Abstract

Although diabetic animal models exist, no single animal model develops renal changes identical to those seen in humans. Here we show that transgenic mice that overexpress inducible cAMP early repressor (ICER Iγ) in pancreatic β cells are a good model to study the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Although ICER Iγ transgenic mice exhibit extremely high blood glucose levels throughout their lives, they survive long enough to develop diabetic nephropathy. Using this model we followed the progress of diabetic renal changes compared to those seen in humans. By 8 weeks of age, the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was already increased, and glomerular hypertrophy was prominent. At 20 weeks, GFR reached its peak, and urine albumin excretion rate was elevated. Finally, at 40 weeks, diffuse glomerular sclerotic lesions were prominently accompanied by increased expression of collagen type IV and laminin and reduced expression of matrix metalloproteinase-2. Nodular lesions were absent, but glomerular basement membrane thickening was prominent. At this point, GFR declined and urinary albumin excretion rate increased, causing a nephrotic state with lower serum albumin and higher serum total cholesterol. Thus, similar to human diabetic nephropathy, ICER Iγ transgenic mice exhibit a stable and progressive phenotype of diabetic kidney disease due solely to chronic hyperglycemia without other modulating factors.

Diabetic nephropathy is a leading cause of end-stage renal disease, and its incidence is increasing worldwide. Thirty to forty percent of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus patients suffer from end-stage diabetic nephropathy, which develops 35 to 40 years after the onset of diabetes.1–3 Once diabetic nephropathy becomes overt, there is no curative therapy, and most patients eventually progress to end-stage renal disease.

Despite vigorous efforts, the effective management of diabetic nephropathy has not been established. One reason is the unavailability of an optimal animal model of diabetic nephropathy. No animal model exhibits diabetic nephropathy identical to that of human. Therefore, to fully investigate the disease pathogenesis, appropriate animal models are essential. Although numerous animal models have been established in rodents and these diabetic animals develop kidney disease that resembles human disease, no single animal model develops renal changes identical to those seen in humans.4 Some rodent models of type I and II diabetes express some features of diabetic nephropathy, including hyperglycemia, polyuria, increased glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and proteinuria. Spontaneous type I diabetic animals, such as nonobese diabetic mice, die within 6 weeks without insulin therapy.5 Even with insulin treatment adjusted to maintain the diabetic state, nonobese diabetic mice develop limited glomerular lesions, with only mild mesangial sclerosis at most.6 Further, because the onset of diabetes is variable between 100 and 200 days of age, it is difficult precisely to detect the onset. In the spontaneous type II diabetic Goto Kakizaki rat, long-standing type II diabetes alone is not sufficient to induce progressive nephropathy unless a secondary injurious mechanism such as hypertension is induced by deoxycorticosterone acetate salt.7 Chemically induced diabetic rodents have a similar pattern.8 Because streptozotocin alone is not sufficient to produce progressive renal disease, streptozotocin plus subtotal nephrectomy9 or streptozotocin plus high-protein diet10 have been used to accelerate the process.

In this study, we describe the development of diabetic nephropathy and renal sclerotic changes in transgenic mice that specifically overexpress inducible cAMP early repressor (ICER Iγ) in pancreatic β cells. ICER Iγ is a transcriptional repressor transcribed from an alternative intronic promoter of the CREM gene and consists of only the DNA-binding domain.11,12 In pancreatic β cells, ICER Iγ competes with endogenous transcriptional activators to block DNA binding, efficiently suppressing insulin13 and cyclin A14,15 gene transcription. The suppression of insulin synthesis and β-cell proliferation by overexpressed ICER Iγ results in severe diabetes as early as 2 weeks of age and sustainable hyperglycemia by 40 weeks of age. In this model, mice survive for a long time (40 weeks) without insulin therapy. Diabetic renal changes start with glomerular hypertrophy, followed by glomerular basement membrane (GBM) thickening and development of sclerotic lesions, thus mimicking the progression of human diabetic nephropathy.

Materials and Methods

Generation of ICER Iγ Transgenic Mice

ICER Iγ transgenic (ICER Tg) mice were generated as described previously.14 Their background strain is C57BL/6J (Japan SLC Inc., Hamamatsu, Shizuoka, Japan). Three transgenic lines (Tg 7, Tg 12, Tg 23) were obtained from 62 founder mice. Copy numbers of the transgene in founder mice were 4, 4, and 6, respectively, as determined by Southern blot analysis. Tg mice were identified by polymerase chain reaction analysis of tail DNA. In all experiments, nontransgenic littermates (wild type, WT) were used as controls. Mice were housed in microisolator cages in a temperature-controlled room at 24 ± 2°C and at 50 ± 10% relative humidity under 12-hour light/dark cycle. Standard rodent diet (CE-2; CLEA Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and water were supplied ad libitum. All mice were handled in accordance with the Guidelines for Animal Experiments of Kyoto University. Because Tg 7 and Tg 12 have the same copies of the transgene, almost the same blood glucose value, and similar kidney lesions, the data presented here are from F2-F4 males of line Tg 12 and Tg 23 only.

