Abstract

We previously demonstrated that morphine enhances hepatitis C virus (HCV) replication in human hepatic cells. Here we describe the impact of morphine withdrawal (MW), a recurrent event during the course of opioid abuse, on HCV replicon expression in human hepatic cells. MW enhanced both viral RNA and protein expression in HCV replicon cells. Blocking opioid receptors by treatment with naloxone after morphine cessation (precipitated withdrawal, PW) induced greater HCV replicon expression than MW. Investigation of the mechanism responsible for MW- or PW-mediated HCV enhancement showed that both MW and PW inhibited the expression of endogenous interferon-α (IFN-α) in the hepatic cells. This down-regulation of intracellular IFN-α expression was due to the negative impact of MW or PW on IFN-α promoter activation and on the expression of IFN regulatory factor 7 (IRF-7), a strong transactivator of the IFN-α promoter. In addition, both MW and PW inhibited the anti-HCV ability of recombinant IFN-α in the hepatic cells. These in vitro observations support the concept that opioid abuse favors HCV persistence in hepatic cells by suppressing IFN-α-mediated intracellular innate immunity and contributes to the development of chronic HCV infection.

Injection drug users (IDUs) are the largest group at risk for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in developed countries.1–6 HCV infection rate among IDUs is extremely high generally ranging from 70 to more than 90% in the United States.2,4 IDUs frequently involve the abuse of heroin. In fact, heroin addicts are stereotypic intravenous drug abusers. Of heroin abusers entering treatment programs, 96% reported injection as the primary route of administration.7 IDUs have a greater incidence of infections than nonabusers.8,9 IDUs have a markedly increased prevalence of viral hepatitis A, B, and C.7 Although injection drug use contributes significantly to viral infections, it is difficult to determine whether the cause of the increased exposure to infectious agents is due to transmission through contaminated needles, or whether contact with the drugs themselves, through suppression of immune function in the host, results in greater susceptibility to viruses.10 In the case of HCV infection, there is little information about whether drug abuse, such as heroin, enhances HCV replication and promotes HCV disease progression. This lack of knowledge about the impact of opioid abuse on HCV disease is a major barrier to fundamental understanding of HCV-related morbidity and mortality among IDUs and to the development of new therapeutic approaches for HCV infection.

Because of the HCV epidemic, interest in studying the impact of drug abuse, especially opiates, on HCV infection has increased greatly. This issue is now even more important because of the association of HCV infection with intravenous drug abuse. It is possible that the impact of opioids on HCV infection is related to the ability of opioids to modulate both innate and acquired immune response. For instance, opioids have been shown to inhibit the expression of anti-viral cytokines, such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ)11–14 and IFN-α.14–16 IFN-α is one of critical elements in the innate host defense mechanism against HCV infection,17,18 whereas interferon regulatory factor 7 (IRF-7) has a critical role in rapid induction of IFN-α expression, a central event in establishing the innate anti-viral responses.18–20 IFN-α acts directly through its anti-viral mechanism(s) or through its regulatory effect on innate and adaptive immune responses. IFN-α is the only anti-viral cytokine approved for clinical treatment of chronic HCV infection. IFN-α inhibits HCV RNA expression in the replicon cells.21,22 Our earlier work demonstrated that morphine enhanced HCV replication in the hepatic cells and inhibited the anti-HCV effect of IFN-α.23 This earlier study represents an initial step in understanding the interaction between opioids and HCV in the hepatic cells. In the present study, we investigated the impact of morphine withdrawal (MW), a crucial and recurrent event during the course of opioid abuse, on HCV replicon expression and the anti-HCV effect of IFN-α in human hepatic cells. We also examined the mechanism underlying the impact of MW on HCV replicon expression.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines

The HCV replicon cell line (Huh.8) was obtained from Dr. Charles Rice (The Rockefeller University and Apath, L.L.C., St. Louis, MO). The FCA-1 cell line was a gift from Dr. Christoph Seeger (Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, PA).22 Huh7, a human hepatoma cell line, is the parental cell line of the HCV replicon cell lines (Huh.8 and FCA-1). These cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT), in the presence of penicillin/streptomycin, l-glutamine, and minimal essential medium nonessential amino acids. The culture media for the HCV replicon cells contained G418 (1 mg/ml; Invitrogen Corp., Grand Island, NY). The cells were passaged every 3 days and seeded in 24-well plates (105 cells/well). For all experiments, endotoxin-free media and reagents were used.

Reagents

Morphine sulfate (15 mg/ml) was purchased from Elkins-Sinn, Inc. (Cherry Hill, NJ). Naloxone and rabbit polyclonal antibody against actin were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Recombinant human IFN-α and rabbit polyclonal antibody to IRF-7 were obtained from R&D Systems Inc. (Minneapolis, MN). Mouse monoclonal antibody against HCV NS5A was obtained from ViroStat (Portland, ME). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody and goat anti-rabbit IgG were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA).

