Abstract

Inflammatory infiltrates can modify (lipo)proteins via hypochlorous acid/hypochlorite (HOCl/OCl−) an oxidant formed by the myeloperoxidase-H2O2-halide system. These oxidatively modified proteins emerge in tubuli in some proteinuric and interstitial diseases. Human proximal tubular cells (HK-2) were used to confirm the hypothesis of detrimental and differential impact of HOCl-modified low density lipoprotein (HOCl-LDL), an in vivo occurring lipoprotein modification exerting proatherogenic and proinflammatory capacity. HOCl-LDL showed dose-dependent antiproliferative effects in HK-2 cells. Small dedicated cDNA macroarrays were used to identify differentially regulated genes. A rapid increase in the expression of genes involved in reactive oxygen species metabolism and cell stress, eg, heme oxygenase-1, thioredoxin reductase, cytochrome b5 reductase, Gadd 153, amino acid transporter E16, and HSP70 was found after HOCl-LDL treatment of HK-2 cells. In parallel, genes involved in tissue remodeling and inflammation eg, CTGF, VCAM-1, IL-1β, MMP7, and VEGF were up-regulated. Quantitative RT-PCR verified differential expression of a subset of these genes in microdissected tubulointerstitia from patients with acute tubular damage, progressive proteinuric renal disease, and membranous glomerulonephritis (with declining renal function), but not in stable patients with proteinuria caused by minimal change disease. The demonstration of selective up-regulation of a subgroup of genes if proteinuria is accompanied by the presence of HOCl-modified (lipo)proteins support the potential pathophysiological role of the myeloperoxidase-H2O2-halide system and HOCl-LDL in renal disease.

Proteinuria is a prominent feature of many renal diseases. This breakdown in glomerular permselectivity is accompanied by damage to the tubulointerstitial compartments in some, but not all proteinuric renal diseases. Proximal tubular epithelia are capable of reabsorbing limited amounts of filtered proteins without damaging effect; however, during proteinuria excessive plasma proteins, including lipoproteins, can gain access to the tubular structures. An increased load of plasma proteins on tubuli is considered to be an important component in the pathogenesis of tubulointerstitial inflammation, tubular atrophy, and interstitial scarring, although the underlying mechanisms why some, but not all, proteinuric diseases cause progressive renal damage remain largely unresolved at the cellular level.1–3

Glomerular diseases leading to proteinuria are often accompanied by intraglomerular and interstitial production of reactive oxygen species4 as a consequence of activation of infiltrating phagocytes and resident glomerular cells.5,6 Hypochlorous acid/hypochlorite (HOCl/OCl−) is the major oxidant generated only from H2O2 by myeloperoxidase (MPO) in the presence of physiological chloride concentrations.7 The predominant in vivo sources for MPO, released during the oxidative burst of activated phagocytes, are neutrophils and monocytes8 in which MPO makes up to 5% and 1%, respectively, of the total cell protein content. HOCl, an efficient microbicidal agent, is highly reactive with a broad range of biological molecules, eg, DNA, lipids, proteins, and lipoproteins, respectively.9–11

Glomerular structures and leaking plasma proteins can incur a change of their chemical and biological properties through reaction with HOCl.12–14 Immunohistochemical studies in human kidneys have demonstrated that epitopes modified by HOCl in vivo are present in differentiated and atrophic tubular epithelia in nephrosclerosis and acute interstitial nephritis, negative in control renal tissue, and only faintly present in minimal change disease (MCD).15 The release of reactive oxygen species also leads to modification of lipoproteins, which in turn, may exert adverse effects on glomerular function.16 Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) modified by HOCl (HOCl-LDL) displays a number of pathophysiological effects on phagocytes and vascular cells, contributing to the initiation and maintenance of the inflammatory response. HOCl-LDL causes foam cell formation9,17 and endothelial leakage and stimulates leukocyte adherence and emigration into the subendothelial space in vivo.18 HOCl-LDL initiates the respiratory burst of macrophages,19 inactivates lysosomal proteases,20 enhances neutrophil degranulation,21 and impairs nitric oxide biosynthesis.22

We hypothesized that HOCl-LDL may influence proximal tubular cells differently and more potently than native LDL by inducing a proinflammatory and fibrogenic state in tubular epithelia. For these studies, the proximal tubular epithelial cell line HK-2 was used as an in vitro model system.23 LDL was modified in vitro by HOCl at concentrations generated in vivo during inflammation.24

Gene expression patterns elicited in the cell culture model by LDL and HOCl-LDL were investigated using small dedicated DNA macroarrays containing genes that play roles in cellular stress and inflammation with the intention to identify a potential role for proximal tubular epithelia loaded with oxidatively modified proteins in tubulointerstitial scarring. The expression of the genes found increased in the in vitro study were then tested in vivo in microdissected human tubulointerstitial samples from kidney biopsies with proteinuria: MCD and membranous glomerulopathy, as well as from transplant (allograft) kidney biopsies showing acute tubulointerstitial damage (ATD).

The efficacy of using an in vitro model of LDL- and HOCl-LDL-mediated stress of cultivated renal tubular cells was verified by demonstrating that these lipoprotein particles elicit different responses on tubular cells. In addition, genes potentially involved in tubulointerstitial damage identified in the in vitro screen are up-regulated in the tubulointerstitium in patients with tubulointerstitial damage, but not in those with intact renal function and proteinuria.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Lipoproteins

The immortalized human proximal tubular cell line HK-223 (ATCC, Manassas, VA) was cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2 in keratinocyte serum free media (K-SFM, Gibco Life Technologies, Karlsruhe, Germany) supplemented with 5 ng/ml human recombinant epidermal growth factor and 0.05 μg/ml bovine pituitary extract. LDL was isolated by sequential ultracentrifugation of human plasma and modified by reagent NaOCl (oxidant to lipoprotein molar ratio of 400:1).25 Characterization of LDL and HOCl-LDL was performed as described.17,25 Lipoprotein concentrations are given as mg protein per ml medium. Before cell culture experiments, lipoproteins were dialyzed twice against a solution containing (0.64% Tris, 9.0% NaCl, 0.1% EDTA) for 5 hours at 4°C in darkness followed by dialysis against unsupplemented K-SFM overnight. Only lipoproteins dissolved in the unsupplemented K-SFM medium were applied to cell cultures in experiments described below.

Proliferation and Apoptosis Assay

HK-2 cells were grown in 24-well plates in supplemented K-SFM until a confluency of 80% was reached. Medium was changed to unsupplemented K-SFM for 24 hours to synchronize cells, and lipoproteins were subsequently added at indicated concentrations. After a 4-hour delay (methyl-[3H]thymidine (Amersham, Freiburg, Germany) was added at a specific activity of 1 μCi/ml. Twenty-four hours after the addition of lipoproteins, the medium was removed and the cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS. Ice-cold trichloroacetic acid (5%, w/v) was applied for 15 minutes and then removed. Cell lysis was performed by addition of 1 ml of NaOH (0.1 N) for 15 minutes; lysates were mixed with 9 ml of scintillation solution (Rotiszint Eco Plus, Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) and counted. The experiments were performed in triplicate.

Apoptosis rate was estimated by means of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase nick end labeling (TUNEL) using the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The experiment was performed in triplicate; in each experiment 300 cells were evaluated for a positive nuclear signal.

RNA Isolation and Reverse Transcription

To minimize variations of gene expression (independent of time- and concentration-dependent effects) experiments were performed with cells from the same passage, seeded at the same density on the same day. For each condition two P-10 Petri dishes were prepared. At 80% confluency, unsupplemented K-SFM was applied for 24 hours followed by addition of the corresponding lipoprotein (100 μg/ml) or in the absence of lipoproteins (control). At indicated time periods (0.5 to 48 hours) the medium was removed and the cells were lysed quickly in 600 μl/dish RLT buffer (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and RNA isolation was performed immediately. Total RNA was isolated by RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) including “on-column” digestion of DNA during the procedure by RNase-Free DNase Set (Qiagen). Purity was checked by RNA-gel electrophoresis and absorbance at 230 to 320 nm. Isolated RNA was reverse transcribed using SuperScriptII (Gibco Life Technologies, Karlsruhe, Germany) using the following reaction composition: 3 mg of total RNA; 1 μl of cDNA-synthesis-primer-mix (Clontech, Heidelberg, Germany); 1 μl of dNTP mix (each nucleotide at 10 mmol/L except dATP); 5 μl of (α-33P)-dATP (10 μCi/μl, Amersham); 13 μl of sterile water according to the SuperScriptII manual including RNaseH digestion. Labeled DNA was purified by spin-column chromatography (MobiSpin S-300; MoBiTec, Göttingen, Germany).

