Abstract

Membranous (M) cells are specialized epithelial cells of the Peyer’s patches that sample antigens from the gut lumen, thereby enabling the host to respond immunologically. Recent studies suggest that this transport can be up-regulated within hours by de novo formation of M cells from enterocytes. To test this hypothesis, we used an in vivo model and induced the transcytosis of tracers in Peyer’s patches by application of Streptococcus pneumoniae R36a into the gut lumen. Using cell-type-specific markers, we quantified M cells in the Peyer’s patch domes, lymphocytes associated with M cells, and the transport rate for experimentally applied microbeads after 3 hours of exposure to R36a. The transport of latex microbeads was significantly increased by +131% in the R36a-treated patches as compared to buffer controls (P < 0.001). While in controls, each M cell was associated with 2.05 ± 0.64 lymphocytes, a significant increase (+55.1%; P < 0.001) was determined in the R36a-treated patches. However, no statistical difference was detected in the percentage of M cells in the dome epithelia (46.0 ± 4.6% versus 45.5 ± 3.8%). It is concluded that bacteria-induced up-regulation of particle transport in Peyer’s patch domes is due to an increased transport rate of the M cells, but not to a de novo formation of M cells. The data support the hypothesis that M cells represent a separate cell lineage that does not derive from enterocytes on the domes.

The contact of the immune system with foreign antigens and potential pathogens in the gut lumen is mediated by specialized antigen-transporting epithelial cells, the membranous (M) cells, which are present in the dome epithelium of Peyer’s patches in various mammals, including humans.1,2 M cells endocytose antigenic matter at their apical membrane, transport it in vesicles to their basolateral membrane, and exocytose it to intraepithelial spaces containing lymphocytes.3 This antigen sampling is of critical relevance for early recognition of pathogenic microorganisms to initiate specific immune reactions in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT). It has been proposed that, in the future, this transport route can be used for the delivery of drugs and vaccines, which are selectively targeted to the M-cell surface4; however, several uptake studies with experimentally applied tracers revealed that the capacity of the M-cell-mediated transport largely varies among different species, individuals, Peyer’s patches, domes, and individual M cells.2 To use this transport system for therapeutical applications, a predictable and reliable transport capacity would be of great advantage. This could be achieved by an induced increase in the number of M cells in the domes and/or up-regulation of their transport capacity.

In a recently published animal model, Streptococcus pneumoniae strain R36a was used as a challenging agent to experimentally up-regulate particle transport in Peyer’s patches of rabbits.5,6 The bacteria were instilled into the ileal lumen over Peyer’s patches for 1 to 3 hours, and latex microbeads instilled for another 45 minutes served as tracers to determine the transport capacity. In these experiments, S. pneumoniae R36a induced a significant increase in the transport rate for microbeads as compared to controls, and a reorganization of the brush border structure in the dome epithelium, as detected by scanning electron microscopy.6 The authors concluded that dome enterocytes can rapidly switch to fully operational M cells and thus postulate that S. pneumoniae R36a induces the de novo formation of M cells from enterocytes within a few hours.5 Such a short-term induction of M cells would be of high relevance because it is a matter of current debate whether M cells are functionally modified enterocytes, or represent a separate cell type of the gut epithelium.3,7–10 The first hypothesis is supported by cell-culture experiments in which B lymphocytes (or even soluble factors produced by cultured lymphocytes) induced M-cell-like cells from Caco-2 monolayer cells.11–13 In contrast, our own in vivo studies as well as those of other groups imply that 1) the formation of M cells is restricted to specialized dome-associated crypts, 2) early stages of differentiating epithelial cells in these crypts are predetermined as M cells, and 3) M cells do not develop from differentiated enterocytes.8,14–16 A short-term de novo induction of M cells from dome epithelial enterocytes, as suggested by Borghesi et al5 and Meynell et al,6 favored the first hypothesis and was in contrast with the concept that M cells are a separate cell line.

To prove the hypothesis that the formation of M cells can be induced by instillation of S. pneumoniae into ileal loops, we repeated the experiments of Meynell et al6 and quantified the different cell types in the dome epithelium. In contrast to those of other species, the M cells of rabbits can easily be detected immunohistochemically, since they contain large amounts of the intermediate filament vimentin.17,18 Functional experiments have confirmed that, in the domes, solely these vimentin-positive cells transcytose experimentally applied tracers and thus represent the M cells.19 In the present study, we used immunohistochemical triple-labeling to quantify M cells and enterocytes in the dome epithelium and to compare S. pneumoniae-treated patches with buffer-treated controls. To ascertain that the pneumococci affected the dome epithelium in a manner similar to that previously reported, the transepithelial transport of microbeads was used as a functional read-out system, and the immigration of lymphocytes into the dome epithelium was quantified as well. To determine whether the polysaccharide capsule, which is regarded a major virulence factor of pneumococci,20 interferes with the effect of the bacteria on the dome epithelium, the rough S. pneumoniae strain R36a and the smooth strain R36A were applied to different patches in the same individuals. Based on the results, we here introduce a new theory on the differentiation of M cells, which attempts to integrate the diverging findings and interpretations currently discussed.