Morphine Withdrawal

Huh7 and the HCV replicon cells (Huh.8 and FCA-1) were plated in 24-well plates and treated with or without morphine (10−6 mol/L) every 24 hours for 4 days. Morphine was then removed by washing the cells three times with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at day 5. For precipitated withdrawal (PW) experiments, naloxone (10−8 mol/L) was added to the cell cultures immediately after morphine was removed. The selection of concentrations of morphine (10−6 mol/L) and naloxone (10−8 mol/L) for this study was based on our pilot experiments and published studies.15,23,24 These concentrations are comparable to reported therapeutic serum concentrations of morphine and naloxone in patients.25 There was no cytotoxic effect of morphine treatment on the hepatic cells, as determined by trypan blue dye staining. To determine whether MW or PW interferes with the anti-HCV effect of IFN-α, Huh.8 and FCA-1 cells were incubated with IFN-α (10 U/ml) immediately after morphine was removed. The levels of HCV and IFN-α were analyzed at 24 hours, 48 hours, and 72 hours after MW or PW.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay for IFN-α

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits for IFN-α were purchased from PBL Biomedical Laboratories (Piscataway, NJ) and the assay was performed according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and Real-Time Reverse Transcriptase (RT)-PCR Analyses

Total RNA was extracted from Huh7 and the HCV replicon cells using Tri-Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH) as described.26 Each of the PCR amplifications included heat activation of AmpliTaq Gold for 9 minutes at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds, 52°C for 20 seconds, and 72°C for 40 seconds, and further elongation at 72°C for 7 minutes. The specific oligonucleotide primers used were as follows: IFN-α: 5′-TTT CTC CTG CCT GAA GGA CAG-3′ (sense) and 5′-GCT CAT GAT TTC TGC TCT GAC A-3′ (anti-sense); IRF-7: 5′-CTG TGG TGG TGG GAC AGC TGC-3′ (sense) and 5′-CCC CAC GCG TGC TGT TCG GAG-3′ (anti-sense). The oligonucleotide primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies Inc. (Coralville, IA). HCV real-time RT-PCR assay that we have developed was used for the quantification of HCV RNA.27 The real-time RT-PCR for IFN-α mRNA was performed with the Brilliant SYBR Green QPCP Master Mix (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA).

Transfection and Luciferase Assays

Two plasmids (pIFNA4-Luc and wild-type pIRF-7) were obtained from Dr. Rong-Tuan Lin28 (McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada). The cells undergoing MW or PW were seeded into a 24-well culture plate at the density of 105 cells/well. Transfection was performed with FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) at a ratio of FuGENE 6:plasmid 6:1 (μl:μg) immediately after MW or PW. The cells in each well were harvested 48 hours after transfection and washed twice with 1× PBS by centrifugation at 3300 × g for 3 minutes at room temperature. The cell pellets were lysed with reporter lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI). Cell-free lysates were obtained by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 1 minute at room temperature.

Western Blot

Total cell lysates from the replicon cells were prepared using the lysis buffer (Promega). Protein concentrations were determined by DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Proteins were resuspended in NuPAGE LDS sample buffer (Novex, San Diego, CA), heated for 5 minutes at 95°C, and then equal amounts of protein for each sample were separated in a 10% Bis-Tris Gel in a NuPAGE running buffer with 0.25% running buffer antioxidant for 50 minutes at 200 V. Proteins were transferred to the nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) in NuPAGE transfer buffer at 100 V for 1 hour. The membranes were blocked by 5% fat-free milk in PBST (0.05% Tween 20 in PBS) for 1 hour and incubated with mouse monoclonal antibody against NS5A (1:100) and rabbit polyclonal antibody against actin (1:3000) diluted with 2% fat-free milk in PBST for 1 hour at room temperature. For IRF-7 protein detection, rabbit polyclonal antibody to IRF-7 was diluted 1:200. After washing four times for 5 minutes each with PBST, the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (1:5000) and goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000) in 2% fat-free milk in PBST for 1 hour at room temperature and washed four times as described above. The bound antibodies were developed using SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Prestained molecular markers (Bio-Rad) were used to determine molecular weight of immunoreactive bands.

Statistical Analysis

Where appropriate, data were expressed as mean ± SD. For comparison of the mean of the two groups (morphine or MW or PW versus untreated control cells), statistical significance was assessed by Student’s t-test. Calculations were performed with the use of Stata Statistical Software (StataCorp., College Station, TX). Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