Hybridization to Arrays and Data Analysis

Hybridization to the Atlas Human 1.2 Arrays (7850–1, BD Biological Sciences, Clontech) was performed as described in the manufacturer’s protocol. Hybridized arrays were exposed to Fujifilm imaging plate BAS-MS 2040 and scanned using a Typhoon PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). The RNA for each time point and activation substance was hybridized two times on two different randomly chosen arrays from the same production lot. Image analysis was performed by Array Vision 6.0 (Imaging Research, Ontario, Canada). The absolute expression of each gene was normalized to the mean gene expression on the corresponding array and data were expressed as a factor of this mean expression. For evaluation, only data showing a sufficient signal to noise ratio was used.

Real Time Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction–SYBR Green I

Real time RT-PCR was performed using the LightCycler System (Roche) using the following reagents: primers, 5 pM each, 3 μmol/L MgCl2, 2 μl cDNA and 1 μl LightCycler-FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I (Roche) in a final volume of 10 μl. The LightCycler was programmed to the following temperatures: 1) preincubation and denaturation: 10 minutes at 95°C; 2) amplification: 0 seconds, 95°C, 5 seconds, 60°C, 15 seconds, 72°C; 3) melting curve analysis: continuous increase from 60°C to 95°C. The following primers were used (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany): amino acid transporter E16: sense 5′-GGC GTC ATG TCC TGG ATC-3′, antisense 5′-GAT GAT GGT GAA GCC GAT G-3′; connective tissue growth factor (CTGF): sense 5′-TGA CCT GGC TGT AGC CCC-3′, antisense 5′-CAC AAG CTG TCC AGT CTA ATC G-3′; cytochrome b5 reductase: sense 5′-AGT GCA GTG GTG TGA TCT CG-3′, antisense 5′-ATA TTG CAG ATG TAC GGT GTG G-3′; growth arrest and DNA damage inducible transcript 3 (Gadd 153): sense 5′-GGG AAG TAG AGG CGA CTC G-3′, antisense 5′-CTT CCC CCT GCG TAT GTG-3′; HSP70: sense 5′-CGG AGA AGT ACA AAG CGG AG-3′, antisense 5′-TCT ACC TCC TCA ATG GTG GG-3′; heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1): sense 5′-AAG GAG GAA GGA CCC TAT GG-3′, antisense 5′-TGA GCC AGG AAC AGA GTG G-3′; IL-1β: sense 5′-AGA GTC CTG TGC TGA ATG TGG-3′, antisense 5′-AGA ATG TGG GAG CGA ATG AC-3′; MMP7: sense 5′-GTT TAG AAG CCA AAC TCA AGG-3′, antisense 5′-CTT TGA CAC TAA TCG ATC CAC-3′; thioredoxin reductase: sense 5′-TTG AAG CTG ACA TTT GGC AG-3′, antisense 5′-CAT CAT GTA GCA CAC AGG GG-3′; tubulin α: sense 5′-TCA AGG TTG GCA TCA ACT ACC-3′, antisense 5′-TCC TTC AAC AGA ATC CAC ACC-3′; vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1): sense 5′-ACT TGC TGC CTG AAG AAC AG-3′, antisense 5′-CAA CCC AGT GCT CCC TTT G-3′; Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF): sense 5′-GCC TTG CTG CTC TAC CTC CAC-3′, antisense 5′-ATG ATT CTG CCC TCC TCC TTC T-3′. Using a serial dilution of samples the same amplification efficacy was shown for all primer pairs used. The fluorescence of samples was measured at the end of each elongation cycle. Second derivative method was used to calculate the crossing point for each reaction. α-Tubulin served as internal standard for data normalization; this housekeeping gene showed the lowest variation in the cDNA array experiment. Amplificates were checked by means of melting curve analysis for the right melting temperature and subsequently in 1% agarose TBE gel for the expected length. Reactions were performed in triplicate.

Tissue Samples/Human Biopsies

Human kidney biopsies were obtained from patients after informed consent and with acknowledgment of the respective local ethics committees. A total of 24 renal biopsies available from the ERCB multicenter study (European renal cDNA bank, see footnote for participating centers) were included. For members of the consortium see appendix. All biopsies were stratified according to their histological diagnosis by the reference pathologists of the ERCB. Kidney biopsies from patients with MCD (n = 4) and membranous glomerulopathy (MGN, n = 13) were analyzed. In addition, renal transplant biopsies (n = 7) with histologically confirmed diagnosis of acute tubular damage (ATD) were examined for validation of candidate gene expression. In all samples the extent of mononuclear infiltration in the interstitium was minimal in relation to the extent and severity of tubular epithelial damage. Histological degree of tubulointerstitial damage in renal biopsies was assessed by a semiquantitative grading score and severity was rated as 0 = absent, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe.

Microdissection, RNA Isolation, and RT-PCR (TaqMan) in Renal Biopsies with MCD, MGN, and ATD

Renal biopsies were stored in a commercially available RNase inhibitor (RNAlater, Ambion, Austin, TX). Microdissection was performed manually under a stereomicroscope using two dissection needle holders. This method allowed fast dissection of nephron segments into glomeruli and tubulointerstitial fragments.26

A silica gel-based RNA isolation protocol (RNeasy-Mini; Qiagen) was followed by reverse transcription in a 45-μl volume containing 9 μl of buffer, 2 μl of 0.1 mol/L DTT (both from GIBCO BRL Life Technologies), 0.9 μl of 25 mmol/L dNTP (Amersham Pharmacia, Freiburg, Germany), 1 μl of RNase inhibitor (RNasin; Promega, Mannheim, Germany), 0.5 μl of Microcarrier (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH), 1 μl of random hexamers (2 mg/ml stock; Roche), and 200 U of reverse transcriptase (Superscript I, Invitrogen Life Technologies, Karlsruhe, Germany) for 1 hour at 42°C. RT-PCR was performed on TaqMan ABI 7700 Sequence Detection System (PE Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany) using heat-activated TaqDNA polymerase (Amplitaq Gold; Applied Biosystems), as previously described.26

Commercially available pre-developed TaqMan reagents were used for GAP-DH, 18 S rRNA, MPO, and Cyclophilin A. The primers for all analyzed target genes (HO-1, Trr, VEGF, MMP7, CTGF, IL-1β, Gadd 153, and MPO) were cDNA-specific and did not amplify genomic DNA.

The following oligonucleotide primers (300 nmol/L) and probes (100 nmol/L) were used: human HO-1 (gbNM 002133): sense primer 5′-AGC AAC AAA GTG CAA GAT TCT GC-3′, antisense primer 5′-AAC TGT CGC CAC CAG AAA GCT-3′, fluorescence labeled probe (FAM) 5′-CTC CCA GGC TCC GCT TCT CCG AT-3′; human Trr 1 (gb XM 049211): sense primer 5′-GCT AAG GAG GCA GCC CAA TA-3′, antisense primer 5′-CGA GAC CCC ATC TAG TTC CAA G-3′, FAM 5′-ATG GTC CTG GAC TTT GTC ACT CCC ACC-3′; VEGF (gbNM 003376): sense primer 5′-GCC TTG CTG CTC TAC CTC CAC-3′, antisense primer 5′-ATG ATT CTG CCC TCC TCC TTC T-3′, FAM 5′-AAG TGG TCC CAG GCT GCA CCC AT-3′; human MMP7 (gbNM 002423): sense primer 5′-TGG TAG CAG TCT AGG GAT TAA CTT CCT-3′, antisense primer 5′-CAT AGG TTG GAT ACA TCA CTG CAT TA-3′, FAM 5′-TGC TGC AAC TCA TGA ACT TGG CCA TT-3′; human CTGF (gbNM 001901): sense primer 5′-ACG AGC CCA AGG ACC AAA C-3′, antisense primer 5′-TCT GGG CCA AAC GTG TCT TC-3′, FAM 5′-TCG GTA AGC CGC GAG G −3′; human IL-1β (gbXM 010760): sense primer 5′-GAT GGC CCT AAA CAG ATG AAG TG-3′, antisense primer 5′-TCG GAG ATT CGT AGC TGG ATG-3′, FAM 5′-TCC AGG ACC TGG ACC TCT GCC CTC T-3′; human Gadd 153 (gbNM 004083): sense primer 5′-GGA GAG AGT GTT CAA GAA GGA AGT G-3′, antisense primer 5′-GCA GTT GGA TCA GTC TGG AAA AG-3′, FAM 5′-ACC TGA AAG CAG ATG TG-3′. All primers and probes were obtained from Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany.

