Abstract

We have shown previously that the hypomineralization defects of the calvarium and vertebrae of tissue nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP)-deficient (Akp2−/−) hypophosphatasia mice are rescued by simultaneous deletion of the Enpp1 gene, which encodes nucleotide pyrophosphatase phosphodiesterase 1 (NPP1). Conversely, the hyperossification in the vertebral apophyses typical of Enpp1−/− mice is corrected in [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] double-knockout mice. Here we have examined the appendicular skeletons of Akp2−/−, Enpp1−/−, and [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] mice to ascertain the degree of rescue afforded at these skeletal sites. Alizarin red and Alcian blue whole mount analysis of the skeletons from wild-type, Akp2−/−, and [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] mice revealed that although calvarium and vertebrae of double-knockout mice were normalized with respect to mineral deposition, the femur and tibia were not. Using several different methodologies, we found reduced mineralization not only in Akp2−/− but also in Enpp1−/− and [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] femurs and tibias. Analysis of calvarial- and bone marrow-derived osteoblasts for mineralized nodule formation in vitro showed increased mineral deposition by Enpp1−/− calvarial osteoblasts but decreased mineral deposition by Enpp1−/− long bone marrow-derived osteoblasts in comparison to wild-type cells. Thus, the osteomalacia of Akp2−/− mice and the hypomineralized phenotype of the long bones of Enpp1−/− mice are not rescued by simultaneous deletion of TNAP and NPP1 functions.

Physiological biomineralization is a tightly controlled process that is initiated within osteoblast and chondrocyte-derived matrix vesicles (MVs). MVs are submicroscopic, extracellular, membrane-invested bodies containing calcium and inorganic phosphate (Pi). The first crystals of hydroxyapatite (HA) bone mineral are generated within MVs in growth plate cartilage,1 developing bone,2 and dentin.3 This initial phase of HA mineral deposition occurs within the protected microenvironment provided by the membrane of MVs,1 and is followed by a second phase of mineral propagation in which HA protrudes into the matrix surrounding individual MVs.3 Inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) antagonizes the ability of Pi to crystallize with calcium to form HA and thereby inhibits HA deposition.4–6 Therefore for normal mineralization to proceed, a balance is required between levels of Pi and PPi.

Several molecules are important in the regulation of Pi and PPi levels, including tissue nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP) and nucleotide pyrophosphatase phosphodiesterase 1 (NPP1). Deletion of the TNAP gene (Akp2) in mice results in a model of infantile hypophosphatasia,7,8 characterized by rickets, osteomalacia, spontaneous bone fractures, and increased PPi levels.9 TNAP is highly expressed on the outer surfaces of MVs,10,11 and there is considerable experimental evidence indicating that TNAP can stimulate mineral deposition in vitro by preparations of isolated MVs,12,13 or in slices of rachitic rat growth plate.14 In Akp2−/− mice, and also in human hypophosphatasia, the initial stages of biomineralization are normal, ie, MVs deposit calcium phosphate internally which is rapidly converted to crystalline HA.15,16 However, the propagation phase in which mineral bursts from MVs into the surrounding matrix is defective in the absence of TNAP, leading to an overall decrease in the amount of perivesicular mineral deposited.15,16 Thus, in bone, the hydrolytic activity of TNAP restricts the concentration of the mineralization inhibitor PPi while simultaneously contributing to the pool of Pi available for propagation of HA deposition.

In contrast, genetic ablation of a molecule that generates PPi, ie, NPP1 (previously termed PC-1, npps, and ttw) causes a hypermineralized phenotype of both soft tissues and certain sites in the skeleton. Mice lacking the NPP1 gene (Enpp1) show decreased levels of PPi, and exhibit abnormalities including ankylosing intervertebral and peripheral joint hyperostosis and articular cartilage calcification. Enpp1−/− mice also display arterial calcification and NPP1 deficiency has recently been linked to a syndrome of infantile arterial and periarticular calcification.17–19 Thus NPP1 serves as a physiological inhibitor of mineral deposition, at least in part, by generating PPi.

We have previously shown that the abnormal PPi levels and mineralization deficits of calvarium and spine associated with TNAP or NPP1 deficiencies are reversed and normalized in mice lacking both TNAP and NPP1, ie, [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] double-knockout mice.20 These studies have indicated that both TNAP and NPP1 are potential therapeutic targets for the treatment of mineralization disorders. Interestingly, the so-called tiptoe walking mice (ttw/ttw), due to a NPP1 truncation mutation, are nearly identical to Enpp1−/− mice, and have been documented to display trabecular bone loss in addition to spontaneous mineralization of soft tissue.17,21 In this article, we have performed a systematic study to fully document the extent of mineral deposition in bones of Enpp1−/− and [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] mice, to ascertain whether the Enpp1−/− mice also display trabecular bone loss and whether correction of mineralization abnormalities in the [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] mice extends to the entire skeleton.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

All routine chemicals were of an analytical grade from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), unless otherwise indicated.

Generation and Maintenance of Akp2−/−, Enpp1−/−, and [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] Mice

The generation and characterization of Akp2−/−, Enpp1−/−, and [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] mice have been reported previously.7,8,20,22 To determine genotypes, genomic DNA was isolated from tails and analyzed using polymerase chain reaction protocols as described.20

Whole Mount Skeletal Analysis

Whole mount skeletal preparations were prepared by removal of skin and viscera of mice followed by a 1-week immersion in 100% ethanol, followed by 100% acetone. Samples were then transferred to a 100% ethanol solution containing 0.01% alizarin red S, 0.015% Alcian blue 8GX, and 0.5% acetic acid for 3 weeks. Samples were destained with 1% (v/v) KOH/50% glycerol solution. Cleared samples were stored in 100% glycerol.

