Abstract

Mutation in the serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase 3 (Sgk3, also known as Sgkl or Cisk) gene causes both defective hair follicle development and altered hair cycle in mice. We examined Sgk3-mutant YPC mice (YPC-Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc) and found expression of SGK3 protein with altered function. In the hair follicles of YPC mice, the aberrant differentiation and poor proliferation of hair matrix keratinocytes during the period of postnatal hair follicle development resulted in a complete lack of hair medulla and weak hair. Surprisingly, the length of postnatal hair follicle development and anagen term was shown to be dramatically shortened. Also, phosphorylation of GSK3β at Ser9 and the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin were reduced in the developing YPC hair follicle, suggesting that phosphorylation of GSK3β and WNT-β-catenin pathway takes part in the SGK3-dependent regulation of hair follicle development. Moreover, the above-mentioned features, especially the hair-cycling pattern, differ from those in other Sgk3-null mutant strains, suggesting that the various patterns of dysfunction in the SGK3 protein may result in phenotypic variation. Our results indicate that SGK3 is a very important and characteristic molecule that plays a critical role in both hair follicle morphogenesis and hair cycling.

The mammalian hair follicle first develops from embryonic ectodermal hair germ by reciprocal epithelial-mesenchymal interaction1 and thereafter maintains its growth and differentiation during the prenatal and postnatal periods. Finally, like other organs developed from an epithelial-mesenchymal interaction (such as the teeth), hair follicles form a very complex structure, which consists of mesenchyme-derived dermal papilla and three distinct epithelial layers: the outer root sheath (ORS), the outer layer; the hair shaft, the central layer, which is subdivided into three layers (cuticle, cortex, and medulla); the inner root sheath (IRS)—the middle layer, which is subdivided into three layers (Henle’s, Huxley’s, and cuticle of IRS).2,3 The hair follicle is, however, completely different from other organs with its characteristic feature of cyclic self-renewing ability. Namely, the hair follicle has a cyclic growth and retardation pattern called the hair cycle. Once fully maturated (full anagen), the hair follicle begins to regress (catagen), maintains quiescence (telogen), grows again (anagen) and repeats such a cycle.2,4,5

Recently, we have found that the serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase 3 (Sgk3) mutant YPC mouse (YPC-Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc) shows defective postnatal hair follicle development,6,7 and McCormick and colleagues8 and Alonso and colleagues9 also reported that a targeted disruption of Sgk3 in mice impairs hair follicle de-velopment (Sgk3tm1Dpea/Sgk3tm1Dpea and Sgk3tm1Efu/Sgk3tm1Efu, respectively). Therefore, SGK3 is thought to be closely related to hair follicle development and homeostasis, but the exact function of SGK3 in the hair follicle is still unclear. SGK3, also known as serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase-like (SGKL) or cytokine-independent survival kinase (CISK), is a member of the AGC kinase family, which includes AKT1 and serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase (SGK), which are both involved in various intracellular processes, including membrane trafficking, cell survival, and apoptosis.10–13 Similar to AKT1, SGK3 is considered to be a substrate for the 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDPK1) downstream of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), which is activated by growth factors, such as EGF or IGF1,11,14–18 and it is suggested that SGK3 shares some of its substrates with AKT1. In fact, some AKT1-related molecules, such as glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) or forkhead box O3a (FOXO3A), were shown to be substrates for SGK3.11,19

The cellular and molecular mechanisms that regulate hair follicle differentiation and hair cycling are poorly understood. During the process of hair follicle differentiation, hair matrix transient amplifying cells derived from the bulge epithelial stem cells divide, move upward, and differentiate into IRS or hair shaft, at least partially because of the paracrine signals from the adjacent dermal papilla.20–22 Recently, several pathways or molecules, such as the canonical WNT pathway,23–27 bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) pathway,28–35 sonic hedgehog (SHH),36–39 homeobox, msh-like 2 (MSX2),40 or zinc finger transcription factor GATA341 were shown to be closely related to the hair germ induction or postnatal hair follicle development. In contrast, there are few reports about the mechanism of hair cycling. FGF5,42,43 junction plakoglobin (JUP),44 and MSX240 are said to be closely related to the cycling mechanism, but the details are still unclear.

In the present study, we have examined the detailed morphological and molecular characteristics of the hair follicles of Sgk3 mutant YPC mice (YPC-Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc). We have shown that SGK3 is a very unique protein kinase that plays critical roles in both hair follicle morphogenesis and hair cycling. In addition, the difference of the gross phenotype and hair-cycling pattern between YPC and Sgk3-null mutants (Sgk3tm1Dpea/Sgk3tm1Dpea and Sgk3tm1Efu/Sgk3tm1Efu)8,9 in relation with the difference of Sgk3 alleles in each strain will provide important insight into the molecular control mechanism of hair cycling.

Materials and Methods

Animals

In the present study, we used mice of the male and female YPC (YPC-Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc) and C57BL/6J:Jcl strains (C57BL/6J), and Jcl:ICR colony (ICR) maintained at the University of Tokyo. The YPC mice were provided by the National Institute for Infectious Diseases, and ICR and C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Japan CLEA (Tokyo, Japan). The YPC mouse is a mutant mouse strain established from a Swiss Albino mouse colony at the National Institute of Health, Japan.6,7 ICR mice, which were also originated from a Swiss Albino mouse colony, were used as the wild-type (WT) control throughout the experiment, except in Figure 1, B–G. To clarify the effect of the background on the phenotype, we made F1 littermates between YPC and C57BL/6J (B6), and then it was crossed to B6 and N2 littermates (Sgk3+/ypc) were obtained. The crossing to B6 was repeated until it reached N6, and homozygous mutant littermates (B6.YPC-Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc) were obtained by crossing N6 male and female. Genotyping was done by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) method with primer set (5′-TGAAAGGAAGGTAAGGTGAA-3′ and 5′-GCCCTATTTCTTGCATACAG-3′) and MseI. Animals were fed and bred in an isolator system under conventional conditions. All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, The University of Tokyo.

Figure 1-6804.

Severe hair coat and hair structural defect in YPC mice (Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc). A: Gross appearance of ICR and YPC mice at the age of P70. The YPC mouse looks almost bald, but short, weak, and curved hairs appear on the skin. B and C: Development of WT (+/+, left) and mutant (Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc, right) of the same littermates obtained from the F1 male and female between ICR and YPC. At P7 (B), the mutant littermates show a thin hair coat compared with the WT, and it is more prominent at P9 (C). D–G: Gross appearance of the WT (+/+, left) and mutant (Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc, right) of the same littermates of C57BL/6J background. At P5 (D), the WT and mutant look the same, but the black coloring is less in the mutant than the WT. At P7 (E), the mutant shows a bald-like appearance (however, very short hairs appeared), whereas the WT bore short hairs at that age. The mutant shows the poor-coated phenotype while the WT littermate grew as normal B6 mouse at P21 (F) and P84 (G). H and I: Hairs plucked from +/+ (H) and Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc (I) mice on B6 background at P84, which were shown in G. Note that each type of hairs in Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc is curly and shorter and thinner than that in WT. Distinction of awl and zigzag hair in Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc was done based on the length of each hair. Scale bar, 1 mm.

Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

RT-PCR to evaluate the expression of the Sgk3 mRNA was performed with the following conditions using RNA samples obtained from whole dorsal skin of postnatal day 0 (P0) to P28 ICR mice. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 10 μg of RNA, using oligo d(T) primer and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and used for PCR amplification with primer pairs for the Sgk3 gene: 5′-GCCGAGATGTTGCTGAAATG-3′ and 5′-GGTTTCTGAATGTCAAAGTG-3′; or the Gapdh gene: 5′-CTG-CTTCACCACCTTCTTGA-3′, 5′-TCACCATCTTCCAGGA-GCG-3′. PCR was performed using rTaq polymerase (TAKARA BIO, Ohtsu, Japan) for 25 cycles, consisting of 94°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 60 seconds in 10-μl reaction mixtures containing 1.5 mmol/L Mg2+. Concentrations of cDNA templates were normalized among the samples according to the expression of Gapdh. After amplification, samples were electrophoresed through 1.5% agarose gel in the presence of ethidium bromide and visualized under ultraviolet light.

