Abstract

Patients with defective osteoclastic acidification have increased numbers of osteoclasts, with decreased resorption, but bone formation that remains unchanged. We demonstrate that osteoclast survival is increased when acidification is impaired, and that impairment of acidification results in inhibition of bone resorption without inhibition of bone formation. We investigated the role of acidification in human osteoclastic resorption and life span in vitro using inhibitors of chloride channels (NS5818/NS3696), the proton pump (bafilomycin) and cathepsin K. We found that bafilomycin and NS5818 dose dependently inhibited acidification of the osteoclastic resorption compartment and bone resorption. Inhibition of bone resorption by inhibition of acidification, but not cathepsin K inhibition, augmented osteoclast survival, which resulted in a 150 to 300% increase in osteoclasts compared to controls. We investigated the effect of inhibition of osteoclastic acidification in vivo by using the rat ovariectomy model with twice daily oral dosing of NS3696 at 50 mg/kg for 6 weeks. We observed a 60% decrease in resorption (DPYR), increased tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase levels, and no effect on bone formation evaluated by osteocalcin. We speculate that attenuated acidification inhibits dissolution of the inorganic phase of bone and results in an increased number of nonresorbing osteoclasts that are responsible for the coupling to normal bone formation. Thus, we suggest that acidification is essential for normal bone remodeling and that attenuated acidification leads to uncoupling with decreased bone resorption and unaffected bone formation.

The coupling process is understood as a bone formation response that is the consequence of bone resorption, with an amount of bone formed that is equal to that resorbed.1,2 Uncoupling occurs when the balance between formation and resorption is disturbed, which might lead to either osteopetrosis or osteoporosis.3,4 Although it has long been appreciated that bone formation is tightly coupled to bone resorption in normal adult bone turnover,5,6 this coupling can be dissociated in some circumstances, for example during skeletal growth and in some but not all osteopetrotic mutations.

Bone consists of two phases, the organic phase, which contains proteins such as collagen type I, and the inorganic phase, which consists of crystallized calcium phosphate. Dissolution of the inorganic phase of bone under the osteoclast attached to the bone surface is a prerequisite for degradation of the organic phase, and is mediated by acidification of the resorption compartment. The decrease in pH necessary to dissolve the inorganic phase is mediated by an active transport of protons over the ruffled border membrane, which is driven by an osteoclastic V-type H+ ATPase.7,8 At the same time a passive transport of chloride through chloride channels preserves the electroneutrality,9 and is mediated by the chloride channel ClC-7.10,11 Degradation of the organic phase of bone is for the major part mediated by the enzyme cathepsin K, which degrades collagen type I.12–16 Interestingly, abrogation of degradation of the organic phase of bone does not prevent dissolution of the inorganic phase, because the lowering of pH in the osteoclastic resorption compartment remains unimpaired.14,17

In patients with impaired acidification of the resorption lacunae either because of a mutation in the osteoclastic V-ATPase a3 or in the chloride channel ClC-7, bone resorption is impaired whereas bone formation appears unaltered or even increased.18–22 A further interesting feature found in patients with defective acidification is the presence of increased numbers of abnormally large osteoclasts.22–24 The reason for this phenomenon has never been identified.

In contrast, pycnodysostotic patients harboring inactivating mutations in cathepsin K also have reduced resorption, but they have normal numbers of osteoclasts.22 Bone formation remains to be carefully investigated in cathepsin K-deficient patients, however small molecule inhibitors of cathepsin K have been shown to cause both an inhibition of bone resorption and bone formation in various animal models.15,25 The decrease in bone formation secondary to the decrease in bone resorption is possibly a result of the tight coupling of bone formation to bone resorption observed normally. From these combined observations, it could be speculated that acidification of the osteoclastic resorption compartment and dissolution of the inorganic phase of bone might be important for the proper coupling of bone resorption to bone formation. We explored that possibility in the present study, showing that acidification of the osteoclast resorption compartment may influence osteoclast survival and hence the coupling of bone formation to resorption.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Ethics

Patients were ascertained from a Danish family with autosomal dominant osteopetrosis (ADO)II previously shown to be a result of a G215R mutation in the ClC7 chloride channel gene.10,26 Nine mutation-positive members (four women and five men) aged 28 to 60 years of age were included as well as nine age- and sex-matched controls. The study was approved by the Danish Regional Ethical Committee (registration number 2473-03).

Osteoclast Culture and in Vitro Resorption Assays

Human osteoclasts were prepared as previously described.27 Mature osteoclasts were achieved by culturing 20 × 106 CD14 magnetic cell-sorted monocytes for 10 days in 75-cm2 flasks in the presence of 25 ng/ml of monocyte colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB-ligand (RANK-L, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) until osteoclasts were present. Following this, the mature osteoclasts were detached by trypsin treatment and used for experiments. All resorption experiments were performed by seeding 40,000 mature osteoclasts on cortical bovine bone slices (Nordic Bioscience Diagnostics, Herlev, Denmark) unless otherwise stated. Measurement of resorption was either performed by harvesting the supernatant and measurement of release of CTX (C-terminal telopeptide fragment of type I collagen) by the CrossLaps for culture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assay (Nordic Bioscience Diagnostics).

Osteoclast Acidification Assay

Acridine orange [3,6-bis(dimethylamine)acridine] at 13 μg/ml was loaded for 45 minutes in the culture medium supplemented with 20 mmol/L NaCl. The dye was removed by washing in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then the cells were placed in media containing cytokines and inhibitors, and the pictures were taken using an Olympus IX-70 microscope and an Olympus U-MWB filter (×20 objective) (Olympus, Ballerup, Denmark).

Alamar Blue Assay

Alamar Blue measurements were performed according to the manufacturer’s (Trek Diagnostics Systems Inc., Cleveland, OH) protocol. Briefly, Alamar Blue was diluted 1 to 10 in the cell culture media, and the color change was monitored carefully. When a clear switch from blue to purple was observed the color changes were measured using 540 nm as excitation wavelength and 590 nm as emission wavelength. Medium without cells was used as background. All results are shown as relative to the control on the individual day.

Tartrate-Resistant Acid Phosphatase (TRAP) Assay

The TRAP activity assay was performed as follows; 20 μl of plasma from the ovariectomy (OVX) experiments were added to a 96-well plate and 80 μl of freshly prepared reaction buffer (0.33 mol/L acetic acid, 0.167% Triton X-100, 0.33 mol/L NaCl, 3.33 mol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid at pH 5.5, 1.5 mg/ml of ascorbic acid, 7.66 mg/ml of Na2 tartrate, 3 mg/ml of 4-nitrophenylphosphate) was added. The reaction was left 1 hour at 37°C in the dark, and then stopped with 100 μl of 0.3 mol/L NaOH. The colorimetric changes were measured at 405 nm with 650 nm as the reference using an ELISA reader.

