Abstract

P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) binding to P-selectin controls early leukocyte rolling during inflammation. Interestingly, antibodies and pharmacological inhibitors (eg, rPSGL-Ig) that target the N-terminus of PSGL-1 reduce but do not abolish P-selectin-dependent leukocyte rolling in vivo whereas PSGL-1-deficient mice have almost no P-selectin-dependent rolling. We have investigated mechanisms of P-selectin-dependent, PSGL-1-independent rolling using intravital microscopy. Initially we used fluorescent microspheres to study the potential of L-selectin and the minimal selectin ligand sialyl Lewisx (sLex) to interact with postcapillary venules in the absence of PSGL-1. Microspheres coated with combinations of L-selectin and sLex interacted with surgically stimulated cremaster venules in a P-selectin-dependent manner. Microspheres coated with either L-selectin or sLex alone showed less evidence of interaction. We also investigated leukocyte rolling in the presence of PSGL-1 antibody or inhibitor (rPSGL-Ig), both of which partially inhibited P-selectin-dependent leukocyte rolling. Residual rolling was substantially inhibited by L-selectin-blocking antibody or a previously described sLex mimetic (CGP69669A). Together these data suggest that leukocytes can continue to roll in the absence of optimal P-selectin/PSGL-1 interaction using an alternative mechanism that involves P-selectin-, L-selectin-, and sLex-bearing ligands.

Selectins and their ligands support early interactions between leukocytes and endothelium during inflammation1 and present attractive targets for anti-inflammatory drugs. P-Selectin may be a good target for cardiovascular disease therapy,2–5 although notable clinical trial disappointments6,7 suggest that effective P-selectin inhibition may be more challenging than expected.

Natural ligand mimicry is a common drug development approach. Elements of PSGL-1 required for high-affinity P-selectin recognition include a sialylated, fucosylated O-glycan and tyrosine sulfation at appropriate positions near the N-terminus.8 Drugs mimicking one or more of these elements could theoretically inhibit P-selectin. Inhibitors based on the carbohydrate selectin ligand, sLex, are effective, albeit in high doses, against E-selectin-dependent leukocyte rolling in vivo but have no measurable effect on established P-selectin-dependent rolling.9 Closer imitations of PSGL-1 are more effective. A recombinant fusion protein, rPSGL-Ig, of 47 amino acids from the NH2-terminal of human PSGL-1 linked to the Fc portion of human immunoglobulin-1 (IgG1)10 reduces established P-selectin-dependent leukocyte rolling in murine postcapillary venules by up to 60% whereas glycosulfopeptides, synthesized to mimic the high-affinity binding region of human PSGL-1,8,11 reduce rolling by up to 70%. Antibodies targeting human or murine PSGL-1 also inhibit, but do not abolish, P-selectin-dependent rolling in vivo.12–15 In contrast, PSGL-1-deficient mice develop negligible P-selectin-dependent leukocyte rolling in venules after surgical stimulation.16

The relevance of low-affinity ligand binding to P-selectin function in vivo is uncertain although P-selectin-dependent/PSGL-1-independent rolling has been demonstrated using an in vitro flow chamber wherein microspheres coated with a high density of sLex rolled on a P-selectin-coated surface.17 Although the interactions of leukocytes rolling in vivo are undoubtedly more complex than that those of beads rolling in vitro, we believe that interactions between P-selectin and low-affinity sLex-bearing ligands might permit some leukocyte rolling in situations in which optimal binding is absent. Such low-affinity interactions might explain the portion of leukocyte rolling that is resistant to P-selectin antagonists and PSGL-1-blocking antibodies and allow P-selectin-dependent rolling of cells that do not express fully functional PSGL-1.

Here, we investigate mechanisms of P-selectin-dependent rolling occurring in the absence of optimal P-selectin-PSGL-1 interaction. We find that coating fluorescent microspheres with a combination of L-selectin and sLex supports P-selectin-dependent interaction with postcapillary venules in vivo and that a sLex mimetic, CGP69669A, inhibits P-selectin-dependent leukocyte rolling that remains after treatment with either rPSGL-Ig- or PSGL-1-blocking antibody.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Anti-P-selectin (RB40.34, rat IgG1λ), anti-L-selectin (Mel-14, rat IgG1κ), anti-mouse PSGL-1 (2PH1, rat IgG1κ), RB6–8C5 (IgG2bκ), and isotype control antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences (Oxford, UK). Anti-E-selectin antibody (10E6, rat IgG2b) was a kind gift from Dr. B. Wolitzky (Hoffman-LaRoche, Nutley, NJ). Nonfluorescent, yellow-green, and red fluorescent 1-μm Neutravidin-coated microspheres, BlockAid, and biotin-labeling kits were obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Human IgG was obtained from Sigma (Dorset, UK). Biotinylated sLex was purchased from Syntesome (Munich, Germany). Murine L-selectin/Fc chimera were purchased from R&D Systems (Oxford, UK). rPSGL-Ig was a kind gift from Dr. R. Schaub (Wyeth, Inc., Andover, MA). CGP69669A was a kind gift from Dr. G. Thoma (Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland). All inhibitors were applied at doses previously determined to provide maximum blockade of their respective ligands.9,14,18,19

Microspheres

IgG and L-selectin were biotinylated using a kit according to the manufacturer’s (Molecular Probes) instructions. Conditions for coating microspheres with biotinylated reagents were determined by attaching different fluorescent biotinylated ligands to nonfluorescent microspheres followed by flow cytometry. For in vivo studies, yellow-green or red fluorescent microspheres (0.07 ml, 1 μm in diameter) were coated with biotinylated human IgG, sLex, L-selectin, or a combination of both L-selectin and sLex. L-selectin coating was performed at a concentration (10 μg/ml) ∼1/10th that determined previously to support L-selectin-dependent rolling20 and biotinylated sLex coating was performed at 200 μg/ml to saturate the remaining 90% of the microsphere surface. Saturating concentrations (200 μg/ml) of IgG were used for control microspheres. After coating with ligands of interest, microspheres were incubated with a commercial solution (BlockAid) according to the manufacturer’s instructions to ensure covering of all reactive sites on the bead surface and reduce nonspecific bead interactions in vivo.

