Abstract

DIDS (4,4′-di-isothiocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulfonate), an anion channel blocker, triggers Ca2+ release from skeletal muscle SR (sarcoplasmic reticulum). The present study characterized the effects of DIDS on rabbit skeletal single Ca2+-release channel/RyR1 (ryanodine receptor type 1) incorporated into a planar lipid bilayer. When junctional SR vesicles were used for channel incorporation (native RyR1), DIDS increased the mean Po (open probability) of RyR1 without affecting unitary conductance when Cs+ was used as the charge carrier. Lifetime analysis of single RyR1 activities showed that 10 μM DIDS induced reversible long-lived open events (Po=0.451±0.038) in the presence of 10 μM Ca2+, due mainly to a new third component for both open and closed time constants. However, when purified RyR1 was examined in the same condition, 10 μM DIDS became considerably less potent (Po=0.206±0.025), although the caffeine response was similar between native and purified RyR1. Hence we postulated that a DIDS-binding protein, essential for the DIDS sensitivity of RyR1, was lost during RyR1 purification. DIDS-affinity column chromatography of solubilized junctional SR, and MALDI–TOF (matrix-assisted laser-desorption ionization–time-of-flight) MS analysis of the affinity-column-associated proteins, identified four major DIDS-binding proteins in the SR fraction. Among them, aldolase was the only protein that greatly potentiated DIDS sensitivity. The association between RyR1 and aldolase was further confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation and aldolase-affinity batch-column chromatography. Taken together, we conclude that aldolase is physically associated with RyR1 and could confer a considerable potentiation of the DIDS effect on RyR1.

Keywords: Ca2+-release channel, disulfonic stilbene derivative, excitation–contraction coupling, ryanodine receptor (RyR), skeletal muscle

Abbreviations: 1D and 2D, one and two dimensional; DIDS, 4,4′-di-isothiocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulfonate; EC, excitation–contraction; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; HSR, heavy fraction of fragmented sarcoplasmic reticulum; IPG, immobilized pH gradient; MALDI–TOF, matrix-assisted laser-desorption ionization–time-of-flight; PEG, poly(ethylene glycol); Po, open probability; RyR, ryanodine receptor; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum

INTRODUCTION

The RyR (ryanodine receptor) in striated muscle is a high-conductance Ca2+-release channel located in the terminal cisternae of the SR (sarcoplasmic reticulum) [1–5]. In skeletal muscle EC (excitation–contraction) coupling, membrane depolarization induces activation of the dihydropyridine receptor/voltage sensor, and the subsequent conformational change of RyR1 leads to an opening of RyR1, the release of Ca2+ from the SR and hence muscle contraction. In cardiac-type EC coupling, depolarization-induced Ca2+ influx through the dihydropyridine receptor/L-type Ca2+ channel induces Ca2+ release from the SR through RyR2 and, in turn, muscle contraction. The third RyR isoform, RyR3 is more ubiquitously expressed at a much lower level than the other two isoforms, and exists in a wide range of cells, such as Jurkat T-cells, parotid acinar cells, the central nervous system and neonatal and adult skeletal muscle [6].

Disulfonic stilbene derivatives have been extensively used as pharmacological probes to study the kinetics and molecular structures of membrane transporters. For example, the transport kinetics and structure of the SR Ca2+-ATPase [7] have been examined using disulfonic stilbene derivatives. In striated muscle cells, one of the disulfonic stilbene derivatives, DIDS (4,4′-di-iso-thiocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulfonate), has been widely used to study the roles and mechanisms of various ion transport in the sarcolemma and the internal organelles. Kawasaki and Kasai [8] first found that disulfonic stilbene derivatives could activate RyR1 in rabbit skeletal SR vesicles, as well as in an artificial lipid bilayer membrane. It was observed that DIDS locked RyR1 in an open state when Ba2+ was used as a charge carrier [8]. Zahradnikova and Zahradnik [9] observed irreversible DIDS activation of RyR2 from dog heart, with no change in single-channel conductance, leading to the proposal of a covalent modification of an amino group residing in the gating structure of the channel by DIDS. Irreversible modification by DIDS was also found in sheep cardiac RyR2 [10,11]. Experiments using skeletal RyR1 showed that activation of RyR1 by DIDS could be either reversible or irreversible, depending on the experimental conditions, e.g. the concentration and incubation time of DIDS and cytosolic Ca2+ concentration [12]. Studies on frog muscle revealed that the Po (open probability) was augmented by DIDS at 5–200 μM by inducing a long-lived open state [13].

The effects of DIDS on RyRs make this compound a potentially useful probe to elucidate the mechanism of RyR function. Two studies have already used this compound to probe its interaction with the RyR1 and two RyR1-associated proteins, calmodulin [14] and a 30 kDa protein [15–18]. The 30 kDa protein was identified as a calsequestrin-binding protein in rabbit skeletal SR and was postulated to be a receptor for DIDS, implying that DIDS is bound to RyR1 via the 30 kDa protein in rabbit skeletal muscle [17]. On the other hand, the direct DIDS binding to RyR and covalent modification of RyR by DIDS have been postulated to be the underlying molecular mechanisms for DIDS activation of RyRs [9–12].

The increasing number of RyR activation mechanisms by DIDS in the literature gave rise to the necessity for a systematic approach to identify the DIDS receptor that confers DIDS sensitivity to RyR. In the present study, we employed both functional and biochemical tools in an effort to identify the molecular machinery responsible for the activation of RyR1 by DIDS. We report here the novel finding that the glycolytic enzyme aldolase is bound to RyR1 and is responsible for the reversible activation of RyR1 by DIDS.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Mouse anti-RyR1 antibody (1:5000) was obtained from Affinity BioReagent (Golden, CO, U.S.A.). The horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:5000) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, U.S.A.). The goat anti-aldolase antibody was obtained from Chemicon (Temecular, CA, U.S.A.). Chemiluminescent reagents for immunoblot analysis were obtained from Pierce (Rockford, IL, U.S.A.). DIDS, protease inhibitors, aldolase [≥80% (w/w) purity], GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) [85% (w/w) purity], malate dehydrogenase [99% (w/v) purity] and adenylate kinase [99% (w/v) purity] were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). [3H]Ryanodine, CNBr-Sepharose 4B and Protein G–Sepharose 4 Fast Flow affinity beads were obtained from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ, U.S.A.). Phospholipids were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (Birmingham, AL, U.S.A.).

Preparation of junctional SR vesicles from rabbit skeletal muscle

A heavy fraction of fragmented SR (HSR) vesicles, containing junctional SR, was prepared from rabbit fast-twitch back and leg muscles as described previously [19].

Purification of Ca2+-release channel

RyR1 was isolated as described previously [20]. SR vesicles (approx. 10 mg of protein) were solubilized in 10.5 ml of buffer A [1 M NaC1, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.2 mM Ca2+, 5 mM AMP, 1 mM dithiothreitol and 20 mM sodium Pipes (pH 7.4)] containing 1.5% (w/v) CHAPS and 5 mg/ml phosphatidylcholine [95% (w/w) soya-bean phosphatidylcholine] for 1 h at 4 °C. After further incubation of the solubilization mixture (3.5 ml aliquot) with 2 nM [3H]ryanodine for 1 h at 23 °C and for 1 h on ice to monitor the extent of RyR1 solubilization and migration of the solubilized RyR on sucrose gradients, CHAPS-insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 80000 g for 30 min. The supernatant was layered (approx. 3.5 ml each) on the top of linear gradients made up of 17 ml of a 7% (w/v) sucrose solution in buffer A containing 1% CHAPS and 5 mg/ml phosphatidylcholine, and 17 ml of a 15% (w/v) sucrose solution in buffer A containing 0.5% CHAPS and 5 mg/ml phosphatidylcholine. The gradients were centrifuged at 4 °C in a Beckman SW28 rotor (Palo Alto, CA, U.S.A.) at 26000 rev./min for 16 h, followed by fractionation into 2 ml fractions, and each fraction was used to determine the position of bound 3H radioactivity on the sucrose gradient. Unlabelled receptor peak fractions (without adding [3H]ryanodine) were pooled, concentrated using a Centriprep 30 concentrator (Amicon, Bedford, MA, U.S.A.) and stored at −70 °C before use.

