Abstract

Summary

Tobacco smoke and polluted environments substantially increase the lung burden of pneumotoxic chemicals, particularly pneumotoxic metallic elements. To achieve a better understanding of the early events between exposure to inhaled toxicants and the onset of adverse effects on the lung, the characterization of dose at the target organ would be extremely useful. Exhaled breath condensate (EBC), obtained by cooling exhaled air under conditions of spontaneous breathing, is a novel technique that could provide a non-invasive assessment of pulmonary pathobiology. Considering that EBC is water practically free of interfering solutes, it represents an ideal biological matrix for elemental characterization. Published data show that several toxic metals and trace elements are detectable in EBC, raising the possibility of using this medium to quantify the lung tissue dose of pneumotoxic substances. This novel approach may represent a significant advance over the analysis of alternative media (blood, serum, urine, hair), which are not as reliable (owing to interfering substances in the complex matrix) and reflect systemic rather than lung (target tissue) levels of both toxic metals and essential trace elements. Data obtained among workers occupationally exposed to either hard metals or chromium (VI) and in smokers with or without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are reviewed to show that – together with biomarkers of exposure – EBC also allows the simultaneous quantification of biomarkers of effect directly sampled from the epithelial lining fluid, thus providing novel insights on both kinetic and dynamic aspects of metal toxicology.

Riassunto

«Recenti sviluppi nel biomonitoraggio umano: valutazione non invasiva della dose a livello dell’organo bersaglio e degli effetti pneumotossici». L’esposizione cronica a fumo di tabacco ed ad altri inquinati ambientali determina un accumulo polmonare di sostanze pneumotossiche, soprattutto metalli. Allo scopo di ottenere una migliore comprensione dei meccanismi attraverso i quali i tossici inalati inducono un danno polmonare, la valutazione della dose a livello dell’organo bersaglio, in questo caso il polmone, potrebbe essere molto utile. Il condensato dell’aria espirata (CAE) è un fluido ottenuto raffreddando l’aria esalata durante la respirazione a volume corrente ed è una nuova tecnica che può fornire una valutazione della patobiologia polmonare. Il CAE è formato quasi completamente da acqua, quindi rappresenta una matrice biologica ideale per la determinazione d’elementi metallici. Dati presenti in letteratura dimostrano come nel CAE si possono dosare vari metalli tossici ed elementi di transizione, permettendo quindi di proporre questa matrice per la quantificazione della dose al bersaglio di sostanze pneumotossiche. La quantificazione della dose al bersaglio consente di avere informazioni aggiuntive rispetto a quelle ottenute con i tradizionali metodi di monitoraggio biologico in lavoratori esposti, che generalmente consentono di stimare la dose sistemica, ma non l’esposizione delle vie respiratorie ad inquinanti aerodispersi né la frazione trattenuta nel polmone, verosimilmente implicata nella patologia infiammatoria e degenerativa a livello polmonare. In questa breve rassegna sono discussi i dati ottenuti in lavoratori professionalmente esposti a metalli duri ed in fumatori con o senza bronco-pneumopatica cronica ostruttiva (BPCO), per mostrare come il CAE – oltre agli indicatori di esposizione – consente di valutare indicatori di effetto campionati direttamente dal film che riveste le vie respiratorie, fornendo quindi nuovi spunti per meglio comprendere sia gli aspetti cinetici che quelli dinamici della tossicologia dei metalli.

Keywords: Metals, biomonitoring, lung, exhaled breath condensate

Introduction

Patophysiological events at pulmonary level can be identified relying on more or less invasive techniques, such as bronchoscopy and induced sputum. These sampling methods have allowed understanding of some of biological mechanisms in pulmonary diseases, and still represent reference techniques (7). Their invasiveness is a limiting factor precluding extensive application to clinic routine. More importantly, the associated inflammatory reaction (4) seems to limit the comparability between subsequent sampling times, thus preventing their use for monitoring purposes, which remains the most relevant approach to the use of biomarkers both in epidemiological and clinical settings.

Breath analysis appears to be promising to identify new biomarkers of processes involving the lung. In the last decade, there has been an increased application of exhaled breath analysis in pulmonology research, considering both exhaled gases and exhaled condensate (8). Exhaled breath analysis has enormous potential as an easy, non invasive means of monitoring inflammation and oxidative stress in the airways, particularly in non diseased subjects. Exhaled air can be collected without the need of unpleasant stimulation of the airways as in sputum induction or lavage sampling.

