Abstract

To elucidate genes important in development or repair of asbestos-induced lung diseases, gene expression was examined in mice after inhalation of chrysotile asbestos for 3, 9, and 40 days. We identified changes in the expression of genes linked to proliferation (cyclin B2, CDC20, and CDC28 protein kinase regulatory subunit 2), inflammation (CCL9, CCL6, complement component 1, chitinase3-like 3, TNF superfamily member 10, and IL-1B), and matrix remodeling (MMP12, MMP3, integrin αX, and cathepsins K, Z, B, and S). The most highly induced gene at all time points was mclca3 (gob5), a putative calcium-activated chloride channel involved in the regulation of mucus production and/or secretion. Using histochemistry, we demonstrated accumulation of mucus and increased mClca3 protein in the bronchiolar epithelium of asbestos-exposed mice at all time points but peaking at 9 days. Cytokine levels (interleukin-1β, interleukin-4, interleukin-6) in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid also increased at 9 days, suggesting Th2-mediated immunity may play a role in asbestos-induced mucus production. In contrast, levels of cathepsin K, a potent elastase, increased between 3 and 40 days at both the mRNA and protein levels, localizing primarily in CD45-positive leukocytes and interstitial cells. Identification of genes involved in lung injury and remodeling after asbestos exposure could aid in defining mechanisms of airborne particulate-induced disease and in developing therapeutic strategies.

Occupational exposure to airborne asbestos, a family of naturally occurring fibrous minerals, is associated with the development of lung cancers, malignant mesotheliomas, and pleural and pulmonary fibrosis (asbestosis).1–3 Of the six types of asbestos fibers, chrysotile is the most widely used, accounting for >95% of asbestos-containing products used historically. Epidemiological and animal studies have shown that chrysotile asbestos fibers are both carcinogenic and fibrogenic.4 There is currently no cure for asbestos-related cancers and fibroproliferative disease, and treatment options are relatively ineffective.5 Although efforts have been made to elucidate genetic alterations,4 signaling pathways,6 and cytokine profiles7 important in asbestos-related cell responses, the molecular events involved in disease development and progression by these fibers are still poorly understood.

The pathogenesis of asbestosis has been studied throughout the past few decades, and the chronology of events leading to fibrogenesis have been well characterized.5 In rats, a more susceptible strain than the mouse to particle-induced diseases, chronic exposures to asbestos fibers lead to prominent fibrosis and less frequently, lung tumors. In a murine inhalation model, epithelial cell proliferation, inflammation, and fibrogenesis occur sequentially,8 but how these events trigger lung remodeling is unclear.

Many of the pathogenic effects of asbestos may stem from the ability of fibers to induce and/or activate growth and chemotactic factors.9 These events may be mediated by phagocytosis of long asbestos fibers by epithelial and mesothelial cells and/or macrophages or fiber-catalyzed generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that stimulates signaling pathways leading to injury, growth, and matrix production or degradation.10 Recent studies suggest that depletion of antioxidants contributes to asbestos-associated cell signaling and transcription factor regulation by ROS,11 and administration of iron chelates or antioxidant enzymes ameliorates asbestos-induced inflammation and fibrosis in rats.12 Other redox-associated posttranscriptional pathways, including signaling via mitogen-activated protein kinase or the nuclear factor-κB pathways also play a role in asbestos-induced proliferation, survival, and chemokine production by epithelial cells.13,14

The goal of this study was to determine chrysotile asbestos-induced gene changes in lungs of mice inhaling chrysotile asbestos using a robust microarray analysis (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). We determined the kinetics of gene changes occurring in the lungs at 3, 9, and 40 days, time points representing the advent of epithelial cell proliferation, peak inflammation, and the evolution of fibrotic lesions, respectively. In addition to revealing a number of genes that may be causally linked to mitogenesis, inflammation, and lung remodeling, we report excessive mucus production by asbestos fibers and striking induction (>80-fold) of mclca3 (gob5), a putative calcium-activated chloride channel thought to regulate mucus production and/or secretion,15 which was epithelial cell-specific. In addition to playing a role in fiber clearance in asbestos-associated lung diseases, the induction of mucus production by chrysotile and other airborne particle pollutants may contribute to exacerbation of asthma or bronchitis, a recent area of public health concern.16,17

Materials and Methods

Animals and Inhalation Model

C57BL/6 (8 to 12 weeks) male mice (Charles River Laboratories, Inc., Wilmington, MA), a strain susceptible to asbestos, were maintained at the University of Vermont Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care accredited Animal Inhalation Facility before the experiment. Animals (n = 3/group/time point for microarray studies) were placed in an inhalation chamber and exposed to ambient air or 5.0 mg/m3/air of chrysotile asbestos (National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences reference sample previously characterized for fiber length and composition15) for 3, 9, and 40 days (6 hours/day; 5 days/week). A third group of mice was exposed to 5.0 mg/m3/day fine titanium dioxide (TiO2) (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH), a nonpathogenic control particle, for 3 days (n = 3/group). Additional mice (n = 5 to 6/group/time point) were used for histopathology and immunohistochemistry. Animals were offered food and water ad libitum during the exposure period. After euthanasia of mice with sodium pentobarbital intraperitoneally, the lungs were perfused and then inflated under pressure with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The left lobes were tied off, excised, and placed in 4% paraformaldehyde for histology and immunohistochemistry, and the right lobes were excised, minced, and placed in RNA later solution (Ambion, Austin, TX) for isolation of RNA. All animal protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT.

RNA Preparation

Lung tissue was stored in RNA later solution before processing following the manufacturer’s protocol. To isolate RNA, ∼40 to 80 mg of lung tissue was homogenized in Trizol and extracted with chloroform. The RNA was precipitated with isopropanol, washed with 75% ethanol, and further purified using the RNeasy system (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The isolated RNA was further treated with DNase I (Ambion). The quantity was determined by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm, and quality assessed on a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA).

Gene Expression

Biotin-labeled RNA was produced from 5 μg of total RNA as described previously.6 Briefly, double-stranded cDNA was created using a one-cycle synthesis reaction followed by biotin labeling of anti-sense cRNA. A hybridization mixture containing the fragmented cRNA, probe array control (Affymetrix), bovine serum albumin, and herring sperm DNA was prepared and hybridized to the probe array, mouse genome U74Av2 (Affymetrix). The array was then washed and bound biotin-labeled cRNA was detected with a streptavidin-phycoerythrin conjugate. Subsequent signal amplification was performed with a biotinylated anti-streptavidin antibody. The washing and staining procedures were automated using the Affymetrix fluidics station. Each probe array was scanned twice (Hewlett-Packard GeneArray Scanner, Palo Alto, CA), the images were overlaid, and the average intensities of each probe cell were compiled.

Validation of Array Expression Data by Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (QRT-PCR) and Ribonuclease Protection Assay (RPA)

Total RNA (3 μg) was reverse-transcribed with random primers using the avian myeloblastosis virus reverse-transcriptase kit (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the recommendations of the manufacturer. To quantify gene expression, cDNA was amplified for various gene targets by QRT-PCR using the 7700 sequence detector (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA). Reactions contained 1× TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix, 900 nmol/L forward and reverse primers, and 200 nmol/L TaqMan probes. All primers and probes used were purchased as Assays on Demand; clca3 = no. Mm00489959 m1, cathepsin K = no. Mm00484036 m1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Thermal cycling was performed using 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute. Expression assays for each gene were run in duplicate, normalized to the HPRT housekeeping gene (no. Mm00446968 m1), and expressed as fold change over control. Expression levels of interleukin (IL)-1β were validated using RPAs described previously (Riboquant; PharMingen, San Diego, CA).18 Briefly, 5 μg of total RNA was hybridized to radiolabeled anti-sense RNA composed from a custom template containing IL-1β, and the ribosomal protein (L32) housekeeping gene. After hybridization, the single-strand RNA was digested with RNases and proteinase K. The RNA duplexes were resolved by electrophoresis in standard 5% acrylamide/urea sequencing gels. After drying, autoradiograms of gels were quantitated using a phosphorimager (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Data were normalized to expression of L32, and results from two to three lanes per group per time point were plotted as fold change in relative units compared to control (mean ± SE).