Histological Study

Tg (n = 6 for each age) and WT (n = 6 for each age) mouse kidney halves were fixed in methyl Carnoy’s solution, embedded in paraffin, and cut into serial sections (2 μm). Kidney sections were stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) or periodic acid-methenamine silver (PASM). The remaining kidney halves were snap-frozen in cold acetone in OCT compound (Sakura Finetechnical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), and cryostat sections (4 μm) were used for immunohistochemical study.

Measurements of Glomerular Surface Area, PASM-Positive Area, and Glomerular Number

The area was measured in PASM-stained sections using Image-Pro Plus (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD). For each mouse, 50 glomeruli were analyzed. The PASM-positive area fraction was calculated as the ratio of PASM-positive area to glomerular surface area.16 Glomerular number was measured by counting all of the glomeruli per mid-transverse section of left kidney for each mouse.17

Electron Microscopy and Measurement of GBM Thickening

For electron microscopy, specimens were taken from the kidney of Tg (n = 4) and WT (n = 4) mice at 40 weeks of age, fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.05 mol/L phosphate buffer, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, and embedded in epoxy resin according to routine procedures. Sections were cut with a glass knife on a Reichert-Nissei Ultracuts microtome (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Sections were contrasted with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and observed with a Hitachi H7100 electron microscope (Hitachi, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Thickness of GBM was measured by the orthogonal intercept method of Jensen and colleagues.18

Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemistry, primary antibodies [rabbit anti-collagen type IV, 1:250 (PROGEN Biotechnik, Hei-delberg, Germany); rabbit anti-laminin, 1:100 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO); mouse anti-matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, 1:100 (NeoMarkers, Fremont, CA)] were used. Primary antibodies were detected by immunofluorescent labeling with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibodies. Sections were observed and photographed by a Zeiss LSM 410 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Japan, Osaka, Japan).

Measurement of Serum Variables

Blood glucose levels were determined by an enzyme-electrode method using Glutest (Sanwa Kagaku, Nagoya, Japan) on whole blood taken from the tail vein. HbA1c was measured from tail vein using DCA2000 analyzer (Bayer Medical, Tokyo, Japan). For other parameters, blood was withdrawn from the heart under pentobarbital anesthesia immediately before isolation of the kidney. Serum insulin was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Morinaga Institute of Biological Science, Yokohama, Japan). Creatinine was measured by high performance liquid chromatography. Total cholesterol was measured by enzymatic assays (Toyobo Biochemicals, Osaka, Japan). Albumin was measured by Bromcresol green method (Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd., Osaka, Japan).

Measurement of Urinary Variables

The urinary parameters measured were albumin and creatinine. They were measured at 8 to 40 weeks of age in 24-hour urine collection samples from mice housed in individual metabolic cages (n = 6 in each group). During the urine collection, mice were allowed free access to food and water. Albumin concentration was assayed using the Albuwell kit (Exocell Inc., Philadelphia, PA). Creatinine was measured by high performance liquid chromatography as described above. Body weight-adjusted creatinine clearance (Ccr) was calculated by the following equation: Ccr = urine creatinine (mg/dL) × urine volume (μL/min)/serum creatinine (mg/dL)/body weight (g).19

Data Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Comparison among each group was performed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Neuman-Keuls test to evaluate statistical significance between two groups. A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

ICER Tg Mice Exhibit Sustainable Hyperglycemia Due to Reduced Insulin Secretion

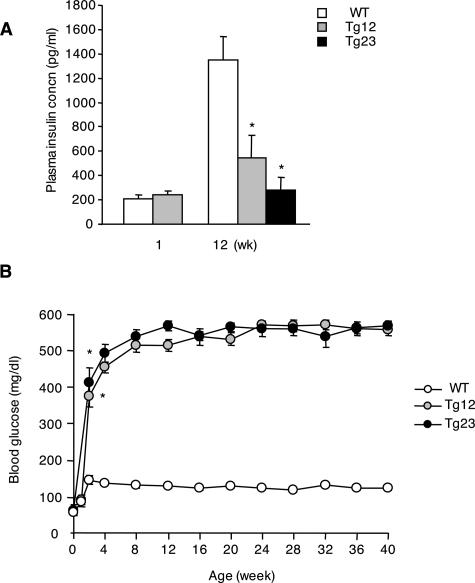

ICER Tg mice had abundant expression of ICER Iγ in pancreatic β cells but not in other organs,14 resulting in early onset of diabetes. Insulin secretion was nearly identical to that of WT mice at 1 week of age but fell dramatically thereafter (Figure 1A). Blood glucose levels were normal at birth but became markedly increased by 2 weeks of age, and severe hyperglycemia was sustained at least until 40 weeks of age in both Tg lines (Figure 1B). These mice survived for a long time without insulin therapy, without obesity or severe emaciation.

