Abstract

Pyrococcus furiosus was found to grow on chitin, adding this polysacharide to the inventory of carbohydrates utilized by this hyperthermophilic archaeon. Accordingly, two open reading frames (chiA [Pf1234] and chiB [Pf1233]) were identified in the genome of P. furiosus, which encodes chitinases with sequence similarity to proteins from the glycosyl hydrolase family 18 in less-thermophilic organisms. Both enzymes contain multiple domains that consist of at least one binding domain and one catalytic domain. ChiA (ca. 39 kDa) contains a putative signal peptide, as well as a binding domain (ChiABD), that is related to binding domains associated with several previously studied bacterial chitinases. chiB, separated by 37 nucleotides from chiA and in the same orientation, encodes a polypeptide with two different proline-threonine-rich linker regions (6 and 3 kDa) flanking a chitin-binding domain (ChiBBD [11 kDa]), followed by a catalytic domain (ChiBcat [35 kDa]). No apparent signal peptide is encoded within chiB. The two chitinases share little sequence homology to each other, except in the catalytic region, where both have the catalytic glutamic acid residue that is conserved in all family 18 bacterial chitinases. The genes encoding ChiA, without its signal peptide, and ChiB were cloned and expressed in Escherichia coli. ChiA exhibited no detectable activity toward chitooligomers smaller than chitotetraose, indicating that the enzyme is an endochitinase. Kinetic studies showed that ChiB followed Michaelis-Menten kinetics toward chitotriose, although substrate inhibition was observed for larger chitooligomers. Hydrolysis patterns on chitooligosaccharides indicated that ChiB is a chitobiosidase, processively cleaving off chitobiose from the nonreducing end of chitin or other chitooligomers. Synergistic activity was noted for the two chitinases on colloidal chitin, indicating that these two enzymes work together to recruit chitin-based substrates for P. furiosus growth. This was supported by the observed growth on chitin as the sole carbohydrate source in sulfur-free media.

Chitin, a β-1,4-linked N-acetyl-d-glucosamine (GlcNAc) homopolymer, is one of the most abundant biopolymers in the biosphere, with an estimated annual production in nature of 1010 to 1011 tons (28). Chitin, for which specific structural features are source dependent, is the main structural component of most fungal cell walls and exoskeletons of arthropods and is found in both terrestrial and marine habitats (56). This polysaccharide serves as a carbon and energy source for a wide variety of organisms, and enzymes comprising various chitinolytic systems have been isolated and studied (2, 10, 21, 23, 27, 28, 34, 38, 39, 51, 53, 61, 62, 70, 72, 73). Chitinases, separately or synergistically, hydrolyze chitin into small oligosaccharides by cleaving the β-1,4 linkages in the polymer backbone. In the more than 80 families of glycosyl hydrolases that have been defined on the basis of amino acid sequence homology (13, 31), chitinases are assigned to two families: 18 and 19. Family 18 includes chitinases from bacteria, plants, fungi, viruses, and animals and was recently further divided into three subfamilies, i.e., A, B, and C (58). Many chitinases have chitin-binding domains and catalytic domains that may be flanked or interspersed among one or more proline-threonine (PT)-rich regions (22, 26, 46, 59, 65, 69). The catalytic domains contain the catalytic residues, a glutamic acid and an aspartic acid, which have been identified through site-directed mutagenesis (71) based on information from crystal structures of two bacterial chitinases from Serratia marcescens (50, 67). These two amino acids are thought to be involved in general acid catalysis in a retaining mechanism. Chitinases have been identified in microorganisms from a wide variety of thermal environments, ranging from a psychrophilic bacterium, Arthrobacter sp., growing at 4°C (43) to moderately thermophilic bacteria (55, 60), which are active up to a temperature range of 70 to 80°C. Recently, an archaeal chitinase was identified in Thermococcus kodakaraensis KOD1, TkoChiA, with a temperature optimum of 85°C and a mass of 134 kDa (61, 62). This multidomain protein consists of two active sites with different cleavage specificities and three substrate-binding domains, which are related to two families of cellulose-binding domains (61, 62). So far, only two hyperthermophilic archaea, Thermococcus chitonophagus (32) and Thermococcus kodakaraensis KOD1 (61), have been shown to grow on chitin.

Pyrococcus furiosus, a hyperthermophile, is a heterotrophic and anaerobic archaeon, with an optimum growth temperature of 98 to 100°C (19). P. furiosus has been found to grow on a variety of α-linked carbohydrates, such as starch and maltose (7), as well as on β-linked glucan substrates, such as cellobiose (37), laminarin (29), barley β-glucan, and some soluble forms of cellulose (5, 16). Glycosyl hydrolases from P. furiosus that have been identified and characterized include an α-glucosidase (12), two α-amylases (35, 41, 42), an amylopullulanase (8, 15), a β-glucosidase (37), a β-mannosidase (3), a laminarinase (29), and an endoglucanase (4). These glycosyl hydrolases are involved in carbohydrate utilization by this organism (16). We report here that chitin is yet another growth substrate for P. furiosus, as evidenced by the growth of this microorganism on chitin, facilitated by two family 18 chitinases, the biochemical features of which were determined for their recombinant forms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture media and growth conditions.

P. furiosus (DSM3638) was grown on sea salts medium (SSM), supplemented with chitin. SSM contained the following components per liter: sea salts, 40.0 g; PIPES [piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid)], 3.1 g; yeast extract, 1.0 g; Vent Sulfothermophiles medium (VSM) trace elements solution, 1.0 ml (18); rezasurin, 0.5 mg. The VSM trace elements solution contained the following per 100 ml: nitrilotriacetic acid, 1.50 g; FeCl2 · 6H2O, 0.50 g; Na2WO4 · 2H2O, 0.30 g; MnCl2 · 4H2O, 0.40 g; NiCl26H2O, 0.20 g; ZnSO4 · 7H2O, 0.1 g; CoSO4 · 7H2O, 0.1 g; CuSO4 · 5H2O, 0.01 g; and Na2MoSO4 · 5H2O, 0.01 g. The medium was adjusted to pH 6.8 by the addition of NaOH. Chitin was prepared according to the modified method of Dworkin and Reichenbach (17): 20 g of chitin (crab shells, practical grade [Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.]) was mixed with 200 ml of 37% HCl and then stirred for 15 h at 4°C. The suspension was then added to 1.0 liter of H2O and recovered on filter paper. The residue was washed several times with 0.5 liter of H2O until the pH was close to neutral. The resulting suspension was centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 15 min and used in growth medium.

P. furiosus was grown for 15 h in 50 ml of SSM containing 5 g of both tryptone and colloidal chitin/liter at 95°C. After the initial pass, the tryptone concentration was reduced by half (2.5 g/liter), and the medium was inoculated with 1% of the culture from the original pass. After two passes of 2.5 g of tryptone (cultured for 12 to 15 h)/liter, tryptone was further reduced to 1.25 g/liter, and the culture was passed twice. This stepwise reduction of tryptone concentration was continued until it was reduced to <0.12 g/liter, and then it was completely left out of the medium. P. furiosus was grown on colloidal chitin without tryptone for an additional 10 passes before growth was monitored by cell count by using epiflourescence microscopy. A negative control was conducted without addition of chitin by using the same inoculant.

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Escherichia coli NovaBlue (Novagen, Inc., Madison, Wis.) and EpicurianColi BL21-CodonPlus(DE3)-RIL competent cells (Strategene, La Jolla, Calif.) were used as the cloning and expression hosts, respectively. Plasmid pET24d(+) (Novagen) was used as the cloning vector for the chitinase genes from P. furiosus.

Sequencing.

