Abstract

Chlamydophila pneumoniae is a pathogen that is involved in acute and chronic respiratory infections and that is associated with asthma and coronary artery diseases. In this study, we evaluated the effects of PEX, a noncatalytic metalloproteinase fragment with integrin-binding activity, against experimental infections caused by C. pneumoniae. Moreover, we investigated the relationships between C. pneumoniae and αvβ3 integrin functions in order to explain the possible mechanism of action of PEX both in vitro and in vivo. For the in vitro experiments, HeLa cells were infected with C. pneumoniae and treated with either PEX or azithromycin. The results obtained with PEX were not significantly different (P > 0.05) from those achieved with azithromycin. Similar results were also obtained in a lung infection model. Male C57BL/J6 mice inoculated intranasally with 106 inclusion-forming units of C. pneumoniae were treated with either PEX or azithromycin plus rifampin. Infected mice treated with PEX showed a marked decrease in C. pneumoniae counts versus those for the controls; this finding did not differ significantly (P > 0.05) from the results observed for the antibiotic-treated group. Integrin αvβ3 plays an important role in C. pneumoniae infection. Blockage of integrin activation led to a significant inhibition of C. pneumoniae infection in HeLa cells. Moreover, CHODHFR αvβ3-expressing cells were significantly (P < 0.001) more susceptible to C. pneumoniae infection than CHODHFR cells. These results offer new perspectives on the treatment of C. pneumoniae infection and indicate that αvβ3 could be a promising target for new agents developed for activity against this pathogen.

Chlamydophila pneumoniae is responsible for respiratory infections, such as sinusitis, bronchitis, and pneumonia (8). The ability of C. pneumoniae to cause persistent infections, combined with its capacity to spread throughout the vascular system, has raised questions about the role of this bacterium in chronic human diseases, such as atherosclerosis. In 1988, Saikku et al. reported evidence of an association between acute myocardial infarction and C. pneumoniae (20). Since then, several studies have suggested a potential role of C. pneumoniae in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Increased antichlamydia antibody (Ab) titers have been correlated with coronary artery diseases (14). C. pneumoniae has been reported to infect a large number of vascular or circulating cells, such as endothelial cells, aortic smooth muscle cells, and macrophages (7). In addition, chlamydial infection has been observed to induce a series of events involved in plaque formation and evolution. Infected macrophages produce matrix-degrading metalloproteinases (MMPs), which bind to integrins and which promote plaque rupture (6). Moreover, cells infected with C. pneumoniae are resistant to apoptosis induced by various stimuli (18). These data suggest that the inhibition of proapoptotic pathways by C. pneumoniae might be a key factor in its persistence in host cells.

The adhesion and invasion of infectious agents and tumor cells via integrins have been studied for several years. The cytadherence of host cells, through recognition of the RGD-containing peptide (that is, a soluble synthetic peptide containing an arginine, glycine, and aspartic acid, which possess high-affinity αvβ3 integrin binding), RGDS, has been observed in Treponema pallidum and Trypanosoma cruzi (17, 23). Moreover, attachment of Borrelia burgdorferi mediated by integrins α5β1 and αvβ3, as well as RGD peptide sequences, has been reported, and the appropriate receptor-specific antibodies have been shown to inhibit this process (4). Integrins, which are important for the adhesion and invasion of several infectious agents, might also be involved in C. pneumoniae infection.

The aim of the present study was to assess whether PEX, which is a peptide with integrin-binding activity, is active against C. pneumoniae. Moreover, we investigated the relationship between C. pneumoniae and αvβ3 integrin functions. A link between αvβ3 integrin expression and C. pneumoniae infection might explain its selective localization in the plaques and help to explain the mechanism of action of PEX.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. pneumoniae in vitro infection model.

