Abstract

Plague, caused by the gram-negative bacterium Yersinia pestis, primarily affects rodents but is also an important zoonotic disease of humans. Bubonic plague in humans follows transmission by infected fleas and is characterized by an acute, necrotizing lymphadenitis in the regional lymph nodes that drain the intradermal flea bite site. Septicemia rapidly follows with spread to spleen, liver, and other organs. We developed a model of bubonic plague using the inbred Brown Norway strain of Rattus norvegicus to characterize the progression and kinetics of infection and the host immune response after intradermal inoculation of Y. pestis. The clinical signs and pathology in the rat closely resembled descriptions of human bubonic plague. The bacteriology; histopathology; host cellular response in infected lymph nodes, blood, and spleen; and serum cytokine levels were analyzed at various times after infection to determine the kinetics and route of disease progression and to evaluate hypothesized Y. pestis pathogenic mechanisms. Understanding disease progression in this rat infection model should facilitate further investigations into the molecular pathogenesis of bubonic plague and the immune response to Y. pestis at different stages of the disease.

Yersinia pestis is the gram-negative bacterium responsible for plague, a disease that primarily affects rodents but occasionally humans and other mammals.1,2 Bubonic, septicemic, and pneumonic forms of plague, which differ in certain aspects of symptomatology, pathology, route of transmission, and epidemiology, have been described in humans.1–4 Bubonic plague, which is transmitted by fleas, is characterized by the abrupt appearance of an enlarged lymph node accompanied by fever, headache, chills, myalgia, and malaise 2 to 7 days after the infectious fleabite.1,2 At autopsy, the enlarged lymph node is typically hemorrhagic or necrotic, and the surrounding periglandular region appears hemorrhagic and edematous, making the outlines of the lymph node indistinct. The infected enlarged lymph node and periglandular region together constitute the bubo, which is the pathognomonic feature of bubonic plague.1,3,4 Without early treatment, bubonic plague usually progresses rapidly to a life-threatening septicemia. Occasionally, hematogenous spread to the lungs results in pneumonic plague, a rapidly fatal and highly contagious airborne disease.1

Mice, rats, and guinea pigs have been used as animal models since the discovery of the plague bacillus, primarily to confirm Y. pestis isolates from suspected plague cases.1 Plague in white rats and guinea pigs is characterized by the development of a red papule at the inoculation site followed by enlargement of the regional lymph nodes, septicemia, and rapid death.1,5,6 At necropsy, the gross pathology of the lymph node draining the inoculation site in these two rodent species resembles human bubonic plague, with a typical swollen, hemorrhagic lymph node embedded in an edematous mass.1,7,8 In contrast to rats and guinea pigs, mice do not develop typical buboes, although their lymph nodes are infected and sometimes enlarged.1 Mice, rats, and guinea pigs have also been used to evaluate plague vaccines and to study the immune response to Y. pestis.9,10 Previous studies reported considerable variation in susceptibility to plague among individual rats,11 and mice have been the most commonly used model for molecular pathogenesis and vaccine studies since the 1950s.5,12–14

Based on the successive appearance of clinical signs and the pathology observed in humans and animals at necropsy, it was hypothesized that Y. pestis first disseminates from the skin to the draining regional lymph node, from where the bacteria spread to the blood and colonize spleen, liver, and other organs.1–4,15 However, despite the long history of rodent models to study various aspects of plague, systematic studies of the temporal progression of the histopathology and host response to bubonic plague are incomplete or lacking. To our knowledge, only one study explicitly attempted to follow chronologically the course of infection after inoculation of Y. pestis into the skin of mice, rats, and guinea pigs, and this study relied primarily on attenuated strains.15

In the present study, we developed and characterized a model of bubonic plague in the rat, an animal model that has not been routinely used in plague pathogenesis studies for many years. We chose the rat, the animal most often associated with outbreaks of human urban plague, because unlike mice, rats develop buboes similar in pathology to human buboes and because the immunology and genetics of the rat are well characterized compared with the guinea pig.1,16 Using the Brown Norway strain of Rattus norvegicus, we monitored the kinetics and progression of bacterial spread after intradermal (ID) inoculation to explicitly test long-held hypotheses about the course of development of bubonic and septicemic plague. The rat model was also used to characterize the temporal development of histopathology and cellular immune response in the spleen and lymph nodes, allowing us to evaluate hypothesized mechanisms of Y. pestis pathogenesis and immune evasion during infection. Plague in the highly susceptible Brown Norway rat closely resembles human plague; thus, this rat provides a useful model to study microbial pathogenesis, host response, and the efficacy of new medical countermeasures against plague.

Materials and Methods

Animal Infections

Female, 8- to 10-week-old inbred Brown Norway (BN) and outbred Sprague-Dawley (SD) and Wistar (WS) rats (Charles River Laboratories, Willmington, MA) were used after a 1-week acclimatization. The fully virulent Y. pestis strain 195/P17 was cultured in Luria broth at 28°C for 18 hours, quantified by Petroff-Hausser direct count, and diluted in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, to 104 bacteria/ml. The number of Y. pestis in the dilution was verified by colony-forming unit (CFU) counts on Yersinia selective agar base (Difco). In all experiments, rats were infected by ID injection of 50 μl of PBS containing ∼500 Y. pestis CFU in the left ear or the left dorsal posterior surface. Rats were examined three times daily and were euthanized at 6, 24, 36, 48, or 72 hours after infection or on the signs of terminal disease described in the results. All experiments were performed at Biosafety Level 3 and were approved by the NIH, NIAID, RML Biosafety and Animal Care and Use Committees in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Bacteriology

The spleen; heart blood; and the inguinal, axillary, and maxillary lymph nodes were collected immediately after euthanasia and placed on ice. The spleens and lymph nodes were completely triturated through sterile wire mesh into PBS, and dilutions of these triturated organs and blood were plated on Yersinia selective agar base. CFUs were counted after 72 hours of incubation at 28°C. Differences in the average number of Y. pestis CFUs recovered from the different tissues were evaluated by t-test. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

The spleen and the inguinal, axillary, and maxillary lymph nodes were collected from a second group of BN rats immediately after euthanasia and placed in neutral buffered 10% formalin. Formalin-fixed samples were embedded in paraffin, and 4-μm-thick sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or with the Naphthol AS-D chloroacetate esterase kit (Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was performed on additional paraffin-embedded sections using a DAKO autostainer. Anti-Y. pestis antiserum18 and the secondary antibody, goat-anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) horseradish peroxidase conjugated (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL), were used to specifically detect bacteria. To stain macrophages, IHC was also performed using the anti-rat mononuclear phagocyte antibody (clone 1C7), its isotype control, and the biotinylated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). Apoptotic cells were detected by IHC using rabbit polyclonal antibody H-277 raised against human caspase-3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and a biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody.

Macrophages in lymph node and spleen sections were enumerated by counting 1C7-positive cells. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) were enumerated in lymph node sections by counting cells showing a typical nucleus by H&E staining and in spleen sections by counting cells showing a typical nucleus and cytoplasmic granules stained with Naphthol AS-D chloroacetate esterase. Macrophages and PMNs in entire lymph node sections and in 50 fields of spleen sections were counted by light microscopy at 600× magnification.

Hematology and Serology

Total white blood cell (WBC) and platelet counts from EDTA-anticoagulated blood were determined manually by using a hematocytometer.19 White blood cell differential counts were determined from Wright-stained blood smears.19 Sera were collected by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 10 minutes of blood that had coagulated for 30 minutes at 37°C, sterilized by filtration through low protein-binding 0.2-μm filters (Millipore, Bedford MA), and stored at −80°C until cytokine assays were performed. Serum samples were diluted in PBS, and interleukin-10 (IL-10) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) levels were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using the Rat BD OptEIASet (BD Biosciences) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) with the RAT IFN-γ ELISA Ready-SET-Go kit from eBioscience (San Diego, CA).

