Abstract

Chronic Chagas’ disease cardiomyopathy is a leading cause of congestive heart failure in Latin America, affecting more than 3 million people. Chagas’ cardiomyopathy is more aggressive than other cardiomyopathies, but little is known of the molecular mechanisms responsible for its severity. We characterized gene expression profiles of human Chagas’ cardiomyopathy and dilated cardiomyopathy to identify selective disease pathways and potential therapeutic targets. Both our customized cDNA microarray (Cardiochip) and real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction analysis showed that immune response, lipid metabolism, and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation genes were selectively up-regulated in myocardial tissue of the tested Chagas’ cardiomyopathy patients. Interferon (IFN)-γ-inducible genes represented 15% of genes specifically up-regulated in Chagas’ cardiomyopathy myocardial tissue, indicating the importance of IFN-γ signaling. To assess whether IFN-γ can directly modulate cardio-myocyte gene expression, we exposed fetal murine cardiomyocytes to IFN-γ and the IFN-γ-inducible chemokine monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. Atrial natriuretic factor expression increased 15-fold in response to IFN-γ whereas combined IFN-γ and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 increased atrial natriuretic factor expression 400-fold. Our results suggest IFN-γ and chemokine signaling may directly up-regulate cardiomyocyte expression of genes involved in pathological hypertrophy, which may lead to heart failure. IFN-γ and other cytokine pathways may thus be novel therapeutic targets in Chagas’ cardiomyopathy.

Chagas’ disease, caused by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in Central and South America, affecting ∼9 million people.1 Approximately 30% of Chagas’ disease patients develop chronic Chagas’ disease cardiomyopathy (CCC), a particularly aggressive inflammatory dilated cardiomyopathy that occurs decades after the initial infection. Clinical progression and survival are significantly worse in CCC patients as compared with patients with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) of other etiologies.2,3 Significantly, myocarditis is found in 93% and 8% of biopsies from CCC and DCM samples, respectively.4,5

CCC heart lesions show histopathological findings consistent with inflammation and a myocardial remodeling process: T cell/macrophage-rich myocarditis, hypertrophy, and fibrosis with heart fiber damage.4 Increased local expression of the cytokines interferon-(IFN)-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α,6,7 interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-4,6 as well as HLA class I and II molecules, and adhesion molecules were reported.8 Autoimmune inflammation may play a role in the myocarditis of CCC.9 In murine models, local production of tumor necrosis factor-α, IFN-γ, and IFN-γ-induced chemokines monokine induced by IFN-γ (MIG), regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES), IFN-γ-inducible protein (IP-10), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α) was reported.10 CCC patients display up-regulated production of IFN-γ in comparison to asymptomatic T. cruzi-infected individuals,7,11 and up-regulated production of IFN-γ in T. cruzi-infected IL-4−/− mice enhanced late-phase myocarditis,12 suggesting a pathogenic role for IFN-γ. Together, these observations suggest that chronic myocardial inflammation could contribute to CCC pathogenesis. Accordingly, we hypothesized that the increased aggressiveness of CCC may be due to the activation of specific disease pathways as reflected by a distinct heart gene expression profile. Expression profiling studies were performed in hearts of mice 3 months after T. cruzi infection, identifying up-regulation of MHC class I and class II genes, cytokines, chemokines, and receptors, among other genes.13,14 However, there has not yet been a comparable study using human patients.

In this study, we used a 10,386-element cDNA microarray, built from cardiovascular cDNA libraries, in combination with real-time reverse transcriptase (RT)-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis to develop the first gene expression profile of CCC using human heart tissue. We compared the gene expression fingerprint of CCC with that of DCM, using nonfailing adult hearts as expression controls, and found that gene expression patterns are markedly different in CCC and DCM, with significant activity of IFN-inducible genes in CCC patients. Gene expression changes of cultured cardiomyocytes in response to IFN-γ and MCP-1 were also studied. These results provide intriguing clues to the molecular mechanisms of this disease and may suggest future targets for specific therapy.

Materials and Methods

Isolation of RNA

RNA samples for the cDNA array analysis came from explanted left ventricular-free wall heart samples from five CCC (serological diagnosis, positive epidemiology) and seven DCM (dilated cardiomyopathy in the absence of ischemic disease, negative epidemiology) end-stage heart failure patients was obtained at transplantation (Table 1). Normal adult heart tissue from the left ventricular-free wall was obtained from four nonfailing donor hearts not used for cardiac transplantation due to size mismatch with available recipients. CCC and DCM patients had been treated with standard heart failure therapy with angiotensin conversion enzyme inhibitors, loop diuretics, and β-blockers; none were receiving amiodarone or milrinone at the time of sample collection. CCC patients were not under anti-trypanosomal treatment. To avoid inclusion of samples undergoing clinicopathological changes secondary to long-standing brain death in the normal donor heart control group, we excluded samples displaying up-regulation of cardiac hypertrophy genes (natriuretic peptides, α-cardiac actin, myosin light chain-2) greater than twofold in comparison to average expression of each gene in all normal donor heart samples. RNA from endomyocardial biopsy samples from four end-stage CCC patients were also obtained and used for the real-time RT-PCR experiments. Total RNA was isolated with the TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies Inc., Grand Island, NY); we determined RNA quantity by A260/280 measurement and assessed RNA integrity by formaldehyde gel electrophoresis. The protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of University of São Paulo School of Medicine, São Paulo, SP, Brazil, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA. Informed consent was obtained from donors. Characteristics of patients and normal donors whose samples were used in this study are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients and Normal Heart Donors Whose Samples Were Used in This Study

| Internal no. | Age (years) | Sex | Disease group | Nature | Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCC patients | |||||

