Abstract

The physiology and pathophysiology of the network of interstitial cells of Cajal associated with the deep muscular plexus (ICC-DMP) of the small intestine are still poorly understood. The objectives of the present study were to evaluate the effects of inflammation associated with Trichinella spiralis infection on the ICC-DMP and to correlate loss of function with structural changes in these cells and associated structures. We used immunohistochemistry, electron microscopy, and assessment of distention-inducing electrophysiological parameters in vitro. Damage to ICC-DMP was associated with a loss of distention-induced patterns of electrical activity normally associated with distention-induced peristalsis. Consistently, the timing of recovery of ICC-DMP paralleled the timing of recovery of the distention-induced activity. Nerve varicosities associated with ICC-DMP including cholinergic nerves, assessed by immunoelectron microscopy and whole mount double labeling, paralleled injury to ICC-DMP thus contributing to impaired excitatory innervation of smooth muscle cells. Major additional changes included a remodeling of the inner circular muscle layer, which may affect long-term sensitivity to distention after infection. In conclusion, transient injury to ICC-DMP in response to T. spiralis infection is severe and associated with a complete lack of distention-induced burst-type muscle activity.

Interstitial cells of Cajal associated with the deep muscular plexus (ICC-DMP) of the small intestine, which lies between the outer and the inner subdivisions of the circular muscle layer, have been ultrastructurally characterized in several animal species.1–4 These ICC form a network associated with the outer circular muscle cells through gap junctions5 and have close association with the nerve varicosities of the DMP including nerve varicosities of cholinergic and nitrergic nerves.6,7 Related to their function, ICC-DMP are the least studied ICC subtype, although they were described more than a century ago by Cajal.8 Cajal associated these ICC with a nerve plexus he named “plexus muscularis profundus,” now referred to as the “deep muscular plexus.” It is sometimes assumed that the role of ICC-DMP in the small intestine is similar to that of the intramuscular ICC (ICC-IM) in the stomach because there are no ICC-IM in the (mouse) small intestine. ICC-IM are proposed to be involved in neurotransmission based primarily on studies using mutant mice that lack this ICC subtype.9 The function of ICC-DMP is more difficult to study because no mutant model is available that specifically lacks ICC-DMP. ICC-DMP might play a secondary role in pacemaker activity.10 ICC-DMP have been proposed to function as stretch receptors, possibly together with the inner circular muscle layer and DMP varicosities, mainly based on structural studies.11,12 ICC-DMP form an uninterrupted network distributed over the whole intestinal length, from duodenum up to the ileocecal valve. In W/Wv mutant mice that lack a normal c-kit receptor, ICC-AP [xx] are absent but ICC-DMP are normal.13 Interestingly, in these animals, although the primary pacemaking activity is lost, distention can evoke characteristic burst-type electrical and mechanical activities and within such bursts of activity, peristalsis occurs that appears to be driven by slow wave-like activity.14–16 Hence, the ICC-DMP might be involved in generating the slow wave-like activity in response to the distention stimulus. Because the Trichinella spiralis model of inflammation had given us insight into relationships between injury and function of ICC-AP17 we decided to apply the same model to obtain a better understanding of functional consequences of injury to ICC-DMP. We set out to test the hypothesis that severe injury to ICC-DMP might affect distention-induced peristalsis. In addition, attention was given to cholinergic nerves because of their critical participation in distention-induced motor activity.18 The present study demonstrates that ICC-DMP are severely affected by a T. spiralis infection and provides evidence that this is associated with a complete loss of distention-induced generation of the electrical activities underlying distention-induced peristalsis.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Specific pathogen-free, male, 6 to 8 weeks old, C57BL/6 mice (Taconic, Germantown, NY) maintained in sterilized filtered cages were inoculated with 375 to 500 T. spiralis larvae using the procedures previously described by Castro and Fairbairn19 and modified by Vermillion and Collins.20 Animals were sacrificed at 2, 3, 8, 10, 15, 23, 40, 60, and 90 days after infection. Both control and infected animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. All of the experiments were approved by the McMaster University Animal Care Committee and the Canadian Council on Animal Care.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Electron microscopy was performed on tissue from both noninfected control mice and mice from 2 to 60 days after infection. Under terminal anesthesia with Fluothane (Ayerst, Montreal, Canada), a fixative solution containing 2% glutaraldehyde, 0.075 mol/L sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4, 4.5% sucrose, and 1 mmol/L CaCl2, was gently injected into the peritoneal cavity as well as the lumen of the proximal 10 cm of small intestine already tied at both ends. After 5 minutes of initial fixation, the proximal 8-cm segment of jejunum beginning 1 cm distal to the pylorus, was removed, opened lengthwise, and placed in the same fixative for an additional 2 hours at room temperature. After fixation, the tissues were cut into 2 × 5 mm circular and longitudinal strips, washed overnight in 0.1 mol/L sodium cacodylate buffer, containing 6% sucrose and 1.24 mmol/L CaCl2 (pH 7.4) at 4°C, postfixed with 1% OsO4 in 0.05 mol/L sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) at room temperature for 90 minutes, stained with saturated uranyl acetate for 60 minutes at room temperature, dehydrated in graded ethanol and propylene oxide, and embedded in Spurr. Tissue strips were oriented in molds to cut the circular muscle layer in either the cross or longitudinal direction. To locate suitable areas, 3-μm-thick sections were cut and stained with 2% toluidine blue. After the examination of the toluidine blue-stained sections, ultrathin sections of the selected areas were obtained with the LKB NOVA ultramicrotome using a diamond knife, mounted on 200-mesh grids, and stained with lead citrate or with an alcoholic solution of uranyl acetate, followed by a solution of concentrated bismuth subnitrate. The grids were examined under either a JEOL-1200 EX Biosystem or JEOL 1010 electron microscopes at 80 kV and photographed.

Double-Immunohistochemical Labeling of c-Kit and Vesicular Acetylcholine Transporter (VAChT)

Whole mounts were made from jejunum musculature with mucosa and submucosa removed of both control and T. spiralis-infected mice (10, 30, and 60 days after infection). All whole mount preparations were fixed in ice-cold acetone at 4°C for 10 minutes. After fixation, preparations were incubated with 1% bovine serum albumin for 1 hour to reduce the nonspecific staining before addition of primary antibodies. For double-labeling immunohistochemistry, tissues were incubated in each of the following primary antibodies for 48 hours at 4°C in a sequential manner. The first incubation was performed with rat monoclonal anti-c-Kit (ACK2, 1:200; Life Technologies, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD; currently ACK4 1:200 from Cederlane, Canada) The second one was with polyclonal rabbit anti-VAChT (1:100; Chemicon Inc., Temecula, CA). For the secondary antibodies, fluorescein isothiocyanate-coupled rabbit anti-rat IgG (1:100) was used to detect c-Kit labeling and Texas Red-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:100) to detect VAChT labeling. All of the secondary antibodies were purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA) with the incubation time of 1 hour at room temperature. All of the antisera were diluted with 0.3% Triton X-100 in 0.05 mol/L phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). Control tissues were prepared by omitting primary antibodies from the incubation solution. Tissues were examined with a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 510, Germany) with an excitation wavelength appropriate for fluorescein isothiocyanate (494 nm) and Texas Red (595 nm). Final images were constructed with Carl Zeiss software.

Immunoelectron Microscopy for VAChT

Tissues from both control and T. spiralis-infected mice (10, 30, and 60 days after infection) were studied. Whole mount tissues were prepared in the same way as for immunohistochemistry and fixed by immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde, 0.1% glutaraldehyde, and 0.2% picric acid in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer (PB, pH 7.4) for 1 hour at room temperature. After a brief rinse in 0.1 mol/L PB, tissue was washed vigorously at room temperature in several changes of 50% ethanol until the picric acid staining of the tissue had disappeared (∼20 minutes). The tissue was then washed in 0.1 mol/L PB and incubated in 0.1% NaBH3CN (Aldrich Chemical Co., Milwaukee, WI) in 0.1 mol/L PB for 30 minutes at room temperature. After washing in PB several times, nonspecific binding blocking was performed with 1% bovine serum albumin for 1 hour at room temperature. Tissues were then incubated with the same VAChT primary antibody as that for immunohistochemistry with the same time and dilution. On the third day, after washing in PBS several times, biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG, ABC reagent (with Vectastain ABC kit, Vector Laboratories) and peroxidase substrate (0.05% 3,3′ diaminobenzidine plus 0.01% H2O2 in 0.05 mol/L Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.6) were used for the subsequent immunoreactions. All of the antisera for immunoelectron microscopy were diluted with 0.05 mol/L PBS (without Triton X-100, pH 7.4). Tissues were continuously checked under the light microscope for suitable reaction, before being postfixed, block-stained, dehydrated, embedded, and grid-stained with lead citrate for conventional electron microscope examination.

