Abstract

The present study was undertaken to analyze the effect of a P450 aromatase inhibitor (finrozole) on 4-month-old transgenic mice expressing human P450 aromatase (P450arom) under the human ubiquitin C promoter (AROM+). AROM+ mice present several dysfunctions, such as adrenal and pituitary hyperplasia, cryptorchidism, Leydig cell hypertrophy and hyperplasia, and gynecomastia. The present study demonstrates that these abnormalities were efficiently treated by administration of a P450arom inhibitor, finrozole. The treatment normalized the reduced intratesticular and serum testosterone levels, while those of estradiol were decreased. The body weight and several affected organ weights were normalized with the treatment. Histological analysis revealed that both the pituitary and adrenal hyperplasia were diminished. Furthermore, the cryptorchid testes present in the untreated AROM+ males descended to scrotum, 4 to 15 days after inhibitor treatment. In addition, the disrupted spermatogenesis was recovered and qualitatively complete spermatogenesis appeared with the inhibitor treatment. This was associated with normalized structure of the interstitial tissue, as analyzed by immunohistochemical staining for Leydig cells and macrophages. One of the features was that the Leydig cell hypertrophy was markedly diminished in the treated mice. AROM+ mice also present with severe gynecomastia, while the development and differentiation of the mammary gland in AROM+ males was markedly diminished with the inhibitor treatment. Interestingly, the mammary gland involution was associated with the induction of androgen receptor in the epithelial cells, while estrogen receptors were still detectable in the epithelium. The data show that AROM+ mouse model is a novel tool to further analyze the use of P450arom inhibitors in the treatment of the dysfunctions in males associated with misbalanced estrogen to androgen ratio, such as pituitary adenoma, testicular dysfunction, and gynecomastia.

Aromatase P450 (P450arom) enzyme is the product of the Cyp19 gene.1 The enzyme catalyzes aromatization of the A-ring of androgens such as testosterone (T) and androstenedione, resulting in formation of the phenolic A-ring characteristic of the estrogens, estradiol (E2), and estrone, respectively.2,3 Together with 17β-hydoxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (17β-HSD type 1), P450arom catalyzes the final steps in ovarian E2 biosynthesis, but the enzyme is also widely expressed in female and male extragonadal tissues, suggesting a role for the enzyme in the local, intracrine, estrogen production. However, the extragonadal tissues lack the capacity to synthesize androgenic precursors, and estrogen production is dependent on the precursors produced in the classical steroidogenic organs; ie, the gonads and the adrenal glands.

Aberrant estrogenic stimulation has been shown to be involved in several clinical manifestations in both sexes. Most important is the tight connection between estrogens and neoplastic transformation of breast and endometrial epithelium.4–6 Other clinical manifestations related to estrogens include gynecomastia,7 delayed puberty,8,9 ovulatory dysfunctions, and endometriosis.6 Also, several studies on mice indicate that prenatal or early postnatal exposure to exogenous estrogens induces severe and persistent changes in the structure and function of the male reproductive organs, such as atrophic and small testes, epididymal cysts, abnormalities in the rete testis, and underdevelopment of the accessory sex glands.10–12 Estrogens may also have a pivotal role in the mechanisms leading to male reproductive tract malformations such as cryptorchidism, enlarged prostatic utricle, and testicular11–14 and prostatic tumors.15

Because unopposed estrogen action may lead to a number of severe health problems, the development of efficient therapies to block or reduce estrogen action is of key importance. Two different approaches are available: to reduce the systemic or local estrogen levels in the target tissues by P450arom inhibitors,16 or to block estrogen action at the receptor level with antiestrogens.17 Both strategies have been pursued for several decades, and new molecules are continuously under development. The existence of two distinct estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ) has made the development of pure antiestrogens a complex issue.18 However, this together with the new knowledge on estrogen-dependent gene activation has raised the possibility to further develop tissue-specific antiestrogens and selective estrogen receptor modulators. So far, in the human, only one gene for P450arom has been identified,19 indicating that full inhibition of the enzyme would result in total blockage of estrogen production from androgenic precursors, both in men and women. Hence, P450arom is a good target for inhibiting estrogen-dependent processes, without affecting the production of other steroid hormones.20 Recent studies have documented the clinical efficacy of P450arom inhibition in the treatment of breast cancer and endometriosis.21–23 In addition, P450arom inhibitors have been used to treat boys with delayed puberty, to improve the expected height.9 Furthermore, ongoing studies address the possibility of using P450arom inhibitors in the treatment of gynecomastia and premature puberty.7,24

We have recently generated a transgenic mouse model expressing human P450arom under the human ubiquitin C promoter (AROM+). These mice present a multitude of severe structural and functional alterations in the male reproductive tract, such as cryptorchidism, Leydig cell hypertrophy and hyperplasia, and disrupted spermatogenesis.25 Furthermore, the mammary glands of the AROM+ males undergo ductal and alveolar development resembling morphologically that of terminally differentiated female mammary glands, including the expression of mRNA for the milk protein β-casein. In addition to the reproductive defects, the AROM+ male mice present with enlarged size of adrenals and pituitary, and reduced body weight at young adult age. The present study was undertaken to analyze the effect of a P450arom inhibitor, finrozole, on the male AROM+ phenotype. Interestingly, the study showed that the severe phenotype in AROM+ males could be largely normalized by the inhibitor treatment. Thus, AROM+ mouse model is a novel tool for evaluating the use of P450arom inhibitors in males in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Transgenic Mouse Line Expressing Human P450 Aromatase (AROM+)

The generation of the transgenic mice expressing human P450arom cDNA under the control of the ubiquitin C promoter (AROM+) has been described previously.25 The AROM+ female mice were maintained in a standard colony and used as breeders, and genotyping of the AROM+ mice was carried out as described previously.25 The mice had free access to soy-free food pellets (SDS; Witham, Essex, England) and tap water. All mice were handled in accordance with the institutional animal care policies of the University of Turku (Turku, Finland).

