Abstract

The functional consequences of up-regulation of β-catenin as a transcription factor are complex in different tumors. To clarify roles during squamous differentiation (SqD) of endometrial carcinoma (Em Ca) cells, we investigated expression of β-catenin, as well as cyclin D1, p53, p21WAF1, and PML (promyelocytic leukemia) in 80 cases of Em Ca with SqD areas, in comparison with cell proliferation determined with reference to Ki-67 antigen positivity. The impact of β-catenin-T-cell factor (TCF)-mediated transcription was also examined using Em Ca cells. In clinical cases, nuclear β-catenin accumulation was more frequent in SqD areas, being positively linked with expression of cyclin D1, p53, and p21WAF1, and inversely with Ki-67 and PML immunoreactivity. Significant correlations of nuclear β-catenin, cyclin D1, p53, and p21WAF1 were noted between SqD and the surrounding carcinoma lesions. The Ishikawa cell line, with stable or tetracycline-regulated expression of mutant β-catenin, showed an increase in expression levels of cyclin D1, p14ARF, p53, and p21WAF1 but not PML, and activation of β-catenin-TCF4-mediated transcription determined with TOP/FOP constructs. The cell morphology was senescence-like rather than squamoid in appearance. Moreover, overexpressed β-catenin could activate transcription from p14ARF and cyclin D1 promoters, in a TCF4-dependent manner. These findings indicate that in Em Cas, nuclear β-catenin can simultaneously induce activation of the p53-p21WAF1 pathway and overexpression of cyclin D1, leading to suppression of cell proliferation or induction of cell senescence. However, overexpression of β-catenin alone is not sufficient for development of a squamoid phenotype in Em Ca cells, suggesting that nuclear accumulation is an initial signal for trans-differentiation.

β-catenin is a multifunctional protein, acting both as a structural component of the E-cadherin-related cell adhesion system and as a transducer of the Wnt/Wingless signaling pathway.1–3 In quiescent cells, it is phosphorylated by the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) protein-axin/conduction-glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3β complex at its serine or threonine residues, near the NH2 terminus, and is rapidly degraded through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. When the APC gene or the GSK-3β phosphorylation sites in the β-catenin gene are mutated, unphosphorylated, and therefore stabilized β-catenin translocates into the nucleus and interacts with HMG-box transcription factors such as the lymphoid-enhancer factor/T-cell factor (LEF/TCF), resulting in gene expression that mediates the downstream effects of Wnt.4–6

The functional consequences of β-catenin expression during tumorigenesis are complex. For example, β-catenin may exert oncogenic effects by activation of transcription from the gene promoters for cyclin D1 and c-myc, positive regulators of cell proliferation acting at the G1 to S phase transition.7–9 However, overexpressed β-catenin can also induce accumulation of p53 that protects against oncogenic effects.10,11 Moreover, induction of PML (promyelocytic leukemia) expression by β-catenin suppresses the tumorigenicity of renal carcinoma cells, indicating a novel pathway for catenin-mediated growth inhibition.12

We previously demonstrated that β-catenin abnormalities are common in endometrioid type endometrial carcinomas (Em Cas) with areas of squamous differentiation (SqD).13 Interestingly, nuclear accumulation was more frequent in SqD areas, pointing to a possible role of β-catenin during trans-differentiation from glandular to squamoid features. To test this hypothesis, we here investigated the expression of β-catenin, as well as cyclin D1, p53, p21WAF1, and PML, in Em Cas in vivo. In addition, the functional role of β-catenin-TCF4 mediated transcription was also examined in Em Ca cells in vitro.

Materials and Methods

Clinical Cases

Histological findings were reviewed for 234 hysterectomy specimens of endometrioid type Em Cas in the case records of Kitasato University Hospital for the period from 1988 to 2002, according to the criteria of the World Health Organization histological classification (1994). Areas of SqD within tumors were subdivided into two categories, morules and squamous metaplasia (SqM) foci, as described previously.13,14 Briefly, the former were defined as areas consisting of spindle- to cuboidal-shaped cells forming growth sheets (Figure 1A) and the latter were designated as foci consisting of cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and clear intercellular bridging (Figure 2A). The tumors with SqD areas investigated comprised 78 grade 1 and 2 grade 2 lesions, but no grade 3 carcinomas, including 45 (all grade 1) cases with morules and 35 (33 grade one 1 and 2 grade 2) with SqM foci. Some cases overlapped with those used in our previous study.13 Eighteen grade 1 carcinomas without SqD areas were also used as controls. All tissues were routinely fixed in 10% formalin and processed for embedding in paraffin wax.

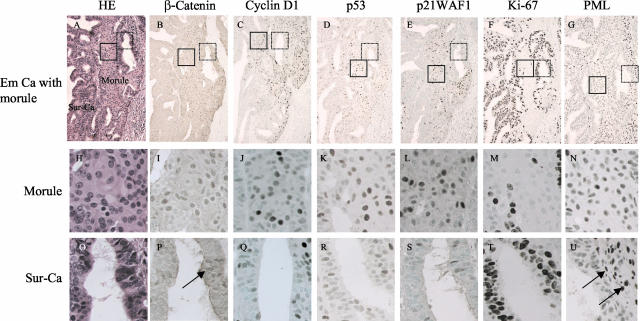

Figure 1.

Serial sections through an Em Ca with a morule. Boxes with solid and dotted lines indicate magnified morule and Sur-Ca regions, respectively. Staining is H&E (A, H, O), and for β-catenin (B, I, P), cyclin D1 (C, J, Q), p53 (D, K, R), and p21WAF1 (E, L, S), Ki-67 (F, M, T), and PML (G, N, U). Note apparent differences in nuclear staining patterns for β-catenin (P, focal nuclear staining in the glandular component indicated by the arrow), cyclin D1, p53, and p21WAF1, and Ki-67 immunoreactivity between morule and Sur-Ca lesions. G, N, U: There is relatively weak PML immunoreactivity in morule (N) and the Sur-Ca (U), in contrast to the reactions for infiltrating lymphocytes and stromal cells (arrows). Original magnifications: ×200 (A–G); ×400 (H–U).

