Abstract

The dairy starter bacterium Lactococcus lactis is able to synthesize folate and accumulates large amounts of folate, predominantly in the polyglutamyl form. Only small amounts of the produced folate are released in the extracellular medium. Five genes involved in folate biosynthesis were identified in a folate gene cluster in L. lactis MG1363: folA, folB, folKE, folP, and folC. The gene folKE encodes the biprotein 2-amino-4-hydroxy-6-hydroxymethyldihydropteridine pyrophosphokinase and GTP cyclohydrolase I. The overexpression of folKE in L. lactis was found to increase the extracellular folate production almost 10-fold, while the total folate production increased almost 3-fold. The controlled combined overexpression of folKE and folC, encoding polyglutamyl folate synthetase, increased the retention of folate in the cell. The cloning and overexpression of folA, encoding dihydrofolate reductase, decreased the folate production twofold, suggesting a feedback inhibition of reduced folates on folate biosynthesis.

Folate is an essential nutrient in the human diet. Folate deficiency leads to numerous physiological disorders, most notably anemia and neural tube defects in newborns (33) and mental disorders such as psychiatric syndromes among the elderly and decreased cognitive performance (7, 21). In addition, folate is assumed to have protective properties against cardiovascular diseases and several types of cancer (5, 6, 33). The daily recommended intake of dietary folate for an adult is 400 μg. For pregnant women, 600 μg is recommended. Recent studies done in The Netherlands and Ireland have indicated that folate deficiency is common even among various population groups in the developed countries, including women of childbearing age (24, 37).

Folate is a general term for a large number of folic acid derivatives that differ by their state of oxidation, one-carbon substitution of the pteridine ring, and the number of glutamate residues. These differences are associated with different physicochemical properties which may influence folate bioavailability, i.e., folate that can directly be absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract. The in vivo function of folate is that of a cofactor that donates one-carbon units in a variety of reactions involved in the de novo biosynthesis of amino acids, purines, and pyrimidines.

Many plants, fungi, and bacteria are able to synthesize folate and can serve as a folate source for the auxotrophic vertebrates. Due to the ability of lactic acid bacteria to produce folate (31), folate levels in fermented dairy products are higher than those in the corresponding nonfermented dairy products (1). The natural diversity among dairy starter cultures with respect to their capacity to produce folate can be exploited to design new complex starter cultures which yield fermented dairy products with elevated folate levels.

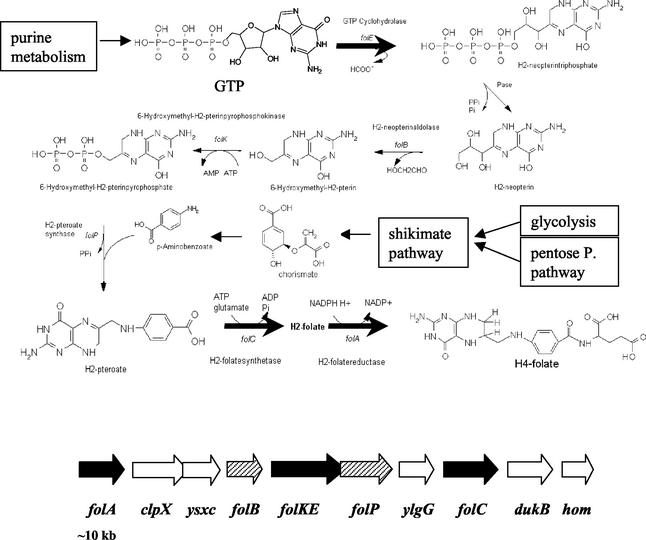

Lactococcus lactis is by far the most extensively studied lactic acid bacterium, and over the last decades a number of elegant and efficient genetic tools have been developed for this starter bacterium. These tools are of critical importance in metabolic engineering strategies that aim at inactivation of undesired genes and/or (controlled) overexpression of existing or novel ones. In this respect, especially the nisin-controlled expression (NICE) system for controlled heterologous and homologous gene expression in L. lactis has proven to be very valuable (9). The design of rational approaches to metabolic engineering requires a proper understanding of the pathways that are manipulated and the genes involved, preferably combined with knowledge about fluxes and control factors. Most of the metabolic engineering strategies so far applied to lactic acid bacteria are related to primary metabolism and comprise efficient rerouting of the lactococcal pyruvate metabolism to end products other than lactic acid, including diacetyl (8, 20, 36, 44) and alanine (18), resulting in high-level production of both natural and novel end products. Metabolic engineering of more complicated pathways involved in secondary metabolism has only recently begun by the engineering of exopolysaccharide production in L. lactis (3, 30, 32, 43). Another complicated pathway is the biosynthesis of folate (13). This biosynthesis includes parts of glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway, and the shikimate pathway for the production of the folate building block p-aminobenzoate, while the biosynthesis of purines is required for the production of the building block GTP (Fig. 1, top). In addition, a number of specific enzymatic steps are involved in the final assembly of folate and for production of the various folate derivatives. The annotated genome sequence of L. lactis subsp. lactis IL1403 (4) reveals the existence of a folate gene cluster containing all genes encoding the folate biosynthesis pathway (Fig. 1, bottom).

FIG. 1.

(Top) Chemical structure of tetrahydrofolate and folate biosynthesis pathway. Thick arrows indicate enzymatic reactions that are controlled in metabolic engineering experiments (see text for details). (Bottom) Schematic representation of the L. lactis folate gene cluster as identified in L. lactis MG1363 and L. lactis IL1403. folKE encodes a bifunctional protein. Hatched arrows represent genes involved in folate biosynthesis, black arrows represent genes involved in folate biosynthesis that are overexpressed in metabolic engineering experiments, and white arrows represent genes that are not expected to be involved in folate biosynthesis.

