Abstract

The drug resistances and plasmid contents of a total of 85 vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (VRE) strains that had been isolated in Korea were examined. Fifty-four of the strains originated from samples of chicken feces, and 31 were isolated from hospital patients in Korea. Enterococcus faecalis KV1 and KV2, which had been isolated from a patient and a sample of chicken feces, respectively, were found to carry the plasmids pSL1 and pSL2, respectively. The plasmids transferred resistances to vancomycin, gentamicin, kanamycin, streptomycin, and erythromycin to E. faecalis strains at a high frequency of about 10−3 per donor cell during 4 hours of broth mating. E. faecalis strains containing each of the pSL plasmids formed clumps after 2 hours of incubation in broth containing E. faecalis FA2-2 culture filtrate (i.e., the E. faecalis sex pheromone), and the plasmid subsequently transferred to the recipient strain in a 10-min short mating in broth, indicating that the plasmids are responsive to E. faecalis pheromones. The pSL plasmids did not respond to any of synthetic pheromones for the previously characterized plasmids. The pheromone specific for pSL plasmids has been designated cSL1. Southern hybridization analysis showed that specific FspI fragments from each of the pSL plasmids hybridized with the aggregation substance gene (asa1) of the pheromone-responsive plasmid pAD1, indicating that the plasmids had a gene homologous to asa1. The restriction maps of the plasmids were identical, and the size of the plasmids was estimated to be 128.1 kb. The plasmids carried five drug resistance determinants for vanA, ermB, aph(3′), aph(6′), and aac(6′)/aph(2′), which encode resistance to vancomycin, erythromycin, kanamycin, streptomycin, and gentamicin/kanamycin, respectively. Nucleotide sequence analyses of the drug resistance determinants and their flanking regions are described in this report. The results described provide evidence for the exchange of genetic information between human and animal (chicken) VRE reservoirs and suggest the potential for horizontal transmission of multiple drug resistance, including vancomycin resistance, between farm animals and humans via a pheromone-responsive conjugative plasmid.

Multiple-drug-resistant enterococci, and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) in particular, are a major cause of nosocomial infections. The acquired glycopeptide resistance of VanA has been predominantly identified in Enterococcus faecium isolates (4, 12, 13). In the United States, there is a high incidence of VanA-type E. faecium among human clinical isolates obtained from health care environments (46). Avoparcin has not been approved for use in animal feeds in the United States, and VRE have not been isolated outside health care environments from sources such as healthy human fecal samples or animals (12, 35). In Europe, VanA-type E. faecium isolates are frequently isolated outside the health care environment from materials such as sewage, food, animals, and healthy human fecal samples (4, 35); however, there is a low incidence of VRE among clinical isolates obtained from within the health care environment (35). A major factor that has contributed to the dissemination of VRE in the United States and Europe is now evident. In the United States, it is likely that the excessive use of glycopeptide antibiotics in the health care environment has resulted in the selective increase of VRE in the human intestine (25, 34), which has subsequently been spread by nosocomial transmission. In Europe, it is strongly suggested that the use of avoparcin as a growth promoter in animal feed has resulted in the selective increase of VRE in the human community (27, 49, 52). In both cases, the direct selective pressure of glycopeptides is the largest contributing factor in the selective increase of VRE in the different habitats. Korea, like many European countries, has used avoparcin for 13 years, from 1984 to 1996, as a growth promoter in food animals, including chickens, and VRE have been found in both the health care environment and chicken feces (41). In Korea, vancomycin injections have been used for treatment of infection by β-lactam-resistant gram-positive bacteria, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, since 1992, and VRE are also frequently isolated as nosocomial pathogens from hospitalized patients (42).

Vancomycin resistance can be disseminated both by the clonal spread of resistant enterococci and by the horizontal transmission of the resistance genes. Horizontal transmission of vancomycin resistance can be explained by the fact that the VanA-type determinant is encoded on transposon Tn1546 or a Tn1546-like transposon (2) that frequently resides on a conjugative plasmid in VanA-type E. faecium and that the plasmid is able to transfer by mating on solid surfaces (30). The pheromone-independent pMG1-like conjugative plasmids, which transfer highly efficiently between enterococcal strains during broth mating (28, 47), are commonly found in E. faecium (28, 46). The Tn1546-like transposon is also present on the pMG1-like conjugative E. faecium plasmid (45, 47).

Most pheromone-responsive plasmids are also found in Enterococcus faecalis (10, 15). These plasmids exhibit a narrow host range and transfer between E. faecalis strains at a high frequency (100 to 10−2 per donor cell) within a few hours during broth matings. The plasmids confer a mating response to a small peptide (i.e., a sex pheromone) secreted by potential recipient cells. This mating signal induces the synthesis of a surface aggregation substance that facilitates the formation of mating aggregates. Plasmid-free recipients secrete multiple sex pheromones, each specific for a donor harboring a related pheromone-responsive plasmid. Once a plasmid is acquired by the recipient, secretion of the related pheromone ceases, whereas other unrelated pheromones continue to be produced. Determinants encoded on pheromone-responsive plasmids include those for hemolysin, bacteriocin, and resistance to UV light and antibiotics, including VanA-type resistance (10, 22).

In this report, we show that identical pheromone-responsive plasmids that encode multiple drug resistance, including VanA-type resistance, were isolated from both a hospital patient and a sample of chicken feces.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria, plasmids, media, and antibiotics.

Eighty-five VRE isolates were used in the present study, with 31 (E. faecium, 25; E. faecalis, 6) isolated from hospital patients in Korea between 1998 and 2000 and 54 (E. faecium, 50; E. faecalis, 2; Enterococcus durans, 2) isolated from samples of chicken feces in Korea in 1998. The laboratory strains and plasmids used in the current study are listed in Table 1. The E. faecalis and E. faecium strains were grown in Todd-Hewitt Broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) or N2GT broth (nutrient broth no. 2 [Oxoid Ltd., London, United Kingdom] supplemented with 0.2% glucose and 100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]). The N2GT broth was also used in the sex pheromone experiments. Mueller-Hinton (MH) broth and MH agar were used for the sensitivity disk agar-N (Nissui, Tokyo, Japan) assay to test the MICs of the antibiotics. The agar plates were prepared by adding 1.5% agar to the broth medium.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or phenotype | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strains | |||

| E. faecalis FA2-2 | rif fus | Derivative of JH2 | 11 |

| E. faecalis JH2SS | str spc | Derivative of JH2 | 44 |

| E. faecalis OGIS | str | Derivative of OG1 | 9 |

| E. faecium BM4105RF | rif fus | Derivative of plasmid-free E. faecium BM4105 | 5 |

| Plasmids | |||

| pAD1 | hly/bac uvr | 59.6-kb pheromone-responsive plasmid from E. faecalis DS16 | 11 |

| pMG1 | Gmr | 65.1-kb conjugative plasmid from E. faecium strain | 28 |

| pAM714 | hly/bac erm | pAD1::Tn917; wild-type transfer | 26 |

The antibiotics used in this study were as follows: ampicillin (Ap), chloramphenicol (Cm), erythromycin (Em), fusidic acid, gentamicin (Gm), kanamycin (Km), rifampin, spectinomycin, streptomycin (Sm), tetracycline (Tc), teicoplanin (Tei), and vancomycin (Vcm). To select for transconjugants in the mating experiments, antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: Em, 10 μg/ml; fusidic acid, 12.5 μg/ml; Gm, 125 μg/ml; Km, 500 μg/ml; rifampin, 12.5 μg/ml; spectinomycin, 125 μg/ml; Sm, 500 μg/ml; Tei, 16 μg/ml; and Vcm, 16 μg/ml.

