Abstract

Medulloblastomas (MBs), the most frequent malignant brain tumors of childhood, presumably originate from cerebellar neural precursor cells. An essential fetal mitogen involved in the pathogenesis of different embryonal tumors is insulin-like growth factor II (IGF-II). We screened human MB biopsies of the classic (CMB) and desmoplastic (DMB) variants for IGF2 transcripts of the four IGF2 promoters. We found IGF2 transcription from the imprinted promoter P3 to be significantly increased in the desmoplastic variant compared to the classic subgroup. This was not a result of loss of imprinting of IGF2 in desmoplastic tumors. We next examined the interaction of IGF-II and Sonic hedgehog (Shh), which serves as a critical mitogen for cerebellar granule cell precursors (GCPs) in the external granule cell layer from which DMBs are believed to originate. Mutations of genes encoding components of the Shh-Patched signaling pathway occur in ∼50% of DMBs. To analyze the effects of IGF-II on Hedgehog signaling, we cultured murine GCP and human MB cells in the presence of Shh and Igf-II. In GCPs, a synergistic effect of Shh and Igf-II on proliferation and gli1 and cyclin D1 mRNA expression was found. Igf-II, but not Shh, induced phosphorylation of Akt and its downstream target Gsk-3β. In six of nine human MB cell lines IGF-II displayed a growth-promoting effect that was mediated mainly through the IGF-I receptor. Together, our data point to an important role of IGF-II for the proliferation control of both cerebellar neural precursors and MB cells.

Medulloblastomas (MBs) represent the most frequent malignant brain tumors of childhood with an incidence of five cases/million children.1 Histologically, the classic MB (CMB) and the desmoplastic MB (DMB) variants can be defined.2 Both appear to arise from primitive neuroectodermal cells. For DMB, there is strong evidence for an origin from granule cell precursors (GCPs) of the external granule cell layer of the cerebellum.3 This variant occurs in patients with the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome who carry Patched (PTCH) germ line mutations,4 and a substantial fraction of sporadic DMBs have mutations in this tumor suppressor gene.5–8 PTCH encodes a receptor for Hedgehog. Its binding abrogates a negative effect of Patched on Smoothened. In its active state, Smoothened transduces the signal to the nucleus, where specific target genes are activated by the transcription factor Gli1.9,10 This signaling pathway has been shown to be essential in embryogenesis and for the proliferation of GCPs in the cerebellum (reviewed in Ruiz i Altaba et al9).

Inactivation of one ptc allele in mice leads to the development of MBs or rhabdomyosarcomas in up to 30% of the animals.11,12 Because these tumors, especially rhabdomyosarcomas, show increased expression of insulin-like growth factor 2 (igf2) mRNA, Hahn and colleagues13 crossed a ptc+/− strain with igf2+/− mice. As the incidence of tumors in ptc+/− mice on the igf2-null background significantly decreased, it was postulated that igf2 serves as a target gene for Sonic hedgehog (Shh)-signaling, and that it might be indispensable for the formation of both tumor entities. On the other hand, microarray analyses of human brain tumors showed, additionally to the increased transcription of known Hedgehog target genes such as GLI1 and PTCH, up-regulation of IGF2 in the desmoplastic tumor variant but not in CMB.14

The IGF2 gene encodes a regulatory peptide (IGF-II) critical for normal fetal growth. It has been shown to be implicated in tumor progression in a variety of human neoplasms, eg, Wilms’ tumors and rhabdomyosarcomas.15 IGF2 transcription is controlled by four distinct promoters, P1 to P4, of which promoters P2, P3, and P4 are epigenetically regulated by genomic imprinting.16,17 The IGF-II protein can bind to different receptors: the IGF-I receptor (IGF-IR) has classically been regarded as the major mediator of its proliferative effect; the insulin receptor (IR), especially its isoform A (IR-A), which resembles the IGF-IR in its effect; and the IGF-II receptor (IGF-IIR), which internalizes IGF-II into the cell, thereby regulating its extracellular concentration, and eventually leading to its lysosomal degradation.

In this study, we analyzed a panel of human MB biopsies and human fetal cerebellar samples for IGF2 mRNA expression and imprinting status. Furthermore, we examined functional effects of IGF-II and Shh in human MB cell lines and murine GCPs. We found that IGF-II is a potent mitogen in MB and that it acts synergistically with Shh on cerebellar GCPs, from which MBs are thought to arise.

Materials and Methods

Patients, Tumors, Cell Lines

We examined a total of 32 human MB biopsies (20 of classic and 12 of desmoplastic histology). Because MBs represent embryonal neoplasms, two fetal human cerebellar samples (15.5 and 18 weeks of gestational age) were included in the study as control tissues. The latter have kindly been provided by Dr. C.G. Goodyer, Montreal Children’s Hospital, McGill University, Montreal, Canada. Most of the MB patients were enrolled in the multicenter treatment study for pediatric malignant brain tumors (HIT) of the German Society of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology. Constitutional DNA was available in most cases from peripheral blood. All tumors were subjected to neuropathological characterization and were classified according to the World Health Organization guidelines. The continuous MB cell lines analyzed were D283MED, Daoy, D425MED, D556MED, MHH-MED-1, and MHH-MED-32,6,18–21 as well as MEB-MED-8A, MEB-MED-8S, and 1580WÜ (T. Pietsch, unpublished).

DNA Extraction

DNA was isolated from peripheral blood and tumor tissue by a standard proteinase K/sodium dodecyl sulfate digestion followed by phenol/chloroform extraction. Tissue fragments selected for DNA extraction were checked by frozen sectioning to ensure that they consisted either of tumor or cerebellar tissue. Only fragments with a tumor cell content of at least 80% were included.

RNA Extraction, cDNA Preparation, and Semiquantitative Reverse Transcriptase (RT)-Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