C. pneumoniae stock suspensions were prepared from the CWL-029 strain (CWL; ATCC VR-1310). Infection was established in HeLa 229, CHODHFR, and CHODHFR cells transfected with human αvβ3 integrin cDNA (CHODHFR-αvβ3) by centrifuging (2,000 × g for 2 h at 35°C) 1.5 × 106 inclusion-forming units (IFU) onto confluent cell monolayers in 12-well culture plates (10, 12). HeLa cell monolayers were exposed to C. pneumoniae elementary bodies and were treated for 30 min, before centrifugation, with one of the following reagents: monoclonal Ab (MAb) against human integrin αvβ3 (MAb LM609; 0.01 ng/ml to 1 μg/ml); an unspecific Ab (P0399 [Dako Ltd., Denmark]; 0.01 ng/ml to 1 μg/ml on HeLa 229 cells); PEX, a 210-amino-acid fragment of human MMP-2 that blocks integrin activation (0.01 ng/ml to 1 μg/ml) (2, 3); azithromycin (0.01 ng/ml to 5 μg/ml); soluble human integrin αvβ3 purified protein (0.01 ng/ml to 1 μg/ml), provided by Chemicon Int. (Temecula, CA); or bovine albumin (0.01 ng/ml to 1 μg/ml). In additional experiments, C. pneumoniae elementary bodies were pretreated for 30 min with soluble human integrin αvβ3 purified protein (0.01 ng/ml to 1 μg/ml), centrifuged at 30,000 × g for 45 min at 4°C, and resuspended in chlamydia growth medium; and then 1.5 × 106 IFU was used to infect HeLa cell monolayers. In addition, soluble human integrin αvβ3 purified protein (100 ng/ml) that had been pretreated for 30 min with PEX (100 ng/ml) was incubated with C. pneumoniae elementary bodies for 30 min. After centrifugation at 30,000 × g for 45 min at 4°C, C. pneumoniae elementary bodies were resuspended in chlamydia growth medium, and then 1.5 × 106 IFU was used to infect HeLa cell monolayers.

In all experiments, after centrifugation, the supernatant was replaced with fresh chlamydia growth medium (treated as described above), and HeLa 229 cells were incubated for 72 h (37°C; 5% CO2).

CHODHFR and CHODHFR-αvβ3 cell monolayers were exposed to C. pneumoniae elementary bodies and treated for 30 min, before centrifugation, with either MAb against human integrin αvβ3 (MAb LM609; 0.01 ng/ml to 1 μg/ml) or an unspecific Ab (P0399 [Dako]; 10 pg/ml to 1 μg/ml). After centrifugation, the supernatant was replaced with 1.5 ml chlamydia growth medium (treated as described above), and the cell monolayers were cultured for 72 h (37°C; 5% CO2).

C. pneumoniae was detected by indirect immunofluorescence. The monolayers were initially incubated for 2 h with a specific MAb to C. pneumoniae major outer membrane protein (1:50), followed by 1 h of incubation with a secondary fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated Ab (1:100; Dako). Images were taken from four randomly chosen fields for each slide. The numbers of cells and C. pneumoniae IFU were counted for each field by two separate double-blinded observers. Statistical analysis was performed by using the Prism software package (GraphPad; San Diego, CA). Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance with the Neuman-Keuls post hoc test.

Binding of C. pneumoniae to αvβ3 integrin.

Next, 96-well polystyrene enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plates were coated with 100 ng/well of either integrin αvβ3 or bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and were incubated overnight at 4°C. The plates were washed with PBS containing 0.5% Tween 20 (PBS-Tween) and blocked with 200 μl of 1% BSA in Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5] and 150 mM NaCl) containing 0.5 mM CaCl2 and 0.9 mM MgCl2 (blocking buffer) for 2 h at room temperature. C. pneumoniae cells that had been diluted in TBS containing 0.1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM MnCl2, and 0.1% BSA were added; and the plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The plates were washed with PBS-Tween, and 100 μl primary Ab (mouse anti-C. pneumoniae Ab diluted 1:1,500 in blocking buffer) was added to each well. The plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature and washed with PBS-Tween, 100 μl horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (1:1,000 in blocking buffer) was added, and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at room temperature. After this, the mixture was washed with PBS-Tween, the substrate (tetramethylbenzidine) was added, and the mixture was incubated for 5 to 15 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped with 50 μl of 2 M H2SO4, and the plates were read at 450 nm.

C. pneumoniae in vivo infection model.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Committee on Ethics in Animal Experiments of the Italian National Institutes of Health. Male C57BL/J6 mice (age, 6 weeks) were purchased from Charles River (Como, Italy), fed a normal mouse diet ad libitum, housed under biosafety level 2 conditions, and cared for according to the standard and specific procedures outlined by the Italian National Institutes of Health. All mouse experiments were performed under barrier conditions, with sentinel mice monitored by a quality assurance program.