Results

Susceptibility and Clinical Signs of Plague in Brown Norway, Sprague-Dawley, and Wistar Strains of R. norvegicus

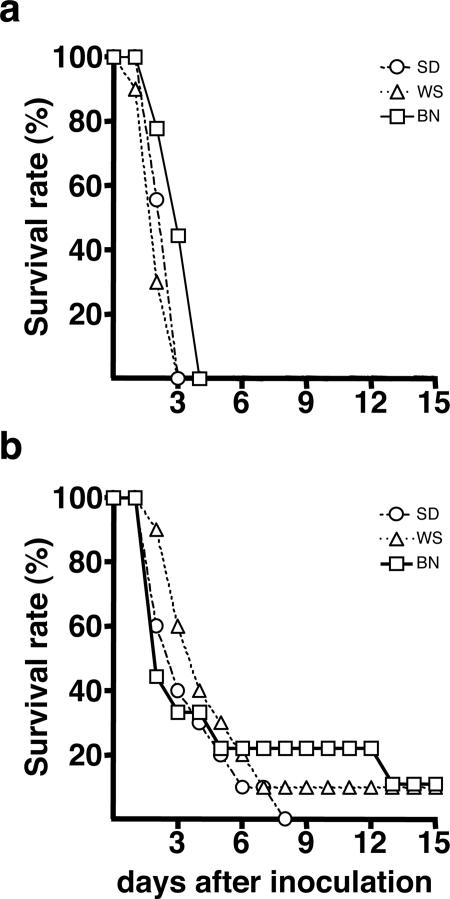

Because different rodent strains reportedly vary in susceptibility to plague,1,11 we initially evaluated three R. norvegicus rat strains and two injection sites for suitability as a model of human bubonic plague. Groups of 9 or 10 Brown Norway (BN), Sprague-Dawley (SD), and Wistar (WS) rats were injected ID in the left ear or in the left lower back with ∼500 Y. pestis and monitored for disease. The size and ID site of the inoculum are reflective of transmission by fleabite.20 Inflammation at the inoculation site in the form of a small red papule was the first sign, appearing 24 to 48 hours after inoculation. The development of a papule depended both on the inoculation site and the rat stain, however. It occurred in 20% of BN, 80% of SD, and 90% of WS rats after back inoculation but on no BN and ≤40% of SD and WS after ear inoculation. The next signs observed were roughcast fur and limping (reluctance to move the left hind leg after inoculation in the back and the left front leg after inoculation in the left ear), but these rats were otherwise alert and active. Rats of all three strains developed these signs, but their time of onset was variable, appearing 2 to 12 days after inoculation. Regardless of the inoculation site, however, signs of terminal plague appeared abruptly 12 to 18 hours after limping was detected, and the signs included polydipsia, watery eyes, poorly groomed hair, hunched posture, and reluctance and difficulty in moving. Rats were euthanized when these signs appeared: 2 to 4 days and 2 to 13 days after inoculation in the back and the ear, respectively (Figure 1). All 29 rats inoculated in the back developed terminal disease, whereas 2 of 30 rats (one BN and one WS) inoculated in the ear did not.

Figure 1.

Incidence of terminal plague in rats injected ID with ∼500 CFU of Y. pestis 195/P. Groups of 9 to 10 rats were inoculated in the lower lumbar region (a) or in the ear (b). BN, Brown Norway; SD, Sprague-Dawley; WS, Wistar rat strains.

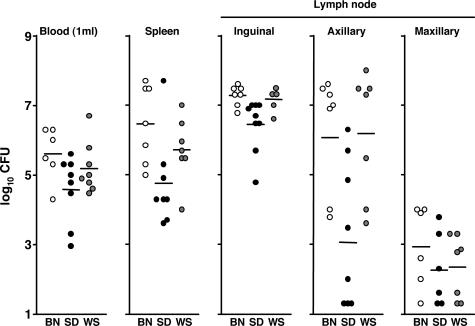

Comparative Gross Pathology and Bacteriology of Terminal Bubonic Plague in Brown Norway, Sprague-Dawley, and Wistar Rats

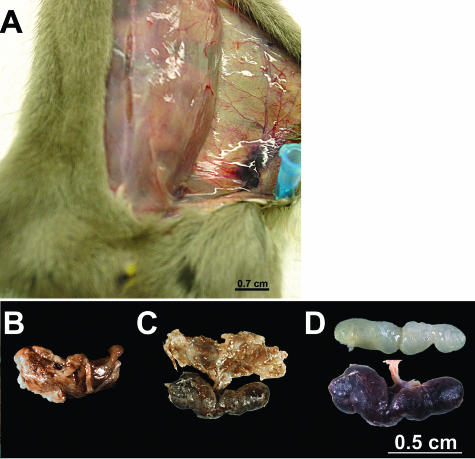

At the time of euthanasia, the left inguinal lymph nodes of 89, 50, and 89% of BN, SD, and WS rats, respectively, that had been inoculated in the left lower back were surrounded by an edematous, hemorrhagic, viscous capsule, and after removal of this material, the lymph node was necrotic and two to four times larger than normal (Figure 2). This picture exactly matches descriptions of the bubo in human plague patients at autopsy.2–4 The left axillary lymph node from 56, 50, and 67% of BN, SD, and WS rats, respectively, was also enlarged but less frequently surrounded by an edematous, hemorrhagic, gelatinous capsule. The right axillary, inguinal, and maxillary and left maxillary lymph nodes were of normal size and appearance. At the terminal stage of the disease, the bacterial load in the blood, the spleen, and the left inguinal, axillary, and maxillary lymph nodes of BN and WS rats inoculated in the left lower back were comparable; SD rats consistently had lower average bacterial loads (Figure 3). In some rats, the left axillary lymph node (on the same side as the inoculation site) contained as many bacteria as the left inguinal lymph node (the node most proximal to the inoculation site).

Figure 2.

Typical bubo formation in the Brown Norway rat. A: Enlarged left inguinal lymph node surrounded by edema and hemorrhage 3 days after ID inoculation of ∼500 Y. pestis in the left lower back. B to C: Dissected bubo before (B) and after (C) removal of the surrounding gelatinous capsule. D: Comparison of the uninfected normal right inguinal lymph node (top) and necrotic enlarged left inguinal lymph node (bottom) dissected from the rat shown in A.

Figure 3.

Bacterial load in rat blood, spleen, and lymph nodes at the terminal stage of plague. Y. pestis CFU counts from individual Brown Norway (BN, open circles), Sprague-Dawley (SD, closed circles), and Wistar (WS, gray circles) rats are indicated. Horizontal bars indicate the mean of the individual data points.

In rats inoculated in the left ear, the left maxillary lymph node was enlarged and necrotic in 88, 33, and 56% of BN, SD, and WS rats, respectively, but the periglandular region was not markedly edematous or hemorrhagic, as was seen for the inguinal nodes of rats inoculated in the lower back. The right maxillary lymph node was also slightly enlarged in 75, 11, and 67% of BN, SD, and WS rats, but left and right inguinal and axillary glands appeared normal. At the terminal stage of the disease, bacterial numbers in the blood, spleen, and the left maxillary lymph node draining the inoculation site were similar to those observed after inoculation in the lower back (data not shown). However, the lymph nodes distal to the site of inoculation (left axillary and inguinal nodes) contained 1000-fold fewer bacteria than the draining maxillary node.

