Abstract

Mutations in the ARGONAUTE gene ZIPPY(ZIP)/AGO7 in Arabidopsis accelerate the juvenile-to-adult transition. A screen for mutations that suppress this precocious phenotype yielded alleles of two auxin-related transcription factors known to be upregulated in zip: ETTIN (ETT)/ARF3 and ARF4. Mutations in ETT/ARF3 and ARF4 delay the expression of adult traits, demonstrating that these genes have non-redundant roles in shoot maturation. ZIP is not generally required for the production of trans-acting (ta) siRNAs, but is required for the production and/or stability of tasiR-ARF, a ta-siRNA that targets both ETT/ARF3 and ARF4. tasiR-ARF is absent in zip-2, and overexpression of a tasiR-ARF-insensitive form of ETT mimics the zip phenotype. We conclude that the precocious phenotype of zip is attributable to the absence of tasiR-ARF-mediated repression of ETT and ARF4. The abundance of tasiR-ARF, ETT/ARF3 and ARF4 RNA does not change during vegetative development. This result suggests that tasiR-ARF regulation establishes the threshold at which leaves respond to a temporal signal, rather than being a component of this signal.

Keywords: siRNA, RNAi, Heterochrony, Arabidopsis

INTRODUCTION

Shoot growth is characterized by the repeated production of lateral organs from the shoot apical meristem. The nature of these organs varies over time, undergoing both gradual and discrete changes in morphology as the plant passes through the juvenile, adult and reproductive phases of development (Kerstetter and Poethig, 1998). This phenomenon is known as ‘heteroblasty’ or ‘phase change’, and is brought about by the intersection of pathways controlling developmental timing and leaf morphogenesis. In Arabidopsis, heteroblasty can be observed in the gradual transition from leaves with long petioles and round, smooth, flat blades to leaves with short petioles and elliptical, serrate, epinastic blades (Telfer et al., 1997). The number of hydathodes per leaf also increases steadily throughout vegetative growth (Hunter et al., 2003; Tsukaya and Uchimiya, 1997), whereas trichome distribution defines discrete phases, with leaves gaining abaxial trichomes at the juvenile-to-adult transition, and losing adaxial trichomes at the adult-to-reproductive transition (Telfer et al., 1997).

Several genes responsible for the temporal control of this process have recently been identified. These include the ARGONAUTE family member ZIPPY (ZIP) (Hunter et al., 2003), the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase RDR6, the plant-specific gene SGS3 (Peragine et al., 2004), the Dicer-like gene DCL4 (Gasciolli et al., 2005; Xie et al., 2005; Yoshikawa et al., 2005), the exportin-5 homolog HASTY (HST) (Bollman et al., 2003; Park et al., 2005; Telfer and Poethig, 1998), and the zinc finger gene, SERRATE (SE) (Clarke et al., 1999; Prigge and Wagner, 2001). Mutations in these genes cause the precocious expression of traits associated with later stages of development; for example, mutations in ZIP, RDR6, SGS3 and DCL4 cause premature leaf elongation, downward curling of the leaf margin, serration, and abaxial trichome production (Gasciolli et al., 2005; Hunter et al., 2003; Peragine et al., 2004; Yoshikawa et al., 2005). All of these genes have roles in the biogenesis of miRNAs or endogenous siRNAs (Allen et al., 2005; Dunoyer et al., 2005; Park et al., 2005; Peragine et al., 2004; Vazquez et al., 2004; Yoshikawa et al., 2005), which strongly suggests that their mutant phenotype can be attributed to the aberrant expression of genes normally repressed by these small RNAs. Expression profiling of zip, rdr6 and sgs3 revealed several genes whose transcripts accumulate in these mutants (Peragine et al., 2004), but which of these upregulated genes, if any, is responsible for their precocious phenotype is still unknown.

We addressed this question using a genetic approach. Assuming that the precocious phenotype of zip is indeed a result of upregulated gene expression, we looked for loss-of-function mutations that suppress this phenotype. Remarkably, this screen produced mutations in the two most-highly upregulated genes in zip, rdr6 and sgs3: ETTIN (ETT/ARF3) and AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 4 (ARF4). ETT and ARF4 are closely related members of the auxin response factor family of transcription factors (Remington et al., 2004; Ulmasov et al., 1999). The first ett mutants were isolated as plants with severely malformed gynoecia: apical-basal defects caused the expansion of the style and stipe at the expense of the ovary, and adaxialization led to the peripheral expansion of central tissues, including the stigma and the transmitting tract (Sessions and Zambryski, 1995). The finding that ETT is expressed abaxially in the developing gynoecium (Sessions et al., 1997) supported its role in establishing abaxial/peripheral tissues. Both ETT and ARF4 have been shown to be expressed during vegetative development: ETT mRNA is present in the shoot apical meristem, leaf primordia, and the margins, vascular bundles and stipules of mature leaves, whereas ARF4 mRNA is expressed in the abaxial domain of leaf primordia and the phloem of mature leaves (Pekker et al., 2005). Plants doubly mutant for ett and arf4 resemble kan1;kan2 double mutants, suggesting that these genes are involved in the specification of abaxial identity (Alvarez et al., 2006; Pekker et al., 2005). However, neither gene has been shown to have an independent vegetative phenotype.

Here, we describe the effect of ett and arf4 on leaf morphology, and their interaction with the ZIP-mediated timing pathway. We show that upregulation of ETT and ARF4 is largely responsible for the vegetative morphology of zip. We further show that the zip phenotype can be attributed to a defect in the production or stability of a transacting (ta) siRNA from the TAS3 locus (tasiR-ARF), which is known to direct the cleavage of the mRNA of these genes (Allen et al., 2005; Williams et al., 2005). The abundance of tasiR-ARF, as well as the ETT and ARF4 mRNAs, does not change significantly during vegetative development. This result is consistent with the mutant phenotype of zip (Hunter et al., 2003), and suggests that tasiR-ARF regulation of ETT and ARF4 transcript levels influences heteroblasty by determining the sensitivity of leaf primordia to a temporal signal, rather than by serving as a component of a developmental clock.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant materials and phenotypic analysis

All mutations were in the Columbia background, unless otherwise indicated. The arf4-2 T-DNA insertion mutation SALK_070506 (Alonso et al., 2003) was obtained from Jason Reed (Chapel Hill, NC). ett-7 was a gift from Patricia Zambryski (Berkeley, CA), and the zip (Ler) T-DNA insertion line (CSH3629) was obtained from the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Plant growth, leaf shape analysis and trichome counts were carried out as described by Peragine et al. (Peragine et al., 2004) and camera lucida tracings were performed as described by Kerstetter et al. (Kerstetter et al., 2001). Leaf length was measured as the distance between the leaf tip and the intersection point of lines drawn tangent to the leaf base. The width of the leaf blade was measured at the midpoint of this line.

Mutant isolation and identification

zip-2 seeds were mutagenized in 0.4% EMS for 6-9 hours prior to planting. Individually harvested M2 families (n=2400) were screened for mutations that suppressed the leaf shape phenoype of zip-2. ett-15 was mapped using the F2 plants from a cross to the zip (Ler) T-DNA insertion line CSH3629, which we obtained from the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Five additional suppressors were classified as ett or arf4 mutations by their failure to complement ett-15 or arf4-2.

RNA analysis

Isolation of low molecular weight RNA, northern analysis, and RLM-5′RACE were carried out as described previously (Yoshikawa et al., 2005). tasiR-ARF was identified on blots of low molecular weight RNA using the locked nucleic-acid oligonucleotide probe: 5′-T(+G)GGG(+T)CTT(+A)CAA(+G)GTCA(+A)GAA-3′.

