Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease is a multifactorial, progressive, age-related neurodegenerative disease. In familial Alzheimer’s disease, Aβ is excessively produced and deposited because of mutations in the amyloid precursor protein, presenilin-1, and presenilin-2 genes. Here, we generated a double homozygous knock-in mouse model that incorporates the Swedish familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations and converts mouse Aβ to the human sequence in amyloid precursor protein and had the P264L familial Alzheimer’s disease mutation in presenilin-1. We observed Aβ deposition in double knock-in mice beginning at 6 months as well as an increase in the levels of insoluble Aβ1-40/1-42. Brain homogenates from 3-, 6-, 9-, 12-, and 14-month-old mice showed that protein levels of manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) were unchanged in the double knock-in mice compared to controls. Genotype-associated increases in nitrotyrosine levels were observed. Protein immunoprecipitation revealed MnSOD as a target of this nitration. Although the levels of MnSOD protein did not change, MnSOD activity and mitochondrial respiration decreased in knock-in mice, suggesting compromised mitochondrial function. The compromised activity of MnSOD, a primary antioxidant enzyme protecting mitochondria, may explain mitochondrial dysfunction and provide the missing link between Aβ-induced oxidative stress and Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a multifactorial, progressive age-related neurodegenerative disease that affects more than four million persons in the United States.1 The pathological hallmarks of AD are extracellular Aβ deposits, neurofibrillary tangles, synaptic loss, and neuronal degeneration. Aβ plaques are composed of 40- and 42-mer peptides (Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42) that are proteolytically produced from amyloid precursor protein (APP).2 Three genes, presenilin 1 (PS-1), PS-2, and APP are causatively linked with the pathogenesis of early onset familial AD (FAD). The findings that Aβ is central to the pathogenesis of AD3 and that the AD brain is under significant oxidative stress were united into a comprehensive model for neurodegeneration in the brain in AD based on Aβ-associated free radical generation.4 The brain in AD has marked oxidative damage as manifested by increased protein oxidation, lipid peroxidation, free radical formation,4 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) levels,5,6 advanced glycation end products,7 and DNA/RNA oxidation products.8,9

Manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) is a homotetramer consisting of identical 24-kd subunits. The translated precursor in cytosol contains an N-terminal 24-amino acid sequence signaling mitochondrial compartmentalization. The mature protein protects the cells against cytotoxic O2−.. The importance of this enzyme is evident from MnSOD knockout mice that suffer from a defect of mitochondrial iron-sulfur centers, a modification proving lethal to newborns.10,11 Activity of this antioxidant enzyme declines in the aging process.12 Because the AD brain is under intense oxidative stress, any dysfunction of MnSOD may lead to progression of the disease.

Peroxynitrite anion (ONOO−) is a potent biological oxidant that has been implicated in diverse forms of free radical-induced tissue injury.13 Peroxynitrite is produced by the reaction of O2−. and .NO, and this peroxynitrite can compromise the functional and/or structural integrity of target proteins.14 Increased levels of nitrotyrosine5 and 4-hydroxynonenal15 are associated with degenerating neurons in AD, suggesting pathogenic roles of peroxynitrite and membrane lipid peroxidation in this disease.

Mutations in the APP gene and PS-1 gene lead to increased levels of Aβ, which appear to contribute to the disease process. One study demonstrated altered levels of Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 distinguish AD from normal aging.16 Recently, several transgenic animals have been shown to have increased Aβ peptide deposition and some of the pathological characteristics similar to AD patients.17,18 Crossing APP-Tg mutant mice and PS-1-Tg mutant mice resulted in increased Aβ production and accelerated amyloid deposition in the brains of these animals.19,20 However, increased Aβ levels in these models may, in part, be attributable to an increase in copy number of the transgene.

The aim of this study was to use a mouse model that resembles the natural progression of Aβ pathology similar to that observed in AD patients and to gain insight into potential causes of the mitochondrial alterations that occur during the progression of AD. The model that we used is a homozygous knock-in APPNLh/NLh X PS-1P264L/P264L (APP/PS-1).21,22 The results presented here demonstrate that these mice have an age-dependent accumulation of Aβ in the brain, consistent with an increase in both Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 and an accelerated decline in mitochondrial function associated with a decrease in activity of MnSOD because of nitration. These results suggest a novel Aβ-mediated nitrative inactivation of MnSOD and inhibition of mitochondrial function in AD.

Materials and Methods

Mutant Mouse Lines

APPNLh/NLh X PS-1P264L/P264L mutant mice were generated using the Cre-lox knock-in technology.21,22 The APP strategy introduced the Swedish FADK670N/M671L mutations and changed the mouse sequence for Aβ to be identical to the human sequence (NLh). These mice demonstrate proper cleavage of the APP protein to generate the Aβ peptide. The PS-1 mutation targeted codons 264 and 265 of the mouse PS-1 gene to introduce the proline to leucine (P264L) mutation. When PS-1 mutant mice (P264L) are crossed with the mutant APP mice (NLh), the mutations are driven by the endogenous promoters of the APP and PS-1 genes, and expression is limited to the replacement of these two endogenous genes and not by the expression of multiple transgenes.

Genotyping of Mice

APP/PS-1 mice were maintained on a CD-1/129 background. Wild-type (WT) mice were obtained from heterozygous APP/PS-1 matings and maintained as a separate line for use as controls. The APP/PS-1 mutant mice were monitored for maintenance of the knock-in gene by PCR analysis of tail snip DNA.21 The APP NLh mutation was screened with primers spanning the loxp sequence in intron 15 of the targeted locus (5′-CACACCAAGAAGTACAATAGAGGG-3′ and 5′-CCTGGGTTGTAGGGACTGTACTTG-3′) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). WT mice showed a single band at 214 bp, whereas the homozygous mutant mice had a single band at 298 bp. The PS-1 P264L mutation was identified using primers spanning exon 8 (5′-CCCGTGGAGGTCAGAAGTCAG-3′ and 5′-TTACGGGTTGAGCCATGAATG-3′)22 (Invitrogen). WT mice showed a single band at 142 bp, whereas the homozygous PS-1 knock-in mutant mice showed a single band at 219 bp. The mice used in all experiments were either WT or homozygous for APP/PS-1 mutation.

Immunocytochemistry for Aβ

To determine the deposition of Aβ in APP/PS-1 mice, one brain hemisphere from 3-, 6-, 9-, 12-, and 14-month-old mice was fixed in 4% formaldehyde, processed in the standard manner, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 10-μm thickness. The sections were deparaffinized, hydrated, and immersed in 88% formic acid for 3 minutes and washed in distilled water. After blocking with 15% filtered horse serum in automation buffer (Biomeda Corp., Foster City, CA) for 1 hour at room temperature, the sections were immunostained with 10D-5 monoclonal antibody (1:100) (NCL-B-amyloid) and a biotinylated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The sections were developed using an ABC reagent kit (Vector Laboratories) and counterstained with hematoxylin.