Materials and Methods

Bacteria and Microbeads

Stock cultures of S. pneumoniae R36a (rough phase; ATCC 27336) and R36A (smooth phase; ATCC 11733) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Bacteria were grown in brain heart infusion broth in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C for 16 hours without agitation. Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation and diluted in potassium-phosphate buffer. The lumen of each isolated ileal loop was filled with 1 ml of this buffer containing ∼5 × 107 bacteria (experimental loops) or with buffer only (control loops). The transport rates for particles were determined using a suspension of green fluorescent latex microbeads (0.5-μm diameter; Polysciences, Eppelheim, Germany) at a dilution of 1:20 in PBS.

Animal Experiments and Tissue Preparation

Five adult male New Zealand rabbits (3.5 to 3.8 kg) were anesthetized with 100 mg ketamin (Alprecht, Aulendorf, Germany) i.m., 5 mg midazolam (Curamed, Karlsruhe, Germany) i.v., 10 mg Propofol-Lipuro 1% (Braun, Melsungen, Germany), and 150 mg Temgesic i.v. (Essex, Munich, Germany). After intubation, the rabbits inhaled a mixture of oxygen and isoflurane (Abbot GmbH, Wiesbaden, Germany) for 4 hours or longer.

The abdominal cavity was opened and isolated ileal loops of 20- to 30-mm in length, each containing a Peyer’s patch, were prepared in situ without disturbing the blood supply. In each rabbit, one or two loops were filled with R36a suspension, one or two loops with R36A suspension, and one loop with buffer (control). In total, 13 experimental loops and 5 control loops were prepared and examined. After incubation under anesthesia for 3 hours, the lumen of the loops was rinsed with pre-warmed buffer, and filled with 1 ml of latex microbead suspension. The loops were removed after 45 minutes, briefly rinsed in saline to eliminate larger aggregates of fluorescent particles in the lumen and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. The animals were sacrificed by an intravenous injection of T61 (Hoechst, Frankfurt/M., Germany). The animal experiments were approved by the local government of Lower Saxony, Germany (TS-No. 604–42502-94/719 and 509–42502-98/131).

Immunohistochemistry

Cryosections (5-μm thick) were fixed in a mixture of methanol and acetone for 10 minutes at −20°C and transferred to PBS. The sections were incubated with a solution containing a monoclonal anti-cytokeratin 8 antibody (clone 4.1.18; Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) in PBS at a dilution of 1:50 at 37°C for 1 hour. After rinsing in PBS (3 times for 10 minutes), bound primary antibody molecules were detected using a goat anti-mouse antiserum conjugated to the green fluorescent dye AlexaFluor 488 (dilution 1:100, 37°C, for 1 hour; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). After rinsing, rabbit M cells were detected using a monoclonal anti-vimentin antibody (clone V9) conjugated to the red fluorescent dye Cy3 (Sigma-Aldrich, Munich, Germany). To prevent binding of this antibody to free F(ab) arms of the secondary antibody applied in the previous step, the V9-Cy3 antibody solution was supplemented with 50% mouse normal serum (Dako, Hamburg, Germany). Nuclei were stained using the blue fluorescent dye bisbenzimide Hoechst 33258 (0.1 μg/ml in PBS for 1 hour; Sigma-Aldrich). Controls were performed by replacing the primary antibodies with buffer and by omitting the secondary antibody.

Fluorescence Microscopy

Cryosections were examined using a fluorescence microscope equipped with separate filter sets for blue, green, and red fluorescence (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). From each Peyer’s patch, 10 to 12 slides, each containing 3 to 5 sections, were examined; typically, 4 to 8 domes were present in an individual section. Using the following criteria, a total of 191 domes were selected for photography and quantitation: section plane running perpendicular to the dome epithelium, homogeneous labeling, and histologically intact epithelium. Quantitation of microbead uptake was performed in domes that contained particles in both lumen and domes. Domes that did not contain any particles had probably been separated from the lumen by mucus and were therefore excluded from the countings.

Under standardized conditions (same investigator, magnification on the negatives 100:1, identical exposure time), separate black-and-white negatives were taken in the three corresponding fluorescence channels for each dome (T-max 400 film; Kodak, Rochester, USA). The photographic negatives were digitized using a standard PC equipped with a Nikon LS-1000 35 mm film scanner (Nikon, Düsseldorf, Germany). Corresponding data sets of the three different fluorescences were re-combined in digital RGB color images using Photoshop software (version 6.0; Adobe, Edinburgh, UK).