Animals

Male C57BL/6 (Harlan, Oxford, UK) and L-selectin knockout mice (25 to 30 g) were used.21 All procedures were approved by the University of Sheffield ethics committee and performed in accordance with the UK Home Office Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986.

Intravital Microscopy

Observations of leukocyte and microsphere interactions in venules of the mouse cremaster were performed as described.22 Mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection (12.5 μl/g) of a mixture consisting of 10 mg/ml of ketamine hydrochloride (Ketaset; Willows Francis Veterinary, Crawley, UK), 1 mg/ml of xylazine hydrochloride (Bayer, Suffolk, UK), and 0.02 mg/ml of atropine sulfate (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Gloucester, UK). Cannulations of the trachea, jugular vein, and carotid artery were performed, and the cremaster muscle exposed and spread over a specialized viewing platform. Temperature was controlled using a thermistor-regulated heating pad (PDTronics, Sheffield, UK) and the cremaster was superfused with thermocontrolled (36°C) bicarbonate-buffered saline. Venules were observed 10 to 30 minutes after surgical stimulation of cremaster, when leukocyte rolling is exclusively P-selectin-dependent.18 Mice were treated with a neutrophil-depleting antibody (RB6-8C5, 10 μg, i.v.) before experiments studying microsphere interactions. Depleting neutrophils in this manner prevents leukocyte rolling without altering microsphere interactions with P-selectin.22

Venules were observed using a Nikon E600 FN microscope (Nikon UK) equipped with a water immersion objective (×20/0.5 W). Passage of fluorescent microspheres through observed venules was observed by dual-flash stroboscopic (100 s−1, Strobex 11360; Chadwick Helmuth, Mountain View, CA) epifluorescence illumination. Rolling leukocytes were observed by bright-field illumination.

Fluorescent images were recorded using a silicone-intensified target camera (VE1000SIT; Dage MTI Inc., MI) and bright-field images were recorded using a charge-coupled device camera (DC330EX; Dage MTI Inc.) onto sVHS videocassettes for later analysis. Microspheres injected into the carotid artery in 50-μl boluses could be observed in the cremaster circulation within 20 seconds and typically circulated for 1 to 2 minutes. These kinetics allowed microspheres with different coatings to be studied within the same vessels. Centerline velocities of observed venules were either measured using commercially available hardware and software (Microvessel Velocity OD-RT System; Circusoft Instrumentation LLC, Hockessin, DE) or estimated from the velocities of free-flowing microspheres occupying a central position in the vessel.

Data Analysis

Data describing behavior of leukocytes and microspheres in venules were obtained using established methods.22,23 Leukocyte rolling fluxes before and after treatments were normalized and expressed as percentage of control rolling. In some studies we directly observed initial tethering of leukocytes to postcapillary venules. Control tethering rate within a defined region was determined before application of treatments. Tethering was then studied within the same region 1 minute after treatments. Tethering data are presented as percentage of control tethers. Velocities of leukocytes and microspheres passing through observed venules were measured from digitized video sequences using freely available software (available on the Internet at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image) and custom written macros.23 For some vessels we also calculated critical velocity (VCrit) as described.24 Velocity of microspheres moving below VCrit cannot be explained by hydrodynamic factors alone and thus implies adhesive interactions between the microsphere and the vessel.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the Instat statistical analysis program (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). One-way analysis of variance was performed and followed by Bonferroni’s test for multiple comparisons. Results were considered significant if P < 0.05.

Results

L-Selectin- and sLex-Mediated Interaction of Fluorescent Microspheres with Surgically Stimulated Cremaster Venules

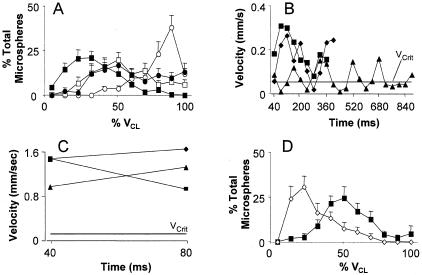

To investigate the potential for PSGL-1-independent, P-selectin-dependent adhesion under the conditions that prevail in living microvessels, we studied the interaction of fluorescent microspheres in mouse cremaster venules as described.22 Microsphere circulation times were limited to 1 to 2 minutes after injection, allowing repeated measurements of all microsphere coatings to be made in the same vessels. Although microsphere injection volumes were typically small and had a negligible effect on blood flow velocity we randomized the order of injections between animals to account for any such effect. Results in Figure 1, A and D, are normalized to the centerline velocity (typically 2 to 4 mm/second) of observed vessels allowing data from a large number of treatments to be compared. All bead coatings were compared in all venules and similar trends were seen when microsphere velocities were compared within single vessels or normalized by VCrit (not shown).