MIC determination.

The MICs of the antibiotics were determined by the agar dilution method according to the CLSI (formerly NCCLS) criteria using MH agar (36).

Mating procedures.

The broth matings were performed as previously described with a donor/recipient ratio of 1:9 (28). Unless otherwise described, the broth mating was carried out for 4 h.

Solid-surface mating was performed on agar plates as described previously (23). In both mating experiments, transconjugants were counted after 48 h of incubation at 37°C. E. faecium BM4105RF and E. faecalis FA2-2 were used as recipient strains in mating experiments with VRE isolates from human and chicken feces.

Pheromone induction.

The detection of aggregation (clumping) was performed as previously described (7, 15, 16). A culture filtrate of plasmid-free FA2-2 was used as the pheromone. Generally, 0.5 ml of pheromone was mixed with 0.5 ml of fresh N2GT broth and 20 μl of the overnight-cultured cells that were to be tested for the ability to respond. The mixtures were cultured for 2 to 4 h at 37°C with shaking and were examined for clumping.

Short mating induced by the pheromone was performed as follows (28). After induction, 0.1 ml of each donor strain was mixed with 0.9 ml of the recipient strain and the mixture was incubated for 10 min at 37°C. The mixture was then plated on selective plates containing the appropriate antibiotics.

Synthetic pheromone (final concentration, 100 ng/ml) in N2GT was used to replace the natural pheromone (culture filtrate of strain FA2-2) in some experiments. The synthetic pheromones were purchased from SAWADY Technology Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan).

Isolation and manipulation of plasmid DNA.

Plasmid DNA was isolated from 5 ml of overnight culture by the alkali lysis method (39). Lysozyme treatment (4 mg/ml for 30 min at 37°C) was performed before alkali lysis. DNA manipulation and analysis of plasmid DNA were carried out by standard protocols (3, 39).

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE).

Lysis of cells in agarose plugs was performed according to the standard protocols (3, 39), except that the cells were treated with lysozyme at a concentration of 20 mg/ml. The reaction mixture for SmaI digestion of whole chromosomal DNA was incubated at 25°C overnight. The gels were electrophoresed with a clamped homogeneous electric field (6V/cm at 15°C for 24 h; Switch times were ramped from 1 to 25 seconds [CHEF-DR II; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, CA]) and then stained with ethidium bromide and photographed with a UV light source.

Southern hybridization.

After agarose gel electrophoresis, DNAs were transferred to a nylon membrane by capillary transfer. Southern hybridization was performed using the digoxigenin-based nonradioisotope system (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Germany), and all procedures were based on the manufacturer's manual and standard protocols (3, 39). Hybridization was performed overnight at 42°C in the presence of 50% formamide. The probes for asa1 and the drug resistance genes were generated by PCR amplification. The nucleotide sequences of the primer pairs are shown in Table 2. PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and purified from the agarose gel blocks with Wizard SV Gel and the PCR Clean-Up System (Promega, Madison, WI). Probes were labeled using a digoxigenin labeling kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH), and signals were detected using a digoxigenin chemiluminescence detection kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH).

TABLE 2.

Nucleotide sequences of PCR primers

| Gene | Primer(s) | Sequence (5′-3′) | Positiona (5′-3′) | Product size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aac(6′)-Ii | AAC6Ii/F | TGGCCGGAAGAATATGGAGA | 73-92 | 410 | 32 |

| AAC6Ii/B | TTTGGTAAGACACCTACG | 482-462 | |||

| ant(4′)-Ia | ANT4Ia/F | GGAAGCAGAGTTCAGCCATG | 180-199 | 266 | 32 |

| ANT4Ia/B | TGCCTGCATATTCAAACAGC | 445-426 | |||

| ant(9′)-Ia | ANT9Ia/F | GGTTCAGCAGTAAATGGTGGT | 103-123 | 476 | 32 |

| ANT9Ia/B | TGCCACATTCGAGCTAGGGTT | 578-557 | |||

| aph(2")-Ic | APH2Ic/F | ATACAATCCGTCGAGTCGCT | 61-80 | 837 | 32 |

| APH2Ic/B | GTTGGCCTTATCCTCTTCCA | 897-878 | |||

| aac(6′)-aph(2") | AAC6APH2/F | TGATGATTTTCCTTTGATGT | 45-64 | 1,395 | This study |

| AAC6APH2/B | CAATCTTTATAAGTCCTTTT | 1439-1420 | |||

| aph(3′)-IIIa | APH3/F | GCCGATGTGGATTGCGAAAA | 454-473 | 292 | 48 |

| APH3/B | GCTTGATCCCCAGTAAGTCA | 745-726 | |||

| ant(6′)-Ia | ANT6/F | ACTGGCTTAATCAATTTGGG | 179-208 | 597 | 48 |

| ANT6/B | GCCTTTCCGCCACCTCACCG | 775-756 | |||

| ermB | ermB-1/F | CGAAATTGGAACAGGTAAAG | 102-121 | 546 | This study |

| ermB-2/B | TTCATTGCTTGATGAAACTG | 647-631 | |||

| asa1 | asa1-5/F | GGTGTGTTAGGAGTTGTAGG | 85-104 | 1,115 | This study |

| asa/B | ATTCCATAGACAATTGTGGC | 1199-1180 | |||

| vanA (Tn1546) | VanA-1 | GCATGGCAAGTCAGGTG | 7272-7288b | 1,114 | This study |

| X-2 | GATCAATGGCACTGCCGCG | 8385-8367b | |||

| ORF1 (Tn1546) | ORF1B1 | CGTCCTGCCGACTATGATTATTT | 1913-1891b | 23 | |

| vanX (Tn1546) | X-1 | GTAGGGACATACGAGTTGGC | 8136-8155b | This study | |

| vanY (Tn1546) | Y-REV1 | CCATATATTCCTCGAGAACG | 9769-9750b | This study | |

| orfx (Tn5405) | ORFX-6/F | ATGGTAGATAATATTATTAAATCAGTAG | 1-28 | This study | |

| δ (pMD101) | uk-14/F | CGCTTGGCGTTGGTACAG | 502-485 | This study | |

| γ (pMD101) | orf1-4/B | ATGAGTACAGTTATTTTAGCTG | 1-22 | This study |

The positions given are from the first base of the coding sequences of the genes.

The positions given are from the first base of the left inverted repeat of Tn1546.

PCR and specific primers.

The sets of specific primers used in PCR amplification are listed in Table 2. A TaKaRa Taq (TAKARA BIO Inc., Shiga, Japan) and a Thermal Cycler Model 9600 (Perkin-Elmer, Wellesley, MA) were used for the PCRs unless otherwise stated. Long PCR was performed using an Expand Long Template PCR System (Roche Diagnostics GmbH) and a Thermal Cycler Model 9600 (Perkin-Elmer).

DNA sequencing and computer analysis.