Histopathology

After postfixation in 4% paraformaldehyde, lungs were fixed and embedded in paraffin as previously described.8 Lung sections (5 μm) were used for immunohistochemistry or stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Masson’s trichrome technique, or Alcian blue/periodic acid-Schiff (PAS). All lung sections were blindly scored for inflammation (H&E) and collagen deposition (Masson’s trichrome) by a certified pathologist (K.J.B.). The epithelium of distal bronchioles (≤800 μm perimeter) in lung sections stained with Alcian blue/PAS were scored semiquantitatively. The percentage of cells expressing Alcian blue/PAS-positive epithelial cells per total percentage of epithelial cells in individual distal bronchioles (four to seven per slide on each of two lung sections per mouse) was scored using a blind coding system.

Immunohistochemistry

To measure cell proliferation, sections were probed with Ki-67, a marker of cycling cells.19 Lung sections were deparaffinized in xylene (2 × 15 minutes) and rehydrated in a graded ethanol series (95 to 50%). Slides were rinsed in water and placed in 1× DAKO antigen retrieval solution (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) and incubated at 95 to 99°C for 40 minutes. Slides were cooled and washed 2 × 5 minutes in 1× Tris-buffered saline (TBS), incubated with 1 to 2 drops of peroxidase block (DakoCytomation) for 30 minutes in a humidified chamber, and washed again in 1× TBS for 5 minutes. Slides were then blocked with 1 to 2 drops of serum-free protein block (DakoCytomation) for 30 minutes in a humidified chamber. Monoclonal rat anti-mouse Ki-67 antibody (DakoCytomation) was diluted 1:25 in 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS and applied to each slide, which was incubated overnight in a humidified chamber at 4°C. The next day, slides were washed 3 × 3 minutes in 1× TBS, and incubated 1 hour at room temperature with a biotinylated anti-rat IgG antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) diluted in PBS (1:400). Slides were then washed in TBS and treated with 1 to 2 drops of streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase for 30 minutes. A solution containing 3,3′diaminobenzidine substrate (500 μl of buffered substrate plus 50 μl of 3,3′diaminobenzidine chromogen, DakoCytomation) was applied to each slide for 5 minutes. Slides were then washed with 1× TBS, counterstained with hematoxylin, fixed using Aqua-Poly/Mount (Polysciences Inc., Warrington, PA), and coverslipped.

To detect mClca3 protein, an avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex method was used. After deparaffinizing of 5 μmol/L sections in xylene and rehydration in isopropanol and graded ethanol, the sections were microwaved for 15 minutes (700 W) in 10 mmol/L citric acid (pH 6.0). Endogenous peroxidase activity was inhibited by incubating the slides with 70% methanol containing 0.5% H2O2, followed by washes in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS/Tween 20) and blocking in PBS/Tween 20 containing 20% heat-inactivated normal goat serum. After repeated washes, the sections were incubated with antibody α-p3b1 diluted 1:5000 in PBS/Tween 20 containing 1% bovine serum albumin in a humidified chamber at 4°C overnight. The generation and specificity of the antibody were described previously.15 Sections were washed in PBS/Tween 20 and incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulins (5 μg/ml, Vector Laboratories) diluted in PBS/Tween 20, followed by repeated washes in PBS/Tween 20. Color was developed for 30 minutes using freshly prepared avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex solution (Vectastain Elite ABC kit, Vector Laboratories) diluted in PBS, followed by repeated washes in PBS, and rinsing in water. The slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated through ascending graded ethanol, cleared in xylene, and coverslipped before examination by light microscopy.

For triple-immunofluorescence staining of cathepsin K, Clara cell secretory protein (CCSP), and CD45, sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and boiled in Dako solution as stated above. Sections were blocked in 10% normal donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, PA) diluted 1:1 with PBS for 1 hour followed by incubation in a primary antibody cocktail [rabbit polyclonal CCSP (a kind gift from Dr. Barry Stripp, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA) at 1:15,000; rat monoclonal CD45 (Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) at 1:400; and goat polyclonal cathepsin K (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at 1:50 overnight] at 4°C in a humidified chamber. Sections were washed in PBS and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with a secondary antibody cocktail (Alexa Fluor donkey anti-rabbit 647, Alexa Fluor donkey anti-rat 488, Alexa Fluor donkey anti-goat 568; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). After a final wash in PBS, slides were coverslipped using AquaPoly/Mount (Polysciences Inc.) and viewed with a Bio-Rad MRC 1024 confocal scanning laser microscope (Bio-Rad). Images were captured in sequential mode using Lasersharp 2000 software.

Bio-Plex Analysis of Bronchoalveolar Lavage Cytokine and Chemokine Concentrations

To quantify cytokine and chemokine levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), a multiplex suspension protein array was performed using the Bio-Plex protein array system and a mouse cytokine 18-plex panel (Bio-Rad). This method of analysis is based on Luminex technology and simultaneously measures IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-13 at the protein level. Briefly, anti-cytokine/chemokine antibody-conjugated beads were added to individual wells of a 96-well filter plate and adhered using vacuum filtration. After washing, 50 μl of prediluted standards (range, 32,000 pg/ml to 1.95 pg/ml) or BALF (n = 6/group) was added, and the filter plate shaken at 300 rpm for 30 minutes at room temperature. Thereafter, the filter plate was washed, and 25 μl of prediluted multiplex detection antibody was added for 30 minutes. After washing, 50 μl of prediluted streptavidin-conjugated phycoerythrin was added for 10 minutes followed by an additional wash and the addition of 125 μl of Bio-Plex assay buffer to each well. The filter plate was analyzed using the Bio-Plex protein array system, and concentrations of each cytokine and chemokine were determined using Bio-Plex Manager Version 3.0 software. Data are expressed as pg cytokine/ml of BALF.

Statistical Analyses

Raw expression data obtained after MGU74Av2 DNA chip scanning (Gene Chip scanner, Affymetrix) were scaled and corrected for saturation using Affymetrix Microarray Suite 5.0 software. The absolute analysis determined whether transcripts on the array were detected in the sample (present, marginal, or absent). Comparative analysis between expression profiles for all samples was performed with Gene Spring software version 6.0 (Silicongenetics, Redwood, CA) by using the Cross-gene-error-model. Gene expression data were normalized in three ways: per chip normalization (all expression data on the chip normalized to the 50th percentile of all values); per gene normalization (data for a given gene normalized to the median expression level of that gene across all samples); and per gene normalized to specific sample (all genes normalized with respect to the control samples). The expression profiles of all samples were compared using one-way analysis of variance (significance level set at P < 0.05) with no multiple testing correction. Functional annotations were provided by GO Biological Process (http://www.affymetrix.com/analysis/index.affx). All validation and immunohistochemistry experiments were performed in duplicate (n = 3 per group per time point), and cytokine assays contained n = 6 per group. Statistical analysis included analysis of variance with the Student-Newman-Keuls procedure for adjustment of multiple pair-wise comparisons between treatment groups. Differences with P ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Inhalation of Chrysotile Asbestos Induces Epithelial Cell Proliferation, Inflammation, and Peribronchiolar Fibrosis

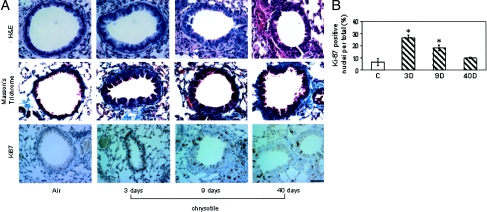

In earlier studies,8 focal thickening at alveolar duct junctions was observed at 30 days after initiation of exposure to chrysotile asbestos without statistical increases in lung hydroxyproline, an indicator of collagen synthesis. Here a more protracted inhalation exposure (40 days) was performed to demonstrate prominent fibrotic lesion development. Figure 1A shows representative histological changes in asbestos-exposed lungs at 3, 9, and 40 days. H&E-stained sections revealed distal bronchiolar epithelial hyperplasia with increased Ki-67-positive cells at 3 days, a time point corresponding to peak incorporation of 5′-bromodeoxyuridine in previous studies.8 Peak levels of Ki-67-positive bronchiolar epithelial cells were observed after 3 days of asbestos exposure with the number of Ki-67-positive cells returning to sham levels by 40 days (Figure 1B). The histopathology and Ki-67 expression in lungs of mice exposed to TiO2 for 3 days were unremarkable (data not shown). Infiltration of immune cells was quantified on H&E-stained sections, and shown to be maximal at 9 days, observations consistent with those reported for asbestos previously.8 By 40 days of exposure to chrysotile asbestos, staining of collagen with Masson’s trichrome showed the development of peribronchiolar fibrosis. Overall, these results are consistent with peak lung epithelial cell proliferation, immune cell influx, and airway fibrosis at 3, 9, and 40 days, respectively, as a result of inhaled asbestos fibers.

