Abstract

Recent evidence has suggested that an abnormal reactivation of the cell cycle may precede and cause the hyperphosphorylation and filament formation of tau protein in Alzheimer’s disease and other tauopathies. Here we have analyzed the expression and/or activation of proteins involved in cell-cycle progression in the brain and spinal cord of mice transgenic for mutant human P301S tau protein. This mouse line recapitulates the essential molecular and cellular features of the human tauopathies, including hyperphosphorylation and filament formation of tau protein. None of the activators and co-activators of the cell cycle tested were overexpressed or activated in 5-month-old transgenic mice when compared to controls. By contrast, the levels of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 were increased in brain and spinal cord of transgenic mice. Both inhibitors accumulated in the cytoplasm of nerve cells, the majority of which contained inclusions made of hyperphosphorylated tau protein. A similar staining pattern for p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 was also present in the frontal cortex from a case of FTDP-17 with the P301L tau mutation. Thus, reactivation of the cell cycle was not involved in tau hyperphos-phorylation and filament formation, consistent with expression of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 in tangle-bearing nerve cells.

The most common neurodegenerative diseases are characterized by the presence of abnormal filamentous protein inclusions in the brain.1 In Alzheimer’s disease (AD), these inclusions are made of hyperphosphorylated tau protein. Together with the extracellular β-amyloid deposits, they constitute the defining neuropathological characteristics of AD. Tau inclusions, in the absence of extracellular deposits, are characteristic of progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, Pick’s disease, argyrophilic grain disease, Parkinson-dementia complex of Guam, and frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17).2,3 The identification of mutations in Tau in FTDP-17 has established that dysfunction of tau protein is central to the neurodegenerative process.4–6 In all these diseases, tau protein is hyperphosphorylated and in an abnormal filamentous form, with hyperphosphorylation at most sites appearing to precede assembly into filaments. It appears likely, therefore, that similar mechanisms lead to tau hyperphosphorylation in AD and other diseases with filamentous tau deposits. However, the mechanisms by which tau becomes hyperphosphorylated are not well understood.

Throughout the past decade, a body of work on AD has reported that cell-cycle markers are abnormally expressed in nerve cells with filamentous tau deposits. These markers include proteins involved in the G0/G1 transition, such as cyclin D and Cdk4/Cdk6; some of their substrates, such as the retinoblastoma protein; and the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p15, p16, p18, and p19.7–13 Markers of the G1/S transition, such as cyclin E and Cdc25A, were also found to be abnormally expressed in degenerating nerve cells.13–15 Furthermore, regulators of the G2/M transition, such as cyclin B, Cdc2, Cdc25B, Polo kinase, Myt1/Wee1, and p27Kip1, and some mitotic epitopes, such as phosphorylated histone H3, phosphorylated RNA polymerase II, PCNA, Ki67, and MPM2, were found to co-localize with hyperphosphorylated tau protein.8,14,16–27 The expression of mitotic epitopes appeared to precede hyperphosphorylation and aggregation of tau protein, suggesting a possible cause-and-effect relationship.28,29 This was supported by studies showing AD-like phosphorylation of tau protein in mitotically active cells30–33 and the phosphorylation of recombinant tau by CDKs in vitro.34 Importantly, experimental studies have established that an inappropriate re-entry into the cell cycle results in nerve cell death. Thus, expression of SV40 T antigen in cerebellar Purkinje cells and rod photoreceptors of transgenic mice caused unscheduled cell cycle re-entry and cell death.35,36 Reactivation of the cell-cycle machinery is believed to play an important role in the apoptotic death of postmitotic neurons.

Taken together, these findings raised the possibility that an inappropriate re-entry into the cell cycle might be directly responsible for the hyperphosphorylation of tau and the neurodegeneration characteristic of AD. This may also apply to other diseases with tau deposits because an abnormal activation of cell-cycle markers has been described in progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, Pick’s disease, Parkinson-dementia complex of Guam, and FTDP-17.20

The above findings are correlational, having been obtained mostly using postmortem brain tissue from individuals with end-stage clinical disease of long duration. One way to throw fresh light on this issue may be to use experimental animal models to look at possible mechanistic links between the expression of cell-cycle markers, hyperphosphorylation of tau and neurodegeneration. In recent years, mice transgenic for human tau with missense mutations of FTDP-17 have been produced.37–44 Some of these lines replicate the essential molecular and cellular features of the human tauopathies, including hyperphosphorylation, abundant filament formation, and nerve cell death.37,41

Here we have used a line of mice transgenic for human P301S tau protein41 to study the expression of cell-cycle markers. We found no evidence for an abnormal expression or mislocalization of activators and co-activators of the cell cycle in brain and spinal cord of 5-month-old human P301S tau mice. However, two cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors, p21Cip1 and p27Kip1, were elevated in transgenic mouse brain and spinal cord. They accumulated in the cytoplasm of nerve cells, the majority of which contained tau inclusions. A similar staining pattern was observed in the frontal cortex from a case of FTDP-17 with the P301L tau mutation.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Antibodies

Five-month-old homozygous mice transgenic for human P301S tau protein and age-matched C57BL/6J control mice were used. We used the phosphorylation-dependent anti-tau antibodies AT8 (Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium), AT100 (Innogenetics), and phospho-tau S422 (BioSource Europe, Nivelle, Belgium), as well as the phosphorylation-independent anti-tau antibody BR134. AT8 recognizes tau protein phosphorylated at S202 and T205, AT100 requires phosphorylation of both T212 and S214 in tau,45,46 and phospho-tau S422 recognizes tau protein phosphorylated at S422. BR134 recognizes all tau isoforms, irrespective of phosphorylation.47 In addition, a large panel of antibodies directed against cell-cycle proteins and related proteins was used (Table 1). They included antibodies to cyclins (A, B, D1, and E), CDKs 1 and 2, Cdc25A, Cdc25C, Cks1, Myt1/Wee1, Polo kinase, CDK inhibitors (p16Ink4a, p18Ink4c, p19ARF, p21Cip1, and p27Kip1), ORC1, Aurora2, MPM2, phospho-histone H3, mitotic cells, and the retinoblastoma (Rb) protein.

Table 1.

