variances.

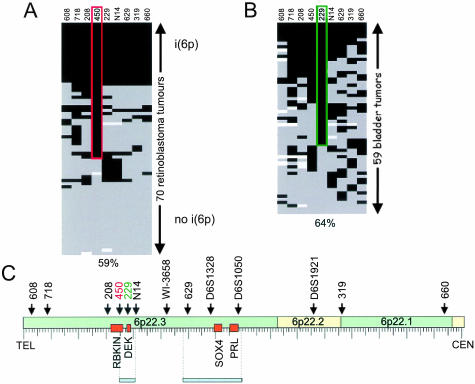

Figure 1.

Scores for 1-copy (white), 2-copy (gray) or genomic gain (black) of STS markers for 70 retinoblastoma tumors (A)14 and 59 bladder tumors (B). The most frequent genomic gain in bladder cancer was 64% for marker 229 (green box) with 56% for marker 450, in contrast to retinoblastoma where the most frequent genomic gain was 59% for marker 450 (red box) and 46% for marker 229. One retinoblastoma with i(6p) and one with no genomic gain were tested simultaneously with the bladder samples as external controls. C: Distribution across the 16.0-Mb region on chromosome 6p22 covered by the nine STS markers used in our study and four markers studied by Bruch et al.11 Four candidate oncogenes in the region are indicated by orange boxes (RBKIN, DEK, S0X4, and PRL). (STS marker abbreviations: 608 – SHGC-130608; 718 – RH113718; 208 – WI-19208; 450– RH122450; 229 – STS-X624229; N14 – A009N14; 629 – WI-22629; 319 – STS-U60319; 660 – WI-660.)

Confirmation of Gain at 6p22 by Interphase Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization

Three representative bladder tumors showing increased copy number by QM-PCR within the minimal region of gain of 6p22 were assessed by interphase FISH methods.21 The 6p22 specific single copy genomic probe was prepared from BAC clone 686D16, (obtained from the RPCI human BAC library 11), and directly labeled with Spectrum Orange dUTP (Vysis Inc., Downers Grove, IL), by nick translation. High hybridization efficiency and specificity were confirmed by performing FISH on normal lymphocyte metaphase preparations. Tissue sections were de-paraffinized by soaking in xylene and ethanol, each for three 8-minute intervals, and then pre-treated with 1 mol/L sodium thiocyanate at 80°C for 8 minutes. Protein digestion was carried out for 22 minutes at 45°C, in a solution of 0.5% pepsin in 0.85% saline, followed by several washes with 2X SSC, and then dehydration through an ethanol series. The probe was denatured for 10 minutes at 75°C and a second denaturation step was performed together with the tissue section for 12 minutes at 80°C. After overnight hybridization at 37°C, a series of washes was carried out at 45°C, including three in 50% formamide/2X SSC, two in 2X SSC, and one in 0.1% Tween-20/4X SSC. Nuclei were counter-stained with DAPI (Vectashield; Vector Laboratories). The number of signals present in 200 non-overlapping nuclei was counted. Lymphocyte nuclei residing within the same tissue sections served as an internal 2-copy control, and copy number increases were noted when ≥3 spots per nucleus were consistently observed in intact tumor nuclei. In addition, sections of normal prostate tissue served as a 2-copy external control. Normal urothelium in the sections with urothelial carcinoma was not used as a 2-signal internal control due to the possibility of scattered malignant cells being implanted within the urothelium adjacent to the tumor.22,23

Assessment of Numerical Changes by Interphase FISH Using Centromeric Probes for Chromosomes 6 and 10 as Ploidy Markers

Interphase FISH, using directly labeled Vysis CEP probes (Vysis Inc.) for chromosomes 6 (spectrum orange) and 10 (spectrum green), was performed on 5-μm unstained paraffin sections from representative bladder tumors. Adjacent hematoxylin and eosin sections were used for guidance. Paraffin pretreatment and the FISH procedure itself were performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. Dual-probe hybridization was carried out. Preliminary experiments were conducted to establish optimal hybridization efficiencies and background fluorescence levels. For each probe, 200 non-overlapping, intact tumor nuclei were counted. Only slides showing hybridization in at least 80% of tumor cells were counted. The number of signals was scored as 1, 2, 3, 4, or more than 4 per nucleus. Nuclei from stromal elements in the sections were easily distinguished from tumor nuclei on the basis of nuclear size and contour and were not scored. Due to truncation of nuclei, artifactual loss of signals is expected. As such, we applied conservative criteria to detect any true numeric changes of significance.24 Briefly, chromosomal gains were assigned when more than 10% of the nuclei had more than 2 signals. Chromosomal losses were assigned when more than 50% of the nuclei had 0 or 1 signal per nucleus. Tetraploidy was assumed when both chromosomes that were investigated showed signal gains of up to 4.

