Abstract

Trefoil factor-1 (Tff1) expression is remarkably down-regulated in nearly all human gastric cancers. Therefore, we used the Tff1 knockout mouse model to detect molecular changes in preneoplastic gastric dysplasia. Oligonucleotide microarray gene expression analysis of gastric dysplasia of Tff1 −/− mice was compared to that of normal gastric mucosa of wild-type mice. The genes most overexpressed in Tff1−/− mice included claudin-7 (CLDN7), early growth response-1 (EGR1), and epithelial membrane protein-1 (EMP1). Quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction and immunohistochemistry showed that Cldn7 was overexpressed in all 10 Tff1−/− gastric dysplasia samples. Comparison with our serial analysis of gene expression database of human gastric cancer revealed similar deregulation in human gastric cancers. Quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction of human gastric adenocarcinoma samples indicated that, of these three genes, CLDN7 was the most frequently up-regulated gene. Using immunohistochemistry, both mouse and human gastric glands overexpressed Cldn7 in dysplastic but not surrounding normal glands. Cldn7 expression was observed in 30% of metaplasia, 80% of dysplasia, and 70% of gastric adenocarcinomas. Interestingly, 82% of human intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinomas expressed Cldn7 whereas diffuse-type gastric adenocarcinomas did not (P < 0.001). These results suggest that Cldn7 expression is an early event in gastric tumorigenesis that is maintained throughout tumor progression.

Gastric carcinoma is the second leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide accounting for ∼10% of newly diagnosed cancers.1,2 Gastric cancer is the fourth most common new cancer diagnosis in the world, accounting for an estimated 876,341 new cancer cases and 646,567 deaths worldwide in 2000.2 In human, it is rather rare to detect dysplastic lesions because these patients tend to be asymptomatic, and are only diagnosed when tumors already are present at an advanced stage.3 In the United States this is reflected in an overall 5-year survival rate of less than 20%.1 Thus, identification of early genetic changes in gastric tumorigenesis is a challenging task. Mouse models of human disease are useful to explore the molecular basis of a disease that is difficult to perform in humans. The trefoil factor-1 (Tff1) is strongly and specifically expressed in the epithelial cells within the upper part of the gastric pits, an area where cells undergo commitment to differentiation, to limit gland proliferation, and give rise to a functional secreting mucosa.4–6 We and others have reported that Tff1 expression is remarkably down-regulated in nearly all human gastric cancers.7,8 Recent reports support the notion that Tff1 may be a candidate tumor suppressor gene that may be involved in development and/or progression of human gastric cancers.6,7,9 The Tff1 knockout (−/−) mouse model was first reported in 1996 as a model for spontaneous development of intestinal-type gastric dysplasia and cancer, similar to human disease.10 Thus, the Tff1−/− mouse model provides a window to look into molecular alterations that are associated with precancerous lesions and understand the development of gastric cancers. Herein, we report gene expression profiling in dysplastic lesions of Tff1−/− mice as contrasted to normal mucosa and compare the results with our transcriptome database of human gastric cancer. This approach allowed us to discover and validate molecular changes that are associated with early gastric tumorigenesis.

Materials and Methods

Microarray Analysis of Mouse Tissue Samples

For global analysis, we have performed microarray analysis on four samples obtained from different mice, two tissue samples from dysplastic gastric lesions of two Tff1−/− mice and two normal gastric mucosal samples from Tff1 wild-type (WT) (+/+) mice. The Tff1−/− mice were first developed and described by Lefebvre and colleagues.10 All tissues were microdissected using laser capture microdissection (Pixcell laser capture microdissection apparatus; Arcturus Engineering, Mountain View, CA). All animal experiments were performed in accordance with University of Virginia institutional approval for animal care. Total cellular RNA from microdissected samples was prepared using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany); labeled cRNA was prepared and hybridized to oligonucleotide microarrays (GeneChip, Mouse Genome 430A 2.0 Array; Affymetrix Inc., Santa Clara, CA) that contains ∼14,000 well-characterized mouse genes. Scanned image files were analyzed with GENECHIP 3.1 (Affymetrix Inc.). To identify genes with elevated expression in tumors, the intensity values of each probe set were compared in all of the tumor and corresponding normal tissue samples and were then sorted by the magnitude of the fold change between the average intensity values of all dysplasia and normal tissue samples.