Protein Extraction and Western Blot Analysis

The WT and YPC dorsal skin section was homogenized using in an extraction buffer containing 20 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mmol/L NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 1 mmol/L Na3VO4, 10 mmol/L NaF, and proteinase inhibitors, and then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes and the supernatant was collected as extracted protein. Twenty μg of protein were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane was blocked with Tris-buffered saline containing 2 to 5% nonfat dry milk and 0.1% Tween 20 and then incubated with the following primary antibodies at the indicated concentrations: SGK3 (N-term, rabbit polyclonal, 1:500; Abgent, San Diego, CA); phospho-GSK3β (Ser9, rabbit polyclonal, 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA); GSK3β (rabbit polyclonal, 1:1000; Cell Signaling); β-actin (gene symbol name: Actb) (mouse monoclonal, 1:2000; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). Primary antibodies were probed with horseradish peroxidase-secondary antibodies and the signals were detected with enhanced chemiluminescence plus (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) and ChemDoc XRS-J (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The membranes reacted with anti-SGK3 or anti-phospho-GSK3β (Ser9) antibodies were stripped and then reprobed with anti-β-actin or anti-GSK3β and anti-β-actin antibodies, respectively.

Histology and Morphometry

Mid-dorsal skin samples from the head to the root of the tail from the WT and mutant mice at various time intervals throughout P28 were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, dehydrated through an alcohol gradient, and embedded in paraffin. Longitudinal sections of hair follicles, 4 μm thick, were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). All morphological observations, except these described below, were performed on the hair follicles at the level of the thoracolumbar junction. The hair-cycling pattern was determined in accordance with the method described previously.44 In brief, histological sections were recorded with an interacting charge-coupled device camera (FUJIX HC-300Z; FUJIFILM, Tokyo, Japan), and the scanned photographs were stored on a computer for quantification of the length of each hair follicle by NIH image 1.61. More than 25 hair follicles at the thoracolumbar junction from three to five pairs of normal and mutant mice were scanned. In addition, all hair follicles in the whole long dorsal skin from three to five pairs of YPC mice from P5 to P14 were categorized as anagen, catagen, or telogen, the numbers were counted, and the percentage of each hair cycle stage was estimated. Cells positive for the phospho-histone H3 antibody in ORS or bulb keratinocytes of more than 30 hair follicles from at least three mice at each age of WT and YPC mice were counted. Statistical analysis was performed with Student’s t-test using Statcel software (OMS Publishing, Tokyo, Japan).

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Small pieces of the collected skin were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 mol/L PB (pH 7.4), postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in the same buffer, and embedded in Epok 812 (Oken Co., Tokyo, Japan). Ultrathin sections were double-stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and observed under a JEM-1200 EX electron microscope (Jeol Co., Tokyo, Japan).

In Situ Hybridization

For in situ hybridization, 4% paraformaldehyde-fixed mid-dorsal skin paraffin sections (8 μm thick) from ICR mice were acetylated, treated with 0.2 mol/L HCl, digested with 10 μg/ml proteinase K for 20 minutes, and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. After prehybridization, sections were hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled sense or anti-sense Sgk3 riboprobes containing a 618-bp fragment of the mouse Sgk3 mRNA (nucleotides 311 to 928, NM_133220) at 57°C overnight, and then the sections were washed in 50% formamide/standard saline citrate, digested with 20 μg/ml RNase A, and rewashed in standard saline citrate. After blocking, the sections were incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-digoxigenin antibody (1:500; Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) at 4°C overnight. Positive signals were visualized with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoyl phosphate and nitro blue tetrazolium.

Immunohistochemistry, Immunofluorescence, and Terminal dUTP Nick-End Labeling (TUNEL) Staining

Five-μm cryosections postfixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (for AE13, AE15, and GATA-3) or 4-μm paraffin sections (for others) were immunostained. For staining with mouse mAbs, we used the reagents and protocol from the MOM basic kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The following primary antibodies were used at the indicated concentrations: SGK3 (the same as that used in Western blot, 1:50), phospho-GSK3β (Ser9, the same as that used in Western blot, 1:50), AE13 (mouse, 1:100)45 ; AE15 (mouse, 1:100)46 ; phospho-histone H3 (rabbit, 1:50; Cell Signaling); GATA3 (mouse, 1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); β-catenin (gene symbol name: Ctnnb1) (mouse, 1:100; BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA); phospho-SMAD1/5/8 (rabbit, 1:100; Cell Signaling). Primary antibodies were detected with biotinylated secondary antibodies plus peroxidase- or fluorescein isothiocyanate-streptavidin complex. Phospho-SMAD1/5/8-positive cells were detected using TSA biotin system (PerkinElmer, Boston, MA). Counterstaining was performed with methylgreen or propidium iodide. TUNEL staining, which was first proposed by Gavrieli and colleagues,47 was performed using an apoptosis detection kit (Apop Tag; Intergen, Purchase, NY) on 4-μm paraffin sections.

Results

Gross Morphology and Hair Analysis of YPC Mouse

Sgk3 mutant YPC mice (YPC-Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc) showed very severe defects in hair coat, which was characterized by extremely short, weak, and curved hairs (Figure 1A). To observe when the difference in the gross morphology begins to appear, we compared the early age of +/+ and Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc individuals of the same littermates from F1 heterozygous (Sgk3+/ypc) male and females, which were born between YPC and ICR. At P7, mutant littermates showed a thin hair coat compared with WT (Figure 1B), and it became more prominent at P9 (Figure 1C). We backcrossed YPC to C57BL/6J mice and WT (B6.YPC-+/+) and the homozygous mutant (B6.YPC-Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc) were obtained from N6 heterozygous males and females, as written in the Materials and Methods, and the gross morphology was observed (Figure 1, D–G). At P5, the differences between WT and mutant littermates were little, but the black coloring due to the accumulation of melanocytes seemed to be less in the mutants, especially around the head (Figure 1D). At P7, as well as that shown in Figure 1B, mutant littermates still showed a bald-like appearance (however, very short hairs appeared), while WT mice already had short hairs at that age (Figure 1F). The WT littermate grew as a normal B6 mouse; however, the mutants showed the poor-coated phenotype, even as they grew older, but the hair length in B6 background mutants seemed to be slightly longer than that in YPC (Figure 1, A, F, and G). We examined the hairs plucked from the +/+ and Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc of B6 background at P84 (Figure 1, H and I). Each type of hair in Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc was shown to be curly and much shorter and thinner than those in the WT. We strongly mention that the gross phenotype of Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc on B6 background is different from those of the strains that carries artificially disrupted Sgk3 (Sgk3tm1Dpea/Sgk3tm1Dpea, Sgk3tm1Efu/Sgk3tm1Efu),8,9 especially at the hair length.

Sgk3 mRNA Is Expressed in the IRS of the Developing Hair Follicle

We examined the expression of the Sgk3 mRNA in different stages of the hair cycle with RT-PCR using RNA samples obtained from the whole dorsal skin of P0 to P28 ICR mice. RT-PCR revealed that Sgk3 expression was low at P0, increased gradually to P14, and then decreased thereafter (Figure 2A). As mentioned in our previous report,7 in situ Sgk3 mRNA expression in the WT hair follicle was not detected at P0 (data not shown) but was first detected at P3 restrictedly in the IRS (Figure 2B, early morphogenesis). Sgk3 mRNA expression remained observable in IRS during morphogenesis (P5, P7, P11; data not shown) until P14 (Figure 2C, late morphogenesis). In the early stage of catagen, Sgk3 mRNA was still expressed in the remaining IRS (at P18, Figure 2D), but this expression then gradually disappeared thereafter, along with the involution of IRS through catagen progression (data not shown).

Figure 2-6804.

Expression of Sgk3 mRNA in the ICR mouse hair follicle. A: The expression of the Sgk3 mRNA in different stages of the hair cycle with RT-PCR using RNA samples obtained from whole dorsal skin of P0 to P28 ICR mice. B–D: A digoxigenin-labeled Sgk3 cRNA probe was hybridized with the skin section of ICR mice at various ages. At the early stage of postnatal hair follicle morphogenesis, Sgk3 mRNA was restrictedly expressed in IRS (B, P3), and at late morphogenesis, the IRS-specific expression of Sgk3 mRNA is still observed (C, P14). At early catagen, Sgk3 mRNA is still expressed in the remaining IRS (D, P18), but the expression disappears thereafter, along with the involution of IRS through catagen progression. Scale bar, 60 μm.