Drugs and Chemicals

The chloride channel inhibitors NS5818 [N-(3,5-dichloro-phenyl)-N′-{2-(1H-tetrazol-5-yl)-biphenyl-4-yl-4′-carboxylic acid dimethylamide} urea] (patent reference WO 0024707) and NS3696 [N-(3-bromo-phenyl)-N′-{4-bromo-2-(1-H-tetrazol-5-yl)-phenyl} urea] are close analogs of NS3736 [N-(3-bromo-phenyl)-N′-{4-bromo-2-(1-H-tetrazol-5-yl)-phenyl} urea]28 which were synthesized at Neurosearch A/S (Ballerup, Denmark). The remaining chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich (Copenhagen, Denmark) and the culture media were from Life Technologies unless otherwise is specified. The cathepsin K inhibitor was from Calbiochem (no. 219377). Findings were verified by the cathepsin K inhibitor E-64 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA).

Immunocytochemistry

Mature osteoclasts from ADOII patients and age- and sex-matched controls were seeded on glass coverslips, and cultured for 2 days in the presence of RANK-L and M-CSF. The cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde, and washed thoroughly in PBS. This was followed by blocking for nonspecific binding and permeabilization by incubating the cells in Tris-buffered saline containing 2.5% casein and 0.1% Triton X-100 for 30 minutes at room temperature. Then the cells were incubated with tetramethyl-rhodamine isothiocyanate-labeled phalloidin (Sigma Chemicals) overnight at 4°C, and washed in PBS. Then the nuclei were stained by incubation in 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole for 3 minutes, and finally the coverslips were mounted and the results were visualized using an Olympus BX-60 microscope equipped with a ×20 objective and filters suitable for tetramethyl-rhodamine isothiocyanate and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. The pictures were taken using an Olympus C-5050 zoom camera, and mounted in Corel Draw.

Ovariectomized Rat Model

For the reported OVX study, 6-month-old virgin female Sprague-Dawley rats (Taconics M&B A/S, Denmark) weighing 294 ± 23 g, were maintained at 21 ± 1°C, 55% humidity, 12-hour light-dark cycle, fed a standard diet (Altomin 1324, Chr. Pedersen A/S, Denmark) and tap water ad libitum. After an acclimatization period of 2 weeks the animals were randomized according to weight into groups of 10 each and, under midazolam/fentanyl/fluanison anesthesia either bilaterally ovariectomized (OVX) or sham operated. One group of rats was sacrificed to obtain a baseline control before treatment. The second day after surgery, groups of ovariectomized rats received either vehicle (NS3696, 50 mg/kg twice daily by gavage) or 17-β-estradiol (0.5 mg) as subcutaneously implanted slow-release pellets (60-day release; Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL). Twenty-four hour urine samples were collected 2 and 5 weeks after surgery. Serum samples were collected 2 and 6 weeks after surgery. Body weights of the animals were recorded throughout the experiment. The animals were killed after 6 weeks of treatment. The study was approved by the Experimental Animal Committee, the Danish Ministry of Justice, Copenhagen, Denmark (approval no. 1998/561-143).

Measurement of Bone Mineral Density

Ex vivo peripheral quantitative computed tomography was performed on the excised left proximal tibiae using a Stratec XCT-RM and associated software (Stratec Medizintechnik GmbH) performed by Skeletech, Bothell, WA. The metaphyseal region of the left proximal tibia from each animal was positioned for scanning at a site rich in cancellous bone that was 12% of the total bone length from the proximal articular surface. The position was verified using scout views and two 0.5-mm slices perpendicular to the long axis of the tibia shaft were collected. All scans were analyzed using a threshold for delineation of external boundary, and an area peel for subdivision into a cortical/subcortical region and a cancellous subregion. The bone mineral density (mg/cm3) and area properties of each subregion were then determined by system software analysis modes.

Biochemical Markers of Bone Turnover

Urine deoxypyridinoline was measured as a marker of bone resorption using the D-pyr Elisa assay (Metra Biosystems Inc.) and corrected for creatinine. Serum osteocalcin was measured as a marker of bone formation using the rat-MID osteocalcin ELISA assay (Nordic Bioscience Diagnostics).

Statistics

All graphs show one representative experiment of at least three, each with four individual replications. All statistical calculations have been performed by the Student’s two-tailed unpaired t-test assuming normal distribution with equal variance. For the OVX study, statistical testing was done by analysis of variance followed by posthoc test (Dunnett’s) against vehicle control. Statistical significance is given by number of asterisks (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; NS, not significant).

Results

ADOII Osteoclasts Appear Normal in Vitro, However, Acidification and Resorption Are Strongly Impaired

Osteoclast levels assessed by serum TRAP measurements29 and histological evaluation23 in ADOII patients are increased more than threefold. We have shown previously that although ADOII patients have increased osteoclast numbers24 the formation of osteoclasts from their CD14-positive monocytes does not differ from those isolated from healthy sex- and age-matched controls.10