Mice were anesthetized by ether inhalation to induce hyperventilation, and each animal was inoculated intranasally with 106 IFU in 10 μl sucrose phosphate glutamic-acid buffer. Delivery of the inoculum was timed with the inhalation phase of respiration. Mice were divided into three treatment groups: those receiving an injection of normal saline, those receiving an injection of azithromycin (10 mg/kg of body weight/day) plus rifampin (20 mg/kg/day), and those receiving an injection of PEX (2 mg/kg/day). The treatments started 3 days before the C. pneumoniae inoculation, and all animals were injected subcutaneously once a day for 10 consecutive days. The animals were killed on day 7 after C. pneumoniae inoculation. The lungs were removed and were processed for culture and inclusion counting, as described previously (13, 16). The viable count was expressed as the log10 IFU/lung.

Other reagents.

Bovine albumin, azithromycin, and rifampin were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

RESULTS

PEX reduces infection of host HeLa cells.

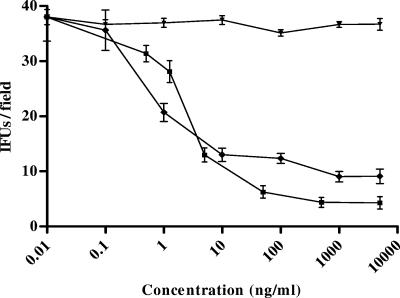

To examine the effect of PEX on C. pneumoniae infection, HeLa cells were exposed to C. pneumoniae (1.5 × 106 IFU) in the presence of increasing concentrations of peptide (0.01 ng/ml to 1 μg/ml). The effect on C. pneumoniae entry and proliferation was evaluated and expressed as the number of IFU/field. For each treatment, four different experiments were performed, and the results are shown as the means ± standard deviations (SDs).

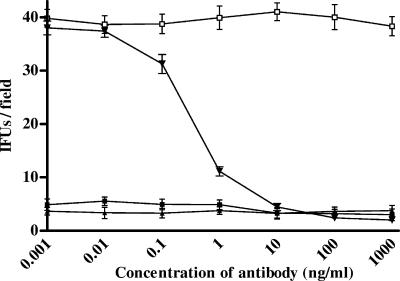

After 72 h, treatment with PEX led to a significant decrease in the number of IFU/field (Fig. 1) in comparison with the number for the untreated control cells or nonspecific peptide-treated cells (maximum inhibitory concentration, 79.43 ± 10.4 ng/ml; 50% maximum inhibitory concentration [IC50], 4.16 ± 2.34 ng/ml; P < 0.001; R2 = 0.981).

FIG. 1.

Inhibitory effects of human PEX and azithromycin on the infectivity of C. pneumoniae. HeLa cells were inoculated with 1.5 × 106 IFU/well and were treated with either human PEX or azithromycin at various concentrations. The number of IFU per field was evaluated. The results of four different experiments are shown (mean ± SD). ⧫, human PEX; ▾, bovine albumin; ▪, azithromycin.

HeLa cells were also exposed to C. pneumoniae in the presence of increasing concentrations of azithromycin; this resulted (Fig. 1) in a significant decrease in the number of IFU/field (maximum inhibitory concentration, 73.32 ± 6.44 ng/ml; IC50, 5.32 ± 3.73 ng/ml; P < 0.001; R2 = 0.989). The results obtained by treating the cells with azithromycin were not significantly different from those achieved by treating the cells with PEX (P > 0.05).

Inhibition of αvβ3 integrin reduces C. pneumoniae infection of host cells.

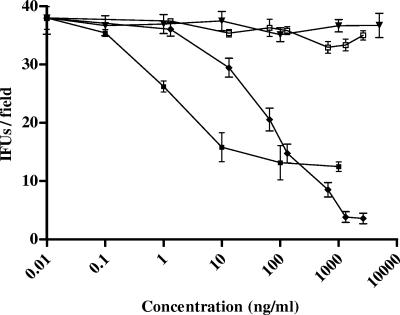

To examine the effect of αvβ3 inhibition on C. pneumoniae entry and proliferation, HeLa cells that tested positive for αvβ3 expression were exposed to C. pneumoniae (1.5 × 106 IFU) in the presence of increasing concentrations of αvβ3 blocking antibodies (0.01 ng/ml to 1 μg/ml). The effect on C. pneumoniae entry into the host cells was evaluated and expressed as the number of IFU/field. For each treatment, four different experiments were performed, and the results are shown as the means ± SDs.