The DNA fragments to be sequenced were amplified by long PCR, separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, and purified from the agarose gel block as described above. The PCR products purified from the agarose gel blocks were sequenced directly by the primer-walking method (33). The sequencing reactions were conducted by PCR using a Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing FS Ready Reaction Kit (Perkin-Elmer), and the sequences were determined using an ABI Prism 310 sequencer (Perkin-Elmer). For sequencing of the region containing the drug resistance determinants, two fragments containing ant6, aph3, ermB, and part of open reading frame 1 (ORF1) of Tn1546 were amplified using two sets of primers (ANT6/F and ermB-2/B; ermB-1/F and ORF1B1). The DNA sequences of the two fragments were determined as described above. Based on the sequences obtained and the sequences of homologous genes found in the database, which were expected to lie in the flanking region, three sets of primers (ORFX-6/F and ANT6/B; uk-14/F and Y-REV1; X-1 and orf1-4/B) were designed and used for the amplification of the flanking regions by long PCR. The PCR products were purified, and the DNA sequences were determined by primer walking (33). A homology search using BLAST was performed through the NCBI website (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Tools/index.html).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence data reported here have been deposited in the DDBJ, EMBL, and GenBank nucleotide sequence databases under accession number AB247327.

RESULTS

Drug resistance VRE isolates.

Eighty-five VRE isolates, 54 of which had been obtained from samples of chicken feces and 31 from hospital patients in Korea, were examined for drug resistance. All of the isolates were resistant to more than four drugs, except for one E. faecalis isolate that showed resistance only to vancomycin (data not shown). Of the 85 VRE isolates, the numbers and percentages of 83 strains of E. faecium and E. faecalis resistant to the drugs tested are shown in Table 3. The isolation frequencies of gentamicin- and kanamycin-resistant E. faecium strains from chicken fecal samples were lower than those of E. faecium and E. faecalis strains from other sources. The two E. faecalis strains from chicken feces showed multiple resistances to Cm, Em, Gm, Km, Sm, Tei, and Vcm, suggesting that the resistances might be encoded on a plasmid.

TABLE 3.

Antimicrobial drug resistances of VRE

| Drug | No. of drug-resistant isolates (%)a

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

E. faecium

|

E. faecalis

|

|||

| From chicken (nb = 50) | From human (n = 25) | From chicken (n = 2) | From human (n = 6) | |

| Ap | 26 (52) | 24 (96) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Cm | 3 (6) | 7 (28) | 2 (100) | 1 (17) |

| Em | 43 (86) | 24 (96) | 2 (100) | 5 (83) |

| Gm | 0 (0) | 20 (80) | 2 (100) | 4 (67) |

| Km | 1 (2) | 21 (84) | 2 (100) | 4 (67) |

| Sm | 50 (100) | 23 (92) | 2 (100) | 1 (17) |

| Tc | 50 (100) | 14 (56) | 1 (50) | 3 (50) |

| Tei | 50 (100) | 16 (64) | 2 (100) | 3 (50) |

| Vcm | 50 (100) | 25 (100) | 2 (100) | 6 (100) |

The numbers in parentheses indicate the percentages of resistant isolates. The drug resistance levels (MICs) of ampicillin, chloramphenicol, erythromycin, gentamicin, kanamycin, streptomycin, tetracycline, teicoplanin, and vancomycin were equal to or greater than 8, 32, 16, 64, 1,024, 512, 8, 16, and 64 μg/ml, respectively.

n, number of strains tested.

Plasmids of VRE isolates.

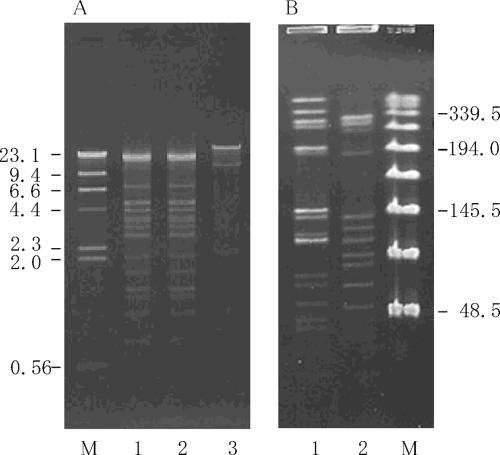

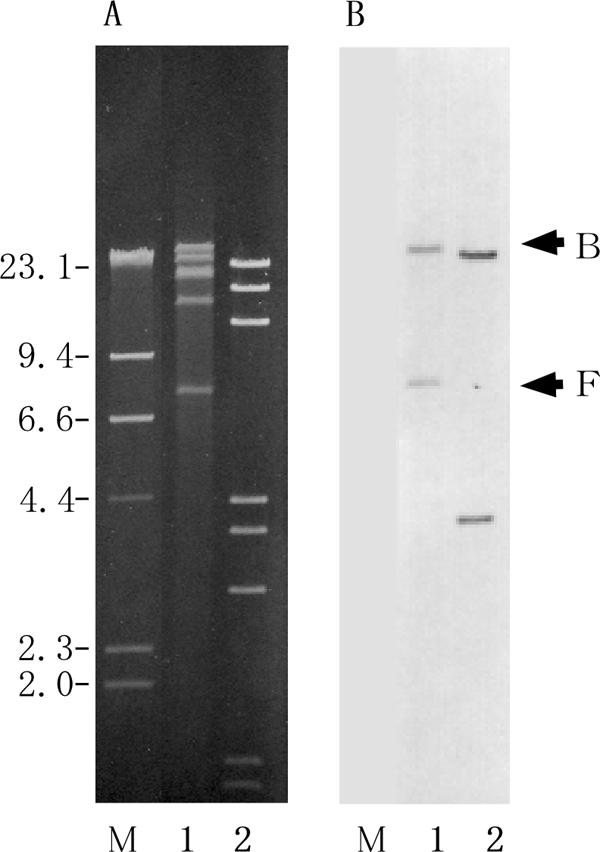

Plasmid DNA was prepared from each of the 85 VRE isolates and digested by EcoRI. The digested plasmid DNAs were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis, and the restriction fragment patterns were compared. Of these VRE isolates, E. faecalis KV1 and E. faecalis KV2, which were isolated from a patient and from a sample of chicken feces, respectively, were found to harbor similar (indistinguishable and apparently identical) plasmids with respect to the EcoRI restriction profile (Fig. 1A). The two strains showed the same drug resistance levels (MICs) to vancomycin (1,024 μg/ml), teicoplanin (128 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (>512 μg/ml), gentamicin (>512 μg/ml), streptomycin (>512 μg/ml), kanamycin (>512 μg/ml), and erythromycin (64 μg/ml), but KV1 also showed resistance to tetracycline (128 μg/ml).

FIG. 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of EcoRI-digested plasmid DNAs and PFGE of SmaI-digested total DNA from KV strains. (A) Agarose gel electrophoresis of EcoRI-digested plasmid DNA isolated from KV strains. Lanes: M, HindIII-digested λ DNA; 1, KV1; 2, KV2; 3, pMG1. (B) PFGE of SmaI-digested total DNAs from KV strains. Lanes: 1, KV1; 2, KV2; M, Lambda ladder PFG Marker (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA). The numbers on the right and left indicate the sizes of molecular markers in kilobase pairs.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis was performed on the SmaI-digested total DNAs. As shown in Fig. 1B, the SmaI-digested patterns for the total DNAs were different, suggesting the presence of the same plasmid in different host strains.