Planar lipid bilayer

Single-channel recordings of rabbit skeletal RyR1 incorporated into the planar lipid bilayer were carried out as described previously [21–23]. Lipid bilayers, consisting of brain tissue phospha-tidylethanolamine and phosphatidylserine (1:1) in decane (20 mg/ml), were formed across a hole of approx. 200 μm diameter. Thinning of the bilayer was monitored by bilayer capacitance. The basic composition of the cis/trans solution was 300 mM caesium methanesulfonate, 10 mM Tris/Hepes (pH 7.2) and 10 μM free Ca2+ [23]. Incorporation of ion channels was carried out as described by Miller and Racker [21] and confirmed by recording the characteristically high single-channel conductance of the RyRs [20,23]. The trans side was maintained at ground and the cis side was clamped at −30 mV relative to the ground. The effects of DIDS, caffeine, ryanodine, Ruthenium Red, GAPDH, malate dehydrogenase, adenylate kinase and aldolase on channel activity were tested by their addition to the cis side, which corresponded to the cytoplasmic side of the SR membrane. Solutions with different free-Ca2+ concentrations were prepared by varying the ratio of EGTA and CaCl2 concentrations, as described previously [19].

DIDS-affinity column chromatography

Dry CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B beads were allowed to swell in a buffer composed of 50 mM sodium carbonate (pH 9) and reacted with 10 mM 1,5-diaminopentane for 36 h at 4 °C [24]. The beads were washed several times with the same buffer and reacted with 3 mM DIDS at 4 °C for 48 h (DIDS-affinity beads). After packing of the beads in a column (6 cm in length and 2.3 cm in diameter), DIDS-affinity column was washed with >50 volumes of the column buffer composed of 10 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.4), 0.5 M NaCl and 1% (v/v) Nonidet P40 at 4 °C. Nonidet P40 (1%)-solubilized junctional SR was passed through the equilibrated DIDS-affinity column. The column was washed with another 20 volumes of the column buffer until the A280 had returned to a stable baseline, and then the column-bound proteins were eluted with the column buffer containing 0.5–2 M KCl.

Aldolase-affinity batch-column chromatography

Dry CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B beads (0.1 g) were allowed to swell in 1 mM HCl for 20 min at 0 °C, and then washed several times with coupling buffer composed of 100 mM carbonate (pH 8.3) and 0.5 M NaCl. The beads were suspended in coupling buffer with 5 mM rabbit skeletal aldolase for 16 h at 4 °C (aldolase-affinity bead), and the beads were incubated with a blocking buffer composed of 1 M ethanolamine (pH 8.0) and 0.5 M NaCl for 16 h at 4 °C to block any remaining active groups. Excess ligands were removed by alternative washing with coupling buffer and then with a solution of 0.1 M acetate (pH 4.0) and 0.5 M NaCl. For batch-column chromatography, solubilized junctional SR vesicles (250 μg) in 20 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.4), 0.5 M NaCl and 1% (v/v) Triton X-100 were incubated for 4 h at 4 °C with the aldolase-affinity beads (10 μg). The protein–bead complexes were washed repeatedly with PBS [137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4 (pH 7.4) and 2 mM KH2PO4] containing the protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany) to remove non-specifically bound proteins. The affinity-bead-bound proteins were boiled (100 °C for 10 min) in the SDS sample buffer and subjected to SDS/PAGE [7.5 or 10% (w/v) gel] for immunoblot analysis with anti-RyR1 or anti-aldolase antibodies.

2D (two-dimensional) PAGE and MS analysis

CHAPS-solubilized proteins (80 μg) were adsorbed on to 13 cm IPG (immobilized pH gradient) strips (pH 3–10) and then subjected to isoelectric focusing on an IPGphor IEF unit (Amersham Biosciences). The focused IPG strips were placed on to 12.5% acrylamide gel and the proteins separated by SDS/PAGE (15 mA/gel). Spots of interest were manually excised from silver-stained 2D gels and processed according to standard methods [25,26]. MALDI–TOF (matrix-assisted laser-desorption ionization–time-of-flight) MS analyses were performed on a Voyager-DE STR mass spectrometer (PerSeptive Biosystems, Framingham, MA, U.S.A.), operated in the delayed extraction and reflector mode. Tandem mass sequencing analysis was carried out using the MALDI–TOF mass spectrometer 4700 Proteomics Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Spectra were calibrated using a matrix and tryptic autodigestion ion peaks as internal standards. Peptides selected from the tandem MS analysis were sequenced by using fragmentation by low-energy collision-induced dissociation. The peptide sequence was manually deduced from the labelled b and y ions (corresponding to N- and C-terminal peptide fragments) in the collision-induced dissociation fragmentation spectrum. The peptide masses were used for searches with the MS-Fit/NCBInr developed at University of California at San Fransisco Mass Spectrometry Facility (http://prospector.ucsf.edu).

[3H]Ryanodine-binding assay

DIDS-and/or aldolase-activated [3H]ryanodine binding was measured as described previously [27]. Briefly, equilibrium ryanodine binding to SR was performed by incubation of 0.05 mg of SR in 250 μl of reaction mixture containing 0.2 M KCl, 20 mM Mops, 1 nM [3H]ryanodine and 10 μM free Ca2+ (pH 7.3) for 2 h at 37 °C. PEG [poly(ethylene glycol)] solution [100 μl; 30% (w/v) PEG, 1 mM EDTA and 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.3)] was added to each vial and further incubated for 5 min at room temperature (25 °C). Precipitated protein was sedimented for 5 min at 12000 g in an Eppendorf microcentrifuge, and the pellets were rinsed twice with 0.4 ml of the appropriate ryanodine-binding buffer without radioactive ryanodine. The pellets were then solubilized in 100 μl of Soluene 350 (Packard, Boston, MA, U.S.A.) at 70 °C for 30 min and then radioactivity was counted with 4 ml of Picofluor (Packard) by a liquid scintillation counter. For non-specific binding, a 1000-fold amount of non-radioactive ryanodine (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.) was included. In the case of purified RyR1, 5 μg of purified RyR1 was used with 0.4 mg/ml BSA. For the PEG solution, BSA and γ-globulin (5 mg of each per ml) were used as carrier proteins.

Co-immunoprecipitation studies

HSR vesicles (1 mg/ml) were solubilized in a solution containing 0.1 M NaCl, 1% CHAPS and 20 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.4) on ice for 1 h. For co-immunoprecipitation studies, the CHAPS-solubilized junctional SR fraction was centrifuged at 20000 g in a Beckman Ti70 rotor for 20 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was incubated at 4 °C for 4 h with a monoclonal anti-RyR1 or anti-aldolase antibody, followed by incubation with Protein G–Sepharose affinity beads at 4 °C for 4 h. The protein–bead complexes were washed repeatedly with 0.1% CHAPS/PBS solution with protease inhibitors to remove non-specifically bound proteins. The bound proteins were subjected to SDS/PAGE and immunoblot analysis with the anti-RyR1 or anti-aldolase antibody.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as the means±S.E.M. Significance differences were analysed by paired or unpaired Student's t test and ANOVA. Differences were considered to be significant when P<0.05. EC50 values for the RyR1 agonists were calculated using the Hill equation. The fitting of data to the graphs were carried out using Origin v7.

