Abstract

To explore early intermediates in membrane fusion mediated by influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) and their dependence on the composition of the target membrane, we studied lipid mixing between HA-expressing cells and liposomes containing phosphatidylcholine (PC) with different hydrocarbon chains. For all tested compositions, our results indicate the existence of at least two types of intermediates, which differ in their lifetimes. The composition of the target membrane affects the stability of fusion intermediates at a stage before lipid mixing. For less fusogenic distearoyl PC-containing liposomes at 4°C, some of the intermediates inactivate, and no intermediates advance to lipid mixing. Fusion intermediates that formed for the more fusogenic dioleoyl PC-containing liposomes did not inactivate and even yielded partial lipid mixing at 4°C. Thus, a more fusogenic target membrane effectively blocks nonproductive release of the conformational energy of HA. Even for the same liposome composition, HA forms two types of fusion intermediates, dissimilar in their stability and propensity to fuse. This diversity of fusion intermediates emphasizes the importance of local membrane composition and local protein concentration in fusion of heterogeneous biological membranes.

INTRODUCTION

Fusion of two membranes into one is a ubiquitous process in living cells. Fusion mediated by hemagglutinin (HA), the envelope glycoprotein of influenza virus, is one of the best-characterized fusion reactions. To invade the cell, influenza virus binds to sialic acid receptors at the cell surface, enters the cell by endocytosis, and, finally, delivers viral RNA into the cytosol by fusing the viral envelope and the endosome membrane (1,2). This fusion reaction is triggered by acidification of the endosome content and mediated by HA. The surface of the virus is covered by HA trimers; each HA monomer consists of two subunits, larger HA1 and smaller HA2, connected by a single disulfide bond. The structure of the initial neutral-pH conformation of HA and the restructuring of HA at acidic pH have been characterized in detail through different experimental approaches (1–5). The pathway of HA-mediated fusion has been studied in different experimental systems, including virus fusion to red blood cells (RBC) and liposomes (6,7) as well as fusion of HA-expressing cells (HA-cells) with RBC (8–10) and liposomes (11–14). However, the mechanisms that couple low-pH-dependent restructuring of HA and membrane rearrangement remain elusive.

Conformational changes in acidified HA in the absence of a target membrane result in HA inactivation, detected as a decrease in the fusion rate after application of an additional low-pH pulse in the presence of the target membrane (4,15). Under fusion-inhibiting conditions (for instance, at low temperature or in the presence of lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC)), low-pH application to contacting HA-expressing and target membranes yields interesting fusion intermediates (6,10,16,17). Although these early fusion intermediates allow neither lipid nor content mixing, the system is already committed to fusion and will complete it at neutral pH, when the inhibition is lifted. Low-pH-activated HAs do not maintain their fusogenic activity for an indefinitely long time. Fusogenicity of activated HAs decreases with time, as evidenced by the gradual loss of fusion potential at the LPC-arrested stage (17,18) and by the limited lifetime of early fusion intermediates (19,20).

The contact area between the HA-cell and the RBC is large enough to allow formation of multiple fusion sites (19,21,22), complicating the detection of early fusion intermediates. A fusion phenotype that is less advanced in the hierarchy of fusion phenotypes, from restricted hemifusion (neither lipid nor content mixing) to unrestricted hemifusion (lipid mixing without content mixing) to complete fusion (lipid and content mixing), is undetectable in the presence of a more advanced phenotype. For instance, the formation of a single expanding fusion pore in the contact zone would not allow the detection of hundreds of hemifusion sites present in the same contact zone. Under optimal fusion conditions, the large contact zone between two fusing cells contains multiple, diverse, and rapidly evolving fusion intermediates.

We are interested in the HA- and membrane-involving intermediates, which precede lipid mixing and precede even the irreversible commitment to eventual lipid mixing. Characterization of the early intermediates might be facilitated by decreasing the area of contact and slowing down the fusion reaction. In this work, therefore, we replaced RBC, as target membranes (8,10,23), with liposomes, and we inhibited the fusion of HA-cells to liposomes by lowering the temperature (10,16,24,25). Some stages of the conformational change in HA are also slowed down or blocked under these conditions (26,27).

To study the effects of the composition of the target membrane on the evolution of the intermediates, for liposomes containing the invariable molar percentages of phosphatidylcholine (PC), cholesterol, HA-receptor ganglioside, and fluorescent lipid probe, we varied the hydrocarbon chains of the PC used (e.g., distearoyl PC, DSPC versus dioleoyl PC, DOPC versus stearoyl-oleoyl PC, SOPC). For all tested compositions, our results indicate the existence of at least two types of intermediates, which differ in their lifetimes. The rate and direction of the progression from early intermediates toward either lipid mixing or fusion inactivation differ significantly for different PCs, with the more “fusogenic” DOPC effectively blocking nonproductive release of the conformational energy of HA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

1,2-Distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine (DSPC), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine (DOPC), 1-stearoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine (SOPC), cardiolipin (CL; heart disodium salt), cholesterol, 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylethanolamine-N-(lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl) (RhDPPE), and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylethanolamine-N-(lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl) (RhDOPE) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Disialoganglioside (GD1a) from bovine brain, citric acid, neuraminidase (EC 3.2.1.18, type V, from Clostridium perfringens), and trypsin (EC 3.4.21.4, type IX, from porcine pancreas) were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). Methanol and sodium hydroxide were purchased from Mallinckrodt (Paris, KY). Sodium chloride and benzene were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ). Purified polyethylene glycol (PEG) 8000 (mol wt 7000–9000) purchased from Fisher Scientific and purified as in Lentz et al. (28) was a generous gift of Drs. Barry R. Lentz and Md. Emdadul Haque, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

HEPES was purchased from ICN Biomedicals (Aurora, OH). Triton X-100 was purchased from Research Products International (Mount Prospect, IL). Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (D-PBS) with Ca and Mg and D-PBS without Ca or Mg were purchased from Biofluids (Rockville, MD). EGTA was purchased from Fluka (Buchs, Switzerland). EDTA was purchased from Quality Biological (Gaithersburg, MD). Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), and penicillin–streptomycin–glutamine were purchased from Gibco BRL (Gaithersburg, MD).

Liposomes

Liposomes were prepared as described in Bailey and Cullis (29). In brief, solutions of lipids (total amount 1 μmol) in benzene/methanol (95:5, vol:vol) were dried and then hydrated to generate a 1 mM multilamellar liposome suspension. After five freeze-thaw cycles, the vesicles were extruded at 60°C 10 times through two polycarbonate Nucleopore filters (100-nm pore size) and one mesh spacer (Osmonics, Minnetonka, MN) in a pressure extruder (Lipex Biomembranes, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) to produce large unilamellar vesicles. After extrusion, liposomes were diluted in a 1:4 ratio either with D-PBS (with Ca and Mg or without Ca or Mg) buffer or with HEPES buffer (140 mM sodium chloride, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4). The size of extruded liposomes (i.e., ∼100 nm in diameter) was verified by means of quasielastic light scattering on a Coulter N4 Plus particle sizer (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA).