Antibodies Used

| Antibodies | Dilutions used for immunohistochemistry | Dilutions used for immunoblots | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-Tau | |||

| BR134 | 1/500 | 1/5000 | M. Goedert |

| AT8 | 1/500 | 1/1000 | Innogenetics |

| AT100 | 1/500 | 1/1000 | Innogenetics |

| Phospho Tau (Ser422) | 1/500 | 1/1000 | Biosource |

| Anti-CDKs | |||

| Cdk2 | 1/100 | 1/200 | H-298/Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA) |

| Phospho-Cdk2 (Thr160) | 1/50 | 1/100 | Santa Cruz |

| Cdk1 (Cdc2) | 1/250 | 1/1000 | Upstate Biotechnology (Dundee, UK) |

| Phospho-Cdk1 (Thr161) | 1/200 | 1/1000 | Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA) |

| Anti-Cyclins | |||

| Cyclin A | 1/100 | 1/200 | H-432/Santa Cruz |

| 1/100 | 1/200 | ab7956/Abcam (Cambridge, UK) | |

| Cyclin B | 1/100 | 1/200 | H-433/Santa Cruz |

| 1/250 | 1/2000 | Cell Signaling | |

| Cyclin D1 | 1/70 | 1/200 | H-295/Santa Cruz |

| Cyclin E | 1/70 | 1/200 | M20/Santa Cruz |

| Anti-Cdk activators and inhibitors | |||

| Cdc25 A | 1/50 | 1/200 | M-191/Santa Cruz |

| Cdc25 C | 1/50 | 1/200 | TC-15/Upstate Biotechnology |

| Phospho-Cdc25 C (Thr48) | 1/100 | 1/1000 | Cell Signaling |

| CKs1 p9 | 1/50 | n.d. | FL-79/Santa Cruz |

| Myt1/Wee1 | 1/200 | 1/1000 | Cell Signaling |

| Polo kinase (Plk) | 1/200 | 1/1000 | NT/Upstate Biotechnology |

| p16 Ink4 | 1/50 | n.d. | M-156/Santa Cruz |

| p18 Ink4 | 1/50 | n.d. | N-20/Santa Cruz |

| p19 ARF | 1/50 | n.d. | M-20/Santa Cruz |

| p21 Cip1 | 1/50 | 1/200 | F-5/Santa Cruz |

| 1/50 | 1/200 | Waf1 (Ab4)/Oncogene Research Products, (San Diego, CA) | |

| p27 Kip1 | 1/100 | 1/1000 | Cell Signaling |

| 1/50 | 1/200 | DCS-72/Sigma-Aldrich (Poole, UK) | |

| Other markers | |||

| Anti-ATM | 1/70 | 1/200 | Sc-23922/Santa Cruz |

| Anti-ORC1 | 1/50 | n.d. | 7F6/1/Neomarkers (Fremont, CA) |

| Anti-Aurora 2 | 1/100 | n.d. | Cell Signaling |

| Anti-MPM2 | 1/50 | n.d. | Upstate Biotechnology |

| Anti-Phospho-histone H3 (Ser10) | 1/50 | n.d. | Cell Signaling |

| Anti-mitotic cells | 1/100 | n.d. | ab8956/Abcam |

| Anti-Rb | 1/50 | 1/200 | M153/Santa Cruz |

| Anti-Phospho-Rb (Ser795) | 1/100 | 1/1000 | Cell Signaling |

| Anti-β actin | n.d. | 1/5000 | Sigma Clone AC-74 |

n.d., not determined.

Immunofluorescence

Mice were perfused transcardially with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. Brains and spinal cords were removed, postfixed overnight at 4°C, and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer for 24 hours. Sagittal brain sections and transverse spinal cord sections (30 μm) were cut on a Leica SM2400 microtome (Leica Microsystems, Bucks, UK) and stored at 4°C in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer containing 0.1% sodium azide. For single and double staining, sections were permeabilized and blocked in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer containing 3% bovine serum albumin and 0.1% Triton X-100 (blocking solution). This was followed by an overnight incubation at 4°C with the primary antibodies in blocking solution. After washing, the sections were incubated for 3 hours at room temperature in Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands) or Cy5 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) secondary antibodies in blocking solution. After 4,6-diamindino-2-phenylindole staining, the sections were mounted using Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). In control experiments, filamentous, sarkosyl-insoluble tau was extracted from human P301S tau-transgenic mouse brain and the tau filaments solubilized as described.48,49 The dialyzed material (50 μl) was incubated overnight at 4°C with antibodies directed against cell-cycle proteins or anti-tau antibody AT8 before addition to tissue sections. In additional control experiments, 1 to 10 μg of the p27Kip1 peptide antigen EQTPKKPGLRRQT (corresponding to amino acids 185 to 197 of mouse p27Kip1) was incubated overnight at 4°C with the p27 antibodies (1:100), followed by addition to tissue sections.

Paraffin-embedded sections (10 μm) of formalin-fixed brain tissue from the frontal cortex of a case of FTDP-17 with the P301L tau mutation50 were also used. Sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated. Antigen retrieval was performed by incubating the sections in 10 mmol/L sodium citrate buffer, pH 6, for 15 minutes in a microwave oven. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched using a 90-minute incubation in 20% methanol and 3% hydrogen peroxide. After permeabilization and blocking in Tris-buffered saline-0.2% Tween (TBST), the sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibody in blocking solution. After washing, the sections were incubated for 2 hours at room temperature with the biotinylated secondary antibody in TBST containing 5% goat serum. After washing, the sections were incubated with streptavidin-Alexa 568 (Molecular Probes). The sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C with the second primary antibody in TBST containing 5% goat serum. The signal was revealed using the tyramide signal amplification kit (Molecular Probes). After 4,6-diamindino-2-phenylindole staining, sections were mounted using Vectashield.

Immunoblot Analysis

Brains and spinal cords of 5-month-old human P301S tau-transgenic mice and age-matched controls were homogenized in 3 vol of cold extraction buffer (25 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L EGTA, 5 mmol/L sodium pyrophosphate, 10 mmol/L β-glycerophosphate, 30 mmol/L sodium fluoride, 2 mmol/L sodium vanadate, 1 mmol/L phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride, and 10 μg/ml leupeptin, aprotinin, and pepstatin). The homogenates were spun at 80,000 × g for 15 minutes and the supernatants used for biochemical analysis. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL), and 10 μg of protein were analyzed by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Gels were blotted overnight at 4°C onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Pierce). Membranes were blocked for 30 minutes at room temperature in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 5% milk and 0.1% Tween 20 (blocking buffer) and incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibodies in blocking buffer. The membranes were then washed in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 0.1% Tween 20 and incubated for 45 minutes at room temperature in peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Pierce) in blocking buffer. After washing, the blots were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences, Arlington Heights, IL).