Serial Analyses of Gene Expression (SAGE)

High-quality total RNA (500 μg) was extracted using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) from four dissected gastric adenocarcinoma and two normal gastric mucosa pools, each pool consists of four normal gastric mucosal biopsy samples from normal individuals. The tumors selected for SAGE analysis were estimated to consist of more than 80% tumor cells. All normal samples had histologically normal mucosa confirmed on review of hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections. Importantly, histopathological examination confirmed that none of the normal samples had any areas of inflammation or necrosis. All samples were collected after consent in accordance with the Human Investigation Committee regulations at the University of Virginia. SAGE libraries were constructed using NlaIII as the anchoring enzyme and BsmFI as the tagging enzyme as described in SAGE protocol version 1.0e, June 23, 2000, which includes few modifications of standard protocol.11 A detailed protocol and schematic of the method is available (http://www.sagenet.org/protocol/index.htm). Two thousand clones were sequenced for each case by the Cancer Genome Anatomy Project. We used eSAGE 1.2a software to extract SAGE tags, remove duplicate ditags, tabulate tag contents, and link SAGE tags in the database to UniGene clusters using the recently reported ehm-Tag-mapping method.12,13 The resulting libraries’ tags were compared to UniGene cluster and to the SAGE tag reliable mapping database (http://www.sagenet.org/resources/genemaps.htm) and the statistical analyses were performed using the eSAGE software. We have earlier reported the results of two SAGE libraries (GSM757 and GSM784).14

Quantitative Real-Time Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

Gastric mucosa samples were dissected from gastric tissue of 13 mice at 5 months of age (seven Tff1−/− gastric dysplasia and six Tff1+/+ normal gastric mucosa tissue samples). In addition, 20 human gastric adenocarcinoma samples and 13 normal human gastric mucosa samples were dissected to obtain more than 70% sample purity. All tumors and normal gastric mucosal epithelial tissues were verified by us (H.F.F. and C.A.M.). The primary gastric adenocarcinoma used in this study consisted of a diverse panel of tissues representing all stages of development [tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stages I to IV], and histopathology (well differentiated to poorly differentiated; intestinal and diffuse type). RNA was purified from all samples using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen). Single-stranded cDNA was generated using an Advantage RT-for-PCR kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). qRT-PCR was performed using an iCycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with SYBR Green technology, and the threshold cycle numbers were calculated using iCycler software v3.0.15 Reactions were performed in triplicates and threshold cycle numbers were averaged. For validation of our microarray results, we selected CLDN7, EGR1, and EMP1. We designed gene-specific primers for mouse CLDN7, EGR1, EMP1, and β-actin and human CLDN7, EGR1, EMP1, and HPRT1. The primers used for qRT-PCR were obtained from GeneLink (Hawthorne, NY), and their sequences are available on request. The mouse results were normalized to β-actin and the human results were normalized to HPRT1, which had minimal variation in all normal and neoplastic samples that we tested. Fold-overexpression was calculated according to the formula 2(Rt − Et)/2(Rn − En) as described earlier15,16 where Rt is the threshold cycle number for the reference gene observed in the tumor, Et is the threshold cycle number for the experimental gene observed in the tumor, Rn is the threshold cycle number for the reference gene observed in the normal sample, and Rt is the threshold cycle number for the reference gene observed in the tumor sample. Rn and En values were an average for the corresponding normal samples that were analyzed. A single melt curve peak was observed for each sample used in the data analysis, thus confirming purity of all amplified products.

Western Blot Analysis

Primary dysplastic and normal mouse tissues were collected from Tff1−/− and Tff1+/+ mice, respectively. All tissues were collected in compliance with the University of Virginia institutional animal care and use committee protocol. Stomach tissues were immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. All tissues were dissected to obtain a minimum of 75% purity of the desired cell population (dysplastic or normal). Frozen tissues were suspended in 0.4 ml of TENN buffer (50 mmol/L Tris, pH 8.0, 5 mmol/L ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.2% Nonidet P-40, pH 8.0) containing a protease inhibitor mixture (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and disintegrated by homogenizer and sonication. Lysates were centrifuged twice at 14,000 rpm for 15 minutes, and supernatants were loaded onto 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels. Membranes were immunoblotted with the claudin-7 antibody C-15 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at 1:100 dilutions. β-Actin antibody AC-74 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used at 1:1000 dilutions for normalization of protein loading.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Immunohistochemical staining was performed using a Cldn7 (C-15) goat polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Cldn7 protein expression was evaluated by IHC on histological sections of stomachs of 11 Tff1−/− that developed dysplastic epithelial lesions. Additionally, 10 WT Tff1+/+ with normal gastric mucosa were included for comparison. All animal tissue samples were collected according to the University of Virginia institutional approval for animal care. In addition, Cldn7 was tested on human samples that comprised 11 normal gastric mucosa samples, 3 intestinal metaplasia samples, 10 gastric dysplasia samples, and a tissue microarray of 93 gastric adenocarcinoma. All human samples were collected from tissue archives of the Department of Pathology at University of Virginia and in accordance with our institutional human investigation committee-approved protocols. After the sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated, they were incubated with the antibody at a 1:200 dilution (0.05 μg/ml final concentration) for 1 hour at room temperature. Antibody binding was visualized using the avidin-biotin immunoperoxidase technique (Vectastain Elite ABC kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), with diaminobenzidine staining and hematoxylin counterstaining. The intensity of the immunoreactivity of the samples tested was scored as either 0 (no staining), 1 (weak), 2 (moderate), or 3 (strong) as demonstrated in Figure 5.