Figure 1.

Interaction of differently coated microspheres in postcapillary venules. Velocities of IgG-coated (open circles), L-selectin-coated (open squares), sLex-coated (closed circles), and L-selectin/sLex-coated (closed squares) microspheres were tracked through surgically stimulated mouse cremaster venules. Average velocity profiles (expressed as percentage of microspheres traveling within defined velocity bins for each venule studied) for each coating are shown in A. Results are presented as percentage of the VCL for the vessels in which velocities were studied. Lower values represent flow closer to the vessel wall and potentially adhesion. Point by point velocity profiles for three representative L-selectin + sLex- and IgG-coated microspheres are shown in B and C, respectively. Velocities here are shown in mm/second and Vcrit for the studied venule is indicated by the horizontal line. Velocities below Vcrit indicate adhesive interaction. Effect of anti-P-selectin antibody (RB40.34, 30 μg/mouse) on average velocity of L-selectin/sLex-coated microspheres is shown in D (open diamonds before RB40.34, closed squares after RB40.34). All observations were repeated in 9 to 12 venules from at least four mice and averages are presented as mean ± SEM. In preliminary experiments we observed direct attachment of some microspheres to rolling neutrophils. To focus on microspheres interacting directly with venules we depleted neutrophils using RB6–8C5. Velocities of sLex + PSGL-1-coated beads in mice with and without neutrophils are compared in supplemental Figure 1.

Microspheres coated with a combination of L-selectin and sLex traveled through postcapillary venules prepared for P-selectin-dependent rolling more slowly than microspheres coated with IgG (Figure 1A). On average, velocities of dual (L-selectin + sLex)-coated microspheres exceeded those typical of leukocytes rolling on P-selectin22 and could not be readily classified as rolling. Closer inspection of video recordings, however, revealed that velocities of these microspheres were irregular and consisted of phases of relatively high velocity, explainable by free flow near to the vessel wall, interspersed with brief dips below the VCrit (indicated by the horizontal line) calculated for the vessel of interest (Figure 1B). Velocities below VCrit cannot be explained by hemodynamic factors alone and are thus indicative of adhesive interaction.1 Limited area of the microscope field, standard video camera frame rate, and high velocity prevented us from measuring movement of IgG-coated microspheres between more than two positions, but velocities of these were routinely well above VCrit (Figure 1C).

Microspheres coated with equivalent densities of either L-selectin or sLex alone traveled faster than those with the dual coating (Figure 1A), but slower than those coated with IgG. L-selectin- or sLex-coated microspheres did not exhibit the irregular velocity profile measured for microspheres with the dual coating (not shown) however, suggesting that any interactions with the vessel wall were too brief to detect with our system. Such interactions may be detectable using high-temporal resolution videomicroscopy, as recently described for L-selectin-dependent adhesion in vitro,25 and might explain the lower average velocity of L-selectin- or sLex-coated microspheres measured using our system that is restricted to 25 frames per second.

Interestingly, the velocity of dual-coated microspheres increased after treatment with a P-selectin-blocking antibody (Figure 1D). All mice were treated with neutrophil-depleting antibody (RB6–8C5) before experiments, which prevents leukocyte rolling but leaves endothelial P-selectin intact.22 Furthermore, centerline velocity in observed vessels was not altered by addition of P-selectin-blocking antibodies (1.5 ± 0.08 mm/second before and 1.3 ± 0.05 mm/second after RB40.34). Increased bead velocity cannot, therefore, be ascribed to improved blood flow or inhibition of leukocyte rolling and thus suggests direct interaction of these microspheres with endothelial P-selectin.

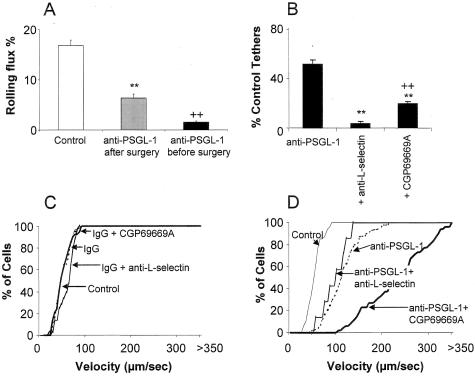

Combined Selectin Inhibitors Abolish P-Selectin-Dependent Leukocyte Rolling

Leukocyte rolling in cremaster venules was predominantly P-selectin-dependent 10 to 30 minutes after surgical trauma (Figure 2A),18 but resistant to L-selectin antibody and the sLex mimetic, CGP69669A (Figure 2B).9,18 Anti-PSGL-1 antibodies inhibit, but do not abolish established surgically induced rolling (Figure 2C).12–15,19 Interestingly, both L-selectin antibody and CGP69669A reduced leukocyte rolling when administered after PSGL-1-antibody (Figure 2C). Videos 1 to 3 compare control rolling with that after PSGL-1 antibody and subsequent CGP69669A. Video 2 shows that a substantial amount of rolling persists after PSGL-1 antibody. This rolling is essentially absent after addition of CGP69669A (video 3). Almost no rolling was seen after a combination of PSGL-1 antibody, L-selectin antibody, and CGP69669A (Figure 2C). PSGL-1-antibody also caused a greater reduction of leukocyte rolling in L-selectin knockout mice than wild-type mice (Figure 2C). Rolling after anti-PSGL-1 treatment was not altered by E-selectin-blocking antibody.