Investigational Drug and Control Substances

Four-month-old wild-type (WT) and AROM+ males were divided into two groups: one group served as control group (placebo), the other group received the inhibitor (n = 10). The vehicle was prepared as follows: 0.25 g carboxylmethylcellulose (Tamro Ltd., Vantaa, Finland) was weighed and solubilized in 50 ml of deionized water. The solution was prepared once per week and stored at 4°C. An appropriate amount of a P450arom inhibitor, finrozole, MPV-2213ad, (Hormos Medical Ltd., Turku, Finland) was weighed in a transparent glass mortar. A few drops of the vehicle were added, and the mixture was thoroughly mixed. Thereafter, one-third of the final volume of the vehicle was added to the mortar and placed into an ultrasonic incubator for 5 minutes. This procedure was completed a total of three times to reach the final volume. The dose of finrozole was 10 mg/kg of body weight, and it was given daily to mice by gavage in 0.2 ml for 6 weeks.

Morphological and Histological Assessment of Organs

After a 6-week-long finrozole treatment, body weight was recorded and compared to the weight measured before the treatment. The testis descending was tested as follows: abdomen of each mouse was pressed continuously with two fingers. To press the testis from abdomen to scrotum, the fingers were slid in caudal direction. If the testes were not able to descend to scrotum, the mouse was considered as cryptorchid. After the inhibitor treatment, the mice were anesthetized with 300–500 μl of 2.5% avertin, and blood was collected by a cardiac puncture. The organs were rapidly excised and weighed. Thereafter, samples were collected by freezing in liquid nitrogen or by fixing with 4% paraformaldehyde, and fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin. For histological and immunohistochemical analysis 4-μm-thick sections were deparaffinized in xylene and ethanol, and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Hormone Measurements

Serum samples were separated by centrifugation and stored at −20°C until hormone concentrations were measured. Serum levels of T, luteinizing hormone (LH) were measured as previously described.25,27,28 For measuring the intratesticular E2 and T, testis (half testis) was homogenized in 0.5 ml PBS. Thereafter, the E2 and T were extracted from the homogenate using diethyl ether. After extraction, the organic phase was evaporated into dryness, the steroids were solubilized in an aliquot of PBS, and measured by radioimmunoassay following the manufacturer’s protocols for serum samples (Wallac Oy, Turku, Finland). The sensitivity of estradiol is 0.05 nmol/ml. T was performed by radioimmunoassay after diethyl ether extraction, as described previously.28

Immunohistochemistry

Four-micrometer-thick sections were cut from paraffin-embedded tissues and mounted on slides. After deparaffinization and rehydration in xylene and ethanol, they were placed in 10 mmol/L citrate buffer (pH6.0), followed by heating in a microwave oven for antigen retrieval. For this, three periods of 5 minutes each were used, after which the sections were treated with 3% H2O2 in PBS (pH 7.6) for 20 minutes. The sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C in PBS containing 3% BSA and one of the following antibodies: 1) antibody against 3βHSD1 (rabbit polyclonal IgG) used at a 1:1000 dilution (provided by Anita H. Payne, Stanford University School of Medicine, CA), 2) antibody against estrogen receptor α (rabbit polyclonal IgG; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) used at a 1:200 dilution, 3) antibody against ERβ (chicken polyclonal IgG; provided by J. Å. Gustafsson, Department of Medical Nutrition, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden) used at a 1:1000 dilution, 4) antibody against activated signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (Stat 5; mouse monoclonal IgG; Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) used at a 1:500 dilution, 5) antibody against Prl (rabbit polyclonal antiserum; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) used at a 1:500 dilution, 6) antibody against F4/80 macrophage marker (rat polyclonal IgG2b, Serotec Ltd. Oxford, UK) used at a 1:50 dilution, 7) antibody against androgen receptor (rabbit polyclonal IgG, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) used at a 1:500 dilution, and 8) antibody against PCNA (mouse monoclonal IgG, NovoCastra, Newcastle, UK) used at 1:200 dilution.

The primary antibody bound was detected by using biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG, rabbit anti-mouse IgG or mouse anti-rat IgG (1:200 dilution) followed by incubation with avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The sections with ERβ antibody were incubated with peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-chicken IgG (1:1000 dilution). The specific binding was visualized by using 3′−3′ diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride. Sections were slightly counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin and mounted.

Statistics

SigmaStat software (SigmaStat 2.03 for Windows; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for one-way analysis of variance and differences between individual means were assessed by all-pairwise multiple comparison procedures (Student-Newman-Keuls test for T, E2, and LH, and Duncan’s tests for testis, adrenal, and pituitary gland).

Results

In the recent study we evaluated the response of 4-month-old male mice expressing P450arom on a P450arom inhibitor. The data show a strong treatment response in the weight of various affected organs. The changes were further analyzed in cellular level by performing histological analyses of the affected organs, while immunohistochemical analyses and hormonal measurements were used to define signaling systems involved.

