Abstract

Apoptosis is implicated in the progressive cell loss and fibrosis both at glomerular and tubulointerstitial level. In this study, we examined the potential mechanisms by which persistent proteinuria (protein-overload model) could induce apoptosis. After uninephrectomy (UNX), Wistar rats received daily injections of 0.5 g of bovine serum albumin (BSA)/100 g body weight or saline. Both at day 8 and day 28, rats receiving BSA had proteinuria and renal lesions characterized by tubular atrophy and/or dilation and mononuclear cell infiltration. In relation to control-UNX rats, renal cortex of nephritic rats showed an increment in AT2 mRNA (reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction) and protein (Western blot) expression. In both groups, AT2 receptor immunostaining was mainly localized in proximal tubular cells. Rats with persistent proteinuria showed a significantly increased number of terminal dUTP nick-end labeling positive apoptotic cells compared with UNX-controls, both in glomeruli and tubulointerstitium. Double staining for apoptosis and AT2 receptor showed that most terminal dUTP nick-end labeling positive cells were found in tubules expressing AT2 receptor. Using an antibody that recognizes the active form caspase-3, we observed an increment in caspase-3 activation in rats receiving BSA with respect to those receiving saline. Rats with persistent proteinuria showed a diminution in the phosphorylation of Bcl-2 with respect to UNX-controls both at day 8 and day 28. By contrast, no changes were observed either in the Bax or in the Bcl-2 protein levels. The administration of BSA to UNX rats induced a diminution in the phosphorylation of ERK with respect to UNX-control at all times studied. The changes observed in ERK activities took place without alterations of ERK1/2 protein levels. In summary, our data suggest that persistent proteinuria causes apoptosis in tubular cells through the activation of AT2 receptor, which can, in turn, inhibit MAP kinase (ERK1/2) activation and Bcl-2 phosphorylation.

Tubulointerstitial damage, regardless of its etiology, has been shown to be an important predictor of progressive renal failure.1 Although the mechanisms leading to end-stage renal failure are not completely elucidated, persistent proteinuria is considered an aggravating factor.1 Apoptosis (programmed cell death) is a gene-regulated process that is now recognized to play an important role in maintaining cell number homeostasis both in health and disease.2,3 Cell deletion by apoptosis has been implicated in the repairing process of several renal diseases, such as anti-Thy-1 antibody-induced nephritis and crescentic glomerulonephritis. However, unregulated excessive apoptosis can contribute to renal damage by depletion of glomerular and tubulointerstitial cells characteristic of progressive chronic nephropathies, including protein-overload nephropathy.4 Apoptosis is controlled in part by the Bcl-2 family proteins (Bcl-2, Bcl-x, Bax, and others).5 Apoptotic and anti-apoptotic members of the family can interact, and the overall effect on cell survival might depend on the balance between the activity of apoptotic (such as Bax and Bcl-xS) and anti-apoptotic (such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL) proteins. The biochemical basis for most of the morphological changes associated with apoptosis can be traced directly or indirectly to the actions of caspases, a family of intracellular cysteine proteases that function as effectors of programmed cell death.6 Initiator caspases (−2, −8, −9, −10), situated at the upstream of the caspase cascade, can activate the downstream executioner caspases (−3, −6, −7). Executioner caspases can, in turn, activate initiator caspases, thus propagating the apoptotic process.6 Caspase cellular targets include inactivation of protective proteins, such as Bcl-xL and Bcl-2, which can even yield proapoptotic fragments.6 In addition, the balance between the pro- and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein family members has been found to control caspase-3 activity.7

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) has been implicated in the development of renal damage. In humans and experimental models, RAS blockade with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin type 1 receptor (AT1) antagonists has been demonstrated to ameliorate organ damage, even in situations of normal blood pressure.8–11 Angiotensin II (Ang II), the main peptide of the RAS, exerts its biological actions via the activation of two major classes of specific cellular receptors, designated AT1 and AT2. Most effects of Ang II, such as cell proliferation, fibrosis, and the inflammatory response are mediated by AT1 receptors.9,12 Much less is known about the physiological role of AT2 receptors. Recent evidence suggests involvement of AT2 receptors in development, cell differentiation, apoptosis, and inflammation.12,13

Throughout the last years, several studies have been focused on AT2 receptor-mediated apoptosis.13 Proapoptotic effects of AT2 receptor have been noted in different cell types, including fibroblasts (R3T3), vascular smooth muscle cells, and proximal tubular cells (LLC-PK1). It has been demonstrated that the AT2 receptor activates a tyrosine phosphatase that induces the inactivation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1 and ERK2),14 resulting in Bcl-2 dephosphorylation, which may contribute to apoptosis.14,15 Little is known, however, about the AT2 receptor-signaling pathway in vivo.

Protein-overload proteinuria is an experimental model characterized by early and intense proteinuria associated to tubulointerstitial lesions, which has proven to be a valuable model to investigate the relationship between proteinuria and renal damage.10,16 We have previously demonstrated that bovine serum albumin (BSA)-overloaded animals showed important morphological renal lesions, characterized by tubular atrophy and/or vacuolization and protein casts within proximal and distal tubules, coinciding with an up-regulation of the RAS proteins located in the proximal renal tubules.17 However, in that study the expression of the AT2 receptor was not investigated. Since Thomas and colleagues4 at have recently reported that protein overload proteinuria in rats induces tubular cell apoptosis, in the current study we extend these findings by investigating the expression of pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins and their relationship with the activation of the AT2 receptor. In addition, to elucidate the potential intracellular mechanisms controlling the AT2-mediated apoptosis, we examined the expression of caspase-3 as well as that of the ERK family during tubulointerstitial damage progression.