RESULTS

Effects of DIDS on single-channel properties of RyR1 using SR vesicles (native RyR1)

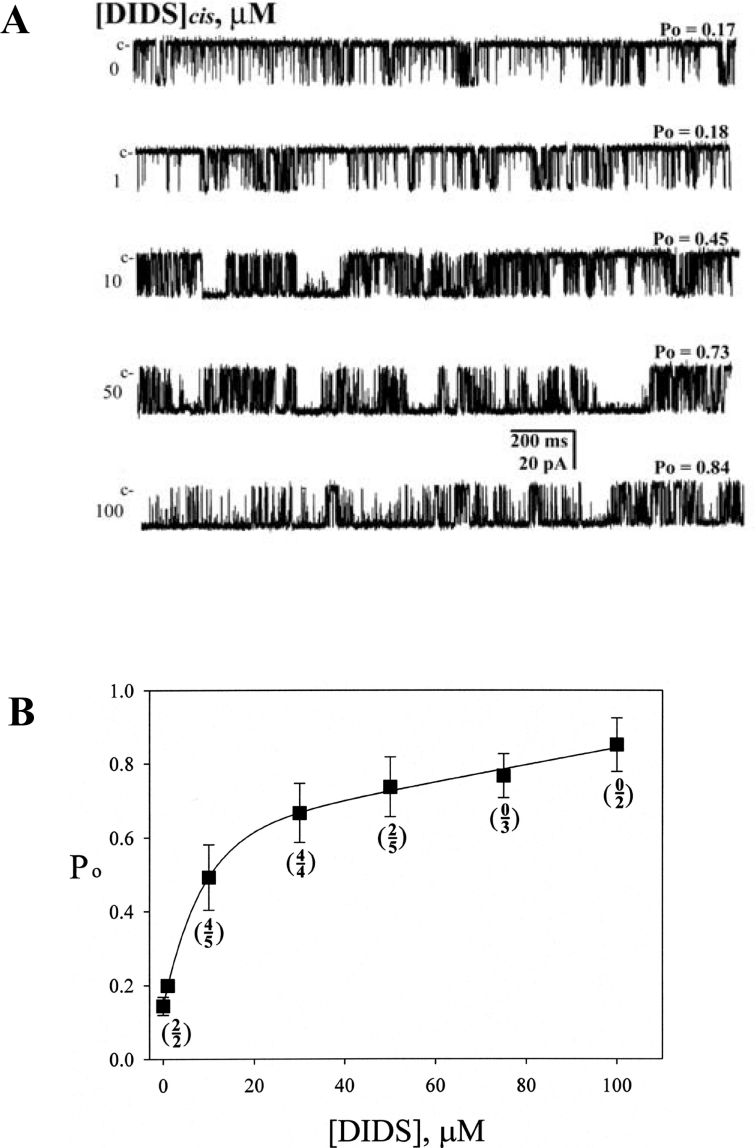

To examine how DIDS alters RyR1 channel activity, HSR vesicles from rabbit skeletal muscle were incorporated into planar lipid bilayers, and the single-channel properties of the native RyR1 were examined. The chamber solution for both cis and trans sides included 300 mM caesium methanesulfonate, 10 mM Tris/Hepes (pH 7.2) and 10 μM free Ca2+. DIDS was added to the cis (cyto-solic) side. Figure 1(A) shows the typical channel current traces of a single native RyR1 activated by various concentrations of DIDS (0–100 μM). Channel activity was monitored at a holding potential of −30 mV for over 120 s for each condition. The mean Po was 0.175±0.080 in the absence of DIDS, and 0.451±0.038 and 0.850±0.032 after addition of 10 and 100 μM DIDS respectively (Figure 1 and see Supplementary Table 1 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/399/bj3990325add.htm). The increased Po by 10 μM DIDS was accompanied by a pronounced change in open and closed time constants (Supplementary Table 1). The most outstanding effect was an appearance of the new third open time (τo3=16.820±5.340) and closed time (τc3=29.067±11.643) components.

Figure 1. Single native RyR1 channels are activated by DIDS.

(A) Channel current traces of a single native RyR1 activated by various concentrations of DIDS (0, 1, 10, 50 or 100 μM) are shown. DIDS was added to the cis side to activate the channel in the presence of 10 μM free Ca2+. Single-channel currents are shown as downward deflections from the closed level (indicated by c). Channel activities were recorded at a holding potential of −30 mV. (B) The plot of Po versus various concentrations of DIDS is shown. The numerals and denominators shown in the parentheses represent the number of channels showing a reversibility and the number of channels used for the experiments respectively. The activity was monitored for over 120 s in each condition. The average Po obtained at 10 μM Ca2+ was 0.15±0.02, which increased to 0.19±0.04, 0.44±0.04, 0.65±0.03, 0.71±0.03, 0.78±0.04 and 0.88±0.05 after addition of 1, 10, 30, 50, 75 and 100 μM DIDS respectively. At 1, 10 and 30 μM DIDS, the average Po fell to 0.17±0.02, 0.15±0.06 and 0.18±0.03 respectively, after washing out DIDS with the cis solution for 2 min (reversible). On the other hand, at 50, 75 and 100 μM DIDS, the average Po became 0.55±0.08, 0.68±0.05 and 0.80±0.06 respectively, after the washing out (irreversible).

Figure 1(B) shows the DIDS concentration-dependence of RyR1 on Po measured in the presence of 10 μM Ca2+. A fitting of the curve suggested two phases, an exponential phase at 1–30 μM DIDS and a linear phase at >30 μM DIDS. We examined the reversibility of DIDS-activated RyR1 by washing out DIDS with the cis solution for 2 min. Most of the RyR1s exposed to 1–30 μM DIDS were reversible (ten channels from a total of 11), but they became irreversible at the higher concentrations (two channels from a total of ten) (Figure 1B, frequencies of reversibility in parentheses). Therefore the two distinct phases appeared to be linked to the mechanisms responsible for the reversible and irreversible activation of RyR1.

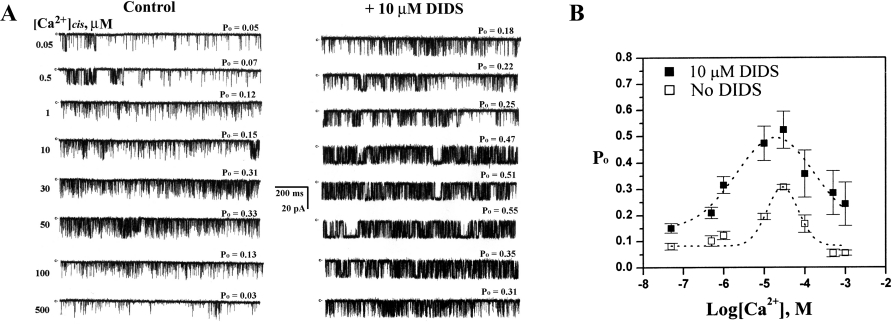

Ca2+-dependent activation of native RyR1 in the presence of DIDS

Figure 2(B) shows bell-shaped Ca2+-dependence curves of native RyR1 in the absence and presence of 10 μM DIDS (Figure 2A). Addition of 10 μM DIDS to the cis side increased both the ascending and descending phases of the Ca2+-activation/inhibition curve (Figure 2B) and reduced Ca2+ concentration to produce half maximal activation of native RyR1 [EC50 values with (10 μM) and without DIDS respectively: 1.68±1.02 μM compared with 11.48±5.62 μM], suggesting that DIDS increased the Ca2+ affinity to native RyR1.

Figure 2. Ca2+-dependence of single native RyR1 activation in the presence of DIDS.

(A) Single-channel currents were recorded at various concentrations of Ca2+, as indicated, without (control) or with 10 μM DIDS. Single-channel currents are shown as downward deflections from the closed level (indicated by c). (B) Plots of Po versus Ca2+ concentration without (□) or with (■) 10 μM DIDS are shown. Current recordings were obtained at −30 mV. The results are expressed as the means±S.E.M. for 5 independent experiments.

