Abstract

Ubiquitin is thought to be a stress protein that plays an important role in protecting cells under stress conditions; however, its precise role is unclear. Ubiquitin expression level is controlled by the balance of ubiquitinating and deubiquitinating enzymes. To investigate the function of deubiquitinating enzymes on ischemia-induced neural cell apoptosis in vivo, we analyzed gracile axonal dystrophy (gad) mice with an exon deletion for ubiquitin carboxy terminal hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1), a neuron-specific deubiquitinating enzyme. In wild-type mouse retina, light stimuli and ischemic retinal injury induced strong ubiquitin expression in the inner retina, and its expression pattern was similar to that of UCH-L1. On the other hand, gad mice showed reduced ubiquitin induction after light stimuli and ischemia, whereas expression levels of antiapoptotic (Bcl-2 and XIAP) and prosurvival (brain-derived neurotrophic factor) proteins that are normally degraded by an ubiquitin-proteasome pathway were significantly higher. Consistently, ischemia-induced caspase activity and neural cell apoptosis were suppressed ∼70% in gad mice. These results demonstrate that UCH-L1 is involved in ubiquitin expression after stress stimuli, but excessive ubiquitin induction following ischemic injury may rather lead to neural cell apoptosis in vivo.

The small 76 amino acid protein ubiquitin plays a critical role in many cellular processes, including cell cycle control, transcriptional regulation, and synaptic development.1,2 Although ubiquitin has been identified as a heat shock- and stress-regulated protein in several kinds of cells,3,4 recent studies have shown that ubiquitin promotes either cell survival or apoptosis, depending on the stage of cell development or other cellular factors.5–8 Ubiquitin expression level is controlled by the balance of ubiquitinating enzymes: ubiquitin-activating (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating (E2), ubiquitin-ligase (E3) enzymes, and deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs). DUBs are subdivided into ubiquitin carboxy terminal hydrolases (UCHs) and ubiquitin-specific proteases (UBPs). Mammalian UCHs, UCH-L1, and UCH-L3 are both small proteins of ∼220 amino acids that share >40% amino acid sequence identity.9 However, the distribution of these isozymes is quite distinct in that UCH-L3 is distributed ubiquitously while UCH-L1 is selectively expressed in neuronal cells and in the testis/ovary.9,10 UCH-L1 constitutes ∼5% of the brain’s total soluble protein, which demonstrates a possibility that it plays a major role in neuronal cell function.11 Indeed, UCH-L1 is a constituent of cellular aggregates that are indicative of neurodegenerative disease, such as Lewy bodies in Parkinson’s disease.12 Furthermore, an isoleucine to methionine substitution at amino acid 93 of UCH-L1 is reported in a family with a dominant form of Parkinson’s disease.13 Recently, we found a UCH-L1 gene exon deletion in mice that causes gracile axonal dystrophy (gad), a recessive neurodegenerative disease.14 These examples of neurodysfunction from UCH-L1 mutations in both humans and mice prompted us to investigate the function of UCH-L1 in ischemia-induced neuronal cell apoptosis. For this purpose, we evaluated the extent of ischemic injury in wild-type and gad mice retina. The retina was chosen as a model because it is a highly organized neural tissue. In addition, its layered construction is suitable for analysis of cell type-specific biological response against diverse stimuli.15–18 Here, we show that the absence of UCH-L1 partially prevents ischemia-induced retinal cell apoptosis and propose its possible mechanisms.

Materials and Methods

Animals

We used homozygous gad mice14 and their wild-type littermates between postnatal days 35 and 56. The gad mouse was found in the F2 offspring of CBA and RFM inbred strain mice and has been maintained by brother-sister mating for more than 10 years.19 Mice were maintained and propagated at the National Institute of Neuroscience, National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry (Japan). Experiments using the mice were approved by the Animal Investigation Committee of the Institute. The animals were housed in a room with controlled temperature and fixed lighting schedule. Light intensity inside the cages ranged from 100 to 200 lux. For the analysis of light stress, the pupils were dilated with 0.5% phenylephrinezhydrochloride and 0.5% tropicamide, and the mice were exposed to 800∼1300 lux of white fluorescent light for 30 minutes. Animals for negative controls were dark-adapted for 12 hours, and sacrificed under dim red light.