Tissue Preparation for Aβ Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Cerebral cortices were serially extracted with Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.4, followed by RIPA buffer [0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 1% Nonidet P-40, and 5 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid in Tris-buffered saline] and finally in 70% formic acid. Protease inhibitor cocktail (pepstatin A, leupeptin, TPCK, TLCK, soybean trypsin inhibitor, 1 μg/ml of each in 5 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) was added during Tris-buffered saline and RIPA extraction. To measure the levels of Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42, the supernatant obtained from the SDS extraction step was analyzed by ELISA.

Sandwich ELISA to Determine the Levels of Insoluble Brain Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42

The sandwich ELISA used here was performed as described previously,23–25 and the absorbencies falling within the standard curve for each assay were converted to pmol. The sandwich ELISA consisted of a capture monoclonal antibody (mAb, BAN50) that was specific for the first 10 amino acids in Aβ and was used in conjunction with one of two different detection antibodies, BA27 mAb specific for Aβ species ending at amino acid 40 or BC05 mAb specific for Aβ species ending at position 42(43). This ELISA had a detection limit of 3 to 6 fmol/well for Aβ1-40 and 1-42/43. The mAbs BAN50, BA27, and BC05 were prepared as described previously, and each ELISA result was normalized for the dilution and tissue weight (pmol/μg wet tissue).

Mitochondrial Isolation

Mice were euthanized; brains (excluding cerebellum) of three mice from each age group were pooled, homogenized in 5 ml of ice-cold mitochondrial isolation buffer containing 0.225 mol/L d-mannitol, 0.075 mol/L sucrose, 20 mmol/L HEPES, 1 mmol/L EGTA, and 1% bovine serum albumin, pH 7.2, in a Dounce homogenizer with a glass pestle. The homogenized brains were then diluted with isolation buffer to a final volume of 10 ml, centrifuged at 1500 × g for 5 minutes. The supernatant was kept on ice, and the pellet resuspended in 3 ml of isolation buffer, homogenized, and centrifuged at 1500 × g for 5 minutes. The supernatants were combined and centrifuged at 13,500 × g for 10 minutes. The brown mitochondrial pellets were resuspended in 100 μl of isolation buffer and kept on ice, and the protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay.

Measurement of Mitochondrial Respiration

Mitochondrial proteins were resuspended in buffer containing 0.25 mol/L sucrose, 50 mmol/L HEPES, 2 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 mmol/L EGTA, 10 mmol/L KH2PO4, and 0.5% bovine serum albumin, pH 7.4. Oxygen consumption was measured using a Clark-type electrode oxygraph (Hansatech Inc., Norfolk, UK) with 10 mmol/L pyruvate and 5 mmol/L malate as substrate in the absence of exogenous ADP (state 2 respiration) and after addition of 300 mmol/L ADP (state 3 respiration). The ATPase inhibitor oligomycin (100 μg/ml) was then added to inhibit mitochondrial respiration. In normally coupled mitochondria, the addition of oligomycin slows respiration to a rate similar to that of state 2, whereas in uncoupled mitochondria oligomycin inhibition is reduced. Respiratory control ratio (RCR) was calculated as the ratios between state 3 and state 2 respirations.

Immunoprecipitation

Isolated mitochondrial protein (200 μg) was resuspended in 200 μl of RIPA buffer (9.1 mmol/L Na2HPO4, 1.7 mmol/L NaH2PO4, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% v/v Nonidet P-40, and 0.1% SDS, pH 7.2). Polyclonal nitrotyrosine antibody (anti-rabbit, 2 μg/ml; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) was added and incubated overnight at 4°C. Protein A/G agarose (20 μl) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was added to the mixture and incubated overnight. Immunocomplexes were collected by centrifugation at 1000 × g for 5 minutes at 4°C, followed by washing with RIPA buffer, four times. Immunoprecipitated samples were recovered by resuspending in 2× sample loading buffer, immediately fractionated by reducing SDS/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), and analyzed by Western blot.

Western Blot Analysis

Equal amounts of brain homogenated proteins were resuspended in 2× sample loading buffer and separated on 12.5% SDS-PAGE. After separation by SDS/PAGE proteins were transferred electrophoretically to nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schuell, Dassell, Germany) and blocked with 5% nonfat dried milk in 50 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.9, 150 mmol/L NaCl, and 0.05% (v/v) Tween-20. After blocking, the blots were incubated overnight at 4°C with appropriate primary antibody (rabbit, anti-MnSOD IgG, dilution 1:10,000; Upstate Technology, Lake Placid, NY), followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Probed membranes were washed three times, and immunoreactive proteins were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Corp., Piscataway, NJ).

MnSOD Activity Assay

SOD activity in the homogenized brain sample was measured by the nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT)-bathocuproine sulfonate reduction inhibition method.26 This is an assay based on the competition reaction between SOD and the indicator molecule NBT. When increasing amounts of protein (containing SOD activity) were added to the system, the rate of NBT reduction was progressively inhibited. Potassium cyanide at 5 mmol/L was used to inhibit Cu/ZnSOD and thus measured only MnSOD activity. The assay mixture also contained catalase to remove H2O2 and diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid to chelate metal ions capable of redox cycling and interfering with the assay system. One unit of SOD activity was defined as the amount of SOD protein that caused a 50% reduction in the background rate of NBT reduction.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was analyzed by two-way analysis of variance, followed by Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test when applicable. The experiments were repeated at least three times, and the graphs were drawn using Graph Pad Prism, version 3.02.

Results

Aβ Deposition in APP/PS-1 Mice

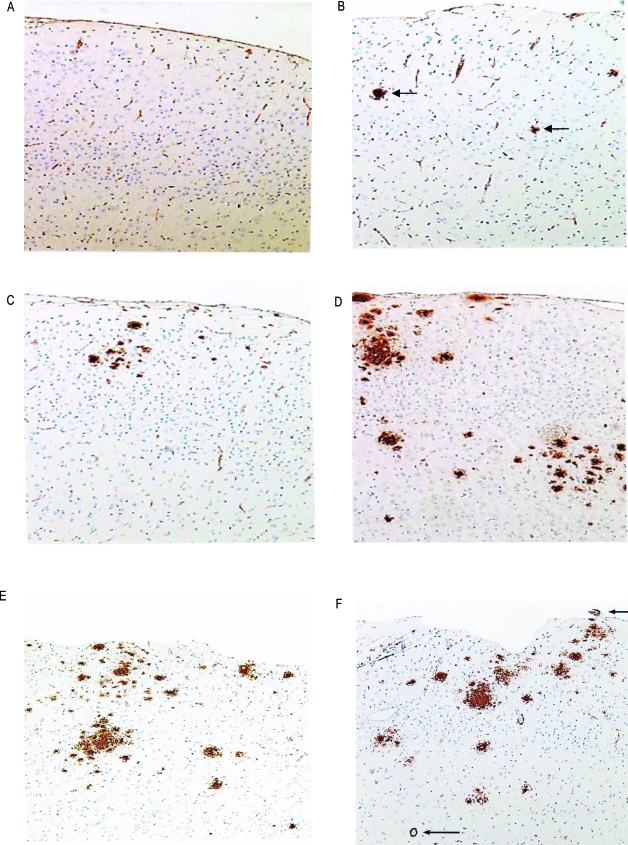

To determine the deposition of Aβ, we examined brain sections that were immunostained with 10D-5 antibody (Figure 1). The brains from WT mice contained no plaques at any age. The APP/PS-1 animals showed no deposition of Aβ at the age of 3 months (Figure 1A). At the age of 6 months (Figure 1B), a few microscopic, scattered, small Aβ plaques were found in the frontal cortex. By 9 months (Figure 1C) there were a few larger Aβ plaques and more scattered smaller Aβ deposits. By 12 months (Figure 1D), Aβ deposition was more prominent in the neocortex and spread of plaques to the hippocampus occurred, with many larger confluent Aβ plaques and many small and moderate size plaques. By 14 months, there were larger numbers of Aβ deposits and Aβ in small blood vessel walls in brain and leptomeninges. These results suggest that there was an age-related, regional dependence to Aβ deposition in APP/PS-1 mice.