Liposome compositions are stated as molar ratios between component lipids. All compositions included 5% fluorescent lipid probe and, if not stated otherwise, 5% disialoganglioside, which serves as a receptor for HA binding (30). DSPC/cholesterol liposomes (DSPC-LS) had the following composition: 49.5% DSPC, 40.5% cholesterol, 5% RhDPPE, and 5% disialoganglioside. DSPC-LS without disialoganglioside had the following composition: 52.25% DSPC, 42.75% cholesterol, and 5% RhDPPE. SOPC/cholesterol liposomes (SOPC-LS) were formed from a mixture of 49.5% SOPC, 40.5% cholesterol, 5% RhDOPE, and 5% disialoganglioside. DOPC/cholesterol liposomes (DOPC-LS) had the following composition: 49.5% DOPC, 40.5% cholesterol, 5% RhDOPE, and 5% disialoganglioside. CL-containing DSPC/cholesterol liposomes (DSPC/CL-LS) were formed from a mixture of 46.75% DSPC, 38.25% cholesterol, 2.5% CL, 5% RhDPPE, and 5% disialoganglioside. (One CL molecule, with two polar heads and four acid tails, was counted as the equivalent of two PC molecules.) Liposomes were always used on the day of extrusion.

DSPC-LS and DOPC-LS without dye, used only in experiments studying virus-liposome fusion and PEG-induced liposome-liposome fusion, had the following composition: 52.25% PC (DSPC or DOPC), 42.75% cholesterol, and 5% disialoganglioside.

Cells

CV-1 green monkey kidney cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. CV-1 cells were infected 48 h before the experiment with SV40 recombinant viral vector containing Udorn HA-gene (influenza A/Udorn/72; H3 subtype) (31,32), a generous gift of Dr. Robert A. Lamb, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL. (Udorn strain has a very high degree of similarity, ∼96%, to extensively studied X-31 strain.) Slightly subconfluent monolayers of cells were incubated with SV40-HA stock at 37°C, as described in Melikyan et al. (23). After a 1-h incubation, the viral suspension was diluted in a 1:6 ratio with DMEM complete medium. On the day of the experiment, cells were treated for 15 min at 37°C with trypsin (5 μg/ml) and neuraminidase (1 unit/ml) in D-PBS with Ca and Mg and washed twice with this buffer. Then, cells were incubated with liposomes for 1 h at 4°C and washed five times, still at 4°C, to remove unbound liposomes. After that, cells were removed from the flasks with Ca- and Mg-free D-PBS containing both EDTA and EGTA at 0.5 mg/ml. EDTA- and EGTA-containing buffer was removed, and cells were washed with cold (4°C) buffer and then harvested with ∼3 ml of the same buffer.

Fusion of HA-cells with RBC

In some experiments, we studied HA-mediated fusion in a well-characterized experimental system of HA-cells fusing with labeled human red blood cells (RBC). RBC were labeled with membrane dye PKH26 (Sigma Chemical), and fusion experiments were performed as described earlier (10).

Fusion of HA-cells with liposomes

In most experiments, 600 μl of the suspension of cells with bound liposomes (∼105 cells and ∼5 × 109 liposomes) were incubated at pH 4.9, 4°C, for different durations, and then 500 μl of this suspension was mixed in a four-clear-sided methacrylate cuvette (Fisher Scientific) with 1.5 ml of aqueous buffer, pH 7.4. As a result, our measurements were carried out at neutral pH. Fluorescence was monitored for at least 4.5 min at the required temperature with an Aminco Bowman Series 2 luminescence spectrometer (Rochester, NY) with excitation at 530 nm and emission at 590 nm. The medium in the cuvettes was continuously stirred with a magnetic stirring device and thermostatted with a circulating water bath (Hoefer Scientific Instruments, San Francisco, CA).

Because our liposomes contained fluorescent lipid probe in a self-quenched concentration, lipid mixing on fusion between liposomes and cells diluted the probe and increased the observed fluorescence. To quantify the rates and extents of lipid mixing for different conditions, we measured the fluorescence of the samples (F) as a function of time and normalized it to the fluorescence (Fmax) measured on maximum dequenching by solubilizing membranes with 1 mM Triton X-100 at the end of each experiment. The percentage of lipid mixing was calculated as

|

where F0 is the fluorescence of the suspension of cells with liposomes not exposed to low pH at the onset of the measurements.

Each experiment presented here was repeated at least two times, and all functional dependencies reported were observed in each experiment.

In some experiments, we evaluated liposome binding to the cells by comparing the fluorescence of cell-associated liposomes with the fluorescence of a known amount of liposomes as described in Bailey et al. (14).

Liposome-liposome fusion mediated by PEG

A 500-μl sample of the 1:10 mixture of labeled and unlabeled liposomes containing DOPC (or DSPC) and cholesterol was incubated at 4°C at pH 7.4 and then mixed in a cuvette with 1.5 ml of the solution of PEG in aqueous buffer. Fluorescence measurements were carried out at pH 7.4.

Virus-liposome fusion

In virus-liposome fusion experiments, we used DSPC-LS and DOPC-LS formed from 52.25% PC (DSPC or DOPC), 42.75% cholesterol, and 5% disialoganglioside. Liposomes were incubated in D-PBS with the viral particles labeled with a self-quenching concentration of a membrane dye, octadecyl rhodamine B (R18; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) (33). The liposomes and viruses were incubated for 5 min at neutral pH to establish virus-liposome binding and then placed into a pH-4.9 medium to trigger fusion.

RESULTS

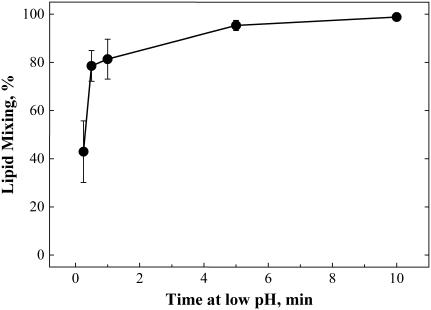

Inactivation and lipid mixing at 4°C

Although lowering the temperature to 4°C inhibits HA-mediated fusion (10,16,25), it does not prevent the low-pH-induced transition from the initial conformation to an acidic form of HA. To study the functional inactivation of low-pH-activated HAs in the presence of the target membrane, we followed the changes in HA fusogenicity under fusion-inhibiting conditions. We first triggered HA-mediated fusion in the presence of liposomes at 4°C (low-pH pretreatment) and then evaluated the fusogenic potential by measuring lipid mixing after raising the temperature to 37°C and simultaneously returning the pH to neutral. For DSPC-LS, there was almost no lipid mixing at 4°C (Fig. 1) and significant lipid mixing on a rise in the temperature (Fig. 2 A). For both DSPC-LS and SOPC-LS, after low-pH application, a longer incubation at 4°C lowered the extent of lipid mixing at 37°C down to the level reached after a 15-min incubation at 4°C at pH 4.9. As shown in Fig. 2 C for DSPC-LS, the time traces corresponding to different durations of incubation of HA-cells with liposomes at pH 4.9 had similar shapes.