Hormone Concentrations in AROM+ Males after Finrozole Treatment

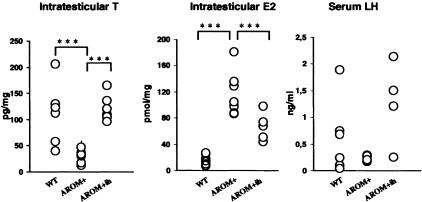

To analyze the consequences of the P450arom inhibitor on testicular steroid production, intratesticular T and E2 concentrations were measured in inhibitor-treated AROM+ males, and compared with the placebo-treated AROM+ and non-treated and treated WT males. Furthermore, serum levels of T and LH were measured. Significantly increased intratesticular E2 concentration (P < 0.001) was found in AROM+ males in connection with a decreased T (P > 0.001; Figure 1). The low level of testicular T was reflected to a markedly lowered level of circulating T, as also reported previously.28 As expected, the elevated intratesticular E2 present in AROM+ was significantly reduced by the finrozole treatment (Figure 1), although it still remained four-fold higher as compared to the level found in placebo-treated WT mice. In contrast to the reduced E2, intratesticular T concentration was increased in the AROM+ males after inhibitor treatment, reaching the level found in WT mice (P = 0.6; Figure 1). In line with our previous results no significant difference was found in the serum LH concentrations (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Intratesticular T and E2, serum LH concentrations in control and finrozole-treated AROM+ male mice and in WT males. Asterisks indicate a significant difference (***, P < 0.001).

Body and Organ Weights, and Histology of Non-Reproductive Tissues Are Restored by Finrozole Treatment

The comparison of organ weights in placebo and finrozole-treated WT and AROM+ male mice are presented in Table 1. All abnormalities in organ weights induced by the increased E2 to T ratio were found to be either partially or totally reversible. In AROM+ mice the lowered body weights were normalized by the finrozole treatment, in line with the anabolic effect of the increased circulating T concentration. The increased serum T concentration in the treated AROM+ mice is in line with the significantly increased testis and seminal vesicle weight in these males (Table 1).

Table 1.

Body and Organ Weights of Different Groups of Animals

| Weight (g) | WT-placebo | WT-inhibitor | AROM+-placebo | AROM+-inhibitor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight | 30.44 ± 2.98 | 31.16 ± 2.74 | 25.07 ± 2.56 | 30.46 ± 3.05* |

| Testis | 0.093 ± 0.007 | 0.081 ± 0.007 | 0.059 ± 0.0197 | 0.100 ± 0.007* |

| Pituitary | 0.0017 ± 0.002 | 0.0019 ± 0.003 | 0.0054 ± 0.001 | 0.0029 ± 0.003* |

| Adrenal | 0.0016 ± 0.0002 | 0.0015 ± 0.0003 | 0.0061 ± 0.001 | 0.0031 ± 0.0005* |

| Seminal vesicle | 0.047 ± 0.0106 | 0.0495 ± 0.0091 | 0.0017 ± 0.0061 | 0.0096 ± 0.0424* |

Statistical analyses were carried out to compare all the groups together, but significance is shown only for the data between AROM+-placebo and AROM+-inhibitor groups. Asterisks indicate a significant difference (*, P < 0.01).

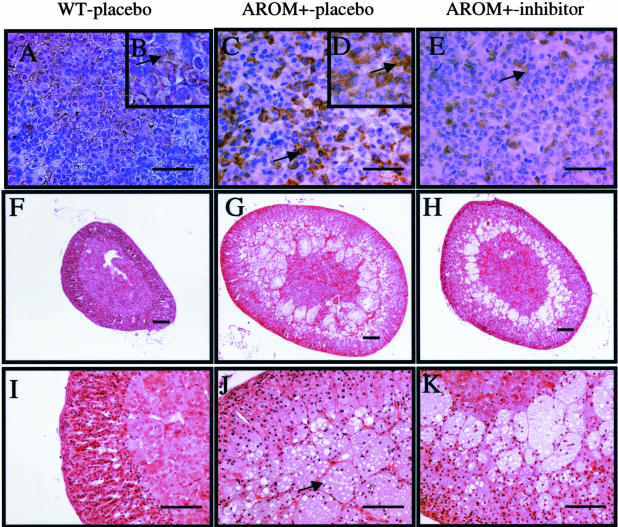

AROM+ males were previously shown to have increased pituitary size and highly elevated concentrations of serum Prl.25 The inhibitor treatment resulted in a marked inhibition of the growth of the pituitary in AROM+ males (Table 1), and immunohistochemistry revealed that the amount of prolactin production in the pituitary was strikingly decreased in inhibitor-treated AROM+ males as compared with placebo-treated AROM+ males (Figure 2, A–E).

Figure 2.

A–E: Localization of Prl-producing cells in the pituitary gland. Pituitary sections from WT mice (A and B), AROM+-placebo (C and D), and finrozole-treated AROM+ (E) male mice were stained with an antibody to rat Prl. Higher magnifications (B and D) indicate specific brown staining in the cytoplasm (arrows). F–K: Histology of the adrenal gland in WT (F and I), AROM+-placebo (G and J), and finrozole-treated AROM+ (H and K) male mice. In AROM+-placebo mice, large vacuole-filled cells appeared in the innermost cortex (J, arrow). The thickness of the cell layer was reduced after finrozole treatment (H and K). Scale bars: 50 μm (A, C, E), 100 μm (F–K).

In agreement with our previous study, the weights of the adrenal glands in the placebo-treated AROM+ mice were more than three-fold higher than those in the WT mice. Inhibitor treatment reduced the growth of the adrenals in AROM+ mice, resulting to a 50% smaller adrenal size in the inhibitor-treated AROM+ males as compared with the placebo-treated AROM+ males (Table 1; Figure 2, F–H). Histological analysis furthermore showed that the number of large vacuole-filled cells in the innermost AROM+ adrenal cortex was reduced by the finrozole treatment (Figure 2, F–K).

