Abstract

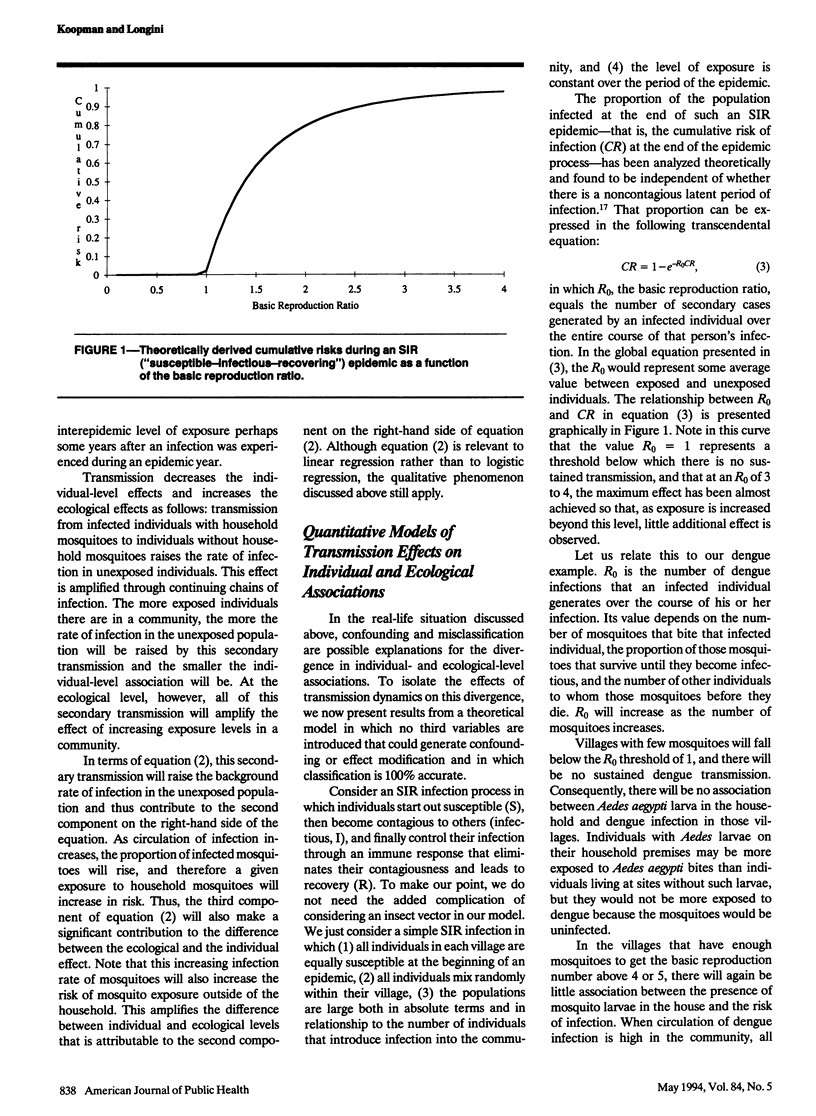

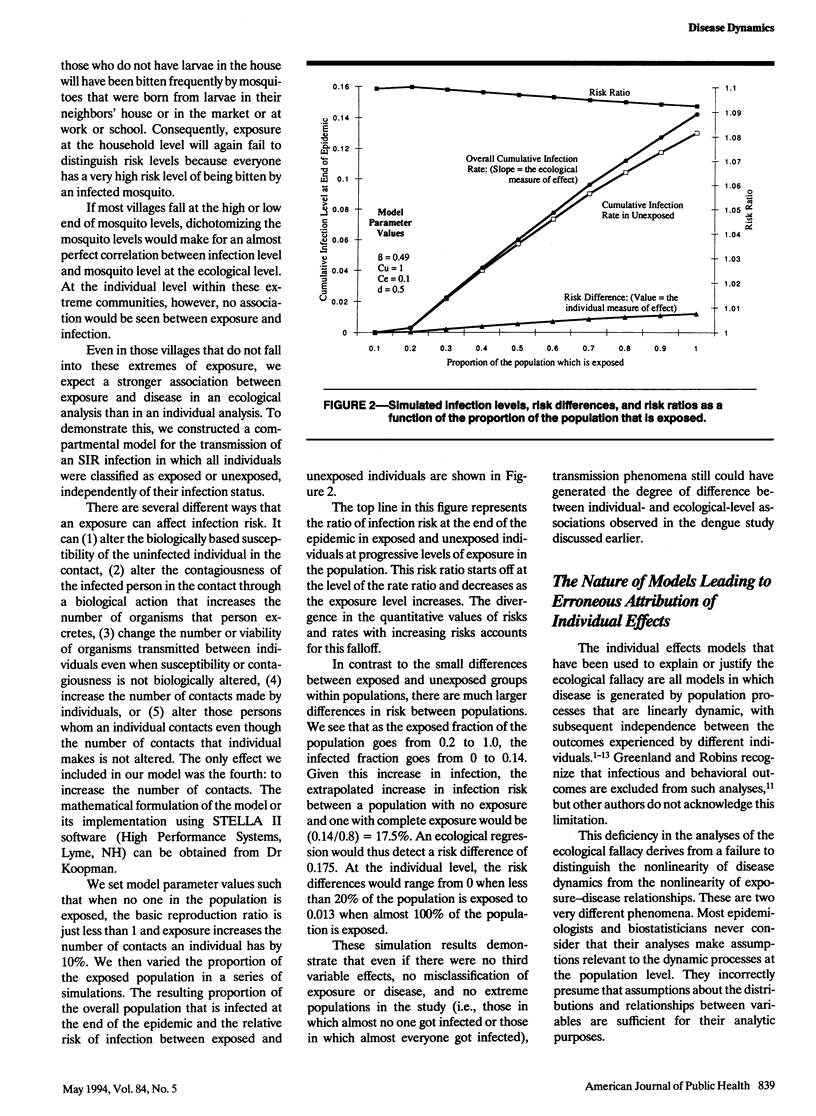

To describe causally predictive relationships, model parameters and the data used to estimate them must correspond to the social context of causal actions. Causes may act directly upon the individual, during a contact between individuals, or upon a group dynamic. Assuming that outcomes in different individuals are independent puts the causal action directly upon individuals. Analyses making this assumption are thus inappropriate for infectious diseases, for which risk factors alter the outcome of contacts between individuals. Transmission during contact generates nonlinear infection dynamics. These dynamics can so attenuate exposure-infection relationships at the individual level that even risk factors causing the vast majority of infections can be missed by individual-level analyses. On the other hand, these dynamics amplify causal associations between exposure and infection at the ecological level. The amplification and attenuation derive from chains of transmission initiated by exposed individuals but involving unexposed individuals. A study of household exposure to the only vector of dengue in Mexico illustrates the phenomenon. An individual-level analysis demonstrated almost no association between exposure and infection. Ecological analysis, in contrast, demonstrated a strong association. Transmission models that are devoid of any sources of the ecological fallacy are used to illustrate how nonlinear dynamics generate such results.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Brenner H., Savitz D. A., Jöckel K. H., Greenland S. Effects of nondifferential exposure misclassification in ecologic studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1992 Jan 1;135(1):85–95. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen B. L. Ecological versus case-control studies for testing a linear-no threshold dose-response relationship. Int J Epidemiol. 1990 Sep;19(3):680–684. doi: 10.1093/ije/19.3.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Alessio D. J., Peterson J. A., Dick C. R., Dick E. C. Transmission of experimental rhinovirus colds in volunteer married couples. J Infect Dis. 1976 Jan;133(1):28–36. doi: 10.1093/infdis/133.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick E. C., Jennings L. C., Mink K. A., Wartgow C. D., Inhorn S. L. Aerosol transmission of rhinovirus colds. J Infect Dis. 1987 Sep;156(3):442–448. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.3.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S. Divergent biases in ecologic and individual-level studies. Stat Med. 1992 Jun 30;11(9):1209–1223. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780110907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S., Morgenstern H. Ecological bias, confounding, and effect modification. Int J Epidemiol. 1989 Mar;18(1):269–274. doi: 10.1093/ije/18.1.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwaltney J. M., Jr, Moskalski P. B., Hendley J. O. Hand-to-hand transmission of rhinovirus colds. Ann Intern Med. 1978 Apr;88(4):463–467. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-88-4-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halloran M. E., Struchiner C. J. Study designs for dependent happenings. Epidemiology. 1991 Sep;2(5):331–338. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman J. S., Longini I. M., Jr, Jacquez J. A., Simon C. P., Ostrow D. G., Martin W. R., Woodcock D. M. Assessing risk factors for transmission of infection. Am J Epidemiol. 1991 Jun 15;133(12):1199–1209. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman J. S., Prevots D. R., Vaca Marin M. A., Gomez Dantes H., Zarate Aquino M. L., Longini I. M., Jr, Sepulveda Amor J. Determinants and predictors of dengue infection in Mexico. Am J Epidemiol. 1991 Jun 1;133(11):1168–1178. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longini I. M., Jr, Koopman J. S., Haber M., Cotsonis G. A. Statistical inference for infectious diseases. Risk-specific household and community transmission parameters. Am J Epidemiol. 1988 Oct;128(4):845–859. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern H. Uses of ecologic analysis in epidemiologic research. Am J Public Health. 1982 Dec;72(12):1336–1344. doi: 10.2105/ajph.72.12.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piantadosi S., Byar D. P., Green S. B. The ecological fallacy. Am J Epidemiol. 1988 May;127(5):893–904. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson S., Stücker I., Hémon D. Comparison of relative risks obtained in ecological and individual studies: some methodological considerations. Int J Epidemiol. 1987 Mar;16(1):111–120. doi: 10.1093/ije/16.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susser M. The logic in ecological: II. The logic of design. Am J Public Health. 1994 May;84(5):830–835. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.5.830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff M., Koepsell T., Curry S., Diehr P. Multi-level analysis in epidemiologic research on health behaviors and outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 1992 May 15;135(10):1077–1082. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]