Results

Analysis of Cell-Cycle Protein Expression

The expression and/or activity of proteins involved in cell-cycle regulation was analyzed in 5-month-old P301S tau-transgenic mice and age-matched controls (Table 2). Immunoblot and immunofluorescence studies showed that none of the activators or co-activators of the cell cycle tested were overexpressed or activated in brain and spinal cord of transgenic mice. Indeed, with the exception of antibodies directed against cyclin D1 and phospho-Rb, which stained the nuclei of a few cells in the spinal cord of transgenic mice, none of the proteins analyzed exhibited a different pattern of expression or activity in control and transgenic mice. This was true of cyclins, CDKs and their co-activators, as well as of substrates of CDKs and a number of their inhibitors and co-inhibitors. Similarly, antibodies specific for other markers of mitotic phosphorylation, such as ATM, MPM2, phospho-histone H3, and a nonspecific mitosis epitope, gave a similar staining pattern in control and transgenic mice. In parallel, we used several of the above antibodies [directed against CDK1, Cdc25A, cyclin B, cyclin D, and the retinoblastoma (Rb) protein] on sections of the temporal cortex from two cases of AD. As expected, we observed expression of these cell-cycle markers in many nerve cells with tau inclusions (not shown).

Table 2-6763.

Cell Cycle Markers in Human P301S Tau-Transgenic (Tg) Mice and Age-Matched Controls

| Protein | Effect on cell cycle G0/G1 progression | Cellular location (Immunofluorescence)

|

Expression (Immunoblotting)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | Tg | Controls | Tg | ||

| Cyclin D1 | Cdk4 Activator | + | + | + | + |

| G1/S progression | |||||

| Cyclin E | Early S progression | + | + | + | + |

| Cyclin A | S/G2 transition | + | + | + | + |

| Cdk2 | Activator | + | + | + | + |

| Phospho-Cdk2 (Thr160) | Activator (Active form) | − | − | + | + |

| Cdc25 A | Cdk2 and Cdc2 activator | + | + | + | + |

| G2/M progression | |||||

| Cyclin B | Activator of Cdc2 | + | + | + | + |

| Cdk1 | G2/M transition | + | + | + | + |

| Phospho-Cdk1 (Thr161) | Active form | − | − | − | − |

| Cdc25 C | Cdk1 Activator | + | + | + | + |

| Phospho-Cdc25 C (Thr48) | Cdk1 Activator | + | + | + | + |

| Myt1/Wee1 | Cdc25 Inhibitor | + | + | + | + |

| Polo kinase | Cdc25 Activator | + | + | + | + |

| Cks1 p9 | Cdk Activator | − | − | n.d. | |

| Cdk inhibitor | |||||

| P16 Ink4a | G1/S (Cdk4/6) | − | − | n.d. | |

| P18 Ink4c | G1/S (Cdk4/6) | − | − | n.d. | |

| P19 ARF | G1/S (Cdk4/6) | − | − | n.d. | |

| p21 Cip1 | Cdk inhibitor | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ |

| p27 Kip1 | Cdk inhibitor | + | +++ | + | +++ |

| Other markers | |||||

| ATM | DNA damage | + | + | + | + |

| ORC1 | S progression | − | − | n.d. | |

| Aurora2 | Mitotic activator | − | − | n.d. | |

| MPM2 | Mitotic epitope | − | − | n.d. | |

| Phospho-histone H3 (Ser10) | Mitotic indicator | + | + | n.d. | |

| Mitotic cell antibody | Mitotic indicator | − | − | n.d. | |

| Rb | Transcription factor | + | + | + | + |

| Phospho-Rb (Ser795) | Transcription factor | + | + | + | + |

−, no signal.

+, medium signal.

++/+++, strong signal.

n.d., not determined.

Expression and Cellular Localization of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1

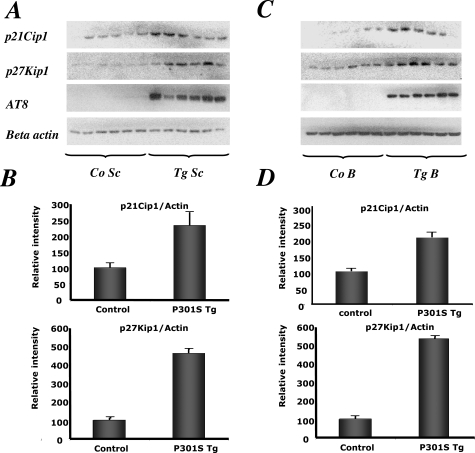

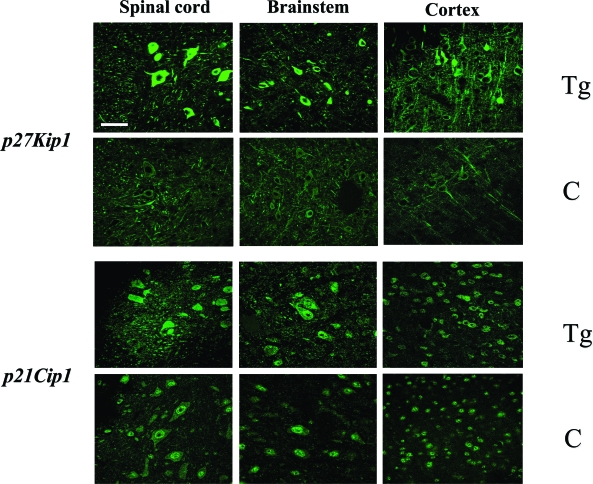

Immunoblotting of brain and spinal cord extracts showed that p21Cip1 was expressed at approximately twofold higher levels and p27Kip1 at fourfold higher levels in 5-month-old human P301S tau-transgenic mice than in controls (Table 2, Figure 1). Immunoblotting with an anti-actin antibody was used to ensure equal loading. Sarkosyl-insoluble tau-rich fractions from the P301S tau-transgenic mice were not immunoreactive for p21Cip1 or p27Kip1 (data not shown). By immunohistochemistry, strongly p27Kip1-immunoreactive nerve cells were seen in transgenic mice, particularly in brainstem and spinal cord (Table 2, Figure 2). The same was also true of the cerebral cortex, with staining present in the cytoplasm. In age-matched controls, by contrast, antibodies directed against p27Kip1 only weakly labeled a few nerve cells and their processes. Identical results were obtained with both p27Kip1 antibodies. Moreover, p27Kip1 staining was completely abolished after preincubation of the primary antibody with the peptide antigen. It was not changed after preincubation of the p27Kip1 antibody with hyperphosphorylated tau protein extracted from the brain of human P301S tau-transgenic mice. Preincubation with the latter completely abolished staining with anti-tau antibody AT100.