Figure 2.

Effect of combined selectin inhibitors against P-selectin-dependent leukocyte rolling. A: P-selectin antibody (RB40.34, 30 μg/mouse) against surgically induced leukocyte rolling. **, P < 0.001 compared to control rolling. B: Control antibody (rat IgG1κ, 100 μg/mouse), L-selectin antibody (Mel-14, 100 μg/mouse), or CGP69669A (30 mg/kg) against surgically induced rolling. C: Anti-PSGL-1 (2PH1, 100 μg/mouse) alone or combined with L-selectin-blocking antibody, CGP69669A, L-selectin-deficiency, or E-selectin antibody. **, P < 0.01 compared to baseline rolling; ††, P < 0.01 compared to rolling after anti-PSGL-1; #, P < 0.05 compared to anti-PSGL-1 + anti-L-selectin or anti-PSGL-1 + CGP69669A. D: rPSGL-Ig (100 mg/kg) alone or in combination with L-selectin-blocking antibody or CGP69669A. **, P < 0.01 compared to baseline rolling; ††, P < 0.01 compared to rolling after rPSGL-Ig. All results are presented as mean ± SEM for n = 9 to 12 venules from at least four mice per group.

Targeting P-selectin with rPSGL-Ig gave equivalent results (Figure 2D) to those with PSGL-1 antibody. A maximal inhibitory dose of rPSGL-Ig (determined previously19) reduced established leukocyte rolling to a similar level as PSGL-1 antibody. L-selectin antibody or CGP69669A blocked residual rolling (Figure 2D). Residual rolling was not blocked when PSGL-1 antibody was administered to mice that had already received rPSGL-Ig (not shown).

The data presented in Figure 2 are potentially subject to influence by hemodynamic factors including vessel diameter, blood flow velocity, and systemic concentration of leukocytes. These factors were not altered by any of the antibodies or antagonists used (Table 1). Combined treatments were not significantly different from individual treatments (not shown).

Table 1.

Venule Diameter, Blood Flow Velocity, and Systemic WBC Concentration after Different Treatments

| Untreated | IgG | rPSGL-Ig | 2PH1 | MEL14 | CGP69669A | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter (μm) | 36.6 ± 0.9 | 37.2 ± 2.1 | 37.5 ± 1.5 | 35.8 ± 1.2 | 36.3 ± 2.1 | 37.2 ± 4.1 |

| VCL (μm/second) | 3099 ± 168 | 2932 ± 327 | 3193 ± 215 | 3396 ± 315 | 3233 ± 433 | 3220 ± 321 |

| WBC (106/ml) | 6.2 ± 0.2 | 5.7 ± 0.3 | 5.3 ± 0.4 | 6.3 ± 0.4 | 5.9 ± 0.2 | 5.8 ± 0.3 |

L-selectin-dependent leukocyte rolling in venules >1 hour after surgery requires leukocyte-derived PSGL-126 and previous P-selectin/PSGL-1 interaction.26 Leukocyte rolling detected after anti-PSGL-1 or rPSGL-Ig occurs after <1 hour, but is also L-selectin-dependent and probably requires a similar mechanism. In support of this, we find that surgically induced rolling does not develop if PSGL-1 is blocked with 2PH1 before rolling is induced (Figure 3A). The same antibody only produces partial inhibition if given after rolling is established (Figure 3A). Kinetics of antibody binding are unlikely to explain this result because these antibodies all act rapidly (within 1 minute) after intravenous injection. P-selectin-PSGL-1 interaction may be critical for early deposition of leukocytes and leukocyte fragments that can then facilitate later recruitment. The result with anti-PSGL-1 pretreatment reconciles the discrepancy between anti-PSGL-1 antibodies and PSGL-1 knockout mice and suggests that PSGL-1-independent leukocyte rolling on P-selectin can occur, but only if preceded by an earlier PSGL-1-dependent step.

Figure 3.

Further effects of selectin inhibitors on P-selectin-dependent leukocyte rolling. A: Effect of anti-PSGL-1 (2PH1, 100 μg/mouse) given before or 30 minutes after cremaster surgery. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 5 to 6. **, P < 0.01 compared to control rolling; ++, P < 0.01 compared to anti-PSGL-1 after surgery. B: Effect of anti-PSGL-1 (2PH1, 100 μg/mouse) and subsequent anti-L-selectin (Mel-14, 100 μg/mouse) or sLex mimetic (CGP69669A, 30 mg/kg) on tethering. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 6 to 8. **, P < 0.01 compared to tethering after anti-PSGL-1 alone; ++, P < 0.01 compared to tethering after anti-PSGL-1 + anti-L-selectin. C and D: Rolling velocities before and after administration of IgG control antibody (100 μg/mouse, rat IgG1κ) or anti-PSGL-1, and also after subsequent administration of anti-L-selectin antibody (MEL-14, 100 μg/mouse) or CGP69669A (30 mg/kg). Velocity results are presented as cumulative velocity histograms for at least 50 cells per treatment.

L-selectin-dependent tethering followed by P-selectin-dependent rolling on sLex-bearing structures (eg, PSGL-1 and other glycoproteins on leukocytes) is a likely mechanism for anti-PSGL-1/rPSGL-Ig-resistant leukocyte rolling. We therefore observed leukocyte tether formation directly as described.19 PSGL-1 antibody reduced tethering by ∼50% in mice with established P-selectin-dependent rolling (Figure 3B), whereas a combination of PSGL-1 and L-selectin antibodies effectively abolished tethering. CGP69669A also reduced observable tether formation in PSGL-1 antibody treated mice, but less effectively than L-selectin antibodies.