Figure 1.

Bronchiolar epithelial hyperplasia, peribronchiolar fibrosis, and proliferation in mice exposed to chrysotile asbestos for 3, 9, and 40 days. A, top: H&E-stained lung sections showing hyperplasia of the epithelium at 3 and 9 days. In contrast to sham animals, the epithelium is more columnar and crowded. Middle: Lung sections showing peribronchiolar fibrosis at 40 days by increased staining of collagen with Masson’s trichrome stain. Bottom: Ki67-stained lung sections showing peak proliferation of bronchiolar epithelial cells at 3 days. B: Quantitation of Ki-67 in bronchiolar epithelial cells at 3, 9, and 40 days. All values are expressed as percent cells positive for Ki-67 labeling. *P ≤ 0.05 versus sham. Scale bar, 50 μmol/L.

Microarray Analysis

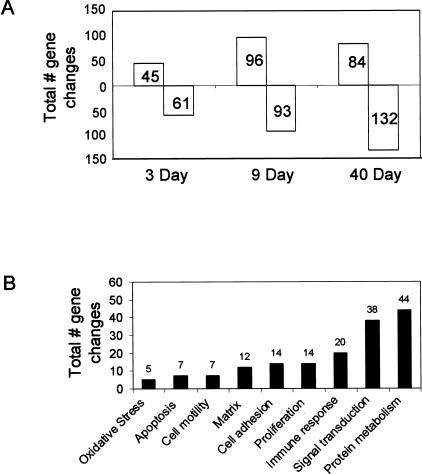

Using oligoarray analysis, the expression of 312 genes of a total of ∼12,000 was significantly (P < 0.05) increased or decreased (twofold or greater) by asbestos at one or more of the time points (3, 9, or 40 days). The total number of gene expression changes increased throughout time (Figure 2A). Only five genes were significantly up-regulated after 3 days of exposure to TiO2, a nonfibrogenic control particle:20 chemokine (C-C) receptor 2 (CCR2), up-regulated during skeletal muscle growth 5, mclca3 (gob5), IL-1β, and calgranulin A. The first four genes were induced to a lesser extent in comparison to chrysotile-exposed lungs, whereas the expression of calgranulin A was not affected by asbestos. No genes were significantly down-regulated by TiO2. Classification by functional ontology shows that many of the genes affected by chrysotile are involved in protein metabolism, signal transduction, oxidative stress, immune function, proliferation, cell adhesion, and matrix remodeling, among others (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

A: Total number of significant (P < 0.05) gene changes ≥2× compared to air-exposed animals obtained in whole lung tissue by microarray analysis at 3, 9, and 40 days of chrysotile asbestos exposure. B: Total number of significant (P < 0.05) gene changes ≥2× in whole lung tissue that were categorized by biological process.

The 10 most significantly (P < 0.05) affected genes in terms of fold changes in expression when compared to sham control lungs are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Some of these genes (Table 1) were induced at all time points, including mclca3, matrix metalloproteinase 12 (MMP12), and chemokine ligand 9 (CCL9). Mclca3 was the most highly induced gene at all time points. The expression of this gene exceeded control levels by ∼80-fold, rendering it the most highly up-regulated gene in our study, and one of three selected for further validation and characterization. Although mclca3 was also up-regulated (fourfold) by TiO2 at 3 days, the induction was minimal compared to the levels achieved by chrysotile (data not shown).

Table 1.

Genes that Were Most Highly Up-Regulated by Chrysotile Asbestos

| Fold change | |

|---|---|

| 3 days | |

| Clca3 (Gob5) | 79.2 |

| Anterior gradient 2 (Xenopus laevis) | 14.1 |

| Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 9 | 4.7 |

| High-mobility group box 2 | 4.4 |

| CDC28 protein kinase regulatory subunit 2 | 3.7 |

| RIKEN cDNA 2700084L22 gene | 3.6 |

| Matrix metalloproteinase 12 | 3.5 |

| Cholesterol 25-hydroxylase | 3.3 |

| Mus musculus SPRR2A gene | 3.1 |

| Chemokine (C-C) receptor 2 | 2.9 |

| 9 days | |

| Clca3 (Gob5) | 76.3 |

| Matrix metalloproteinase 12 | 39.3 |

| Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 9 | 15.3 |

| Sox4 | 9.3 |

| Translocating chain-associating membrane protein 1 | 7.8 |

| Cholesterol 25-hydroxylase | 7.3 |

| Immunoglobulin-joining chain | 6.0 |

| IQ motif containing GTPase activating protein 1 | 6.0 |

| Cathepsin K | 5.9 |

| SKI-interacting protein | 5.8 |

| 40 days | |

| Clca3 (Gob5) | 73.8 |

| Matrix metalloproteinase 12 | 18.7 |

| Immunoglobulin-joining chain | 15.3 |

| Secreted phosphoprotein 1 | 9.5 |

| Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 9 | 8.4 |

| Translocating chain-associating membrane protein 1 | 8.3 |

| Cathepsin K | 7.2 |

| Mus musculus isolate C5–12 anti-GBM immunoglobulin κ chain-variable region mRNA, partial cds | 7.1 |

| Mus musculus 24p3 gene | 6.8 |

| Plexin B2 | 6.6 |

Table 2.

Genes that Were Most Significantly Down-Regulated by Chrysotile Asbestos

| Fold change | |

|---|---|

| 3 days | |

| Mus musculus-transcribed sequence with strong similarity to protein sp:Q05516Z145_HUMAN Zinc finger protein | 7.69 |

| Carboxylesterase 3 | 2.78 |

| Platelet-derived growth factor receptor, α polypeptide | 2.78 |

| Bone morphogenetic protein 6 | 2.78 |

| Thrombomodulin | 2.78 |

| Dipeptidase 1 | 2.70 |

| Tensin-like C1 domain-containing phosphatase | 2.70 |

| Hydroxysteroid 11-β dehydrogenase 1 | 2.54 |

| Lipocalin 7 | 2.50 |

| Flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 | 2.50 |

| 9 days | |

| Mus musculus-transcribed sequence with strong similarity to protein sp:Q05516Z145_HUMAN Zinc finger protein | 4.55 |

