Abstract

The capacity of Listeria monocytogenes to tolerate salt and alkaline stresses is of particular importance, as this pathogen is often exposed to such environments during food processing and food preservation. We screened a library of Tn917-lacZ insertional mutants in order to identify genes involved in salt and/or alkaline tolerance. We isolated six mutants sensitive to salt stress and 12 mutants sensitive to salt and alkaline stresses. The position of the insertion of the transposon was located in 15 of these mutants. In six mutants the transposon was inserted in intergenic regions, and in nine mutants it was inserted in genes. Most of the genes have unknown functions, but sequence comparisons indicated that they encode putative transporters.

Listeria monocytogenes is a food-borne pathogen that is widely distributed in the environment. This microorganism is of particular concern in the food industry because of its ability to survive, and frequently to grow, under a wide range of adverse conditions used to preserve food, such as low temperature, low pH, and high osmolarity, or used to clean and sanitize equipment, such as high pH (8). Growth of L. monocytogenes has been reported at NaCl concentrations as high as 10% (24) and at pHs as high as 9 (4, 38).

There is little information on the mechanisms that allow this bacterium to cope with alkaline environments. Knowledge concerning the mechanisms used by gram-positive bacteria for adaptation and growth at alkaline pHs comes mainly from studies of alkaliphilic strains of Bacillus species, such as Bacillus halodurans C-125 or Bacillus pseudofirmus OF4. There is strong evidence that monovalent cation-proton antiporters are essential for maintaining a neutral cytoplasmic pH and, therefore, for growth under alkaline conditions. In addition, the acidic cell wall polymers teichuronic acid and teichuronopeptides contribute to pH homeostasis. These wall macromolecules may provide a passive barrier to ion flux and elevation of the cytoplasmic buffering capacity at highly alkaline growth pHs (19-21). In Bacillus subtilis, monovalent cation/proton antiporters also seem to be important since the mrpA gene encoding an Na+/H+ antiporter and the tetA(L) gene encoding a multifunctional tetracycline-metal/H+ antiporter that also exhibits monovalent cation/H+ antiport activity are involved in Na+-dependent pH homeostasis (13, 14, 39).

Most bacteria cope with elevated osmolarity in the environment by intracellular accumulation of particular osmolytes called compatible solutes. These compatible solutes act in the cytosol by counterbalancing the external osmolarity, thus preventing water loss from the cell and plasmolysis without adversely affecting macromolecular structure and function. Compatible solutes can be either transported into the cell or synthesized de novo (6, 35). Survival of L. monocytogenes at high salt concentrations is attributed mainly to the accumulation of three compatible solutes: glycine betaine, carnitine, and proline (2). Accumulation of glycine betaine and carnitine occurs via two glycine betaine transporters encoded by the betL gene and the gbu operon and one carnitine transporter encoded by the opuC operon. Disruption of these genes reduced the osmotolerance of L. monocytogenes (9, 18, 33, 40). Both betL and opuC have putative σB-dependent promoters (9, 33). The absence of σB impaired the ability of L. monocytogenes to use glycine betaine or carnitine as a compatible solute (1). Proline transport has not been characterized yet. However, disruption of the proBA operon (proline biosynthesis-encoding operon) reduced the growth of the corresponding mutant at high salt concentrations (34). Little information is available concerning other mechanisms that L. monocytogenes uses to cope with salt stress, especially when compatible solutes are not available in the environment. Two genes, clpC and clpP, encoding a ClpC ATPase and a ClpP serine protease, respectively, have been identified (10, 31). Inactivation of these genes conferred a general stress sensitivity phenotype, including sensitivity to salt stress, to the corresponding mutant. In a recent study workers identified relA, a gene encoding a (p)ppGpp synthetase, as a gene involved in osmotolerance via a mechanism different from the mechanism involving accumulation of compatible solutes (29). It has also been shown that the general stress protein Ctc of L. monocytogenes is involved in osmotolerance in the absence of any compatible solutes in the environment (11).

In order to obtain a better understanding of the mechanisms involved in salt and alkaline tolerance, we used a library of transposon insertional mutants of L. monocytogenes LO28 to isolate mutants with decreased NaCl and/or alkaline tolerance. We succeeded in identifying different mutants that exhibit less resistance to salt and/or alkaline stress than the parental strain and characterized the genes interrupted.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The L. monocytogenes strains used were LO28, a clinical isolate of serotype 1/2C, and a library of Tn917-lacZ mutants of strain LO28 (25, 30). Bacterial plasmids were propagated in Escherichia coli strain TG1 (32).

Culture media and stress conditions.