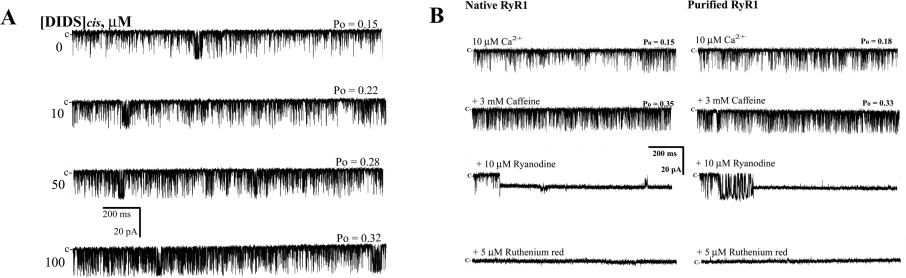

DIDS has a much less potent effect on purified RyR1

We incorporated purified RyR1 into lipid bilayers to determine whether the activation of native RyR1 by DIDS (Figures 1 and 2) was due to a direct activation of RyR1 by DIDS or to an indirect activation by another protein associated with RyR1, as proposed by other groups previously [10,11,14–18]. Unlike native RyR1 shown in Figure 1, addition of DIDS at a concentration between 10 and 100 μM to the cis side in the presence of 10 μM Ca2+ led to only a small increase in Po (Figure 3A, and see Figure 5A, right-hand panel). DIDS also failed to significantly affect the gating properties of purified RyR1 (Supplementary Table 1). The pronounced appearance of the third component (τo3) in native RyR1 in response to 10 μM DIDS was absent in the purified RyR1, indicating that the effectiveness of DIDS was considerably decreased in purified RyR1. On the other hand, 3 mM caffeine increased Po both in native and purified RyR1 to a similar extent (Supplementary Table 1). In addition, the single RyR1 currents activated by 10 μM Ca2+ were locked in a subconductance state by 10 μM ryanodine and completely blocked by 5 μM Ruthenium Red both in native and purified RyR1 (Figure 3B), suggesting that the properties of RyR1 responding to the pharmacological agents was not changed by the purification process.

Figure 3. Effect of DIDS on purified RyR1.

(A) Single-channel activity of purified RyR1 was recorded with 10 μM Ca2+ without (control) or with DIDS (10–100 μM). Single-channel currents are shown as downward deflections from the closed level (indicated by c). The holding potential was −30 mV. Note that the extent of channel activation by 10 μM DIDS was considerably lower in purified RyR1 compared with native RyR1 in Figure 1. (B) Native RyR1 or purified RyR1 was activated or modified by serial addition of 10 μM Ca2+, 3 mM caffeine, 10 μM ryanodine and 5 μM Ruthenium Red. Note that the patterns of the activation and modification by Ca2+, caffeine, ryanodine and Ruthenium Red are similar between native and purified RyR1s (Supplementary Table 1).

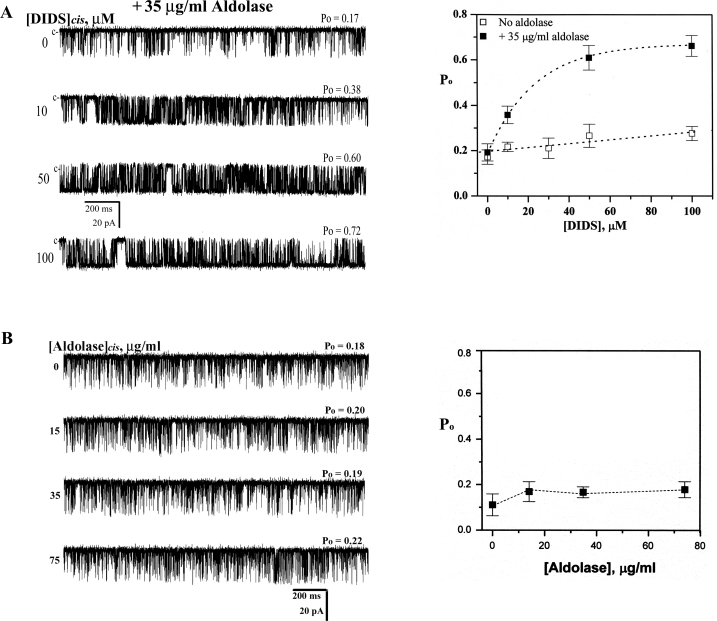

Figure 5. DIDS dependence of purified RyR1 channel activity in the presence or absence of aldolase.

(A) Channel current traces of a single purified RyR1 were recorded in the presence of various concentrations of DIDS (10 to 100 μM) with 35 μg/ml aldolase (left-hand panel). Plots of Po versus various concentrations of DIDS in the absence (□) and presence (■) of aldolase are shown (right-hand panel). The results are expressed as the means±S.E.M. The number of observations were 7, 7, 6 and 5 for 0, 10, 50 and 100 μM DIDS respectively in the presence of 35 μg/ml aldolase. (B) Channel current traces of single purified RyR1 were recorded in the presence of increasing concentrations of aldolase (0 to 75 μg/ml). The plot of Po versus various concentrations of aldolase is shown. The results are expressed as the means±S.E.M. for 5 independent experiments.