Twenty-seven tumors were included in the analysis of promoter-specific IGF2 expression; 15 were classified as classic and 12 as desmoplastic MB. Two human fetal cerebellar tissue specimens and seven MB cell lines were also included in the analysis. To verify their composition, tumor tissue samples were examined by frozen section before RNA extraction. Only fragments with a tumor cell content of at least 80% were subjected to RNA extraction. Total cellular RNA was extracted with the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To remove any contaminating DNA, the samples were digested with DNase I (Promega, Mannheim, Germany). Subsequently, DNase was removed by an additional round of Trizol extraction. To quantify the distinct IGF2 transcripts resulting from differential promoter usage by competitive RT-PCR, exogenous RNA standards for these transcripts and β2-microglobulin, a housekeeping gene, were generated with internal deletions by in vitro mutagenesis and in vitro transcription.22,23 Briefly, mutagenesis and T7 promoter addition were performed in a single PCR reaction with a single reverse primer for mutagenesis for all four IGF2 transcripts and the promoter-specific forward primers with a T7 promoter sequence added at the 5′ end. Templates (0.5 μg) were subjected to in vitro transcription (T7-Polymerase kit; Fermentas, St. Leon-Rot, Germany), subsequent DNase digestion, purification (RNeasy Quickspin columns; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and spectrophotometric determination of the competitors’ concentration. To ensure coverage of the equimolar range of the competitors and the corresponding RNA transcripts in the final assay we performed titration experiments. Reverse transcription was performed with 250 ng of a RNA pool from tumor and normal cerebellar tissues and serial dilutions of the competitors (5 × 10−10 to 5 × 10−6 mg) using the Superscript II preamplification system (Life Technologies) with random hexamers as primers. Subsequent PCR amplification of all products was performed with a fluorescently labeled reverse primer. Primer sequences and PCR conditions are described elsewhere.22 Products were separated and analyzed in 4.5% denaturating acrylamide gels on a semiautomated DNA sequencer (ABI 377) using the Genescan software (ABI, Darmstadt, Germany). Optimal titration was defined as the point of equal signal intensity of exogenous competitor and target transcript. Eventually, 250 ng of RNA from each tumor or cerebellar sample were reverse-transcribed together with pre-evaluated amounts of the exogenous standards using the same system as above. Each standard’s concentration was now chosen according to the optimal titration point found in the titration experiment. A wide range of competitor concentrations was used to ensure optimal coverage of even higher fluctuations. Amplification and analysis were performed as described for the titration experiment. Each PCR was performed at least in triplicates. RNA expression levels were calculated as follows: (TARGETsample/TARGETstandard)/ (β2-microglobulinsample/β2-microglobulinstandard) to take into account possible differences in the amounts of tissue RNA subjected to reverse transcription. Optimal titration for the genes in most of the samples was found for the following competitor amounts: 50 pg for β2-microglobulin, ∼100 fg for IGF2-P1 and IGF2-P4, 5 fg for IGF2-P2, and ∼50 pg for IGF2-P3.

Analysis of IGF2 Imprinting

Imprinting of IGF2 was examined in 29 samples for which RNA was available. For this purpose, we first analyzed genomic DNA from these cases to determine which ones were informative for the known transcribed exonic ApaI RFLP in exon 9 of the IGF2 gene. PCR, digestion, and electrophoresis were performed as described elsewhere.24 For heterozygotes, the analysis was repeated with cDNA to assess the allelic expression pattern. In case of biallelic expression, the experiment was repeated without previous reverse transcription to exclude contamination with genomic DNA. The samples that were not informative for the ApaI RFLP were subjected to the analysis of a dinucleotide repeat region in exon 9 of the IGF2 gene, which harbors two sequence polymorphisms.24 Two separate PCR fragments were amplified for the 5′ and the 3′ polymorphism. Primers were 5′-ACTTTATGCATCCCCGCAGCTACA-3′ and 5′-TTCGTGTGTGCTGTGTTCGCGTG-3′ (fragment 1) and 5′-CACACAGCACACACACG CGAAC-3′ and 5′-AGAATCTTAGCGGGACTTTGGCCT-3′ (fragment 2). In each PCR, one primer was labeled with a fluorescent dye. Products were separated and analyzed in 4.5% denaturating acrylamide gels on a semiautomated DNA sequencer (ABI 377) essentially as described before using the Genescan software (ABI).24

Cultivation and Treatment of Human MB Cell Lines, 3H-Thymidine Uptake Assays

MB cell lines were cultured as described before under serum-supplemented conditions.6 Prior to experiments the cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in serum-free neurobasal medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 0.5 mmol/L l-glutamine (Life Technologies). For 3H-thymidine uptake assays, cells were grown in 96-well dishes (Nunc, Wiesbaden, Germany) in a volume of 100 μl and a concentration of 3 × 105 cells/ml (except 2 × 105 cells/ml for Daoy, D283MED, and MEB-MED-8A). Treatments were performed with 0.625 μg/ml of recombinant human Shh-N (R&D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany) and/or 200 ng/ml of recombinant human IGF-II (R&D Systems). The murine monoclonal IGF-I receptor antibody α-IR-3 (Calbiochem, Schwalbad, Germany) and the murine monoclonal insulin receptor antibody AB-3 (Neomarkers, Fremont, CA) were used in a final concentration of 1 μg/ml. A mouse IgG1-κ antibody (MOPC-21) (Sigma, Tantkirchen, Germany) was used for control experiments. Treatments were performed for 48 hours, experiments were performed at least in quadruplicates. For 3H-thymidine uptake assays, 12.5 μl of medium containing 3H-thymidine (3 μCi/ml, Amersham, Freiburg, Germany) was added for the last 12 hours of treatment. Cells were collected using a cell harvester (Packard Filtermate 196, Perkin Elmer Life Sciences, Zarentem, Belgium) and 3H-thymidine uptake was determined in a microplate scintillation and luminescence counter (Topcount NXT, Packard) using a specific software (Topcount NXT software, version 1.6). 3H-Thymidine uptake was normalized to the basal uptake in the control experiment. For experiments involving protein extraction, cells were cultured in 12-well dishes in the same concentration as indicated above.

Preparation, Cultivation, and Treatment of Murine GCPs

Primary cultures of murine GCPs were prepared from 8-day-old F1 offspring of C57BI/Bom × CH3 mice as described before.25,26 Cerebella were dissected under sterile conditions in modified Hanks’ balanced salt solution (4.17 mmol/L NaHCO3, 0.7 Na2HPO4, pH 7.2) and carefully freed of meninges. Tissue was incubated with trypsin (0.1% in PBS containing 1.06 mmol/L ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid) for 20 minutes at 37°C. The trypsin action was stopped by adding a double volume of soy bean trypsin inhibitor (Invitrogen) and bovine serum albumin (both at 8 mg/ml) in PBS. Tissue fragments were triturated with a wide-bore plastic pipette and then passed through a nylon mesh (250-μm pore size). Dissociated cells were pelleted by centrifugation, resuspended, and grown in serum-free neurobasal medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 2 mmol/L l-glutamine and 25 μmol/L l-glutamic acid (Life Technologies) in a concentration of 3 × 106 cells/ml. For 3H-thymidine uptake assays, cells were grown in a volume of 100 μl in 96-well dishes (Nunc) coated with 20 μg/ml of poly-l-lysine (Sigma). They were treated with variable concentrations of recombinant murine Shh-N (R&D Systems; for concentrations see Results) and 200 ng/ml of recombinant murine Igf-II (R&D Systems), which turned out to be the optimal concentration in terms of induction of proliferation in previous titration experiments. For blockage of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway, cells were treated with Shh and/or Igf-II and co-incubated with different concentrations of LY294002 (15 μmol/L, 10 μmol/L, and 5 μmol/L) (New England Biolabs, Frankfurt, Germany). Dimethyl sulfoxide as solvent was used in control experiments in appropriate concentrations. Cells were incubated with 3H-thymidine and their proliferative activity was determined as described above. For experiments involving mRNA or protein extraction, cells were grown in six-well dishes coated with poly-l-lysine (as above) in a volume of 3 ml and were treated with 200 ng/ml of Igf-II and/or 0.625 μg/ml of Shh-N. An untreated control was included. mRNA was extracted after 7 and 18 hours using the Trizol reagent (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell culture for mRNA extraction was always paralleled by a 3H-thymidine uptake assay that served as a control for effective treatment and culture quality.