Immunohistochemistry

Antibody Reagents

A mouse monoclonal antibody (mAb, clone 2D10G9, subtype IgG2bk, dilution of hybridoma supernatant 1:2) raised against HOCl-LDL was used.25 This mAb is specific for HOCl-modified epitopes and does not cross-react with other oxidative (lipo)protein modifications. In addition, a CTGF mouse mAb (DPC-Biermann, Bad Nauheim, Germany, concentration 25 μg/ml), a rabbit polyclonal anti-human HO-1 antibody (Alexis Biochemicals, Germany, dilution 1:100), a VEGF rabbit polyclonal antibody (Biogene, San Ramon, CA; dilution 1:10) and a MPO rabbit polyclonal antibody (AO398 DAKO, Hamburg, Germany; dilution 1:100) were used.

Immunohistochemistry was carried out on 5-μm formaldehyde fixed, paraffin embedded tissue sections after antigen retrieval by microwave for 10 minutes as described.27

Alkaline Phosphatase Anti-Alkaline Phosphatase (APAAP) Method

Tissue sections were incubated with the respective mouse mAbs for 18 hours at 4°C. A polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse antibody (Z259, DAKO dilution 1:40) was then applied at 22°C for 1 hour, alkaline-phosphatase mouse mAbs (dilution 1:40) and incubated at 22°C for 1 hour. All dilutions were performed in PBS, pH7.6. For staining, the sections were exposed to a solution of sodium nitrite (28 mmol/L), new fuchsin (basic-fuchsin) (21 mmol/L), naphthol-AS-B1-phosphate (0.5 mol/L), dimethylformamide (64 mmol/L) and levanisol (5 mmol/L) in 50 mmol/L Tris/HCl buffer, pH 8.4 containing 164 mmol/L NaCl for 15 minutes. When rabbit anti-human antisera were used as primary antibodies, the initial reaction was followed by a mouse anti-rabbit antibody (M737 DAKO, dilution 1:50) followed by rabbit anti-mouse antibody Z259 and reactions were performed as described above.

Avidin Biotinylated Enzyme Complex (ABC) Method

For mouse mAbs, following blockade of endogenous peroxidase activity by incubating the section in 3% H2O2 at 22°C for 10 minutes, nonspecific binding sites were saturated with 4% skim milk in PBS, pH 7.6 at 22°C for 20 minutes. The primary antibody was added to the sections for 18 hours at 4°C. Then applying avidin followed by biotin (avidin/biotin blocking kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) endogenous biotin, or unspecific avidin binding were blocked. This was followed by an anti-mouse biotinylated secondary antibody (PharMingen 02002D, dilution 1:250 in 1% BSA/PBS at 22°C for 1 hour). A streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase complex (Vector Laboratories SA 5004, dilution 1:200) was then incubated at 22°C for 1 hour. 3-Amino-9-ethylcarbazole or 3,3′-diaminobenzidine substrate kit (SK-4200 or SK-4100, respectively, Vector Laboratories) were used for specific staining.

Counterstaining was performed with hematoxylin at 22°C for 4 minutes. Control experiments for the immunohistochemical assays encompassed immunohistology with non-immune mouse, or rabbit IgG, respectively, and reactions without primary antibody.

Semiquantitative evaluation of expression of MPO and HOCl-modified (lipo)proteins in the renal biopsies was done in MCD (n = 4) and MGN (n = 12). MPO positive cells were counted per high power field (HPF, ×40 objective) of tubulointerstitium. The extent for HOCl staining in the tubulointerstitium was also evaluated per HPF and graded as 0 = null, 1 = slight, 2 = moderate, and 3 = pronounced in tubular epithelia and interstitium. A mean score was calculated.

Statistical Analysis

Mean values are given ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student′s t-test. Significance is indicated with each result.

Results

HOCl-LDL Has Antiproliferative and Mild Proapoptotic Effects on HK-2 Cells

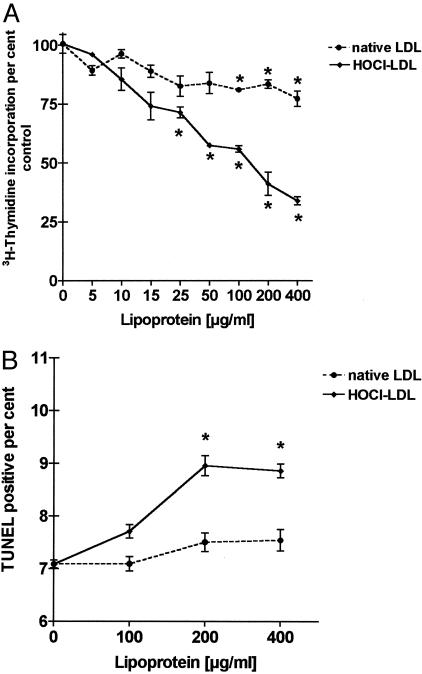

To reveal specific effects of exogenous lipoproteins on proximal tubular epithelia, we examined the proliferative and apoptotic response of HK-2 cells to increasing concentrations of LDL and HOCl-LDL. Lipoproteins were used as stimuli at concentrations ranging between 5 and 400 μg of protein/ml. After 24 hours the incorporation of [3H]thymidine was measured as an indicator of proliferative activity. Unstimulated cells grown in media were used for controls. Cell proliferation was expressed as a percentage of the proliferative rate in treated compared to non-treated HK-2 cells. [3H]thymidine incorporation into HK-2 cells showed a steady and significant decrease in the presence of HOCl-LDL at concentrations up to 400 μg of protein/ml after 24 hours. In contrast to HOCl-LDL, the effects of LDL were less pronounced at the same concentrations investigated (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Effects of LDL and HOCl-LDL on proximal tubular cell proliferation and apoptosis. A: [3H]thymidine incorporation after 24 hours as a measure of proliferative activity in response to increasing concentrations (5 to 400 μg protein/ml) of LDL or HOCl-LDL. For each lipoprotein concentrationthe proliferative activity is expressed as a percentage (±SEM, n = 3) of theincorporation measured in HK-2 cells grown in media (the zero-point ofthe x axis). The proliferative rates were tested by means of the Students’ t-test for a significant difference (*P < 0.01) from the proliferative rate measured in the untreated cells. B: TUNEL-positive percent (±SEM, n = 3) of counted cells as a measure of apoptotic rate in response to indicated concentrations of LDL and HOCl-LDL. Apoptosis rates were tested for significant difference (*P < 0.01) in comparison to untreated HK-2 cells.

Subconfluent control cultures of HK-2 cells were 7.1 ± 0.07% (mean ± SEM, n = 3) TUNEL-positive after 24 hours (Figure 1B). LDL when present at concentrations up to 400 μg protein/ml did not alter the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells (an indicator of apoptosis) in HK-2 cells. At HOCl-LDL concentrations of 200 and 400 μg protein/ml the rate of apoptosis increased significantly (P < 0.01) up to 8.9 ± 0.13% (mean ± SEM, n = 3). Based on these results, a lipoprotein concentration of 100 μg of LDL and HOCl-LDL protein/ml was chosen for the time-course experiments of gene expression.

cDNA Array and RT-PCR Expression Data Show Analogous Tendencies

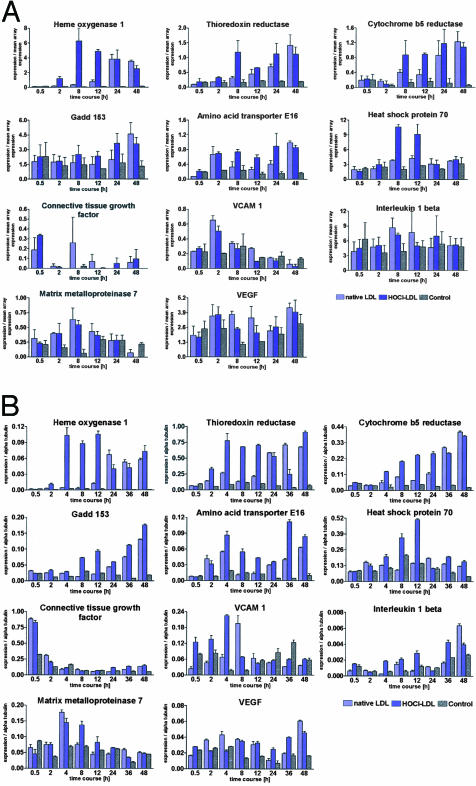

Next, HK-2 cells were exposed to LDL or HOCl-LDL (100 μg/ml) up to 48 hours and total RNA was isolated at indicated time points (0.5, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 48 hours). mRNA was then reverse transcribed and used to generate radioactive probes for analysis on Atlas (BD Biological Sciences, Clontech) 1.2 cDNA arrays. These arrays contain 1176 sequences of genes involved in cell cycle, signal transduction and stress response. Gene expression profiles revealed a group of 11 genes showing at least a twofold increase at various time points in comparison to untreated cells. Figure 2A shows the time course of expression of the 11 genes in response to LDL and HOCl-LDL measured by the cDNA macroarrays.