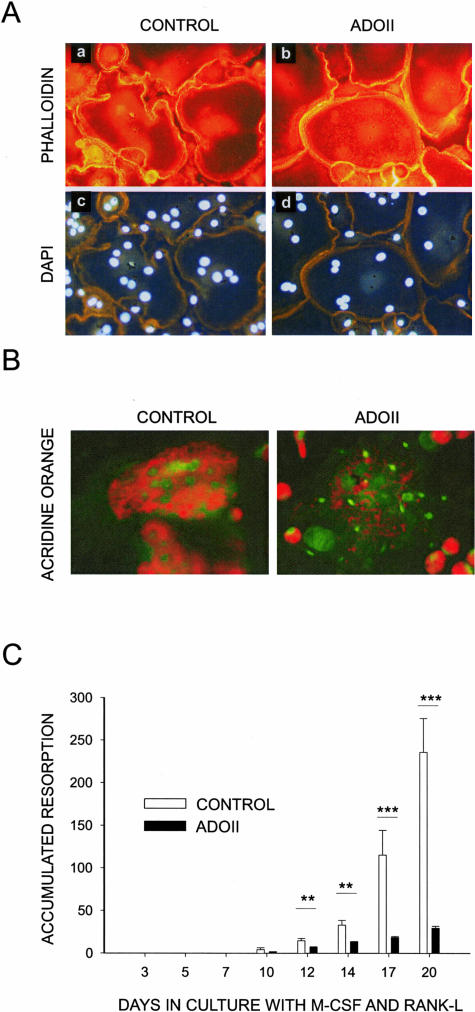

To investigate the morphology of ADOII osteoclasts we cultured age- and sex-matched ADOII osteoclasts and controls, and investigated the formation of actin rings by phalloidin staining. Osteoclasts from ADOII patients formed actin rings to the same level as did the control osteoclasts (Figure 1A). Furthermore, we seeded osteoclasts from normal control and ADOII patients onto cortical bone slices to examine their ability to secrete acid, as well as to degrade bone. Acidification in osteoclasts and the osteoclastic resorption compartment was investigated by acridine orange staining, which has previously been shown to localize and fluoresce orange in acidic vesicles, such as lysosomes but also in the resorption lacunae that are generally considered as extracellular lysosomes.7,11,30 We found that the ADOII osteoclasts have attenuated acidification, identified by a less intense staining on bone in ADOII osteoclasts than in control osteoclasts, where a bright fluorescent orange disk was seen (Figure 1B) likely corresponding to the resorption lacuna as previously described.7,11,30 Interestingly, the acridine orange localized in small vesicles in the ADOII osteoclasts, however no visible resorption lacuna was present. In contrast, in osteoclasts from normal patients the acridine orange staining was very intense, showing the resorption lacunae below the cells. Resorption of bone by ADOII osteoclasts was reduced by 80 to 90% compared to that by osteoclasts from age- and sex-matched controls (Figure 1C). Thus, it is concluded that ADOII osteoclasts have less capacity to acidify the resorption lacunae10,11 and therefore resorption is strongly attenuated, however osteoclast morphology and differentiation seem normal supporting previous publications on ClC-7-deficient osteoclasts.10,11

Figure 1.

ADOII osteoclasts have reduced acidification and resorption, but are otherwise normal. Healthy volunteer and ADOII monocytes were isolated as previously described.27 The monocytes were cultured in the presence of RANK-L and M-CSF until mature osteoclasts were obtained. These were lifted and reseeded either on glass coverslips (A) or cortical bovine bone slices (B), and cultured for 2 days. The cells on glass were fixed and immunostained by phalloidin to visualize the actin cytoskeleton (A, a and b) and by 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole to visualize the nuclei (A, c and d). B: Mature osteoclasts on bone slices were incubated with the dye acridine orange for 45 minutes, and the accumulation of dye was visualized using a fluorescence microscope. C: Monocytes seeded at a density of 350,000 cells/cm2 in 96-well plates on bovine cortical bone slices. The cells were cultured for the indicated time period in the presence of RANK-L and M-CSF at 25 ng/ml for the entire culture period, with refreshment of medium, growth factors, and inhibitors every other day. Bone resorption was measured in the supernatant by the Crosslaps ELISA assay and is presented as accumulated CTX release in nmol/L of CTX fragments.

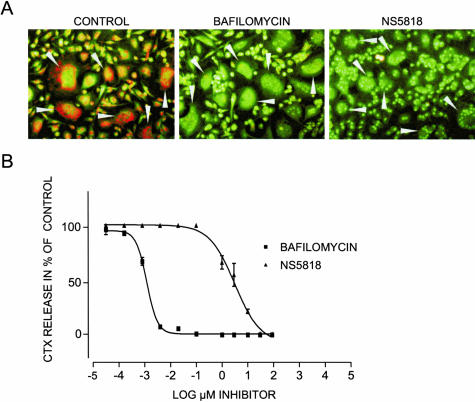

Chloride Channel and Proton Pump Inhibitors Mimic the ADOII Phenotype in Vitro

To obtain a model system for inhibition of acidification, either by inhibition of chloride channels or inhibition of the proton pump, we used the chloride channel inhibitor NS5818,10 a modified form of NS3736,28 and the proton pump inhibitor bafilomycin A1 and characterized their effects on acidification and resorption. As expected,10,28,31,32 bafilomycin inhibited acidification and resorption as measured by acridine orange and CTX release, respectively (Figure 2). Furthermore NS5818 inhibited both acidification and resorption, although with a lower potency (Figure 2). NS5818 inhibited bone resorption with an IC50 value of 5 μmol/L and bafilomycin with an IC50 value of 5 nmol/L, confirming that these inhibitors can be used to study the effect of acidification on bone turnover. The chloride channel inhibitor NS3696 that was later used in the rat OVX model displayed similar characteristics to NS5818, however with an IC50 value of 25 μmol/L for bone resorption (data not shown).

Figure 2.

NS5818 and bafilomycin inhibit acidification and resorption. Osteoclasts were cultured until maturity as described in Materials and Methods. A: The effect of NS5818 (50 μmol/L) and bafilomycin (100 nmol/L) on osteoclastic acidification was examined by acridine orange as described in Figure 1 previously. B: Mature human osteoclasts seeded at a density of 50,000 cells/well in 96-well plates on bovine cortical bone slices and cultured for 6 days with refreshment of medium with growth factors and compound at the indicated concentrations once. At the end of the culture period, the supernatant was harvested and resorption was investigated using the CrossLaps for culture ELISA assay.

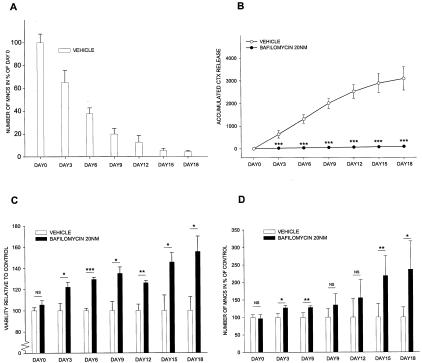

Inhibition of Acidification by Bafilomycin Augments Survival of Osteoclasts

To determine whether attenuated acidification affected osteoclast survival we used the proton pump inhibitor bafilomycin A1. First we investigated the number of multinuclear osteoclasts as a function of time. We cultured mature human osteoclasts for 18 days on cortical bovine bone slices, and investigated the number of multinucleated osteoclasts at various time points as indicated in Figure 3A and as described in Materials and Methods. At each time point osteoclasts were fixed and then TRAP stained followed by counting of multinuclear cells (MNCS) as presented in Figure 3A. As expected, the number of multinuclear osteoclasts decreased as a function of time.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of acidification leads to increased survival of the osteoclasts. A: Mature osteoclasts were lifted and reseeded on cortical bone slices and cultured for the indicated days. At the end of the indicated culture periods, osteoclasts were fixed and stained for TRAP and followed by counting of multinuclear cells (MNCS) by stereology. Values are expressed in percentage of osteoclast number at day 0. B–D: Mature osteoclasts were lifted and reseeded on cortical bone slices, and cultured in the presence or absence of 20 nmol/L bafilomycin A1 for the indicated days. At each time point the Alamar Blue and CTX levels in the conditioned media were measured, and afterward the osteoclasts were fixed and counted by stereology. B: The CTX release in the supernatant was measured and is presented as accumulated CTX release. C: The viability was measured and is presented relative to controls on each separate day. D: Multinuclear osteoclasts (MNCS) were counted and are presented as relative to control on each separate day.