Quantification of c-Kit and VAChT Immunoreactivities

For quantitative evaluation of c-Kit-positive cells and VAChT-positive nerve fibers at the level of DMP, pictures were taken with the confocal microscope in the whole mount tissues and 50 areas were selected from five cases and scanned at the level of the DMP. The whole mount preparations with known thickness were chosen from control, and 10-, 30-, and 60-day, respectively, animals after infection. Quantification of Kit and VAChT positivity was performed using the KS400 program (Zeiss, Germany). Kit- and VAChT-immunopositive reactions were identified and highlighted using density slicing on color scale images. The area of immunopositive cells on each scanning picture was measured and the volume of positive cells/varicosities at the level of the DMP on whole mount musculature (composed of different scanning pictures with total thickness of 3 to 5 μm) was calculated. Due to the known scanning depth of each whole mount preparation, the data can be expressed as percentage of total volume of the tissues (positive cell volume/total volume). The Triton X-100 allowed full penetration of antibodies into the DMP area. Slight variations in staining intensity were not a problem for quantification. After elimination of background staining both cells that stained intense and somewhat weaker were allowed to be incorporated in the computer analysis.

Quantification of Ultrastructural Features of ICC-DMP and the Inner Circular Muscle Layer

The coated vesicles located at the level of the Golgi apparatus plus those distributed along the ICC-DMP periphery were counted in controls and in mice at 2 to 15 days and 40 to 60 days after infection (two animals each group). Results are expressed as mean number of coated vesicles per ICC profile. To evaluate the caveolae number in the smooth muscle cells of the inner circular muscle layer, the smooth muscle cell perimeters, expressed in μm, were measured in 50 smooth muscle cell profiles of controls, in 57 mice 2 days and after infection, and in 70 animals 40 to 60 days after infection (two animals each group). Each micrograph had the same enlargement and the smooth muscle cells were cross-sectioned. Caveolae were counted in the same micrographs as above. The total areas expressed in μm2 occupied by the inner circular muscle layer, the smooth muscle cells of this layer, and the intercellular stroma, were measured in controls (11 micrographs), and in 2 (10 micrographs), 23 (10 micrographs), 40 (12 micrographs), and 60 (10 micrographs) days in animals after infection (two animals each group). Each micrograph had the same enlargement and the smooth muscle cells were cross-sectioned. The measurements were done by using Scion Image for Windows (Scion Image Corp., Bethesda, MD). Statistical analysis was performed by means of Student’s t-test. A probability value of less than 0.05 was regarded as significant. The results were expressed as the mean values ± SEM.

Mechanical and Electrophysiological Studies on Stretch-Induced Peristalsis

Both control and infected male mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Infected mice were inoculated with T. spiralis at day 1. The distention-induced motor patterns were determined on days 10, 30, 60, and 80 after infection. The small intestine was exposed by a mid-line abdominal incision. The intestine was placed in a continuously oxygenated (95% O2 and 5% CO2) Krebs solution (pH 7.3 to 7.4). A 6-cm segment was taken 2 cm distal of the pyloric sphincter. The segment was flushed gently with Krebs solution to remove luminal contents. The segment was placed in a 60-ml organ bath filled with continuously oxygenated (95% O2 and 5% CO2) Krebs solution at 37°C, pH 7.3 to 7.4. The composition of the Krebs solution was (in mmol/L): 120.3 NaCl, 5.9 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 20.0 NaHCO3, 1.2 NaH2PO4, and 11.5 glucose.

The oral part was attached to a pressure column, a large Krebs-filled beaker that allowed for the maintenance of constant pressure. The distal part was attached to an open vertical tube that did not allow outflow of contents. The lumen of the segment was filled with Krebs solution. The pressure within the segment was kept constant. The electrical pattern and luminal pressure were measured. The pressure within the segment was increased by increasing the level in the Krebs-filled beaker gradually to 5 cm. The intraluminal pressure was measured at two points with two Krebs solution-filled plastic open end tubes whose openings were located 3 and 5 cm from the oral end of the segment. Three suction electrodes attached to the serosal side of the segment measured the electrical activity in the segment. Electrical activity is measured from both circular and longitudinal muscle because of the small diameter of the mouse small intestine musculature. Electrical activities of the circular and longitudinal muscle are similar21 in contrast to those of the colonic muscle layers.22 The ground and recording electrodes were silver chloride-coated silver wires 0.06 mm in diameter. The recording electrodes were insulated by placing them in an open-ended flexible plastic tubing of 0.2-mm inner diameter and an outer diameter of 1.0 mm. The suction on the recording electrodes was 380 to 390 mmHg. All signals were amplified and recorded by a Grass ink writing amplifier-recorder (7 PCM 12 C). All recordings were made within 2 hours after removal of the tissue from the animal. The duration of active and quiet periods and the amplitude of the slow waves in the active and quiet periods were measured. The frequency in the active and quiet periods and the overall frequency were determined. The number of action potentials superimposed on the omnipresent slow waves per minute and the number of bursting periods within a 5-minute period were determined. These parameters were determined before and after increasing the distention of the intestinal segment.

Results

ICC-DMP and VAChT

Confocal and EM Immunohistochemistry

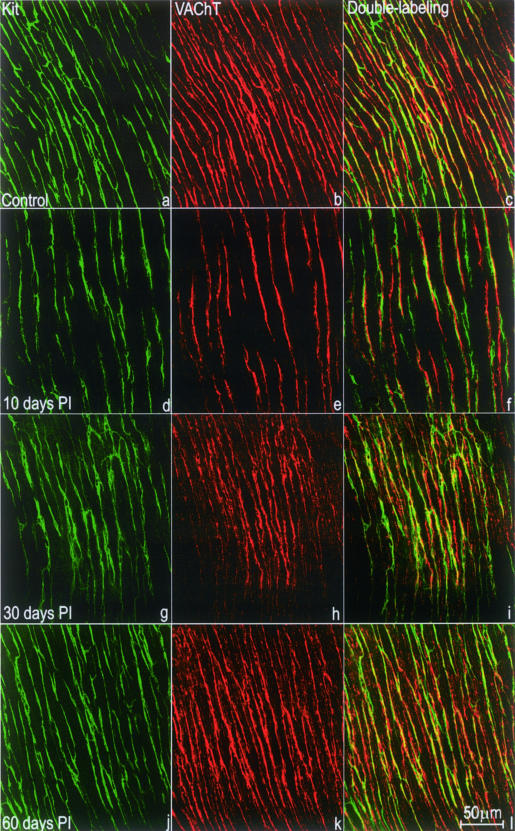

In control mice, c-Kit-positive ICC-DMP were bipolar and were connected to each other by long processes to form a mesh-like structure (Figure 1a). ICC-DMP were significantly reduced in the tissues 10 days after infection (Figure 1d), primarily recovered at 30 days after infection (Figure 1g), and returned to normal at 60 days after infection (Figure 1j). Numerous VAChT-immunoreactive nerve fibers, rich in varicosities were seen at the DMP level (Figure 1b). VAChT-immunoreactive nerve fibers were significantly reduced in the tissues 10 days after infection (Figure 1e), primarily recovered 30 days after infection (Figure 1h), and returned to normal 60 days after infection (Figure 1k).

Figure 1.