Figure 1.

Sections of frontal cortex from APP/PS-1 mice immunostained with 10D-5 antibody for Aβ. A: Three-month-old animal showing no amyloid immunostaining in cortex. B: Six-month-old mouse showing rare small deposits of Aβ (arrows). C: Nine-month-old mouse showing increased Aβ deposits. D: Twelve-month-old mouse demonstrating numerous variable size deposits of Aβ. E: Fourteen-month-old mouse showing numerous diffuse Aβ deposits in cortex. F: Fourteen-month-old mouse demonstrating many Aβ deposits in cortex in parenchymal and leptomeningeal vessels (arrows). Original magnifications, ×100.

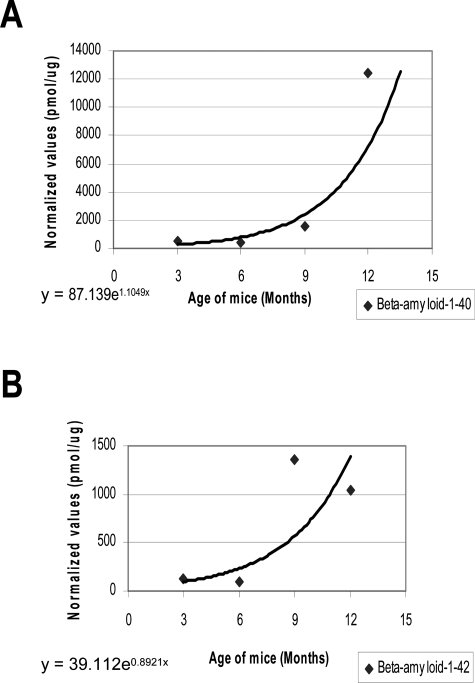

Increased Levels of Aβ1-40 and 1-42 Fractions in APP/PS-1 Mice

The accumulation of diverse species of Aβ peptides in amyloid plaques is a multistep process including the conversion of soluble Aβ into insoluble derivatives that assemble into amyloid fibrils and aggregate in extracellular deposits.16 We examined whether the APP/PS-1 mice model showed an increase in levels of SDS-soluble fractions of Aβ1-40 and 1-42 in cerebral cortical tissue. APP/PS-1 mice exhibited a trend of age-related increase in the load of both species of Aβ (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Levels of Aβ1-40 and 1-42 in APP/PS-1 mice. Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 levels were measured by ELISA from different groups (n = 5 per group) as described in the Materials and Methods section. Both species of Aβ showed an increasing trend in the levels associated with age (R2 = 0.8072 for Aβ1-40 and R2 = 0.702 for Aβ1-42).

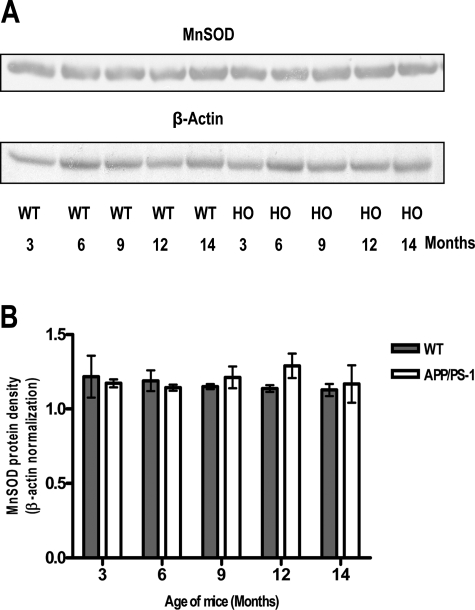

Unchanged MnSOD Protein Levels in WT and APP/PS-1 Mice

Expression of MnSOD is highly inducible by oxidative stress-inducing agents. To determine whether increases in Aβ produced increases in MnSOD enzyme levels, Western blot analyses of brain homogenate from animals of different ages of both WT and APP/PS-1 mutant mice were performed. The protein levels of MnSOD did not change when compared between genotypes or between different ages within a genotype (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Representative (out of three) immunoblot (A) and densitometry analysis (B) showing the levels of MnSOD. Protein (30 μg) extracted from brain specimens of APP/PS-1 knock-in and WT mice were run on 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Protein levels of MnSOD did not show significant age- and genotype-associated alterations. β-Actin was used to normalize protein loading. HO, APP/PS-1.

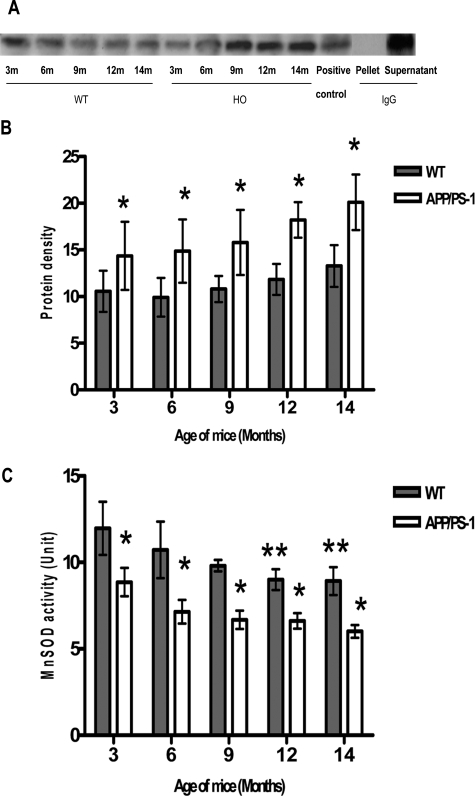

Increased Nitration of MnSOD in APP/PS-1 Mice

MnSOD is susceptible to peroxynitrite-induced inactivation.27 To determine whether Aβ-induced oxidative stress was associated with nitration and inactivation of MnSOD, nitration of MnSOD was detected by Western blot analysis of SDS/PAGE-fractionated mitochondrial proteins, which had been immunoprecipitated using a polyclonal anti-nitrotyrosine antibody. Immunodetection with polyclonal anti-MnSOD demonstrated detectable levels of nitrotyrosine in WT mice at all ages tested. In contrast, the APP/PS-1 mice showed an increasing trend in the level of immunoreactive-nitrated MnSOD (Figure 4A), but the increase was not statistically significant at P < 0.05. The increase was significant when compared between the two genotypes (P < 0.01).