Figure 1.

ICER Tg mice exhibited sustainable hyperglycemia due to reduced insulin secretion. A: Fed plasma insulin of mice at 1 week and 12 weeks of age was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit. B: Fed blood glucose levels at indicated weeks were determined by an enzyme-electrode method. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.01. N = 6 for each group.

Diabetic Nephropathy in ICER Tg Mice

The physiological profile of 8- and 40-week-old mice is shown in Table 1. HbA1c was markedly elevated at 8 weeks of age and increased further at 40 weeks of age. ICER Tg mice were smaller than WT mice at 40 weeks of age. We examined organ weights and body length and found that kidney weight in Tg mice was significantly higher at 40 weeks of age, with no significant difference in other organ weights. Therefore, the difference in body weight between WT and Tg mice was likely due to changes in fat depots.

Table 1.

The Physical Profile of ICER Iγ Tg Mouse at 8 and 40 Weeks of Age

| Mouse line | Copy number | 8 Weeks

|

40 Weeks

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body wt (g) | HbA1c (%) | Kidney wt (g) | Body wt (g) | HbA1C (%) | Kidney wt (g) | Liver (g) | Heart (g) | Body length (cm) | ||

| Control | 0 | 23.9 ± 0.5 | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 0.33 ± 0.01 | 35.7 ± 1.3 | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 0.50 ± 0.03 | 1.84 ± 0.03 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 9.57 ± 0.10 |

| Tg12 | 4 | 21.3 ± 0.7 | 7.2 ± 0.3* | 0.35 ± 0.02 | 31.7 ± 0.4* | 12.0 ± 0.3* | 0.75 ± 0.05* | 1.99 ± 0.15 | 0.19 ± 0.003 | 8.87 ± 0.09* |

| Tg23 | 6 | 21.7 ± 0.3 | 7.9 ± 0.2* | 0.40 ± 0.01* | 31.2 ± 0.6* | 11.9 ± 0.4* | 0.71 ± 0.03* | 1.85 ± 0.02 | 0.18 ± 0.006 | 8.97 ± 0.03* |

Note. Results are mean ± SEM of male mice from each line (n = 9).

P < 0.01 versus wild-type mice.

Glomerular Number

We then examined changes in glomerular number in the midtransverse sections of kidneys at 40 weeks of age. There was no significant difference between WT mice and ICER Tg mice (WT versus Tg 12 or Tg 23, 103.3 ± 5.9 versus 103.3 ± 4.6 or 108.8 ± 5.5; n = 6 per each group.).

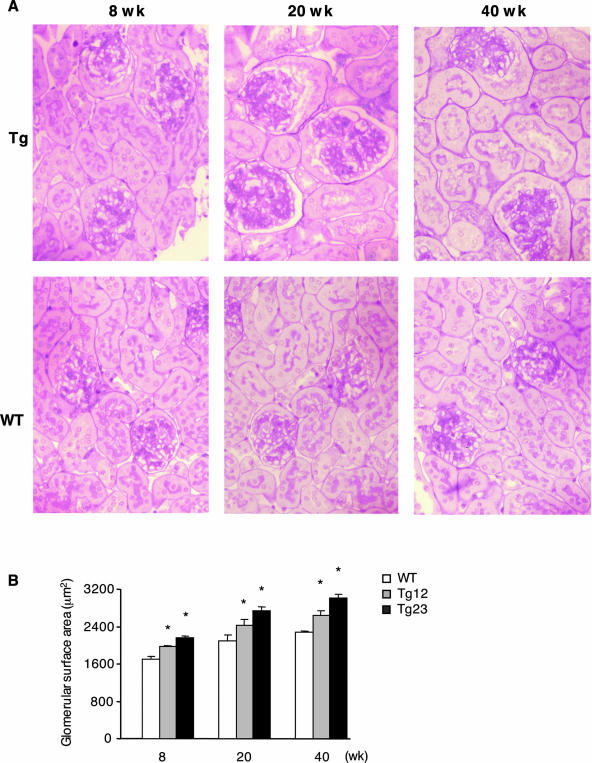

Glomerular Hypertrophy

Glomerular hypertrophy is one of the most characteristic lesions in the initial phase of diabetic nephropathy. The enlargement of the glomerular surface area was apparent by 8 weeks of age and continued thereafter (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Glomerular hypertrophy in ICER Tg mice. A: Representative glomeruli from 8-, 20-, and 40-week-old WT and Tg mice are shown. Kidneys were fixed in methyl Carnoy’s solution, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with PAS. B: Glomerular surface area in PASM-stained sections was measured by Image-Pro Plus. For each mouse, 50 glomeruli were analyzed. Data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.01. N = 6 per each group. Original magnifications, ×200.