Conjugal transfer of drug resistance.

The transferability of vancomycin resistance from each of the two strains to E. faecalis FA2-2 or E. faecium BM4105RF was examined by broth mating for 4 hours. The transconjugants were selected on agar plates containing 16 μg/ml of vancomycin for the selection of the transconjugant and 12.5 μg/ml of rifampin and 12.5 μg/ml of fusidic acid for counterselection of the donor strain. The vancomycin resistance was transferred to E. faecalis FA2-2 at a frequency of about 10−3 per donor cell and was not transferred to E. faecium BM4105RF at a detectable frequency (less than 10−8 per donor cell) (Table 4). The transconjugants exhibited resistance to vancomycin, teicoplanin, gentamicin, streptomycin, kanamycin, and erythromycin. Repeated transfer experiments were performed between E. faecalis FA2-2 and E. faecalis JH2SS (Table 4). The vancomycin resistance was transferred at a frequency of about 10−3 per donor cell between these strains, and the transconjugants obtained in each experiment also exhibited resistance to vancomycin, teicoplanin, gentamicin, streptomycin, kanamycin, and erythromycin, suggesting that the conjugative plasmids conferred these drug resistances.

TABLE 4.

Transfer frequencies of pSL plasmids in Enterococcus

| Donor | Recipient | Transfer frequency (no. of transconjugants per donor cell)a |

|---|---|---|

| KV1 | E. faecium BM4105RF | <10−8 |

| KV1 | E. faecalis FA2-2 | 7 × 10−3 |

| KV2 | E. faecium BM4105RF | <10−8 |

| KV2 | E. faecalis FA2-2 | 4 × 10−3 |

| E. faecalis FA2-2 (pSL1) | E. faecalis JH2SS | 1 × 10−3 |

| E. faecalis FA2-2 (pSL2) | E. faecalis JH2SS | 2 × 10−3 |

| E. faecalis JH2SS (pSL1) | E. faecalis FA2-2 | 8 × 10−4 |

| E. faecalis JH2SS (pSL2) | E. faecalis FA2-2 | 7 × 10−4 |

Overnight cultures of 0.05 ml of donor and 0.45 ml of recipient were added to 4.5 ml of fresh N2GT, and the mixtures were incubated at 37°C with gentle agitation for 4 h. Portions of the mixed cultures were then plated on solid media with appropriate selective antibiotics. Colonies were counted after incubation for 48 h at 37°C.

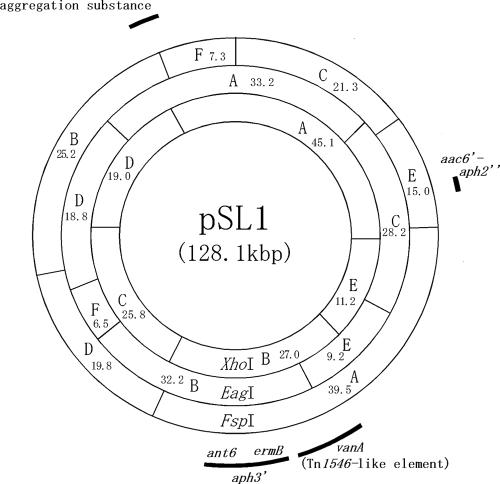

Plasmid DNA was isolated from each of the wild-type strains and the E. faecalis FA2-2 transconjugant. The plasmid DNA was digested with EcoRI and examined by agarose gel electrophoresis. The plasmid DNAs isolated from each of the strains were identical with respect to the EcoRI restriction profiles obtained by agarose gel electrophoresis analysis. These data suggested that each of the wild-type strains harbored a single drug resistance plasmid and that the plasmid had transferred to the recipient strain. The plasmid DNAs isolated from the transconjugant, which was derived from each of the wild-type strains, E. faecalis KV1 and KV2, were designated pSL1 and pSL2, respectively. The restriction map of the pSL1/pSL2 plasmid was determined by agarose gel electrophoresis of the restriction fragments. Each of the plasmid DNAs was digested with XhoI, EagI, or FspI or double digested with XhoI and EagI, XhoI and FspI, or EagI and FspI. Agarose gel electrophoresis analysis of the digested DNAs was performed to determine the cleavage sites within the plasmid. The physical maps of pSL1 and pSL2 were identical, and the molecular size of each of the plasmids was 128.1 kb (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Physical map of pSL plasmids. The fragments produced by the restriction endonuclease digestion of pSL plasmid DNA are denoted by letters. The numbers indicate the sizes of the fragments in kilobase pairs. The arcs indicate the approximate regions of the antibiotic resistance determinants and aggregation substance gene.

Pheromone responses of pSL1 and pSL2.

The mating mixture of the donor strain, E. faecalis JH2SS harboring pSL1 or pSL2, and the recipient strain, E. faecalis FA2-2, formed a mating aggregate, and vancomycin resistance transferred efficiently to the recipient strain at a frequency of about 10−3 per donor cell during 4 h of broth mating (Table 4). Pheromone inductions and mating experiments were performed as described in Materials and Methods to examine the E. faecalis pheromone responses of pSL1/pSL2. The donor cells of E. faecalis JH2SS carrying pSL1 or pSL2 and E. faecalis OG1S carrying pSL1 or pSL2 were exposed for 2 hours to an FA2-2 culture filtrate (i.e., pheromone) to induce aggregation-mating functions before a short (10-min) mating period. The short mating was carried out between the induced or uninduced donor cells and the plasmid-free recipient E. faecalis FA2-2. Transconjugants were selected on agar plates containing vancomycin, rifampin, and fusidic acid. The transfer frequency of vancomycin resistance from the induced donor cells was about 10−4 per donor cell, and that from the uninduced donor cells was less than 10−8 per donor cell, indicating that plasmids pSL1 and pSL2 conferred a pheromone response (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Transferability of pSL plasmids during 10-min mating after exposure to the E. faecalis pheromonea

| Donor | Recipient | Exposure to pheromoneb | Transfer frequency in 10-min mating (no. of transconjugants per donor cell) |

|---|---|---|---|

| JH2SS (pSL1) | FA2-2 | +c | 7 × 10−5 |

| − | <10−8 | ||

| JH2SS (pSL2) | FA2-2 | +c | 2 × 10−4 |

| − | <10−8 | ||

| JH2SS (pAM714) | FA2-2 | +c | 4 × 10−4 |

| − | <10−8 | ||

| JH2SS (pSL1) | FA2-2 | cAD1d | <10−8 |

| cPD1d | <10−8 | ||

| cCF10d | <10−8 | ||

| cOB1d | <10−8 | ||

| cAM373d | <10−8 | ||

| JH2SS (pSL2) | FA2-2 | cAD1d | <10−8 |

| cPD1d | <10−8 | ||

| cCF10d | <10−8 | ||

| cOB1d | <10−8 | ||

| cAM373d | <10−8 |

For induction with the pheromone, 0.1 ml of an overnight culture of the donor strain was diluted with 0.9 ml of a 1:1 mixture of pheromone and fresh N2GT broth. The overnight culture was similarly diluted with N2GT broth without induction as a control. Each culture was incubated for 2 hours with gentle agitation at 37°C. After induction, 0.1 ml of each donor strain was mixed with 0.9 ml of the recipient strain, and the mixture was incubated for 10 min at 37°C. The mixture was plated on selective plates.