We also investigated the consequences of anti-L-selectin and CGP69669A on leukocyte-rolling velocity. Consistent with their lack of effect on leukocyte-rolling flux, neither L-selectin or CGP69669A altered rolling velocity if given in combination with control antibody (Figure 3C). Anti-PSGL-1 antibody increased rolling velocity in surgically stimulated cremaster venules (Figure 3D). Subsequently added L-selectin antibody did not alter rolling velocity whereas CGP69669A caused a dramatic further velocity increase (Figure 3D). E-selectin-blocking antibody did not alter leukocyte-rolling velocity in these experiments. These findings support the conclusion that L-selectin is primarily required for tethering the leukocyte to endothelium and that subsequent rolling is determined by P-selectin-dependent recognition of sLex-bearing ligands on the leukocyte.

Discussion

The dominant mechanism supporting rapid induction of leukocyte rolling in postcapillary venules has been clear for some time. In surgically stimulated venules P-selectin rapidly translocates to the luminal surface of endothelial cells, interacts with constitutively expressed PSGL-1 on leukocytes, and initiates rolling within minutes.14,16,18 Our data do not refute the importance of this mechanism, but do suggest that additional mechanisms compensate when P-selectin-PSGL-1 interaction is inhibited by antibodies targeting the N-terminus of PSGL-1 or the selectin antagonist, rPSGL-Ig. We have demonstrated that beads coated with a combination of L-selectin and sLex engage in measurable interactions with P-selectin in vivo. We have also confirmed that some P-selectin-dependent leukocyte rolling persists after treatment with PSGL-1 antibody or rPSGL-Ig and that this rolling can be abolished by treatments (L-selectin antibody, CGP69669A) that do not usually influence P-selectin-dependent leukocyte rolling in vivo.

The surface of a leukocyte is decorated with many structures capable of initiating or stabilizing interactions with postcapillary venules. One strategy for studying the contributions of individual components of that surface is to coat artificial microspheres with purified or recombinant versions of molecules of interest. We and others have used this strategy in the past to investigate the capacity of PSGL-1 and other adhesion molecules to mediate rolling in vitro27–30 and in vivo.20,22,31 Ideally, the properties (size, ligand density, deformabilty, and so forth) of microspheres used for such investigations will closely match those of leukocytes, allowing direct comparisons to be made. For this reason, most in vitro investigations have used microspheres of 8 to 10 μm in diameter. Smaller (1 to 2 μm) microspheres must be used for in vivo experiments however, because trapping in capillaries prevents larger microspheres from reaching postcapillary venules. Leukocytes overcome this trapping by deforming as they pass through capillaries. Our current results with microspheres suggest that PSGL-1-independent interactions with P-selectin can occur via L-selectin and sLex and are also consistent with the subsequent studies in which L-selectin blockade or CGP69669A inhibit P-selectin-dependent leukocyte rolling after PSGL-1 inhibition. Nevertheless, it should be noted that because of size differences, greater forces will be exerted on interacting leukocytes than microspheres.

There is a discrepancy between studies using PSGL-1-deficient mice and antibodies raised against the N-terminus of PSGL-1. Like P-selectin-deficient mice, PSGL-1-deficient mice have little or no surgically induced rolling.16 In contrast, PSGL-1-blocking antibodies only partially inhibit established surgically induced rolling in wild-type mice.12,14,15 One interpretation of this is that PSGL-1 is the only important P-selectin ligand on rolling neutrophils, but that it can interact with endothelial P-selectin in two ways. Optimal type 1 interaction involving the widely studied N-terminus of PSGL-1 dominates when present, whereas a different type 2 interaction is revealed if the type 1 interaction is blocked by antibody. Our results suggest that the type 2 mechanism is distinct from type 1 because it is sensitive to L-selectin blockade or a sLex mimetic (CGP69669A) previously found to only affect E-selectin-dependent rolling.

Susceptibility of PSGL-1 antibody/rPSGL-Ig resistant, P-selectin-dependent rolling to the sLex mimetic CGP69669A suggests that the mechanisms mediating type-2 rolling involve simpler molecular interactions than those between P-selectin and fully functional PSGL-1. This presents the question of why PSGL-1 should be the only molecule capable of supporting residual leukocyte rolling on P-selectin when many other sialylated/fucosylated molecules (eg, L-selectin,32 ESL-1,33 CD24,34 and CD1835,36) exist on the surface of leukocytes and are capable of interacting with the selectins. Explaining PSGL-1-independent, P-selectin-dependent leukocyte rolling is not straightforward, given the absence of surgically induced rolling in PSGL-1-deficient mice,16 but we believe that our findings with PSGL-1 antibody pretreatment and recent data from others26 offer a plausible solution.