In the present and previous studies we have used L. lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363 for metabolic engineering experiments (3, 18, 20). Although L. lactis IL1403 and MG1363 show a high degree of homology on the genome level, there are considerable differences (28). For successful application of metabolic engineering in the final steps of the complicated biosynthesis pathway of folate in L. lactis MG1363, characterization of the folate gene cluster in this strain is necessary. The results presented here are an important step in the development of fermented foods with increased bioavailable and natural folate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids, media and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli was grown at 37°C in tryptone yeast medium (40). L. lactis was grown at 30°C in M17 medium (47) supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose. When appropriate, the media contained chloramphenicol (10 μg/ml) or kanamycin (50 μg/ml).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| L. lactis strains | ||

| MG1363 | L. lactis subsp. cremoris, plasmid free | 12 |

| NZ9000 | MG1363 pepN::nisRK | 26 |

| IL1403 | L. lactis subsp. lactis, plasmid free | 4 |

| E. coli strain TOP10 | Cloning host | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR-blunt | Kanr | Invitrogen |

| pCR-blunt-fol | Derivative of pCR-blunt carrying lactococcal folate gene cluster | This study |

| pNZ8048 | Cmr; inducible expression vector carrying nisA promoter | 26 |

| pNZ8160 | Cmr; derivative of pNZ8048 carrying terminator of pepV | This study |

| pNZ8161 | Cmr; derivative of pNZ8160 carrying constitutive promoter of pepN | This study |

| pNZ7010 | Cmr; pNZ8048 derivative containing a functional lactococcal folKE gene behind the nisA promoter | This study |

| pNZ7017 | Cmr; pNZ8161 derivative containing a functional lactococcal folKE behind the constitutive pepN promoter | This study |

| pNZ7011 | Cmr; pNZ8048 derivative containing a functional lactococcal folKE and folC gene behind the nisA promoter | This study |

| pNZ7012 | Cmr; pNZ8048 derivative containing a functional lactococcal folP gene behind the nisA promoter | This study |

| PNZ7013 | Cmr; pNZ8048 derivative containing a functional lactococcal folA gene behind the nisA promoter | This study |

| PNZ7014 | Cmr; pNZ8048 derivative containing antisense RNA of a lactococcal folA gene behind the nisA promoter | This study |

DNA manipulations and transformations.

Isolation of E. coli plasmid DNA and standard recombinant DNA techniques were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (40). Large-scale isolation of E. coli plasmid for nucleotide sequence analysis was performed with JetStar columns by following the instructions of the manufacturer (Genomed, Bad Oeynhausen, Germany). Isolation of chromosomal and plasmid DNAs from L. lactis and transformation of plasmid DNA to L. lactis was performed as previously described (11). Restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase were purchased from Life Technologies BV, Breda, The Netherlands.

PCR amplification of DNA and nucleotide sequence analysis.

Several L. lactis genes were amplified from chromosomal DNA by PCR with 25 ng of DNA in a final volume of 50 μl containing deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates (0.25 to 0.5 mM each), oligonucleotides (50 pM) (Table 2), and 1.0 to 3.0 U of Pfx polymerase (Invitrogen, Paisley, Great Britain) or Taq-Tth polymerase mix (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.). Amplification was performed on a Mastercycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) with 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s (3 min in the first cycle), annealing at 50°C for 30 s, and elongation at 68°C (Pfx) or 72°C (Taq-Tth) for 1 to 8 min. Sequence analysis of the genes involved in folate biosynthesis was done after amplification of a 9-kb DNA fragment flanked by the upstream regions of folA (29) and hom (34) by using primers Fol-F and Hom-R (Table 2) and cloning of the fragment in pCR-BLUNT (Invitrogen), generating pCR-BLUNT-FOL. The generated plasmid was transformed by electroporation to E. coli TOP10 (Invitrogen). The nucleotide sequence of the amplified folate gene cluster was determined by automatic double-stranded DNA sequence analysis with a MegaBACE DNA analysis system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Primer sequences were obtained from published sequence data for folA (29) and hom (34) and by subsequent primer walking. Amplification, cloning, and sequencing were performed twice in independent experiments. Differences in both DNA sequences were reanalyzed after independent amplification and cloning of the regions flanking the ambiguous sequences.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used for DNA amplification by PCR

| Primer | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| Fol-F | CATACCACTTCTTTTTCGATTTGTAAAGG |

| Hom-R | CGATCCCGGGAAGCCCTGTGCCAACTGTCC |

| FolKE-F | CATGCCATGGGGCAAACAACTTATTTAAGCATGG |

| FolKE-R | GGGGTACCGATTCTTGATTAAGTTCTAAG |

| FolC-F | GAAGAGGTACCAGAAGAGTTTAAAAAGTATTATCG |

| FolC-R | TCTCTAGACTACTTTTCTTTTTTCAAAAATTCACG |

| FolP-F | GAATGGTACCTTTAGGAGGTCTTTTATGAAAATCTTAGAAC |

| FolP-R | GAGAAATCAAATCCTCATTCTAGATTAAAATTCC |

| FolA-F | GGAATTCCATGGTTATTGGAATATGGGCAGAAG |

| FolA-R | GCCTCAAGCTTCATGGTTGTTTCACTTTTTC |

| FolA-ASF | GAGGGGTACCTATGATAATTGGAATATGG |

| FolA-ASR | GCCCAAAAATTGATTTTGCCATGGTTG |

| Pcon-F | GAAGATCTGTCGACCTGCAGTAGACAGTTTTTTTAATAAG |

| Pcon-R | CGGGATCCGCATGCCTTCTCCTAAATATTCAGTATTAA |

| TpepV-F | CGGGATCCTTATGAACTTGCAAAATAAG |

| TpepV-R | GAAGATCTCACCTCTATTTCTAGAATAAAG |

| FolKE2-F | ATACATGCATGCAAACAACTTATTTAAGCATGGG |

| FolKE2-R | ATACATGCATGCGATTCTTGATTAAGTTCTAAG |

Underlined nucleotides represent modifications with regard to the mature gene.

