Abstract

Salmonella FliI is the ATPase that drives flagellar protein export. It normally exists as a complex together with the regulatory protein FliH. A fliH null mutant was slightly motile, with overproduction of FliI resulting in substantial improvement of its motility. Mutations in the cytoplasmic domains of FlhA and FlhB, which are integral membrane components of the type III flagellar export apparatus, also resulted in substantially improved motility, even at normal FliI levels. Thus, FliH, though undoubtedly important, is not essential.

Bacterial flagellar assembly begins with the basal body, followed by the hook and finally the filament (11). Almost all of the external components are translocated into a central channel in the nascent structure by an export apparatus that is believed to be located within an annular pore in the basal body MS ring (5, 8, 21). The export apparatus consists of six integral membrane components (FlhA, FlhB, FliO, FliP, FliQ, and FliR) and three cytoplasmic components (FliH, FliI, and FliJ) (15, 16). Export of bacterial flagellar proteins has characteristics in common with type III secretion of virulence factors by pathogenic bacteria (1, 7, 10, 11).

FliI is a flagellum-specific ATPase, which converts the energy of ATP hydrolysis into the energy for flagellar protein export (4, 16-18, 20, 23). FliH is a regulatory protein that is thought to prevent FliI from hydrolyzing ATP until the energy can be used for export (2, 6, 13, 16). FliJ functions as a general chaperone that prevents export substrates from premature aggregation in the cytoplasm (12).

A tentative model for the flagellar export process has been proposed (16, 17, 26) in which a (FliH)2/FliI heterotrimeric complex (16), FliJ, and substrate diffuse to the cytoplasmic domains of FlhA and FlhB and form a complex. ATP hydrolysis by FliI drives export substrate translocation through the export apparatus, placing the substrate in the channel from whence it diffuses to its final assembly destination.

In the present study, we have found that overproduction of FliI and also certain second-site mutations in flhA and flhB are capable of conferring considerable export capability and motility to a fliH null mutant.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1 and shown graphically in Fig. 1. Luria-Bertani broth, soft tryptone-agar plates, and M9-Casamino Acids medium plus 1% glycerol were prepared as previously described (15).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli strains | ||

| NovaBlue | Recipient for cloning experiments | Novagen |

| BL21(DE3)/pLysS | Overproduction of proteins | Novagen |

| HMS174(DE3)/pLysS | Overproduction of proteins | Novagen |

| Salmonella strains | ||

| JR501 | For converting E. coli plasmids to Salmonella compatibility | 19 |

| KK1013 | Deletion of region III | 9 |

| MKM11 | ΔfliH | 6 |

| MKM11gK | ΔfliH flgK::Tn10; defective in region I | This study |

| MKM11hB | ΔfliH flhB::Tn10; defective in region II | This study |

| MMA10xx series | ΔfliH flhA pseudorevertants from MKM11 | This study |

| MMA11xx series | flhA second-site mutants from corresponding MMA10xx strain | This study |

| MMB10xx series | ΔfliH flhB pseudorevertants from MKM11 | This study |

| MMB11xx series | flhB second-site mutants from corresponding MMB10xx strain | This study |

| SJW1103 | Wild-type strain for motility and chemotaxis | 25 |

| SJW2936 | Deletion of region II | 22 |

| SJW1429 | fliH | 15 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pET19b | Vector | Novagen |

| pTrc99A | Vector | Pharmacia |

| pMM310 | pET19b/His-FliHa | 17 |

| pMM306 | pTrc99A/His-FliH | 17 |

| pMM405 | pET19b/His-FliJa | 17 |

| pMM406 | pTrc99A/His-FliJ | 17 |

| pMM1701 | pET19b/His-FliIa | 17 |

| pMM1702 | pTrc99A/His-FliI | 17 |

| pMM1704 | pTrc99A/His-FliI(R7C/L12P) | 16 |

| pMM1706 | pTrc99A/His-FliI(K188I) | 16 |

| pMM1708 | pTrc99A/His-FliI(Y363S) | 16 |

| pBGtI(Δ1-7) | pTrc99A/His-FliI(Δ1-7)b | This study |

| pBGtICAT | pTrc99A/His-FliICAT | This study |

| pIFF700 | pTrc99A/His-FLAG-FliI | 4 |

| pIFF7001, etc. | pTrc99A/His-FLAG-FliIΔ1, etc. | Fan Fan, unpublished |

Although in many cases we made pET19b-based versions of plasmids, we include in the table only those encoding the wild-type alleles of FliH, FliI, and FliJ.