SGK3 Protein Is Expressed in the Developing Hair Follicle of Both Wild-Type and Sgk3 Mutant YPC Mice

The expression of the SGK3 protein was compared between ICR (wild-type, WT) and YPC (YPC-Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc) mice. Western blot and immunohistochemistry were performed on the protein samples and paraffin sections, respectively, obtained from the dorsal skin of WT and YPC mice at P0, P3, and P5. We used anti-human SGK3 antibody (N-term, ABGENT), which is generated from rabbits immunized with synthetic peptide of amino acid 13 to 30 of human SGK3, where the amino acid sequence is completely conserved between humans and the mouse, for the detection of mouse SGK3. Western blot analysis revealed that SGK3 is expressed in the skin of YPC as well as WT (Figure 3A). No extra bands were observed. Theoretically, the SGK3 protein in YPC lacks the 36 amino acid residue of the C-term and is considered to be a bit smaller than that in the WT7 ; however, no size difference was detected between WT and YPC, even when separated in 6 to 8% polyacrylamide gel. From the results of immunohistochemistry, at P0, strong expression was observed in the hair bulb, ORS, including the bulge, IRS, and cuticle/cortex keratinocytes both in the WT and mutant (Figure 3, B and C). At P3, almost same area as P0 showed positive signals; however, in YPC the expression in bulb keratinocytes was considerably lower compared to that in the WT (Figure 3, D and E). At P5, in the WT, positive signals were still observed in the bulb, ORS, IRS, cuticle/cortex, and sebaceous gland keratinocytes, but not in the medulla. In YPC, the expression was observed in almost the same areas without bulb, where a lower expression than WT was observed (Figure 3, F and G). A considerably low expression was observed in the epidermal keratinocytes and the dermal papilla in both strains from P0 to P5. From the above results, SGK3 protein was found to be expressed in the hair follicle keratinocytes, including the hair bulb, of the WT and YPC during the term of morphogenesis. YPC, which carries a premature termination codon in the last exon of Sgk3 mRNA,7 was confirmed to produce a SGK3 protein, although no visible size reduction was observed.

Figure 3-6804.

Expression of SGK3 protein in ICR (WT, +/+) and Sgk3-mutant YPC mice (YPC-Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc) hair follicle. A: Western blot against protein samples extracted from whole skin of WT and YPC mice at P0, P3, and P5. The top bands are detected against anti-SGK3 antibody, and the bottom bands are against anti-β-actin antibody. SGK3 was equally expressed in both strains at every age examined. No size difference between the WT and YPC was detected in the experiment, and no extra bands were observed in any of the samples examined. B–G: Immunohistochemical detection of SGK3 protein on the paraffin sections of the WT (left) and YPC (right) mice at P0 (B and C), P3 (D and E), and P5 (F and G) skin. Positive signals were observed in the cytoplasm of the hair follicle keratinocytes, especially in hair bulb, ORS, IRS, cuticle/cortex and bulge, or sebaceous glands. Some differences between the WT and YPC, for example, the expression in bulb keratinocytes were observed at P3 and P5. Scale bar, 50 μm.

YPC Shows a Dramatically Altered Hair Cycling Pattern

As mentioned in the introduction, the mammalian hair follicle repeats a cyclic maturation-involution-quiescence pattern called the “hair cycle.” We therefore examined the hair-cycling pattern in YPC mice by measuring the hair follicle length at the level of the thoracolumbar junction at intervals of 2 or 3 days of age until P28 (Figure 4). Until P5, both WT (+/+) and YPC (YPC-Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc) hair follicles continued growing, although the YPC hair follicle was shorter than the WT hair follicle (Figure 4, A–F). However, at P7, the YPC hair follicles began to regress (Figure 4H), and TUNEL-positive pyknotic hair follicle keratinocytes were observed in the regressing hair follicle (Figure 4, O and P), while the hair follicles of WT mice were still in the later stage of postnatal hair follicle morphogenesis (Figure 4G). The above-mentioned morphological characteristics of the YPC hair follicle at P7 highly resembled the catagen, especially stages VI or VII, in normal mice,5,48 and it was considered that the YPC hair follicle completed morphogenesis before P7 and entered catagen at this time. At P11, the YPC hair follicle completely regressed within the dermis and the club hair appeared (Figure 4, A, J, and Q), and such morphological characteristics are highly similar to the telogen phase in normal mice.5 This indicated that, after catagen, the YPC hair follicle entered telogen by P11. At P12, the morphologically characteristic regeneration of hair follicles was observed in YPC mice (Figure 4R), and this indicated that the YPC hair follicle started regeneration. Thus, it was considered that the YPC hair follicle stopped hair morphogenesis earlier than the WT hair follicle. However, after regression and quiescence, the hair follicle regenerated and the hair cycle continued, as the WT hair follicle. In addition, the regenerating hair follicle was also observed in the sections of hair follicles in the dorsal head skin anterior to the section examined in other parts of the YPC mice at P11 (data not shown), suggesting that YPC has the anterior-to-posterior waves in their hair cycle induction pattern, as do WT mice. At P14, the YPC hair follicle maintained its regeneration and regrowth (Figure 4, A, L, and N), while the WT hair follicle entered the first catagen at P18 (Figure 4M). The YPC hair follicle was found to regress again at P21, enter the second telogen at P23 and regenerate again at P28 (Figure 4A, photographs not shown). To evaluate the dynamic regression, quiescence, and regeneration process in YPC quantitatively, we have estimated the percentage of different hair cycle stages in all hair follicles of the YPC mouse dorsal skin from P5 to P14 (Figure 4B). At P5, all hair follicles were in morphogenesis; however, at P7, a part of hair follicles, which were confirmed to be located in the anterior part of the dorsal skin, entered into catagen. At P9, the rate of the catagen follicles increased and some of the telogen follicles appeared. By morphological observation, the wave of catagen spread to the posterior part, and some hair follicles were located anteriorally, where catagen follicles were found at P7, entered telogen at P9. At P11, the rate of hair follicles in anagen got increased with the decrease of catagen and increase of telogen (considered to be the progression of catagen to telogen). At that time, newly regenerated anagen follicles were found in the anterior section. At P14, the anagen hair follicle still continued to increase and almost all catagen follicles changed into telogen. All telogen follicles were located in the posterior section. We also compared hair cycles between the WT (+/+) and YPC type Sgk3 mutant (Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc) from the same F2 littermates between ICR and YPC mice, and such hair cycle alteration as described above was also observed in mutants (Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc), although it was slightly different from the original YPC strain (1 or 2 days). From these results, it was revealed that Sgk3 mutation (Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc) causes severe alteration in hair follicle development and hair-cycling pattern, which were characterized by a drastically shortened postnatal morphogenesis term and anagen.

Figure 4-6804.

Drastically altered hair-cycling pattern in Sgk3-mutant YPC mouse. A: Comparison of the hair-cycling pattern between ICR (WT, +/+) and YPC (YPC-Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc) mice. The hair follicle length, which corresponds to the length from the base of the hair follicle bulb to the surface of the epidermis, represents the hair follicle cycling pattern. Each bar represents the SE. B: Percentage of hair follicles in different hair cycle stages in the YPC mouse from P5 to P14. Orange is anagen or morphogenesis, green is catagen, and blue is telogen. Bars represent SD. C–N: Hair follicle histology of the WT (left) and YPC mice (right) at different ages. At P0, no significant differences were observed between the WT and YPC mice (C and D). However, at P5, the YPC hair follicles are apparently shorter than the WT hair follicles (E and F). At P7 and P11, the WT hair follicles are in anagen (G and I), but, at P7, the YPC hair follicles begin to regress and become shorter than those at P5 (H). Then, they completely regress within the dermis at P11 (J). At P14, the WT hair follicles are in late anagen (K), and the YPC hair follicles grow again (L). At P18, the WT hair follicles are in late catagen (M), while the YPC hair follicles are still growing (N). O–R: Detailed histology of the YPC hair follicle in regression, quiescence, and regeneration phase. At P7, pyknotic keratinocytes are observed in the YPC hair follicle (O, arrowhead), which is positive for TUNEL staining (P, arrowhead). At P11, completely regressed hair follicle with club hair (arrow) is observed (Q), and, at P12, newly formed hair follicle bulb (arrow) and club hair (arrowhead) are observed (R). Scale bars: 100 μm (N); 40 μm (O, R).