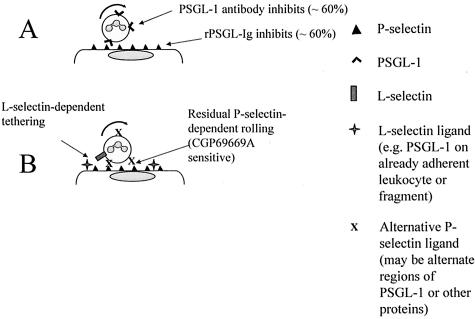

Consistent with earlier in vitro studies,37–39 Sperandio and colleagues26 have demonstrated that >1 hour after surgery, attached leukocytes and leukocyte fragments present selectin ligands (primarily PSGL-1) to other leukocytes thus promoting further recruitment in postcapillary venules. If attachment of the first wave of leukocytes is prevented by P-selectin antibody26 then this secondary capture mechanism is prevented. Such rolling is absent from PSGL-1-deficient mice because PSGL-1 is critically required for the first wave of recruitment. This led us to hypothesize that PSGL-1 antibody, given as a pretreatment, would be more effective than the same dose of the same antibody given after rolling had established. Consistent with this, PSGL-1 pretreatment essentially reproduced the phenotype of the PSGL-1 knockout mouse, giving a much stronger level of inhibition than the same antibody given after rolling was established. We therefore suggest that leukocyte rolling in vivo is initially fully dependent on both P-selectin and PSGL-1 but becomes partially PSGL-1-independent as the response develops. Applying this model to the schematic in Figure 4, we propose that L-selectin-dependent tethering to PSGL-1 on already adherent leukocytes (or leukocyte fragments) is followed by binding of P-selectin to sLex-bearing ligands that may include but are not entirely limited to PSGL-1.

Figure 4.

A: Type 1 interaction. P-Selectin/PSGL-1 interaction dominates leukocyte rolling in the early stages of an acute inflammatory response. This rolling can be abolished by P-selectin-blocking antibodies, but is only partially inhibited by anti-PSGL-1 antibody or rPSGL-Ig. B: Type 2 interaction. Residual, anti-PSGL-1/rPSGL-Ig-resistant rolling requires L-selectin for tethering and can be inhibited by CGP69669A suggesting importance of sialylated, fucosylated glycans.

We are not the only investigators to note a partial effect of PSGL-1-blocking antibodies against P-selectin-dependent leukocyte rolling. Sperandio and colleagues15 found that antibody 4RA10 against PSGL-1 gave 60 to 70% inhibition of leukocyte rolling in surgically stimulated cremaster venules of wild-type mice, but essentially 100% inhibition in similarly treated vessels of core-2 glucosaminyltransferase (C2GlcNAcT-I)-deficient mice. These data are consistent with and extend our own, in that they implicate a core-2 O-glycan in the rolling that prevails when type 1 P-selectin/PSGL-1 interaction is inhibited. P-Selectin-dependent rolling in the mouse cremaster muscle is virtually absent in mice lacking fucosyltransferase VII,40 implicating fucose as an absolute requirement for both type 1 and type 2 rolling on P-selectin in vivo.

PSGL-1-blocking antibodies and rPSGL-Ig do not target the same molecules but do inhibit the same event (ie, P-selectin/PSGL-1 binding). PSGL-1-blocking antibodies bind to the high-affinity P-selectin recognition domain near the N-terminus of PSGL-1,14,41 whereas rPSGL-Ig is directed toward the high-affinity binding site of endothelial P-selectin. Our previous observations that rPSGL-Ig19 and other PSGL-1-based inhibitors do not abolish P-selectin-dependent rolling in vivo suggested to us that P-selectin recognizes the high-affinity binding domain of PSGL-1 in one way and other ligands in quite another. Such a possibility is supported by the three-dimensional structures of P-selectin co-crystallized with different ligands.42 P-selectin co-crystallized with sLex closely resembles the conformation of unligated P-selectin and the three-dimensional structure of E-selectin co-crystallized with sLex. P-Selectin bound to a high-affinity fragment of PSGL-1, on the other hand, adopts a markedly different conformation permitting extended contacts with the elements of PSGL-1 required for high-affinity binding. Preferred conformations adopted by membrane-bound P-selectin under physiological conditions are not known. Our data support the possibility of a high-affinity (type 1) conformation that dominates leukocyte rolling under normal circumstances and is inhibited by PSGL-1-blocking antibodies and by rPSGL-Ig, and a low-affinity (type 2) conformation that can be inhibited by sLex and similar molecules.

The rPSGL-Ig used in our investigations carries all of the posttranslational modifications required for high-affinity interaction with P-selectin including expression of sialyl Lewisx or similar structures.43 Why this does not confer the ability to abolish P-selectin-dependent leukocyte rolling in vivo, unless additional free sLex mimetic is given, requires further consideration. Clearly, CGP69669A added at 30 mg/kg represents a vast molar excess of sLex-like material, when compared with amounts of sLex (or similar structures) attached to 30 mg/kg of rPSGL-Ig. Thus, we simply may not be giving enough carbohydrate to prevent type 2 interactions when treating with rPSGL-Ig at 30 to 100 mg/kg. Alternatively, P-selectin in the type 2 conformation may be inaccessible to rPSGL-Ig. Testing these possibilities is not currently possible because practical reasons prevent us from administering doses of rPSGL-Ig higher than 100 mg/kg.

In summary, we find that a combination of sLex and L-selectin support detectable interaction of microspheres with P-selectin in postcapillary venules in vivo, suggesting the possibility of a cooperative mechanism for P-selectin-dependent/PSGL-1-independent rolling in vivo. Cooperation between L-selectin and a sLex-bearing ligand also supports significant leukocyte rolling although such interaction is only revealed after inhibition of high-affinity P-selectin/PSGL-1 interaction. P-Selectin inhibitors that target type 1 P-selectin/PSGL-1 interaction do not inhibit all P-selectin-dependent leukocyte rolling, whereas inhibitors targeting type 2 interaction have no measurable effect unless combined with an inhibitor of type 1 interaction. These findings may have important implications for the efficacy of P-selectin inhibitors in clinical trials.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Keith Norman, Clinical Sciences Centre, Northern General Hospital, Sheffield, S5 7AU, UK. E-mail: k.norman@shef.ac.uk.