Construction of plasmids and transformation of strains.

Lactococcal plasmid pNZ8048 (25, 26) is a translational fusion vector used in nisin-controlled expression systems. The vector contains a nisA promoter and an NcoI cloning site. The gene folKE, encoding a bifunctional protein predicted to display both 2-amino-4-hydroxy-6-hydroxymethyldihydropteridine pyrophosphokinase and GTP cyclohydrolase I activities, was amplified from chromosomal DNA by using primers FolKE-F and FolKE-R (Table 2). The forward primer FolKE-F was extended at the 5′ end, introducing an NcoI restriction site resulting in a slight modification of the mature gene (Table 2). The reverse primer FolKE-R was extended at the 5′ end, introducing a KpnI restriction site. The amplification product was digested with NcoI and KpnI and cloned in pNZ8048 (digested with NcoI and KpnI), thereby placing the folKE gene under the control of nisA. The new plasmid is pNZ7010. The gene folC, encoding a bifunctional protein predicted to display both folate synthetase and polyglutamyl folate synthetase activities, was amplified from chromosomal DNA by using the primers FolC-F and FolC-R (Table 2). Both primers were extended at the 5′ end, introducing a KpnI restriction site and an XbaI restriction site. The amplification product includes a ribosome binding site and was digested with KpnI and XbaI. Next, the gene was cloned in pNZ7010 downstream of folKE, generating pNZ7011. The gene folP, encoding a protein predicted to display dihydropteroate synthase activity, was amplified from chromosomal DNA by using primers FolP-F and FolP-R (Table 2). Both primers were extended at the 5′ end, introducing a KpnI restriction site and an XbaI restriction site. The amplification product includes a ribosome binding site and was digested with KpnI and XbaI and cloned behind folKE in pNZ7010, generating pNZ7012. The gene folA, encoding dihydrofolate reductase, was amplified from chromosomal DNA by using primers FolA-F and FolA-R (Table 2). The forward primer folA-F was extended at the 5′ end, introducing an NcoI restriction site resulting in a slight modification of the mature gene (Table 2). The reverse primer FolA-R was extended at the 5′ end, introducing a HindIII restriction site. The amplification product was digested with NcoI and HindIII and cloned in pNZ8048 (digested with NcoI and HindIII), thereby placing the folA gene under the control of nisA. The new plasmid is pNZ7013. The cloning of the antisense RNA of the gene encoding dihydrofolate reductase was achieved in a way similar to that described for folA, except for the orientation, by using primers FolA-ASF and FolA-ASR (Table 2). The new plasmid is pNZ7014. The generation of a plasmid containing a constitutive promoter and a nisin-inducible promoter separated by a terminator (pNZ8161) was as follows. The terminator from pepV (17) was amplified from chromosomal DNA by using primers TpepV-F and TpepV-R (Table 2). The forward primer TpepV-F was extended at the 5′ end, introducing a BglII restriction site. The reverse primer TpepV-R was extended at the 5′ end, introducing a BamHI restriction site. The amplification product was digested with BglII and BamHI and cloned in pNZ8048-ΔSphI (digested with BglII), generating pNZ8160. The constitutive promoter from pepN (48) was amplified from plasmid pNZ1120 (48) by using primers Pcon-F and Pcon-R (Table 2). The forward primer Pcon-F was extended at the 5′ end, introducing a multiple cloning site including a BglII restriction site. The reverse primer Pcon-R was extended at the 5′ end, introducing BamHI and SphI restriction sites. The amplification product was digested with BglII and BamHI and cloned in pNZ8160 (digested with BamHI), generating pNZ8161. Next, the gene folKE was amplified from chromosomal DNA by using primers FolKE2-F and FolKE2-R (Table 2). Both primers were extended at the 5′ end, introducing an SphI restriction site. The amplification product was digested with SphI and cloned in pNZ8161 (digested with SphI), thereby placing the folKE gene under the control of the constitutive promoter of pepN. The new plasmid is pNZ7017.

L. lactis strain NZ9000 (26) was used as a host for the plasmids described in Table 1. In NZ9000 the genes for a nisin response regulator and a nisin sensor, nisR and nisK, respectively, are stably integrated at the pepN locus in the chromosome, and they are constitutively expressed under the control of the nisR promoter.

Nisin induction.

An overnight culture of L. lactis NZ9000 harboring pNZ8048 or one of the plasmids described above was diluted (1:100) in GM17 supplemented with chloramphenicol and grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5. The cells were induced with different concentrations of nisin A (referred to as nisin) ranging from 0.1 to 5 ng/ml, incubated for 2 h, and harvested for further analysis. The addition of nisin and the subsequent overexpression of genes did not affect the growth characteristics of the engineered strains. Folate was analyzed in cell extracts and fermentation broth, and overproduction of proteins was monitored by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) as described previously (3).

Analysis of intra- and extracellular folate concentrations.