FliI(Δ1-7) was obtained in a previous study (18) as a clostripain proteolysis fragment with an apparent mass of 48 kDa and was given the name FliICL48 in that paper. The N-His-tagged version of FliICL48 in the present paper has been given the more descriptive name His-FliI(Δ1-7).

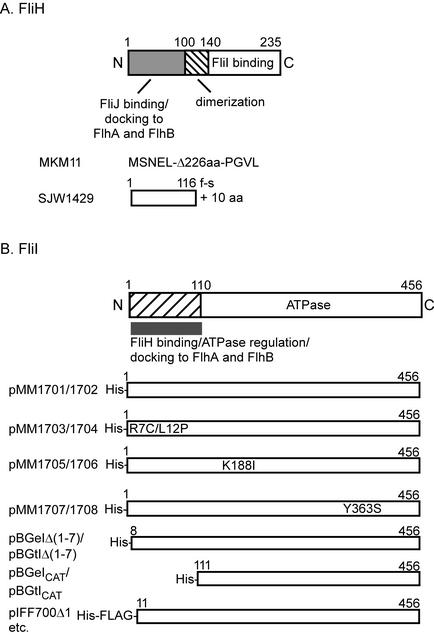

FIG. 1.

(A) The primary structure of the ATPase regulatory protein FliH and schematic representation of mutant FliH proteins produced by MKM11 and SJW1429. FliH is a 235-amino-acid protein that can be roughly divided into three regions: an N-terminal region consisting of the first 100 amino acids, a middle region containing amino acid residues 101 to 140, and a C-terminal region comprising the remainder of the protein. The N-terminal region, middle, and C-terminal regions are essential for interaction with FliJ, for dimerization, and for interaction with FliI, respectively. (B) The primary structure of the flagellum-specific ATPase FliI and schematic representations of the FliI products produced by the plasmids listed in Table 1.

Effects of overproduction of FliI and FliJ on motility and flagellar protein export of a fliH null mutant.

A Salmonella fliH null mutant MKM11 (6) has the sequence MSNEL-Δ226-PGVL, i.e., it contains only nine amino acid residues of FliH (Fig. 1A). It displays a leaky motile phenotype, indicating that substrate export still occurs with low probability in the absence of FliH. We transformed the null mutant with plasmids encoding the soluble export components FliH, FliI, and FliJ and examined the transformants for swarming ability (Fig. 2A). FliH complemented the mutant. FliI overproduced from a pTrc99A-based plasmid restored motility to a considerable degree. When produced from a pET19b-based plasmid, which has low expression levels in a non-T7 host, FliI did not restore motility. Plasmids encoding FliJ did not restore motility. Both FliI and FliJ were detected at similar cellular levels (measured as described previously [17]) when produced from pTrc99A-based plasmids (Fig. 2B), indicating that the failure of FliJ to bypass the fliH null mutation was not a result of failure of expression.