Semiquantitative PCR in differentially treated GCPs was performed as described above for human tissue samples. Target genes analyzed for transcriptional activity were selected according to their known transcriptional response to Shh: gli1, cyclin D1, and N-myc mRNA expression were analyzed and normalized to the expression of the β2-microglobulin housekeeping gene.26–29 Furthermore, igf2 transcriptional activity was analyzed. Primer sequences and PCR conditions are shown in Table 1. Each PCR was performed at least six times. Optimal titration was observed with 50 pg of competitor for β2-microglobulin and gli1 and with 5 pg for cyclin D1, N-myc, and igf2.

Table 1.

Primer Sequences and PCR Conditions Used in the Competitive RT-PCR Assay of Known Shh-Responsive Transcripts and igf2 in GCP

| Primer designation | Sequence 5′ to 3′ | PCR conditions | Fragment size |

|---|---|---|---|

| igf2-all-f | TGCTGCATCGCTGCTTACGG | 1.0 mM MgCl2; 40 cycles 94°C× 35 seconds/58°C× 40 seconds/72°C 40 seconds | 153 bp/143 bp |

| igf2-all-r | GCAGCACTCTTCCACGATGC | ||

| cyclin D1-f | CGTGCAGAAGGAGATTGTGC | 1.0 mM MgCl2; 40 cycles 94°C× 35 seconds/58°C× 40 seconds/72°C 40 seconds | 196 bp/178 bp |

| cyclin D1-r | CTTAGAGGCCACGAACATGC | ||

| N-myc-f | CTCAGATGATGAGGATGACG | 1.0 mM MgCl2; 40 cycles 94°C× 35 seconds/58°C× 40 seconds/72°C 40 seconds | 110 bp/97 bp |

| N-myc-r | TCGTGAAAGTGGTTACAGCC | ||

| gli1-f | GCGAGAAGCCACACAAGTGC | 1.0 mM MgCl2; 10% DMSO; 40 cycles 94°C× 35 seconds/58°C× 40 seconds/72°C 40 seconds | 145 bp/126 bp |

| gli1-r | GGCATTGCTAAAGGCCTTGC | ||

| β2-microglobulin-f | TGTCCTTCAGCAAGGACTGG | 1.0 mM MgCl2; 40 cycles 94°C× 35 seconds/58°C× 40 seconds/72°C 40 seconds | 142 bp/127 bp |

| β2-microglobulin-r | TGATCACATGTCTCGATCCC |

Fragment sizes are indicated for target/competitor.

Western Blot Analysis

Murine GCPs and human MB cells were cultured for 1 hour before initiation of treatments with Shh and/or Igf-II of the respective species as described above. After two short rinses with Tris-buffered saline, cells were harvested after 15 minutes, 60 minutes, and 6 hours, respectively, by addition of lysis buffer. Lysis was performed on ice for 30 minutes in 500 μl of ice-cold lysis buffer containing 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 8), 120 mmol/L NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 1 mmol/L phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride (Sigma), 100 U/ml aprotinin (Calbiochem), and 0.1 mol/L NaF. Debris was removed by centrifugation for 20 minutes at 12,000 × g and at 4°C. Proteins were separated by electrophoresis on 4 to 12% Bis-Tris gels (NuPAGE, Invitrogen) and blotted onto nitrocellulose. To document equal loading of the gels, Ponceau staining of the membranes was performed. Blocking was performed with 10% nonfat dry milk (Bio-Rad, München, Germany) in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 20% horse serum for 2 hours at room temperature. The filters were then incubated with polyclonal antibodies against Akt, glycogen synthase kinase-3β (Gsk-3β), and phospho(Ser473)-Akt and phospho(Ser9)-Gsk-3β (New England Biolabs) following the instructions of the manufacturer. Binding of the primary antibody was detected by a secondary antibody labeled with horseradish peroxidase (Amersham). The filters were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagents (Amersham).

Results

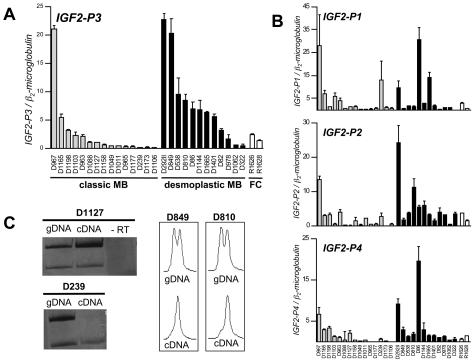

IGF2 mRNA Is Expressed in CMB and DMB with a Specific Profile of Promoter Usage

The analysis of 15 CMB and 12 DMB for IGF2 mRNA revealed that both subgroups of MB expressed IGF2. Promoter P3 contributed strongly to the total IGF2 transcript in both subgroups (amount of competitor required for optimal titration, 50 pg). IGF2 mRNA transcription from the other three promoters was much lower (amounts of competitor required for optimal titration: 100 fg for P1 and P4 and 5 fg for P2). Comparison of the promoter-specific transcription profiles between the classic and the desmoplastic subgroup revealed that promoter-specific transcription from P3 is significantly higher in DMB (t-test, P = 0.041), whereas no significant difference between CMB and DMB could be found in the levels of IGF2 P1-, P2-, and P4-dependent transcripts (Figure 1). Total IGF2 expression was calculated as the sum of the four transcripts, which, because of the predominant contribution of IGF2-P3, resulted in the same significant difference determined by t-test (P = 0.041). The MB cell lines analyzed displayed only minimal endogenous expression levels of IGF2 mRNA, which were mainly derived from promoter P3-dependent transcription.

Figure 1.

IGF2-P3 (A) and IGF2-P1, IGF2-P2, and IGF2-P4 (B) mRNA expression in the classic and desmoplastic subgroups and two fetal cerebellar control tissues (R1626 and R1628) (referred to β2-microglobulin as housekeeping gene). Optimal titration in the competitive RT-PCR assays was found for the following amounts of competitor added to RT: 100 fg of competitor for IGF2-P1 and IGF2-P4, 5 fg for IGF2-P2, and 50 pg for IGF2-P3. Promoter P3-specific transcription was significantly higher in DMB compared to CMB (t-test, P = 0.041). Error bars show the SEM. The order of the samples is the same in A and B. C: Imprinting analysis of human MB. In the analysis of the ApaI polymorphism, D1127 displayed biallelic expression (LOI) of IGF2, the PCR without previous RT (−RT) excluded contamination with genomic DNA. D239 showed monoallelic expression (MOI) of the IGF2 gene. In the analysis of the transcribed 3′ dinucleotide repeat in exon 9 of the IGF2 gene MOI was found in D849 and D810 (electropherograms according to Albrecht et al24).