+, exposed; −, not exposed.

Culture filtrate of FA2-2 was used as the pheromone.

N2GT with a synthetic pheromone was used as the pheromone. The final concentration of synthetic pheromone was 100 ng/ml.

The pheromone induction and mating experiments were performed with the synthetic pheromones cAD1, cPD1, cCF10, cOB1, and cAM373 to determine the specific pheromone for plasmids pSL1 and pSL2. Plasmids pSL1 and pSL2 did not respond to any of the synthetic pheromones, suggesting that pSL1 and pSL2 differed from the pheromone-responsive plasmids pAD1, pPD1, pCF10, pOB1, and pAM373 with respect to their pheromone responses (Table 5). The pheromone specific for pSL plasmids has been designated cSL1.

DNA-DNA hybridization.

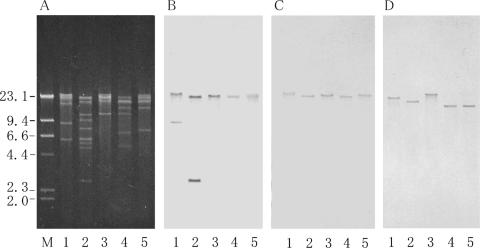

Of the pheromone-responsive plasmids that have been studied, the pheromone-related conjugative systems for pAD1 (8, 19), pCF10 (17, 18), and pPD1 (20, 43) have been well characterized. The genes involved in the regulation of the pheromone response have been identified and are known to be clustered in a 7-kb region on each plasmid (20, 31), and there is gene homology between the plasmids (20, 24). There is also homology between the genes for the aggregation substance, which are located downstream of the regulatory region (20, 21). The 7-kb regulatory region contains genes for surface receptor binding to exogenous pheromone; a positive regulator for the expression of tra genes, including aggregation substance; and a negative regulator that represses the expression of the positive regulator in the absence of pheromone and derepresses it in the presence of the imported exogenous pheromone. The N-terminal region of the aggregation substance gene asa1 of pAD1 was amplified by PCR using specific primers (Table 2), and the amplified fragment was used as a probe for Southern hybridization with pSL1 or pSL2 DNA. The DNA fragment hybridized to specific restriction fragments from pSL1 and pSL2 (Fig. 3). These results indicate that pSL1 and pSL2 contain sequences that are homologous with the consensus sequence found in the aggregation substance gene of the pheromone-responsive plasmids.

FIG. 3.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of pSL plasmid digested with restriction endonuclease and hybridization with asa1 probe. (A) Agarose gel electrophoresis of endonuclease-digested plasmid DNAs. (B) The gel was Southern blotted and hybridized with the asa1 probe. Lanes: 1, FspI-digested pSL1 DNA; 2, EcoRI-digested pAD1 DNA. Arrows B and F on the right indicate the FspI fragments B and F of pSL1, respectively, which hybridized to the asa1 probe. The numbers on the left indicate the positions and sizes in kilobase pairs of the λ HindIII molecular size markers.

The pSL plasmids were studied for homology with the pheromone-responsive plasmids pAD1 and pPD1 and the pheromone-independent plasmid pMG1 (28) by Southern hybridization. Both the pSL1 and pSL2 DNA probes hybridized to a restriction fragment of pAD1 and pPD1 DNA (data not shown), whereas the plasmid DNA probe did not hybridize with any restriction fragments of pMG1 DNA (data not shown). These findings indicated that the pSL plasmids contained sequences homologous with those of the pheromone-responsive plasmids and that they did not contain any sequences homologous with the pheromone-independent plasmid pMG1.

Drug resistance determinant.

The drug resistance determinants carried on the plasmids pSL1 and pSL2 were examined by PCR analysis. Specific PCR primers for the drug resistance determinants for vancomycin, gentamicin, streptomycin, kanamycin, and erythromycin were designed based on database sequences (Table 2). The plasmids pSL1 and pSL2 conferred high levels of resistance to vancomycin and teicoplanin (MICs, 1,024 μg/ml and 128 μg/ml) and gave rise to the expected 1,114-bp PCR product with the primer specific for the vanA gene, indicating that pSL1 and pSL2 encoded a VanA-type determinant.

Primers specific for the aminoglycoside modification enzyme genes were used to identify the aminoglycoside determinant (Table 2). Plasmids pSL1 and pSL2 gave rise to the expected PCR products with the primers specific for aac(6′)-aph(2"), ant(6)-Ia, and aph(3′)-IIIa, which encode gentamicin/kanamycin, streptomycin, and kanamycin resistance, respectively. Plasmids pSL1 and pSL2 gave rise to the expected PCR product with the primer specific for ermB, which encodes erythromycin resistance. The most commonly acquired macrolide resistance mechanism among the enterococci is the production of methylases for an adenine residue in the 23S ribosome RNA of the 50S ribosomal subunit, which is encoded by the ermB gene (37, 40).

The PCR products amplified with the specific primers for each resistance gene were purified from the agarose gel and used as Southern hybridization probes to examine their approximate locations on the restriction map. The results are shown in Fig. 2 and 4. The aac(6′)-aph(2") genes hybridized to the FspI E fragment, EagI C fragment, and XhoI A fragment; the vanA gene hybridized to the FspI A fragment, EagI B and E fragment, and XhoI B fragment; and the ant(6)-Ia gene, aph(3′)-IIIa gene, and ermB gene hybridized to the FspI A fragment, EagI B fragment, and XhoI B fragment (Fig. 4). These data implied that vanA, ant(6)-Ia, aph(3′)-IIIa, and ermB, which encode VanA, streptomycin, and kanamycin, and erythromycin resistance, respectively, are located between 53 kb (an XhoI site between XhoI fragments B and E) and 74 kb (an FspI site between FspI fragments A and D) of the pSL maps (Fig. 2). aac(6′)-aph(2"), which encodes gentamicin/kanamycin resistance, was located in the FspI E fragment of the pSL plasmids.

FIG. 4.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of restriction endonuclease-digested pSL plasmid DNAs and Southern hybridization with drug resistance genes. (A) Agarose gel electrophoresis of endonuclease-digested pSL plasmid DNAs. Lanes: 1, EagI digestion; 2, EagI/XhoI double digestion; 3, XhoI digestion; 4, XhoI/FspI double digestion; 5, FspI digestion. The gels were run in triplicate and then Southern blotted and hybridized with a vanA probe (B), aph3 probe (C), or aac6/aph2 probe (D). The numbers on the left indicate the positions and sizes in kilobase pairs of the λ HindIII molecular size markers.

DNA sequence analysis of drug resistance determinants and their flanking regions.