Microcomputerized Tomography (microCT)

The distribution and relative density of bone mineral was imaged and measured by microCT, performed by Enhanced Vision Systems Corp. (now GE Medical Systems) of London, Ontario, Canada. Specimens for microCT analysis consisted of sagitally-sectioned, 2.5% paraformaldehyde-fixed, upper tibias and attached femurs, dissected free of soft tissue. Volume cone-beam CT imaging was used to create 14-μm resolution volume data sets from wild-type (WT) (n = 7), Akp2−/− (n = 4), Enpp1−/− (n = 4) and [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] (n = 3) mice, all 10 days of age. The microCT images were analyzed for bone volume fraction, reported as percent of total bone volume, bone mineral density in mg/ml, mean trabecular bone thickness (Tb.Th) in mm, and trabecular number (Tb. N) per mm2 of bone surface.

Light Microscopy and Alizarin Red Calcium Stains

Nondecalcified upper tibial growth plates and subjacent metaphyseal and cortical bone were dissected from 10-day-old WT (n = 7), Akp2−/− (n = 4), Enpp1−/− (n = 4), and [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] (n = 3). Bones were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, buffered with cacodylate,1 and then embedded in Spurr epoxy resin. Standard light microscopy was performed on 1-μm-thick sections of the Spurr-embedded bones. Sections were also stained for calcium, using the alizarin red method,23 which specifically stains calcium red in 1-μm-thick bone sections without prior deplastization to remove the epoxy resin.

Fourier Transform-Infrared Imaging Spectroscopy (FT-IRIS)

FT-IRIS was performed on 1-μm-thick unstained Spurr-embedded sections from the same blocks as used for light microscopy and alizarin red staining. Sections were cut onto BaF2 infrared windows and a Bio-Rad (Cambridge, MA) FTS-60A step-scanning Stingray 6000 FTIR spectrometer with a UMA 300A FTIR microscope and a 64 × 64 MCT FPA detector was used to acquire spectra at 8 cm−1 resolution under N2 purge. Data were collected from 400 × 400 μm2 regions at 64 × 64 individual points of 7 μm diameter, resulting in 4096 individual spectra. Infrared vibrations of both the mineral and matrix phases were monitored simultaneously. The ratio of the area of the mineral phosphate V1, V3 absorbance from 900 to 1200 cm−1 to the area of the protein amide I absorbance from 1590 to 1720 cm−1 was calculated to obtain the relative amounts of mineral and protein present (mineral:matrix ratio). The ratio of the intensities of the phosphate contour at 1030 and 1020 cm−1 was calculated as an indicator of crystallinity. IR images were then created based on mineral:matrix ratio and crystallinity.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Ultrathin sections were taken from the sectioned surfaces of Spurr-embedded blocks of upper tibial growth plates and metaphysis used to produce 1-μm-thick sections for light microscopy and alizarin red staining. Transmission electron microscopy sections were stained with lead citrate and uranyl acetate as previously described.1 The sections were examined and photographed using a Zeiss EM10A electron microscope (Oberkochen, Germany).

Immunohistochemistry

WT mice, both day 10 and day 20, were euthanized and bone tissue was harvested. Bones were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/phosphate-buffered saline and processed and sectioned as previously described.24 Paraffin-embedded sections were dewaxed and rehydrated before antibody staining. Antibody staining was performed using a Histomouse-Max kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The monoclonal antibody to NPP125 was used at a 1:50 dilution. Negative controls were performed using either mouse IgG at the same dilution as the primary antibody, or with no primary antibody present.

Primary Osteoblast Isolation and Differentiation

Primary cultures of osteoblasts were isolated from calvaria of 3-day-old WT and Enpp1−/− mice by sequential collagenase digestion, as described.24 An enriched cell population of osteoblastic phenotype was plated at a density of approximately 4 × 104 cells/cm2 in osteogenic medium, ie, α-minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, ascorbic acid (50 μg/ml), and β-glycerophosphate (10 mmol/L). To isolate osteoblast-like cells from bone marrow, whole bone marrow was flushed from the long bones of 3-month-old WT and Enpp1−/− mice. The marrow suspension was dispersed to attain a homogenous cell suspension and was then centrifuged at 1100 rpm for 5 minutes. The cell pellet was resuspended in α-minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and was filtered through a 70-μm sieve. Cells were plated at a density of 4 × 106 cells/well in a six-well plate. After 5 days the nonadherent cell population was removed and cells were refed in osteogenic medium as for calvarial cells. For both systems the medium was completely replaced every third day. After 14 to 21 days of culture in osteogenic medium, the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/phosphate-buffered saline and alkaline phosphatase activity followed by von Kossa staining, performed as previously described.24 The nodules formed were quantified as previously described, using the point-counting method, and expressed as the percentage area mineralized.24

Western Blot Analysis and NPP1 and TNAP Activity Assays

Three-day-old WT mice (n = 6) were euthanized and calvaria were cut into two pieces, long bones (tibia and femur) were isolated from each leg resulting in two samples/tissue type/animal. All tissue was minced with a scalpel, sonicated, and mixed for 1 hour (at 4°C) in 0.5 mol/L Tris, pH 8.0, 1.6 mmol/L MgCl2, and 1% Triton X-100. NPP1 and alkaline phosphatase assays were performed as described in Vaingankar and colleagues.26 Western blot analysis for ANK, TNAP, and NPP1 was performed as described.27,28 Briefly, primary antibody diluted at a concentration of 3 μg/ml in SuperBlock containing 5% normal goat serum, was incubated with one membrane strip at room temperature for 2 hours. After washing, all membrane strips were incubated with peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulins (Cappel, West Chester, PA) in 5% normal goat serum-Tris-buffered saline/Tween 20. Immunoreaction was detected by the ECL-plus system (Amersham Bioscience, Piscataway, NJ).

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed by one-factor analyses of variance or two-factor analysis of variance when appropriate. After statistically significant effects in the analyses of variance, posthoc comparisons among means were conducted with Fisher’s LSD test. The level of significance was set at 0.05.