Whereas exhaled air has been examined for long time to measure volatile organic compounds in subjects exposed to airborne pollutants in either occupational or environmental settings (18, 29), exhaled breath condensate (EBC) is a relatively unexplored biological medium that could provide an assessment of lung pathobiology (19). The interest in EBC is justified by the fact that its collection is totally non invasive and does not cause any discomfort or risk to examined subjects (8).

EBC, which is obtained cooling exhaled breath during tidal breathing, is composed essentially of water, but it also contains slightly volatile and non volatile compounds which are expired as a bio-aerosol. Bio-aerosols consist of small droplets joining the vapour stream during its passage over the mucous layer lining the lung (12).

Different molecules have been found and quantified in EBC, including hydrogen peroxide, lipid peroxidation products, prostaglandins, leukotrienes and cytokines (21). Owing to its lack of invasiveness, EBC could be particular suitable in risk assessment, where much of the clinical evaluations are performed in presumably healthy subjects. In addition, due to the fact that inhaled toxics can act locally on the lung, a technique allowing for the sampling of pulmonary fluids would be helpful to characterize the dose delivered to the lung, when it represents the target organ for inhaled toxic chemicals.

EBC collection is also suitable to assess biomarkers of local inflammation and oxidative stress, which may be sensitive endpoints for identifying early biochemical changes in the airways occurring in exposed subjects. This approach will probably overcome the limitations of traditional spirometric tests, which often indicate late and frequently irreversible lung dysfunctions.

As EBC mainly consists of water that is practically free of potentially interfering solutes, it is an ideal biological fluid for elemental determinations; EBC elemental analysis may be used to assess target tissue levels of pneumotoxic metals and essential trace elements, and hence the probability of local effects resulting from highly reactive or poorly soluble species retained by the lung for long time.

Mechanisms leading to EBC formation

Exhaled air is almost in equilibrium with water vapour at the body temperature. Owing to the very large surface area of the lungs, approximately 400 ml of water are lost by evaporation each day. Because the saturation of the exhaled air is nearly complete, the rate of ventilation effectively determines the amount of water lost from the lungs, which is relevant for airway heat transfer (5).

Exhaled water vapour condenses onto a surface when that surface is cooler than its temperature. Therefore, EBC consists almost completely of condensed water vapour. Water vapour does not behave as a solvent of non-volatile solutes, but rather it acts as a vehicle of exhaled molecules joining the vapour stream. Non-volatile molecules are expired as small particles, which are aerosolized and dispersed into condensed water vapour. These particles could be formed at a variety of sites, including the airways, upper respiratory tract, and even the upper gastrointestinal tract (13).

The number of detected exhaled particles during tidal breathing varies over a range from less than 0.1 to about 4 particles/cm3, with a mean diameter of particles less than 0.3 mm (12, 14, 28). It is assumed, but not still proved, that aerosol droplets are formed from the extra-cellular surface fluid layer by turbulent flow and airflow deviation in branching points of the bronchi and alveoli, and that the amount may depend on the current velocity of the passing air and the surface tension (12). There is no demonstration that exhaled particles formation is kept constant. This makes their expiratory excretion rate a stochastic phenomenon, whose variability depends on sampling time and conditions, rather than on physiologic determinants. The variable dilution of droplets seems to depend on ventilation (the main determinant of evaporation) and condensation temperature (15), which determines the efficiency of water collection.