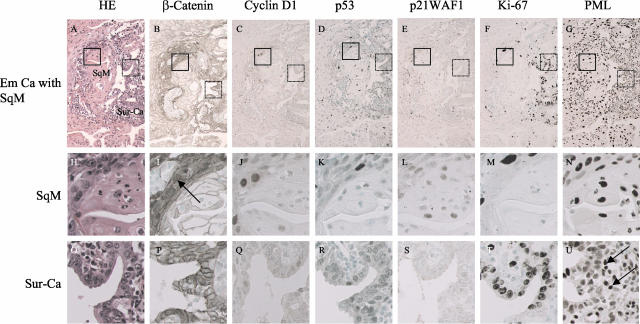

Figure 2.

Serial sections through an Em Ca with an area of squamous metaplasia (SqM). Boxes with solid and dotted lines indicate magnified regions of a SqM area and Sur-Ca, respectively. Staining is H&E (A, H, O), and for β-catenin (B, I, P), cyclin D1 (C, J, Q), p53 (D, K, R), and p21WAF1 (E, L, S), Ki-67 (F, M, T), and PML (G, N, U). Note sporadic nuclear immunoreactivity for β-catenin (I, positive cells are indicated by arrows), cyclin D1, p53, p21WAF1, and Ki-67 in the SqM areas, as well as the Sur-Ca, with the exception of Ki-67 in the latter. G, N, U: There is strong PML immunoreactivity in the SqM areas, as well as infiltrating lymphocytes and stromal cells (U, indicated by arrows). Original magnifications: ×200 (A–G); ×400 (H–U).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed using a combination of the microwave oven heating and standard streptavidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (LSAB kit; DAKO, Copenhagen, Denmark) methods. Briefly, slides were heated in 10 mmol/L citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for two 10-minute cycles using a microwave oven and then incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-β-catenin mouse monoclonal (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY), anti-cyclin D1 mouse monoclonal (DAKO), anti-p53 mouse monoclonal (DO7; Novocastra Lab. Ltd., Newcastle, UK), anti-p21WAF1 mouse monoclonal (WAF1; Calbiochem, Cambridge, MA), anti-human Ki-67 antigen rabbit polyclonal (DAKO), or anti-PML rabbit polyclonal (Chemicom, Temecula, CA) antibodies.

To determine labeling indices (LIs) for β-catenin, cyclin D1, p53, p21WAF1, and Ki-67 nuclear immunoreactivity, immunopositive nuclei were counted for at least 1000 tumor cells in five randomly selected fields of glandular carcinoma components (surrounding carcinoma, Sur-Ca) and at least 700 cells in all of the SqD areas within tumors in each case, using high-power (×40 objective and ×10 ocular) magnification. LIs were then calculated as numbers per 100 cells. Scoring of the PML immunoreactivity was also performed according to the method described previously.14,15 Briefly, the percentage of immunopositive cells in the total tumor cell population was subdivided into five categories as follows; 0, all negative; 1, <30% positive cells; 2, 30 to 50%; 3, 50 to 70%; 4, >70%. The immunointensity was also subclassified into four groups in comparison with infiltrating lymphocytes and stromal cells as positive internal controls, as follows: 0, negative; 1+, weak; 2+, moderate; 3+, strong. The internal controls were set as 3+. Immunoreactivity scores for both SqD and the Sur-Ca lesions for each case were produced by multiplication of the two values.

Polymerase Chain Reaction and Sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from cultured cells and 4-μm-thick paraffin wax sections of clinical samples, using proteinase K/phenol-chloroform methods. Exon 3 of the β-catenin gene was amplified and sequenced as described previously.12,16

Cell Line and Plasmids

The Ishikawa Em Ca cell line17 was maintained in Eagle’s minimal essential medium with 10% bovine calf serum. The β-catenin plasmid containing a deleted Ser-45 (β-cat▵S45) was kindly provided by Dr. Y. Nakamura (Institute of Medical Science, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan). The cyclin D1 (−962CD1-luc) and the PML (PML-S-luc) promoter reporter plasmids were from Dr. O. Tetsu (University of California, San Francisco, CA) and Dr. A. Ben-Ze’ev (The Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel), respectively. The p14ARF (−3704 p14ARF-luc) promoter reporter construct bearing a 3407-bp fragment of p14ARF promoter region created from the p14ARF promoter gene (provided by Dr. K. Robertson, The University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA) was subcloned into pGL2-basic (Promega, Madison, WI). TCF4 lacking a 30-amino acid β-catenin binding site in its N-terminus (TCF4▵N30) plasmid (provided by Dr. S. Hirohashi, National Cancer Center Research Institute, Tokyo, Japan) was introduced into pcDNA3.1+ (Invitrogen, Tokyo, Japan). The p21 promoter reporter (p21-luc) and wild-type (wt) p53 expression (pCMVp53wt) plasmids were from Dr. C. Prives (Columbia University, New York, NY) and the PML expression (pSG5-PML) construct was from Dr. T. Sternsdorf (The Salk Institute for Biological Studies, California). Top-FLASH and Fop-FLASH (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) were also applied.

Establishment of Cells with Stable and Inducible Mutant β-Catenin Expression

To establish cells stably expressing mutant β-catenin, the β-cat▵S45 construct and empty pcDNA3.1+ plasmids for comparison were transfected into Ishikawa cells using LipofectAMINE PLUS (Invitrogen). After ∼2 weeks of culture in the presence of 1 mg/ml of Geneticin (Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, NY), the colonies stably expressing β-cat▵S45 were screened by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction assay using a combination of a forward primer lacking codon 45 (5′-CCACTACCACAGCTCCTCT-3′ at exon 3) and a reverse primer (5′-TGAGCTCGAGTCATTGCATAC-3′ at exon 4), and were confirmed by sequencing analysis.

A stable clone, capable of producing mutant β-catenin, was also established using a tetracycline-regulated expression system (Invitrogen). Ishikawa cells were double-transfected sequentially with regulatory pcDNA6/TR and either responsive pcDNA4/TO-β-cat▵S45 or empty pcDNA4/TO plasmids using LipofectAMINE PLUS (Invitrogen). After selection of colonies with 5 μg/ml of blasticidin and 250 μg/ml of zeocin, those with induced expression of β-cat▵S45 in the presence of 1 μg/ml of tetracycline were screened and isolated in a similar manner.