Identification of the DIDS-bound proteins

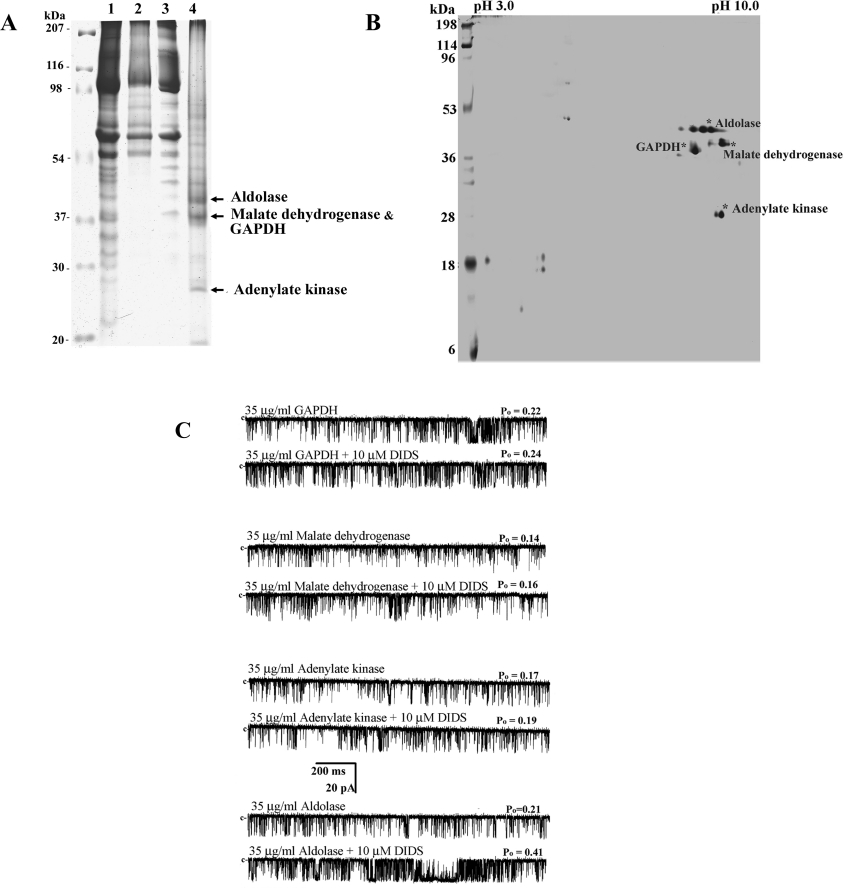

We attempted to isolate and characterize DIDS-binding protein(s) in HSR by DIDS-affinity column chromatography using detergent-solubilized HSR vesicles. We prepared a DIDS-affinity column composed of DIDS–diaminopentane-linked CNBr-Sepharose 4B [24]. The method was especially useful for the isolation of reversibly interacting proteins to DIDS, since the S=C=N groups located on both sides of DIDS molecules are supposed to be masked by CNBr-Sepharose molecules, so that only reversibly bound proteins could be recovered from the gel matrix when eluted. Figures 4(A, lane 4) and 4(B) show the representative 1D or 2D gel of the affinity-purified DIDS-binding proteins. To identify the major DIDS-binding proteins shown in Figures 4(A, lane 4) and 4(B), gel slices containing the corresponding bands and spots were digested with trypsin, and then subjected to MALDI–TOF MS analysis, as described in the Experimental section. Four major DIDS-binding proteins from HSR were identified: 40 kDa aldolase (NCBI accession number 13096351), 38 kDa malate dehydrogenase (NCBI accession number 65932), 37 kDa GAPDH (NCBI accession number 6016083) and 27 kDa adenylate kinase 1 (NCBI accession number 125152). Additional minor DIDS-binding proteins, such as RyR1 and chloride channel type 1, were also identified by Western-blot analysis.

Figure 4. DIDS-affinity column chromatography for identifying the DIDS-binding protein(s).

(A) HSR (lane 1), CNBr-bead-binding proteins (lane 2), DIDS-affinity bead-unbound proteins (lane 3) and DIDS-affinity bead-bound proteins (lane 4) (80 μg of each) were separated by SDS/PAGE (10% gel), and then the gels were stained with Coomassie Blue. The protein yield of the DIDS-binding proteins was approx. 3% of the SR proteins loaded on to the affinity gel. (B) Silver-stained 2D gel showing the proteins bound to the DIDS-affinity beads. Major four protein bands in lane 4 (A) were identified as aldolase, malate dehydrogenase, GAPDH and adenylate kinase by MALDI–TOF MS analysis. The colorimetric development of the protein spots was stopped when the major proteins appeared. (C) Channel current traces of a single purified RyR1 activated by one of four DIDS-binding proteins in the presence of 10 μM Ca2+ are shown. Each DIDS-binding protein (35 μg/ml) was added to the cis side.

Recovery of the DIDS sensitivity of purified RyR1 by aldolase

To test whether one of the four DIDS-binding proteins in HSR identified by DIDS-affinity column chromatography, as described above, could confer DIDS sensitivity to purified RyR1, each DIDS-binding protein was added to cis side of RyR1 incorporated into lipid bilayers in the presence or absence of 10 μM DIDS (Figure 4C). We found that only aldolase increased Po of RyR1 in the presence of DIDS, although aldolase by itself did not change Po of RyR1 (Supplementary Table 2 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/399/bj3990325add.htm).

A detailed study of aldolase-mediated RyR1 activation by DIDS was examined by measuring single-channel properties of purified RyR1 in the presence of aldolase. Figure 5(A, left-hand panel) shows representative current records of a single purified RyR1 measured in the presence of increasing concentrations of DIDS at a fixed concentration of aldolase (35 μg/ml). The channel activity was monitored at a −30 mV holding potential for over 120 s in each condition. The channel activity in the presence of aldolase was significantly higher than that measured in the absence of aldolase at all the DIDS concentrations tested (Figure 5A, right-hand panel). However, aldolase by itself in the concentration range between 15 and 75 μg/ml did not significantly affect channel activity (Figure 5B).

To obtain a clearer picture of the single-channel events leading to the increased activation of RyR1 by DIDS in the presence of aldolase, we performed lifetime analysis of single purified RyR1 (Supplementary Table 1). The results indicate that the single-channel properties measured after the addition of aldolase to the cis solution containing 10 μM DIDS were similar to those found in the native RyR1, implying that aldolase is the protein conferring DIDS sensitivity in the native SR.

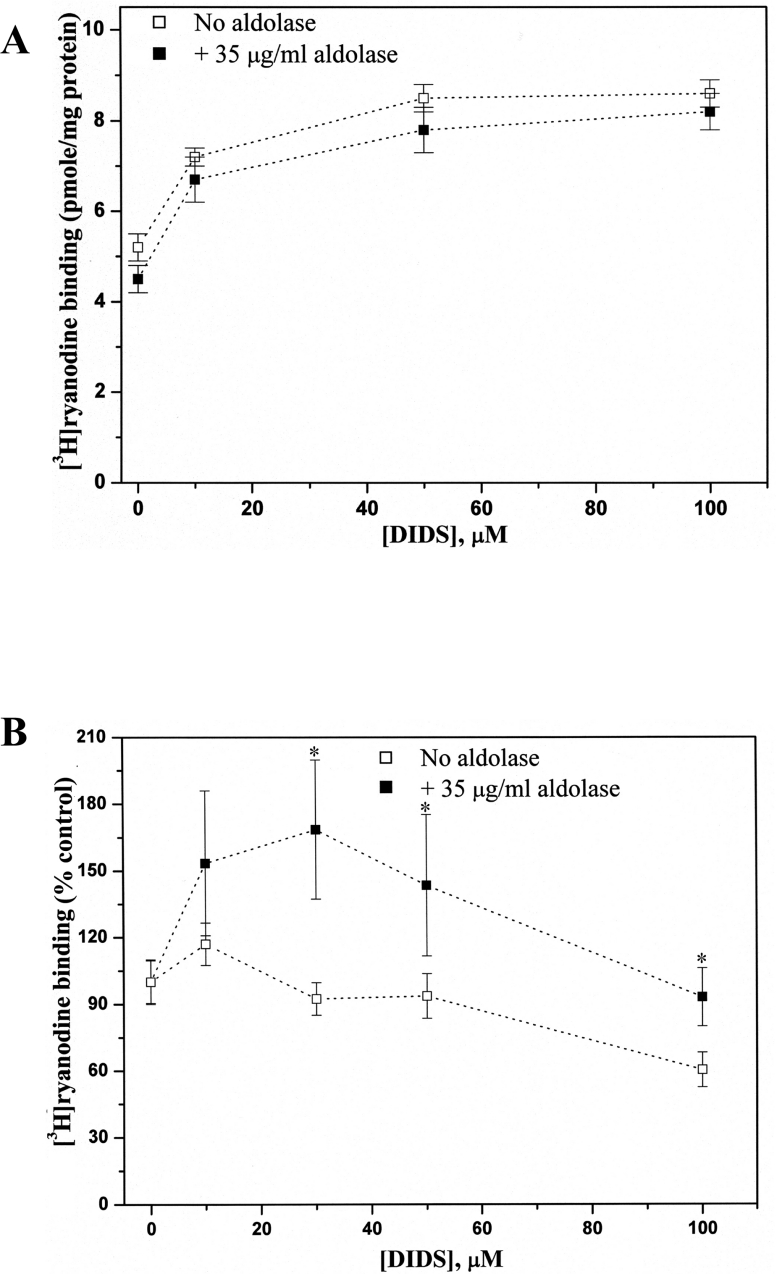

DIDS dependence of [3H]ryanodine binding to native and purified RyR1 in the presence of aldolase

Potentiation of the effect of DIDS on RyR1 by aldolase (Figure 5B) was further confirmed by [3H]ryanodine binding to both native (Figure 6A) and purified RyR1 (Figure 6B). The DIDS-concentration dependence of [3H]ryanodine binding to native RyR1 showed that an addition of aldolase (35 μg/ml) did not change the concentration dependence of [3H]ryanodine binding (Figure 6A). On the other hand, DIDS-concentration dependence of [3H]ryanodine binding to purified RyR1 showed a significantly elevated [3H]ryanodine binding at all of the tested DIDS concentrations by addition of aldolase (Figure 6B), confirming that the presence of aldolase potentiates the responsiveness of RyR1 to DIDS. The reason for the decreased [3H]ryanodine binding to purified RyR1 at DIDS concentrations over 50 μM (Figure 6B) remains unclear.