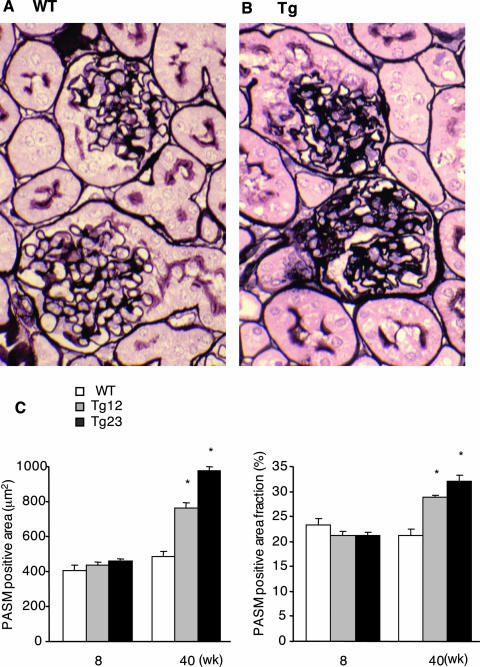

Sclerotic Lesion in Glomeruli

Glomerulosclerosis is one of the most important advanced lesions in diabetic nephropathy. To analyze the extent of glomerulosclerosis, we measured PASM-positive areas. In ICER Tg mice this area increased mainly at the mesangial cell region as early as 20 weeks of age (Figure 2A), suggesting that mesangial extracellular matrix increased by 20 weeks of age. At 40 weeks of age, diffuse mesangial expansion was found, as represented by a 1.5-fold increase (line Tg 23) in PASM-positive area fraction (Figure 3). However, the typical nodular lesions occasionally seen in human diabetic nephropathy, such as Kimmel-Steel-Wilson lesions, were not found.

Figure 3.

Sclerotic lesions in ICER Tg mice. At 40 weeks of age, kidney sections were stained with PASM. Representative glomeruli from WT (A) and Tg (B) mice are shown. C: PASM-positive area was measured by Image-Pro Plus in 50 glomeruli for each mouse. PASM-positive area fraction was calculated by the ratio of PASM-positive area to total glomerular surface area. Data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.01. N = 6 per each group. Original magnifications, ×400.

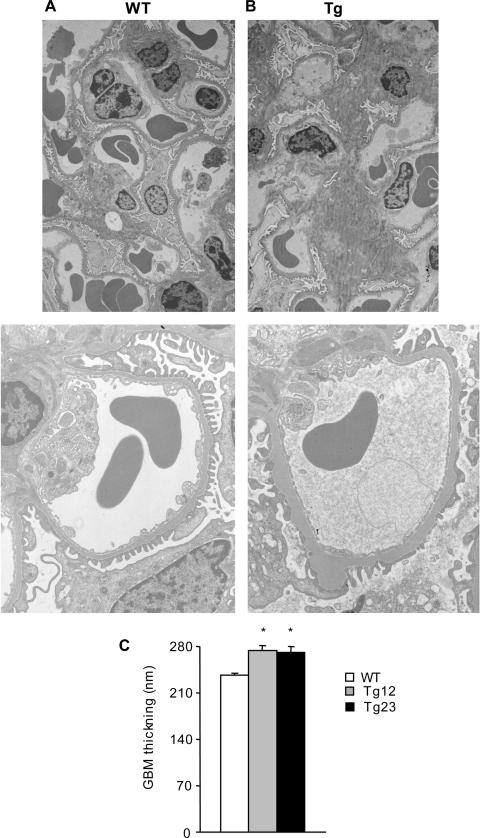

GBM Thickening

GBM thickening, which is another characteristic feature of advanced diabetic nephropathy, was seen in ultrastructural studies at 40 weeks of age (Figure 4). Ultrastructural studies also demonstrated partial foot process fusion.20

Figure 4.

GBM thickening in ICER Tg mice. At 40 weeks of age compared to WT (A), Tg (B) mouse glomeruli have thicker GBM and increased mesangial area. C: Thickness of GBM at 40 weeks of age was measured by the orthogonal intercept method. Data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.01. N = 4 per each group. Original magnifications: ×3000 (A and B, top); ×7000 (A and B, bottom).