Quantitation and Statistics

Cell types could easily be distinguished in the digital three-color images according to their labeling pattern: cytokeratin+ vimentin+ M cells, cytokeratin+ vimentin− enterocytes, and cytokeratin− vimentin− lymphocytes (Figure 1). Cell counts were performed on the flanks of the domes where mature M cells 21,22 are associated with clusters of lymphocytes (region between brackets in Figure 1a). More basal regions of the dome epithelium, defined by the presence of immature M cells and the absence of clustered lymphocytes, were excluded from the quantitation, as well as the tips of the domes where both M cells and lymphocytes are rare. Because of their extremely bright dot-like fluorescence, latex microbeads could easily be identified in the sections. The number of microbeads within the epithelium and the number of M cells in the same epithelial segment was determined for each flank of a dome, so that the average number of microbeads taken up per M cell could be calculated.

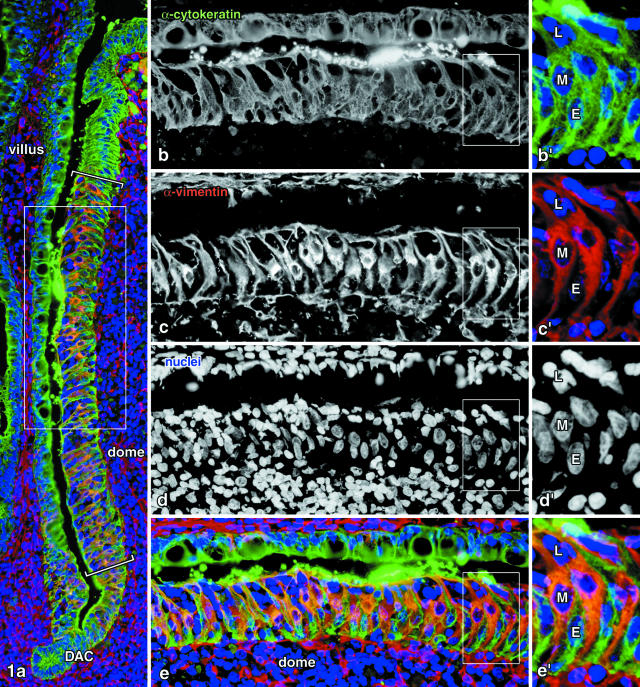

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical localization of cell types in the dome epithelium of rabbit Peyer’s patches. Quantitation was performed on the flanks of the domes where mature M cells occur (region between brackets in a), while the dome-associated crypts (DAC) and the tips of the domes (upper quarter of a) were excluded. The frames in a and in b to e indicate higher magnifications shown in b to e and in b’ to e’, respectively. Epithelial cells were labeled by an anti-cytokeratin antibody and detected in the green fluorescence channel (b and b’). Vimentin is known to be co-expressed with cytokeratins in M cells and shown in the red channel (c and c’); nuclei were stained in blue (d and d’). Cytokeratin+ vimentin+ double-positive cells thus represent the M cells (M), cytokeratin+ vimentin− cells are enterocytes (E), and double-negative nuclei in the dome epithelium are lymphocytes (L) in M-cell pockets. Magnifications: a, ×200; b to e, ×350; b’ to e’, ×690.

The distribution of the different parameters was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Since microbead counts were not normally distributed, the data are displayed as medians and ranges, and statistically tested using the Mann-Whitney-U rank sum test. Boxplot-whisker diagrams (Figure 3) show median values as thick lines, the lower and upper quartile value as boxes, and the extreme values as the whiskers. The remaining data showed normal distributions, thus the Student’s t-test was used, and the data are displayed as means and standard deviations. Statistics were performed using SPSS software (version 10.0; SPSS, Munich, Germany).

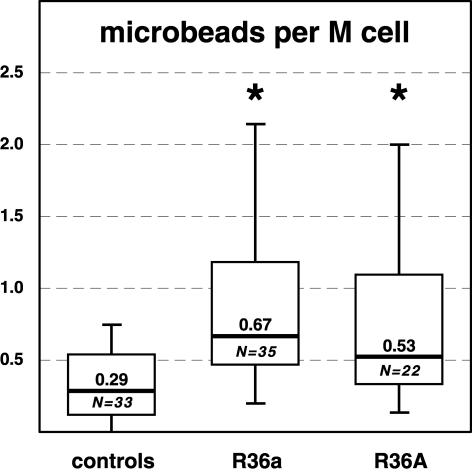

Figure 3.