Figure 6. Effects of DIDS on [3H]ryanodine binding to native and purified RyR1s in the presence or absence of aldolase.

Equilibrium [3H]ryanodine binding to native (A) or purified (B) RyR1s was performed as described in the Experimental section in the presence of 10 μM free Ca2+ without (□) or with (■) 35 μg/ml aldolase. With purified RyR1, 30 μM DIDS in the presence of 35 μg/ml aldolase induced a greater increase in activity compared with the absence of aldolase. The control is the specific [3H]ryanodine binding in the presence of 10 μM free Ca2+ (pH 7.3). Specific [3H]ryanodine binding at the various concentration of DIDS with or without aldolase is expressed as a percentage of the control. *Significantly different between the two experimental groups (unpaired Student's t test, P<0.05). The results are expressed as the means±S.E.M. for 5 independent experiments.

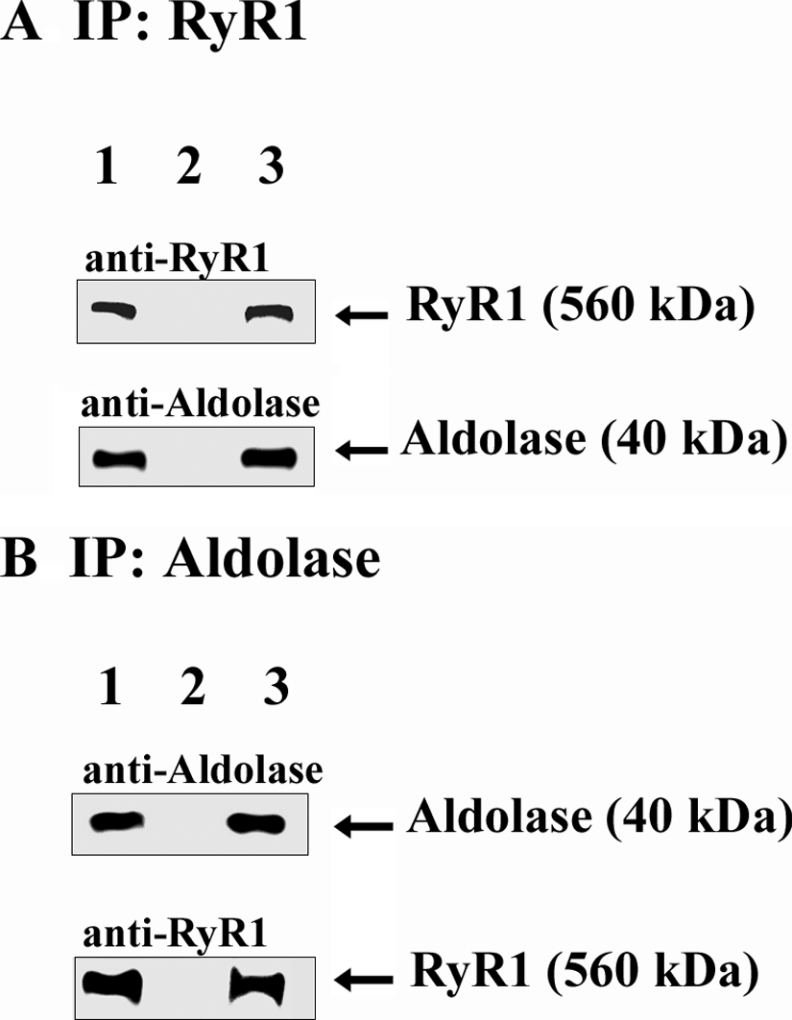

Direct interaction between RyR1 and adolase

Previously, Brandt et al. [28] have already shown an interaction between aldolase and RyR1, employing affinity-chromatography and protein-overlay techniques. In the present study, we first conducted co-immunoprecipitation assay using 1% CHAPS-solubilized SR (Figure 7). Aldolase was co-immunoprecipitated using the anti-RyR1 antibody (Figure 7A), and RyR1 was also co-immunoprecipitated with the anti-aldolase antibody (Figure 7B), confirming that aldolase physically interacts with RyR1.

Figure 7. Co-immunoprecipitation of RyR1 with aldolase.

The anti-RyR1 antibody (A) or anti-aldolase antibody (B) with Protein G–Sepharose affinity beads was incubated with solubilized SR (100 μg), and the immunoprecipitates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the anti-RyR1 or anti-aldolase antibody. Lane 1, HSR (10 μg); lane 2, immunoprecipitates from mouse pre-immune serum (A) or goat pre-immune serum (B); lane 3, immunoprecipitates from the anti-RyR antibody (A) or anti-aldolase antibody (B).

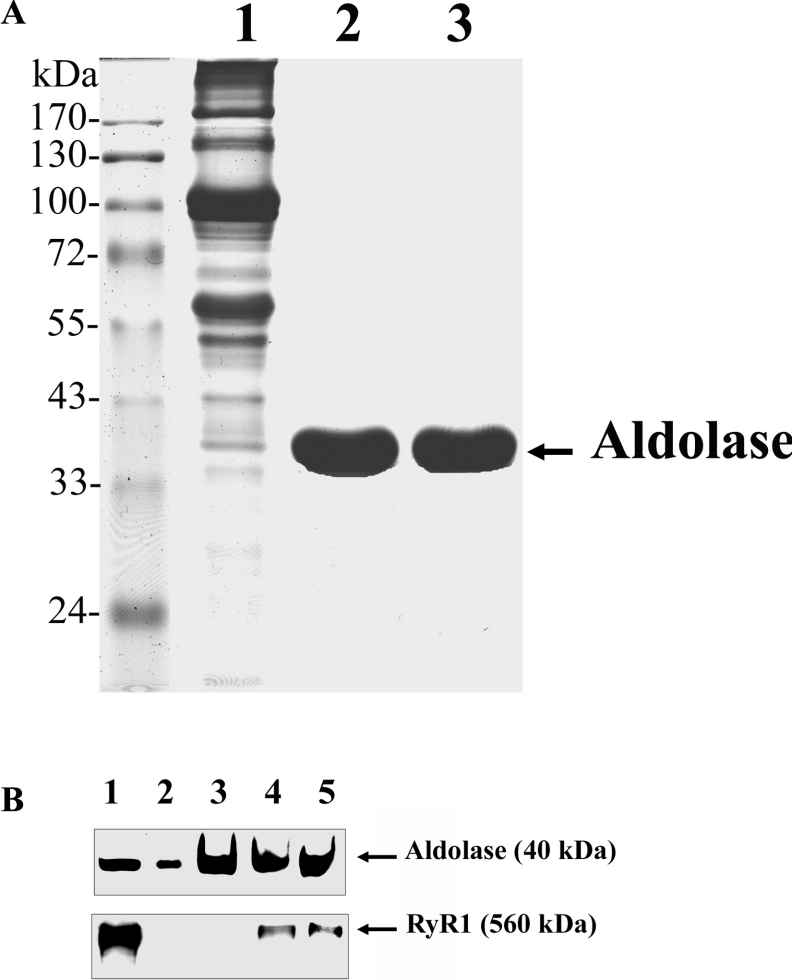

Secondly, the interaction between RyR1 and aldolase was further investigated by aldolase-affinity batch-column chromatography using detergent-solubilized junctional SR in the presence or absence of DIDS. The conjugation of aldolase to the affinity-column beads was confirmed by immunoblot analysis with the anti-aldolase antibody (Figure 8A, lane 3). It appears that the proteins bound covalently to the aldolase-affinity beads were detachable after boiling for 10 min in the Laemmli SDS sample buffer, as shown previously [29]. The aldolase-affinity batch column incubated with solubilized junctional SR showed an interaction of RyR1 with aldolase (Figure 8B, lane 4). To test whether the presence of DIDS could affect the interaction between aldolase and RyR1, the same experiment was conducted in the presence of 100 μM DIDS (Figure 8B, lane 5). The results showed that the association of aldolase with RyR1 was not affected by the presence of DIDS (Figure 8B, lane 5), suggesting that DIDS and aldolase do not share the same binding site on RyR1.