Supported by a project grant from the British Heart Foundation (PG/2000026). V.C.R. is the recipient of an Intermediate Fellowship from the British Heart Foundation (FS/02004). Equipment was funded by grant 057108 from the Wellcome Trust.

References

- Ley K. Leukocyte recruitment as seen by intravital microscopy. Ley K, editor. Oxford: Oxford University Press,; Physiology of Inflammation. 2001:pp 303–337. [Google Scholar]

- Manka D, Collins RG, Ley K, Beaudet AL, Sarembock IJ. Absence of P-selectin, but not intercellular adhesion molecule-1, attenuates neointimal growth after arterial injury in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 2001;103:1000–1005. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.7.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RG, Velji R, Guevara NV, Hicks MJ, Chan L, Beaudet AL. P-Selectin or intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 deficiency substantially protects against atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2000;191:189–194. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.1.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger PC, Wagner DD. Platelet P-selectin facilitates atherosclerotic lesion development. Blood. 2003;101:2661–2666. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JW, Barringhaus KG, Sanders JM, Hesselbacher SE, Czarnik AC, Manka D, Vestweber D, Ley K, Sarembock IJ. Single injection of P-selectin or P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 monoclonal antibody blocks neointima formation after arterial injury in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 2003;107:2244–2249. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000065604.56839.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanguay JF, Krucoff MW, Gibbons RJ, Chavez E, Liprandi AS, Molina-Viamonte V, Aylward PE, Lopez-Sendon JL, Holloway DS, Shields K, Yu JS, Loh E, Baran KW, Bethala VK, Vahanian A, White HD. Efficacy of a novel P-selectin antagonist, rPSGL-Ig for reperfusion therapy in acute myocardial infarction: the RAPSODY trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:404–405. [Google Scholar]