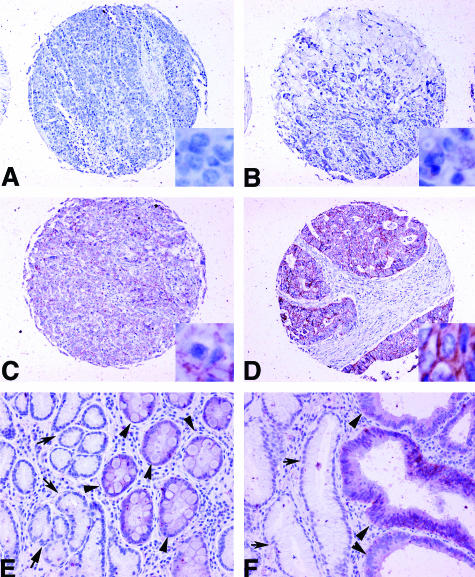

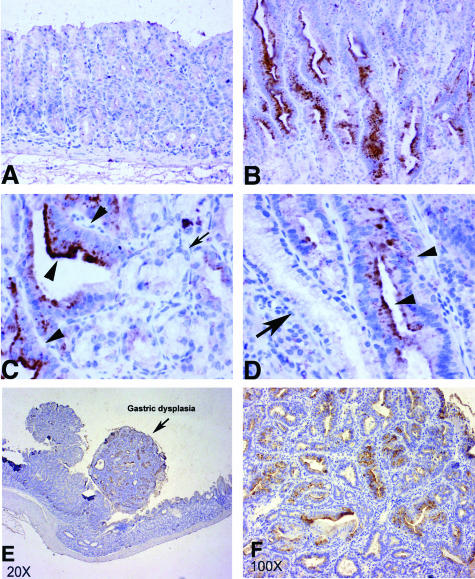

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical staining using claudin-7 antibody on tissue array of human gastric tissues. A: A gastric adenocarcinoma showing no staining. B: A gastric adenocarcinoma showing weak intensity staining (1+). C: A gastric adenocarcinoma showing moderate intensity staining (2+). D: A gastric adenocarcinoma showing strong intensity staining (3+). E: Metaplasia adjacent to normal gastric mucosa, showing 1+ staining. Arrows indicate the normal glands with no staining. Arrowheads indicate metaplastic glands. F: Dysplasia adjacent to nonneoplastic glands, showing 2+ staining in dysplastic glands and no staining in normal glands (arrows) and moderate to strong staining in dysplastic glands (arrowheads). Original magnifications: ×100 (A–D); ×200 (E, F); ×800 (insets in A–D).