In conclusion, all three rat strains developed similar physical signs and pathology after ID inoculation with Y. pestis. We chose the BN strain for further study, because this rat is an inbred strain, the genome of which was recently completely sequenced.16 We also selected the left lower back as the injection site for the model because this led to the formation of a typical bubo in the inguinal lymph node.

Route and Progression of Bubonic Plague in the Brown Norway Rat

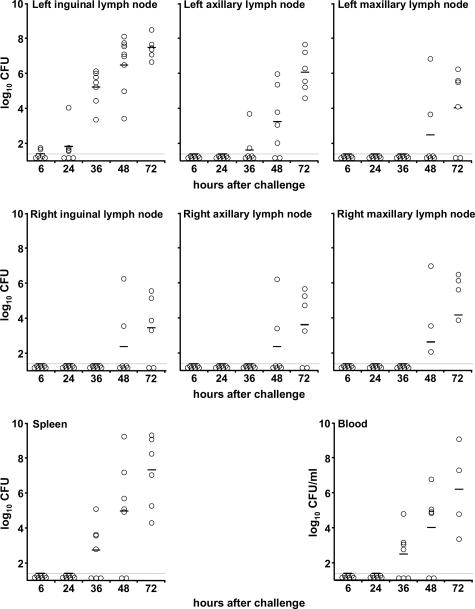

Kinetics of Y. pestis Colonization of the Lymph Nodes, Blood, and Spleen

The temporal progression of infection after ID injection of ∼600 Y. pestis in the left lower back is shown in Figure 4. The left inguinal lymph node was colonized very early, because ∼50 Y. pestis were isolated from this organ in two of seven rats 6 hours after inoculation and in all seven rats by 24 to 36 hours. Bacteria appeared in the left axillary lymph node, the blood, and the spleen only after 36 hours, and these sites were colonized in all rats only after 72 hours. Infection of the right inguinal, right axillary, and right and left maxillary lymph nodes occurred last, after the appearance of septicemia. The number of bacteria increased exponentially in all colonized tissues; by 72 hours, the left inguinal node, the blood, the spleen, and the left axillary node of all seven rats were heavily infected, but other lymph nodes from two of seven rats were not colonized.

Figure 4.

Kinetics of colonization and bacterial load in the Brown Norway rat. Open circles indicate Y. pestis CFU counts in left and right inguinal, axillary and maxillary lymph nodes, the spleen, and the blood of individual rats at different times after ID injection of ∼600 Y. pestis in the left lower back. The dashed line indicates the detection limit (15 CFU), and horizontal lines indicate the mean CFU per tissue.

In summary, Y. pestis infected the lymph node proximal to the inoculation site first and later appeared in the blood, spleen, and distal lymph nodes. At the final time point, the bacterial load was the highest in the left inguinal bubo, lower in the blood and the spleen, and lowest in lymph nodes distal from the inoculation site. The axillary lymph node located on the same side as the inoculation site contained only slightly fewer Y. pestis, on average, than the left inguinal bubo, but this difference was also statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Progression of Lymphadenopathy in the Proximal Draining Lymph Node

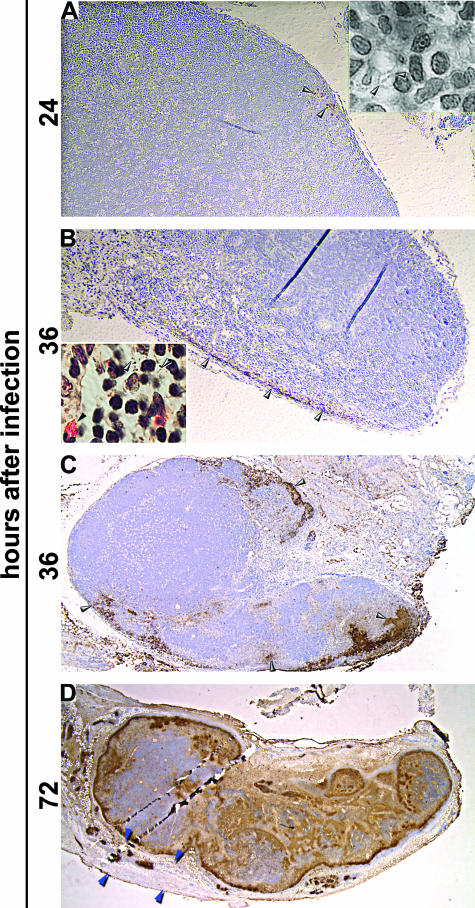

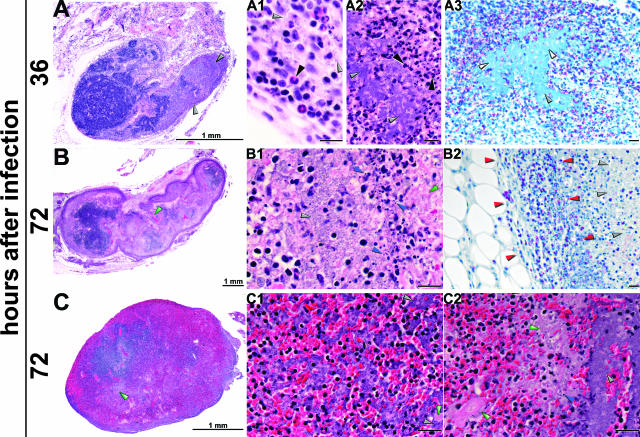

The sequential progression of lymphadenopathy after ID injection of ∼250 Y. pestis in the left lower back is shown in Figures 5 to 7. By 24 hours after infection, a few extracellular bacteria appeared in the marginal sinus of the left inguinal lymph node (Figure 5A), which then replicated and spread within the sinus (Figure 5, A and B). Later, extracellular bacteria increased in numbers and continued to spread within the marginal sinus, with limited PMN recruitment compared with the number of bacteria (Figure 6A1). At 36 hours, multifocal aggregates of bacteria extended from the marginal sinus into the cortex (Figures 5C and 6A) and were surrounded by an increased number of PMNs and cellular debris (Figure 6, A2 and A3). The marginal and medullary sinuses were expanded and contained small amounts of eosinophilic, homogenous material, which was interpreted as edema (data not shown). Late in the infection, myriad bacteria mixed with abundant cellular debris, necrotic PMNs, and fibrin replaced the normal architecture of the node and occupied more than one-half its volume (Figures 5D and 6, B and B1). Vascular fibrin thrombi and variable amounts of hemorrhage were also present throughout the node (Figure 6, C, C1, and C2). Throughout the infection, PMNs principally associated with bacterial aggregates at the periphery of the node, but quickly degraded (Figure 6). Moderate lymphocyte hyperplasia extended toward the center of the node 24 to 36 hours after infection, increased between 36–48 hours, and then decreased at 72 hours (data not shown), which correlated with the destruction of the germinal centers of the lymph node.

Figure 5.

Progression of Y. pestis infection in the lymph node draining the inoculation site. Sections of proximal inguinal lymph nodes collected at 24 (A), 36 (B and C), and 72 (D) hours after intradermal infection stained by IHC using Y. pestis-specific antibody. Insets: magnification (×1000) of H&E-stained sections of the same lymph nodes. Gray arrowheads indicate extracellular bacteria, which stain brown by IHC. Black arrowheads indicate PMNs. The mature bubo (D) is surrounded by a gelatinous perinodal capsule (delimited by the blue arrowheads) containing bacteria. Magnification, ×10 (A and B); ×4 (C); and ×1.5 (D).