Materials and Methods

Animal Model

Female Wistar rats (150 to 200 g) were fed standard rat chow ad libitum and given free access to water. The animals underwent unilateral left nephrectomy 5 days before the initiation of the study. Since day 0, uninephrectomized (UNX) rats received intraperitoneal and daily injections of BSA (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) (0.5 g BSA/100 g body weight) or saline.10,17 Periodically, animals were housed in metabolic cages and 24-hour urine was collected for protein measurement by the sulfosalicylic acid method.18 Animals were killed in groups (n = 7 per group) at days 8 and 28 after the initiation of saline or BSA injections based on previous experiments in which proteinuria peaked on day 8 and persisted up to day 28. Rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (5 mg/100 g body wt), and kidneys were perfused with cold sodium saline and removed.

Renal Histopathological Studies

For light microscopy, paraffin-embedded sections (4 μm thick) were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and Masson’s trichrome. For each animal, glomerular damage (mesangial cell proliferation and matrix expansion) and tubulointerstitial injury (tubular dilation and/or atrophy, interstitial fibrosis, and inflammatory cell infiltrate) were graded from 0 to 3 by a semiquantitative score: 0, no changes; 1, focal changes that involve 33% of the sample; 2, changes affecting >33 to 66%; 3, lesions affecting >66%. Two independent observers performed the semiquantification of morphological lesions in a blinded manner.

RNA Extraction, Reverse Transcription, and Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

Pieces of renal cortex were homogenized and total RNA was obtained by the acid guanidinium-phenol-chloroform method.19 Isolated RNA was reverse-transcribed and then amplified with a commercial kit (Access RT-PCR System; Promega, Madison, WI), using specific primers of rat AT2 (anti-sense: 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGG-3′, sense: 5′-AATTAGGTCACACTATAGGAT-3′; fragment 498-bp length). We performed reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as internal control. The optimum number of amplification cycles used for semiquantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR (37 and 20 cycles, respectively) was chosen based on previous experiments that establish the exponential range of the reaction (data not shown). Then, samples were size-fractionated with 4% acrylamide-bisacrylamide gels. The gels were dried and exposed to X-OMAT AR films (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). Autoradiograms were analyzed using scanning densitometry (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). Results were expressed as arbitrary densitometric units.

Western Blot and Immunoprecipitation

Renal cortex samples were homogenized in 1 ml of lysis buffer (50 mmol/L Hepes, pH 7.5, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 mmol/L EGTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mmol/L phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride, 0.1 mmol/L sodium orthovanadate) at 4°C. Soluble lysates (60 to 80 μg) were loaded in each lane and then separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline/0.5% Tween-20 (v/v) for 1 hour, washed with Tris-buffered saline/Tween-20, and incubated with the following antibodies: rabbit polyclonal anti-AT2 (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), rabbit polyclonal anti-caspase-3 (1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit polyclonal cleaved caspase-3 (Asp175) (1:1000; New England Biolabs Inc., Beverly, MA), rabbit polyclonal anti-Bax, (1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit polyclonal anti-Bcl-2 (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit anti-phospho ERK1/2 (Thr/Tyr) (1:500, New England Biolabs Inc.), and goat polyclonal anti-ERK2 (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Blots were washed with Tris-buffered saline/Tween-20 and subsequently incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-goat IgG (1:1500; Amersham, Aylesbury, UK). After washing with Tris-buffered saline/Tween-20 the blots were developed with the enhanced chemiluminescence method (Amersham). The intensity of the identified bands was quantified by densitometry (Molecular Dynamics). Results were expressed as arbitrary densitometric units.

For immunoprecipitations, 200 μg of homogenized renal cortex were incubated overnight at 4°C with either goat polyclonal anti-ERK2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or rabbit polyclonal anti-Bcl-2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Immune complexes were absorbed to protein A-Sepharose and washed twice with lysis buffer. Western blot analysis was subsequently performed with mouse monoclonal anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (1:500, Transduction Laboratories, Newington, NH) as first antibody. Incubation with the secondary antibody and detection were performed as described above.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunolocalization of AT2 receptor was performed with a polyclonal anti-rat AT2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in paraffin-embedded renal tissues. After dewaxed and hydrated, endogenous alkaline phosphatase was blocked in 5 mmol/L levamisole and sections were subsequently incubated with blocking serum for 30 minutes at room temperature to reduce nonspecific background staining and with a polyclonal anti-rat AT2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) overnight at 4°C. After being washed, the sections were incubated with biotinylated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Amersham) and processed using alkaline phosphatase-streptavidin-biotin immunoperoxidase method (ABComplex/AP; DAKO A/S, Glostrup, Denmark) and developed with Fast Red TR/naphthol AS-MX solution (DAKO A/S). The tissue sections were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin (Sigma, Madrid, Spain). Negative controls for specific labeling were performed in parallel by replacing the primary antibody with a nonimmune normal rabbit serum. Renal cortex sections were quantitatively examined using the computer-assisted image analysis software (Optimas 6.5; Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD) and digitized images. For each renal cortex section, AT2 receptor expression was analyzed in four nonoverlapping random fields viewed at ×200 magnification and expressed as the percentage of area occupied by an AT2 staining threshold that was arbitrarily considered as positive. An independent observer evaluated the immunostaining results in a blinded manner.

In Situ Detection of Apoptosis

Apoptosis was detected by terminal dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) using a commercial kit (Frag EL DNA Fragmentation Detection kit; Oncogene Research Products, Cambridge, MA). Biotinylated-dUTP-labeled DNA was detected and visualized using peroxidase-streptavidin conjugated with diaminobenzidine (Sigma) as the chromogen. The number of TUNEL-positive cells was quantified in a blinded manner with computer-assisted image analysis software (Optimas 6.5, Media Cybernetics) and digitized images. The specificity of the technique was evaluated with positive and negative controls. In positive controls, generated by pretreating slides with 1 μg/μl of DNase I before labeling reaction, nearly all of the cells stained, although they showed normal shape without cytoplasmic condensation. No staining was observed in negative controls that were incubated in labeling buffer without TdT.

For each renal cortex section, glomerular cells undergoing apoptosis were calculated by counting at least 10 glomeruli per biopsy and expressed as the mean number ± SEM per glomeruli. In tubules, apoptotic cells were calculated by counting all positive apoptotic tubular cells in four to six nonoverlapping random fields viewed at ×200 magnification and expressed as the mean number ± SEM per field. Staining of a size between 5 and 25 pixels (that is, the size of an apoptotic nucleus) was counted as a single particle. Only intense brown-stained nuclei, including pyknotic nuclei with apoptotic bodies that stained positive, were considered as TUNEL-positive staining.