| Bone morphogenetic protein 6 | 4.17 |

| Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 6 | 3.70 |

| Flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 | 3.70 |

| Endoglin | 3.70 |

| Protocadherin α 6 | 3.57 |

| Platelet-derived growth factor receptor, α polypeptide | 3.57 |

| Membrane-spanning 4-domains, subfamily A, member 4D | 3.33 |

| Glutathione S-transferase, α3 | 3.23 |

| Tensin-like C1 domain-containing phosphatase | 3.13 |

| 40 days | |

| Mus musculus cDNA clone IMAGE:1079339 | 5.00 |

| Hydroxysteroid 11-β dehydrogenase 1 | 4.55 |

| Myosin, light polypeptide 4, alkali; atrial, embryonic | 3.85 |

| FMS-like tyrosine kinase 1 | 3.85 |

| Platelet-derived growth factor receptor, α polypeptide | 3.85 |

| Microtubule-associated protein tau | 3.45 |

| Osteoglycin | 3.45 |

| AV366654 RIKEN full-length mus musculus cDNA clone 8430422J05 | 3.45 |

| Bone morphogenetic protein 6 | 3.45 |

| Microtubule-associated protein tau | 3.33 |

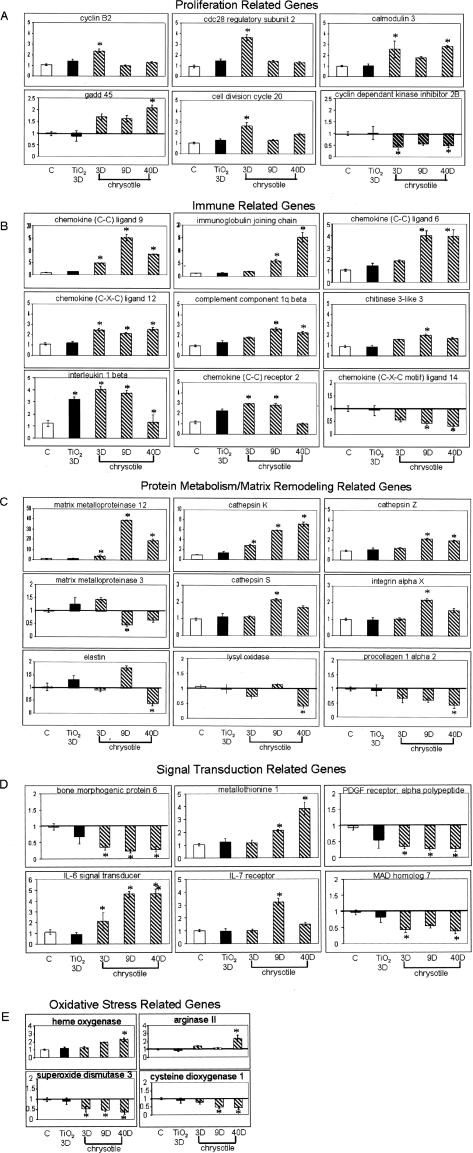

Genes that were down-regulated at all time points (Table 2) include bone morphogenic protein (BMP) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor. Other genes were transiently induced or repressed by chrysotile at various time points. The expression profiles of the most significantly altered genes involved in proliferation, immune response, matrix remodeling, signal transduction, and oxidative stress are depicted in Figure 3, A to E.

Figure 3.

Individual profiles of gene changes obtained by microarray within various subgroups based on biological process in whole lung tissue of mice exposed to air (white bars), TiO2 for 3 days (black bars), or chrysotile asbestos for 3, 9, and 40 days (cross-hatched bars). All values are expressed as fold change in comparison to air-exposed mice. *P < 0.05 and ≥2×. A: Proliferation; B: immune system; C: protein metabolism/matrix remodeling; D: signal transduction; E: oxidative stress.

Genes Associated with Proliferation

Thirteen genes associated with cellular proliferation were found to be significantly altered by asbestos, and changes in expression throughout time for a subset of these genes is shown in Figure 3A. Many of these genes are involved in cell-cycle regulation and were most highly induced at 3 days including cyclin B2, cell division cycle 20 homolog, and CDC28 protein kinase regulatory subunit 2. In addition, an inhibitor of the cell cycle (p15) was repressed throughout the duration of the experiment.

Genes Involved in the Immune Response

A total of 20 significant gene changes were observed in this category, which included cytokines, chemokine receptors, and complement components. Gene expression data for some of these genes are shown in Figure 3B. Many of these genes [CCL9 (MIP-1 gamma), CCL6, complement component 1, chitinase3-like 3, and tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily member 10, IL-1β] were up-regulated by chrysotile with maximal expression occurring at 9 days, a time point of peak inflammation, with expression sustained for 40 days.

Genes Involved in Matrix Remodeling

Based on functional ontology analysis, significant changes in the expression of 12 genes that play a role in matrix remodeling were observed. Many of these genes are involved in remodeling of the extracellular matrix (ECM) by metabolizing individual matrix components. Genes known to be involved in matrix remodeling such as MMP12, MMP3, integrin αX, and the cathepsins K, Z, B, and S were up-regulated by chrysotile (Figure 3C). The altered expression of these genes by asbestos occurred at 9 days. With the exception of MMP12 and cathepsin K that were significantly increased at all time points, elastin and procollagen type I α2, were down-regulated at 40 days.

Genes Involved in Signal Transduction

A total of 57 genes involved in signal transduction pathways were altered. Figure 3D shows the changes in expression throughout time for six of these genes. Three of the genes down-regulated by chrysotile included BMP 6, PDGF receptor, and MAD 7. Two remaining genes were induced at 9 and 40 days (metallothionein 1, IL-6 signal transducer), and IL-7 receptor was induced transiently at 9 days only.

Redox-Related Gene Expression

Of the four genes related to oxidative stress depicted in Figure 3E, heme oxygenase and arginase II were up-regulated significantly at 40 days by asbestos. Extracellular superoxide dismutase expression was repressed at 3, 9, and 40 days, whereas cysteine dioxygenase was down-regulated at 9 and 40 days (Figure 3E).

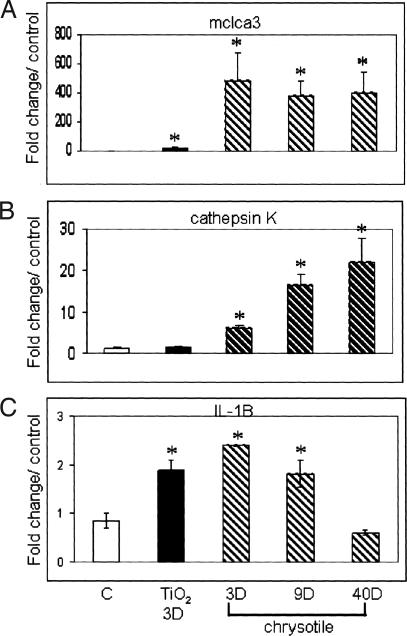

Validation of Gene Expression by QRT-PCR and RPA

Using QRT-PCR, we validated the expression of two genes, cathepsin K and mclca3. We also validated the expression of IL-1β by RPA because it has been shown to increase mucus production in bronchial epithelial cells in vitro.21 Figure 4 shows the fold changes in expression levels for mclca3, cathepsin K, and IL-1β in comparison to control levels. In all three cases, these expression patterns correlated to those obtained by microarray analysis.

Figure 4.

Validation of microarray gene expression data for mclca3 (A), cathepsin K (B), and IL-1β (C) by QRT-PCR (mclca3 and cathepsin K) and RPA (IL-1β) analysis. All values were normalized to HPRT or L32 housekeeping genes and expressed as fold change compared to air controls. *P < 0.05 and ≥2×.

Cathepsin K Is Present in Cells Expressing CD45 and the Interstitium, and Minimally Expressed in the Bronchiolar Epithelium

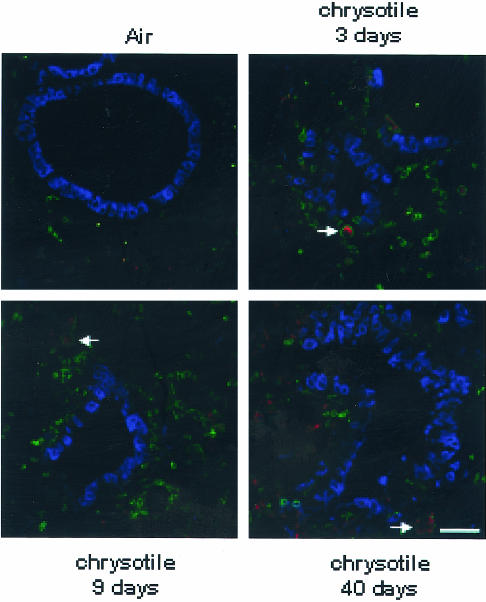

Triple-fluorescence labeling for cathepsin K, CD45 (a marker for leukocytes), and CCSP (a marker for Clara cells) on lung sections from sham and asbestos-exposed mice was used to determine the cellular localization of cathepsin K. Figure 5 shows increased immunofluorescence for cathepsin K at 3, 9, and 40 days, time points correlating with increased levels of mRNA observed by microarray and QRT-PCR. In addition, the majority of cathepsin K was localized to CD45-positive cells (Figure 5, arrow) and cells in the interstitium. Minimal co-localization of cathepsin K with CCSP in the bronchiolar epithelium was observed.

Figure 5.

Cathepsin K is localized to the interstitial region of the lung and within CD45-positive cells. Lung sections of animals exposed to air and chrysotile asbestos for 3, 9, and 40 days were triple labeled with CCSP (blue), CD45 (green), and cathepsin K (red) using immunofluorescence and imaged by confocal scanning laser microscopy. Cathepsin K co-localizes with some CD45-positive cells (arrow), but only reacts minimally with the bronchiolar epithelium (CCSP). There is a significant increase in the quantity of cathepsin K immunostaining from 3 to 40 days in comparison to the air controls. Scale bar, 50 μmol/L.