Statistical Analyses

The median relative copy number values (with inter-quartile ranges) from the triplicate QM-PCR measurements on each sample were calculated for the each 6p22 STS marker for stage pTa, pT1, pT2, pT3, and pT4 tumors. The odds ratios, with 95% confidence intervals, were then calculated to assess the relationship between relative copy number and pathological stage.

Results

Sublocalization of the Minimal Region of Recurrent Gain in Urothelial Carcinoma of the Bladder on 6p22 to 0.5 Mb

We compared the bladder tumor data for each marker to the 20 retinoblastoma tumors established to be 2-copy (Figure 1A). For each marker, the probability that the overall bladder data set represented 2-copy was very small (P = 0.006 for STS-X64229, for example). We assigned to each tumor a relative copy number score as follows; 1-copy for values <1.2, 2-copy for values ≤1.2 and <2.4, and genomic gain for values ≥2.4. No criteria were established to distinguish copy number gains from high level amplifications. Graphic display of the copy scores for each sample for each marker allowed us to place the bladder samples in a hierarchy of contiguous genomic gain (Figure 1B). The marker STS-X64229 showed the highest frequency of genomic gain, involving 38 of 59 (64%) tumors. The contiguous markers flanking STS-X64229, RH122450, and A009N14, showed copy number gains in fewer tumors at 33 of 59 (56%) and 26 of 59 (45%) respectively. Contiguous gain was present for all markers in only four tumors, for RH122450 and A009N14 in 14 of 59 (24%), for RH122450 and STS-X64229 in 25 of 59 (42%), and for STS-X64229 and A009N14 in 19 of 59 (32%) of the tumors. In comparison to the previously published data on retinoblastoma (Figure 1A), relatively few bladder tumors (Figure 1B) showed contiguous genomic gain at all nine 6p markers (4 of 59) or 2 copy for all nine markers (2 of 59).

The minimal region of genomic gain was found to lie between RH122450 and A009N14 around the focal hotspot for copy number gain at STS-X64229, spanning a genomic distance of 0.5 Mb (Figure 1C). Although the highest frequency of genomic gain was seen with marker STS-X64229, the adjacent marker RH122450 showed relative copy numbers >4 for 13 tumors, while STS-X64229 was >4 copy in only four tumors.

Tumor Stage and Grade and Relative Copy Number on Chromosome 6p22

Table 1 summarizes the median relative copy number values for each of the nine 6p STS’s spanning the region of interest according to pathological stage with the respective odds ratios (with 95% confidence intervals). Table 1 shows that there was no significant association between copy numbers at any of the nine STS’s and pathological stage. This includes the marker STS-X64229, which resides in the center of the minimal region of gain identified by QM-PCR. There was also no difference in the stage distribution for tumors showing copy number gains at STS-X64229 compared to tumors that did not. Similarly, there was no association between histological grade and 6p22 copy number (data not shown).

Table 1.

Summary of Relative Copy Numbers Determined by QM-PCR by STS Marker with Respect to Tumour Pathologic Stage

| STS marker (6p21.3-6p23.1) | pTa* (n = 9) | pT1 (n = 11) | pT2 (n = 22) | pT3 (n = 14) | pT4 (n = 3) | OR (95% CI)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHGC-130608 | 2.4 (2.0, 2.5)‡ | 2.3 (1.4, 3.3) | 2.3 (1.9, 3.1) | 2.5 (2.1, 3.2) | 1.7 (1.7, 1.7) | 1.33 (0.75, 2.35) |