| CCC2 | 47 | F | End-stage CCC | Explant (LVFW) | cDNA array |

| CCC5 | 53 | M | End-stage CCC | Explant (LVFW) | cDNA array |

| CCC1 | 49 | M | End-stage CCC | Explant (LVFW) | cDNA array, RT-PCR |

| CCC3 | 27 | M | End-stage CCC | Explant (LVFW) | cDNA array, RT-PCR |

| CCC4 | 63 | F | End-stage CCC | Explant (LVFW) | cDNA array, RT-PCR |

| CCC6 | 52 | M | End-stage CCC | Endomyocardial biopsy | RT-PCR |

| CCC7 | 51 | M | End-stage CCC | Endomyocardial biopsy | RT-PCR |

| CCC8 | 49 | M | End-stage CCC | Endomyocardial biopsy | RT-PCR |

| CCC9 | 50 | M | End-stage CCC | Endomyocardial biopsy | RT-PCR |

| DCM patients | |||||

| DCM1 | 39 | F | End-stage DCM | Explant (LVFW) | cDNA array, RT-PCR |

| DCM2 | 23 | F | End-stage DCM | Explant (LVFW) | cDNA array, RT-PCR |

| DCM3 | 50 | M | End-stage DCM | Explant (LVFW) | cDNA array, RT-PCR |

| DCM4 | 45 | F | End-stage DCM | Explant (LVFW) | cDNA array, RT-PCR |

| DCM5 | 38 | M | End-stage DCM | Explant (LVFW) | cDNA array, RT-PCR |

| DCM6 | 45 | M | End-stage DCM | Explant (LVFW) | cDNA array, RT-PCR |

| DCM7 | 26 | F | End-stage DCM | Explant (LVFW) | cDNA array, RT-PCR |

| Normal samples* | |||||

| N1 | 38 | F | Normal heart donor | Explant (LVFW) | cDNA array, RT-PCR |

| N2 | 24 | M | Normal heart donor | Explant (LVFW) | cDNA array, RT-PCR |

| N3 | 16 | M | Normal heart donor | Explant (LVFW) | cDNA array, RT-PCR |

| N4 | 38 | F | Normal heart donor | Explant (LVFW) | cDNA array, RT-PCR |

Samples were collected between June 1992 and January 2001. LVFW, left ventricle free wall; explant, surgical sample obtained during heart transplantation; endomyocardial biopsy obtained pre-transplantation. Only explant samples were used for cDNA array. Some explant samples were used for cDNA array and quantitative real-time RT-PCR expression analysis. Heart failure patients received standard therapy with angiotensin conversion enzyme inhibitors, loop diuretics and beta-blockers.

Normal heart donors were subject to ventilator and vasoactive drugs, and had been under life support for an average of 48 hours (range, 24 to 96 hours).

Construction of a Spotted cDNA Microarray

We spotted 10,368 nonredundant PCR products from a human heart cDNA library (including 96 bacterial clones as negative controls) onto Corning CMT-GAPS amino-silane-coated glass microarray slides (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) using the GMS 417 arrayer (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA), and postprocessed the slides according to the manufacturer’s manual.15 The unique clones include 2496 known genes, (24.3%), of which 1713 are classified according to function, 3296 matched expressed sequence tags (32.1%), and 4480 novel genes (43.6%), as previously described.15

Synthesis of cDNA Probes and Subsequent Hybridization

We followed procedures previously described for probe generation by RT-PCR and hybridization.16 Universal Reference RNA (Stratagene, Cedar Creek, TX) was used as a control for each slide. We converted 10 μg of RNA from each RNA sample to a cDNA probe via reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR—each RNA sample was oligo-dT primed and then added to a master mix containing nucleotides, the reverse transcription enzyme, corresponding buffers, and Cy3- or Cy5-dUTP fluorescent dye (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Cy5-labeled probes were always made from myocardial sample RNA, and Cy3-labeled probes were always made from Universal Reference RNA. After the RT-PCR reaction, corresponding pairs of Cy3- and Cy5-labeled probes were mixed and applied to the arrayed slides; after hybridization, slides were scanned using the GMS 418 array scanner (Affymetrix). We considered hybridization experiments from the five distinct CCC patients, as well as the seven distinct DCM patients, as biological replicates.

Image Acquisition and Data Processing

We processed newly-scanned images using ScanAlyze v2.44 (Michael Eisen, Stanford University, Stanford, CA; http://rana.lbl.gov/eisensoftware.htm). We used 96 spots representing bacterial clones as a negative control. Spots with net signal intensities that were less than twice the median intensities of the bacterial clones on both channels were eliminated to exclude nonspecific binding.

Bioinformatics

Data normalization and analysis was performed using GeneSpring version 6.0 (Silicon Genetics, Redwood City, CA). Expression levels were first normalized relative to the other genes in the same sample—each measurement was divided by the 50th percentile of all measurements in that sample. In addition, disease samples were normalized to normal control samples; when calculating the mean of the control measurements only those measurements were included that had at least a normalized value of 0.01. After normalization, samples in each disease group (CCC, DCM, normal) were then treated as replicates and averaged. In this way, we obtained a final expression ratio for each gene in CCC and DCM, relative to normal controls. A gene was considered to be significantly up- or down-regulated if the average sample/control expression ratio in a disease group was both 1.5-fold higher or lower than the average expression values in the control samples, and the difference between patient group and control expression values passed statistical significance (P < 0.05). We performed hierarchical clustering analysis on the filtered microarray data using GeneSpring version 6.0 (Silicon Genetics), using nonsupervised clustering and correlation by up-regulated expression, with default parameters. We considered the median Cy5/Cy3 intensity ratio for each spot to be its intensity value for analytical purposes. Genes of known function in the Cardiochip version 6.0 cDNA microarray were classified into functional categories (cell division, cell signaling/communication, cell structure/motility, cell/organism defense, gene/protein expression, metabolism) and related subcategories, as described before.17,18