Cells were grown on complex culture media, including brain heat infusion (BHI) broth or agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). Screening of the library of Tn917-lacZ mutants for sensitivity to salt and alkaline stresses was performed as follows. Wells of microplates containing 100 μl of BHI medium with erythromycin (BHI-erm) were inoculated with the different mutants. The microplates were incubated at 37°C overnight and subsequently used to transfer the mutants, after 1:1 dilution with BHI-erm, onto agar plates with a replicator. The plates used contained BHI-erm with or without 5.5% NaCl (final concentration, 6%) and BHI-erm adjusted to pH 8.6 with NaOH. The growth of the mutants was recorded after 48 h. Mutants selected after this first step were used to perform liquid growth experiments with a Microbiology Reader Bioscreen C (Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland) in 100-well sterile microplates, and each well contained 300 μl of culture medium, as follows. Overnight cultures of Tn917-lacZ mutants in BHI-erm were used to inoculate different media (BHI-erm with or without 5.5% NaCl and BHI-erm with the pH adjusted to 8.5) at an initial optical density at 600 nm of ∼0.1. The cultures were incubated with shaking at 37°C. The optical density was monitored at 600 nm. Experiments were repeated independently at least twice. The LO28 strain was used as a control and was inoculated into BHI medium lacking erythromycin. For more detailed physiological characterization of mutants sal5 and sal11, liquid growth experiments were performed by using the same procedure except that the pH of BHI medium was adjusted to 8.5 with a glycine-NaOH-NaCl buffer. Growth experiments were also performed in BHI medium supplemented with 7% KCl or 15% xylose and were repeated independently at least four times. Growth curves were fitted by using a modified Gompertz equation (41), and the generation time was calculated by using nonlinear regression with the Statistica statistical software (Statsoft, Tulsa, Okla.).

Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: 100 μg of ampicillin ml−1 for E. coli and 5 μg of erythromycin ml−1 for L. monocytogenes.

Identification of transposition target.

Inverse PCR was used to amplify the DNA fragment next to the region downstream from the Tn917-lacZ chromosomal insertions. Bacterial chromosomal DNA was isolated as described previously (26). Chromosomal DNA was digested with HindIII for mutants sal1, -2, -5, -6, -11, -17, -22, and -23 and mutants sl7, -10, -13, -14, and -25 and with NdeI for mutants sl12 and sal21 and was subsequently circularized by self-ligation. The region downstream from the Tn917-lacZ insertion was amplified by using primers RG7 (5′-ATTCCGTCTGAAGCAGTGGT-3′) and RG9 (5′-GAACGCCGTCTACTTACAAG-3′) for HindIII-digested DNA and primers RG9 and RG11 (5′-GAATCACGTGTCCCTTTGCG-3′) for NdeI-digested DNA. Amplification products were sequenced either directly or after they were cloned into the pGEM-T plasmid (Promega France, Charbonnières, France), a 3′ T-end vector specifically designed for cloning PCR fragments, by following the manufacturer's specifications. DNA sequencing was done with a BigDye terminator cycle sequencing Ready Reaction kit (Applied Biosystems, Courtaboeuf, France). The reactions were performed with unlabeled primers and fluorescent dideoxynucleotides, and then the reaction mixtures were analyzed with an automatic DNA sequencer (ABI Prism 310 genetic sequencer; Applied Biosystems). Blast sequence homology analyses were performed by using the National Center for Biotechnology Information network service. The primers used for the sequence were RG1 (5′-CCCACTAAGCGCTCGGG-3′), RG7, and RG9. Oligonucleotides were synthesized by MGW-Biotech (Courtaboeuf, France).

RESULTS

Selection of salt and alkaline stress-sensitive mutants.

