Abstract

A substantial proportion of hitherto unexplained respiratory tract illnesses is associated with human metapneumovirus (hMPV) infection. This virus also was found in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). To determine the dynamics and associated lesions of hMPV infection, six cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) were inoculated with hMPV and examined by pathological and virological assays. They were euthanized at 5 (n = 2) or 9 (n = 2) days post-infection (dpi), or monitored until 14 dpi (n = 2). Viral excretion peaked at 4 dpi and decreased to zero by 10 dpi. Viral replication was restricted to the respiratory tract and associated with minimal to mild, multi-focal erosive and inflammatory changes in conducting airways, and increased numbers of macrophages in alveoli. Viral expression was seen mainly at the apical surface of ciliated epithelial cells throughout the respiratory tract, and less frequently in type 1 pneumocytes and alveolar macrophages. Both cell tropism and respiratory lesions were distinct from those of SARS-associated coronavirus infection, excluding hMPV as the primary cause of SARS. This study demonstrates that hMPV is a respiratory pathogen and indicates that viral replication is short-lived, polarized to the apical surface, and occurs primarily in ciliated respiratory epithelial cells.

A substantial proportion of hitherto unexplained respiratory tract illnesses in human beings is associated with infection by a recently discovered paramyxovirus, provisionally named human metapneumovirus (hMPV).1 It is most closely related to avian pneumovirus type C (APV), the etiological agent of rhinitis and sinusitis in turkeys.1,2 Human metapneumovirus was first identified in the Netherlands, where serological studies indicate that it has been circulating in the human population since at least 1958 and that most children are infected by 5 years of age.1 Since its discovery in the Netherlands, hMPV infection also has been reported elsewhere in Europe,3–7 North America,8,9 Asia,10,11 and Australia.12 Respiratory tract disease associated with hMPV infection occurs both in children and adults, suggesting that hMPV is capable of causing clinically important re-infection of individuals later in life.3,8 Clinically, hMPV-associated disease includes rhinitis, pharyngitis, bronchitis, bronchiolitis, and pneumonia, and resembles that of human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection.13 Severity of disease varies from common cold to death, with very young children, the elderly, and immunocompromised patients being predisposed to severe lower respiratory tract disease.13

In the recent epidemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), the role of hMPV as a primary pathogen or co-pathogen was considered.14 Although a newly discovered virus, SARS-associated coronavirus (SCV), proved to be the primary cause of the disease,15,16 12% (41 of 335) of SARS patients also were infected with hMPV,17 so that the role of hMPV as a co-pathogen cannot be ruled out at this time.

Until now, pathological confirmation that hMPV is a primary respiratory pathogen is lacking.18 Diagnosis of hMPV as the etiological agent of respiratory illness in the above studies was based on virus isolation, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), seroconversion to hMPV, or a combination of these methods, combined with the failure to detect other known respiratory pathogens. To characterize the virus excretion, virus distribution, and associated lesions of hMPV infection, and to determine whether they differ from those of SCV infection, we experimentally inoculated six cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) with the prototype hMPV isolate NL/1/002. They were euthanized at 5 (n = 2) or 9 (n = 2) days post-infection (dpi), or monitored until 14 dpi (n = 2). Here, we report the pathological, immunohistochemical, virological, serological, and molecular biological findings of this experiment.

Materials and Methods

Virus Preparation

The prototype hMPV isolate NL/1/002 was propagated three times on tertiary monkey kidney (tMK) cells and used to make a virus stock on tMK cells as previously described.1 Virus was harvested 7 dpi and frozen in 25% sucrose at −70°C. The infectious virus titer of this stock was 104.5 median tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) per ml by titration on tMK cells.

Experimental Protocol

Five days before infection, six juvenile cynomolgus macaques were placed in a negatively pressurized glove box in pairs of one male and one female. They were provided with commercial food pellets and water ad libitum. These macaques were colony-bred and had been maintained in group housing, where they were screened annually, and tested negative, for the following infections: simian virus 40, polyomavirus, tuberculosis, measles virus, mumps, simian immunodeficiency virus, simian retrovirus type D, and simian T-cell leukemia virus. Before infection, they were examined clinically and determined as healthy by a registered veterinarian. The macaques were infected with 5.0 × 104 TCID50 of hMPV, which was suspended in 5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Approximately 4 ml was applied intratracheally by use of a catheter, 0.5 ml on the tonsils, and 0.25 ml on each of the conjunctivae.