| RH113718 | 2.7 (1.9, 3.0) | 2.8 (1.8, 3.1) | 2.4 (2.0, 3.8) | 2.3 (1.9, 2.8) | 1.9 (1.7, 2.0) | 0.83 (0.49, 1.38) |

| WI-19208 | 1.8 (1.6, 2.4) | 2.4 (1.7, 2.9) | 2.4 (1.9, 2.8) | 2.0 (1.9, 2.3) | 2.1 (1.8, 2.2) | 1.46 (0.77, 2.79) |

| RH122450 | 2.5 (2.4, 2.7) | 2.9 (2.1, 4.2) | 2.5 (2.1, 4.0) | 2.3 (2.1, 3.4) | 2.4 (2.0, 2.8) | 0.93 (0.63, 1.36) |

| STS-X64229§ | 2.7 (2.0, 2.9) | 3.2 (2.0, 3.5) | 2.7 (2.1, 3.0) | 2.8 (2.2, 3.2) | 3.0 (1.6, 3.1) | 1.18 (0.68, 2.04) |

| A009N14 | 2.1 (2.0, 2.5) | 2.2 (1.7, 2.8) | 2.6 (2.1, 3.1) | 2.2 (2.1, 3.3) | 2.4 (2.2, 2.8) | 1.27 (0.78, 2.05) |

| WI22629 | 2.1 (2.0, 2.6) | 2.4 (2.2, 2.9) | 2.3 (2.1, 3.0) | 2.4 (2.0, 2.7) | 2.6 (2.0, 3.1) | 1.20 (0.60, 2.41) |

| STS-U60319 | 2.1 (2.0, 2.4) | 2.2 (1.9, 3.8) | 2.1 (1.8, 2.4) | 2.6 (2.2, 3.2) | 1.9 (1.4, 2.7) | 0.91 (0.55, 1.51) |

| WI-660 | 2.1 (1.8, 2.2) | 2.9 (2.1, 3.3) | 2.6 (2.0, 2.8) | 2.2 (1.9, 2.9) | 3.1 (2.3, 3.3) | 0.97 (0.55, 1.72) |

pT = pathologic stage;

odds ratio (95% confidence interval);

relative copy number values presented as the median values with interquartile ranges (median value (interquartile range));

STS-X64229 (bold) resides in the centre of the minimal region of focal gain determined by QM-PCR.

Confirmation of Copy Number Increases Detected by QM-PCR Using Interphase FISH

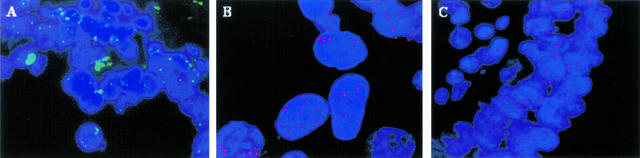

Three representative bladder tumors showing copy number gains at STS-X64229 by QM-PCR were selected for interphase FISH experiments. Figure 2A shows the results of interphase FISH with the RP11–686D16 probe on sections of benign prostate epithelium. As expected, the normal prostate epithelium showed only 2 signals per nucleus. In contrast, Figure 2B shows the results of interphase FISH with the same probe on a bladder tumor in which a mean of 4.5 signals (range, 0 to 11, with >50% of nuclei showing 5 to 11 signals) are seen within each nucleus. In addition, one of the three bladder tumors we selected for FISH was a high-grade, muscle-invasive tumor with focal papillary architecture. In the papillary areas there were numerous lymphocytes adjacent to the tumor cells that covered the papillary fronds. The lymphocytes in these areas would be expected to act as a 2-signal internal control. Indeed, the lymphocytes showed the expected 2 signals per nucleus while the adjacent tumor cells showed 3 signals per nucleus (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Interphase FISH analysis on paraffin-embedded tissue sections, using a BAC probe (RP11–686D16) specific for the region 6p22.3–24.3, either indirectly detected by FITC-Avidin (A) or directly labeled with spectrum orange (B and C). A: Prostate cancer with no amplification of 6p. B: Bladder tumor showing copy number gain of 6p. An average of 4.5 signals per nucleus was seen (range, 0 to 11, with 50% of the nuclei showing 5 to 11 signals). C: Lymphocytes in the core of a papillary frond in a bladder tumor serve as an internal 2-copy control. The tumor nuclei covering the papillary frond show copy number gain of 6p, with an average of 3 signals per tumor cell nucleus.

Assessment of Numerical Changes by Interphase FISH Using Centromeric Probes for Chromosomes 6 and 10 as Ploidy Markers

Six representative tumors were selected for interphase FISH analysis using centromere probes for chromosomes 6 and 10. This analysis was designed to provide some insight into potential mechanisms of the relative copy number gains on chromosome 6p22 that were detected by QM-PCR. Five of the six tumors had relative increases in copy number at STS-X64229, the marker in the center of the minimal region of gain as identified by QM-PCR. The sixth tumor showed no such increase. These probes provided an assessment of aneusomy for chromosome 6, the chromosome of interest in the QM-PCR analyses, and chromosome 10, which was the reference chromosome against which the relative copy numbers on chromosome 6p22 were determined. These results are considered to represent a surrogate for ploidy status of these two chromosomes.