Transient Transfection and Luciferase Reporter Assay

Cells were plated to form 60 to 80% confluent cultures in 24-well dishes. All transfection experiments were performed using the LipofectAMINE PLUS method (Invitrogen), in duplicate or triplicate, in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The pRL-TK plasmid (Promega) was co-transfected to normalize for transfection efficiency and the total amount of transfected plasmid was made equal by addition of empty pcDNA3.1+ vector (Invitrogen). Luciferase activity was assayed 24 hours after transfection, using a dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega).

Western Blot Assays

Total cellular proteins were isolated using RIPA buffer [50 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH7.2), 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate] containing protease inhibitor (phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride). Aliquots of 1 to 20 μg of total proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to a membrane, and probed with anti-cyclin D1 mouse monoclonal (sc-8396; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-p14ARF rabbit polyclonal (sc-8340, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-p53 mouse monoclonal (DO7, Novocastra Lab. Ltd), anti-p21WAF1 mouse monoclonal (WAF1, Calbiochem), anti-PML rabbit polyclonal (Chemicon), and anti-β-actin mouse monoclonal (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) antibodies, coupled with the ECL detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunofluorescence

Cells were grown to form 50 to 60% confluent cultures on glass slides. The monolayers were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes, permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes, then incubated with anti-β-catenin mouse monoclonal antibody (Transduction Laboratories) for 1 hour at room temperature. Forty hours after transient transfection of β-cat▵S45 plasmid into Ishikawa cells or 1 μg/ml of tetracycline treatment for β-cat▵S45-inducible clones, cells were also stained with both anti-β-catenin monoclonal (Transduction Laboratories) and anti-p53 polyclonal (CM1, Novocastra Lab. Ltd.) antibodies. The secondary antibodies were fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled rabbit anti-mouse IgG and rhodamine-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (both from Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands).

Senescence-Associated β-Galactosidase (SA-β-gal) Assay

The β-cat▵S45-inducible and mock clones were grown on glass slides, and 2, 4, or 5 days after tetracycline treatment were stained for SA-β-gal activity, in triplicate, as described previously.18 At least 500 cells were scored to determine the percentages of blue-stained cells.

Statistics

Comparative data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U-test, the Pearson’s correlation coefficient, and the chi-square test. The cutoff for statistical significance was set as P < 0.05.

Results

Immunohistochemical Findings for Em Cas with SqD Features

Average ages of patients with Em Cas featuring areas of morules and SqM were 41.2 ± 10.5 years (mean ± SD) and 54.9 ± 11.1 years, respectively, the difference being significant (P < 0.0001) with a value of 56.9 ± 6.1 for tumors without SqD areas. Examples of immunohistochemical findings for β-catenin, cyclin D1, p53, p21WAF1, Ki-67, and PML in Em Ca with morule and SqM are illustrated in Figures 1 and 2.

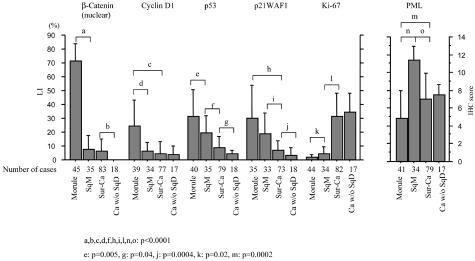

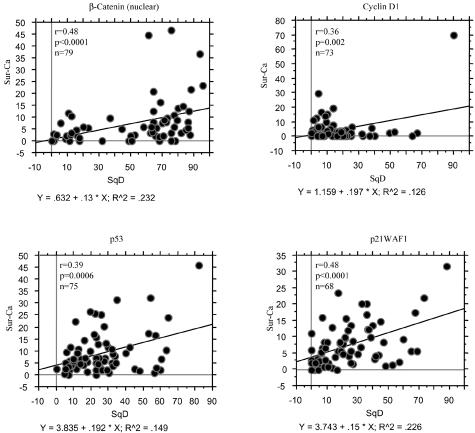

Average LIs for both nuclear β-catenin and cyclin D1 were significantly higher in morules than SqM and the Sur-Ca lesions. Significant stepwise decreases from morules, through SqM, to the Sur-Ca lesions were observed in LIs for both p53 and p21WAF1, but not Ki-67. PML immunoreactivity was significantly lower in morules than in Sur-Ca lesions, whereas SqM areas demonstrated significant increase. There were significant differences in LIs for nuclear β-catenin, p53, and p21WAF1 between glandular components of tumors with and without SqD areas (Figure 3). Significantly positive correlations of LI values for nuclear β-catenin, as well as cyclin D1, p53, and p21WAF1, were observed between SqD areas and the Sur-Ca lesions (Figure 4), while such associations were not evident for Ki-67 and PML (data not shown).

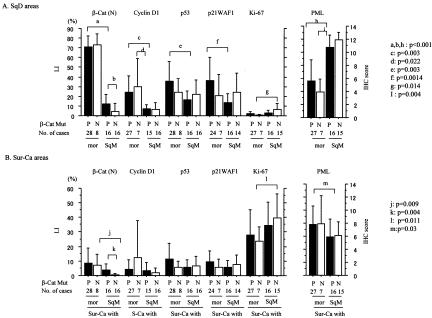

Figure 3.

Relations of LIs or immunohistochemistry scores for nuclear β-catenin, cyclin D1, p53, p21WAF1, Ki-67, and PML among morules, areas of squamous metaplasia (SqM), and the surroundings or glandular carcinomas without SqD (Sur-Ca and Ca w/o SqD). The data are means ± SD values.

Figure 4.

Correlations of LIs for β-catenin, cyclin D1, p53, and p21WAF1 between areas of SqD and the Sur-Ca lesions. r, Pearson’s correlation coefficient; n, number of cases. The data are means ± SD values.

Mutations in exon 3 of the β-catenin gene were detected in 46 (66.7%) of 69 informative Em Ca cases, including 29 (78.4%) of 37 with morules and 17 (53.1%) of 32 with SqM lesions, the difference being significant (P = 0.026) (Table 1). None of the tumors without SqD showed any mutations in exon 3 of the gene. In morules and SqM areas, no significant differences in LI values for the markers investigated were observed when cases were subdivided into two groups on the basis of the β-catenin gene status, with the exception of nuclear β-catenin LI in SqM areas (Figure 5A). Similar findings were also noted in the Sur-Ca lesions (Figure 5B).