Results

Whole Mount Analysis of Mineral Deposition in WT, Akp2−/−, and [Akp2−/− ; Enpp1−/−] Mice

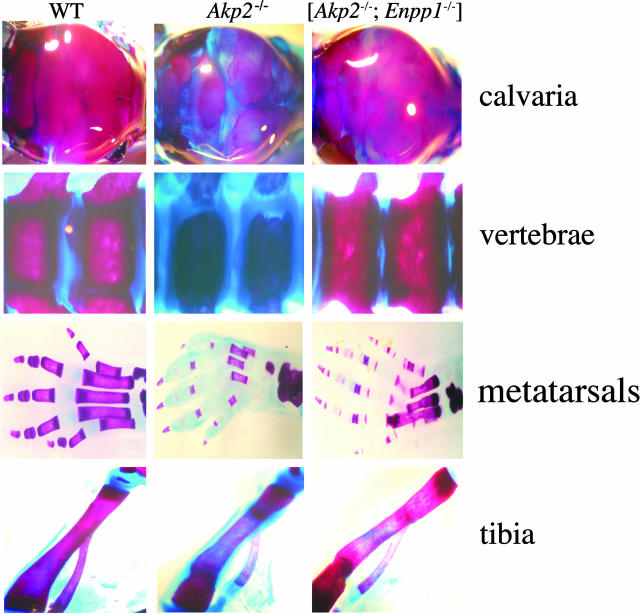

We have previously reported that the vertebral apophyses and calvaria from mice with null mutations in both the Akp2 and Enpp1 genes display a dramatic amelioration of the hypomineralized phenotype of mice deficient in Akp2 alone.20 In this study we have further analyzed the [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] skeletons to assess the effects of loss of NPP1 activity on the hypophosphatasia phenotype of Akp2−/− mice. A comparison of the amount of mineralized bone between WT, Akp2−/−, and [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] whole mount skeletal specimens, as measured by alizarin red and Alcian blue staining, revealed a differential rescue of the hypomineralized phenotype with respect to bone site in double-knockout mice (Figure 1). It is important to note that in these studies, Alcian blue is used at pH 5.5 and therefore stains unmineralized osteoid rather than cartilage.20 The calvarial bones and the vertebral apophyses of the [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] mice displayed a clearly normalized morphology (Figure 1). A partial correction is observed in the metatarsal bones, but not in the phalanges. Both the femur and tibia from these double-knockout mice do not appear to have rescue in comparison to either the vertebrae or calvaria, and display a residual abnormality in mineral deposition, with the degree of positive alizarin red staining not restored to WT levels in the double-knockout mice. These data suggest that the simultaneous ablation of the Akp2 and Enpp1 genes, while affecting a dramatic amelioration of mineralization deficits in certain bones, does not show significant rescue of mineralization abnormalities in the long bones.

Figure 1.

Whole mounted calvaria, spine, metatarsals, and tibias, stained for calcium with alizarin red and unmineralized osteoid with Alcian blue from WT, Akp2−/−, and [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] double-knockout mice. Although double deficiency of TNAP and NPP1 restored mineralization in the calvaria and spine, and to a lesser extent in the metatarsal bones of the feet, the phalangeal bones and the tibias of double-knockout mice still displayed moderate to severe hypomineralization in comparison to WT controls.

MicroCT and Alizarin Red Staining of Long Bones

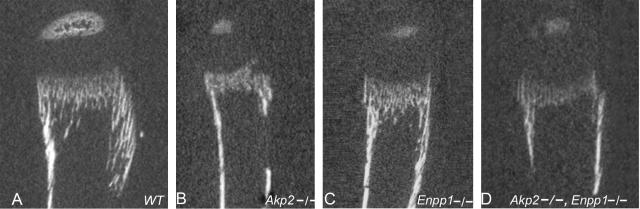

To further quantify the amount of mineral present, and the extent to which [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] long bones are normalized, we performed a detailed examination of these bones using microCT and high-resolution alizarin red stains. MicroCT analysis of the upper tibial growth plate, cortex, and metaphysis of WT, Akp2−/−, Enpp1−/−, and [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] tibias revealed that in fact Enpp1−/− tibias display a moderately to severely reduced mineral content in both the upper growth plate and subjacent bone (Figure 2). Given that Akp2−/− mice display severe hypomineralization, and that Enpp1−/− tibial growth plates are also under-mineralized it is not surprising that in [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] double-knockout tibias, mineral content was even more reduced in comparison to Enpp1−/− single knockout tibias (Figure 2, C versus D). In addition the epiphyses (secondary ossification centers) were less well developed in both Enpp1−/− and [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] deficiencies in comparison to WT (Figure 2). To quantify these findings, bone mineral density, bone volume fraction, and average bone trabecular thickness, were measured by microCT densitometry. Bone mineral density, bone volume fraction, and trabecular thickness were all moderately reduced in NPP1-deficient tibias in comparison to WT. In the [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] tibias there was an even more marked reduction in the bone mineral density, bone volume fraction, and trabecular thickness (Table 1).

Figure 2.

MicroCT images of upper tibias from WT (A), Akp2−/− (B), Enpp1−/− (C), and [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] (D) mice. Note: moderate deficiency of bone mineralization in NPP1 deficiency and moderate to severe mineralization in TNAP deficiency and TNAP/NPP1 double deficiency.

Table 1.

Micro-CT Comparison of Average Bone Mineral Density (BMD), Bone Volume Fraction (BVF), and Trabecular Thickness in Wild-Type versus TNAP, NPP1, and TNAP/NPP1-Deficient Upper Tibias

| Genotype | BMD (mg/cc) | BVF (%) | Trabecular thickness (mm) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 174 ± 14 | 46 ± 5 | 53 ± 8 | 7 |

| Akp−/− | 92 ± 8* | 27 ± 5* | 30 ± 3* | 4 |

| Enpp1−/− | 137 ± 11 | 40 ± 5 | 41 ± 1 | 4 |

| Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/− | 77 ± 19* | 18 ± 5* | 27 ± 3* | 3 |

Data presented as mean ± SE.