Results

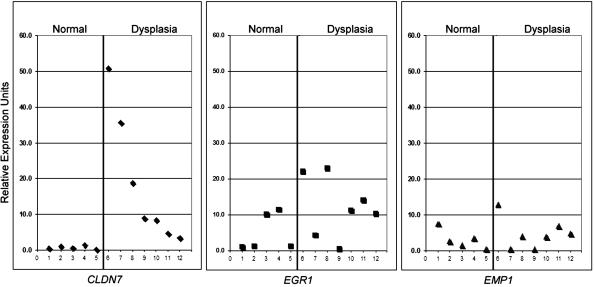

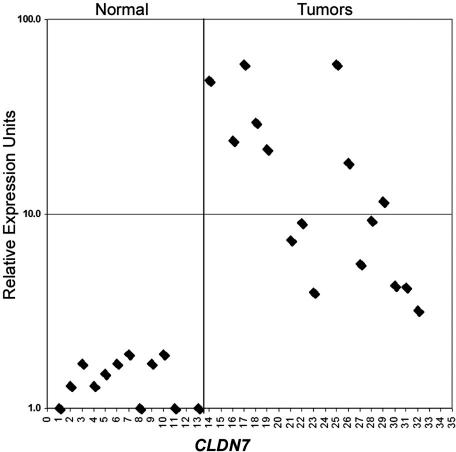

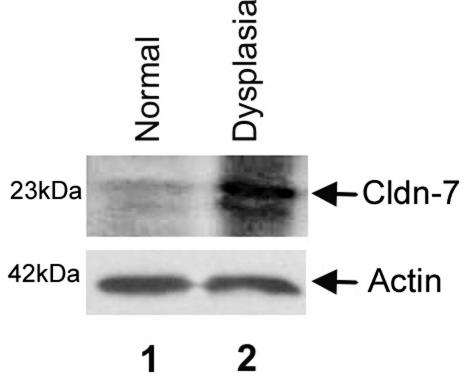

Our analysis of gene expression of gastric dysplasia lesions in the Tff1−/− mice as compared to WT Tff1+/+ with normal gastric mucosa, revealed overexpression of 41 genes (more than twofold) and seven genes showed the highest overexpression fold (>2.5-fold) (Table 1). A comparison of these seven genes to our SAGE human transcriptome database of gastric cancer allowed us to filter our results to CLDN7, EGR1, and EMP1 genes that were dysregulated in one or more of human gastric cancer SAGE libraries (Table 2). Thus, we were able to filter the mouse data set through the human data and come up with similarities that were maintained during the course of progression from dysplasia to cancer. Accordingly, these genes were selected for validation (CLDN7, EGR1, and EMP1) based on their frequency, expression levels, and similar trend in human gastric cancers. The qRT-PCR analysis indicated that CLDN7 is overexpressed in all Tff1−/− gastric dysplasia samples whereas EGR1 and EMP1 were less frequently overexpressed (Figure 1). Analysis of human gastric cancer samples (Table 2) revealed that CLDN7 was also the most frequently expressed gene (14 of 20) as compared to EGR1 (5 of 20) or EMP1 (6 of 20) (Figure 2) (data not shown for EGR1 and EMP1). Because of the high frequency of overexpression of CLDN7, we sought to confirm this novel finding that CLDN7 may be a potential molecular target for gastric dysplasia. The Western blot analysis using dysplastic and normal tissues dissected from Tff1−/− and Tff1+/+ mice revealed a robust and specific signal for Cldn7 antibody and confirmed the overexpression of cldn7 protein in gastric dysplasia (Figure 3). The IHC on tissue samples from the mice demonstrated absence of Cldn7 staining in normal gastric mucosal samples that we studied (n = 10) whereas it was moderately to strongly expressed in all dysplastic mice tissues (n = 11) showing specific cytoplasmic immunostaining (Figure 4). In each case the nonneoplastic gastric epithelium showed no or focal-weak staining (0 to 1+) for Cldn7, while the adjacent dysplastic epithelium showed moderate to strong staining (2 to 3+) (Figure 4).

Table 1.

Summary of the Seven Most Overexpressed Genes in the TFF1−/− Mouse Using Microarrays

| Accession ID | Gene name | Gene symbol | Fold overexpression |

|---|---|---|---|

| AB019436 | SAM pointed domain containing ets transcription factor | SPDEF | 3.2 |

| AF087825 | Claudin 7 | CLDN7 | 3.2 |

| AA882332 | Propionyl coenzyme A carboxylase, β polypeptide | PCCB | 3.0 |

| AF039663 | Prominin | PROM1 | 3.0 |

| X98471 | Epithelial membrane protein 1 | EMP1 | 3.0 |

| J04627 | Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase (NAD+-dependent) | MTHFD2 | 2.8 |

| M28845 | Early growth response 1 | EGR1 | 2.6 |

Forty-one genes were overexpressed (more than twofold). This table shows the seven most overexpressed genes in dysplastic gastric mucosa of TFF1 knockout mice as compared to normal gastric mucosa of TFF1 WT mice.

Table 2.

Expression of CLDN7, EGR1, and EMP1 in Human Gastric Cancer Using SAGE

| CLDN7 | EGR1 | EMP1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tag sequence | TATAGTCCTC | GGATATGTGG | TAATTTGCAT |

| Unigene ID | Hs.513915 | Hs.326035 | Hs.436298 |

| Normal SAGE library | |||

| GSM784 (25,302 tags) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| GSM14780 (26,635 tags) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Cancer SAGE library | |||

| GSM2385 (64,102 tags) | |||

| Tag count | 8 | 8 | 4 |

| Overexpression fold | 4.7 | 6.2 | 3.2 |

| P value | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.1 |

| GSM758 (70,433 tags) | |||

| Tag count | 10 | 5 | 15 |

| Overexpression fold | 5.4 | 3.6 | 10.6 |

| P value | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.01 |

| GSM757 (66,032 tags) | |||

| Tag count | 19 | 14 | 30 |

| Overexpression fold | 8.1 | 10.8 | 23 |

| P value | 0.015 | 0.01 | 0.0001 |

| GSM14760 (51,620 tags) | |||

| Tag count | 4 | 0 | 20 |

| Overexpression fold | 2.8 | 0 | 15 |

| P value | 0.2 | NA | 0.0001 |

Two normal (GSM784 and GSM14780) and four gastric cancer (GSM2385, GSM758, GSM757, GSM14760) SAGE libraries were produced. Two thousand clones were sequenced for each SAGE library by the Cancer Genome Anatomy Project (CGAP). The total number of sequenced SAGE tags was 304,142. The fold overexpression for each gene was calculated in each gastric cancer library as compared to normal libraries. The software converts values of 0 into 0.5 to allow for calculation of fold expression. P values ≤0.05 were considered significant.