Figure 4.

Immunoprecipitation of nitrotyrosine with MnSOD. Isolated mitochondrial protein (200 μg) was precipitated with polyclonal nitrotyrosine antibody and analyzed by Western blotting using MnSOD antibody. A: Nitrotyrosine co-immunoprecipitated with MnSOD showed that MnSOD is nitrated. HO, APP/PS-1; positive control, brain homogenate + peroxynitrite (2 μmol/L), provided by Dr. Timothy R. Miller, Graduate Center for Toxicology, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY; pellet, pellet of the isolated mitochondrial protein (200 μg) precipitated with preimmune IgG, analyzed by Western blotting using MnSOD antibody; supernatant of the isolated mitochondrial protein (200 μg) precipitated with preimmune serum, analyzed by Western blotting using MnSOD antibody. B: Densitometric analysis and subsequent statistical analysis by two-way analysis of variance showed significant differences (*P < 0.01) when compared between genotypes. C: MnSOD activity in the brain specimen was measured by the NBT-bathocuproine sulfonate reduction inhibition method.26 Statistical analysis by two-way analysis of variance showed significant age- and genotype-dependent decreases (P < 0.0001) in activity of MnSOD. APP/PS-1 mice, at all ages, showed significant decreases (*P < 0.05) in MnSOD activity when compared with age-matched WT mice. WT mice at 12 and 14 months showed significant decrease (**P < 0.05) in MnSOD activity when compared with 3-month-old WT mice. Immunoprecipitation and MnSOD activity was performed in three sets of animals.

Decreased SOD Activity in APP/PS-1 Mice

MnSOD catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide to hydrogen peroxide and molecular oxygen, and this conversion was used to estimate the activity of MnSOD. The activity of MnSOD in APP/PS-1 mice was significantly decreased (P < 0.0001) when compared to the WT mice. WT mice showed a significant (**P < 0.05) decrease in MnSOD activity at 12 and 14 months when compared to 3-month-old mice of their own genotype (Figure 4C). There was also a significant decrease (*P < 0.05) in activity of MnSOD in APP/PS-1 mice when compared to their age-matched WT controls (Figure 4C).

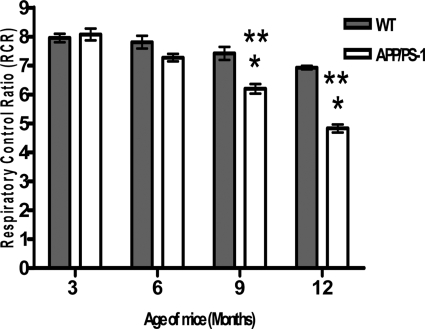

Decreased Mitochondrial Respiration in APP/PS-1 Mice

MnSOD is a primary antioxidant enzyme protecting mitochondria from oxidative injury. To determine whether a reduction of MnSOD activity would affect mitochondrial respiratory function, oxygen consumption by isolated mitochondria was measured as an indicator of the mitochondrial respiration activity. Pyruvate and malate were used as substrates to determine the function of brain mitochondria from WT and APP/PS-1 mice via complex I respiration. The results showed that the RCR of mitochondria was significantly (*P < 0.01) decreased in 9- and 12-month-old APP/PS-1 mice when compared to age-matched WT mice and also when compared to 3-month-old mice of both genotypes (**P < 0.001) (Figure 5). The results suggest that in APP/PS-1 mice there is inhibition of NAD-linked state 3 respiration rate, which is mediated through complex 1 of the mitochondrial electron transport chain. WT mice showed a small decrease in mitochondrial respiration with age; however, it was not statistically significant.

Figure 5.

Decline in mitochondrial respiration via complex I in APP/PS-1 mice. Oxygen consumption was measured using a Clark-type electrode oxygraph. RCR was calculated as the ratios between state 3 and state 2 respirations. APP/PS-1 mice at 9 and 12 months of age showed a significant decrease (*P < 0.01) in mitochondrial respiration when compared to its age-matched WT mice and a significant decrease (**P < 0.001) compared to 3-month-old mice of both genotypes. Statistical analysis: two-way analysis of variance followed by Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons test.

Discussion

Numerous reports have described attempts to recapitulate the hallmark pathologies of AD in the rodent brain by overexpression of human APP or APP fragments in transgenic models;16,28,29 examples include, Tg2576 mice that overexpress human APP69530 with Swedish FAD mutations, mice obtained by crossing Tg2576 mice and transgenic PS1-P264L mice,20,31 and the crosses of other Swedish APP transgenic mice with transgenic FAD mutant PS-1 mice.19,32 In this study, we used a double gene-targeted APPNLh/NLh/PS-1P264L/P264L mouse model for amyloid deposition without the overexpression of APP.33

Humanization of the mouse Aβ gene sequence results in an approximate threefold increase in amyloidogenic processing of recombinant APP in rat hippocampal neurons infected with Semliki Forest virus expression constructs,34 and single mutant PS-1 allele was sufficient to elevate the concentration of Aβ42 in brain and speed the onset of amyloid deposition and reactive astrogliosis.22 Our results using mice homozygous for APP/PS-1, which completely lack WT APP or PS-1 and expressed both mutant FAD APP and PS-1 at natural levels, showed age-dependent increases in amyloid pathology (Figure 2) in accordance with the results obtained from APP 695SWE transgenic mice having PS-1 P264L knock-in mutation.22,33 The observed accelerated Aβ deposition in APP/PS-1 mice also seems to have region dependence in relation to age, with deposition seen first in frontal cortex and later encompassing other cortical regions and hippocampus. Thus, this humanized mouse model should serve as a useful model to study the Aβ-induced pathology in human AD.

Measurement of Aβ1-40 and 1-42 showed that there was an increasing trend in both species in APP/PS-1 mice. Our findings are in concordance with that of Wang and colleagues17 who demonstrated an increase in average levels of Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 in AD. Our finding of increased quantity of Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42, is consistent with the possibility that Aβ1-42 serves as the initial seeding event for plaque formation and that increased levels of Aβ1-40 play a role in growing plaques and may be mechanistically linked to the onset and progression of AD.17

The AD brain is under pronounced oxidative stress, as manifested by protein oxidation, lipid peroxidation, DNA and RNA oxidation, widespread peroxynitrite-induced damage, advanced glycation end products, and altered antioxidant enzyme expression. Via mechanisms that are inhibited by antioxidants such as vitamin E, Aβ causes brain cell protein oxidation, lipid peroxidation, and ROS formation, among other oxidative stress responses, suggesting that this peptide is a source of oxidative stress in the brain.35 Other sources of oxidative stress in AD are likely, ranging from altered mitochondrial function, trace metal ion imbalances to binding of altered metal ion to biomolecules.36 Our results indicating increased nitration of MnSOD protein signify an increase in oxidative stress in the brain of the APP/PS-1 mice and suggest a compromise in mitochondrial function of APP/PS-1 mice attributable to increased oxidative stress.