MW Enhances HCV Replicon Expression

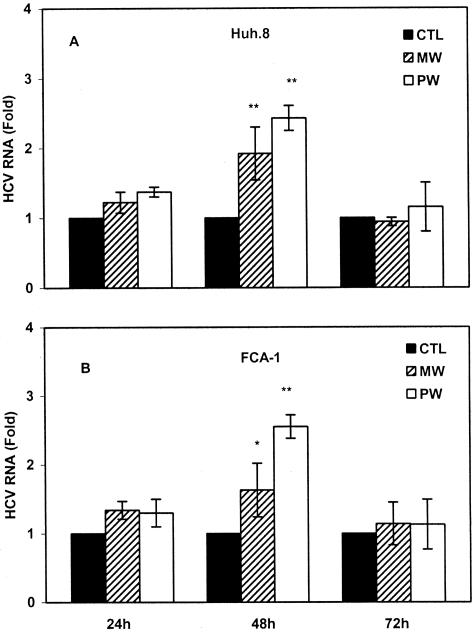

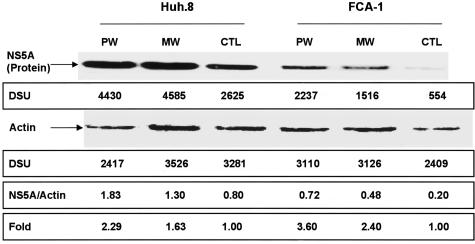

We first examined whether MW or PW enhances HCV RNA expression in Huh.8 and FCA-1 cells. In comparison with the untreated cells, the cells undergoing MW showed increased levels of HCV RNA (Figure 1). Blocking opioid receptors by naloxone after the removal of morphine (PW) also induced higher HCV replicon expression than untreated cells (Figure 1). A significant increase in HCV RNA expression was observed at 48 hours after MW or PW (Figure 1). This MW- or PW-induced increase of HCV RNA was observed in both Huh.8 and FCA-1 cells (Figure 1). We also investigated whether MW or PW enhances the expression of HCV NS5A protein, a critical factor for HCV infection and replication.21 The increased levels of HCV NS5A protein were observed in Huh.8 and FCA-1 cells at 48 hours after MW or PW (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Effect of MW or PW on HCV replicon expression. Huh.8 (A) and FCA-1 (B) cells were incubated with or without morphine (10−6 mol/L) for 4 days, and morphine was removed at day 5. For PW, naloxone (10−8 mol/L) was added to the cell cultures immediately after morphine was removed. Total RNA extracted from the cell cultures was subjected to real-time RT-PCR for HCV RNA quantification at indicated time points after MW or PW. The data are expressed as HCV RNA levels in the cells undergoing MW or PW relative (fold) to those in the untreated control cells (CTL), which is defined as 1. The results shown are the mean ± SD of triplicate cultures, representative of three independent experiments (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; MW or PW versus control).

Figure 2.

Effect of MW or PW on HCV NS5A protein expression. Huh.8 and FCA-1 cells were incubated with or without morphine (10−6 mol/L) for 4 days, and morphine was removed from the cell cultures at day 5. For PW, naloxone (10−8 mol/L) was added to the cell cultures immediately after morphine was removed. Total proteins extracted from the cells at 48 hours after MW or PW were applied onto a nitrocellulose membrane and subjected to Western blot assay using the antibodies specific to NS5A and actin. The insets below the panels show the signal intensities of protein bands of the representative blot expressed as densitometry scanning units (DSUs). One representative experiment is shown. CTL, untreated control cells.

MW Suppresses IFN-α Expression

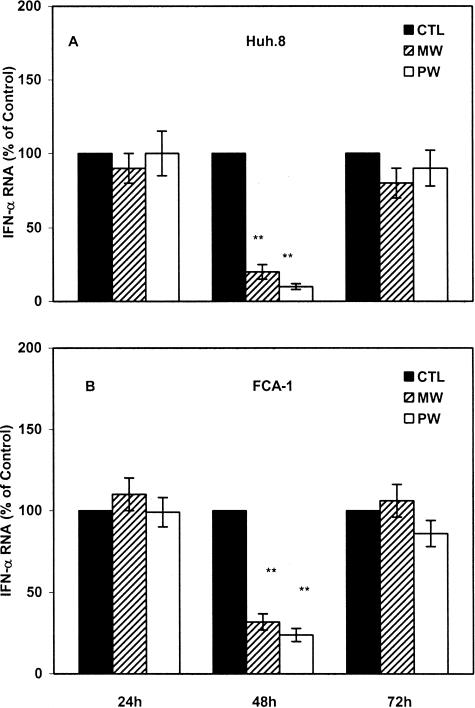

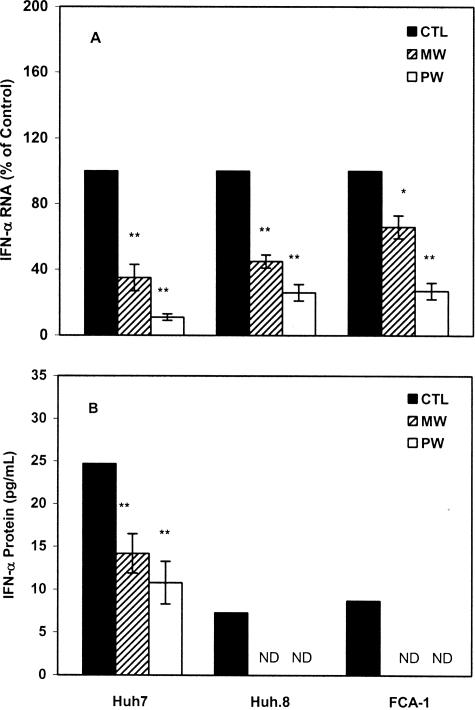

Our earlier study showed that human hepatic cells express endogenous IFN-α that powerfully inhibits HCV replicon expression.29 Thus, we hypothesized that MW or PW suppresses endogenous IFN-α expression in the hepatic cells, through which it induces HCV replicon expression. A significant decrease in IFN-α expression in the replicon cells (Huh.8 and FCA-1) was observed at 48 hours after MW or PW (Figure 3). Because there is a reciprocal interaction between intracellular IFN-α and HCV,29 we also examined whether MW or PW alters endogenous IFN-α expression in Huh7 cells, the parent cell line for the replicon cells. Huh7 cells undergoing MW or PW showed lower levels of IFN-α mRNA than control Huh7 cells (Figure 4A). A significant decrease in endogenous IFN-α expression in Huh7 cells was observed at 48 hours after MW or PW (Figure 4A), which is similar to the replicon cells. We next examined whether IFN-α protein expression is also inhibited in the hepatic cells under-going MW or PW. Both Huh7 and the replicon cells undergoing MW or PW had decreased levels of IFN-α protein in comparison to the control cells (Figure 4B).