Table 2 shows the mean centromere numbers for chromosomes 6 and 10 in relation to the relative copy numbers for STS-X64229 as measured by QM-PCR. It is apparent from this analysis of a subset of representative tumors that there are gross numerical chromosomal changes consistent with aneusomy or polyploidy in these bladder tumors. There was no single specific type of change that was a consistent finding across all of these bladder tumors. In particular, the data indicate that there is no apparent complete deletion of chromosome 10 that would be expected to compromise the observation of increased relative copy number at chromosome 6p22 measured by QM-PCR.

Table 2.

Assessment of Numerical Changes by Interphase FISH Using Centromeric Probes for Chromosomes 6 and 10 as Ploidy Markers

| Tumour | Mean centromere no. chromosome 6 | Mean centromere no. chromosome 10 | Relative copy by QM-PCR for STS-X64229 |

|---|---|---|---|

| BT-13 | 3 | 3, 4 and 5 | 2.75 (gain) |

| BT-15 | 2 | 2 | 3.47 (gain) |

| BT-27 | 1 | 3 | 2.19 (no gain) |

| BT-43 | 3 | 1 | 3.40 (gain) |

| BT-47 | 3 and 4 | 1 | 5.73 (gain) |

| BT-51 | 3 | 3 | 3.96 (gain) |

Shown are the results of interphase FISH experiments using centromeric probes for chromosomes 6 and 10 that were performed on a subset of six representative tumours. The mean centromere numbers are listed along with the relative copy number (mean of triplicate QM-PCR measurements) for each tumour at STS-X64229, which resides in the centre of the minimal region of focal gain on chromosome 6p22. As indicated in the Table, five of the tumours showed copy number gain and one showed no gain at this STS marker (based on the QM-PCR criteria defined in Materials and Methods).

Discussion

The molecular events that accompany the development and progression of bladder cancer, defined as evolution to higher stage disease, are poorly understood. There is no accepted molecular pathway that is analogous to the adenoma-carcinoma sequence that has been elucidated for colonic adenocarcinoma.25 In addition, studies to date have not identified molecular markers that will reliably predict which superficial bladder cancers will recur as highly aggressive muscle-invasive tumors. Metaphase-based CGH has been used by several groups of investigators to identify recurrent regions of genomic gain on several chromosomes in bladder cancer3–9. These regions are thought to be likely candidates for the location of oncogenes important in tumor progression.

In bladder cancer, gains at 6p22 have been reported in invasive tumors, in 7 to 55% of cases, and in 6 of 8 cell lines derived from invasive bladder tumors.3–9,11 Significant associations have been found between 6p22 gain and high histological grade,5,8 however, the relationship with stage and progression is unclear.3,5,4,6 Richter et al4 found that no patients with superficially invasive tumors (stage pT1) with 6p22 gains progressed to muscle-invasive disease (stage pT2) over 52 months. In contrast, Bruch et al3 found 6p22 gains in 9% of pT1 cases and 29% of pT2 tumors. Further evidence of an association with aggressive bladder cancer is provided by Prat et al,8 who reported that 6p22 gain was the only CGH change associated with patients who initially presented with metastases. In addition, Simon et al26 concluded that 6p22 gains occurred as late events in high-stage lesions and Tomovska et al9 found that 6p22 gain was the only CGH change in bladder cancer to independently predict high proliferative activity in the tumor cells. All of the aforementioned observations provide compelling evidence that copy number increases at 6p22 in bladder cancer are associated with aggressive tumor behavior. However, the identity of the amplified genes within this region has not been determined and a mechanism concerning their role in bladder cancer progression has not been developed.

Since there are over 600 genes in the 20-Mb region identified by CGH at 6p22, it is not realistic to select candidate genes for further study. Thus, QM-PCR of STS’s mapping to contiguous subregions of 6p22 provides an ideal method to further narrow the region of common genomic gain. Recently, we have shown that QM-PCR identifies genomic loss (1 copy versus 2 copy) for exons and the promoter of RB1 with greater than 95% accuracy for 23 of 27 exons.27 This approach has also been used by our group to define a 0.6-Mb hotspot at 6p22 in retinoblastoma.15 This work led to the identification of RBKIN, a novel candidate oncogene.15 Through the application of QM-PCR to DNA from 59 primary urothelial carcinomas, we were able narrow the 6p gain to a 0.5-Mb region located just centromeric to RBKIN.