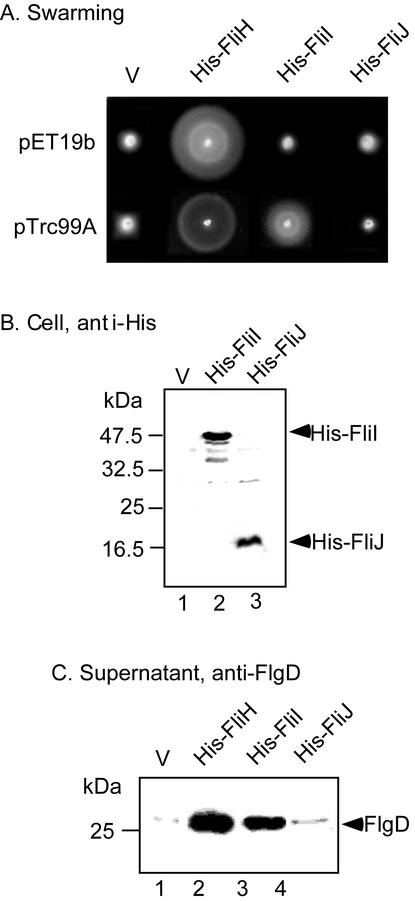

FIG. 2.

(A) Swarming of the fliH null mutant with pET19b-based and pTrc99A-based plasmids encoding the proteins shown. V, vector. Plates were incubated for 4.5 h at 30°C. (B) Immunoblot, using anti-His antibody, of whole cells of the fliH null mutant transformed with plasmids encoding the proteins shown. (C) Immunoblot, using polyclonal anti-FlgD antibody, of the hook-capping protein FlgD in culture supernatants of the fliH mutant transformed with plasmids encoding the proteins indicated. Cellular levels of FlgD were the same in all cases (data not shown).

The improvement in motility of the null mutant upon overproduction of FliI was, as expected, a consequence of restoration of flagellar protein export. We used the hook-capping protein FlgD as an example (Fig. 2C) (17). Small amounts of FlgD were detected with vector controls, presumably because of the leaky motile phenotype of the null mutant.

Effects of overproduction of point mutant variants of FliI on the motility and export capability of the fliH null mutant.

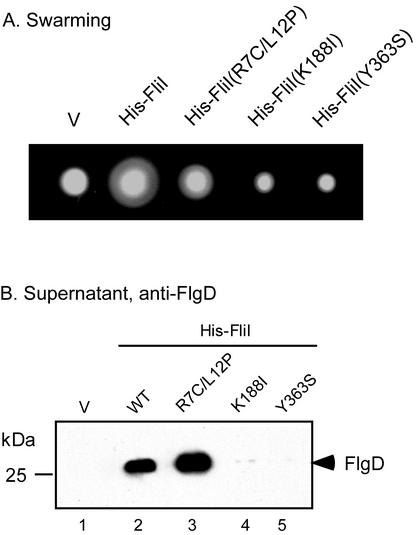

FliI(K188I) and FliI(Y363S) (3, 4) (Fig. 1B), whose mutations lie within the ATPase catalytic domain, have 1% and 2% of wild-type ATPase activity, respectively, and retain the ability to form a FliH/FliI complex, while FliI(R7C/L12P) has an ATPase activity twice that of wild-type but does not form the complex (16). FliI(R7C/L12P) produced from pTrc99A was able to significantly bypass the motility defect of the fliH null mutant (Fig. 3A). Plasmids encoding catalytic variants of FliI failed to bypass the motility defect of the fliH null mutant. Consistent with the motility data, FlgD was strongly detected in the culture supernatants of the fliH null mutant transformed with pTrc99A-based plasmids producing wild-type FliI or FliI(R7C/L12P) but was detected weakly or not at all with the plasmids encoding catalytic variants of FliI (Fig. 3B). Failure to bypass was not a consequence of protein instability, since all mutant derivatives of FliI were detected at the same level as the wild type (data not shown) (using anti-His [Qiagen] antibody [15]).

FIG. 3.

(A) Swarming of the fliH null mutant transformed with plasmids encoding the point mutant FliI variants shown. Plates were incubated for 4.5 h at 30°C. (B) Immunoblot, using anti-FlgD antibody, of the culture supernatant fractions of the fliH null mutant transformed with plasmids encoding the point mutant FliI variants shown. V, vector.

Effects of overproduction of truncated variants of FliI on the motility of the fliH null mutant.