Figure 1.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (iCycle, Bio-Rad) of mouse CLDN7 (left), EGR1 (middle), and EMP1 (right) on seven microdissected gastric dysplastic tissues of Tff1−/− and six normal gastric mucosa of Tff1+/+. The sample numbers are given in the horizontal axis. The average threshold cycle number for all normal samples was used as reference value. All results were normalized to the expression of β-actin in the same sample. Each sample was compared to six normal samples and there was less than 10% variation for all comparisons. The expression of CLDN7 was higher in all dysplastic tissue samples as compared to normal samples.

Figure 2.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR of human CLDN7 on 13 different normal mucosa samples of the stomach (left) and 20 gastric adenocarcinoma (right) samples. The sample number is given in the horizontal axis. For visualization, the relative expression for all samples is shown in a logarithmic scale. The average threshold cycle number for all normal samples was used as reference value. All results were normalized to the expression of HPRT1 in the same sample, which had minimal variation in all normal and neoplastic gastric samples that we tested. The SEM showed less than 10% variation for all comparisons.

Figure 3.

Western blot analysis of claudin-7 in normal and dysplastic stomach of the Tff1+/+ and Tff1−/− mice. Protein extracted from normal stomach (antrum) is loaded in lane 1 and protein extracted from the dysplastic lesion (antrum) is loaded in lane 2. Membranes were immunoblotted with the claudin-7 antibody C-15 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 1:100 dilutions (top) or β-actin antibody AC-74 (Sigma-Aldrich) at 1:1000 dilutions for normalization of protein loading (bottom). The normalization with β-actin (∼42 kd), as shown at the bottom, indicates equal protein loading. The dysplastic tissues show a robust signal for cldn7 (∼23 kd) and the normal tissue shows a very weak signal confirming that cldn7 is specifically overexpressed in gastric dysplasia of the Tff1−/− mice.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical staining using claudin-7 antibody on gastric tissues of four different Tff1−/− mice. A: Normal gastric mucosa shows no staining. B: A dysplastic tissue of the same mouse as in A showing moderate to strong immunostaining of dysplastic tissues. C: A dysplastic gland next to a normal gland in a second mouse showing increased staining in dysplasia and absent staining in normal glands (indicated by arrows). D: Dysplastic gland next to normal glands showing increased staining in dysplasia of a third different mouse. Arrows indicate normal glands and arrowheads indicate dysplastic glands. E: A low magnification of a dysplastic lesion indicated by arrows in a different mouse. Notice the nodular shape and moderate to strong staining. F: Higher magnification of the lesion shown in E, demonstrating intense staining of dysplastic glands. Original magnifications: ×200 (A, B); ×400 (C, D); ×20 (E); ×100 (F).

IHC staining of Cldn7 on human gastric tissue samples showed no staining in 10 of 10 normal mucosa of the stomach for Cldn7, but weak staining (1+) in gastric mucosa with metaplasia (three of three). Eight of ten dysplastic lesions from different patients had moderate to strong IHC staining. Interestingly, staining of 93 human gastric adenocarcinomas showed that Cldn7 overexpression is specifically observed in 61 of 74 of intestinal-type (82%) but only in 4 of 19 of diffuse-type tumors (21%) (P < 0.01). Moreover, moderate to strong immunostaining was detected in 55% of intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinomas but in none of the diffuse-type tumors (P < 0.001) (Table 4, Figure 5). There was no association with tumor stage or grade. Moreover, in all gastric adenocarcinomas, the surrounding nonneoplastic tissues that were available in more than one-third of the samples did not show staining for Cldn7 (Figure 5).

Table 4.

Summary of Immunohistochemical Staining Using Claudin-7 on 117 Human Gastric Samples

| IHC intensity

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | 0 (none) | 1 ( weak) | 2 (moderate) | 3 (strong) |

| Normal gastric mucosa (n = 11) | 11 (100%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Intestinal metaplasia (n = 3) | 0 | 3 (100%) | 0 | 0 |

| Gastric dysplasia (n = 10) | 2 (20%) | 5 (50%) | 3 (30%) | 0 |

| Diffuse-type gastric adenocarcinoma (n = 19) | 15 (79%) | 4 (21%) | 0 | 0 |

| Intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinoma (n = 74) | 13 (18%) | 22 (30%) | 24 (32%) | 15 (20%) |

In all gastric adenocarcinoma samples, the surrounding nonneoplastic tissues, when available, were negative for claudin-7. A positive IHC staining score correlates with gastric dysplasia and adenocarcinoma (P < 0.01). IHC staining intensity 2 to 3 correlated with intestinal and not diffuse gastric adenocarcinoma (P < 0.001).