Folate was quantified by using a Lactobacillus casei microbiological assay (19). To measure intra- and extracellular folate concentrations, both cells and supernatant were recovered from a full-grown cell culture (5 ml) after centrifugation (12,000 × g, 10 min, 20°C). The supernatant was diluted 1:1 with 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.8)-1% ascorbic acid. The cells were washed with 0.1 M sodium acetate (pH 4.8)-1% ascorbic acid and resuspended in 5 ml of the same buffer. Folate was released from the cells and from folate binding proteins by incubating the samples at 100°C for 5 min, which was determined to be optimal for maximum folate release. Moreover, the heating inactivates the folate-producing bacteria and prevents their interference in the microbiological folate assay. The microbiological folate assay has nearly equal responses to monoglutamyl folate, diglutamyl folate, and triglutamyl folate, while the response to longer-chain polyglutamyl folate (more than three glutamyl residues) decreases markedly in proportion to chain length (46). Consequently, total folate concentrations can be measured only after deconjugation of the polyglutamyl tails in samples containing folate derivatives with more than three glutamyl residues. The analysis of total folate concentration, including polyglutamyl folate, was done after enzymatic deconjugation of the folate samples for 4 h at 37°C and pH 4.8 with human plasma (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie, Zwijndrecht, The Netherlands) as a source for γ-glutamyl hydrolase activity. The deconjugation reaction mixture was prepared as follows: 1 g of human plasma was diluted in 5 ml of 0.1 M 2-mercaptoethanol-0.5% sodium ascorbate and cleared from precipitates by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 2 min), and a 2.5% (vol/vol) concentration of the clarified human plasma solution was added to the folate samples. The standard deviation of the microbiological assay varied between 0 and 15%. A 1% yeast extract medium solution (Difco, Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems, Sparks, Md.), containing almost exclusively polyglutamyl folates, with a previously determined total folate content was used as a positive control for actual deconjugation.

Dihydrofolate reductase activity.

Forty milliliters of a culture of L. lactis NZ9000 harboring pNZ8048, pNZ7013, or pNZ7014 was grown and induced with nisin as described previously. At an OD600 of 2.5, cells were harvested, washed, and resuspended in 1 ml of buffer (10 mM KPO4, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM EDTA [pH 7.0]). A cell extract was made by addition of 1 g of silica beads to the cell suspension followed by disruption of the cells in an FP120 Fastprep cell disrupter (Savant Instruments Inc., Holbrook, N.Y.) and centrifugation (20,000 × g, 10 min, 0°C). Twenty to 100 μl of the cell extract was used to measure dihydrofolate reductase activity as described previously (38).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper have been submitted to the GenBank database under accession number AY156932.

RESULTS

Sequencing and annotation of a folate gene cluster.

Based upon the genetic organization of a folate gene cluster in L. lactis IL1403 (4), a 9-kb DNA fragment flanked by folA, encoding dihydrofolate reductase, and hom, encoding homoserine dehydrogenase, was amplified from the genome of L. lactis MG1363. In the latter strain the sequence of the genes involved in folate biosynthesis was not yet known, except for folA (29). Its nucleotide sequence was determined and revealed the presence of nine open reading frames, all of which have the same orientation. Sequence comparison with the genome of L. lactis IL1403 showed that the two strains have an identical genetic organization. The nucleotide identity of the folate gene clusters in L. lactis MG1363 and IL1403 is 89%. Only five or six genes in the folate gene cluster appeared to be involved in folate biosynthesis: folA, encoding dihydrofolate reductase (EC 1.5.1.3); folB, predicted to encode neopterine aldolase (EC 4.1.2.25); folK, predicted to encode 2-amino-4-hydroxy-6-hydroxymethyldihydropteridine pyrophosphokinase (EC 2.7.6.3); folE, predicted to encode GTP cyclohydrolase I (EC 3.5.4.16); folP, predicted to encode dihydropteroate synthase (EC 2.5.1.15); and folC, predicted to encode folate synthetase/folyl polyglutamate synthetase (EC 6.3.2.12/6.3.2.17). The remaining genes that were identified in the gene cluster are clpX, predicted to encode an ATP binding protein for ClpP; dukB, predicted to encode a deoxynucleoside kinase (EC 2.7.1.113); and ysxC and ylgG, both encoding unknown proteins. The genes clpX and ysxC may be involved in stress responses (22). The overall amino acid identity of these nine putative proteins between the two L. lactis strains is 90%, ranging from 73% identity for ylgG to 98% for both clpX and dukB. It has been reported previously that in L. lactis folA contains an identified promoter region (29) and that folKE, folP, ylgG, and folC are cotranscribed in a multicistronic operon (45).

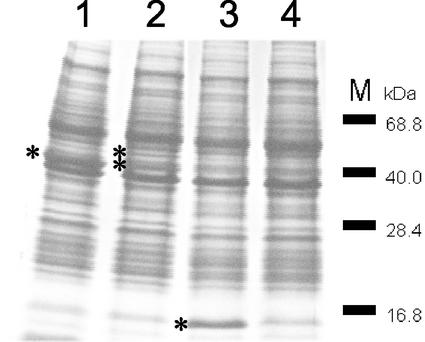

Analysis of the nucleotide sequence of the putative folK and folE genes could identify neither a stop codon at the end of the putative folK gene nor a start codon at the beginning of the putative folE gene. To verify the nature of folK and folE, a DNA sequence comprising both genes was fused to the nisA promoter of pNZ8048, generating pNZ7010, and introduced in L. lactis strain NZ9000. Cells were induced with nisin, and cell extracts were prepared for SDS-PAGE. The Coomassie brilliant blue-stained gel revealed one intense protein band with an apparent molecular mass of 40 kDa, which corresponds to the combined molecular masses of the predicted enzymes encoded by folK and folE. The intense band was absent in a noninduced strain (Fig. 2). It appears that, in contrast to the case for many other microorganisms, in L. lactis the enzymes2-amino-4-hydroxy-6-hydroxymethyldihydropteridine pyro-phosphokinase and GTP cyclohydrolase I are produced as one bifunctional protein and are encoded by one gene, here designated folKE.

FIG. 2.

Coomassie brilliant blue-stained gel after SDS-PAGE of cell extracts from cultures induced with nisin. Molecular markers are indicated on the right. Lanes: 1, overproduction of biprotein 2-amino-4-hydroxy-6-hydroxymethyldihydropteridine pyrophosphokinase and GTP cyclohydrolase I, encoded by folKE; 2, overproduction of the same biprotein and polyglutamyl folate synthetase, encoded by folC; 3, overproduction of dihydrofolate reductase, encoded by folA; 4, control strain. Increased band intensities are indicated by asterisks.