Real-Time Reverse Transcriptase(RT)-PCR Analysis

We designed forward and reverse primers for quantitative real-time RT-PCR to confirm expression patterns or to analyze genes not present in the array: IL-7 receptor, IFN-γ receptor, atrial natriuretic factor (ANF), human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DR, chemokines stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1), RANTES, MCP-1, IP-10, MIG, and chemokine receptors (CCR1, CCR2, CXCR3, CXCR4, CCR5) using the Primer3 internet site (http://www-genome.wi.mit.edu/cgi-bin/primer/primer3_www.cgi). Primers were 19 to 21 bases long, had a melting point of 59 to 61°C, generating PCR products of 100 to 150 bp. Using RNA samples from CCC, DCM, and donor control heart used in cDNA array analysis as well as additional endomyocardial biopsy samples of CCC samples, we performed 50-μl real-time RT-PCR reactions in 96-well plates, using SYBR-Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), in the Perkin-Elmer ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system. (15 seconds at 94°C and 1 minute at 60°C) as described.15 Normalization and fold change were calculated with the ΔΔCt method with GAPDH as the reference mRNA species according to ABI Prism 7700 manufacturer’s instructions. Statistical significance was defined by P < 0.05 using two-tailed Student’s t-test. Real-time RT-PCR was also used to investigate the effect of cytokines in cardiomyocyte gene expression. Heart cell cultures from hearts of 20-day-old embryonic mice were prepared as described,19 incubated with IFN-γ (100 U/ml; R&D Diagnostics, Minneapolis, MN) and/or MCP-1 (10 ng/ml; Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) for 8 hours before RNA extraction; primers for murine ANF were designed as described above.

Results

Cluster Analysis

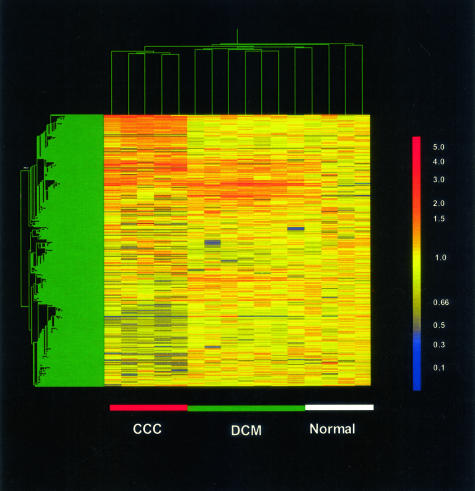

When we subjected gene expression data obtained on the Cardiochip microarray to hierarchical cluster analysis (Figure 1), all of the CCC, and most of the DCM and normal heart samples (Figure 1, individual columns; green dendrograms on the top) clustered together with other members of their groups, with a single DCM patient clustering with a normal heart sample. This showed the consistency of disease-specific gene expression. Gene expression clusters (Figure 1, lines; green dendrograms to the left) specific to CCC, as the up-regulated cluster on the top, or the down-regulated cluster toward the bottom of the figure, along with gene clusters shared between CCC and DCM or DCM-specific, were clearly demonstrated.

Figure 1.

Cluster analysis of gene expression (Cardiochip version 6.0 microarray data) in the CCC, DCM, and N left ventricular-free wall heart tissue mRNA samples. Data reveals CCC- and DCM-specific global gene expression profiles, with disease-specific and shared clusters of up- or down-regulated genes. Each individual column stands for the gene expression pattern of an individual heart mRNA sample belonging to CCC, DCM, or N groups; green dendrograms on the top of the figure represent degrees of similarity of gene expression among samples. Each horizontal line (y-axis) corresponds to the expression of a single gene across all samples. Gene expression clusters (green dendrograms to the left of the figure) represent relatedness of expression patterns among the 10,368 genes across several samples and patient groups. Expression values for each gene in each sample in relation to average control values normal tissue samples are expressed in a color scale (right of figure): yellow, unchanged; orange-red, up-regulated; blue, down-regulated. Nonsupervised hierarchical clustering performed with Genespring version.6.0, using correlation by up-regulated expression with default parameters, of microarray results for five CCC, seven DCM, and four normal heart tissue samples. Samples from each disease group are marked to facilitate their identification, with red, green, and white, standing for samples for CCC, DCM, and normal donor heart, respectively.

Differential Gene Expression Profiles in CCC, DCM, and Normal Heart Tissue

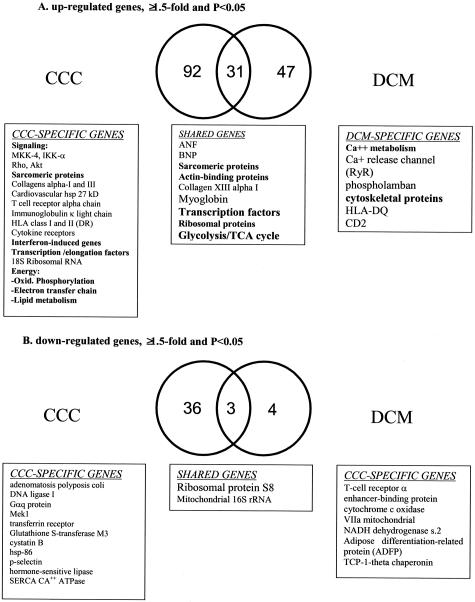

Using a 1.5-fold and P < 0.05 cutoff, 582 and 364 genes were significantly up-regulated in CCC and DCM, respectively, including 126 genes that were up-regulated in both conditions. Similarly, 465 genes were significantly down-regulated in CCC and 32 in DCM. We classified differentially expressed genes of known function into subcategories as mentioned in Material and Methods (Figures 2 and 3; and in Supplemental Material at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Figure 2.