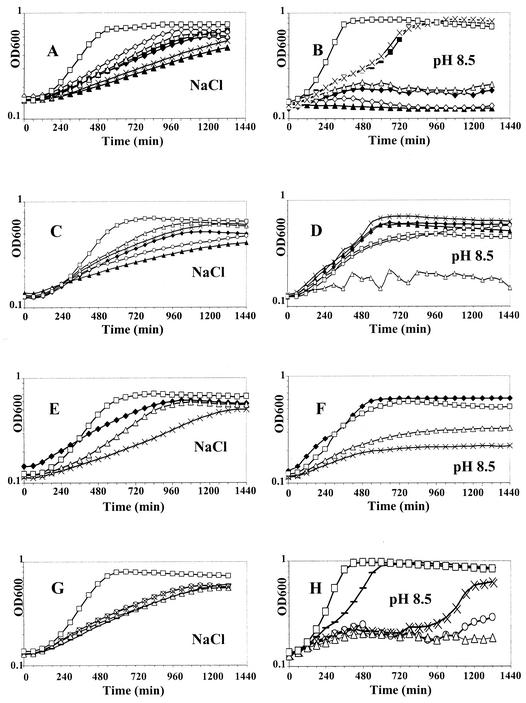

A library of approximately 2,500 Tn917-lacZ insertion mutants was screened for salt and/or alkaline stress sensitivity. Each mutant was grown on BHI-erm plates with or without 5.5% NaCl or with the pH adjusted to 8.6. Twenty-three mutants showed a growth delay on at least one of the two stress media. Six mutants seemed to be affected under salt stress conditions, nine mutants seemed to be affected under alkaline stress conditions, and eight mutants seemed to be affected under both conditions. The phenotypes of the mutants were further confirmed in liquid growth experiments by comparing the growth curves to that of the LO28 wild-type strain. Five mutants were removed after this second step. The growth of two mutants sensitive to both stresses was impaired in BHI medium, and the alkaline sensitivity phenotype of three mutants was not confirmed. Finally, we isolated six mutants sensitive to salt stress and 12 mutants sensitive to both salt stress and alkaline stress. Results of one growth experiment are presented in Fig. 1 for these 18 mutants. The designations of mutants that were sensitive only to salt stress begin with sl (for salt sensitivity locus), and the designations of mutants that were that were sensitive to salt stress and alkaline stress begin with sal (for salt and alkaline sensitivity locus). Southern hybridization with HindIII-digested chromosomal DNA and, when required, EcoRI-digested chromosomal DNA with a digoxigenin-labeled DNA probe specific for the Tn917-lacZ transposon revealed that the 18 mutants contained a single copy of the transposon and that the loci corresponded to 18 independent insertion loci (data not shown). The 18 remaining mutants were kept for further characterization.

FIG. 1.

Growth of the wild-type strain and sal and sl mutant strains of L. monocytogenes LO28 in BHI medium supplemented with 5.5% NaCl (A, C, E, and G) and in BHI medium with the pH adjusted to 8.5 (B, D, F, and H). (A and B) Symbols: □, wild-type strain LO28; ⧫, sal1 mutant; ▪, sal2 mutant; ▴, sal3 mutant; ◊, sal4 mutant; ▵, sal5 mutant; ×, sal6 mutant. (C and D) Symbols: □, wild-type strain LO28; ▴, sl7 mutant; ×, sl10 mutant; ▵, sal11 mutant; ⧫, sl12 mutant; ○, sl13 mutant. (E and F) Symbols: □, wild-type strain LO28; ⧫, sl14 mutant; ▵, sal17 mutant; ×, sal19 mutant. (G and H) Symbols: □, wild-type strain LO28; ○, sal21 mutant; ▵, sal22 mutant; ×, sal23 mutant; −, sl25 mutant. OD600, optical density at 600 nm.

Identification of the transposition target.

The inverse PCR method enabled us to clone and sequence the downstream transposon-chromosome junctions of 15 mutants. We did not succeed in cloning the junctions of three mutants, sal3, -4, and -19. The sequences were compared with the complete genome sequence of L. monocytogenes strain EGDe (12), as described below (Table 1). In nine mutants, the transposon was inserted into open reading frames, whereas it was inserted into intergenic regions in six mutants.

TABLE 1.

Characterization of the sl and sal mutants

| Mutant | Gene interrupted (length of corresponding protein [amino acids]) | Homologous protein (% homology)a | Insertion siteb | Putative open reading frame function | Pheno- typec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sal1d | lmo1431 (533) | S. aureus YkpA (75) | nt 1463416, aa 518(−) | ABC transporter (ATP binding protein) | s-a |

| sal2d | lmo1443 (108) | L. lactis Yqfc (49) | nt 1476873, aa 78(−) | Unknown | s-a |

| sal5 | lmo0992 (255) | B. megaterium YkoY (60) | nt 1022828, aa 99(−) | Unknown | s-a |

| sal6 | lmo1013-gbuABC intergenic regiond | nt 1043614 | s-a | ||

| sl7 | lmo1432 (216) | nt 1463589, aa 190(−) | Unknown | s | |

| sl10 | lmo1013-gbuABC intergenic regiond | nt 1043797 | s | ||

| sal11 | lmo0668 (256) | E. coli YadH (69) | nt 706007, aa 210(−) | ABC transporter (permease protein) | s-a |

| sl12d | mutS (860) | B. subtilis MutS (64) | nt 1431926, aa 564(−) | DNA mismatch repair protein | s |

| sl13d | lmo1413-lmo1412 intergenic regiond | nt 1442264 | s | ||

| sl14 | mdrL (397) | Deinococcus radiodurans DR2307 (46) | nt 1440596, aa 392(+) | Multidrug efflux transporter | s |

| sal17 | lmo2232 (434) | B. subtilis YhdP (60) | nt 2322580, aa 183(+) | Unknown | s-a |

| sal21 | lmo1799-lmo1800 intergenic region | nt 1872459 | s-a | ||

| sal22 | lmo1432 (216) | nt 1463618, aa 180(−) | Unknown | s-a | |

| sal23 | lmo1139-lmo1140 intergenic region | nt 1173145 | s-a | ||

| sl25 | lmo2638-lmo2639 intergenic region | nt 2712848 | s |

Organism and protein designation for the amino acid sequence giving the highest homology score when the Fasta program was used. The level of amino acid identity is indicated in parentheses. The Listeria innocua complete genome sequence was removed from the comparison.

Nucleotide (nt) position of the Tn917-lacZ insertion in the L. monocytogenes EGDe genome and (for an interrupted gene) deduced amino acid (aa) position of the Tn917-lacZ-generated interruption in the L. monocytogenes deduced protein. A plus sign in parentheses indicates that lacZ is in the same orientation as the interrupted gene, and a minus sign in parentheses indicates that it is in the opposite orientation.