Open reading frame (ORFs) containing the putative chitinase genes were identified from P. furiosus genome sequencing data (http://www.genome.utah.edu). To verify a possible stop codon at the C terminus of ChiA, a set of primers (5′-ATACAACTTGGATGGCCTTGAC-3′ and 5′-GGATCCTCATAAGGAGCATTC-3′) was designed to flank this codon in the gene sequence. The PCR amplification product from P. furiosus genomic DNA was purified by using a QIAquick PCR purification kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.). Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technology, Inc. (Coralville, Iowa), and the DNA product was sequenced at the Molecular Genetics Instrumentation Facility (MGIF), Department of Genetics, University of Georgia, Athens. Sequence analysis was performed by using Wisconsin Genetics Computer sequence analysis software package version 9.1 (Genetics Computer Group, University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center, Madison), and sequence searches were done by using BLAST from National Center for Biotechnology Information world-wide web server. The N termini of proteins were determined by blotting them onto ProBlott membranes according to the instructions of the manufacturer (PE Applied Biosystems, Norwalk, Conn.) and then sequenced by MGIF.

Total RNA isolation and RT-PCR analysis.

A 300-ml culture of P. furiosus was grown to early to mid-exponential growth phase on chitin. Total RNA was extracted by use of an RNAqueous kit (Ambion, Austin, Tex.), modified for P. furiosus. Cells were harvested by first removing residual chitin with filter paper, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 22 min. The cells were then washed in 2 ml of ice-cold growth medium and pulse spun at 16,000 × g. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 85 μl of ice-cold Tris-EDTA solution, with the addition of 625 μl of RNA lysis buffer (6.2 M guanidine thiocyanate, 0.04 M sodium citrate, 0.8% sarcosyl, 0.75% β-mercaptoethanol). After the addition of 62.5 μl of 2 M sodium acetate (pH 4.5), the mixture was extracted with an equal volume of phenol-chloroform (5:1). The top layer containing RNA was further processed by ethanol precipitation and then resuspended in 10 mM Tris (pH 8.5). Total RNA was then extracted according to the manufacturer's protocol (Ambion). RNA concentration and integrity were determined by measuring the absorbances at 260 and 280 nm, as well as by 0.8% agarose gel analysis. Reverse transcription (RT) and PCR amplification was carried out by using the Access RT-PCR System (Promega), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Two sets of primers were used for amplification of chitinase transcripts: ChiA gene (5′-GGAGGAATTCATATGGGTGAGGCAGAGCCAACT-3′ and 5′-GGACCGCTCGAGTCAGCTGGAACTGCTGCAGCAGTT-3′ [reverse primer]) and ChiB gene (5′-TAGCCGGAAGCCATGGTCCCAGTCTCAGGATCTCTA-3′ and 5′-GGACCGCCGCTCGAGTTAGTCCCTCCGGTTGGT-3′ [reverse primer]). An identical set of RT-PCRs was conducted with the total RNA extracted from P. furiosus grown on tryptone alone, with the same primers.

Cloning and expression screening.

P. furiosus genomic DNA was kindly provided by F. Jenny, Department of Biochemistry, University of Georgia. Primers were designed to amplify chiA without its signal peptide by PCR: 5′-CGGCTAGAACCATGGCCCAACAAACAGTGCAGCTA-3′ (forward primer) and5′-ATTTGGACCCTCGAGTTATCAGCTGGAACTGCTGCAG-3′ (reverseprimer). Two sets of primers were designed to amplify the full-length gene sequences of ChiB and its catalytic domain (ChiBcat), respectively: 5′-GGTATCATGAAATATCTCGACTTCAT-3′ (forward primers) and 5′-GGTCCTCGAGTTATGTTGGAACACTAGCTT-3′ (reverse primer) for chiB and 5′-TATACATATGAATGCAAATCCAATA-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-AGCTGCCTCGAGGAATTCTTATGTTGGAACACTAGC-3′ (reverse primer) for chiBcat. For chiA and chiBcat, NcoI and XhoI restriction sites were added to the 5′ and 3′ ends of these PCR products, respectively. The PCR products were then double digested with the two restriction enzymes, NcoI and XhoI (Promega), and ligated to the similarly digested pET24d(+). To clone the full-length chiB, a BspHI site was used at the 5′ end of the forward primer. The PCR product was digested with BspHI and XhoI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) and ligated to NcoI-XhoI-digested pET24d(+). The ligation products were then transformed into E. coli. To screen for chitinase activity in the ChiA and ChiB clones, colonies were transferred to individual wells of microtiter plates containing 100 μl of Luria-Bertani (LB) medium with 50 μg of kanamycin/ml and grown at 37°C. Then, 50 μl from each well was transferred to a separate microtiter plate containing 50 μl of LB medium plus kanamycin with 2 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). After 2 h of induction at 37°C, the samples were heat treated at 98°C for 15 min. Then, 50 μl of 1 mM p-nitrophenyl di-N-acetyl-β-chitobioside (Seikagaku Corp., Tokyo, Japan) was added to the wells, and the plates were incubated at 98°C for 5 to 15 min. The positive colonies were identified by the release of p-nitrophenol (pNp) as indicated by the color change. The identically treated E. coli cells, containing just the pET24d(+) plasmid, were used as negative controls.

Production and purification of recombinant proteins.

Positive colonies (verified by plasmid sequencing) were grown overnight in 100 ml of LB medium containing 50 μg of kanamycin/ml at 37°C. This culture was then used to inoculate another 2-liter culture in LB medium plus kanamycin. After cultures were grown at 37°C to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6, they were induced by a 1 mM final concentration of IPTG and then grown at 30°C for another 14 h. After centrifugation (10,000 × g, 20 min), the cell pellets were resuspended in 20 ml of 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (SPB; pH 6.0). The cells were then lysed by passage through a French press (SLM Instruments, Urbana, Ill.) twice, after which the cell extract was centrifuged at 30,000 × g for 30 min. The pellet was saved for subsequent recovery of enzyme activity from inclusion bodies, while the supernatant was heated at 80°C for 30 min and then centrifuged again at 30,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant, which contained recombinant protein, was collected. The heat-treated supernatants were loaded onto a DEAE-Sepharose CL-6B (5×40) column (Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.), which had been previously equilibrated with 50 mM SPB (pH 6.0). The columns were developed with a 4.0-liter gradient of 0.0 to 1.0 M sodium chloride in the starting buffer. Fractions were assayed for chitinase activities at 95°C by monitoring the release of the p-nitrophenyl group from p-nitrophenyl di-N-acetyl-β-chitobioside. Fractions containing chitinase activity were pooled, equilibrated to 50 mM SPB (pH 7.0) containing 150 mM NaCl, and loaded onto a Sephacryl S200 (Pharmacia).

Chitinase activity and protein assays.

Unless mentioned otherwise, enzyme assays were done in triplicate at 95°C in 1-ml reaction mixtures containing 50 mM SPB (pH 6.0) and 1.0% (wt/vol) slurries of insoluble substrates, chitin (Sigma), and colloidal chitin. Colloidal chitin was prepared by standard procedures (45a). The slurries were mixed mechanically at 250 rpm. The enzymatic activity was determined by measuring the release of reducing ends by the Somogyi-Nelson method (48) with GlcNAc as the standard. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to release 1 μmol of GlcNAc reducing end per min. Nonenzymatic hydrolysis of substrates at elevated temperatures was corrected for with the appropriate blanks. The protein concentration was determined by a dye-binding method (6), with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Enzyme kinetics and substrate specificity.