Venn diagram, CCC-specific, DCM-specific, and shared classified, nonredundant genes of known function in end-stage heart failure samples, as assessed by cDNA microarrays. Selected genes and gene groups (in boldface) are listed in boxes below each area. A: Genes up-regulated ≥1.5-fold, P < 0.05. B: Genes down-regulated ≥1.5-fold, P < 0.05.

Figure 3.

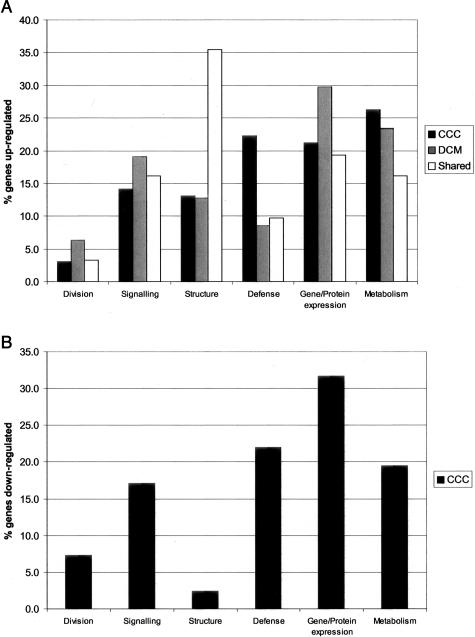

A: The percentage of known genes in each functional category that are up-regulated exclusively in myocardial samples from CCC, DCM, or shared by both diseases. B: Percentage of down-regulated known genes in each functional category in CCC. Representation of genes in each category among up-regulated genes in a patient group was calculated as follows: number of up-regulated genes in the category/total number of known up-regulated genes in that patient group. The same was performed for each patient sample, for the shared gene list, and for the down-regulated CCC gene list.

Among genes selectively up-regulated in CCC, we observed that the participation of cell defense and metabolism categories was substantially higher than the frequency of representation that categories in the gene array (Figure 2A and Figure 3A). Furthermore, 15 of 16 (94%) cell defense genes up-regulated specifically in CCC are immune response genes, whereas the proportion of immune response genes among cell defense genes in the gene array is 49%. Among these genes, we found the MHC class I/class II molecules, IFN-γ receptor, IL-7 receptor, T-cell antigen receptor, immunoglobulin chains, cytotoxic granule nucleolysin, and IFN-inducible genes (Supplemental Material, http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Nineteen of the up-regulated metabolism genes were related to energy metabolism, including seven proteins of the oxidative phosphorylation and proton transfer chains, and eight enzymes involved in lipid metabolism. Up-regulated structural genes comprise sarcomere-building contractile and cytoskeletal proteins, and collagens I and III. Signaling genes already associated to heart failure,20,21 including angiotensin II receptor 2, G protein β polypeptide 2, several low-molecular weight GTPases such as rhoB, RAB1, RalB, along with IKK-α and mitogen-activated kinase MKK4, protein kinase H11, and its induced anti-apoptotic gene Akt-1, were also up-regulated. We also found factors involved in protein/RNA synthesis, such as hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and TATA-box-binding protein-associated factor, to be up-regulated specifically in CCC samples.

In contrast, the proportion of immune response genes among genes up-regulated in DCM was similar to their representation in the Cardiochip. Most genes selectively up-regulated in DCM belonged to the gene/protein expression category (13 genes, of which 8 encode ribosomal proteins); translation factors are also up-regulated. Of the 11 up-regulated metabolism genes, 5 belong to the glycolysis/sugar metabolism pathway, and none to the lipid metabolism pathway, consistent with known changes of energy metabolism in DCM.22 Several unique signaling elements were up-regulated: ryanodine receptor, phospholamban, ras-related proteins, G protein pathway suppressor 1, cAMP-dependent protein kinase, as described before for dilated cardiomyopathy.15,16,20 Structural genes include mainly cytoskeletal proteins and skeletal muscle tropomyosin. Thirty-one classified, known genes were up-regulated in both CCC and DCM (Figure 2). Structural genes, including cardiac myosin heavy chain, cardiac myosin light chain-2, several α-actin isoforms, smooth muscle myosin, actin-binding proteins, and collagen α XIII, comprised 35% of shared up-regulated genes, followed by protein/gene expression, metabolism (glycolysis/TCA cycle and carbohydrate energy metabolism), and signaling, including natriuretic peptide genes (ANF and brain natriuretic peptide precursor, ion channels, tyrosine kinase ZAP-70). Most of these genes comprise the fetal gene expression program characteristic of the hypertrophic response, and the expression of structural genes is associated to the downstream structural phase of the ventricular remodeling process, common to end-state dilated cardiomyopathy of several etiologies.16,23,24 Among down-regulated known genes (39 in CCC and 7 in DCM), only three are shared by both diseases, among them mitochondrial 16S rRNA (Figure 2, and in Supplemental Material at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Most genes selectively down-regulated in CCC belong to the gene/protein expression, metabolism, and signaling categories (Figure 3B), including SERCA-2 Ca++ ATP-ase, Gαq protein, Mek1, glutathione S-transferase M3, DNA ligase I, transferrin receptor, CREB2, cysteine proteinase inhibitor cystatin B. The finding that structural genes were basically not down-modulated is in line with the significant number of sarcomeric and cytoskeletal genes whose transcription is up-regulated (Supplemental Material, http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Given the prominent local production of IFN-γ in CCC heart lesions,7,11 and because IFN-induced genes were up-regulated in CCC heart lesions, we identified 78 genes present in the Cardiochip cDNA microarray that were reported to be IFN-γ-inducible.25–28 Fifteen percent of the genes selectively up-regulated in CCC are IFN-γ-inducible (Figure 2, Table 2). Significantly, along with inflammatory response genes likely to be expressed by infiltrating inflammatory cells (eg, immunoglobulin, T-cell receptor genes, cytokine receptors), we observed several genes not known to be expressed by inflammatory cells (cardiovascular 27-kd hsp, angiotensin II receptor 2, fatty acid-binding protein 5). Of interest, the SERCA Ca++-ATPase, involved in cardiac calcium metabolism and down-modulated in CCC hearts, is also repressible by IFN-γ. On the other hand, only two IFN-γ inducible genes, polyubiquitin UbC and IFN-γ-inducible mda-9 protein, were up-regulated in DCM; mda-9 is also up-regulated in CCC.

