Abstract

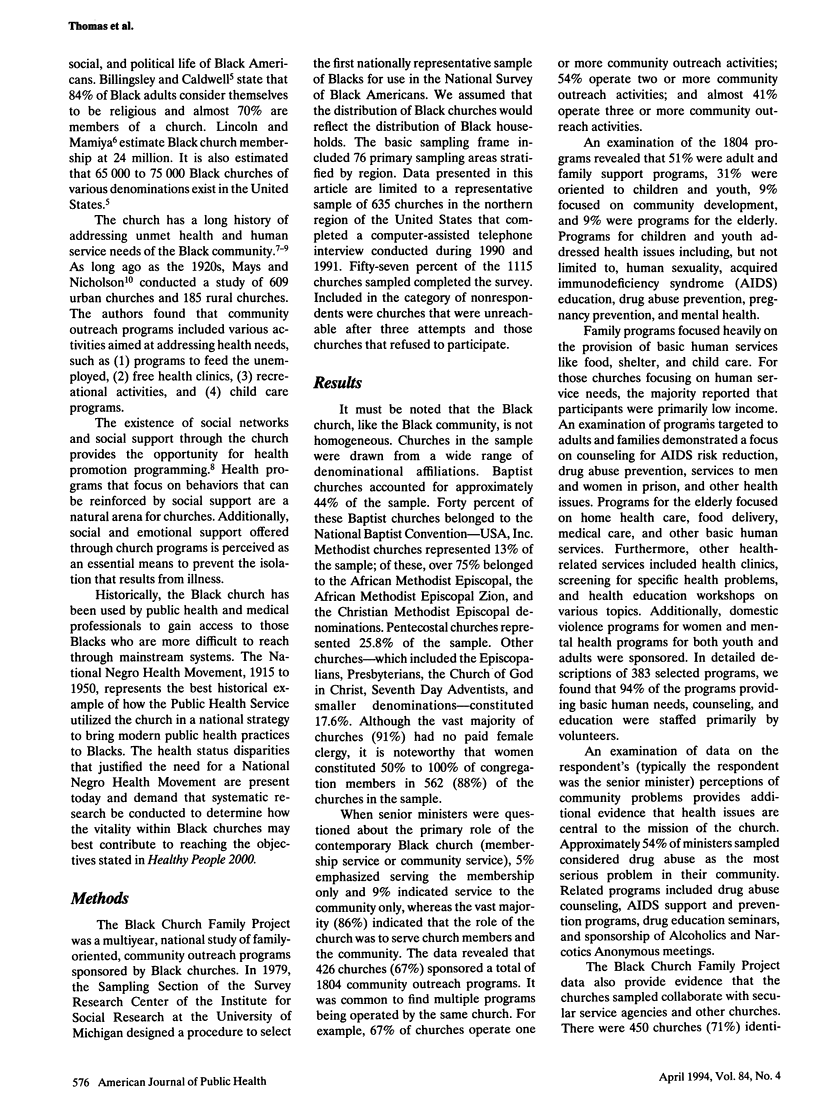

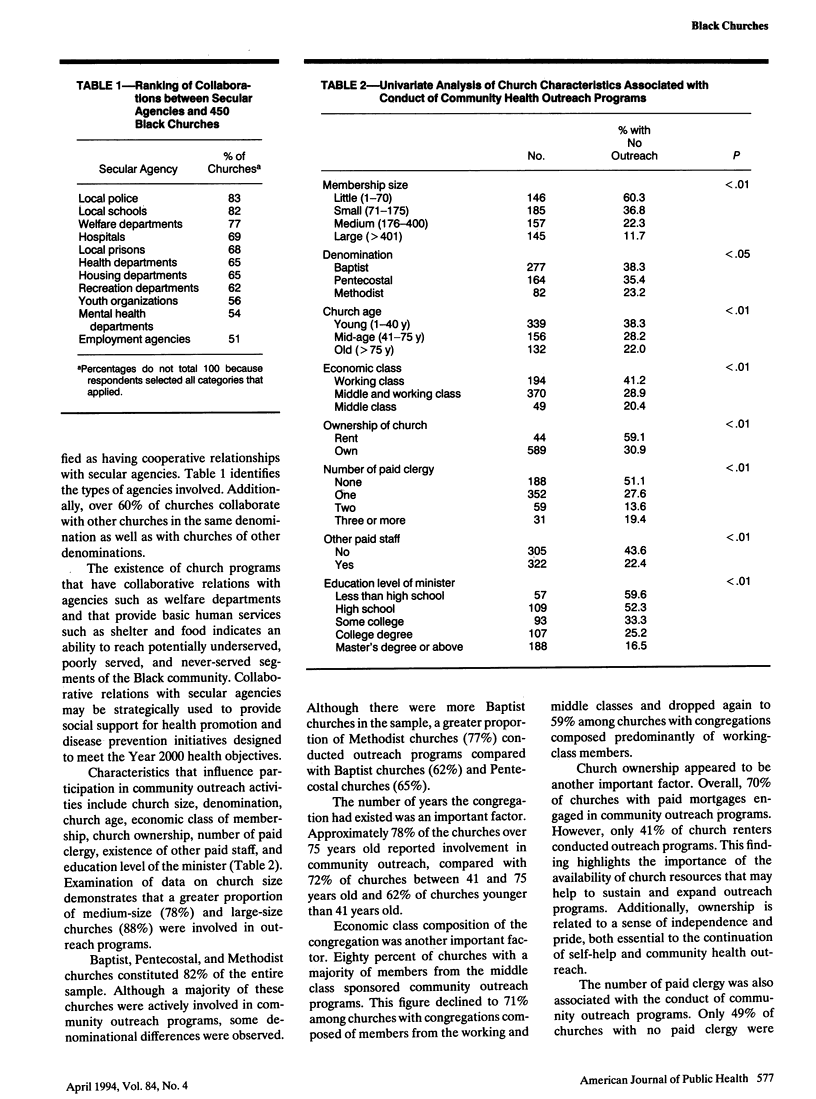

OBJECTIVES. The Black church has a long history of addressing unmet health and human service needs, yet few studies have examined characteristics of churches involved in health promotion. METHODS. Data obtained from a survey of 635 Black churches in the northern United States were examined. Univariate and multivariate statistical procedures identified eight characteristics associated with community health outreach programs: congregation size, denomination, church age, economic class of membership, ownership of church, number of paid clergy, presence of other paid staff, and education level of the minister. RESULTS. A logistic regression model identified church size and educational level of the minister as the strongest predictors of church-sponsored community health outreach. The model correctly classified 88% of churches that conduct outreach programs. Overall, the model correctly classified 76% of churches in the sample. CONCLUSIONS. Results may be used by public health professionals and policy makers to enlist Black churches as an integral component for delivery of health promotion and disease prevention services needed to achieve the Year 2000 health objectives for all Americans.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Eng E., Hatch J., Callan A. Institutionalizing social support through the church and into the community. Health Educ Q. 1985 Spring;12(1):81–92. doi: 10.1177/109019818501200107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin J. S. The role of the black church in community medicine. J Natl Med Assoc. 1984 May;76(5):477–483. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg G. D. National health care reform. An aura of inevitability is upon us. JAMA. 1991 May 15;265(19):2566–2567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBeath W. H. Health for all: a public health vision. Am J Public Health. 1991 Dec;81(12):1560–1565. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.12.1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S. B. Community health advocacy for racial and ethnic minorities in the United States: issues and challenges for health education. Health Educ Q. 1990 Spring;17(1):13–19. doi: 10.1177/109019819001700103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S. B., Quinn S. C. The burdens of race and history on Black Americans' attitudes toward needle exchange policy to prevent HIV disease. J Public Health Policy. 1993 Autumn;14(3):320–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiist W. H., Flack J. M. A church-based cholesterol education program. Public Health Rep. 1990 Jul-Aug;105(4):381–388. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]