To investigate whether this decrease in osteoclast number could be attenuated by inhibition of osteoclastic acidification of the resorption lacunae, we used the proton pump blocker bafilomycin. Mature human osteoclasts were seeded on cortical bovine bone slices in the presence and absence of bafilomycin at 20 nmol/L for 18 days. At each time point osteoclasts were fixed, and the number of osteoclasts was scored along with the measurement of Alamar Blue activity and CTX levels in the culture supernatant. Osteoclastic resorption was evaluated by assay of CTX in culture media,27,33 osteoclast number by the metabolic dye Alamar Blue, which previously has been used as an indicator for osteoclast number27 and has been shown to correlate with cell number,6,34 which in the present experiments were verified by counting of multinuclear cells. Treatment with bafilomycin completely inhibited osteoclastic bone resorption (Figure 3B) as expected.31,32 In contrast, cell number was significantly increased compared to vehicle control when evaluated by Alamar Blue data (Figure 3C), and counting multinuclear osteoclasts (Figure 3D). The increase in osteoclast number in the bafilomycin-treated conditions continued to increase with time compared to vehicle control.

As presented in Figure 3A, osteoclast number decreased as expected as a function of time, because osteoclasts are terminally differentiated cells with a limited life span. Thus, only compared to vehicle control at the individual days did osteoclast numbers increase as presented in Figure 3, C to D. Compared to the start of the culture period, osteoclast numbers decreased less in the bafilomycin-treated conditions which is manifested in an increased number of osteoclasts compared to control at the individual time points. This is in direct alignment with the phenotype of patients who suffer from a mutation in either ClC-7 or the V-ATPase that impairs osteoclastic acidification of the resorption lacunae, and therefore displays increased numbers of osteoclasts. When bafilomycin concentrations higher than 50 nmol/L were used for longer time periods toxic effects became apparent in which osteoclasts started dying, probably by apoptosis, as expected (data not shown).35 Whether this is caused by a toxic effect of bafilomycin, or it is because of the total absence of acidification in the osteoclasts remains to be studied.

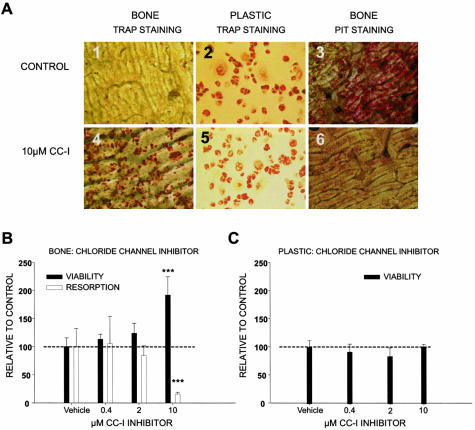

Inhibition of Chloride Channels in Vitro Mimics the ADOII Phenotype and Consequently Results in a Similar Phenotype as Inhibition of Acidification by Bafilomycin

To further investigate the role of acidification of the osteoclastic resorption compartment, and thereby the dissolution of the inorganic phase of bone with respect to inhibition of chloride channels, the chloride channel inhibitor NS5818 was used. According to the hypothesis this should lead to the same osteoclast phenotype as osteoclasts treated with bafilomycin. We cultured normal osteoclasts in the presence or absence of NS5818 on cortical bone slices and used osteoclasts cultured on plastic as a control.

Mature osteoclasts were cultured for 20 days on bovine bone slices in the presence or absence of 10 μmol/L of the chloride channel inhibitor NS5818. At the end of the culture period, we investigated resorption and TRAP activity. As seen in Figure 4A3, osteoclasts in the control condition had resorbed large areas on the bone slice. TRAP-positive cells were only detectable on plastic not on bone (Figure 4, A1 and A2), thus suggesting that after extensive bone resorption most osteoclasts had died. In contrast, when acidification, and thereby resorption, was attenuated by a chloride channel inhibitor (CC-I), NS5818 at 10 μmol/L, resorption was completely abrogated and TRAP-positive cells were evident on both plastic and bone. This suggests that factors released during resorption control the osteoclast life span.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of acidification by a chloride channel inhibitor also augments osteoclast survival. A: Mature osteoclasts were lifted and reseeded on cortical bone slices, and cultured in 96-well plates on bovine cortical bone slices or plastic. The cells were cultured for 20 days in the presence of RANK-L and M-CSF at 25 ng/ml for the entire culture period, with refreshment of medium, growth factors, and inhibitors every other day. At the end of the culture period TRAP staining was performed on bone and plastic (A; 1, 2, 4, and 5), and bone resorption was investigated by staining of resorption pits by hematoxylin (A, 3 and 6). B and C: To quantify the above qualitative indication, mature osteoclasts were cultured on either bone slices (B) or plastic (C) for 14 days in the presence of RANK-L and M-CSF at 25 ng/ml for the entire culture period, with refreshment of medium, growth factors, and the chloride channel inhibitor (CC-I), NS5818 at the indicated concentrations every other day. At the end of the culture period, cell number was quantified using Alamar Blue and expressed in percentage of control and bone resorption was measured in the supernatant by the Crosslaps ELISA assay.

To further investigate and quantify the effect of inhibition of acidification on resorption and cell viability, we cultured osteoclasts with various concentrations of the chloride channel inhibitor NS5818 and quantified resorption by the Crosslaps CTX assay and cell number by the Alamar Blue that we, in a previous section, correlated to the number of multinuclear osteoclasts. A dose-dependent increase in cell viability correlated with the dose-dependent decrease in resorption (Figure 4B). As previously discussed this is not a general increase in cell number, but an increased survival when comparing the osteoclast number between the inhibitor-treated and the vehicle condition at the endpoint. To test whether the chloride channel inhibitor was generally anti-apoptotic to osteoclasts the same experiment was performed on plastic, in which case there was no increase in cell viability (Figure 4C).