The macaques were observed daily for the occurrence of malaise, coughing, exudate from the eyes or nose, forced respiration, and any other signs of illness. Macaques No. 1 and No. 2 were euthanized at 5 dpi and macaques No. 3 and No. 4 at 9 dpi by exsanguination under ketamine anesthesia, while macaques No. 5 and No. 6 were monitored until 14 dpi. Macaques No. 5 and No. 6 were subsequently used for a follow-up experiment, not described here. The body temperatures of macaques No. 5 and No. 6 were measured by telemetry (IMAG, Wageningen, the Netherlands) every 3 minutes. To this end, a transponder was placed in their abdomens 30 days before inoculation.

Just before infection and daily from 2 dpi until euthanasia or 10 dpi, the macaques were anesthetized with ketamine and pharyngeal swabs were collected in 1 ml transport medium19 and stored at −70°C until RT-PCR and/or virus isolation. In addition, blood was collected from an inguinal vein just before infection in all macaques and at 14 dpi in macaques No. 5 and No. 6. Blood samples were collected in EDTA tubes and centrifuged at 2500 × g for 15 minutes, the plasma was collected and stored at −70°C until immunofluorescence assay. All animal procedures were approved by our institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Pathological Examination

Necropsies were carried out according to a standard protocol. Samples for histological examination were stored in 10% neutral-buffered formalin (lungs after inflation with formalin), embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4 μm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) for examination by light microscopy. The following tissues were examined by light microscopy: adrenal gland, brain stem, cerebellum, cerebrum, heart (left and right ventricle), kidney, larynx, lung (left and right, cranial, medial, and caudal lobes), liver, nasal septum (posterior section covered by respiratory epithelium), pancreas, primary bronchus (left and right), small intestine, spleen, stomach, tonsil, trachea, tracheo-bronchial lymph node, upper eyelid (left and right), and urinary bladder. Tissue sections of a clinically healthy juvenile male cynomolgus macaque that had not been infected with hMPV were used as a negative control.

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded, 4-μm thick sections of the same tissues examined by light microscopy were stained using an immunoperoxidase method. Tissue sections were mounted on coated slides (Klinipath, Duiven, the Netherlands), deparaffinized, rehydrated, and boiled for 15 minutes in citric acid buffer (10 mmol/L, pH 6.0) using a microwave oven. Endogenous peroxidase was revealed with 4-chloro-1-naphthol (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO), yielding a blue-black precipitate. Sections were subsequently washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (Fluka, Chemie AG, Buchs, Switzerland) and incubated with a polyclonal guinea pig antiserum (dilution 1:200) to hMPV prepared as described previously1 or with a negative control guinea pig serum for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing, sections were incubated with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled rabbit-anti-guinea pig Ig (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) for 1 hour at room temperature. HRP activity was revealed by incubating the sections in 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (Sigma Chemical Co.) solution for 10 minutes, resulting in a red precipitate. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tMK cells infected with hMPV were included as a positive control. Tissue sections of a clinically healthy juvenile male cynomolgus macaque that had not been infected with hMPV were used as a negative control. Selected lung sections were stained with monoclonal antibody AE1/AE3 (Neomarkers, Fremont, CA) for the identification of epithelial cells according to standard immunohistochemical procedures.

RT-PCR

Tissue samples of brain, heart, kidney, lung (cranial and caudal lobes), liver, nasal septum, primary bronchus, spleen, tonsil, trachea, and tracheo-bronchial lymph node were weighed and homogenized in minimal essential medium (10 ml per g tissue; Biowhittaker, Verviers, Belgium) by use of Potter tissue grinders (Fisher Scientific, ’s-Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands). The homogenates were incubated with lysis buffer (2 ml per ml homogenate; Roche Diagnostics, Almere, the Netherlands) containing proteinase K for 1 hour at room temperature, and RNA was isolated by use of a High Pure RNA Isolating kit (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, resulting in 50 μl RNA. RNA was isolated from 200 μl of transport medium from the pharyngeal swabs according to the same method. A Taqman real-time PCR developed in-house20 was performed in triplicate on 5 μl of isolated RNA from each sample, using serial dilutions of a titrated stock of the same virus as the calibration curve. The virus titer was expressed as TCID50 per mg tissue or ml transport medium from pharyngeal swabs.