Quantitation of the uptake of latex microbeads in the flanks of the Peyer’s patch domes. S. pneumoniae R36a, R36A, or buffer only (controls) were instilled into the ileal lumen for 3 hours, and latex microbeads were instilled for the next 45 minutes. The median number of particles per M cell (thick line) is significantly increased (* P < 0.05) in the R36a- and R36A-treated patches, as compared to controls. The boxplot-whisker diagram shows that both bacterial strains up-regulate particle transport in the dome epithelium, and that this is due to an increased transport capacity of the M cells. N is the number of domes investigated per group. Boxes represent the lower and upper quartile values, and extreme values are displayed as whiskers.

Results

Identification of Cell Types

The epithelium on the flanks of the Peyer’s patch domes consists of M cells, enterocytes and lymphocytes, while other cell types, such as goblet cells and entero-endocrine cells, are almost absent. Nuclei that were surrounded by cytokeratin+ and vimentin+ double-positive cytoplasm were identified as belonging to M cells (Figure 1). Cytokeratin+, but vimentin− cells were identified as enterocytes. Unlabeled cells (cytokeratin− vimentin− double-negative) which were associated with M cells and lay within the cytokeratin+ band of the epithelium were counted as lymphocytes in M-cell pockets. A total of 17403 cells was counted in the three groups. The vast majority of these cells could readily be classified, as intermediate forms (eg, cells containing only small amounts of vimentin and/or cytokeratins) were virtually absent. Nuclei that could not unequivocally be categorized comprised 0.10% in the R36a group (8 of 7676), 0.26% in the R36A (16 of 6182), and 0.31% in the controls (11 of 3545).

Uptake of Microbeads

Aggregates of fluorescent latex microbeads lay in the gut lumen and adhered to the epithelial surface (Figure 1b). Single disseminated particles were found within the epithelium of most of the domes (Figure 2, a to c). Microbead uptake was restricted to regions containing vimentin+ cells (ie, the flanks and the bases of the domes). However, numerous vimentin+ cells were found in all three groups that had not taken up any fluorescent microbeads. The dome epithelia of Peyer’s patches treated with R36a contained 0.67 microbeads per M cell (median, range 0.2 to 2.27; Ndomes = 35), R36A-treated domes contained 0.53 microbeads per M cell (median, range 0.14 to 3.67; Ndomes = 22), and those of the control group 0.29 (median, range 0.0 to 2.53; Ndomes = 33) (Figure 3).

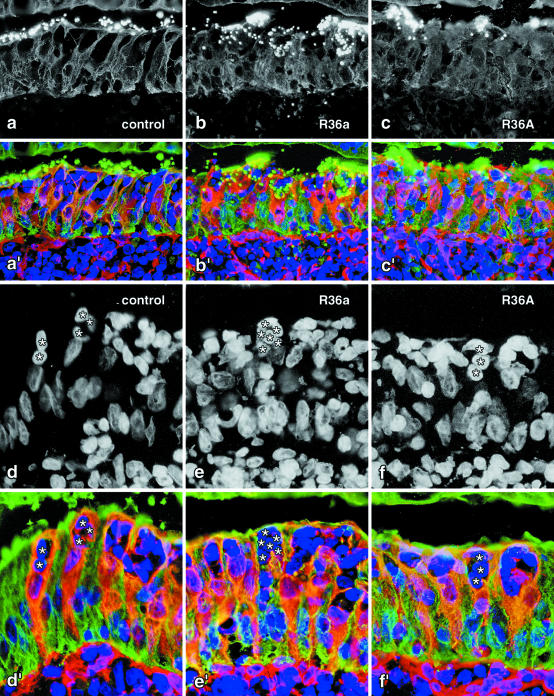

Figure 2.

a to c: Uptake of microbeads by M cells after instillation of S. pneumoniae R36a and R36A into the gut lumen for 3 hours. Fluorescent microbeads, 0.5-μm in diameter, are visible as bright dots in the green channel, which also contains the cytokeratin labeling (a to c). Three-color fluorescence of enterocytes, M cells and lymphocytes (a’ to c’) allows the flank region of the domes to be identified and the average number of particles per M cell to be determined quantitatively. The three images selected illustrate a low uptake rate (a and a’ in a control patch), a high rate (b and b’ in a R36a-treated patch), and a moderate particle uptake rate (c and c’ in a R36A-treated Peyer’s patch). d to f: The numbers of M-cell associated lymphocytes (some of which are marked by asterisks in d to f) and M cells (cytokeratin+ vimentin+, orange in d’ to f’) were determined for each flank so that the average number of lymphocytes per M-cell section profile could be calculated. The three images selected illustrate a low (d and d’), high (e and e’), and moderate number of lymphocytes in M-cell pockets (f and f’). Magnifications: a to c’, ×380; d to f’, ×570.