The YPC Hair Follicle Has Severe Defects in Hair Shaft Production

From the preliminary observation, no obvious differences between WT and YPC mice were observed at P0, but hair follicles in YPC mice at and after P3 showed irregular structures characterized by small hair bulbs, narrow and immature hair shafts, and a lack of uniform orientation.7 To analyze the defects in hair follicle differentiation in YPC mice in detail, we performed immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analyses on the hair follicles of WT and YPC mice at P3 and P5. AE13 and AE15 are the antibodies against acidic hair keratin and trichohyalin, respectively, which are expressed in the cuticle and cortex and the IRS and medulla, respectively.45,46 Cortex and cuticle were present both in WT and YPC mice at P3 and P5, although each layer in YPC mice seemed to be smaller and thinner than those in WT mice (Figure 5, A–D). IRS was present in YPC mice as well as WT mice at P3 and P5 (Figure 5, E to H). However, the medulla was scarcely found in YPC mice at P5 (Figure 5H), although there was a clear medulla layer observed in the center of the WT hair follicle at P5 (Figure 5F). Because YPC hair follicles started regression at and after P7 (Figure 4), it was considered that hair follicles in YPC mice could not produce hair medulla. We also conducted these immunohistochemical analyses on the sections of the YPC hair follicle at P16 when the first anagen was mostly completed (Figure 4A), and almost the same results were obtained at P5. These findings indicated that hair matrix keratinocytes harboring mutation in Sgk3 (Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc) are able to differentiate into IRS, cuticle, or cortex, but not medulla. For further detailed analyses of the hair follicle developmental defect in YPC mice, ultrastructural analyses were performed. The hair follicle in YPC mice lacked hair medulla at P3 and P5 (Figure 5, J and L), as shown by the immunohistochemical analyses. In addition, the YPC hair follicle also showed defects in the IRS and other hair shaft elements. The IRS keratinocytes in YPC mice were irregular in their size, and the trichohyalin granules were of a larger size (Figure 5, J and L). The cuticles of the hair shafts in YPC mice were arranged irregularly and were partially lacking (Figure 5, J and L). From the observations described above, we have found that YPC mice have severe problems in the production of hair shaft, especially its medulla and cuticle. Moreover, it was also shown that there were some defects in the IRS structure. These results strongly suggest that SGK3 dysfunction severely affects the differentiation process of the hair matrix keratinocytes, especially the hair shaft progenitors.

Figure 5-6804.

Abnormal hair follicle structure in the YPC mouse. A–H: Immunohistochemistry for acidic hair keratin (AE13, A–D) and trichohyalin (AE15, E–H) for the WT and YPC hair follicles. Acidic hair keratin and trichohyalin are expressed in the cuticle and cortex and the IRS and medulla, respectively. In the WT hair follicle, AE13-positive cuticle and cortex are clearly observed at P3 (A) and P5 (B), and the IRS, but not medulla, is positive for AE15 at P3 (E) and both are positive at P5 (F). In the YPC hair follicle, AE13-positive cuticle and cortex are observed in the center of the hair follicle at P3 (C) and P5 (D), and the IRS but not medulla is positive for AE15 at both P3 (G) and P5 (H). I–L: Ultrastructual features of the WT and YPC hair follicles. All hair follicle layers, including the medulla, were clearly observed in the WT hair follicle at P3 (I) and P5 (K). In the YPC hair follicle, irregular sizes of the cells in each sub layer and a larger size of trichohyalin granules are found in the IRS, and an irregular arrangement and partial lack of hair shaft cuticle, and a complete lack of medulla are found in hair shaft at P3 (J) and P5 (L). Scale bars: 60 μm (H); 6 μm (L).

The YPC Hair Follicle Shows Less Proliferating Activity in the Bulb Keratinocytes

Because the hair follicle length and the volume of the hair bulb were considerably different between WT and YPC mice at P5 (Figure 6A),7 we compared the proliferating activity of the hair follicle keratinocytes in WT and YPC mice. Phospho-histone H3 (p-histone H3), which is expressed in the G2-M phase in the cell cycle, was detected by immunohistochemistry, and positive indices were estimated. At P3 and P5, the p-histone H3-positive indices of bulb keratinocytes in the YPC hair follicle were significantly less than those in the WT hair follicle, but the indices of ORS keratinocytes showed no significant differences between WT and YPC mice (Figure 6, A–E). Thus, it was revealed that the keratinocytes in the hair bulb in YPC had less proliferating activity, along with their defective hair shaft differentiation. In addition, there were no significant differences in the proliferation of ORS keratinocytes, suggesting that the shorter hair follicle length in YPC mice is because of the defective hair shaft, which is a result of poor proliferation and differentiation activity of the hair matrix keratinocytes, rather than because of the defect in ORS proliferation.

Figure 6-6804.

Proliferating activity in the WT and YPC hair follicles. A–D: Immunohistochemistry for phospho-histone H3 (p-histone H3). Positive cells correspond to the cells in the G2-M phase of cell cycle. A: WT mice, P3; B: YPC mice, P3; C: WT mice, P5; D: YPC mice, P5. Positive signals are found at the hair bulb, ORS, and a part of epidermal keratinocytes. E: The percentage of p-histone H3-positive keratinocytes in the bulb and ORS. Bars indicate mean ± SE. *P < 0.01, significantly different between WT and YPC mice (Student’s t-test). Scale bar, 50 μm.

Ser9 Phosphorylation of GSK3β Is Suppressed in YPC

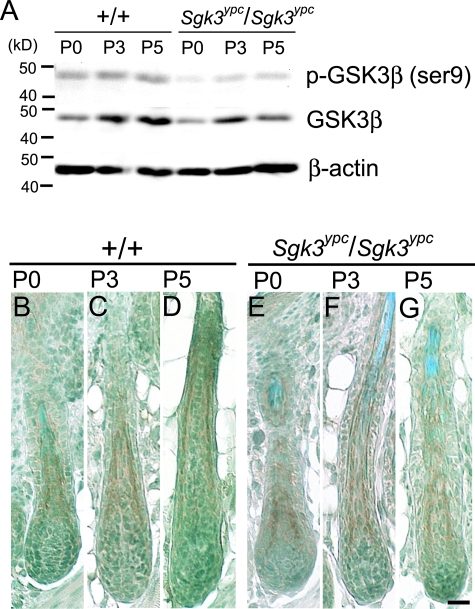

Glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) is an important molecule that contributes both to PI3 Kinase (PI3K) and to WNT-β-catenin pathways.49–51 SGK3 is known to phosphorylate GSK3β at the serine 9 residue (Ser9),18 as well as AKT1,52 and act as a transducer in the PI3K pathway. To know how the point mutation of the Sgk3 gene in YPC influences the SGK3 function in vivo, we examined the Ser9 phosphorylation of GSK3β with Western blot (Figure 7A) and immunohistochemistry (Figure 7, B–G) using protein samples and paraffin sections, respectively, obtained from the dorsal skin of WT and YPC mice at P0, P3, and P5. Western blot revealed that the phosphorylation of GSK3β at Ser9 was apparently suppressed in YPC compared with WT, except P5 when both phospho-GSK3β (Ser9) and total GSK3β protein were reduced (Figure 7A). Thus, Ser9 phosphorylation in GSK3β was revealed to be suppressed, at least in the early term of postnatal morphogenesis, and the SGK3 protein in YPC was suggested to have lower activity than the WT SGK3 protein. We also compared the spatial distribution of Ser9 phosphorylated GSK3β between WT and YPC by immunohistochemistry, and the positive signals were observed in IRS of the hair follicle in YPC as well as the WT (Figure 7, B–G). Thus it is considered that there was no difference in the spatial distribution of Ser9 phosphorylated GSK3β. From the above observations, in Sgk3 mutant YPC mice, the Ser9 phosphorylation of GSK3β was revealed to be suppressed in the early term of hair follicle morphogenesis, with no alteration in the spatial distribution, and it suggests that the SGK3 protein produced in YPC has low activity compared with the WT.