Inhibition of Chloride Channel Activity in Osteoclasts but Not in Macrophages Augments Cell Survival

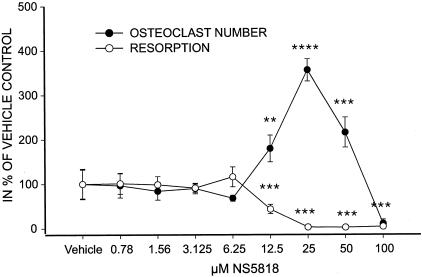

To further investigate the effect of chloride channel inhibition on cells of the hematopoietic lineage, we cultured either macrophages (CD14 cells treated only with M-CSF)36,37 or osteoclasts (CD14 cells treated with both RANK-L and M-CSF) in the presence of the chloride channel inhibitor NS5818 and investigated resorption and osteoclast/macrophage number. As presented in Figure 5, we observed a dose-dependent decrease in resorption of osteoclasts measured by the Crosslaps CTX assay. We observed a dose-dependent increase in osteoclast number investigated by counting of multinuclear cells on bone slices, and verified by Alamar Blue (data not shown). The dose-dependent decrease in resorption inversely correlated with the dose-dependent increase in osteoclast number. As previously discussed this is not a general increase in cell number, but an increased survival when comparing the osteoclast number between the inhibitor-treated and the vehicle condition at the endpoint. In contrast, macrophages cultured with the chloride channel inhibitor did not resorb bone and did not display increased cell numbers in response to chloride channel inhibition (data not shown). In summary, these data suggest that the osteoclastic cell death observed of osteoclast secondary to the resorption period is attenuated when an inhibitor of acidification inhibits bone resorption. This results in increased levels of nonresorbing osteoclasts.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of chloride channel activity only augments survival in osteoclasts not in macrophages. Mature osteoclasts were lifted and reseeded on cortical bone slices, and cultured in 96-well plates on bovine cortical bone slices with refreshment of medium, growth factors, and the indicated concentration of the chloride channel inhibitor NS5818 every other day. At the end of the culture period, day 14, cell number was quantified by staining with Erlich’s hematoxylin followed by counting of multinuclear cells (MNCS). Resorption was measured in the supernatant by the Crosslaps ELISA. Values are expressed in percentage of vehicle control at the endpoint.

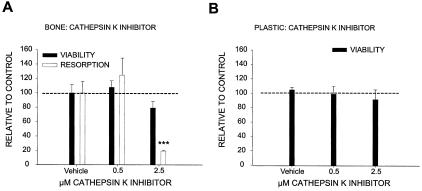

Dissolution of the Inorganic Phase but Not Resorption of the Organic Phase of Bone Affects Osteoclast Life Span

To further understand the importance of resorption for osteoclast life span, we investigated if an inhibitor of resorption of the organic phase of bone would promote the same increase in osteoclast viability. Thus, normal osteoclasts were cultured on bovine bone slices in the presence of a cathepsin K inhibitor (no. 219377, Calbiochem) at various concentrations, and we did not detect an increase in cell number, although the resorption was completely abrogated (Figure 6A). Similar results were obtained with the cathepsin K inhibitor E-64 (data not shown). The inhibitor did not interfere with osteoclast survival on plastic (Figure 6B), suggesting this compound to be neither a general survival factor nor toxic. Taken together, these data indicate that osteoclasts during acidification release factors that control life span. Thus, the increased levels of osteoclasts in the ADOII patients are possibly explained by an attenuation of apoptotic signals originating from the dissolution of the inorganic phase of bone.

Figure 6.

Inhibition of degradation of the organic phase of bone does not affect osteoclast survival. Mature osteoclasts were lifted and reseeded on cortical bone slices, and cultured in 96-well plates on bovine cortical bone slices or plastic. The osteoclasts were cultured for 14 days in the presence of RANK-L and M-CSF at 25 ng/ml for the entire culture period, with refreshment of medium, growth factors, and inhibitors every other day. The cells were cultured on either bone slices (A) or plastic (B) in the presence of vehicle or a cathepsin K inhibitor (no. 219377, Calbiochem) at the indicated concentrations. At the end of the culture period, cell number was quantified with Alamar Blue and expressed in percentage of control and bone resorption was measured in the supernatant by the Crosslaps ELISA assay.

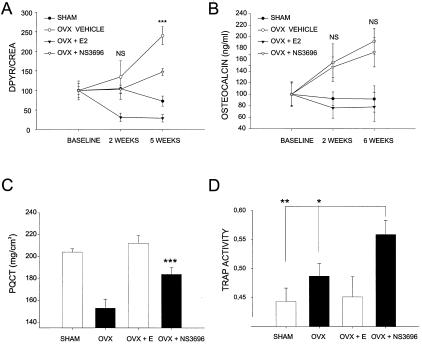

Inhibition of Chloride Channels in Vivo Mimics the Phenotype of the ADOII Patients

To investigate the effect on bone formation of inhibition of osteoclastic acidification in vivo, we used a chloride channel inhibitor in the aged rat ovariectomy model, with assessment of bone formation, bone resorption, and TRAP activity. We used a metabolically stable analog of NS5818, namely NS3696, that is a close analog of NS3736.28 Bone resorption was measured by DPYR and was significantly inhibited both by estrogen (P < 0.001) and NS3696 (P < 0.001) (Figure 7A). On the other hand, when bone formation was investigated by assay of serum osteocalcin, estrogen repressed the OVX-induced increase in bone formation to sham levels, in contrast to the chloride channel inhibitor, which had no effect on bone formation (Figure 7B). This is in direct alignment with previous results in which a chloride channel inhibitor did not affect bone formation both investigated by osteocalcin measurement and dynamic histomorphometry.28 Previous studies have clearly indicated osteocalcin to be a valid marker for bone formation and to correlate with dynamic histomorphometry parameters of bone formation.28,38–40

Figure 7.

Inhibition of acidification uncouples bone formation and resorption in vivo. Six-month-old rats were either sham-operated or ovariectomized (OVX). The OVX rats were treated orally with 50 mg/kg/day NS3696, 17-β-estradiol (E), or vehicle (V) twice daily for 6 weeks. Urine DPYR levels were determined as a biochemical parameter of bone resorption, and statistical significance is indicated between OVX vehicle and OVX + NS3696. A: Serum osteocalcin levels were determined as a biochemical parameter of bone formation, statistical significance is indicated between OVX vehicle and OVX + NS3696. B: Bone mineral density at the proximal tibia was determined by peripheral quantitated computed tomography as described in Materials and Methods (C) and TRAP activity was investigated by the TRAP assay in the serum (D).