Table 2.

Expression of IFN-γ-Inducible Genes in CCC and DCM Hearts

| Fold | Common name | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|

| A: IFN-γ-inducible genes up-regulated in CCC Lymphoid/inflammatory genes | ||

| 6.1 | Immunoglobulin κ light chain | D90158 |

| 2.1 | Cytotoxic T cell granule nucleolysin TIAR | M96954 |

| 1.6 | MHC class II HLA-DRw11-β-I chain | M21966 |

| Lymphoid and nonlymphoid genes | ||

| 2.7 | Interferon stimulated ISG-54K gene | M14660 |

| 2.3 | Interferon-inducible protein MX1 | M30817 |

| 2.1 | Major histocompatibility complex, class I (HLA-B) | M95531 |

| 2.0 | Tropomyosin TM30 (nm), cytoskeletal | X04588 |

| 1.6 | Interferon-γ receptor | J03143 |

| 1.6 | Interferon consensus sequence DNA-binding protein | M91196 |

| 1.6 | Interferon-γ inducible mda-9 protein* | AF006636 |

| Non-lymphoid genes | ||

| 2.3 | Fatty acid binding protein 5 (psoriasis-associated) | M94856 |

| 1.9 | Angiotensin receptor 2 (AGTR2) | L34579 |

| 1.6 | Cardiovascular 27 kd heat shock protein | R73707 |

| B: IFN-γ down modulated genes, down-regulated in CCC | ||

| 3.1 | SERCA-2 calcium-ATPase (hk2), cardiac | M23278 |

| C: IFN-γ inducible genes up-regulated in DCM | ||

| 1.5 | Polyubiquitin UbC | AB009010 |

| 1.9 | Interferon-γ inducible mda-9 protein* | AF006636 |

Up-regulated in both CCC and DCM.

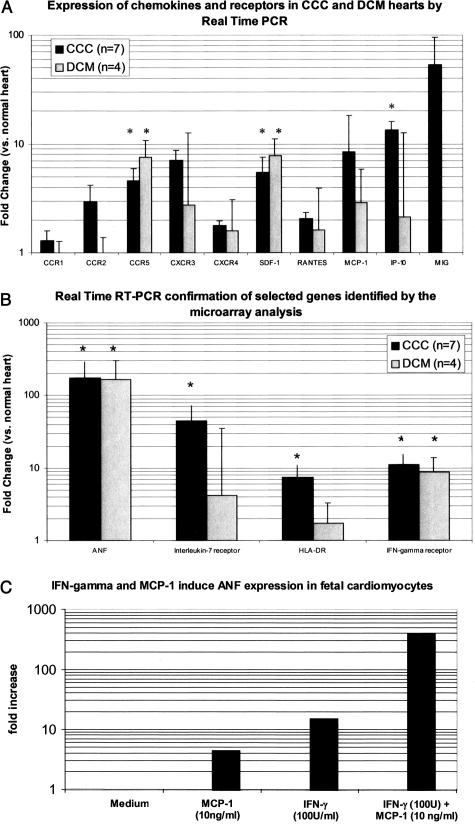

To determine the expression of IFN-γ-inducible chemokines and chemokine receptors (important mediators of the inflammatory response absent from the cDNA array) we conducted real-time RT-PCR experiments, using seven CCC, four DCM, and three normal heart RNA samples. The expression levels of chemokine receptors CCR2, CXCR3, and the IFN-γ-inducible chemokines MCP-1, IP-10, and MIG were selectively up-regulated among CCC samples; the fact that only CCR5, SDF1, IP-10 reached statistical significance probably indicated microheterogeneity in inflammatory foci in the different samples (Figure 4A). We also used real-time RT-PCR to validate the microarray results of four genes up-regulated in CCC. All four genes (ANF, IL-7 receptor, HLA-DR, and IFN-γ receptor) were significantly up-regulated; IL-7 receptor and HLA-DR were selectively up-regulated among CCC samples (Figure 4B).The fold changes in RT-PCR were usually greater than those shown in microarray experiments for the same genes, as observed before by ourselves16 and others.29,30 Rajeevan and colleagues30 observed fold values at SYBR real-time PCR more than 10 times larger than those observed at the microarray experiment, and argued that this could be due to cross-hybridization in microarrays and a more specific detection in the PCR reaction.

Figure 4.

Real-time RT-PCR analysis of selected genes in CCC or DCM myocardium. A: Chemokine/chemokine receptor genes. B: Genes identified by microarray analysis. C: Analysis of ANF expression in fetal cardiomyocytes after 8 hours of stimulus with MCP-1, IFN-γ and their combination. M, culture medium. Cardiomyocyte culture performed as described.17 In A and B, results are expressed as average fold change from normal heart (column) and SD (error bar). Asterisks, P < 0.05 versus normal. Human (A, B) or murine (C) GAPDH was used as the reference mRNA species, and GAPDH Ct values did not change significantly between disease categories or in vitro stimulus.