Loss of Imprinting (LOI) of IGF2 Occurs in CMB and DMB but Is Not Associated with IGF2 Overexpression

Of the 29 samples included in the analysis of imprinting, 9 of 19 CMB and 4 of 10 DMB were informative for the transcribed ApaI RFLP. One CMB and two DMBs were informative for the 3′ fragment of the transcribed dinucleotide polymorphism in exon 9, another CMB was found to be informative for the 5′ fragment of the latter polymorphism. Three of eleven informative CMBs and one of the six informative DMBs displayed biallelic IGF2 transcription referred to as LOI. LOI appeared not to be preferentially associated with samples displaying particularly high levels of IGF2 mRNA (Figure 1 and Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of the IGF2 Imprinting Study in 19 Classic and 10 Desmoplastic MB

| Histology | Informativity

|

Imprint | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apal | DR 3′ | DR 5′ | |||

| D239 | Classic | Yes | n.d. | n.d. | MOI |

| D1011 | Classic | Yes | n.d. | n.d. | LOI |

| D1075 | Classic | Yes | n.d. | n.d. | MOI |

| D1173 | Classic | Yes | n.d. | n.d. | MOI |

| D1088 | Classic | Yes | n.d. | n.d. | LOI |

| D1106 | Classic | No | No | No | — |

| D1198* | Classic | Yes | n.d. | n.d. | MOI |

| D1177 | Classic | No | Yes | n.d. | MOI |

| D1103 | Classic | No | No | No | — |

| D965* | Classic | No | No | No | — |

| D967* | Classic | No | No | No | — |

| D1127 | Classic | Yes | n.d. | n.d. | LOI |

| D1076* | Classic | No | No | No | — |

| D1158 | Classic | Yes | n.d. | n.d. | MOI |

| D963* | Classic | No | n.d. | Yes | MOI |

| D1049 | Classic | No | No | No | — |

| D2010* | Classic | No | No | No | — |

| D1165 | Classic | No | No | No | — |

| D1106 | Classic | Yes | n.d. | n.d. | MOI |

| D322 | Desmoplastic | No | No | No | — |

| D538 | Desmoplastic | No | No | No | — |

| D849 | Desmoplastic | No | Yes | n.d. | MOI |

| D1062* | Desmoplastic | Yes | n.d. | n.d. | MOI |

| D978 | Desmoplastic | No | No | No | — |

| D810* | Desmoplastic | No | Yes | n.d. | MOI |

| D1665* | Desmoplastic | Yes | n.d. | n.d. | MOI |

| D1401* | Desmoplastic | Yes | n.d. | n.d. | LOI |

| D86 | Desmoplastic | Yes | n.d. | n.d. | MOI |

| D1144 | Desmoplastic | No | No | No | — |

DR, dinucleotide repeat; LOI, loss of imprinting; MOI, maintenance of imprinting.

, In these cases informativity was determined with tumor DNA because of lack of constitutional blood DNA.

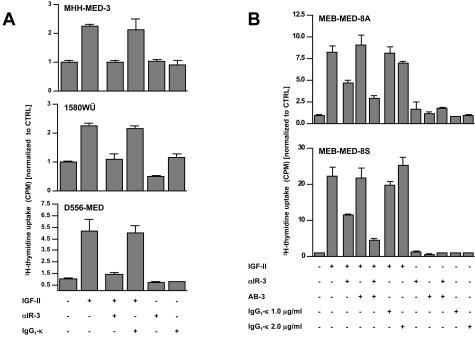

IGF-II but Not Shh Induces Proliferation in Human MB Cells and Signals through the IGF-IR and Insulin Receptors

Nine human MB cell lines were treated with recombinant human Shh, recombinant human IGF-II, and a combination of both factors. None of the cell lines, neither Daoy (derived from a DMB), nor any of the CMB derived cell lines showed a significant response to the Shh stimulus in terms of proliferation (data not shown). In contrast, addition of IGF-II resulted in clearly enhanced proliferative activity in six of nine cell lines (Figure 2, Table 3). In three cell lines (1580WÜ, MHH-MED-3, D556MED), addition of an IGF-IR antibody (α-IR-3) resulted in a complete abrogation of the proliferative effect of IGF-II. In two cell lines (MEB-MED-8A, MEB-MED-8S), α-IR-3 lead to a partial reversal of IGF-II-induced proliferation. To identify other receptors involved in the transmission of the IGF-II signal in the latter cells, we co-incubated them with the insulin receptor (IR) antibody AB-3. Blockage of the IR α-subunit alone did not show any effect in IGF-II-stimulated MEB-MED-8A and MEB-MED-8S cells, however, co-incubation of these cells with α-IR-3 and AB-3 lead to a significant further decrease in proliferative activity. Eventually, incubation of unstimulated 1580WÜ and MEB-MED-8S cells with α-IR-3 or AB-3, respectively, resulted in a reduction of their proliferative activity. The proliferative response of all cells examined was not significantly affected through incubation with a control antibody of appropriate isotype (IgG1-κ). Although IGF-II induced an increase of proliferative activity in D425MED and MHH-MED-1 cells (1.82- and 1.33-fold, respectively) both receptor antibodies did not show any inhibitory effect. Daoy and D283MED cells did not respond to IGF-II in terms of proliferation (Table 3).

Figure 2.

A: Results of the 3H-thymidine uptake assay in three human MB cell lines. IGF-II-induced proliferation could be entirely blocked by the addition of the IGF-IR antibody α-IR3 in 1580WÜ, D556MED, and MHH-MED-3 cells. B: Results of the experiment co-incubating α-IR3 and the insulin receptor antibody AB-3 in MEB-MED-8A and MEB-MED-8S.

Table 3.

Further Results of 3H-Thymidine Uptake Assays in Human MB Cell Lines

| Daoy | D425MED | D283MED | MHH-MED-1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTRL | 1.00 (± 0.05) | 1.00 (± 0.04) | 1.00 (± 0.15) | 1.00 (± 0.04) |

| IGF-II | 0.75 (± 0.06) | 1.82 (± 0.10) | 0.94 (± 0.13) | 1.33 (± 0.06) |

| IGF-II+ αIR3 | 0.95 (± 0.07) | 1.86 (± 0.20) | 1.10 (± 0.07) | 1.63 (± 0.12) |

| IGF-II+ IgG1-κ | 0.71 (± 0.05) | 1.76 (± 0.07) | 1.18 (± 0.06) | 1.27 (± 0.11) |

| αIR3 | 0.96 (± 0.06) | 1.09 (± 0.13) | 0.56 (± 0.02) | 1.54 (± 0.24) |

| IgG1-κ | 0.96 (± 0.06) | 1.01 (± 0.05) | 1.13 (± 0.19) | 0.90 (± 0.02) |

Counts per minute were referred to the basal proliferative activity of the cells grown without addition of any factor (CTRL). The standard error of the mean is indicated in parentheses.