Increased extracellular folate production by overexpression of folKE.

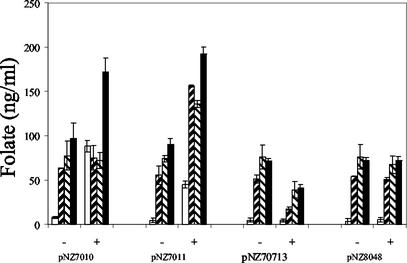

GTP cyclohydrolase I, part of the biprotein encoded by folKE, is the first enzyme in the folate biosynthesis pathway (Fig. 1A). Compared to that in a noninduced strain, the overexpression of folKE in strain NZ9000 harboring pNZ7010 caused an increased concentration of extracellular folate from approximately 10 to 80 ng/ml. Furthermore, the extracellular folate concentration measured for the control strain NZ9000 harboring pNZ8048 was not affected by induction with nisin (Fig. 3). The folate samples were enzymatically deconjugated with human plasma in order to determine whether part of the extracellular folate was present as polyglutamyl folate with more than three glutamate residues that could not be measured by the microbiological assay. However, no difference in folate concentration was measured with or without deconjugase treatment, indicating that the polyglutamyl folate was not excreted by the cells (Fig. 3). The intracellular folate concentration was measured by analyzing cell extracts for the presence of folate. Under inducing conditions, the folKE-overexpressing strain displayed a minor increase in intracellular folate production compared to a control strain or noninduced strain NZ9000 harboring pNZ7010. After deconjugation of the cell extracts, the intracellular folate concentrations were about 80 ng/ml in both strains (Fig. 3). The total folate production by L. lactis was determined by combining the extra- and intracellular folate concentrations. It can be concluded that by overexpression of folKE, the folate production is more than doubled compared to that of a control strain or noninduced NZ9000 harboring pNZ7010. The majority of the extra folate produced is present as extracellular mono-, di-, or triglutamyl folate. The constitutive expression of folKE behind the constitutive promoter of pepN that could be achieved in NZ9000 harboring pNZ7017 resulted in the same increase of folate production as observed by using the NICE system (results not shown).

FIG. 3.

Folate concentrations in different L. lactis strains harboring pNZ8048 (empty vector), pNZ7010 (overexpressing folKE), pNZ7011 (overexpressing folKE and folC), or pNZ7013 (overexpressing folA). Strains were induced with 0 (−) or 2 (+) ng of nisin per ml at an OD600 of 0.5. Folate concentrations were determined at the end of growth, at an OD600 of approximately 2.5. White bars, extracellular folate production; black hatched bars, intracellular folate production; white hatched bars, intracellular folate production after deconjugation; black bars, total folate production. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

Increased intracellular folate production by combined overexpression of folate genes.

The extra- and intracellular folate distribution is assumed to be controlled by the ratio of mono- and polyglutamyl folates (35). The enzyme responsible for the synthesis of polyglutamyl folate is polyglutamyl folate synthetase encoded by folC. The simultaneous overexpression of folKE and folC (NZ9000 harboring pNZ7011) could be visualized by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2). The overexpression of both genes resulted in a more than twofold increase in total folate production, similar to what was observed with overexpression of only folKE. However, differences were detected in the folate distribution. In contrast to the folate produced by the overexpression of folKE only, the majority of the extra folate produced was present as intracellular folate in the folKE- and folC-overexpressing strain. After deconjugation of the intracellular folate, no increased folate concentrations were detected, indicating that the overexpression of folKE and folC had no significant effect on the amount of polyglutamyl folates with more than three glutamate residues (Fig. 3). The overexpression of folKE and folP, encoding dihydropteroate synthase, was achieved by inducing strain NZ9000 harboring pNZ7012. However, no differences in folate concentration or folate distribution were observed compared to the overexpression of only folKE (results not shown).

Altered folate production by overexpression of folA or antisense folA.

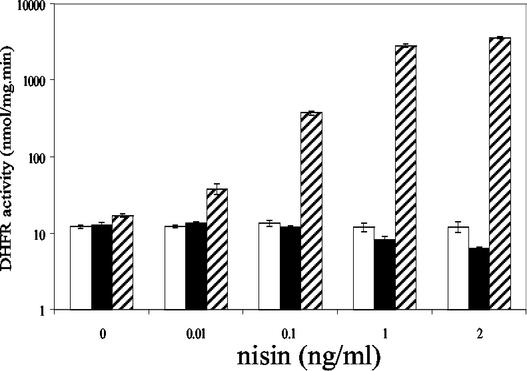

To gain further insight into folate biosynthesis control in L. lactis, the gene folA, encoding dihydrofolate reductase, was also overexpressed. In a similar way as described previously, the induction of strain NZ9000 harboring pNZ7013 resulted in production of the enzyme with a predicted molecular mass of 15 kDa at a level that could be visualized by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2). The overexpression of folA caused a twofold decrease in folate production compared to that in a control strain or a noninduced strain (Fig. 3). The intracellular folate distribution and the relative amount of polyglutamyl folates remained unchanged. In a similar experiment we studied the effect of the production of antisense RNA encoding dihydrofolate reductase. The complementary sequence of the coding strand of folA was cloned under the control of the nisin promoter nisA in pNZ8048, starting at the 5′ end with the complementary sequence of the stop codon of folA and finishing at the 3′ end with the complementary start codon of the gene. The plasmid generated, pNZ7014, was transformed into L. lactis NZ9000. Under inducing conditions, a small but reproducible increase of approximately 20% in the total folate production was observed compared to that in a control strain (results not shown). To confirm the effect of the transcription of folA antisense RNA, the enzymatic activity of dihydrofolate reductase was determined. Cell extracts of strain NZ9000 harboring pNZ7014, transcribing antisense RNA of folA, showed a twofold decrease in dihydrofolate reductase activity (Fig. 4). In contrast, cell extracts of L. lactis strains overexpressing folA showed a more-than-1,000-fold increase in dihydrofolate reductase activity compared to a control strain (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Effect of nisin concentration on dihydrofolate reductase activity measured in cell extracts of L. lactis strains harboring pNZ8048 (empty vector) (white bars), pNZ7013 (overexpressing folA) (hatched bars), or pNZ7014 (overexpressing antisense RNA of folA) (black bars). Error bars indicate standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