Table 1.

Summary of β-Catenin Exon 3 Mutations in Endometrial Carcinomas with Areas of Squamous Differentiation

| Number of cases | Codon | Nucleotide change | Aminoacid change | Total | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Em Ca with morule | 2 | 32 | GAC to CAC | Asp to His | |||

| 3 | 32 | GAC to TAC | Asp to Tyr | ||||

| 6 | 33 | TCT to TGT | Ser to Cys | ||||

| 1 | 33 | TCT to TAT | Ser to Tyr | 29/37 (78.4%) | |||

| 2 | 34 | GGA to GTA | Gly to Val | ||||

| 2 | 34 | GGA to GAA | Gly to Glu | ||||

| 3 | 37 | TCT to GCT | Ser to Ala | ||||

| 3 | 37 | TCT to TTT | Ser to Phe | ||||

| 6 | 37 | TCT to TGT | Ser to Cys | ||||

| 1 | 41 | ACC to ATC | Thr to Ile | 0.026 | |||

| Em Ca with SqM | 1 | 33 | TCT to TGT | Ser to Cys | |||

| 1 | 34 | GGA to GTA | Gly to Val | ||||

| 1 | 34 | GGA to GAA | Gly to Glu | ||||

| 1 | 34 | GGA to GCT | Gly to Ala | ||||

| 3 | 37 | TCT to TGT | Ser to Cys | 17/32 (53.1%) | |||

| 2 | 37 | TCT to TTT | Ser to Phe | ||||

| 1 | 37 | TCT to GCT | Ser to Ala | ||||

| 1 | 37 | TCT to TAT | Ser to Tyr | ||||

| 1 | 41 | ACC to GCC | Thr to Ala | ||||

| 2 | 41 | ACC to ATC | Thr to Ile | ||||

| 3 | 45 | TCT to TTT | Ser to Phe |

Em, endometrial carcinoma; SqM, squamous metaplasia.

Figure 5.

Relations of LIs or immunohistochemistry scores for nuclear β-catenin, cyclin D1, p53, p21WAF1, Ki-67, and PML with the β-catenin gene status (P, mutation positive; N, negative) in areas of SqD (A) and Sur-Ca categories (B). mor, Morule; SqM, squamous metaplasia; β-Cat Mut, β-catenin gene mutation. The data are means ± SD values.

As shown in Table 2, nuclear β-catenin LI values were positively correlated with LIs for cyclin D1, p53, and p21WAF1, and inversely with Ki-67 LIs and PML scores overall. Similar associations with cyclin D1 LIs and PML scores were also observed in SqD but not Sur-Ca categories. Positive correlations among LIs of p53, p21WAF1, and cyclin D1 were evident in all three categories, with some exceptions. There was no correlation of PML scores with either p53 or p21WAF1 LIs in any of the three categories (data not shown).

Table 2.

Correlations among β-Catenin, Cyclin D1, p53, p21WAF1, Ki-67, and PML for Areas of Squamous Differentiation and the Surrounding Glandular Endometrial Carcinomas

| β-Catenin versus

|

p53 versus

|

p21WAF1 versus

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclin D1

|

p53

|

p21WAF1

|

Ki-67

|

PML

|

Cyclin D1

|

p21WAF1

|

Ki-67

|

PML

|

Cyclin D1

|

|

| r (p) | r (p) | r (p) | r (p) | r (p) | r (p) | r (p) | r (p) | r (p) | r (p) | |

| Overall | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.41 | −0.57 | −0.36 | 0.56 | 0.73 | −0.4 | 0.01 | 0.52 |

| (SqD+Sur-Ca areas) | (<0.0001) | (<0.0001) | (<0.0001) | (<0.0001) | (<0.0001) | (<0.0001) | (<0.0001) | (<0.0001) | (0.86) | (<0.0001) |

| n = 165 | n = 170 | n = 157 | n = 175 | n = 169 | n = 159 | n = 159 | n = 169 | n = 161 | n = 146 | |

| SqD areas | 0.52 | 0.29 | 0.23 | −0.34 | −0.77 | 0.46 | 0.64 | 0.1 | −0.2 | 0.41 |

| (Morule+SqM) | (<0.0001) | (0.01) | (0.065) | (0.002) | (<0.0001) | (<0.0001) | (<0.0001) | (0.38) | (0.108) | (0.001) |

| n = 72 | n = 74 | n = 67 | n = 77 | n = 74 | n = 69 | n = 68 | n = 74 | n = 70 | n = 62 | |

| Sur-Ca areas | 0.009 | 0.14 | 0.09 | −0.36 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.51 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| (0.93) | (0.16) | (0.37) | (0.0003) | (0.02) | (0.2) | (<0.0001) | (0.08) | (0.95) | (0.69) | |

| n = 93 | n = 96 | n = 90 | n = 98 | n = 95 | n = 90 | n = 91 | n = 95 | n = 91 | n = 84 | |

r, Pearson’s correlation coefficient; SqD, squamous differentiation; Sur-Ca, surrounding carcinoma; SqM, squamous metaplasia; n, number of cases.