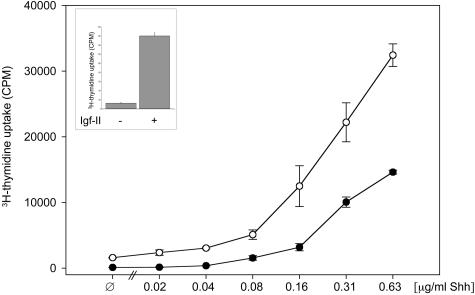

Igf-II and Shh Induce a Synergistic Proliferative Response of Murine GCPs

As it has been shown previously, incubation of GCPs derived from P8 murine cerebella with recombinant murine Shh resulted in enhanced cellular proliferation.26 Incubation of GCPs with recombinant murine Igf-II alone lead to a more than 10-fold induction of proliferation compared to the untreated control. Stimulation of GCPs with increasing concentrations of Shh and constant amounts of Igf-II resulted in an increasing difference in 3H-thymidine uptake of cells stimulated solely with Shh and those exposed to both, Shh and Igf-II. At its maximum, the ratio 3H-thymidine uptake (Shh + Igf-II-treated GCPs)/3H-thymidine uptake (Shh-treated GCPs) was 2.2 (Figure 3). Based on a report on a role of PI3K in Hedgehog signaling30 we performed co-incubations of GCPs treated with Shh with increasing amounts of the PI3K inhibitor LY294002. Inhibition of PI3K resulted in a significant dose-dependent decrease of cellular proliferative activity: Shh-induced proliferation was reduced to 3% (15 μmol/L LY294002), 12% (10 μmol/L LY294002), and 14% (5 μmol/L LY294002), which could partially be reversed by addition of Igf-II. Control experiments excluded cytotoxic effects of dimethyl sulfoxide (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Results of 3H-thymidine uptake assay in GCPs prepared on postnatal day 8. Co-stimulation of GCPs with Shh and Igf-II results in an enhanced proliferative activity (up to 2.2-fold) compared to stimulation with Shh alone. Cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of Shh and a constant amount of Igf-II (200 ng/ml). •, Shh; ○, Igf-II + Shh. Inset: Proliferative effect of stimulation with Igf-II (200 ng/ml) alone compared to the untreated control.

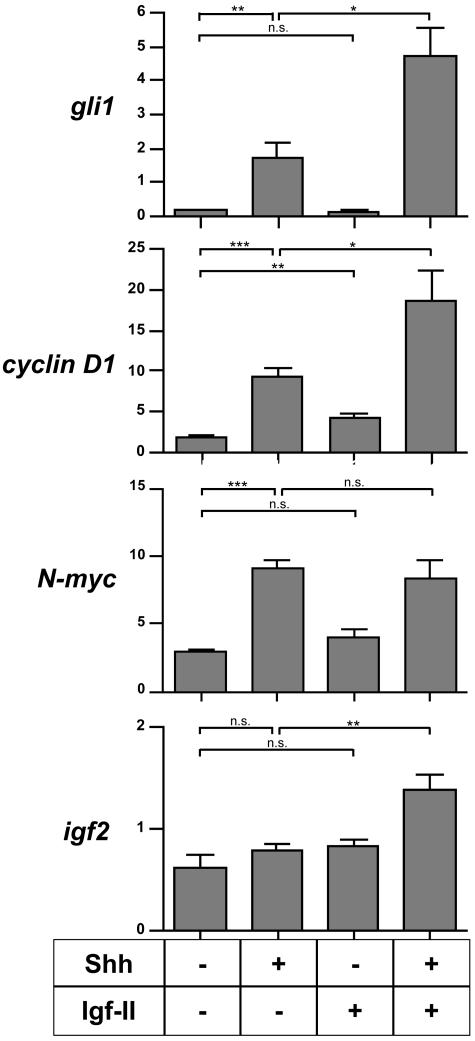

Igf-II and Shh Act Synergistically to Induce gli1 and cyclin D1 mRNA Transcription

We wanted to know if, as a transcriptional correlate of the synergism found in terms of proliferation, Igf-II increases Shh-induced mRNA levels of the known Hedgehog target genes gli1, cyclin D1, and N-myc. mRNA expression of these genes and igf2 was analyzed after 7 hours and 18 hours of treatment. At both times a significant transcriptional induction of gli1, cyclin D1, and N-myc by Shh could be confirmed. Igf-II was found to significantly induce cyclin D1 expression whereas gli1 and N-myc mRNA levels were not affected. Furthermore, Shh-induced expression of gli1 and cyclin D1 mRNA could be shown to be further increased through co-stimulation of the cells with Igf-II after 7 hours and 18 hours. Finally, our data show that Shh is not able to induce igf2 expression on its own, but that co-stimulation of GCPs with Shh and Igf-II significantly induces igf2 mRNA expression in GCPs (Figure 4, and data not shown).

Figure 4.

Results of the competitive RT-PCR assay in GCPs for igf2 and the Shh target genes gli1, N-myc, and cyclin-D1 after 7 hours of culture. gli1 and cyclin D1 transcription is synergistically induced by co-stimulation of GCPs with Shh and Igf-II. t-tests were performed for statistical analysis: n.s., not significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005; ***, P < 0.001.

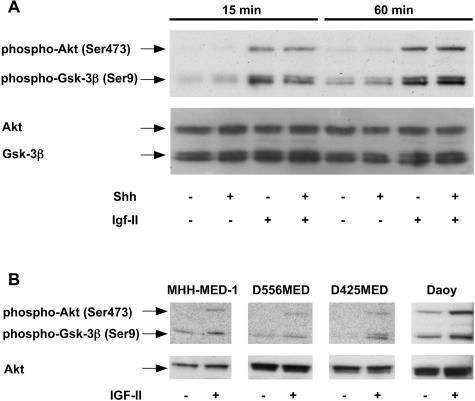

Igf-II Induces Phosphorylation of PI3K Pathway Members Akt and Gsk-3β in GCPs and Human MB Cells

In view of the result that PI3K inhibition aborts Shh-induced proliferation in GCPs we wanted to know if the synergistic effect of Shh and Igf-II might be mirrored in terms of a synergistic activation of the PI3K/Akt/Gsk-3β pathway or if PI3K pathway activity rather represents a necessary precondition for Hedgehog signaling in GCPs. Western blotting of protein lysates from GCPs showed a significant induction of phosphorylation of Akt protein at serine 473 and its downstream target Gsk-3β at serine 9 on the treatments with Igf-II, whereas no increase in the amount of phosphorylated protein could be observed in samples incubated/co-incubated with Shh. This activation of Akt and Gsk-3β was detectable as early as 15 minutes after exposure to Igf-II and it was still present after 60 minutes and 6 hours (Figure 5, and data not shown). In human MB cells, Western blotting of protein lysates prepared from IGF-II-treated human MB cells showed a significant induction of phosphorylation of Akt protein and Gsk-3β (Figure 5). Daoy cells, which did not show an increase in proliferation on treatment with IGF-II, displayed a high basal phosphorylation of the PI3K downstream targets Akt and Gsk-3β.

Figure 5.

A: Western Blot analysis of Akt, Gsk-3β, phospho-Akt(Ser473), and phospho-Gsk-3β(Ser9) in GCPs treated with different combinations of Shh and Igf-II. B: Western Blot analysis of Akt, phospho-Akt(Ser473), and phospho-Gsk-3β(Ser9) in human MB cell lines treated with IGF-II for 60 minutes.

Discussion

In the present study, we show that IGF-II is a potent mitogen for human MB cells. We also document that Igf-II positively modulates Shh-stimulated proliferation of cerebellar GCPs, which are believed to represent cells of origin of at least one subgroup of MBs, the desmoplastic variant. In these tumors we found IGF2 mRNA levels that were significantly higher than in classic MBs. IGF2 promoter P3 could be shown to be responsible for this transcriptional difference.