Figure 1.

Levels of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 in spinal cord and brain of human P301S tau-transgenic mice and age-matched controls. A: Immunoblotting for p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 of spinal cord (Sc) from six control (Co) and six human P301S tau-transgenic (Tg) mice. Immunoblotting with antibody AT8 was used to document the presence of hyperphosphorylated tau, and anti-β-actin antibody was used to ensure equal loading. B: Quantitative analysis of the immunoblots shown in A. The results were normalized relative to β-actin and are expressed as percentage of controls (taken as 100%) and represent the means ± SEM (n = 6). C: Immunoblotting for p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 of brain (B) from six control (Co) and six human P301S tau-transgenic (Tg) mice. D: Quantitative analysis of the immunoblots shown in C.

Figure 2.

p27Kip1 and p21Cip1 immunofluorescence staining in spinal cord, brainstem, and cerebral cortex of human P301S tau-transgenic (Tg) mice and age-matched controls (C). Nerve cell bodies and processes were strongly immunoreactive for p27Kip1 in spinal cord, brainstem, and cerebral cortex of 5-month-old human P301S tau-transgenic mice. In age-matched control mice, only a small number of weakly p27Kip1-immunoreactive cells was seen. The number of p21Cip1-positive nerve cells was similar in control and transgenic mice. Whereas the staining was predominantly nuclear in control mice, p21Cip1-like immunoreactivity was both nuclear and cytoplasmic in human P301S tau-transgenic mice. Scale bar, 60 μm.

Similar numbers of nerve cells were immunoreactive for p21 Cip1 in brain and spinal cord from control and transgenic mice. However, the staining within nerve cells was different between the two groups. In control mice, p21Cip1-like immunoreactivity was present in the nucleus, with only weak cytoplasmic staining. By contrast, in transgenic mice, p21Cip1 staining was present in both nucleus and cytoplasm. Identical results were obtained with both p21Cip1 antibodies. Staining for p21Cip1 was not changed after preincubation of the p21Cip1 antibody with hyperphosphorylated tau protein extracted from the brain of human P301S tau-transgenic mice.

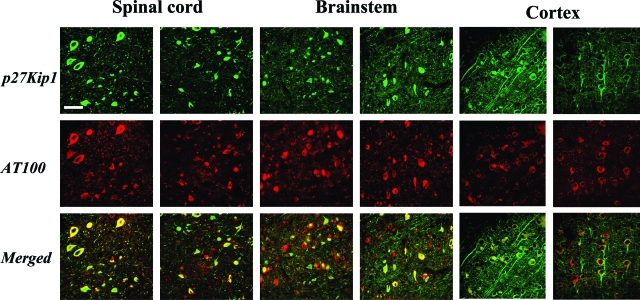

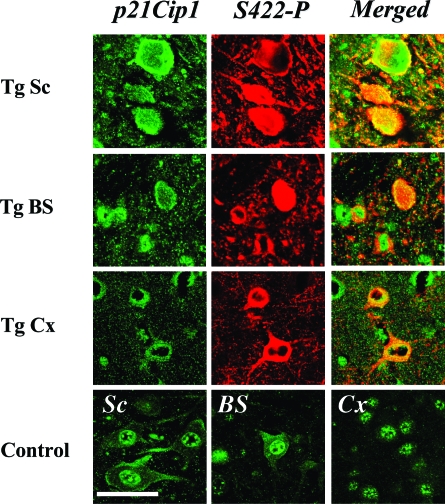

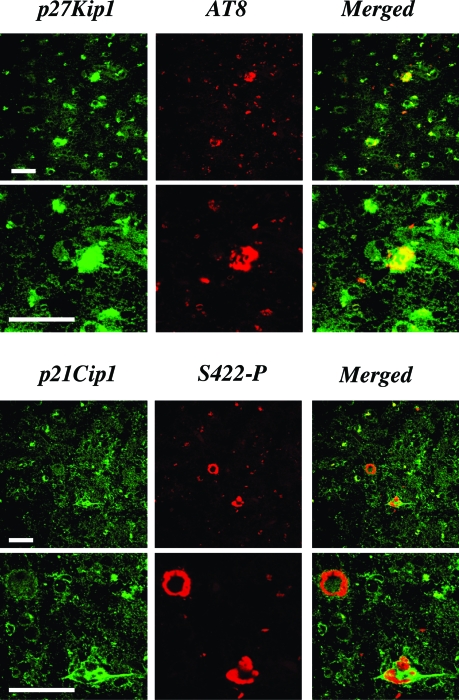

Co-Localization of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 with Tau Protein

Double immunofluorescence was used to investigate the co-localization of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 with tau protein in cerebral cortex, brainstem, and spinal cord of 5-month-old human P301S tau-transgenic mice. As shown in Figure 3, there was extensive co-localization of p27Kip1 staining with staining for anti-tau antibody AT100. In the spinal cord, ∼60% of cells immunoreactive for AT100 were also p27 Kip1-positive. A similar level of co-localization was observed when the different regions of the brainstem (autonomic, motor, tectal, and tegmental) were analyzed. Extensive co-localization of staining for p21Cip1 and phospho-tau S422 was also observed (Figure 4). Strong cytoplasmic staining for p21Cip1 was only observed in cells with an intracytoplasmic accumulation of tau protein. Similar findings were obtained in cerebral cortex and brainstem of transgenic mice. This contrasted with control mice in which p21Cip1 staining was concentrated in the nerve cell nucleus (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Double-labeling immunofluorescence staining for p27Kip1 and tau protein in spinal cord, brainstem, and cerebral cortex of human P301S tau-transgenic mice. Nerve cells in 5-month-old human P301S tau-transgenic mice were strongly immunoreactive for p27Kip1 (green) and tau protein (antibody AT100, red). Merged pictures demonstrated co-localization of p27Kip1 and hyperphosphorylated tau (yellow). Some nerve cells were singly stained for either p27Kip1 or hyperphosphorylated tau. Scale bar, 60 μm.