Trabecular bone was assessed by peripheral quantitated computed tomography to test whether the inhibition of chloride channels could prevent the bone loss of estrogen deficiency. NS3696 inhibited the estrogen-deficient bone loss by ∼60% compared to the effect of estrogen and of sham-operated animals (Figure 7C). Lastly, TRAP activity was assayed in the plasma of the rats. Significantly increased TRAP levels were observed both in OVX- and NS3696-treated animals (Figure 7D). It has previously been shown that the increased number of osteoclasts is a consequence of estrogen depletion by the OVX surgery,41 which is reflected in the present TRAP levels. Moreover, the TRAP level was further augmented through attenuation of acidification, as in ADOII patients. Taken together, attenuated acidification results in increased osteoclast levels and decreased levels of bone resorption whereas bone formation is normal, and thus results in an uncoupling of bone resorption and formation.

Discussion

Using inhibitors of both ClC-7 and the V-ATPase we have provided evidence that inhibition of acidification prolongs osteoclast life span. Inhibiting osteoclastic resorption with a cathepsin K inhibitor on the other hand did not prolong osteoclast viability. We speculate that the prolonged osteoclast survival resulting from impaired acidification could be an important player in the coupling of bone formation to bone resorption, because patients with attenuated acidification appear to have impaired resorption with unaltered levels of bone formation.

We tested the hypothesis that lower levels of bone resorption might be compatible with unaltered levels of bone formation by using a chloride channel inhibitor in vivo in the rat OVX model. Consistent with the findings in patients with a attenuated acidification, in the case of inhibition of either ClC-718,20,24 or the V-ATPase,21 we found that inhibition of acidification led to a significant 60% reduction in DPYR as a marker of bone resorption with ClC-7 inhibition, in the face of no change in bone formation measured by osteocalcin. This indicates uncoupling of bone formation from resorption. In contrast, estrogen treatment resulted in a significant decrease in both bone resorption and bone formation, as is well established.38–40

To further investigate if more parameters in the OVX experiment mimicked the acidification-attenuated patients, we investigated TRAP activity in serum and found that TRAP activity was significantly increased in OVX rats treated with a chloride channel inhibitor, suggesting increased levels of osteoclasts. This accords with the increased levels of osteoclasts in acidification-attenuated patients.22

Decreased levels of bone resorption associated with unchanged levels of bone formation were observed in the human ATP6i-dependent autosomal recessive osteopetrosis,21 which is caused by a loss of function mutation in the osteoclastic V-ATPase. The ATP6i patients suffer from a similar but more severe form of osteopetrosis than the ADOII patients.21 Increased levels of nonresorbing osteoclasts because of impaired acidification with unaltered bone formation or even increased bone formation, are found in the ADOII and ATP6i patients,21,23,24 as well as in OVX rats treated with a chloride channel inhibitor. Each of these separate cases display increased osteoclast levels, resorption attenuated osteoclasts in the face of bone formation levels similar to or increased compared to control. In alignment, by investigation of biochemical markers in the osteopetrotic ADOII patients,18 a significant linear correlation between TRAP5b as a marker for osteoclast number and osteocalcin as a marker for bone formation was found. This is verified by the finding of a significant increase in bone formation investigated by mineralized surface index in ADOII patients.42 In conjunction, by inhibition of osteoclastic acidification in vivo by bafilomycin in new bone implants in a rat model, a massive increase in new bone formation was observed.43

The cathepsin K-deficient patients (pycnodysostosis) and the cathepsin K-null mutation mice that develop osteopetrosis because of a deficit in matrix degradation, but not demineralization14,16,44 do not display increased levels of osteoclasts. This further indicates that factors released during dissolution of the inorganic phase of the bone are playing a role in osteoclast life span. When cathepsin K inhibitors were used in two different models of osteoporosis significant decreases in bone resorption were observed, however accompanied by secondary significant decreases in bone formation.15,25

In our previous studies of the effect of a putative ClC-7 inhibitor in the aged rat OVX model,28 evaluating bone resorption by CTX and formation by osteocalcin, as well as using dynamic histomorphometry indices of mineral apposition rate and mineralized surface index, we showed that by inhibition of acidification of the osteoclastic resorption lacunae, bone resorption was dose dependently inhibited without an effect on bone formation. This suggested that the signal for bone formation could be maintained despite the reduced resorption. The current experiments are the first to provide a molecular rationale for the uncoupling, as described below.

Proper coupling is understood as a bone formation response that is the consequence of bone resorption, with an amount of bone formed that is equal to that resorbed. Uncoupling occurs when the balance between formation and resorption is disturbed. We propose that interfering with acidification shifts this balance, with greatly reduced resorption, yet formation is maintained. Thus acidification contributes in an important way to the normal coupling of bone formation to resorption. Thus, we suggest that bone formation can occur without the forgoing event of extensive bone resorption, in the event of impaired acidification at which time the two processes of bone resorption and bone formation have been uncoupled.

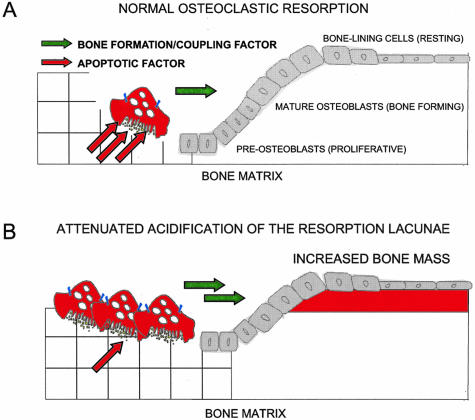

Our current hypothesis for the uncoupling of resorption and formation is illustrated in the schematic Figure 8. During the normal resorption event, osteoclasts for the duration of the resorption period release proapoptotic factors and thereby control both the depth of the resorption lacunae and life span of the osteoclasts (Figure 8A). However, in osteoclasts in which acidification of the resorption lacunae is attenuated, an increased level of osteoclasts is observed, possibly because of increased survival or attenuated apoptosis. This could be explained by a reduced release of factors during resorption (Figure 8B), thus explaining the increased numbers of nonresorbing osteoclasts present in ADOII and ATP6i patients.24,42 The increased numbers of osteoclasts could result in an increased supply of signal(s) created directly by the osteoclasts (Figure 8B) which continue signaling for bone formation.

Figure 8.