The R36a-treated patches had taken up significantly greater numbers of particles than the controls (+131%; P < 0.005). The same tendency and significance was determined for R36A-treated patches versus controls (+83%; P < 0.005; Figure 3). No statistical difference in the number of ingested microbeads was found between the smooth (R36A) and rough (R36a) S. pneumoniae strains (P = 0.27).

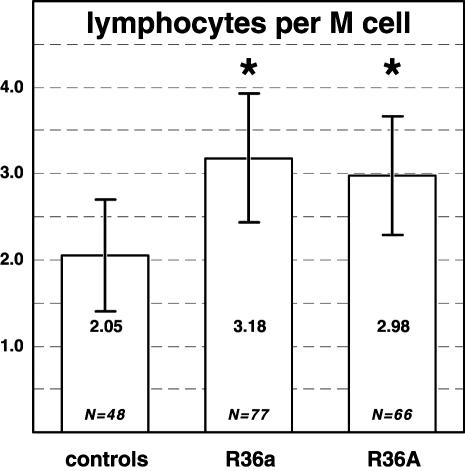

Number of M-Cell-Associated Lymphocytes

In total, 9765 lymphocytes associated with M cells were counted (Figure 2, d to f). The dome epithelia of R36a-treated Peyer’s patches contained 3.18 ± 0.75 lymphocytes per M-cell section profile (4495 lymphocytes beneath 1438 M cells) (Figure 4). Domes treated with R36A contained 2.98 ± 0.68 lymphocytes per M cell (3524 lymphocytes beneath 1202 M cells). In control patches not treated with bacteria, each M cell was associated with only 2.05 ± 0.64 lymphocytes (1746 lymphocytes beneath 819 M cells). The numbers of lymphocytes per M cell in R36a- and R36A-treated domes was significantly greater than those in the controls (P < 0.001).

Figure 4.

The numbers of lymphocytes associated with M cells and that of M cells was counted for each dome, so that the quotient gives the average number of lymphocytes per M-cell section profile. After 3 hours of incubation with S. pneumoniae, the number of lymphocytes increases significantly as compared to buffer controls (* P < 0.01). This indicates that lymphocytes migrate into the epithelium under influence of the bacteria. Bars represent means ± SD; N is the number of domes investigated.

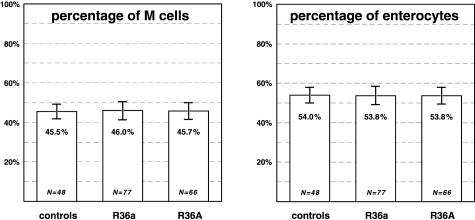

Percentage of M Cells and Enterocytes

In total, the M cells (cytokeratin+ vimentin+) comprised 45.8 ± 4.3% (3459 cells), and the enterocytes 53.8 ± 4.3% (4144 cells) of all epithelial cells in the domes (7638 cells). The percentage of M cells in the domes of R36a-treated patches (46.0 ± 4.6%; Ndomes = 77) did not significantly differ (P = 0.525) from that in control patches (45.5 ± 3.8%; Ndomes = 48) (Figure 5a). The percentage of M cells in the domes of R36A-treated patches (45.7 ± 4.3%; Ndomes = 66) likewise did not significantly differ from that in controls (P = 0.746). In addition, variance analysis revealed that the two experimental groups were statistically equal in the percentage of M cells (P < 0.05). Quantitation and statistical analysis of the percentages of enterocytes in the domes revealed comparable results with no statistical difference between the experimental groups and the control group (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

The epithelial cells in the domes, ie, M cells and enterocytes, were identified according to their labeling pattern in fluorescence microscopy and quantified for each flank of the domes. Although particle uptake is up-regulated significantly (see Figure 3), the percentages of M cells and enterocytes did not differ between the bacteria-treated groups and the controls. The data show that there is no shift from dome epithelial enterocytes to M cells within 3 hours of treatment with the bacteria. Bars represent means ± SD; N is the number of domes investigated.

Discussion

The results show 1) that a functional effect of S. pneumoniae R36a on the transport capacity of the Peyer’s patch dome epithelium was successfully reproduced in our experiments, 2) that lymphocytes migrated into the dome epithelium, but that 3) the number of M cells in the dome epithelium, as determined by a reliable histochemical marker, remained constant. This indicates that the function of M cells, ie, transepithelial transport, can be up-regulated, but that de novo formation of M cells within a few hours does not occur under this in vivo situation. The findings raise a number of interesting questions concerning the generation of M cells, their definition, and the cross-correlation of M-cell markers with transport function and ultrastructure. In the following, a new theory will be developed which attempts to integrate the differing views and findings on the formation of M cells.