Figure 4.

Double-labeling immunofluorescence staining for p21Cip1 and tau protein in spinal cord (Sc), brainstem (BS), and cerebral cortex (Cx) of human P301S tau-transgenic (Tg) mice and single-labeling for p21Cip1 in age-matched controls. Nerve cells in 5-month-old human P301S tau-transgenic mice were strongly immunoreactive for p21Cip1 (green) and tau protein (S422-P, red). Merged pictures demonstrated co-localization of p21Cip1 and tau (yellow). In control mice, p21Cip1 staining was concentrated in the nerve cell nucleus, with weaker cytoplasmic staining. In transgenic mice, strong p21Cip1 staining was present in both cytoplasm and nucleus. Scale bar, 60 μm.

Cellular Localization of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 in a Case of FTDP-17 with the P301L Tau Mutation

The P301L tau mutation is known to cause the formation of intraneuronal and intraglial tau deposits.50 We found strongly p27Kip1-immunoreactive cells present in the frontal cortex from a human case of FTDP-17 with the P301L tau mutation. Based on size, the cells probably corresponded to nerve and glial cells. Double immunofluorescence was used to investigate the co-localization of p27Kip1 and tau protein. As shown in Figure 5, there was co-localization of p27Kip1 staining with staining for anti-tau antibody AT8. It is of note that staining for p27Kip1 was stronger in cells that were also AT8-positive than in singly labeled cells. In the frontal cortex of the P301L tau case, a number of nerve cells and glial cells was immunoreactive for p21Cip1. Cells immunoreactive for phospho-tau S422 were also p21Cip1-positive, with strong cytoplasmic staining of both markers (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Double-labeling immunofluorescence staining for p27Kip1 or p21Cip1 and tau protein in frontal cortex from a case of FTDP-17 with the P301L mutation in tau. Nerve cells and glial cells were strongly immunoreactive for p27Kip1 (green) or p21Cip1 (green) and tau protein (antibodies AT8 and S422-P, red). Merged pictures demonstrated co-localization of p27Kip1 or p21Cip1 and hyperphosphorylated tau (yellow). Some cells were only singly stained. Scale bars, 60 μm.

Discussion

We have analyzed the expression and cellular localization of proteins involved in cell-cycle progression in a mouse line transgenic for human P301S tau protein. None of the activators and co-activators of the cell cycle tested were overexpressed in 5-month-old transgenic mice when compared to controls. By contrast, the levels of CDK inhibitors p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 were increased in brain and spinal cord from transgenic mice. Both inhibitors accumulated in the cytoplasm of nerve cells, the majority of which contained inclusions made of hyperphosphorylated tau protein. Staining for p21Cip1 was also present in the nerve cell nucleus. To relate these findings to FTDP-17, we stained sections of frontal cortex from a human case with the P301L mutation in tau (brain tissue from human cases with the P301S mutation was not available to us) for p21Cip1 and p27Kip1. Consistent with the findings in the transgenic mice, strong staining for both proteins was observed in the human FTDP-17 case.

p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 are related proteins that inhibit cell-cycle progression by interacting with cyclin-CDK complexes in the nucleus.51–56 The presence of nuclear p21Cip1 in the human P301S tau-transgenic mice may thus be indicative of inhibition of cyclin-CDK activity. It is in line with our finding that activators and co-activators of the cell cycle were not overexpressed in these mice. Besides the nuclear localization of p21Cip1, both p21Cip1- and p27Kip1-like immunoreactivities were also observed in the cytoplasm of nerve cells with tau inclusions. Recent findings have shown that cytoplasmic Cip/Kip proteins have functions independent of cyclin-CDK inhibition.57,58 Cytoplasmic p21Cip1 has been reported to interact with stress-activated protein kinases and ASK1 kinase and to inhibit their catalytic activities, thus preventing apoptosis.59,60 p21Cip1 has also been shown to inhibit activation of caspase 3 and to resist Fas-mediated cell death.61 In the human P301S tau mice, nerve cell death occurs through a nonapoptotic mechanism,41 suggesting a possible link with the cytoplasmic expression of p21Cip1. Nonapoptotic nerve cell loss has also been described in cases of FTDP-1762 and in nerve cells of mice transgenic for human P301L tau.63,64 In addition to inhibiting apoptosis, cytoplasmic Cip/Kip proteins modulate actin dynamics by direct regulation of the RhoA pathway.65,66 It remains to be seen whether the actin cytoskeleton is abnormal in the human P301S tau-transgenic mice.

The mechanisms underlying increased expression and mislocalization of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 in the human P301S tau-transgenic mice are unknown. A variety of anti-mitotic signals, such as cyclic AMP, rapamycin, transforming growth factor-β and glucocorticoids, have been shown to induce the expression of p21Cip1 and/or p27Kip1 in nonneuronal cells.67–69 Furthermore, in hippocampal granule cells of the rat, chronic stress paradigms have been shown to increase the expression of p27Kip1.70 It is conceivable that the aggregation of human P301S tau in affected nerve cells imposes a chronic stress that results in the overexpression and mislocalization of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1.

Little is known about the expression levels of p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 in human diseases with tau deposits. In AD, one study reported no change in the expression of p21Cip1 and p27Kip17 whereas a second study described a fourfold increase in p27Kip1 by Western blotting and co-localization with hyperphosphorylated tau in the cytoplasm of nerve cells.26 This stands in contrast to the extensive evidence showing re-expression of cell-cycle markers in nerve cells with tau inclusions in AD.7–29 Unlike FTDP-17 and the human P301S tau-transgenic mice, AD is characterized by two types of filamentous deposits made of Aβ and tau. It is therefore conceivable that the re-expression of cell-cycle markers in nerve cells in AD is related to the presence of Aβ deposits.