As detected in our previous studies of genomic gain in retinoblastoma,15 there appear to be at least two mechanisms leading to DNA copy number increases at 6p22 in bladder cancer. Firstly, many retinoblastoma tumors and a few bladder tumors (Figure 1, A and B), show contiguous genomic gain around the STS’s showing increased copy number. This suggests that a cytogenetic aberration, such as the i(6p) documented in retinoblastoma, may account for the genomic gain in some bladder tumors. This is indirectly supported by our interphase FISH data using centromeric probes for chromosomes 6 and 10. Specifically, the results in Table 2 suggest that there are unbalanced translocations involving chromosome 6p22, with or without involvement of the centromere for chromosome 6, which may be involved in the copy number gains. These translocations may, in turn, result in the formation of i(6p). To definitively establish whether these mechanisms are involved in the relative copy number increases at 6p22 requires additional work that is beyond the scope of the present study.

More commonly in bladder cancer, the markers flanking the minimal region of gain appear to retain relative copy number levels close to diploidy, suggesting acquisition of focal low copy number amplification within a subregion of 6p22. The gain of non-continguous markers evident in the bladder data, in contrast to the retinoblastoma data, may reflect the relative purity of tumor samples. Retinoblastoma grows in the eye with virtually no admixture of non-neoplastic cells, whereas bladder tumors invade normal tissues. As such, normal cells will inevitably be present in bladder cancer samples.

While our study is the first to undertake a detailed assessment of DNA copy number for 6p22 in primary human bladder tumors using QM-PCR, similar investigations have been carried out in bladder cancer cell lines. Using eight different cell lines derived from invasive bladder cancers, Bruch et al11 used a combination of cytogenetic methods, overlapping YAC contigs, FISH, and semi-quantitative PCR with microsatellite markers to narrow the region of gain at 6p22 down to a common 2-Mb region. Human genome data available at that time identifed eight candidate genes within this region. Using quantitative PCR, the SOX4 gene was amplified in six cell lines showing 6p22 gain by CGH. However, Northern blotting and RT-PCR failed to demonstrate increased SOX4 expression in any of the six cell lines.

Based on current human genome map data, Figure 1C shows the position of the 0.5-Mb minimal region of recurrent gain we identified in the bladder tumors relative to the 2.0-Mb region identified in the cell lines by Bruch et al.11 Our identified region does not overlap with that found in the cell lines and is located telomeric to it. The difference in localization may be related to differences between primary tumors and cell lines and/or differences in the technology used to identify the minimal regions of gain in each study. In the array-based CGH analyses of Veltman et al,12 clones showing the highest level of copy number gain included the gene for the transcription factor E2F3. According to the most current mapping information, the critical region we found by QM-PCR is located slightly telomeric to E2F3. However, both sit within 1.5 Mb of each other which was the approximate resolution of the array used by Veltman et al.12

On review of current human genome map data, we were able to identify one candidate oncogene, DEK, within the 0.5-Mb region of recurrent gain (Figure 1C). In silico analysis (http://cgap.nci.nih.gov/Tissues/VirtualNorthern) of the relative abundance of DEK transcripts indicates increased expression of DEK in genitourinary tract cancer cell lines, including those derived from bladder cancers (NIH MGC 53 and NIH MGC 93). Interestingly, the in silico findings with respect to DEK and bladder cancer have recently been substantiated by cDNA expression microarray studies by Sanchez-Carbayo et al28 who demonstrated DEK overexpression in primary bladder tumor samples.

Our findings are the first to implicate gene copy number increases for the DEK oncogene in the pathogenesis of bladder cancer, although we were unable to show that this was correlated with stage or progression. In their expression microarray studies, Sanchez-Carbayo et al28 reported that DEK overexpression was associated with superficial bladder cancers and was one of several genes that could be used to discriminate superficial from invasive tumors. Taken together with our QM-PCR data, it is likely that the overexpression of DEK in superficial tumors is the result of an increase in gene copy number and/or amplification. The overexpression of DEK in superficial as opposed to invasive tumors reported by Sanchez-Carbayo et al28 would suggest these copy number gains are an early event in the development of bladder cancer, as opposed to a marker of disease progression. This idea would go against metaphase CGH data suggesting that 6p22 gains or amplifications are late events.26 The reason for this apparent disagreement is not clear, however it may be related to the fact that only 15 tumors were studied by Sanchez-Carbayo et al.28 As is shown in Table 1, we did not find a statistically significant relationship between copy number and stage or grade at any of the STS’s spanning 6p22, including STS-X64229 at the center of the minimal region of gain. This result may be a reflection of the relatively small number of tumors studied and the skewing of our sample set toward tumors of high grade and pathological stage. Interestingly, Veltman et al12 reported a similar lack of association between 6p22 copy number and stage and grade in their array-based CGH analyses.