Phenotype qualitatively defined after liquid growth experiments by comparing the growth curve of the mutant with that of L. monocytogenes strain LO28. s, sensitive to salt stress; s-a, sensitive to both salt and alkaline stresses.

In each mutant, the sequence of the fragment amplified by inverse PCR in the L. monocytogenes LO28 strain differed at one position from the sequence of the corresponding fragment in strain EGDe. In sal1 the A at position 1463373 in strain EGDe is replaced by a G in strain LO28; in sal2 the T at position 1476703 is replaced by a C; in sl12 the G at position 14311866 is replaced by an A; and in sl13 the G at position 1442126 is replaced by a T. In sl13, the difference is in an intergenic region, and in sal1, sal2, and sl12, the differences are within genes. In sal1 and sal12 the difference resulted in no change in the amino acid sequence of the protein, and in sal2 an isoleucine at position 20 in the Lmo1443 protein of the EGDe strain corresponded to a methionine in the LO28 strain.

Genes encoding proteins with an identified function or a putative function.

In the sl12 mutant, the transposon was inserted into the mutS gene, which is involved in DNA mismatch repair (27), whereas in mutants sal1 and -11 and sl14 it was inserted into transporters or putative transporters. In sal1, the transposon was inserted into the ATPase subunit of an ATP binding cassette transporter, and in sal11 it was inserted into the permease subunit of another ATP binding cassette transporter. In sl14, the transposon was inserted into the mdrL gene, which encodes a multidrug efflux transporter of the major facilitator superfamily (23). If the orientation of the genes and the presence of putative terminators were taken into account, the phenotypes of mutants sal1 and -11 and sl14 could not be linked to a polar effect of the mutation on downstream genes. However, the phenotype of mutant sl12 could be linked to a polar effect of the mutation of a downstream gene, mutL coding for a DNA mismatch repair protein or lmo1405 coding for a putative antiterminator regulatory protein.

Genes encoding proteins with unknown functions.

In sl7 and sal22, the transposon was inserted into the lmo1432 gene at positions separated by 29 bp. The deduced protein encoded by the lmo1432 gene is specific to Listeria. In sal2 and -17, the transposon was inserted into two genes, lmo1443 and lmo2232, respectively, which encode proteins having unknown functions in other organisms. lmo1443 has orthologues in different gram-positive bacteria, and lmo2232 has a paralogue (lmo2399) and five orthologues in B. subtilis yhdP, yrkA, yqhB, yugS, and yhdT and in other eubacteria. Considering the orientation of the genes and the presence of putative terminators, the phenotypes of these four mutants could not be linked to a polar effect of the mutation on downstream genes. This was not the case for sal5, in which the transposon was inserted into lmo0992, a gene of unknown function located upstream from lmo0991 which encodes a protein with similarities to NtpJ of Enterococcus hirae, a K+/Na+ transporter (16).

In these five mutants, similarity searches could not assign a putative function to the genes interrupted, but a search for transmembrane domains with the DAS program (5) revealed that all corresponding proteins have putative transmembrane domains.

Intergenic regions.

For six mutants, the position of the insertion of the transposon was located in intergenic regions.

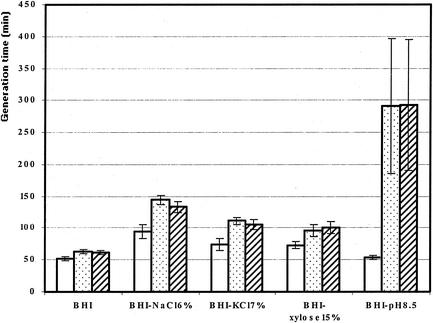

The physiology of two mutants, sal5 and sal11, which were identified as sensitive to salt and alkaline stresses during the screening analysis, was characterized by quantifying the growth of these organisms in different media.

Physiology of the sal5 and sal11 mutants in response to osmotic and alkaline stresses.

Growth of the sal5 and sal11 mutants was examined by using BHI medium, BHI medium supplemented with 5.5% NaCl, 7% KCl, or 15% xylose, and BHI medium with the pH adjusted to 8.5. For the growth experiments under osmotic stress conditions, the concentration of each of the three solutes (NaCl, KCl, and xylose) was approximately 1 M. The results (Fig. 2) showed that the phenotype identified during the screening analysis was confirmed. Both mutants were sensitive to NaCl stress and alkaline stress. However, the sensitivity was far more pronounced with the alkaline stress conditions; under these conditions the growth rate (doubling time) of both mutants was approximately 300 min and was fivefold greater than the growth rate of the wild-type strain. Under NaCl osmotic stress conditions, the growth rates of mutants sal5 and sal11 were 1.4- and 1.3-fold greater, respectively. Moreover, both mutants were also sensitive to KCl stress (but to a lesser extent) and slightly sensitive to xylose stress.

FIG. 2.

Growth rates (doubling times) of wild-type strain LO28 (open bars), the sal5 mutant (stippled bars), and the sal11 mutant (cross-hatched bars) in different media.