Figure 8. Aldolase-affinity batch-column chromatography.

(A) SR (lane 1), purified aldolase (lane 2) and CNBr-bead-detached aldolase (lane 3) (30 μg of each) were separated by SDS/PAGE (10 % gel) and the gels were stained with Coomassie Blue. (B) Aldolase-affinity beads were incubated with Triton X-100-solubilized native SR. The bound proteins were eluted by SDS sample buffer, separated by SDS/PAGE (7.5 % gel) and subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-aldolase or anti-RyR antibodies. Lane 1, SR (10 μg); lane 2, purified aldolase (1 μg); lane 3, aldolase-affinity beads alone (2 μg); lane 4, aldolase-affinity bead-bound RyR1 in the absence of DIDS; lane 5, aldolase-affinity bead-bound RyR1 in the presence of 100 μM DIDS.

DISCUSSION

In previous studies, it has been reported that the stilbene-derivative DIDS could activate RyRs from both skeletal and cardiac muscles [8,9,12,16,17]. By various biochemical studies, a 30 kDa protein was identified as a calsequestrin-binding protein, a junction-like protein or ADP/ATP translocase [16,17], and was also assumed to be a DIDS-receptor protein that confers DIDS sensitivity to RyRs [16,17]. However, until now the identity of the 30 kDa protein has remained to be elucidated.

In the present study, we used both native and purified RyR1s from rabbit skeletal junctional SR for measurements of the single-channel properties in planar lipid bilayers. We found that there were substantial differences in the effect of 10 μM DIDS on RyR1 after purification procedures of RyR1. DIDS had a considerably weaker potentiation on purified RyR1, as shown by a considerably smaller increase in Po,max. The mean open and closed time constants and their proportions after 10 μM DIDS activation were also significantly different between native and purified RyRs (Supplementary Table 1). On the other hand, both native and purified RyRs showed similar responses to caffeine, ryanodine and Ruthenium Red (Figure 3), suggesting that the difference in DIDS sensitivity was not due to any conformational changes of RyR1 during RyR1 purification. Therefore we postulated that a DIDS-binding protein essential for DIDS sensitivity of RyR1 was lost during RyR1 purification.

Identification of DIDS-binding protein(s) in SR responsible for the activation of RyR1 has been controversial, due probably to the complex binding patterns of DIDS [10–12,15–18]. In the present study, we re-examined the identity of DIDS-binding proteins using a DIDS–diaminopentane-linked CNBr-Sepharose 4B affinity column [24]. The method was especially useful to isolate reversibly interacting DIDS-binding proteins, due to the prior covalent bond formations between the S=C=N residues of DIDS molecules and CNBr-Sepharose molecules. This isolation technique could also minimize the appearance of false-positive DIDS-binding proteins due to any non-specific covalent bond formation. With the DIDS-affinity chromatography, we have identified four major DIDS-binding proteins (40 kDa aldolase, 37 kDa malate dehydrogenase, 37 kDa GAPDH and 27 kDa adenylate kinase 1), which are soluble enzymes in the cytosol (Figure 4). The entirely different protein profiles between the CNBr-Sepharose-bound fraction (Figure 4A, lane 2) and the DIDS-affinity-columnbound fraction (Figure 4A, lane 4) indicate that the affinity column was specific.

In order to investigate whether one of the identified DIDS-binding proteins in HSR (Figure 4) confers DIDS sensitivity to RyR1, each of the four DIDS-binding proteins in high purity was tested on the single-channel properties of purified RyR1 in bilayers. Surprisingly, among the four DIDS-binding proteins, aldolase substantially potentiated the channel activity of RyR1 (Figure 4C and Supplementary Table 2). The lifetime of single-channel properties for the aldolase-added RyR1 were carefully analysed (Supplementary Table 1). Po was considerably increased by the addition of 35 μg/ml aldolase, due mainly to the occurrence of the third components in the open and closed time constants. It is important to note that the effects of DIDS on purified RyR1 became remarkably similar to native RyR1 by the addition of aldolase (Supplementary Table 1). Addition of aldolase alone (15–75 μg/ml) did not significantly alter Po of RyR1 within the experiment time (30 s stirring plus 2 min of measurement). Potentiation of the effects of DIDS on RyR1 was also observed by a [3H]ryanodine-binding study, although the experimental variations were somewhat greater than the single-channel study.

Studies by Sitsapesan and co-worker have demonstrated that RyR2s in sheep hearts could be reversibly activated at lower DIDS concentrations (e.g. 50 μM), but irreversibly activated at the higher DIDS concentrations (e.g. 500 μM) [10,11]. It was also found that 1–5 mM DIDS modified both native and purified RyR2 from sheep heart in a similar manner, suggesting that, at high irreversible DIDS concentrations, the major modification site(s) is on the RyR1 molecule itself. Our present observations also indicated that RyR1 could become reversible or irreversible depending on the activating DIDS concentrations (Figure 1B). The Ca2+-dependence of RyR1 activation was also differently modulated by reversible (Figure 2B) or irreversible concentrations of DIDS [13]. Taken together, DIDS could activate RyR1 by two different mechanisms: (i) the reversible interaction through the mediation of aldolase, and (ii) the irreversible interaction through RyR1 itself.

The specific interaction between RyR1 and aldolase has been reported previously by Brandt et al. [28], using immuno-affinity chromatography. In the present study, the direct physical interaction between the two proteins was further confirmed by co-immunoprecipitaion assay (Figure 7) and aldolase-affinity batch-column chromatography (Figure 8). According to our CD study, the spectral changes were observed upon DIDS binding to aldolase (I. Seo and D.H. Kim, unpublished work), suggesting that aldolase undergoes a substantial conformational change by DIDS binding.

The specific association of glycolytic and glycogenolytic enzymes with SR membranes and evidence that the enzymes may participate in striated muscle E–C coupling have been reported by various groups [28,30–32]. For example, enzymes such as phosphoglycerate kinase, glycogen synthase, glycogen-debranching enzyme and glucose 6-phosphatase have been reported to be associated with SR and ER (endoplasmic reticulum) [32,33]. It appears that the functions of these enzymes in SR are related to the production of ATP by glycolysis and therefore to supply energy to the SR Ca2+-ATPase [30,31]. It has been also suggested that specific glycolytic enzymes directly participate in the association between transverse tubules and junctional SR. An isoform of phosphoglucomutase could be involved in the regulation of SR functions [34–36], and the entire chain of glycolytic enzymes, including aldolase, is bound to both cardiac and skeletal muscle SR [28,37]. It is also interesting to note that aldolase can bind Ins(1,4,5)P3 in large quantities in porcine tracheal smooth muscle, suggesting the multi-functional role of aldolase [38].

The present study demonstrates that aldolase is associated with RyR1 and confers the considerable potentiation of DIDS sensitivity to RyR1. Elucidation of the molecular mechanism for the potentiation by aldolase must await further studies in the future. Since DIDS is not a physiological ligand, it is of interest to identify an endogenous DIDS-like compound in intact muscle cells.

Online data

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Korean Ministry of Science and Technology (Korean Systems Biology Research Grant, M1-0503-01-0001, to D.H.K.), Korean Ministry of Education (BK21 to D.H.K.) and NIH (National Institutes of Health) grant AR18687 (to G.M.). We thank Dr Soo Hyun Eom for the valuable discussions about the DIDS-affinity column.