Immunohistochemistry

Animals were anesthetized with diethylether and perfused transcardially with saline, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer containing 0.5% picric acid at room temperature. The eyes were removed and postfixed overnight in the same fixative at 4°C and embedded in paraffin wax. The posterior part of the eyes were sectioned saggitally at 7-μm thickness through the optic nerve, mounted and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For immunohistochemical staining, the sections were incubated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 10% normal donkey serum for 30 minutes at room temperature. They were then incubated overnight with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against ubiquitin (1:600; Chemicon, Temecula, CA) or mouse monoclonal antibody against UCH-L1 (1:200; Medac, Wedel, Germany). They were then visualized with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA), respectively. The sections were examined by a confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Histology and Morphometric Studies

Ischemia was achieved and the animals were sacrificed as previously described.16,17 Briefly, we instilled sterile saline into the anterior chamber of the left eye at 150 cm H2O pressure for 15 minutes while the right eye served as a non-ischemic control. The animals were sacrificed 1 or 7 days after reperfusion, and eyes were enucleated for histological and morphometric studies. The posterior part of the eyes was sectioned sagittally at 7-μm thickness through the optic nerve, mounted and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Ischemic damage after 7 days was quantified in two ways. First, the thickness of the inner retinal layer (IRL) [from the ganglion cell layer (GCL) to the inner nuclear layer (INL)] was measured with a calibrated reticle at ×80. Second, in the same sections, the number of cells in the GCL was counted from one ora serrata through the optic nerve to the other ora serrata. The changes of the number of ganglion cells after ischemia were expressed in ratio compared with the non-ischemic fellow eyes.

TUNEL Staining

Sections were incubated in 0.26 U/μl TdT in the supplied 1X buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and 20 μmol/L biotinylated-16-dUTP (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) for 60 minutes at 37°C. Sections were washed three times in PBS (pH 7.4) and blocked for 30 minutes with 2% bovine serum albumin in PBS (pH 7.4). The sections were then incubated with FITC-coupled streptavidin (Jackson Immunoresearch), diluted 1:100 in PBS for 30 minutes, and examined with a confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus).

Quantification of Retinal Cell Apoptosis and Caspase Activities

A mouse retina 1 day after ischemia was homogenized in 100 μl PBS containing 1 mmol/L phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride and centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 minutes. A portion of supernatant was used to quantify protein concentration, and the rest was processed for assays. Retinal cell apoptosis was quantified using the Cell Death ELISA kit (Roche). Caspase-1- and caspase-3-like activities were measured using caspase-1 and caspase-3 Colorimetric Assay Kits (Bio-vision, Mountain View, CA), respectively.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blots were performed as previously reported.14 Five micrograms of total protein were loaded per lane. Primary antibodies used were Bcl-2 (1:500), Bcl-xL (1:500), XIAP (1:500) (all from Transduction Laboratories, Franklin Lakes, NJ), phosphorylated cyclic AMP responsive element-binding protein (PCREB) (1:500; Upstate Biotechnology, Waltham, MA) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Blots were further incubated with an anti-mouse or rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (1:10000; Chemicon). The Super Signal detection kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) was used for visualization of immunoreactive bands.