The mitochondrion, a major subcellular source of ROS37,38 plays a pivotal role in apoptosis.39 However, the mitochondrion is also a site of cellular protection against ROS that involves an elaborate antioxidant defense system, especially MnSOD. Our studies indicate that the expression pattern of MnSOD in APP/PS-1 mice remained unaltered in all age groups, but SOD activity in APP/PS-1 mice was significantly reduced when compared to age-matched WT mice, suggesting that the protein was inactivated. Our finding is in accordance with that reported by Macmillan-Crow and colleagues27 in a chronic rejecting renal model. The decreased activity of MnSOD is attributable to nitration of tyrosine residues5,40 that occurs on the MnSOD protein. Tyrosine nitration (3-nitrotyrosine, 3-NT) is an in vivo posttranslational protein modification with potentially significant biological implications14,41 and has been detected in a number of human and animal models of disease.39 3-NT is increased in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex of aged rats,42 the cerebrospinal fluid of aged humans,43 and the subcortical white matter of aged monkeys.44 3-NT formation is the hallmark of reactive peroxynitrite (ONOO−), and this modification can compromise the functional and/or structural integrity of target proteins,40 especially MnSOD.45 After diffusing into mitochondria, .NO can inhibit oxygen consumption by complex IV. Inhibition by .NO is reversible; however, this process decreases electron transport and could potentially increase the concentration of O2−..27 MnSOD has a function to eliminate O2−. from the mitochondrial matrix space. But, the concentration of .NO required to inhibit complex IV is sufficient to compete effectively with MnSOD for O2−. by a rapid reaction generating peroxynitrite, which can nitrate tyrosine residues and inactivate MnSOD to increase further the intramitochondrial level of O2−..27 O2−. reacts with .NO faster than with MnSOD46; therefore, if mitochondria contain inactive MnSOD, this peroxynitrite can further nitrate MnSOD and inactivate MnSOD to increase the intramitochondrial level of superoxide. Consequently this peroxynitrite-mediated amplification cycle would result in a progressive increase of mitochondrial levels of peroxynitrite, which can induce additional cytotoxic effects27 including inactivation of complexes I and II in the mitochondrial respiratory chain.47

Myeloperoxidase (MPO), one of the principle hemoproteins stored in the azurophilic granules of neutrophils and monocytes, is also a catalyst of nitrotyrosine formation via nitrite oxidation to the potent nitrating species nitrogen dioxide (.NO2).48 It has been demonstrated in vascular tissues that MPO significantly contributes to nitrotyrosine formation in vivo.48,49 Further, it has been shown that MPO−/− animals have reduced nitrotyrosine immunoreactivity than WT mice.49 MPO is not only present in neutrophils and monocytes, but also in microglia. Microglia are quiescent in normal brain but can become activated in response to neuronal damage or various other stimuli, including aggregated Aβ.50,51 In AD, MPO has been shown to be co-localized around the Aβ plaques and also in microglia-macrophages that are present around the plaques. It has also been shown that Aβ treatment of the mouse microglia cell line BV-2 resulted in strong induction of MPO mRNA expression.52 From these observations and the fact that senile plaques are surrounded by activated microglia, it can be cautiously speculated that MPO may also contribute to the nitration of MnSOD.

Despite major advances in the study of nitration of proteins, the effect of nitration on protein turnover and the pathways that degrade the nitrated proteins have not been fully elucidated. There are reports about faster degradation of proteins treated with peroxynitrite or a generator of nitric oxide and superoxide by 20S proteasome.53 Consistent with this, Souza and colleagues54 reported that a single nitrating event is sufficient to target proteins for degradation by the proteasome. Although protein nitration is generally viewed as an irreversible event, activities that appear to specifically repair nitrated proteins have been reported in human and rat tissues.55,56 Thus it tempting to speculate that nitration of MnSOD may be reversible. In this regard, our APP/PS-1 mouse model is ideal for testing pharmacological intervention by mitochondrially targeted antioxidants such Mito-Q or Mito-Vit E.

Mito-Q [mixture of mitoquinol-10-(6′-ubiquinolyl)de-cytriphenylphosphonium and mitoquinone-10-(6′-ubiquinonyl)decyltriphenylphosphonium]57 and MitoVit E [2-[2-(triphenylphosphonio)ethyl]-3,4-dihydro-2,5,7,8-tetra-methyl-2H-1-benzopyran-6-ol bromide]58 have been found to destroy superoxide in the mitochondrial matrix.58 Mito-Q (Mito-Q10) has been shown to be an effective antioxidant against lipid peroxidation, peroxynitrite, and superoxide.59 Pretreatment with Mito-Q and Mito Vit-E have been shown to 1) significantly abrogate the lipid peroxide-induced 2′-7′-dichlorofluorescein fluorescence and protein oxidation in bovine aortic endothelial cells; 2) inhibit cytochrome c release, caspase-3 activation, and DNA fragmentation; 3) inhibit H2O2 and lipid peroxide-induced inactivation of complex I and aconitase, thus preventing the production of superoxide; 4) inhibit TfR overexpression and mitochondrial uptake of 55Fe, thereby inhibiting apoptosis; and 5) restore the mitochondrial membrane potential and proteasomal activity.60 Further, the pro-oxidant effect or superoxide production by Mito-Q10 was found to be insufficient to cause any damage but led to hydrogen peroxide production and nitric oxide consumption.59 Despite these results, the effect of these compounds on the reversal of damage that has already been caused by oxidative stress has not been investigated.

The antioxidant efficacy of Mito-Q10 is due to its conversion to ubiquinol by complex II of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, but its reoxidation back to ubiquinone by complex III is ineffective. In ubiquinol form, Mito-Q10 quenches ONOO− and becomes oxidized, which can be reduced by complex II to ubiquinol, making it available to quench more ONOO−.59 Mito-Q10 may be effective in preventing the nitration of MnSOD and may serve as an effective therapeutic intervention to slow the progression of AD.