DISCUSSION

We isolated six Tn917-lacZ insertional mutants of L. monocytogenes strain LO28 sensitive to salt stress (sl mutants) and nine mutants sensitive to both salt and alkaline stresses (sal mutants) and located the positions of the insertions of the transposons in the genomes of the different mutants. We used the complete genome sequence of L. monocytogenes strain EGDe to rapidly identify the positions of the insertions of the transposons. We sequenced 15 fragments corresponding to a total of 6,249 nucleotides and found only 4 nucleotides which differed in strains LO28 and EGDe. These results suggest that the DNA sequences of these two strains are very similar and justify utilization of the complete genome sequence of L. monocytogenes strain EGDe to study the L. monocytogenes strain LO28 genome.

On the basis of the functions or putative functions of the genes disturbed by insertion of the transposons, we classified the mutants in four categories.

Genes with known functions directly linked to salt stress.

In mutants sal6 and sl10, the transposon was inserted in front of the gbu operon. This operon, which is very similar to the opuA operon of B. subtilis, encodes an ATP-dependent transporter belonging to the ATP binding cassette transporter superfamily and is involved in the transport of glycine betaine. A mutant with this operon inactivated was found to be salt sensitive (18). Ko and Smith also identified sequences with significant similarities to the σA-type −35 and −10 promoter recognition sequence TTGTGT-N15-TATTGC. In the sl10 mutant, the transposon was located between the putative promoter and the coding DNA sequence of the gbu operon. In this mutant, the promoter of the gbu operon is separated from the gbu operon by the transposon. Consequently, the gbu operon cannot be transcribed. The salt stress sensitivity of the sl10 mutant confirmed the results of Ko and Smith (18). This result provides good validation of our screening protocol. In sal6, the transposon was inserted 109 bp upstream from the putative promoter of the gbu operon. This result indicates that regions upstream from the putative promoter are probably involved in the transcription of this operon. In B. subtilis, two promoters have been identified in front of the opuA operon (17), and we hypothesize that this is also the case for L. monocytogenes. Surprisingly, the sal6 mutant was found to be sensitive to salt and alkaline stresses. However, the alkaline phenotype is weak. Using two-dimensional electrophoresis, we identified the GbuA protein, the ATPase subunit of the Gbu transporter, as a protein induced by salt stress (7). In L. monocytogenes, expression of the σB factor is strongly induced by salt stress (1), and consequently, expression of the genes under the control of this sigma factor is also induced by salt stress. However, no σB promoter recognition sequences are present in front of the gbu operon, indicating that another salt induction pathway is present in L. monocytogenes.

Genes with known functions not directly linked to salt stress.

In mutants sl12 and sl14 the transposon was inserted into the mutS and mdrL genes, respectively. The mutSL locus of L. monocytogenes is involved in both mismatch repair and homologous recombination (27). The mdrL gene encodes a multidrug efflux transporter and is involved in the efflux of ethidium bromide (23). In both cases, no salt stress sensitivity of the mdrL or mutSL mutant has been mentioned previously; thus, this is the first time that these two loci have been associated with salt stress. MdrL extrudes different toxic components, and we hypothesize that this transporter also extrudes Na+, perhaps in a nonspecific manner.

Genes encoding putative transporters.

In mutants sal1 and sal11, even though the function is unknown, sequence comparisons indicated a putative function. In both mutants, the transposons were inserted into genes encoding domains of two distinct ATP binding cassette transporters. In sal1, the gene interrupted, ykpA, encodes the ATP binding protein domain of the transporter, and in sal11 the gene interrupted, lmo668, encodes the permease protein domain. ykpA has orthologues in gram-positive bacteria. The corresponding protein has been identified in Staphylococcus aureus as an immunodominant antigen (3), and antisense ablation of the ykpA gene led to a growth-inhibiting effect (15). The lmo668 gene is located downstream from its putative associated ATP binding protein. Lmo668 has very significant similarities with Yadh of gram-negative bacteria. In these cases it is highly probable that ykpA and lmo0668 encode transporters, but the transported solutes remain unknown. The transporters probably extrude Na+ and/or H+, perhaps in a nonspecific manner. Growth experiments with mutant sal11 indicated that the lmo0668 gene is probably involved in pH homeostasis because the sal11 mutant was highly sensitive to alkaline pH, moderately sensitive to NaCl stress, and slightly sensitive to KCl stress and xylose stress. The differences observed among the effects of the three osmolytes, NaCl, KCl, and xylose, which were added at concentrations of approximately 1 M to the medium, were probably due to the fact that NaCl tends to be more stressful than KCl and the fact that xylose provides only one-half the osmotic stress of NaCl and KCl. The last mutant in which expression of genes encoding putative transporters are disturbed is mutant sal5. lmo0992, the gene interrupted by the transposon, belongs to an operon consisting of five genes. The first gene, lmo0989, encodes a putative transcriptional regulator of the MarR family. The next three genes, lmo0990, lmo0991, and lmo0992, encode proteins whose functions are unknown but which are putative integral membrane proteins. Lmo0991 and Lmo0992 are very similar to YkoY of Bacillus megaterium, B. subtilis, and Bacillus anthracis. The last gene, lmo0993, encodes a protein with similarity to the NtpJ protein of E. hirae (33% identity) (36). The ntpJ gene encodes a component of the KtrII uptake system. NtpJ mediates K+ and Na+ cotransport. The growth of an ntpJ-disrupted mutant is impaired at pH 10 in K+-limited medium (16, 28). The phenotypes of an ntpJ-disrupted mutant and the sal5 mutant are similar; the sal5 mutant is highly sensitive to alkaline pH in BHI medium. Thus, the phenotype of the sal5 mutant is probably due to a polar effect of the mutation on lmo0993, the ntpJ-like gene. In E. hirae, the ntpJ gene is the last gene of an operon (ntp) encoding a V-type Na+-ATPase, which is important for Na+ extrusion at high pH. The NtpJ K+/Na+ uptake system functions with the V-type Na+-ATPase at high pH and/or high Na+ concentrations in order to eliminate sodium ions and to drive potassium ion uptake. We found no similarities between the sequences of lmo0990, lmo991, and lmo992 and the sequences of the ntp genes encoding the V-type Na+-ATPase, and further work is needed to check if there is an analogy of function among the genes.