In HeLa cell monolayers, the anti-αvβ3 antibodies inhibited the entry and proliferation of C. pneumoniae in the host cells in a dose-dependent manner. Incubation with anti-αvβ3 antibodies led to a significant decrease in the number of IFU/field (Fig. 2) in comparison with the number for the untreated control cells or nonspecific Ab-treated cells (maximum inhibitory concentration, 0.55 ± 0.21 μg/ml; IC50, 0.43 ± 0.15 μg/ml; P < 0.001; R2 = 0.973).

FIG. 2.

Effect of αvβ3 soluble integrins or αvβ3 integrin-blocking antibodies on C. pneumoniae infection. HeLa cells were inoculated with 1.5 × 106 IFU/well and were treated with either αvβ3 soluble integrins or αvβ3 integrin-blocking antibodies at various concentrations. After 72 h of incubation, the number of IFU per field was evaluated. The results of four different experiments are shown (mean ± SD). ⧫, Ab against αvβ3; □, Dako P0399 aspecific Ab; ▪, soluble integrin αvβ3; ▾, bovine albumin.

To investigate the effect of soluble αvβ3 integrin on the entry and proliferation of C. pneumoniae in host cells, the cells were exposed to bacteria in the presence of increasing concentrations of soluble integrin αvβ3 (0.01 ng/ml to 1 μg/ml). As shown in Fig. 2, this resulted in a significant decrease in the number of IFU/field (maximum inhibitory concentration, 182 ± 15.7 ng/ml; IC50, 13.8 ± 10.2 ng/ml; P < 0.001; R2 = 0.980).

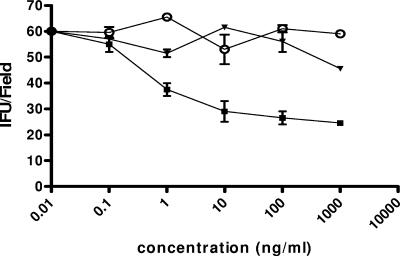

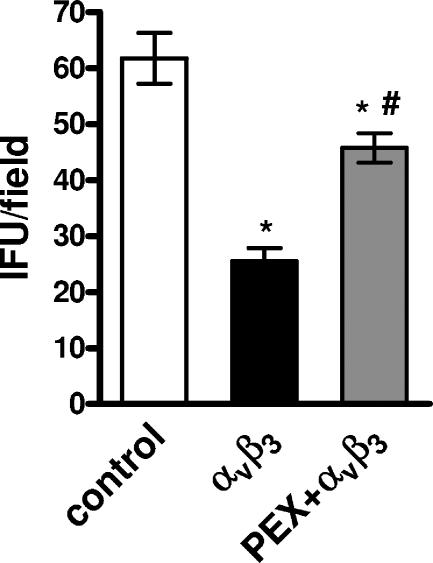

A similar trend was obtained by pretreating elementary bodies with soluble αvβ3 integrin (maximum inhibitory concentration, 97.6 ± 12.3 ng/ml; IC50, 8.92 ± 3.24 ng/ml; P < 0.01; R2 = 0.970) (Fig. 3), while soluble αvβ3 integrin coincubated with PEX was unable to prevent the infection of HeLa cells (for soluble αvβ3 integrin, 25.5 ± 4.65 IFU/field; for soluble αvβ3 integrin coincubated with PEX, 45.75 ± 5.32 IFU/field; P < 0.001; R2 = 0.925) (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

Infection of HeLa cells with C. pneumoniae elementary bodies preincubated with αvβ3 soluble integrins. HeLa cells were inoculated with 1.5 × 106 IFU/well that had been pretreated for 30 min with various concentrations of αvβ3 soluble integrin. After 72 h of incubation, the number of IFU per field was evaluated. The results of four different experiments are shown (mean ± SD). ○, control; ▪, soluble integrin αvβ3; ▾, bovine albumin.