For RT-PCR, total RNA was isolated from leaves with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and PCR amplification was carried out with the following primers for the analysis of ARF3 and ARF4 expression:

ARF3F, 5′-TGGTCCCAAGAGAAGCAGG-3′;

ARF3R, 5′-TCCACCATCCGAACAAGTG-3′;

ARF4F, 5′-GCCGCTGAAGATTGTTTTGCTC-3′;

ARF4R, 5′-AGTAGATGCCTCCTTGGTTGACC-3′;

EIF4AF, 5′-GCGCATCCTCCAAGCTGGTGTCC-3′; and

EIF4AR, 5′-GGTGGAAGAAGCTGGAATATGTCAT-3′.

The following primers were used for the analysis of splicing defects in arf4 alelles:

Ex1F, 5′-GATGCTATGGTTTCATATTCGTCTCC-3′;

Ex2R, 5′-TGTAGACCTCATCGGTGTCCTTATTAG-3′;

Ex8F, 5′-AACTCTAAATGGAGGTGCTTGTTG-3′;

Ex9R, 5′-GCCTTGGAGATGACTGAATGC-3′;

Ex2F, 5′-CCAGTTGCTTGCTAATAAGGACAC-3′;

Ex3R; 5′-CTTGACCTCTTTCCCCTCCC-3′;

Ex5F; 5′-CTCGTCTCTGGTGATGCGG-3′;

Ex6R; 5′-TCAGGAAGTCCATTTCTTGGC-3′.

ETT overexpression constructs

The ETT open reading frame (ORF) was amplified using primers adding BspHI and BstEII sites to the 5′ and 3′ end of this transcript, respectively (ARF3fBsp, 5′-ATCATGAGCGGTGGTTTAATCGATCTGAACG-3′; ARF3rBst, 5′-TGGTTACCCTAGAGAGCAATGTCTAGCAAC-3′). Addition of the 5′ BspHI site added a Ser residue after the initial Met, but this did not affect the ability of the construct to rescue ett-15. The resulting product was inserted into the T-easy vector (Promega) and used as a template for site-directed mutagenesis using the following oligonucleotides, as described previously (Wang and Malcolm, 1999).

mAf, 5′-CCAGAGGGTCCTGCAGGGACAGGAGATTTTTCCGGG-3′;

mAr, 5′-CCCGGAAAAATCTCCTGTCCCTGCAGGACCCTCTGG-3′;

mBf, 5′-CCATAAGGTCCTGCAGGGACAGGAGACAGTTCCCGCC-3′;

mBr, 5′-GGCGGGAACTGTCTCCTGTCCCTGCAGGACCTTATGG-3′.

The mutated ETTIN ORFs were inserted behind the CaMV 35S promoter in NcoI/BstEII digested pCambia3301, and transformed into Col and ett-15 plants by the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998).

RESULTS

ett and arf4 suppress the zip phenotype

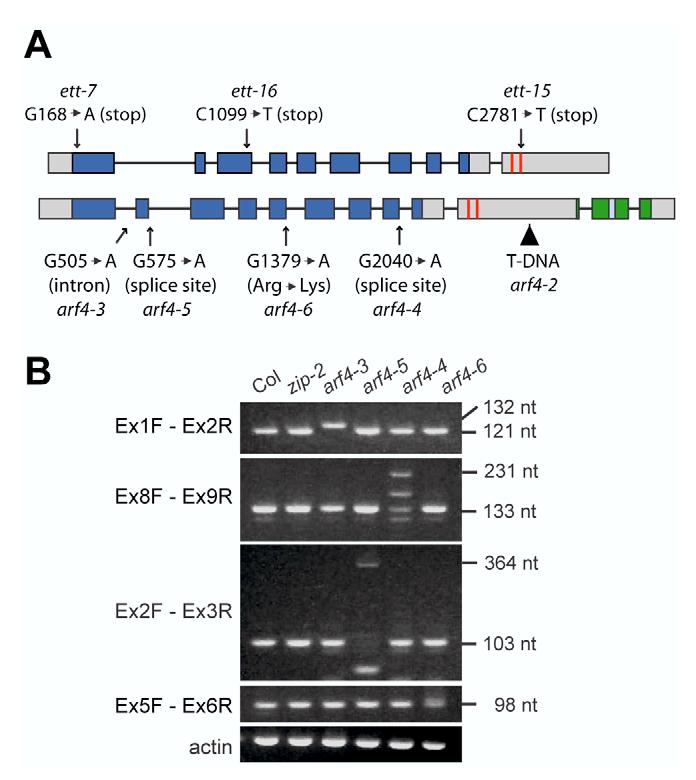

A screen for EMS-induced mutations that suppress the curled, elongated leaf phenotype of the zip-2 deletion yielded six phenotypically similar mutations in two complementation groups. Mutations in the first complementation group mapped near ETT, and failed to complement a strong allele (ett-7) of this gene. One of these mutations (ett-15) is a C to T change that generates a stop codon in the C-terminal region of ETT, and the second (ett-16) is a C to T change that generates a stop codon in the N-terminal region of this gene (Fig. 1A). Mutations in the second complementation group complemented ett-7 but failed to complement a T-DNA insertion (arf4-2) (Pekker et al., 2005) in the closely related gene ARF4. One of these mutations (arf4-3) is located in the middle of the first intron and two others (arf4-4 and arf4-5) are located at splice donor sites (Fig. 1A). All three of these mutations produce transcripts with unspliced introns (Fig. 1B) that introduce stop codons in the ARF4 ORF. arf4-6 is a missense mutation that converts an arginine to a lysine (Fig. 1A,B). Most of the research presented here was conducted with ett-7, a point mutation that generates a stop codon at the extreme N-terminal end of ETT, and arf4-2, a T-DNA insertion near the C-terminal end of ARF4 (Fig. 1A). These mutations were chosen because their phenotype is slightly stronger than the suppressors isolated in our screens.

Fig. 1.

The structure of wild-type and mutant alleles of ETT and ARF4. (A) Genomic structure of ETT and ARF4, and the nature and position of mutant alleles of these genes. Grey box, exon; blue, conserved DNA binding domain; red, tasi-ARF target site; green, domains III and IV; triangle, T-DNA insertion. (B) RT-PCR analysis of ARF4 mRNA in arf4 mutants. PCR amplification was performed with exon primers that flanked the site of the mutation.