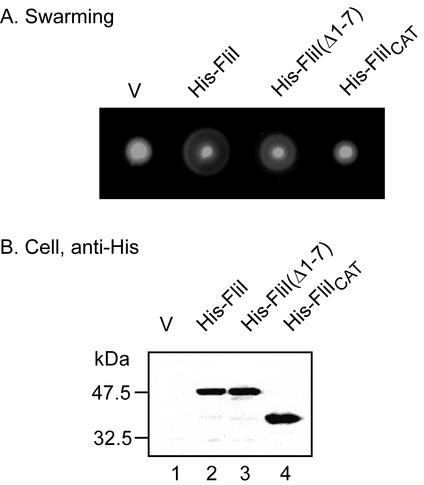

In a previous study (18), it was demonstrated that a proteolytic fragment of FliI lacking the first seven amino acids failed to bind FliH. To examine the ability of N-terminally truncated versions of FliI to restore the motility of the fliH null mutant, we constructed His-FliI(Δ1-7) (lacking the first seven amino acids) and also His-FliICAT (lacking the first 110 amino acids and so consisting solely of the catalytic domain) (Fig. 1B). Neither could form a stable FliH/FliI complex (data not shown). However, FliI(Δ1-7) was able to substantially bypass the motility defect of the fliH null mutant, whereas FliICAT was not (Fig. 4A). Likewise, FliI(Δ1-7) restored the export of FlgD, whereas FliICAT did not (data not shown). Immunoblotting with anti-His antibody revealed that both truncated forms of FliI were present at wild-type levels (Fig. 4B). We purified His-FliI, His-FliI(Δ1-7), and His-FliICAT by nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid chromatography as previously described (17) and measured their ATPase activities using a malachite green assay (16). The ATPase activities of FliI(Δ1-7) and FliICAT were 6 and 29% of that of wild-type FliI. Thus, even though FliI(Δ1-7) was less catalytically active than FliICAT, this difference was less important for the bypass phenomenon than the presence of an almost intact N-terminal region.

FIG. 4.

(A) Swarming of the fliH null mutant transformed with pTrc99A-based plasmids encoding the truncation variants of FliI shown (see Fig. 1B). Plates were incubated for 4.5 h at 30°C. (B) Immunoblot, using anti-His antibody, of whole-cell proteins of the fliH null mutant transformed with the same plasmids as in panel A. V, vector.

Effects of overproduction of scanning amino acid deletion variants of FliI.

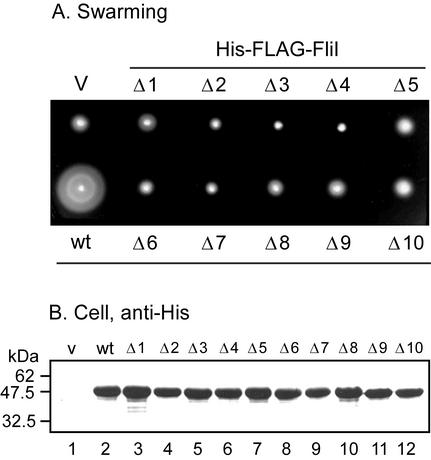

A series of plasmids encoding N-terminally His-FLAG-tagged FliI variants with scanning 10-amino-acid deletions throughout its N-terminal region had been constructed (4) (F. Fan, unpublished data) (Fig. 1B). None were able to bypass the motility defect of the fliH null mutant (Fig. 5A). All of the deletion variants were stable (Fig. 5B). Thus, the conclusion based on the truncated variants (Fig. 4) remains valid, namely, that the N-terminal region of FliI is essential for the bypass effect.

FIG. 5.

(A) Swarming of the fliH null mutant transformed with pTrc99A-based plasmids encoding 10-amino-acid deletion derivatives of FliI. Plates were incubated for 5 h at 30°C. V, vector. (B) Immunoblot, using anti-His antibody, of whole-cell proteins of HMS174(DE3)pLysS transformed with the same plasmids as in panel A.