Figure 6.

Progression of histopathology in the primary bubo. Sections of proximal lymph nodes collected at 36 (A) and 72 (B and C) hours after intradermal inoculation of ∼300 Y. pestis were stained by H&E (A, A1 and A2; B, B1; and C, C1 and C2) or by Naphthol AS-D chloroacetate esterase, which stained PMNs (A3 and B2). Gray arrowheads indicate individual extracellular bacteria (A1) or bacterial aggregates, which appear as fields of blue (A3) or purple (A, A2, B1, C1, and C2). PMNs stain red by chloroacetate esterase (A3 and B2) and were localized at the periphery of the lymph node (delimited by red arrowheads in B2) and surrounded the bacterial aggregates. PMNs in H&E sections are indicated by black arrowheads (A1 and A2). Fibrin appears as deposits of pink color, indicated by green arrowheads (B, B1, C, C1, and C2). Blue arrowheads show cellular debris and condensed, degraded nuclei, indicative of necrosis or apoptosis (B1 and C2). Unlabeled scale bars, 20 μm.

Figure 7.

Histopathology of distal lymph node infected by hematogenous spread (secondary bubo). Section of an infected right maxillary lymph node was stained by H&E (A, C, and D) or by IHC using Y. pestis-specific antibody (B). Bacteria (stained brown by IHC) colocalize with areas of hemorrhage (stained red by H&E), which appeared to be the consequence of vasculitis. Infected, disrupted blood vessels, indicated by red arrowheads (C and D) contain intra- and perivascular bacterial aggregates (dark purple areas indicated by gray arrowheads), fibrin deposits (pink areas indicated by green arrowheads), and hemorrhage. Unlabeled scale bars, 20 μm.

The perinodal tissues were also affected to a degree that mirrored the severity of infection within the node. When large aggregates of bacteria extended from the periphery to the center of the node, the perinodal tissues contained low to moderate numbers of PMNs, lymphocytes, and macrophages, but no bacteria were detected. In the final stage of infection when bacteria had completely colonized the node, numerous bacteria mixed with necrotic PMN, hemorrhage, and cellular debris were present in the perinodal region. Perinodal vasculitis and vascular luminal bacteria were also noted (data not shown). The progression of the disease resulting in bubo formation can be characterized histologically as an acute, rapidly progressing necrotizing fibrinous and septic lymphadenitis and periadenitis with large extracellular masses of bacteria, leading to hemorrhage, septicemia, and necrotizing vasculitis.

Progression of Lymphadenopathy in Distal Lymph Nodes

Other major lymph nodes distal to the injection site were also affected to varying degrees. The left axillary lymph node located on the same side as the inoculation site frequently developed lymphadenitis, but the infection occurred later after inoculation (Figure 4) and was less severe. Infection of the left maxillary and right inguinal, axillary, and maxillary lymph nodes was detected in only one rat with terminal disease, and the histopathology in these distal lymph nodes differed from that seen for the more proximal left inguinal and axillary lymph nodes (Figure 7). The general architecture of the nodes was conserved, but there was marked hemorrhage (Figure 7, A, C, and D), and the bacteria were concentrated in areas of hemorrhage and within necrotic, thrombosed blood vessels. Few extracellular bacteria occurred within the lymph node parenchyma, in contrast to lymph nodes proximal to the injection site (Figure 7, B to D). Furthermore, infection of these more distal lymph nodes was not associated with periadenitis, although perinodal blood vessels contained bacteria.

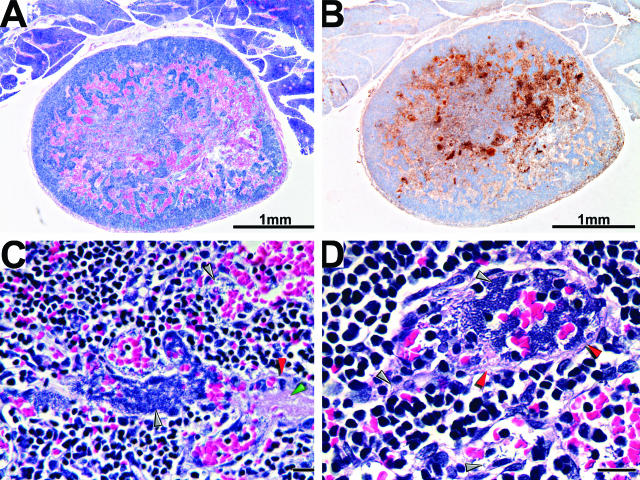

Progression of Infection in the Spleen

The sequential progression of the disease in the spleen is shown in Figures 4 and 8. Spleens of infected rats appeared normal until 36 hours after infection, containing typical areas of red pulp and white pulp characterized by periarterial lymphatic sheaths (PALS) surrounded by a prominent marginal zone and variable numbers of germinal centers (Figure 8A). Few macrophages and PMNs were present either in the red or white pulp (Figure 8, D and G). The first sign of infection was mild splenitis with an increasing number of macrophages within the marginal zone and PMNs at the periphery of marginal zone, which appeared slightly less prominent than in uninfected animals (Figure 8, B, E, and H). At the terminal stage of the disease, the architecture of the spleen was markedly altered (Figure 8C). The marginal zone decreased in thickness or was lost. The white pulp showed multifocal lymphocytolysis, resulting in moderate to complete loss of PALS and replacement by myriad bacteria mixed with abundant fibrin and cellular debris, rare PMNs, and macrophages (Figure 8, C, F, and I). The red pulp sinuses also contained bacteria mixed with abundant fibrin and cellular debris (data not shown). Splenic and perisplenic blood vessels contained fibrin mixed with Y. pestis, and multifocal moderate hemorrhage occurred in the perisplenic connective tissue (data not shown). Moderate lymphocyte hyperplasia in the spleen was seen between 36 and 48 hours after infection but then decreased, consistent with the observed lymphocytolysis (data not shown).

Figure 8.

Progression of the histopathology in the spleen. Sections of spleens collected from an uninfected rat (A, D, and G) or from infected rats 48 (B, E, and H) and 72 (C, F, and I) hours after infection were stained by H&E (A to C), by IHC using an anti-rat mononuclear cell antibody (D to F), or by Naphthol AS-D chloroacetate esterase assay to detect PMNs (G to I). Macrophages (stained brown in D to F) and PMNs (stained red in G to I) were concentrated at the marginal zone and are indicated by red and green arrowheads, respectively. Bacterial aggregates close to the arteriole of the PALS appear purple (C), light brown (F), or blue (I) and are indicated by gray arrowheads. P, periarterial lymphatic sheath; M, marginal zone. Scale bar, 500 μm (A to C), 100 μm (D and E), and 20 μm (F to I).