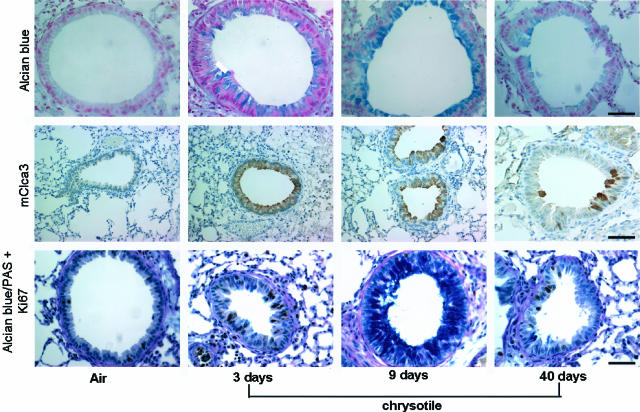

Detection of Mucus and mClca3 Protein in Distal Bronchiolar Epithelium

Because mclca3 was the most highly up-regulated gene in our study, we used immunohistochemistry and Alcian blue/PAS staining to determine whether induction of this gene resulted in excessive production of mucus in distal bronchiolar epithelial cells, sites of proliferation, and accumulation of asbestos fibers after inhalation. The data presented in Figures 6 and 7, A and B, show that mucus production, as revealed by Alcian blue/PAS-positive cells, is enhanced in the distal bronchiolar epithelium by 3 days, peaks at 9 days, and subsides by 40 days of exposure to asbestos. mClca3 protein was also localized to the bronchiolar epithelium, and trends of protein expression paralleled mucus production throughout time. The cellular localization of mclca3 was more apical at 9 days in comparison to the rather diffuse cytoplasmic staining at 3 days. To determine whether mucus-producing cells had the capability to traverse the cell cycle, sections were co-stained with Ki-67 and Alcian blue/PAS for light microscopy. Figures 6 and 7C show that co-localization of Ki-67 in mucin-producing cells was rarely observed.

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemistry showing that asbestos induces mClca3 and mucus production in the bronchiolar epithelium in nonproliferating cells. Lung sections stained with Alcian blue (top) and an antibody to mClca3 (middle) showing increased mucus production and mClca3 in the bronchioles of mice exposed to asbestos for 3, 9, and 40 days, with peak levels observed at 9 days. Bottom: Dual labeling of Ki67 and mucus with Alcian blue/PAS showing the majority of mucus production in nonproliferating cells of the bronchiolar epithelium at all time points. Scale bars: 50 μmol/L (top, bottom); 100 μmol/L (middle).

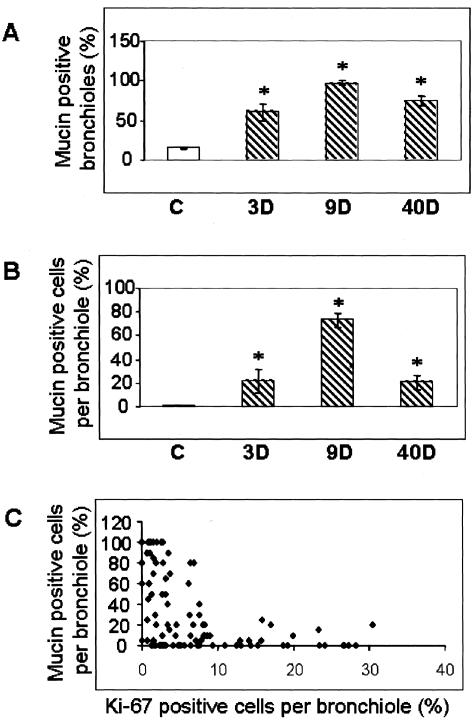

Figure 7.

Quantitation of the number of mucin-positive bronchioles (A) and the percentage of mucin-positive bronchiolar epithelial cells (B). All values are expressed as percentage of total. C: Scatter plot showing bronchiolar epithelial cells that are positive for Alcian blue/PAS and Ki-67. C, Sham control. Hatched bars represent asbestos-exposed groups. Each point represents the mean values for each animal (n = 3 per group per time point). *P < 0.05 compared to sham control.

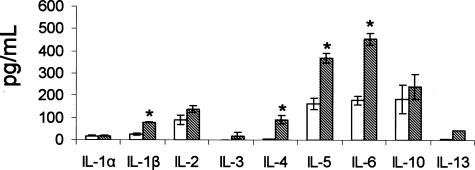

Induction of Cytokines in BALF of Asbestos-Exposed Mice

The induction of cytokines were observed in the BALF of mice exposed to asbestos for 9 days. We chose to measure cytokine levels at 9 days because previous studies have shown that peak inflammation in mice exposed to asbestos occurs at 9 days as noted by the striking accumulation of polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The results show that many of the cytokines measured were significantly increased (IL-1β, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-6) in BALF of mice exposed to asbestos as compared to air-exposed mice (Figure 8). A majority of these cytokines are involved in Th2-mediated immunity.

Figure 8.

Induction of cytokines in BALF of mice exposed to asbestos. Levels of the cytokines indicated above were measured in BALF of mice exposed to air (white bars) or asbestos (cross-hatched bars) for 9 days. Each bar represents the mean of six animals. *P < 0.05 compared to sham control.

Discussion

Here we present the first attempt to characterize gene expression profiles in an inhalation model of chrysotile-induced fibrogenesis using microarray analysis. The results of our study reveal some similarities in expression profiles generated in other rodent models of pulmonary fibrosis and particle-induced injury, and include genes involved in cell-cycle regulation, inflammation, and ECM remodeling. For example, in mice exposed to the fibrotic agent, bleomycin, two independent studies revealed induction of genes involved in inflammation that included chemokines, chemokine receptors, and complement components. These studies also showed up-regulation of genes involved in ECM remodeling such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and cathepsins, as well as components of the matrix, fibronectin, and collagens.22,23

We previously reported proliferation, protracted inflammation, and evidence of fibrogenesis in this inhalation model at 4, 14, and 30 days, respectively.8 Extending the exposure period to 40 days revealed accumulation of collagen surrounding distal bronchioles, an indication of peribronchiolar fibrosis. In agreement with Robledo and colleagues,8 we also observed cellular proliferation, using Ki-67 as a marker, in the distal bronchiolar epithelium in response to chrysotile asbestos. These data are consistent with results using crocidolite asbestos fibers,13,24 which suggest that proliferation of the epithelium in response to early asbestos-induced injury plays a critical role in the initial stages of fibrosis. Although proliferation was sustained throughout the 40 days of exposure to chrysotile, peak levels of cycling cells in the bronchiolar epithelium were observed at 3 days. In concordance with these results, many genes directly involved in regulating the cell cycle were induced by asbestos by 3 days, including cyclin B2, CDC20, and CDC28 protein kinase regulatory subunit 2, whereas a cell cycle inhibitor, cyclin dependant kinase inhibitor 2B, was repressed.

Many genes involved in the inflammatory process, including chemokines and complement components, were induced after 9 days of chrysotile asbestos exposure. Peak expression of these genes at 9 days corresponds to the transient inflammation previously characterized by histopathology and influx of polymorphonuclear leukocytes in BALF.8 Our results in Figure 3B reveal chemokines and cytokines that have been detected in lung sections and/or BALF from patients with asbestosis or silicosis.5 In addition, CCR2 (MIP-1 receptor), CXCL12, CCL9 (MIP-1γ), and IL-1β have been shown to mediate inflammation in association with the development of pulmonary fibrosis.25–28 It should be noted that CCR2 was one of the few genes up-regulated by our nonfibrogenic control, TiO2, suggesting that it plays a more general role in the immune response to mechanical or particle insult rather than an asbestos fiber-specific response.

We also observed increases in novel genes that may play a role in asbestos-induced immune responses. For example, chitinase 3-like 3, a protein implicated in the regulation of connective tissue turnover, was significantly induced by asbestos at 9 days. This protein alters inflammatory cytokines and MMPs as shown recently in human skin fibroblasts and articular chondrocytes.29 Significant induction of chitinase 3-like 3 by asbestos suggests a possible role for this gene in asbestos-induced inflammation, leading to increased deposition of connective tissue.