We have described successful metabolic engineering of the final part of the complicated biosynthetic pathway of folate biosynthesis and the cloning, sequencing, and analysis of the folate gene cluster in L. lactis MG1363. Homology studies with nonredundant databases show that the folate gene cluster contains folA, encoding dihydrofolate reductase; folB, predicted to encode dihydroneopterin aldolase; folK and folE, encoding thebiprotein 2-amino-4-hydroxy-6-hydroxymethyldihydropteri-dine pyrophosphokinase and GTP cyclohydrolase I; folP, predicted to encode dihydropteroate synthase; and folC, encoding the bifunctional protein folate synthetase and polyglutamyl folate synthetase. The cloning and overexpression of the area comprising folK and folE showed the existence of a bifunctional protein encoded by only one gene, folKE. The other genes present in the folate gene cluster, clpX, ysxC, and ylgG, are not likely to be involved in folate biosynthesis. The gene folE, encoding GTP cyclohydrolase I, was always identified as an independent gene. Comparative genome analysis with nonredundant databases reveals that the gene folK, encoding2-amino-4-hydroxy-6-hydroxymethyldihydropteridine pyro-phosphokinase, may exist as a single gene, but in several microorganisms, e.g., Streptococcus pneumoniae, Clostridium perfringens, Chlamydia trachomatis, Chlamydia muridarum, and Rickettsia conorii, folK forms a biprotein with either folB (neopterin aldolase) or folP (dihydropteroate synthase).

Folate gene clusters have previously been identified in some related microorganisms. In S. pneumoniae and Lactobacillus plantarum, folP, folC, folE, folB, and folK are clustered, but in a different order (23, 27). In Lactobacillus plantarum, a second folC gene was identified outside the folate gene cluster. In Bacillus subtilis, folP, folB, and folK are clustered together with genes involved in p-aminobenzoate synthesis, while folE and folC are far apart in the genome (42).

The NICE system was used to induce overexpression of genes involved in folate biosynthesis. At least three of the genes from the folate gene cluster appeared to be involved in controlling folate biosynthesis and folate distribution in L. lactis: controlled overexpression of folKE increases the extracellular folate production almost 10-fold and the total folate production almost 3-fold; in contrast, the overexpression of folA decreases the total folate production approximately 2-fold. The combined overexpression of folKE and folC favors the intracellular accumulation of folate. Overexpression of the first enzyme of a biosynthetic pathway (GTP cyclohydrolase I) can be a successful strategy to increase the flux through the pathway. Moreover, GTP cyclohydrolase I seems to be a good target for overexpression, since this enzyme in B. subtilis has a low turnover and is not regulated by feedback inhibition (10). The use of an inducible promoter system enables study of the effect of various expression levels of the folate biosynthesis enzymes. However, in food fermentations the use of constitutive promoters is preferred. The cloning of folKE behind the constitutive promoter of pepN resulted in the same increase of folate production as observed by using NICE, although the enzyme production levels were clearly lower. This demonstrates not only that functional expression of folate biosynthesis genes can also be achieved by using a constitutive promoter but also that a further increase in folate production can, presumably, be achieved only by combining folKE overexpression with altered expression of other folate biosynthesis genes.

Most of the folate produced by L. lactis is intracellularly accumulated, and only a minor part of the folate is secreted by the cells. More than 90% of the intracellular folate pool is present in the polyglutamyl form with four, five, and six glutamyl residues (unpublished results). One of the suggested functions of polyglutamylation is retention of folate within the cell (20, 35). Almost all of the extra folate produced by overexpression of folKE is excreted into the environment. We suggest that by the increased flux through the folate biosynthesis pathway, due to the overexpression of folKE, the enzymatic capacity of folate synthetase/polyglutamyl folate synthetase is not sufficient to transform all extra produced folate into the polyglutamyl form, which is necessary for retention of folate within the cell. As a consequence, the retention of folate in the cell is decreased. However, when folKE and folC are simultaneously overexpressed, the majority of the extra folate produced remains intracellular. This confirms that an increased capacity of folate synthetase leads to increased retention of folate in the cell due to an increased enzymatic capacity to elongate the glutamyl tail of the extra folate produced by the overexpression of folKE.

The decrease in folate production by overexpression of folA, encoding dihydrofolate reductase, may indicate a feedback inhibition of its reaction product, tetrahydrofolate, on one of the other enzymes involved in folate biosynthesis. Vinnicombe and Derrick (49) report an inhibiting effect of tetrahydrofolate on dihydropteroate synthase in S. pneumoniae. To further analyze the observed controlling effect of folA, we used the NICE system to produce the antisense RNA of folA and we measured the dihydrofolate reductase activity in vitro. Enzymatic activity was decreased approximately twofold in cells expressing folA antisense RNA. The same cells showed a 20% increase in folate production, confirming the presumable controlling effect of the folA gene product. To further improve our knowledge about the suggested effect of tetrahydrofolate on total folate production, we are working on the substitution of the folA promoter in the chromosome with the nisin-inducible promoter nisA.