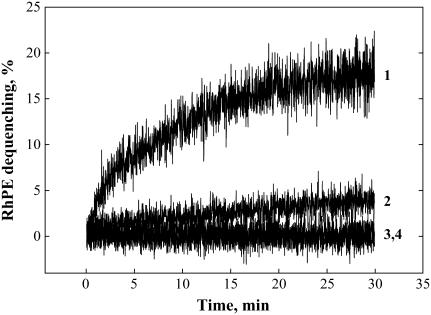

FIGURE 1.

Lipid mixing at 4°C between HA-cells and DOPC-LS (curves 1 and 3), HA-cells and DSPC-LS (curves 2 and 4), recorded at pH 4.9 (curves 1 and 2; pH was lowered to 4.9 at the onset of measurements) and pH 7.4 (curves 3 and 4).

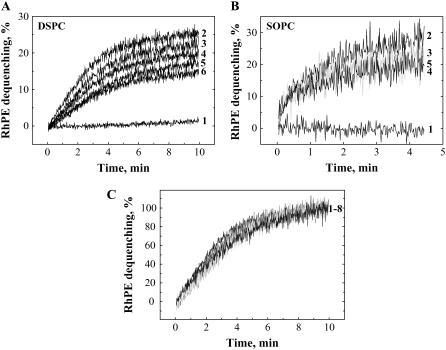

FIGURE 2.

(A) Lipid mixing at 37°C at neutral pH between HA-cells and DSPC-LS recorded without low-pH application (curve 1) and after the following durations of incubation at 4°C at pH 4.9: 1 min (curve 2), 3 min (curve 3), 5 min (curve 4), 10 min (curve 5), 60 min (curve 6). (B) Lipid mixing at 37°C at neutral pH between HA-cells and SOPC-LS recorded without low-pH application (curve 1) and after the following durations of incubation at 4°C at pH 4.9: 1 min (curve 2), 5 min (curve 3), 10 min (curve 4), 20 min (curve 5). (C) Lipid mixing at 37°C at neutral pH between HA-cells and DSPC-LS, normalized to the level of fluorescence observed 10 min after raising the temperature and recorded after the following durations of incubation at 4°C at pH 4.9: 1 min, 2 min, 3 min, 5 min, 10 min, 30 min, 60 min, 90 min (curves 1–8).

For DOPC-LS, significant lipid mixing was observed at 4°C (Fig. 1). Raising the temperature to 37°C at neutral pH yielded significant additional lipid mixing (Fig. 3 A). In contrast to DSPC-LS and SOPC-LS, DOPC-LS demonstrated the same final extent of lipid mixing at 37°C regardless of the time of exposure to acidic pH at 4°C (Fig. 3 A). Although the extent of the lipid mixing at 37°C for DSPC-LS containing small amount of cardiolipin (2.5 mol %) decreased with an increase in the duration of the low-pH incubation at 4°C, this decrease was less profound than for cardiolipin-free DSPC-LS (Fig. 3 B versus Fig. 2 A).

FIGURE 3.

(A) Lipid mixing at 37°C at neutral pH between HA-cells and DOPC-LS recorded without low-pH application (curve 1) and after the following durations of incubation at 4°C at pH 4.9: 1 min (curve 2), 15 min (curve 3), 30 min (curve 4), and 60 min (curve 5). (B) Lipid mixing at 37°C at neutral pH between HA-cells and DSPC/CL-LS recorded without low-pH application (curve 1) and after the following durations of incubation at 4°C at pH 4.9: 2 min (curve 2), 5 min (curve 3), 15 min (curve 4), 60 min (curve 5).

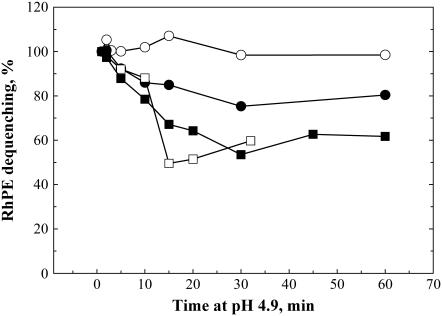

To emphasize the different patterns of functional inactivation of low-pH-activated HAs (Fig. 2, A and B, and Fig. 3, A and B), we plotted the dependences of the lipid-mixing extents observed in representative experiments 4.5 min after reneutralization and raising the temperature to 37°C on the duration of low-pH application (Fig. 4). Fusion rates varied from day to day, with the highest variability observed for SOPC-LS. However, the characteristic differences between the patterns of fusion inactivation and the levels at which lipid-mixing extent reached plateau for different liposome compositions were observed in all experiments. At plateau, the mean levels of fluorescence (with standard deviations) were 103.7 ± 3.8% in the four experiments with DOPC-LS, 79.6 ± 5.8% in the three experiments with DSPC/CL-LS, 67.9 ± 15.1% in the three experiments with SOPC-LS, and 51.1 ± 11.1% in the five experiments with DSPC-LS. Statistical analysis (Student's t-test) confirms that the differences between the extents of dequenching at plateau for liposomes that demonstrate the lack of inactivation (DOPC-LS) and partial inactivation (DSPC-LS and SOPC-LS) are statistically significant. The extents of dequenching at plateau for DSPC-LS and SOPC-LS were statistically different from DOPC-LS (p = 0.00004 and p = 0.005, respectively), and DSPC-LS significantly differed from DSPC/CL-LS (p = 0.007). In contrast, the extents of dequenching at plateau were statistically indistinguishable for DSPC-LS and SOPC-LS (p = 0.12) and for DSPC/CL-LS and SOPC-LS (p = 0.28).

FIGURE 4.

Lipid mixing at 37°C at neutral pH between HA-cells and liposomes is dependent on the duration of incubation at 4°C at pH 4.9. The percentage of fluorescence dequenching of the lipid probe observed 4.5 min after raising the temperature is plotted as function of the duration of incubation at 4°C at pH 4.9, normalized to the level of fluorescence after incubation at pH 4.9 for 1 min. Liposomes are DOPC-LS (○), DSPC/CL-LS (•), SOPC-LS (□), and DSPC-LS (▪).