Reversal of Testicular Structure and Function by Finrozole Treatment in AROM+ Males

One of the interesting features of the inhibitor treatment was that the cryptorchid testes of the AROM+ males descended into scrotum with 100% penetrance, 4 to 15 days (median 12 days) after starting the finrozole treatment (Figure 3A). This was associated with a recovery of the androgen production and testicular function. The intraabdominal descent of the testes was normal in AROM+ mice, as indicated by the fact that that in newborn mice the testes were located at the bladder neck (Figure 3, B and C). Furthermore the intratesticular T in newborn mice was not significantly changed (Figure 3D). Hence, the cause for the cryptorchidism in AROM+ mice is likely to be due to the low postnatal serum T concentration.

Figure 3.

A: Testis descent in WT mice, and in AROM+-placebo and finrozole-treated AROM+ mice. B and C: Identical intraabdominal descent of testes in WT and AROM+ mice. D: Intratesticular T concentration in embryonic day 17.5 is identical in WT and AROM+ males.

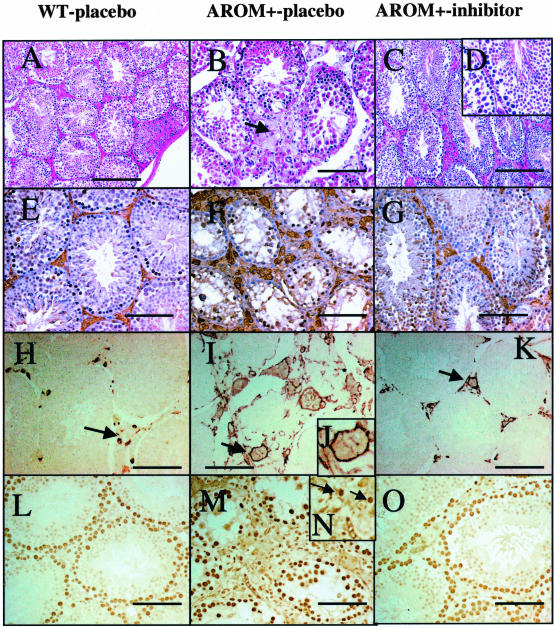

The AROM+ testes are characterized by arrested spermatogenesis. However, after finrozole treatment, spermatogenesis was normalized (Figure 4, A–D). This is indicated by the fact that the testis size was increased to its normal value (Table 1), and histological analysis revealed qualitatively normal spermatogenesis in all testes analyzed (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

A–D: Testis histology in WT (A), AROM+-placebo (B), and finrozole-treated AROM+ (C and D) mice. In AROM+ males, the Leydig cell hyperplasia and the present of giant cells were evident, and no germ cells were present in the seminiferous tubules (B). The testes phenotype is largely reversible as indicated by the normalized Leydig cell structure (C), and by the qualitatively full spermatogenesis in finrozole-treated AROM+ males (D). E–G: Immunostaining with 3βHSD1 demonstrates the number and size of Leydig cells in WT (E), AROM+-placebo (F), and finrozole-treated AROM+ (G) mice. H–K: Immunostaining of macrophages with F4/80 macrophage marker antibody in WT (H), AROM+-placebo (I and J), and finrozole-treated AROM+ (K) mice. The pericellular staining is indicated with higher magnification (J). L–O: Immunostaining with cell proliferation marker (PCNA) demonstrates the positive nuclear staining in WT testis (L), AROM+-placebo testis (M and N) and inhibitor-treated AROM+ testis (O) in Leydig cells (arrows). Scale bars: 200 μm (A–C), 100 μm (E–O).

Histological examination of the finrozole-treated AROM+ testes also revealed that the relative volume of testicular interstitial space/tubular volume reduced toward that found in WT mice. Evidently, the interstitial space in the AROM+ testes were filled with hypertrophic Leydig cells, as confirmed by immunohistochemical staining with markers, such as P450 side-chain cleavage (not shown) and 3β-hydoxysteroid dehydrogenase type I (Figure 4, E–G), while in the inhibitor-treated mice the Leydig cells clusters were smaller and triangular in shape. Furthermore, the macrophages present in the testis in AROM+ mice were increased in size (Figure 4, H–K), thereby together with the Leydig cells, they fill up the relatively large intestinal space in the placebo-treated AROM+ mice (Figure 4). Histological analysis revealed that the size of the interstitial macrophage population was normalized in the inhibitor-treated mice; however, after inhibitor treatment some large macrophages still remained in the interstitium. Furthermore, after the inhibitor treatment the seminal vesicle weights did not reach the normal size, and the hypertrophic Leydig cell still sustained in some parts of interstitial region, suggesting that the dose of finrozole (∼240 μg/kg/day) used was not high enough to completely normalize the testicular endocrine functions.