Double Immunostaining for TUNEL and AT2

Double-immunohistochemical staining was performed in paraffin-embedded renal tissue. Sections were dewaxed, rehydrated by descending ethanol concentrations, and processed with the FragEl DNA Fragmentation Detection kit (Oncogene Research Products). Afterward, sections were processed for AT2 immunostaining as described above. The tissue sections were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin (Sigma). Negative control sections were performed in parallel for specific labeling by replacing the primary antibody with nonimmune normal rabbit serum and with the omission of TdT enzyme.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Comparisons between groups were made using the unpaired Student’s t-test or the Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric analysis of variance test when appropriate. Differences were taken as significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Development of Renal Injury

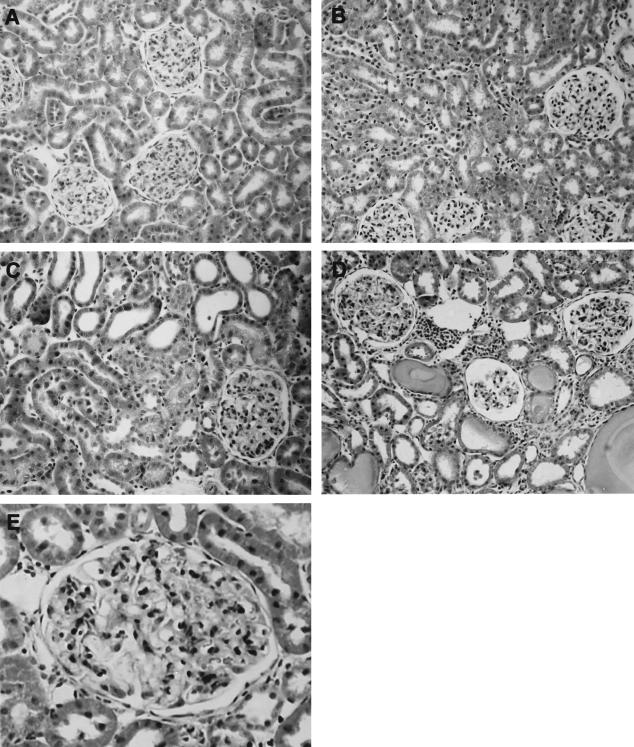

In BSA-overloaded rats, proteinuria was significantly increased at day 8, reaching a plateau between days 8 and 28 (day 8: UNX-control, 3.0 ± 0.4 and BSA-overloaded, 544 ± 105; day 28: UNX-control, 7.0 ± 0.3 and BSA-overloaded, 460 ± 65 mg/24 hours; n = 7, P < 0.05). In UNX-control rats, no clear evidence of tubulointerstitial injury was seen, although mild glomerular proliferative changes could be detected both at days 8 and 28 (Figure 1, A and B). However, animals with persistent proteinuria showed interstitial infiltration of mononuclear cells, tubular atrophy and/or vacuolization, and protein casts within distal and proximal tubules both on days 8 and 28 (Figure 1, C and D). BSA-overloaded rats also showed mesangial expansion (Figure 1; C to E). The semiquantitation of the morphological lesions demonstrated a significant increase in renal injury in BSA-overloaded rats with respect to UNX-control animals (day 8: UNX-control, 0.2 ± 0.1 and BSA-overloaded, 1.3 ± 0.4; day 28: UNX-control, 0.3.0 ± 0.2 and BSA-overloaded, 2.57 ± 0.75; n = 7, P < 0.05 versus UNX-control at the same time).

Figure 1.

Histological analysis of renal tissue from UNX-control (A, B) and BSA-overloaded rats (C–E). The sections were stained with Masson’s trichrome. No significant tubulointerstitial lesions were observed in animals receiving saline (UNX-controls) either at day 8 (A) or day 28 (B). By contrast, animals receiving 0.5 g/100 g body weight BSA during 8 (C) and 28 (D) days showed interstitial infiltrate, tubular atrophy and/or vacuolization, and protein casts within the tubules. E: Detail of mesangial expansion observed in BSA-overloaded rats at day 28. Photographs are representative of seven animals per group. Original magnifications: ×200 (A–D); ×400 (E).

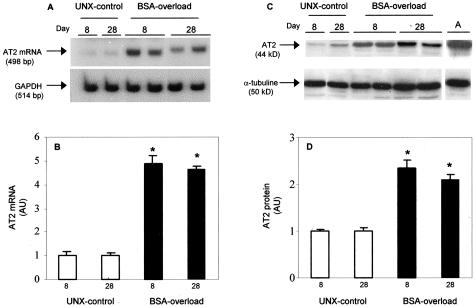

AT2 Receptor Expression (mRNA and Protein) in Renal Cortex from UNX-Control and BSA-Overloaded Rats

By reverse transcriptase-PCR, we could not detect the mRNA for AT2 receptor in renal cortex from Wistar-Kyoto rats with two kidneys, in agreement with previous data.20,21 However, a band of the predicted size (498 bp) of the AT2 receptor mRNA was found in renal cortex from UNX-control and BSA-overloaded rats both at days 8 and 28 (Figure 2). Figure 2A shows representative examples of AT2 receptor PCR products from the different groups. Densitometric analysis of the bands demonstrated a significant increment in the AT2 receptor expression in BSA-overloaded rats compared to UNX-control at all times studied (Figure 2B). By Western blot analysis, a significant increase in AT2 receptor protein expression was observed in the renal cortex from BSA-overloaded rats compared to UNX-control rats (Figure 2, C and D). Adrenal gland, which expresses abundant AT2 receptor protein,20 was used as positive control.

Figure 2.