One may hypothesize that, after pH-4.9 application, fusion of DOPC-LS is too robust to allow detection of subtle changes in the conditions (4), thus hindering the detection of fusion inactivation with time at low pH. This possibility was excluded by the experiment in which we lowered the number of activated HAs by using less-acidic pH. Even at pH 5.7, DOPC-LS still did not demonstrate any inactivation at 4°C (data not shown). Longer incubation at 4°C did not decrease lipid mixing measured at 37°C and actually promoted lipid mixing, perhaps by allowing more time for the formation of a multi-protein fusion machine or fusion-committed intermediates (10).

In the experiments described above, after the onset of low-pH application, the HA-cells with bound liposomes were kept at low pH until the temperature was raised. The rate and extent of lipid mixing observed at 37°C after treatment of cells with DSPC-LS at 4°C with a 1-min pH-4.9 pulse followed by 9 min at pH 7 were identical to those observed after a 10-min pH-4.9 pulse applied at 4°C rather than to those observed after a 1-min pH-4.9 pulse immediately followed by raising the temperature to 37°C (data not shown). One can hypothesize that fusion extent in the case of a 1-min pH-4.9 pulse followed by 9 min at pH 7 is lowered by a decrease in the number of low-pH-activated HA molecules on return of some of them at neutral pH to the initial conformation. This, however, is not the case because the second 1-min low-pH pulse (immediately before the raising of the temperature) did not change the fusion extent (data not shown). This finding indicates that, once triggered by low pH, fusion inactivation proceeds at neutral pH.

In general, the relative fusogenicity of different liposome compositions (DOPC-LS ≫ SOPC-LS > DSPC-LS) was conserved among three different experimental protocols: 1), fusion triggered and observed at 4°C, 2), fusion triggered and observed at 37°C (data not shown), and 3), fusion triggered at 4°C and observed at 37°C. We also found DOPC-LS to be more fusogenic than DSPC-LS both at 4°C and at 37°C for PEG-induced liposome-liposome fusion (data not shown).

Thus, the greater extents of inactivation during low-pH application at 4°C for DSPC-LS versus DOPC-LS correlate with lower fusogenicity of these liposomes.

Interestingly, neither of the liposome compositions studied matched the fusogenic properties of the RBC membrane, the membrane most frequently used as a target for HA-mediated fusion. Udorn HA-expressing cells with bound RBC were treated at 4°C with pH-5.2 pulses of different durations. As in the case of the fusion of HA-cells with DSPC-LS, no lipid mixing was observed at 4°C (similar results have been reported for X-31 HA-expressing cells (10)). Warming low-pH-treated RBC/HA-cell complexes to 37°C at neutral pH resulted in lipid mixing. The fusion extent detected increased with an increase in the duration of the pH-5.2 pulse applied at 4°C (Fig. 5). Thus, as in the case of the fusion of HA-cells with DOPC-LS, there was no functional inactivation of HA at 4°C.

FIGURE 5.

Lipid mixing between HA-cells and bound RBCs is dependent on the duration of incubation of the cell pairs at pH 5.2 at 4°C. After this incubation, pH of the medium was returned to neutral, and simultaneously the temperature was raised to 37°C. The extent of fusion was measured 10 min after the low-pH application. Bars are mean ± SE, n ≥ 3.

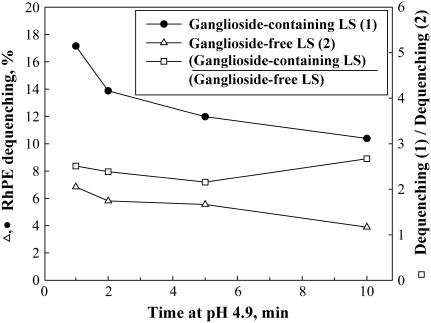

Despite the profound difference among the fusion patterns for different liposome compositions, our results suggested an important common trend. Partial dequenching of DOPC-LS at 4°C and partial inactivation of DSPC-LS at the same temperature indicated that both DOPC-LS and DSPC-LS can form fusion sites with radically different properties. One might hypothesize that the different patterns of HA restructuring, such as partial inactivation, observed for the same liposome composition reflect different modes of liposome binding: specific binding via the HA1-sialic acid connection versus nonspecific binding. However, our finding that an extension of the incubation time at pH 4.9, 4°C, from 1 to 10 min for ganglioside-containing versus ganglioside-free DSPC-LS resulted in a similar 1.6-fold inhibition of lipid mixing at 37°C (Fig. 6) argues against this possibility.

FIGURE 6.

Lipid mixing at 37°C at neutral pH between HA-cells and liposomes is dependent on the duration of incubation at 4°C at pH 4.9. The percentage of fluorescence dequenching of the lipid probe observed 10 min after raising the temperature is plotted as a function of the duration of incubation at 4°C at pH 4.9. Dequenching for ganglioside-containing DSPC-LS (•), dequenching for ganglioside-free DSPC-LS (▵), ratio of dequenching extents for ganglioside-containing and ganglioside-free DSPC-LS (□).

HA inactivation and interaction with the target membrane

It has been hypothesized that insertion of the fusion peptides of low-pH-restructured HA into the target membrane rather than into HA-expressing membrane determines whether this HA will fuse or undergo unproductive inactivation (34). Along these lines, the effects of the lipid composition of the target membranes on the inactivation or the lack of the inactivation of HA at 4°C might reflect the difference between the modes of interaction of the fusion peptide with DOPC-LS versus DSPC-LS and SOPC-LS. Binding of the fusion peptide to the target membrane can be detected as a low-pH-induced increase in the binding of receptor-free liposomes to HA-expressing membrane (6,35). We found that low-pH-treated HA-cells bound similar numbers of ganglioside-free DOPC-LS and DSPC-LS. For 100-nm DOPC-LS and DSPC-LS, the estimate gave ∼69,000 and ∼67,000 bound liposomes per cell, respectively (average of four experiments for each composition). Thus, fusion peptides (and any other regions of low-pH HA conformation that might reach the target membrane and bind to it) bind similarly to liposomes of either composition.

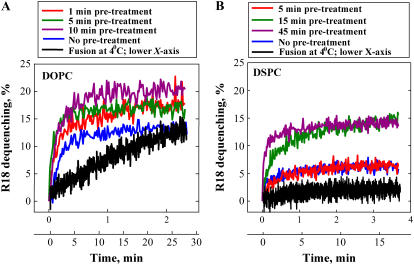

Fusion of viral particles with liposomes

Liposomes of the same composition present different patterns of fusion with HA-cells, as evidenced by partial fusion for DOPC-LS and partial inactivation for DSPC-LS at 4°C. We hypothesized that the two distinct patterns of cell-liposome fusion reflect an inhomogeneity of lateral distribution of HA at the surface of the HA-cell. Fusion patterns for individual liposomes associated with raft-like membrane domains enriched in HA (36) are likely to differ from those for liposomes associated with membrane carrying HA at a lower density.