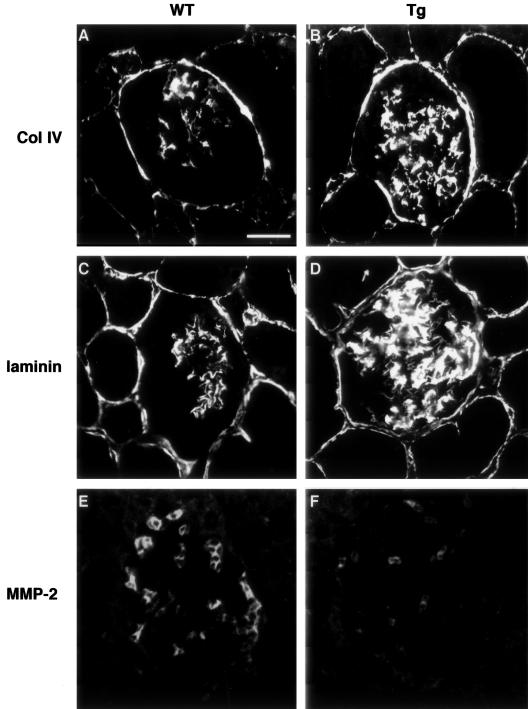

Expression of Extracellular Matrix in Glomeruli

We then determined the glomerular expression of extracellular matrix type IV collagen and laminin, major components of the expanded extracellular matrix in diabetic nephropathy.21 Immunostaining showed that both type IV collagen and laminin proteins were significantly increased mainly in the mesangial areas of ICER Tg mice (Figure 5, B and D). Concerning the degradation of the extracellular matrix, we examined the expression of MMP-2 in this model. MMP-2 expression was decreased in glomeruli of Tg mice (Figure 5F) compared to WT mice. These data suggest that hyperglycemia down-regulated expression of MMP-2, which in turn limited extracellular matrix degradation and exacerbated diabetic glomerulosclerosis.

Figure 5.

The expression of extracellular matrix in glomeruli of ICER Tg mice. Immunohistochemical staining for collagen type IV (A, B) and laminin (C, D) at 40 weeks of age in WT (A, C) and Tg mice (B, D). MMP-2, which is important for degradation of type IV collagen, was also stained. Reduced MMP-2-positive cells at 40 weeks of age in Tg (F) compared to WT mice (E). Scale bar, 25 μm.

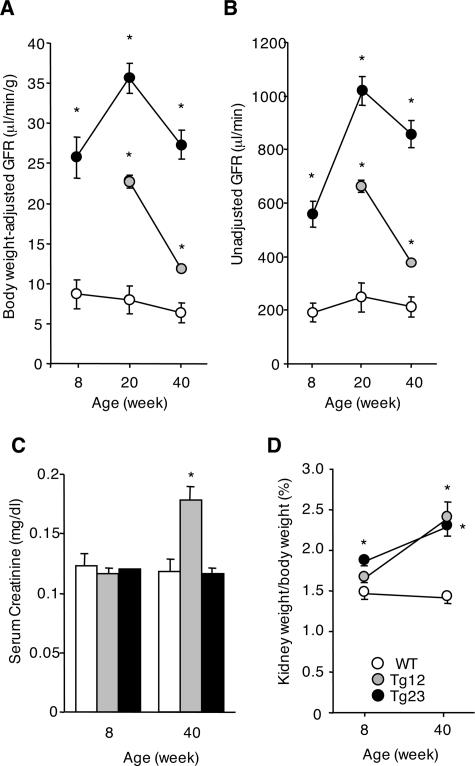

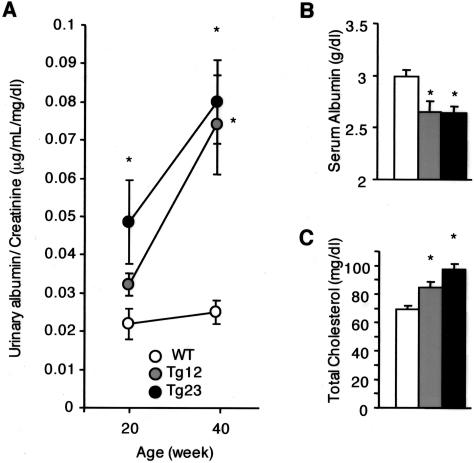

Renal Functional Measurement

Clearance studies are valuable data for the staging of nephropathy, with creatinine clearance (Ccr) a reliable measure of GFR. In this model, Ccr was higher at 8 weeks of age in ICER Tg mice than in WT mice (Figure 6, A and B). The peak of Ccr occurred at 20 weeks of age. At 40 weeks of age, Ccr in ICER Tg mice was lower than at 20 weeks but still greater compared to that in WT mice. Serum creatinine was elevated in Tg 12 mice (Figure 6C). Kidney hypertrophy was also prominent at 8 weeks of age (Figure 6D). The urinary albumin excretion rate in ICER Tg mice was 1.8-fold higher at 20 weeks of age and 2.7-fold higher at 40 weeks of age (line Tg 23) than in WT mice (Figure 7A). Additionally, serum albumin was significantly lower and total cholesterol was higher in ICER Tg mice (Figure 7, B and C).

Figure 6.

Hemodynamic change in ICER Tg mice. A, B: The GFR, calculated as described in Materials and Methods, was increased at 8, 20, and 40 weeks of age in Tg mice. C: Serum creatinine was measured by high performance liquid chromatography. D: Kidney weight/body weight was increased at both 8 and 40 weeks of age in Tg mice. All data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.01. N = 6 per each group.

Figure 7.