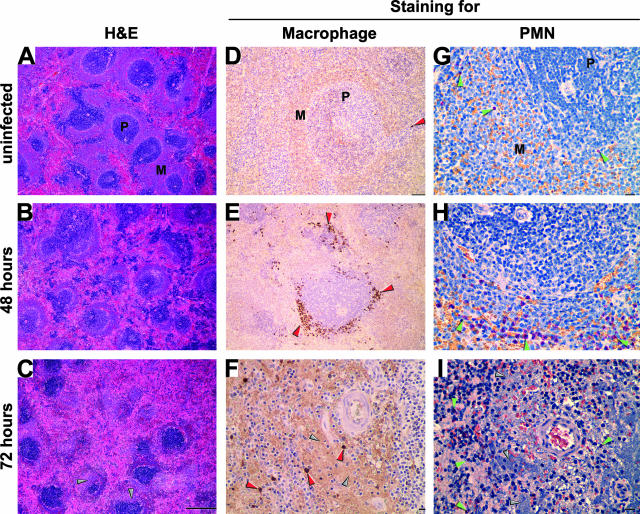

The Innate Immune Response to Bubonic Plague

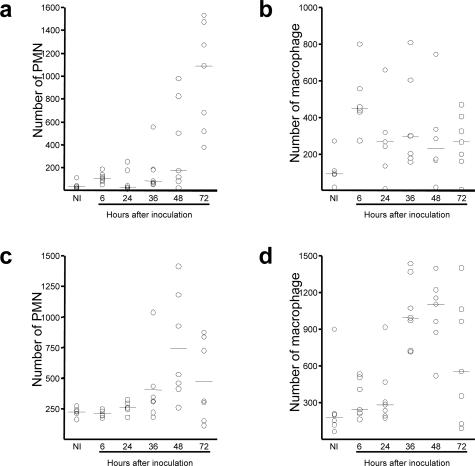

Current models of Yersinia pathogenesis emphasize the role of bacterial virulence factors that act to paralyze the phagocytic machinery of innate immune cells and to suppress the inflammatory response (reviewed in21–23), but in vivo evidence for these activities during bubonic plague is lacking. We found little evidence of PMN recruitment to the primary bubo until 36 hours after infection. PMN numbers increased between 36 and 72 hours but were low compared with the number of bacteria (Figures 5, 6, and 9). Typical abscesses did not develop, even though PMNs colocalized with the bacterial aggregates (Figures 5 and 6A3). Infection of the spleen was similarly characterized by a lack of purulent abscess formation (Figures 8 and 9).

Figure 9.

Kinetics of PMN and macrophage recruitment to lymph node (a and b) and spleen (c and d). Open circles indicate the number of cells in one entire lymph node section or in 50 fields of a spleen section from individual rats, counted at 600× magnification. NI, noninfected.

Low numbers of macrophages were recruited to the infected primary lymph node early in the infection, appearing 18 hours before PMN recruitment. In contrast to PMNs, macrophage numbers decreased the day after the infection and remained at a level only slightly higher than normal (Figure 9). The number of macrophages in the spleen peaked at 48 hours after infection and then decreased (Figures 8, E and F, and 9d).

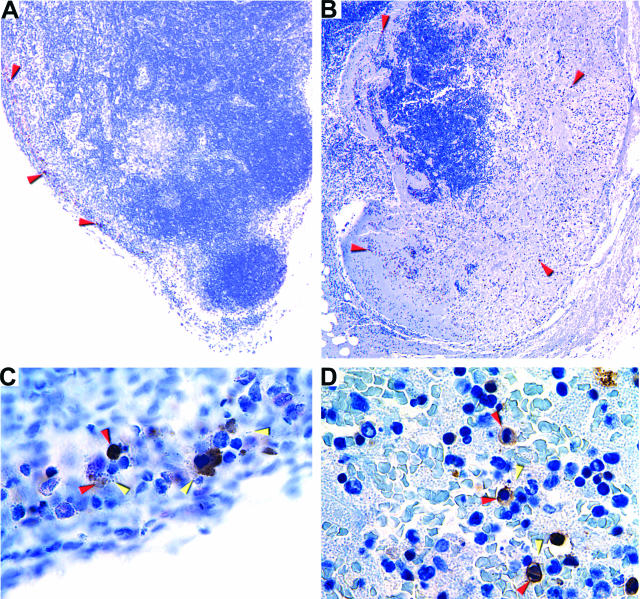

The enteropathogenic Yersinia species have been shown to trigger apoptosis of macrophages, and this activity is important for virulence.24–26 To determine whether apoptosis occurred during bubonic plague, we compared the number of caspase-3-positive apoptotic cells in sections of uninfected and infected inguinal lymph nodes from three rats. Uninfected controls and samples collected 6 and 24 hours after infection contained only 1 to 22 apoptotic cells. However, sections of lymph nodes collected 36, 48, and 72 hours after infection contained 7 to 114, 9 to 600, and 384 to 802 apoptotic cells, respectively. The increase in caspase-positive cells correlated with the increase in bacterial numbers in the infected lymph nodes and with the decrease in macrophages (Figure 9b). In addition, most of the apoptotic cells were in areas of the lymph nodes colonized by bacteria (Figure 10). These results support the hypothesis that Y. pestis-induced apoptosis occurs in the bubo.

Figure 10.

Apoptosis in the primary bubo. Caspase-3-positive cells in sections of inguinal lymph nodes collected at 36 (A and C) and 72 (B and D) hours after infection were detected by IHC. Brown-colored apoptotic cells colocalized with Y. pestis in the marginal sinus (A and C) and later in colonized regions throughout the lymph node parenchyma (B and D). Red and yellow arrowheads indicate examples of apoptotic cells and bacteria, respectively. Original magnification, ×30 (A); ×80 (B); ×600 (C and D).

Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines were not detected in the blood of rats between 6 and 36 hours, even when low-level bacteremia was present. In contrast, IFN-γ, TNF-α, or IL-10 was detected in seven of eight rats after 48 to 72 hours (Table 1). Unlike TNF-α and IL-10, increased IFN-γ levels occurred in the serum of all bacteremic rats and correlated with the level of bacteremia except when the bacterial load exceeded 107/ml.

Table 1.

Serum Cytokine Levels of Rats 48 to 72 Hours after Infection with Y. pestis

| Rat no. | Bacteremia level* | TNF-α† | IL-10† | IFN-γ† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | <1.3 | <40 | <50 | <40 |

| 2 | 3.4 | <40 | <50 | 802 |

| 3 | 4.9 | <40 | <50 | 356 |

| 4 | 5.0 | 432 | <50 | 718 |

| 5 | 5.0 | <40 | <50 | 734 |

| 6 | 6.8 | 333 | 420 | 7057 |

| 7 | 7.3 | 127 | <50 | 3740 |

| 8 | 9.0 | 172 | <50 | 404 |

log10 Y. pestis CFU/ml of blood.

pg/ml of blood.

Hematology

The hematological aspects of plague in the Brown Norway rat are shown in Table 2. The total WBC count between 6 and 24 hours after inoculation was normal, with a median of ∼8000 WBC/μl (range, 3900 to 12,700), and the percentage of PMNs was within the normal range. At 36 hours, the median WBC count was unchanged, but a slight increase in the percentage of PMNs was noted. After 36 hours, >18,000 WBC/μl (>50% of which were mature and immature PMNs) were seen in some animals. Thrombocytopenia (platelet count <80,000/μl) occurred in some rats at 72 hours postinfection. Increased numbers of total WBC, PMNs, and thrombocytopenia correlated with the level of bacteremia. These hematological responses resemble those typical of human plague.27 No abnormalities in serum total protein, fibrinogen, or glucose levels were detected during the course of disease (data not shown).

Table 2.

WBC and Platelets in Peripheral Blood of Rats Infected with Y. pestis

| Hours after infection | Bacteremia level* | Total WBC† | % PMN | Platelets† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | <1.3 | 8.2 (3.1–13.2) | 13 (9–15) | nd |

| 6 | <1.3 | 8.7 (3.9–12.5) | 9 (5–13) | 600 (510–800) |

| 24 | <1.3 | 8.1 (5.7–12.7) | 17 (10–18) | 675 (640–710) |

| 36 | 2.8 (<1.3–4.8) | 6.0 (5.3–11.7) | 21 (8–28) | 580 (460–680) |

| 48 | 4.9 (<1.3–6.8) | 11.9 (3.5–18.5) | 36 (19–55) | 445 (160–700) |

| 72 | 6.2 (3.4–9.0) | 11.7 (4.3–19.8) | 54 (33–69) | 219 (65–540) |

log10 Y. pestis CFU/ml of blood.