To test this hypothesis, we studied liposome fusion to influenza viral particles, which, in contrast to HA-cells, always have HA at a density close to the highest surface density of HA allowed by the protein sizes (37).

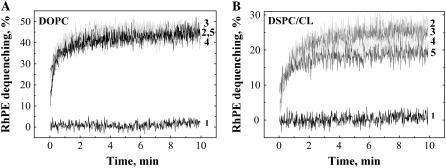

Prebound R18-labeled viral particles and liposomes were treated with acidic pH at 4°C for different durations. Then, at the onset of measurements, the temperature was raised to 37°C, and measurements were carried out still at pH 4.9. However, some experiments were carried out at 4°C; in these experiments, pH was lowered to 4.9 at the onset of measurements. Lipid mixing both at 4°C and at 37°C was detected as R18 dequenching. Like liposome/HA-cell fusion, liposome-virus fusion was dependent on liposome composition, with liposomes from DOPC/cholesterol being more fusogenic than those from DSPC/cholesterol (Fig. 7). For DOPC-LS, lipid mixing proceeded at 4°C and reached an extent even higher than that observed for virus/liposome fusion at 37°C (data not shown). Similar results have been reported for virus fusion with liposomes and RBC (6,16,38). For DSPC-LS, a low-pH application at 4°C produced neither lipid mixing nor fusion inactivation, detected as a decrease in the final lipid mixing observed after raising the temperature to 37°C. After a 45-min incubation at pH 4.9, raising the temperature to 37°C (still at pH 4.9) resulted in fusion extents that were the same as or even higher than those found when viruses-liposomes were pretreated with low pH for a shorter time or were not low-pH-pretreated at all (Fig. 7 B). Thus, in virus-liposome fusion for each of the two studied liposome compositions, we found no indications of the existence of two distinct fusion patterns such as partial inactivation and partial fusion for DSPC-LS and DOPC-LS, respectively, in liposome/HA-cell fusion.

FIGURE 7.

Lipid mixing between virus and DOPC-LS (A) or DSPC-LS (B) was recorded at pH 4.9 at 37°C after R18-labeled viral particles with bound liposomes were preincubated at pH 4.9 at 4°C for 1 min, 5 min, and 10 min (A) and 5 min, 15 min, and 45 min (B). Recordings shown in blue and black represent experiments without pretreatment (blue) and the experiments where lipid mixing was detected at 4°C (black). Note that lipid mixing in the later experiments proceeded much more slowly and thus is presented with a different time scale.

DISCUSSION

At some stage of the fusion reaction, the properties of fusion intermediates become sensitive to the properties of the target membrane. In the absence of a target membrane, a low-pH application rapidly inactivates HA (4,15,39), but in the presence of the target membrane, when fusion is blocked by LPC (17) or by low (4°C) temperature (10), this low-pH-dependent inactivation is strongly inhibited. How does the presence of the target membrane inhibit HA inactivation? In this work, we accumulated intermediates of cell-liposome fusion at 4°C and found that their evolution toward either fusion or inactivation depends drastically on liposome composition.

The time course of fusion inactivation observed for ganglioside-containing liposomes was found to be identical to that for ganglioside-free liposomes. Thus, HA1-receptor interactions are not critical for the inhibition of inactivation in the presence of the target membrane. With low-pH-dependent receptor-independent binding of HA to the target membrane taken as a measure of their interaction (6,35), the similarity in binding of DOPC-LS and DSPC-LS to HA-cells suggests that the difference between the patterns of fusion and inactivation for these lipid compositions does not reflect the difference between the ways in which the low-pH form of HA binds to these liposomes. It still remains possible that the angle of the fusion peptide insertion (40) and its functional consequences vary with liposome composition. Fusion and inactivation might also depend on the properties of the target membrane downstream of its interaction with HA. The composition of the target membrane can be crucial for bringing this membrane into tight contact and then fusing it with the HA-expressing membrane.

Fusion at 4°C

Although early stages of low-pH-triggered conformational change in HA, including exposure of the fusion peptide and the kink region of the HA2 subunit, proceed rapidly (within a minute) even at 4°C (6), this temperature dramatically inhibits late stages of restructuring of HA, detected either as dissociation of HA1 trimer or as functional inactivation of HA treated with acidic pH in the absence of a target membrane (6,26,27).

Fusion is also inhibited at 4°C. In the case of influenza virus fusing with RBC or fusogenic liposomes, there is slow lipid mixing, reaching rather high extents, proceeding even on reneutralization (6). X-31 viral particles fuse with large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) at pH 5.0, 3°C (41), and with RBCs at pH 4.8, 4°C (16). In contrast, in the case of HA-cell fusing with RBCs at 4°C, there is no lipid mixing until the temperature is raised (10). In this study, we reconstituted both of these fusion phenotypes at 4°C in fusion of HA-cells with liposomes of different compositions: the complete block of lipid mixing and slow lipid mixing. Thus, for the same number of HA-cells, the phenotype of lipid mixing depends on the properties of the target membrane.

Fusogenic properties and lipid composition

As reported earlier (17), the efficiency of HA-mediated fusion depends on the lipid composition of the target membrane. Different lipids can alter the fusogenicity of the liposome membrane by different mechanisms. The effects of the nonbilayer lipids on HA-mediated fusion and on many other fusion reactions are, in general, consistent with the predictions of the stalk-pore hypothesis, which suggests that two subsequent fusion intermediates, a local hemifusion connection (referred to as a stalk) and a fusion pore, are formed by contacting and distal monolayers, respectively (9,10,17,42). Gangliosides, known to serve as HA-receptors, likely improve the quality (tightness and area) of the membrane contact or directly affect the restructuring of HA (43). Ganglioside GD1a promotes a slightly faster initial rate of fusion than does GD1b (44). Bipolar lipids might inhibit fusion stages, such as hemifusion, that require peeling of the two monolayers of the same membrane from each other (14,45).