Functional change in ICER Tg mice. A: Urinary albumin excretion rate progressively increased with age. B: Serum albumin was decreased in Tg mice at 40 weeks of age. C: Total serum cholesterol was increased at 40 weeks of age. All data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.01. N = 6 per each group.

Discussion

In this study we established a mouse model of diabetes mellitus that stably expresses major clinical and pathological features of human diabetic nephropathy. In this model, we can follow the process of diabetic renal changes that mimic those in humans. First, at 8 weeks of age, GFR was already increased and glomerular hypertrophy was prominent. These changes are important characteristics in the earliest stage of human diabetic nephropathy. Next, at 20 weeks of age, we found a peak in GFR and an increase in the urinary albumin excretion rate. In the histological studies, a discernible increase in the mesangial area could be found. In human kidney biopsy specimens, sclerotic changes are detectable when urine albumin excretion is detected. Therefore, the renal changes at 20 weeks of age in the ICER Tg mice were compatible with the early to middle stages of human diabetic nephropathy. Finally, at 40 weeks of age, mesangial matrix expansion was prominent, showing diffuse glomerular sclerotic lesions. GBM thickening was also diffuse. However, other characteristic diabetic lesions, such as nodular sclerotic lesions or exudative lesions, were not observed. These sclerotic lesions were confirmed by immunohistochemistry for collagen IV and laminin. At this point, GFR had already declined, suggesting that diabetic nephropathy progressed to a more advanced stage and that urinary albumin excretion rate increased enough to cause a nephrotic state with lower serum albumin and higher serum total cholesterol levels.

Because it is important to determine the specificity for the effects of blood glucose levels on renal structural and functional alterations, we analyzed two Tg lines. The transgene was shown to be expressed in pancreatic β cells but not in other organs.14 Furthermore, although the two Tg lines contained different copy numbers of the transgene, all ICER Tg mice had normal blood glucose levels at birth but developed severe diabetes by 2 weeks of age. Therefore, glomerular development of ICER Tg was not affected by the transgene or by hyperglycemia during embryogenesis. This was also suggested by the fact that kidney lesions had normal morphology at 2 weeks of age (data not shown). We also investigated the glomerular number in Tg mice. ICER Tg mice had almost the same glomerular number as WT, indicating that the renal change in Tg was not due to the decrease of glomeruli.

The db/db mouse is perhaps the best characterized and most intensively investigated diabetic mouse model.22 The db/db mouse, a type II diabetes model, has more progressive diabetic lesions than the models described in the introduction, having diffuse expansion of the mesangial matrix. The db gene encodes a point mutation in the leptin receptor, leading to abnormal splicing and defective signaling of the adipocyte-derived hormone leptin.23 Therefore, renal manifestations of this model are affected not only by hyperglycemia but also by other metabolic effects of leptin. Heterozygous iNOS transgenic mice, which develop type I diabetes due to the iNOS-mediated selective destruction of insulin-producing pancreatic β cells, demonstrate advanced glomerulosclerosis by crossbreeding with RAGE transgenic mice.24 However, this model is also modified by RAGE overexpression in vascular cells. In our ICER Tg mice, the severity of kidney lesions seem to be almost equivalent to those of db/db mice, and the kidney manifestations are likely due to hyperglycemia alone. This provides ICER Tg mice with an advantage over db/db mice or iNOS-RAGE double-transgenic mice. Our mice have no obesity or severe emaciation. We, therefore, can investigate the sole effect of hyperglycemia in this model.

In addition, another advantage is that this model shows stable development of hyperglycemia and renal manifestations. Hyperglycemia develops at ∼2 weeks of age and continues throughout life. Because each mouse has nearly identical diabetic renal disease, we can easily analyze histological and functional changes. Further, ICER Tg mice can be maintained without insulin injections.

Diabetic renal changes in ICER Tg mice are slow and progressive, and its manifestations are likely to be better than many models used for studying diabetic nephropathy. Still, the lesion was not as severe as in human diabetic nephropathy because nodular lesions were absent, and there was no severe functional damage by 40 weeks of age. To induce nodular sclerotic or exudative lesions, factors other than hyperglycemia might be necessary. The mice did not develop renal failure at 40 weeks of age probably because of the C57BL/6 background. C57BL/6 mice are known to be resistant to glomerulosclerosis even after 7/8 nephrectomy,23 or even if carrying the oligosyndactyly (Os) mutation gene, compared to other strains such as 129/Sv23 and ROP.25,26 These strain-specific differences might be due to the presence of one rennin gene (Ren-1) in C57BL/6 mice, whereas two copies (Ren-1 and Ren-2) exist in other strains (eg, 129/Sv).27 Further manipulations, such as breeding to different background strains or feeding high-protein diet, are likely to evoke more severe lesions because genetic background and food are important factors that determine susceptibility to glomerulosclerosis in mice.23,28

We also found that MMP-2 expression was reduced in ICER Tg mice. This is compatible to a previous study showing that expression and activity of MMP-2, which is important for the degradation of type IV collagen in mesangial cells, are decreased in C57BL/6 mesangial cells after long-term exposure to high glucose.29 This finding has also been reported in human mesangial cells of type II diabetic patients.30 However, the staining of MMP-2 in this model does not seem to occur in a mesangial pattern. In endothelial cells the expression of MMP-2 has been shown to be increased by high glucose stimulation in vitro.31 Therefore, further study is required to understand the role of MMP-2 in diabetic nephropathy.