Expression of AT2 receptor mRNA (A, B) and protein (C, D) in renal cortex of UNX-control and BSA-overloaded rats. Autoradiography showing AT2 receptor mRNA expression (A) and protein production (C) of representative animals from each group. B and D: Densitometric analysis of AT2 receptor bands from rats receiving saline (UNX-control, □) and BSA-overloaded rats (▪). Results are expressed as fold-increase compared with UNX-control at day 8. Individual bar values are mean ± SEM of each group, n = 7 animals per group. *, P < 0.001 with respect to rats receiving saline (UNX-control) at same time. Adrenal gland extracts (A) were used as a positive control. AU, arbitrary units.

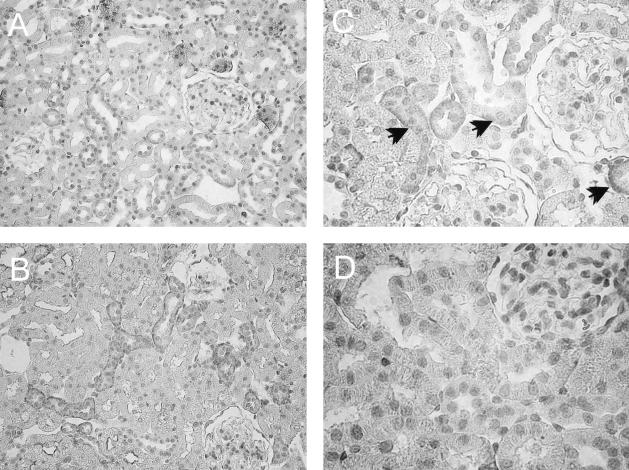

Localization of AT2 Receptor in Renal Cortex from BSA-Overloaded Rats

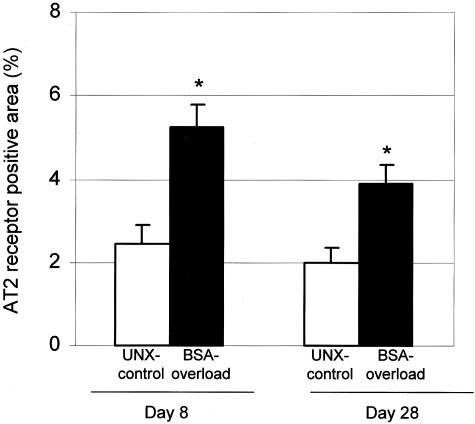

To localize the AT2 receptor protein in the rat kidney, immunohistochemistry was performed on paraffin-embedded kidney sections from UNX-control and BSA-overloaded animals. As shown in Figure 3, in both groups of rats, AT2 receptor protein was localized in proximal and distal tubules, mainly in the basolateral membranes of the tubules. No appreciable immunostaining of AT2 receptor was observed in glomeruli. Negative controls of the immunohistochemistry showing the specificity of the AT2 receptor antibody is shown in Figure 3D. Quantitation of AT2 receptor staining by computer-based image analysis revealed a significant increase in expression of AT2 receptor in BSA-overloaded rats with respect to UNX-control rats (Figure 4). This AT2 expression was higher, but not significantly, at day 8 than at day 28 (Figure 4), corroborating the results obtained by Western blot.

Figure 3.

Localization of AT2 receptor in paraffin-embedded kidney sections from UNX-control (A) and BSA-overloaded rats (B) at day 8. In both groups of rats, the AT2 receptor staining was localized in proximal and distal tubules. Neither UNX-control nor BSA-overloaded rats showed appreciable immunostaining of AT2 receptor in glomeruli. C: Detail of the AT2 receptor staining localized mainly in basolateral membranes (arrows). D: No staining was observed in renal sections from BSA-overloaded rats at day 8 incubated with a nonimmune normal rabbit serum. Original magnifications: ×200 (A, B); ×400 (C, D).

Figure 4.

Percentage of renal cortex occupied by AT2 receptor immunostaining. AT2 receptor immunostaining was quantified as described in Materials and Methods. Results as mean ± SEM, n = 7 animals per group. *, P < 0.05 with respect to UNX-control at same time.

Measurement of Apoptotic Cells

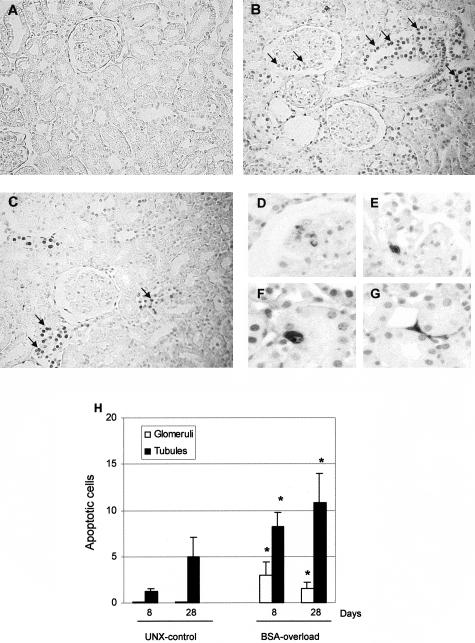

Measured by TUNEL technique, UNX-control rats showed occasional TUNEL-positive staining cells (Figure 5A). However, the administration of BSA to UNX rats induced an increment of cells showing an intense brown TUNEL-stained nuclei mainly in tubules but also in the glomeruli (Figure 5; B to G). In our experimental conditions, no staining is detected either in normal Wistar rats or in the negative control sections using buffer lacking TdT as previously reported.22 Quantitation of TUNEL-stained apoptotic cells demonstrated a significantly increased number of apoptotic cells mainly in tubules and, to a lesser extent, in glomeruli from BSA-overloaded animals with respect to UNX-control rats at all times studied (Figure 5H).

Figure 5.