Whole mount preparations showing immunoreactivities for c-Kit and VAChT at the level of the DMP. a–c: Control; d–f: 10 days after infection; g–i: 30 days after infection; and j–l: 60 days after infection. c-Kit-positive ICC-DMP (green; a, d, g, j) were mostly bipolar in shape and closely apposed to VAChT-positive nerve varicosities (red; b, e, h, k) in the DMP. c, f, i, and l: c-Kit and VAChT double labeling. a to f: At day 10 after infection (d–f), immunoreactivities for both c-Kit and VAChT were reduced compared with control tissue (a–c). g to l: c-Kit and VAChT reactivities recovered to some degree by day 30 after infection (g–i) and returned to normal by day 60 after infection (j–l).

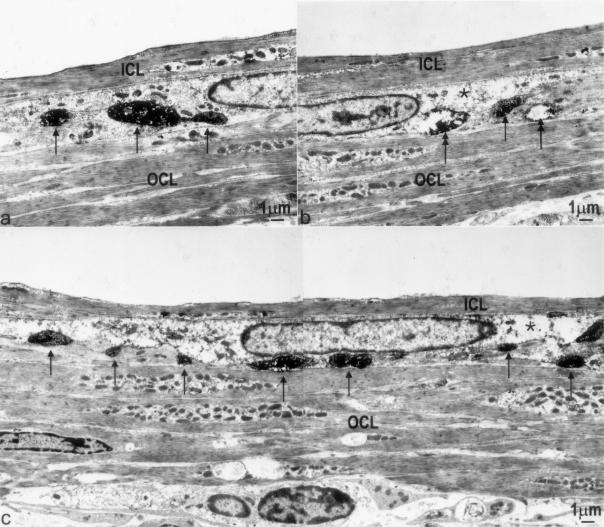

VAChT/c-Kit double labeling showed that most, if not all, of the VAChT-immunoreactive nerve fibers were closely apposed to the ICC-DMP (Figure 1; c, f, i, and l) and transmission electron microscope confirmed this (Figure 2; a to c). Moreover, ultrastructural examination confirmed that, compared with control tissue (Figure 2a), VAChT-immunoreactive varicosities were reduced 10 days after infection (Figure 2b), and recovery was seen at 30 days after infection (Figure 2c) although significant structural damage was still present. Complete recovery occurred 60 days after infection (not shown).

Figure 2.

Injury, loss, and recovery of VAChT nerve varicosities. a: Immunoelectron microscopy for VAChT showed regular appearance of cholinergic nerve varicosities (arrows) in the DMP of control tissue. Immunoreactivity is seen as dark area with higher electron density (arrows). b: Ten days after infection, cholinergic varicosities were difficult to find; those present showed (partially) depleted cytoplasm (double arrows). The single arrow indicates an intact nerve varicosity. c: Thirty days after infection, more VAChT-positive nerves (arrows) were observed compared with 10 days after infection, significant ultrastructural damage was still present in the ICC-DMP. *, Partially depleted cytoplasm. ICL, inner circular muscle layer; OCL, outer circular muscle layer.

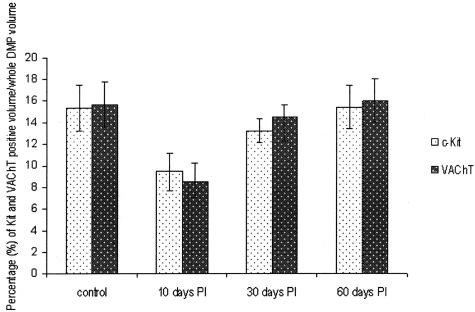

Figure 3 shows the result of quantification of c-Kit- and VAChT-immunoreactive structures at the level of the DMP of control and infected tissues. Both c-Kit (P < 0.05)- and VAChT (P < 0.01)-immunoreactive elements were significantly decreased in the tissues 10 days after infection. No significant difference with control was observed at 30 days after infection (P = 0.38 for c-Kit and P = 0.71 for VAChT) and 60 days after infection (P = 0.97 for c-Kit and P = 0.91 for VAChT).

Figure 3.

Quantification of c-Kit and VAChT immunoreactivity. Percentage of c-Kit- and VAChT-positive volume at the level of the DMP (mean ± SE, n = 10), expressed as percent volume of total volume of DMP area in the field. Ten days after infection: significantly reduced compared to control (P < 0.05 for c-Kit reaction; P < 0.01 for VAChT reaction). Thirty days after infection: no significant difference from control (P = 0.38 for c-Kit reaction; P = 0.71 for VAChT reaction). Sixty days after infection: no significant difference from control (P = 0.97 for c-Kit reaction; P = 0.91 for VAChT reaction).

ICC-DMP

Electron Microscopy

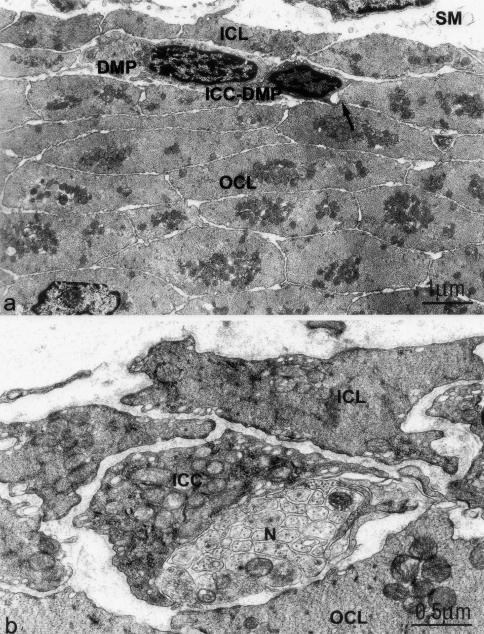

In control animals, ICC-DMP (Figure 4a) are identified as spindle-shaped cells located in between the inner and outer subdivisions of the circular muscle layer and closely apposed to the nerve bundles of the DMP.1,6 The cytoplasm is electron-dense and rich in mitochondria, and numerous caveolae are aligned along the plasma membrane (Figure 4b). The Golgi apparatus is small and cis-ternae of the rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) scarce. All ICC-DMP have a continuous basal lamina (Figure 4, a and b). Moreover, in the mouse the ICC-DMP are frequently in contact with each other and the smooth muscle cells of the outer circular muscle layer by means of gap junctions (Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

ICC-DMP have close connections with smooth muscle cells and nerve varicosities of the DMP in control tissue. a: An ICC-DMP in the DMP between the inner (ICL) and outer circular muscle layer (OCL). Gap junctions are numerous between smooth muscle cells and between ICC-DMP and smooth muscle cells (arrow). SM, submucosa. b: Numerous mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, and caveoli are present in the ICC-DMP. Close connections occur between ICC-DMP and enteric nerve varicosities (N) in the DMP.