The concept of target tissue dose of pneumotoxic substances

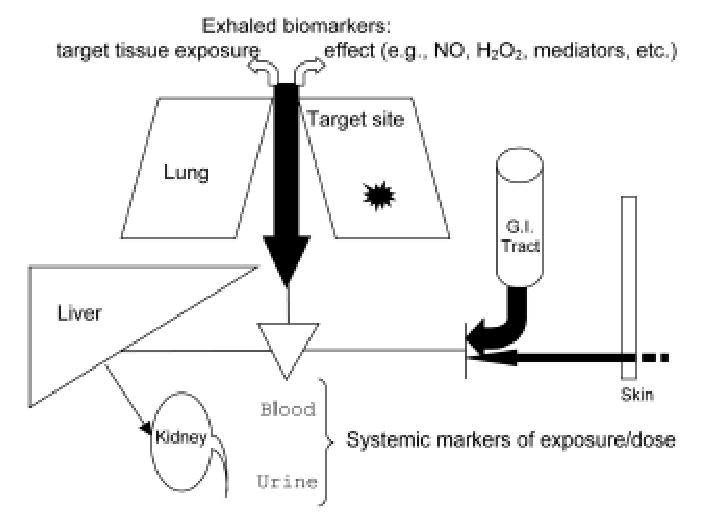

Traditional exposure biomarkers relying on the urinary or blood concentration of either the parent compound or its metabolite(s) cannot be applied for assessing exposure to substances that exhibit their toxicity at the sites of first contact (20). One may also wonder whether this applies to toxicants such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) and certain metallic elements for which the effect of main concern is localized at the site of first contact – i.e. COPD, lung fibrosis, lung cancer, etc. – when exposure occurs by inhalation. In such instances, it might be more appropriate to rely on markers that reflect the dose delivered to the respiratory tract, which does not necessarily correspond with the absorbed dose as assessed by “systemic” biomarkers such as blood and urinary concentrations (figure 1).

Figure 1.

The relevance of urinary or systemic biomarkers (protein or DNA adducts) to assess the risk of local effects associated with exposure to pneumotoxic substances might be questioned, as the retained dose responsible for local effects may not be correlated with absorbed dose, as measured using systemic markers either in blood or urine. (Adapted and modified after ref. 23)

The fraction of the dose absorbed by the digestive and/or percutaneous routes would indeed contribute little to the health effect of concern and, moreover, biotransformation capacities of the lung (locally) and the liver (systemically) are different. Therefore the relevance of urinary (e.g. 1-hydroxypyrene) or systemic biomarkers (protein or DNA adducts) to assess health risks associated with exposure to PAHs might be questioned. Although the contribution of percutaneous absorption of metallic elements is negligible and that occurring through the gastro-intestinal tract is limited for most metallic species polluting work environments (in most instances, only relatively large and poorly soluble particles are ingested), the systemic dose – as assessed relying on the blood and urinary concentration – may not be relevant to the risk assessment of pneumotoxicity. Indeed, for certain metallic elements, less soluble species are thought to be responsible for local effects (inflammation, cancer), whereas soluble compounds are readily taken up and excreted with urine. Efforts currently undertaken to assess the local dose to the respiratory tract will be shortly reviewed, including studies aimed at measuring the EBC concentration of toxic metallic elements in field studies on workers occupationally exposed to cobalt and tungsten, in chromeplaters exposed to hexavalent chromium (Cr VI) and in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Exhaled breath condensate in workers exposed to hard metals

Hard metals are widely used in different industries, mainly because of their resistance to corrosion, temperature, and wear. The most important use is as a component of alloys (cemented carbides) and the main components are tungsten carbide (about 90%)and cobalt (about 10%) (1).

Occupational exposure to Co can lead to various lung diseases, such as interstitial pneumonitis, fibrosis, and asthma (1). Although the mechanisms of Co-induced lung toxicity are not completely known, there is evidence from both in vivo and in vitro experiments supporting the view that Co induces the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) with subsequent oxidative stress (22). In addition, ROS generation by Co administration is significantly increased by co-exposure to W-C particles, through a physical-chemical mechanism of interaction (24).

Strict control of dust level and regular health monitoring are recommended for workers employed in the hard metal industry. Urinary Co excretion has been proposed as a biomarker of exposure because of its correlation with airborne Co concentration (1). However, this biomarker integrates the overall intake from different absorption routes (dermal and digestive routes) and can be used to assess the risk of systemic effects, rather than local effects on the respiratory tract.

In order to verify whether EBC may be employed for a better risk assessment among workers exposed to hard metals, we enrolled thirty-three workers exposed to Co and W in workshops producing either diamond tools or hard-metal mechanical parts (17).

Airborne levels of Co and W ranged from 0.1–37.4 and 0–4.9 mg/m3, respectively. Our data showed that Co and W levels are detectable in EBC at nmol/L levels and clearly distinguished between exposed and non exposed subjects. In addition, Co and W EBC levels were correlated with respective urinary levels but, most of all, EBC Co, but not urinary levels, are positively correlated with biomarker of lung damage, such as aldehydes derived from lipid peroxidation. This suggests that exhaled elements may reflect the lung dose responsible for local toxic effects. Furthermore, the relationship between Co levels in EBC and urine seems to indicate that Co in EBC really may represent the fraction of body dose (represented by Co in urine), which has been inhaled and has not yet moved from lung tissue in the systemic circulation at the sampling time.