Virus Isolation

Virus isolation on pharyngeal swabs was performed on Vero cells, clone 118, in the absence of fetal calf serum in the presence of 0.02% trypsin and 0.3% bovine albumin Fraction V (Invitrogen, Groningen, the Netherlands). The Vero-118 cell line, developed in-house, has equal susceptibility and sensitivity to all known genetic lineages of hMPV. The Vero-118 cells had been grown in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s medium (Biowhittaker) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Biowhittaker) and 2 mmol/L glutamine (Biowhittaker). The identity of the virus was confirmed by RT-PCR and automatic sequencing.21

Immunofluorescence Assay

Ninety-six-well plates coated with Vero-118 cells and infected with hMPV NL/1/00 were incubated with serial dilutions (up to 1:64) of plasma samples for 1 hour at 37°C. After washing with PBS, plates were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-human IgG (DAKO, 1:60) for 1 hour at 37°C. After washing with PBS and background staining with eriochrome black (Sigma Chemical Co.) for 1 minute, plates were read under an ultraviolet microscope. Non-infected Vero-118 cells were used as a negative control. Titers were expressed as the reciprocal of the last positive dilution.

Results

Clinical Findings

Rhinorrhea was seen in macaque No. 4 and No. 5 at 8 dpi. No clinical signs, including increased body temperatures in macaques No. 5 and No. 6, were seen in the other macaques.

Gross Pathology

Inspissated purulent exudate was present in the nasal cavity of macaques No. 2 and No. 4. In the former, the lining mucosa was reddened. Macaque No. 4 had aspirated food remains immediately before euthanasia and was excluded from further laboratory examination because histological lesions of hMPV infection were masked and aspirated debris reacted non-specifically by immunohistochemistry. No other gross lesions were seen in these two macaques or in the other macaques.

Histopathology

Macaques No. 1 to No. 3 had a mild rhinitis, characterized in the epithelium by loss of ciliation, architectural disruption, intra- and intercellular edema, and transmigration of a few neutrophils (Figure 1B). There was edema and infiltration with a few neutrophils in the underlying submucosa.

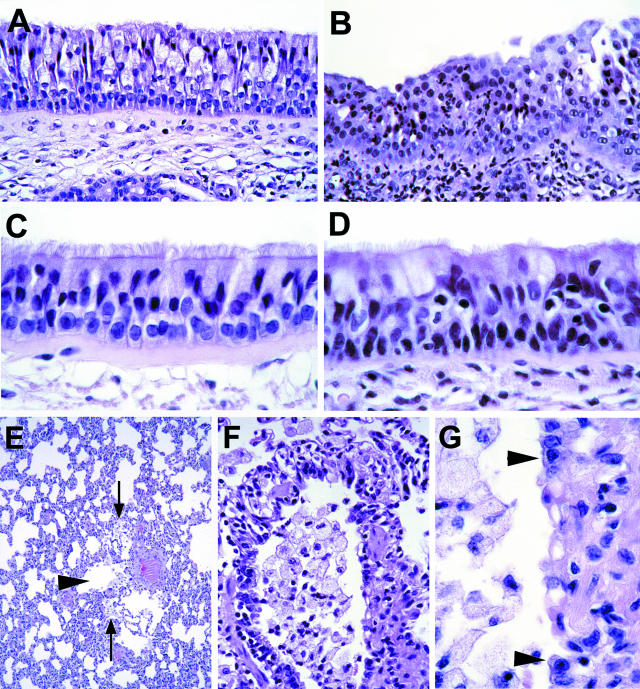

Figure 1.

Histopathology of experimental human metapneumovirus infection in cynomolgus macaques. A: Section of respiratory mucosa from nasal septum of negative control macaque. The pseudo-stratified epithelium consists of ciliated cells with cilia on apical surface, goblet cells with clear cytoplasm, and basal cells lying on the basement membrane. (H&E, original magnification, ×100). B: Section of respiratory mucosa from nasal septum of macaque No. 1. Suppurative rhinitis. There is loss of cilia, intercellular edema, architectural disruption, erosion, and infiltration with many neutrophils in the epithelium and submucosa. (H&E, original magnification, ×100). C: Section of tracheal mucosa of negative control macaque. The pseudo-stratified epithelium has the same constituent cells as in panel A. (H&E, original magnification, ×250). D: Tracheal section of macaque No. 1. Suppurative tracheitis. There is multi-focal loss of cilia, intercellular edema, architectural disruption, and infiltration with a few neutrophils in the epithelium and submucosa. (H&E, original magnification, ×250). E: Pulmonary section of macaque No. 3. Bronchiolitis. The bronchiolar lumen (arrowhead) is partly filled with macrophages. An increased number of macrophages also is present in alveolar lumina (arrows) adjacent to the bronchiole. (H&E, original magnification ×25). F: Pulmonary section of macaque No. 3. Erosive bronchiolitis. There is loss of bronchiolar epithelium, and the bronchiolar lumen is filled with macrophages. (H&E, original magnification, ×100). G: Pulmonary section of macaque No. 3. Erosive bronchiolitis. Detail of panel F. Cuboidal cells (arrowheads) line the bronchiolar wall. The bronchiolar wall in between the arrowheads is denuded. (H&E, original magnification, ×250).