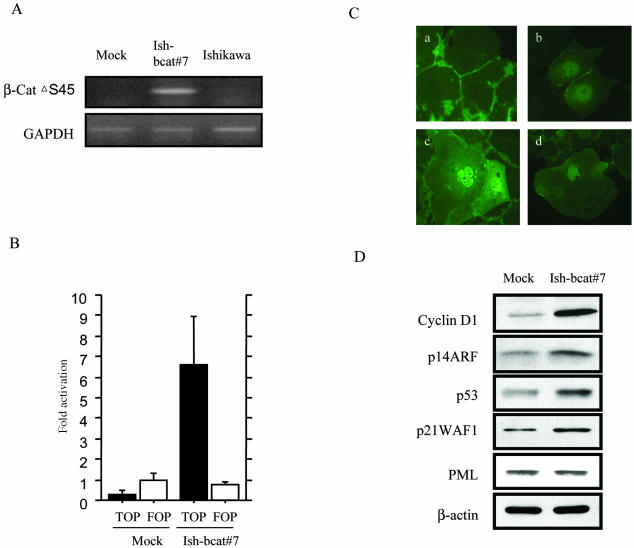

Ishikawa Cells Stably Expressing Mutant β-Catenin

Based on sequence analysis of β-catenin and p53 genes, Ishikawa cells with wild types of both genes were selected from five Em Ca cell lines, including Hec6, Hec88, Hec108, and Hec265 cells. The Ish-bcat#7 clone constitutively expressed the β-cat▵S45 mRNA, resulting in activation of β-catenin-TCF transcription, as assessed with reference to TOP and FOP reporter constructs (Figure 6, A and B). On immunofluorescence analysis, strong nuclear β-catenin accumulation was detected in ∼30% of cells of the stable clone, whereas immunoreactivity was limited to cell membranes in the mock case. Some Ish-bcat#7 cells with nuclear β-catenin expression demonstrated increase in size, and were more spread and flattened and multinucleated but not squamoid in appearance (Figure 6C). In addition, increased expression of cyclin D1, p14ARF, p53, and p21WAF1 but not PML was evident in Ish-bcat#7 cells (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Ishikawa cells stably expressing mutant β-catenin. A: Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction results demonstrating expression of β-cat▵S45 mRNA in Ish-bcat#7 but not mock-transfected or the parent (Ishikawa) cells. Expression of GAPDH mRNA was used as an internal control. B: β-Catenin-TCF-mediated transcriptional activity. Ish-bcat#7 and mock cells were transfected with either TOP-FLASH or FOP-FLASH (100 ng), together with pRL-TK plasmid (50 ng). Relative activities are derived from arbitrary light units of luciferase activity normalized for pRL-TK activity. The data are means ± SD values. C: Immunofluorescence of β-catenin in mock-transfected (a) and Ish-bcat#7 cells (b–d). Note the multinucleated (c) and senescence-like (d) appearances of Ish-bact#7 cells expressing nuclear β-catenin. D: Western blot analysis of cyclin D1, p14ARF, p53, and p21WAF1 but not PML in mock and Ish-bcat#7 clones. The β-actin level serves as loading control.

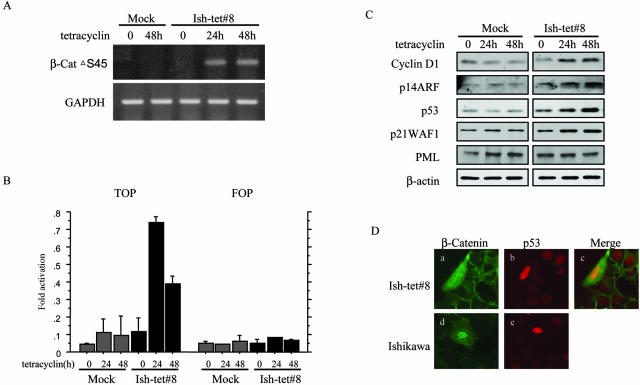

Tetracycline-Regulated Mutant β-Catenin Expression in Ishikawa Cell

In the presence of tetracycline, the Ish-tet#8 clone exhibited β-cat▵S45 mRNA expression, with activation of the TOP-reporter construct and elevated expression levels of cyclin D1, p14ARF, p53, and p21WAF1 but not PML, in a time-dependent manner (Figure 7; A to C). Cells with inducible nuclear β-catenin showed overexpression of endogenous p53, in line with the results of transient transfection of β-cat▵S45 into the parent cells (Figure 7D).

Figure 7.

Ishikawa cells, sensitive to tetracycline for induction of β-catenin. A: Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction assay. Note the induction of β-cat▵S45 mRNA in Ish-tet#8 but not mock cells after 24 and 48 hours of 1 μg/ml of tetracycline. Expression of GAPDH mRNA was used as an internal control. B: Induction of β-catenin-TCF4-mediated transcriptional activity by tetracycline treatment. After transfection of either TOP-FLASH or FOP-FLASH (100 ng), together with pRL-TK plasmid (50 ng), Ish-tet#8 and mock cells were treated with 1 μg/ml of tetracycline for 24 hours or 48 hours. Relative activities are derived from arbitrary light units of luciferase activity normalized for pRL-TK activity. The data are means ± SD values. C: Western blot analysis of cyclin D1, p14ARF, p53, and p21WAF1 but not PML in mock and Ish-tet#8 clones after 1 μg/ml of tetracycline treatment for 24 hours or 48 hours. The β-actin level serves as a loading control. D: Double immunostaining for β-catenin and p53 in Ish-tet#8 cells (a–c) after 40 hours of 1 μg/ml of tetracycline treatment. The parent (Ishikawa) cells, 40 hours after transient transfection with 400 ng of β-cat▵S45 construct, are also stained in a similar manner (d, e). Note the co-localization of β-catenin and p53 in nuclei.

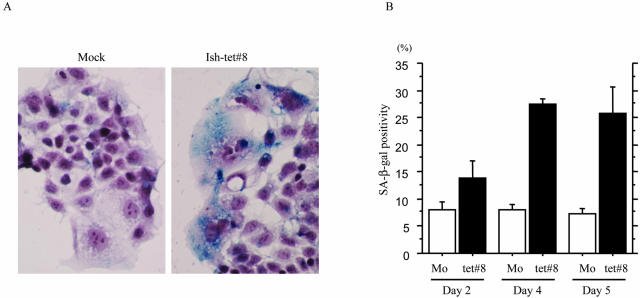

After tetracycline treatment, there was an increase in numbers of senescence-like Ish-tet#8 cells similar to the case with Ish-bcat#7 cells. Four and five days after tetracycline treatment, SA-β-gal-positive cells were significantly increased with Ish-tet#8, but not the mock clones (Figure 8). Cells with squamoid features were never observed.

Figure 8.

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) assay results. A: After 5 days 1 μg/ml of tetracycline treatment blue staining is evident in Ish-tet#8 cells with senescence-like features, but almost lacking in mock. B: Percentage of SA-β-gal-positive cells after 2, 4, and 5 days of 1 μg/ml of tetracycline treatment in the Ish-tet#8 and mock cases. The data are means ± SD values.