It has been reported that cell-cycle proteins are required for Aβ-induced nerve cell death in vitro.71 However, the re-expression of mitotic markers has also been described in neurodegenerative diseases that are characterized by the presence of filamentous tau inclusions and the lack of Aβ deposits.20 They include progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, Pick’s disease, Parkinsonism-dementia complex of Guam, and cases of FTDP-17 with the V337M mutation in Tau. It was concluded that human diseases with tau deposits are consistently associated with cell-cycle alterations and that the formation of an active mitotic kinase complex may be a necessary event upstream of tau hyperphosphorylation and filament formation. Furthermore, a recent study using a transgenic mouse model of tauopathy based on the expression of all six human brain tau isoforms in the absence of endogenous mouse tau has shown abnormal expression of a number of cell-cycle markers.72

The present findings show that hyperphosphorylation and filament formation of tau do not require the re-expression of cell-cycle markers in a mouse model of human tauopathy. The same residues are hyperphosphorylated in human diseases with tau deposits and in the human P301S tau-transgenic mice,41 suggesting that common mechanisms are involved. Phosphorylation at most of these sites precedes filament formation in the transgenic mice, consistent with a role upstream of filament formation. The protein kinases and/or protein phosphatases responsible for the hyperphosphorylation of soluble tau in the human P301S tau-transgenic mice are not known. The present findings show that CDKs and their associated cyclins are not involved, despite their abnormal re-expression in AD and other tauopathies. In the human diseases, the expression of cell-cycle markers in tangle-bearing nerve cells may therefore be unrelated to the events that trigger the hyperphosphorylation and filament formation of tau protein.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Ignjatovic and M.G. Spillantini for assistance with immunofluorescence and K. Virdee for helpful comments.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to M. Goedert, Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Hills Road, Cambridge CB2 2QH, UK. E-mail: mg@mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk.

Supported by the Fédération pour la Recherche Médicale (fellowship to P.D.), The European Molecular Biology Organization (fellowship to P.D.), the European Commission (Marie Curie fellowship QLK6-1999-51519 to M.H.), the UK Medical Research Council, and United States Public Health Service grant P30AG10133.

Present address of M.H.: Paul Flechsig Institute of Brain Research, University of Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany.