Detection of apoptotic cells by in situ DNA TUNEL in renal tissue from UNX-control and BSA-overloaded rats. TUNEL staining was performed in kidney sections from UNX-control (A) and BSA-overloaded rats at day 8 (B) and day 28 (C). A representative area from each section is shown. An increment in apoptotic cells (arrows) was observed in renal sections from BSA-overloaded animals in comparison with those receiving saline (UNX-control). D: At day 8, BSA-overloaded rats only showed condensed pyknotic nuclei with apoptotic bodies in some glomeruli. At day 28, cells with condensed pyknotic nuclei with apoptotic bodies were mainly localized in glomeruli (E), tubules (F), and interstitium (G). H: Quantitation of TUNEL-positive cells in glomeruli and tubules. Data represent mean ± SEM, n = 7 animals per group. *, P < 0.05 with respect to UNX-control at same time.

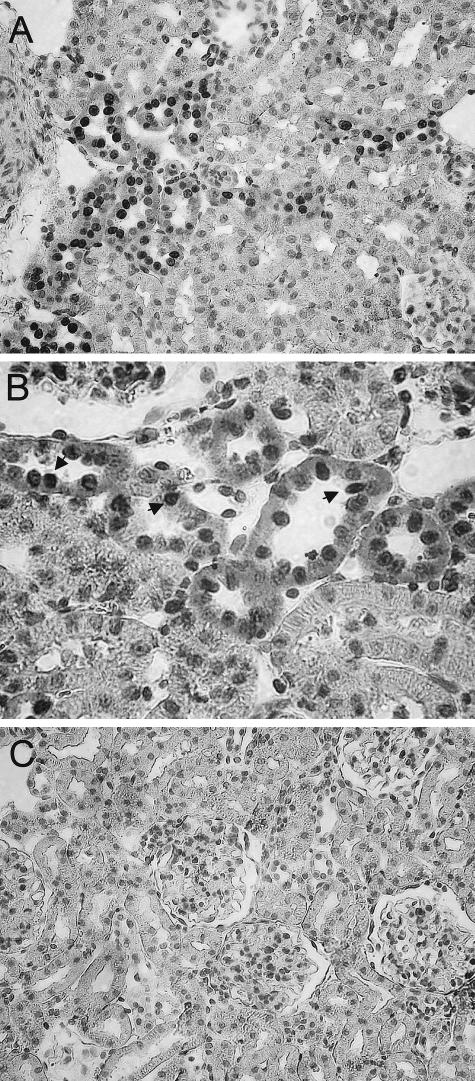

Co-Localization of Apoptotic Cells and AT2 Receptor

Double staining for apoptosis and AT2 receptor showed that most of TUNEL-positive cells were found in tubules expressing AT2 receptor (Figure 6). No staining was observed in renal sections incubated with a nonimmune normal rabbit serum and with the omission of TdT enzyme, demonstrating the specificity of labelings (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Co-localization of apoptosis and AT2 receptor in renal sections of BSA-overloaded rats at day 8. Most of the TUNEL-positive cells (brown) (arrows) were found in tubules expressing AT2 receptor (red) (A, B). C: No staining was observed in renal sections incubated with a nonimmune normal rabbit serum and with the omission of TdT enzyme. Original magnifications: ×200 (A, C); ×400 (B).

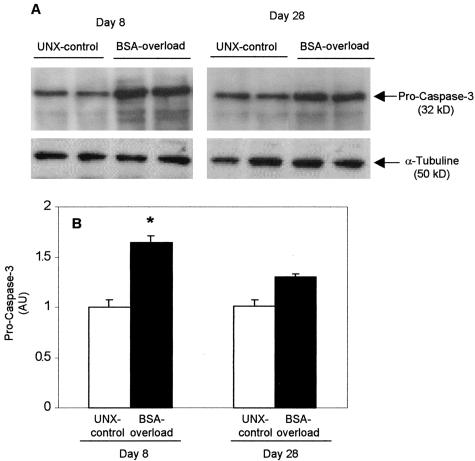

Caspase-3 Expression in Renal Cortex from UNX-Control and BSA-Overloaded Rats

Among executioner caspases, caspase-3 is the best studied and represents the central molecule situated at the crossroad of all known apoptotic pathways.6 Western blot analysis and quantification of procaspase-3 (32 kd) showed a transient increase of the caspase-3 precursor in the renal cortex from BSA-overloaded rats as compared with UNX-controls at day 8 (Figure 7). At day 28, the procaspase-3 expression was slightly, but not significantly, higher in BSA-overloaded rats than in UNX-controls.

Figure 7.

Procaspase-3 expression is increased in renal cortex from BSA-overloaded rats. A: Western blot results showing two representative animals from each group. B: Densitometric results expressed as fold-increase compared to rats receiving saline (UNX-control) at day 8. Individual bar values are mean ± SEM of each group, n = 7 animals per group. *, P < 0.05 with respect to UNX-control at same time. AU, arbitrary units.

All known caspases require proteolytical cleavage to liberate one large and one small subunit that heterodimerize to form the active enzyme.23 Western blots using an antibody to the large fragment of activated caspase-3 (17 to 20 kd) identified two proteins of 17 and 19 kd in BSA-overloaded rats, corresponding to large fragment and prodomain + large fragment, respectively (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Caspase-3 active subunit (17 to 20 kd) expression is increased in renal cortex from BSA-overloaded rats. Western blot showing two representative animals from each group. Two proteins of Mr 17 kd (large subunit) and 19 kd (prodomain + large subunit) are identified both in UNX-control and BSA-overloaded rats.

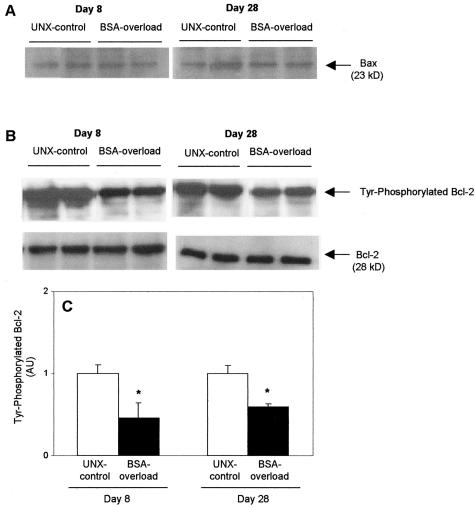

Expression of Bax and Bcl-2 Proteins in Renal Cortex from UNX-Control and BSA-Overloaded Rats

By Western blot, no changes were observed either in the Bax or in the Bcl-2 protein levels in BSA-overloaded rats with respect to UNX-controls at all time studied (Figure 9). Because phosphorylation of Bcl-2 is essential for its physiological role,14 renal cortex lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Bcl-2 antibody and analyzed by Western blot with an anti-phosphotyrosine antibody. As can be seen in Figure 9, BSA-overloaded rats showed a diminution in the phosphorylation of Bcl-2 with respect to UNX-controls both at days 8 and 28.