ATPase activity measurements were made on purified His-FLAG-FliIΔ1 and His-FLAG-FliIΔ2 (the other deletion variants were too insoluble to permit them to be assayed). Their activities were about 3 and 50%, respectively, of that of wild-type His-FLAG-FliI.

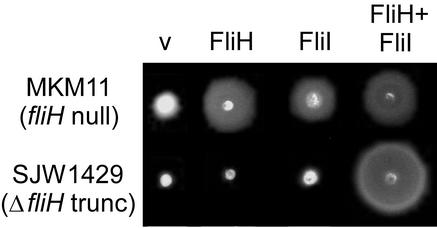

Effect of overproduction of FliH and FliI on the motility of a fliH truncation mutant strain, SJW1429.

Strain SJW1429 (Fig. 1A) is a fliH mutant that is totally immotile and so is phenotypically more defective than the genotypically null strain MKM11. From previous studies (6), we can conclude that the mutant FliH in SJW1429 retains the FliJ binding domain but lacks about half of its dimerization domain and the entire FliI binding domain.

SJW1429 cannot be complemented by overproduction of FliH (Fig. 6), suggesting that the truncated form is dominant negative. Overproduction of FliI also does not result in motility; thus, the C-terminally truncated FliH protein appears to interfere with the bypass effect of overproducing FliI, possibly by interfering with FliI binding to FlhA or FlhB. If both FliH and FliI are overproduced, however, SJW1429 becomes motile, indicating that the wild-type FliH/FliI complex is functional even in the presence of the truncated form. We suggest that this latter phenomenon represents complementation and not bypass.

FIG. 6.

Swarming of the fliH null mutant MKM11 and the fliH frameshift mutant SJW1429 (see Fig. 1B) transformed with pTrc99A-based plasmids encoding His-FliH, His-FliI, and His-FliH plus His-FliI. v, vector. Plates were incubated for 4.5 h at 30°C.

Isolation of pseudorevertants of the fliH null strain.

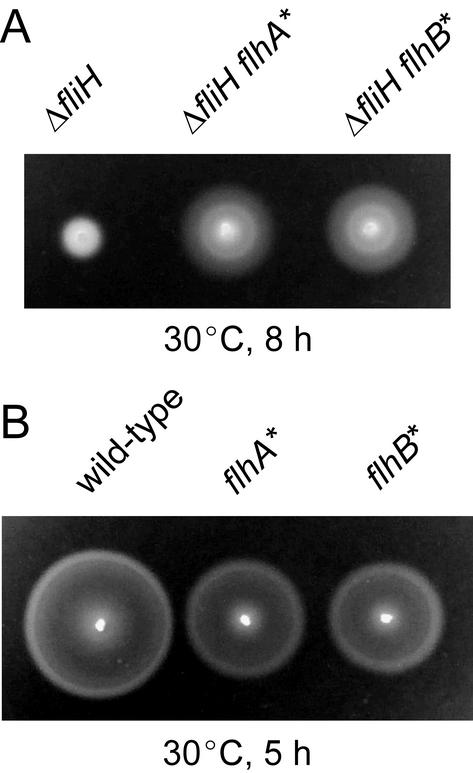

When the fliH null mutant was streaked from an overnight culture onto soft tryptone-agar plates and incubated at 30°C for 2 days, small swarms were found emerging from the broad streak generated by the weak motility of MKM11. Thirteen motile colonies were purified from such swarms. These pseudorevertants, illustrated by MMA1002 and MMB1005, swarmed considerably better than the null mutant (Fig. 7A), although not as well as the wild-type strain SJW1103 (Fig. 7B). Consistent with this, FlgD was detected in the culture supernatant from the pseudorevertants, although in much smaller amounts than with the wild-type strain (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

(A) Swarming of MKM11 (ΔfliH) and pseudorevertants MMA1002 (ΔfliH flhA*) and MMB1005 (ΔfliH flhB*). (B) Swarming of SJW1103 (wild type) and second-site mutants MMA1102 (flhA*) and MMB1105 (flhB*). The plates were incubated at 30°C for the times indicated.