Genes with unknown functions.

For mutants sal2, sl7, sal22, and sal17, the function of the gene interrupted is completely unknown, but the three genes interrupted encode proteins with putative transmembrane domains. The transposon was inserted into the same gene, lmo1432, in mutants sl7 and sal22. This interrupted gene seems to be specific to the genus Listeria. In sal2 the interrupted gene seems to be specific to gram-positive bacteria, whereas in sal17 it seems to be specific to eubacteria. In mutants sal21 and sl25 the transposon was inserted in front of putative operons encoding proteins with unknown functions. We were not able to identify σA-type or σB-type promoter recognition sequences in front of these operons. However, we hypothesize that in these two cases transcription of the operons was eliminated by insertion of the transposon in the promoter region and that the phenotypes of the mutants are linked to at least one of the genes of the operons.

Finally, the salt sensitivity phenotype of mutant sl13 and the salt and alkaline sensitivity phenotype of mutant sal23 are difficult to explain because in sl13 the transposon was inserted between two convergent genes and in sal23 it was inserted between the end and the terminator of the lmo1140 gene.

We did not identify the relA gene during our screening procedure. This gene encodes a (p)ppGpp synthase and was recently identified during a screening procedure very similar to our procedure (29). However, this is not surprising because a library of transposons cannot be exhaustive. Moreover, we did not succeed in identifying the positions of insertion of the transposons in three mutants, and we cannot exclude the possibility that one of these three mutants corresponds to a relA mutant.

We were interested in studying salt stress because it is one of the most commonly used methods for food conservation, and we were interested in studying alkaline stress because of the alkaline nature of most of the detergents and some of the chemical sanitizers used to clean and sanitize equipment in food processing plants. Little information is available concerning the physiology of L. monocytogenes in response to alkaline stress. Growth of food factory isolates was reported at pHs as high as 9 (4, 38), and this pathogen has been shown to be resistant to storage at pHs up to 12 (22). It has also been shown that alkaline pH induces cross-protection of L. monocytogenes against heat (37). Moreover, there is no information concerning the mechanisms that take place in L. monocytogenes in order to cope with alkaline stress. It was interesting to study these two stresses in parallel because a combination of salt stress and alkaline stress is more effective in decreasing the survival of L. monocytogenes than an individual type of stress (38). It is also known that homeostasis of Na+ and H+ ions is tightly linked, and in most cell membranes there are proteins that couple the fluxes of the two ions via the Na+/H+ antiporter or the Ntp complex, for example. During the screening procedure used in this study we identified few genes involved in Na+ and/or alkaline stress tolerance. Further work is needed to investigate the function of these genes, but the fact that they encode putative integral membrane proteins indicates that they probably encode ion transporters.

Acknowledgments

We thank I. Lebert, S. Leroy-Sétrin, R. Talon, and M. Hébraud for constructive discussions and C. Young for correcting the text. We are grateful to E. Gouin for helpful advice concerning the manipulation of the library of transposons.

This work was supported by the Ministère de l'Education Nationale, de la Recherche et de la Technologie.

The European Listeria Genome Consortium is composed of Philippe Glaser, Alexandra Amend, Fernando Baquero-Mochales, Patrick Berche, Helmut Bloecker, Petra Brandt, Carmen Buchrieser, Trinad Chakraborty, Alain Charbit, Elisabeth Couvé, Antoine de Daruvar, Pierre Dehoux, Eugen Domann, Gustavo Dominguez-Bernal, Lionel Durant, Karl-Dieter Entian, Lionel Frangeul, Hafida Fsihi, Francisco Garcia del Portillo, Patricia Garrido, Werner Goebel, Nuria Gomez-Lopez, Torsten Hain, Joerg Hauf, David Jackson, Jurgen Kreft, Frank Kunst, Jorge Mata-Vicente, Eva Ng, Gabriele Nordsiek, Jose Claudio Perez-Diaz, Bettina Remmel, Matthias Rose, Christophe Rusniok, Thomas Schlueter, Jose-Antonio Vazquez-Boland, Hartmut Voss, Jurgen Wehland, and Pascale Cossart.