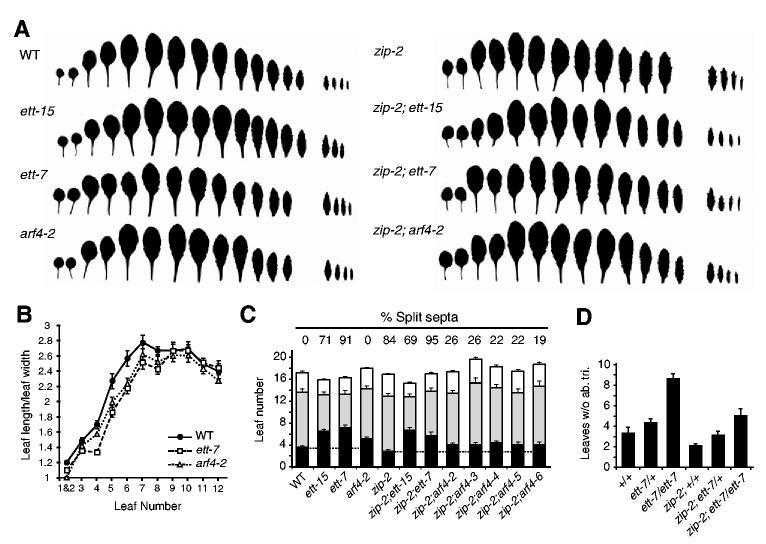

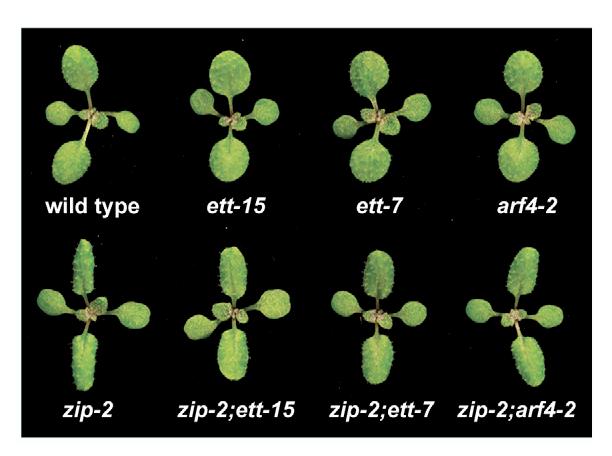

The interaction between zip-2 and ett-7, ett-15 and arf4-2 was studied in F2 families generated by the self-pollination of plants heterozygous for both mutations. The genotype of the plants in these families was determined by PCR, using allele-specific primers. The first two leaves of double mutants are both flatter and rounder than the first two leaves of zip-2 (Fig. 2; Fig. 3A). In zip-2, the length:width (L:W) ratio of these leaves was 1.7, in zip-2;ett-15 and zip-2;ett-7 double mutants it was approximately 1.3, and in zip-2;arf4-2 it was approximately 1.4; this difference in leaf shape was quite obvious and highly significant (n=14; P<0.001). The effect of ett and arf4 mutations on the zip-2 phenotype in subsequent leaves is more subtle, and is most evident at the leaf tip, which is slightly more rounded in double mutants than in zip-2 (Fig. 3A). zip-2;ett-15 and zip-2;ett-16 leaves had unusually short and thick petioles, but this phenotype was not observed in zip-2;ett-7(Fig. 3A). ett-7 and arf4-2 also affect leaf shape in the absence of zip-2 (Fig. 3B). In wild-type plants, the L:W ratio of the lamina increased from a value of 1.3 for leaves 1 and 2, to a value of ≈2.7 for leaf 7 and remained constant for several leaves before declining. ett-7 and arf4-2 produced a significant (n=10; P<0.01) decrease in the L:W ratio of leaves 1-8, but did not affect the morphology of the last several leaves of the shoot. Consistent with this effect, ett and arf4 delayed abaxial trichome production in both the presence and the absence of zip-2 (Fig. 3C,D). On average, zip-2 plants had 2.8±0.3 leaves without abaxial trichomes (compared with 3.5±0.3 in Col). This number was increased to 6.6±0.5 in zip-2;ett-15, to 5.6±0.7 in zip-2;ett-7, and to approximately 4 in zip-2;arf4-2, zip-2;arf4-3, zip-2;arf4-4, zip-2;arf4-5 and zip-2;arf4-6. These mutations produced a slightly greater delay in abaxial trichome production as single mutants, but in most cases this effect was so small that it was not statistically significant (Fig. 3C; data not shown). Interestingly, the trichome phenotype of +/ett-7 was intermediate between that of homozygous mutant and homozygous wild-type plants (Fig. 3D). Although ett mutations that truncate within the DNA-binding domain appear to have dominant-negative activity (Pekker et al., 2005), the stop codon in ett-7 is located at the extreme N terminus of this region, and should therefore eliminate most of this conserved domain. Whether the semi-dominant phenotype of ett-7 results from haploinsufficiency or dominant-negative activity, this result implies that abaxial trichome production is sensitive to the dose of ETT. In summary, these results indicate that ETT and ARF4 promote the expression of at least two juvenile traits - ‘circular/elliptical’ leaf morphology and the absence of abaxial trichomes- and are required for the effect of zip-2 on these traits.

Fig. 2.

ett and arf4 mutations suppress the zip phenotype. Photographs of 11-day-old plants showing the effect of ett-15, ett-7 and arf4-2 on leaf shape. In a wild-type background, these mutations cause a slight rounding and flattening of the first two leaves. In a zip background, they partially suppress the elongation of the lamina and the epinasty that results from the premature expression of adult traits in this mutant.

Fig. 3.

ett and arf4 affect leaf shape and trichome distribution. (A) Successive rosette and inflorescence leaves from wild-type and mutant plants, arranged from the base (left) to the tip (right) of the stem. ett and arf4 suppress the narrow, elongated phenotype of the first two zip leaves. Later leaves of double mutants have rounder tips than zip-2, and the distal portion of the leaf blade is often wider than the proximal portion. ett and arf4 do not affect the serration of the leaf blade. (B) The L:W ratio of the leaf blade of successive leaves of wild-type, ett-7 and arf4-2 plants (n=10 plants of each genotype; ±s.e.m.). In wild-type plants, this ratio increases gradually until leaf 8, after which it remains constant until flowering. ett-7 and arf4-2 cause leaves 4-7 to be slightly rounder than normal. (C) ett-15, ett-7 and arf4-2 increase the number of leaves without abaxial trichomes (black) in both a wild-type and a zip background. This is associated with a compensatory decrease in the number of adult leaves (grey; n≥18, ±s.e.m.). The number of cauline leaves is indicated by the white bar. The numbers above each bar represent the percentage of flowers with a split septum, based on an analysis of the first 10 flowers of five plants of each genotype. ett-15 and arf4 partially suppress the septum splitting observed in zip. Other arf4 mutations also delay abaxial trichome production in a zip-2 background. (D) The number of leaves without abaxial trichomes among plants segregating ett-7 and zip-2. ett-7 has a semidominant effect on abaxial trichome production.

In addition to affecting leaf shape and abaxial trichome production, zip mutations increase hydathode number (Hunter et al., 2003). To determine whether ett-7 also affects this trait, we introduced the hydathode marker E340 (Hunter et al., 2003) into an ett-7 background. ett-7 had no effect on the number of hydathodes on leaves 1 through 7, indicating either that upregulation of ETT is not responsible for this aspect of the zip phentoype, or that hydathode production is regulated redundantly by ETT and ARF4.

zip plants are often semi-sterile because stamen elongation is delayed relative to the elongation of the pistil, and because the septum is usually split near the tip of the carpels (Hunter et al., 2003). ett-7 and ett-15 also cause splitting of the septum, with ett-7 having a much more severe phenotype than ett-15, whereas arf4-2 has no observable carpel phenotype. zip-2;ett-15 and zip-2;arf4-2 double mutants had a lower frequency of septum splitting than did zip-2, suggesting that the effect of zip-2 on septum development is attributable to the increased expression of ETT and ARF4 in this mutant (Fig. 3C). ett-15 had a less significant effect than did arf4, probably because ett-15 causes septum splitting in the absence of zip-2. The fact that septum splitting is associated with both increased expression (in zip-2) and decreased expression (in ett-7 and ett-15) of ETT may reflect the marginal origin of the septum (Liu et al., 2000): marginal outgrowth typically only occurs at the boundary of two distinct cell types, and loss of either cell fate can disrupt this process (Bowman, 2000). Indeed, this effect is consistent with the role of ETT and ARF4 in the promotion of abaxial identity (Pekker et al., 2005).