References

- Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Davies SW. Filamentous nerve cell inclusions in neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1998;8:619–632. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buée L, Bussière T, Buée-Scherrer V, Delacourte A, Hof PR. Tau protein isoforms, phosphorylation and role in neurodegenerative disorders. Brain Res Rev. 2000;33:95–130. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(00)00019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee VMY, Goedert M, Trojanowski JQ. Neurodegenerative tauopathies. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:1121–1159. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poorkaj P, Bird TD, Wijsman E, Garruto RM, Anderson L, Andreadis A, Wiederholt WC, Raskind M, Schellenberg GD. Tau is a candidate gene for chromosome 17 frontotemporal dementia. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:815–825. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton M, Lendon CL, Rizzu P, Baker M, Froelich S, Houlden H, Pickering-Brown S, Chakraverty S, Isaacs A, Grover A, Hackett J, Adamson J, Lincoln S, Dickson D, Davies P, Petersen RC, Stevens M, de Graaff E, Wauters E, van Baren J, Hillebrand M, Joosse M, Kwon JM, Nowotny P, Che LK, Norton J, Morris JC, Reed LA, Trojanowski JQ, Basun H, Lannfelt L, Neystat M, Fahn S, Dark F, Tannenberg T, Dodd PR, Hayward N, Kwok JBJ, Schofield PR, Andreadis A, Snowden J, Craufurd D, Neary D, Owen F, Oostra BA, Hardy J, Goate A, van Swieten J, Mann D, Lynch T, Heutink P. Association of missense and 5′-splice-site-mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature. 1998;393:702–705. doi: 10.1038/31508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini MG, Murrell JR, Goedert M, Farlow MR, Klug A, Ghetti B. Mutation in the tau gene in familial multiple system tauopathy with presenile dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7737–7741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arendt T, Rödel L, Gärtner U, Holzer M. Expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16 in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroreport. 1996;7:3047–3049. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199611250-00050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McShea A, Harris PL, Webster KR, Wahl AF, Smith MA. Abnormal expression of the cell cycle regulators P16 and CDK4 in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:1933–1939. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busser J, Geldmacher DS, Herrup K. Ectopic cell cycle proteins predict the sites of neuronal cell death in Alzheimer’s disease brain. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2801–2807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-08-02801.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arendt T, Holzer M, Gärtner U. Neuronal expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors of the INK4 family in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm. 1998;105:949–960. doi: 10.1007/s007020050104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujioka Y, Takahashi M, Tsuboi Y, Yamamoto T, Yamada T. Localization and expression of cdc2 and cdk4 in Alzheimer brain tissue. Dement Geriat Cogn Disord. 1999;10:192–198. doi: 10.1159/000017119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan-Sciutto KL, Malaiyandi LM, Bowser R. Altered distribution of cell cycle transcriptional regulators during Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61:358–367. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.4.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoozemans JJ, Bruckner MK, Rozemuller AJ, Verhuis R, Eikelenboom P, Arendt T. Cyclin D1 and cyclin E are co-localized with cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) in pyramidal neurons in Alzheimer disease temporal cortex. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61:678–688. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.8.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy Z, Esiri MM, Cato AM, Smith AD. Cell cycle markers in the hippocampus in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 1997;94:6–15. doi: 10.1007/s004010050665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding XL, Husseman J, Tomashevski A, Nochlin D, Jin LW, Vincent I. The cell cycle Cdc25A tyrosine phosphatase is activated in degenerating postmitotic neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:1983–1990. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64837-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent I, Rosado M, Davies P. Mitotic mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease? J Cell Biol. 1996;132:413–425. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.3.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondratick CM, Vandre DD. Alzheimer’s disease neurofibrillary tangles contain mitosis-specific phosphoepitopes. J Neurochem. 1996;67:2405–2416. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67062405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy Z, Esiri MM, Smith AD. Expression of cell cycle markers in the hippocampus in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative conditions. Acta Neuropathol. 1997;93:294–300. doi: 10.1007/s004010050617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent I, Jicha G, Rosado M, Dickson DW. Aberrant expression of mitotic cdc2/cyclin B1 kinase in degenerating neurons of Alzheimer’s disease brain. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3588–3598. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03588.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husseman JW, Hallows JL, Bregman DB, Leverenz JB, Nochlin D, Jin LW, Vincent I. Mitotic activation: a convergent mechanism for a cohort of neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:815–828. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PL, Zhu X, Pamies C, Rottkamp CA, Ghanbari HA, McShea A, Feng Y, Ferris DK, Smith MA. Neuronal polo-like kinase in Alzheimer disease indicates cell cycle changes. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:837–841. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00218-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomashevski A, Husseman J, Jin LW, Nochlin D, Vincent I. Constitutive Wee1 activity in adult brain neurons with M phase-type alterations in Alzheimer neurodegeneration. J Alzheimers Dis. 2001;3:195–207. doi: 10.3233/jad-2001-3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent I, Bu B, Hudson K, Husseman J, Nochlin D, Jin L. Constitutive Cdc25B tyrosine phosphatase activity in adult brain neurons with M phase-type alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 2001;105:639–650. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00219-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husseman JW, Hallows JL, Bregman DB, Leverenz JB, Nochlin D, Jin LW, Vincent I. Hyperphosphorylation of RNA polymerase II and reduced neuronal RNA levels precede neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2001;60:1219–1232. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.12.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa O, Zhu X, Lee HG, Raina A, Obrenovich ME, Bowser R, Ghanbari HA, Castellani RJ, Perry G, Smith MA. Ectopic localization of phosphorylated histone H3 in Alzheimer’s disease: a mitotic catastrophe? Acta Neuropathol. 2003;105:524–528. doi: 10.1007/s00401-003-0684-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa O, Lee HG, Zhu X, Raina A, Harris PL, Castellani RJ, Perry G, Smith MA. Increased p27, an essential component of cell cycle control, in Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Cell. 2003;2:105–110. doi: 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2003.00042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, McShea A, Harris PL, Raina AK, Castellani RJ, Funk JO, Shah S, Atwood C, Bowen R, Bowser R, Morelli L, Perry G, Smith MA. Elevated expression of a regulator of the G2/M phase of the cell cycle, neuronal CIP-1-associated regulator of cyclin B, in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci Res. 2004;75:698–703. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent I, Zheng JH, Dickson DW, Kress Y, Davies P. Mitotic phosphoepitopes precede paired helical filaments in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 1998;19:287–296. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(98)00071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Mufson EJ, Herrup K. Neuronal cell death is preceded by cell cycle events at all stages of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2557–2563. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02557.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope WB, Lambert MP, Leypold B, Seupaul R, Sletten L, Krafft G, Klein WL. Microtubule-associated protein tau is hyperphosphorylated during mitosis in the human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y. Exp Neurol. 1994;126:185–194. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuss U, Döring F, Illenberger S, Mandelkow EM. Cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation and microtubule binding of tau protein stably transfected into Chinese hamster ovary cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:1397–1410. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.10.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illenberger S, Zheng-Fischhöfer Q, Preuss U, Stamer K, Baumann K, Trinczek B, Biernat J, Godemann R, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E. The endogenous and cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation of tau protein in living cells: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:1495–1512. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.6.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delobel P, Flament S, Hamdane M, Mailliot C, Sambo AV, Begard S, Sergeant N, Delacourte A, Vilain JP, Buée L. Abnormal tau phosphorylation of the Alzheimer-type also occurs during mitosis. J Neurochem. 2002;83:412–420. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledesma MD, Correas I, Avila J, Diaz-Nido J. Implication of brain cdc2 and MAP2 kinases in the phosphorylation of tau protein in Alzheimer’s disease. FEBS Lett. 1992;308:218–224. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)81278-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ubaidi MR, Hollyfield JG, Overbeek PA, Baehr W. Photoreceptor degeneration induced by the expression of simian virus 40 large tumor antigen in the retina of transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1194–1198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feddersen RM, Ehlenfeldt R, Yunis WS, Clark HB, Orr HT. Disrupted cerebellar cortical development and progressive degeneration of Purkinje cells in SV40 antigen transgenic mice. Neuron. 1992;9:955–966. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90247-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J, McGowan E, Rockwood J, Melrose H, Nacharaju P, van Slegtenhorst M, Gwinn-Hardy K, Murphy MP, Baker M, Yu X, Duff K, Hardy J, Corral A, Lin WL, Yen SH, Dickson DW, Davies P, Hutton M. Neurofibrillary tangles, amyotrophy and progressive motor disturbance in mice expressing mutant (P301L) tau protein. Nat Genet. 