Although most DMBs occur as sporadic cases, it also represents the variant seen in nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome families. In contrast to the high incidence of basal cell carcinomas in these patients, less than 5% develop MBs.31 This implies that Shh-Ptch signaling alone is not sufficient for MB induction and that either the genetic background or the influence of other growth-promoting signaling pathways may be required for MB development. Based on the study of Hahn and colleagues13 who focused their search for such a cooperating signal on the igf2 gene, especially in ptc+/− rhabdomyosarcoma, we performed a detailed analysis of this gene and its functional relevance in human MB and in murine GCPs. Our study of IGF2 mRNA expression in MB confirmed the data of Pomeroy and colleagues14 because we found IGF2 expression significantly augmented in DMB compared to CMB. In addition to that, we were able to show that the imprinted promoter P3 is the major mediator of this effect. This prompted us to postulate that LOI of the IGF2 gene, which has been observed in various other embryonal tumors, might be responsible for increased IGF2 expression in DMB.32 In our panel of MBs we could not detect a significant difference concerning LOI of IGF2 between CMB and DMB. LOI occurred in both histological subtypes at frequencies that were lower (3 of 11 informative CMBs and 1 of 6 informative DMBs) than what has been observed previously in a smaller panel of tumors.24 Therefore, it is unlikely that LOI is the major mechanism responsible for the difference of IGF2 transcript levels.

Having shown that the IGF2 expression status correlated with a distinct subtype of MB (DMB), which is known to show activation of the Shh-Patched pathway, we focused on the functional role of IGF-II. Treatments of human MB cell lines with recombinant human Shh and IGF-II revealed that MB cells do not respond to Shh in vitro in terms of proliferation. This may be because of the fact that all cell lines apart from one (Daoy) are derived from classic MBs that usually do not show an activation of this pathway.8,33,34 Daoy cells, derived from a DMB, show an unusually low amount of PTCH mRNA,8,19 which may explain the lacking responsiveness to Shh. However, for IGF-II, we detected a significant proliferative effect in six of nine MB cell lines. Addressing the question which receptors are essential in the transmission of the IGF-II signal in MB cells, our data point to the possibility that a heterogeneous population of receptors is involved in the realization of the cellular answer triggered by IGF-II. In three cell lines (1580WÜ, D556MED, and MHH-MED-3) IGF-II-induced proliferation appeared to be entirely mediated through the IGF-IR. In contrast, the receptors involved in IGF-II signaling in MEB-MED-8S and MEB-MED-8A appeared to differ in structure, because the IGF-IR antibody α-IR-3 alone reduced the proliferative activity to a level of ∼50% whereas co-incubation of the cells with α-IR-3 and the IR antibody AB-3 results in a further decrease of proliferation. This points to the involvement of receptors that are constituted from different subunits, ie, hybrid receptors that, maybe because of steric interactions of the antibodies with the receptor, are most efficiently blocked when both antibodies are present. Interestingly, all cell lines examined showed exclusive expression of the shorter IR isoform A, which has been reported to bind IGF-II with a significantly higher affinity than isoform B.35 Heteromerization of IR isoform A hemi-receptors lacking exon 11 with IGF-IR subunits might contribute to the complex setting found in the transmission of the IGF-II signal in MB. The picture is getting even more complex regarding the observed inhibition of proliferative activity in unstimulated 1580WÜ and MEB-MED-8S by α-IR-3 and AB-3, respectively, which points to an autocrine loop via IGF-receptors (Figure 2, and data not shown). Considering the moderate expression of IGF2 transcripts in these cells it is of particular interest that they could be shown to express significant levels of IGF1 mRNA (W. Hartmann and T. Pietsch, unpublished). In view of the ongoing development of selective inhibitors of the IGF-IR kinase as anti-tumor drugs, the heterogeneity of IGF receptors represents a particular challenge.

On the other hand, we also identified two cell lines, which lacked a response to IGF-II in terms of proliferation (Daoy, D283MED) and two cell lines (D425MED, MHH-MED-1) in which both receptor antibodies did not show any inhibitory effect (Table 3). Because these cells have been derived from different histopathological subtypes of MB, an association between histomorphological characteristics of the original tumors and responsiveness to IGF-II or the inhibitory antibodies appears not to be likely. In Daoy cells, it has previously been shown that the IGF-IR is continuously activated independently of stimulation with IGF-I.36 Similar downstream activating events may be present in the cell lines D425MED, D283MED, and MHH-MED-1. In fact, we recently could show MHH-MED-1 to carry an inactivating mutation in the PTEN gene (W. Hartmann and T. Pietsch, unpublished).

With respect to the cellular origin of MB from neural cerebellar progenitors it was of interest to study the effect of Igf-II on cerebellar neural precursors from which MBs are believed to develop. Activation of Shh-Patched signaling is essential for the proliferation of these cells. In the developing cerebellum, Shh can exclusively be detected in Purkinje cells whereas igf2 transcription has predominantly been shown in the leptomeninges, choroid plexus, and blood vessels.37–40 Although incubation of GCPs with Igf-II alone already resulted in a significant increase in proliferative activity, treatment with both, Shh and Igf-II, revealed a synergistic effect of these factors on GCP proliferation (Figure 3). Based on the data presented by Kanda and colleagues,30 who reported induction of PI3K activity by Shh in capillary morphogenesis, we wondered if Shh signaling might also involve the PI3K pathway in GCP proliferation. Treatments of Shh-stimulated GCPs with LY294002 resulted in a dose-dependent reduction of proliferative activity, which could partially be restored through addition of Igf-II. This suggests that either PI3K is directly involved in the transmission of the Hedgehog signal or that it represents an essential precondition of Hedgehog signaling.

To find a transcriptional correlate of the synergistic effect of Shh and Igf-II on cellular proliferation, we analyzed the mRNA expression of known Shh-responsive genes. As expected the known targets were significantly induced by Shh on the transcriptional level, furthermore, gli1 and cyclin D1 were synergistically regulated by Shh and Igf-II. Gli1 acts as a transcription factor and is consistently induced in cells that receive a Hedgehog signal, and it has been shown to play an essential role for signal transduction in precursors and in tumorigenesis. Overexpression of GLI1 has been observed in different tumors, including DMB.33,41,42 D-type cyclins act as growth factor sensors and their activity is essential for the progression through the G1 phase of the cell cycle.43 Another interesting result of the mRNA analysis in stimulated GCPs was that igf2 mRNA levels did not increase on stimulation with Shh alone, whereas co-incubation of Shh and Igf-II lead to a significant induction of igf2 mRNA transcription. Thus, the hypothesis put forward by Hahn and colleagues,13 who showed elevated igf2 expression in nontumor (embryonic) tissue deficient in ptc, and therefore claimed that igf2 may be a target of Shh, must be modified for the in vitro situation of cultured GCPs: Shh-triggered induction of igf2 mRNA expression appears to be dependent on co-activity of other signaling pathways and Igf-II apparently can act as such a co-stimulator. This fits well with our observations on the synergistic regulation of gli1 and cyclin D1 transcription by Shh and Igf-II.