All three macaques had minimal multi-focal lesions in the conducting airways, variable in extension from larynx to bronchioles (Table 1; Figure 1, D to G). Epithelial lesions consisted of loss of ciliation, architectural disruption, erosion, intercellular edema, and transmigration of neutrophils. There was infiltration with a few neutrophils in the underlying submucosa. The lumen of some bronchi contained a few sloughed ciliated epithelial cells admixed with scant cellular debris and mucus. The lumen of some bronchioles contained a few alveolar macrophages, rare multinucleated giant cells and neutrophils, admixed with scant cellular debris and fibrin. Similar material was present in the alveoli around affected bronchioles. No significant histological changes were seen in sections of other tissues examined. Above lesions were not seen in the tissues of the negative control macaque.

Table 1.

Microscopic Lesions and Presence of hMPV Antigen in Various Tissues of the Respiratory Tract of Cynomolgus Macaques Experimentally Infected with hMPV

| Macaque no. | Days post-infection | Evidence of lesions by histology (HI) or of hMPV by immunohistochemistry (IHC) or RT-PCR in the respiratory tract

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal septum

|

Trachea

|

Bronchus

|

Cranial lung

|

Caudal lung

|

||||||||||||

| HI | IHC | PCR | HI | IHC | PCR | HI | IHC | PCR | HI | IHC | PCR | HI | IHC | PCR | ||

| 1 | 5 | +* | + | 73 ± 9.5† | + | + | 377 ± 41 | + | + | 1675 ± 32 | + | + | 32 ± 9.3 | + | + | 73 ± 18 |

| 2 | 5 | + | + | 47 ± 5.8 | −‡ | − | 4 ± 1.7 | − | + | 98 ± 16 | + | + | 115 ± 30 | + | + | 68 ± 7.4 |

| 3 | 9 | + | − | 5 ± 2.3 | + | − | 0 ± 0.2 | − | − | 25 ± 7.8 | + | + | 45 ± 5.9 | + | + | 15 ± 7.5 |

Positive.

Mean ± standard deviation TCID50/mg tissue.

Negative.

Immunohistochemistry

Expression of hMPV occurred mainly in ciliated respiratory epithelium from the nasal cavity to the bronchioles in both macaques euthanized at 5 dpi, but not in the macaque euthanized at 9 dpi (Table 1; Figure 2, A to C). It occurred multi-focally in individual or groups of adjacent ciliated epithelial cells, and was seen both in morphologically normal (Figure 2B) and in degenerate or sloughed ciliated cells (Figure 2A). Expression of hMPV was visible as dark red staining of the cilia and apical plasma membrane, and diffuse lighter red staining of the cytoplasm. Neither goblet cells nor basal cells stained positively, even where they were located immediately adjacent to positively staining ciliated cells.