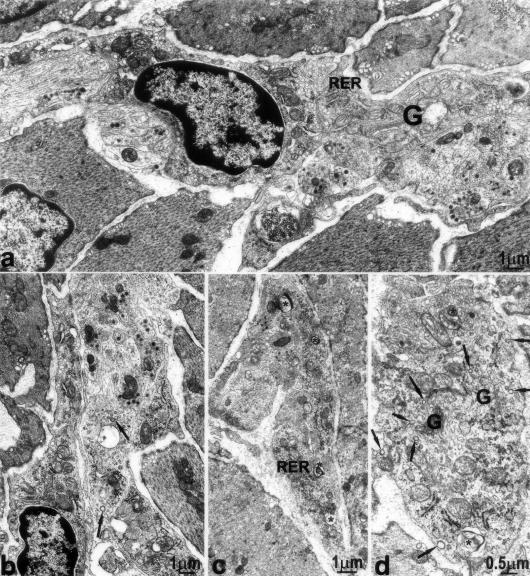

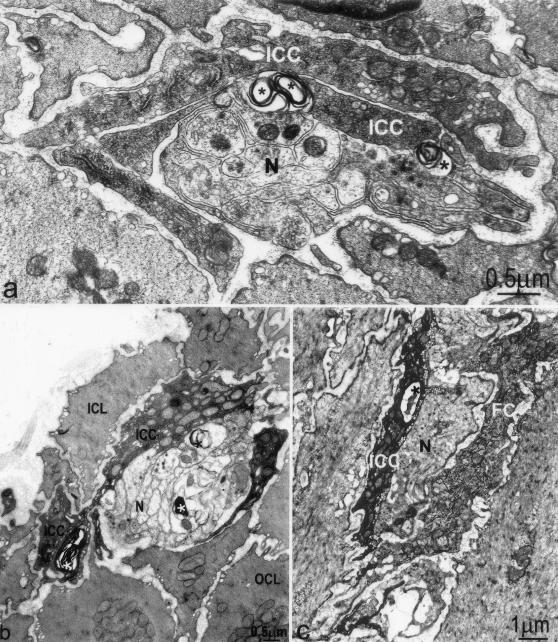

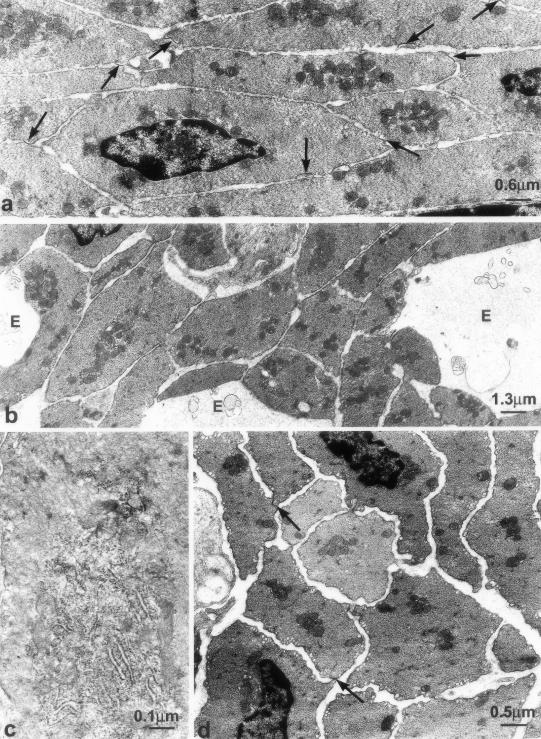

Two to fifteen days after infection, ICC-DMP displayed severe ultrastructural abnormalities. An extended RER and Golgi apparatus (Figure 5; a, c, and d) characterized the ICC and coated vesicles, located as in controls at the budding face of the Golgi apparatus and close to the plasma membrane, were significantly more numerous (Figure 5, b and d; Figure 6). Moreover, in the cytoplasm of some ICC-DMP there were lamellar bodies (Figure 5, c and d) and autophagosomes (Figure 7c). Loss of cell-to-cell contacts was widespread. Gap junctions were virtually absent and lamellar bodies were seen between ICC as well as between ICC and nerve varicosities (Figure 7a). These injuries were the most extensive at 10 days after infection, when wide areas of cytoplasmic depletion devoid of organelles were observed (Figure 8; a to d). By day 2 up to 15 days after infection the basal lamina was lacking or discontinuous.

Figure 5.

Ultrastructural changes in ICC-DMP, 2 to 15 days after infection. a and b: Two days after infection: increased rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER), large Golgi apparatus (G), and coated vesicles (arrows) in ICC-DMP. c: Fifteen days after infection: RER and lamellar bodies (asterisks) in a process of ICC-DMP. d: Fifteen days after infection: coated vesicles (arrows) at the budding face of the Golgi apparatus (G) and close to plasma membrane. *, Lamellar bodies.

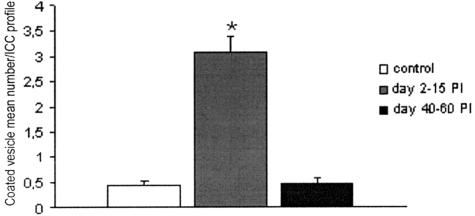

Figure 6.

Dramatic transient increase in coated vesicles in ICC-DMP. Difference is significant between control and 40 to 60 days after infection versus 2 to 15 days after infection. *P ≤ 0.01. No significant difference between control and 40 to 60 days after infection.

Figure 7.

Loss and recovery of cell to cell contacts. a: Two days after infection, lamellar bodies (arrows) are observed at areas of contact between ICC-DMP and between ICC-DMP and enteric nerve varicosities (N). b: Slightly injured ICC-DMP (ICC) and associated nerve structure (N) at day 30 after infection. Close connections between ICC-DMP and nerves reappeared. There are still lamellar bodies (*) within both ICC-DMP and nerve varicosities. c: Fibroblasts, which are also interstitial cells of the DMP, showed much less damage compared to ICC-DMP. Injury to an ICC-DMP (ICC) as reflected by the presence of autophagosomes (*) in its cytoplasm; a neighboring fibroblast (FC) is intact.

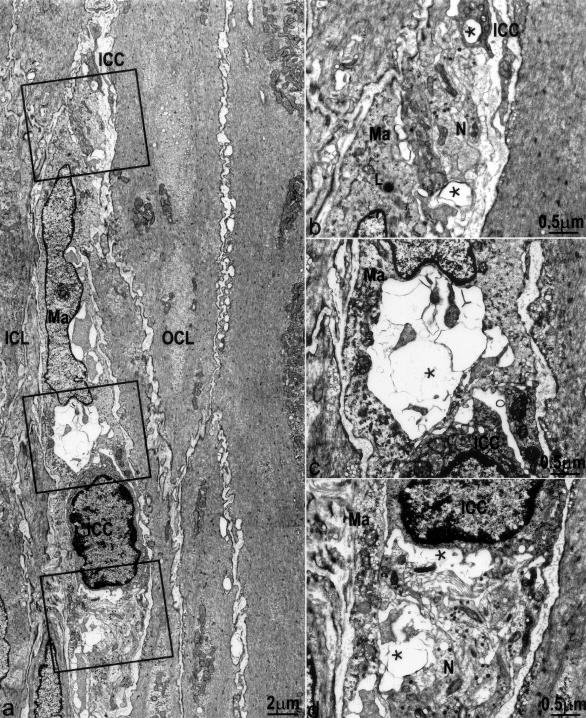

Figure 8.

Structural injury to ICC-DMP and enteric nerves associated with macrophages 10 days after infection. a: Severe injury to ICC-DMP and nerve varicosities, no significant injury to smooth muscle cells. Injured cells were associated with macrophages (Ma). b–d: Enlarged details of a. ICC-DMP (ICC) and nerve varicosities (N) are associated with macrophages (Ma). *, Damaged structures. Close connections between ICC-DMP and nerves as well as gap junctions between ICC-DMP and smooth muscle cells are not present. L, Lysosome within the macrophage.

By 23 days after infection, gap junctions were newly present, although rare, and became numerous as in controls by 30 to 60 days after infection. At 30 days after infection, an almost continuous basal lamina reappeared, but many ICC-DMP were still rich in RER and had occasional intercellular lamellar bodies (Figure 7b). At 60 days after infection, all ICC-DMP had normal features and the number of coated vesicles was similar to controls (Figure 6). Statistical analysis revealed that the mean number of coated vesicles in ICC-DMP per ICC profile was 0.42 ± 0.11 in controls, 3.06 ± 0.32 at 2 to 15 days after infection (P < 0.01), and 0.47 ± 0.11 at 40 to 60 days after infection (Figure 6).

Nerve Varicosities of the DMP

In control animals, the nerve varicosities of the DMP contained either small agranular vesicles or large granular vesicles and were frequently in close contact with the ICC-DMP (Figure 4, a and b). Two to fifteen days after infection, many nerve varicosities remained normal (Figure 5, a and b) but others, especially those close to the damaged ICC-DMP, were reduced (Figure 7a) or had completely lost their content (Figure 8, b and c) or contained lamellar bodies (Figure 7a). Moreover, scattered areas were devoid of nerve structures (Figure 8d). By 30 to 60 days after infection, most nerve varicosities were similar to control and only a few of them still showed lamellar bodies (Figure 7b).

Macrophages

In the control pathogen-free animals, macrophages or other inflammatory cells were not present in the DMP area. Three to fifteen days after infection, inflammatory cells, mainly macrophages, were present, at variance with the submucosa where there were also many granulocytes and lymphocytes. The ICC-DMP and the DMP nerves were frequently contacted by macrophages (Figure 8; a to d). Lamellar bodies were particularly numerous when ICC-DMP and nerves were contacted by macrophages (Figure 8b). Occasionally, there was also a loss of the cell content (Figure 8, c and d). Macrophages were less frequently observed at 23 to 40 days after infection and continued to be present day 60 after infection.