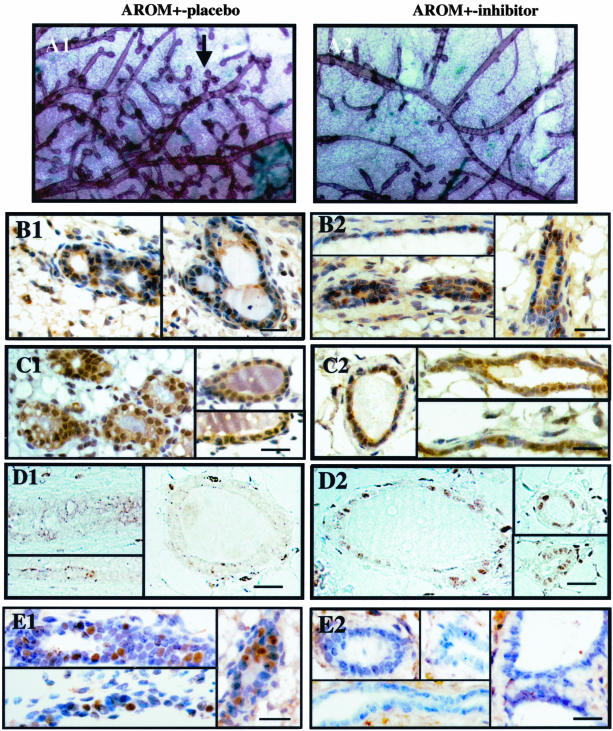

Inhibitor Treatment Induces Mammary Gland Involution in AROM+ Male Mice

AROM+ males show severe gynecomastia, with highly differentiated mammary glands (Figure 5). Interestingly, as previously reported,26 the P450arom inhibitor treatment markedly blocked the development and differentiation of the mammary gland, as shown by a whole-mount staining of the mammary gland (Figure 5A). To further study the mechanisms of the inhibitor-induced changes, certain signaling pathways were analyzed in the AROM+ mice with and without finrozole treatment. The data revealed the presence of both ERα and ERβ in the ductal or alveolar epithelium (Figure 5, B and C). To determine whether the involution of mammary gland could, at least partly, be a result of the elevated circulating T, we examined androgen receptor (AR) expression by immunohistochemistry. Surprisingly, AR was strongly expressed in the alveolar epithelium of finrozole-treated AROM+ mice, but absent in the other groups analyzed (Figure 5D). The decreased secretion of prolactin from the pituitary was in line with a reduced staining of the mammary epithelium with phosphorylated Stat5 antibody (Figure 5E).

Figure 5.

Wholemount staining of the mammary gland structure in placebo-treated (A1) and inhibitor-treated (A2) AROM+ males demonstrated the less differentiated phenotype of the inhibitor-treated AROM+ males, with less alveolar structures (arrow). B1–D2: Immunohistochemical staining of steroid receptors in AROM+ male mammary glands. Sections from placebo- and inhibitor-treated AROM+ male mice were stained with an antibody against ERα (B), ERβ (C), and AR (D). Data indicate the presence of ERs in the mammary gland epithelium in both placebo-treated and inhibitor-treated mice, while AR is markedly induced by the inhibitor treatment. E1–E2: Immunostaining for phosphotyrosine-Stat5 (D1–D2) reveals that the inhibitor treatment reduces Stat5 activation. Scale bars, 50 μm.

Discussion

The male AROM+ mice are novel tools for analyzing the effects of chronic exposure of males with elevated circulating E2, combined with a slightly reduced T concentration.25 The misbalanced sex-steroid action results in development of abnormalities in various organs, especially in the reproductive tract, and the mice are infertile. The transgene is expressed in various extragonadal tissues of the AROM+ mice, thereby also providing a local E2 producing machinery. AROM+ males display changes similar to those observed in male rodents exposed perinatally to estrogens,10,11,15 such as undescended testes, testicular interstitial cell hyperplasia, and hypoandrogenism with growth inhibition of the accessory sex glands. The recently documented reduction in reproductive health in men has been proposed also to be related to exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals with estrogenic action.29 However, the role of estrogens in this phenomenon is still under debate. The incidence of testicular cancer,30,31 hypospadias, and cryptorchidism appear to be increasing,32,33 and estrogens have been suggested to be involved in the development of the disorders, also referred to as testicular dysgenesis syndrome (TDS),34 or developmental estrogenization syndrome.35

A growing number of studies have reviewed the expression of P450arom and ERs in male reproductive system.36,37 It is evident that estrogen action is needed for normal reproductive physiology in male.19,36 ERα knockout mice show dilated lumen of the testicular seminiferous tubules, and disrupted epididymal function.38 Similarly, mice deficient in P450arom are infertile at old age.39 In addition, it has been reported that a chronic administration of a P450arom inhibitor, anastrozole, results in a significant increase in testis weight and circulating and intratesticular T concentration in rats.40 Furthermore, a recent study suggested that administration of E2 within a dose typically found in females can induce the spermatogenesis in hpg male mice, and despite of the increase in testicular weight, circulating androgen concentrations were still undetectable.41 However, the amount of E2 supporting normal testis function forms a narrow window, while animal models with mild overexpression of P450arom show testicular interstitial cell abnormalities and disrupted spermatogenesis.25,42

There is clear evidence that LH plays a pivotal role in development of the Leydig cell population and stimulating T production in adults.43,44 In addition, LH is believed to be the main trophic hormone that causes Leydig cell adenomas,43 while there is evidence showing that estrogens induce Leydig cell adenomas via their ability to increase LH action in certain strains of mice.45,46 However, our recent study showed that mice with a marked overexpression of hCG do not develop Leydig cell hyperplasia in adulthood.47 These data speak against a major role of LH as a growth stimulator in estrogen-exposed mouse testes. Furthermore, in an AROM+ mouse model the LH level is in normal range. The effects in AROM+ testes are largely recovered by finrozole as indicated by normalized Leydig cell structure and function, and by the qualitatively full spermatogenesis, further suggesting that estrogen action in the testis is the primary cause of the testicular abnormalities in AROM+ mice. Hence, more studies are emerging to analyze the direct effects of estrogens in the testis, and whether P450arom inhibitors could be beneficial in the treatment of human Leydig cell tumors remains to be studied.