It can be assumed that the increase of extracellular folate by overexpression of folKE is due to an increased production of folate with a short polyglutamyl tail, such as monoglutamyl folate. It has been established that the bioavailability of monoglutamyl folate is higher than that of polyglutamyl folate (for reviews, see references 14, 15, and 16). Polyglutamyl folates are available for absorption and metabolic utilization only after enzymatic deconjugation in the small intestine by a mammalian deconjugase enzyme. Only monoglutamyl folate derivatives can be directly absorbed in the human gut. The activity of these deconjugases is susceptible to inhibition by various constituents found in some foods (2, 39, 41). Furthermore, the intracellular polyglutamyl folate may not be available for absorption by the gastrointestinal tract of the consumer if the folate is not released by the (mostly dead) microorganisms. In feeding trials, using rats as an animal model, we will investigate whether besides the increase in folate production, the folate bioavailability also will increase in cells overexpressing folKE.

Previous studies have shown that metabolic engineering can be well applied in rerouting of the lactococcal primary metabolism to end products other than lactic acid. This study has demonstrated that metabolic engineering can also be used for controlling secondary metabolism, such as the more complex folate biosynthesis pathway. Moreover, the results described here provide a basis for further development of functional foods with increased levels of folate. By using high-folate-producing starter bacteria, fermented dairy products with increased folate levels will become available, which will have a much higher contribution to the human daily folate intake than the 15 to 20% that, on average, is currently contributed by dairy products. Recent studies have shown that fermented foods are among the 15 most important food items contributing to the folate intake (25). In some countries other important sources of folate are synthetic folic acid supplements. The differences between bioavailabilities of synthetic forms of folate and natural forms of folate have not been unambiguously determined (15). However, folate-fortified foods are not widely available all over the world, because of either legislation or limited industrial development. In such cases the increase of folate bioavailability from natural sources may contribute significantly to the general health status of the population.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alm, L. 1980. Effect of fermentation on B-vitamins content of milk in Sweden. J. Dairy Sci. 65:353-359. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhandari, S. D., and J. F. Gregory. 1990. Inhibition by selected food components of human and porcine intestinal pteroylpolyglutamate hydrolase activity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 51:87-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boels, I. C., A. Ramos, M. Kleerebezem, and W. M. de Vos. 2001. Functional analysis of the Lactococcus lactis galU and galE genes and their impact on sugar nucleotide and exopolysaccharide biosynthesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3033-3040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolotin, A., P. Wincker, S. Mauger, O. Jaillon, K. Malarme, J. Weissenbach, S. D. Ehrlich, and A. Sorokin. 2001. The complete genome sequence of the lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis IL1403. Genome Res. 11:731-753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boushey, C. J., S. A. Beresford, G. S. Omenn, and A. G. Motulsky. 1995. A quantitative assessment of plasma homocysteine as a risk factor for vascular disease. Probable benefits of increasing folic acid intakes. JAMA 274:1049-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brattstrom, L., and D. E. Wilcken. 2000. Homocysteine and cardiovascular disease: cause or effect? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 72:315-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calvaresi, E., and J. Bryan. 2001. B vitamins, cognition, and aging: a review. J. Gerontol. B 56:327-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curic, M., M. de Richelieu, C. M. Henriksen, K. V. Jochumsen, J. Villadsen, and D. Nilsson. 1999. Glucose/citrate cometabolism in Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis biovar diacetylactis with impaired alpha-acetolactate decarboxylase. Metabol. Eng. 1:291-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Ruyter, P. G., O. P. Kuipers, and W. M. de Vos. 1996. Controlled gene expression systems for Lactococcus lactis with the food-grade inducer nisin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:3662-3667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Saizieu, A., P. Vankan, and A. P. van Loon. 1995. Enzymatic characterization of Bacillus subtilis GTP cyclohydrolase. I. Evidence for a chemical dephosphorylation of dihydroneopterin triphosphate. Biochem. J. 306:371-377. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Vos, W. M., P. Vos, H. de Haard, and I. Boerrigter. 1989. Cloning and expression of the Lactococcus lactis SK11 gene encoding an extracellular serine proteinase. Gene 85:169-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gasson, M. J. 1983. Plasmid complements of Streptococcus lactis NCDO 712 and other lactic streptococci after protoplast-induced curing. J. Bacteriol. 154:1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green, J., B. P. Nichols, and R. G. Matthews. 1996. Folate biosynthesis, reduction, and polyglutamylation, p. 665-673. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 14.Gregory, J. F. 1989. Chemical and nutritional aspects of folate research: analytical procedures, methods of folate synthesis, stability, and bioavailability of dietary folates. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 33:1-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gregory, J. F. 1995. The bioavailability of folate, p. 195-235. In L. B. Bailey (ed.), Folate in health and disease, 1st ed. Marcel Dekker, New York, N.Y.