Inner Circular Muscle Layer

The inner circular muscle layer in control mice is only one cell thick, no close contacts with nerve varicosities nor specialized cell-to-cell junctions with the ICC-DMP were present (Figure 4, a and b; Figure 9a). Two to fifteen days after infection, the smooth muscle cells contained markedly extended RER and Golgi apparatus (Figure 9b) and were increased in size (Figures 9b, 10b, and 11b). Days 23 to 60 after infection constituted a recovery phase of synthetic activity as judged by a gradual return to a normal RER and Golgi apparatus extension. However, this period also witnessed structural changes that remained at day 60 after infection. Smooth muscle cells formed thin, short protrusions; that gradually increased in number, extended into the intercellular space (Figure 9, c and d) and finally formed branches obliquely oriented (Figure 9e). Because of this increase in branching, the smooth muscle cells acquired a ramified shape and their perimeter increased significantly and this maintained up to day 60 after infection (Figure 11b). Moreover, an overlapping of these ramifications also occurred and, consequently, the inner circular muscle layer gradually stratified to double its thickness (Figure 9, d and e; Figure 10; Table 1).

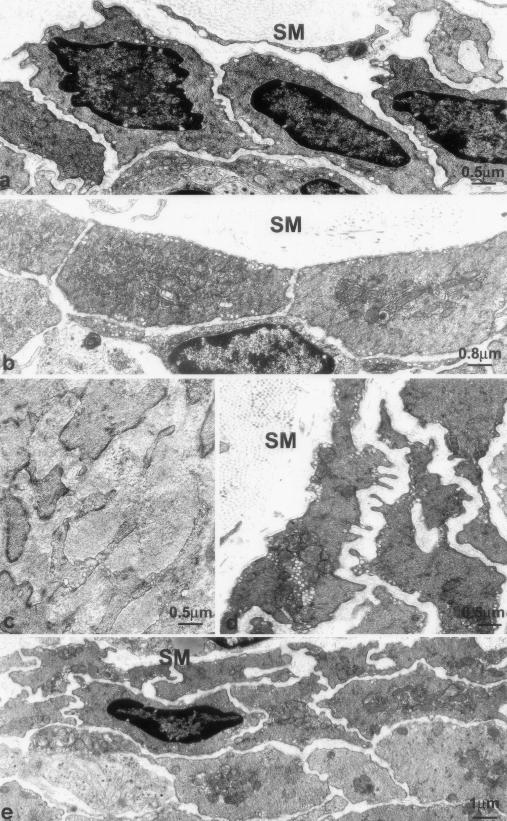

Figure 9.

Ultrastructure of the inner circular muscle layer. a: Control. The inner circular muscle layer consists of one layer of smooth muscle cells. b: Two days after infection. Increased size of the smooth muscle cells and richness in RER and Golgi apparatus. c: Twenty-three days after infection. Enlarged stroma with collagen deposits and smooth muscle cells with numerous branches. d and e: Forty days after infection (d) and 60 days after infection (e). Richness in caveolae and ramified shape of the smooth muscle cells and stratification of the inner circular muscle layer. SM, submucosa.

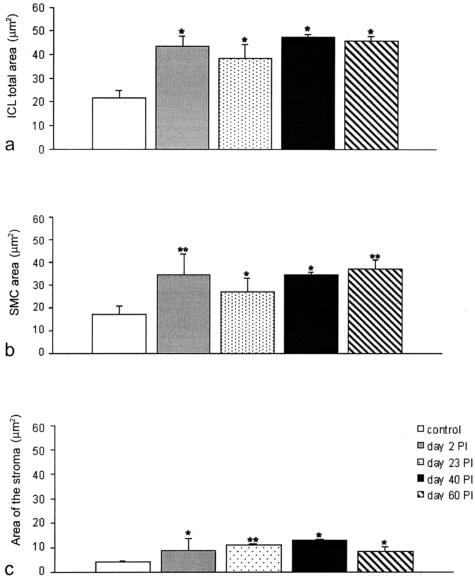

Figure 10.

Quantification of increase in smooth muscle area. a: Total area of the inner circular muscle layer. Significant difference for control versus 2 days after infection, 23 days after infection, 40 and 60 days after infection. No significant difference among the other groups. b: Area occupied by the inner smooth muscle cells. Increase occurred by day 2 up to 60 days after infection. Significant difference for control versus 2 days after infection, 23 days after infection, 40 and 60 days after infection. c: Area occupied by the stroma in the intercellular space. Significant difference for control versus 2 days after infection, 23 days after infection, and 40 and 60 days after infection. *P < 0.01, **P < 0.05.

Figure 11.

Quantification of caveolae and SMC perimeter. a: The mean number of caveolae in the smooth muscle cells (SMCs) of the inner circular muscle layer shows a gradual increase up to a factor 2× 40 to 60 days after infection. Significant difference between control as well as 2 to 15 days after infection versus 40 to 60 days after infection (P < 0.01). No significant difference between control and 2 to 15 days after infection. b: The mean perimeter of the SMC of the inner circular muscle layer increased up to 40 to 60 days after infection. Significant difference for both control and 2 to 15 days after infection versus 40 to 60 days after infection (P < 0.01). No significant difference between control and 2 to 15 days after infection.

Table 1.

Quantification of the Changes Occurring in the Inner Circular Muscle Layer (ICL) by 2 up to 60 Days after Infection

| Control | 2 days after infection | 23 days after infection | 40 days after infection | 60 days after infection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total ICL area (μm2) | 21.6 ± 3.6 | 43.4 ± 9.0* | 38.5 ± 5.7* | 47.4 ± 1.2* | 45.7 ± 3.9* |

| SMC area (μm2) | 17.1 ± 3.0 | 34.5 ± 4.4† | 27.3 ± 5.7* | 34.3 ± 1.2* | 37.2 ± 2.0† |

| Stroma area (μm2) | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 8.9 ± 4.6* | 11.2 ± 0.1† | 13.1 ± 0.1* | 8.5 ± 1.8* |

| Stroma/total (%) | 24.8 | 25.8 | 41.1* | 38.2* | 22.9 |

| SMC/total (%) | 75.2 | 74.2 | 58.9* | 61.8* | 77.2 |

| Mean perimeter of SMC (μm) | 11.9 ± 0.1 | 12.3 ± 0.1 | Not evaluated | 18.1 ± 0.7* | |

| Mean number of caveolae/SMC | 12.9 ± 0.9 | 19 ± 0.1 | Not evaluated | 36.6 ± 0.7* |

SMC, smooth muscle cell.

Significant increase (*P < 0.01,†P < 0.05) compared to control.

Starting at day 2 after infection and up to 60 days after infection, the number of caveolae significantly increased in all smooth muscle cells (Figure 9, b, d, and e; Figure 11a; Table 1). This increase could not be accounted for by the increase in cell perimeter. Together with the increased size (cell area) and ramification (cell surface) of the smooth muscle cells, the intercellular space also enlarged (Figure 9, c, d, and e; Figure 10c; Table 1) and by day 23 after infection it became rich in collagen fibrils (Figure 9c). The ratio between the space occupied by intercellular connective tissue and smooth muscle cells increased 23 to 40 days after infection but returned to normal at 60 days (Figure 10, a to c; Table 1).