REFERENCES

- 1.Becker, L. A., M. S. Cetin, R. W. Hutkins, and A. K. Benson. 1998. Identification of the gene encoding the alternative sigma factor σB from Listeria monocytogenes and its role in osmotolerance. J. Bacteriol. 180:4547-4554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beumer, R. R., M. C. Te Giffel, L. J. Cox, F. M. Rombouts, and T. Abee. 1994. Effect of exogenous proline, betaine, and carnitine on growth of Listeria monocytogenes in a minimal medium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1359-1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burnie, J. P., R. C. Matthews, T. Carter, E. Beaulieu, M. Donohoe, C. Chapman, P. Williamson, and S. J. Hodgetts. 2000. Identification of an immunodominant ABC transporter in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Infect. Immun. 68:3200-3209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheroutre-Vialette, M., I. Lebert, M. Hébraud, J. C. Labadie, and A. Lebert. 1998. Effects of pH or a(w) stress on growth of Listeria monocytogenes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 42:71-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cserzo, M., E. Wallin, I. Simon, G. von Heijne, and A. Elofsson. 1997. Prediction of transmembrane alpha-helices in prokaryotic membrane proteins: the dense alignment surface method. Protein Eng. 10:673-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Csonka, L. N., and A. D. Hanson. 1991. Prokaryotic osmoregulation: genetics and physiology. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 45:569-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duché, O., F. Trémoulet, P. Glaser, and J. Labadie. 2002. Salt stress proteins induced in Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1491-1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farber, J. M., and P. I. Peterkin. 1991. Listeria monocytogenes, a food-borne pathogen. Microbiol. Rev. 55:476-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraser, K. R., D. Harvie, P. J. Coote, and C. P. O'Byrne. 2000. Identification and characterization of an ATP binding cassette l-carnitine transporter in Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4696-4704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaillot, O., E. Pellegrini, S. Bregenholt, S. Nair, and P. Berche. 2000. The ClpP serine protease is essential for the intracellular parasitism and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. Mol. Microbiol. 35:1286-1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gardan, R., O. Duché, S. Leroy-Sétrin, The European Listeria Genome Consortium, and J. Labadie. 2003. Role of ctc from Listeria monocytogenes in osmotolerance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:154-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glaser, P., L. Frangeul, C. Buchrieser, C. Rusniok, A. Amend, F. Baquero, P. Berche, H. Bloecker, P. Brandt, T. Chakraborty, A. Charbit, F. Chetouani, E. Couve, A. de Daruvar, P. Dehoux, E. Domann, G. Dominguez-Bernal, E. Duchaud, L. Durant, O. Dussurget, K. D. Entian, H. Fsihi, F. G. Portillo, P. Garrido, L. Gautier, W. Goebel, N. Gomez-Lopez, T. Hain, J. Hauf, D. Jackson, L. M. Jones, U. Kaerst, J. Kreft, M. Kuhn, F. Kunst, G. Kurapkat, E. Madueno, A. Maitournam, J. M. Vicente, E. Ng, H. Nedjari, G. Nordsiek, S. Novella, B. de Pablos, J. C. Perez-Diaz, R. Purcell, B. Remmel, M. Rose, T. Schlueter, N. Simoes, A. Tierrez, J. A. Vazquez-Boland, H. Voss, J. Wehland, and P. Cossart. 2001. Comparative genomics of Listeria species. Science 294:849-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ito, M., A. A. Guffanti, B. Oudega, and T. A. Krulwich. 1999. mrp, a multigene, multifunctional locus in Bacillus subtilis with roles in resistance to cholate and to Na+ and in pH homeostasis. J. Bacteriol. 181:2394-2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito, M., A. A. Guffanti, W. Wang, and T. A. Krulwich. 2000. Effects of nonpolar mutations in each of the seven Bacillus subtilis mrp genes suggest complex interactions among the gene products in support of Na+ and alkali but not cholate resistance. J. Bacteriol. 182:5663-5670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ji, Y., B. Zhang, S. F. Van Horn, P. Warren, G. Woodnutt, M. K. Burnham, and M. Rosenberg. 2001. Identification of critical staphylococcal genes using conditional phenotypes generated by antisense RNA. Science 293:2266-2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawano, M., R. Abuki, K. Igarashi, and Y. Kakinuma. 2000. Evidence for Na+ influx via the NtpJ protein of the KtrII K+ uptake system in Enterococcus hirae PG-2507-12. J. Bacteriol. 182:2507-2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kempf, B., and E. Bremer. 1995. OpuA, an osmotically regulated binding protein-dependent transport system for the osmoprotectant glycine betaine in Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 270:16701-16713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ko, R., and L. T. Smith. 1999. Identification of an ATP-driven, osmoregulated glycine betaine transport system in Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4040-4048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krulwich, T. A., M. Ito, R. Gilmour, and A. A. Guffanti. 1997. Mechanisms of cytoplasmic pH regulation in alkaliphilic strains of Bacillus. Extremophiles 1:163-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krulwich, T. A., M. Ito, R. Gilmour, D. B. Hicks, and A. A. Guffanti. 1998. Energetics of alkaliphilic Bacillus species: physiology and molecules. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 40:401-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krulwich, T. A., M. Ito, and A. A. Guffanti. 2001. The Na+-dependence of alkaliphily in Bacillus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1505:158-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lou, Y., and A. E. Yousef. 1997. Adaptation to sublethal environmental stresses protects Listeria monocytogenes against lethal preservation factors. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1252-1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mata, M. T., F. Baquero, and J. C. Perez-Diaz. 2000. A multidrug efflux transporter in Listeria monocytogenes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 187:185-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McClure, P. J., T. A. Roberts, and P. O. Oguru. 1989. Comparison of the effects of sodium chloride, pH and temperature on the growth of Listeria monocytogenes on gradient plates and liquid medium. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 9:95-99. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mengaud, J., S. Dramsi, E. Gouin, J. A. Vazquez-Boland, G. Milon, and P. Cossart. 1991. Pleiotropic control of Listeria monocytogenes virulence factors by a gene that is autoregulated. Mol. Microbiol. 5:2273-2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mengaud, J., C. Geoffroy, and P. Cossart. 1991. Identification of a new operon involved in Listeria monocytogenes virulence: its first gene encodes a protein homologous to bacterial metalloproteases. Infect. Immun. 59:1043-1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merino, D., H. Reglier-Poupet, P. Berche, and A. Charbit. 2002. A hypermutator phenotype attenuates the virulence of Listeria monocytogenes in a mouse model. Mol. Microbiol. 44:877-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murata, T., K. Takase, I. Yamato, K. Igarashi, and Y. Kakinuma. 1996. The ntpJ gene in the Enterococcus hirae ntp operon encodes a component of KtrII potassium transport system functionally independent of vacuolar Na+-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 271:10042-10047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okada, Y., S. Makino, T. Tobe, N. Okada, and S. Yamazaki. 2002. Cloning of rel from Listeria monocytogenes as an osmotolerance involvement gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1541-1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perkins, J. B., and P. J. Youngman. 1986. Construction and properties of Tn917-lac, a transposon derivative that mediates transcriptional gene fusions in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83:140-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rouquette, C., C. de Chastellier, S. Nair, and P. Berche. 1998. The ClpC ATPase of Listeria monocytogenes is a general stress protein required for virulence and promoting early bacterial escape from the phagosome of macrophages. Mol. Microbiol. 27:1235-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring, N.Y.