The product of the DEK oncogene is a 43-kD nuclear protein. While its physiological function is not known, DEK may influence the topology of DNA in chromatin29,30 and regulate specific post-splicing steps in gene expression.31 The role of DEK in the pathogenesis of disease is also unknown. Anti-DEK autoantibodies are found in the serum of patients with rheumatic and inflammatory disorders.32 The t(6;9) translocation found in subsets of acute myelogenous leukemia involves fusion of DEK with the nucleoporin CAN. The link between the DEK-CAN fusion protein and leukemogenisis is not clear, however, t(6;9) is thought to be a marker of poor prognosis.33 DEK is included in a cluster of genes with increased expression that is associated with the unfavorable 11q23 deletion found in some chronic lymphocytic leukemias.34 Increased DEK expression has also been linked to hepatocellular carcinogenesis35 and malignant brain tumor formation.36

QM-PCR generates relative, as opposed to absolute, copy numbers based on a comparison with a control marker on another chromosome that is taken to be diploid (chromosome 10q21 in our case). It is recognized that invasive bladder cancers quite commonly have both aneuploid and polyploid chromosome numbers37, a fact that is confirmed by our interphase FISH data using the centromeric probes for chromosomes 6 and 10 (Table 2). We recognize that this represents a potential limitation to our choice of QM-PCR methodology to study bladder tumors. In addition, metaphase CGH data indicates that there is no chromosome arm in bladder cancer not subject to potential copy number changes, including a low frequency of copy number losses at 10q.3–9,20 We originally developed the 10q probe for use in retinoblastoma, as chromosome 10 is spared from copy number changes in this type of tumor.16 We reasoned that the relatively low frequency of copy number changes reported for 10q in bladder cancer20 would render the 10q21 marker as good as any other reference probe we could have selected. Given the dependence of the QM-PCR assay on the 2-copy internal control, we acknowledge that copy number aberrations at 10q21 in any of the bladder tumors may have influenced the copy number values at the 6p22 STS’s measured by QM-PCR. Despite these potential limitations, we were still able to refine the minimal region of focal gain to a 0.5-Mb unit that contains a gene, DEK, that has recently been shown to be overexpressed in human bladder tumors28. Our interphase FISH findings (Figure 2) using the locus-specific 6p22 probe lend additional support to our QM-PCR data.

CGH studies have detected copy number increases on chromosome 6p22 in several human malignancies other than retinoblastoma and bladder cancer. These include chondrosarcoma, non-small cell lung cancer, testicular tumors, endometrial carcinomas of endometrioid type, and ocular melanoma.13 As with bladder cancer, oncogenes at 6p in these other tumors have not been definitively identified. Our observation that RBKIN is not in the exact same location as the critical region of gain in bladder cancer suggests that several different genes important in diverse array of human malignancies, including E2F3 and DEK, may reside at or near 6p22. The observation that not all bladder cancers have copy number changes on 6p22 would support the theory of Czerniak et al7 that bladder cancer may progress through a variety of different molecular pathways, such that some progression events may be dependent on increased expression of genes on 6p22 and others may be independent of gene expression at this locus.

In summary, we have used QM-PCR to identify a 0.5-Mb minimal region of recurrent gain on chromosome 6p22 in a series of primary bladder tumors and have identified an oncogene, DEK, within it. While DEK has been shown to be overexpressed in bladder tumors,28 the role of this putative oncogene in bladder cancer pathogenesis and progression needs to be explored in greater detail.

Acknowledgments

We thank the University Health Network Department of Pathology Academic Enrichment Fund and the University Health Network Division of Urology Academic Enrichment Fund for providing the support for these studies.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Andrew J. Evans, M.D., Ph.D., FRCPC, Staff Pathologist and Assistant Professor, Department of Pathology, University Health Network, Princess Margaret Hospital, Room 4–313, 610 University Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M5G 2M9. E-mail: andrew.evans@uhn.on.ca.

Supported by University of Toronto Dean’s Fund for New Faculty, University Health Network Pathology Associates Academic Enrichment Fund, and University Health Network Urology Associates.