FIG. 4.

Infection of HeLa cells with C. pneumoniae elementary bodies incubated with αvβ3 soluble integrins pretreated with PEX. HeLa cells were inoculated with 1.5 × 106 IFU/well that had been pretreated for 30 min with αvβ3 soluble integrin (100 ng/ml) that had been coincubated with PEX (100 ng/ml). After 72 h of incubation, the number of IFU per field was counted. The results of two experiments are shown (mean ± SD). *, P < 0.001 versus the results for the control; #, P < 0.001 versus the results for αvβ3 soluble integrin; white bars, control; black bars, soluble integrin αvβ3; gray bars, soluble integrin αvβ3 pretreated with PEX.

Infection in CHODHFR cells expressing human αvβ3 integrin.

To explore the specific role of αvβ3 as a receptor of C. pneumoniae, CHODHFR αvβ3-negative and CHODHFR αvβ3-positive cells were exposed to C. pneumoniae and the numbers of IFU/field were evaluated. Four different experiments were performed, and the results are shown as the means ± SDs.

CHODHFR αvβ3-expressing cells were significantly (P < 0.001) more susceptible to C. pneumoniae infection than CHODHFR cells. In fact, the proportion of infected cells in CHODHFR monolayers versus the proportion in CHODHFR αvβ3-transfected control monolayers, evaluated 72 h after infection, was only 8%. C. pneumoniae infection of CHODHFR αvβ3-positive cells was inhibited by increasing concentrations of anti-αvβ3 blocking antibodies (maximum inhibitory concentration, 12.4 ± 8.4 ng/ml; IC50, 2.3 ± 1.1 ng/ml; R2 = 0.99) (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Differential susceptibility to C. pneumoniae infection of CHODHFR and CHODHFR αvβ3-transfected cell monolayers. CHODHFR and CHODHFR αvβ3-transfected cells were inoculated with 1.5 × 106 IFU/well and treated with either αvβ3 integrin-blocking antibodies or aspecific antibodies at various concentrations. After 72 h of incubation, the number of IFU per field was evaluated. These data are representative of those from four similar experiments (mean ± SD). ▪, CHODHFR plus Ab against αvβ3; ▴, CHODHFR plus aspecific Ab; ▾, CHODHFR αvβ3-transfected cells plus Ab against αvβ3; □, CHODHFR αvβ3-transfected cells plus aspecific Ab.

C. pneumoniae binds to αvβ3 integrin.

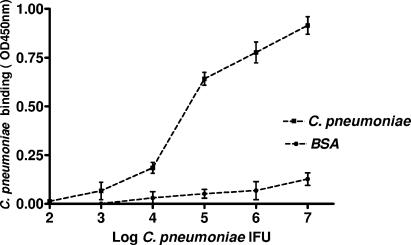

To determine whether C. pneumoniae binds directly to αvβ3 integrin, ELISA plates coated with either αvβ3 integrin or BSA were incubated with increasing amounts of C. pneumoniae, and the amount of the microorganism that bound to each plate was detected.

C. pneumoniae was found to bind to purified integrin αvβ3 in a concentration-dependent manner. This differed significantly (P < 0.001) from the binding observed in BSA-coated wells (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Binding of C. pneumoniae to purified integrin αvβ3. ELISA plates coated with αvβ3 or BSA (100 ng/ml per well) were incubated with increasing amounts of C. pneumoniae IFU. The amount of the microorganism added to the plate is plotted against the optical density at 450 nm (OD450) reading obtained for the bound C. pneumoniae. The arithmetic means and SDs of two independent experiments performed in duplicate are shown. ▪, αvβ3 integrin-coated wells; ▴, BSA-coated wells.

Inhibition of C. pneumoniae infection by systemic administration of PEX in vivo.