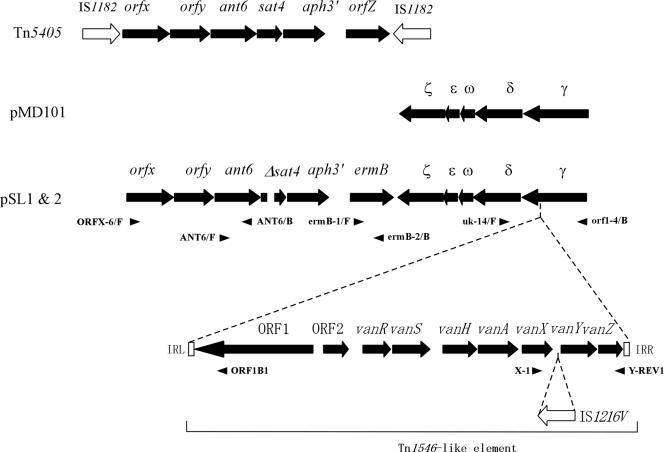

A region of approximately 22 kb containing the drug resistance determinants for streptomycin, kanamycin, erythromycin, and vancomycin and their flanking regions was amplified by long PCR using the primers specific for the drug resistance determinants and primers that were designed based on the sequences of homologous genes listed in the database (Fig. 5). The PCR products were sequenced. Computer analysis revealed the presence of several ORFs in this region (Fig. 5). Figure 5 shows the ORFs that had a good ribosome binding site in the 20-base region upstream of the predicted start codon. A homology search of ORFs carried on the 22-kb region of the pSL1 and pSL2 plasmids was performed by BLAST against the protein databases, and the results are shown in Table 6. The deduced amino acid sequences of the ORFs showed a high level of amino acid identity (100 to 98%) with ORFs carried on other plasmids or transposons (Table 6). Each of the ORFs that was designated an ORF or gene corresponded to a reported ORF or gene. Genes corresponding to ant6, aph(3′)-IIIa, and ermB, which encode streptomycin, kanamycin, and erythromycin resistance, were identified in the 22-kb region of the pSL plasmids. sat4 encodes streptothicin resistance (50). The Δsat4 carried on the pSL plasmids had a 62-bp deletion from nucleotides 230 to 291 within the 543-bp nucleotide sequence of the sat4 gene. The ant6, Δsat4, aph(3′)-IIIa, and ermB genes formed a cluster and were located in that order. orfx and orfy, which are carried on Tn5405 of Staphylococcus aureus, were upstream of ant(6). Tn5405 is flanked by IS1182, and it contains the genes orfx, orfy, ant(6), sat(4), aph(3′)-IIIa, and orfz in that order (Fig. 5) (14). The pSL plasmids carried all of the genes corresponding to the VanA-type vancomycin resistance genes carried on Tn1546 (Fig. 5). The Tn1546-like transposon carried on the pSL plasmids carried IS1216V (809 bp) in a noncoding region between vanX and vanY (Fig. 5). ORFγ, -δ, -ω, -ɛ, and -ζ, which corresponded to the reported ORFs on pMD101, were found within this region of the pSL plasmids (Fig. 5) (6). A Tn1546-like transposon was present as an insert in ORFγ (Fig. 5). The N-terminal position of ORFγ was located downstream of vanZ, which is contained within the Tn1546-like transposon (Fig. 5). The C-terminal portions of ORFγ, -δ, -ω, -ɛ, and -ζ were located between the 3′ end of ermB and the 3′ end of ORF1, which is contained within the Tn1546-like transposon (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Schematic representation of ORFs in the multidrug resistance region in the pSL plasmid. The filled arrows represent the ORFs and their directions of transcription. The open arrows represent the IS elements. The open boxes labeled IRL and IRR indicate the left and the right inverted repeats of the Tn1546-like element, respectively. The dotted lines above the Tn1546-like element indicate the insertion of the Tn1546-like element in the γ gene. The space in Δsat4 ORF indicates the deletion of 62 bp. The small arrowheads indicate the approximate locations and directions of the primers used for PCR to amplify the template DNAs to be sequenced.

TABLE 6.

ORFs and IS identified in multidrug resistance region

| ORF and IS | 5′/3′ ends of segment on map (bp)a | Size (no. of amino acids) | Identification | Amino acid identity (%) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| orfx | 1/870 | 289 | Tn5405 | 100 | 14 |

| orfy | 851/1585 | 244 | Tn5405 | 100 | |

| ant6 | 1618/2526 | 302 | Tn5405 | 100 | |

| Δsat4 | 2523/3003b | 84d | Tn5405 | 92e | |

| aph3 | 3096/3890 | 264 | Tn5405 | 100 | |

| ermB leader peptide | 4433/4516 | 27 | E. faecalis 373 | 100 | 37 |

| ermB | 4641/5378 | 245 | E. faecalis 373 | 100 | |

| ζ | 6504/5641 | 287 | pMD101 | 99 | 6 |

| ɛ | 6778/6506 | 90 | pMD101 | 99 | |

| ω | 7010/6795 | 71 | pMD101 | 99 | |

| δ | 7998/7102 | 298 | pMD101 | 98 | |

| γ | 8256/8101c | 51 | pMD101 | 99f | |

| ORF1 | 11297/8331 | 988 | Tn1546 | 100 | 2 |

| ORF2 | 11443/12018 | 191 | Tn1546 | 100 | |

| vanR | 12232/12927 | 231 | Tn1546 | 100 | |

| vanS | 12905/14059 | 389 | Tn1546 | 100 | |

| vanH | 14274/15242 | 322 | Tn1546 | 100 | |

| vanA | 15235/16266 | 343 | Tn1546 | 100 | |

| vanX | 16272/16880 | 202 | Tn1546 | 100 | |

| IS1216V | 17283/18091 | IS1216V | 100 | 2, 29 | |

| vanY | 18125/19036 | 303 | Tn1546 | 100 | 2 |

| vanZ | 19189/19674 | 161 | Tn1546 | 100 | |

| γ | 21918/19930c | 663 | pMD101 | 99f | 6 |

The positions given are from the first base of the sequence in the database (accession no. AB247327).

Δsat4 had a 62-bp deletion between 2751 and 2752 compared with wild-type sat4.

ORF was interrupted by the insertion of a Tn1546-like element between 8101 and 8102.

Δsat4 produces the protein prematurely terminated after amino acid 84, because of the 62-bp deletion. Wild-type sat4 produces a full-length protein of 180 amino acids.

The first 84 amino acids of Δsat4 and wild-type sat4 were compared. The DNA sequences of both genes were identical, except for the 62-bp deletion in Δsat4.

Amino acid sequence deduced from the DNA sequence without the insertion of the Tn1546-like element was compared with that of wild-type γ of pMD101.

DISCUSSION

E. faecium was the most prevalent of the vancomycin-resistant enterococci examined (i.e., 92% and 81% of isolates from chickens and patients, respectively), followed by E. faecalis (i.e., 4% and 19% of isolates from chickens and patients, respectively). The VRE isolates from both chickens and patients showed multiple drug resistance. However, the isolation frequencies of gentamicin and kanamycin resistances were significantly lower in E. faecium isolates obtained from chickens than in the isolates obtained from patients, suggesting that the use of different antimicrobial agents in the farming and hospital environments selected for E. faecium strains that differed in their drug resistance profiles.

Based on the physical map and sequence data of the regions of drug resistance determinants, the indistinguishable conjugative and pheromone-responsive plasmids pSL1 and pSL2 were identified from VanA-type E. faecalis strains KV1 and KV2, which were isolated from a human clinical sample and a chicken fecal sample, respectively. Plasmids pSL1 and pSL2 did not respond to any of the synthetic pheromones of cAD1, cPD1, cCF10, cOB1, and cAM373, which are pheromones for the previously characterized plasmids pAD1, pPD1, pCF10, pOB1, and pAM373, respectively (10). The pheromone specific to pSL plasmid has not been previously characterized and has been designated cSL1.