References

- Spruck CH, III, Ohneseit PF, Gonzalez-Zulueta M, Esrig D, Miyao N, Tsai YC, Lerner SP, Schmutte C, Yang AS, Cote R. Two molecular pathways to transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Cancer Res. 1994;54:784–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosin MP, Cairns P, Epstein JI, Schoenberg MP, Sidransky D. Partial allelotype of carcinoma in situ of the human bladder. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5213–5216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruch J, Wohr G, Hautmann R, Mattfeldt T, Bruderlein S, Moller P, Sauter S, Hameister H, Vogel W, Paiss T. Chromosomal changes during progression of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder and delineation of the amplified interval on chromosome arm 8q. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1998;23:167–174. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2264(199810)23:2<167::aid-gcc10>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter J, Wagner U, Schraml P, Maurer R, Alund G, Knonagel H, Moch H, Mihatsch MJ, Gasser TC, Sauter G. Chromosomal imbalances are associated with a high risk of progression in early invasive (pT1) urinary bladder cancer. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5687–5691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter J, Beffa L, Wagner U, Schraml P, Gasser TC, Moch H, Mihatsch MJ, Sauter G. Patterns of chromosomal imbalances in advanced urinary bladder cancer detected by comparative genomic hybridization. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:1615–1621. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65750-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter J, Jiang F, Gorog JP, Sartorius G, Egenter C, Gasser TC, Moch H, Mihatsch MJ, Sauter G. Marked genetic differences between stage pTa and stage pT1 papillary bladder cancer detected by comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2860–2864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czerniak B, Li L, Chaturvedi V, Ro JY, Johnston DA, Hodges S, Benedict WF. Genetic modeling of human urinary bladder carcinogenesis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000;27:392–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prat E, Bernues M, Caballin MR, Egozcue J, Gelabert A, Miro R. Detection of chromosomal imbalances in papillary bladder tumors by comparative genomic hybridization. Urology. 2001;57:986–992. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)00909-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomovska S, Richter J, Suess K, Wagner U, Rozenblum E, Gasser TC, Moch H, Mihatsch MJ, Sauter G, Schraml P. Molecular cytogenetic alterations associated with rapid tumor cell proliferation in advanced urinary bladder cancer. Int J Oncol. 2001;18:1239–1244. doi: 10.3892/ijo.18.6.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigola MA, Fuster C, Casadevall C, Bernues M, Caballin MR, Gelabert A, Egozcue J, Miro R. Comparative genomic hybridization analysis of transitional cell carcinomas of the renal pelvis. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2001;127:59–63. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(00)00426-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruch J, Schulz WA, Haussler J, Melzner I, Bruderlein S, Moller P, Kemmerling R, Vogel W, Hameister H. Delineation of the 6p22 amplification unit in urinary bladder carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4526–4530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veltman JA, Fridlyand J, Pejavar S, Olshen AB, Korkola JE, DeVries S, Carroll P, Kuo WL, Pinkel D, Albertson D, Cordon-Cardo C, Jain AN, Waldman FM. Array-based comparative genomic hybridization for genome-wide screening of DNA copy number in bladder tumors. Cancer. 2003;63:2872–2880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knuutila S, Bjorkqvist AM, Autio K, Tarkkanen M, Wolf M, Monni O, Szymanska J, Larramendy ML, Tapper J, Pere H, El Rifai W, Hemmer S, Wasenius VM, Vidgren V, Zhu Y. DNA copy number amplifications in human neoplasms: review of comparative genomic hybridization studies. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1107–1123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larramendy ML, Tarkkanen M, Valle J, Kivioja AH, Ervasti H, Karaharju E, Salmivalli T, Elomaa I, Knuutila S. Gains, losses, and amplifications of DNA sequences evaluated by comparative genomic hybridization in chondrosarcomas. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:685–691. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Pajovic S, Duckett A, Brown VD, Squire JA, Gallie BL. Genomic amplification in retinoblastoma narrowed to 0.6 megabase on chromosome 6p containing a kinesin-like gene, RBKIN. Cancer Res. 2002;62:967–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Gallie BL, Squire JA. Minimal regions of chromosomal imbalance in retinoblastoma detected by comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2001;129:57–63. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(01)00427-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, Fritz AG, Balch CM, Haller DG, Morrow M, editors. New York, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Publishing; American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual. (ed 6) 2002 [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JI, Amin MB, Reuter VR, Mostofi FK. The World Health Organization/International Society of Urological Pathology consensus classification of urothelial (transitional cell) neoplasms of the urinary bladder: Bladder Consensus Conference Committee. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:1435–1448. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199812000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Russell DW, editors. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Molecular CloningA Laboratory Manual. (ed 3) 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer AA, Simon R, Desper R, Richter J, Sauter G. Tree models for dependent copy number changes in bladder cancer. Int J Oncol. 2001;18:349–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty BG, Mai S, Squire J. FISH (Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization). United Kingdon: Oxford University Press; 2002:pp 196–197. [Google Scholar]