The differentiation pathway of intestinal M cells has been thoroughly studied in the past few years using various animal models, M-cell markers, locations of GALT, and cell culture systems.8,11,15,22,23 It is of critical importance to understand the processes involved in the formation of M cells in the dome epithelia, since a reliable and effective targeting of M cells is a prerequisite for M-cell-mediated drugs and vaccines to be developed in the future.4,24 It is generally accepted that M cells, together with all other epithelial cells of the domes, derive from proliferating stem cells in the dome-associated crypts.9,10,22 While the newly formed epithelial cells migrate from the crypts toward the base of the dome epithelium, some of them gradually acquire characteristics of M cells.8,15,16,22,23,25 At the upper flanks of the domes, mature M cells are found which typically engulf clusters of lymphocytes, actively transport antigen, possess a characteristic ultrastructure, and, in the rabbit, contain large amounts of vimentin. However, the key question on the developmental pathway from crypt stem cell to mature M cell is still controversial: are M cells induced from differentiated enterocytes on the domes or do M cells and enterocytes represent distinct cell lines which separate from each other early in the crypts?

The lifespan of an individual M cell is about 4 days, and it takes about 2 days for a newly generated crypt cell to differentiate and migrate to the flanks of the domes.23,26 Therefore, two situations for the induction of M cells are conceivable: 1) a long-term induction of M cells that takes 2 days or longer, which could be due to a shift in the percentage of M cells produced in the dome-associated crypts; 2) a short-term induction within a few hours, a time span in which the population of epithelial cells on the domes should remain largely unchanged, so that newly formed M cells could derive from differentiated enterocytes only.

The experimental setting used in the present study and previously described by Borghesi et al5,27 and Meynell et al6 investigates a short-term effect of S. pneumoniae R36a on M cells using functional, structural, and histochemical characteristics as read-out parameters. Our results demonstrate that the transport capacity for microbeads significantly increases after a 3-hour treatment with pneumococci. This finding extends the results previously published, since we determined the uptake rate per M cells (and not only per dome), so that possible variations in the absolute numbers of M cells could not have affected our measurements. Nevertheless, the differences observed in our experiments (up to +131%) showed the same tendency and statistical significance as described previously6; however, no statistical difference was detected between the effect of the rough R36a strain and the smooth R36A strain, making it unlikely that the polysaccharide capsule, which represents a major virulence factor,20 is involved in the effect on the dome epithelium. It could be speculated that soluble factors produced by pneumococci in the gut lumen during the 3-hour incubation induce the enhanced transport capacity of M cells.

A remarkable effect of the bacteria on the domes is further seen in a significant increase in the number of lymphocytes present in the dome epithelium. Since 3 hours are not sufficient to complete proliferation of mammalian cells, the data imply that lymphocytes were attracted to the dome epithelium and migrated into the pockets under M cells. From these quantitative results, we conclude that our experimental setting only marginally differs from that described by Borghesi et al27 and Meynell et al.6 These authors determined a number of ultrastructural features to identify M cells (eg, the SEM aspect of the brush border) and concluded that S. pneumoniae R36a induces de novo formation of M cells from dome enterocytes.5 In the present study, we replaced these qualitative criteria by quantitative immunohistochemistry to determine possible variations in the numbers of the different cell types. Our results clearly show that the increase in particle transport seen under influence of S. pneumoniae R36A and R36a is not accompanied by an increase of marker-positive cells (consistently about 46% of all epithelial cells in the dome flanks). We conclude that, in the short-term situation, the function of M cells can be up-regulated, but that no de novo formation of M cells occurs.

It could, however, be objected that the read-out criteria used for the identification of M cells critically affect the measurements. Since still no universal marker for M cells, independent of species and location is available, various definitions of M cells are in use. While initially, M cells were identified ultrastructurally,1 more recent studies introduced species-specific histochemical markers that allow us to detect M cells in light microscopy.18,28,29 In addition, numerous functional studies identified M cells according to ingested and accumulated tracers or microorganisms.2 Cross-correlations of the different methods used to identify M cells in dome epithelia can be summarized as follows: 1) all cells that transport tracers are marker-positive, but not all marker-positive cells in the domes transport the tracer at a defined moment (present study); 2) all cells having a typical ultrastructure are marker-positive, but not all marker-positive cells possess a typical ultrastructure (eg, immature M cells). From these two relations we deduce that marker-positive cells form a superset with respect to both structurally and functionally defined M cells. This obviously applies to vimentin-positive cells in rabbit GALT, cytokeratin-18-rich cells in the small intestine of pigs, as well as α-L-fucose-bearing cells in the Peyer’s patches of mice.18,28,29 Nevertheless, it must be noted that a number of other markers, eg, certain lectins binding to M cells in the intestines of mice and rabbits,15,25,30,31 do not label all M cells at an equal intensity or even identify M-cell subsets only.