P < 0.05, WT versus knockout.

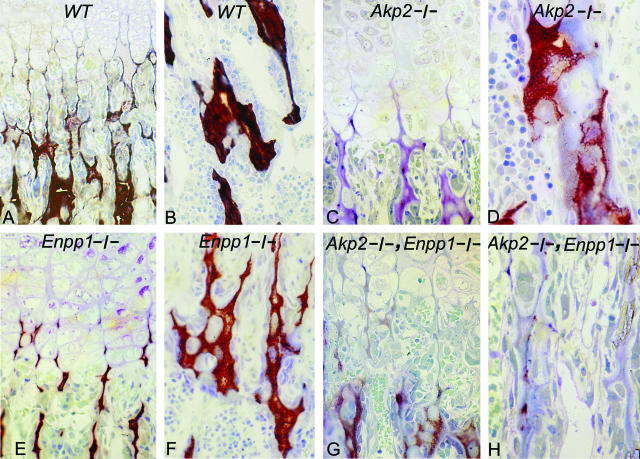

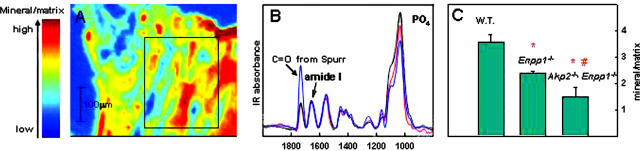

To further investigate the pattern of mineral deposition in these mice, we performed histological analysis using nondecalcified tibias from each respective genotype and used alizarin red staining to detect calcium (Figure 3). These data confirmed the microCT data, ie, showing a decrease of calcification in lower hypertrophic zones of growth plate as well as in metaphyseal bone trabeculae and cortical bone in Enpp1−/− mice (Figure 3). Mineral deposits in NPP1-deficient tibias were paler and less intensely red-brown stained suggesting a decreased concentration of CaPO4 in these animals. Also, there was an abnormal accumulation of uncalcified bone matrix (osteoid) at surfaces of the cortex and metaphyseal bone trabeculae in Enpp1−/− tibias that was more pronounced in [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−]-deficient mouse tibias (Figure 3). We confirmed our histological observations that Enpp1−/− and [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] tibia have less mineral than WT controls using FT-IRIS analysis, which also indicated reduced calcium phosphate mineral in NPP1-deficient tibias and markedly reduced mineral in the [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] double deficiency. No differences in crystallinity of the mineral phase were detected in WT versus Enpp1−/− and [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−]-deficient tibias (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Alizarin red staining for calcium in 1-μm-thick sections from Spurr-embedded tibial growth plates, cortex, and metaphyses of WT (A, B), Akp2−/− (C, D), Enpp1−/− (E, F), and [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] (G, H) upper tibias. Mineral was slightly to moderately reduced in growth plate and bone of Enpp1−/− tibias and moderately to severely reduced in Akp2−/− and [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] tibias. Alizarin red stain with toluidine blue counterstain. Original magnifications, ×595.

Figure 4.

A: An IR image based on the mineral/matrix ratio obtained in a Spur-embedded section from a Enpp1−/− mouse. Data were collected at 6.25-μm intervals from a trabecular bone region as outlined on the IR image (regions of marrow were excluded from the analysis). B: Typical baselined infrared spectra from the WT (black), Enpp1−/− (red), and Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/− (blue) are shown. The IR absorbances from the embedding media Spurr resin, the bone matrix protein (amide I), and mineral phosphate band are labeled. C: The mean mineral:matrix ratio was reduced in the Enpp1−/− compared to the WT, and even further reduced in the Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/− compared to both the WT and the Enpp1−/−. *, Significantly different (P < 0.05) compared to WT; #, significantly different compared to Enpp1−/−.

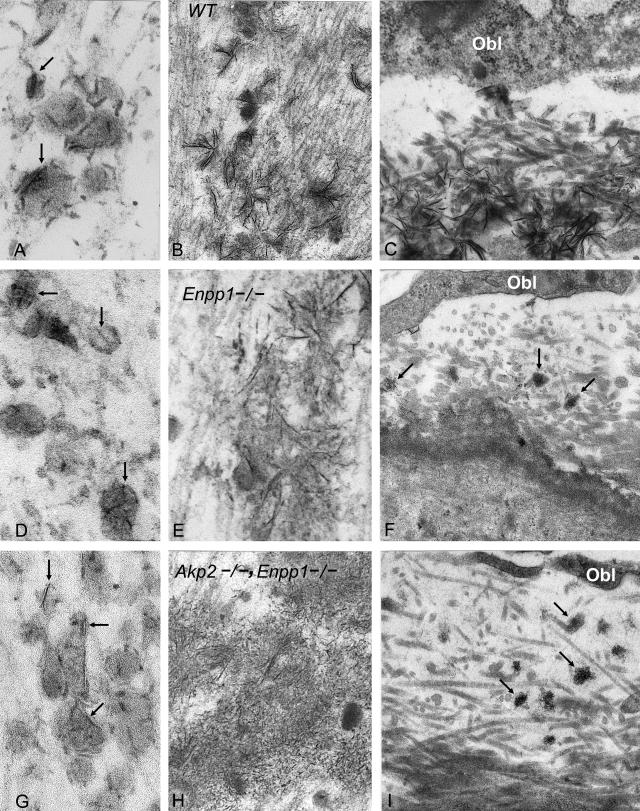

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Transmission electron microscopy showed a decrease in overall mineral density in Enpp1−/− growth plates and at surfaces of newly formed bone in the metaphysis. There was an apparent further decrease in overall mineral density in [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] double-knockout growth plates and bone (Figure 5; A to I). The fine structure of mineral was less needle-like and more granular in both Enpp1−/− knockout and [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] double-knockout bones (Figure 5; D to I). As is the case at WT sites of initial mineralization, MVs contained needle-like apatite crystals in Enpp1−/− and [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−]-deficient growth plates and bone (Figure 5; A, D, and G). In Enpp1−/− and [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−]-deficient bones there was a thicker layer of unmineralized osteoid, characterized by more exposed type I collagen fibrils containing partly mineralized MVs (Figure 4; C, F, and I). The finding of more osteoid at primary sites of bone mineralization is an indication of osteomalacia, ie, inadequate mineralization.