Figure 7-6804.

Ser9 phosphorylation of GSK3β in ICR (WT, +/+) and Sgk3-mutant YPC mice (YPC-Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc) hair follicle. A: Western blot against protein samples extracted from whole skin of the WT and YPC mice at P0, P3, and P5. The top bands are detected with anti-phospho-GSK3β antibody, the middle bands are with anti-GSK3β antibody, and the bottom bands are with anti-β-actin antibody. At P0 and P3, the amount of total GSK3β protein in YPC is the same as that in the WT; however, Ser9-phosphorylated GSK3β is apparently less than the WT. At P5, both total GSK3β and phospho-GSK3β (Ser9) in YPC are less than those in the WT. B–G: Immunohistochemistry against phospho-GSK3β (Ser9) on the paraffin sections of WT (B, D, F) and YPC (C, E, G) dorsal skin at P0, P3, and P5. In both strains, Ser9-phosphorylated GSK3β is detected in the IRS of hair follicle at every age examined. No difference in the spatial distribution of phospho-GSK3β (Ser9) was observed between the two strains. Scale bar, 60 μm.

WNT Pathway Could Be Related to the Defective Hair Follicle Development in YPC

As mentioned in the introduction, WNT and BMP pathways and GATA3 are known to play important roles in postnatal hair follicle development, so we immunostained some key molecules included in these pathways. β-Catenin (gene symbol name is Ctnnb1) is known to translocate and accumulate into the nucleus and form a transcriptional complex with LEF1, in response to the extracellular WNT stimulation,53 and thus the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin represents the activity of WNT signaling. In the WT hair follicles, the yellow signals of the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin were observed in the hair matrix (arrows), and more strongly in the precortex area (arrowheads) at P3 and P5 (Figure 8, A and C). However, in YPC mice, there were only few signals observed in the upper part of the matrix (arrows) at P3 and P5, although the signals became more prominent at P5 (Figure 8, B and D). From the above-mentioned observations, it was suggested that the WNT signaling pathway is less activated in YPC mice than in WT mice, especially in the hair matrix where the hair shaft and IRS progenitors proliferate and begin to differentiate. We next performed immunohistochemistry for phospho-SMAD1/5/8, which is phosphorylated and then translocated in nuclei in response to the adapting of BMP2, -4, and -7 to their transmembrane receptors.54 In the WT hair follicles, nuclear-positive signals were observed in IRS, in the middle and upper (premedulla or precortex) area of the hair matrix and, although not in all of the follicles, in the dermal papilla in both strains at every age (Figure 8, E–H). Thus, it was suggested that the alteration of SGK3 function in YPC mice did not affect the BMP pathway, at least in the stage of postnatal hair follicle development. Finally, we immunostained GATA3, which is a member of the GATA family zinc finger transcription factors, which play key roles in cell fate decision, especially in hematopoietic lineages. The expression of GATA3 was restrictedly observed in the IRS in every strain and age examined (Figure 8, I–L), and therefore it is considered that the mutation in Sgk3 does not affect the GATA3 spatial expression pattern.

Figure 8-6804.

A–D: Immunofluorescence for β-catenin of the WT hair follicles at P3 (A) and P5 (C) and of the YPC hair follicles at P3 (B) and P5 (D). Green and red signals are β-catenin and propidium iodide, respectively. Nuclear β-catenin is seen as a yellow signal (arrowheads). E–H: Immunohistochemistry for phospho-smad1/5/8 of the WT hair follicle at P3 (E) and P5 (G) and of the YPC hair follicle at P3 (F) and P5 (H). I–L: Immunohistochemistry for GATA3 of the WT hair follicle at P3 (I) and P5 (K) and of the YPC hair follicle at P3 (J) and P5 (L). Insets in J and L show higher magnification of the positive cells. Scale bars, 60 μm.

Discussion

In the present study, we have examined the morphological and molecular characteristics of hair follicle of the Sgk3 mutant YPC mouse (YPC-Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc). YPC has a nonsense mutation in the Sgk3 gene and the mutation is located in the last exon, when transcribed to mRNA. In our study, at first, the SGK3 protein was confirmed to be expressed in YPC, and it was strongly suggested that the SGK3 protein in YPC is somehow truncated. In addition, the investigation revealed that the mutation causes two major defects in the hair follicle. One is the defect in proliferation and differentiation in hair follicle development, both of which are needed for hair shaft production, and the other is the defective hair cycle characterized by drastically shortened morphogenesis and anagen terms. Many mutants are known to show hair loss or a poor/altered hair coat phenotype,44,55,56 but the reports of the mutants that carry severe defects both in hair follicle differentiation and hair cycling are very rare. However, considering the hair follicle homeostasis, hair follicle development/maturation and the hair cycle are considered to be closely related to each other and they need not be thought of separately.2,21,22 The YPC mice presented in this study are very useful in the study of hair follicle development and homeostasis, in addition to other rare mutants that carry two-way defects, such as Msx2 mutant mice.40 Moreover, the presence of SGK3 protein in YPC and the fact that in the gross phenotype YPC is different from Sgk3 KO, which do not produce SGK3, are both extremely interesting matters and we believe that these unique results can provide very important insights for the understanding of molecular hair follicle biology.

We first examined the expression of Sgk3 mRNA and SGK3 protein in the WT hair follicle, and the protein expression was also examined in YPC, to confirm whether the mutation influences SGK3 protein translation or not. In the WT hair follicle, Sgk3 mRNA expression was detected in the IRS of the developing hair follicle (Figure 1), and the protein expression of SGK3 was detected in the keratinocytes of the hair bulb, ORS, IRS, cuticle/cortex, and bulge or sebaceous glands (Figure 2). We are considering that the difference between the results of the spatial distribution of mRNA and protein comes from the difference in the sensitivity of RNA probe and antibody. In fact, at P0, when the expression of mRNA or protein was confirmed with RT-PCR, Western blot, and immunohistochemistry, no expression was observed with in situ hybridization.7 In the WT hair follicle, SGK3 is expressed in most hair follicle keratinocytes other than the hair medulla. The expression was most prominent in the hair bulb (Figure 2) and it strongly suggests that SGK3 deeply contributes to the hair bulb keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation process, and this hypothesis is reinforced by the fact that the hair bulb keratinocytes in Sgk3-mutant YPC showed defective differentiation (Figure 5) and proliferation (Figure 6) status. The expression of SGK3 protein was also observed in ORS, including the bulge, IRS, cuticle/cortex, and sebaceous glands, and it suggests that SGK3 plays some role in these areas. However, no obvious defects were observed in these areas in YPC, but we think this is not conflictive because the hair follicle is a complex organ and each compartment of the follicle is considered to orchestrate together for the development and homeostasis of the hair follicle, and not all defects appear as morphological defects.