Enzyme kinetics were determined by using pNp substrates at 95°C according to procedures previously reported for other hyperthermophilic glycosidases (4, 12). pNp(GlcNAc)n (n = 1 to 4) substrates (Seikagaku) were dissolved in 50 mM SPB (pH 6.0). The rates were determined at 7 to 10 different substrate concentrations, ranging from ca. 0.15 times the estimated Km to ultimately as much as 7 times the Km, when possible. Values of Km and kcat were determined from the initial rate data by nonlinear regression analysis (74). Kinetic parameters for a series of chitooligosaccharides, i.e., (GlcNAc)n (n = 2 to 6) (Seikagaku), were determined by using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; model 2690; Waters, Milford, Mass.). Chitooligosaccharide solutions, with concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 8.0 mM, were preheated for 15 s at 95°C, after which the enzyme was added. Upon incubation at 95°C for various time intervals, the reactions were stopped by trichloroacetic acid precipitation at a 5% final trichloroacetic acid concentration. The reaction mixtures were kept on ice for 1 h and then spun down; the supernatant was then collected and loaded onto an Aminex HP-42A (3.2 by 150 mm) HPLC column (Bio-Rad, Rockville Center, N.Y.) with a guard column (Bio-Rad). The column temperature was controlled at 60°C. Substrates and reaction products were identified by using a refractive index detector (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) relative to chitooligosaccharides standards. The retention times for the chitooligosaccharides standards on the columns used here were as follows: GlcNAc, 55 min; (GlcNAc)2, 49 min; (GlcNAc)3, 43 min; (GlcNAc)4, 41 min; (GlcNAc)5, 36 min; and (GlcNAc)6, 33 min. Substrate and product concentrations were calculated from calibration curves developed with known standards. Reaction conditions were chosen so that <10% of the substrate was hydrolyzed, and the enzyme activity was calculated based on the initial rate of substrate disappearance. The specific activity of the enzyme on chitooligosaccharides was defined as the amount of substrate disappearing per minute per unit milligram of enzyme.

Temperature and pH optima.

Temperature optima of the enzymes were measured by release of pNp from the pNp-chitobioside over a temperature range of 40 to 100°C, based on a set of standards of various concentrations of pNp exposed to the same assay conditions. All activity determinations were normalized to the highest activity recorded. The pH dependence of the enzyme activity was investigated by the Somogyi-Nelson method (48) with 1.0% colloidal chitin: 50 mM sodium acetate buffer was used between pH 3.8 and 5.2, 50 mM SPB was used between pH 5.8 and 8.0, and 50 mM sodium carbonate was used for a pH of >8.

Calorimetry.

Differential scanning calorimetry was carried out on a Nano-Cal differential scanning calorimeter (Calorimetry Sciences Corp., Provo, Utah), operating over a temperature range of 25 to 125°C. The sample cell was pressurized to 3.0 atm to prevent boiling at temperatures of >100°C. Purified enzymes were dialyzed extensively against 10 mM SPB (pH 6.0). The equilibrated enzymes were scanned at 1.0°C/min by using concentrations of 0.3 mg/ml. All enzyme scans were corrected by using a buffer-buffer baseline. The partial specific volume was determined from the amino acid composition (45). The excess molar heat capacity was calculated after baseline subtraction (20), i.e., the baseline was obtained from the linear temperature dependence of the native state heat capacity.

RESULTS

Sequence analysis and protein domains.

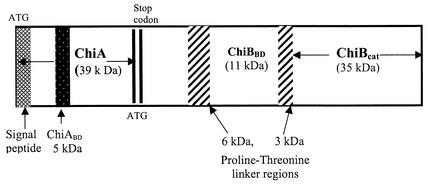

From the P. furiosus genome sequence, two ORFs were identified (Fig. 1) whose translations shared significant homology with glycosyl hydrolase family 18 chitinases. Both ORFs were located on the negative strand of genomic DNA and in the same orientation. The first ORF (Pf1234) encodes a putative 345-amino-acid protein, ChiA, with a predicted molecular mass of 39.7 kDa. Separated by 37 nucleotides, the second ORF (Pf1233) encodes a 717-amino-acid protein, ChiB, with a predicted molecular mass of 84.3 kDa. A possible promoter region, containing a consensus box A sequence (TTTATA), appears 60 bp upstream of the apparent start codon of chiA; this is similar to the promoter region identified for a β-glucosidase gene (68) and an amylase gene (35), both from P. furiosus. However, a separate promoter region was not apparent for the chiB gene. The stop codon of chiA in the P. furiosus genome sequence was independently confirmed by sequencing a PCR product flanking this region. Putative ribosome-binding sites, GGGAGG and GAGG, were identified 13 and 6 nucleotides upstream of the chiA and chiB start codons, respectively. A similar pattern was observed for two ORFs corresponding to chitinase genes from the Arthrobacter sp. strain TAD20, although the genes are separated by ca. 250 bp and a transcription terminator, such that the two genes were independently regulated (43).

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of P. furiosus chitinases, indicating the signal peptide, binding domains, catalytic domains, and PT-rich linker regions.

Similar to other family 18 chitinases, both ChiA and ChiB have multiple domains, consisting of at least one binding domain and a catalytic domain (Fig. 1). The N terminus of ChiA has a putative signal peptide (∼35 amino acid residues), presumably involved in a secretory mechanism (30, 33, 49). ChiB lacks a signal peptide and has two PT linker regions, 6 and 3 kDa each, flanking a carbohydrate-binding domain (CBD). Such PT-rich regions are mostly found associated with cellulases and xylanases (24, 25, 63), although a chitinase from Janthinobacterium lividum also has two PT-rich regions separating two binding domains (26). These PT-rich linker regions, which are sensitive to protease activity, have been found to determine the relative orientation of the catalytic and binding domains, thereby optimizing the binding and catalytic efficiency of the enzyme on insoluble substrates (57).

Comparison of P. furiosus ChiA and ChiB to other chitinases.

The P. furiosus chitinases show the highest amino acid sequence homology to the chitinase from T. kodakaraensis (TkoChiA) (61). ChiA from P. furiosus shares ca. 66% sequence identity to TkoChiA for amino acid residues 1 to 346, whereas ChiB has close to 70% sequence identity to TkoChiA from residue 522 to the end. The total molecular mass of the translated amino acid sequence for the two P. furiosus chitinases (124 kDa) is close to that reported for TkoChiA (134 kDa), although TkoChiA is encoded in a single ORF.

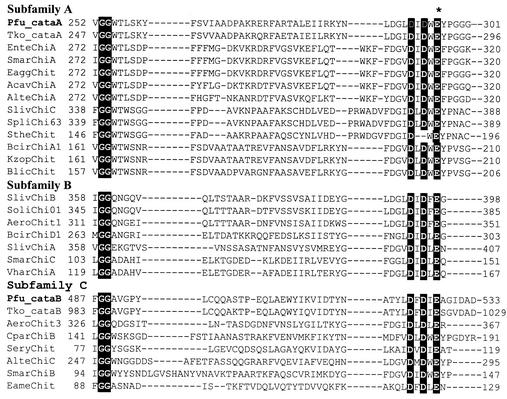

Recently, family 18 chitinases were further divided into three subfamilies—A, B, and C—based on amino acid sequences of their β-strands. A phylogenetic tree, based on the alignment of 29 bacterial chitinases, indicated early divergence of three subfamilies of bacterial chitinases (58). A similar alignment, made by using neighbor-joining methods (54), based on the same 29 bacterial chitinases plus the five newly discovered bacterial and archaeal chitinases indicates that the two P. furiosus chitinases likely diverged early in the evolution of family 18 chitinases. In fact, chiA and chiB share little sequence similarity to each other except in the regions surrounding the active-site residues.