The two strains showed identical multiple drug resistance patterns, with the exception that KV2 was sensitive to tetracycline, but they showed different PFGE patterns with SmaI-digested chromosomal DNAs. The plasmids encoded multiple drug resistances to vancomycin, erythromycin, gentamicin, kanamycin, streptomycin, and teicoplanin. The linkage of the multiple drug resistance determinants on the plasmid may enable the multiple-drug-resistant E. faecalis strains to be selected in each of the two different environments.

The well-analyzed prototype pheromone-responsive plasmids pAD1 (8, 19), pCF10 (17, 18), and pPD1 (20, 43) have molecular sizes of around 60 kb and carry the genes for Hly/Bac and UV, Tc, and Bac21 resistances, respectively. The pheromone-responsive vancomycin resistance plasmid pHKK100 has a molecular size of 55 kb and encodes Hly/Bac and VanA resistance (22). The molecular size of the pSL1 and pSL2 plasmids was estimated to be 128.1 kb, which is relatively large in comparison with the prototype pheromone-responsive plasmids. Nucleotide sequence analysis revealed the orfx, orfy, ant6, Δsat4, aph3′, and ermB gene clusters, which, with the exception of ermB, correspond to the gene clusters found in Tn5405 of S. aureus. The ORFs corresponding to the γ, δ, ω, ɛ, and ζ ORFs that are carried on the Streptococcus pyogenes plasmid pMD101 were located at the 3′ end relative to ermB. The VanA resistance transposon, which is a Tn1546-like element, was inserted into ORFγ. These results implied that the relatively large pheromone-responsive pSL plasmids may be the result either of the transposition of different transposons or of recombination between a plasmid and an E. faecalis pheromone-responsive plasmid and that the resulting multiple drug resistance plasmid could be selected for in an environment where antibiotics are used.

In Europe, VanA-type VRE are widespread among food animals and foods of animal origin (4, 27, 49, 52). There are a number of routes by which these VREs of animal origin may be transmitted to humans. The food chain has been implicated as a possible route for the transmission of VanA-type VRE to humans. There has been one report that indistinguishable VRE and vanA-containing elements were found in a turkey sample and a turkey farmer, suggesting that the transmission of a VRE strain from a turkey to a human had occurred (49). The strains of VRE isolated from human and nonhuman sources show variations in pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of SmaI fragments of the chromosomal DNA (1, 38), suggesting that the transmission of the VanA resistance element has contributed significantly to the dissemination of VanA resistance (2). The heterogeneity of the VanA resistance determinant has been described as a result of structural changes. The structural changes of the VanA resistance determinant result from the insertion of IS1216V- (809 bp) or IS1216V- and IS3 (2,268 bp)-like elements into the noncoding region of the VanA determinant (51). In these studies, an identical Tn1546 type could be found in isolates obtained from both humans and farm animals (49, 51). We have shown identical substitutions of three amino acids in the vanS gene of the VanA-type determinant in isolates from humans and imported chickens (23, 38). These results suggest that the horizontal transmission of the vancomycin resistance transposon from farm animals to humans is possible (23, 38, 49, 51).

Our results provide evidence for genetic exchange between human and animal (chicken) VRE reservoirs and imply that humans would acquire VRE probably through the ingestion of food (chicken); the pheromone-responsive plasmid would then have transferred to the human-adapted E. faecalis strain from animal VRE temporarily colonizing the human intestine.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology [Tokuteiryoiki (C) and Kiban (B) and (C)] and the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (H15-Shinko-9).

We thank Yong Ho Park and Yeonhee Lee for providing VRE strains and helpful advice, Elizabeth Kamei for helpful advice, and Takahiro Nomura for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aarestrup, F. M., P. Butaye, and W. Witte. 2002. Nonhuman reservoirs of enterococci, p. 55-99. In M. S. Gilmore (ed.), The enterococci: pathogenesis, molecular biology, and antibiotic resistance. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 2.Arthur, M., C. Molinas, F. Depardieu, and P. Courvalin. 1993. Characterization of Tn1546, Tn3-related transposon conferring glycopeptide resistance by synthesis of depsipeptide peptidoglycan precursors in Enterococcus faecium BM4147. J. Bacteriol. 175:117-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. W. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1987. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 4.Bates, J., J. Z. Jordens, and D. T. Griffiths. 1994. Farm animals as a putative reservoir for vancomycin-resistant enterococcal infection in man. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 34:507-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlier, C., and P. Courvalin. 1990. Emergence of 4′,4"-aminoglycoside nucleotidyltransferase in Enterococcus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:1565-1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ceglowski, P., and J. C. Alonso. 1994. Gene organization of the Streptococcus pyogenes plasmid pDB101: sequence analysis of the orfη-copS region. Gene 145:33-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clewell, D. B. 1981. Plasmids, drug resistance, and gene transfer in the genus Streptococcus. Microbiol. Rev. 45:409-436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clewell, D. B. 1993. Sex pheromones and the plasmid-encoded mating response in Enterococcus faecalis, p. 349-367. In D. B. Clewell (ed.), Bacterial conjugation. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y.