- 33.Sleator, R. D., C. G. Gahan, T. Abee, and C. Hill. 1999. Identification and disruption of BetL, a secondary glycine betaine transport system linked to the salt tolerance of Listeria monocytogenes LO28. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2078-2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sleator, R. D., C. G. Gahan, and C. Hill. 2001. Identification and disruption of the proBA locus in Listeria monocytogenes: role of proline biosynthesis in salt tolerance and murine infection. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2571-2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sleator, R. D., and C. Hill. 2002. Bacterial osmoadaptation: the role of osmolytes in bacterial stress and virulence. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 26:49-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takase, K., S. Kakinuma, I. Yamato, K. Konishi, K. Igarashi, and Y. Kakinuma. 1994. Sequencing and characterization of the ntp gene cluster for vacuolar-type Na+-translocating ATPase of Enterococcus hirae. J. Biol. Chem. 269:11037-11044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taormina, P. J., and L. R. Beuchat. 2001. Survival and heat resistance of Listeria monocytogenes after exposure to alkali and chlorine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2555-2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vasseur, C., N. Rigaud, M. Hébraud, and J. Labadie. 2001. Combined effects of NaCl, NaOH, and biocides (monolaurin or lauric acid) on inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes and Pseudomonas spp. J. Food Prot. 64:1442-1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang, W., A. A. Guffanti, Y. Wei, M. Ito, and T. A. Krulwich. 2000. Two types of Bacillus subtilis tetA(L) deletion strains reveal the physiological importance of TetA(L) in K+ acquisition as well as in Na+, alkali, and tetracycline resistance. J. Bacteriol. 182:2088-2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wemekamp-Kamphuis, H. H., J. A. Wouters, R. D. Sleator, C. G. Gahan, C. Hill, and T. Abee. 2002. Multiple deletions of the osmolyte transporters BetL, Gbu, and OpuC of Listeria monocytogenes affect virulence and growth at high osmolarity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:4710-4716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zwietering, M. H., J. T. de Koos, B. E. Hasenack, J. C. de Witt, and K. van't Riet. 1991. Modeling of bacterial growth as a function of temperature. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:1094-1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]