β-Catenin Enhances Transcription of the p14ARF and Cyclin D1 but Not PML Genes

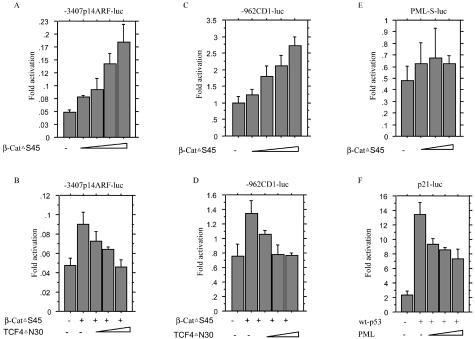

Transient transfection of β-cat▵S45 constructs caused a dose-dependent increase in reporter activity of the −3407 p14ARF-luc containing one perfect TCF binding site (position −2686, AACAATG) and two imperfect sites (position −686, CACAAAG and −579, AGCAATG A), the transcriptional activity being inhibited by co-transfection of the TCF4▵N30 plasmid with dose dependence (Figure 9, A and B), in line with the case for cyclin D1 reporter activity (Figure 9, C and D). Changes in PML promoter activity on transfection of β-cat▵S45 were relatively minor, whereas p21WAF1 promoter activity induced by wt p53 was suppressed by co-transfection of PML in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 9, E and F).

Figure 9.

A to E: β-Catenin-TCF4-mediated transcription of p14ARF (A, B), cyclin D1 (C, D) and PML (E) genes. A, C: Ishikawa cells were transfected with 100 ng of either −3407 p14ARF-luc (A) or −962 CD1-luc (C) and various amounts of β-cat▵S45 construct (0, 50, 100, 200, 250 ng), together with the pRL-TK plasmid (50 ng). Relative activities are derived from arbitrary light units of luciferase activity normalized for pRL-TK activity. B, D: Ishikawa cells were transfected with 100 ng of either −3407 p14ARF-luc or −962 CD1-luc, 100 ng of β-cat▵S45, and various amounts of TCF4▵N30 plasmid (0, 50,100,150 ng). E: Ishikawa cells were transfected with 100 ng of PML-S-luc and various amounts of β-cat▵S45 construct (0, 50, 100, 200, 250 ng). F: Effects of p53 and PML expression on the p21WAF1 promoter reporter. Ishikawa cells were transfected with 100 ng of p21-luc, 10 ng of pCMVp53wt, and various amounts of pSG5-PML (0, 10, 20, 50 ng). The data are means ± SD values.

Discussion

Most p53 detected by immunohistochemistry in this study would be expected to be functional, although we did not perform DNA sequencing for the p53 gene. Reasons for this conclusion include the following: 1) a positive correlation was evident between p53 and p21WAF1 in both SqD and the Sur-Ca lesions, in line with evidence that p21WAF1 promoter is activated by transient transfection of wt p53 (Figure 9F); 2) most tumors investigated were categorized into the grade 1 endometrioid type, and p53 gene mutations are relatively rare, in contrast to the grade 3 or nonendometrioid types;19–21 3) most Sur-Ca lesions showed low p53 LI values (<10%), and high LIs (>30%) are typical (90%) of mutated cases.22

We demonstrated here that high levels of nuclear β-catenin expression can be detected even in morules of tumors without gene mutations, in line with findings that gene mutations are not sufficient by themselves to cause nuclear accumulation.23 Given that most cases were early onset (average age, 41.2 ± 10.5 years) in the premenopausal phase, it is possible that endogenous progesterone may affect the regulation of nuclear β-catenin expression, because the nuclear accumulation was closely linked with gene mutations in SqM areas within tumors in older patients (54.9 ± 11.1 years) (Figure 4A). Moreover, our previous results demonstrated a stabilization of nuclear and cytoplasmic β-catenin by progesterone in Em Ca in vivo and in vitro.24 Other possible factors include alterations in β-catenin degradation-related genes, such as APC and Axin, but such gene mutations are considered to be rare in Em Cas.23,25 It remains to be elucidated why expression levels of nuclear β-catenin were relatively low in the Sur-Cas around morule lesions.

There are various lines of evidence that nuclear β-catenin is involved in dedifferentiation or trans-differentiation during development or progression of gastric and colorectal carcinomas.26–28 In β-catenin transgenic mice, stabilization of β-catenin through the deletion of exon 3 results in development of squamous metaplasia of the mammary epithelium.29,30 These data prompted us to investigate the association between overexpression of β-catenin and induction of SqD in Em Ca cells. Although Ishikawa cells overexpressing nuclear β-catenin showed a senescence-like appearance, there were no squamoid elements, indicating that other factors, presumably including the tumor environment consisting of stromal cells and extracellular matrix, are also necessary for SqD. This conclusion is supported by the finding that specific signals from the microenvironment regulate intracellular β-catenin distribution and subsequently the process of dedifferentiation and redifferentiation of colorectal tumor cells.28 One interesting result in our previous study was an increase in the percentage of SqD areas within Em Cas in patients receiving progesterone therapy.31

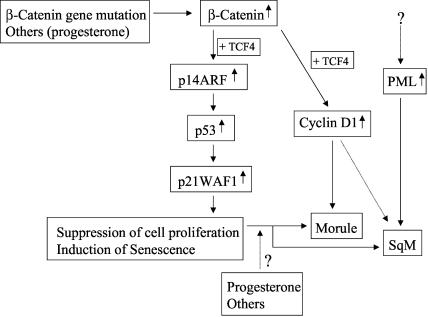

It was recently shown that deregulated β-catenin elicits ARF-mediated p53-dependent growth arrest.11 Our in vitro results suggest that overexpression of β-catenin might result in activated transcription from the p14ARF promoter in a TCF4-dependent manner (Figure 9, A and B), this being sufficient to induce p53 in nuclei (Figure 7D). Positive correlations among nuclear β-catenin, p53, and p21WAF1 expression were also evident in vivo (Table 2). It is therefore conceivable that nuclear β-catenin can activate the p53-p21WAF1 pathway, probably through the p14ARF-Mdm2-p53 regulatory loop,32 so that nuclear accumulation may be an initial signal for trans-differentiation toward the squamoid phenotype in Em Ca cells (Figure 10). This conclusion is supported by three lines of evidence. The first is that nuclear accumulation can be detected even in small squamoid nests consisting of a few cells, as described previously;13 the second is that expression levels of β-catenin, p53, and p21WAF1 significantly differ between tumors with and without SqD areas (Figure 3); and the third is that there were significant correlations of β-catenin and its target gene expression between SqD and the Sur-Ca lesions (Figure 4). With regard to the relative levels of nuclear β-catenin and p53 in SqM areas, one possible explanation is the existence of an autoregulatory feedback loop between β-catenin and p53, because p53 also induces β-catenin degradation in response to growth arrest.33 Further studies of these points are clearly warranted.