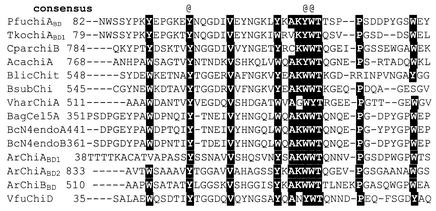

ChiA, a subfamily A chitinase, has significant homology to several mesophilic chitinases, with strongest similarity occurring in two separate sequence regions: the catalytic and binding domains. The catalytic domain, especially between amino acids 244 and 300, shares remarkably strong sequence homology (ca. 80% identity) with several chitinases from gram-negative, low G+C content bacteria, and even higher (>90%) sequence homology to catalytic region A of TkoChiA (Fig. 2). Glu295 appears to be the catalytic residue and is conserved in all family 18 chitinases; the corresponding residue in a Bacillus circulans chitinase has been identified as the essential amino acid for chitinase activity by site-directed mutagenesis (71). The region between residues 82 and 130 shares at least 30% identity with chitin-binding domains identified in various chitinases, such as ChiB from Clostridium paraputrificum (46), ChiA from Vibrio harveyii (59), and ChiA from Serratia marcescens (70). A similar binding domain was also identified in TkoChiA from amino acids 79 to 124 as CBD1, with close to 85% sequence identity to PfuChiABD (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of P. furiosus catalytic domains with other bacterial chitinases from family 18. Three subfamilies are classified based on amino acid sequence (58); the asterisk denotes a catalytic residue of family 18 chitinases. Pfu_cataA and Pfu_cataB, catalytic domains of chitinase A (PF1234) and chitinase B (PF1233) from Pyrococcus furiosus; Tko_cataA and Tko_cataB, catalytic domains of chiA from Thermococcus kodakaraensis KOD1 (AB02740); AcavChiA, Aeromonas caviae chitinase A (U09139); AeroChitl, AeroChit2, AeroChit3, and Aeo ChiII, Aeromonas sp. chitinase 1 (ORF1, D63139), chitinase 2 (ORF2, D63129), chitinase 3 (ORF3, D63129), and chitinase 11 (D31818); AlteChiA and AlteChiC, Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 chitinase A (D13762) and chitinase C (AB004557); BeirChiAl and BcirChiDl, Bacillus circulans WL-12 chitinase A1 (M57601) and chitinase D1 (D10594); BlicChit, Bacillus lichenformis chitinase A (U71214); CparChiB, Clostridium paraputrificum chitinase B (AB001874); EnteChiA, Enterobacter sp. strain G-1 chitinase A (U35121); EameChit, Ewingella americana chitinase (X90562); EaggChit, Enterobacter agglomerans chitinase (U59304); KzopChit, Kurthia zopfii chitinase (D63702); SeryChit, Streptomyces erythraeus chitinase (P14529); SlivChiA, SllvChiB, and SfivChiC, Streptomyces lividans chitinase A (D13775), chitinase B (D84193), and chitinase C (D12647); SmarChiA, SmarChiB, and SmarChiC, Serratia marcescens 2170 chitinase A (AB015996), chitinase B (AB015997), and chitinase C (AAC09387); SoliChi01, Streptomyces olivaceoviridis exochitinase (X71080); SpliChi63, Streptomyces plicatus chitinase 63 (M82804); StheChit, Streptomyces thermoviolaceus OPC-520 chitinase (DI4536); VharChiA, Vibrio harveyi chitinase A (U81496).

FIG. 3.

Comparison of P. furiosus ChiABD with other chitin- and cellulose-binding domains in CBM family 5. Absolute conserved aromatic residues responsible for the interaction of binding domain and sugar molecules are indicated by the “@” symbol. Pfu ChiABD, Pyrococcus furiosus chitinase A, chitin-binding domain; Tko ChiABD1, Thermococcus kodakaraensis chitinase A, binding domain 1; CparChiB, Clostridium paraputrificum chitinase B (AB001874); AcaChiA, Aeromonas caviae chitinase A (U09139); BlicChit, Bacillus lichenformis chitinase A (U71214); Vfu ChiD, Vibrio furnissii periplasmic chitodextrinase (U41418); BsubChi, Bacillus subtilus chitinase (AF069131); VharChiA, Vibrio harveyi chitinase A (U81496); BagCel5A, Bacillus agaradhaerens alkaline cellulase Cel5A (AF067428); BcN4endoA and -endoB, Bacillus sp. strain N-4 endoglucanase A and endoglucanase B (M14729); ArChiABD1 and ArChiABD2, Arthrobacter chitinase A binding domains 1 and 2 (AJ250585); ArChiBBD, Arthrobacter chitinase B chitin-binding domain (AJ250586).

ChiB belongs to subfamily C and has lower sequence similarity than ChiA compared to previously studied mesophilic chitinases. Within subfamily C, ChiB most closely resembles a chitinase from an Aeromonas sp. (ca. 30% similarity) (66). Beginning with amino acid residue 480, the catalytic region of ChiB has ca. 40% sequence similarity to that of ChiA and includes the conserved catalytic residue at Glu527. However, it has almost 80% sequence identity to catalytic region B, starting from residue 977 of TkoChiA (Fig. 2). Multiple subfamilies of chitinases are also found in other bacteria, such as B. circulans WL-12 (72) and S. marcescens (70). The binding domain of ChiB, ChiBBD, is ca. 100 amino acid residues long and shares sequence similarity to family 2 CBDs, as well as to chitin-binding domains from two Streptomyces species (22, 52, 64). Two CBDs in TkoChiA, CBD2 and CBD3, are also family 2 CBDs, each with ca. 65% sequence identity to ChiBBD. ChiBBD has all four conserved tryptophan residues thought to be responsible for the binding of the protein to polysaccharides (14, 75).

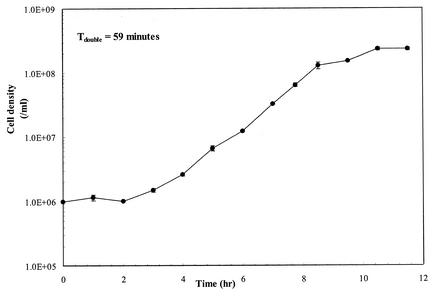

P. furiosus growth on chitin and RT-PCR.

P. furiosus was found to grow on colloidal chitin added to SSM that lacked tryptone, reaching cell densities of 2 × 108, with a doubling time of 59 min (Fig. 4). Since there was 1 g of yeast extract in the medium/liter, a negative control was conducted in the same medium without chitin. Cell densities were no higher than 106 cells/ml after chitin was completely removed from the medium, a result commonly observed for P. furiosus growth on peptide-based media lacking carbohydrates in the absence of elemental sulfur (1). RT-PCR showed that both chiA and chiB were separately transcribed for growth on chitin, as well as on tryptone-containing medium lacking chitin (data not shown). Other work has shown that the chitinase genes were transcribed when P. furiosus was grown on peptide-based media, albeit at low levels (K. R. Shockley and R. M. Kelly, unpublished data).

FIG. 4.

P. furiosus growth curve on 5 g of colloidal chitin/liter in SSM. No growth was observed in this medium in the absence of chitin.

Expression of chitinase genes and biochemical and biophysical properties of ChiA and ChiBcat.

Expression in E. coli of the entire region encoding both ChiA and ChiB in P. furiosus was unsuccessful, in contrast to the findings for TkoChiA (61). This apparently was related to the presence of a stop codon between the ChiA and ChiB coding regions in P. furiosus. Expression of ChiA in E. coli led to significant inclusion body formation when induced at 37°C with 1 mM IPTG, but mostly soluble protein was produced when E. coli was induced at 25°C. The full-length version of ChiB was proteolytically processed to a significant extent when expressed in E. coli, such that only the catalytic domain, ChiBcat, lacking the CBD and PT-rich linker regions could be produced successfully. Recombinant ChiA and ChiBcat proteins were purified to homogeneity, and their apparent molecular masses, judging from their migration on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, were in agreement with the sizes calculated from their amino acid sequences (data not shown). The pH optima of both enzymes were ca. 6.0, whereas ChiA and ChiBcat had broad temperature optima between 90 and 95°C. ChiA melted at 101°C, whereas ChiBcat was found to be extremely thermostable, with a melting temperature of 114°C (data not shown).