For liposomes formed from the mixture of cholesterol and different species of PC, liposomes containing PC with unsaturated acyl chains support HA-mediated fusion better than do liposomes formed of saturated lipid (this work and 46). We still do not know the specific mechanisms underlying the higher rates and extents of lipid mixing for DOPC- versus SOPC- versus DSPC-containing liposomes. Although our liposome compositions contained 5 mol % rhodamine-labeled PE and 5 mol % disialoganglioside, we assume that the mechanical properties of the bilayers and, in particular, the differences in their fusogenicity were determined mainly by the major components of the liposome composition: PC and cholesterol. The concentration of cholesterol in the liposomes used, 40.5 mol %, was chosen to mimic the composition typical for many biological membranes including RBC (∼40 mol % (47)). SOPC-containing bilayers, in a first approximation, behave like many natural membranes. Indeed, for the SOPC bilayer with 40 mol % cholesterol, the elastic area compressibility modulus is rather close to that for bilayers from RBC lipids including native cholesterol (∼500 vs. ∼400 dyn/cm (47)). Although the majority of natural PC molecules, as does SOPC, have one saturated and one unsaturated tail, two PC components studied in this work, DOPC and DSPC, were chosen to represent certain extremes.

Because all these phospholipids share the same phosphatidylcholine polar group, any difference must be caused by the acyl composition. DOPC, SOPC, and DSPC have very different gel-to-liquid crystalline phase transition temperatures (−20, 6, and 55°C, respectively). Published values of the bending moduli, the elastic stretch moduli, and the rupture tensions for cholesterol-free bilayers made of SOPC and DOPC are much closer to each other than either is to DSPC (48,49). Therefore, one can be surprised that SOPC-containing bilayers were found to be much closer to DSPC- than to DOPC-containing bilayers as the target membranes in HA-mediated fusion at 4°C. However, the mechanical properties of the bilayers are profoundly changed by the presence of cholesterol. Cholesterol-phospholipid interaction increases membrane cohesion, and, at ∼50 mol %, cholesterol is expected to significantly decrease or abolish the specific heat associated with the phase transition (50). The curvature elasticity for SOPC membranes saturated with cholesterol is ∼3-fold larger than that for cholesterol-free SOPC membrane (51). Cholesterol also shifts the spontaneous curvature of lipid monolayer to more negative values (52).

Although we do not know the exact difference between the mechanical properties of the bilayers of the studied compositions at 4°C, membranes containing PC with higher degrees of unsaturation likely remain more deformable and, in addition, have more negative spontaneous curvature. Thus, DOPC/cholesterol bilayers are expected to form bent fusion intermediates more readily and thus to support fusion better than SOPC/cholesterol and DSPC/cholesterol bilayers. Similarly, lipid bilayers of any composition are expected to bend and to fuse more readily at 37°C than at 4°C. The energy of fusion intermediates should be higher, and thus their formation inhibited, for DSPC and at 4°C than for DOPC and at 37°C. For lower energies, one may expect facilitated formation of the fusion intermediates.

Two distinct fusion intermediates

Low-pH application at 4°C yielded potentially fusogenic liposome-cell contacts (fusion intermediates) that differed in their potential to advance to fusion. For DOPC-LS, some 55% of liposome-cell contacts yielded lipid mixing at 4°C after fusion for 1 h. The remaining 45% of the contacts neither yielded fusion nor inactivated (these fusion intermediates yielded fusion after the temperature was raised). For DSPC-LS, whereas half of fusion intermediates at 4°C inactivated with time at low pH, half remained stable and produced lipid mixing after the temperature was raised. These partial-fusion and partial-inactivation phenotypes indicate that for each of the liposome compositions there are two distinct types of fusion intermediates. One can hypothesize that two kinds of HA intermediates (one for DOPS-LS, and one for DSPC-LS), which neither inactivate nor yield lipid mixing at 4°C, can be identified as the same intermediate characterized by a particularly stable structure. However, significant promotion of HA-cell/liposome fusion by calcium chloride (5 mM) at 37°C at neutral pH after incubation at 4°C at pH 4.9 for 30 or 60 min, from the stable intermediate for DOPC-LS, and the absence of such a promotion in the case of DSPC-LS (M. A. Zhukovsky and L. V. Chernomordik, unpublished data), argues against such a hypothesis. Examination of the fusion of viral particles with liposomes also argues against the existence of such an intermediate that neither inactivates nor yields lipid mixing at 4°C: in the case of DSPC-LS, no HA molecules inactivate, whereas in the case of DOPC-LS, all HA molecules that yield lipid mixing at 37°C also yield lipid mixing at 4°C.

One can also hypothesize that for any composition of target membrane, only one intermediate exists, and this intermediate yields higher fusion with DOPC-LS than for DSPC-LS because of inherent differences of fusogenicity of lipids. However, it is difficult to imagine that for the same LS composition such a single intermediate produces partial fusion or undergoes partial inactivation even after very long incubations at 4°C.

The two types of distinct fusion intermediates, and the effects of the target membrane on their properties, might be explained by the heterogeneity of the cell membrane and, in particular, by heterogeneous distribution of HA molecules at the cell surface. Because the surface density of fusion proteins determines the rates, the extents, and even the phenotype of fusion, we hypothesize that for liposomes of the same composition, fusion and inactivation patterns might differ in a manner dependent on the local HA concentration in the membrane patch under the liposome. We suggest that liposomes bound at regions of the cell with a High Density of HA (HD-HA sites) yield at 4°C, in the case of DOPC-LS, lipid mixing and, in the case of DSPC-LS, stable fusion intermediates that do not inactivate with time but yield lipid mixing only at 37°C. In contrast, liposomes bound at the regions with a Low Density of HA (LD-HA sites) yield, in the case of DOPC-LS, fusion intermediates that do not support lipid mixing at 4°C but are stable and produce fusion on a rise in the temperature to 37°C. DSPC-LS at the LD-HA sites establish short-lived intermediates that yield lipid mixing only at 37°C and only if low-pH incubation at 4°C was relatively short. We see that more fusogenic target membrane and, possibly, higher HA surface density can prevent HA inactivation at low temperatures. If we can assume that both fusion and inactivation involve an irreversible conformational change of HA (53), the increase in fusogenicity of the target membrane or in HA surface density might favor the fusion pathway versus the inactivation one.

The suggested relationship between fusion and inactivation patterns and local HA density is supported by the lack of either partial lipid mixing or partial inactivation phenotypes in liposome fusion to viral particles with a homogeneously high density of HA. For both DSPC-LS and DOPC-LS, fusion and inactivation at 4°C were found to proceed as expected for the given lipid composition, but only at sites with high HA density. It would be interesting to study another extreme: fusion of liposomes with the membrane expressing homogeneously low density of HA. Unfortunately, it is a very difficult experiment: even for very low average densities of HA molecules, some patches of the membrane can always have high HA density.

A recent finding (54) suggests that our results are applicable to other viruses: the efficiency of low-pH-dependent cell-cell fusion at 37°C, mediated by Env, the fusion protein of avian sarcoma and leukosis virus, was found to partially decrease with an increase in time of incubation at 4°C in the presence of the target membrane after a low-pH triggering event. This partial decrease could be a manifestation of the presence of both low and high surface densities of fusion proteins in this system.