Figure 2.

LDL and HOCl-LDL stimulation of human proximal tubular cells (HK-2) causes a differential up-regulation of specific sets of genes. A: Expression profiles obtained from cDNA-arrays of the 11 genes identified using the Atlas 1.2 macroarray. Selected time points are shown here, and for each time point three bars (±SEM, n = 3) are depicted representing the expression under the influence of either LDL or HOCl-LDL or growth media as a control. cDNA array data were normalized to the mean gene expression on the corresponding filter. The expression data were subsequently confirmed by quantitative real-time PCR. B: Quantitative RT-PCR-based expression profiles normalized to the internal standard α tubulin. For each time point three bars (±SEM, n = 3) are shown, representing the expression in the presence (LDL or HOCl-LDL) or absence of lipoproteins.

In principle, two groups of genes were identified. One group of genes was described to be involved in cellular stress and reactive oxygen species metabolism (HO-1, Trr, cytochrome b5 reductase, Gadd 153, amino acid transporter E16, and HSP70). The other group represents genes involved in inflammation and tissue remodeling (CTGF, VCAM-1, IL-1β, MMP7, and VEGF).

Of the 29 genes associated with cell cycle regulation (see at http://www.bdbiosciences.com/clontech/atlas) none showed statistically significant changes in expression in response to LDL or HOCl-LDL stimulation. This does not preclude that the genes would show significant altered regulation in vivo.

Quantitative RT-PCR (SYBR Green) was used to verify expression of the cDNA array data. The overall pattern remained similar although some quantitative differences were seen between the DNA array analysis and the real-time RT-PCR measurements. The gene expression profiles for the group of 11 genes are shown in Figure 2B. For each of the eight time points (0.5, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 48 hours) three bars are displayed indicating mRNA expression in response to the absence (medium without lipoproteins) or presence of lipoproteins.

HOCl-LDL Causes Rapid Up-Regulation of Genes Central to Reactive Oxygen Species Metabolism and Cellular Stress

In cells treated with HOCl-LDL a significant up-regulation in the first group of genes (HO-1, Trr, cytochrome b5 reductase, Gadd 153, and amino acid transporter E16) was seen by 2 to 8 hours; expression levels remained elevated through the 48-hour time period. In contrast to HOCl-LDL, LDL caused only a moderate change in gene expression levels after 2 to 8 hours, with the exception of the amino acid transporter E16. However, mRNA expression in the presence of exogenous LDL increased after 24 hours to levels comparable to the HOCl-LDL-induced levels by the 36- and 48-hour time points. HSP70 showed pronounced transient up-regulation after 12 hours in response to HOCl-LDL only (Figure 2B).

LDL and HOCl-LDL Up-Regulate Inflammatory and Tissue Remodeling Genes

In a parallel set of experiments, gene expression in a second group of genes was investigated. Exposure of cells to LDL and HOCl-LDL led to an early-transient increase in mRNA expression of CTGF at 0.5 hours (Figure 2B). After 4 and 8 hours, mRNA for VCAM-1 was increased when exposed either to LDL or HOCl-LDL. IL-1β showed increased expression after 4 hours with maximal levels reached by 36 and 48 hours. MMP7 was up-regulated transiently between 2 to 8 hours, while expression levels of VEGF tended to consistently increase in response to both lipoprotein preparations at later time points.

Gene Expression Was Verified in Biopsy Samples Taken from Patients Showing Tubular Interstitial Damage

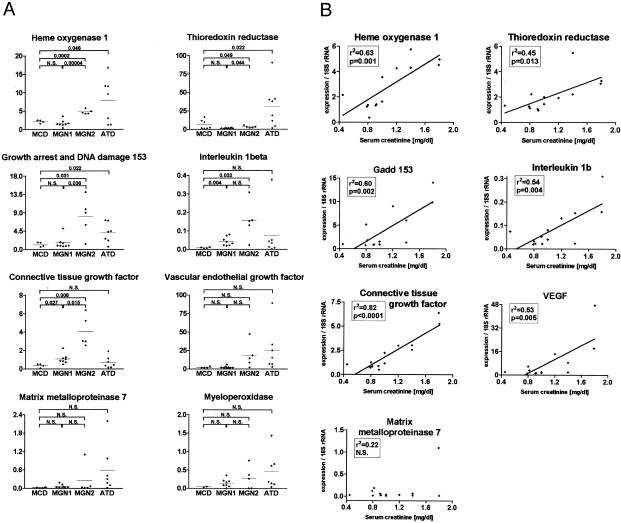

To verify the in vivo validity of the genes identified in the in vitro expression model, a panel of renal biopsy samples taken from patients with MCD, ATD, as well as MGN was analyzed for gene expression. Tubulointerstitial areas were isolated by microdissection,26 RNA was isolated and TaqMan RT-PCR was used to quantify mRNA species. Expression levels were referenced to the level of 18 S rRNA.28 In addition, MPO mRNA levels were determined. Patients with MCD have proteinuria but a low incidence for the presence of HOCl-modified epitopes. MGN patients have proteinuria but may have different levels of HOCl-modified proteins. Clinically, MGN patients can be subdivided into patients with intact renal function (serum creatinine levels lower than 1.2 mg/dl, termed MGN-1) and those showing declining renal function (serum creatinine levels higher than 1.2 mg/dl, termed MGN-2). The gene expression in the MCD biopsies was taken as “LDL controls.” The gene expression patterns were then contrasted between MCD, ATD and MGN. Gene expression in the ATD and MGN-2 biopsies, where abundant proteinuria and HOCl-modified proteins emerge (Figure 3), contrasted with expression in the MCD and MGN-1 biopsies. As indicated in Figure 3A the expression of HO-1, Trr, and Gadd 153 was significantly higher in ATD biopsies than in MCD biopsies. MGN 1 biopsies showed similar expression patterns as those seen in the MCD biopsies with the exception of IL-1β and CTGF, for which the MGN 1 samples were higher. In addition, for the latter two genes that are known to be involved in inflammation and fibrosis, there were no significant differences seen between MCD and ATD. In contrast, the expression between MGN 2 and MCD differed significantly for most genes examined. MMP7, VEGF, and MPO tended to be more strongly expressed in ATD. Finally, with the exception of MMP7, significant positive correlations between the gene expression rates and blood creatinine levels were observed in the MGN samples (Figure 3B). No significant correlation could be demonstrated between gene expression in the MGN samples and proteinuria nor the semiquantitative histological degree of tubulointerstitial damage (correlations not shown).

Figure 3.

A: mRNA expression levels of selected genes predominantly involved in metabolism of reactive oxygen species and cell stress (HO-1, Trr and Gadd 153) or in tissue remodeling and inflammation (VEGF, CTGF, IL-1β, MMP7) as well as MPO were measured by TaqMan RT-PCR in microdissected tubulointerstitial compartments of kidney biopsies with ATD (n = 7), MCD (n = 4) or MGN (n = 13). Based on serum creatinine levels, the MGN patient group was divided into MGN-1 (n = 8, serum creatinine levels lower than 1.2 mg/dl) and MGN-2 (n = 5, serum creatinine levels higher than 1.2 mg/dl). Expression values were normalized to 18 S rRNA. Gene expression in the MCD group was tested for significant difference relative to expression in ATN, MGN-1, and MGN-2 samples as well as differences between MGN-1 and MGN-2, respectively. Significance was calculated by means of the Student′s t-test, P values displayed if significant, ie <0.05. B: Expression of mRNA levels of selected genes involved in metabolism of reactive oxygen species and cell stress (HO-1, Trr, and Gadd 153) or in tissue remodeling and inflammation (IL-1β, CTGF, VEGF, MMP7) were measured by TaqMan RT-PCR in microdissected tubulointerstitial compartments of MGN kidney biopsies. Expression was normalized to 18 S rRNA. For each gene the graph shows correlation between its expression and serum creatinine concentration.