Frustrated phagocytosis of asbestos fibers by immune cells is thought to cause prominent generation of ROS and reactive nitrogen species. The formation of reactive metabolites such as superoxide anion, hydrogen peroxide, and nitric oxide have been postulated to play an important role in asbestos-induced injury.30 There is evidence to suggest that the generation of ROS and reactive nitrogen species by asbestos leads to DNA damage, and altered proliferation, growth, and apoptosis.11,18 In our study, the induction of the antioxidant enzyme heme oxygenase by chrysotile asbestos suggests that asbestos-mediated injury may be a result of oxidative damage. This observation corresponds to earlier work in human cells showing that heme oxygenase was inducible by crocidolite asbestos.31 In contrast, the radical scavenger superoxide dismutase 3 (extracellular superoxide dismutase) was down-regulated by asbestos, an observation noted in rabbit mesothelial cells exposed to chrysotile asbestos.32 We also observed increases in levels of arginase II, a mitochondrial enzyme that has been recently implicated in repair processes by altering the inflammation-mediated production of nitric oxide. Arginase II also plays a role in collagen synthesis as was shown in a murine model of bleomycin-induced fibrosis.33 In addition, Que and colleagues34 showed the induction of arginase I and II during the fibroproliferative phase of hyperoxic lung injury in rats. The increase in arginase II in our model when peribronchiolar fibrosis (40 days) is observed is consistent with its involvement in repair processes.

Proper remodeling of the ECM after injury is a delicate balance of synthesis and degradation of matrix components. During the fibrotic process, deposition of excess ECM material eventually causes the development of scar tissue. There are many proteases that break down ECM, including MMPs and cathepsins that are implicated in disproportionate metabolism of matrix components.35,36 The sustained increase in the expression of MMP12 (macrophage elastase) in our studies is striking, and consistent with both an influx of alveolar and interstitial macrophages in response to asbestos fibers and the involvement of MMPs in a multitude of lung pathologies, including fibrosis.35 MMP12 induces alveolar and airway remodeling in response to IL-13 and IL-1β, respectively,37,38 suggesting these events are immune mediated. The involvement of MMPs in the development of asbestos-induced lung injury is currently a major focus of research in our laboratory. For example, MMP12 mRNA is inducible by asbestos fibers via protein kinase C delta (PKCδ) signaling pathways in alveolar epithelial and fibroblast cells in vitro (Shukla et al, submitted).

Cathepsins constitute a family of papain-cysteine proteinases that degrade the ECM and limit the release of ECM components from cells.36 Four cathepsins, S, B, Z, and K, were induced by chrysotile. Of these four genes, cathepsin K was most highly induced, with levels increasing throughout time, an observation also noted in a bleomycin-induced model of fibrosis.23 Validation of the microarray data showing induction of cathepsin K mRNA by asbestos was performed by QRT-PCR, an assay that is more sensitive and quantitative compared to oligoarray analysis. This most likely accounts for the discrepancy in the magnitude of induction observed between the array and QRT-PCR, although the expression trends were identical. Currently, cathepsin K is one of the most potent elastases and also has collagenolytic activity. Cathepsin K has been previously shown to reside in macrophages,39,40 fibroblasts,36 and bronchiolar epithelial cells.41 In the current study, the majority of cathepsin K was localized to the interstitial and CD45-positive cells as determined by immunofluorescence whereas minimal reactivity was observed in the bronchiolar epithelium. Cathepsin K knockout mice exposed to bleomycin develop more severe fibrosis compared to normal littermates whereas the production and release of this protease from fibroblasts diminished collagen accumulation.36 These observations suggest that cathepsin K may play a protective role against ECM accumulation in fibroproliferative disease models.

The encoded putative calcium-activated chloride channel, mclca3, was the most highly up-regulated gene in our study. mClca3 has recently been detected in goblet cells within the tracheal and bronchial epithelium amid mucus metaplasia15 and is implicated in the regulation of mucus secretion by controlling the packaging and/or release of secreted mucins such as Muc5ac.42,43 The possible involvement of mClca3 in the pathogenesis of asthma,43 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,44 and cystic fibrosis45 is a major area of focused research efforts. The relevance of mucus production in response to asbestos fiber-induced lung injury to the pathophysiology of fibrosis is unclear, although overproduction of mucus has been documented in lungs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and animals with subepithelial fibrosis.46,47 In addition, asbestos fibers cause marked changes of the tracheal mucosa including epithelial hyperplasia, mucus production, and submucosal inflammation in tracheal explants.48 Whether overproduction of mucus enhances or impairs clearance of fibers, or contributes to the progression of pulmonary fibrosis and other obstructive lung diseases remains to be elucidated.

The sustained increase in expression of mclca3 throughout the course of our study prompted examination of the localization of mucus and mClca3 protein in our model. Compared to sham control mice, chrysotile-exposed mice showed accumulation of mucus within the distal bronchioles at 3 and 9 days. The presence of mucus was still evident by 40 days, but to a much lesser extent comparatively. We also observed a transient induction of muc5ac mRNA at 3 days (data not shown), which fell just short of significance based on our statistical method of analysis. The localization of mClca3 within areas of mucus accumulation at 3 and 9 days in the distal bronchioles suggests that this protein may regulate mucus metaplasia in response to asbestos fibers. Mucus however, does not appear to be produced by actively proliferating cells and occurs after periods of maximal epithelial cell proliferation (3 days). A recent observation by Evans and colleagues19 showed that Clara cells exhibit the ability to secrete mucus while remaining positive for CCSP in the proximal airways of antigen-challenged mice, and this event did not occur with significantly increased epithelial cell proliferation. This observation suggests that mucus production in response to asbestos may not be dependent on additional goblet cells, but instead is a result of differentiating Clara cells.

The signaling pathways that are responsible for controlling the expression of mclca3 have not been completely elucidated. This channel has been linked to the regulation of mucus by controlling the production and/or release of secreted proteins such as Muc5ac, a major component of mucus found in the lung.49 Recent studies have shown that by blocking the production and/or activity of mClca3 (or the human counterpart hClca1) inhibited the production of mucus, whereas overexpression of hClca1 enhanced mucus production.42 These studies suggest that mClca3 plays a pivotal role in the production and/or regulation of mucus although the mechanics of this relationship have not been elucidated. Although not statistically significant, increased levels of muc5ac mRNA was observed at 3 days, preceding the excessive mucus-stained proteins by Alcian blue/PAS at 9 days. Although the levels of mclca3 mRNA were sustained throughout the 40-day exposure period, immunohistochemical approaches revealed peak mucus production at 9 days. The reasons for these disparate observations are unclear, but data suggest that mclca3 has a prolonged mRNA half-life in the lung. Whether mClca3 directly enhances the transcriptional activation of mucin genes and/or affects the formation of mucin-containing granules and their release remains to be determined.

Although it is not clear how mClca3 contributes to the regulation of mucus production, current evidence implicates the immune system as a major player. Numerous cytokines including IL-9, IL-13, and IL-10 induce both muc5ac and hclca1,50–52 suggesting a prominent role of Th2-mediated immunity in the regulation of mucins. In addition, numerous studies have shown that IL-1β induces the production of mucus in the airway epithelium.21,53,54 The up-regulation of IL-1β is noteworthy because it is elevated in rodent inhalation models of asbestos exposure and in cell culture systems.55,56 IL-1β is generally considered an early response cytokine that is produced by many different cell types, but is predominantly synthesized and secreted by macrophages during inflammation whereby it acts on lymphocytes to enhance their capacity to respond to antigens. Transient expression of IL-1β in vivo has been causally linked to progressive fibrotic changes, including the presence of myofibroblasts, fibroblast foci, and collagen and fibronectin accumulation.25 There is evidence to suggest that the induction of both lung and pleural injury by asbestos fibers involves the production of ROS.11 IL-1β also has been implicated in the generation of reactive nitrogen species by chrysotile asbestos fibers,56 and increases mucin production in human bronchial epithelial cells in vitro.21 The induction of IL-1β concurrent with time points of peak inflammation and the increased production of mucus in this study imply that this cytokine may play an important role in the development of mucus production by chrysotile asbestos fibers. Studies to examine the role of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β in the regulation of mucus production in the development of pulmonary fibrosis is the focus of future studies.

Inflammation is a hallmark of inhaled asbestos fibers and other noxious airborne particulates. It is unclear however, what cytokines are involved, and their contribution to the pathogenesis of disease. To elucidate some of the possible players, we determined the levels of various cytokines in the BALF fluid of mice exposed to asbestos for 9 days. The results revealed that chrysotile-asbestos fibers induce many cytokines that are known to be involved in Th2-mediated immunity. These results are consistent with studies implicating Th2 cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, and IL-1β in the transcriptional regulation of mclca3 and mucin genes.42,47,57–61 Despite the statistically significant lack of induction by asbestos of IL-10 and IL-13 at 9 days in BALF, previous studies have suggested these cytokines play a major role in mucus metaplasia and lung remodeling in vivo.51,52 It is possible that induction of these cytokines is more prominent in the lung at other time points. Although correlative, these data implicate Th2-mediated immunity as a possible inducer of mclca3 expression and mucus metaplasia by asbestos in the lung.