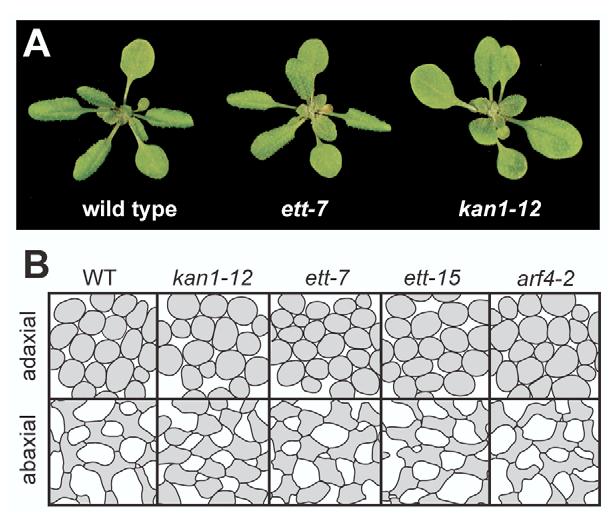

ETT has a non-redundant function in leaf polarity

In contrast to kan1 mutants, which have up-curled or unusually flat leaves (Fig. 4A) (Kerstetter et al., 2001), ett and arf have little or no effect on leaf expansion as single mutants and are therefore thought to have redundant functions in leaf polarity (Pekker et al., 2005). To further explore this theory, we examined the morphology of the mesophyll cells in leaf 6 of wild type, kan1-12, ett-7, ett-15 and arf4-2 (Fig. 4B). Adaxial (palisade) mesophyll cells of wild-type plants are round and tightly packed, whereas abaxial (spongy) mesophyll cells are highly convoluted and have abundant intercellular spaces. kan1-12 has a minor effect on adaxial cell size, but simplifies the morphology of abaxial mesophyll cells and reduces the amount of intercellular space in this tissue, causing it to resemble adaxial mesophyll (Kerstetter et al., 2001). arf4-2 and ett-15 did not have a major effect on mesophyll morphology, but ett-7 produced a noticeable reduction in the irregularity of spongy mesophyll cells. This observation correlates with the observation that ett, but not arf4, can correct the abaxialized phenotype of ANT::KAN2 plants (Pekker et al., 2005). The observation that ett-7 has a more dramatic effect on mesophyll cell shape than ett-15 is consistent with the strength of their floral phenotypes. These results demonstrate that ETT promotes the differentiation of abaxial tissue in the leaf blade, and that this process is more sensitive to the loss of ETT than to the loss of ARF4.

Fig. 4.

ett has an adaxialized phenotype. (A) The morphology of 3-week-old wild-type, ett-7 and kan-12 plants. kan-12 has flat leaves, whereas ett-7 is not dramatically different from wild type. (B) Camera lucida drawings of adaxial and abaxial mesophyll cells of leaf 6 of wild-type and mutant plants. The adaxialized phenotype of kan1-12 is shown for comparison. The phenotype of ett-7 is slightly weaker than that of kan1-12. ett-15 and arf4-2 have a much less significant effect, if any, on the shape of abaxial mesophyll cells.

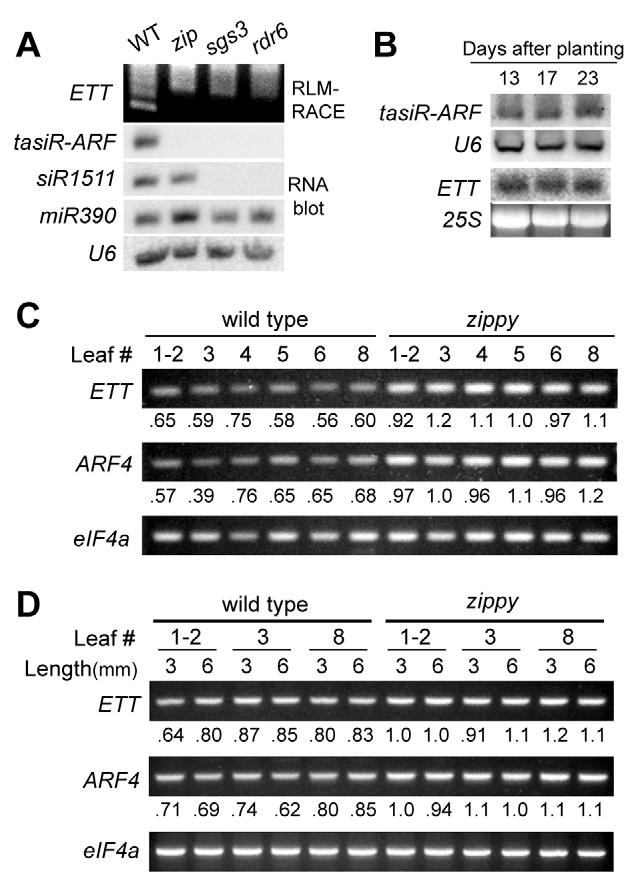

zip upregulates ETT by blocking tasiR-ARF production

The ETT and ARF4 transcripts are targets of a ta-siRNA from the TAS3 locus, tasiR-ARF, and accumulate in mutants that block the production of this ta-siRNA (Allen et al., 2005; Peragine et al., 2004; Williams et al., 2005). Both of these transcripts are also upregulated in zip, and the isolation of loss-of-function mutations of ETT and ARF4 as suppressors of zip suggests that this increase plays a key role in the zip phenotype. The basis for this increase is unclear, however, because zip does not affect the accumulation of any of the siRNAs that have been examined, including ta-siRNAs from the TAS1 and TAS2 loci (Allen et al., 2005; Peragine et al., 2004; Vazquez et al., 2004; Williams et al., 2005; Yoshikawa et al., 2005). Whether ZIP is required for the biogenesis of tasiR-ARF is unknown.

To determine whether ZIP regulates ETT and ARF4 expression via the ta-siRNA pathway, we examined the effect of zip-2 on the expression of tasiR-ARF and mir390, a miRNA that is involved in the biogenesis of tasiR-ARF (Allen et al., 2005). sgs3-11 and rdr6-11 had no effect on the level of miR390, but the level of this miRNA was slightly increased in zip-1. All three mutations dramatically reduced the level of tasiR-ARF and produced a corresponding loss of tasiR-ARF-mediated cleavage of ETT, as revealed by RLM-RACE (Fig. 5A). As expected (Yoshikawa et al., 2005), siR1511 was absent in sgs3-11 and rdr6-11, but present in zip-2. These results suggest that ZIP is required for the biogenesis of siRNAs from TAS3, and also indicate that ZIP either directly or indirectly represses the transcription or biogenesis of the miRNA (miR390) that contributes to the generation of these siRNAs. The observation that sgs3 and rdr6 do not affect miR390 suggests that this effect is not mediated by a ta-siRNA, as SGS3 and RDR6 appear to be generally required for ta-siRNA biogenesis.

Fig. 5.

zip reduces tasiR-ARF levels and increases ETT and ARF4 expression. (A) Northern analysis of zip-2, sgs3-11 and rdr6-11 shows that all three reduce levels of tasiR-ARF, whereas only sgs3 and rdr6 reduce levels of the TAS2 product siR1511. 5′RLM-RACE demonstrates that the reduction in tasiR-ARF correlates with a reduction in the cleavage of the ETT transcript. (B) Northern analysis of tasiR-ARF and ETT RNA at different times in rosette development in continuous light. (C) RT-PCR analysis of ETT and ARF4 RNA from successive 3-mm leaves of wild-type and zip plants grown in short days. zip-2 causes a consistent level of increase in both ETT and ARF4 expression, but both genes are expressed uniformly in successive leaves. The ratio of the signal relative to the loading control eIF4a is shown. (D) RT-PCR analysis of ETT and ARF4 RNA from leaves of wild-type and zip-2 plants grown in continuous light.