Results

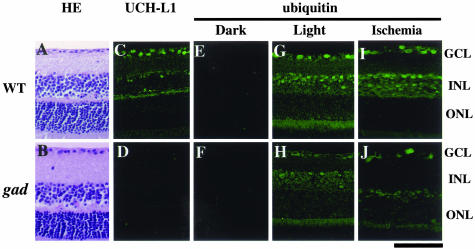

Effect of UCH-L1 on Retinal Structure and Ubiquitin Expression

To determine the effect of UCH-L1 on retinal morphology, we examined the retinal tissue of gad mice with a UCH-L1 gene exon deletion.14 Retinal structure in gad mice (Figure 1B) was normal compared with wild-type mice (Figure 1A). UCH-L1-like immunoreactivity was observed in the ganglion cell layer (GCL) and the inner nuclear layer (INL) in wild-type mice (Figure 1C) but was absent in gad mice (Figure 1D). Since ubiquitin is thought to be a stress protein,1,20 we first examined the effect of the common oxidative stress for eye tissues, light stimuli, on ubiquitin induction.20 Interestingly, ubiquitin was almost absent in both groups of animals, following dark adaptation (Figure 1, E and F). However, light stimuli strongly induced ubiquitin expression in the GCL and INL in wild-type mice (Figure 1G) but its induction level was very low in gad mice (Figure 1H). Ubiquitin expression pattern in wild-type mice was similar to that of UCH-L1 (Figure 1C). We next examined the effect of ischemia, severe oxidative stress,21,22 on ubiquitin induction. As with light stimuli, ischemia induced strong ubiquitin expression in the GCL and INL (Figure 1I) and its induction was suppressed in gad mice (Figure 1J). These results demonstrate that retinal UCH-L1 plays an important role in ubiquitin induction11 and gad mice retina is a useful model to investigate the effects of UCH-L1 on ischemic injury in vivo.

Figure 1.

Functional loss of UCH-L1 decreases light- and ischemia-induced ubiquitin induction in vivo. Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining (A and B), immunostaining of UCH-L1 (C and D), immunostaining of ubiquitin in dark-reared (E and F), light-stressed (G and H) and ischemic (I and J) retina in wild-type (A, C, E, G, and I) and gad (B, D, F, H, and J) mice. Retinal structure is normal (B), but stress-induced ubiquitin induction is reduced (H and J) in gad mice. For the analysis of light stress (G and H), mice were exposed to 800 to 1300 lux of light for 30 minutes. Animals for negative controls were dark-adapted for 12 hours, and sacrificed under dim red light (E and F). Ischemic retina was prepared 1 day after ischemic injury (I and J). Bar, 50 μm.

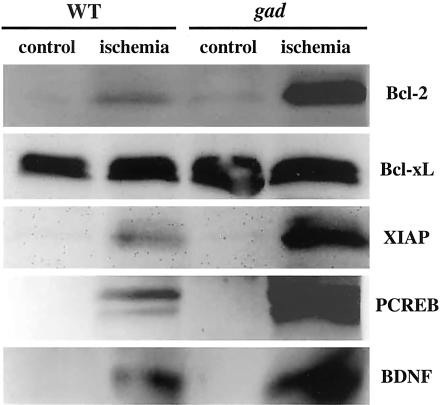

Effect of UCH-L1 on Antiapoptotic and Prosurvival Protein Expressions Following Ischemic Injury

The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway might be involved in non-neural cell apoptosis because this pathway can degradate antiapoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2 and XIAP in vitro.5–8 To determine whether this is true for retinal cell apoptosis in vivo, we examined their protein expression levels in ischemic retinas (Figure 2). Ischemia-induced Bcl-2 protein level in gad mice was substantially higher than that of wild-type mice. Bcl-xL proteins (antiapoptotic member in the Bcl-2 family)23,24 were examined at the same time as a control, but no obvious alternations were noted. On the other hand, XIAP protein25,26 expression was apparently higher in gad mice. In addition to oxidative stress, ischemia induces calcium influx in neurons and triggers phosphorylation of cyclic AMP responsive element-binding protein (CREB).27 PCREB can activate transcription of trophic factor proteins, such as BDNF, by binding to a critical calcium response element.27 Since CREB is degraded by a ubiquitin-proteasome pathway by a phosphorylation-dependent mechanism,28 we hypothesized a similar degradative pathway for CREB in ischemic retina. In wild-type mice, ischemia increased PCREB, but its expression level was much higher in gad mice. Consistent with PCREB up-regulation, BDNF protein expression was also higher in gad mice. Thus, excessive ubiquitin induction after ischemic injury may lead to the degradation of antiapoptotic proteins and suppression of the transcription of prosurvival proteins.5–8,28

Figure 2.