- Shah PK. Myocardial infarction and ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:375–377. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00677-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppanen A, White SP, Helin J, McEver RP, Cummings RD. Binding of glycosulfopeptides to P-selectin requires stereospecific contributions of individual tyrosine sulfate and sugar residues. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39569–39578. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman KE, Anderson GP, Kolb H, Ley K, Ernst BE. Sialyl Lewisx (sLex) and a sLex mimetic, CGP69669A, disrupt E-selectin-dependent rolling in vivo. Blood. 1998;91:475–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sako D, Comess KM, Barone KM, Camphausen RT, Cumming DA, Shaw GD. A sulfated peptide segment at the amino terminus of PSGL-1 is critical for P-selectin binding. Cell. 1995;83:323–331. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppanen A, Mehta P, Ouyang YB, Ju T, Helin J, Moore KL, van Die I, Canfield WM, McEver RP, Cummings RD. A novel glycosulfopeptide binds to P-selectin and inhibits leukocyte adhesion to P-selectin. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24838–24848. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.24838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman KE, Moore KL, McEver RP, Ley K. Leukocyte rolling in vivo is mediated by P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1. Blood. 1995;86:4417–4421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks AE, Leppanen A, Cummings RD, McEver RP, Hellewell PG, Norman KE. Glycosulfopeptides modelled on P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 inhibit P-selectin-dependent leukocyte rolling in vivo. FASEB J. 2002;16:1461–1462. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0075fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges E, Eytner R, Moll T, Steegmaier M, Campbell MA, Ley K, Mossmann H, Vestweber D. The P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 is important for recruitment of neutrophils into inflamed mouse peritoneum. Blood. 1997;90:1934–1942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperandio M, Thatte A, Foy D, Ellies LG, Marth JD, Ley K. Severe impairment of leukocyte rolling in venules of core 2 glucosaminyltransferase-deficient mice. Blood. 2001;97:3812–3819. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.12.3812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Hirata T, Croce K, Merrill-Skoloff G, Tchernychev B, Williams E, Flaumenhaft R, Furie BC, Furie B. Targeted gene disruption demonstrates that P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 (PSGL-1) is required for P-selectin-mediated but not E-selectin-mediated neutrophil rolling and migration. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1769–1782. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.12.1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers SD, Camphausen RT, Hammer DA. Sialyl Lewis(x)-mediated, PSGL-1-independent rolling adhesion on P-selectin. Biophys J. 2000;79:694–706. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76328-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley K, Bullard DC, Arbones ML, Bosse R, Vestweber D, Tedder TF, Beaudet AL. Sequential contribution of L- and P-selectin to leukocyte rolling in vivo. J Exp Med. 1995;181:669–675. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks AER, Nolan SL, Ridger VC, Hellewell PG, Norman KE. Recombinant P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 directly inhibits leukocyte rolling by all three selectins in vivo: complete inhibition of rolling is not required for anti-inflammatory effect. Blood. 2003;101:3249–3256. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperandio M, Forlow SB, Thatte J, Ellies LG, Marth JD, Ley K. Differential requirements for core2 glucosaminyltransferase for endothelial L-selectin ligand function in vivo. J Immunol. 2001;167:2268–2274. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbonés ML, Ord DC, Ley K, Ratech H, Maynard-Curry C, Otten G, Capon DJ, Tedder TF. Lymphocyte homing and leukocyte rolling and migration are impaired in L-selectin-deficient mice. Immunity. 1994;1:247–260. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman KE, Katopodis AG, Thoma G, Kolbinger F, Hicks AE, Cotter MJ, Pockley AG, Hellewell PG. P-Selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 supports rolling on E- and P-selectin in vivo. Blood. 2000;96:3585–3591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman KE. An effective and economical solution for digitizing and analysing video-recordings of the microcirculation. Microcirculation. 2001;8:243–249. doi: 10.1038/sj/mn/7800082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley K, Gaehtgens P. Endothelial, not hemodynamic differences are responsible for preferential rolling in venules. Circ Res. 1991;69:1034–1041. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.4.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwir O, Solomon A, Mangan S, Kansas GS, Schwarz US, Alon R. Avidity enhancement of L-selectin bonds by flow: shear-promoted rotation of leukocytes turn labile bonds into functional tethers. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:649–659. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperandio M, Smith ML, Forlow SB, Olson TS, Xia L, McEver RP, Ley K. P-Selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 mediates L-selectin-dependent leukocyte rolling in venules. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1355–1363. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz DJ, Greif DM, Ding H, Camphausen RT, Howes S, Comess KM, Snapp KR, Kansas GS, Luscinskas FW. Isolated P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 dynamic adhesion to P- and E-selectin. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:509–519. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.2.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunk DK, Hammer DA. Sialyl Lewis(x)/E-selectin-mediated rolling in a cell-free system. Biophys J. 1996;71:2902–2907. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79487-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunk DK, Hammer DA. Quantifying rolling adhesion with a cell-free assay: E-selectin and its carbohydrate ligands. Biophys J. 1997;72:2820–2833. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78924-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall BT, Long M, Piper JW, Yago T, McEver RP, Zhu C. Direct observation of catch bonds involving cell-adhesion molecules. Nature. 2003;423:190–193. doi: 10.1038/nature01605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burch EE, Patil VRS, Camphausen RT, Kiani MF, Goetz DJ. The N-terminal peptide of PSGL-1 can mediate adhesion to trauma-activated endothelium via P-selectin in vivo. Blood. 2002;100:531–538. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.2.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picker LJ, Warnock RA, Burns AR, Doerschuk CM, Berg EL, Butcher EC. The neutrophil selectin LECAM-1 presents carbohydrate ligands to the vascular selectins ELAM-1 and GMP-140. Cell. 1991;66:921–933. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90438-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steegmaier M, Levinovitz A, Isenmann S, Borges E, Lenter M, Kocher HP, Kleuser B, Vestweber D. The E-selectin-ligand ESL-1 is a variant of fibroblast growth factor. Nature. 1995;373:615–620. doi: 10.1038/373615a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aigner S, Ruppert M, Hubbe M, Sammar M, Sthoeger Z, Butcher EC, Vestweber D, Altevogt P. Heat stable antigen (mouse CD24) supports myeloid cell binding to endothelial and platelet P-selectin. Int Immunol. 1995;7:1557–1565. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.10.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crutchfield KL, Shinde Patil VR, Campbell CJ, Parkos CA, Allport JR, Goetz DJ. CD11b/CD18-coated microspheres attach to E-selectin under flow. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67:196–205. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asada M, Furukawa K, Kantor C, Gahmberg CG, Kobata A. Structural study of the sugar chains of human leukocyte cell adhesion molecules CD11/CD18. Biochemistry. 1991;30:1561–1571. doi: 10.1021/bi00220a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargatze RF, Kurk S, Butcher EC, Jutila MA. Neutrophils roll on adherent neutrophils bound to cytokine-induced endothelial cells via L-selectin on the rolling cells. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1785–1792. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alon R, Fuhlbrigge RC, Finger EB, Springer TA. Interactions through L-selectin between leukocytes and adherent leukocytes nucleate rolling adhesions on selectins and VCAM-1 in shear flow. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:849–865. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.3.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walcheck B, Moore KL, McEver RP, Kishimoto TK. Neutrophil-neutrophil interactions under hydrodynamic shear stress involve L-selectin and PSGL-1—a mechanism that amplifies initial leukocyte accumulation on P-selectin in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1081–1087. doi: 10.1172/JCI118888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maly P, Thall AD, Petryniak B, Rogers GE, Smith PL, Marks RM, Kelly RJ, Gersten KM, Cheng GY, Saunders TL, Camper SA, Camphausen RT, Sullivan FX, Isogai Y, Hindsgaul O, von Andrian UH, Lowe JB. The alpha(1,3)fucosyltransferase Fuc-TVII controls leukocyte trafficking through an essential role in L-, E-, and P-selectin ligand biosynthesis. Cell. 1996;86:643–653. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenette PS, Denis CV, Subbarao S, Vestweber D, Wagner DD. P-Selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 is expressed on platelets and can mediate platelet-endothelial interactions in vivo. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1413–1422. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.8.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somers WS, Tang J, Shaw GD, Camphausen RT. Insights into the molecular basis of leukocyte tethering and rolling revealed by structures of P- and E-selectin bound to sLex and PSGL-1. Cell. 2000;103:467–479. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00138-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppihimer MJ, Schaub RG. Soluble P-selectin antagonist mediates rolling velocity and adhesion of leukocytes in acutely inflamed venules. Microcirculation. 2001;8:15–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]