AROM+ mice showed fully descended testes after finrozole treatment, and also after testicular androgen production was normalized. This gives rise to a hypothesis that P450arom inhibitors could be used to treat cryptorchidism in humans. The exact mechanisms of cryptorchidism in boys are still largely unknown, but abnormal estrogen action has been suggested as one of the possible causes.48 Fetal exposure to high concentrations of estrogens causes cryptorchidism in rodents.13,49,50 The estrogen-induced cryptorchidism is associated with down-regulating the Insl3 gene expression,50 a hormone involved in gubernaculums development responsible for trans-abdominal testis descent.51,52 However, no conclusive evidence exists for the role of Insl3 in human cryptorchidism.53,54 Our present data suggest that the Insl3-dependent intraabdominal descent had occurred normally in AROM+ males. Hence, it is likely that the lack of improper postnatal and pubertal androgen production is the main cause to their cryptorchidism. Interestingly, correcting the androgen/estrogen balance at adult age by a P450arom inhibitor treatment (present study) restored normal inguinal descent of the testes in the AROM+ mice.

Gynecomastia is a clinical manifestation that is related to estrogen action in the males, and ongoing studies have addressed the possibility of using P450arom inhibitors in the treatment of gynecomastia.7,24 Interestingly, AROM+ males display mammary gland development with several features identical to gynecomastia in men. Both the ERα and ERβ were expressed in AROM+ male mammary glands, and the signal transduction pathways via PrlR were activated, as shown by the presence of phosphorylated Stat5 proteins.26 This is in line with results showing the presence of ERs and progestin receptor (PR), as well as PrlR in the mammary gland of men with gynecomastia.55–57

The development of gynecomastia in AROM+ males was efficiently treated with a 6-week inhibitor treatment, as demonstrated by whole-mount staining of the mammary glands. Interestingly, the inhibitor treatment did not eliminate ERα expression, while ERβ protein was less stainable after inhibitor treatment. In the male fetus, T produced by the testis is known to be involved in regression of the mammary bud in the male, starting on gestation day 13 in mice.58 In the absence of this T-induced regression, the mammary gland maintains its full competence for development in male mice.59,60 The demonstration of AR in the inhibitor-treated AROM+ mammary epithelium with increased circulating T suggests an antiproliferative function for androgens also in the adult male mammary epithelium. Clinical data also suggest that androgens suppress mammary growth in men.61 It has also been shown that while E2 stimulates the proliferation of mammary epithelial cells in a primate model, its proliferative effect is significantly reduced by T.62 Clinically, androgens have been used in the past for the treatment of breast cancer with some success.17 The possibility that the AR signaling pathway is active in the male mammary gland is also supported by the results showing that gynecomastia often develops as a consequence of antiandrogen therapy, and high doses of aromatizable androgens.63

The development of pituitary lactotroph adenomas is a typical response in rodents exposed to increased level of estrogens.64,65 Interestingly, the present data suggest that the pituitary in males is more sensitive to the estrogen exposure than that in females. AROM+ males have relatively low circulating levels of estrogens that do not exceed the normal level in females, yet they develop severe lactotroph adenomas, and the adenoma development is efficiently inhibited by P450arom inhibitor. Another interesting linkage exists between the enhanced estrogen action and the enlargement of the adrenal in AROM+ mice. AROM+ mice show the estrogen-dependent hyperplastic cells in the adrenal cortex, while the mechanisms of the hyperplasia remains to be studied.

In conclusion, the present data show that P50arom inhibitor treatment reduces the E2/T ratio, and the severe phenotype in AROM+ males could be largely normalized. These observations indicate that the AROM+ mouse model is a novel tool for evaluating the effects of compounds that interfere with estrogen production or action in males in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Johanna Vesa for technical assistance with the microscopic studies, and Kati Raepalo for technical assistance with genotyping the mice.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Matti Poutanen, Department of Physiology, Institute of Biomedicine, University of Turku, Kiinamyllynkatu 10, FIN-20520 Turku, Finland. E-mail: matti.poutanen@utu.fi.