Discussion

Animals provide a unique opportunity to study human disease and perform analysis in ways that are difficult to conduct in humans. Herein, we have used the Tff1−/− mouse as a model to identify early molecular events in gastric tumorigenesis. Our gene expression microarray analysis of dysplastic lesions of the Tff1−/− mice has revealed a number of dysregulated genes. Of the seven most overexpressed genes in mouse gastric dysplasia, CLDN7, EGR1, and EMP1 were found to be similarly overexpressed in our SAGE libraries of human gastric cancer. The qRT-PCR confirmed that CLDN7 is up-regulated in all mouse tissues of gastric dysplasia and was frequently up-regulated in 14 of 20 human gastric adenocarcinomas. Using IHC, Cldn7 was specifically expressed in dysplastic tissues of Tff1−/− mice but not in normal surrounding tissues or in normal gastric tissues from Tff1+/+ mouse controls. This finding raised the possibility that CLDN7 might be a candidate gene for early gastric tumorigenesis. This observation is also interesting because human CLDN7 is located at chromosome 17 (17p13), which has frequent alterations in DNA copy numbers in gastric cancer.17,18

Our studies demonstrate that CLDN7 up-regulation in gastric neoplasia is conserved between the mouse model and human disease. Using clinical samples, Cldn7 IHC staining was not detected in any normal tissues, whereas specific cytoplasmic staining with apical patterns was seen in intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and adenocarcinomas. Interestingly, Cldn7 was weak in metaplasia, and became moderate to strong in dysplasia, whereas most of the intestinal-type adenocarcinoma showed strong expression. We have found that Cldn7 expression correlates with intestinal-type (P < 0.01), but not with tumor site, stage, or grade. This finding is most likely attributed to the differences in biological properties of intestinal versus diffuse histological subtypes. The fact that Cldn7 is expressed in early stages of gastric tumorigenesis and remains expressed in advanced intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinomas raises a potential biological role of Cldn7 in the tumorigenesis cascade.

Adhesion between neighboring epithelial cells is a crucial and tightly controlled process. In epithelial cells, specialized structures such as tight junctions and adherens junctions (also called the zonula adherens) are responsible for the establishment of contacts between neighboring cells.19,20 Tight junctions contain the transmembrane proteins occludin and the claudins, which are connected to the cytoskeleton via a network of proteins such as zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1).20 Claudins comprise a multigene family, and each member of ∼23 kd bears four transmembrane domains. To date, more than 20 members of this gene family have been identified.21,22 Claudins are exclusively responsible for the formation of tight junction strands and are connected with the actin cytoskeleton mediated by ZO-1.21–23 Tight junctions in epithelial cells act as cell-cell adhesion structures and govern paracellular permeability. They have two functions, the barrier (or gate) function and the fence function. The barrier function of tight junctions regulates the passage of ions, water, and various macromolecules, even of cancer cells, through paracellular spaces. Epithelial cells, and the tight junctions between them, form a polarized barrier between luminal and serosal fluid compartments and segregate luminal growth factors from their basal-lateral receptors. This property may promote cancer formation in premalignant epithelial tissues in which the tight junctions have become chronically leaky to growth factors.24 On the other hand, the fence function maintains cell polarity. This function is deeply involved in cancer cell biology. The establishment and stability of both adherens junctions and tight junctions are tightly regulated by several factors such as growth factors, cytokines, and hormones25 and can also have a significant impact on tumor development and metastasis.19,22,23

Although the present literature about claudins in cancer remains scarce; recent studies have suggested a potential role for claudins in cancer development and progression. In ovarian cancer, studies have shown claudins as potential molecular targets where claudin-3 and claudin-4 are frequently overexpressed.26,27 Cldn4 protein overexpression was observed in primary and metastatic pancreatic cancer. The Cldn4 overexpression within pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia, the precursor lesion of pancreatic cancer, suggests a potential benefit of imaging claudin-4 before the development of an invasive carcinoma.28,29 Moreover, claudin-4 was observed in 73% of 22 invasive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms but in none of 16 noninvasive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (P < 0.0001).30 This notion is in agreement with our findings that Cldn7 is overexpressed in gastric dysplasia and adenocarcinomas but not in surrounding nonneoplastic tissues. Interestingly, a member of the claudin protein family, claudin-1, is involved in the β-catenin-TCF/LEF signaling pathway, and that increased expression of claudin-1 may have some role in colorectal tumorigenesis.31 Cldn7 is responsive to androgen stimulation in the LNCaP prostate cancer cell line and can regulate the expression of prostate-specific antigen.32 Recently, it was reported that Cldn7 is unlike other claudins, has both structural and regulatory functions and may be related to cell differentiation.32 Thus, our results together with the growing data about claudins strongly suggest that some members of this large protein family are involved in epithelial tumorigenesis and may have an early diagnostic and or prognostic clinical value.

In this study, we have used the Tff1−/− mouse model to explore genetic changes related in premalignant lesions and have discovered molecular alterations of early gastric tumorigenesis. We have confirmed overexpression of Cldn7 at both the transcript and protein levels and showed specific overexpression of Cldn7 in the murine dysplastic gastric epithelial cells, but not in the surrounding normal epithelial cells. Moreover, we have shown that Cldn7, a member of tight junction proteins, is indeed overexpressed in human gastric dysplasia and adenocarcinoma but not in the surrounding nonneoplastic epithelial cells. The precise mechanism behind overex-pression of Cldn7 and their biological role in gastric tumorigenesis will be the subject of future studies.