(×103/μl of blood).

The values of 3–7 rats were used to determine the median (range) for each time point. nd, not done.

Discussion

During the last plague pandemic at the beginning of the 20th century, the symptomatology and pathology of human bubonic plague was described in several classic studies.1–4,27,28 The prominent clinical feature was the abrupt appearance of lymphadenitis that led to the pathognomonic bubo, a grossly enlarged lymph node that when palpated had a boggy or elastic consistency but with a hard central core. Depending on the fleabite site, inguinal, axillary, and cervical buboes were most common and were so painful that patients were reluctant to move the adjacent limb. On autopsy, the bubo showed an unmistakable pathology. The enlarged node itself was hemorrhaged and necrotic, blood vessels were thrombosed, and the lymphoid cells and normal architecture were destroyed and replaced by massive numbers of bacteria and fibrin. The periglandular tissues were also inflamed and contained large numbers of bacteria within a sero-hemorrhagic exudate of gelatinous consistency. Adjacent lymph nodes often had similar pathology but to a lesser degree, particularly in the extent of periadenitis. The two types of local affected nodes were termed primary buboes of the first and second order, respectively. Secondary buboes in areas distal to the primary lymph nodes were also identified. These were infected and enlarged, but seldom showed hemorrhage, necrosis, or surrounding edema.

Based on comparative autopsy findings from patients in which the disease was considered to be more or less advanced, the following scenario of the progression of bubonic plague was deduced.1–4 The bacteria enter the lymphatic system from the infected fleabite site and are carried to the regional draining lymph node, where they multiply and produce the primary bubo of first order. Continued spread through the lymphatic vessels to contiguous lymph nodes produce primary buboes of the second order. Although often accompanied by early transient bacteremia, the infection is initially contained in the regional lymph nodes. Eventually, however, Y. pestis spreads via efferent lymphatic channels to the thoracic duct to enter the blood stream. Spleen, liver, and secondary bubo infections are then established by systemic hematogenous spread. When these secondary defenses are overcome, death results from uncontrolled septicemia, endotoxic shock, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

The rat model of bubonic plague described here closely resembles human disease and provides explicit information regarding the chronological progression of pathogenesis and host response. Y. pestis first appeared in the marginal sinus of the draining lymph node within 6 hours after ID inoculation, indicating that dissemination occurred through afferent lymph channels and not through the blood. It has been proposed that Y. pestis is initially taken up by macrophages or other phagocytic cells in the dermis and transported within these cells to the draining lymph node.29 If so, the initial intracellular phase of Y. pestis must end before or at the time of arrival to the lymph node. We were unable to conclusively identify intracellular Y. pestis in the marginal sinus, although extracellular bacteria were present (Figure 5). In addition, antigen-presenting cells containing ingested bacteria would be expected to transport bacteria to the germinal centers of the lymph node.30,31 However, infection did not initiate there but in the periphery. The bacteria multiplied rapidly and invaded the lymph node parenchyma multifocally from the marginal and medullary sinuses, eventually filling the node and causing the massive cytolysis, hemorrhage, necrosis, and periadenitis characteristic of the primary bubo.

Detectable bacteremia occurred only after primary lymph node colonization and corresponded temporally with spleen and secondary lymph node infection. Notably, the histopathology in the secondary buboes was clearly different from the primary bubo. Y. pestis was detected first next to thrombosed blood vessels in the medulla, indicating a hematogenous route of infection (Figure 7). Our results thus confirm previous models that invasion proceeds first to the draining lymph node and that septicemia occurs after this barrier is breached. Seeding of the blood stream by continued lymphatic spread into the thoracic duct has been proposed in most models,1,3,4,15 but invasion through damaged blood vessels in the node or perinodal tissue is also consistent with our results.

The temporal progression of the infection in the spleen, which has not been described previously in humans or other animals, was characterized in this study. Although bacteria were difficult to visualize directly in the spleen at early stages, detection of PMNs and macrophages at the marginal zone of the white pulp (Figure 8) suggests that Y. pestis invades the spleen from arterioles in the PALS to first infect the white pulp. Later in infection, large numbers of bacteria were present in the white pulp and then in the red pulp. This progression fits the normal blood flow in the spleen and the structure of this organ, in which the marginal zone is typically the initial site of localization of bacteria and other antigens due to its fine meshed reticulum.32–34

A rather limited and ineffective cellular response to plague has often been noted,23,35–37 and we observed this also. Unlike the more suppurative and granulomatous cellular host response seen in lymphadenitis caused by the less fulminant enteropathogens Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and Yersinia enterocolitica, PMN and macrophage numbers at the infection sites decreased as the disease progressed. Three mechanisms by which the pathogenic yersiniae attenuate the innate immune response have been identified, which are encoded by the 70-kb virulence plasmid common to Y. pestis, Y. pseudotuberculosis, and Y. enterocolitica. Direct contact between yersiniae and phagocytic cells induces type III-dependent secretion of cytotoxic and apoptotic bacterial Yop proteins into the eukaryotic cell cytoplasm, which 1) block phagocytosis; 2) induce apoptosis; and 3) modulate cytokine networks to inhibit the inflammatory response.21,26,38–43 In mouse models of Y. pestis infection, the secreted LcrV antigen has also been shown to suppress induction of the proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IFN-γ, presumably by inducing expression of IL-10 and possibly other anti-inflammatory cytokines.23,36,37,44–46

Our results provide some support for these models. We observed an initial recruitment of inflammatory cells and evidence of edema in both lymph node and spleen, indicative of an inflammatory response early in infection (Figures 5, 6, and 8). This response was ineffective, however, and no evidence of abscess or granuloma formation was seen. Instead, immune cells were destroyed, and massive numbers of extracellular bacteria grew in the lymphoid tissue and rapidly spread to the blood. Large numbers of caspase-3-positive cells were detected in infected lymph nodes (Figure 10), suggesting that Yop-mediated apoptosis occurs in the bubo, as has been demonstrated in mesenteric lymph nodes infected with Y. pseudotuberculosis.25 Although the altered morphology of the apoptotic cells did not permit their identification, apoptosis coincided with decreased macrophage numbers in the infected lymph node (Figures 9 and 10). Whatever the mechanism, the observed attenuation of the initial macrophage response could reduce PMN recruitment and other aspects of the inflammatory response in the infected lymph node.

We monitored serum levels of three cytokines, the induction of which is hypothesized to be modulated by Y. pestis.23,36,37,39,44 TNF-α was detectable only after high bacteremia had developed. Elevated levels of IFN-γ were also present in the serum of bacteremic rats 48 hours after infection, but IL-10 was detected in only one rat, which also showed elevated TNF-α and IFN-γ (Table 1). In previous studies, serum IFN-γ was never detected in bacteremic mice infected intravenously with Y. pestis, and TNF-α was detected only in moribund mice.23,36,37 These differences may be due to the use in the previous models of direct intravenous injection of an attenuated Y. pestis strain or to differential responses of the rat and mouse immune systems. Septic shock caused by other gram-negative bacteria is typified by a sequence of elevated serum levels first of TNF-α and other proinflammatory cytokines, followed consecutively by increased IFN-γ and IL-10 levels.47 Because serum cytokine levels may inadequately mirror cytokine dynamics at local infection sites, in future studies, it will be important to characterize cytokine and inflammatory cell profiles in lymph nodes and spleen at early stages of infection.