A model for the role of acidification in the coupling of bone formation to bone resorption. Schematic representation of the role of acidification in bone turnover. A: Normal bone turnover in which osteoclasts resorb bone and release normal amounts of proapoptotic factors indicated by red arrows. B: Acidification attenuated resorption in which osteoclasts have increased life span as a consequence of impaired dissolution of the inorganic phase of bone resulting in increased numbers of osteoclasts, possibly because of an attenuation of the release of proapoptotic factors. The increased number of osteoclasts results in an increased amount of signaling from osteoclasts possibly stimulating bone formation, indicated by the green arrows.

Because bone formation in the normal adult skeleton is initiated only where bone resorption previously had occurred,5 mature osteoclast function is important for continuous bone formation. The exact molecules responsible for the coupling of bone formation to bone resorption still remain to be investigated and identified, however the context of the current experiments suggests a novel path for investigation of the factors coupling bone formation to bone resorption. The so-called coupling factor may indeed not be only single molecule, but most likely a combination of events and factors that are necessary for bone formation to be initiated. These combined factors might include a resorption surface and a bone formation signal from osteoclasts either generated directly by osteoclast or indirectly from the bone matrix, which is influenced by the level of acidification in the resorption lacunae.

In conclusion, by attenuation of osteoclast apoptosis without increasing the amount of resorption, the so-called coupling signal to osteoblasts is continuously present even though resorption of the matrix is strongly attenuated. Thereby bone formation can proceed without a previous event of extensive osteoclastic resorption. Taken together, acidification inhibitors could be promising drugs for treatment and prevention of osteoporosis, in which a net increase in bone is expected, as an outcome of treatment, because only osteoclast activity and not osteoblast activity is impaired.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. M.A. Karsdal, Nordic Bioscience A/S, Herlev Hovedgade 207, DK-2730 Herlev, Denmark. E-mail: mk@nordicbioscience.com.