Figure 5.

Transmission electron microscopy of mineralization sites in growth plate and medullary bone matrix of WT (A–C), Enpp1−/− (D–F), and [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] (G–I) mice. A, D, and G compare early mineralization in upper growth plates; B, E, and H compare the calcified zones of lower growth plates; and C, F, and I compare surfaces of newly formed bone trabeculae in the metaphyses. Note the granularity of mineral in Enpp1−/− and Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/− bones plus markedly increased uncalcified bone osteoid in the non-WT bones. Arrows indicate partially or fully calcified MVs in growth plate cartilage (A, D, G) and partially or fully calcified osteoid (C, F, I). Original magnifications: ×151,000 (A); ×143,000 (D, G); ×37,000 (B); ×98,000 (E); ×49,000 (H); ×29,000 (C); ×33,000 (F); ×40,000 (I).

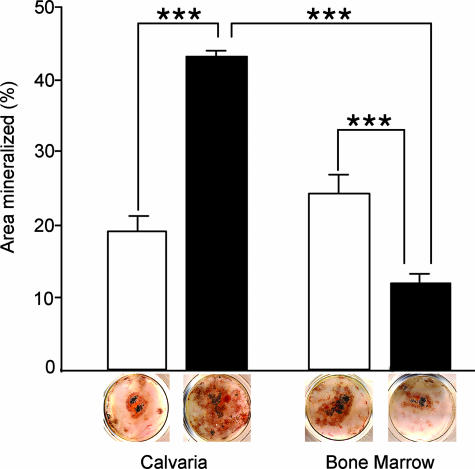

In Vitro Analysis of Osteoblast Differentiation

To further examine the site-specific effects of NPP1 deficiency we performed in vitro analysis of osteoblast differentiation from osteoprogenitor cells using both primary calvarial- and bone marrow-derived osteoblasts and compared the ability of these cells to differentiate into mineralizing osteoblasts using the well-established bone nodule assay.29 As has been previously shown, nodule assays show that calvarial osteoblasts from Enpp1−/− mice display increased mineral deposition in comparison to WT control cultures (Figure 6). Interestingly however, we observed the opposite phenotype in bone marrow-derived osteoblast cultures from long bones. These cultures demonstrated that calcified nodule formation was in fact inhibited in Enpp1−/− bone marrow cultures in comparison to WT cells and overall the amount of mineral deposited in these cultures was significantly decreased in comparison to WT levels (Figure 6). As is the caveat with all primary culture systems, cultures of osteogenic cells do not represent a pure population of osteoprogenitor cells and one must assume the presence of other cell types that are not of the osteoprogenitor lineage. We determined that the rate of proliferation between WT and Enpp1−/− calvarial and bone marrow cells was equal (data not shown). Therefore, the difference we observe in the amount of mineral produced at the end of culture period is a function of the differentiation capacity of the cells, and not of the growth rate. Overall, given our in vivo analysis demonstrating an osteomalacic phenotype in tibia and our in vitro data, demonstrating that bone marrow-derived osteoblasts do not produce as much mineral as WT cells, demonstrate that loss of NPP1 activity affects skeletal sites in a site-specific manner.

Figure 6.

Calvarial and bone marrow-derived osteoblast differentiation assay. Osteoblast-like cells were isolated from WT and Enpp1−/− calvaria and bone marrow as described in the Materials and Methods. Cells were cultured in the presence of ascorbic acid (50 μg/ml) and β-glycerophosphate (10 mmol/L) for 21 days, cells were fixed and stained for alkaline phosphatase activity (red staining) followed by von Kossa staining for mineral (brown/black staining). The area of the culture well covered by alkaline phosphatase-positive, mineralized nodules was quantified using a point-counting method and was expressed as the percentage surface area mineralized. WT osteoblasts (white bars) and Enpp1−/− osteoblasts (black bars) were tested. Data represent the mean ± SEM from triplicate wells. ***, P < 0.001 posthoc test after significant two-way analysis of variance.

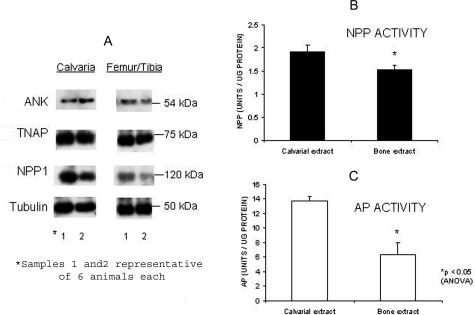

Comparison of NPP1 versus TNAP Expression in Calvaria versus Long Bones

Overall, the immunohistochemical staining intensities for NPP1 were similar in both tibias and vertebrae of WT mice, with maximal staining intensity in prehypertrophic and hypertrophic chondrocytes of the growth plate and in osteoblasts of tibias versus vertebrae (data not shown). However, Western blots showed a reduced expression of NPP1 protein in femur/tibia bone samples versus calvarial bone samples (Figure 7A), while TNAP protein expression was approximately equivalent in femur/tibia versus calvarial bone samples (Figure 7A). In contrast to the Western blot data showing equivalent TNAP protein in calvaria and femur/tibia, the enzymatic activities of both TNAP and NPP1 were significantly increased in calvaria versus femur/tibia bone extracts (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Protein and enzymatic characterization of TNAP and NPP1 in WT calvaria and long bones. Six WT mice were euthanized at 3 days of age. The calvaria were cut into two equal halves and the halves were pooled to constitute two equivalent samples (no. 1 and no. 2), representative of six animals each. The right-sided femurs and tibias of the six animals were pooled (sample no. 1) and compared to a separate pool of six left-sided tibias and femurs (sample no. 2). Comparison was by immunoblotting (A), analysis of enzymatic activity of NPP1 (B) and TNAP (C), and was performed using 5 μg of total protein per sample in triplicate. *, P < 0.5.