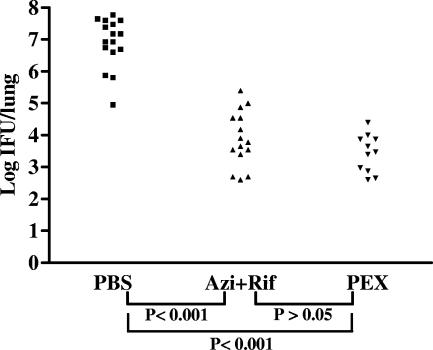

To evaluate the effect of human PEX on C. pneumoniae in vivo infectivity, male C57BL/J6 mice were infected with Chlamydia by intranasal inoculation of 106 IFU of the pathogen. Three days before inoculation, the animals were preventively treated with a systemic injection of either human PEX or an antibiotic. The experiment compared the effect of integrin inhibition by PEX on C. pneumoniae infection with the effects of standard antibiotic regimens. Seven days after C. pneumoniae inoculation, the animals were killed and the number of IFU in each lung was calculated (Fig. 7). All animals belonging to the infected control group, and those treated with vehicle only were positive for C. pneumoniae (16/16 animals). The mean number of IFU/lung for each mouse in this group was 1.89 × 107 (range, 9 × 104 to 6 × 107 IFU/mouse). In total, 15 of the 16 animals treated with a combination of azithromycin plus rifampin were positive for C. pneumoniae. The mean number of IFU/lung for the antibiotic-treated group was 3.37 × 104 (range, 0 to 2.5 × 105 IFU/mouse), which was significantly different (P < 0.001) from that for the vehicle-treated mice. Only 11 of the 16 animals receiving systemic PEX were positive for C. pneumoniae on day 7 after inoculation. The mice belonging to the PEX group showed a lower number of IFU than both the control group and the antibiotic-treated group. The number of IFU/lung in the PEX-treated group was 3.90 × 103 (range, 0 to 2.5 × 104 IFU/mouse), which was not significantly different from that for the antibiotic-treated group.

FIG. 7.

Effect of treatment on isolation of C. pneumoniae by infectivity assay from lung tissue homogenates of infected mice 7 days after infection. Mice (age, 6 weeks) were inoculated with C. pneumoniae (1.0 × 106 IFU/mouse); treated with placebo (PBS; ▪), azithromycin plus rifampin (Azi+Rif; ▴), or PEX (▾); and killed 7 days after inoculation. Negative lungs were considered to have a reading of 0 IFU/lung. Note that each datum point represents one mouse. Data are the sum of two different experiments.

DISCUSSION

Some previous studies have shown that prolonged treatment with antibiotics, such as macrolides or fluoroquinolones, significantly reduces but does not eliminate C. pneumoniae both in vitro and in vivo (11).

Following treatment with moxifloxacin or levofloxacin, eradication rates of only 70 to 80% have been found in adults with culture-documented C. pneumoniae infection (9). Antibiotic therapy, which reduces the bacterial load during the acute phase of chlamydial infections, leads to clinical recovery. Nevertheless, the lack of eradication can be responsible for chronic or latent infections.

New therapeutic approaches are therefore necessary to counteract C. pneumoniae infections and to elucidate the role of this pathogen in the development and/or progression of atherosclerotic plaques or asthma.

For bacterial infection to take place, the adhesion of elementary bodies, which leads to invasion into cells, must occur. This process involves ligand-mediated adhesion of the bacterium, in which a receptor on the host cell surface is bound by a ligand on the bacterial surface. The presence of receptors and ligands leads to bacterial entry into specific tissues (15).

The mechanism of C. pneumoniae entry into host cells is largely unknown (21). In particular, the surface molecules that are responsible for C. pneumoniae attachment and invasion have not been identified, and the reason for the preferential localization of this pathogen within the atherosclerotic plaque is not understood. In the current study, we present experimental evidence that integrins are critically involved in C. pneumoniae infection and that PEX (an MMP fragment with integrin-binding activity) is highly effective against experimental infection by this pathogen.

In our in vitro model, infection of HeLa host cells was inhibited by human PEX. These results were similar to those obtained by treating cells with azithromycin or RGD peptides (data not shown) or with anti-αvβ3 integrin blocking antibodies or soluble αvβ3. In addition, human PEX, which is a ligand for αvβ3 (2, 3), reduces the infection in the lungs of treated animals, decreasing the number of inclusion bodies to an extent comparable to that produced by standard antibiotic treatments.

Thus, the main findings of the present study were that human PEX displayed dose-dependent activity against C. pneumoniae in vitro and, more importantly, was highly effective against this pathogen in an experimental lung infection model.