Figure 3.

The time point action of MW or PW on endogenous IFN-α expression in the replicon cells. Huh.8 (A) and FCA-1 (B) cells were processed under the identical conditions as described in Figure 1. Total RNA extracted from the cell cultures was subjected to the real-time RT-PCR for IFN-α mRNA quantitation at indicated time points after MW or PW. The data are expressed as IFN-α RNA levels in the cells undergoing MW or PW relative (%) to those in the control cells (CTL), which is defined as 100. The results shown are the mean ± SD of triplicate cultures, representative of three independent experiments (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; MW or PW versus control).

Figure 4.

Effect of MW or PW on endogenous IFN-α expression in the hepatic cells. Huh7, Huh.8, and FCA-1 cells were incubated with or without morphine (10−6 mol/L) for 4 days, and morphine was then removed at day 5. For PW, naloxone (10−8 mol/L) was added to the cultures immediately after morphine was removed. A: RNA extracted from the cells was subjected to real-time RT-PCR for IFN-α RNA quantification at 48 hours after MW or PW. The data are expressed as IFN-α RNA levels in the cells undergoing MW or PW relative (%) to those in the untreated control cells (CTL), which is defined as 100. B: Supernatants were collected from the cell cultures under identical conditions described in A for IFN-α protein quantification by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The results shown in both A and B are the mean ± SD of triplicate cultures, representative of three independent experiments (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; MW or PW versus control).

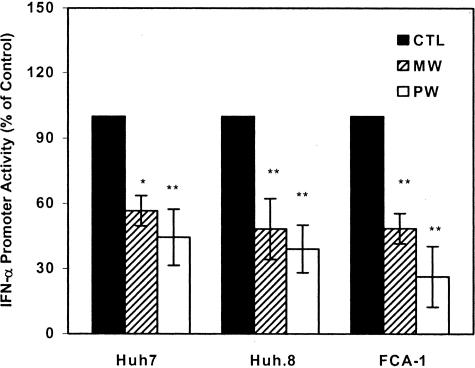

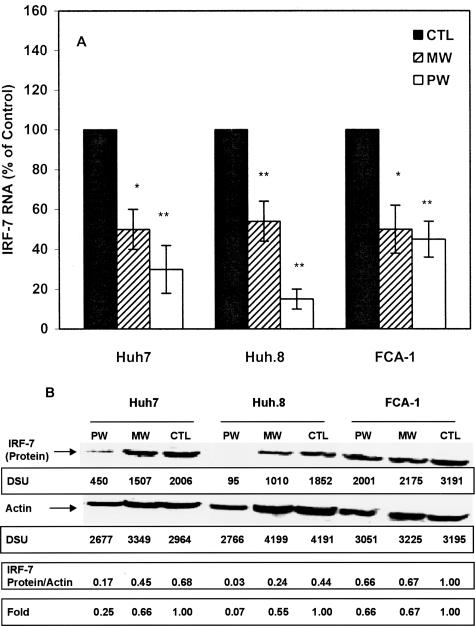

MW Inhibits IRF-7-Induced IFN-α Promoter Activity and IRF-7 Expression

To investigate the mechanism(s) responsible for MW- or PW-mediated down-regulation of endogenous IFN-α expression, we examined whether MW or PW suppresses IFN-α promoter activity in the hepatic cells. Because IRF-7 is a strong activator of IFN-α promoter, we used IRF-7 to activate IFN-α promoter. IRF-7, when introduced into the hepatic cells, significantly activated IFN-α promoter. However, this IRF-7-induced IFN-α promoter activity was significantly suppressed in the hepatic cells undergoing MW or PW (Figure 5). The levels of IFN-α promoter suppression in the HCV replicon cells (Huh.8 and FCA-1) undergoing MW or PW were higher than those in Huh7 cells (Figure 5). Both MW and PW inhibited IRF-7 expression at both transcriptional (Figure 6A) and translational (Figure 6B) levels.

Figure 5.

Effect of MW or PW on IFN-α promoter activity. Huh7, Huh.8, and FCA-1 cells were incubated with or without morphine (10−6 mol/L) for 4 days, and morphine was removed at day 5. For PW, naloxone (10−8 mol/L) was added to the cell cultures immediately after morphine was removed. The cells were then co-transfected with the IRF-7 plasmid and the IFN-α promoter plasmid (IFNA4) linked to a luciferase gene. IRF-7-induced activation of IFN-α promoter was determined by luciferase activity at 48 hours after transfection. The data are expressed as IFN-α promoter activity in the cells undergoing MW or PW relative (%) to those in the untreated control cells (CTL), which is defined as 100. The results shown are the mean ± SD of triplicate cultures, representative of three independent experiments (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; MW or PW versus control).