Mitochondrial respiratory dysfunction and oxidative stress have been associated with many neurodegenerative diseases.61 Results obtained in this study on mitochondrial respiration using pyruvate plus malate as substrate demonstrate that in APP/PS-1 mice there is inhibition of NAD-linked state 3 respiration rate, which is mediated through complex 1 of the mitochondrial electron transport chain. RCR represents functional integrity of isolated mitochondria.62 A high value of RCR indicates the utilization of substrates is tightly coupled to the production of ATP.63 The respiration injury would predict a low coupling efficiency of the mitochondrial electron transport and an increased likelihood of electron leakage during respiration, leading to O2−. radical formation and increased oxidative stress. Our finding is consistent with that of Kokoszka and colleagues64 who reported a decrease in state III respiratory states and the RCR of liver mitochondria from both homozygous and heterozygous knock-out mice for the gene encoding the MnSOD protein, Sod2. Cardiac mitochondria from Sod2+/− mice, which have 50% reduction in MnSOD activity, showed altered mitochondrial function as exemplified by decreased respiration by complex I and an increase in the sensitivity of the permeability transition pore induction.65 Thus, mitochondria from the heart (Sod2+/−) and liver (Sod−/− and Sod2+/−) show evidence of increased oxidative damage compared with mitochondria isolated from Sod2+/+ mice. Yen and colleagues62 showed that MnSOD selectively protected state 3 respiration activity through complex I substrates and prevented complex I inactivation in heart mitochondria treated with the anthracyclin antibiotic, adriamycin. These results indicate that MnSOD plays a critical role in oxidative stress responses and in maintenance of mitochondrial respiration and the lack or reduced activity that leads to increased sensitivity of the animals to oxidative stress-induced mitochondrial damage. The decreased activity of MnSOD in APP/PS-1 mice can be implicated as a cause of decreased state 3 respiration rate seen in these mice. Our study, which shows a decline in mitochondrial respiration in aged (9 and 12 months) WT mice, also implicates the effects of mitochondrial ROS production in the process of aging. Our findings are consistent with studies that demonstrate a decline in respiratory function of mitochondria with age66–68 and decreased mitochondrial respiratory function in aged or aging mice, due to deficiencies in the MnSOD.64 Our results also suggest that nitrative inactivation of MnSOD may be, at least in part, responsible for the decline in the mitochondrial function of aging AD mice. Biochemical analyses of brain specimens from patients with AD have shown abnormalities in the components of electron transport chain, particularly in the activity of cytochrome oxidase (COX).69,70 Inhibition of COX could cause depressed ATP synthesis and bioenergetic impairment in AD. In addition, the decreased COX function could cause diversion of electrons from their normal pathway into reaction with molecular oxygen in the neocortex and hippocampus in AD, resulting in increased O2−..36 Superoxide can contribute to mitochondrial impairment by generating additional reactive species, particularly hydroxyl radical, and peroxynitrite that can inactivate mitochondrial proteins leading to further decline in mitochondrial respiration, decreased ATP production, and ultimately neuronal cell death.71

Although there is no consensus about the activity level of MnSOD in AD, there have been reports of reduction of SOD activity in AD frontal cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum72 and elevation of SOD activity in the caudate nucleus of AD.73 However, there are reports of increased nitrotyrosine immunoreactivity in neurons of AD.74,75 To our knowledge the identity of the nitrated proteins in the AD brain is not known. Our results showing decreased activity of MnSOD in relation to age and nitration represents the first study directed to the identification of nitrated proteins in AD brain.

The mouse model used in our study has the sequence of Aβ identical to the human sequence. Further, the mutations introduced are driven by endogenous promoters of APP and PS-1 genes, and expression is limited to the replacement of these two endogenous genes and not by the expression of multiple transgenes. The amyloid pathology observed in this model is similar to that found in AD. Thus, the results obtained from this model may prove useful in unraveling the pathogenesis of AD-induced oxidative stress.

In conclusion, in this study we demonstrate an increased and accelerated deposition of Aβ in APP/PS-1 mice, increased levels of Aβ1-40/1-42, increased nitrotyrosine and subsequent inactivation of MnSOD, and impaired mitochondrial respiration in APP/PS-1 mice in association with age. The increased levels of Aβ1-40/1-42, essential for aggregation and subsequent neurotoxic properties, are observed from 6 months on. It is tempting to speculate that the increased Aβ may be the cause of alterations seen in MnSOD and the associated decrease in mitochondrial function. These changes may lead to altered function of mitochondrial permeability transition pore,66 which increases the propensity to undergo apoptosis. This is important because findings indicate that neuronal cell death associated with Aβ peptide are apoptotic in nature.76 Thus, our studies which indicate mitochondrial dysfunction, an age-associated increase in nitration of MnSOD, and its concomitant decrease in antioxidant activity, may provide the missing link between Aβ-induced oxidative stress and progression of AD.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cephalon Inc. for providing the mice; Irina Doubinskaia for breeding and maintenance of the APP/PS-1 and appropriate WT control mice; Dr. Timothy R. Miller, Graduate Center for Toxicology, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, for providing peroxynitrite; and Dr. Dorothy Flood, Cephalon Inc. for the critical review and valuable suggestions that improved the quality of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Daret St. Clair, Graduate Center for Toxicology, 306 Health Sciences Research Bldg., Lexington, KY 40536-0305. E-mail: dstcl00@uky.edu.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant AG-05119).

M.A. and J.T. contributed equally to this work.