Figure 9.

Expression of Bax and Bel-2 proteins from UNX-control and BSA-overloaded rats. A: BSA overload did not alter the protein expression of Bax. B: However, BSA-overloaded rats showed a diminution in the phosphorylation of Bcl-2 with respect to those receiving saline (UNX-controls) both at day 8 and day 28 (top). Reprobing of immunoblots with an anti-Bcl-2 antibody demonstrated no changes in total Bcl-2 protein production. Autoradiographies are representative of seven animals per group (bottom). C: Densitometric analysis of phosphorylated Bcl-2 bands. Data are expressed as fold-increase with respect to rats receiving saline and represent mean ± SEM of each group, n = 7 animals per group. *, P < 0.05 with respect to UNX-control at same time. AU, arbitrary units.

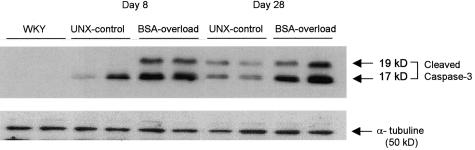

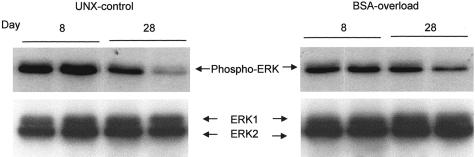

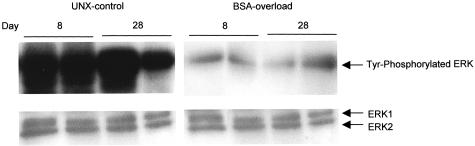

MAP Kinase (ERK1/2) Expression in Renal Cortex from UNX-Control and BSA-Overloaded Rats

We evaluated the in vivo activity of MAP kinases in the renal cortex of UNX-control and BSA-overloaded rats, both at days 8 and 28. As shown in Figure 10, immunoblot using an anti-phospho-ERK1/2 antibody, which identifies only active ERK forms phosphorylated within the regulatory sequence, demonstrated that the administration of BSA to UNX rats induced a diminution in the phosphorylation of ERK with respect to UNX-control both at day 8 and day 28. Reprobing of immunoblots with an anti-total ERK antibody, two bands with a molecular weight consistent with that of ERK1 (44 kd) and ERK2 (42 kd) were identified, without differences in the expression of both proteins between rats receiving BSA or saline (Figure 10, bottom). Therefore, the observed changes in ERK activities took place without changes in ERK1/2 proteins levels. These results were confirmed when renal cortex samples were immunoprecipitated with an anti-total ERK antibody and Western blot probed with an anti-phosphotyrosine antibody. As shown in Figure 11, BSA-overloaded rats showed a significantly less phosphorylation of ERK1/2 proteins compared with UNX-control rats both at day 8 and day 28.

Figure 10.

MAP kinase (ERK1/ERK2) expression in renal cortex from UNX-control and BSA-overloaded rats. Renal cortex lysates were examined by an anti-phospho-ERK1/2 antibody that identifies only ERK forms phosphorylated within the regulatory sequence. Confirmation of equal loading was performed by reprobing of immunoblots with an anti-total ERK antibody. Autoradiographies show two representative animals from each group.

Figure 11.

Phosphorylation of MAP kinases (ERK1/ERK2) detected by immunoprecipitation in renal cortex from UNX-control and BSA-overloaded rats. To test the specificity of the anti-phospho-ERK1/2 antibody, renal cortex lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-total ERK antibody and immunoblotted with an anti-tyrosine antibody. This autoradiography is representative of two immunoprecipitation experiments.

Discussion

AT2 receptors have been involved in anti-proliferation and apoptosis.13 The ability of Ang II to activate tyrosine kinases, including MAP kinases (ERK1/2), in different cell types is a well-recognized fact.13 Recent in vitro studies have demonstrated that AT2 receptor stimulation inhibits MAP kinase activation, resulting in the inactivation of Bcl-2 and the induction of apoptosis.13–15 However, most of these findings on the signaling pathway associated to AT2 activation are based on studies in cultured cells. In the present report we demonstrate that this cellular signaling pathway could also occur in vivo. Specially, we provide evidence that protein overload-induced apoptosis is associated with AT2 activity, whereby the activation of AT2 receptor results in 1) dephosphorylation and subsequently inactivation of ERK1/2, 2) a diminution in the phosphorylation of Bcl-2, and 3) activation of caspase-3, the executor caspase.

Consistent with previous studies indicating a low abundance of the AT2 mRNA in adult kidney,20,21 we could not detect, by reverse transcriptase-PCR, the mRNA for AT2 receptor in renal cortex from Wistar-Kyoto rats with two kidneys. However, UNX rats (both controls and BSA-overloaded) expressed AT2 receptor mRNA and protein in the renal cortex, being the AT2 expression higher in those receiving BSA. In both groups, AT2 receptor immunostaining was mainly localized in proximal tubular cells in a patchy distribution. Coinciding with this finding, in rats with persistent proteinuria the number of apoptotic cells (quantified by image analysis of TUNEL technique) was increased on day 8 and remained unchanged up to the end of the study on day 28, compared to UNX-control. A similar distribution of AT2 receptor and TUNEL-positive cells was found by double-staining studies in kidney from rats with overload nephropathy, suggesting that AT2 receptor may be involved in the proteinuria-induced apoptosis. In vitro, several studies have demonstrated that the activation of AT2 receptor induces apoptosis in different cell types expressing abundant AT2 receptor, including proximal tubular cells.13–15,24 In vivo, other studies have also demonstrated the presence of AT2 receptor protein in the adult rat kidney,21,22 although they did not address its potential role in renal function.