Figure 6.

Effect of MW or PW on IRF-7 expression. Huh7 and the replicon cells were incubated with or without morphine (10−6 mol/L) for 4 days, and morphine was removed at day 5. For PW, naloxone (10−8 mol/L) was added to the cultures immediately after morphine was removed. A: RNA extracted from the hepatic cells was subjected to conventional RT-PCR for IRF-7 RNA and β-actin RNA at 48 hours after MW or PW. The data in A are expressed as IRF-7 RNA level in the cells undergoing MW or PW relative (%) to those in the untreated control cells (CTL), which is defined as 100. The results shown are the mean ± SD of triplicate cultures, representative of three independent experiments (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; MW or PW versus control). B: Total protein extracted from the replicon cells were applied onto a nitrocellulose membrane and subjected to Western blot assay at 48 hours after MW or PW. The insets below the panels in B show the signal intensities of protein bands. One representative data of three experiments are shown.

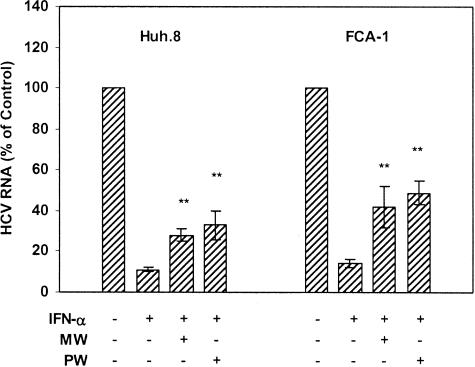

MW Compromises the Anti-HCV Effect of IFN-α

Recombinant IFN-α remains the treatment of choice for chronic HCV infection today. IFN-α treatment, however, is effective in only 30 to 50% of treated patients.30–32 Because IDUs are the largest group at risk for HCV infection, it is critical to understand whether MW plays a role in resistance to IFN-α therapy. We examined whether MW or PW has a negative impact on the anti-HCV effect of recombinant IFN-α in the replicon cells. IFN-α, when added to Huh.8 and FCA-1 cell cultures, significantly inhibited HCV replicon expression (Figure 7). This anti-HCV ability of IFN-α, however, was significantly diminished (from ∼85% to ∼60% and to ∼50% for MW and PW, respectively) in the replicon cells (both Huh.8 and FCA-1 cells) undergoing MW or PW (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Effect of MW or PW on the anti-HCV activity of IFN-α. Huh.8 and FCA-1 cells were incubated with or without morphine (10−6 mol/L) for 4 days, and morphine was then removed at day 5. For PW, naloxone (10−8 mol/L) was added to the cell cultures immediately after morphine was removed. IFN-α (10 U/ml) was added into the cell cultures 1 hour after MW or PW. RNA extracted from the cells was subjected to real-time RT-PCR for HCV RNA and GAPDH RNA quantification at 48 hours after MW or PW. The data are expressed as HCV RNA in the replicon cells that are undergoing MW or PW relative (%) to the untreated control cells, which is defined as 100. The results shown are the mean ± SD of triplicate cultures, representative of three independent experiments (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; IFN-α-treated HCV replicon cells undergoing MW or PW versus IFN-α-treated cells only).

Discussion

Heroin addicts have an increased susceptibility to a variety of infectious diseases.9 Heroin addicts are a high-risk group for HCV infection and the development of chronic HCV disease.33–38 In our earlier studies, we showed that morphine, the active metabolite of heroin, enhances HCV replication in the hepatic cells.23 The present study focused on the impact of MW on HCV replication and on the anti-HCV effect of IFN-α. Physical dependence on morphine is characterized by the occurrence of an abstinence or withdrawal syndrome on termination of the drug. Abstinence syndromes occur after either abrupt withdrawal (cessation of the drug) or PW (with or without drug cessation in conjunction with the administration of an opioid antagonist). Naloxone-precipitated opioid withdrawal is a validated model for testing medications to treat opiate withdrawal.39 In our study, Huh7 and the HCV replicon cells were pretreated with morphine for 4 days to induce a tolerant/dependent state, followed by complete morphine removal or PW (addition of naloxone to the cell cultures immediately after removal of morphine). Using this cell model, we have for the first time demonstrated that MW or PW enhanced HCV replicon expression in the hepatic cell model. When opioid receptors are blocked by naloxone after removal of morphine, there is a greater HCV replicon expression than MW. It is possible that the removal of exogenous morphine results in endogenous opioid expression in the hepatic cells, which may reduce the impact of MW, whereas addition of naloxone should precipitate effect of MW, because naloxone blocks the binding of endogenous opioids to their receptors. The MW- or PW-mediated enhancing effect on HCV is not due to the subsequent effect of the 4-day treatment with morphine, because there was no significant increase in HCV RNA expression at 24 hours after MW or PW (Figure 1). In addition, treatment of the replicon cells with morphine for 6 days had no effect on HCV replicon expression (data not shown). The enhancing effect of MW or PW on HCV replicon expression was also demonstrated at the protein level. Both MW and PW enhanced HCV NS5A protein expression in the replicon cells. We selected HCV NS5A as a primary target protein because NS5A has a critical role in HCV infection and replication.21 Collectively, these new observations in conjunction with our earlier findings23 support the notion that opioid abuse is a co-factor that promotes HCV replication.