Figure 10.

Proposed molecular mechanisms underlying development of SqD in Em Cas. β-Catenin gene mutations and other factors, including endogenous progesterone, lead to accumulation of nuclear β-catenin and aberrant activation (by β-catenin together with TCF4) of the p14ARF-p53-p21WAF1 pathway that suppresses cell proliferation and induces senescence. Other factors, including progesterone, may also be required for development of squamoid phenotypes of Em Ca cells, with β-catenin as the initial signal for the trans-differentiation. Overexpression of cyclin D1 induced by β-catenin and PML expression may also play an important role in formation of morules or areas of squamous metaplasia (SqM).

A surprising finding in this study is that β-catenin may simultaneously induce not only activation of the p53-p21WAF1 pathway, but also cyclin D1 expression in SqD areas. Given the complete lack of the Ki-67 immunoreactivity in such lesions, effects of the overexpression may be inhibited by the anti-proliferative influence of p53-dependent pathways. In addition, G1 cyclins, including cyclin D1/Cdk4, p16INK4A, or pRb, are not considered to be essential for completion of most normal cell division cycles, because overexpressed G1 cyclins do not generally increase net cell proliferation, despite accelerating G1 to S progression.34 It has been reported that in colorectal carcinomas nuclear β-catenin, cyclin D1, and p16INK4A are frequently co-localized in tumor cells at invasive fronts, resulting in a low rate of the proliferation.35 In our series, however, overexpression of p16INK4A was relatively rare in SqD areas of Em Cas (data not shown).

In 293T cells, β-catenin can activate transcription from the PML promoter, independent of TCF/LEF status, suggesting that it may operate by interacting with the basic transcriptional machinery.12 In our results, appreciable increase in PML promoter activity was not conferred by transfection of β-catenin in Ishikawa cells (Figure 9E), in line with findings of the protein levels (Figures 6D and 7C), and an inverse correlation between nuclear β-catenin and PML expression was evident in SqD areas (Table 2).

PML plays an important role in the p53-regulatory pathway for apoptosis and cell growth suppression without direct binding to p53-responsive elements of target genes, such as p21WAF1, Bax, and GADD45.36 Given the high levels of PML, p53, and p21WAF1 expression in SqM areas (Figure 3), an increase in p21 promoter activity was expected on co-transfection of wt p53 and PML, but our reporter assay demonstrated that PML caused suppression of p53-dependent p21 transcriptional activity in Ishikawa cells (Figure 9F). Similar findings have also been reported for MG63, human osteosarcoma cells.37 Thus, there are promoter-specific and cell-type-specific aspects to the functional cooperation between p53 and PML.

In conclusion, our findings imply that in Em Cas, nuclear β-catenin can simultaneously induce activation of the p53-p21WAF1 pathway and overexpression of cyclin D1, leading to suppression of cell proliferation or induction of cell senescence. However, overexpression of β-catenin alone is not sufficient for development of the squamoid phenotype of Em Ca cells, suggesting that nuclear accumulation is an initial signal for the trans-differentiation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Y. Nakamura, O. Tetsu, A. Ben-Ze’ev, K. Robertson, S. Hirohashi, C. Prives, and T. Sternsdorf for gifts of the expression and reporter plasmids used in this study.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Makoto Saegusa, M.D., Department of Pathology, 1-15-1 Kitasato, Sagamihara, Kanagawa, 228-8555 Japan. E-mail: msaegusa@med.kitasato-u.ac.jp.

Supported, in part, by research grants from the Kanagawa Academy of Science and Technology and grants from the Kanzawa Medical Research Foundation.