References

- Evans DA, Funkenstein HH, Albert MS, Scherr PA, Cook NR, Chown MJ, Hebert LE, Hennekens CH, Taylor JO. Prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in a community population of older people. JAMA. 1989;262:2551–2556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwatsubo T, Odaka A, Suzuki N, Mizusawa H, Nukina N, Ihara Y. Visualization of Aβ 42(43) and Aβ 40 in senile plaques with end-specific Aβ monoclonals: evidence that an initially deposited species is Aβ 42(43). Neuron. 1994;13:45–53. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90458-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ. Clearing the brain’s amyloid cobwebs. Neuron. 2001;25:177–180. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00475-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield DA, Lauderback CM. Lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation in Alzheimer’s disease brain: potential causes and consequences involving amyloid β-peptide-associated free radical oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32:1050–1060. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00794-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Richey Harris PL, Sayre LM, Beckman JS, Perry G. Widespread peroxynitrite-mediated damage in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2653–2657. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02653.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castegna A, Thongboonkerd V, Klein JB, Lynn B, Markesbery WR, Butterfield DA. Proteomic identification of nitrated proteins in Alzheimer’s disease brain. J Neurochem. 2003;85:1394–1401. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield DA, Griffin S, Munch G, Pasinetti GM. Amyloid β-peptide and amyloid pathology are central to the oxidative stress and inflammatory cascades under which Alzheimer’s disease brain exists. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2001;4:193–201. doi: 10.3233/jad-2002-4309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mecocci P, MacGarvey U, Beal MF. Oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA is increased in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1994;36:747–751. doi: 10.1002/ana.410360510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunomura A, Perry G, Pappolla MA, Wade R, Hirai K, Chiba S, Smith MA. RNA oxidation is a prominent feature of vulnerable neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1959–1964. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-01959.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebovitz RM, Zhang H, Vogel H, Cartwright J, Jr, Dionne L, Lu N, Huang S, Matzuk MM. Neurodegeneration, myocardial injury and perinatal death in mitochondrial superoxide dismutase deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9782–9787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Huang TT, Carlson EJ, Melov S, Ursell PC, Olson JL, Noble LJ, Yoshimura MP, Berger C, Chan PH. Dilated cardiomyopathy and neonatal lethality in mutant mice lacking manganese superoxide dismutase. Nat Genet. 1995;11:376–381. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei YH, Lee HC. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial DNA mutation, and impairment of antioxidant enzymes in aging. Exp Biol Med. 2002;227:671–682. doi: 10.1177/153537020222700901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman H, Halliwell B. Damage to DNA by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: role in inflammatory disease and progression to cancer. Biochem J. 1996;313:17–29. doi: 10.1042/bj3130017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman JS. Oxidative damage and tyrosine nitration from peroxynitrite. Chem Res Toxicol. 1996;9:836–844. doi: 10.1021/tx9501445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montine KS, Olson SJ, Amarnath V, Whetsell WO, Graham DG, Montine TJ. Immunohistochemical detection of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal adducts in Alzheimer’s disease is associated with inheritance of ApoE4. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:437–443. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Games D, Adams D, Alessandrini R, Barbour R, Borthelette P, Blackwell C, Carr T, Clemens J, Donaldson T, Gillespie F, Guido T, Hagopian S, Johnson-Wood K, Khan K, Lee M, Leibowitz P, Lieberburg I, Little S, Masliah E, McConlogue L, Montoya-Zavala M, Mucke L, Paganini L, Penniman E, Power M, Schenk D, Seubert P, Snyder B, Soriano F, Tan H, Vitale J, Wadsworth S, Wolozin B, Zhao J. Alzheimer-type neuropathology in transgenic mice overexpressing V717F beta-amyloid precursor protein. Nature. 1995;373:523–527. doi: 10.1038/373523a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Dickson DW, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. The levels of soluble versus insoluble brain Aβ distinguish Alzheimer’s disease from normal and pathologic aging. Exp Neurol. 1999;158:328–337. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia AY, Masliah E, McConlogue L, Yu GQ, Tatsuno G, Hu K, Kholodenko D, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA, Mucke L. Plaque-independent disruption of neural circuits in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3228–3233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchelt DR, Ratovitski T, van Lare J, Lee MK, Gonzales V, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Price DL, Sisodia SS. Accelerated amyloid deposition in the brains of transgenic mice coexpressing mutant presenilin 1 and amyloid precursor proteins. Neuron. 1997;19:939–945. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80974-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcomb L, Gordon MN, McGowan E, Yu X, Benkovic S, Jantzen P, Wright K, Saad I, Mueller R, Morgan D, Sanders S, Zehr C, O’Campo K, Hardy J, Prada CM, Eckman C, Younkin S, Hsiao K, Duff K. Accelerated Alzheimer-type phenotype in transgenic mice carrying both mutant amyloid precursor protein and presenilin 1 transgenes. Nat Med. 1998;4:97–100. doi: 10.1038/nm0198-097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reaume AG, Howland DS, Trusko SP, Savage MJ, Lang DM, Greenberg BD, Siman R, Scott RW. Enhanced amyloidogenic processing of the β-amyloid precursor protein in gene-targeted mice bearing the Swedish familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations and a “humanized” Aβ sequence. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23380–23388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siman R, Reaume AG, Savage MJ, Trusko S, Lin YG, Scott RW, Flood DG. Presenilin-1 P264L knock-in mutation: differential effects on Aβ production, amyloid deposition and neuronal vulnerability. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8717–8726. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08717.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skovronsky DM, Doms RW, Lee VM. Detection of novel, intraneuronal pool of insoluble Aβ that accumulates with time in culture. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1031–1039. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.4.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RS, Suzuki N, Chyung AS, Younkin SG, Lee VM. Amyloids β40 and β42 are generated intracellularly in cultured human neurons and their secretion increases with maturation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8966–8970. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki N, Cheung TT, Cai XD, Odaka A, Otvos L, Jr, Eckman C, Golde TE, Younkin SG. An increased percentage of long amyloid β-protein secreted by familial amyloid β-protein precursor (βAPP717) mutants. Science. 1994;264:1336–1340. doi: 10.1126/science.8191290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitz DR, Oberley LW. An assay for superoxide dismutase activity in mammalian tissue homogenates. Anal Biochem. 1989;179:8–18. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan-Crow LA, Crow JP, Kerby JD, Beckman JS, Thompson JA. Nitration and inactivation of manganese superoxide dismutase in chronic rejection of human renal allografts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11853–11858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb BT, Sisodia SS, Lawler AM, Slunt HH, Kitt CA, Kearns WG, Pearson PL, Price DL, Gearhart JD. Introduction and expression of the 400 kilobase amyloid precursor protein gene in transgenic mice. Nat Genet. 1993;5:22–30. doi: 10.1038/ng0993-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFerla FM, Tinkle BT, Bieberich CJ, Haudenschild CC, Jay G. The Alzheimer’s A beta peptide induces neurodegeneration and apoptotic cell death in transgenic mice. Nat Genet. 1995;9:21–30. doi: 10.1038/ng0195-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, Yang F, Cole G. Correlative memory deficits, Aβ elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan E, Sanders S, Iwatsubo T, Takeuchi A, Saido T, Zehr C, Yu X, Uljon S, Wang R, Mann D, Dickson D, Duff K. Amyloid phenotype characterization of transgenic mice overexpressing both mutant amyloid precursor protein and mutant presenilin 1 transgenes. Neurobiol Dis. 1999;6:231–244. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1999.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb BT, Bardel KA, Kulnane LS, Anderson JJ, Holtz G, Wagner SL, Sisodia SS, Hoeger EJ. Amyloid production and deposition in mutant amyloid precursor protein and presenilin-1 yeast artificial chromosome transgenic mice. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:695–697. doi: 10.1038/11154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood DG, Reaume AG, Dorfman KS, Lin TG, Lang DM, Trusko SP, Savage MJ, Annaert WG, Strooper BD, Siman R, Scott RW. FAD mutant PS-1 gene-targeted mice: increased Aβ42 and Aβ deposition without APP overproduction. Neurobiol Aging. 2002;23:335–348. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00330-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeStrooper B, Simons M, Multhaup G, Leuven FV, Beyreuther K, Dotti CG. Production of intracellular amyloid-containing fragments in hippocampal neurons expressing human amyloid precursor protein and protection against amyloidogenesis by subtle amino acid substitutions in the rodent sequence. EMBO J. 1995;14:4932–4938. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00176.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield DA, Howard BJ, LaFontaine MA. Brain oxidative stress in animal models of accelerated aging and the age-related neurodegenerative disorders, Alzheimer’s disease and Huntington’s disease. Curr Med Chem. 2001;8:815–828. doi: 10.2174/0929867013373048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markesbery WR. Oxidative stress hypothesis in Alzheimer’s disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997;23:134–147. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00629-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugan LL, Sensi SL, Canzoniero LM, Handran SD, Rothman SM, Goldberg MP, Choi DW. Mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species in cortical neurons following exposure to N-methyl-d-aspartate. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6377–6388. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06377.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piantadosi CA, Zhang J. Mitochondrial generation of reactive oxygen species after brain ischemia in the rat. Stroke. 1996;27:327–331. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer G, Zamzami N, Susin SA. Mitochondrial control of apoptosis. Immunol Today. 1997;18:44–51. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)80014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Perry G, Richey PL, Sayre LM, Anderson VE, Beal MF, Kowall N. Oxidative damage in Alzheimer’s. Nature. 1996;382:120–121. doi: 10.1038/382120b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ischiropoulos H. Biological tyrosine nitration: a pathophysiological function of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;356:1–11. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin CM, Chung YH, Kim MJ, Lee EY, Kim EG, Cha CI. Age related changes in the distribution of nitrotyrosine in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus of rats. Brain Res. 2002;931:194–199. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03391-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohgi H, Abe T, Yamazaki K, Murata T, Ishizaki E, Isobe C. Alterations of 3-nitrotyrosine concentration in the cerebrospinal fluid during aging and in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 1999;269:52–54. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00406-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloane JA, Hollander W, Moss MB, Rosene DL, Abraham CR. Increased microglial activation and protein nitration in white matter of the aging monkey. Neurobiol Aging. 1999;20:395–405. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(99)00066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ischiropoulos H, Zhu L, Chen J, Tasi M, Martin JC, Smith CD, Beckman JS. Peroxynitrite-mediated tyrosine nitration catalyzed by superoxide dismutase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;298:431–437. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90431-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu JL, Hsieh Y, Tu C, O’Connor D, Nick HS, Silverman DN. Catalytic properties of human manganese superoxide dismutase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17687–17691. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassina A, Radi R. Differential inhibitory action of nitric oxide and peroxynitrite on mitochondrial electron transport. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;328:309–316. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldus S, Eiserich JP, Mani A, Castro L, Figueroa M, Chumley P, Ma W, Tousson A, White CR, Bullard DC, Brennan ML, Lusis AJ, Moore KP, Freeman BA. Endothelial transcytosis of myeloperoxidase confers specificity to vascular ECM proteins as targets of tyrosine nitration. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1759–1770. doi: 10.1172/JCI12617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldus S, Eiserich JP, Brennan ML, Jackson RM, Alexander CB, Freeman BA. Spatial mapping of pulmonary and vascular nitrotyrosine reveals the pivotal role of myeloperoxidase as a catalyst for tyrosine nitration in inflammatory diseases. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:1010–1019. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00993-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Khoury J, Hickman SE, Thomas CA, Loike JD, Silverstein SC. Microglia, scavenger receptors, and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1998;19:S81–S84. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(98)00036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meda L, Cassatella MA, Szendrei GI, Otvos L, Jr, Baron P, Villalba M, Ferrari D, Rossi F. Activation of microglial cells by beta-amyloid protein and interferon-gamma. Nature. 1995;374:647–650. doi: 10.1038/374647a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WF, Rhees J, Maciejewski D, Paladino T, Sieburg H, Maki RA, Masliah E. Myeloperoxidase polymorphism is associated with gender specific risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Neurol. 1999;155:31–41. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grune T, Blasig IE, Sitte N, Roloff B, Haseloff R, Davies KJ. Peroxynitrite increases the degradation of aconitase and other cellular proteins by proteasome. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10857–10862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.10857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza JM, Choi I, Chen Q, Weisse M, Daikhin E, Yudkoff M, Obin M, Ara J, Horwitz J, Ischiropoulos H. Proteolytic degradation of tyrosine nitrated proteins. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;380:360–366. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gow AJ, Duran D, Malcolm S, Ischiropoulos H. Effects of peroxynitrite-induced protein modifications on tyrosine phosphorylation and degradation. FEBS Lett. 1996;385:63–66. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00347-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamisaki Y, Wada K, Bian K, Balabanli B, Davis K, Martin E, Behbod F, Lee YC, Murad F. An activity in rat tissues that modifies nitrotyrosine-containing proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11584–11589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelso GF, Porteous CM, Coulter CV, Hughes G, Porteous WK, Ledgerwood EC, Smith RA, Murphy MP. Selective targeting of a redox-active ubiquinone to mitochondria within cells: antioxidant and antiapoptotic properties. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:4588–4596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009093200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echtay KS, Murphy MP, Smith RA, Talbot DA, Brand MD. Superoxide activates mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 from matrix side. Studies using targeted antioxidants. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:47129–47135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208262200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James AM, Cocheme HM, Smith RA, Murphy MP. Interactions of mitochondria-targeted and untargeted ubiquinones with the mitochondrial respiratory chain and reactive oxygen species. Implications for the use of exogenous ubiquinones as therapies and experimental tools. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21295–21312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanasekaran A, Kotamraju S, Kalivendi SV, Matsunaga T, Shang T, Keszler A, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B. Supplementation of endothelial cells with mitochondria-targeted antioxidants inhibit peroxide-induced mitochondrial iron uptake, oxidative damage, and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:37575–37587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404003200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal MF. Aging, energy and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:357–366. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen HC, Oberley TD, Oberley C, Gairola CG, Szweda LI, St. Clair DK. Manganese superoxide dismutase protects mitochondrial complex I against adriamycin-induced cardiomyopathy in transgenic mice. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;362:59–66. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews CK, van Holde KE. Redwood City: Benjamin/Cummings,; Biochemistry. 1990 [Google Scholar]