ICER Iγ suppresses not only insulin gene transcription but also β-cell replication through the suppression of cyclin A expression.14,15 As a result, islets have reduced β-cell numbers and impaired insulin secretion, leading to chronic hyperglycemia. The unique property of ICER Tg mice is that although their blood glucose levels are extremely high throughout their lives, they survive long enough to develop diabetic nephropathy. This unique property may have played a role in the development of renal lesions similar to the diabetic nephropathy seen in humans.

In humans, sex differences in the prevalence of diabetic microangiopathy have been reported.32 In our Tg mice, the blood glucose levels of female mice were not high enough to develop diabetic nephropathy. Although female Tg mice (F2-F4) had high blood glucose levels at 4 weeks of age, their glucose concentrations gradually decreased, and most female Tg mice showed normal blood glucose levels by 20 weeks of age (data not shown). We are now investigating the cause of this difference.

In summary, we report a novel mouse model of diabetes that displays many features of human diabetic nephropathy. This model should be suitable to study the pathogenesis and the treatment of diabetic nephropathy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hideo Uchiyama (Taigenkai Hospital) for providing mouse kidney sections, Sarah Yasui for excellent technical assistance, Oogi Inada (Kyoto University) for frequent help with mouse care, and Chris Cahill (Joslin Diabetes Center) for confocal microscopy training.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Hidenori Arai, Department of Geriatric Medicine, Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine, 54 Kawahara-cho, Shogoin, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8507, Japan. E-mail: harai@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp; or to Atsushi Fukatsu, Department of Nephrology, Kyoto University, 54 Kawahara-cho, Shogoin, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8507, Japan. E-mail: afukatsu@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (grant-in-aid for Scientific Research and for Creative Scientific Research NP10NPO201); the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (grant for the Research for the Future Program JSPS-RFTF97I00201); the Joslin National Institutes of Health Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center Advanced Microscopy Core; the Diabetes and Wellness Research Foundation; the Yamanouchi Foundation (fellowship and grant to A.I.).

A.I. and K.N. contributed equally to this work.

Current address of A. Inada: Islet Transplantation and Cell Biology, Joslin Diabetes Center, Harvard Medical School, One Joslin Place, Boston, MA 02215; current address of Y. Seino: Kansai Denryoku Hospital, 2-1-7 Fukushima, Fukushima-ku, Osaka 553-0003, Japan.