The central components of the apoptotic machinery are caspases, of which caspase-3 is the best functionally correlated with the phenotype of apoptosis.6 We found that caspase-3 precursor and active protein was increased in BSA-overloaded rats with respect to UNX-control rats, suggesting the execution of the cell death program. In vitro, the stimulation of AT2 receptor has been reported to result in the activation of caspase-3.25,26 In vivo, caspases, especially caspase-3, may serve as mediators of renal cell apoptosis observed in different models of renal damage.27–30 Although inhibition of the caspase family has been demonstrated to prevent cell death in a number of models of neurodegenerative cell death, both in vivo and in vitro,31 whether caspase blockade would have protective effects on renal function in overload nephropathy is still speculative.

As susceptibility to apoptosis is directly linked to relative levels and interactions among pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins, we studied the expression of Bax and Bcl-2 proteins. In animals with persistent proteinuria, no changes were noted either in Bax or Bcl-2 protein expression. Because it has been reported that phosphorylation of Bcl-2 protein is important for the regulation of its function,14 we investigated the level of phosphorylated Bcl-2. We demonstrate that the administration of BSA to UNX rats decreases the phosphorylation of Bcl-2 compared to those receiving saline at all times studied. The relationship observed between phosphorylated Bcl-2 protein and renal apoptosis and lesions suggest that, in the model of renal injury caused by intense proteinuria, this regulation might be of greater importance in the renal cell loss than the increment in Bax. In agreement with our results, Bcl-2 phosphorylation has been described to be required for its anti-apoptotic function.14,15 Some authors have reported that Bcl-2 phosphorylation may somehow enhance and/or stabilize the interaction between Bcl-2 and Bax.32 In endothelial cells, it has been reported that phosphorylation of Bcl-2 might prevent its degradation, making the cells more resistant to stimulus-induced apoptosis.33 In vitro, AT2 activation can elicit Bcl-2 dephosphorylation, which in turn, promotes apoptosis.15

MAP kinases play a pivotal role in the regulation of important cellular functions including apoptosis.34 Ang II can activate multiple protein kinases, including tyrosine kinases important to the MAP kinase pathway.13 Classically, the activation of these pathways has been related to the mitogenic actions of Ang II. Several in vitro studies have reported ERK inhibition by AT2 receptor activation as a key pathway of AT2 receptor signaling.13,15 However, its mode of activation in vivo is unknown. In the present study, we demonstrate dephosphorylation and, therefore, inactivation of ERK1/2 in renal cortex from rats with persistent proteinuria coinciding with a diminution in the phosphorylated form of Bcl-2 and an increment in the apoptotic rate. Moreover, the ERK inhibition was not associated with changes in total protein level of ERK. In vitro studies have shown that although the majority of ERK1/2 is cytoplasmic, there is a population of ERK1/2 that localize with Bcl-2 in the mitochondria and, therefore, can directly phosphorylate Bcl-2.33 It has been reported that inhibition of ERK1/2 activities caused a down-regulation of anti-apoptotic genes Bcl-2, Mcl-1, and Bcl-xL, and an increment of several caspase activities.35 Interestingly, reactive oxygen species have been shown to play a key role in tumor necrosis factor-α-triggered ERK1/2 deactivation because dephosphorylation/inactivation of ERK1/2 can be inhibited in the presence of several antioxidants.36 In this sense, we have previously reported that overload proteinuria causes the activation of nuclear factor-κB, a redox-sensitive transcription factor, in tubular epithelial cells both in vivo and in vitro.10

As commented below, previous studies from our group have demonstrated that RAS is activated in tubular cells in animals with intense and persistent proteinuria.17 In addition, we have noted that renal lesions displayed by these animals are, to a large extent, mediated by Ang II.10,11 Therefore, the current findings suggest that increased AT2 receptor-induced apoptosis could be implicated in the renal lesions displayed by rats with persistent proteinuria in a conventional model of ligand-receptor regulation. However, recently Miura and colleagues37 have proposed that overexpression of the AT2 receptor itself is a signal for apoptosis that does not require Ang II. Further studies are needed to answer this question in the model of overload nephropathy.

In summary, our data show that persistent proteinuria increases apoptosis coinciding with an up-regulation of AT2 receptor in proximal tubular cells, and the inhibition of MAP kinases (ERK1/2) activation and Bcl-2 phosphorylation. These data are the first evidence on the signaling pathway associated to AT2 activation in vivo and provide new insights into the pathogenesis of renal damage induced by persistent proteinuria.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Jesús Egido, M.D., Renal and Vascular Laboratory, Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Avda Reyes Católicos 2, 28040 Madrid, Spain. E-mail: jegido@fjd.es.

Supported partially by grants from the Comunidad de Madrid (08.4/0002/2000, 08.4/0021.1/2003), the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (01/3151, 01/0199, and 03/0584), the Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología (SAF 2001/0717), EU Project Chronic Renal Disease (QLG1-CT-2002-01215), and Instituto de Investigaciones Nefrológicas “Reina Sofía.”

A.L. and J.G.-D. are fellows from Fundación Conchita Rábago and the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (01/0199), respectively.

N.T. and D.G.-G. contributed equally to this article.