- Kokoszka JE, Coskun P, Esposito LA, Wallace DC. Increased mitochondrial oxidative stress in the Sod2 (+/−) mouse results in the age-related decline of mitochondrial function culminating in increased apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2278–2283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051627098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Remmen H, Williams MD, Guo Z, Estlack L, Yang H, Carlson EJ, Epstein CJ, Huang TT, Richardson A. Knockout mice heterozygous for Sod2 show alterations in cardiac mitochondrial function and apoptosis. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:H1422–H1432. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.3.H1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen TC, Chen YS, King KL, Yeh SH, Wei YH. Liver mitochondrial respiratory functions decline with age. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;165:994–1003. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92701-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JM, Mann VM, Schapira AH. Analyses of mitochondrial respiratory chain function and mitochondrial DNA deletion in human skeletal muscle: effect of ageing. J Neurol Sci. 1992;113:91–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(92)90270-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei YH. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial DNA mutations in human aging. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1998;217:53–63. doi: 10.3181/00379727-217-44205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer I, Zierz S, Moller HJ. A selective defect of cytochrome C oxidase is present in brain of Alzheimer disease patients. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:455–462. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kish SJ, Mastrogiacomo F, Guttman M, Furukawa Y, Taanman JW, Dozic S, Pandolfo M, Lamarche J, DiStefano L, Chang LJ. Decreased brain protein levels of cytochrome oxidase subunits in Alzheimer’s disease and in hereditary spinocerebellar ataxia disorders: a nonspecific change? J Neurochem. 1999;72:700–707. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert A, Keil U, Marques CA, Bonert A, Frey C, Schussel K, Muller WE. Mitochondrial dysfunction, apoptotic cell death, and Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:1627–1634. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00534-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JS. Free radicals in the genesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1993;695:73–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb23031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marklund SL, Adolfsson R, Gottfries CG, Windblad B. Superoxide dismutase isoenzymes in normal brains and in brains from patients with dementia of Alzheimer type. J Neurol Sci. 1985;67:319–325. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(85)90156-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good PF, Werner P, Hsu A, Olanow CW, Perl DP. Evidence of neuronal oxidative damage in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 1996;149:21–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodovotz Y, Lucia MS, Flanders KC, Chesler L, Xie QW, Smith TW, Weidner J, Mumford R, Webber R, Nathan C, Roberts AB, Lippa CF, Sporn MB. Inducible nitric oxide synthase in tangle-bearing neurons of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1425–1433. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson DW. Apoptotic mechanisms in Alzheimer neurofibrillary degeneration: cause or effect? J Clin Invest. 2004;114:23–27. doi: 10.1172/JCI22317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]