To determine the location of the mutations in terms of the major flagellar regions I, II, and IIIa,b (11), transductional crosses were carried out with phage P22HTint as described previously (24). P22 lysates were propagated on 13 pseudorevertants and transduced into strains defective in each of the major regions (Table 1). A large number of abortive transductants (trails) appeared when MKM11hB was used as a recipient; in contrast, no trails were produced when MKM11gK or KK1013 was used (data not shown). Thus, the mutations apparently lay in region II and might be closely linked to the flhB operon, which consists of 3 genes, flhB, flhA, and flhE (14). FlhB and FlhA are integral membrane components of the export apparatus; the role of FlhE is not known.

DNA sequence analysis established that the mutations were in flhA and flhB. They were all missense mutations: I21T, L22F (seen four times), and V404M in FlhA and P13T, A21V, A21T (seen twice), and I27N in FlhB. All of these except FlhA(V404M) lie near the N termini of the two proteins, close to the interface with the first membrane span. FlhA(V404M) lies in the cytoplasmic C-terminal domain of the protein.

The second-site mutations from a set of the pseudorevertants were transferred by P22 phage-mediated transduction into SJW2936 (deletion of region II) to construct strains containing only the second-site mutations. These strains, illustrated by MMA1102 and MMB1105 (Fig. 7B), swarmed less well than the wild-type strain, although much better than the pseudorevertants (Fig. 7A). In agreement with this, the level of FlgD was found to be slightly lower in the culture supernatants of second-site flhA and flhB mutants than in the culture supernatants of wild-type cells (data not shown). Thus, in the presence of wild-type FliH, the second-site flhA and flhB mutations impair flagellar protein export to a small degree.

Effects of overproduction of FliI on the motility of pseudorevertants and the second-site flhA and flhB mutants.

We examined whether overproduction of FliI enhanced the motility of the pseudorevertants and the second-site mutants. The swarm sizes of pseudorevertants overproducing wild-type FliI were substantially larger than those of cells harboring the pTrc99A vector alone (data not shown). Thus, the bypass effect still operates with the pseudorevertants. In contrast, overproduction of His-FliI had no effect on the swarm sizes of the flhA and flhB second-site mutants.

Bypass of FliH.

In this study, we have investigated effects of overproduction of soluble components of the type III flagellar export apparatus on both the motility and flagellar protein export properties of a Salmonella fliH null mutant, MKM11. Overproduction of FliI, but not of FliJ, resulted in bypass of the fliH null mutation with respect to both export and motility. Both the catalytic domain and the flagellum-specific N-terminal domain of FliI were necessary for this effect. The motility defect of the fliH null mutant could also be bypassed by certain mutations in the flhA and flhB genes, whose gene products are integral membrane components of the type III flagellar export apparatus. The simplest explanation for these results is that excess FliI avoids the need for subtle regulation by FliH and that FlhA and FlhB can be altered in certain ways that permit tighter binding of FliI. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that the two bypass processes operate by different mechanisms.

Based on the absence of a bypass effect with FliJ, it seems unlikely that overproduction of FliI results in an increase in formation of a putative FliI/FliJ complex. Therefore, we hypothesize that overproduction of FliI increases the probability of its productive interaction with the integral membrane components of the export apparatus.

The fliH null mutant displays a leaky motile phenotype, indicating that FliH is not absolutely essential for flagellar protein export (6). However, since FliI alone, even when overproduced, does not support motility as well as the FliH/FliI complex, we propose that FliH plays an important role in the effective docking of FliI to the export apparatus to enable the energy of ATP hydrolysis to be usefully coupled to the translocation of export substrates.