The similarity of the shapes of the time traces corresponding to fusion after different durations of incubation of HA-cells with DSPC-LS at pH 4.9 (Fig. 2 C) can be explained in the following way. The transition from early and reversible conformation(s) of low-pH-activated HA toward an irreversible protein conformation underlies both HA-mediated fusion and HA inactivation (4,27). Inactivation of LD-HA molecules with time at 4°C results in transition of LD-HA molecules from a reversibly activated to an inactivated conformation. It causes reduction in the number of fusion machines available for fusion at 37°C but does not change the efficiency of fusion mediated by these fusion machines at this temperature.

To conclude, we explored here the diversity of the fusion intermediates formed by HA at different temperatures and for different target membranes. We found that even for the same target membrane composition, at low (4°C) temperature HA forms two types of intermediates: HD and LD. Intermediate HD is more stable and more fusogenic than LD; behavior of the system at 4°C also depends on the composition of the target membrane. The diversity of the fusion intermediates formed in different contact sites might reflect the heterogeneous distribution of HA in the cell membrane. This diversity is likely a general feature of the biological membrane fusion reaction (19) because biological membranes are heterogeneous in their lipid composition and in the distribution of proteins that regulate fusion (for instance, receptors that trigger conformational change of the fusion proteins such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) Env), and fusion proteins themselves.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge helpful discussions with Drs. Vadim Frolov, Mikhail Kozlov, Kamran Melikov, and Joshua Zimmerberg. The authors also thank Dr. Robert A. Lamb (Northwestern University, Evanston, IL) for SV40 recombinant viral vector and Drs. Barry R. Lentz and Md. Emdadul Haque (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC) for purified polyethylene glycol (PEG).

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Ingrid Markovic's present address is Division of Therapeutic Proteins, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Food and Drug Administration, Bethesda, MD 20892.

Austin L. Bailey's present address is Medical Science Liaison, Oncology, Scientific Communications, Cephalon Inc., Hoboken, NJ 07030.