- 9.Clewell, D. B., and B. L. Brown. 1980. Sex pheromone cAD1 in Streptococcus faecalis: induction of a function related to plasmid transfer. J. Bacteriol. 143:1063-1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clewell, D. B., and G. M. Dunny. 2002. Conjugation and genetic exchange in enterococci, p. 265-300. In M. S. Gilmore (ed.), The enterococci: pathogenesis, molecular biology, and antibiotic resistance. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 11.Clewell, D. B., P. K. Tomich, M. C. Gawron-Burke, A. E. Franke, Y. Yagi, and F. Y. An. 1982. Mapping of Streptococcus faecalis plasmids pAD1 and pAD2 and studies relating to transposition of Tn917. J. Bacteriol. 152:1220-1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coque, T. M., J. F. Tomayko, S. C. Ricke, P. C. Okhyusen, and B. E. Murray. 1996. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci from nosocomial, community, and animal sources in the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2605-2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeLisle, S., and T. M. Perl. 2003. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci: a road map on how to prevent the emergence and transmission of antimicrobial resistance. Chest 123:504S-518S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Derbise. A., K. G. Dyke, and N. el Solh. 1996. Characterization of a Staphylococcus aureus transposon, Tn5405, located within Tn5404 and carrying the aminoglycoside resistance genes, aphA-3 and aadE. Plasmid 35:174-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunny, G. M., B. L. Brown, and D. B. Clewell. 1978. Induced cell aggregation and mating in Streptococcus faecalis; evidence for a bacterial sex pheromone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 75:3479-3483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunny, G. M., R. A. Craig, R. L. Carron, and D. B. Clewell. 1979. Plasmid transfer in Streptococcus faecalis: production of multiple sex pheromones by recipients. Plasmid 2:454-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunny, G. M., and B. A. Leonard. 1997. Cell-cell communication in gram-positive bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 51:527-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunny, G. M., B. A. Leonard, and P. J. Hedberg. 1995. Pheromone-inducible conjugation in Enterococcus faecalis: interbacterial and host-parasite chemical communication. J. Bacteriol. 177:871-876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Francia, M. V., W. Haas, R. Wirth, E. Samberger, A. Muscholl-Silberhorn, M. S. Gilmore, Y. Ike, K. E. Weaver, F. Y. An, and D. B. Clewell. 2001. Completion of the nucleotide sequence of the Enterococcus faecalis conjugative virulence plasmid pAD1 and identification of a second transfer origin. Plasmid 46:117-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujimoto, S., H. Tomita, E. Wakamatsu, K. Tanimoto, and Y. Ike. 1995. Physical mapping of the conjugative bacteriocin plasmid pPD1 of Enterococcus faecalis and identification of the determinant related to the pheromone response. J. Bacteriol. 177:5574-5581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galli, D., A. Friesenegger, and R. Wirth. 1992. Transcriptional control of sex-pheromone-inducible genes on plasmid pAD1 of Enterococcus faecalis and sequence analysis of a third structural gene for (pPD1-encoded) aggregation substance. Mol. Microbiol. 6:1297-1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Handwerger, S., M. J. Pucci, and A. Kolokathis. 1990. Vancomycin resistance is encoded on a pheromone response plasmid in Enterococcus faecium 228. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:358-360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hashimoto, Y., K. Tanimoto, Y. Ozawa, T. Murata, and Y. Ike. 2000. Amino acid substitutions in the VanS sensor of the VanA-type vancomycin-resistant enterococcus strains result in high-level vancomycin resistance and low-level teicoplanin resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 185:247-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirt, H., R. Wirth, and A. Muscholl. 1996. Comparative analysis of 18 sex pheromone plasmids from Enterococcus faecalis: detection of a new insertion element on pPD1 and implications for the evolution of this plasmid family. Mol. Gen. Genet. 252:640-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huycke, M. M., D. F. Sahm, and M. S. Gilmore. 1998. Multiple-drug resistant enterococci: the nature of the problem and an agenda for the future. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 4:239-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ike, Y., and D. B. Clewell. 1984. Genetic analysis of the pAD1 pheromone response in Streptococcus faecalis, using transposon Tn917 as an insertional mutagen. J. Bacteriol. 158:777-783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ike, Y., K. Tanimoto, Y. Ozawa, T. Nomura, S. Fujimoto, and H. Tomita. 1999. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci in imported chickens in Japan. Lancet 353:1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ike, Y., K. Tanimoto, H. Tomita, K. Takeuchi, and S. Fujimoto. 1998. Efficient transfer of the pheromone-independent Enterococcus faecium plasmid pMG1 (Gmr) (65.1 kb) to Enterococcus strains during broth mating. J. Bacteriol. 180:4886-4892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen, L. B. 1998. Internal size variations in Tn1546-like elements due to the presence of IS1216V. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 169:349-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kak, V., and J. W. Chow. 2002. Acquired antibiotic resistances in enterococci, p. 355-383. In M. S. Gilmore (ed.), The enterococci: pathogenesis, molecular biology, and antibiotic resistance. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 31.Kao, S. M., S. B. Olmsted, A. S. Viksnins, J. C. Gallo, and G. M. Dunny. 1991. Molecular and genetic analysis of a region of plasmid pCF10 containing positive control genes and structural genes encoding surface proteins involved in pheromone-inducible conjugation in Enterococcus faecalis. J. Bacteriol. 173:7650-7664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kobayashi, N., M. Alam, Y. Nishimoto, S. Urasawa, N. Uehara, and N. Watanabe. 2001. Distribution of aminoglycoside resistance genes in recent clinical isolates of Enterococcus faecalis, Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus avium. Epidemiol. Infect. 126:197-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Machida, R. J., M. U. Miya, M. Nishida, and S. Nishida. 2002. Complete mitochondrial DNA sequence of Tigriopus japonicus (Crustacea:Copepoda). Mar. Biotechnol. 4:406-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martone, W. J. 1998. Spread of vancomycin-resistant enterococci: why did it happen in the United States? Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiol. 19:539-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McDonald, L. C., M. J. Kuehnert, F. C. Tenover, and W. R. Jarvis. 1997. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci outside the health-care setting: prevalence, sources, and public health implications. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 3:311-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2000. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 5th ed. Approved standard M7-A4. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 37.Oh, T. G., A. R. Kwon, and E. C. Choi. 1998. Induction of ermAMR from a clinical strain of Enterococcus faecalis by 16-membered-ring macrolide antibiotics. J. Bacteriol. 180:5788-5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ozawa, Y., K. Tanimoto, T. Nomura, M. Yoshinaga, Y. Arakawa, and Y. Ike. 2002. Vancomycin resistant enterococci (VRE) in humans and imported chickens in Japan. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:6457-6461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 40.Schmitz, F. J., R. Sadurski, A. Kray, M. Boos, R. Geisel, K. Kohrer, J. Verhoef, and A. C. Fluit. 2000. Prevalence of macrolide-resistance genes in Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecium isolates from 24 European university hospitals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 45:891-894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seo, K. S., J. Y. Lim, H. S. Yoo, W. K. Bae, and Y. H. Park. 2005. Comparison of vancomycin-resistant enterococci isolates from human, poultry and pigs in Korea. Vet. Microbiol. 106:225-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shin, J. W., D. Yong, M. S. Kim, K. H. Chang, K. Lee, J. M. Kim, and Y. Chong. 2003. Sudden increase of vancomycin-resistant enterococcal infections in a Korean tertiary care hospital: possible consequences of increased use of oral vancomycin. J. Infect. Chemother. 9:62-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanimoto, K., H. Tomita, and Y. Ike. 1996. The traA gene of the Enterococcus faecalis conjugative plasmid pPD1 encodes a negative regulator for the pheromone response. Plasmid 36:55-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tomich, P. K., F. Y. An, and D. B. Clewell. 1980. Properties of erythromycin-inducible transposon Tn917 in Streptococcus faecalis. J. Bacteriol. 141:1366-1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tomita, H., and Y. Ike. 2005. Genetic analysis of transfer-related regions of the vancomycin resistance Enterococcus conjugative plasmid pHTβ: identification of oriT and a putative relaxase gene. J. Bacteriol. 187:7727-7737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tomita, H., C. Pierson, S. K. Lim, D. B. Clewell, and Y. Ike. 2002. Possible connection between a widely disseminated conjugative gentamicin resistance (pMG1-like) plasmid and the emergence of vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecium. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3326-3333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tomita, H., K. Tanimoto, S. Hayakawa, K. Morinaga, K. Ezaki, H. Oshima, and Y. Ike. 2003. Highly conjugative pMG1-like plasmids carrying Tn1546-like transposons that encode vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecium. J. Bacteriol. 185:7024-7028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Udo, E. E., N. Al-Sweih, P. John, and T. D. Chugh. 2002. Antibiotic resistance of enterococci isolated at a teaching hospital in Kuwait. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 43:233-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van den Bogaard, A. E., L. B. Jensen, and E. E. Stobberingh. 1997. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci in turkeys and farmers. N. Engl. J. Med. 337:1558-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Werner, G., B. Hildebrandt, and W. Witte. 2001. Aminoglycoside-streptothricin resistance gene cluster aadE-sat4-aphA-3 disseminated among multiresistant isolates of Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3267-3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Willems, R. J., J. Top, N. van den Braak, A. van Belkum, D. J. Mevius, G. Hendriks, M. van Santen-Verheuvel, and J. D. van Embden. 1999. Molecular diversity and evolutionary relationships of Tn1546-like elements in enterococci from humans and animals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:483-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Witte, W. 1998. Medical consequences of antibiotic use in agriculture. Science 279:996-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]