Outer Circular Muscle Layer

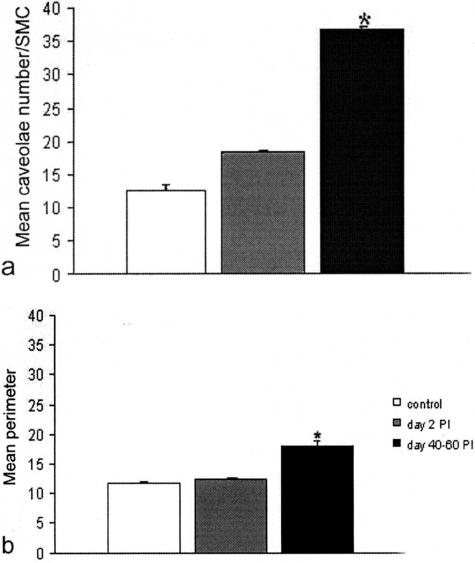

In control tissue, smooth muscle cells of the outer circular muscle layer were frequently connected by gap junctions (Figure 12a). Smooth muscle cells formed gap junctions with ICC-DMP (Figure 4a) and made contact with intramuscular nerve varicosities. Two to ten days after infection, the intercellular space became widened and contained an edematous stroma (Figures 5 and 12b); concomitantly, loss of gap junctions occurred. A prominent increase in RER and Golgi apparatus extension was observed in the smooth muscle cells 8 to 15 days after infection (Figure 12c), but by day 23 after infection, smooth muscle cells were normal in ultrastructure. Between days 40 and 60 after infection, gap junctions reappeared (Figure 12d), but the intercellular space remained larger than in control tissue and the stroma became moderately fibrotic.

Figure 12.

Ultrastructural changes in the outer circular muscle layer. a: Control. Arrows indicate gap junctions. b: Two days after infection. Wide edematous areas (E) and absence of gap junctions. c: Eight days after infection. Richness in RER in a smooth muscle cell. d: Forty days after infection. Smooth muscle cells were normal and gap junctions were newly present (arrows), but the stroma between the muscle cells is wider than in control.

Distention-Induced Rhythmic Electrical Activity

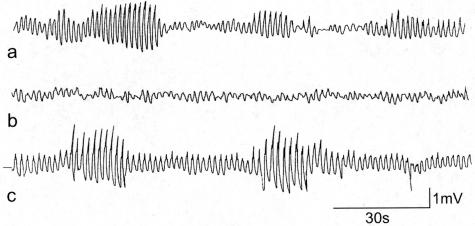

In control mice with distention, a segment of intestine displayed regular slow wave activity with or without action potential generation (Figure 13). When action potentials occurred they were seen in bursts. A burst of action potentials was observed when 5 to 10 consecutive slow waves would carry action potentials. The number of bursts per minute was highly variable ranging from 0.3 to 2.2 bursts per minute (1.1 ± 0.5 bursts per minute). Spiking increased by distention. During the burst type activity the spiking amounted to 24.9 ± 1.7 action potentials/minute. The slow waves with superimposed action potentials propagated anally causing peristaltic contractile activity. The slow wave frequency after distention during nonburst or quiet periods and during a burst of action potentials was, respectively, 37.7 ± 1.0 cpm and 39.6 ± 1.0 cpm. Ten days after infection, segments of the intestine did not show rhythmic bursts of action potentials with or without stretch applied to the tissue. The strips of isolated muscle were thickened yet were much more fragile compared to control. In addition, the ability to develop stretch-induced bursts of action potentials and stretch-induced peristalsis was completely abolished. Consistently, no visible rhythmic contractile activity occurred in the intestinal segment. Thirty days after infection, segments of the intestine were much less fragile and in preparations from four infected mice, spontaneous activity was present with bursting activity. However, segments from only one of four animals showed increased bursting on distention. In the segments that showed increased bursting, the slow wave activity was still very irregular so that quantification was not possible. Sixty days after infection, the slow wave pattern was restored. Even without distention (<1 cm) a stable slow wave pattern was observed. Short periodic bursts of action potentials occurred both before and after distention, but distention increased the number of bursting periods and the spiking/minute to a normal level as observed in healthy control tissue. A stable pattern of periodic bursts of action potentials occurred at a burst frequency of 6.0 ± 1.5 per minute and a burst duration ranging from 5.8 to 17.3 seconds. The slow wave activity was so stable that a frequency increase could be observed in response to distention. The slow wave frequency increased from 35.2 ± 0.1 cycles/minute to 45.6 ± 0.5 cycles/minute. These quantitative parameters were all within normal limits.

Figure 13.

Distention induced periodic bursts of slow waves with increased amplitude and superimposed action potentials. a: Control conditions. b: Day 10 after infection, distention did not evoke any burst type activity. c: Day 60 after infection. Distention-induced periodic activity was normal. The recordings in a and c were taken after distention-induced activity stabilized, which was 5 minutes after initiation of distention.

Discussion

The present study shows that partial loss and structural injury to ICC-DMP is associated with a loss of distention-induced patterns of electrical activity that previously have been shown to be associated with distention-induced peristalsis.14 The injury to ICC is temporally associated with injury to nerve varicosities including those of cholinergic nerves, which are a critical part of the distention-induced increase in muscle activity.23–25 The time of onset and the time of recovery for both structural and physiological changes are very similar. These data indicate that mucosal inflammation of the gut can spill over into the musculature where it affects in particular the ICC and associated nerve structures which can explain the often observed association between inflammation and obstruction. In addition to these temporary changes, there is a persistent remodeling of the inner circular muscle layer that borders the submucosa and hence is closest to the lumen. This may affect long-term sensitivity to distention.

Dramatic transient changes were observed in ICC-DMP after infection, in particular associated with the cell membrane. Although c-Kit immunohistochemistry suggested loss of cells, the ultrastructural findings primarily showed membrane damage; marked cell degeneration was not observed nor differentiating ICC. This suggests that the massive membrane injury is accompanied by loss of c-Kit-positive membrane. It is therefore possible that loss of cell structures is limited and that ICC function is lost because of structural injury and loss of c-Kit positivity. The recovery was not focused on generating new cells but on cell repair clearly reflected in the ultrastructural findings, in particular the enlargement of the organelles responsible for protein synthesis (RER and Golgi apparatus) and a significantly increased number of coated vesicles representing newly formed plasma membrane either at the budding face of the Golgi apparatus, where they form, or close to the plasma membrane that is their final destination. The presence of lamellar bodies at contact areas signified degeneration of gap junctional contact with other ICC and synapse-like contact with nerves. ICC-DMP are innervated by cholinergic (VAChT-positive) nerves as shown previously for humans7 and the guinea pig.26 Close association with nerves has always been a hallmark of ICC-DMP.2 From 8 to 23 days after infection contacts between ICC-DMP and DMP nerves reduced markedly and c-Kit-VAChT double labeling showed a significant reduction of VAChT-positive nerves 10 days after infection indicating markedly reduced communication between excitatory nerves and ICC. Recovery of cholinergic innervation paralleled recovery of ICC. Hence, loss of cell to cell communication is likely a major mechanism underlying loss of function. There are interesting similarities with a previous study on ICC bordering the submucosa in the human colon.27 The structural changes were similar, close association with macrophages was also observed and rather selective injury to ICC and associated nerve structures, with smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts relatively undisturbed. An animal model of colitis showed similar findings that were associated with functional abnormalities.28 Hence, the modalities of recovery are the dramatic increase in rough endoplasmic reticulum in ICC, followed by restoration of cell structure and junctions with neighboring cells, and the withdrawal of macrophages. ICC injury and recovery are an important part of the pathology of intestinal inflammation related to associated motor dysfunction.