Discussion

In this study, we report that the effects of NPP1 deficiency on mineral deposition are site-specific. As previously reported, Enpp1−/− mice display spontaneous calcification of soft tissues.21,24,30 However we document here that these mice also display moderate to severe hypomineralization in the long bones. We have previously shown that simultaneous deletion of Akp2 and Enpp1 dramatically normalizes the hypo- and hypermineralization defects in calvaria and spine of the Akp2−/− and Enpp1−/− mice, respectively. However, in this study we show that this rescue is site-specific and extends only to the calvaria, spine, and incompletely in the metatarsals, in [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] double-deficient mice. Hypomineralization of the long bones remains, despite the dramatic amelioration of the mineral deficits at other sites and the systemic correction of circulating PPi levels.20

Another mouse model of NPP1 deficiency has been described, the ttw/ttw tiptoe walking mouse (previously termed twy/twy), which is a naturally occurring mutant that, like the Enpp1−/− mouse, exhibits pathological ossification of the spinal ligaments similar to ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament.17 However, a state of osteopenia has also been demonstrated in the ttw/ttw mouse model of NPP1 deficiency,17,21,31 despite the marked spontaneous pathological soft tissue calcification also present. In addition, abnormalities in matrix synthesis, reflected by heightened type XI collagen expression at calcifying ligaments and sustained elevation of collagen production by primary ttw/ttw calvarial osteoblasts have also been documented.30 Given that the ttw/ttw mice are very similar to the Enpp1−/− mice, these data support our finding that lack of NPP1-mediated PPi production affects mineralization of skeletal sites in a selective manner.

Okawa and colleagues,21 described an amelioration of the osteopenic phenotype of ttw/ttw mice by administration of calcitonin. Calcitonin’s main biological function is to inhibit osteoclast activity, and it has been successfully used in treatment of diseases caused by increased osteoclastic activity such as Paget’s disease.32 The successful treatment of osteopenia in ttw/ttw mice by calcitonin suggests that in these mice, and perhaps also in Enpp1−/− mice, a state of increased osteoclastic activity leads to bone loss, albeit only at certain sites. Maintenance of normal bone mass occurs due to a tight balance between bone formation via osteoblasts and bone resorption via osteoclasts, and these cells are tightly coupled to each other. In a NPP1-deficient state, increased osteoclast activity could occur in an attempt to balance the increased mineral deposition caused by NPP1 deficiency. Alternatively, PPi may function to limit osteoclast activity, and in Enpp1−/− mice abnormally low levels of PPi may lead to increased osteoclastic bone resorption. PPi is chemically analogous to the bisphosphonate family of drugs, which potently inhibit osteoclast activity by inducing apoptosis.5,33 However, it remains to be seen whether Enpp1−/−-derived osteoclasts display increased number or resorptive activity.

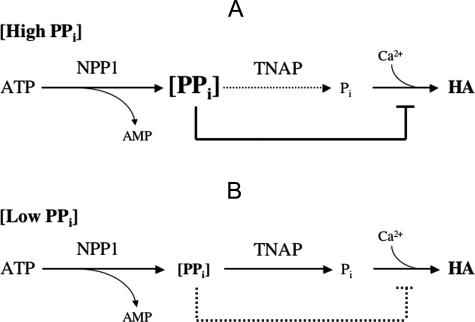

We speculate that the hypermineralization in NPP1-deficient mouse calvaria and vertebrae is based on the known mineralization inhibitory effects of inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi)4,6,5 versus the mineral promoting effects of orthophosphate (Pi).12,13 When present in vivo at supraphysiological concentrations, PPi inhibits calcium phosphate mineral formation by coating HA crystals, thus preventing mineral crystal growth and proliferative self-nucleation.5 In tissues where high NPP1 enzyme activity releases more than sufficient PPi to balance Pi generation, an overall balance of mineral formation rate would be expected in which TNAP stimulates mineral formation while NPP1 generation of high levels of PPi inhibits and prevents excessive HA mineral deposition (Figure 8A). At sites such as calvaria and vertebrae, an abnormal reduction in NPP1 activity, as would occur in Enpp1−/− mice, should result in unopposed Pi generation leading to excessive mineralization (Figure 8B). At these sites, a balancing deletion of Akp2 would be expected to restore a more normal balance between local concentrations of PPi and Pi, and, thus, should at least partially restore normal mineralization. This is what we have observed in calvaria and vertebrae of [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] double-knockout mice.20

Figure 8.

Diagram outlining the differential effects of high and low extracellular PPi concentrations on HA formation. ATP hydrolysis by NPP1 produces inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi), which can be further hydrolyzed by TNAP to yield orthophosphate (Pi). The resulting Pi molecules are incorporated into HA mineral. A: High levels of nonhydrolyzed PPi block the formation of calcium phosphate mineral.4–6 B: Instead, under low extracellular PPi concentrations, the effect of PPi is mostly stimulatory2 as it is rapidly hydrolyzed by TNAP into Pi and incorporated into HA.