Western blot and immunohistochemistry revealed that YPC mice produce SGK3 protein in their hair follicle (Figure 2). Recently, a mutant mammalian gene that carries a premature termination codon is considered to be eliminated at the mRNA level by nonsense-mediated decay.57–59 However, there are some exceptions that cause its mRNA to be decayed and produce protein through transcription, although they have a premature termination codon in their exon area. One representative of the exceptions is the case when the premature termination codon is located in the last exon.57–59 In YPC, the nonsense mutation is at codon 461 and the mutation-triggered termination codon in Sgk3 is located in the last exon7 (for detailed information of the structure of Sgk3 mRNA, please see the NCBI Entrez Gene database at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=gene&cmd=Retrieve&dopt=full_report&list_uids=170755#ubor36_RefSeq). Thus, we think that it is very reasonable for YPC to express the SGK3 protein. Actually, we are considering that the SGK3 protein in YPC is a key matter to elucidate the SGK3 function in the hair follicle. As shown in the gross phenotype of Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc of the C57BL/6J background (Figure 1), YPC or Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc is considered to be different from two strains with target disruption of Sgk3 (Sgk3tm1Dpea/Sgk3tm1Dpea and Sgk3tm1Efu/Sgk3tm1Efu),8,9 both of which do not express Sgk3 mRNA, in their hair follicle and hair phenotype. Namely, the most characteristic gross morphology in the two Sgk3-null mutant strain is their sparse hairs,8,9 however, our Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc carries very short and sparse hair compared to WT and shows the resultant bald-like phenotype (Figure 1). The defective hair-cycling pattern characterized by the dramatically shortened terms of postnatal morphogenesis and anagen is a very interesting feature of YPC (Figure 4), and the characteristic short hair of YPC mice (Figure 1) is considered to be due to the shortening of the hair-growing term (morphogenesis and anagen). However, in the studies of two independent Sgk3-null mutant strains, both of which did not show the drastically short-haired phenotype as observed in YPC, it was reported as the morphogenesis and anagen term were not shortened, but slightly prolonged8 or as only the morphogenesis term is shortened.9 We believe that such a phenotypic difference between two Sgk3 mutants must result from an allelic difference between the strains, one is protein-producing mutant and the others are null mutants. Therefore, how the functions of SGK3 protein in YPC are altered due to mutation is a very important problem.

Before discussing how the SGK3 protein function may be altered due to the mutation in YPC, the structural characteristics of SGK3 should be mentioned. SGK3 consists of a location-regulative PX domain, kinase domain, and C-term hydrophobic domain, and has two regulatory sites to be phosphorylated, Thr320 and Ser468.11,14 AKT1 has three domains as well as SGK3, and also has two phosphorylation sites (Thr308 and Ser473), and so SGK3 and AKT1 are structurally very much alike, without the matter that AKT1 has a PH domain instead of a PX domain in SGK3 (PH and PX domains are both considered to regulate intracellular location.16,17 ). Moreover, both molecules are known to be equally regulated under PI3Kinase11,14,52 and to share some substrates, such as GSK3β or FOXO3A.11,19 Thus, although the detailed function or regulatory mechanism of SGK3 remains unknown, we believe that the knowledge about AKT1 can strongly help us to understand the structure-activity relationship of SGK3. Recently, the C-terminal hydrophobic domain and Ser473 were revealed to be very important in the phosphorylation and activation process of AKT1.60 Thus, we hypothesize that the C-term hydrophobic domain and Ser468 are also critical in SGK3 activation, and based on this hypothesis, theoretically, the Ser468-losing SGK3 protein in YPC7 would be considered to have less activity than that in the WT, when phosphorylated. Our results that the phosphorylation of GSK3β at Ser9, which is one of the substrates of SGK3, is suppressed in YPC (Figure 7), strongly supports this hypothesis. How far the nonsense mutation in YPC and resultant partial lack of the C-term domain disturbs the activity of SGK3 protein is still obscure, however, considering that the gross phenotype in Sgk3-null mutants (Sgk3tm1Dpea/Sgk3tm1Dpea and Sgk3tm1Efu/Sgk3tm1Efu) and Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc is different, the activity status of the SGK3 protein in YPC could be very low but not completely suppressed. In fact, in the case of AKT1, it can only have very low activity, without phosphorylation of the C-term hydrophobic motif.60

We have shown that, in the early stage of postnatal hair follicle development, the Sgk3-mutant YPC hair follicle has a severe defect in the hair shaft differentiation characterized by the loss of the hair medulla and an irregular cortex and cuticle (Figure 5). Also, poor proliferating activity in the hair bulb was observed in YPC mice (Figure 5). In the period of postnatal hair follicle differentiation, many signaling molecules are expressed in the dermal papilla or hair shaft and IRS precursor cells, such as Bmp4 and noggin (Nog) (dermal papilla) or Bmp2 and Bmp4 (precursors)29,31 in BMP signaling, LEF1, Wnt3, Dishevelled2 (Dvl2) (precursors) in WNT signaling,22,23 or GATA341 for the control of the proliferation and differentiation of the hair shaft or IRS precursor keratinocytes.6 In the present study, we have examined the expression of GATA3 transcription factor and phospho-SMAD1/5/8 (marker for BMP signaling) (Figure 6), but no differences between the WT and YPC mice were observed in their expression pattern. We have examined the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin using the immunofluorescence method (Figure 6), and the accumulation was reduced in YPC mice. This suggests that SGK3 somehow affects the WNT-β-catenin signaling pathway in the hair matrix and interferes with matrix keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation by some means. In relation to this, the phosphorylation of the Ser9 residue in GSK3β, which is one of the substrates for SGK3,19 is suppressed in the early phase of postnatal morphogenesis (Figure 7). This strongly suggests that the SGK3 protein in YPC has less activity and that SGK3 is involved in a hair follicle morphogenesis mechanism through the phosphorylation of Ser9 of GSK3β. GSK3β is a unique Ser/Thr kinase, which is constitutively active and becomes inhibited in response to phosphorylation due to an extracellular signal, and is known to be a transducer in both PI3K and WNT signaling.49–51 When unphosphorylated, GSK3β phosphorylates its substrates and induces them to degrade. Phosphorylation of GSK3β suppresses its activity and protects its substrates from degradation: the representatives of the substrates are glycogen synthase in PI3K pathway and β-catenin in WNT signaling, although β-catenin degradation is a very much more complex process than that in glycogen synthase.61 Ser9 is confirmed to be phosphorylated under the PI3K pathway with AKT150,51 and SGK319 by extracellular insulin or a growth factor signal, but not under a WNT signal and no obvious cross-talk between insulin and WNT signaling, through GSK3β, was confirmed.62 However, some reports mentioned that the decrease in GSK3β activity is sometimes sufficient to lead to downstream events, such as how lithium chloride, the noncompetitive inhibitor of GSK3β, is sufficient to mimic insulin in adipocytes63 and WNT signaling in Drosophila cells,64 and HGF up-regulates the β-catenin level along with GSK3β down-regulation.65 Thus, it still remains to be clarified whether the phosphorylation of Ser9 in GSK3β by SGK3 directly influences the WNT signaling and the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin or not.

The defective hair-cycling pattern characterized by the dramatically shortened terms of postnatal morphogenesis and anagen is a very interesting feature of YPC mice (Figure 4), and the characteristic short hair of YPC mice (Figure 1) is considered to be due to the shortening of the hair-growing term (morphogenesis and anagen). The regeneration of the YPC hair follicle after catagen (Figure 4) indicates that the YPC hair follicle is able to activate bulge stem cells for regeneration, unlike the hairless (Hr) mutant.21 How SGK3 controls the hair cycle is still obscure. However, because SGK3 is thought to act as an anti-apoptotic molecule,10,11 we suspect that SGK3 may play an important role in the maintenance of anagen through the regulation of the keratinocyte survival, in response to the activation of PI3K by extracellular growth factor stimuli. We consider that IGF1, which is known to prolong the duration of anagen,66–69 is one of the strong candidates for the stimulating factor. In association with this, the absorbing point is that the hair-cycle alteration in YPC was different from that observed in mice with target disruption of Sgk3 (Sgk3tm1Dpea/Sgk3tm1Dpea and Sgk3tm1Efu/Sgk3tm1Efu),8,9 as mentioned above. Sgk3tm1Dpea/Sgk3tm1Dpea and Sgk3tm1Efu/Sgk3tm1Efu did not show the drastically short-haired phenotype as observed in YPC mice, and in the reports by McCormick and colleagues,8 morphogenesis and the anagen term were not shortened, but slightly prolonged. On the contrary, in the recent study done by Alonso and colleagues,9 the shortening of the morphogenesis term was observed but the following anagen was not examined in detail. By comparing the gross morphology of Sgk3tm1Dpea/Sgk3tm1Dpea and Sgk3tm1Efu/Sgk3tm1Efu8,9 and Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc of B6 background (Figure 1) in the developing stage, we are considering that the difference first arises at ∼P20 to P25 (before this, these strains are very much alike in their gross appearance), when first anagen finishes in YPC. Therefore, it is strongly suggested that the gross morphological difference may arise from the difference in the ability of the maintenance of morphogenesis/anagen term, and that is further due to the allelic difference of the Sgk3 gene between the YPC and Sgk3tm1Dpea/Sgk3tm1Dpea or Sgk3tm1Efu/Sgk3tm1Efu: one produces protein and the other does not. The detailed function of the possibly truncated SGK3 in YPC was partially revealed by the analysis of the phosphorylation of GSK3β (Ser9); however, many aspects remain to be clarified. In our hypothesis, the activity of SGK3 protein in YPC is much lower than that of the WT, and the hair follicle morphogenesis process was disturbed as effectively as in the mice with artificially disrupted Sgk3, but different from them, the SGK3 protein in YPC is possible to take some part in the hair-cycle regulation system, especially anagen maintenance or the start of catagen, by the alteration of the response to growth factors, such as IGF1. How the SGK3 protein in YPC functions in anagen maintenance and how it is different from the WT and null mutants is still obscure, but there are some possibilities that can be predicted. One possibility is that the activity of the truncated SGK3 was much lower than that in the WT, but not completely abolished as in the null mutants, and the difference came to the surface when it received the signal for anagen maintenance. Another possibility is the case in which some kind of bypass pathways, which should activated instead of SGK3 in anagen maintenance, successfully functioned in KO, but not in YPC, due to the existence of the truncated SGK3 protein. Regardless, we strongly believe that this phenotypic difference between the Sgk3-mutants would be very helpful for the understanding the roles of SGK3 in hair follicle homeostasis and the hair-cycling mechanism.