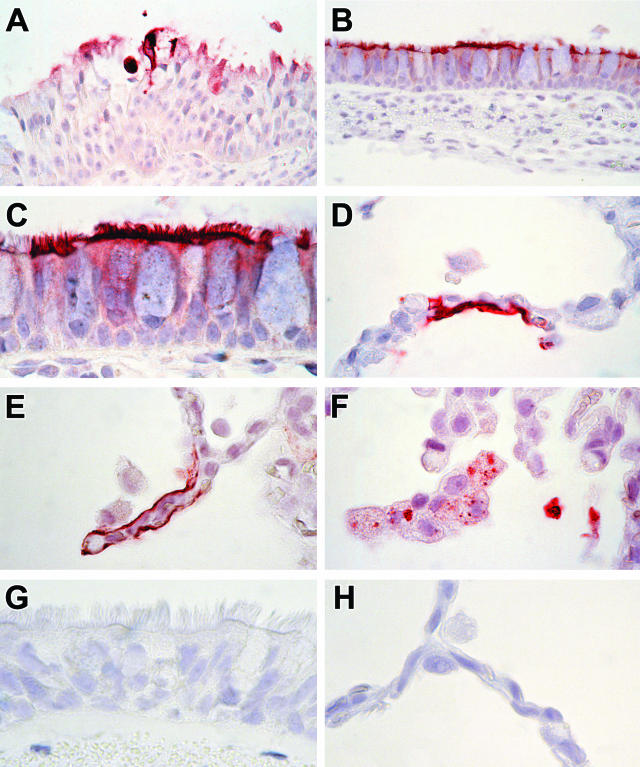

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemistry of experimental human metapneumovirus (hMPV) infection in cynomolgus macaques. A: Section of respiratory mucosa from nasal septum of macaque No. 2. Expression of hMPV occurs in the cytoplasm of degenerate epithelial cells and in cell debris. (Immunoperoxidase stain for hMPV, original magnification, ×100). B: Bronchial section of macaque No. 1. Expression of hMPV occurs in the cytoplasm of morphologically normal ciliated epithelial cells. (Immunoperoxidase stain for hMPV, original magnification, ×100). C: Bronchial section of macaque No. 1. Detail of panel B. Expression of hMPV is most pronounced in the cilia and apical plasma membrane of ciliated epithelial cells. Mucus cells and basal cells stain negative. (Immunoperoxidase stain for hMPV, original magnification, ×250). D and E: Pulmonary section of macaque No. 1. Expression of hMPV occurs diffusely in the cytoplasm of type 1 pneumocytes lining the alveolar walls. (Immunoperoxidase stain for hMPV, original magnification, ×250). F: Pulmonary section of macaque No. 1. Expression of hMPV occurs in the cytoplasm of alveolar macrophages and in intraluminal cell debris. Staining of alveolar macrophages is multi-focal and granular. (Immunoperoxidase stain for hMPV, original magnification, ×250). G: Bronchial section of negative control macaque. There is no expression of hMPV. (Immunoperoxidase stain for hMPV; original magnification, ×250). H: Pulmonary section of negative control macaque. There is no expression of hMPV. (Immunoperoxidase stain for hMPV, original magnification, ×250).

Expression of hMPV occurred occasionally in alveoli of all three macaques (Figure 2, D to F). It occurred multi-focally in type 1 pneumocytes, individual or small clusters of adjacent alveolar macrophages, and in intraluminal cellular debris. Expression in type 1 pneumocytes was visible as diffuse cytoplasmic staining (Figure 2, D and E). These cells were identified as type 1 pneumocytes because they lined the alveolar walls, were squamous, and expressed keratin in serial sections. In alveolar macrophages, it consisted of multiple distinct dark red granules in the cytoplasm (Figure 2F). Multinucleated giant cells did not stain positively. No positive staining was observed in any of the other tissues examined, nor in tissues of the negative control macaque (Figure 2, G and H).

RT-PCR and Virus Isolation

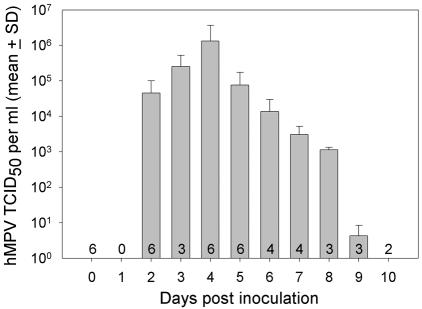

After an incubation period of 2 days at most, excretion of hMPV increased rapidly to a peak of 1.3 × 106 TCID50/ml at 4 dpi, and then decreased gradually to zero at 10 dpi (Figure 3). The results of RT-PCR were confirmed by virus isolation: hMPV was re-isolated from pharyngeal swabs collected at the peak of virus excretion of all six macaques.

Figure 3.

Pharyngeal excretion of human metapneumovirus by experimentally infected macaques. The numbers in the bars indicate the number of macaques sampled on each day.