Having found that IGF-II preferentially signals via the IGF-IR in human MB cells and that Hedgehog-induced GCP proliferation can be reversed by inhibition of the PI3K pathway, we reasoned if the IGF and the Hedgehog signals might converge at the protein level involving phosphorylation of central signaling pathway compounds as Akt or Gsk-3β. We observed that, associated with its proproliferative effect, Igf-II induces phosphorylation of Akt and Gsk-3β in GCPs and MB cells whereas Shh does not influence the amount of phosphorylated protein, which excludes a central role of the PI3K pathway as a downstream element in Hedgehog signaling in GCPs. Our finding of phosphorylation events affecting signaling pathway elements downstream of the IGF-IR in MB is in good agreement with previous observations of Wang et al,36 and Del Valle and colleagues44 who found a phosphorylated IGF-IR in 59% of human MB samples. Concerning Daoy cells, which did not show enhanced proliferation on IGF-II stimulation, our results corresponded to the data published by Chin and colleagues45 and Wang et al.36 As mentioned above, lacking induction of proliferation in these cells on stimulation with IGF-II may in part be due to a continuous autophosphorylation of the IGF-IR in Daoy, which has been described before and which might be the reason for high levels of basal phospho-Akt and phospho-Gsk-3β levels seen in our study. However, as reported by Patti and colleagues,46 other pathways downstream of the IGF-IR as the MAPK pathway may also contribute to the growth-promoting effects of IGF-II.

Although our data provide a consistent transcriptional correlate of the interplay of Igf-II and Shh in terms of GCP proliferation, there is another scenario that might be of importance for the realization of the synergism we described: Our data show that in both, MB cells and GCPs, activation of IGF receptors by IGF-II leads to phosphorylation of Akt and its downstream target Gsk-3β. One essential function of the latter is to tag multiple substrates for degradation. Among these, Cyclin D1 and N-myc are associated with GCP proliferation and they have been shown to be transcriptionally activated by Shh-Patched signaling.28,29,47,48 So, additionally to its transcriptional co-activation of gli1 and cyclin D1, Igf-II might exert its role in GCP proliferation and tumorigenesis by providing mechanisms that complement Shh-driven transcriptional changes in terms of protein stabilization.

Our findings provide evidence that IGF-II signaling plays an important role in human MB. DMBs show increased IGF2 transcription levels, indicating an autocrine growth mechanism, and most MB cell lines respond to IGF-II. In GCPs, we demonstrate that Igf-II enhances the proliferative effect of Shh and that this synergism is mirrored in synergistically increased transcription of gli1 and cyclin D1. In MB cells and in GCPs, Igf-II leads to the activation of the PI3K/Akt/Gsk-3β pathway, which could be shown to go along with an enhanced effect of Shh. Further studies will be required to completely understand the molecular mechanisms involved in the synergistic activity of Igf-II and Shh.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Greg Riggins and Dr. Darell Bigner for kindly providing D425MED and D556MED cells and U. Klatt for photographic work.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Torsten Pietsch, Department of Neuropathology, University of Bonn Medical Center, Sigmund-Freud-St. 25, D-53105 Bonn, Germany. E-mail: t.pietsch@uni-bonn.de.

Supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant SFB 400) and the BONFOR program of the Medical Faculty, University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany.

Current address of O.D.W.: German Cancer Research Center, D-69120 Heidelberg, Germany.