Based on its mutant phenotype, we originally suggested that zip acts in a pathway that sets the threshold for the juvenile-to-adult transition, rather that being a component of the developmental ‘clock’ that initiates this transition (Hunter et al., 2003). This hypothesis was based on the observation that zip affects the onset of the juvenile-to-adult transition (e.g. abaxial trichome production, hydathode number) without affecting the number or the character of transition leaves. This is in contrast to mutations, such as hst, which accelerate both the onset of phase change and the rate at which this process occurs (Telfer and Poethig, 1998). To test this hypothesis, we examined the level of tasiR-ARF, ETT and ARF4 at different times in shoot development. Northern analysis revealed that the tasiR-ARF and ARF3 transcripts are present at a relatively constant level during the first three weeks of growth in plants grown in continuous light (Fig. 5B). To obtain a more accurate picture of the expression of ETT and ARF4, we performed semi-quantitative RT-PCR on 3-mm and 6-mm long leaf primordia of leaves 1 through 8 from zip and wild-type plants grown in either short days (Fig. 5C) or continuous light (Fig. 5D). Both transcripts were more abundant in zip than in wild type, and this difference was accentuated in short days. However, in both genotypes, there was no apparent difference in the level of ETT or ARF4 mRNA in successive leaves. These results suggest that tasiR-ARF constitutively represses ETT and ARF4, and they support the hypothesis that ZIP sets the threshold at which leaves respond to a temporal signal (via its effect on the level of ETT and ARF4), rather than by regulating the production of this signal.

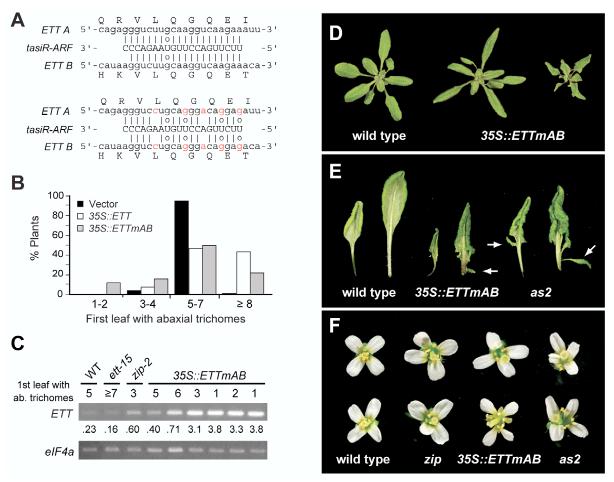

Overexpression of ETT causes zip and as2-like phenotypes

To determine whether ETT upregulation is the primary cause of the zip phenotype, we attempted to phenocopy zip by overexpressing ETT in wild-type plants. For this purpose, we produced transgenic plants expressing a wild-type ETT cDNA, or cDNAs in which both tasiR-ARF target sites (Allen et al., 2005; Williams et al., 2005) were mutated (Fig. 6A), under the regulation of the 35S promoter. The mutations that were introduced in the tasiR-ARF target sites do not affect the amino acid sequence of the protein, but are expected to eliminate or diminish the ability of tasiR-ARF to repress ETT. 35S::ETT produced a lower frequency of morphologically aberrant phenotypes than did 35S::ETTmAB, and also had a less significant effect on abaxial trichome production. Twenty-seven percent of 35S::ETTmAB plants produced abaxial trichomes at an abnormally early position (leaf 1-4), as compared with 8% of plants expressing 35S::ETT (Fig. 6B); furthermore, only 35S::ETTmAB produced plants with abaxial trichomes on leaf 1 or 2. Many plants transformed with either 35S::ETT or 35S::ETTmAB had abnormally late trichomes, presumably reflecting a co-suppression of ETT by these overexpressed transgenes. RT-PCR analysis demonstrated that the severity of the mutant phenotype in 35S::ETTmAB transformants was correlated with the level of ETT expression, and also revealed that many plants that appeared phenotypically normal had equivalent, or higher, levels of ETT than did zip plants (Fig. 6C). This latter result suggests that ARF4, or another as yet unknown target of ZIP, also contributes to the precocious phenotype of zip mutations.

Fig. 6.

Phenotype of plants overexpressing ETT. (A) Sequence of the mutated tasi-ARF target sites in the 35S::ETTmAB construct. The amino acid sequence of ARF3 is unaffected. (B) Abaxial trichome production in primary transformants expressing 35S::ETT (48 plants), 35S::ETTmAB (76 plants) or the empty vector control (101 plants). 35S::ETTmAB produces an increase in the number of plants with precocious abaxial trichomes and with unusually late abaxial trichomes; the latter phenotype mimics the effect of ett mutations and probably results from a co-suppression of ETT. (C) RT-PCR analysis of ETT mRNA in rosettes of wild type, ett-15, zip-2 and ‘wild-type’, zip-like and as2-like primary transgenics expressing 35S::ETTmAB. The ratio of the ETT signal relative to the loading control eIF4a is shown. (D) The phenotypes of 18-day-old plants overexpressing 35S::ETTmAB. Phenotypes ranged from zip-like plants with elongated, curled-down leaves, and 2 or 3 leaves without abaxial trichomes (middle), to more severely affected plants (right) with small tightly-curled leaves, all of which produced abaxial trichomes. The vector control is shown for comparison (left). (E) Leaves of the most severely affected transgenics were tightly in-rolled and extensively lobed, and produced leaflets (arrow) from the petiole. This phenotype became more severe in later leaves, and resembles the phenotype of as2-1 mutants, shown on the right. (F) Flowers from zip-like 35S::ETTmAB plants had short stamens and split septa (top), whereas those from more severely affected plants had narrow, mispositioned petals and sepals, unfused carpels and very short stamens. zip and as2-1 flowers are shown for comparison.

About 16% of the 35S::ETTmAB primary transformants resembled zip in that they had elongated, epinastic leaves and abaxial trichomes on leaf 3 or 4 (Fig. 6D). These plants also resembled zip in having flowers with short stamens and split replums (Fig. 6F). Plants with the highest levels of ETT had a more severe phenotype that was strikingly similar to that of mutations in asymmetric leaves 2 (as2) (Iwakawa et al., 2002; Ori et al., 2000; Semiarti et al., 2001) and blade-on-petiole1 (Ha et al., 2003) (Fig. 6D-F). These plants were very small, with tightly curled, deeply lobed leaves that produced abaxial trichomes starting with leaf 1 or 2. Many leaves also had small leaflets extending from the petiole; this phenotype was apparent on leaf 3 or 4 and became more severe on successive leaves. Petal elongation was delayed in severely affected plants, and fully mature flowers had outwardly curved, irregularly positioned petals (Fig. 6F). These flowers had short stamens that often failed to produce pollen, but had relatively normal carpels with a low frequency of septum splitting.

DISCUSSION

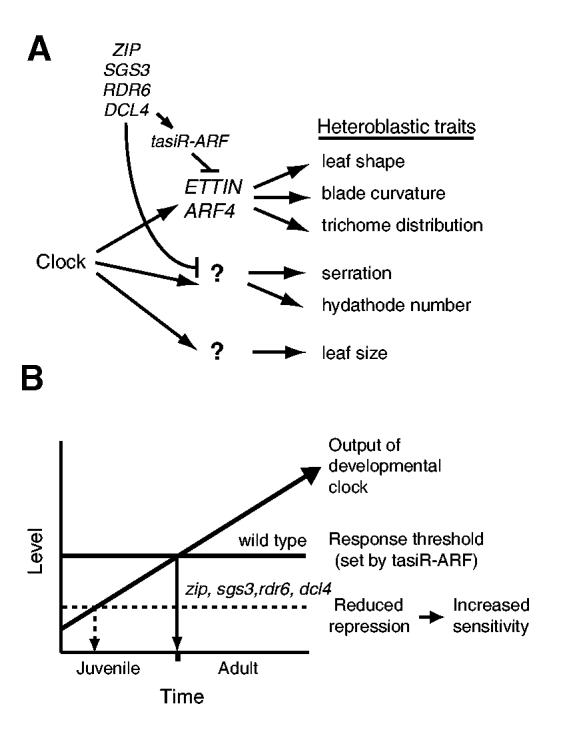

Heteroblasty is regulated by the interaction between a developmental timing mechanism and morphogenetic pathways that respond to this mechanism. The identification of ETT and ARF4 as targets of the heterochronic gene ZIP provides the first insight into how these two processes are connected in Arabidopsis. zip was originally identified as a mutation that altered the threshold for the juvenile-to-adult transition, and encodes ARGONAUTE7, a member of a family of genes with known roles in the processing of small RNAs (Hunter et al., 2003). Here, we show that the increase in ETT and ARF4 expression in zip (Peragine et al., 2004) is a consequence of a reduction in the level of a ta-siRNA from the TAS3 locus, tasiR-ARF, and demonstrate that these transcription factors are responsible for the precocious phenotype of zip. Our results also indicate that tasiR-ARF may act as a temporally constitutive repressor of ETT and ARF4, and that the level of tasiR-ARF determines the sensitivity of leaf primordia to the signal(s) responsible for the temporal variation in leaf morphology.