References

- Means GD, Mahendroo MS, Corbin CJ, Mathis JM, Powell FE, Mendelson CR, Simpson ER. Structural analysis of the gene encoding human aromatase cytochrome P-450, the enzyme responsible for estrogen biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:19385–19391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EA, Jr, Siiteri PK. The involvement of human placental microsomal cytochrome P-450 in aromatization. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:5373–5378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson CR, Wright EE, Evans CT, Porter JC, Simpson ER. Preparation and characterization of polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies against human aromatase cytochrome P-450 (P-450AROM), and their use in its purification. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985;243:480–491. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90525-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson IC, Canellos GP. Cancer of the breast: the past decade (second of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1980;302:78–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198001103020203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR. Aromatase activity in breast tissue. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1991;39:783–790. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(91)90026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasano H, Watanabe K, Ito K, Sato S, Yajima A. New concepts in the diagnosis and prognosis of endometrial carcinoma. Pathol Annu. 1994;29:31–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunstein GD. Aromatase and gynecomastia. Endocr Relat Cancer. 1999;6:315–324. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0060315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biro FM, Lucky AW, Huster GA, Morrison JA. Pubertal staging in boys. J Pediatr. 1995;127:100–102. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70265-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickman S, Sipila I, Ankarberg-Lindgren C, Norjavaara E, Dunkel L. A specific aromatase inhibitor and potential increase in adult height in boys with delayed puberty: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;357:1743–1748. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04895-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan JA, Newbold RR, Bullock B. Reproductive tract lesions in male mice exposed prenatally to diethylstilbestrol. Science. 1975;190:991–992. doi: 10.1126/science.242076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbold R, Bullock B, McLachlan J. Lesions of the rete testis in mice exposed prenatally to diethylstilbestrol. Cancer Res. 1985;45:5145–5150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbold RR, Bullock BC, McLachlan JA. Adenocarcinoma of the rete testis. Diethylstilbestrol-induced lesions of the mouse rete testis. Am J Pathol. 1986;125:625–628. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill W, Schumacher G, Bibbo M, Straus F, Schoenberg H. Association of diethylstilbestrol exposure in utero with cryptorchidism, testicular hypoplasia and semen abnormalities. J Urol. 1979;122:36–39. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)56240-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue RH, Pike MC, Henderson BE. Estrogen exposure during gestation and risk of testicular cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1983;71:1151–1155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pylkkanen L, Santti R, Newbold R, McLachlan JA. Regional differences in the prostate of the neonatally estrogenized mouse. Prostate. 1991;18:117–129. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990180204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie A, Lu Q, Long B. Aromatase and its inhibitors. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1999;69:205–210. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(99)00051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor JI, Jordan VC. Basic guide to the mechanisms of antiestrogen action. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:151–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santen RJ. To block estrogen’s synthesis or action: that is the question. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:3007–3012. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.7.8589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell L, Robertson KM, Jones ME, Simpson ER. Estrogen and spermatogenesis. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:289–318. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.3.0431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzdar AU. A summary of second-line randomized studies of aromatase inhibitors. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;79:109–114. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(01)00150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler J, King N, Dowsett M, Ottestad L, Lundgren S, Walton P, Kormeset PO, Lonning PE. Influence of anastrozole (Arimidex), a selective, non-steroidal aromatase inhibitor, on in vivo aromatisation and plasma oestrogen levels in postmenopausal women with breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:1286–1291. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowsett M, Jones A, Johnston SR, Jacobs S, Trunet P, Smith IE. In vivo measurement of aromatase inhibition by letrozole (CGS 20267) in postmenopausal patients with breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1:1511–1515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulun SE, Zeitoun K, Takayama K, Noble L, Michael D, Simpson E, Johns A, Putman M, Sasano H. Estrogen production in endometriosis and use of aromatase inhibitors to treat endometriosis. Endocr Relat Cancer. 1999;6:293–301. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0060293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuillan P, Merke D, Leschek EW, Cutler GB., Jr Use of aromatase inhibitors in precocious puberty. Endocr Relat Cancer. 1999;6:303–306. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0060303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Nokkala E, Yan W, Streng T, Saarinen N, Warri A, Huhtaniemi I, Santti R, Makela S, Poutanen M. Altered structure and function of reproductive organs in transgenic male mice overexpressing human aromatase. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2435–2442. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.6.8211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Warri A, Makela S, Ahonen T, Streng T, Santti R, Poutanen M. Mammary gland development in transgenic male mice expressing human P450 aromatase. Endocrinology. 2002;143:4074–4083. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haavisto AM, Pettersson K, Bergendahl M, Perheentupa A, Roser JF, Huhtaniemi I. A supersensitive immunofluorometric assay for rat luteinizing hormone. Endocrinology. 1993;132:1687–1691. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.4.8462469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huhtaniemi I, Nikula H, Rannikko S. Treatment of prostatic cancer with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist analog: acute and long term effects on endocrine functions of testis tissue. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985;61:698–704. doi: 10.1210/jcem-61-4-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toppari J, Larsen JC, Christiansen P, Giwercman A, Grandjean P, Guillette LJ, Jr, Jegou B, Jensen TK, Jouannet P, Keiding N, Leffers H, McLachlan JA, Meyer O, Muller J, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Scheike T, Sharpe R, Sumpter J, Skakkebaek NE. Male reproductive health and environmental xenoestrogens. Environ Health Perspect. 1996;104(Suppl 4):741–803. doi: 10.1289/ehp.96104s4741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adami HO, Bergstrom R, Mohner M, Zatonski W, Storm H, Ekbom A, Tretli S, Teppo L, Ziegler H, Rahu M. Testicular cancer in nine northern European countries. Int J Cancer. 1994;59:33–38. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910590108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller H. Trends in incidence of testicular cancer and prostate cancer in Denmark. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:1007–1011. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.5.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DM, Webb JA, Hargreave TB. Cryptorchidism in Scotland. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987;295:1235–1236. doi: 10.1136/bmj.295.6608.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulozzi LJ, Erickson JD, Jackson RJ. Hypospadias trends in two US surveillance systems. Pediatrics. 1997;100:831–834. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.5.