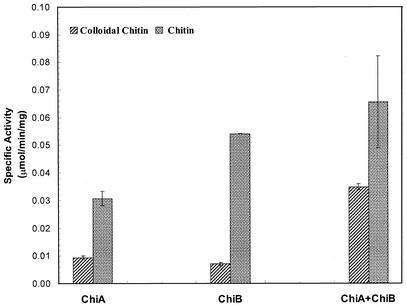

ChiA and ChiBcat exhibited activity on both purified crab shell chitin and colloidal chitin. Their specific activities were ca. 0.035 U/mg on colloidal chitin at 95°C and pH 6.0, a value comparable to TkoChiA activity (0.018 U/mg) on the same substrate at its optimal temperature of 80°C (61). Both enzymes had higher specific activity on colloidal chitin than on untreated chitin, which was probably due to better enzyme access to the amorphous structure of the colloidal form of the substrate. ChiA was twice as active on colloidal chitin than on untreated chitin, whereas ChiBcat, possibly because of the absence of its binding domain, had relatively low activity on the same substrates. When the two enzymes were added together, however, the specific activity increased fivefold on colloidal chitin but was only slightly higher on untreated chitin (Fig. 5), indicating that the two enzymes acted synergistically on the amorphous substrate.

FIG. 5.

Synergism of P. furiosus ChiA and ChiBcat on chitin at 95°C and pH 6.0. The specific activity is defined as the amount of GlcNAc reducing ends released per milligram of enzyme per minute.

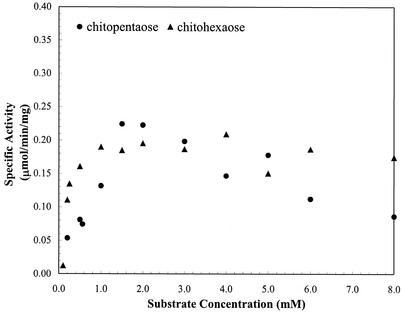

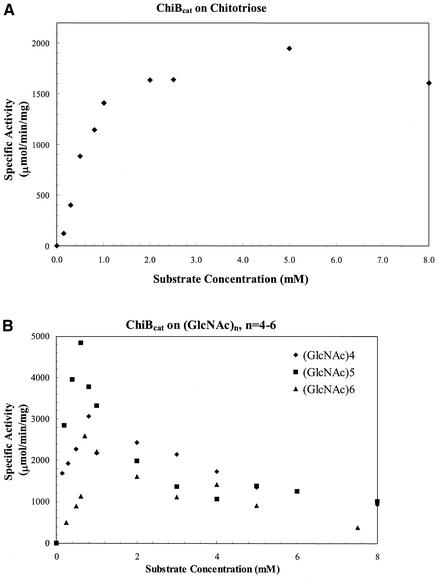

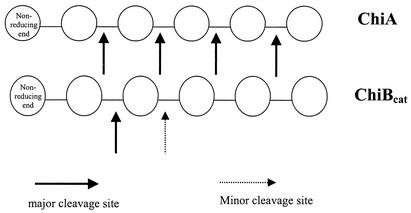

ChiA showed no activity on pNp-N-acetylglucosamine and chitooligosaccharides, with a degree of polymerization (DP) of ≤4, but was active toward chitopentaose and chitohexaose. HPLC analysis showed that the enzyme hydrolyzed chitohexaose into chitotetraose, chitotriose, and chitobiose in equal amounts (data not shown), indicating the enzyme cleaved internal β-1,4 glycosidic linkages in chitooligosaccharides randomly. ChiA exhibited Michaelis-Menten kinetics on chitopentaose and chitohexaose (Fig. 6). ChiBcat showed no detectable activity on pNp-N-acetylglucosamine and chitobiose, even after prolonged incubation times. Product analysis revealed that ChiBcat hydrolyzed chitooligosaccharides (DP = 3 to 6), yielding predominantly chitobiose. (GlcNAc)6 was processively degraded to mostly (GlcNAc)4 and (GlcNAc)2, with limited formation of (GlcNAc)3. Kinetic parameters for ChiBcat on pNp-chitooligosaccharides and chitooligosaccharides are summarized in Table 1. For the pNp-linked substrates studied, the highest kcat/Km was observed for pNp-chitotetraose, and the highest catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) was noted on (GlcNAc)4 and (GlcNAc)5 for the series of chitooligosaccharides. Initial rates of chitooligosaccharide hydrolysis showed that the enzyme exhibited Michaelis-Menten kinetics with a DP of ≥3, although significant substrate inhibition was noted on oligosaccharides with a DP of 4 to 6 at concentrations of ≥0.8 mM (Fig. 7). The hydrolysis patterns of ChiBcat, as well as of ChiA, are summarized in Fig. 8. Based on substrate specificity analysis, ChiA was determined to be an endochitinase, whereas ChiBcat was found to be a chitobiosidase.

FIG. 6.

P. furiosus ChiA kinetics on chitooligomers (DP = 5 or 6). No activity was observed for a DP of <5. The specific activity of the enzyme on chitooligosaccharides was defined as the amount of substrate disappearing per minute per unit milligram of enzyme.

TABLE 1.

Kinetic parameters for chitooligosaccharide hydrolysis by P. furiosus ChiBcata

| Substrate | Km (mM) | KI (mM) | Vmax (μmol of pNp/min/mg) | kcat/Km (mM−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pNp(GlcNAc) | ND | — | ND | ND |

| pNp(GlcNAc)2 | 3.8 | — | 141 | 21 |

| pNp(GlcNAc)3 | 0.47 | — | 58 | 70 |

| pNp(GlcNAc)4 | 0.091 | — | 23 | 150 |

| (GlcNAc)2 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| (GlcNAc)3 | 0.69 | — | 2,250 | 1,850 |

| (GlcNAc)4 | 0.13 | 5.89 | 3,070 | 13,380 |

| (GlcNAc)5 | 0.30 | 2.56 | 7,140 | 13,490 |

| (GlcNAc)6 | 0.24 | 2.15 | 2,060 | 8,580 |

Apparent Km and Vmax values for substrates were calculated from a Lineweaver-Burk plot (1/s versus 1/v, where s is the substrate concentration and v is the reaction velocity). For cases in which substrate inhibition was noted on (GlcNAc)n (n = 4 to 6), KI values (inhibition constants) were calculated from plots ([s] versus 1/v) at high substrate concentrations. —, Not measured; ND, not detected.

FIG. 7.

Effect of chitooligosaccharide (DP = 3 to 6) concentration on ChiBcat activity. A reaction mixture containing 0.002 μg of purified ChiBcat and substrates was incubated at 95°C. The enzyme activity was measured based on the rate of disappearance of substrate. The specific activity of the enzyme on chitooligosaccharides was defined as amount of substrate disappearing per minute per unit milligram of enzyme.

FIG. 8.

Hydrolysis pattern of ChiA and ChiBcat on chitooligosaccharides.

DISCUSSION

Based on the results reported here, chitin should be added to the list of glucan-based carbohydrates supporting the growth of P. furiosus. The two chitinases, examined here, ChiA and ChiB, are unique among the hyperthermophiles for which genome sequences have been reported, including the heterotrophs Thermotoga maritima (47) and Archaeoglobus fulgidus (40) and even members of the same genus, e.g., Pyrococcus horikoshii (36) and Pyrococcus abyssi (direct submission to National Center for Biotechnology Information). The P. furiosus chitinases are related to those reported for T. kodakaraensis (61) and chitinases that are presumably involved in T. chitinophagus growth on chitin (32). This supports the notion that even among species closely related by 16S rRNA phylogeny, there can be significant enzymatic diversity, presumably reflecting adaptation to nutritional environment by horizontal gene transfer (44).