However, in contrast to the mechanism discussed above, in which high endogenous PPi levels in calvaria and vertebrae would have an inhibitory effect on mineralization, the ability of near physiological concentrations of PPi, in the range of 0.1 mmol/L,34 to stimulate mineralization has been observed in organ-cultured chick femurs.2 Also, we have recently observed that near physiological concentrations of PPi (0.01 up to 0.1 mmol/L) can stimulate HA deposition as initiated by isolated rat MVs, whereas higher concentrations more than 1 mmol/L inhibit mineral deposition.35 Given that at physiological pH the Km of TNAP for PPi is ∼0.5 mmol/L,36 at this range of physiological extracellular PPi concentrations35 most PPi would be hydrolyzed to orthophosphate (Pi) by TNAP (Figure 8B) thus providing Pi for incorporation into nascent mineral. The process of mineral formation would be further augmented by TNAP hydrolysis of any mild excess PPi, thus removing persistent mineral inhibiting effects of higher PPi concentrations. However, in tissues where there is a relatively high endogenous NPP1 activity, such as the cranium, vertebrae, and ligaments (Figure 7), higher endogenous levels of PPi generation would exceed the ability of local TNAP and other endogenous pyrophosphatases to metabolize PPi to Pi. The result would be persistently high local concentrations of PPi, rising to levels more than 1 mmol/L. This would be inhibitory to mineral deposition. Because the PPi-generating effect of NPP1 is augmented by ANK-mediated PPi transport to the extracellular fluid, this could help explain the hypermineralization of ligaments and cartilage seen in humans and mice suffering from a genetic deficiency of ANK.24,37–39

In summary, new data are presented showing hypomineralization of long bones in Enpp1−/− mice and that this deficit is more severe in the [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] double deficiency. The hypomineralization observed in long bones of Enpp1−/− mice may be related to relatively lower levels of endogenous NPP1 expression throughout the long bones. Thus, in long bones, a major effect of complete deletion of NPP1 activity would be further reducing extracellular PPi to abnormally low levels, ie, below levels at which TNAP would have sufficient PPi substrate to generate Pi for normal mineral formation. Such a Pi deficiency resulting from inadequate PPi hydrolysis by TNAP would be made worse in the [Akp2−/−; Enpp1−/−] double deficiency in which not enough PPi would be generated by NPP1 nor hydrolyzed by TNAP to support a normal mineralization rate.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to H. Clarke Anderson, M.D., Dept. of Pathology and Lab Medicine, University of Kansas Medical Center, 3901 Rainbow Blvd., Kansas City, KS 66160. E-mail: handerso@kumc.edu.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants DE05262, AR47908, AG07996, and DE12889) and the Veterans Administration Research Service.

References

- Anderson HC. Vesicles associated with calcification in the matrix of epiphyseal cartilage. J Cell Biol. 1969;41:59–72. doi: 10.1083/jcb.41.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson HC, Reynolds JR. Pyrophosphate stimulation of calcium uptake into cultured embryonic bones. Fine structure of matrix vesicles and their role in calcification. Dev Biol. 1973;34:211–227. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(73)90351-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson HC. Molecular biology of matrix vesicles. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1995;314:266–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleisch H, Straumann F, Schenk R, Bizaz S, Allgower M. Effect of condensed phosphates on calcification of chick embryo femurs in tissue culture. Am J Physiol. 1966;211:821–825. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1966.211.3.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis MD, Russell RGG, Fleisch H. Diphosphonates inhibit formation of calcium phosphate crystals in vitro and pathological calcification in vivo. Science. 1969;165:1264–1266. doi: 10.1126/science.165.3899.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell RGG, Muhlbauer RS, Bisaz S, Williams DA, Fleisch H. The influence of pyrophosphate, condensed phosphates, phosphonates and other phosphate compounds on the dissolution of hydroxyapatite in vitro and on bone resorption induced by parathyroid hormone in tissue culture and in thyroparathyroidectomized rats. Calcif Tissue Res. 1970;6:183–196. doi: 10.1007/BF02196199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narisawa S, Fröhlander N, Millán JL. Inactivation of two mouse alkaline phosphatase genes and establishment of a model of infantile hypophosphatasia. Dev Dyn. 1997;208:432–446. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199703)208:3<432::AID-AJA13>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedde KN, Blair L, Silverstein J, Coburn SP, Ryan LM, Weinstein RS, Waymire K, Narisawa S, Millán JL, McGregor GR, Whyte MP. Alkaline phosphatase knockout mice recapitulate the metabolic and skeletal defects of infantile hypophosphatasia. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:2015–2026. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.12.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte MP. Hypophosphatasia. New York: McGraw Hill,; The Metabolic and Molecular Basis of Inherited Disease. 2001:pp 5313–5329. [Google Scholar]