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skakkebaek N, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Main K. Testicular dysgenesis syndrome: an increasingly common developmental disorder with environmental aspects. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:972–978. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.5.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan J, Newbold R, Burow M, Li S. From malformations to molecular mechanisms in the male: three decades of research on endocrine disrupters. APMIS. 2001;109:263–272. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2001.d01-119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess RA, Bunick D, Bahr J. Oestrogen, its receptors and function in the male reproductive tract: a review. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;178:29–38. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00412-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe RM. The roles of oestrogen in the male. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 1998:371–377. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(98)00089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy EM, Washburn TF, Bunch DO, Goulding EH, Gladen BC, Lubahn DB, Korach KS. Targeted disruption of the estrogen receptor gene in male mice causes alteration of spermatogenesis and infertility. Endocrinology. 1996;137:4796–4805. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.11.8895349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson KM, O’Donnell L, Jones ME, Meachem SJ, Boon WC, Fisher CR, Graves KH, McLachlan RI, Simpson ER. Impairment of spermatogenesis in mice lacking a functional aromatase (cyp 19) gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7986–7991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner K, Morley M, Atanassova N, Swanston I, Sharpe R. Effect of chronic administration of an aromatase inhibitor to adult male rats on pituitary and testicular function and fertility. J Endocrinol. 2000;164:225–238. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1640225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebling FJ, Brooks AN, Cronin AS, Ford H, Kerr JB. Estrogenic induction of spermatogenesis in the hypogonadal mouse. Endocrinology. 2000;141:2861–2869. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.8.7596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler KA, Gill K, Kirma N, Dillehay DL, Tekmal RR. Overexpression of aromatase leads to development of testicular leydig cell tumors: an in vivo model for hormone-mediated testicular cancer. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:347–353. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64736-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clegg ED, Cook JC, Chapin RE, Foster PM, Daston GP. Leydig cell hyperplasia and adenoma formation: mechanisms and relevance to humans. Reprod Toxicol. 1997;11:107–121. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(96)00203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F-P, Poutanen M, Wilbertz J, Huhtaniemi I. Normal prenatal but arrested postnatal sexual development of luteinizing hormone receptor knockout mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:172–183. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.1.0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huseby R. Demonstration of a direct carcinogenic effect of estradiol on Leydig cells of the mouse. Cancer Res. 1980;40:1006–1013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navickis R, Shimkin M, Hsueh A. Increase in testis luteinizing hormone receptor by estrogen in mice susceptible to Leydig cell tumors. Cancer Res. 1981;41:1646–1651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rulli SB, Kuorelahti A, Karaer O, Pelliniemi L, Poutanen M, Huhtaniemi I. Reproductive disturbances, pituitary lactotrope adenomas, and mammary gland tumors in transgenic female mice producing high levels of human chorionic gonadotropin. Endocrinology. 2002;143:4084–4095. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe R. The ’oestrogen hypothesis’- where do we stand now? Int J Androl. 2003;26:2–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.2003.00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan J, Newbold R, Bullock B. Reproductive tract lesions in male mice exposed prenatally to diethylstilbestrol. Science. 1975;190:991–992. doi: 10.1126/science.242076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nef S, Shipman T, Parada LF. A molecular basis for estrogen-induced cryptorchidism. Dev Biol. 2000;224:354–361. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmen JM, McLuskey A, Adham IM, Engel W, Grootegoed JA, Brinkmann AO. Hormonal control of gubernaculum development during testis descent: gubernaculum outgrowth in vitro requires both insulin-like factor and androgen. Endocrinology. 2000;141:4720–4727. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.12.7830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nef S, Parada LF. Hormones in male sexual development. Genes Dev. 2000;14:3075–3086. doi: 10.1101/gad.843800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskimies P, Virtanen H, Lindstrom M, Kaleva M, Poutanen M, Huhtaniemi I, Toppari J. A common polymorphism in the human relaxin-like factor (RLF) gene: no relationship with cryptorchidism. Pediatr Res. 2000;47:538–541. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200004000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin P, Ferlin A, Moro E, Rossi A, Bartoloni L, Rossato M, Foresta C. Novel insulin-like 3 (INSL3) gene mutation associated with human cryptorchidism. Am J Med Genet. 2000;103:348–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess HE, Shousha S. An immunohistochemical study of the long-term effects of androgen administration on female-to-male transsexual breast: a comparison with normal female breast and male breast showing gynaecomastia. J Pathol. 1993;170:37–43. doi: 10.1002/path.1711700107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pensler JM, Silverman BL, Sanghavi J, Goolsby C, Speck G, Brizio-Molteni L, Molteni A. Estrogen and progesterone receptors in gynecomastia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106:1011–1013. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200010000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertani HC, Garcia-Caballero T, Lambert A, Gerard F, Palayer C, Boutin JM, Vonderhaar BK, Waters MJ, Lobie PE, Morel G. Cellular expression of growth hormone and prolactin receptors in human breast disorders. Int J Cancer. 1998;79:202–211. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980417)79:2<202::aid-ijc17>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson GW, Karpf AB, Kratochwil K. Regulation of mammary gland development by tissue interaction. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 1999;4:9–19. doi: 10.1023/a:1018748418447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratochwill K. In vivo analysis of the hormonal basis for the sexual dimorphism in the embryonic development of the mouse mammary gland. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1971;25:141–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forest MG. Role of androgens in fetal and pubertal development. Horm Res. 1983;18:69–83. doi: 10.1159/000179780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staiman VR, Lowe FC. Tamoxifen for flutamide/finasteride-induced gynecomastia. Urology. 1997;50:929–933. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00457-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Ng S, Adesanya-Famuiya O, Anderson K, Bondy CA. Testosterone inhibits estrogen-induced mammary epithelial proliferation and suppresses estrogen receptor expression. EMBO J. 2000;14:1725–1730. doi: 10.1096/fj.99-0863com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stege R. Potential side-effects of endocrine treatment of long duration in prostate cancer. Prostate Suppl. 2000;10:38–42. doi: 10.1002/1097-0045(2000)45:10+<38::aid-pros8>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaney AP, Horwitz GA, Wang Z, Singson R, Melmed S. Early involvement of estrogen-induced pituitary tumor transforming gene and fibroblast growth factor expression in rolactinoma pathogenesis. Nat Med. 1999;5:1317–21. doi: 10.1038/15275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spady TJ, Harvell DM, Snyder MC, Pennington KL, McComb RD, Shull JD. Estrogen-induced tumorigenesis in the Copenhagen rat: disparate susceptibilities to development of prolactin-producing pituitary tumors and mammary carcinomas. Cancer Lett. 1998;124:95–103. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)00455-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]