Unlike wild-type FliI, FliI(R7C/L12P) and FliI with truncation of only the first seven amino acids at the N terminus fail to make a complex with FliH (16, 18). However, overproduction of His-FliI(R7C/L12P) and His-FliI(Δ1-7) still overcame the absence of FliH in MKM11 (Fig. 3 and 4), and pTrc99A-based plasmids encoding them complemented a fliI mutant to some degree (data not shown). This suggests that even though they cannot make a stable complex with FliH when it is present, both of them retain the ability to interact with the export apparatus when FliH is absent. We propose that the N-terminal flagellum-specific region of FliI is responsible for the docking to the export apparatus (Fig. 1B) as well as for its interaction with FliH (16).

Overproduction of FliI fails to enhance the motility of SJW1429, which produces the first 116 amino acids of FliH along with some frame-shifted residues, indicating that C-terminally truncated FliH interferes with the bypass ability of FliI. We have shown previously that FliH proteins containing 10-amino-acid deletions in the middle and C-terminal regions cannot form a stable complex with FliI and exert a strong dominant-negative effect on the motility of the wild-type strain (6). Therefore, we propose that the N-terminal region of FliH is responsible for association with the export apparatus as well as binding to FliJ (6).

Bypass of the fliH null mutation by mutations in flhA and flhB and the importance of their N-terminal cytoplasmic sequences.

Bypass mutations lie within flhA and flhB, whose gene products are integral membrane components of the type III flagellar export apparatus. Therefore, it is likely that of the integral membrane components of this apparatus, FlhA and FlhB are the ones that interact most directly with FliI. Bypass of the FliH defect occurs even at chromosomal levels of expression of fliI, suggesting that conformational changes have occurred within FlhA and FlhB that result in an increase in their binding affinity for FliI.

FlhA and FlhB are integral membrane proteins consisting of 692 and 383 amino acid residues, respectively (14), and both of them have large cytoplasmic C-terminal domains. None of the bypass mutations lie deep within their transmembrane domains. In fact, all but one lie in the short N-terminal cytoplasmic sequences of the two proteins, at or close to the beginning of the first transmembrane span. These N-terminal cytoplasmic sequences must therefore be involved in the interaction with FliI.

The second-site mutant strains swarm better than the pseudorevertants. However, they do not swarm as well as the wild type (Fig. 7). This suggests that these N-terminal mutations in FlhA and FlhB, while beneficial in terms of binding of FliI in the absence of FliH, actually reduce binding to the wild-type FliH/FliI complex to some degree.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Shigeru Yamaguchi for providing SJW2936 and phage P22HTint, Kouhei Ohnishi for providing polyclonal anti-FlgD antibody, and Fan Fan for construction of the FliI deletion plasmids.