The present study shows that injury to ICC-DMP and associated nerve structures was temporally connected to loss of distention-induced patterns of electrical activity that are associated with distention-induced peristalsis.14 This suggests that the ICC-DMP and associated nerves are a critical part of the pathway that links physical distention with stimulation of enteric nerves that provide the periodic motor activity characteristic of distention-induced peristalsis. In the dog29 and in the mouse,2 the ICC-DMP have been suggested to detect muscular tone and intraluminal pressure changes and the present results provide functional support for this hypothesis. Consistently, in Nippostrongylus brasiliensis-infected rats the absence of c-Kit-positive cells was accompanied by a loss of ICC-DMP even after inflammation had spontaneously resolved 30 days after infection.12 The authors speculated that this loss, together with impairment in tachykinergic control of jejunal functions, might be responsible for alterations of motility and, in particular, of sensitivity to distension. It is possible that the inner circular muscle layer that borders the submucosa is also part of the structure that senses stretch induced by increase in intraluminal pressure.30,31 The ICC-DMP and the inner circular muscle layer are specific structures for the small intestine, and their role is reasonably related to a motor function specific of this area. The present results have important similarities with a study on human orthotopic ileal bladders32 where evidence was presented that the unit of DMP nerves, ICC-DMP, and the inner circular smooth muscle cells were involved in detection of distention. Orthotopic ileal bladders are continent urine reservoirs constructed after radical cystectomy by replacing the excised urinary bladder with an ileal loop still attached to its mesentery. Motor patterns, intraluminal pressures, and volume capacity were recorded in situ before corrective surgery and anatomical characteristics were studied in full-thickness specimens from the ileal reservoirs removed during corrective surgery. Morphological examination was performed with both light and electron microscopy. The ileal reservoirs generated phasic activity when filled with liquid, and all retained the ICC-AP; however, after extended periods (eg, 3 to 8 years), the ICC-DMP, together with the inner circular muscle layer and the DMP completely disappeared (ICC-AP remained normal) and the muscle wall lost its normal responsiveness to distention.32 Based on morphological data, a similar role is being proposed for ICC-IM in the stomach.33,34

We have previously reported that ICC-AP are injured by the T. spiralis infection.17 The structural and functional injury was due to cytokine secretion from macrophages and these macrophages were colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1)-dependent.35,36 The ICC-DMP injury presently found was qualitatively similar to injury to the ICC-AP but the injury was much more severe.17,37,38 It is unlikely that the injury to ICC-AP is associated with the functional changes described here. First, the primary role of ICC-AP is the generation of pacemaker activity39,40 and there is no evidence for a role of ICC-AP in detection of tension although this cannot be ruled out. Second, the timing of the recovery of ICC-AP mimics that of the recovery of electrical pacemaker activity, ∼15 days after infection,17 which is much faster than the recovery of distention-induced peristaltic activity and ICC-DMP.

Macrophages were present in control tissue in the external muscle layers, in particular the myenteric plexus area, and are considered to be resident macrophages.41,42 In the DMP area macrophages were absent in our pathogen-free mice although they were encountered rarely in nonpathogen-free mice in which they were associated with ICC-DMP processes.3 After the T. spiralis infection, in areas of severe damage to ICC-DMP and associated nerve structures, macrophages were seen to be abundant. Lymphocytes were also observed in the DMP area after infection but their numbers were far less than macrophages and lymphocytes did not make close contact with ICC-DMP or nerves. In contrast, lymphocytes and granulocytes were prominent in the submucosa. Therefore, it is likely that a major part of the injury to ICC-DMP and related nerves is mediated by macrophages because they were the only immune cell prominent in the DMP area and close contact between them and injured ICC-DMP/nerves was common. The time course of ICC-DMP and nerve injury and recovery and the presence and decline of macrophages coincided as well. This suggests that the structural and functional injury was, at least in part, due to cytokine secretion from macrophages. No enlarged and dilated blood vessels were found in the DMP area as reported in the Auerbach’s plexus after T. spiralis infection.38 Hence the macrophages in this area likely migrated from the submucosa or Auerbach’s plexus area or developed from resident macrophages. An association between macrophages and ICC injury was also observed in ulcerative colitis27 and in an animal model for Hirschsprung’s disease where in the distended part of the colon altered motor activity was associated with an influx of macrophages and injury to ICC.43

T. spiralis infection markedly and permanently affected the inner circular muscle layer that is only one cell layer thick in the mouse and separates the DMP area from the submucosa. Transient changes that occurred were an increase in RER and Golgi apparatus, indicating intense protein synthesis possibly related to the increase in cell size and the synthesis of collagen. Changes that did not subside were enlargement of the muscle cells, development of branches, resulting in a ramified cell shape, a marked increase in the number of caveolae in the smooth muscle cells, and an enlargement of the intercellular space with collagen deposits. The thickening of the inner circular muscle layer was due to enlargement of the muscle cells and the appearance of multiple layers to extensive overlapping of the cell branches. An increase in the number of muscle cells is unlikely because differentiating smooth muscle cells were never observed. Branching of smooth muscle cells might represent an adaptive attempt to maintain mechanical properties of the inner circular muscle layer in the presence of a fibrotic stroma. The increased number of caveolae might represent an increased ability to respond to signaling molecules as part of the attempt to withstand the adverse environment.44 In response to a N. brasiliensis infection, injury to ICC was more severe and longer lasting, although no changes in the inner circular muscle occurred.12 A different immune response may explain the differences between N. brasiliensis and T. spiralis. In contrast to a T. spiralis infection in which macrophages are the dominant immune cell in the musculature, mast cells penetrated the musculature after a N. brasiliensis infection45 and changes in motor function in response to a N. brasiliensis infection depended on the presence of mast cells.46 Interestingly, the presence of mast cells in the musculature was long lasting with a half life of 40 days, which may explain the severity of the damage to ICC.45

The present study provides further evidence for the T. Spiralis-infected mouse being a model for postinfectious enteropathies, a significant problem in clinical gastroenterology. The present study shows persistent changes in the inner circular muscle layer. Long-lasting decreases in excitatory47 and inhibitory48 neurotransmission were also observed. One consequence is the persistence of retro-peristalsis,17,49 which also occurs in IBS.50 Macrophages persisted in the DMP area at least until day 60 after infection similar to the Auerbach’s plexus area noted previously.38 There is also persistence of CD3-positive cells.49 In addition, corticosteroids suppressed some of the postinfectious symptoms giving arguments for the hypothesis that continued immune activation is involved in postinfectious motor dysfunction.49

The present results support the hypothesis that the ICC-DMP, possibly together with the inner circular muscle layer and DMP varicosities, represent the intestinal stretch receptor sensing intraluminal pressure changes. A mucosal T. spiralis infection is particularly affecting the DMP area at the border of the submucosa thereby affecting a major function of the musculature, distention-induced motor activity. The changes in the inner circular muscle layer represent an attempt to restore the mechanical properties of this layer, but may also result in a permanent change in sensitivity to distention after infection.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Jan D. Huizinga, McMaster University, HSC-3N5C, 1200 Main St. West, Hamilton, ON, L8N 3Z5, Canada. E-mail: huizinga@mcmaster.ca.

Supported by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and a fellowship from the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology sponsored by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Janssen-Ortho (to X.Y.W.).

References

- Thuneberg L. Interstitial cells of Cajal: intestinal pacemaker cells? Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 1982;71:1–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumessen JJ, Thuneberg L, Mikkelsen HB. Plexus muscularis profundus and associated interstitial cells. II. Ultrastructural studies of mouse small intestine. Anat Rec. 1982;203:129–146. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092030112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumessen JJ, Thuneberg L. Plexus muscularis profundus and associated interstitial cells. I. Light microscopical studies of mouse small intestine. Anat Rec. 1982;203:115–127. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092030111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faussone Pellegrini MS, Cortesini C. Some ultrastructural features of the muscular coat of human small intestine. Acta Anat (Basel) 1983;115:47–68. doi: 10.1159/000145676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobilo T, Szurszewski JH, Farrugia G, Hanani M. Coupling and innervation patterns of interstitial cells of Cajal in the deep muscular plexus of the guinea-pig. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2003;15:635–641. doi: 10.1046/j.1350-1925.2003.00449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faussone-Pellegrini MS, Thuneberg L. Guide to the identification of interstitial cells of Cajal. Microsc Res Tech. 1999;47:248–266. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19991115)47:4<248::AID-JEMT4>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XY, Paterson C, Huizinga JD. Cholinergic and nitrergic innervation of ICC-DMP and ICC-IM in the human small intestine. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2003;15:531–543. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2003.00429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramon y, Cajal S. Histologie du Système Nerveux de l’Homme et des Vertébrés. Paris: Maloine,; 1911 [Google Scholar]