The major mechanisms involved in the regulation of mucus production by the immune system include signaling by mitogen-activated protein kinases, specifically via the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) view.62 IL-1β has been shown to alter Muc5ac production by various signaling proteins including extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), p38 mitogen activated protein kinase, protein kinase A, and cyclooxygenase 2.53,54 Transient overexpression of IL-1β may also induce the production of other cytokines such as IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α as shown in rat lungs.25 Induction of IL-6 signal transducer (gp130) in work here suggests that multiple signaling pathways are targets of asbestos-induced injury. Whether asbestos fibers induce the production of mucus by direct interaction with cell surface receptors, or indirectly through the generation of ROS and/or cytokines in the lung epithelium is presently under investigation. Since we have previously shown that asbestos fibers activate mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways via the epidermal growth factor receptor,24 and others have shown transcriptional regulation of mucin genes via this pathway,63 it is possible that asbestos fibers mediate the production of mucus through mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways. The regulatory pathways leading to increases in mucus production and/or secretion by asbestos fibers, and the role of mClca3 in this process, will be addressed in future studies.

In summary, we report gene profiling in a murine inhalation model of chrysotile asbestos-induced fibrosis at time points of peak epithelial cell proliferation, inflammation, and fibrogenesis. The advent of mucus production with the induction of mClca3 as a result of insult by asbestos fibers or other toxic particulates may be an important physiological event relevant to the development and progression of several lung diseases. Further experiments regarding the control and functionality of these genes may shed light on the relevant molecular and physiological events. Information on early gene changes that contribute to the fibrogenic process will allow for the development of preventative and therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Trisha Barrett, Stacie Beuchel, Jamie Levis, Maximilian MacPherson, Masha Stern, and the University of Vermont Microarray Facility for technical assistance; and Dr. Barry Stripp (University of Pittsburgh) for providing an antibody to CCSP and for helpful editorial comments.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Brooke T. Mossman, University of Vermont, 89 Beaumont Ave., HSRF 218, Burlington, VT 05405. E-mail: brooke.mossman@uvm.edu.

Supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (program project grant HL67004 to B.T.M.); the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (training grant T32ES07122); and the Vermont Cancer Center (pilot microarray grant).