Immunoblot analysis of antiapoptotic and prosurvival proteins after ischemic injury. Five micrograms of total protein were prepared from whole retinas before (control) and 1 day after ischemic injury (ischemia). Representative image of four independent experiments are shown.

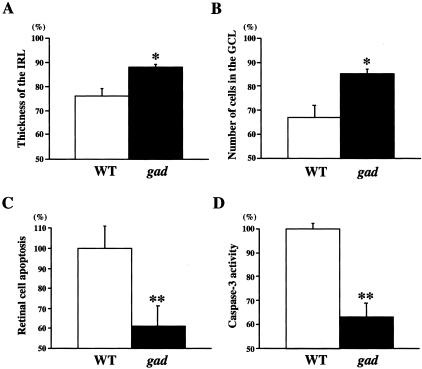

Effect of UCH-L1 on Ischemia-Induced Neural Cell Apoptosis

To determine whether increased expression of antiapoptotic and prosurvival proteins in gad mice really leads to resistance against ischemia, we next examined the histology of ischemic retinas in both strains. As expected, ischemic damage in gad mice was mild compared with wild-type mice (Figure 3); the thickness of the inner retinal layer (IRL) (Figure 4A) and the percentage of surviving cells in the GCL (Figure 4B) after ischemia were significantly larger in gad mice. We also analyzed apoptotic cells in the retina by TUNEL staining. Control animals showed practically no signals in both strains (data not shown). However, in ischemic retinas, TUNEL-positive cells were observed in all three nuclear layers in wild-type mice, but mainly only in the outer nuclear layer (ONL) in gad mice (Figure 3). Consistently, quantitative analysis by ELISA demonstrated decreased retinal cell apoptosis in gad mice (Figure 4C). Ischemia-induced retinal cell apoptosis is executed by two distinct caspase proteases. Caspase-1 is predominantly associated with photoreceptor cell apoptosis in the ONL, whereas caspase-3 is more active in the GCL and INL for the same process.29 To determine the mechanisms of strong tolerance against ischemia in gad mice, we next examined the activity of these two caspases in the ischemic retina. Caspase-1-like activity was not significantly different in gad mice compared with wild-type mice (80 ± 13%; P = not significant) (data not shown). On the other hand, caspase-3-like activity in gad mice was suppressed to 63 ± 6% compared with wild-type mice (P < 0.01) (Figure 4D).

Figure 3.

Representative pictures of HE staining (left) and TUNEL staining (right) in wild-type and gad mice retina before (control) and after ischemic injury (ischemia). Retinal damage 7 days after ischemia (HE staining) in gad mice was mild compared with wild-type mice. Consistently, TUNEL-positive cells 1 day after ischemia were observed only in the ONL in gad mice. Bar, 50 μm.

Figure 4.

Effect of ischemic injury in wild-type and gad mice retina. Thickness of the IRL (arrows in Figure 3) (A) and the number of cells in the GCL (arrowheads in Figure 3) (B) in retina 7 days after ischemic injury as a percentage of the non-ischemic fellow eye. Quantitative analysis of retinal cell apoptosis (C) and caspase-3-like activity (D) in retina 1 day after ischemic injury. Results of six independent experiments are presented as mean ± SD (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