References

- Stevens MC, Cameron AH, Muir KR, Parkes SE, Reid H, Whitwell H. Descriptive epidemiology of primary central nervous system tumours in children: a population-based study. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 1991;3:323–329. doi: 10.1016/s0936-6555(05)80587-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giangasparo F, Bigner SH, Kleihues P, Pietsch T, Trojanowski JQ. Pathology and genetics of tumors of the nervous system. Kleihues P, Cavenee WK, editors. Lyon: IARC Press; World Health Organization Classification of Tumors. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Bühren J, Christoph AH, Buslei R, Albrecht S, Wiestler OD, Pietsch T. Expression of the neurotrophin receptor p75NTR in medulloblastomas is correlated with distinct histological and clinical features: evidence for a medulloblastoma subtype derived from the external granule cell layer. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59:229–240. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn H, Wicking C, Zaphiropoulous PG, Gailani MR, Shanley S, Chidambaram A, Vorechovsky I, Holmberg E, Unden AB, Gillies S, Negus K, Smyth I, Pressman C, Leffell DJ, Gerrard B, Goldstein AM, Dean M, Toftgard R, Chenevix-Trench G, Wainwright B, Bale AE. Mutations of the human homolog of Drosophila patched in the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Cell. 1996;85:841–851. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81268-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffel C, Jenkins RB, Frederick L, Hebrink D, Alderete B, Fults DW, James CD. Sporadic medulloblastomas contain PTCH mutations. Cancer Res. 1997;57:842–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietsch T, Scharmann T, Fonatsch C, Schmidt D, Öckler R, Freihoff D, Albrecht S, Wiestler OD, Zeltzer P, Riehm H. Characterization of five new cell lines derived from human primitive neuroectodermal tumors of the central nervous system. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3278–3287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolter M, Reifenberger J, Sommer C, Ruzicka T, Reifenberger G. Mutations in the human homologue of the Drosophila segment polarity gene patched (PTCH) in sporadic basal cell carcinomas of the skin and primitive neuroectodermal tumors of the central nervous system. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2581–2585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietsch T, Waha A, Koch A, Kraus J, Albrecht S, Tonn J, Sörensen N, Berthold F, Henk B, Schmandt N, Wolf HK, von Deimling A, Wainwright B, Chenevix-Trench G, Wiestler OD, Wicking C. Medulloblastomas of the desmoplastic variant carry mutations of the human homologue of Drosophila patched. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2085–2088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz i Altaba A, Sanchez P, Dahmane N. Gli and Hedgehog in cancer: tumours, embryos and stem cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:361–372. doi: 10.1038/nrc796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich LV, Scott MP. Hedgehog and patched in neural development and disease. Neuron. 1998;21:1243–1257. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80645-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich LV, Milenkovic L, Higgins KM, Scott MP. Altered neural cell fates and medulloblastoma in mouse patched mutants. Science. 1997;277:1109–1113. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5329.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn H, Wojnowski L, Zimmer AM, Hall J, Miller G, Zimmer A. Rhabdomyosarcomas and radiation hypersensitivity in a mouse model of Gorlin syndrome. Nat Med. 1998;4:619–622. doi: 10.1038/nm0598-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn H, Wojnowski L, Specht K, Kappler R, Calzada-Wack J, Potter D, Zimmer A, Muller U, Samson E, Quintanilla-Martinez L. Patched target Igf2 is indispensable for the formation of medulloblastoma and rhabdomyosarcoma. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28341–28344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000352200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomeroy SL, Tamayo P, Gaasenbeek M, Sturla LM, Angelo M, McLaughlin ME, Kim JY, Goumnerova LC, Black PM, Lau C, Allen JC, Zagzag D, Olson JM, Curran T, Wetmore C, Biegel JA, Poggio T, Mukherjee S, Rifkin R, Califano A, Stolovitzky G, Louis DN, Mesirov JP, Lander ES, Golub TR. Prediction of central nervous system embryonal tumour outcome based on gene expression. Nature. 2002;415:436–442. doi: 10.1038/415436a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toretsky JA, Helman LJ. Involvement of IGF-II in human cancer. J Endocrinol. 1996;149:367–372. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1490367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk MA, van Schaik FM, Bootsma HJ, Holthuizen P, Sussenbach JS. Initial characterization of the four promoters of the human insulin-like growth factor II gene. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1991;81:81–94. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(91)90207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu TH, Hoffman AR. Promoter-specific imprinting of the human insulin-like growth factor-II gene. Nature. 1994;371:714–717. doi: 10.1038/371714a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman HS, Burger PC, Bigner SH, Trojanowski JQ, Wikstrand CJ, Halperin EC, Bigner DD. Establishment and characterization of the human medulloblastoma cell line and transplantable xenograft D283 Med. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1985;44:592–605. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198511000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen PF, Jenkyn DJ, Papadimitriou JM. Establishment of a human medulloblastoma cell line and its heterotransplantation into nude mice. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1985;44:472–485. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198509000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He XM, Wikstrand CJ, Friedman HS, Bigner SH, Pleasure S, Trojanowski JQ, Bigner DD. Differentiation characteristics of newly established medulloblastoma cell lines (D384 Med, D425 Med, and D458 Med) and their transplantable xenografts. Lab Invest. 1991;64:833–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldosari N, Rasheed BK, McLendon RE, Friedman HS, Bigner DD, Bigner SH. Characterization of chromosome 17 abnormalities in medulloblastomas. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2000;99:345–351. doi: 10.1007/s004010051134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann W, Waha A, Koch A, Albrecht S, Gray SG, Ekström TJ, von Schweinitz D, Pietsch T. Promoter-specific transcription of the IGF2 gene: a novel rapid, non-radioactive and highly sensitive protocol for mRNA analysis. Virchows Arch. 2001;439:803–807. doi: 10.1007/s004280100509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waha A, Watzka M, Koch A, Pietsch T, Przkora R, Peters N, Wiestler OD, von Deimling A. A rapid and sensitive protocol for competitive reverse transcriptase (cRT) PCR analysis of cellular genes. Brain Pathol. 1998;8:13–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1998.tb00129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht S, Waha A, Koch A, Kraus JA, Goodyer CG, Pietsch T. Variable imprinting of H19 and IGF2 in fetal cerebellum and medulloblastoma. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1996;55:1270–1276. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199612000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertz KD, Weisheit G, Schilling K, Luers GH. Electroporation of primary neural cultures: a simple method for directed gene transfer in vitro. Histochem Cell Biol. 2002;118:501–506. doi: 10.1007/s00418-002-0473-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler-Reya RJ, Scott MP. Control of neuronal precursor proliferation in the cerebellum by Sonic hedgehog. Neuron. 1999;22:103–114. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80682-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney AM, Cole MD, Rowitch DH. Nmyc upregulation by Sonic hedgehog signaling promotes proliferation in developing cerebellar granule neuron precursors. Development. 2003;130:15–28. doi: 10.1242/dev.00182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney AM, Rowitch DH. Sonic hedgehog promotes G(1) cyclin expression and sustained cell cycle progression in mammalian neuronal precursors. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:9055–9067. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.23.9055-9067.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver TG, Grasfeder LL, Carroll AL, Kaiser C, Gillingham CL, Lin SM, Wickramasinghe R, Scott MP, Wechsler-Reya RJ. Transcriptional profiling of the Sonic hedgehog response: a critical role for N-myc in proliferation of neuronal precursors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:7331–7336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0832317100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanda S, Mochizuki Y, Suematsu T, Miyata Y, Nomata K, Kanetake H. Sonic hedgehog induces capillary morphogenesis by endothelial cells through phosphoinositide 3-kinase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8244–8249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210635200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toftgard R. Hedgehog signalling in cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:1720–1731. doi: 10.1007/PL00000654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tycko B. Genomic imprinting: mechanism and role in human pathology. Am J Pathol. 1994;144:431–443. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reifenberger J, Wolter M, Weber RG, Megahed M, Ruzicka T, Lichter P, Reifenberger G. Missense mutations in SMOH in sporadic basal cell carcinomas of the skin and primitive neuroectodermal tumors of the central nervous system. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1798–1803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurawel RH, Allen C, Chiappa S, Cato W, Biegel J, Cogen P, de Sauvage F, Raffel C. Analysis of PTCH/SMO/SHH pathway genes in medulloblastoma. Genes Chromosom Cancer. 2000;27:44–51. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2264(200001)27:1<44::aid-gcc6>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasca F, Pandini G, Scalia P, Sciacca L, Mineo R, Costantino A, Goldfine ID, Belfiore A, Vigneri R. Insulin receptor isoform A, a newly recognized, high-affinity insulin-like growth factor II receptor in fetal and cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3278–3288. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JY, Del Valle L, Gordon J, Rubini M, Romano G, Croul S, Peruzzi F, Khalili K, Reiss K. Activation of the IGF-IR system contributes to malignant growth of human and mouse medulloblastomas. Oncogene. 2001;20:3857–3868. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondy CA, Werner H, Roberts CT, Jr, LeRoith D. Cellular pattern of insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) and type I IGF receptor gene expression in early organogenesis: comparison with IGF-II gene expression. Mol Endocrinol. 1990;4:1386–1398. doi: 10.1210/mend-4-9-1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetts SW, Rosen KM, Dikkes P, Villa-Komaroff L, Mozell RL. Expression and imprinting of the insulin-like growth factor II gene in neonatal mouse cerebellum. J Neurosci Res. 1997;50:958–966. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19971215)50:6<958::AID-JNR6>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlsson R, Hedborg F, Holmgren L, Walsh C, Ekström TJ. Overlapping patterns of IGF2 and H19 expression during human development: biallelic IGF2 expression correlates with a lack of H19 expression. Development. 1994;120:361–368. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.2.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Pablo F, de la Rosa EJ. The developing CNS: a scenario for the action of proinsulin, insulin and insulin-like growth factors. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:143–150. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93892-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz i Altaba A. Gli proteins and Hedgehog signaling: development and cancer. Trends Genet. 1999;15:418–425. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01840-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson M, Unden AB, Krause D, Malmqwist U, Raza K, Zaphiropoulos PG, Toftgard R. Induction of basal cell carcinomas and trichoepitheliomas in mice overexpressing GLI-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3438–3443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050467397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ. Cancer cell cycles. Science. 1996;274:1672–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Valle L, Enam S, Lassak A, Wang JY, Croul S, Khalili K, Reiss K. Insulin-like growth factor I receptor activity in human medulloblastomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1822–1830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin LS, Yung WK, Raffel C. Two primitive neuroectodermal tumor cell lines require an activated insulin-like growth factor I receptor for growth in vitro. Neurosurgery. 1996;39:1183–1190. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199612000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patti R, Reddy CD, Geoerger B, Grotzer MA, Raghunath M, Sutton LN, Phillips PC. Autocrine secreted insulin-like growth factor-I stimulates MAP kinase-dependent mitogenic effects in human primitive neuroectodermal tumor/medulloblastoma. Int J Oncol. 2000;16:577–584. doi: 10.3892/ijo.16.3.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl JA, Cheng M, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta regulates cyclin D1 proteolysis and subcellular localization. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3499–3511. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.22.3499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney AM, Widlund HR, Rowitch DH. Hedgehog and PI-3 kinase signaling converge on Nmyc1 to promote cell cycle progression in cerebellar neuronal precursors. Development. 2004;131:217–228. doi: 10.1242/dev.00891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]