This work has been supported by USPHS grant AI12202 to R.M.M. and by a postdoctoral fellowship from Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT) (to B.G.P.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aizawa, S.-I. 2001. Bacterial flagella and type III secretion systems. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 202:157-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auvray, F., A. J. Ozin, L. Claret, and C. Hughes. 2002. Intrinsic membrane targeting of the flagellar export ATPase FliI: interaction with acidic phospholipids and FliH. J. Mol. Biol. 318:941-950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dreyfus, G., A. W. Williams, I. Kawagishi, and R. M. Macnab. 1993. Genetic and biochemical analysis of Salmonella typhimurium FliI, a flagellar protein related to the catalytic subunit of F0F1 ATPase and to virulence proteins of mammalian and plant pathogens. J. Bacteriol. 175:3131-3138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fan, F., and R. M. Macnab. 1996. Enzymatic characterization of FliI: an ATPase involved in flagellar assembly in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Biol. Chem. 271:31981-31988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan, F., K. Ohnishi, N. R. Francis, and R. M. Macnab. 1997. The FliP and FliR proteins of Salmonella typhimurium, putative components of the type III flagellar export apparatus, are located in the flagellar basal body. Mol. Microbiol. 26:1035-1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.González-Pedrajo, B., G. M. Fraser, T. Minamino, and R. M. Macnab. 2002. Molecular dissection of Salmonella FliH, a regulator of the ATPase FliI and the type III flagellar protein export pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 45:967-982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hueck, C. J. 1998. Type III protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of animals and plants. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:379-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kihara, M., T. Minamino, S. Yamaguchi, and R. M. Macnab. 2001. Intergenic suppression between the flagellar MS ring protein FliF of Salmonella and FlhA, a membrane component of its export apparatus. J. Bacteriol. 183:1655-1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kutsukake, K., Y. Ohya, S. Yamaguchi, and T. Iino. 1988. Operon structure of flagellar genes in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Gen. Genet. 214:11-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macnab, R. M. 1999. The bacterial flagellum: reversible rotary propellor and type III export apparatus. J. Bacteriol. 181:7149-7153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macnab, R. M. 1996. Flagella and motility, p. 123-145. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 12.Minamino, T., R. Chu, S. Yamaguchi, and R. M. Macnab. 2000. Role of FliJ in flagellar protein export in Salmonella. J. Bacteriol. 182:4207-4215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minamino, T., B. González-Pedrajo, K. Oosawa, K. Namba, and R. M. Macnab. 2002. Structural properties of FliH, an ATPase regulatory component of the Salmonella type III flagellar export apparatus. J. Mol. Biol. 322:281-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minamino, T., T. Iino, and K. Kutsukake. 1994. Molecular characterization of the Salmonella typhimurium flhB operon and its protein products. J. Bacteriol. 176:7630-7637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minamino, T., and R. M. Macnab. 1999. Components of the Salmonella flagellar export apparatus and classification of export substrates. J. Bacteriol. 181:1388-1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minamino, T., and R. M. Macnab. 2000. FliH, a soluble component of the type III flagellar export apparatus of Salmonella, forms a complex with FliI and inhibits its ATPase activity. Mol. Microbiol. 37:1494-1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minamino, T., and R. M. Macnab. 2000. Interactions among components of the Salmonella flagellar export apparatus and its substrates. Mol. Microbiol. 35:1052-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minamino, T., J. R. H. Tame, K. Namba, and R. M. Macnab. 2001. Proteolytic analysis of the FliH/FliI complex, the ATPase component of the type III flagellar export apparatus of Salmonella. J. Mol. Biol. 312:1027-1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryu, J., and R. J. Hartin. 1990. Quick transformation in Salmonella typhimurium LT2. BioTechniques 8:43-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silva-Herzog, E., and G. Dreyfus. 1999. Interaction of FliI, a component of the flagellar export apparatus, with flagellin and hook protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1431:374-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki, H., K. Yonekura, K. Murata, T. Hirai, K. Oosawa, and K. Namba. 1998. A structural feature in the central channel of the bacterial flagellar FliF ring complex is implicated in type III protein export. J. Struct. Biol. 124:104-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Togashi, F., S. Yamaguchi, M. Kihara, S.-I. Aizawa, and R. M. Macnab. 1997. An extreme clockwise switch bias mutation in fliG of Salmonella typhimurium and its suppression by slow-motile mutations in motA and motB. J. Bacteriol. 179:2994-3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vogler, A. P., M. Homma, V. M. Irikura, and R. M. Macnab. 1991. Salmonella typhimurium mutants defective in flagellar filament regrowth and sequence similarity of FliI to F0F1, vacuolar, and archaebacterial ATPase subunits. J. Bacteriol. 173:3564-3572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamaguchi, S., S.-I. Aizawa, M. Kihara, M. Isomura, C. J. Jones, and R. M. Macnab. 1986. Genetic evidence for a switching and energy-transducing complex in the flagellar motor of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 168:1172-1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamaguchi, S., H. Fujita, K. Sugata, T. Taira, and T. Iino. 1984. Genetic analysis of H2, the structural gene for phase-2 flagellin in Salmonella. J. Gen. Microbiol. 130:255-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu, K., B. González-Pedrajo, and R. M. Macnab. 2002. Interactions among membrane and soluble components of the flagellar export apparatus of Salmonella. Biochemistry 41:9516-9524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]