Discussion

Ischemic injury is mainly associated with excessive concentrations of glutamate, which results in overactivation of glutamate receptors and initiates a cascade of events that leads to necrosis and/or apoptosis. Consistently, several studies have shown that retinal neurons can be protected by glutamate receptor antagonists.17,30,31 An alternative strategy to attenuate glutamate neurotoxicity is keeping the extracellular glutamate concentration below neurotoxic levels. We previously demonstrated that selective inhibition of N-acetylated-α-linked-acidic dipeptidase (NAALADase), an enzyme responsible for the hydrolysis of neuropeptide N-acetyl-aspartyl-glutamate to N-acetyl-aspartate and glutamate, robustly protects neurons in a rat model of stroke32 and in a mouse model of ischemic retinal injury.17 Another possible target is the glutamate transporter.33 There are four subtypes of glutamate transporters (GLAST, GLT-1, EAAC1, and EAAT5) in the retina.16,33 By using GLAST and GLT-1 knockout mice,34,35 we showed that both GLAST and GLT-1 (GLAST > GLT-1) are crucial for the protection of retinal cells from ischemic injury.16

In addition to these typical molecules involved in glutamate neurotoxicity, we first demonstrated that neuron-specific deubiquitinating enzyme, UCH-L1, is a new possible therapeutic target for ischemic retinal injury. In gad mice, functional loss of UCH-L1 results in the protection of retinal neurons following ischemic injury. One of the possible mechanisms is the accumulation of antiapoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and XIAP. Suppression of Bcl-2 leads to altered mitochondrial membrane permeability resulting in release of cytochrome c into the cytosol, which can trigger caspase activation leading to apoptosis.23–26 On the other hand, a member of the IAP (inhibitor of apoptosis proteins) family, XIAP, can bind to and inhibit caspase-3 activation.23–26 Consistently, retinal cell apoptosis in gad mice is suppressed mainly in the inner retina (Figure 3), where caspase-3 is more active than caspase-1.27 These results suggest a possibility that functional loss of UCH-L1 may lead to decreased cytochrome c release from mitochondria and subsequent caspase inactivation in gad mice. If UCH-L1 inhibition works on the apoptotic pathway both before and after cytochrome c release from mitochondria,23–26 this method may have a broader effect compared with the overexpression or suppression of a single antiapoptotic or apoptotic factor, respectively.

On the other hand, BDNF and PCREB protein expression levels were also up-regulated in gad mice. Recent studies have shown that trophic factors such as BDNF, ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), or glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) increase RGC survival and regeneration.36–45 Since CREB plays a central role in mediating responses of trophic factors including BDNF,27 enhanced release of these trophic factors in gad mice may prevent ischemia-induced retinal cell apoptosis. We previously showed that, in addition to direct neuroprotection, these factors can alter secondary trophic factor production in retina-specific Müller glial cells, which indirectly regulate neural cell survival.18,46 Consistently, intraocular injection of trophic factors induces the phosphorylated form of extracellular receptor kinase (pERK) or c-fos mainly in Müller cells.47,48 Thus, loss of UCH-L1 may induce neural cell survival by stimulating both neural and glial cells.18,46,49

Ischemic retinal injury is implicated in a number of pathological states, such as retinal artery occlusion, glaucoma, and diabetic retinopathy.16,17,30,31 Accordingly, the present results raise intriguing possibilities for the management of these pathological conditions by modifying the expression of UCH-L1 and activity of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway.50 Using this strategy with trophic factors,18,46 NAALADase inhibitor,17 glutamate transporter activators, such as bromocryptine,51,52 or overexpression of GLAST or GLT-1,16 may induce synergic effects on multiple cellular targets to prevent ischemia-induced neural cell apoptosis. However, due to the central function of the ubiquitin system in many basic cellular processes, modulation of this system can become a “double-edged sword”.1 Depletion of the free ubiquitin pool may cause accumulation of proteins that should be subjected to ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis. To address these critical issues, further investigations revealing the functional site of UCH-L1 and its involvement in ubiquitin induction in vivo will be needed.

Acknowledgments

We thank H.-M. A. Quah and L.F. Parada for critical reading of the manuscript, and members of the Wada lab for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Keiji Wada, M.D., Ph.D., Department of Degenerative Neurological Diseases, National Institute of Neuroscience, NCNP, 4-1-1 Ogawahigashi, Kodaira, Tokyo 187-8502, Japan. E-mail: wada@ncnp.go.jp.