References

- Ozawa M, Baribault H, Kemler R. The cytoplasmic domain of the cell adhesion molecule uvomorulin associates with three independent proteins structurally related in different species. EMBO J. 1989;8:1711–1717. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03563.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemler R. From cadherins to catenins: cytoplasmic protein interactions and regulation of cell adhesion. Trends Genet. 1993;9:317–321. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90250-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumbiner B. Signal transduction by β-catenin. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;7:634–640. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korinek V, Barker N, Morin PJ, van Wichen D, de Weger R, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Clevers H. Constitutive transcriptional activation by a β-catenin-Tcf complex in APC−/− colon carcinoma. Science. 1997;275:1784–1787. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin PJ, Sparks AB, Korinek V, Barker N, Clevers H, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Activation of β-catenin-Tcf signaling in colon cancer by mutations in β-catenin or APC. Science. 1997;275:1787–1790. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinfeld B, Robbins P, El-Gamil M, Albert I, Porfiri E, Polakis P. Stabilization of β-catenin by genetic defects in melanoma cell lines. Science. 1997;275:1790–1792. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He T-C, Sparks AB, Rago C, Hermeking H, Zawel L, da Costa LT, Morin PJ, Vogelstein B, Kinzler K. Identification of c-MYC as a target of the APC pathway. Science. 1998;281:1509–1512. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5382.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetsu O, McCormick F. β-Catenin regulates expression of cyclin D1 in colon carcinoma cells. Nature. 1999;398:422–426. doi: 10.1038/18884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shtutman M, Zhurinsky J, Simcha I, Albanese C, D’Amico M, Pestell R, Ben-Ze’ev A. The cyclin D1 gene is a target of the β-cateni/LEF-1 pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5522–5527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damalas A, Ben-Ze’ev A, Simcha I, Shtutman M, Leal JFM, Zhurinsky J, Geiger B, Oren M. Excess β-catenin promotes accumulation of transcriptionally active p53. EMBO J. 1999;18:3054–3063. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.11.3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damals A, Kahan S, Shtutman M, Ben-Ze’ev A, Oren M. Deregulated β-catenin induces a p53- and ARF-dependent growth arrest and cooperates with Ras in transformation. EMBO J. 2001;17:4912–4922. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shtutman M, Zhurinsky J, Oren M, Levina E, Ben-Ze’ev A. PML is a target gene of β-catenin and plakoglobin, and coactivates β-catenin-mediated transcription. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5947–5954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saegusa M, Okayasu I. Frequent nuclear β-catenin accumulation and associated mutations in endometrioid-type endometrial and ovarian carcinomas with squamous differentiation. J Pathol. 2001;194:59–67. doi: 10.1002/path.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saegusa M, Okayasu I. Down-regulation of bcl-2 expression is closely related to squamous differentiation and progesterone therapy in endometrial carcinomas. J Pathol. 1997;182:429–436. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199708)182:4<429::AID-PATH872>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saegusa M, Kamata Y, Isono M, Okayasu I. Bcl-2 expression is closely correlated with a low apoptotic index and associated with progesterone receptor immunoreactivity in endometrial carcinomas. J Pathol. 1996;180:275–282. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199611)180:3<275::AID-PATH660>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saegusa M, Hashimura M, Yoshida T, Okayasu I. β-Catenin mutations and aberrant nuclear expression during endometrial tumorigenesis. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:209–217. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida M, Kasahara K, Kaneko M, Iwasaki H. Establishment of a new human endometrial adenocarcinoma cell line, Ishikawa cells, containing estrogen and progesterone receptors. Acta Obstet Gynec Jpn. 1985;37:1103–1110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer DL, Chang B-D, Chen Y, Diegelman P, Alm K, Black AR, Roninson IB, Porter CW. Polyamine depletion in human melanoma cells leads to G1 arrest associated with induction of p21WAF1/CIP1/SDI1, changes in the expression of p21-regulated genes, and a senescence-like phenotype. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7754–7762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman ME, Bur ME, Kurman RJ. p53 in endometrial cancer and its putative precursors: evidence for diverse pathways of tumorigenesis. Hum Pathol. 1995;26:1268–1274. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(95)90204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro H, Isacson C, Levine R, Kurman RJ, Cho KR, Hedrick L. p53 gene mutations are common in uterine serous carcinoma and occur early in their pathogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:177–185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saegusa M, Okayasu I. Bcl-2 is closely correlated with favorable prognostic factors and inversely associated with p53 protein accumulation in endometrial carcinomas: immunohistochemical and polymerase chain reaction/loss of heterozygosity findings. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1997;123:429–434. doi: 10.1007/BF01372546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baas IO, Mulder J-WR, Offerhaus JA, Vogelstein B, Hamilton SR. An evaluation of six antibodies for immunohistochemistry of mutant p53 gene product in archival colorectal neoplasms. J Pathol. 1994;172:5–12. doi: 10.1002/path.1711720104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Bueno G, Hardisson D, Sanchez C, Sarrio D, Cassia R, Garcia-Rostan G, Prat J, Guo M, Herman JG, Matias-Guiu X, Esteller M, Palacios J. Abnormalities of the APC/β-catenin pathway in endometrial cancer. Oncogene. 2002;21:7981–7990. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saegusa M, Hamano M, Kuwata T, Yoshida T, Hashimura M, Akino F, Watanabe J, Kuramoto H, Okayasu I. Up-regulation and nuclear localization of β-catenin in endometrial carcinoma in response to progesterone therapy. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:103–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01360.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlosshauer PW, Pirog EC, Levine RL, Ellenson LH. Mutational analysis of the CTNNB1 and APC genes in uterine endometrioid carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:1006–1071. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner T, Muller S, Hattori T, Mukaisyo K, Papadopoulos T, Brabletz T, Jung A. Metaplasia, intraepithelial neoplasia and early cancer of the stomach are related to dedifferentiated epithelial cells defined by cytokeratin-7 expression in gastritis. Virchows Arch. 2001;439:512–522. doi: 10.1007/s004280100477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner T, Brabletz T. Patterning and nuclear β-catenin expression in the colonic adenoma-carcinoma sequence: analogies with embryonic gastrulation. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:1113–1121. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64626-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brabletz T, Jung A, Reu S, Porzner M, Hlubek F, Kunz-Schughart LA, Knuechel R, Kirchner T. Variable β-catenin expression in colorectal cancers indicates tumor progression driven by the tumor environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10356–10361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171610498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi K, Shillingford JM, Le Provost F, Gounari F, Bronson R, von Boehmer H, Taketo MM, Cardiff RD, Hennighausen L, Khazaie K. Activation of β-catenin signaling in differentiated mammary secretory cells induces transdifferentiation into epithermis and squamous metaplasias. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:219–224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012414099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi K, Rosner A, Nozawa M, Byrd C, Morgan F, Landesman-Bollag E, Xu X, Seldin DC, Schmidt EV, Taketo MM, Robinson GW, Cardiff RD, Hennighausen L. Activation of different Wnt/β-catenin signaling components in mammary epithelium induces transdifferentiation and the formation of pilar tumors. Oncogene. 2002;21:5548–5556. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saegusa M, Okayasu I. Progesterone therapy for endometrial carcinoma reduces cell proliferation but does not alter apoptosis. Cancer. 1998;83:111–121. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980701)83:1<111::aid-cncr15>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson K, Jones PA. The human ARF cell cycle regulatory gene promoter is a CpG island which can be silenced by DNA methylation and down-regulated by wild-type p53. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6457–6473. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadot E, Geiger B, Oren M, Ben-Ze’ev A. Down-regulation of β-catenin by activated p53. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:6768–6781. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.20.6768-6781.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quelle DE, Ashmun RA, Shurtleff SA, Kato JY, Bar-Sagi D, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ. Overexpression of mouse D-type cyclins accelerates G1 phase in rodent fibroblasts. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1559–1571. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.8.1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung A, Schrauder M, Oswald U, Knoll C, Sellberg P, Palmqvist R, Niedobitek G, Brabletz T, Kirchner T. The invasion front of human colorectal adenocarcinomas shows co-localization of nuclear β-catenin, cyclin D1, and p16INK4A and is a region of low proliferation. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1613–1617. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63007-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo A, Salomoni P, Luo J, Shih A, Zhong S, Gu W, Pandolfi PP. The function of PML in p53-dependent apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:730–736. doi: 10.1038/35036365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogal V, Gostissa M, Sandy P, Zacchi P, Sternsdorf T, Jensen K, Pandolfi PP, Will H, Schneider C, Sal GD. Regulation of p53 activity in nuclear bodies by a specific PML isoform. EMBO J. 2000;19:6185–6195. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.22.6185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]