References

- 1.White, J. M. 1995. Membrane fusion: The influenza paradigm. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 60:581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skehel, J. J., and D. C. Wiley. 2000. Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: The influenza hemagglutinin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:531–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skehel, J. J., P. M. Bayley, E. B. Brown, S. R. Martin, M. D. Waterfield, J. M. White, I. A. Wilson, and D. C. Wiley. 1982. Changes in the conformation of influenza virus hemagglutinin at the pH optimum of virus-mediated membrane fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 79:968–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markovic, I., E. Leikina, M. Zhukovsky, J. Zimmerberg, and L. V. Chernomordik. 2001. Synchronized activation and refolding of influenza hemagglutinin in multimeric fusion machines. J. Cell Biol. 155:833–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tamm, L. K., J. Crane, and V. Kiessling. 2003. Membrane fusion: a structural perspective on the interplay of lipids and proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 13:453–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stegmann, T., J. M. White, and A. Helenius. 1990. Intermediates in influenza induced membrane fusion. EMBO J. 9:4231–4241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shangguan, T., D. Alford, and J. Bentz. 1996. Influenza virus-liposome lipid mixing is leaky and largely insensitive to the material properties of the target membrane. Biochemistry. 35:4956–4965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kemble, G. W., T. Danieli, and J. M. White. 1994. Lipid-anchored influenza hemagglutinin promotes hemifusion, not complete fusion. Cell. 76:383–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melikyan, G. B., S. A. Brener, D. C. Ok, and F. S. Cohen. 1997. Inner but not outer membrane leaflets control the transition from glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored influenza hemagglutinin-induced hemifusion to full fusion. J. Cell Biol. 136:995–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chernomordik, L. V., V. A. Frolov, E. Leikina, P. Bronk, and J. Zimmerberg. 1998. The pathway of membrane fusion catalyzed by influenza hemagglutinin: restriction of lipids, hemifusion, and lipidic fusion pore formation. J. Cell Biol. 140:1369–1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Meer, G., J. Davoust, and K. Simons. 1985. Parameters affecting low-pH-mediated fusion of liposomes with the plasma membrane of cells infected with influenza virus. Biochemistry. 24:3593–3602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellens, H., S. Doxsey, J. S. Glenn, and J. M. White. 1989. Delivery of macromolecules into cells expressing a viral membrane fusion protein. Methods Cell Biol. 31:155–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellens, H., J. Bentz, D. Mason, F. Zhang, and J. M. White. 1990. Fusion of influenza hemagglutinin-expressing fibroblasts with glycophorin-bearing liposomes: role of hemagglutinin surface density. Biochemistry. 29:9697–9707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bailey, A., M. Zhukovsky, A. Gliozzi, and L. V. Chernomordik. 2005. Liposome composition effects on lipid mixing between cells expressing influenza virus hemagglutinin and bound liposomes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 439:211–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Puri, A., F. P. Booy, R. W. Doms, J. M. White, and R. Blumenthal. 1990. Conformational changes and fusion activity of influenza virus hemagglutinin of the H2 and H3 subtypes: effects of acid pretreatment. J. Virol. 64:3824–3832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schoch, C., R. Blumenthal, and M. J. Clague. 1992. A long-lived state for influenza virus-erythrocyte complexes committed to fusion at neutral pH. FEBS Lett. 311:221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chernomordik, L. V., E. Leikina, V. Frolov, P. Bronk, and J. Zimmerberg. 1997. An early stage of membrane fusion mediated by the low pH conformation of influenza hemagglutinin depends upon membrane lipids. J. Cell Biol. 136:81–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leikina, E., I. Markovic, L. V. Chernomordik, and M. M. Kozlov. 2000. Delay of influenza hemagglutinin refolding into a fusion-competent conformation by receptor binding: A hypothesis. Biophys. J. 79:1415–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leikina, E., and L. V. Chernomordik. 2000. Reversible merger of membranes at the early stage of influenza hemagglutinin-mediated fusion. Mol. Biol. Cell. 11:2359–2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mittal, A., E. Leikina, L. V. Chernomordik, and J. Bentz. 2003. Kinetically differentiating influenza hemagglutinin fusion and hemifusion machines. Biophys. J. 85:1713–1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frolov, V., M. S. Cho, P. Bronk, T. Reese, and J. Zimmerberg. 2000. Multiple local contact sites are induced by GPI-linked influenza hemagglutinin during hemifusion and flickering pore formation. Traffic. 1:622–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leikina, E., A. Mittal, M. S. Cho, K. Melikov, M. M. Kozlov, and L. V. Chernomordik. 2004. Influenza hemagglutinins outside of the contact zone are necessary for fusion pore expansion. J. Biol. Chem. 279:26526–26532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melikyan, G. B., H. Jin, R. A. Lamb, and F. S. Cohen. 1997. The role of the cytoplasmic tail region of influenza virus hemagglutinin in formation and growth of fusion pores. Virology. 235:118–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melikyan, G. B., R. M. Markosyan, H. Hemmati, M. K. Delmedico, D. M. Lambert, and F. S. Cohen. 2000. Evidence that the transition of HIV-1 gp41 into a six-helix bundle, not the bundle configuration, induces membrane fusion. J. Cell Biol. 151:413–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Markosyan, R. M., G. B. Melikyan, and F. S. Cohen. 2001. Evolution of intermediates of influenza virus hemagglutinin-mediated fusion revealed by kinetic measurements of pore formation. Biophys. J. 80:812–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White, J. M., and I. A. Wilson. 1987. Anti-peptide antibodies detect steps in a protein conformational change: low-pH activation of the influenza virus hemagglutinin. J. Cell Biol. 105:2887–2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leikina, E., C. Ramos, I. Markovic, J. Zimmerberg, and L. V. Chernomordik. 2002. Reversible stages of the low-pH-triggered conformational change in influenza virus hemagglutinin. EMBO J. 21:5701–5710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lentz, B. R., G. F. McIntyre, D. J. Parks, J. C. Yates, and D. Massenburg. 1992. Bilayer curvature and certain amphipaths promote poly(ethylene glycol)-induced fusion of dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine unilamellar vesicles. Biochemistry. 31:2643–2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bailey, A. L., and P. R. Cullis. 1997. Membrane fusion with cationic liposomes: effects of target membrane lipid composition. Biochemistry. 36:1628–1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slepushkin, V. A., A. I. Starov, A. G. Bukrinskaya, A. B. Imbs, M. A. Martynova, L. S. Kogtev, E. L. Vodovozova, N. G. Timofeeva, J. G. Molotkovsky, and L. D. Bergelson. 1988. Interaction of influenza virus with gangliosides and liposomes containing gangliosides. Eur. J. Biochem. 173:599–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin, H., G. P. Leser, and R. A. Lamb. 1994. The influenza virus hemagglutinin cytoplasmic tail is not essential for virus assembly or infectivity. EMBO J. 13:5504–5515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jin, H., K. Subbarao, S. Bagai, G. P. Leser, B. R. Murphy, and R. A. Lamb. 1996. Palmitylation of the influenza virus hemagglutinin (H3) is not essential for virus assembly or infectivity. J. Virol. 70:1406–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoekstra, D., T. de Boer, K. Klappe, and J. Wilschut. 1984. Fluorescence method for measuring the kinetics of fusion between biological membranes. Biochemistry. 23:5675–5681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weber, T., G. Paesold, C. Galli, R. Mischler, G. Semenza, and J. Brunner. 1994. Evidence for H(+)-induced insertion of influenza hemagglutinin HA2 N-terminal segment into viral membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 269:18353–18358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Günther-Ausborn, S., A. Praetor, and T. Stegmann. 1995. Inhibition of influenza-induced membrane fusion by lysophosphatidylcholine. J. Biol. Chem. 270:29279–29285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scheiffele, P., M. G. Roth, and K. Simons. 1997. Interaction of influenza virus haemagglutinin with sphingolipid-cholesterol membrane domains via its transmembrane domain. EMBO J. 16:5501–5508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiley, D. C., and J. J. Skehel. 1987. The structure and function of the hemagglutinin membrane glycoprotein of influenza virus. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 56:365–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pak, C. C., M. Krumbiegel, and R. Blumenthal. 1994. Intermediates in influenza virus PR/8 haemagglutinin-induced membrane fusion. J. Gen. Virol. 75:395–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Korte, T., K. Ludwig, F. P. Booy, R. Blumenthal, and A. Herrmann. 1999. Conformational intermediates and fusion activity of influenza virus hemagglutinin. J. Virol. 73:4567–4574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Epand, R. M., R. F. Epand, I. Martin, and J. M. Ruysschaert. 2001. Membrane interactions of mutated forms of the influenza fusion peptide. Biochemistry. 40:8800–8807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsurudome, M., R. Gluck, R. Graf, R. Falchetto, U. Schaller, and J. Brunner. 1992. Lipid interactions of the hemagglutinin HA2 NH2-terminal segment during influenza virus-induced membrane fusion. J. Biol. Chem. 267:20225–20232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chernomordik, L. 1996. Non-bilayer lipids and biological fusion intermediates. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 81:203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stegmann, T., I. Bartoldus, and J. Zumbrunn. 1995. Influenza hemagglutinin-mediated membrane fusion: influence of receptor binding on the lag phase preceding fusion. Biochemistry. 34:1825–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramalho-Santos, J., and M. C. Pedroso de Lima. 2004. The role of target membrane sialic acid residues in the fusion activity of the influenza virus: The effect of two types of ganglioside on the kinetics of membrane merging. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 9:337–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Relini, A., D. Cassinadri, Q. Fan, A. Gulik, Z. Mirghani, M. De Rosa, and A. Gliozzi. 1996. Effect of physical constraints on the mechanisms of membrane fusion: bolaform lipid vesicles as model systems. Biophys. J. 71:1789–1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kawasaki, K., and S. Ohnishi. 1992. Membrane fusion of influenza virus with phosphatidylcholine liposomes containing viral receptors. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 186:378–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Needham, D., and R. S. Nunn. 1990. Elastic deformation and failure of lipid bilayer membranes containing cholesterol. Biophys. J. 58:997–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hunter, D. G., and B. J. Frisken. 1998. Effect of extrusion pressure and lipid properties on the size and polydispersity of lipid vesicles. Biophys. J. 74:2996–3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rawicz, W., K. C. Olbrich, T. McIntosh, D. Needham, and E. Evans. 2000. Effect of chain length and unsaturation on elasticity of lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 79:328–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ladbrooke, B. D., R. M. Williams, and D. Chapman. 1968. Studies on lecithin-cholesterol-water interactions by differential scanning calorimetry and X-ray diffraction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 150:333–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Song, J., and R. E. Waugh. 1993. Bending rigidity of SOPC membranes containing cholesterol. Biophys. J. 64:1967–1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen, Z., and R. P. Rand. 1997. The influence of cholesterol on phospholipid membrane curvature and bending elasticity. Biophys. J. 73:267–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carr, C. M., C. Chaudhry, and P. S. Kim. 1997. Influenza hemagglutinin is spring-loaded by a metastable native conformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:14306–14313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Markosyan, R. M., P. Bates, F. S. Cohen, and G. B. Melikyan. 2004. A study of low pH-induced refolding of Env of avian sarcoma and leukosis virus into a six-helix bundle. Biophys. J. 87:3291–3298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]