Another interesting conclusion that can be drawn from our data is that EBC could be also used for a better understanding of the physical-chemical interactions between Co and W in vivo. In fact, when we looked at the interaction between Co in EBC and W in EBC in the ANCOVA model with aldehydes in EBC as a dependent variable, we verified that W exposure has a synergistic effect in vivo on Co pneumotoxicity. This is in agreement with published data obtained from in vitro experiments (24, 25). In fact, although W carbide alone is known to be inert, there is evidence suggesting that the physical-chemical association of Co and W carbide generates electrons (provided by Co and transferred on the surface of W carbide), which can reduce oxygen, thus giving rise to ROS.

This study demonstrated that Co and W can be measured in the EBC of occupationally exposed workers and that the levels of these elements in EBC correlate with a marker of oxidative stress, namely malondialdehyde (MDA), thus suggesting the potential use of this matrix as a novel approach to monitor target tissue dose and effects occurring in the respiratory tract upon exposure to pneumotoxic substances.

Exhaled breath condensate in workers exposed to chromium (VI)

The respiratory tract is the major target organ for Cr [for both valence states, trivalent Cr (Cr III) and hexavalent Cr (Cr VI)] following inhalation exposure in humans. Chronic inhalation exposure to Cr (VI) is much more toxic than Cr (III), for both acute (short-term) and chronic (long-term) exposures in humans (4, 11).

Exposure to Cr (VI) in humans results in effects on the respiratory tract, with perforations and ulcerations of the septum (although less frequent today, due to strict medical surveillance), bronchitis, decreased pulmonary function, pneumonia, asthma, and nasal itching and soreness (4). Therefore, strict control of dust level and regular health monitoring are recommended for workers employed in chrome industry (2). Of the occupational situations in which exposure to Cr occurs, the highest exposures to Cr may occur during chromate production, welding, chrome pigment manufacture, chrome plating and spray painting; highest exposures to other forms of Cr occur during mining, ferrochromium and steel production, welding and cutting and grinding of Cr alloys.

EBC may be a suitable matrix to assess respiratory health status in workers exposed to Cr, due to its ability to quantify lung tissue dose and consequent effects in exposed workers (6). We assessed 24 chrome-plating workers employed in a chrome plating plant both before and after the Friday working shift, and before the working shift on the following Monday. The aim of this study was the evaluation of Cr levels in the EBC and in urine, and the assessment of early biochemical changes in the airways by analyzing EBC biomarkers of oxidative stress, such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and MDA.

Ambient Cr levels were below the limit proposed by the ACGIH (3) for water soluble Cr(VI) organic compounds (50 μg/m3). Cr in EBC and Cr in urine were much higher in exposed subjects than in controls at all time points. EBC Cr levels increased from the beginning (5.3 μg/l) to the end of Friday (6.4 μg/l), but were considerably lower on Monday morning (2.8 μg/l). A similar trend was observed for EBC H2O2 (which increased from 0.36 μM to 0.59 μM on Friday, and was 0.19 μM on Monday morning) and EBC MDA levels (which increased from 8.2 nM to 9.7 nM on Fri-day, and were 6.6 nM on Monday). EBC Cr levels correlated with those of EBC H2O2 (r=0.54, p<0.01) and EBC MDA (r=0.59, p<0.01), as well as with urinary Cr levels (r=0.25, p<0.05).

Looking at the different correlations between variables, Cr in urine and Cr in EBC seem to provide different information: there were weak or no correlations between urinary Cr and biomarkers of free radical production, whereas Cr in EBC correlated with higher and significant r values with both MDA and H2O2 levels in EBC, thus suggesting that they may be more representative of the lung dose responsible for local free radical production.

EBC can be considered a promising medium for investigating both long-term and recent Cr exposure at target tissue level and, together with biomarkers of free radical production, it can provide insights into the oxidative lung interactions between pulmonary tissue and pneumotoxic metals occurring in exposed workers.