- 16.Gregory, J. F. 2001. Case study: folate bioavailability. J. Nutr. 131:1376S-1382S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hellendoorn, M. A., B. M. Franke-Fayard, I. Mierau, G. Venema, and J. Kok. 1997. Cloning and analysis of the pepV dipeptidase gene of Lactococcus lactis MG1363. J. Bacteriol. 179:3410-3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hols, P., M. Kleerebezem, A. N. Schanck, T. Ferain, J. Hugenholtz, J. Delcour, and W. M. de Vos. 1999. Conversion of Lactococcus lactis from homolactic to homoalanine fermentation through metabolic engineering. Nat. Biotechnol. 17:588-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horne, D. W., and D. Patterson. 1988. Lactobacillus casei microbiological assay of folic acid derivatives in 96-well microtiter plates. Clin. Chem. 34:2357-2359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hugenholtz, J., M. Kleerebezem, M. Starrenburg, J. Delcour, W. M. de Vos, and P. Hols. 2000. Lactococcus lactis as a cell factory for high-level diacetyl production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4112-4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hultberg, B., A. Isaksson, K. Nilsson, and L. Gustafson. 2001. Markers for the functional availability of cobalamin/folate and their association with neuropsychiatric symptoms in the elderly. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 16:873-878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jobin, M. P., D. Garmyn, C. Divies, and J. Guzzo. 1999. Oenococcus oeni clpX homologue is a heat shock gene preferentially expressed in exponential growth phase. J. Bacteriol. 181:6634-6641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleerebezem M., et al. 2002. Complete genome sequence of Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:1990-1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Konings, E. J., H. H. Roomans, E. Dorant, R. A. Goldbohm, W. H. Saris, and P. A. van den Brandt. 2001. Folate intake of the Dutch population according to newly established liquid chromatography data for foods. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 73:765-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuipers, O. P., P. G. de Ruyter, M. Kleerebezem, and W. M. de Vos. 1997. Controlled overproduction of proteins by lactic acid bacteria. Trends Biotechnol. 15:135-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuipers, O. P., P. G. de Ruyter, M. Kleerebezem, and W. M. de Vos. 1998. Quorum sensing-controlled gene expression in lactic acid bacteria. J. Biotechnol. 64:15-21. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lacks, S. A., B. Greenberg, and P. Lopez. 1995. A cluster of four genes encoding enzymes for five steps in the folate biosynthetic pathway of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 177:66-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le Bourgeois, P., M. Lautier, L. van den Berghe, M. J. Gasson, and P. Ritzenthaler. 1995. Physical and genetic map of the Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363 chromosome: comparison with that of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis IL1403 reveals a large genome inversion. J. Bacteriol. 177:2840-2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leszczynska, K., A. Bolhuis, K. Leenhouts, G. Venema, and P. Ceglowski. 1995. Cloning and molecular analysis of the dihydrofolate reductase gene from Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:561-566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levander, F., M. Svensson, and P. Radstrom. 2002. Enhanced exopolysaccharide production by metabolic engineering of Streptococcus thermophilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:784-790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin, M. Y., and C. M. Young. 2000. Folate levels in cultures of lactic acid bacteria. Int. Dairy J. 10:409-414. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Looijesteijn, P. J., W. H. van Casteren, R. Tuinier, C. H. Doeswijk-Voragen, and J. Hugenholtz. 2000. Influence of different substrate limitations on the yield, composition and molecular mass of exopolysaccharides produced by Lactococcus lactis in continuous cultures. J. Appl. Microbiol. 89:116-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lucock, M. 2000. Folic acid: nutritional biochemistry, molecular biology, and role in disease processes. Mol. Genet. Metab. 71:121-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Madsen, S. M., B. Albrechtsen, E. B. Hansen, and H. Israelsen. 1996. Cloning and transcriptional analysis of two threonine biosynthetic genes from Lactococcus lactis MG1614. J. Bacteriol. 178:3689-3694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGuire, J. J., and J. R. Bertino. 1981. Enzymatic synthesis and function of folylpolyglutamates. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 38:19-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Melchiorsen, C. R., K. V. Jokumsen, J. Villadsen, H. Israelsen, and J. Arnau. 2002. The level of pyruvate-formate lyase controls the shift from homolactic to mixed-acid product formation in Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 58:338-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Brien, M. M., M. Kiely, M., K. E. Harrington, P. J., Robson, J. J. Strain, and A. Flynn. 2001. The efficacy and safety of nutritional supplement use in a representative sample of adults in the North/South Ireland Food Consumption Survey. Public Health Nutr. 4:1069-1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohmae, E., Y. Sasaki, and K. Gekko. 2001. Effects of five-tryptophan mutations on structure, stability and function of Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 130:439-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenberg, I. H., and H. A. Godwin. 1971. Inhibition of intestinal gamma-glutamyl carboxypeptidase by yeast nucleic acid: an explanation of variability in utilization of dietary polyglutamyl folate. J. Clin. Investig. 50:78. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 41.Seyoum, E., and J. Selhub. 1998. Properties of food folates determined by stability and susceptibility to intestinal pteroylpolyglutamate hydrolase action. J. Nutr. 128:1956-1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Slock, J., D. P. Stahly, C. Y. Han, E. W. Six, and I. P. Crawford. 1990. An apparent Bacillus subtilis folic acid biosynthetic operon containing pab, an amphibolic trpG gene, a third gene required for synthesis of para-aminobenzoic acid, and the dihydropteroate synthase gene. J. Bacteriol. 172:7211-7226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stingele, F., S. J. Vincent, E. J. Faber, J. W. Newell, J. P. Kamerling, and J. R. Neeser. 1999. Introduction of the exopolysaccharide gene cluster from Streptococcus thermophilus Sfi6 into Lactococcus lactis MG1363: production and characterization of an altered polysaccharide. Mol. Microbiol. 32:1287-1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Swindell, S. R., K. H. Benson, H. G. Griffin, P. Renault, S. D. Ehrlich, and M. J. Gasson. 1996. Genetic manipulation of the pathway for diacetyl metabolism in Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:2641-2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sybesma, W., J. Hugenholtz, I. Mierau, and M. Kleerebezem. 2001. Improved efficiency and reliability of RT-PCR using tag-extended RT primers and temperature gradient PCR. BioTechniques 31:466-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tamura, T., Y. S. Shin, M. A. Williams, and E. L. R. Stokstad. 1972. Lactobacillus casei response to pteroylpolyglutamates. Anal. Biochem. 49:517-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Terzaghi, B. E., and W. E. Sandine. 1975. Improved medium for lactic streptococci and their bacteriophages. Appl. Microbiol. 29:807-813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Alen-Boerrigter, I. J., R. Baankreis, and W. M. de Vos. 1991. Characterization and overexpression of the Lactococcus lactis pepN gene and localization of its product, aminopeptidase N. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:2555-2561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vinnicombe, H. G., and J. P. Derrick. 1999. Dihydropteroate synthase from Streptococcus pneumoniae: characterization of substrate binding order and sulfonamide inhibition. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 258:752-757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]