References

- Craighead JE. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of malignant mesothelioma. Chest. 1989;96:92S–93S. doi: 10.1378/chest.96.1_supplement.92s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craighead JE. Do silica and asbestos cause lung cancer? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1992;116:16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossman BT, Bignon J, Corn M, Seaton A, Gee JB. Asbestos: scientific developments and implications for public policy. Science. 1990;247:294–301. doi: 10.1126/science.2153315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hei TK, Piao CQ, He ZY, Vannais D, Waldren CA. Chrysotile fiber is a strong mutagen in mammalian cells. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6305–6309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossman BT, Churg A. Mechanisms in the pathogenesis of asbestosis and silicosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1666–1680. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.5.9707141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Nino ME, Heintz N, Scappoli L, Martinelli M, Land S, Nowak N, Haegens A, Manning B, Manning N, MacPherson M, Stern M, Mossman B. Gene profiling and kinase screening in asbestos-exposed epithelial cells and lungs. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;29:S51–S58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll KE, Hassenbein DG, Carter JM, Kunkel SL, Quinlan TR, Mossman BT. TNF alpha and increased chemokine expression in rat lung after particle exposure. Toxicol Lett. 1995;82–83:483–489. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(95)03578-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robledo RF, Buder-Hoffmann SA, Cummins AB, Walsh ES, Taatjes DJ, Mossman BT. Increased phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase immunoreactivity associated with proliferative and morphologic lung alterations after chrysotile asbestos inhalation in mice. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1307–1316. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65001-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll KE. TNFalpha and MIP-2: role in particle-induced inflammation and regulation by oxidative stress. Toxicol Lett. 2000;112–113:177–183. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(99)00282-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robledo R, Mossman B. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of asbestos-induced fibrosis. J Cell Physiol. 1999;180:158–166. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199908)180:2<158::AID-JCP3>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla A, Gulumian M, Hei TK, Kamp D, Rahman Q, Mossman BT. Multiple roles of oxidants in the pathogenesis of asbestos-induced diseases. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34:1117–1129. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossman BT. In vitro studies on the biologic effects of fibers: correlation with in vivo bioassays. Environ Health Perspect. 1990;88:319–322. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9088319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scapoli L, Ramos-Nino ME, Martinelli M, Mossman BT. Src-dependent ERK5 and Src/EGFR-dependent ERK1/2 activation is required for cell proliferation by asbestos. Oncogene. 2004;23:805–813. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll KE, Carter JM, Howard BW, Hassenbein D, Janssen YM, Mossman BT. Crocidolite activates NF-kappa B and MIP-2 gene expression in rat alveolar epithelial cells. Role of mitochondrial-derived oxidants. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106(Suppl 5):1171–1174. doi: 10.1289/ehp.98106s51171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leverkoehne I, Gruber AD. The murine mCLCA3 (alias gob-5) protein is located in the mucin granule membranes of intestinal, respiratory, and uterine goblet cells. J Histochem Cytochem. 2002;50:829–838. doi: 10.1177/002215540205000609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busse W, Banks-Schlegel S, Noel P, Ortega H, Taggart V, Elias J. Future research directions in asthma: an NHLBI Working Group report. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:683–690. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200311-1539WS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz J. Air pollution and children’s health. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1037–1043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla A, Jung M, Stern M, Fukagawa NK, Taatjes DJ, Sawyer D, Van Houten B, Mossman BT. Asbestos induces mitochondrial DNA damage and dysfunction linked to the development of apoptosis. Am J Physiol. 2003;285:L1018–L1025. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00038.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans CM, Williams OW, Tuvim MJ, Nigam R, Mixides GP, Blackburn MR, DeMayo FJ, Burns AR, Smith C, Reynolds SD, Stripp BR, Dickey BF. Mucin is produced by Clara cells in the proximal airways of antigen-challenged mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;31:382–394. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0060OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen YM, Barchowsky A, Treadwell M, Driscoll KE, Mossman BT. Asbestos induces nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kappa B) DNA-binding activity and NF-kappa B-dependent gene expression in tracheal epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8458–8462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray T, Coakley R, Hirsh A, Thornton D, Kirkham S, Koo JS, Burch L, Boucher R, Nettesheim P. Regulation of MUC5AC mucin secretion and airway surface liquid metabolism by IL-1beta in human bronchial epithelia. Am J Physiol. 2004;286:L320–L330. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00440.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuma S, Nishi K, Tanigawara K, Ikawa H, Shiojima S, Takagaki K, Kaminishi Y, Suzuki Y, Hirasawa A, Ohgi T, Yano J, Murakami Y, Tsujimoto G. Molecular monitoring of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis by cDNA microarray-based gene expression profiling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;288:747–751. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski N, Zuo F, Cojocaro G, Yakhini Z, Ben-Dor A, Morris D, Sheppard D, Pardo A, Selman M, Heller RA. Use of oligonucleotide microarrays to analyze gene expression patterns in pulmonary fibrosis reveals distinct patterns of gene expression in mice and humans. Chest. 2002;121:31S–32S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning CB, Cummins AB, Jung MW, Berlanger I, Timblin CR, Palmer C, Taatjes DJ, Hemenway D, Vacek P, Mossman BT. A mutant epidermal growth factor receptor targeted to lung epithelium inhibits asbestos-induced proliferation and proto-oncogene expression. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4169–4175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb M, Margetts PJ, Anthony DC, Pitossi F, Gauldie J. Transient expression of IL-1beta induces acute lung injury and chronic repair leading to pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1529–1536. doi: 10.1172/JCI12568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BB, Paine R, III, Christensen PJ, Moore TA, Sitterding S, Ngan R, Wilke CA, Kuziel WA, Toews GB. Protection from pulmonary fibrosis in the absence of CCR2 signaling. J Immunol. 2001;167:4368–4377. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BB, Kolodsick JE, Thannickal VJ, Cooke K, Moore TA, Hogaboam C, Wilke CA, Toews GB. CCR2-mediated recruitment of fibrocytes to the alveolar space after fibrotic injury. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:675–684. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62289-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips RJ, Burdick MD, Hong K, Lutz MA, Murray LA, Xue YY, Belperio JA, Keane MP, Strieter RM. Circulating fibrocytes traffic to the lungs in response to CXCL12 and mediate fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:438–446. doi: 10.1172/JCI20997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling H, Recklies AD. The chitinase 3-like protein human cartilage glycoprotein 39 inhibits cellular responses to the inflammatory cytokines interleukin-1 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Biochem J. 2004;380:651–659. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnula VL. Oxidant and antioxidant mechanisms of lung disease caused by asbestos fibres. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:706–716. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14c35.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen YM, Marsh JP, Absher MP, Gabrielson E, Borm PJ, Driscoll K, Mossman BT. Oxidant stress responses in human pleural mesothelial cells exposed to asbestos. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:795–802. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.8118652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan X, Wang Z, Yang Q, Wang M, Liu Z. Effect of chrysotile on nitric oxide production and anti-oxidasic activity in rabbit alveolar macrophages. Hua Xi Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2000;31:58–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo M, Oyadomari S, Terasaki Y, Takeya M, Suga M, Mori M, Gotoh T. Induction of arginase I and II in bleomycin-induced fibrosis of mouse lung. Am J Physiol. 2003;285:L313–L321. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00434.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Que LG, Kantrow SP, Jenkinson CP, Piantadosi CA, Huang YC. Induction of arginase isoforms in the lung during hyperoxia. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:L96–L102. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.1.L96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal M, Mandal A, Das S, Chakraborti T, Sajal C. Clinical implications of matrix metalloproteinases. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;252:305–329. doi: 10.1023/a:1025526424637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhling F, Rocken C, Brasch F, Hartig R, Yasuda Y, Saftig P, Bromme D, Welte T. Pivotal role of cathepsin K in lung fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:2203–2216. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63777-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappalainen U, Whitsett JA, Wert SE, Tichelaar JW, Bry K. Interleukin-1beta causes pulmonary inflammation, emphysema, and airway remodeling in the adult murine lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:311–318. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0309OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanone S, Zheng T, Zhu Z, Liu W, Lee CG, Ma B, Chen Q, Homer RJ, Wang J, Rabach LA, Rabach ME, Shipley JM, Shapiro SD, Senior RM, Elias JA. Overlapping and enzyme-specific contributions of matrix metalloproteinases-9 and -12 in IL-13-induced inflammation and remodeling. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:463–474. doi: 10.1172/JCI14136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhling F, Reisenauer A, Gerber A, Kruger S, Weber E, Bromme D, Roessner A, Ansorge S, Welte T, Rocken C. Cathepsin K—a marker of macrophage differentiation? J Pathol. 2001;195:375–382. doi: 10.1002/path.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punturieri A, Filippov S, Allen E, Caras I, Murray R, Reddy V, Weiss SJ. Regulation of elastinolytic cysteine proteinase activity in normal and cathepsin K-deficient human macrophages. J Exp Med. 2000;192:789–799. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.6.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhling F, Gerber A, Hackel C, Kruger S, Kohnlein T, Bromme D, Reinhold D, Ansorge S, Welte T. Expression of cathepsin K in lung epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20:612–619. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.4.3405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Shapiro M, Dong Q, Louahed J, Weiss C, Wan S, Chen Q, Dragwa C, Savio D, Huang M, Fuller C, Tomer Y, Nicolaides NC, McLane M, Levitt RC. A calcium-activated chloride channel blocker inhibits goblet cell metaplasia and mucus overproduction. Novartis Found Symp. 2002;248:150–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi A, Morita S, Iwashita H, Sagiya Y, Ashida Y, Shirafuji H, Fujisawa Y, Nishimura O, Fujino M. Role of gob-5 in mucus overproduction and airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5175–5180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081510898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers DF. The airway goblet cell. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shale DJ, Ionescu AA. Mucus hypersecretion: a common symptom, a common mechanism? Eur Respir J. 2004;23:797–798. doi: 10.1183/09031936.0.00018404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andoh Y, Aikawa T, Shimura S, Sasaki H, Takishima T. Morphometric analysis of airways in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients with mucous hypersecretion. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:175–179. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z, Homer RJ, Wang Z, Chen Q, Geba GP, Wang J, Zhang Y, Elias JA. Pulmonary expression of interleukin-13 causes inflammation, mucus hypersecretion, subepithelial fibrosis, physiologic abnormalities, and eotaxin production. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:779–788. doi: 10.1172/JCI5909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topping DC, Nettesheim P, Martin DH. Toxic and tumorigenic effects of asbestos on tracheal mucosa. J Environ Pathol Toxicol. 1980;3:261–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmen JM, Karlsson NG, Abdullah LH, Randell SH, Sheehan JK, Hansson GC, Davis CW. Mucins and their O-Glycans from human bronchial epithelial cell cultures. Am J Physiol. 2004;287:L824–L834. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00108.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda M, Tulic MK, Levitt RC, Hamid Q. A calcium-activated chloride channel (HCLCA1) is strongly related to IL-9 expression and mucus production in bronchial epithelium of patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:246–250. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.121555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CG, Homer RJ, Cohn L, Link H, Jung S, Craft JE, Graham BS, Johnson TR, Elias JA. Transgenic overexpression of interleukin (IL)-10 in the lung causes mucus metaplasia, tissue inflammation, and airway remodeling via IL-13-dependent and -independent pathways. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:35466–35474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206395200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuperman DA, Huang X, Koth LL, Chang GH, Dolganov GM, Zhu Z, Elias JA, Sheppard D, Erle DJ. Direct effects of interleukin-13 on epithelial cells cause airway hyperreactivity and mucus overproduction in asthma. Nat Med. 2002;8:885–889. doi: 10.1038/nm734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray T, Nettesheim P, Loftin C, Koo JS, Bonner J, Peddada S, Langenbach R. Interleukin-1beta-induced mucin production in human airway epithelium is mediated by cyclooxygenase-2, prostaglandin E2 receptors, and cyclic AMP-protein kinase A signaling. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66:337–346. doi: 10.1124/mol.66.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song KS, Lee WJ, Chung KC, Koo JS, Yang EJ, Choi JY, Yoon JH. Interleukin-1 beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha induce MUC5AC overexpression through a mechanism involving ERK/p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases-MSK1-CREB activation in human airway epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23243–23250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300096200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll KE, Maurer JK, Higgins J, Poynter J. Alveolar macrophage cytokine and growth factor production in a rat model of crocidolite-induced pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1995;46:155–169. doi: 10.1080/15287399509532026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe N, Tanaka S, Kagan E. Asbestos fibers and interleukin-1 upregulate the formation of reactive nitrogen species in rat pleural mesothelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;19:226–236. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.19.2.3111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Dong Q, Louahed J, Dragwa C, Savio D, Huang M, Weiss C, Tomer Y, McLane MP, Nicolaides NC, Levitt RC. Characterization of a calcium-activated chloride channel as a shared target of Th2 cytokine pathways and its potential involvement in asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;25:486–491. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.4.4578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JB, Zhang ZX, Xu YJ, Xing LH, Zhang HL. Effects of interleukin-13 on the gob-5 and MUC5AC expression in lungs of a murine asthmatic model. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2004;27:837–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabbagh K, Takeyama K, Lee HM, Ueki IF, Lausier JA, Nadel JA. IL-4 induces mucin gene expression and goblet cell metaplasia in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 1999;162:6233–6237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn L, Whittaker L, Niu N, Homer RJ. Cytokine regulation of mucus production in a model of allergic asthma. Novartis Found Symp. 2002;248:201–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn L, Homer RJ, MacLeod H, Mohrs M, Brombacher F, Bottomly K. Th2-induced airway mucus production is dependent on IL-4Ralpha, but not on eosinophils. J Immunol. 1999;162:6178–6183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atherton HC, Jones G, Danahay H. IL-13-induced changes in the goblet cell density of human bronchial epithelial cell cultures: MAP kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulation. Am J Physiol. 2003;285:L730–L739. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00089.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewson CA, Edbrooke MR, Johnston SL. PMA induces the MUC5AC respiratory mucin in human bronchial epithelial cells, via PKC, EGF/TGF-alpha, Ras/Raf MEK, ERK and Sp1-dependent mechanisms. J Mol Biol. 2004;344:683–695. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]