References

- 1.Fleischer S., Inui M. Biochemistry and biophysics of excitation-contraction coupling. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 1989;18:333–364. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.18.060189.002001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rios E., Pizarro G., Stefani E. Charge movement and the nature of signal transduction in skeletal muscle excitation contraction coupling. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1992;54:109–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.54.030192.000545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franzini-Armstrong C., Protasi F. Ryanodine receptors of striated muscles: a complex channel capable of multiple interactions. Physiol. Rev. 1997;77:699–729. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.3.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fill M., Copello J. A. Ryanodine receptor calcium release channels. Physiol. Rev. 2002;82:893–922. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meissner G. Regulation of mammalian ryanodine receptors. Front Biosci. 7. 2002:d2072–d2080. doi: 10.2741/A899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogawa Y., Kurebayashi N., Murayama T. Putative roles of type 3 ryanodine receptor isoforms (RyR3) Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2000;10:65–70. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(00)00050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hua S., Inesi G. Lys515–Lys492 cross-linking by DIDS interferes with substrate utilization by the sarcoplasmic reticulum ATPase. Biophys. J. 1997;73:2149–2155. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78245-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawasaki T., Kasai M. Disulfonic stilbene derivatives open the Ca2+ release channel of sarcoplasmic reticulum. J. Biochem. 1989;106:401–405. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zahradnikova A., Zahradnik I. Modification of cardiac Ca2+ release channel gating by DIDS. Pfluegers Arch. 1993;425:555–557. doi: 10.1007/BF00374886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sitsapesan R. Similarities in the effects of DIDS, DBDS and suramin on cardiac ryanodine receptor function. J. Membr. Biol. 1999;168:159–168. doi: 10.1007/s002329900506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill A. P., Sitsapesan R. DIDS modifies the conductance, gating, and inactivation mechanisms of the cardiac ryanodine receptor. Biophys. J. 2002;82:3037–3047. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75644-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Neill E. R., Sakowska M. M., Laver D. R. Regulation of the calcium release channel from skeletal muscle by suramin and the disulfonated stilbene derivatives DIDS, DBDS, and DNDS. Biophys. J. 2003;84:1674–1689. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74976-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oba T., Koshita M., Van Helden D. F. Modulation of frog skeletal muscle Ca2+ release channel gating by anion channel blockers. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:C819–C824. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.3.C819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klinger M., Bofill-Cardona E., Mayer B., Nanoff C., Freissmuth M., Hohenegger M. Suramin and the suramin analogue NF307 discriminate among calmodulin-binding sites. Biochem. J. 2001;355:827–833. doi: 10.1042/bj3550827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamaguchi N., Kawasaki T., Kasai M. DIDS binding 30-kDa protein regulates the calcium release channel in the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995;210:648–653. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kagari T., Yamaguchi N., Kasai M. Biochemical characterization of calsequestrin-binding 30-kDa protein in sarcoplasmic reticulum of skeletal muscle. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;227:700–706. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamaguchi N., Kasai M. Identification of 30 kDa calsequestrin-binding protein, which regulates calcium release from sarcoplasmic reticulum of rabbit skeletal muscle. Biochem. J. 1998;335:541–547. doi: 10.1042/bj3350541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirata Y., Nakahata N., Ohkura M., Ohizumi Y. Identification of 30 kDa protein for Ca2+ releasing action of myotoxin a with a mechanism common to DIDS in skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1451:132–140. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(99)00082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim D. H., Ohnishi S. T., Ikemoto N. Kinetic studies of calcium release from sarcoplasmic reticulum in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258:9662–9668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai F. A., Erickson H. P., Rousseau E., Liu Q.-Y., Meissner G. Purification and reconstitution of the calcium release channel from skeletal muscle. Nature (London) 1988;331:315–319. doi: 10.1038/331315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller C., Racker E. Ca2+-induced fusion of fragmented sarcoplasmic reticulum with artificial planar bilayers. J. Membr. Biol. 1976;30:283–300. doi: 10.1007/BF01869673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith J. S., Coronado R., Meissner G. Single channel measurements of the calcium release channel from skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. Activation by Ca2+ and ATP and modulation by Mg2+ J. Gen. Physiol. 1986;88:573–588. doi: 10.1085/jgp.88.5.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee E. H., Meissner G., Kim D. H. Effects of quercetin on single Ca2+ release channel behavior of skeletal muscle. Biophys. J. 2002;82:1266–1277. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75483-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blair H. C., Schlesinger P. H. Purification of a stilbene sensitivity chloride channel and reconstitution of chloride conductivity into phospholipids vesicles. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1990;171:920–925. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)90771-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gharahdaghi F., Weinberg C. R., Meagher D. A., Imai B. S., Mische S. M. Mass spectrometric identification of proteins from silver-stained polyacrylamide gel: a method for the removal of silver ions to enhance sensitivity. Electrophoresis. 1999;20:601–605. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19990301)20:3<601::AID-ELPS601>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oh-Ishi M., Satoh M., Maeda T. Preparative two-dimenstional gel electrophoresis with agarose gels in the first dimension for high molecular mass proteins. Electrophoresis. 2000;21:1653–1669. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(20000501)21:9<1653::AID-ELPS1653>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim D. H., Mkparu F., Kim C., Caroll R. F. Alteration of Ca2+ release channel function in sarcoplasmic reticulum of pressure-overload-induced hypertrophic rat heart. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1994;26:1505–1512. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1994.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brandt N. R., Caswell A. H., Wen S. R., Talvenheimo J. A. Molecular interactions of the junctional foot protein and dihydropyridine receptor in skeletal muscle triads. J. Membr. Biol. 1990;113:237–251. doi: 10.1007/BF01870075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu G., Cirilli M., Huang Y., Rich R. L., Myszka D. G., Wu H. Covalent inhibition revealed by the crystal structure of the caspase-8/p35 complex. Nature (London) 2001;410:494–497. doi: 10.1038/35068604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Entman M. L., Kaniike K., Goldstein M. A., Nelson T. E., Bornet E. P., Futch T. W., Schwartz A. Association of gylcogenolysis with cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 1976;251:3140–3146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Entman M. L., Keslensky S. S., Chu A., Van Winkle W. B. The sarcoplasmic reticulum-glycogenolytic complex in mammalian fast twitch skeletal muscle. Proposed in vitro counterpart of the contraction-activated glycogenolytic pool. J. Biol. Chem. 1980;255:6245–6252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pierce B. N., Philipson K. D. Binding of glycolytic enzymes to cardiac sarcolemmal and sarcoplasmic reticular membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:6862–6870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waddell I. D., Burchell A. Transverse topology of glucose-6-phosphatase in rat hepatic endoplasmic reticulum. Biochem. J. 1991;275:133–137. doi: 10.1042/bj2750133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell K. P., MacLennan D. H. A calmodulin-dependent protein kinase system from skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. Phosphorylation of a 60,000-dalton protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:1238–1246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim D. H., Ikemoto N. Involvement of 60-kilodalton phosphoprotein in the regulation of calcium release from skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:11674–11679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee Y. S., Marks A. R., Gureckas S. N., Lacro R., Nadal-Ginard B., Kim D. H. Purification, characterization, and molecular cloning of a 60-kDa phosphoprotein in rabbit skeletal sarcoplasmic reticulum which is an isoform of phosphoglucomutase. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:21080–21088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu K. Y., Becker L. C. Ultrastructural localization of glycolytic enzymes on sarcoplasmic reticulum vesicles. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1998;46:419–427. doi: 10.1177/002215549804600401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baron C. B., Ozaki S., Watanabe Y., Hirata M., LaBelle E. F., Coburn R. F. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate binding to porcine tracheal smooth muscle aldolase. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:20459–20465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.35.20459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.