In addition to cytotoxicity caused by the type III secretion system, two other Y. pestis-specific factors, the antiphagocytic F1 capsule and the cell-surface plasminogen activator, likely contribute to pathogenesis.14,35 The combination of all of these virulence factors likely result in immunosuppression, inhibition of phagocytes and antigen-presenting cells, destruction of lymphocytes in germinal centers before an adaptive immune response can develop, and systemic invasion, all contributing to the unchecked replication of Y. pestis and the fulminant progression of plague.

Conclusions

The progression, kinetics, and histopathology of Y. pestis infection in the BN strain of R. norvegicus closely resembles human bubonic plague, thus providing a practical in vivo system to study the mechanisms of plague pathogenesis and immunity. The rat model should be useful in pathogenesis studies to examine the role of Y. pestis virulence factors at each stage of disease at the tissue, cellular, and subcellular levels. Furthermore, current models for the mechanisms by which Y. pestis counters the host immune response rely mainly on inferences drawn from studies using the enteropathogens Y. pseudotuberculosis and Y. enterocolitica or attenuated Y. pestis strains injected directly into the blood stream.21–23 These models can be explicitly evaluated in the rat model by analysis of the immune response after ID injection or flea-borne transmission of wild-type Y. pestis, particularly in the primary lymph node, where the battle against plague is won or lost.

Acknowledgments

We thank James Musser, John Portis, and David Erickson for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to B. Joseph Hinnebusch, Laboratory of Human Bacterial Pathogenesis, Rocky Mountain Laboratories, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Hamilton, MT 59840. E-mail: jhinnebusch@niaid.nih.gov.

Supported in part by a New Scholars Award in Global Infectious Diseases (to B.J.H.) from the Ellison Medical Foundation.

Current address of B.B.G.: Institute for Antiviral Research, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322.

References

- Pollitzer R. Geneva: World Health Organization,; Plague. 1954 [Google Scholar]

- Butler T. Plague and Other Yersinia Infections. New York: Plenum Press,; 1983 [Google Scholar]

- Crowell BC. Pathologic anatomy of bubonic plague. Philipp J Sci. 1915;10:249–306. [Google Scholar]

- Flexner S. The pathology of bubonic plague. Am J Med Sci. 1901;122:396–416. [Google Scholar]

- Donavan JE, Ham D, Fukui GM, Surgalla MJ. Role of the capsule of Pasteurella pestis in bubonic plague in the guinea pig. J Infect Dis. 1961;109:154–157. doi: 10.1093/infdis/109.2.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornil J, Poursines Y, Moustardier G. La peste expérimental du cobaye et du rat blanc (données anatomo-cliniques). Méd Trop. 1944;4:111–129. [Google Scholar]

- Kitasato S. The bacillus of bubonic plague. Lancet. 1894;ii:428–429. [Google Scholar]

- Devignat R, Shoetter M, Gille-Simul S. Quelques considérations sur la peste du cobaye. Rec Trav Sci Méd Congo Belge. 1945;4:25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Markenson J, Ben-Efraim S. Comportement in vivo des souches de Pasteurella pestis en relation avec leur éfficacité comme vaccins vivants. Ann Inst Pasteur. 1969;117:196–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer KF. Immunity in plague: a critical consideration of some recent studies. J Immunol. 1950;64:139–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TH, Meyer KF. Susceptibility and antibody response of Rattus species to experimental plague. J Infect Dis. 1974;129(Suppl):S53–S61. doi: 10.1093/infdis/129.supplement_1.s62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SM, Day F, Stagg AJ, Williamson ED. Protection conferred by a fully recombinant sub-unit vaccine against Yersinia pestis in male and female mice of four inbred strains. Vaccine. 2000;19:358–366. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00108-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath DG, Anderson GW, Jr, Mauro JM, Welkos SL, Andrews GP, Adamovicz J, Friedlander AM. Protection against experimental bubonic and pneumonic plague by a recombinant capsular F1-V antigen fusion protein vaccine. Vaccine. 1998;16:1131–1137. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)80110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry RD, Fetherston JD. Yersinia pestis-etiologic agent of plague. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:35–66. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jawetz E, Meyer KF. The behaviour of virulent and avirulent Pasteurella pestis in normal and immune experimental animals. J Infect Dis. 1943;74:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs RA, Weinstock GM, Metzker ML, Muzny DM, Sodergren EJ, Scherer S, Scott G, Steffen D, Worley KC, Burch PE, Okwuonu G, Hines S, Lewis L, DeRamo C, Delgado O, Dugan-Rocha S, Miner G, Morgan M, Hawes A, Gill R, Celera, Holt RA, Adams MD, Amanatides PG, Baden-Tillson H, Barnstead M, Chin S, Evans CA, Ferriera S, Fosler C, Glodek A, Gu Z, Jennings D, Kraft CL, Nguyen T, Pfannkoch CM, Sitter C, Sutton GG, Venter JC, Woodage T, Smith D, Lee HM, Gustafson E, Cahill P, Kana A, Doucette-Stamm L, Weinstock K, Fechtel K, Weiss RB, Dunn DM, Green ED, Blakesley RW, Bouffard GG, De Jong PJ, Osoegawa K, Zhu B, Marra M, Schein J, Bosdet I, Fjell C, Jones S, Krzywinski M, Mathewson C, Siddiqui A, Wye N, McPherson J, Zhao S, Fraser CM, Shetty J, Shatsman S, Geer K, Chen Y, Abramzon S, Nierman WC, Havlak PH, Chen R, Durbin KJ, Egan A, Ren Y, Song XZ, Li B, Liu Y, Qin X, Cawley S, Cooney AJ, D’Souza LM, Martin K, Wu JQ, Gonzalez-Garay ML, Jackson AR, Kalafus KJ, McLeod MP, Milosavljevic A, Virk D, Volkov A, Wheeler DA, Zhang Z, Bailey JA, Eichler EE, Tuzun E, Birney E, Mongin E, Ureta-Vidal A, Woodwark C, Zdobnov E, Bork P, Suyama M, Torrents D, Alexandersson M, Trask BJ, Young JM, Huang H, Wang H, Xing H, Daniels S, Gietzen D, Schmidt J, Stevens K, Vitt U, Wingrove J, Camara F, Mar Alba M, Abril JF, Guigo R, Smit A, Dubchak I, Rubin EM, Couronne O, Poliakov A, Hubner N, Ganten D, Goesele C, Hummel O, Kreitler T, Lee YA, Monti J, Schulz H, Zimdahl H, Himmelbauer H, Lehrach H, Jacob HJ, Bromberg S, Gullings-Handley J, Jensen-Seaman MI, Kwitek AE, Lazar J, Pasko D, Tonellato PJ, Twigger S, Ponting CP, Duarte JM, Rice S, Goodstadt L, Beatson SA, Emes RD, Winter EE, Webber C, Brandt P, Nyakatura G, Adetobi M, Chiaromonte F, Elnitski L, Eswara P, Hardison RC, Hou M, Kolbe D, Makova K, Miller W, Nekrutenko A, Riemer C, Schwartz S, Taylor J, Yang S, Zhang Y, Lindpaintner K, Andrews TD, Caccamo M, Clamp M, Clarke L, Curwen V, Durbin R, Eyras E, Searle SM, Cooper GM, Batzoglou S, Brudno M, Sidow A, Stone EA, Payseur BA, Bourque G, Lopez-Otin C, Puente XS, Chakrabarti K, Chatterji S, Dewey C, Pachter L, Bray N, Yap VB, Caspi A, Tesler G, Pevzner PA, Haussler D, Roskin KM, Baertsch R, Clawson H, Furey TS, Hinrichs AS, Karolchik D, Kent WJ, Rosenbloom KR, Trumbower H, Weirauch M, Cooper DN, Stenson PD, Ma B, Brent M, Arumugam M, Shteynberg D, Copley RR, Taylor MS, Riethman H, Mudunuri U, Peterson J, Guyer M, Felsenfeld A, Old S, Mockrin S, Collins F. Genome sequence of the Brown Norway rat yields insights into mammalian evolution. Nature. 2004;428:493–521. doi: 10.1038/nature02426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TH, Foster LE, Meyer KF. Experimental comparison of the immunogenicity of antigens in the residue of ultrasonated avirulent Pasteurella pestis with the vaccine prepared with the killed virulent whole organisms. J Immunol. 1961;87:64–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett CO, Deak E, Isherwood KE, Oyston PC, Fischer ER, Whitney AR, Kobayashi SD, DeLeo FR, Hinnebusch BJ. Transmission of Yersinia pestis from an infectious biofilm in the flea vector. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:783–792. doi: 10.1086/422695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidsohn I, Nelson DA, Henry JB. Blood. Davidsohn I, Henry JB, editors. Philadelphia: WB Saunders,; Clinical Diagnosis by Laboratory Methods. (ed 15) 1974:pp 100–310. [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch BJ. Interactions of Yersinia pestis with its flea vector that lead to the transmission of plague. Gillespie S, Smith G, Osbourn A, editors. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press,; Microbe-Vector Interactions in Vector-Borne Disease. 2004:pp 331–343. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelis GR, Boland A, Boyd AP, Geuijen C, Iriarte M, Neyt C, Sory MP, Stainier I. The virulence plasmid of Yersinia, an antihost genome. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1315–1352. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1315-1352.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruckdeschel K, Rouot B, Heesemann J. Type III protein secretion and inhibition of NF-kB. Henderson B, Oyston PFC, editors. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press,; Bacterial Evasion of Host Immune Responses. 2003:pp 279–294. [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker RR. Interleukin-10 and inhibition of innate immunity to Yersiniae: roles of Yops and LcrV (V antigen). Infect Immun. 2003;71:3673–3681. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.7.3673-3681.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills SD, Boland A, Sory MP, van der Smissen P, Kerbourch C, Finlay BB, Cornelis GR. Yersinia enterocolitica induces apoptosis in macrophages by a process requiring functional type III secretion and translocation mechanisms and involving YopP, presumably acting as an effector protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12638–12643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monack DM, Mecsas J, Bouley D, Falkow S. Yersinia-induced apoptosis in vivo aids in the establishment of a systemic infection of mice. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2127–2137. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruckdeschel K, Roggenkamp A, Lafont V, Mangeat P, Heesemann J, Rouot B. Interaction of Yersinia enterocolitica with macrophages leads to macrophage cell death through apoptosis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4813–4821. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4813-4821.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler T, Bell WR, Nguyen Ngoc L, Nguyen Dinh T, Arnold K. Yersinia pestis infection in Vietnam. I. Clinical and hematologic aspects. J Infect Dis. 1974;129(Suppl):S78–S84. doi: 10.1093/infdis/129.supplement_1.s78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler T. A clinical study of bubonic plague: observations of the 1970 Vietnam epidemic with emphasis on coagulation studies, skin histology and electrocardiograms. Am J Med. 1972;53:268–276. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(72)90168-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titball RW, Hill J, Lawton DG, Brown KA. Yersinia pestis and plague. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:104–107. doi: 10.1042/bst0310104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimber I, Dearman RJ, Cumberbatch M, Huby RJ. Langerhans cells and chemical allergy. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:614–619. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tablin F, Chamberlain JK, Weiss L. The microanatomy of the spleen: mechanisms of splenic clearance. Bowdler AJ, editor. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press,; The Complete SpleenStructure, Function, and Clinical Disorders. 2002:pp 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Groom AC, MacDonald IC, Schmidt EE. Splenic microcirculatory blood flow and function with the respect to red blood cells. Bowdler AJ, editor. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press,; The Complete SpleenStructure, Function, and Clinical Disorders. 2002:pp 23–50. [Google Scholar]