To assess whether IFN-γ and the IFN-γ-inducible chemokine MCP-1, also expressed in CCC heart lesions (Figure 3A) and involved in cardiomyopathy31,32 can directly modulate expression of pathogenetically relevant genes in cardiomyocytes, we exposed fetal murine cardiomyocytes to IFN-γ and/or MCP-1, using ANF expression as an index of fetal/hypertrophic gene expression. Expression of ANF increased 15-fold in response to IFN-γ, and the combination of IFN-γ and MCP-1 increased ANF expression more than 400-fold compared to control values (Figure 4C).

Discussion

In this study of myocardial tissues from end-stage heart failure, CCC heart tissue displays a global gene expression profile notably distinct from that of DCM heart tissue, as observed from the clustering of samples according to disease type, the identification of disease-specific gene clusters (Figures 1 and 2), concordant with previous observations.15,16,24 We observed that the gene expression profiles of CCC and DCM showed some predictable similarities but differed dramatically in key areas. The hypertrophy/heart failure pattern (ie, up-regulation of expression of fetal contractile proteins and natriuretic peptides; sarcomere-building genes; myoglobin and tricarboxylic acid enzymes),20,33,34 is evident in both CCC and DCM; consistent with a hypertrophic and ventricular remodeling response to an intense ongoing stimulus. Together with the clustering analysis, the finding of an increased number of differentially expressed genes in CCC as compared to DCM myocardium may indicate that the gene expression profiles of CCC and DCM are qualitatively and quantitatively different. The finding of a significantly lower number of down-regulated than up-regulated genes in cDNA microarray analysis of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy has been previously observed by our own group and others.16,24 The fact that those reports used distinct data normalization and analysis (Lowess R on pooled samples,16 and Affymetrix GeneChip software24) suggests that the lower number of down-regulated genes in DCM observed in our study has a true biological basis, rather than being an artifact.

The observed overrepresentation of up-regulated genes in the cell defense category in CCC in comparison to DCM, or the proportion of defense genes in the gene array (Figure 2 and in Supplemental Material at http://ajp.amjpathol.org), is consistent with myocarditis, present in each of the tested CCC samples. These results are in line with the expression profiling experiments performed with T. cruzi-infected mice.13,14 The considerable proportion of IFN-γ-inducible genes found to be up-regulated specifically in CCC heart samples (Table 2) indicates significant signaling by IFN-γ, consistent with its prominent local production.6,7 Several such genes are not known to be expressed by inflammatory cells, suggesting the possibility that IFN-γ could directly modulate gene expression in cardiac cells. The finding that the SERCA-2 cardiac Ca++-ATPase gene, involved in calcium metabolism and heart failure and down-modulated in CCC heart tissue (Table 2), was found to be repressible by IFN-γ,27 further supports the idea that this cytokine may directly modulate cardiomyocyte genes involved in heart failure and the hypertrophic phenotype. IFN-γ-inducible chemokines also had increased expression in CCC when compared to DCM or normal heart samples using real-time RT-PCR (Figure 4B), providing further confirmation of IFN-γ signaling. Although previous studies have suggested that MCP-1 and other chemokines can contribute to heart disease,31,32 and the proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-α35 and IL-1β33 can induce cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, we have demonstrated that IFN-γ, alone or in combination with MCP-1, can by itself induce increased expression of ANF in fetal cardiomyocytes (Figure 4C). Our study provides direct evidence for the first time that IFN-γ, a key T-cell-derived cytokine, can modulate cardiomyocyte gene expression. The induction of the natriuretic peptides is a feature of hypertrophy in all mammalian species and is a prognostic indicator of clinical severity,34 and the demonstration that ANF is inducible by IFN-γ identifies the T-cell-dependent cytokine as a possible stimulus for cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. If this property of ANF inducibility by IFN-γ is indeed shared with the metabolically distinct adult cardiomyocytes, this could have an even more direct bearing on pathogenesis. The fact that CCC patients display an increased frequency of IFN-γ-producing T cells in peripheral blood7,11 may also contribute to the increased signaling in the heart.

We also noted that genes involved in lipid metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation, and the proton transfer chain are selectively up-regulated in CCC but not in DCM tissue, suggesting that the energy metabolism in CCC is distinct from the reported DCM pattern22 (Figures 2 and 3, and in Supplemental Material at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Our group has recently shown that protein levels of creatine kinase, a key enzyme in the generation of cytoplasmic ATP, are reduced in myocardial tissue of CCC but not DCM patients.36 The increase in oxidative phosphorylation and lipid metabolism observed in CCC samples (Figures 2 and 3, and in Supplemental Material at http://ajp.amjpathol.org) may be a compensatory mechanism for cytoplasmic ATP depletion, as observed in mice genetically deficient of creatine kinase.37 Interestingly, IFN-γ treatment of cardiomyocytes reduced expression of creatine kinase,27 inhibited oxidative metabolism,38 and reduced ATP levels,39 suggesting a possible link between IFN-γ signaling and energy metabolism changes observed in CCC. Moreover, expression profiling in hearts of mice infected by T. cruzi also showed diminished myocardial energetic metabolism and altered oxidative phosphorylation.13,14 Significantly, mice infected for 100 days showed morphological alterations in mitochondria and diminished expression of genes from the oxidative phosphorylation pathway, with a detectable reduction of OXPHOS-mediated mitochondrial ATP production.40