Table 3.

Histopathological Data of Primary Gastric Adenocarcinomas for qRT-PCR

| Sample | Sex | Age | Site | Histology | TNM | Stage | Grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GS1 | M | 60 | GEJ | Intestinal | T3N1M0 | III | MD |

| GS2 | F | 66 | Body | Intestinal | T2N1M0 | II | PD |

| GS3 | F | 78 | Body | Intestinal | T4N1M0 | IV | PD |

| GS4 | M | 58 | GEJ | Intestinal | T4N0M0 | III | MD |

| GS5 | M | 72 | Antrum | Mixed | T3N1M0 | IIIA | PD |

| GS6 | M | 56 | Antrum | Diffuse | T3N2M0 | IIIB | PD |

| GS7 | M | 58 | GEJ | Intestinal | T4N0M0 | III | MD |

| GS8 | M | 70 | GEJ | Intestinal | T3N1M1a | IV | PD |

| GS9 | M | 52 | Body | Intestinal | T3N2M1 | IV | PD |

| GS10 | F | 70 | Antrum | Diffuse | T1N1M0 | IB | PD |

| GS11 | M | 46 | Antrum | Intestinal | T3N1M0 | IIIA | PD |

| GS12 | F | 64 | Body | Intestinal | T4N0M0 | IIIA | PD |

| GS13 | M | 72 | Antrum | Mixed | T3N1M0 | IIIA | PD |

| GS14 | F | 54 | GEJ | Intestinal | T3N1M0 | III | PD |

| GS15 | M | 84 | Antrum | Diffuse | T2N1M0 | II | PD |

| GS16 | M | 60 | GEJ | Intestinal | T3N1M0 | III | PD |

| GS17 | F | 68 | Body | Intestinal | T2N0M0 | IB | MD |

| GS18 | F | 68 | Body | Intestinal | T2N0M0 | IB | MD |

| GS19 | M | 60 | GEJ | Intestinal | T3N1M0 | III | MD |

| GS20 | M | 70 | GEJ | Intestinal | T3N1M1a | IV | PD |

M, male; F, female; GEJ, gastroesophageal junction; PD, poorly differentiated; MD, moderately differentiated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Garrett Hampton (Genomics Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation) for his excellent assistance and the Cancer Genome Anatomy Project and Dr. Gregory Riggins for their excellent support in sequencing the SAGE libraries.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Wa’el El-Rifai, M.D., Ph.D., the Digestive Health Center of Excellence, University of Virginia Health System, P.O. Box 800708, Charlottesville, VA 22908-0708. E-mail: elrifai@virginia.edu.

Supported by the National Cancer Institute (CA93999 to W.E.-R.) and the Cancer Center at University of Virginia.