Moreover, the PEX-mediated inhibition of infection supports the concept that αvβ3 plays a major role in the infectious mechanism of C. pneumoniae. In fact, PEX, which lacks an RGD sequence (2, 3), is a more selective inhibitor of αvβ3 activation and binding than RGD peptides, which block several integrins (19).

Several other integrins are probably involved in the pathogenesis of C. pneumoniae infection in vivo. Here, we focused on αvβ3 integrin, because activation of this surface molecule is involved in atherosclerotic plaque destabilization and progression (1). Our findings demonstrated the specific involvement of αvβ3 in C. pneumoniae infection, as determined by the use of CHODHFR αvβ3-positive and αvβ3-negative cells.

These results suggest that αvβ3 integrin is a key molecule in C. pneumoniae infection. Integrin ligation leads to the activation of both the Ras-PI-3-kinase-Akt pathway and the Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK cascade (22). These two pathways have both been identified as essential in the C. pneumoniae invasion of epithelial cells (5).

A previous paper showed that monoclonal antibodies that bind to the alpha and/or beta 1 subunit of classic integrin receptors on HEC-1B cells were unable to prevent the colonization and infection of epithelial cells by a genital isolate of Chlamydia trachomatis (25). This suggests that the mechanism of entry into the cell by integrins could be specific for C. pneumoniae.

Further studies will be necessary to evaluate the benefit of human PEX in different cellular and animal C. pneumoniae infection models. The activity of PEX should also be tested against other agents, such as adenovirus or B. burgdorferi, both of which are αvβ3 integrin dependent, as they are inhibited by blocking monoclonal antibodies and RGD peptides (4, 24).

Our current objective was not to compare the antichlamydial potencies of PEX and azithromycin. Rather, we aimed to demonstrate that blockage of the αvβ3 receptor with PEX results in a reduction of infection similar to that obtained with a traditional antichlamydial agent, such as azithromycin, even if the mode of action is different.

Moreover, we can speculate that effective preventative agents, such as PEX (or similar, as yet undiscovered drugs), could be combined with antibiotics that act on intracellular bacteria in order to eradicate C. pneumoniae.

In summary, our results highlight a new role of human PEX in C. pneumoniae infection and provide the necessary link by identifying the cell surface binding sites involved. In addition, our findings suggest that human PEX could be used for the treatment of C. pneumoniae infections, as shown by both in vitro and in vivo experiments. This peptide might therefore represent a therapeutic tool for the development of new strategies for the treatment of diseases related to acute or chronic C. pneumoniae infections.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Ministero Ricerca (PRIN-protocol 2003051858_002).