- Dailey MO. The immune functions of the spleen. Bowdler AJ, editor. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press,; The Complete SpleenStructure, Function, and Clinical Disorders. 2002:pp 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker RR: Yersinia pestis and bubonic plague: the prokaryotes, an evolving electronic resource for the microbiological community. Edited by M Dworkin, S Falkow, E Rosenberg, KH Schleifer, E Stackebrandt. [online] cited 31 Jul 2003, http://et.springer-ny.com:8080/prokPUB/index.htm [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima R, Brubaker RR. Association between virulence of Yersinia pestis and suppression of gamma interferon and tumor necrosis factor alpha. Infect Immun. 1993;61:23–31. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.1.23-31.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima R, Motin VL, Brubaker RR. Suppression of cytokines in mice by protein A-V antigen fusion peptide and restoration of synthesis by active immunization. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3021–3029. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3021-3029.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monack DM, Mecsas J, Ghori N, Falkow S. Yersinia signals macrophages to undergo apoptosis and YopJ is necessary for this cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10385–10390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruckdeschel K, Machold J, Roggenkamp A, Schubert S, Pierre J, Zumbihl R, Liautard JP, Heesemann J, Rouot B. Yersinia enterocolitica promotes deactivation of macrophage mitogen-activated protein kinases extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1/2, p38, andc-Jun NH2-terminal kinase: correlation with its inhibitory effect on tumor necrosis factor-alpha production. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15920–15927. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.15920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer LE, Hobbie S, Galan JE, Bliska JB. YopJ of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is required for the inhibition of macrophage TNF-alpha production and downregulation of the MAP kinases p38 and JNK. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:953–965. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland A, Cornelis GR. Role of YopP in suppression of tumor necrosis factor alpha release by macrophages during Yersinia infection. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1878–1884. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.1878-1884.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schesser K, Spiik AK, Dukuzumuremyi JM, Neurath MF, Pettersson S, Wolf-Watz H. The yopJ locus is required for Yersinia-mediated inhibition of NF-kappaB activation and cytokine expression: yopJ contains a eukaryotic SH2-like domain that is essential for its repressive activity. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:1067–1079. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth K, Palmer LE, Bao ZQ, Stewart S, Rudolph AE, Bliska JB, Dixon JE. Inhibition of the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase superfamily by a Yersinia effector. Science. 1999;285:1920–1923. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5435.1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedialkov YA, Motin VL, Brubaker RR. Resistance to lipopolysaccharide mediated by the Yersinia pestis V antigen-polyhistidine fusion peptide: amplification of interleukin-10. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1196–1203. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1196-1203.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sing A, Rost D, Tvardovskaia N, Roggenkamp A, Wiedemann A, Kirschning CJ, Aepfelbacher M, Heesemann J. Yersinia V-antigen exploits toll-like receptor 2 and CD14 for interleukin 10-mediated immunosuppression. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1017–1024. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welkos S, Friedlander A, McDowell D, Weeks J, Tobery S. V antigen of Yersinia pestis inhibits neutrophil chemotaxis. Microb Pathog. 1998;24:185–196. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1997.0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opal SM, Cohen J. Clinical Gram-positive sepsis: does it fundamentally differ from Gram-negative bacterial sepsis? Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1608–1616. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199908000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]