References

- Krolewski AS, Warram JH, Rand LI, Kahn CR. Epidemiologic approach to the etiology of type I diabetes mellitus and its complications. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1390–1398. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198711263172206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bojestig M, Arnqvist HJ, Hermansson G, Karlberg BE, Ludvigsson J. Declining incidence of nephropathy in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:15–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199401063300103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krolewski M, Eggers PW, Warram JH. Magnitude of end-stage renal disease in IDDM: a 35 year follow-up study. Kidney Int. 1996;50:2041–2046. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasquez MT, Kimmel PL, Michaelis OE., IV Animal models of spontaneous diabetic kidney disease. FASEB J. 1990;4:2850–2589. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.4.11.2199283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tochino Y. The NOD mouse as a model of type I diabetes. Crit Rev Immunol. 1987;8:49–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi T, Hattori M, Agodoa LY, Sato T, Yoshida H, Striker LJ, Striker GE. Glomerular lesions in nonobese diabetic mouse: before and after the onset of hyperglycemia. Lab Invest. 1990;63:204–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen U, Riley SG, Vassiliadou A, Floege J, Phillips AO. Hypertension superimposed on type II diabetes in Goto Kakizaki rats induces progressive nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2003;63:2162–2170. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson JR, Chang K, Tilton RG, Prater C, Jeffrey JR, Weigel C, Sherman WR, Eades DM, Kilo C. Increased vascular permeability in spontaneously diabetic BB/W rats and in rats with mild versus severe streptozocin-induced diabetes. Prevention by aldose reductase inhibitors and castration. Diabetes. 1987;36:813–821. doi: 10.2337/diab.36.7.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokozawa T, Nakagawa T, Wakaki K, Koizumi F. Animal model of diabetic nephropathy. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2001;53:359–363. doi: 10.1078/0940-2993-00203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatz R, Meyer TW, Rennke HG, Brenner BM. Predominance of hemodynamic rather than metabolic factors in the pathogenesis of diabetic glomerulopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:5963–5967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.17.5963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulkes NS, Borrelli E, Sassone-Corsi P. CREM gene: use of alternative DNA-binding domains generates multiple antagonists of cAMP-induced transcription. Cell. 1991;64:739–749. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90503-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inada A, Yamada Y, Someya Y, Kubota A, Yasuda K, Ihara Y, Kagimoto S, Kuroe A, Tsuda K, Seino Y. Transcriptional repressors are increased in pancreatic islets of type 2 diabetic rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;253:712–718. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inada A, Someya Y, Yamada Y, Ihara Y, Kubota A, Ban N, Watanabe R, Tsuda K, Seino Y. The cyclic AMP response element modulator family regulates the insulin gene transcription by interacting with transcription factor IID. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21095–21103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.30.21095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inada A, Hamamoto Y, Tsuura Y, Miyazaki J, Toyokuni S, Ihara Y, Nagai K, Yamada Y, Bonner-Weir S, Seino Y. Overexpression of inducible cyclic AMP early repressor inhibits transactivation of genes and cell proliferation in pancreatic β cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:2831–2841. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.7.2831-2841.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inada A, Weir GC, Bonner-Weir S. Induced ICER Iγ down-regulates cyclin A expression and cell proliferation in insulin-producing β cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;329:925–929. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai K, Arai H, Yanagita M, Matsubara T, Kanamori H, Nakano T, Iehara N, Fukatsu A, Kita T, Doi T. Growth arrest-specific gene 6 is involved in glomerular hypertrophy in the early stage of diabetic nephropathy. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18229–18234. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213266200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalups RK. The Os/+ mouse: a genetic animal model of reduced renal mass. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:F53–F60. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.264.1.F53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen EB, Gundersen HJ, Osterby R. Determination of membrane thickness distribution from orthogonal intercepts. J Microsc. 1979;115:19–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1979.tb00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockelman MG, Lorenz JN, Smith FN, Boivin GP, Sahota A, Tischfield JA, Stambrook PJ. Chronic renal failure in a mouse model of human adenine phosphoribosyltransferase deficiency. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:F154–F163. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.275.1.F154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwar YS, Rosenzweig LJ, Linker A, Jakubowski ML. Decreased de novo synthesis of glomerular proteoglycans in diabetes: biochemical and autoradiographic evidence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:2272–2275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.8.2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iehara N, Takeoka H, Yamada Y, Kita T, Doi T. Advanced glycation end products modulate transcriptional regulation in mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 1996;50:1166–1172. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma K, McCue P, Dunn SR. Diabetic kidney disease in the db/db mouse. Am J Physiol. 2003;284:F1138–F1144. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00315.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma LJ, Fogo AB. Model of robust induction of glomerulosclerosis in mice: importance of genetic background. Kidney Int. 2003;64:350–355. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Kato I, Doi T, Yonekura H, Ohashi S, Takeuchi M, Watanabe T, Yamagishi S, Sakurai S, Takasawa S, Okamoto H, Yamamoto H. Development and prevention of advanced diabetic nephropathy in RAGE-overexpressing mice. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:261–268. doi: 10.1172/JCI11771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito C, He CJ, Striker GE, Zalups RK, Striker LJ. Nature and severity of the glomerular response to nephron reduction is strain-dependent in mice. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:891–897. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65336-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C, Esposito C, Phillips C, Zalups RK, Henderson DA, Striker GE, Striker LJ. Dissociation of glomerular hypertrophy, cell proliferation, and glomerulosclerosis in mouse strains heterozygous for a mutation (Os) which induces a 50% reduction in nephron number. J Clin Invest. 1996;197:1242–1249. doi: 10.1172/JCI118539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Hummler E, Nussberger J, Clement S, Gabbiani G, Brunner HR, Burnier M. Blood pressure, cardiac, and renal responses to salt and deoxycorticosterone acetate in mice: role of Renin genes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1509–1516. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000017902.77985.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng F, Striker GE, Esposito C, Lupia E, Striker LJ. Strain differences rather than hyperglycemia determine the severity of glomerulosclerosis in mice. Kidney Int. 1998;54:1999–2007. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornoni A, Striker LJ, Zheng F, Striker GE. Reversibility of glucose-induced changes in mesangial cell extracellular matrix depends on the genetic background. Diabetes. 2002;51:499–505. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Prete D, Anglani F, Forino M, Ceol M, Fioretto P, Nosadini R, Baggio B, Gambaro G. Down-regulation of glomerular matrix metalloproteinase-2 gene in human NIDDM. Diabetologia. 1997;40:1449–1454. doi: 10.1007/s001250050848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Death AK, Fisher EJ, McGrath KC, Yue DK. High glucose alters matrix metalloproteinase expression in two key vascular cells: potential impact on atherosclerosis in diabetes. Atherosclerosis. 2003;168:263–269. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(03)00140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail N, Becker B, Strzelczyk P, Ritz E. Renal disease and hypertension in noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Kidney Int. 1999;55:1–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]