References

- Martin TJ. Hormones in the coupling of bone resorption and formation. Osteoporos Int. 1993;3(Suppl 1):121–125. doi: 10.1007/BF01621884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M, Udagawa N, Matsuura S, Mogi M, Nakamura H, Horiuchi H, Saito N, Hiraoka BY, Kobayashi Y, Takaoka K, Ozawa H, Miyazawa H, Takahashi N. Osteoprotegerin regulates bone formation through a coupling mechanism with bone resorption. Endocrinology. 2003;144:5441–5449. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelbaum SL, Ross FP. Genetic regulation of osteoclast development and function. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:638–649. doi: 10.1038/nrg1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goltzman D. Discoveries, drugs and skeletal disorders. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:784–796. doi: 10.1038/nrd916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R. Washington: American Society for Bone and Mineral Research,; Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism. 2003:pp 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Karsdal MA, Andersen TA, Bonewald L, Christiansen C. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) safeguard osteoblasts from apoptosis during trans-differentiation into osteocytes: MT1-MMP maintains osteocyte viability. DNA Cell Biol. 2004;23:155–165. doi: 10.1089/104454904322964751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R, Neff L, Louvard D, Courtoy PJ. Cell-mediated extracellular acidification and bone resorption: evidence for a low pH in resorbing lacunae and localization of a 100-kD lysosomal membrane protein at the osteoclast ruffled border. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:2210–2222. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.6.2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair HC, Teitelbaum SL, Ghiselli R, Gluck S. Osteoclastic bone resorption by a polarized vacuolar proton pump. Science. 1989;245:855–857. doi: 10.1126/science.2528207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al Awqati Q. Chloride channels of intracellular organelles. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:504–508. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen K, Gram J, Schaller S, Dahl BH, Dziegiel MH, Bollerslev J, Karsdal MA. Characterization of osteoclasts from patients harboring a G215R mutation in ClC-7 causing autosomal dominant osteopetrosis type II. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1537–1545. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63712-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornak U, Kasper D, Bosl MR, Kaiser E, Schweizer M, Schulz A, Friedrich W, Delling G, Jentsch TJ. Loss of the ClC-7 chloride channel leads to osteopetrosis in mice and man. Cell. 2001;104:205–215. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratzl-Zelman N, Valenta A, Roschger P, Nader A, Gelb BD, Fratzl P, Klaushofer K. Decreased bone turnover and deterioration of bone structure in two cases of pycnodysostosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1538–1547. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnero P, Ferreras M, Karsdal MA, NicAmhlaoibh R, Risteli J, Borel O, Qvist P, Delmas PD, Foged NT, Delaisse JM. The type I collagen fragments ICTP and CTX reveal distinct enzymatic pathways of bone collagen degradation. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:859–867. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.5.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowen M, Lazner F, Dodds R, Kapadia R, Feild J, Tavaria M, Bertoncello I, Drake F, Zavarselk S, Tellis I, Hertzog P, Debouck C, Kola I. Cathepsin K knockout mice develop osteopetrosis due to a deficit in matrix degradation but not demineralization. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:1654–1663. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.10.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lark MW, Stroup GB, James IE, Dodds RA, Hwang SM, Blake SM, Lechowska BA, Hoffman SJ, Smith BR, Kapadia R, Liang X, Erhard K, Ru Y, Dong X, Marquis RW, Veber D, Gowen M. A potent small molecule, nonpeptide inhibitor of cathepsin K (SB 331750) prevents bone matrix resorption in the ovariectomized rat. Bone. 2002;30:746–753. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00675-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saftig P, Hunziker E, Everts V, Jones S, Boyde A, Wehmeyer O, Suter A, von Figura K. Functions of cathepsin K in bone resorption. Lessons from cathepsin K deficient mice. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2000;477:293–303. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46826-3_32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everts V, Delaisse JM, Korper W, Niehof A, Vaes G, Beertsen W. Degradation of collagen in the bone-resorbing compartment underlying the osteoclast involves both cysteine-proteinases and matrix metalloproteinases. J Cell Physiol. 1992;150:221–231. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alatalo SL, Ivaska KK, Waguespack SG, Econs MJ, Vaananen HK, Halleen JM. Osteoclast-derived serum tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b in Albers-Schonberg disease (type II autosomal dominant osteopetrosis). Clin Chem. 2004;50:883–890. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.029355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollerslev J, Andersen PE., Jr Radiological, biochemical and hereditary evidence of two types of autosomal dominant osteopetrosis. Bone. 1988;9:7–13. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(88)90021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollerslev J. Autosomal dominant osteopetrosis: bone metabolism and epidemiological, clinical, and hormonal aspects. Endocr Rev. 1989;10:45–67. doi: 10.1210/edrv-10-1-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taranta A, Migliaccio S, Recchia I, Caniglia M, Luciani M, De Rossi G, Dionisi-Vici C, Pinto RM, Francalanci P, Boldrini R, Lanino E, Dini G, Morreale G, Ralston SH, Villa A, Vezzoni P, Del Principe D, Cassiani F, Palumbo G, Teti A. Genotype-phenotype relationship in human ATP6i-dependent autosomal recessive osteopetrosis. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:57–68. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63798-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vernejoul MC, Benichou O. Human osteopetrosis and other sclerosing disorders: recent genetic developments. Calcif Tissue Int. 2001;69:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s002230020046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollerslev J, Marks SC, Jr, Pockwinse S, Kassem M, Brixen K, Steiniche T, Mosekilde L. Ultrastructural investigations of bone resorptive cells in two types of autosomal dominant osteopetrosis. Bone. 1993;14:865–869. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(93)90316-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollerslev J, Steiniche T, Melsen F, Mosekilde L. Structural and histomorphometric studies of iliac crest trabecular and cortical bone in autosomal dominant osteopetrosis: a study of two radiological types. Bone. 1989;10:19–24. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(89)90142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup GB, Lark MW, Veber DF, Bhattacharyya A, Blake S, Dare LC, Erhard KF, Hoffman SJ, James IE, Marquis RW, Ru Y, Vasko-Moser JA, Smith BR, Tomaszek T, Gowen M. Potent and selective inhibition of human cathepsin K leads to inhibition of bone resorption in vivo in a nonhuman primate. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:1739–1746. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.10.1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleiren E, Benichou O, Van Hul E, Gram J, Bollerslev J, Singer FR, Beaverson K, Aledo A, Whyte MP, Yoneyama T, deVernejoul MC, Van Hul W. Albers-Schonberg disease (autosomal dominant osteopetrosis, type II) results from mutations in the ClCN7 chloride channel gene. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:2861–2867. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.25.2861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsdal MA, Hjorth P, Henriksen K, Kirkegaard T, Nielsen KL, Lou H, Delaisse JM, Foged NT. Transforming growth factor-beta controls human osteoclastogenesis through the p38 MAPK and regulation of RANK expression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44975–44987. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303905200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller S, Henriksen K, Sveigaard C, Heegaard AM, Helix N, Stahlhut M, Ovejero MC, Johansen JV, Solberg H, Andersen TL, Hougaard D, Berryman M, Shiodt CB, Sorensen BH, Lichtenberg J, Christophersen P, Foged NT, Delaisse JM, Engsig MT, Karsdal MA. The chloride channel inhibitor n53736 prevents bone resorption in ovariectomized rats without changing bone formation. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:1144–1153. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waguespack SG, Hui SL, White KE, Buckwalter KA, Econs MJ. Measurement of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase and the brain isoenzyme of creatine kinase accurately diagnoses type II autosomal dominant osteopetrosis but does not identify gene carriers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2212–2217. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.5.8497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palokangas H, Mulari M, Vaananen HK. Endocytic pathway from the basal plasma membrane to the ruffled border membrane in bone-resorbing osteoclasts. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:1767–1780. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.15.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundquist K, Lakkakorpi P, Wallmark B, Vaananen K. Inhibition of osteoclast proton transport by bafilomycin A1 abolishes bone resorption. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;168:309–313. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)91709-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundquist KT, Marks SC., Jr Bafilomycin A1 inhibits bone resorption and tooth eruption in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 1994;9:1575–1582. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650091010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foged NT, Delaisse JM, Hou P, Lou H, Sato T, Winding B, Bonde M. Quantification of the collagenolytic activity of isolated osteoclasts by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11:226–237. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650110212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsdal MA, Larsen L, Engsig MT, Lou H, Ferreras M, Lochter A, Delaisse JM, Foged NT. Matrix metalloproteinase-dependent activation of latent transforming growth factor-beta controls the conversion of osteoblasts into osteocytes by blocking osteoblast apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44061–44067. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okahashi N, Nakamura I, Jimi E, Koide M, Suda T, Nishihara T. Specific inhibitors of vacuolar H(+)-ATPase trigger apoptotic cell death of osteoclasts. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:1116–1123. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.7.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Katayama N, Ikuta Y, Mukai K, Fujieda A, Mitani H, Araki H, Miyashita H, Hoshino N, Nishikawa H, Nishii K, Minami N, Shiku H. Activities of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-3 on monocytes. Am J Hematol. 2004;75:179–189. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plesner A. Increasing the yield of human mononuclear cells and low serum conditions for in vitro generation of macrophages with M-CSF. J Immunol Methods. 2003;279:287–295. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(03)00234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balena R, Toolan BC, Shea M, Markatos A, Myers ER, Lee SC, Opas EE, Seedor JG, Klein H, Frankenfield D, Quartuccio H, Fioravanti C, Brown CE, Hayes WC, Rodan GA. The effects of 2-year treatment with the aminobisphosphonate alendronate on bone metabolism, bone histomorphometry, and bone strength in ovariectomized nonhuman primates. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:2577–2586. doi: 10.1172/JCI116872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghe J, Oloumi G, van Herck E, van Bree R, Dequeker J, Einhorn TA, Bouillon R. Effects of long-term diabetes and/or high-dose 17 beta-estradiol on bone formation, bone mineral density, and strength in ovariectomized rats. Bone. 1997;20:421–428. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(97)00029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavassieux P, Pastoureau P, Chapuy MC, Delmas PD, Meunier PJ. Glucocorticoid-induced inhibition of osteoblastic bone formation in ewes: a biochemical and histomorphometric study. Osteoporos Int. 1993;3:97–102. doi: 10.1007/BF01623380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane NE, Thompson JM, Haupt D, Kimmel DB, Modin G, Kinney JH. Acute changes in trabecular bone connectivity and osteoclast activity in the ovariectomized rat in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:229–236. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockstedt H, Bollerslev J, Melsen F, Mosekilde L. Cortical bone remodeling in autosomal dominant osteopetrosis: a study of two different phenotypes. Bone. 1996;18:67–72. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00424-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rzeszutek K, Sarraf F, Davies JE. Proton pump inhibitors control osteoclastic resorption of calcium phosphate implants and stimulate increased local reparative bone growth. J Craniofac Surg. 2003;14:301–307. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200305000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motyckova G, Fisher DE. Pycnodysostosis: role and regulation of cathepsin K in osteoclast function and human disease. Curr Mol Med. 2002;2:407–421. doi: 10.2174/1566524023362401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]