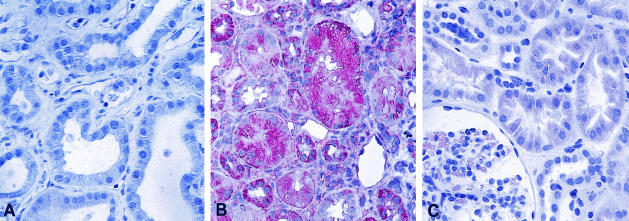

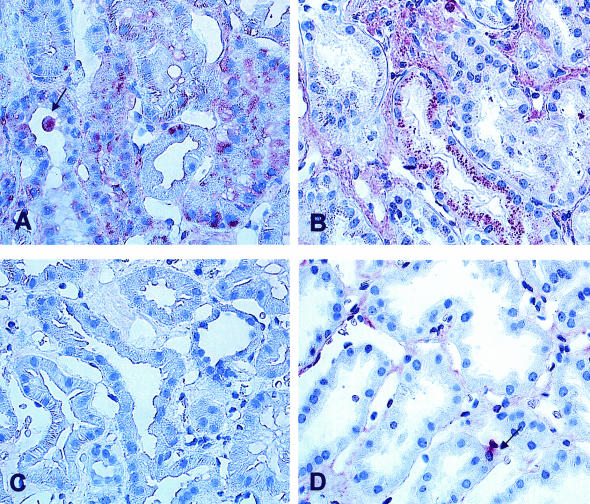

HOCl-Modified Proteins Are Present in Tubular Damage but Not in MCD

To confirm the presence of HOCl-modified (lipo)proteins in renal biopsy samples a specific mAb was used.25 In line with our previous findings13,15 no staining for HOCl-modified (lipo)proteins was found in normal control kidney biopsies (Figure 4A) and only focal very faint staining was observed in MCD (Figure 4C). However, pronounced staining for HOCl-modified (lipo)proteins could be seen in ATD; staining for HOCl-modified epitopes was associated primarily with tubular epithelia and interstitial mononuclear cells (Figure 4B eg, transplant showing ATD).

Figure 4.

Presence of HOCl-modified (lipo)proteins in kidney tissues. As confirmed by immunohistology both a control human kidney (A) and a kidney with MCG (C) lack staining for HOCl-modified (lipo)proteins. In contrast (B) in renal transplant showing acute tubular damage (ATD) staining for HOCl-modified (lipo)proteins can be seen in tubular epithelia and in interstitial mononuclear cells. A: avidin-biotinylated enzyme method. B and C: APAAP method (as described in Materials and Methods); magnification ×400.

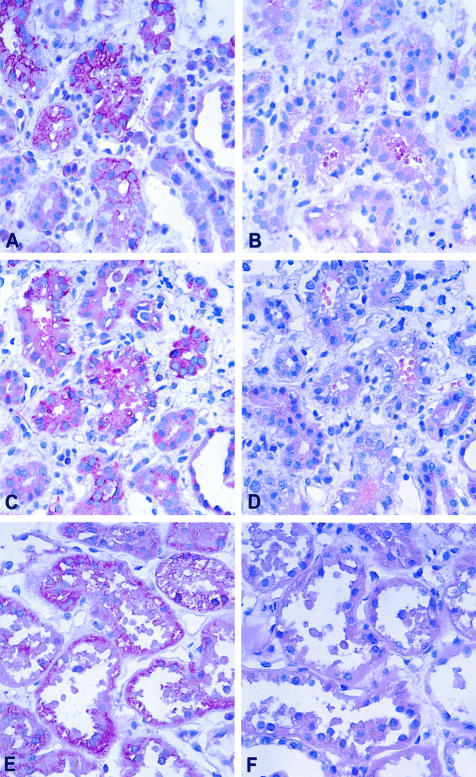

In MGN staining for MPO and HOCl-modified (lipo)proteins was found in glomerular basement membranes as described in our previous work13 and in those areas of the tubulointerstitium which were damaged (Figure 5, A and B). In biopsies from MGN-2 patients showing declining renal function intensive staining for HOCl-modified (lipo)proteins was found in protein droplets of proximal tubules. Figure 5A shows a large cytoplasmic bleb which is positive for the presence of HOCl-modified (lipo)proteins. In the same biopsy sample MPO was detected in protein droplets of proximal tubules and in interstitial mononuclear cells (Figure 5B). In biopsy samples from MGN-1 patients with intact renal function, weak to moderate staining for HOCl-modified (lipo)proteins could be detected in tubules by immunohistology (Figure 5C). In the same biopsy sample MPO was associated with monocytes within the interstitium, while no significant staining for MPO was found in the tubules. Accordingly, a semiquantitative assessment of tubulointerstitial immunohistological expression of HOCl- modified (lipo)proteins revealed a HOCl-score of 0.81 ± 0.22 in MGN-1 vs. 1.89 ± 0.59 in MGN-2. In both MGN groups (MGN-1 and MGN-2) the number of MPO-positive cells in the tubulointerstitium was not significantly different due to varying densities of focally arranged MPO positive cells (MGN-1 vs. MGN-2, 1.73 ± 0.4 vs. 3.5 ± 1.43 cells HPF). These data correspond to MPO mRNA levels which showed a trend of increased expression from MGN-1 to MGN-2 to ATD (Figure 4A) but did not correlate with serum creatinine levels (Figure 3B).

Figure 5.

Presence of HOCl-modified (lipo)proteins and MPO in kidney samples from patients with MGN. A: HOCl-modified epitopes are present in MGN with decreased renal function. Protein droplets of proximal tubules are strongly reactive. A large cytoplasmic bleb protruding into the tubular lumen (arrow) is stained. B: In the same biopsy as shown in A, staining for MPO can be seen in protein droplets of proximal tubules and in some interstitial mononuclear cells. C: In MGN with normal excretory function no staining for HOCl epitopes can be detected in tubules by immunohistology. D: Staining for MPO in MGN with regular function can be seen in isolated monocytes in the interstitium; there is some unspecific stain along peritubular capillaries, but tubules do not show positivity for MPO to a significant extent. A and C: Avidin-biotinylated enzyme method, B and D: APAAP method.

Expression of VEGF, CTGF, and HO-1 Was Verified Using Immunohistochemistry

To verify protein expression in the tubuli antibodies specific for HO-1, CTGF and VEGF were tested. For these studies renal biopsy specimens with acute tubulointerstitial lesions were used. In all cases VEGF, CTGF, and HO-1 were detected in damaged proximal tubular epithelia (Figure 6, A, C, and E); in contrast normal regions taken from tumor nephrectomies, used as suitable controls, did not show any staining for expression of tubular proteins, eg, VEGF, CTGF, and HO-1 (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Expression of HO-1, CTGF, and VEGF protein in acutely damaged tubular epithelia using immunohistology. A: HO-1 was found expressed in tubular epithelia with acute damage. The staining shows tubuli with irregular cytoplasmic vacuolization; B: negative control using an isotype control antibody showing no label. C and D: CTGF can be localized to the same tubules as shown in A; D: no staining for CTGF became apparent after omission of the primary antibody. E: VEGF is present in tubules with flattened epithelia which have discarded cytoplasmic blebs into the tubular lumen; F: negative control using isotype shows no stain. A–F: APAAP method.

Discussion

It has been suggested that atherosclerosis and glomerulosclerosis are pathophysiologically analogous processes.29 Hyperlipidemia and atherogenic lipoproteins can be initiating factors for both diseases30 and abnormalities in lipids and lipoproteins are present in both disease states. Lipid abnormalities have been shown to influence the progression of renal disease.31 Both, MPO and HOCl-modified (lipo)proteins are present in atherosclerotic lesions.9,32 Furthermore, the MPO-H2O2-chloride system plays a major role in kidney disease.33 MPO is present in tubulointerstitial lesions and HOCl-modified epitopes are also present in the tubulointerstitium of patients with ATD, immune complex glomerulonephritis and vascular degenerative renal diseases (Figure 4).13,15 Thus, we assumed that HOCl-LDL, compared to native LDL, may adversely affect proximal tubular cells. Therefore, the present study was designed to analyze in vitro effects of HOCl-LDL on proximal tubular cells in culture and to identify genes potentially involved in tubulointerstitial damage, and finally, to characterize their expression in renal biopsy samples.