The mechanism(s) underlying the positive impact of MW or PW on HCV replicon expression remains primarily unknown. Abrupt withdrawal or PW from morphine induces immunosuppression.40,41 Morphine significantly inhibited both IFN-α-, -β-, and -γ-mediated natural anti-viral defense pathways in human immune cells.14–16 Morphine potentiates HIV infection in vitro by interfering with 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase pathway of IFN-α-mediated anti-viral defense.14 We showed that the intracellular IFN-α is a potent anti-HCV cytokine in the replicon system.29 Although we do not know how the hepatic cells undergo withdrawal at this point, we showed that MW and PW significantly inhibited endogenous IFN-α expression by the hepatic cells. It is well known that IFN-α plays an important role not only in the innate host cell immunity but also in regulation of cell functions. This MW- or PW-mediated cytokine alteration results in a compromised intracellular immunity, which contributes to enhanced HCV replicon expression. We observed an association between MW- or PW-mediated HCV replicon induction and endogenous IFN-α inhibition in the replicon cells. The maximal inhibition of endogenous IFN-α expression in the replicon cells occurred at 48 hours after MW or PW (Figure 3), which matched the time point when the highest enhancing effect of MW or PW on HCV was observed (Figure 1). This inhibition of endogenous IFN-α expression was not due to MW- or PW-mediated enhancement of HCV replicon expression, because MW or PW also inhibited endogenous IFN-α expression in Huh7 cells, the parental cell line for both Huh.8 and FCA-1. These findings suggest that the inhibition of intracellular IFN-α is responsible, at least in part, for both MW- and PW-mediated induction of HCV replicon replication. Our further investigation demonstrated that the down-regulation of endogenous IFN-α expression was related to the inhibitory effect of MW or PW on IFN-α promoter activation (Figure 5). IRF-7 is a strong transactivator of IFN-α promoter and has the ability to amplify IFN gene expression.42–44 Our data, which demonstrate that MW or PW not only suppressed IRF-7-mediated IFN-α promoter activation (Figure 5) but also inhibited IRF-7 expression at both mRNA and protein levels (Figure 6), suggest a possible molecular mechanism whereby MW or PW inhibited endogenous IFN-α expression in the hepatic cells.

Clinical trials indicate that there is a therapeutic benefit of IFN-α treatment in chronic HCV infection.45,46 IFN-α-based treatment, however, is effective in less than 50% of treated patients.47–49 Thus, it is of importance to determine whether morphine is an important co-factor responsible for the failure of IFN-α treatment. Our earlier study23 showed that morphine treatment of HCV replicon cells compromised the anti-HCV effect of IFN-α. The current study demonstrated that both MW and PW also inhibited exogenous IFN-α-mediated anti-HCV activity in the replicon cells. Thus, our findings provide a plausible interpretation of the high failure rate of IFN-α therapy in IDUs. The identification of mechanism(s) involved in morphine’s action on the anti-HCV effect of IFN-α has the potential to improve IFN-α-based treatment for HCV-infected IDUs. Because the mechanism(s) responsible for the IFN-α-mediated therapeutic effect is unknown,22 it is not yet possible for us to determine the mechanism(s) involved in the action of MW or PW on anti-HCV activity of IFN-α in this study. Thus, further studies are critical to determine the anti-HCV mechanism(s) of IFN-α treatment and whether MW or PW interferes with the mechanism(s).

Taken together, our data showing that both MW and PW enhanced HCV replicon expression by suppressing endogenous IFN-α expression in the hepatic cells may have a significant in vivo implication because IFN-α is a critical element in host innate immunity against viral infections.50–53 The reduction of intracellular IFN-α expression by opioids provides a favorable environment for HCV growth in the hepatic cells. The results suggest that opioid abusers experiencing periods of drug taking followed by periods of withdrawal may be immunocompromised in the liver. Thus, our findings that MW or PW inhibits IFN-α-mediated intracellular innate immunity in the hepatic cells suggest that opioid abuse may contribute to the chronicity of HCV infection and promote HCV disease progression.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Charles Rice (The Rockefeller University, New York, NY) for generously providing the Huh7 and Huh.8 cell lines, Dr. Christoph Seeger (Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, PA) for providing the FCA-1 cell line, and Stephen Jasionowski for his excellent editorial work on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Wen-Zhe Ho, Division of Allergy and Immunology, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, 34th St. and Civic Center Blvd., Philadelphia, PA 19104. E-mail: ho@email.chop.edu.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants DA-12815 and DA-16022 to W.-Z.H. and AA-13547 to S.D.D.).