- Simon R, Richter J, Wagner U, Fijan A, Bruderer J, Schmid U, Ackermann D, Maurer R, Alund G, Knonagel H, Rist M, Wilber K, Anabitarte M, Hering F, Hardmeier T, Schonenberger A, Flury R, Jager P, Fehr JL, Schraml P, Moch H, Mihatsch MJ, Gasser T, Sauter G. High-throughput tissue microarray analysis of 3p25 (RAF1) and 8p12 (FGFR1) copy number alterations in urinary bladder cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4514–4519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadl-Elmula I, Gorunova L, Mandahl N, Elfving P, Lundgren R, Mitelman F, Heim S. Cytogenetic monoclonality in multifocal uroepithelial carcinomas: evidence of intraluminal tumour seeding. Br J Cancer. 1999;81:6–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Maghrabi J, Vorobyova L, Toi A, Chapman W, Zielenska M, Squire JA. Identification of numerical chromosomal changes detected by interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization in high-grade prostate intraepithelial neoplasia as a predictor of carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126:165–169. doi: 10.5858/2002-126-0165-IONCCD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61:759–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon R, Eltze E, Schafer KL, Burger H, Semjonow A, Hertle L, Dockhorn-Dworniczak B, Terpe HJ, Bocker W. Cytogenetic analysis of multifocal bladder cancer supports a monoclonal origin and intraepithelial spread of tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:355–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter S, Vandezande K, Chen N, Zhang K, Sutherland J, Anderson J. Sensitive and efficient detection of RB1 gene mutations enhances care for retinoblastoma families. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:253–269. doi: 10.1086/345651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Carbayo, Socci ND, Lozano JJ, Li W, Charytonowicz E, Belbin TJ, Prystowsky MB, Ortiz AR, Childs G, Cordon-Cardo C. Gene discovery in bladder cancer progression using cDNA microarrays. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:505–516. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63679-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappes F, Burger K, Baack M, Fackelmayer FO, Gruss C. Subcellular localization of the human proto-oncogene protein DEK. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:26317–26323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100162200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexiadis V, Waldmann T, Andersen J, Mann M, Knippers R, Gruss C. The protein encoded by the proto-oncogene DEK changes the topology of chromatin and reduces the efficiency of DNA replication in a chromatin-specific manner. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1308–1312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarvey T, Rosonina E, McCracken S, Li Q, Arnaout R, Mientjes E, Nickerson JA, Awrey D, Greenblatt J, Grosveld G, Blencowe BJ. The acute myeloid leukemia-associated protein DEK, forms a splicing-dependent interaction with exon-product complexes. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:309–320. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.2.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Wang J, Kabir FN, Shaw M, Reed AM, Stein L, Andrade LE, Trevisani VF, Miller ML, Fujii T, Akizuki M, Pachman LM, Satoh M, Reeves WH. Autoantibodies to DEK oncoprotein in human inflammatory disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:85–93. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200001)43:1<85::AID-ANR11>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaguchi H, Nagata K, Yamamoto K, Fujikawa I, Kobayashi M, Eguchi M. Establishment of a novel human myeloid leukaemia cell line (FKH-1) with t(6;9)(p23;q34) and the expression of dek-can chimaeric transcript. Br J Haematol. 1998;102:1249–1256. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aalto Y, El Rifa W, Vilpo L, Ollila J, Nagy B, Vihinen M, Vilpo J, Knuutila S. Distinct gene expression profiling in chronic lymphocytic leukemia with 11q23 deletion. Leukemia. 2001;15:1721–1728. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondoh N, Wakatsuki T, Ryo A, Hada A, Aihara T, Horiuchi S, Goseki N, Matsubara O, Takenaka K, Shichita M, Tanaka K, Shuda M, Yamamoto M. Identification and characterization of genes associated with human hepatocellular carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4990–4996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroes RA, Jastrow A, McLone MG, Yamamoto H, Colley P, Kersey DS, Yong VW, Mkrdichian E, Cerullo L, Leestma J, Moskal JR. The identification of novel therapeutic targets for the treatment of malignant brain tumors. Cancer Lett. 2000;156:191–198. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(00)00462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg AA, Berger CS. Review of chromosome studies in urological tumors: II. cytogenetics and molecular genetics of bladder cancer. J Urol. 1994;151:545–560. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]