In a subsequent work (16), to better understand inhaled Cr toxicity and kinetic, metal speciation (aimed at distinguish Cr VI and Cr III) was also performed both in ambient air and in EBC. In fact, whereas it is usually assumed that only Cr III is detectable in urine, there are no data whether a similar behaviour occurs also in EBC. In fact, different individual concentration of reducing agents (glutathione, ascorbic acid) in lung lining fluid may affect Cr reduction and subsequent lung toxicity. EBC quantization of those reducing agents could also permit to identity susceptibility biomarkers implicated in pulmonary Cr toxicity. The study involved 10 workers employed in a chrome plating plant. Two EBC samples were collected: one immediately after the end of the work shift on Tuesday evening and the other before the beginning of the work shift on Wednesday morning, about 15 h after the last Cr exposure.

The main results of the study were that (i) it is possible to determine Cr(VI) in EBC and (ii) the fractional contribution of Cr(VI) to total Cr decreased over time from the last exposure, but was still detectable after 15 h from the last exposure, thus ruling out its meaning as a simple marker of environmental contamination. This time-dependent decrease can in fact only be explained as an interaction between inhaled Cr(VI) and the pulmonary lining fluid, with a consequent reduction to Cr(III). The persistence of Cr(VI) in EBC reinforces the idea that the lower airways are the main target of Cr(VI) toxicity, as assessed by exhaled biomarkers of effect. Inter-individual variability in Cr(VI)-reducing capability might represent an important component of host susceptibility.

Metallic elements in EBC from patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Exhaled elements were also assessed in patients with COPD, who were clinically stable at the time of the enrolment (26). The working hypothesis was that long term exposure to tobacco smoke (which is the most important factor leading to COPD) implies an increased lung uptake of toxic metals which, because of their stability, can also be used as tracers of environmental pollution. Lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), Cr, nickel (Ni), and aluminium (Al) have been identified as major contaminants in tobacco smoke. Of course, they are also major pollutants in relevant occupational settings. Their EBC concentration should provide a quantitative estimate of lung tissue burden following long term exposure.

Our data showed that current normal smokers exhibited higher exhaled levels of Pb and Cd than those observed in healthy nonsmoking subjects, probably reflecting active tobacco smoking habit. The expected effect of tobacco smoke on exhaled metal levels were also observed in smoking COPD patients, whose levels of exhaled toxic metals were higher than those observed in ex smokers with COPD. However, it is worth to note that ex smokers with COPD (who quitted smoking for more than 2 years) showed still higher levels of toxic metals in EBC (mainly Cd) than those observed in nonsmoking controls. This means that exhaled metal levels may also provide a measure of cumulative long-term exposure to tobacco smoke and environmental exposure to toxic metals.

Exhaled breath condensate analysis was also shown to be useful for the evaluation of biomarkers of lung effect in COPD patients (9, 10). In particular, we focused on biomarker of lipid peroxidation, because it is evident that cigarette smoke exposure results in lung oxidative stress, and the inflammatory process observed in patients with COPD results in disturbance of the oxidant–antioxidant balance (27). Our group developed a reliable method to assess different aldehydic products derived from lipid peroxidation, showing that MDA, hexanal, and heptanal, but not nonanal, were increased in EBC of patients with COPD in comparison to nonsmoking control subjects. Only MDA levels were increased in EBC of patients with COPD compared with smoking control subjects (10).

Conclusion

The results of these studies highlight the potential of EBC as a medium for assessing lung dose and effects after exposure to inhaled pneumotoxic substances. The integrated use of EBC and classic biological matrices such as urine and blood, which reflect systemic exposure, may therefore allow the fundamental completion of the biological monitoring of pneumotoxic compounds. However, it must be stressed that methodological issues regarding EBC collection and analysis still call for harmonization and standardization of procedures. Further studies of validation are necessary prior to a widespread application of EBC-based methods in occupational settings.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Heart, Blood and Lung Institute (NHLBI), Bethesda, MD, USA (grant R01 HL72323). The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NHLBI or the National Institutes of Health

References

- 1.A gency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry: Cobalt. Toxicological Profiles. Atlanta: ATSDR, 1999

- 2.A gency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry: Final Report of Toxicological profile for chromium Atlanta: ATSDR, 2000 [PubMed]

- 3.A merican Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygiene: Chromium. Documentation of the threshold limit values and biological exposure indices. Cincinnati: ACGIH, 1999