ETT and ARF4 promote adult leaf traits

ETT and ARF4 have been studied primarily for their role in organ polarity. ett mutations affect both the polarity and number of floral organs (Sessions et al., 1997; Sessions and Zambryski, 1995), and ett;arf4 double mutants have a vegetative phenotype that is characteristic of adaxialized mutants, such as kan1;kan2 or phb-D (Alvarez et al., 2006; Eshed et al., 2004; McConnell and Barton, 1998; Pekker et al., 2005). The discoveries that loss-of-function mutations in ETT and ARF4 partially suppress the phenotype of zip, and that overexpression of ETT in wild-type plants phenocopies zip, demonstrate that overexpression of ETT and ARF4 is largely responsible for the precocious phenotype of zip, and points to a relationship between leaf polarity and heteroblasty.

Many, if not most, heteroblastic aspects of leaf morphology are polarized along either an adaxial-abaxial or proximodistal axis. For example, the increase in leaf epinasty that occurs during rosette development reflects an increase in the growth rate of adaxial tissue relative to the growth rate of abaxial tissue. Similarly, the differential distribution of trichomes on rosette and inflorescence leaves is a consequence of an inherent difference in the developmental potential of the adaxial and abaxial epidermis (Telfer et al., 1997). It is not surprising, therefore, that genes involved in the specification of leaf polarity have a role in heteroblasty. But, while the ability of ett and arf4 to suppress epinasty is readily explained by their adaxialized phenotype, their effect on abaxial trichome production does not have this explanation. Trichomes are absent or less abundant on the abaxial than on the adaxial surface of rosette leaves, and mutations that cause adaxialization, such as kan1-12 (Kerstetter et al., 2001) and phb-D (McConnell and Barton, 1998), typically enhance trichome production on the abaxial leaf surface. The delayed production of abaxial trichomes in ett and arf4 is therefore inconsistent with an adaxialized phenotype. This phenotype may reflect a separable function of these genes, as ett-7 and ett-15 have almost equivalent effects on trichome production despite the much stronger effect of ett-7 on leaf and gynoecium polarity. Similarly, arf4-2 delays abaxial trichome production and affects leaf shape, but has no independent effect on leaf or carpel polarity. Whether the effect of ett and arf4 on leaf shape is linked to their function in leaf polarity or some other developmental pathway is unclear. Whatever the case, the phenotype of these mutations individually and in combination with zip suggests that ETT and ARF4 sit at a branch point in the mechanism of heteroblasty - linking a variety of morphogenetic pathways to one or more temporal regulatory signals (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

A model for temporal regulation of leaf morphology. (A) Heteroblasty is regulated by the interaction between factors that change temporally during shoot development (developmental clocks) and by the pathways controlling leaf morphology. ETT and ARF4 regulate a subset of the traits associated with vegetative phase change and heteroblasty. Their expression is repressed by the tasiR-ARF, the production of which requires ZIP, SGS3, RDR6 and DCL4. Other heteroblastic traits, such as leaf serration and hydathode number, are regulated by another, as-yet-unknown, target of these four genes. (B) Expression of adult traits requires ETT and ARF4. tasiR-ARF creates a threshold for entry into the adult phase by constitutively limiting levels of ETT and ARF4 transcripts. This threshold is lowered by mutations that block tasiR-ARF production (zip, rdr6, sgs3, dcl4). The developmental clock may progress to the adult phase by promoting ETT and ARF4 translation or activity.

How is the activity of ETT and ARF4 regulated? Analyses of RNA levels in wild-type rosette leaves suggest that these genes are constitutively transcribed during vegetative development. Regulation by tasiR-ARF is clearly important, but because the abundance of tasiR-ARF does not change dramatically during vegetative development, this ta-siRNA cannot be a source of temporal information. If their activity is temporally regulated, this regulation must occur post-transcriptionally, and by a mechanism that does not involve tasiR-ARF. ETT has several upstream ORFs in its 5′ UTR that negatively affect the translation of the coding region and appear to affect its activity in flowers (Nishimura et al., 2004). The fact that the ETT transcript is not localized in the leaf (Pekker et al., 2005), despite its clear role in abaxial-adaxial polarity, suggests that ETT is subject to additional levels of regulation during vegetative development as well. In addition to regulation at the level of translation, it is likely that ETT and ARF4 activities are regulated by their interaction with other auxin-related proteins. The floral phenotype of ett can be partially phenocopied by the application of polar auxin transport inhibitors, and ETT is thought to establish boundaries between the stipe, ovary and style in response to auxin levels (Nemhauser et al., 2000). In the absence of auxin, ARF proteins that activate transcription are inhibited by binding to transcriptional repressors of the AUX/IAA family via domains III and IV. Auxin promotes the degradation of AUX/IAA proteins, freeing the ARF protein to promote transcription (Tiwari et al., 2003). However, both ETT and ARF4 have both been shown to act as transcriptional repressors, and ETT lacks domains III and IV and should therefore be incapable of interacting with AUX/IAA proteins (Tiwari et al., 2003; Ulmasov et al., 1999). It will be important to determine whether the activity of ARF4 is regulated by its interaction with AUX/IAA proteins and if ARF4 has a role in the activity of ETT.

Is AS2 a target of the zip pathway?

ETT and AS2 appear to play opposing roles in leaf polarity, with as2 mutants having a weak abaxialized phenotype (Lin et al., 2003; Xu et al., 2003) and ett mutants having a weak adaxialized phenotype. The possibility that these genes may have closely related functions in leaf polarity is suggested by our observation that plants with high levels of ectopic ETT expression strongly resemble as2 mutant plants. This conclusion receives additional support from the report that rdr6 (which upregulates ETT) enhances the as2 phenotype (Li et al., 2005), and the observation that overexpressing AS2 produces a phenotype very similar to that of ett;arf4 double mutants (Lin et al., 2003; Xu et al., 2003). All of these observations are consistent with a model in which ETT and AS2 act to mutually repress the activity of each other. This repression does not appear to take place at a transcriptional level, however. Although rdr6 upregulates ETT and enhances the as2 phenotype, it does not alter AS2 or AS1 expression, nor do as1 and as2 alter the level of the RDR6 transcript (Li et al., 2005). This would suggest that AS2 is not a transcriptional target of ETT or ARF4, and that the interaction of these genes either takes place post-transcriptionally or at a convergent point in their pathways. Alternatively, the phenotype of 35S::ETTmAB may reflect a role for ETT in the repression of BLADE-ON-PETIOLE1 (BOP1), as mutations in BOP1 resemble as2 (Ha et al., 2003).