2000;25:402–405. doi: 10.1038/78078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Götz J, Chen F, Barmettler R, Nitsch RM. Tau filament formation in transgenic mice expressing P301L tau. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:529–534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006531200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim F, Hernandez F, Lucas JJ, Gomez-Ramos P, Moran MA, Avila J. FTDP-17 mutations in tau transgenic mice provoke lysosomal abnormalities and tau filaments in forebrain. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2001;18:702–714. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2001.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanemura K, Murayama M, Akagi T, Hashikawa T, Tominaga T, Ichikawa M, Yamaguchi H, Takashima A. Neurodegeneration with tau accumulation in a transgenic mouse expressing V337M human tau. J Neurosci. 2002;22:133–141. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00133.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen B, Ingram E, Takao M, Smith MJ, Jakes R, Virdee K, Yoshida H, Holzer M, Craxton M, Emson PC, Atzori C, Migheli A, Crowther RA, Ghetti B, Spillantini MG, Goedert M. Abundant tau filaments and nonapoptotic neurodegeneration in transgenic mice expressing human P301S tau protein. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9340–9351. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09340.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatabayashi Y, Miyasaka T, Chui DH, Akagi T, Mishima KI, Iwasaki K, Fujiwara M, Tanemura K, Murayama M, Ishiguro K, Planel E, Sato S, Hashikawa T, Takashima A. Tau filament formation and associative memory deficit in aged mice expressing mutant (R406W) human tau. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13896–13901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202205599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddo S, Caccarno A, Shepherd JD, Murphy MP, Golde TE, Kayed R, Metherate R, Mattson MP, Akbari Y, LaFerla FM. Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Aβ and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron. 2003;39:409–421. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda M, Shoji M, Kawarai T, Kawarabayashi T, Matsubara E, Murakami T, Sasaki A, Tomidokoro Y, Ikarashi Y, Kuribara H, Ishiguro K, Hasegawa M, Yen SH, Chishti MA, Harigaya Y, Abe K, Okamoto K, St George-Hyslop P, Westaway D. Accumulation of filamentous tau in the cerebral cortex of human tau R406W transgenic mice. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:521–531. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62274-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M, Jakes R, Vanmechelen E. Monoclonal antibody AT8 recognises tau protein phosphorylated at serine 202 and threonine 305. Neurosci Lett. 1995;189:167–169. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11484-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng-Fischhöfer Q, Biernat J, Mandelkow EM, Illenberger S, Godemann R, Mandelkow E. Sequential phosphorylation of Tau by glycogen synthase kinase-3β and protein kinase A at Thr212 and Ser214 generates the Alzheimer-specific epitope of antibody AT100 and requires a paired helical filament-like conformation. Eur J Biochem. 1998;252:542–552. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2520542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Jakes R, Rutherford D, Crowther RA. Multiple isoforms of human microtubule-associated protein tau: sequences and localization in neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 1989;3:519–526. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90210-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Cairns NJ, Crowther RA. Tau proteins of Alzheimer paired helical filaments: abnormal phosphorylation of all six brain isoforms. Neuron. 1992;8:159–168. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90117-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellucci A, Westwood AJ, Ingram E, Casamenti F, Goedert M, Spillantini MG. Induction of inflammatory mediators and microglial activation in mice transgenic for mutant human P301S tau protein. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1643–1652. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63421-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirra SS, Murrell JR, Gearing M, Spillantini MG, Goedert M, Crowther RA, Levey AI, Jones R, Green J, Shoffner JM, Wainer BH, Schmidt ML, Trojanowski JQ, Ghetti B. Tau pathology in a family with dementia and a P301L mutation in tau. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58:335–345. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199904000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper JW, Adami GR, Wei N, Keyomarski K, Elledge SJ. The p21 Cdk-interacting protein Cip1 is a potent inhibitor of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Cell. 1993;75:805–816. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90499-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Deiry WS, Tokino T, Velculescu VE, Levy DB, Parsons R, Trent JM, Lin D, Mercer E, Kinzler DW, Volgelstein B. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell. 1993;75:817–825. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90500-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y, Hannon GJ, Zhang H, Casso D, Kobayashi R, Beach D. p21 is a universal inhibitor of cyclin kinases. Nature. 1993;366:701–704. doi: 10.1038/366701a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Turck CW, Morgan DO. Inhibition of CDK2 activity in vivo by an associated 20K regulatory subunit. Nature. 1993;366:707–710. doi: 10.1038/366707a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyak K, Lee MH, Erdjument-Bromage H, Koff A, Roberts JM, Tempst P, Massagué J. Cloning of p27Kip1, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor and a potential mediator of extracellular antimitogenic signals. Cell. 1994;78:59–66. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90572-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoshima H, Hunter T. p27, a novel inhibitor of G1 cyclin-Cdk protein kinase activity, is related to p21. Cell. 1994;78:67–74. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90573-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coqueret O. New roles for p21 and p27 cell-cycle inhibitors: a function for each cell compartment? Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:65–70. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)00043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denicourt C, Dowdy SF. Cip/Kip proteins: more than just CDKs inhibitors. Genes Dev. 2004;18:851–855. doi: 10.1101/gad.1205304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asada M, Yamada T, Ichijo H, Delia D, Miyazono K, Fukumoro K, Mizutani S. Apoptosis inhibitory activity of cytoplasmic p21Cip1/WAF1 in monocytic differentiation. EMBO J. 1999;18:1223–1234. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim J, Lee H, Park J, Kim H, Choi EJ. A non-enzymatic p21 protein inhibitor of stress-activated protein kinases. Nature. 1996;381:804–806. doi: 10.1038/381804a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A, Tsutomi Y, Akahane K, Araki T, Miura M. Resistance to Fas-mediated apoptosis: activation of caspase 3 is regulated by cell cycle regulator p21WAF1 and IAP gene family ILP. Oncogene. 1998;17:931–939. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atzori C, Ghetti B, Piva R, Srinivasan AN, Zolo P, Delisle MB, Mirra SS, Migheli A. Activation of the JNK/p38 pathway occurs in diseases characterized by tau protein pathology and is related to tau phosphorylation but not to apoptosis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2001;60:1190–1197. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.12.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehr C, Lewis J, McGowan E, Crook J, Lin WL, Godwin K, Knight J, Dickson DW, Hutton M. Apoptosis in oligodendrocytes is associated with axonal degeneration in P301L tau mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;15:553–562. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liazoghli D, Perrault S, Micheva KD, Desjardins M, Leclerc N. Fragmentation of the Golgi apparatus induced by the overexpression of wild-type and mutant human tau forms in neurons. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1499–1514. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62366-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagahara H, Vocero-Akbani AM, Snuder EL, Ho A, Latham DG, Lissy NA, Becker-Hapak M, Ezhevsky SA, Dowdy SF. Transduction of full-length TAT fusion proteins into mammalian cells: TAT-p27Kip1 induces cell migration. Nat Med. 1998;4:1449–1452. doi: 10.1038/4042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besson A, Gurian-West M, Schmidt A, Hall A, Roberts JM. p27Kip1 modulates cell migration through the regulation of RhoA activation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:862–876. doi: 10.1101/gad.1185504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato JY, Matsuoka M, Polyak K, Massagué J, Sherr CJ. Cyclic AMP-induced G1 phase arrest mediated by an inhibitor (p27Kip1) of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 activation. Cell. 1994;79:487–496. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90257-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nourse J, Firpo E, Flanagan WM, Coats S, Polyak K, Lee MH, Massagué J, Crabtree GR, Roberts JM. Interleukin 2-mediated elimination of the p27Kip1 cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor prevented by rapamycin. Nature. 1994;372:570–573. doi: 10.1038/372570a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slingerland JM, Hengst L, Pan CH, Alexander D, Stampfer MR, Reed SI. A novel inhibitor of cyclin-Cdk activity detected in transforming growth factor beta-arrested epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3683–3694. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.3683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine VM, Maslam S, Joëls M, Lucassen PJ. Increased p27Kip1 protein expression in the dentate gyrus of chronically stressed rats indicates G1 arrest involvement. Neuroscience. 2004;129:593–601. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovanni A, Wirtz-Brugger F, Keramaria E, Slack R, Park DS. Involvement of cell cycle elements, cyclin-dependent kinases, pRb, and E2F-DP, in B-amyloid-induced neuronal death. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19011–19016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andorfer C, Acker CM, Kress Y, Hof PR, Duff K, Davies P. Cell-cycle reentry and cell death in transgenic mice expressing nonmutant human tau isoforms. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5446–5454. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4637-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]