References

- Roder DM. The epidemiology of gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2002;5(Suppl 1):5–11. doi: 10.1007/s10120-002-0203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Estimating the world cancer burden: Globocan 2000. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:153–156. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohenberger P, Gretschel S. Gastric cancer. Lancet. 2003;362:305–315. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13975-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirikoshi H, Katoh M. Expression of TFF1, TFF2 and TFF3 in gastric cancer. Int J Oncol. 2002;21:655–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh M. Trefoil factors and human gastric cancer. Int J Mol Med. 2003;12:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossenmeyer-Pourie C, Kannan R, Ribieras S, Wendling C, Stoll I, Thim L, Tomasetto C, Rio MC. The trefoil factor 1 participates in gastrointestinal cell differentiation by delaying G1-S phase transition and reducing apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:761–770. doi: 10.1083/jcb200108056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho R, Kayademir T, Soares P, Canedo P, Sousa S, Oliveira C, Leistenschneider P, Seruca R, Gott P, Blin N, Carneiro F, Machado JC. Loss of heterozygosity and promoter methylation, but not mutation, may underlie loss of TFF1 in gastric carcinoma. Lab Invest. 2002;82:1319–1326. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000029205.76632.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckler AD, Roche JK, Harper JC, Petroni G, Frierson HF, Jr, Moskaluk CA, El-Rifai W, Powell SM. Decreased abundance of trefoil factor 1 transcript in the majority of gastric carcinomas. Cancer. 2003;98:2184–2191. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calnan DP, Westley BR, May FE, Floyd DN, Marchbank T, Playford RJ. The trefoil peptide TFF1 inhibits the growth of the human gastric adenocarcinoma cell line AGS. J Pathol. 1999;188:312–317. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199907)188:3<312::AID-PATH360>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre O, Chenard M-P, Masson R, Linares J, Dierich A, LeMeur M, Wendling C, Tomasetto C, Chambon P, Rio M-C. Gastric mucosa abnormalities and tumorigenesis in mice lacking the pS2 trefoil protein. Science. 1996;274:259–262. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5285.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velculescu VE, Zhang L, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Serial analysis of gene expression. Science. 1995;270:484–487. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulies EH, Kardia SL, Innis JW. A comparative molecular analysis of developing mouse forelimbs and hindlimbs using serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE). Genome Res. 2001;11:1686–1698. doi: 10.1101/gr.192601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulies EH, Innis JW. eSAGE: managing and analysing data generated with serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE). Bioinformatics. 2000;16:650–651. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.7.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Rifai W, Moskaluk CA, Abdrabbo M, Harper JC, Yoshida C, Riggins G, Frierson HF, Jr, Powell SM. Gastric cancers overexpress S100A calcium binding proteins. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6823–6826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckhaults P, Rago C, St. Croix B, Romans KE, Saha S, Zhang L, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Secreted and cell surface genes expressed in benign and malignant colorectal tumors. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6996–7001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Rifai W, Smith MF, Jr, Li G, Beckler A, Carl VS, Montgomery E, Knuutila S, Moskaluk CA, Frierson HF, Jr, Powell SM. Gastric cancers overexpress DARPP-32 and a novel isoform, t-DARPP. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4061–4064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Rifai W, Frierson HJ, Moskaluk C, Harper J, Petroni G, Bissonette E, Knuutila S, Powell S. Genetic differences between adenocarcinomas arising in Barrett’s esophagus and gastric mucosa. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:592–598. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.27215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varis A, Wolf M, Monni O, Vakkari ML, Kokkola A, Moskaluk C, Frierson H, Jr, Powell SM, Knuutila S, Kallioniemi A, El-Rifai W. Targets of gene amplification and overexpression at 17q in gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2625–2629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollande F, Lee DJ, Choquet A, Roche S, Baldwin GS. Adherens junctions and tight junctions are regulated via different pathways by progastrin in epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1187–1197. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukita S, Furuse M, Itoh M. Multifunctional strands in tight junctions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:285–293. doi: 10.1038/35067088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukita S, Furuse M. The structure and function of claudins, cell adhesion molecules at tight junctions. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2000;915:129–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepass U. Claudin complexities at the apical junctional complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:595–597. doi: 10.1038/ncb0703-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada N, Murata M, Kikuchi K, Osanai M, Tobioka H, Kojima T, Chiba H. Tight junctions and human diseases. Med Electron Microsc. 2003;36:147–156. doi: 10.1007/s00795-003-0219-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullin JM. Epithelial barriers, compartmentation, and cancer. Sci STKE. 2004;216:2. doi: 10.1126/stke.2162004pe2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer B, Valles AM, Edme N. Induction and regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60:1091–1099. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu KH, Patterson AP, Wang L, Marquez RT, Atkinson EN, Baggerly KA, Ramoth LR, Rosen DG, Liu J, Hellstrom I, Smith D, Hartmann L, Fishman D, Berchuck A, Schmandt R, Whitaker R, Gershenson DM, Mills GB, Bast RC., Jr Selection of potential markers for epithelial ovarian cancer with gene expression arrays and recursive descent partition analysis. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:3291–3300. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangel LB, Agarwal R, D’Souza T, Pizer ES, Alo PL, Lancaster WD, Gregoire L, Schwartz DR, Cho KR, Morin PJ. Tight junction proteins claudin-3 and claudin-4 are frequently overexpressed in ovarian cancer but not in ovarian cystadenomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2567–2575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terris B, Blaveri E, Crnogorac-Jurcevic T, Jones M, Missiaglia E, Ruszniewski P, Sauvanet A, Lemoine NR. Characterization of gene expression profiles in intraductal papillary-mucinous tumors of the pancreas. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1745–1754. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61121-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols LS, Ashfaq R, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA. Claudin 4 protein expression in primary and metastatic pancreatic cancer: support for use as a therapeutic target. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:226–230. doi: 10.1309/K144-PHVD-DUPD-D401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato N, Fukushima N, Maitra A, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, van Heek NT, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, Hruban RH, Goggins M. Gene expression profiling identifies genes associated with invasive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:903–914. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63178-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa N, Furuse M, Tsukita S, Niikawa N, Nakamura Y, Furukawa Y. Involvement of claudin-1 in the beta-catenin/Tcf signaling pathway and its frequent upregulation in human colorectal cancers. Oncol Res. 2000;12:469–476. doi: 10.3727/096504001108747477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng JY, Yu D, Foroohar M, Ko E, Chan J, Kim N, Chiu R, Pang S. Regulation of the expression of the prostate-specific antigen by claudin-7. J Membr Biol. 2003;194:187–197. doi: 10.1007/s00232-003-2038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]