Although the two chitinase genes are separated by only a short noncoding region in the P. furiosus genome, it is not clear whether these are coregulated and how they function in vivo to recruit chitin as carbon and energy source. ChiA has an associated signal peptide, but no such secretory mechanism is apparent for ChiB. It is likely that ChiA hydrolyzes chitin to transportable oligosaccharides that are then degraded further intracellularly by ChiB and perhaps by other chitinolytic enzymes yet to be determined. Efforts to resolve the complete chitinolytic pathway in P. furiosus are under way.

Like their mesophilic counterparts, both P. furiosus chitinases possess binding domains. Currently, there are 30 families of carbohydrate-binding modules (CBMs) based on amino acid sequence homology (http://afmb.cnrs-mrs.fr/CAZY/). These binding modules anchor the proteins to the substrate via the hydrophobic interactions between aromatic residues and sugar molecules moieties, allowing catalytic domains to efficiently hydrolyze the substrates. ChiABD belongs to family 5 CBMs, which are typically ca. 50 to 60 amino acids long and have been identified in various cellulases and chitinases. From the structural information for a family 5 CBM from a cellulase, the three aromatic amino acid residues responsible for interactions between the substrates and protein are absolutely conserved in ChiABD (Fig. 3) (9). ChiBBD, ca. 100 amino acids long, is a family 2 CBM, which is homologous to other family 2 domains found in cellulases, xylanses, and chitinases. Interestingly, there are three chitin-binding domains associated with TkoChiA. Two of them, CBD2 and CBD3, are family 2 CBMs, while CBD1 belongs to the family 5 CBM (61). The functional significance of the number and orientation of these CBMs in hyperthermophilic chitinases remains to be seen, but presumably the shuffling of different catalytic and binding domains generates diverse enzymes with suitable properties (11).

ChiA from S. marcescens, a subfamily A of family 18 chitinase, shares ca. 30% sequence homology to catalytic region of P. furiosus ChiA. The S. marcescens enzyme is an endochitinase, with an active site appearing as a groove-like structure, such that substrate-binding takes place in this groove with a minimum of four residue binding sites. (50). ChiB of S. marcescens is a subfamily C of family 18 chitinases and is somewhat unique because it processively hydrolyzes chitotriose from chitooligosaccharides. Its active site resembles a tunnel-like structure, and steric interaction prevents the binding of substrates extending longer than three N-acetylglucosamine units to the active site (67). In contrast, ChiBcat is a chitobiosidase, releasing chitobiose from chitooligosaccharides. Furthermore, the enzyme has similar substrate specificities (kcat/Km) toward both chitopentaose and chitohexaose, indicating that there is no steric inhibition between the substrates longer than three N-acetyl-β-glucosamine units to the catalytic domain. Detailed kinetic data for less-thermophilic chitinases is not widely available to compare the kinetic data for ChiBcat. However, such information is available for an endochitinase from the marine bacterium Vibrio furnissii (39). Although this chitinase is not closely related to ChiBcat, the specific activity and turnover numbers (kcat) of ChiBcat are 2 orders of magnitude higher than for the mesophilic organism. Both enzymes showed similar substrate specificity (kcat/Km) on (GlcNAc)5 and (GlcNAc)6. However, ChiBcat exhibited an order of magnitude higher specific activity on (GlcNAc)4 than the V. furnissii endochitinase (Table 1), indicating that a tetrasaccharide optimally binds to the active site of ChiBcat. It is also worth noting that, although ChiBcat exhibited the greatest level of inhibition on chitohexaose, this may due to the fact that the substrate is broken down to chitobiose and chitotetraose, which contribute to the inhibition of the enzyme.

It was speculated that the presence of the T. kodakaraensis chitinase is due to lateral gene transfer between the bacteria and the archaeon (61). The existence of the P. furiosus chitinases indicates that lateral gene transfer, if this is the cause, was more widely spread and occurred at a deeper phylogenetic level. The details of an archaeal chitinolytic system are not well understood. Other important chitinolytic enzymes, such as β-N-acetylglucosaminidase and chitin deactylase, have not been identified or characterized, although β-N-acetylglucosaminidase activity has been found in a cytoplasmic fraction of P. furiosus grown on chitin (J. Gao and R. M. Kelly, unpublished data). Efforts to identify and characterize other chitinolytic enzymes in P. furiosus are under way.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Science Foundation Biotechnology Program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, M. W., J. F. Holden, A. L. Menon, G. J. Schut, A. M. Grunden, C. Hou, A. M. Hutchins, F. E. Jenney, Jr., C. Kim, K. Ma, G. Pan, R. Roy, R. Sapra, S. V. Story, and M. F. Verhagen. 2001. Key role for sulfur in peptide metabolism and in regulation of three hydrogenases in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Bacteriol. 183:716-724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassler, B. L., P. J. Gibbons, C. Yu, and S. Roseman. 1991. Chitin utilization by marine bacteria:Chemotaxis to chitin oligosaccharides by Vibrio furnissii. J. Biol. Chem. 266:24268-24275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer, M. W., E. J. Bylina, R. V. Swanson, and R. M. Kelly. 1996. Comparison of a β-glucosidase and a β-mannosidase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Biol. Chem. 271:23749-23755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer, M. W., L. E. Driskill, W. Callen, M. A. Snead, E. J. Mathur, and R. M. Kelly. 1999. An endoglucanase, EglA, from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus hydrolyzes β-1,4 bonds in mixed-linkage (1→3),(1→4)-β-d-glucans and cellulose. J. Bacteriol. 181:284-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauer, M. W., and R. M. Kelly. 1998. The family 1 β-glucosidases from Pyrococcus furiosus and Agrobacterium faecalis share a common catalytic mechanism. Biochemistry 37:17170-17178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Chem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown, S. H., H. R. Costantino, and R. M. Kelly. 1990. Characterization of amylolytic enzyme activities associated with the hyperthermophilic archaebacterium Pyrococcus furiosus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:1985-1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown, S. H., and R. M. Kelly. 1993. Characterization of amylolytic enzymes, having both α-1,4 and α-1,6 hydrolytic activity from the thermophilic archaea Pyrococcus furiosus and Thermococcus litoralis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:2614-2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brun, E., F. Moriaud, P. Gans, M. J. Blackledge, F. Barras, and D. Marion. 1997. Solution structure of the cellulose-binding domain of the endoglucanase Z secreted by Erwinia chrysanthemi. Biochemistry 36:16074-16086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chitlaru, E., and S. Roseman. 1996. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel β-N-acetyl-d-glucosaminidase from Vibrio furnissii. J. Biol. Chem. 271:33433-33439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper, V. J. C., and G. P. C. Salmond. 1993. Molecular analysis of the major cellulase (CelV) of Erwinia carotovora: evidence for an evolutionary “mix-and-match”of enzyme domains. Mol. Gen. Genet. 241:341-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costantino, H. R., S. H. Brown, and R. M. Kelly. 1990. Purification and characterization of an α-glucosidase from a hyperthermophilic archaebacterium, Pyrococcus furiosus, exhibiting a temperature optimum of 105 to 115°C. J. Bacteriol. 172:3654-3660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies, G., and B. Henrissat. 1995. Structures and mechanisms of glycosyl hydrolases. Structure 3:853-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Din, N., I. J. Forsythe, L. D. Burtnick, N. R. Gilkes, J. Robert C. Miller, R. A. J. Warren, and D. G. Kilburn. 1994. The cellulose-binding domain of endoglucanase A (CenA) from Cellulomonas fimi: evidence for the involvement of tryptophan residues in binding. Mol. Microbiol. 11:747-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong, G., C. Vielle, and J. G. Zeikus. 1997. Cloning, sequencing and expression of the gene encoding amylopullulanase from Pyrococcus furiosus and biochemical characterization of the recombinant enzyme. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3577-3584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Driskill, L. E., K. Kusy, M. W. Bauer, and R. M. Kelly. 1999. Relationship between glycosyl hydrolase inventory and growth physiology of the hyperthermophile Pyrococcus furiosus on carbohydrate-based media. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:893-897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dworkin, M., and H. Reichenbach. 1981. The order Cytophagales (with addenda on the genera Herpetosiphon, Saprospira and Flexitrix), p. 374-376. In M. P. Starr, H. Stolp, H. G. Truper, A. Balows, and H. G. Schlegel (ed.), The prokaryotes. Springer-Verlag, New York, N.Y.