Supported by grants from the Organization for Pharmaceutical Safety and Research, Japan Science and Technology Cooperation, the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan, and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

C. H. was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for Young Scientists.

References

- Hershko A, Ciechanover A, Varshavsky A. The ubiquitin system. Nat Med. 2000;6:1073–1081. doi: 10.1038/80384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiAntonio A, Haghighi AP, Portman SL, Lee JD, Amaranto AM, Goodman CS. Ubiquitination-dependent mechanisms regulate synaptic growth and function. Nature. 2001;412:449–452. doi: 10.1038/35086595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley D, Ozkaynak E, Varshavsky A. The yeast polyubiquitin gene is essential for resistance to high temperatures, starvation, and other stresses. Cell. 1987;48:1035–1046. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90711-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond U, Agell N, Haas AL, Redman K, Schlesinger MJ. Ubiquitin in stressed chicken embryo fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:2384–2388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimmeler S, Breitschopf K, Haendeler J, Zeiher AM. Dephosphorylation targets Bcl-2 for ubiquitin-dependent degradation: a link between the apoptosome and the proteasome pathway. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1815–1822. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.11.1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitschopf K, Haendeler J, Malchow P, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Posttranslational modification of Bcl-2 facilitates its proteasome-dependent degradation: molecular characterization of the involved signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1886–1896. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1886-1896.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daino H, Matsumura I, Takada K, Odajima J, Tanaka H, Ueda S, Shibayama H, Ikeda H, Hibi M, Machii T, Hirano T, Kanakura Y. Induction of apoptosis by extracellular ubiquitin in human hematopoietic cells: possible involvement of STAT3 degradation by proteasome pathway in interleukin 6-dependent hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2000;95:2577–2585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Fang S, Jensen JP, Weissman AM, Ashwell JD. Ubiquitin protein ligase activity of IAPs and their degradation in proteasomes in response to apoptotic stimuli. Science. 2000;288:874–877. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5467.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson KD, Lee KM, Deshpande S, Duerksen-Hughes P, Boss JM, Pohl J. The neuron-specific protein PGP 9.5 is a ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase. Science. 1989;246:670–673. doi: 10.1126/science.2530630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson KD, Deshpande S, Larsen CN. Comparisons of neuronal (PGP 9.5) and non-neuronal ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases. Biochem Soc Trans. 1992;20:631–637. doi: 10.1042/bst0200631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osaka H, Wang YL, Takada K, Takizawa S, Setsuie R, Li H, Sato Y, Nishikawa K, Sun YJ, Sakurai M, Harada T, Hara Y, Kimura I, Chiba S, Namikawa K, Kiyama H, Noda M, Aoki S, Wada K. Ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1 binds to and stabilizes monoubiquitin in neuron. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1945–1958. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe J, McDermott H, Landon M, Mayer RJ, Wilkinson KD. Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase (PGP 9.5) is selectively present in ubiquitinated inclusion bodies characteristic of human neurodegenerative diseases. J Pathol. 1990;161:153–160. doi: 10.1002/path.1711610210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy E, Boyer R, Auburger G, Leube B, Ulm G, Mezey E, Harta G, Brownstein MJ, Jonnalagada S, Chernova T, Dehejia A, Lavedan C, Gasser T, Steinbach PJ, Wilkinson KD, Polymeropoulos MH. The ubiquitin pathway in Parkinson’s disease. Nature. 1998;395:451–452. doi: 10.1038/26652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saigoh K, Wang YL, Suh JG, Yamanishi T, Sakai Y, Kiyosawa H, Harada T, Ichihara N, Wakana S, Kikuchi T, Wada K. Intragenic deletion in the gene encoding ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase in gad mice. Nat Genet. 1999;23:47–51. doi: 10.1038/12647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada T, Imaki J, Hagiwara M, Ohki K, Takamura M, Ohashi T, Matsuda H, Yoshida K. Phosphorylation of CREB in rat retinal cells after focal retinal injury. Exp Eye Res. 1995;61:769–772. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(05)80030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada T, Harada C, Watanabe M, Inoue Y, Sakagawa T, Nakayama N, Sasaki S, Okuyama S, Watase K, Wada K, Tanaka K. Functions of the two glutamate transporters GLAST and GLT-1 in the retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4663–4666. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada C, Harada T, Slusher BS, Yoshida K, Matsuda H, Wada K. N-acetylated-α-linked-acidic dipeptidase inhibitor has a neuroprotective effect on mouse retinal ganglion cells after pressure-induced ischemia. Neurosci Lett. 2000;292:134–136. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01444-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada T, Harada C, Nakayama N, Okuyama S, Yoshida K, Kohsaka S, Matsuda H, Wada K. Modification of glial-neuronal cell interactions prevents photoreceptor apoptosis during light-induced retinal degeneration. Neuron. 2000;26:533–541. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81185-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki K, Wakasugi N, Tomita T, Kikuchi T, Mukoyama M, Ando K. Gracile axonal dystrophy (GAD), a new neurological mutant in the mouse. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1988;187:209–215. doi: 10.3181/00379727-187-42656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naash MI, Al-Ubaidi MR, Anderson RE. Light exposure induces ubiquitin conjugation and degradation activities in the rat retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:2344–2354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfoco E, Krainc D, Ankarcrona M, Nicotera P, Lipton SA. Apoptosis and necrosis: two distinct events induced, respectively, by mild and intense insults with N-methyl-D-aspartate or nitric oxide/superoxide in cortical cell cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7162–7166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo ME, Haines D, Garay E, Chiavaroli C, Farine JC, Hannaert P, Berta A, Garay RP. Antioxidant properties of calcium dobesilate in ischemic/reperfused diabetic rat retina. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;428:277–286. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01196-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimoto Y, Shimizu S. Bcl-2 family: life-or-death switch. FEBS Lett. 2000;466:6–10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01761-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranger AM, Malynn BA, Korsmeyer SJ. Mouse models of cell death. Nat Genet. 2001;28:113–118. doi: 10.1038/88815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveraux QL, Reed JC. IAP family proteins: suppressors of apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:239–252. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DR. Apoptotic pathways: paper wraps stone blunts scissors. Cell. 2000;102:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkbeiner S. CREB couples neurotrophin signals to survival messages. Neuron. 2000;25:11–14. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80866-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CT, Furuta GT, Synnestvedt K, Colgan SP. Phosphorylation-dependent targeting of cAMP response element binding protein to the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway in hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12091–12096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220211797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katai N, Yoshimura N. Apoptotic retinal neuronal death by ischemia-reperfusion is executed by two distinct caspase family proteases. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:2697–2705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton SA. Retinal ganglion cells, glaucoma and neuroprotection. Prog Brain Res. 2001;131:712–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne NN, Melena J, Chidlow G, Wood JP. A hypothesis to explain ganglion cell death caused by vascular insults at the optic nerve head: possible implication for the treatment of glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:1252–1259. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.10.1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slusher BS, Vornov JJ, Thomas AG, Hurn PD, Harukuni I, Bhardwaj A, Traystman RJ, Robinson MB, Britton P, Lu XC, Tortella FC, Wozniak KM, Yudkoff M, Potter BM, Jackson PF. Selective inhibition of NAALADase, which converts NAAG to glutamate, reduces ischemic brain injury. Nat Med. 1999;5:1396–1402. doi: 10.1038/70971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K. Functions of glutamate transporters in the brain. Neurosci Res. 2000;37:15–19. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(00)00104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Watase K, Manabe T, Yamada K, Watanabe M, Takahashi K, Iwama H, Nishikawa T, Ichihara N, Kikuchi T, Okuyama S, Kawashima N, Hori S, Takimoto M, Wada K. Epilepsy and exacerbation of brain injury in mice lacking the glutamate transporter GLT-1. Science. 1997;276:1699–1702. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5319.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watase K, Hashimoto K, Kano M, Yamada K, Watanabe M, Inoue Y, Okuyama S, Sakagawa T, Ogawa S, Kawashima N, Hori S, Takimoto M, Wada K, Tanaka K. Motor discoordination and increased susceptibility to cerebellar injury in GLAST mutant mice. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:976–988. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mey J, Thanos S. Intravitreal injections of neurotrophic factors support the survival of axotomized retinal ganglion cells in adult rats in vivo. Brain Res. 1993;602:304–317. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90695-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A, Bray GM, Aguayo AJ. Neurotrophin-4/5 (NT-4/5) increases adult rat retinal ganglion cell survival and neurite outgrowth in vitro. J Neurobiol. 1994;25:953–959. doi: 10.1002/neu.480250805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour-Robaey S, Clarke DB, Wang YC, Bray GM, Aguayo AJ. Effects of ocular injury and administration of brain-derived neurotrophic factor on survival and regrowth of axotomized retinal ganglion cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1632–1636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unoki K, LaVail MM. Protection of the rat retina from ischemic injury by brain-derived neurotrophic factor, ciliary neurotrophic factor, and basic fibroblast growth factor. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:907–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammes HP, Federoff HJ, Brownlee M. Nerve growth factor prevents both neuroretinal programmed cell death and capillary pathology in experimental diabetes. Mol Med. 1995;1:527–534. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco A, Linden R. BDNF and NT-4 differentially modulate neurite outgrowth in developing retinal ganglion cells. J Neurosci Res. 1999;57:759–769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Q, Wang J, Matheson CR, Urich JL. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) promotes the survival of axotomized retinal ganglion cells in adult rats: comparison to and combination with brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). J Neurobiol. 1999;38:382–390. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19990215)38:3<382::aid-neu7>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Polo A, Aigner LJ, Dunn RJ, Bray GM, Aguayo AJ. Prolonged delivery of brain-derived neurotrophic factor by adenovirus-infected Müller cells temporarily rescues injured retinal ganglion cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3978–3983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeberle PD, Ball AK. Neurturin enhances the survival of axotomized retinal ganglion cells in vivo: combined effects with glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor and brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Neuroscience. 2002;110:555–567. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00557-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson WM, Wang Q, Tzekova R, Wiegand SJ. Ciliary neurotrophic factor and stress stimuli activate the Jak-STAT pathway in retinal neurons and glia. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4081–4090. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04081.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada T, Harada C, Kohsaka S, Wada E, Yoshida K, Ohno S, Mamada H, Tanaka K, Parada LF, Wada K. Microglia-Müller glia cell interactions control neurotrophic factor production during light-induced retinal degeneration. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9228–9236. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09228.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlin KJ, Campochiaro PA, Zack DJ, Adler R. Neurotrophic factors cause activation of intracellular signaling pathways in Müller cells and other cells of the inner retina, but not photoreceptors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:927–936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlin KJ, Adler R, Zack DJ, Campochiaro PA. Neurotrophic signaling in normal and degenerating rodent retinas. Exp Eye Res. 2001;73:693–701. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bringmann A, Reichenbach A. Role of Müller cells in retinal degenerations. Front Biosci. 2001;6:E72–E92. doi: 10.2741/bringman. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa K, Li H, Kawamura R, Osaka H, Wang YL, Hara Y, Hirokawa T, Manago Y, Amano T, Noda M, Aoki S, Wada K. Alterations of structure and hydrolase activity of parkinsonism-associated human ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L1 variants. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;304:176–183. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00555-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita H, Kawakami H, Zhang YX, Tanaka K, Nakamura S. Neuroprotective mechanism of bromocriptine. Lancet. 1995;346:1305. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91911-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita H, Kawakami H, Zhang YX, Tanaka K, Nakamura S. Effect of amino acid ergot alkaloids on glutamate transport via human glutamate transporter hGluT-1. J Neurol Sci. 1998;155:31–36. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(97)00266-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]