We have found that the mutation in the intracellular kinase gene, Sgk3, interferes with hair follicle development, hair shaft production, and the maintenance of anagen. Although we have suggested that the phosphorylation of GSK3β and accumulation of β-catenin are possibly involved in these events, the detailed pathways still remain unknown. However, many aspects, such as the relation between the difference of the phenotype as the hair-cycling pattern between Sgk3-null mutants and their mutant alleles, show that SGK3 and its mutants provide very important insights into hair follicle biology, and also, genetics. Our next goal is to clarify the detailed characteristics of the mutant SGK3 protein in YPC and compare Sgk3ypc/Sgk3ypc to Sgk3-null mutants in detail, and to explore the relationship of the protein to the phenotype, especially in the hair-cycle regulation system.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. T.T. Sun (New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY) for the kind gift of AE13 and AE15 antibodies.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Taro Okada, Department of Veterinary Pathology, Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, The University of Tokyo, Yayoi 1-1-1, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8657, Japan. E-mail: aa37158@mail.ecc.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Current address of J.M.: National Institute of Biomedical Innovation, Saito-Asagi 7-6-8, Ibaraki, Osaka 567-0085.

References

- Fuchs E, Merrill BJ, Jamora C, DasGupta R. At the roots of a never-ending cycle. Dev Cell. 2001;1:13–25. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenn KS, Paus R. Controls of hair follicle cycling. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:449–494. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemann C, Watt FM. Designer skin: lineage commitment in postnatal epidermis. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:185–192. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus R, Cotsarelis G. The biology of hair follicles. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:491–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908123410706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Rover S, Handjiski B, van der Veen C, Eichmuller S, Foitzik K, McKay IA, Stenn KS, Paus R. A comprehensive guide for the accurate classification of murine hair follicles in distinct hair cycle stages. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:3–15. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosawa S, Ogura A, Koura M, Noguchi A, Noguchi Y, Yamamoto Y, Takano K. A histological study on the skin and hairs of PC (poor coat) mice. Jikken Dobutsu. 1991;40:259–261. doi: 10.1538/expanim1978.40.2_259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masujin K, Okada T, Tsuji T, Ishii Y, Takano K, Matsuda J, Ogura A, Kunieda T. A mutation in the serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase-like kinase (Sgkl) gene is associated with defective hair growth in mice. DNA Res. 2004;11:371–379. doi: 10.1093/dnares/11.6.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick JA, Feng Y, Dawson K, Behne MJ, Yu B, Wang J, Wyatt AW, Henke G, Grahammer F, Mauro TM, Lang F, Pearce D. Targeted disruption of the protein kinase SGK3/CISK impairs postnatal hair follicle development. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:4278–4288. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-01-0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso L, Okada H, Pasolli HA, Wakeham A, You-Ten AI, Mak TW, Fuchs E. Sgk3 links growth factor signaling to maintenance of progenitor cells in the hair follicle. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:559–570. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200504131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai F, Yu L, He H, Zhao Y, Yang J, Zhang X, Zhao S. Cloning and mapping of a novel human serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase-like gene, SGKL, to chromosome 8q12.3-q13.1. Genomics. 1999;62:95–97. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Yang X, Songyang Z. Identification of CISK, a new member of the SGK kinase family that promotes IL-3-dependent survival. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1233–1236. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00733-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantley LC. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science. 2002;296:1655–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong ML, Maiyar AC, Kim B, O’Keeffe BA, Firestone GL. Expression of the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible protein kinase, Sgk, is a cell survival response to multiple types of environmental stress stimuli in mammary epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:5871–5882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211649200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Cohen P. Activation of serum- and glucocorticoid-regulated protein kinase by agonists that activate phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase is mediated by 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1) and PDK2. Biochem J. 1999;339:319–328. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Hill MM, Hess D, Brazil DP, Hofsteenge J, Hemmings BA. Identification of tyrosine phosphorylation sites on 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 and their role in regulating kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37459–37471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105916200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Liu D, Gill G, Songyang Z. Regulation of cytokine-independent survival kinase (CISK) by the Phox homology domain and phosphoinositides. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:699–705. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virbasius JV, Song X, Pomerleau DP, Zhan Y, Zhou GW, Czech MP. Activation of the Akt-related cytokine-independent survival kinase requires interaction of its phox domain with endosomal phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12908–12913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221352898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen T, Slagsvold T, Skjerpen CS, Brech A, Stenmark H, Olsnes S. Peroxisomal targeting as a tool for assaying protein-protein interactions in the living cell: cytokine-independent survival kinase (CISK) binds PDK-1 in vivo in a phosphorylation-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4794–4801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309653200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai F, Yu L, He H, Chen Y, Yu J, Yang Y, Xu Y, Ling W, Zhao S. Human serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase-like kinase (SGKL) phosphorylates glycogen syntheses kinase 3 beta (GSK-3beta) at serine-9 through direct interaction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;293:1191–1196. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00349-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar SE. Molecular mechanisms regulating hair follicle development. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:216–225. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panteleyev AA, Jahoda CA, Christiano AM. Hair follicle predetermination. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3419–3431. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.19.3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus R, Foitzik K. In search of the “hair cycle clock”: a guided tour. Differentiation. 2004;72:489–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2004.07209004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DasGupta R, Fuchs E. Multiple roles for activated LEF/TCF transcription complexes during hair follicle development and differentiation. Development. 1999;126:4557–4568. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.20.4557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar SE, Willert K, Salinas PC, Roelink H, Nusse R, Sussman DJ, Barsh GS. WNT signaling in the control of hair growth and structure. Dev Biol. 1999;207:133–149. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto J, Burgeson RE, Morgan BA. Wnt signaling maintains the hair-inducing activity of the dermal papilla. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1181–1185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy S, Andl T, Bagasra A, Lu MM, Epstein DJ, Morrisey EE, Millar SE. Characterization of Wnt gene expression in developing and postnatal hair follicles and identification of Wnt5a as a target of Sonic hedgehog in hair follicle morphogenesis. Mech Dev. 2001;107:69–82. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00452-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamora C, DasGupta R, Kocieniewski P, Fuchs E. Links between signal transduction, transcription and adhesion in epithelial bud development. Nature. 2003;422:317–322. doi: 10.1038/nature01458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andl T, Ahn K, Kairo A, Chu EY, Wine-Lee L, Reddy ST, Croft NJ, Cebra-Thomas JA, Metzger D, Chambon P, Lyons KM, Mishina Y, Seykora JT, Crenshaw EB, III, Millar SE. Epithelial Bmpr1a regulates differentiation and proliferation in postnatal hair follicles and is essential for tooth development. Development. 2004;131:2257–2268. doi: 10.1242/dev.01125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchkarev VA, Botchkareva NV, Roth W, Nakamura M, Chen LH, Herzog W, Lindner G, McMahon JA, Peters C, Lauster R, McMahon AP, Paus R. Noggin is a mesenchymally derived stimulator of hair-follicle induction. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:158–164. doi: 10.1038/11078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchkarev VA, Botchkareva NV, Sharov AA, Funa K, Huber O, Gilchrest BA. Modulation of BMP signaling by noggin is required for induction of the secondary (nontylotrich) hair follicles. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:3–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchkarev VA. Bone morphogenetic proteins and their antagonists in skin and hair follicle biology. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:36–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulessa H, Turk G, Hogan BL. Inhibition of Bmp signaling affects growth and differentiation in the anagen hair follicle. EMBO J. 2000;19:6664–6674. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.24.6664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobielak K, Pasolli HA, Alonso L, Polak L, Fuchs E. Defining BMP functions in the hair follicle by conditional ablation of BMP receptor IA. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:609–623. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuhki M, Yamada M, Kawano M, Iwasato T, Itohara S, Yoshida H, Ogawa M, Mishina Y. BMPR1A signaling is necessary for hair follicle cycling and hair shaft differentiation in mice. Development. 2004;131:1825–1833. doi: 10.1242/dev.01079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guha U, Mecklenburg L, Cowin P, Kan L, O’Guin WM, D’Vizio D, Pestell RG, Paus R, Kessler JA. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling regulates postnatal hair follicle differentiation and cycling. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:729–740. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63336-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mill P, Mo R, Fu H, Grachtchouk M, Kim PC, Dlugosz AA, Hui CC. Sonic hedgehog-dependent activation of Gli2 is essential for embryonic hair follicle development. Genes Dev. 2003;17:282–294. doi: 10.1101/gad.1038103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LC, Liu ZY, Gambardella L, Delacour A, Shapiro R, Yang J, Sizing I, Rayhorn P, Garber EA, Benjamin CD, Williams KP, Taylor FR, Barrandon Y, Ling L, Burkly LC. Regular articles: conditional disruption of hedgehog signaling pathway defines its critical role in hair development and regeneration. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;114:901–908. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michno K, Boras-Granic K, Mill P, Hui CC, Hamel PA. Shh expression is required for embryonic hair follicle but not mammary gland development. Dev Biol. 2003;264:153–165. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00401-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oro AE, Higgins K. Hair cycle regulation of Hedgehog signal reception. Dev Biol. 2003;255:238–248. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Liu J, Wu T, Plikus M, Jiang TX, Bi Q, Liu YH, Muller-Rover S, Peters H, Sundberg JP, Maxson R, Maas RL, Chuong CM. ‘Cyclic alopecia’ in Msx2 mutants: defects in hair cycling and hair shaft differentiation. Development. 2003;130:379–389. doi: 10.1242/dev.00201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman CK, Zhou P, Pasolli HA, Rendl M, Bolotin D, Lim KC, Dai X, Alegre ML, Fuchs E. GATA-3: an unexpected regulator of cell lineage determination in skin. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2108–2122. doi: 10.1101/gad.1115203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert JM, Rosenquist T, Gotz J, Martin GR. FGF5 as a regulator of the hair growth cycle: evidence from targeted and spontaneous mutations. Cell. 1994;78:1017–1025. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg JP, Rourk MH, Boggess D, Hogan ME, Sundberg BA, Bertolino AP. Angora mouse mutation: altered hair cycle, follicular dystrophy, phenotypic maintenance of skin grafts, and changes in keratin expression. Vet Pathol. 1997;34:171–179. doi: 10.1177/030098589703400301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpentier E, Lavker RM, Acquista E, Cowin P. Plakoglobin suppresses epithelial proliferation and hair growth in vivo. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:503–520. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.2.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch MH, O’Guin WM, Hardy C, Mak L, Sun TT. Acidic and basic hair/nail (“hard”) keratins: their colocalization in upper cortical and cuticle cells of the human hair follicle and their relationship to “soft” keratins. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:2593–2606. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.6.2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Guin WM, Sun TT, Manabe M. Interaction of trichohyalin with intermediate filaments: three immunologically defined stages of trichohyalin maturation. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;98:24–32. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12494172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavrieli Y, Sherman Y, Ben-Sasson SA. Identification of programmed cell death in situ via specific labeling of nuclear DNA fragmentation. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:493–501. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.3.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner G, Botchkarev VA, Botchkareva NV, Ling G, van der Veen C, Paus R. Analysis of apoptosis during hair follicle regression (catagen). Am J Pathol. 1997;151:1601–1617. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez I, Green JB. Missing links in GSK3 regulation. Dev Biol. 2001;235:303–313. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frame S, Cohen P. GSK3 takes centre stage more than 20 years after its discovery. Biochem J. 2001;359:1–16. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3590001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearl LH, Barford D. Regulation of protein kinases in insulin, growth factor and Wnt signalling. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2002;12:761–767. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00386-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross DA, Alessi DR, Cohen P, Andjelkovich M, Hemmings BA. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature. 1995;378:785–789. doi: 10.1038/378785a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon RT, Bowerman B, Boutros M, Perrimon N. The promise and perils of Wnt signaling through beta-catenin. Science. 2002;296:1644–1646. doi: 10.1126/science.1071549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attisano L, Wrana JL. Signal transduction by the TGF-beta superfamily. Science. 2002;296:1646–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1071809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panteleyev AA, Botchkareva NV, Sundberg JP, Christiano AM, Paus R. The role of the hairless (hr) gene in the regulation of hair follicle catagen transformation. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:159–171. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65110-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M, Sundberg JP, Paus R. Mutant laboratory mice with abnormalities in hair follicle morphogenesis, cycling, and/or structure: annotated tables. Exp Dermatol. 2001;10:369–390. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2001.100601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook JA, Neu-Yilik G, Hentze MW, Kulozik AE. Nonsense-mediated decay approaches the clinic. Nat Genet. 2004;36:801–808. doi: 10.1038/ng1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maquat LE. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in mammals. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:1773–1776. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson MF. A new function for nonsense-mediated mRNA-decay factors. Trends Genet. 2005;21:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Cron P, Thompson V, Good VM, Hess D, Hemmings BA, Barford D. Molecular mechanism for the regulation of protein kinase B/Akt by hydrophobic motif phosphorylation. Mol Cell. 2002;9:1227–1240. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00550-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Li Y, Semenov M, Han C, Baeg GH, Tan Y, Zhang Z, Lin X, He X. Control of beta-catenin phosphorylation/degradation by a dual-kinase mechanism. Cell. 2002;108:837–847. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00685-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding VW, Chen RH, McCormick F. Differential regulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta by insulin and Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32475–32481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005342200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng K, Creacy S, Larner J. ‘Insulin-like’ effects of lithium ion on isolated rat adipocytes. I. Stimulation of glycogenesis beyond glucose transport. Mol Cell Biochem. 1983;56:177–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00227218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stambolic V, Ruel L, Woodgett JR. Lithium inhibits glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity and mimics wingless signalling in intact cells. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1664–1668. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70790-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papkoff J, Aikawa M. WNT-1 and HGF regulate GSK3 beta activity and beta-catenin signaling in mammary epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;247:851–858. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudman SM, Philpott MP, Thomas GA, Kealey T. The role of IGF-I in human skin and its appendages: morphogen as well as mitogen? J Invest Dermatol. 1997;109:770–777. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12340934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su HY, Hickford JG, Bickerstaffe R, Palmer BR. Insulin-like growth factor 1 and hair growth. Dermatol Online J. 1999;5:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikawa A, Ishii Y, Suzuki K, Yasoshima A, Suzuki N, Nakayama H, Takahashi S, Doi K. Age-related changes in the dorsal skin histology in Mini and Wistar rats. Histol Histopathol. 2002;17:419–426. doi: 10.14670/HH-17.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philpott MP, Sanders DA, Kealey T. Effects of insulin and insulin-like growth factors on cultured human hair follicles: IGF-I at physiologic concentrations is an important regulator of hair follicle growth in vitro. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:857–861. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12382494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]