In conclusion, our results indicate that gene expression patterns are markedly different between the CCC and DCM samples tested, suggesting the differential involvement of disease pathways in their pathogenesis. Our data suggests, for the first time, that locally produced T-cell-dependent IFN-γ, MCP-1, and possibly other inflammatory cytokines may directly up-regulate the myocardial expression of ANF, a hypertrophy-related gene, in addition to inflammatory effector-mediated myocardial cell death. We postulate that this cytokine-induced gene modulation of myocardial gene expression may lead to the increased ventricular remodeling, morbidity, and mortality of CCC patients as compared to other cardiomyopathies. Although our results were obtained with myocardial samples from a small number of CCC patients, they shared a representative phenotype (significant myocarditis, hypertrophy, fibrosis) that is common to other end-stage CCC patients. It is likely that that the unique properties of the myocardium from CCC patients sharing these features may be due to their dramatically altered energy metabolism. Our study may also have a bearing on other situations of T-cell-dependent myocardial inflammation, such as allograft rejection or viral myocarditis. Further investigation, including the testing of larger CCC patient sets to confirm the present findings, may suggest therapeutic and diagnostic approaches based on molecular rather than clinical portraits of cardiomyopathy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Gustavo P. Garlet for qRT-PCR in cardiomyocyte experiments and Eliane Mairena and Daniel Fefer for providing technical assistance.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. C.C. Liew, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 77 Louis Pasteur Ave., NRB room 0630K, Boston, MA. E-mail: cliew@rics.bwh.harvard.edu.

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (grants 5RO1-HL5851603, 5P5O-HL5931603, and 5RO1-HL6166102 and HL66582-04 (cardiogenomics PGA) to P.D.A and MERIT award 5R37-HL3561016 to V.J.D.), the Brazilian National Research Council (CNPq 52053997.6), and São Paulo State Foundation for the Support of Science (FAPESP01/05566-5).

References

- WHO Expert Committee: Control of Chagas’ disease. World Health Org Tech Rep 2002, 905:i [Google Scholar]