- Ward SM, Sanders KM, Hirst GD. Role of interstitial cells of Cajal in neural control of gastrointestinal smooth muscles. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16(Suppl 1):112–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-3150.2004.00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez M, Cayabyab FS, Vergara P, Daniel EE. Heterogeneity in electrical activity of the canine ileal circular muscle: interaction of two pacemakers. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 1996;8:339–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.1996.tb00272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumessen JJ, Mikkelsen HB, Thuneberg L. Ultrastructure of interstitial cells of Cajal associated with deep muscular plexus of human small intestine. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:56–68. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91784-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faussone-Pellegrini MS, Gay J, Vannucchi MG, Corsani L, Fioramonti J. Alterations of neurokinin receptors and interstitial cells of Cajal during and after jejunal inflammation induced by Nippostrongylus brasiliensis in the rat. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2002;14:83–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2002.00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga JD, Thuneberg L, Klüppel M, Malysz J, Mikkelsen HB, Bernstein A. The W/kit gene required for interstitial cells of Cajal and for intestinal pacemaker activity. Nature. 1995;373:347–349. doi: 10.1038/373347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga JD, Ambrous K, Der-Silaphet TD. Co-operation between neural and myogenic mechanisms in the control of distension-induced peristalsis in the mouse small intestine. J Physiol (Lond) 1998;506:843–856. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.843bv.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Der-Silaphet T, Malysz J, Arsenault AL, Hagel S, Huizinga JD. Interstitial cells of Cajal direct normal propulsive contractile activity in the small intestine. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:724–736. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70586-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malysz J, Thuneberg L, Mikkelsen HB, Huizinga JD. Action potential generation in the small intestine of W mutant mice that lack interstitial cells of Cajal. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:G387–G399. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.271.3.G387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Der T, Bercik P, Donnelly G, Jackson T, Berezin I, Collins SM, Huizinga JD. Interstitial cells of Cajal and inflammation-induced motor dysfunction in the mouse small intestine. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1590–1599. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.20221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonini M, Costa M. A pharmacological analysis of the neuronal circuitry involved in distension-evoked enteric excitatory reflex. Neuroscience. 1990;38:787–795. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90071-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro GA, Fairbairn D. Carbohydrates and lipids in Trichinella spiralis larvae and their utilization in vitro. J Parasitol. 1969;55:51–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermillion DL, Collins SM. Increased responsiveness of jejunal longitudinal muscle in Trichinella-infected rats. Am J Physiol. 1988;254:G124–G129. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1988.254.1.G124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malysz J, Donnelly G, Huizinga JD. Regulation of the slow wave frequency by IP3-sensitive calcium release in the murine small intestine. Am J Physiol. 2001;280:G439–G448. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.3.G439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu LWC, Huizinga JD. Electrical coupling of circular muscle to longitudinal muscle and interstitial cells of Cajal in canine colon. J Physiol (Lond) 1993;470:445–461. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M, Brookes SJ, Hennig GW. Anatomy and physiology of the enteric nervous system. Gut. 2000;47(Suppl 4):iv15–iv19. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.suppl_4.iv15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan SY, Brookes SJ, Costa M. Distension-evoked ascending and descending reflexes in the isolated guinea-pig stomach. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1997;62:94–102. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(96)00115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly G, Jackson T, Ambrous K, Ye J, Safdar A, Farraway L, Huizinga JD. The myogenic component in distension-induced peristalsis in the guinea pig small intestine. Am J Physiol. 2001;280:G491–G500. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.3.G491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XY, Sanders KM, Ward SM. Intimate relationship between interstitial cells of Cajal and enteric nerves in the guinea-pig small intestine. Cell Tissue Res. 1999;295:247–256. doi: 10.1007/s004410051231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumessen JJ. Ultrastructure of interstitial cells of Cajal at the colonic submuscular border in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1447–1455. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(96)70005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu G, Qian X, Berezin I, Telford GL, Huizinga JD, Sarna SK. Inflammation modulates in vitro colonic myoelectric and contractile activity and interstitial cells of Cajal. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:G1233–G1245. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.6.G1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchon G, Henderson R, Daniel EE. Circular muscle layers in the small intestine. Daniel EE, editor. Vancouver: Mitchell Press,; Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Gastrointestinal Motility. 1974:pp 635–646. [Google Scholar]

- Gabella G. Special muscle cells and their innervation in the mammalian small intestine. Cell Tissue Res. 1974;153:63–77. doi: 10.1007/BF00225446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoda H, Kudo T, Takahashi Y, Kato S. Ultrastructural and histochemical characterization of special muscle cells in the monkey small intestine. Arch Histol Cytol. 2000;63:217–228. doi: 10.1679/aohc.63.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faussone-Pellegrini MS, Serni S, Carini M. Distribution of ICC and motor response characteristics in urinary bladders reconstructed from human ileum. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:G147–G157. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.1.G147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox EA, Phillips RJ, Martinson FA, Baronowsky EA, Powley TL. Vagal afferent innervation of smooth muscle in the stomach and duodenum of the mouse: morphology and topography. J Comp Neurol. 2000;428:558–576. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001218)428:3<558::aid-cne11>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoud HR, Powley TL. Vagal afferent innervation of the rat fundic stomach: morphological characterization of the gastric tension receptor. J Comp Neurol. 1992;319:261–276. doi: 10.1002/cne.903190206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen HB, Thuneberg L. Op/op mice defective in production of functional colony-stimulating factor-1 lack macrophages in muscularis externa of the small intestine. Cell Tissue Res. 1999;295:485–493. doi: 10.1007/s004410051254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galeazzi F, Lovato P, Blennerhassett PA, Haapala EM, Vallance BA, Collins SM. Neural change in Trichinella-infected mice is MHC II independent and involves M-CSF-derived macrophages. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:G151–G158. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.1.G151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galeazzi F, Haapala EM, van Rooijen N, Vallance BA, Collins SM. Inflammation-induced impairment of enteric nerve function in nematode-infected mice is macrophage dependent. Am J Physiol. 2000;278:G259–G265. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.278.2.G259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XY, Berezin I, Mikkelsen HB, Der T, Bercik P, Collins SM, Huizinga JD. Pathology of interstitial cells of Cajal in relation to inflammation revealed by ultrastructure but not immunohistochemistry. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1529–1540. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62579-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh SD, Sanders KM, Ward SM. Spontaneous electrical rhythmicity in cultured interstitial cells of Cajal from the murine small intestine. J Physiol (Lond) 1998;513:203–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.203by.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen L, Robinson TL, Lee JCF, Farraway L, Hughes MJG, Andrews DW, Huizinga JD. Interstitial cells of Cajal generate a rhythmic pacemaker current. Nat Med. 1998;4:848–851. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen HB. Macrophages in the external muscle layers of mammalian intestines. Histol Histopathol. 1995;10:719–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalff JC, Schraut WH, Simmons RL, Bauer AJ. Surgical manipulation of the gut elicits an intestinal muscularis inflammatory response resulting in postsurgical ileus. Ann Surg. 1998;228:652–663. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199811000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Won KJ, Horiguchi K, Kinoshita K, Hori M, Torihashi S, Momotani E, Itoh K, Hirayama K, Ward SM, Sanders KM, Ozaki H. Muscularis inflammation and the loss of interstitial cells of Cajal in the endothelin ETB receptor null rat. Am J Physiol. 2004;287:G638–G646. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00077.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AW, Hnasko R, Schubert W, Lisanti MP. Role of caveolae and caveolins in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:1341–1379. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00046.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arizono N, Nakao S. Kinetics and staining properties of mast cells proliferating in rat small intestine tunica muscularis and subserosa following infection with Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. APMIS. 1988;96:964–970. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1988.tb00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay J, Fioramonti J, Garcia-Villar R, Bueno L. Alterations of intestinal motor responses to various stimuli after Nippostrongylus brasiliensis infection in rats: role of mast cells. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2000;12:207–214. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2000.00201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbara G, Vallance BA, Collins SM. Persistent intestinal neuromuscular dysfunction after acute nematode infection in mice. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1224–1232. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9322517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanovic A, Jimenez M, Fernandez E. Changes in the inhibitory responses to electrical field stimulation of intestinal smooth muscle from Trichinella spiralis infected rats. Life Sci. 2002;71:3121–3136. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)02179-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bercik P, Wang L, Verdu EF, Mao YK, Blennerhassett P, Khan WI, Kean I, Tougas G, Collins SM. Visceral hyperalgesia and intestinal dysmotility in a mouse model of postinfective gut dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:179–187. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simren M, Castedal M, Svedlund J, Abrahamsson H, Bjornsson E. Abnormal propagation pattern of duodenal pressure waves in the irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:2151–2161. doi: 10.1023/a:1010770302403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]