References

- Alter MJ. Epidemiology of hepatitis C. Hepatology. 1997;26:62S–65S. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alter MJ. Hepatitis C virus infection in the United States. J Hepatol. 1999;31:88–91. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80381-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DL, Cannon RO, Shapiro CN, Hook EW, III, Alter MJ, Quinn TC. Hepatitis C, hepatitis B, and human immunodeficiency virus infections among non-intravenous drug-using patients attending clinics for sexually transmitted diseases. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:990–995. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams I. Epidemiology of hepatitis C in the United States. Am J Med. 1999;107:2S–9S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00373-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlin BR, Seal KH, Lorvick J, Kral AH, Ciccarone DH, Moore LD, Lo B. Is it justifiable to withhold treatment for hepatitis C from illicit-drug users? N Engl J Med. 2001;345:211–215. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107193450311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira ML, Bastos FI, Telles PR, Yoshida CF, Schatzmayr HG, Paetzold U, Pauli G, Schreier E. Prevalence and risk factors for HBV, HCV and HDV infections among injecting drug users from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1999;32:1107–1114. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X1999000900009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haverkos HW, Lange WR. From the Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration. Serious infections other than human immunodeficiency virus among intravenous drug abusers. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:894–902. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.5.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussey HH, Katz S. Infections resulting from narcotic addiction; report of 102 cases. Am J Med. 1950;9:186–193. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(50)90021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louria DB, Hensle T, Rose J. The major medical complications of heroin addiction. Ann Intern Med. 1967;67:1–22. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-67-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy L, Wetzel M, Sliker JK, Eisenstein TK, Rogers TJ. Opioids, opioid receptors, and the immune response. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;62:111–123. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson PK, Sharp B, Gekker G, Brummitt C, Keane WF. Opioid-mediated suppression of interferon-gamma production by cultured peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Clin Invest. 1987;80:824–831. doi: 10.1172/JCI113140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein TK, Bussiere JL, Rogers TJ, Adler MW. Immunosuppressive effects of morphine on immune responses in mice. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1993;335:41–52. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2980-4_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Barke RA, Charboneau R, Loh HH, Roy S. Morphine negatively regulates interferon-gamma promoter activity in activated murine T cells through two distinct cyclic AMP-dependent pathways. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:37622–37631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301224200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homan JW, Steele AD, Martinand-Mari C, Rogers TJ, Henderson EE, Charubala R, Pfleiderer W, Reichenbach NL, Suhadolnik RJ. Inhibition of morphine-potentiated HIV-1 replication in peripheral blood mononuclear cells with the nuclease-resistant 2-5A agonist analog, 2-5A(N6B). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30:9–20. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200205010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair MP, Schwartz SA, Polasani R, Hou J, Sweet A, Chadha KC. Immunoregulatory effects of morphine on human lymphocytes. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4:127–132. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.2.127-132.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll-Keller F, Schmitt C, Thumann C, Schmitt MP, Caussin C, Kirn A. Effects of morphine on purified human blood monocytes. Modifications of properties involved in antiviral defences. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1997;19:95–100. doi: 10.1016/s0192-0561(97)00017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biron CA, Cousens LP, Ruzek MC, Su HC, Salazar-Mather TP. Early cytokine responses to viral infections and their roles in shaping endogenous cellular immunity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;452:143–149. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5355-7_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen GC. Viruses and interferons. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:255–281. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda K, Yanai H, Negishi H, Asagiri M, Sato M, Mizutani T, Shimada N, Ohba Y, Takaoka A, Yoshida N, Taniguchi T. IRF-7 is the master regulator of type-I interferon-dependent immune responses. Nature. 2005;434:772–777. doi: 10.1038/nature03464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton GM, Medzhitov R. Linking Toll-like receptors to IFN-alpha/beta expression. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:432–433. doi: 10.1038/ni0503-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blight KJ, Kolykhalov AA, Rice CM. Efficient initiation of HCV RNA replication in cell culture. Science. 2000;290:1972–1974. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5498.1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JT, Bichko VV, Seeger C. Effect of alpha interferon on the hepatitis C virus replicon. J Virol. 2001;75:8516–8523. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.18.8516-8523.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Zhang T, Douglas SD, Lai JP, Xiao WD, Pleasure DE, Ho WZ. Morphine enhances hepatitis C virus (HCV) replicon expression. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1167–1175. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63476-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan SD, Schwartz SA, Shanahan TC, Chawda RP, Nair MP. Morphine regulates gene expression of alpha- and beta-chemokines and their receptors on astroglial cells via the opioid mu receptor. J Immunol. 2002;169:3589–3599. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson PK, Gekker G, Brummitt C, Pentel P, Bullock M, Simpson M, Hitt J, Sharp B. Suppression of human peripheral blood mononuclear cell function by methadone and morphine. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:480–487. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.3.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Li Y, Lai JP, Douglas SD, Metzger DS, O’Brien CP, Ho WZ. Alcohol potentiates hepatitis C virus replicon expression. Hepatology. 2003;38:57–65. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JH, Lai JP, Douglas SD, Metzger D, Zhu XH, Ho WZ. Real-time RT-PCR for quantitation of hepatitis C virus RNA. J Virol Methods. 2002;102:119–128. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(02)00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R, Mamane Y, Hiscott J. Multiple regulatory domains control IRF-7 activity in response to virus infection. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34320–34327. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002814200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Lin RT, Li Y, Douglas SD, Maxcey C, Ho C, Lai JP, Wang YJ, Wan Q, Ho WZ. Hepatitis C virus inhibits intracellular interferon alpha expression in human hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2005;42:819–827. doi: 10.1002/hep.20854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Bisceglie AM, Martin P, Kassianides C, Lisker-Melman M, Murray L, Waggoner J, Goodman Z, Banks SM, Hoofnagle JH. Recombinant interferon alfa therapy for chronic hepatitis C. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1506–1510. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198911303212204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GL, Balart LA, Schiff ER, Lindsay K, Bodenheimer HC, Jr, Perrillo RP, Carey W, Jacobson IM, Payne J, Dienstag JL. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C with recombinant interferon alfa. A multicenter randomized, controlled trial. Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1501–1506. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198911303212203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poynard T, Bedossa P, Chevallier M, Mathurin P, Lemonnier C, Trepo C, Couzigou P, Payen JL, Sajus M, Costa JM. A comparison of three interferon alfa-2b regimens for the long-term treatment of chronic non-A, non-B hepatitis. Multicenter Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1457–1462. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506013322201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day C, Ross J, Dolan K. Hepatitis C-related discrimination among heroin users in Sydney: drug user or hepatitis C discrimination? Drug Alcohol Rev. 2003;22:317–321. doi: 10.1080/0959523031000154463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth BP, Barry J, Keenan E. Irish injecting drug users and hepatitis C: the importance of the social context of injecting. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:166–172. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassani S, Toro C, de la Fuente L, Brugal MT, Jimenez V, Soriano V. Rate of infection by blood-borne viruses in active heroin users in 3 Spanish cities. Med Clin (Barc) 2004;122:570–572. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(04)74311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garten RJ, Lai S, Zhang J, Liu W, Chen J, Vlahov D, Yu XF. Rapid transmission of hepatitis C virus among young injecting heroin users in Southern China. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33:182–188. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backmund M, Meyer K, Wachtler M, Eichenlaub D. Hepatitis C virus infection in injection drug users in Bavaria: risk factors for seropositivity. Eur J Epidemiol. 2003;18:563–568. doi: 10.1023/a:1024603517136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaglio G, Lugoboni F, Pajusco B, Sarti M, Talamini G, Lechi A, Mezzelani P, Des Jarlais DC. Factors associated with hepatitis C virus infection in injection and noninjection drug users in Italy. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:33–40. doi: 10.1086/375566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen MI, McMahon TJ, Hameedi FA, Pearsall HR, Woods SW, Kreek MJ, Kosten TR. Effect of clonidine pretreatment on naloxone-precipitated opiate withdrawal. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;276:1128–1135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahim RT, Adler MW, Meissler JJ, Jr, Cowan A, Rogers TJ, Geller EB, Eisenstein TK. Abrupt or precipitated withdrawal from morphine induces immunosuppression. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;127:88–95. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahim RT, Feng P, Meissler JJ, Rogers TJ, Zhang L, Adler MW, Eisenstein TK. Paradoxes of immunosuppression in mouse models of withdrawal. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;147:114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marie I, Durbin JE, Levy DE. Differential viral induction of distinct interferon-alpha genes by positive feedback through interferon regulatory factor-7. EMBO J. 1998;17:6660–6669. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Suemori H, Hata N, Asagiri M, Ogasawara K, Nakao K, Nakaya T, Katsuki M, Noguchi S, Tanaka N, Taniguchi T. Distinct and essential roles of transcription factors IRF-3 and IRF-7 in response to viruses for IFN-alpha/beta gene induction. Immunity. 2000;13:539–548. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R, Genin P, Mamane Y, Hiscott J. Selective DNA binding and association with the CREB binding protein coactivator contribute to differential activation of alpha/beta interferon genes by interferon regulatory factors 3 and 7. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;20:6342–6353. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.17.6342-6353.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrao G, Arico S. Independent and combined action of hepatitis C virus infection and alcohol consumption on the risk of symptomatic liver cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1998;27:914–919. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley TE, McCarthy M, Breidi L, Layden TJ. Impact of alcohol on the histological and clinical progression of hepatitis C infection. Hepatology. 1998;28:805–809. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alter HJ, Seeff LB. Recovery, persistence, and sequelae in hepatitis C virus infection: a perspective on long-term outcome. Semin Liver Dis. 2000;20:17–35. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GL, Esteban-Mur R, Rustgi V, Hoefs J, Gordon SC, Trepo C, Shiffman ML, Zeuzem S, Craxi A, Ling MH, Albrecht J. Interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin for the treatment of relapse of chronic hepatitis C. International Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1493–1499. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811193392102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Schiff ER, Shiffman ML, Lee WM, Rustgi VK, Goodman ZD, Ling MH, Cort S, Albrecht JK. Interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1485–1492. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811193392101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katze MG, He Y, Gale M., Jr Viruses and interferon: a fight for supremacy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:675–687. doi: 10.1038/nri888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Katze MG. To interfere and to anti-interfere: the interplay between hepatitis C virus and interferon. Viral Immunol. 2002;15:95–119. doi: 10.1089/088282402317340260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia AM, Hagmeyer KO. Combination therapy with interferon and ribavirin in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C infection. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:487–494. doi: 10.1345/aph.19183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biron CA. Role of early cytokines, including alpha and beta interferons (IFN-alpha/beta), in innate and adaptive immune responses to viral infections. Semin Immunol. 1998;10:383–390. doi: 10.1006/smim.1998.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]