- Bestetti RB, Muccillo G. Clinical course of Chagas’ heart disease: a comparison with dilated cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 1997;60:187–193. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(97)00083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli FM, De Siqueira SF, Moreira H, Fagundes A, Pedrosa A, Nishioka SD, Costa R, Scanavacca M, D’Avila A, Sosa E. Probability of occurrence of life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias in Chagas’ disease versus non-Chagas’ disease. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2000;23:1944–1946. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2000.tb07058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi ML, De Morais CF, Pereira Barreto AC, Lopes EA, Stolf N, Bellotti G, Pileggi F. The role of active myocarditis in the development of heart failure in chronic Chagas’ disease: a study based on endomyocardial biopsies. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:665–670. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960101113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai C, Matsumori A, Fujiwara H. Myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy. Annu Rev Med. 1987;38:221–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.38.020187.001253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis MM, Higuchi ML, Benvenuti LA, Aiello VD, Gutierrez PS, Bellotti G, Pileggi F. An in situ quantitative immunohistochemical study of cytokines and IL-2R+ in chronic human chagasic myocarditis: correlation with the presence of myocardial Trypanosoma cruzi antigens. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;83:165–172. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel LC, Rizzo LV, Ianni B, Albuquerque F, Bacal F, Carrara D, Bocchi EA, Teixeira HC, Mady C, Kalil J, Cunha-Neto E. Chronic Chagas’ disease cardiomyopathy patients display an increased IFN-gamma response to Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J Autoimmun. 2001;17:99–107. doi: 10.1006/jaut.2001.0523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis DD, Jones EM, Tostes S, Lopes ER, Chapadeiro E, Gazzinelli G, Colley DG, McCurley TL. Expression of major histocompatibility complex antigens and adhesion molecules in hearts of patients with chronic Chagas’ disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;49:192–200. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.49.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha-Neto E, Kalil J. Heart infiltrating and peripheral T cells in the pathogenesis of Chagas’ disease cardiomyopathy. Autoimmunity. 2001;34:187–192. doi: 10.3109/08916930109007383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira MM, Gazzinelli RT, Silva JS. Chemokines, inflammation and Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Trends Parasitol. 2002;18:262–265. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(02)02283-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes JA, Bahia-Oliveira LM, Rocha MO, Martins-Filho OA, Gazzinelli G, Correa-Oliveira R. Evidence that development of severe cardiomyopathy in human Chagas’ disease is due to a Th1-specific immune response. Infect Immun. 2003;71:1185–1193. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.3.1185-1193.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares MB, Silva-Mota KN, Lima RS, Bellintani MC, Pontes-de-Carvalho L, Ribeiro-dos-Santos R. Modulation of chagasic cardiomyopathy by interleukin-4: dissociation between inflammation and tissue parasitism. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:703–709. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61741-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Belbin TJ, Spray DC, Iacobas DA, Weiss LM, Kitsis RN, Wittner M, Jelicks LA, Scherer PE, Ding A, Tanowitz HB. Microarray analysis of changes in cehge expression in a murine model of chronic chagasic cardiomyopathy. Parasitol Res. 2003;91:187–196. doi: 10.1007/s00436-003-0937-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg N, Popov V, Papaconstantinou J. Profiling gene transcription reveals a deficiency of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in chagasic myocarditis development. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1638:106–120. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(03)00060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrans JD, Allen PD, Stamatiou D, Dzau VJ, Liew CC. Global gene expression profiling of end-stage dilated cardiomyopathy using a human cardiovascular-based cDNA microarray. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:2035–2043. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61153-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang JJ, Allen PD, Tseng GC, Lam CW, Fananapazir L, Dzau VJ, Liew CC. Microarray gene expression profiles in dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathic end-stage heart failure. Physiol Genom. 2002;10:31–44. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00122.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang DM, Dempsey AA, Wang RX, Rezvani M, Barrans JD, Dai KS, Wang HY, Ma H, Cukerman E, Liu YQ, Gu JR, Zhang JH, Tsui SK, Waye MM, Fung KP, Lee CY, Liew CC. A genome-based resource for molecular cardiovascular medicine: toward a compendium of cardiovascular genes. Circulation. 1997;96:4146–4203. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.12.4146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams MD, Kerlavage AR, Fleischmann RD, Fuldner RA, Bult CJ, Lee NH, Kirkness EF, Weinstock KG, Gocayne JD, White O. Initial assessment of human gene diversity and expression patterns based upon 83 million nucleotides of cDNA sequence. Nature. 1995;377:S3–S174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meirelles MNL. Interaction of Trypanosoma cruzi with heart muscle cells: ultrastructural and cytochemical analysis of endocytic vacuole formation and effect upon myogenesis in vitro. Eur J Cell Biol. 1986;41:198–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molkentin JD, Dorn GW., II Cytoplasmic signaling pathways that regulate cardiac hypertrophy. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63:391–426. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depre C, Hase M, Gaussin V, Zajac A, Wang L, Hittinger L, Ghaleh B, Yu X, Kudej RK, Wagner T, Sadoshima J, Vatner SF. H11 kinase is a novel mediator of myocardial hypertrophy in vivo. Circ Res. 2002;91:1007–1014. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000044380.54893.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal K, Moreno-Sanchez R. Heart metabolic disturbances in cardiovascular diseases. Arch Med Res. 2003;34:89–99. doi: 10.1016/S0188-4409(03)00004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Moravec CS, Sussman MA, DiPaola NR, Fu D, Hawthorn L, Mitchell CA, Young JB, Francis GS, McCarthy PM, Bond M. Decreased SLIM1 expression and increased gelsolin expression in failing human hearts measured by high-density oligonucleotide arrays. Circulation. 2000;102:3046–3052. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.25.3046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenman M, Chen YW, Le Cunff M, Lamirault G, Varró A, Hoffman E, Leger JJ. Transcriptomal analysis of failing and nonfailing human hearts. Physiol Genom. 2003;12:97–112. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00148.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moschella F, Maffei A, Catanzaro RP, Papadopoulos KP, Skerrett D, Hesdorffer CS, Harris PE. Transcript profiling of human dendritic cells maturation-induced under defined culture conditions: comparison of the effects of tumour necrosis factor alpha, soluble CD40 ligand trimer and interferon gamma. Br J Haematol. 2001;114:444–457. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrone L, Damore MA, Lee MB, Malone CS, Wall R. Genes expressed during the IFN gamma-induced maturation of pre-B cells. Mol Immunol. 2002;38:597–606. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(01)00097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardozo AK, Heimberg H, Heremans Y, Leeman R, Kutlu B, Kruhoffer M, Orntoft T, Eizirik DL. A comprehensive analysis of cytokine-induced and nuclear factor-kappa B-dependent genes in primary rat pancreatic beta-cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48879–48886. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108658200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardozo AK, Kruhoffer M, Leeman R, Orntoft T, Eizirik DL. Identification of novel cytokine-induced genes in pancreatic beta-cells by high-density oligonucleotide arrays. Diabetes. 2001;50:909–920. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.5.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurmbach E, Yuen T, Ebersole BJ, Sealfon SC. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor-coupled gene network organization. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47195–47201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108716200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajeevan MS, Vernon SD, Taysavang N, Unger ER. Validation of array-based gene expression profiles by real-time (kinetic) RT-PCR. J Mol Diagn. 2001;3:26–31. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60646-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolattukudy PE, Quach T, Bergese S, Breckenridge S, Hensley J, Altschuld R, Gordillo G, Klenotic S, Orosz C, Parker-Thornburg J. Myocarditis induced by targeted expression of the MCP-1 gene in murine cardiac muscle. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:101–111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aukrust P, Damas JK, Gullestad L, Froland SS. Chemokines in myocardial failure—pathogenic importance and potential therapeutic targets. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;124:343–345. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaub MC, Hefti MA, Harder BA, Eppenberger HM. Various hypertrophic stimuli induce distinct phenotypes in cardiomyocytes. J Mol Med. 1997;75:901–920. doi: 10.1007/s001090050182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter JJ, Chien KR. Signaling pathways for cardiac hypertrophy and failure. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1276–1283. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910213411706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama T, Nakano M, Bednarczyk JL, McIntyre BW, Entman M, Mann DL. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha provokes a hypertrophic growth response in adult cardiac myocytes. Circulation. 1997;95:1247–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.5.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira PC, Iwai LK, Kalil J, Cunha-Neto E. Differential protein expression profiles in hearts of chronic Chagas’ disease cardiomyopathy or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo. 2003;45(Suppl 13):84. [Google Scholar]

- de Groof AJ, Smeets B, Groot Koerkamp MJ, Mul AN, Janssen EE, Tabak HF, Wieringa B. Changes in mRNA expression profile underlie phenotypic adaptations in creatine kinase-deficient muscles. FEBS Lett. 2001;506:73–78. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02879-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luss H, Watkins SC, Freeswick PD, Imro AK, Nussler AK, Billiar TR, Simmons RL, del Nido PJ, McGowan FX., Jr Characterization of inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in endotoxemic rat cardiac myocytes in vivo and following cytokine exposure in vitro. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1995;27:2015–2029. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(95)90023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, McMillin JB, Bick R, Buja LM. Response of the neonatal rat cardiomyocyte in culture to energy depletion: effects of cytokines, nitric oxide, and heat shock proteins. Lab Invest. 1996;75:809–818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyatkina G, Bhatia V, Gerstner A, Papaconstantinou J, Garg N. Impaired mitochondrial respiratory chain and bioenergetics during chagasic cardiomyopathy development. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1689:162–173. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.