HOCl-LDL has dose-dependent antiproliferative effects on proximal tubular cells. HOCl-LDL elicits an early gene expression pattern typical for defense to cellular stress and diminished cell proliferation. Gene expression analysis showed that after 2 to 4 hours HOCl-LDL increased the expression of genes involved in the metabolism of reactive oxygen species and cell stress eg, HO-1, Trr, cytochrome b5 reductase, Gadd 153, and HSP70. At later time points (24 to 48 hours) LDL produced a similar up-regulation. This late up-regulation of “redox” and cell stress genes with both LDL and HOCl-LDL and the almost simultaneous up-regulation of inflammatory and fibrogenic genes (eg, CTGF, IL-1β) may reflect a common but temporarily different effect of both lipoprotein species on intracellular cholesterol metabolism. LDL modified with physiologically relevant HOCl concentrations (oxidant to lipoprotein molar ratio of 400:1 as used in the present study) is a high affinity ligand for scavenger receptor class B, type I,17 the prime receptor mediating selective cholesteryl ester uptake from lipoprotein particles. In contrast, native LDL is preferentially bound by the classical LDL receptor and subsequent holoparticle internalization leads to uptake of cholesterol and cholesteryl esters; both receptors are present on HK-2 cells.34 The fact that high affinity interaction of HOCl-LDL with its receptor may lead to alteration of intracellular signaling35 could explain the early and long-lasting gene expression patterns induced by HOCl-LDL. Thus both, LDL and HOCl-LDL seem to induce common signal transduction pathways with a consecutive gene expression pattern which occurs faster and more stable with HOCl-LDL in proximal tubular cells in culture. In human renal tissue only the latter effects seem to be dominant in vivo as only biopsies with relevant HOCl modifications demonstrate a gene expression set comparable to that found in cell culture. MCD accompanied with pronounced unselective proteinuria and tubular lipoprotein leakage but without oxidative LDL modification did not express stress, inflammatory, or fibrogenic gene patterns.

It is known that oxidative modification of LDL may occur during cell culture experiments performed during long-time incubation periods.36,37 However, the culture medium used during the present study did not contain iron or copper. Therefore, late gene expression in HK-2 cells observed with native LDL probably cannot be attributed to the effect of transition metals known to promote LDL oxidation.

To verify and characterize the increased expression of a subset of these genes (HO-1, Trr, VEGF, MMP7, CTGF, IL-1β, and Gadd 153, as well as MPO) ex vivo, examples of tubulointerstitial regions were microdissected from biopsy samples derived from different groups of patients suffering from proteinuria and diagnosed as MGN, as well as MCD and ATD. Only in ATD and MGN HOCl-modified (lipo)proteins are present in the tubules, whereas no or neglectible staining for HOCl-modified (lipo)proteins was seen in MCD.13,15 HO-1, Trr and Gadd 153 showed a statistically increased expression in the tubulointerstitium of biopsies with acute tubular injury as opposed to MCD biopsies. While mRNA expression of MMP7, VEGF and CTGF showed a trend toward increased expression in ATD, it could not be scored as statistically significant. In MGN biopsies the expression of HO-1, Trr, Gadd 153, and CTGF was increased in patients showing decline of renal function, and mRNA expression levels of HO-1, Trr, VEGF, Gadd 153, IL-1β, and CTGF correlated significantly with the level of serum creatinine. In these patients also a higher intensity of HOCl-modified (lipo)proteins in the tubulointerstitial compartment was found associated with an increased tendency of cells positive for MPO. This finding is congruent with our hypothesis that modifications of plasma (lipo)proteins by HOCl, occurring under in vivo conditions, may rapidly and over a long time activate tubular epithelia.

However, no correlation between the levels of gene expression and the extent of proteinuria was observed. As special care was taken to only select biopsies in which tubular damage was dominant in comparison to interstitial mononuclear infiltration, the tubular compartment was the major contributor to the mRNA profiles obtained. Also, the immunological results show the tubular epithelial cells to be the main cell population for respective gene/protein expression (Figure 6). The data support the premise, as is specifically demonstrated in the MCD biopsies, that proteinuria per se is not an obligate activator of these gene expression patterns observed in tubular epithelia but that tubular damage and oxidative stress with immunological evidence of oxidatively modified (lipo)proteins seem to be major modulators of the gene expression programs in tubular epithelia in vivo. This is mirrored in the early phase of exposure of human tubular epithelia to LDL or HOCl-LDL.

Cell Stress and Reactive Oxygen Species Metabolism

Protective effects of HO-1 in various cell types and experimental conditions have been described.38–40 HO-1 is responsible for degradation of heme.41 During this reaction biliverdin IX, CO, and Fe3+ are liberated. Bilirubin, an end product of this process, may be considered a potent antioxidant. CO possesses vasodilatative, antiaggregative, and immunosuppressive properties.39 HO-1 has been proposed as an intracellular marker of oxidative stress elicited by modified LDL as its induction has been shown to be dependent on the degree of LDL modified with copper ions.42,43 Expression of HO-1 was significantly higher in patients with ATD and MGN 2 compared with patients with MCD or MGN 1, stressing the in vivo role of oxidatively modified proteins in eliciting oxidative stress in tubular cells.

Trr catalyzes NADPH-dependent reduction of thioredoxin disulfide and other oxidized cell constituents.44 Thioredoxin in its reduced state ensures the reducing properties of the intracellular milieu and promotes the DNA binding capacity of several crucial transcription factors (eg, NF-κB, Ref-1, and AP1) involved in antiapoptotic, pro-inflammatory but also anti-inflammatory processes.45 Thioredoxin secretion is seen during inflammation and oxidative stress and has been shown to promote cytokine release from fibroblasts and monocytes.46,47 The potential involvement of the thioredoxin/Trr-system in the balance between antioxidation and tubulointerstitial inflammation and fibrosis is intriguing. This novel observation of Trr induction in response to HOCl-LDL and its increased expression at the mRNA level in patients with ATD and MGN suggests a role for the thioredoxin system in tubulointerstitial damage.

Cytochrome b5 reductase catalyzes FAD mediated electron transport from NADH to cytochrome b5, a membrane bound hemoprotein. Cytochrome b5 reductase plays a protective role during oxidative stress.48 These results also suggest that oxidatively modified proteins may be able to directly up-regulate genes involved in the response to oxidative stress.

Gadd 153 was increased in mRNA expression in biopsies with ATD and in biopsies from patients with MGN and decreased renal function. Gadd 153 is a stress-induced gene that interferes with the DNA binding activity of transcription factors C/EBP (CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein) by forming heterodimers, and thus functions as a dominant negative inhibitor of gene transcription with antiproliferative effects. The antiproliferative effects of Gadd 153 are consistent with our finding of a decrease in thymidine incorporation after addition of exogenous HOCl-LDL to HK-2 cells. HOCl-LDL-mediated up-regulation of Gadd 153 was seen after 8 hours and the dose-dependent, antiproliferative effect of HOCl-LDL was measured after 24 hours (Figure 1). Up-regulation of Gadd 153 and HSP70 has been demonstrated in a proximal tubular cell line in a model of reactive oxygen stress49,50 supporting our observations that exposure of proximal tubular epithelia to exogenous HOCl-LDL induced an oxidative stress in these cells.

Tissue Remodeling and Inflammation

CTGF belongs to the CCN family of immediate early response genes and was originally isolated as a product of endothelial cells; it influences the proliferation and migration of fibroblasts. CTGF has been implicated as a downstream mediator of transforming growth factor-β.51

The sequences for transforming growth factor-β -α, 1, 2, and 3 were included on the cDNA array used in this screen and were not found up-regulated in response to stimulation suggesting that lipoproteins up-regulate CTGF independently of transforming growth factor-β. A significantly higher expression of CTGF was observed in patients with membranous glomerulonephritis than in the minimal change disease samples and showed the strongest correlation to decrease in renal function (Figure 3B).

VEGF enhances endothelial cell proliferation, blood vessel dilatation and vascular permeability and possesses chemotactic activity for monocytes.52 VEGF has been described in acutely hypoxic tubuli in acute vascular rejection of renal allografts suggesting that acute stress to proximal tubular cells such as hypoxia or proteinuria is sufficient to induce VEGF expression.53 While these results could be confirmed in the cell culture model, the results from microdissection of damaged human proximal tubuli did not reach statistical significance (Figure 3A).

In summary, we have shown that LDL and HOCl-LDL exert temporarily different effects on proximal tubular epithelia in culture. HOCl-LDL significantly affects proliferation and causes an early but strong increase in expression of proteins typical for reactive oxygen stress defense and DNA damage. The impact of HOCl-LDL on proximal tubular cells is more detrimental than LDL and may lead to an exhaustion of the proliferative capacity of HK-2 cells. In addition these stress genes and genes linked to interstitial inflammation and matrix remodeling are also significantly up-regulated in human renal diseases with an increased staining of HOCl-modified epitopes and chronic tubulointerstitial damage; the genes cannot be found in patients with renal diseases with proteinuria but without oxidatively modified proteins and normal renal function. The data presented here support the potential pathophysiological role of HOCl-modified proteins in vivo by demonstrating the exclusive up-regulation of a subgroup of genes if proteinuria is accompanied by HOCl-LDL. These gene products may thus contribute to progression of chronic tubulointerstitial damage and fibrosis.