The role of threshold genes in defining the juvenile-to-adult transition

Two classes of mutations have been identified in screens for mutants with defects in the juvenile-to adult-transition: those that affect the time at which adult traits are first produced without altering the length of the transition zone or the total number of leaves produced by the shoot, and mutations such as hasty (Telfer and Poethig, 1998) and squint (Berardini et al., 2001), which accelerate the appearance of adult traits, nearly completely eliminate transition leaves, and reduce leaf number. zip is an example of the first class of mutations, and we hypothesized that ZIP acts to establish a threshold for entry into the adult phase of development (Hunter et al., 2003). Loss of ZIP lowers this threshold, allowing the shoot to undergo phase change prematurely (Fig. 7B). The evidence that ZIP- and genes (RDR6, SGS3 and DCL4) that have mutant phenotypes identical to zip - is required for the production of tasiR-ARF suggests that this threshold is set by ta-siRNA-mediated repression of ETT and ARF4. Loss of tasiR-ARF regulation in zip, rdr6 and sgs3 mutants, or as a result of introducing target site mutations in ETT (35S::ETTmAB), lowers or bypasses the threshold for entry into the adult phase. Although we did not determine the effect of repressing ETT and ARF4 by overexpressing tasiR-ARF, loss-of-function mutations of these genes produce the expected prolonged juvenile phenotype, supporting the conclusion that the expression level of these genes plays a crucial role in this transition. This conclusion receives further support from the observation that ett-7 has a semi-dominant (i.e. dose-dependent) effect on abaxial trichome production.

The independence of the threshold and clock mechanisms can be seen even in plants with the most severe phenotypes, e.g. ett;arf4 double mutants (Pekker et al., 2005) and severely affected 35S::ETTmAB plants, which still show the gradual changes in leaf morphology indicative of an intact developmental clock. This result is consistent with the phenotype of zip, sgs3, rdr6 and dcl4, and demonstrates that ETT and ARF4 transcript levels are important for leaf identity and morphogenesis, but that subsequent input from a temporal signal is needed to complete the regulation of heteroblasty and phase change.

The function of the RNAi pathway in plants

In plants, RNAi has been studied primarily for its role in virus resistance (Baulcombe, 2004). The evidence that genes required for this process (SGS3, RDR6 and DCL4) also affect vegetative phase change (Gasciolli et al., 2005; Peragine et al., 2004; Xie et al., 2005; Yoshikawa et al., 2005) and salt sensitivity (Borsani et al., 2005) reveal that this regulatory mechanism is involved in a wider array of processes than has previously been recognized. However, mutations in these genes cause relatively subtle phenotypes - particularly in comparison to the highly pleiotropic phenotype of mutations in genes involved in miRNA biogenesis (Schauer et al., 2002). This may be a result of the redundancy in the pathways that produce siRNAs; however, we think this is unlikely because plants doubly mutant for DCL3 and DCL4 - the dicers that generate the vast majority of endogenous siRNAs - resemble sgs3, rdr6 and dcl4 (Gasciolli et al., 2005). Furthermore, although these plants show severe stochastic effects in advanced generations - probably as a result of the reactivation of transcriptionally silenced genes (Gasciolli et al., 2005) - these epigenetic effects cannot be the basis for rapid, reproducible developmental changes and physiological responses. This suggests that RNAi is either employed sparingly to regulate endogenous gene expression, or that only a few of its endogenous targets have important biological functions.

Given that other ARF genes are targets of miRNAs, and that the biogenesis of ta-siRNAs requires miRNA-directed cleavage, it is worth asking why ETT and ARF4 are not direct targets of a miRNA. Is this simply an accident of evolution, or is there something special about ta-siRNA regulation that makes it particularly useful for some types of processes? There is evidence that miRNAs act in a spatially restricted fashion (Alvarez et al., 2006a; Parizotto et al., 2004; Schwab et al., 2006), whereas siRNAs are capable of moving long distances (Dunoyer et al., 2005; Himber et al., 2003; Schwach et al., 2005). Although this makes it tempting to think that ta-siRNAs may act as inducers of phase change (the vegetative equivalent of a ‘florigen’), it is important to remember that ta-siRNAs repress adult development, and do not accumulate (or decline) over the course of development. The analogy may hold, however, in the power of siRNAs to act non-autonomously to coordinate developmental transitions that must take place simultaneously in a broad range of tissues. Mobile siRNAs play an important role in repressing transgene expression throughout a plant, and it is possible that they play a similar role in the regulation of endogenous gene expression. This makes them excellent candidates for establishing a uniform threshold for entry into the adult phase (Fig. 7B). Finding the additional targets of these ta-siRNAs, and understanding their interactions with the developmental clock, are important problems for future research.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Patricia Zambryski for seeds of ett-7, to Jason Reed for seeds of arf4-2 and to the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center for other seed stocks. Stewart Gillmor provided helpful advice.This work was supported by grants from the NIH to R.S.P. and C.H.

Footnotes

Note added in proof

While this paper was under review, evidence that tasiR-ARF is responsible for the morphological phenotype of sgs3, rdr6 and dcl4 was published by Adenot et al., Garcia et al. and Fahlgren et al. (Adenot et al., 2006; Garcia et al., 2006; Fahlgren et al., 2006).