- Ali SY, Sajdera SW, Anderson HC. Isolation and characterization of calcifying matrix vesicles from epiphyseal cartilage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1970;67:1513–1520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.67.3.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzawa T, Anderson HC. Phosphatases of epiphyseal cartilage studied by electron microscopic cytochemical methods. J Histochem Cytochem. 1971;19:801–808. doi: 10.1177/19.12.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali SH, Evans L. The uptake of [45Ca] calcium ions by matrix vesicles isolated from calcifying cartilage. Biochem J. 1973;134:647–650. doi: 10.1042/bj1340647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu HHT, Anderson HC. Calcification of isolated matrix vesicles and reconstituted vesicles from fetal bovine cartilage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:3805–3808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson HC, Cecil R, Sajdera SW. Calcification of rachitic rat cartilage by extracellular matrix vesicles. Am J Pathol. 1975;70:237–254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson HC, Hsu HHT, Morris DC, Fedde KN, Whyte MP. Matrix vesicles in osteomalacic hypophosphatasia bone contain apatite-like mineral crystals. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:1555–1561. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson HC, Sipe JB, Hessle L, Dhanyamraju R, Atti E, Camacho NR, Millán JL. Impaired calcification around matrix vesicles of growth plate and bone in alkaline phosphatase deficient mice. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:841–848. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63172-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okawa A, Nakamura I, Goto S, Moriya H, Nakamura Y, Ikigawa S. Mutation in Npps in a mouse model of ossification of the posterior ligament of the spine. Nat Genet. 1998;19:271–273. doi: 10.1038/956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutsch F, Vainzankar S, Johnson K, Goldfine I, Maddux B, Schauerta P, Kalkoff H, Sano K, Boisvert WA, Superti-Furga A, Terkeltaub R. PC-1 nucleoside triphosphate pyrophosphohydrolase deficiency in idiopathic infantile arterial calcification. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:543–554. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63996-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto M, Hosoda Y, Kojimahara K, Yamazaki T, Yoshimura Y. Arthritis and ankylosis in twy mice with hereditary multiple osteochondral lesions: with special reference to calcium deposition. Pathol Int. 1994;44:420–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1994.tb01705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessle L, Johnson KA, Anderson HC, Narisawa S, Sali A, Gooding JW, Terkeltaub R, Millán JL. Tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase and plasma cell membrane glycoprotein-1 are central antagonistic regulators of bone mineralization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:9445–9449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142063399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okawa A, Goto S, Moriya H. Calcitonin simultaneously regulates both periosteal hyperostosis and trabecular osteopenia in the spinal hyperostotic mouse (twy/twy) in vivo. Calcif Tissue Int. 1999;64:239–247. doi: 10.1007/s002239900610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sali A, Favaloro JM, Terkeltaub R, Goding JW. Germline deletion of the nucleoside triphosphate pyrophosphohydrolase (NTPPPH) plasma cell membrane glycoprotein-1 (PC-1) produces abnormal calcification of periarticular tissues. Vanduffel L, Lemmems R, editors. Maastricht, The Netherlands: Shaker Publishing BV,; Ecto-ATPases and Related Ectoenzymes. 1999:pp 267–282. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore S, Whitson SW, Bowers DE. A simple method using alizarin red S for the detection of calcium in epoxy-resin embedded tissue. Stain Technol. 1986;61:89–92. doi: 10.3109/10520298609110714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmey D, Hessle L, Narisawa S, Johnson KA, Terkeltaub R, Millán JL. Concerted regulation of inorganic pyrophosphate and osteopontin by Akp2, Enpp1 and Ank. An integrated model of the pathogenesis of mineralization disorders. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1199–1209. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63208-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KA, Hessle L, Vainganker S, Wennberg C, Mauro S, Narisawa S, Goding JW, Sano K, Millán JL, Terkeltaub R. Osteoblast tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP) functions to both antagonize and regulate the mineralization inhibitor PC-1. Am J Physiol. 2000;279:R1365–R1377. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.4.R1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaingankar SM, Fitzpatrick TA, Johnson K, Goding JW, Maurice M, Terkeltaub R. Subcellular targeting and function of osteoblast nucleotide pyrophosphatase phosphodiesterase 1. Am J Physiol. 2004;286:C1177–C1187. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00320.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KA, Johnson K, Hashimoto S, Lotz M, Pritzker K, Goding J, Terkeltaub R. Up-regulated expression of the phosphodiesterase nucleotide pyrophosphatase family member PC-1 is a marker and pathogenic factor for knee meniscal cartilage matrix calcification. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1071–1081. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200105)44:5<1071::AID-ANR187>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narisawa S, Harmey D, Magnusson P, Millan JL: Conserved epitopes in human and mouse tissue, non-specific alkaline phosphatase. Tumor Biol (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellows CG, Ciaccia A, Heersche JN. Osteoprogenitor cells in cell populations derived from mouse and rat calvaria differ in the response to corticosterone, cortisol and cortisone. Bone. 1998;23:119–125. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K, Goding J, Van Etten D, Sali A, Hu S-I, Farley D, Krug H, Hessle H, Millán JL, Terkeltaub R. Linked deficiencies in extracellular inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) and osteopontin expression mediate pathologic ossification in PC-1 null mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:994–1004. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.6.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki M, Moriya H, Goto S, Saitou Y, Arai K, Nagai Y. Increased type XI collagen expression in the spinal hyperostotic mouse (twy/twy). Calcif Tissue Int. 1991;48:182–189. [Google Scholar]

- Rodan GA, Martin TJ. Therapeutic approaches to bone diseases. Science. 2000;289:1508–1514. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleisch HA, Russell RG, Bisaz S, Muhlbauer RC, Williams DA. The inhibitory effect of phosphonates on the formation of calcium phosphate crystals in vitro and on aortic and kidney calcification in vivo. Eur J Clin Invest. 1970;1:12–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1970.tb00591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HR, Walker PG. Occurrence of pyrophosphate in bone. J Bone Joint Surg. 1958;40B:333–339. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.40B2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson HC, Garimella R, Tague SE. The role of matrix vesicles in growth plate development and biomineralization. Front Biosci. 2005;10:822–837. doi: 10.2741/1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Mauro S, Manes T, Hessle H, Kozlenkov A, Pizauro JM, Hoylaerts MF, Millán JL. Kinetic characterization of hypophosphatasia mutations with physiological substrates. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:1383–1391. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.8.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho AM, Johnson MD, Kingsley DM. Role of the mouse ank gene in control of tissue calcification and arthritis. Science. 2000;289:225–226. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5477.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubata T, Sato K, Kawano H, Yamamoto S, Hirano A, Hashizumi Y. Ultrastructure of early calcification in cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. J Neurosurg. 1984;61:131–135. doi: 10.3171/jns.1984.61.1.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurnberg P, Thiele H, Chandler D, Hohne W, Cunningham ML, Ritter H, Leschik G, Uhlmann K, Mischung C, Harrop K, Goldblatt J, Borochowitz ZU, Kotzot D, Westermann F, Mundlos S, Braun HS, Laing N, Tinschert S. Heterozygous mutations in ANKH, the human ortholog of the mouse progressive ankylosis gene, result in craniometaphyseal dysplasia. Nat Genet. 2001;28:37–41. doi: 10.1038/ng0501-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]