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Fakhri, N., J. Wilhelm, M. Hahn, M. Heidt, F. W. Hehrlein, A. M. Endisch, T. Hupp, S. M. Cherian, Y. V. Bobryshev, R. S. Lord, and N. Katz. 2003. Increased expression of disintegrin-metalloproteinases ADAM-15 and ADAM-9 following upregulation of integrins alpha5beta1 and alphavbeta3 in atherosclerosis. J. Cell. Biochem. 89:808-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bello, L., G. Carrabba, C. Giussani, V. Lucini, F. Cerutti, F. Scaglione, J. Landré, G. Tomei, R. Villani, R. S. Carroll, P. M. Black, and A. Bikfalvi. 2001. Low-dose chemotherapy combined with an antiangiogenic drug reduces human glioma growth in-vivo. Cancer Res. 61:7501-7506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brooks, P. C., S. Silletti, T. L. von Schalscha, M. Friedlander, and D. A. Cheresh. 1998. Disruption of angiogenesis by PEX a noncatalytic metalloproteinase fragment with integrin binding activity. Cell 92:391-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coburn, J., L. Magoun, S. C. Bodary, and J. M. Leong. 1998. Integrins alpha(v)beta3 and alpha5beta1 mediate attachment of Lyme disease spirochetes to human cells. Infect. Immun. 66:1946-1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coombes, B. K., and J. B. Mahony. 2002. Identification of MEK- and phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent signalling as essential events during Chlamydia pneumoniae invasion of Hep2 cells. Cell. Microbiol. 4:447-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galis, Z. S., G. K. Sukhova, R. Kranzhofer, S. Clark, and P. Libby. 1995. Macrophage foam cells from experimental atheroma constitutively produce matrix-degrading proteinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:402-406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaydos, C. A., J. T. Summersgill, N. N. Sahney, J. A. Ramirez, and T. C. Quinn. 1996. Replication of Chlamydia pneumoniae in vitro in human macrophages, endothelial cells, and aortic artery smooth muscle cells. Infect. Immun. 64:1614-1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grayston, J. T., M. B. Aldous, A. Easton, S. P. Wang, C. C. Kuo, L. A. Campbell, and J. Altman. 1993. Evidence that Chlamydia pneumoniae causes pneumonia and bronchitis. J. Infect. Dis. 168:1231-1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammerschlag, M. R., and P. M. Roblin. 2000. Microbiological efficacy of moxifloxacin for the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia due to Chlamydia pneumoniae. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 15:149-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hjelm, E., K. Hulten, C. Nystrom-Rosander, I. Gustafsson, L. Engstrand, and O. Cars. 1997. Assay of antibiotic susceptibility of Chlamydia pneumoniae. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. Suppl. 104:13-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kutlin, A., P. M. Roblin, and M. R. Hammerschlag. 2002. Effect of gemifloxacin on viability of Chlamydia pneumoniae in an in vitro continuous infection model. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49:763-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maass, M., and U. Harig. 1995. Evaluation of culture conditions used for isolation of Chlamydia pneumoniae. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 103:141-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malinverni, R., C. C. Kuo, L. A. Campbell, A. Lee, and J. T. Grayston. 1995. Effects of two antibiotic regimens on course and persistence of experimental Chlamydia pneumoniae TWAR pneumonitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:45-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melnick, S. L., E. Shahar, A. R. Folsom, J. T. Grayston, P. D. Sorlie, S. P. Wang, M. Szklo, et al. 1993. Past infection by Chlamydia pneumoniae strain TWAR and asymptomatic carotid atherosclerosis. Am. J. Med. 95:499-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer, T. F. 1999. Pathogenic neisseriae: complexity of pathogen-host cell interplay. Clin. Infect. Dis. 28:433-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moazed, T. C., C. C. Kuo, T. J. Grayston, and L. A. Campbell. 1997. Murine models of Chlamydia pneumoniae infection and atherosclerosis. J. Infect. Dis. 175:883-890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ouaissi, M. A., J. Cornette, D. Afchain, A. Capron, H. Gras-Masse, and A. Tartar. 1986. Trypanosoma cruzi infection inhibited by peptides modeled from a fibronectin cell attachment domain. Science 234:603-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajalingam, K., H. Al-Younes, A. Müller, T. F. Meyer, A. J. Szczepek, and T. Rudel. 2001. Epithelial cells infected with Chlamydophila pneumoniae (Chlamydia pneumoniae) are resistant to apoptosis. Infect. Immun. 69:7880-7888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruoslahti, E. 1996. RGD and other recognition sequences for integrins. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 12:697-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saikku, P., M. Leinonen, K. Mattila, M. R. Ekman, M. S. Nieminen, P. H. Makela, J. K. Huttunen, and V. Valtonen. 1988. Serological evidence of an association of a novel chlamydia, TWAR, with chronic coronary heart disease and acute myocardial infarction. Lancet ii:983-986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stuart, E. S., W. C. Webley, and L. C. Norkin. 2003. Lipid rafts, caveolae, caveolin-1, and entry by Chlamydiae into host cells. Exp. Cell Res. 287:67-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stupack, D. G., and D. A. Cheresh. 2002. Get ligand, get a life: integrins, signaling and cell survival. J. Cell Sci. 115:3729-3738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas, D. D., J. B. Baseman, and J. F. Alderete. 1985. Fibronectin tetrapeptide is target for syphilis spirochete cytadherence. J. Exp. Med. 162:1715-1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wickham, T. J., P. Mathias, D. A. Cheresh, and G. R. Nemerow. 1993. Integrins alpha v beta 3 and alpha v beta 5 promote adenovirus internalization but not virus attachment. Cell 73:309-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wyrick, P. B., C. H. Davis, and E. A. Wayner. 1994. Chlamydia trachomatis does not bind to alpha beta 1 integrins to colonize a human endometrial epithelial cell line cultured in vitro. Microb. Pathog. 17:159-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]