References

- Adenot X, Elmayan T, Lauressergues D, Boutet S, Bouche N, Gasciolli V, Vaucheret H. DRB4-dependent TAS3 trans-acting siRNAs control leaf morphology through AGO7. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:927–932. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen E, Xie Z, Gustafson AM, Carrington JC. microRNA- directed phasing during trans-acting siRNA biogenesis in plants. Cell. 2005;121:207–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso JM, Stepanova AN, Leisse TJ, Kim CJ, Chen H, Shinn P, Stevenson DK, Zimmerman J, Barajas P, Cheuk R, et al. Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science. 2003;301:653–657. doi: 10.1126/science.1086391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez JP, Pekker I, Goldshmidt A, Blum E, Amsellem Z, Eshed Y. Endogenous and synthetic microRNAs stimulate simultaneous, efficient, and localized regulation of multiple targets in diverse Species. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1134–1151. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.040725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baulcombe D. RNA silencing in plants. Nature. 2004;431:356–363. doi: 10.1038/nature02874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berardini TZ, Bollman K, Sun H, Poethig RS. Regulation of vegetative phase change in Arabidopsis thaliana by cyclophilin 40. Science. 2001;291:2405–2407. doi: 10.1126/science.1057144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollman KM, Aukerman MJ, Park MY, Hunter C, Berardini TZ, Poethig RS. HASTY, the Arabidopsis ortholog of Exportin 5/MSN5, regulates phase change and morphogenesis. Development. 2003;130:1493–1504. doi: 10.1242/dev.00362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsani O, Zhu J, Verslues PE, Sunkar R, Zhu JK. Endogenous siRNAs derived from a pair of natural cis-antisense transcripts regulate salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2005;123:1279–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman JL. Axial patterning in leaves and other lateral organs. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2000;10:399–404. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke JH, Tack D, Findlay K, Van Montagu M, Van Lijsebettens M. The SERRATE locus controls the formation of the early juvenile leaves and phase length in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 1999;20:493–501. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunoyer P, Himber C, Voinnet O. DICER-LIKE 4 is required for RNA interference and produces the 21-nucleotide small interfering RNA component of the plant cell-to-cell silencing signal. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:1356–1360. doi: 10.1038/ng1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshed Y, Izhaki A, Baum SF, Floyd SK, Bowman JL. Asymmetric leaf development and blade expansion in Arabidopsis are mediated by KANADI and YABBY activities. Development. 2004;131:2997–3006. doi: 10.1242/dev.01186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahlgren N, Montgomery TA, Howell MD, Allen E, Dvorak SK, Alexander AL, Carrington JC. Regulation of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR3 by TAS3 ta-siRNA affects developmental timing and patterning in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:939–944. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia D, Collier SA, Byrne ME, Martienssen RA. Specification of leaf polarity in Arabidopsis via the trans-acting siRNA pathway. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:933–938. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasciolli V, Mallory AC, Bartel DP, Vaucheret H. Partially redundant functions of Arabidopsis DICER-like enzymes and a role for DCL4 in producing trans-acting siRNAs. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:1494–1500. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha CM, Kim GT, Kim BC, Jun JH, Soh MS, Ueno Y, Machida Y, Tsukaya H, Nam HG. The BLADE-ON-PETIOLE 1 gene controls leaf pattern formation through the modulation of meristematic activity in Arabidopsis. Development. 2003;130:161–172. doi: 10.1242/dev.00196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himber C, Dunoyer P, Moissiard G, Ritzenthaler C, Voinnet O. Transitivity-dependent and -independent cell-to-cell movement of RNA silencing. EMBO J. 2003;22:4523–4533. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter C, Sun H, Poethig RS. The Arabidopsis heterochronic gene ZIPPY is an ARGONAUTE family member. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:1734–1739. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwakawa H, Ueno Y, Semiarti E, Onouchi H, Kojima S, Tsukaya H, Hasebe M, Soma T, Ikezaki M, Machida C, et al. The ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2 gene of Arabidopsis thaliana, required for formation of a symmetric flat leaf lamina, encodes a member of a novel family of proteins characterized by cysteine repeats and a leucine zipper. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002;43:467–478. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcf077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerstetter RA, Poethig RS. The specification of leaf identity during shoot development. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1998;14:373–398. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerstetter RA, Bollman K, Taylor RA, Bomblies K, Poethig RS. KANADI regulates organ polarity in Arabidopsis. Nature. 2001;411:706–709. doi: 10.1038/35079629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Xu L, Wang H, Yuan Z, Cao X, Yang Z, Zhang D, Xu Y, Huang H. The Putative RNA-dependent RNA polymerase RDR6 acts synergistically with ASYMMETRIC LEAVES1 and 2 to repress BREVIPEDICELLUS and microRNA165/166 in Arabidopsis leaf development. Plant Cell. 2005;17:2157–2171. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.033449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin WC, Shuai B, Springer PS. The Arabidopsis LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES-domain gene ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2 functions in the repression of KNOX gene expression and in adaxial-abaxial patterning. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2241–2252. doi: 10.1105/tpc.014969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Franks RG, Klink VP. Regulation of gynoecium marginal tissue formation by LEUNIG and AINTEGUMENTA. Plant Cell. 2000;12:1879–1892. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.10.1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell JR, Barton MK. Leaf polarity and meristem formation in Arabidopsis. Development. 1998;125:2935–2942. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.15.2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemhauser JL, Feldman LJ, Zambryski PC. Auxin and ETTIN in Arabidopsis gynoecium morphogenesis. Development. 2000;127:3877–3888. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.18.3877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura T, Wada T, Okada K. A key factor of translation reinitiation, ribosomal protein L24, is involved in gynoecium development in Arabidopsis. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2004;32:611–613. doi: 10.1042/BST0320611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ori N, Eshed Y, Chuck G, Bowman JL, Hake S. Mechanisms that control KNOX gene expression in the Arabidopsis shoot. Development. 2000;127:5523–5532. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.24.5523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parizotto EA, Dunoyer P, Rahm N, Himber C, Voinnet O. In vivo investigation of the transcription, processing, endonucleolytic activity, and functional relevance of the spatial distribution of a plant miRNA. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2237–2242. doi: 10.1101/gad.307804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MY, Wu G, Gonzalez-Sulser A, Vaucheret H, Poethig RS. Nuclear processing and export of microRNAs in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:3691–3696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405570102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekker I, Alvarez JP, Eshed Y. Auxin response factors mediate Arabidopsis organ asymmetry via modulation of KANADI activity. Plant Cell. 2005;17:2899–2910. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.034876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peragine A, Yoshikawa M, Wu G, Albrecht HL, Poethig RS. SGS3 and SGS2/SDE1/RDR6 are required for juvenile development and the production of trans-acting siRNAs in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2368–2379. doi: 10.1101/gad.1231804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigge MJ, Wagner DR. The Arabidopsis SERRATE gene encodes a zinc-finger protein required for normal shoot development. Plant Cell. 2001;13:1263–1279. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.6.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remington DL, Vision TJ, Guilfoyle TJ, Reed JW. Contrasting modes of diversification in the Aux/IAA and ARF gene families. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:1738–1752. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.039669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer SE, Jacobsen SE, Meinke DW, Ray A. DICER-LIKE1: blind men and elephants in Arabidopsis development. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7:487–491. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(02)02355-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab R, Ossowski S, Riester M, Warthmann N, Weigel D. Highly specific gene silencing by artificial microRNAs in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1121–1133. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.039834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwach F, Vaistij FE, Jones L, Baulcombe DC. An RNA-dependent RNA polymerase prevents meristem invasion by potato virus X and is required for the activity but not the production of a systemic silencing signal. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:1842–1852. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.063537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semiarti E, Ueno Y, Tsukaya H, Iwakawa H, Machida C, Machida Y. The ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2 gene of Arabidopsis thaliana regulates formation of a symmetric lamina, establishment of venation and repression of meristem-related homeobox genes in leaves. Development. 2001;128:1771–1783. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.10.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessions A, Nemhauser JL, McColl A, Roe JL, Feldmann KA, Zambryski PC. ETTIN patterns the Arabidopsis floral meristem and reproductive organs. Development. 1997;124:4481–4491. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.22.4481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessions RA, Zambryski PC. Arabidopsis gynoecium structure in the wild and in ettin mutants. Development. 1995;121:1519–1532. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.5.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telfer A, Poethig RS. HASTY: a gene that regulates the timing of shoot maturation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development. 1998;125:1889–1898. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.10.1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telfer A, Bollman KM, Poethig RS. Phase change and the regulation of trichome distribution in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development. 1997;124:645–654. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.3.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari SB, Hagen G, Guilfoyle T. The roles of auxin response factor domains in auxin-responsive transcription. Plant Cell. 2003;15:533–543. doi: 10.1105/tpc.008417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukaya H, Uchimiya H. Genetic analyses of the formation of the serrated margin of leaf blades in Arabidopsis: combination of a mutational analysis of leaf morphogenesis with the characterization of a specific marker gene expressed in hydathodes and stipules. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1997;256:231–238. doi: 10.1007/s004380050565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmasov T, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ. Dimerization and DNA binding of auxin response factors. Plant J. 1999;19:309–319. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez F, Vaucheret H, Rajagopalan R, Lepers C, Gasciolli V, Mallory AC, Hilbert JL, Bartel DP, Crete P. Endogenous trans-acting siRNAs regulate the accumulation of Arabidopsis mRNAs. Mol. Cell. 2004;16:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Malcolm BA. Two-stage PCR protocol allowing introduction of multiple mutations, deletions and insertions using QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis. Biotechniques. 1999;26:680–682. doi: 10.2144/99264st03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams L, Carles CC, Osmont KS, Fletcher JC. A database analysis method identifies an endogenous trans-acting short-interfering RNA that targets the Arabidopsis ARF2, ARF3, and ARF4 genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:9703–9708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504029102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z, Allen E, Wilken A, Carrington JC. DICER-LIKE 4 functions in trans-acting small interfering RNA biogenesis and vegetative phase change in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:12984–12989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506426102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Xu Y, Dong A, Sun Y, Pi L, Huang H. Novel as1 and as2 defects in leaf adaxial-abaxial polarity reveal the requirement for ASYMMETRIC LEAVES1 and 2 and ERECTA functions in specifying leaf adaxial identity. Development. 2003;130:4097–4107. doi: 10.1242/dev.00622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa M, Peragine A, Park MY, Poethig RS. A pathway for the biogenesis of trans-acting siRNAs in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2164–2175. doi: 10.1101/gad.1352605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]