- 18.Erauso, G., A. L. Reysenbach, A. Godfroy, J. R. Meunier, B. Crump, F. Partensky, J. A. Baross, V. Marteinsson, G. Barbier, N. R. Pace, and D. Prieur. 1993. Pyrococcus abyssi sp. nov., a new hyperthermophilic archaeon isolated from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent. Arch. Microbiol. 160:338-349. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fiala, G., and K. O. Stetter. 1986. Pyrococcus furiosus sp. nov. represents a novel genus of marine heterotrophic archaebacteria growing optimally at 100°C. Arch. Microbiol. 145:56-60. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freire, E., and R. L. Biltonen. 1978. Thermodynamics of transfer ribonucleic acids: the effect of sodium on the thermal unfolding of yeast tRNAPhe. Biopolymers 17:1257-1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuchs, R. L., S. A. McPherson, and D. J. Drahos. 1986. Cloning of a Serratia marcescens gene encoding chitinase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 51:504-509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujii, T., and K. Miyashita. 1993. Multiple domain structure in a chitinase gene (Chic) of Streptomyces lividans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139:677-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gal, S. W., J. Y. Choi, C. Y. Kim, Y. H. Cheong, Y. J. Choi, S. Y. Lee, J. D. Bahk, and M. J. Cho. 1998. Cloning of the 52-kDa chitinase gene from Serratia marcescens KCTC2172 and its proteolytic cleavage into an active 35-kDa enzyme. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 160:151-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilkes, N. R., D. G. Kilburn, J. Robert, C. Miller, and R. A. J. Warren. 1989. Structural and functional analysis of a bacterial cellulase by proteolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 264:17802-17808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilkes, N. R., R. A. J. Warren, J. Robert, C. Miller, and D. G. Kilburn. 1988. Precise excision of the cellulose binding domains from two Cellulomonas fimi cellulases by a homologous protease and the effect on catalysis. J. Biol. Chem. 263:10401-10407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gleave, A. P., R. K. Taylor, B. A. M. Morris, and D. R. Greenwood. 1995. Cloning and sequencing of a gene encoding the 69-kDa extracellular chitinase of Janthinobacterium lividum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 131:279-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gooday, G. W. 1991. Chitinase. American Chemical Society, Washington, D.C.

- 28.Gooday, G. W. 1990. The ecology of chitin degradation. Adv. Microb. Ecol. 11:387-430. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gueguen, Y., W. G. B. Voorhorst, J. van den Oost, and W. M. den Vos. 1997. Molecular and biochemicalcharacterization of an endo-β-1,3-glucanase of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Biol. Chem. 272:31258-31264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heijne, G. V. 1986. A new method for predicting signal sequence cleavage sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 14:4683-4690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henrissat, B., and P. M. Coutinho. 2001. Classification of glycoside hydrolases and glycosyltransferases from hyperthermophiles. Methods Enzymol. 330:183-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huber, R., J. Stohr, S. Hohenhaus, R. Rachel, S. Burggraf, H. W. Jannasch, and K. O. Stetter. 1995. Thermococcus chitonophagus sp. nov., a novel, chitin-degrading, hyperthermophilic archaeum from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent environment. Arch. Microbiol. 164:255-264. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inouye, M., and S. Halegoua. 1980. Secretion and membrane localization of proteins in Escherichia coli. CRC Crit. Rev. Biochem. 7:339-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones, J. D. G., K. L. Grady, T. V. Suslow, and J. R. Bedbrook. 1986. Isolation and characterization of genes encoding two chitinase enzymes from Serratia marcescens. EMBO J. 5:467-473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jorgensen, S., C. E. Vorgias, and G. Antranikian. 1997. cloning, sequencing, characterization, and expression of an extracellular α-amylase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus in Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 272:16335-16342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawarabayasi, Y., M. Sawada, H. Horikawa, Y. Haikawa, Y. Hino, S. Yamamoto, M. Sekine, S. Baba, H. Kosugi, A. Hosoyama, Y. Nagai, M. Sakai, O. K., R. Otsuka, H. Nakazawa, M. Takamiya, Y. Ohfuku, T. Funahashi, T. Tanaka, Y. Kudoh, J. Yamazaki, N. Kushida, A. Oguchi, K. Aoki, and H. Kikuchi. 1998. Complete sequence and gene organization of the genome of a hyperthermophilic archaebacterium, Pyrococcus horikoshii OT3. DNA Res. 5:55-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kengen, S. W. M., E. J. Luesink, A. J. M. Stams, and A. J. B. Zehnder. 1993. Purification and characterization of an extremely thermostable β-glucosidase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. Eur. J. Biochem. 213:305-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keyhani, N. O., and S. Roseman. 1996. The chitin catabolic cascade in the marine bacterium Vibrio furnissii: molecular cloning, isolation, and characterization of a periplasmic β-N-acetylglucosaminidase. J. Biol. Chem. 271:33425-33432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keyhani, N. O., and S. Roseman. 1996. The chitin catabolic cascade in the marine bacterium Vibrio furnissii: molecular cloning, isolation, and characterization of a periplasmic chitodextrinase. J. Biol. Chem. 271:33414-33424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klenk, H. P., R. A. Clayton, J. F. Tomb, O. White, K. E. Nelson, K. A. Ketchum, R. J. Dodson, M. Gwinn, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, D. L. Richardson, A. R. Kerlavage, D. E. Graham, N. C. Kyrpides, R. D. Fleischmann, J. Quackenbush, N. H. Lee, G. G. Sutton, S. Gill, E. F. Kirkness, B. A. Dougherty, K. McKenney, M. D. Adams, B. Loftus, J. C. Venter, et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the hyperthermophilic, sulphate-reducing archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Nature 390:364-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laderman, K. A., K. Asada, T. Uemori, H. Mukai, Y. Taguchi, I. Kato, and C. B. Anfinsen. 1993. α-Amylase from the hyperthermophilic archaebacterium Pyrococcus furiosus: cloning and sequencing of the gene and expression in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 268:24402-24407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laderman, K. A., B. R. Davis, H. C. Krutzsch, M. S. Lewis, Y. V. Griko, P. L. Privalov, and C. B. Anfinsen. 1993. The purification and characterization of an extremely thermostable α-amylase from the hyperthermophilic archaebacterium Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Biol. Chem. 268:24394-24401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lonhienne, T., K. Mavromatis, C. E. Vorgias, L. Buchon, C. Gerday, and V. Bouriotis. 2001. Cloning, sequences, and characterization of two chitinase genes from the Antarctic Arthrobacter sp. strain TAD20: isolation and partial characterization of the enzymes. J. Bacteriol. 183:1773-1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maeder, D. L., R. B. Weiss, D. M. Dunn, J. L. Cherry, J. M. Gonzalez, J. DiRuggiero, and F. T. Robb. 1999. Divergence of the hyperthermophilic archaea Pyrococcus furiosus and Pyrococcus horikoshii inferred from complete genomic sequences. Genetics 152:1299-1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Makhatadze, G. I., V. N. Medvedkin, and P. L. Privalov. 1990. Partial molar volumes of polypeptides and their constituent groups in aqueous solution over a broad temperature range. Biopolymers 30:1001-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45a.Monreal, J., and E. T. Reese. 1969. The chitinase of Serratia marcescens. Can. J. Microbiol. 15:689-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morimoto, K., S. Karita, T. Kimura, K. Sakka, and K. Ohmiya. 1997. Cloning, sequencing and expression of the gene encoding Clostridium paraputrificum chitinase Chi B and analysis of the functions of novel cadherin-like domains and a chitin-binding domain. J. Bacteriol. 179:7306-7314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nelson, K. E., R. A. Clayton, S. R. Gill, M. L. Gwinn, R. J. Dodson, D. H. Haft, E. K. Hickey, L. D. Peterson, W. C. Nelson, K. A. Ketchum, L. McDonald, T. R. Utterback, J. A. Malek, K. D. Linher, M. M. Garrett, A. M. Stewart, M. D. Cotton, M. S. Pratt, C. A. Phillips, D. Richardson, J. Heidelberg, G. G. Sutton, R. D. Fleischmann, J. A. Eisen, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, H. O. Smith, J. C. Venter, and C. M. Fraser. 1999. Evidence for lateral gene transfer between Archaea and Bacteria from genome sequence of Thermotoga maritima. Nature 399:323-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nelson, N. 1944. A photometric adapt of the Somogyi method for the determination of glucose. J. Biol. Chem. 153:375-380. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nielsen, H., S. Brunak, and G. V. Heijne. 1999. Machine learning approaches for the prediction of signal peptides and other protein sorting signals. Protein Eng. 12:3-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perrakis, A., I. Tews, Z. Dauter, A. B. Oppenheim, I. Chet, K. S. Wilson, and C. E. Vorgias. 1994. Crystal structure of a bacterial chitinase at 2.3 Å resolution. Structure 2:1169-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rast, D. M., M. Horsch, R. Furter, and G. W. Gooday. 1991. A complex chitinolytic system in exponentially growing mycelium of Mucor rouxii: properties and function. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137:2797-2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robbins, P. W., K. Overbye, C. Albright, B. Benfield, and J. Pero. 1992. Cloning and high-level expression of chitinase-encoding gene of Streptomyces plicatus. Gene 111:69-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Romaguera, A., U. Menge, R. Breves, and H. Diekmann. 1992. Chitinases of Streptomyces olivaceoviridis and significance of processing for multiplicity. J. Bacteriol. 174:3450-3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saitou, N., and M. Nei. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sakai, K., A. Yokata, H. Kurokawa, M. Wakayama, and M. Moriguchi. 1998. Purification and characterization of three thermostable endochitinases of a noble Bacillus strain, MH-1, isolated from chitin-containing compost. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3397-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salmon, S., and S. M. Hudson. 1997. Crystal morphology, biosynthesis, and physical assembly of cellulose, chitin, and chitosan. Rev. Macromol. Chem. Phys. C37:199-276.