- 4.Antczak A, Kharitonov SA, Montuschi P, et al. Inflammatory response to sputum induction measured by exhaled markers. Respiration. 2005;72:s594–s599. doi: 10.1159/000086721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borok Z, Verkman AS. Lung edema clearance: 20 years of progress. Role of aquaporin water channels in fluid transport in lung and airways. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:s2199–s2206. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01171.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.C aglieri A, Goldoni M, Acampa O, et al: The effect of inhaled chromium on different exhaled breath condensate biomarkers among chrome-plating workers. Environ Health Perspect 2005, in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Caramori G, Pandit A, Papi A. Is there a difference between chronic airway inflammation in chronic severe asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;5:s77–s83. doi: 10.1097/00130832-200502000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corradi M, Mutti A. Exhaled breath analysis: from occupational to respiratory medicine. Acta Biomed Ateneo Parmense. 2005;76:s20–s29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corradi M, Pignatti P, Manini P, et al. Comparison between exhaled and sputum oxidative stress biomarkers in chronic airway inflammation. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:s1011–s1017. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00002404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corradi M, Rubinstein I, Andreoli R, et al. Aldehydes in exhaled breath condensate of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:s1380–s1386. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200210-1253OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Flora S. Threshold mechanisms and site specificity in chromium(VI) carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:s533–s541. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards DA, Man JC, Brand P, et al. Inhaling to mitigate exhaled bioaerosols. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:s17383–s17388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408159101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Effros RM, Su J, Casaburi R, et al. Utility of exhaled breath condensates in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a critical review. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2005;11:s135–s139. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200503000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiegel J, Clarke R, Edwards DA. Airborne infectious disease and the suppression of pulmonary bioaerosols. Drug Discov Today. 2006;11:s51–s7. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03687-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldoni M, Caglieri A, Andreoli R, et al. Influence of condensation temperature on selected exhaled breath parameters. BMC Pulmonary Medicine. 2005;5:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.G oldoni M, Caglieri A, Poli D, et al: Determination of hexavalent chromium in exhaled breath condensate and environmental air among chrome plating workers. Anal Chim Acta, in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Goldoni M, Catalani S, De Palma G, et al. Exhaled breath condensate as a suitable matrix to assess lung dose and effects in workers exposed to cobalt and tungsten. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:s1293–s1298. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon SM, Szidon JP, Krotoszynski BK, et al. Volatile organic compounds in exhaled air from patients with lung cancer. Clin Chem. 1985;31:s1278–s1282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holz O. Catching breath: monitoring airway inflammation using exhaled breath condensate. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:s371–s372. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00071305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoet P, Haufroid V. Biological monitoring: state of the art. Occup Environ Med. 1997;54:s361–s366. doi: 10.1136/oem.54.6.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horvath I, Hunt J, Barnes PJ, et al. ATS/ERS Task Force on Exhaled Breath Condensate. Exhaled breath condensate: methodological recommendations and unresolved questions. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:s523–s548. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00029705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lauwerys R, Lison D. Health risks associated with cobalt exposure-an overview. Sci Total Environ. 1994;150:s1–s6. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(94)90125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lison D. Importance of biotransformation pathways for interpreting biological monitorino of exposure. Toxicol Lett. 1999;108:s91–s97. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(99)00077-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lison D. Human toxicity of cobalt-containing dust and experimental studies on the mechanism of interstitial lung disease (hard metal disease) Crit Rev Toxicol. 1996;26:s585–s616. doi: 10.3109/10408449609037478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lison D, Carbonnelle P, Mollo L, et al. Physicochemical mechanism of the interaction between cobalt metal and carbide particles to generate toxic activated oxygen species. Chem Res Toxicol. 1995;8:s600–s606 J. doi: 10.1021/tx00046a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.M utti A, Corradi M, Goldoni M, et al. Exhaled metallic elements and serum pneumoproteins in asymptomatic smokers and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma. Chest, in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Nadeem A, Raj HG, Chhabra SK. Increased oxidative stress and altered levels of antioxidants in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Inflammation. 2005;29(suppl 1):23–32. doi: 10.1007/s10753-006-8965-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papineni RS, Rosenthal FS. The size distribution of droplets in the exhaled breath of healthy human subjects. J Aerosol Med. 1997;10:s105–s116. doi: 10.1089/jam.1997.10.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poli D, Carbognani P, Corradi M, et al. Exhaled volatile organic compounds in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: cross sectional and nested short-term follow-up study. Respir Res. 2005;6:71. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]