Table 1.

Clinical and Histological Findings and Gene Expression of HO-1, Trr, VEGF, MMP7, CTGF, IL-1β, Gadd 153, and MPO (as Ratio Target/18 S rRNA) in Nephrotic and Non-Nephrotic Kidney Biopsies

| Histological diagnosis | Patient sex/age | Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | Tubular damage score | HO-1/18S rRNA | Trr/18S rRNA | VEGF/18S rRNA | MMP7/18S rRNA | CTGF/18S rRNA | IL 1β/18S rRNA | Gadd 153/18S rRNA | MPO/18S rRNA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATD | F/66 | 6.46 | 1 | 11.67 | 18.79 | 6.84 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 4.34 | 0.176 |

| ATD | M/41 | 4.64 | 1 | 3.01 | 4.12 | 2.65 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.65 | 0.039 |

| ATD-AN | M/36 | 7.90 | 2 | 1.29 | 11.26 | 6.58 | 0.97 | 0.75 | 0.00 | 2.61 | 0.114 |

| ATD-AN | M/53 | 6.90 | 2 | 1.22 | 37.82 | 15.18 | 0.18 | 0.43 | 0.38 | 2.20 | 1.433 |

| ATD-AN | F/61 | 6.70 | 2 | 11.78 | 40.96 | 25.17 | 2.19 | 1.90 | 0.04 | 7.13 | 0.136 |

| ATD-AN | M/64 | 7.10 | 3 | 9.61 | 39.80 | 32.96 | 0.30 | 0.36 | 0.05 | 4.49 | 0.610 |

| ATD-AN | F/62 | 4.90 | 3 | 16.71 | 90.29 | 89.19 | 0.41 | 1.14 | 0.03 | 7.02 | 0.662 |

| MCD | M/32 | 1.3 | 0 | 2.32 | 2.94 | 3.46 | 0.21 | 1.06 | 0.01 | 0.97 | 0.027 |

| MCD | F/32 | 0.7 | 0 | 1.04 | 2.39 | 3.09 | 0.17 | 0.50 | 0.01 | 8.15 | 0.047 |

| MCD | M/20 | 0.88 | 0 | 2.11 | 2.95 | 8.22 | 0.07 | 1.73 | 0.02 | 5.30 | NE |

| MCD | F/20 | 0.5 | 0 | 4.36 | 6.78 | 5.07 | 0.63 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 5.63 | NE |

| MGN | F/20 | 0.45 | NE | 2.14 | 1.33 | 2.06 | 0.03 | 1.05 | 0.07 | 1.00 | 0.165 |

| MGN | F/41 | 0.79 | 1 | 1.23 | 1.26 | 1.15 | 0.12 | 0.71 | 0.02 | 0.78 | 0.086 |

| MGN | M/77 | 0.8 | 2 | 1.35 | 1.13 | 5.86 | 0.01 | 1.26 | 0.03 | 5.14 | 0.052 |

| MGN | M/60 | 0.82 | 2 | 0.37 | 2.21 | 3.18 | 0.19 | 0.83 | 0.02 | 1.80 | 0.349 |

| MGN | M/42 | 0.91 | 3 | 1.32 | 1.06 | 1.32 | 0.06 | 0.87 | 0.05 | 0.86 | 0.208 |

| MGN | M/55 | 0.92 | 3 | 1.42 | 0.94 | 1.48 | 0.02 | 0.49 | 0.02 | 0.93 | 0.085 |

| MGN | F/64 | 1 | 1 | 3.55 | 2.00 | 1.98 | 0.04 | 2.24 | 0.08 | 1.55 | 0.000 |

| MGN | M/36 | 1 | 2 | 1.63 | 1.44 | 1.60 | 0.01 | 1.15 | 0.04 | 0.95 | 0.191 |

| MGN | M/65 | 1.2 | 2 | 4.26 | 1.93 | 14.41 | 0.03 | 2.98 | 0.13 | 9.02 | 0.753 |

| MGN | M/41 | 1.4 | 1 | 5.75 | 5.47 | 1.99 | 0.07 | 2.57 | 0.15 | 1.35 | 0.000 |

| MGN | M/58 | 1.4 | 2 | 4.30 | 2.21 | 8.56 | 0.02 | 3.03 | 0.02 | 6.02 | 0.000 |

| MGN | M/72 | 1.79 | 3 | 4.52 | 3.07 | 18.22 | 1.10 | 6.38 | 0.16 | 9.86 | 0.366 |

| MGN | M/61 | 1.8 | 1 | 4.95 | 3.29 | 47.38 | 0.02 | 5.23 | 0.31 | 14.05 | 0.260 |

AN, anuric; NE, not estimated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Karin Frach, Sandra Irgang, and Claudia Schmidt for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Hermann-Josef Gröne, M.D., Department of Cellular and Molecular Pathology, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Im Neuenheimer Feld 280, Heidelberg, Germany. E-mail: h.-j.groene@dkfz-heidelberg.de; or Peter J. Nelson, Med. Poliklinik, Ludwig Maximhaus- University of Munich, Germany. E-mail: peter.nelson@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Supported in part by the German Human Genome Project (DHGP) to M.K., SFB 571 and GRK 455 to P.J.N., and DFG grant FG: Pathogenetic Mechanisms of Progression of Renal Disease: Project D to H.J.G., and the Austrian Science Fund (P 15404 and 17013) to E.M.

Members of the European Renal cDNA Bank (ERCB): C. Cohen,H. Schmid, M. Kretzler, D. Schlöndorff, Munich; F. Delarue, J. D. Sraer, Paris; M. P. Rastaldi, G. D’Amico, Milano; F. Mompaso, Madrid; P. Doran, H. R. Brady, Dublin; D. Mönks, C. Wanner, Würzburg; A. J. Rees, Aberdeen; P. Brown, Aberdeen; F. Strutz, G. Müller, Göttingen; P. Mertens, J. Floege, Aachen; N. Braun, T. Risler, Tübingen; L. Gesualdo, F. P. Schena, Bari; J. Gerth, G. Stein, Jena; R. Oberbauer, D. Kerjaschki, Vienna; M. Fischereder, B. Krämer, Regensburg; W. Samtleben, W. Land, Munich; H. Peters, H. H. Neumayer, Berlin; K Ivens, B. Grabensee, Düsseldorf.