Based on the present data and on those available in the literature, we hypothesize that a defined proportion of crypt epithelial cells is pre-determined as M cells (eg, 46% in rabbit Peyer’s patches; some 10% to 25% in the Peyer’s patches of mice). Using suitable histochemical markers, all cells of this population can be detected as soon as they enter the dome epithelium. Nevertheless, ultrastructure and transport function may identify subpopulations only and thus result in smaller counts for M cells. Certain stimuli, such as S. pneumoniae R36a (present study) or S. typhimurium,32 are capable of inducing the formation of “typical” M cells from pre-determined M cells within a few hours, so that these gain a larger basolateral pocket, a thinner apical cytoplasm, a less-developed terminal web, a reduced activity of alkaline phosphatase, and an enhanced transcytotic activity. In this case, the number of M cells that have a typical, elaborate ultrastructure and/or actively transport tracers could appear to increase within hours.

On the contrary, an in vivo study in mouse Peyer’s patches showed that epithelial cells that enter the dome, but derive from ordinary crypts, do not develop to M cells.8 This indicates that differentiated enterocytes on the domes do not have the capacity to form M cells, a finding which is in accordance with the results of the present study. This conclusion is further supported by the observation that the histochemical M-cell markers mentioned previously produce clear-cut separations of labeled and unlabeled cells (present study).16,18,25,33,34 In contrast, some ultrastructural studies depicted intermediate forms,5 which, in the context of the model proposed here, represent cells of the M-cell line not sufficiently stimulated to acquire a typical ultrastructure and transport activity. We therefore predict that short-term stimulation of M cells is limited to the percentage of pre-determined M cells (ie, 46% in rabbit Peyer’s patches). In contrast, long-term stimulation might affect the proportion of pre-determined M cells in the crypts and thus could actually increase the amount of potential M cells present.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Garlisch, K.-H. Napierski, S. Prange, K. Werner, and P. Zerbe for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. A. Gebert, Institute of Anatomy, University of Lübeck, 23538 Lübeck, Germany, E-mail: gebert@anat.uni-luebeck.de.

Supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Ge647/3–1 and SFB280/C10/C14) and by the University of Lübeck (Schwerpunkt Körpereigene Infektabwehr, C1).