References

- Remuzzi G, Ruggenenti P, Benigni A. Understanding the nature of renal disease progression. Kidney Int. 1997;51:2–15. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz A, Lorz C, Catalán MP, Justo P, Egido J. Role and regulation of apoptotic cell death in the kidney. Y2K update. Front Biosci. 2000;5:D735–D749. doi: 10.2741/ortiz. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz A, Lorz C, Justo P, Catalán MP, Egido J. Contribution of apoptotic cell death to renal injury. J Cell Mol Med. 2001;5:18–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2001.tb00135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas ME, Brunskill NJ, Harris KPG, Bailey E, Pringle JH, Furness PN, Walls J. Proteinuria induces tubular cell turnover: a potential mechanism for tubular atrophy. Kidney Int. 1999;55:890–898. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.055003890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cory S, Adams JM. The Bcl2 family: regulators of the cellular life-or-death switch. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:647–656. doi: 10.1038/nrc883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budihardjo I, Oliver H, Lutter M, Luo X, Wang X. Biochemical pathways of caspase activation during apoptosis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:269–290. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosulich SC, Savory PJ, Clarke PR. Bcl-2 regulates amplification of caspase activation by cytochrome c. Curr Biol. 1999;9:147–150. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egido J. Vasoactive hormones and renal. Kidney Int. 1996;49:578–597. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnier M. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers. Circulation. 2001;103:904–912. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.6.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Garre D, Largo R, Tejera N, Fortés J, Manzarbeitia F, Egido J. Activation of NF-κB in tubular epithelial cells of rats with intense proteinuria. Role of angiotensin II and endothelin-1. Hypertension. 2001;37:1171–1178. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.4.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Lopez-Franco O, Gómez-Garre D, Tejera N, Gómez-Guerrero C, Sugaya T, Bernal R, Blanco J, Ortega L, Egido J. Renal tubulointerstitial damage caused by persistent proteinuria is attenuated in AT1-deficient mice: role of endothelin-1. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1895–1904. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63036-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Ortega M, Lorenzo O, Suzuki Y, Rupérez M, Egido J. Proinflammatory actions of angiotensins. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2001;10:321–329. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200105000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Gasparo M, Siragy HM. The AT2 receptor: fact, fancy and fantasy. Regul Pept. 1999;81:11–24. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(99)00023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Deng X, Carr B, May WS. Bcl-2 phosphorylation required for anti-apoptosis function. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26865–26870. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.18.11671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi M, Hayashida W, Kambe T, Yamada T, Dzau VJ. Angiotensin type 2 receptor dephosphorylates Bcl-2 by activating mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 and induces apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19022–19026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.19022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy AA. Interstitial nephritis induced by protein-overload proteinuria. Am J Pathol. 1989;135:719–733. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Largo R, Gómez-Garre D, Soto K, Marrón B, Blanco J, Gazapo MR, Plaza JJ, Egido J. Angiotensin converting enzyme is upregulated in the proximal tubules of rats with intense proteinuria. Hypertension. 1999;33:732–739. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.2.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyure WL. Comparison of several methods for semiquantitative determination of urinary protein. Clin Chem. 1977;23:876–879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanmugam S, Llorens-Cortes C, Clauser E, Corvol P, Gasc JM. Expression of angiotensin II AT2 receptor mRNA during development of rat kidney and adrenal gland. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:F922–F930. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1995.268.5.F922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehbi GJ, Zimpelmann J, Carey RM, Levine DZ, Burns KD. Early streptozotocin-diabetes mellitus downregulates rat kidney AT2 receptors. Am J Physiol. 2001;280:F254–F265. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.2.F254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto K, Gómez-Garre D, Largo R, Gallego J, Tejera N, Catalán MP, Ortiz A, Plaza JJ, Alonso C, Egido J. Tight blood pressure control decreases apoptosis during renal damage. Kidney Int. 2004;65:811–822. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes-Alnemri T, Litwack G, Alnemri ES. CPP32, a novel human apoptotic protein with homology to Caenorhabditis elegans cell death protein Ced-3 and mammalian interleukin-1 beta-converting enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:30761–30764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimpelmann J, Burns KD. Angiotensin II AT2 receptors inhibit growth responses in proximal tubule cells. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:F300–F308. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.281.2.F300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimmeler S, Rippmann V, Weiland U, Haendeler J, Zeiher AM. Angiotensin II induces apoptosis of human endothelial cells. Protective effect of nitric oxide. Circ Res. 1997;81:970–976. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.6.970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtonen JY, Horiuchi M, Daviet L, Akishita M, Dzau VJ. Activation of the de novo biosynthesis of sphingolipids mediates angiotensin II type 2 receptor-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16901–16906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.16901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Johnson TS, Thomas GL, Watson PF, Wagner B, El Nahas AM. Apoptosis and caspase-3 in experimental anti-glomerular basement membrane nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:485–495. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V123485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong LD, Choi Y-J, Tsao CC, Ayala G, Sheikh-Hamad D, Nassar G, Suki WN. Renal cell apoptosis in chronic obstructive uropathy: the roles of caspases. Kidney Int. 2001;60:924–934. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.060003924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz A, Lorz C, Catalán M, Ortiz A, Coca S, Egido J. Cyclosporine A induces apoptosis in murine tubular epithelial cells: role of caspases. Kidney Int. 1998;68:S25–S29. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.06808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AB, Kaushal V, Megyesi JK, Shah SV, Kaushal GP. Cloning and expression of rat caspase-6 and its localization in renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Kidney Int. 2002;62:106–115. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilsland J, Harper S. Caspases and neuroprotection. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2002;3:1745–1752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X, Ruvolo P, Carr B, May WS., Jr Survival function of ERK1/2 as IL-3 activated, staurosporine-resistant Bcl2 kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1578–1583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimmeler S, Breitschopf K, Haendeler J, Zeiher AM. Dephosphorylation targets Bcl-2 for ubiquitin-dependent degradation: a link between the apoptosome and the proteasome and the pathway. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1815–1822. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.11.1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MJ, Cobb MH. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:180–186. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher MJ, Morisset J, Vachon PH, Reed JC, Laine J, Rivard N. MEK/ERK signaling pathway regulates the expression of Bcl-2, Bcl-X(L), and Mcl-1 and promotes survival of human pancreatic cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 2000;79:355–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitschopf K, Haendeler J, Malchow P, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Posttranslational modification of Bcl-2 facilitates its proteasome-dependent degradation: molecular characterization of the involved signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1886–1896. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1886-1896.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura S, Karnik SS. Ligand-independent signals from angiotensin II type 2 receptor induce apoptosis. EMBO J. 2000;19:4026–4035. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.15.4026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]