References

- Tang S, Leung JC, Abe K, Chan KW, Chan LY, Chan TM, Lai KN. Albumin stimulates interleukin-8 expression in proximal tubular epithelial cells in vitro and in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:515–527. doi: 10.1172/JCI16079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benigni A, Zoja C, Remuzzi G. The renal toxicity of sustained glomerular protein traffic. Lab Invest. 1995;73:461–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorhead JF. Lipids and progressive kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 1991;31:S35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwinner W, Grone HJ. Role of reactive oxygen species in glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15:1127–1132. doi: 10.1093/ndt/15.8.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RJ, Couser WG, Chi EY, Adler S, Klebanoff SJ. New mechanism for glomerular injury: myeloperoxidase-hydrogen peroxide-halide system. J Clin Invest. 1987;79:1379–1387. doi: 10.1172/JCI112965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce NW, Tipping PG, Holdsworth SR. Glomerular macrophages produce reactive oxygen species in experimental glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 1989;35:778–782. doi: 10.1038/ki.1989.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettle AJ, Gedye CA, Winterbourn CC. Mechanism of inactivation of myeloperoxidase by 4-aminobenzoic acid hydrazide. Biochem J. 1997;321 (Pt 2):503–508. doi: 10.1042/bj3210503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampton MB, Kettle AJ, Winterbourn CC. Inside the neutrophil phagosome: oxidants, myeloperoxidase, and bacterial killing. Blood. 1998;92:3007–3017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazell LJ, Stocker R. Oxidation of low-density lipoprotein with hypochlorite causes transformation of the lipoprotein into a high-uptake form for macrophages. Biochem J. 1993;290:165–172. doi: 10.1042/bj2900165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prutz WA. Hypochlorous acid interactions with thiols, nucleotides DNA, and other biological substrates. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;332:110–120. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterbourn CC, Garcia RC, Segal AW. Production of the superoxide adduct of myeloperoxidase (compound III) by stimulated human neutrophils and its reactivity with hydrogen peroxide and chloride. Biochem J. 1985;228:583–592. doi: 10.1042/bj2280583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vissers MC, Winterbourn CC. The effect of oxidants on neutrophil-mediated degradation of glomerular basement membrane collagen. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;889:277–286. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(86)90190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grone HJ, Grone EF, Malle E. Immunohistochemical detection of hypochlorite-modified proteins in glomeruli of human membranous glomerulonephritis. Lab Invest. 2002;82:5–14. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vissers MC, Day WA, Winterbourn CC. Neutrophils adherent to a nonphagocytosable surface (glomerular basement membrane) produce oxidants only at the site of attachment. Blood. 1985;66:161–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malle E, Woenckhaus C, Waeg G, Esterbauer H, Grone EF, Grone HJ. Immunological evidence for hypochlorite-modified proteins in human kidney. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:603–615. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamanna VS, Pai R, Roh DD, Kirschenbaum MA. Oxidative modification of low-density lipoprotein enhances the murine mesangial cell cytokines associated with monocyte migration, differentiation, and proliferation. Lab Invest. 1996;74:1067–1079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsche G, Zimmermann R, Horiuchi S, Tandon NN, Sattler W, Malle E. Class B scavenger receptors CD36 and SR-BI are receptors for hypochlorite-modified low density lipoprotein. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:47562–47570. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308428200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao L, Aw TY, Kvietys PR, Granger DN. Oxidized LDL-induced microvascular dysfunction: dependence on oxidation procedure. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:2305–2311. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.12.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Khoa T, Massy ZA, Witko-Sarsat V, Canteloup S, Kebede M, Lacour B, Drueke T, Descamps-Latscha B. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein induces macrophage respiratory burst via its protein moiety: a novel pathway in atherogenesis? Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;263:804–809. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr AC. Hypochlorous acid-modified low-density lipoprotein inactivates the lysosomal protease cathepsin B: protection by ascorbic and lipoic acids. Redox Rep. 2001;6:343–349. doi: 10.1179/135100001101536526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopprasch S, Leonhardt W, Pietzsch J, Kuhne H. Hypochlorite-modified low-density lipoprotein stimulates human polymorphonuclear leukocytes for enhanced production of reactive oxygen metabolites, enzyme secretion, and adhesion to endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis. 1998;136:315–324. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(97)00233-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuszkowski A, Grabner R, Marsche G, Unbehaun A, Malle E, Heller R. Hypochlorite-modified low density lipoprotein inhibits nitric oxide synthesis in endothelial cells via an intracellular dislocalization of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:14212–14221. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007659200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan MJ, Johnson G, Kirk J, Fuerstenberg SM, Zager RA, Torok-Storb B. HK-2: an immortalized proximal tubule epithelial cell line from normal adult human kidney. Kidney Int. 1994;45:48–57. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katrantzis M, Baker MS, Handley CJ, Lowther DA. The oxidant hypochlorite (OCl-), a product of the myeloperoxidase system, degrades articular cartilage proteoglycan aggregate. Free Radic Biol Med. 1991;10:101–109. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(91)90003-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malle E, Hazell L, Stocker R, Sattler W, Esterbauer H, Waeg G. Immunologic detection and measurement of hypochlorite-modified LDL with specific monoclonal antibodies. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:982–989. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.7.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen CD, Frach K, Schlondorff D, Kretzler M. Quantitative gene expression analysis in renal biopsies: a novel protocol for a high-throughput multicenter application. Kidney Int. 2002;61:133–140. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grone HJ, Cohen CD, Grone E, Schmidt C, Kretzler M, Schlondorff D, Nelson PJ. Spatial and temporally restricted expression of chemokines and chemokine receptors in the developing human kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:957–967. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V134957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid H, Henger A, Cohen CD, Frach K, Grone HJ, Schlondorff D, Kretzler M. Gene expression profiles of podocyte-associated molecules as diagnostic markers in acquired proteinuric diseases. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2958–2966. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000090745.85482.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond JR, Karnovsky MJ. Focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis: analogies to atherosclerosis. Kidney Int. 1988;33:917–924. doi: 10.1038/ki.1988.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grone EF, Walli AK, Grone HJ, Miller B, Seidel D. The role of lipids in nephrosclerosis and glomerulosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 1994;107:1–13. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(94)90136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joles JA, van Tol A, Jansen EH, Koomans HA, Rabelink TJ, Grond J, van Goor H. Plasma lipoproteins and renal apolipoproteins in rats with chronic adriamycin nephrosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1993;8:831–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malle E, Waeg G, Schreiber R, Grone EF, Sattler W, Grone HJ. Immunohistochemical evidence for the myeloperoxidase/H2O2/halide system in human atherosclerotic lesions: colocalization of myeloperoxidase and hypochlorite-modified proteins. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:4495–4503. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malle E, Buch T, Grone HJ. Myeloperoxidase in kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2003;64:1956–1967. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zager RA, Johnson AC, Hanson SY. Proximal tubular cholesterol loading after mitochondrial, but not glycolytic, blockade. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;285:F1092–1099. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00187.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal T, de Diego I, Kirchhoff MF, Tebar F, Heeren J, Rinninger F, Enrich C. High density lipoprotein-induced signaling of the MAPK pathway involves scavenger receptor type BI-mediated activation of Ras. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16478–16481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300085200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando RL, Varghese Z, Moorhead JF. Differential ability of cells to promote oxidation of low density lipoproteins in vitro. Clin Chim Acta. 1998;269:159–173. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(97)00199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbrecher UP. Role of superoxide in endothelial-cell modification of low-density lipoproteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;959:20–30. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(88)90145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal A, Nick HS. Renal response to tissue injury: lessons from heme oxygenase-1 gene ablation and expression. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:965–973. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V115965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otterbein LE, Choi AM. Heme oxygenase: colors of defense against cellular stress. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:L1029–1037. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.6.L1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwar YS. Heme oxygenase-1 in renal injury: conclusions of studies in humans and animal models. Kidney Int. 2001;59:378–379. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenhunen R, Marver HS, Schmid R. Microsomal heme oxygenase: characterization of the enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1969;244:6388–6394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal A, Balla J, Balla G, Croatt AJ, Vercellotti GM, Nath KA. Renal tubular epithelial cells mimic endothelial cells upon exposure to oxidized LDL. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:F814–823. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.271.4.F814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siow RC, Ishii T, Sato H, Taketani S, Leake DS, Sweiry JH, Pearson JD, Bannai S, Mann GE. Induction of the antioxidant stress proteins heme oxygenase-1 and MSP23 by stress agents and oxidised LDL in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. FEBS Lett. 1995;368:239–242. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00650-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker K, Gromer S, Schirmer RH, Muller S. Thioredoxin reductase as a pathophysiological factor and drug target. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:6118–6125. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powis G, BRiehl M, Oblong J. Redox signalling and the control of cell growth and death. Pharmacol Ther. 1995;68:149–173. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(95)02004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk H, Vogt M, Droge W, Schulze-Osthof K. Thioredoxin as a potent costimulus of cytokine expression. J Immunol. 1996;156:765–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S, Katoh T, Tetsuka T, Uno K, Matsui N, Okamoto T. Involvement of thioredoxin in rheumatoid arthritis: its costimulatory roles in the TNF-α induces production of IL-6 and IL-8 from cultured synovial fibroblasts. J Immunol. 1999;163:351–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villalba J, Navas P. Plasma membrane redox system in the control of stress-induced apoptosis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2000;2:213–230. doi: 10.1089/ars.2000.2.2-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towndrow KM, Mertens J, Jeong JK, Weber TJ, Monks TJ, Lau SS. Stress- and growth-related gene expression are independent of chemical-induced prostaglandin E2 synthesis in renal epithelial cells. Chem Res Toxicol. 2000;13:111–117. doi: 10.1021/tx990160s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J, Stevens J, Lau S, Monks T. Quinone thioether-mediated DNA damage, growth arrest and gadd153 expression in renal proximal tubular epithelial cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50:592–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigstock DR. Regulation of angiogenesis and endothelial cell function by connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) and cysteine-rich 61 (CYR61). Angiogenesis. 2002;5:153–165. doi: 10.1023/a:1023823803510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross MJ, Dixelius J, Matsumoto T, Claesson-Welsh L. VEGF-receptor signal transduction. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:488–494. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00193-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grone HJ, Simon M, Grone EF. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in renal vascular disease and renal allografts. J Pathol. 1995;177:259–267. doi: 10.1002/path.1711770308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]