References

- Owen RL, Jones AL. Epithelial cell specialization within human Peyer’s patches: an ultrastructural study of intestinal lymphoid follicles. Gastroenterology. 1974;66:189–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebert A, Rothkötter HJ, Pabst R. M cells in Peyer’s patches of the intestine. Int Rev Cytol. 1996;167:91–159. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61346-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neutra MR, Mantis NJ, Kraehenbuhl JP. Collaboration of epithelial cells with organized mucosal lymphoid tissue. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:1004–1009. doi: 10.1038/ni1101-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiserlian D, Etchart N. Entry sites for oral vaccines and drugs: a role for M cells, enterocytes and dendritic cells? Semin Immunol. 1999;11:217–224. doi: 10.1006/smim.1999.0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghesi C, Taussig MJ, Nicoletti C. Rapid appearance of M cells after microbial challenge is restricted at the periphery of the follicle-associated epithelium of Peyer’s patch. Lab Invest. 1999;79:1393–1401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meynell HM, Thomas NW, James PS, Holland J, Taussig MJ, Nicoletti C. Up-regulation of microsphere transport across the follicle-associated epithelium of Peyer’s patch by exposure to Streptococcus pneumoniae R36a. EMBO J. 1999;13:611–619. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.6.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debard N, Sierro F, Kraehenbuhl JP. Development of Peyer’s patches, follicle-associated epithelium and M cell: lessons from immunodeficient and knockout mice. Semin Immunol. 1999;11:183–191. doi: 10.1006/smim.1999.0174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebert A, Fassbender S, Werner K, Weiβferdt A. The development of M cells in Peyer’s patches is restricted to specialized dome-associated crypts. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:1573–1582. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65410-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti C. Unsolved mysteries of intestinal M cells. Gut. 2000;47:735–739. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.5.735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierro F, Pringault E, Assman PS, Kraehenbuhl JP, Debard N. Transient expression of M-cell phenotype by enterocyte-like cells of the follicle-associated epithelium of mouse Peyer’s patches. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:734–743. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.16481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernéis S, Bogdanova A, Kraehenbuhl JP, Pringault E. Conversion by Peyer’s patch lymphocytes of human enterocytes into M cells that transport bacteria. Science. 1997;277:949–952. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullberg E, Leonard M, Karlsson J, Hopkins AM, Brayden D, Baird AW, Artursson P. Expression of specific markers and particle transport in a new human intestinal M-cell model. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;279:808–813. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte R, Kerneis S, Klinke S, Bartels H, Preger S, Kraehenbuhl JP, Pringault E, Autenrieth IB. Translocation of Yersinia enterocolitica across reconstituted intestinal epithelial monolayers is triggered by Yersinia invasin binding to β1 integrins apically expressed on M-like cells. Cell Microbiol. 2000;2:173–185. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicinski P, Rowinski J, Warchol JB, Bem W. Morphometric evidence against lymphocyte-induced differentiation of M cells from absorptive cells in mouse Peyer’s patches. Gastroenterology. 1986;90:609–616. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(86)91114-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebert A, Posselt W. Glycoconjugate expression defines the origin and differentiation pathway of intestinal M cells. J Histochem Cytochem. 1997;45:1341–1350. doi: 10.1177/002215549704501003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelouard H, Sahuquet A, Reggio H, Montcourrier P. Rabbit M cells and dome enterocytes are distinct cell lineages. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2077–2083. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.11.2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebert A, Hach G, Bartels H. Co-localization of vimentin and cytokeratins in M-cells of rabbit gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT). Cell Tissue Res. 1992;269:331–340. doi: 10.1007/BF00319625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jepson MA, Mason CM, Bennett MK, Simmons NL, Hirst BH. Co-expression of vimentin and cytokeratins in M cells of rabbit intestinal lymphoid follicle-associated epithelium. Histochem J. 1992;24:33–39. doi: 10.1007/BF01043285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jepson MA, Simmons NL, Savidge TC, James PS, Hirst BH. Selective binding and transcytosis of latex microspheres by rabbit intestinal M cells. Cell Tissue Res. 1993;271:399–405. doi: 10.1007/BF02913722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AlonsoDeVelasco E, Verheul AF, Verhoef J, Snippe H. Streptococcus pneumoniae: virulence factors, pathogenesis, and vaccines. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:591–603. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.4.591-603.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmedtje JF. Lymphocyte positions in the dome epithelium of the rabbit appendix. J Morphol. 1980;166:179–195. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051660205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bye WA, Allan CH, Trier JS. Structure, distribution, origin of M cells in Peyer’s patches of mouse ileum. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:789–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla DK, Owen RL. Cell renewal and migration in lymphoid follicles of Peyer’s patches and cecum: an autoradiographic study in mice. Gastroenterology. 1982;82:232–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neutra MR, Frey A, Kraehenbuhl JP. Epithelial M cells: gateways for mucosal infection and immunization. Cell. 1996;86:345–348. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannasca PJ, Giannasca KT, Falk P, Gordon JI, Neutra MR. Regional differences in glycoconjugates of intestinal M cells in mice: potential targets for mucosal vaccines. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:G1108–G1121. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1994.267.6.G1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MW, Jarvis LG, King IS. Cell proliferation in follicle-associated epithelium of mouse Peyer’s patch. Am J Anat. 1980;159:157–166. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001590204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghesi C, Regoli M, Bertelli E, Nicoletti C. Modifications of the follicle-associated epithelium by short-term exposure to a non-intestinal bacterium. J Pathol. 1996;180:326–332. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199611)180:3<326::AID-PATH656>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MA, Jepson MA, Simmons NL, Booth TA, Hirst BH. Differential expression of lectin-binding sites defines mouse intestinal M cells. J Histochem Cytochem. 1993;41:1679–1687. doi: 10.1177/41.11.7691933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebert A, Rothkötter HJ, Pabst R. Cytokeratin 18 is an M cell marker in porcine Peyer’s patches. Cell Tissue Res. 1994;276:213–221. doi: 10.1007/BF00306106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MA, Jepson MA, Simmons NL, Hirst BH. Differential surface characteristics of M cells from mouse intestinal Peyer’s patches and caecal patches. Histochem J. 1994;26:271–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebert A, Hach G. Differential binding of lectins to M cells and enterocytes in the rabbit cecum. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1350–1361. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90139-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savidge TC, Smith MW, James PS, Aldred P. Salmonella-induced M-cell formation in germ-free mouse Peyer’s patch tissue. Am J Pathol. 1991;139:177–184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MA, Jepson MA, Hirst BH. Lectin binding defines and differentiates M cells in mouse small intestine and caecum. Histochem Cell Biol. 1995;104:161–168. doi: 10.1007/BF01451575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelouard H, Reggio H, Mangeat P, Neutra M, Montcourrier P. Mucin-related epitopes distinguish M cells and enterocytes in rabbit appendix and Peyer’s patches. Infect Immun. 1999;67:357–367. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.357-367.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]