- 57.Shen, H., M. Schmuck, I. Pilz, N. R. Gilkes, D. G. Kilburn, R. C. Miller, Jr., and R. A. Warren. 1991. Deletion of the linker connecting the catalytic and cellulose-binding domains of endoglucanase A (CenA) of Cellulomonas fimi alters its conformation and catalytic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 266:11335-11340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Suzuki, K., M. Taiyoji, N. Sugawara, N. Nikaidou, B. Henrissat, and T. Watanabe. 1999. The third chitinase gene (chiC) of Serratia marcescens 2170 and the relationship of its product to other bacterial chitinases. Biochem. J. 343:587-596. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Svitil, A. L., and D. L. Kirchman. 1998. A chitin-binding domain in a marine bacterial chitinase and other microbial chitinases: implications for the ecology and evolution of 1,4-β-glycanases. Microbiology 144:1299-1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takayanagi, T., K. Ajisaka, Y. Takiguchi, and K. Shimahara. 1991. Isolation and characterization of thermostable chitinases from Bacillus licheniformis X-7u. Biochim. Biophy. Acta 1078:404-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tanaka, T., S. Fujiwara, S. Nishikori, T. Fukui, M. Takagi, and T. Imanaka. 1999. A unique chitinase with dual active site and triple substrate binding sites from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus kodakaraensis KOD1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:5385-5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tanaka, T., T. Fukui, and T. Imanaka. 2001. Different cleavage specificities of the dual catalytic domains in chitinase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakaraensis KOD1. J. Biol. Chem. 276:35629-35635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tomme, P., R. A. J. Warren, and N. R. Gilkes. 1995. Cellulose hydrolysis by bacterial and fungi. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 37:1-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tomme, P., R. A. J. Warren, J. Robert C. Miller, D. G. Kilburn, and N. R. Gilkes (ed.). 1995. Cellulose-binding domians: classification and properties, vol. 1. American Chemical Society, San Diego, Calif.

- 65.Tsujibo, H., H. Orikoshi, K. Shiotani, M. Hayashi, J. Umeda, K. Miyamoto, C. Imada, Y. Okdami, and Y. Inamori. 1998. Characterization of chitinase C from a marine bacterium, Alteromonas sp. strain O-7, and its corresponding gene and domain structure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:472-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ueda, M., T. Kawaguchi, and M. Arai. 1994. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding chitinase II from Aeromonas sp. NO.10S-24. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 78:205-211. [Google Scholar]

- 67.van Aalten, D. M., B. Synstad, M. B. Brurberg, E. Hough, B. W. Riise, V. G. Eijsink, and R. K. Wierenga. 2000. Structure of a two-domain chitotriosidase from Serratia marcescens at 1.9 Å resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:5842-5847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Voorhorst, W. G., R. I. Eggen, E. J. Luesink, and W. M. de Vos. 1995. Characterization of the celB gene coding for β-glucosidase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus and its expression and site-directed mutation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 177:7105-7111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Watanabe, T., Y. Ito, T. Yamada, M. Hashimoto, S. Sekine, and H. Tanaka. 1994. The roles of the C-terminal domain and type III domains of chitinase A1 from Bacillus circulans WL-12 in chitin degradation. J. Bacteriol. 176:4465-4472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Watanabe, T., K. Kimura, T. Sumiya, N. Nikaidou, K. Suzuki, M. Suzuki, M. Taiyoji, S. Ferrer, and M. Regue. 1997. Genetic analysis of the chitinase system of Serratia marcescens 2170. J. Bacteriol. 179:7111-7117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Watanabe, T., K. Kobori, K. Miyashita, T. Fujii, H. Sakai, M. Uchida, and H. Tanaka. 1993. Identification of glutamic acid 204 and aspartic acid 200 in chitinase A1 of Bacillus circulans WL-12 as essential residues for chitinase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 268:18567-18572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Watanabe, T., W. Oyanagi, K. Suzuki, K. Ohnishi, and H. Tanaka. 1992. Structure of the gene encoding chitinase D of Bacillus circulans WL-12 and possible homology of the enzme to other prokaryotic chitinase and class III plant chitinases. J. Bacteriol. 174:408-414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Watanabe, T., K. Suzuki, W. Oyanagi, K. Ohnishi, and H. Tanaka. 1990. Gene cloning of chitinase A1 from Bacillus circulans WL-12 revealed its evolutionary relationship to Serratia chitinase and to the type III homology units of fibronectin. J. Biol. Chem. 265:15659-15665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wilkinson, G. N. 1960. Statistical estimation in enzyme kinetics. Biochem. J. 80:324-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xu, G.-Y., E. Ong, N. R. Gilkes, D. G. Kilburn, D. R. Muhandiram, M. Harris-Brandts, J. P. Carver, L. E. Kay, and T. S. Harvey. 1995. Solution structure of a cellulose-binding domain from Cellulomonas fimi by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochemistry 34:6993-7009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]