At necropsy, hMPV was detected by RT-PCR throughout the respiratory tract, from the nasal cavity to the lungs, and virus titers were generally higher at 5 dpi than at 9 dpi (Table 1). The virus titers (mean ± SD TCID50 per mg tissue) in the tonsil (26 ± 6.4 in macaque No. 1, 14 ± 3.2 in macaque No. 2, and 0 in macaque No. 3) and tracheo-bronchial lymph node (192 ± 42 in macaque No. 1, 2.1 ± 0.7 in macaque No. 2, and 3.2 ± 2.5 in macaque No. 3) corresponded to this temporal pattern. Human metapneumovirus was not detected by RT-PCR in brain, heart, kidney, liver, or spleen of any of the macaques.

Immunofluorescence Assay

Before inoculation, anti-hMPV antibodies were not detected in plasma samples of any of the six macaques. At 14 dpi, both macaques No. 5 and No. 6 had seroconverted with an anti-hMPV antibody titer of ≥64.

Discussion

This experimental infection confirms that hMPV is a primary pathogen of the upper and lower respiratory tract in cynomolgus macaques. Clinical signs in hMPV-infected macaques were limited to rhinorrhea, and corresponded with a suppurative rhinitis at pathological examination. Additional histological lesions in the respiratory tract were minimal to mild erosive and inflammatory changes in mucosa and submucosa of conducting airways, and an increased number of alveolar macrophages in bronchioles and pulmonary alveoli. The close association between the respiratory lesions and the specific expression of hMPV antigen by immunohistochemistry, together with the absence of these lesions in the negative control tissues, support our conclusion that hMPV infection was the cause of these lesions.

Based on expression of hMPV by immunohistochemistry, viral replication in ciliated epithelial cells was widespread throughout the respiratory tract and more sporadic in type 1 pneumocytes. Viral antigen also was detected in alveolar macrophages, but the distinct granular character of cytoplasmic staining suggests phagocytosis of viral material rather than viral replication. The strong reduction in the distribution of hMPV-infected cells in the respiratory tract between 5 and 9 dpi (Table 1) corresponds with the reduction in viral excretion, as measured by RT-PCR, from the peak at 4 dpi to zero by 10 dpi (Figure 3). If possible, these immunohistochemical results should be substantiated with a larger number of animals. The absence of hMPV expression by immunohistochemistry in other tissues indicates that hMPV replication is restricted to the respiratory tract. The above conclusions were corroborated by the results of virus isolation and RT-PCR.

These findings substantiate the claim of van den Hoogen et al1 that hMPV infection causes respiratory tract illness in human beings. The subclinical or mild character of the disease associated with hMPV infection in these macaques corresponds to that in immunocompetent middle-age adults.13 Based on the ability of hMPV to replicate in the bronchioles and alveoli of cynomolgus macaques, one may expect more extensive viral replication and an associated increased severity of lesions in the lower respiratory tract of immunocompromised human beings, resulting in the severe bronchiolitis and pneumonia diagnosed clinically in such patients.22,23

The predominant tropism of hMPV for ciliated epithelial cells in the conducting airways and the mildness of the associated lesions, as seen in this study, contrasts with the predilection of SCV for alveolar epithelial cells and the severity of the associated pneumonia in SARS patients15,24–26 and experimentally infected macaques.16,17 These differences confirm that SCV and not hMPV is the primary etiological agent of SARS.

The pathogenesis of hMPV infection in macaques is similar in many ways to that of RSV in human beings, as far as it has been studied. As in hMPV, incubation period and excretion period are short, although RSV excretion may be prolonged in infants and immunocompromised individuals.27 Both initial infection and subsequent shedding of RSV are restricted to ciliated epithelial cells, based on an in vitro study using recombinant RSV expressing green fluorescent protein.28 Similar to the localization of RSV in that study, the results of immunohistochemistry in these macaques show that hMPV infection is polarized to the apical surface of ciliated respiratory epithelium. In immunocompetent individuals, the most common clinical manifestation of RSV infection is mild upper respiratory tract disease.29 However, viral distribution and associated lesions of this mild disease have not been reported. In very young or immunocompromised individuals, RSV replication occurs in epithelial cells of bronchus, bronchiole, and in alveolar macrophages,30,31 and is associated with severe bronchiolitis, interstitial pneumonia, or giant cell pneumonia.32 Although clinical studies indicate that hMPV infection may cause similar lesions in this category of patients, confirmation of fatal bronchiolitis or pneumonia from hMPV infection awaits pathological assessment of biopsy or autopsy samples.18

The pathogenesis of hMPV infection also is similar to that of APV, its closest known relative.2 As for hMPV infection in cynomolgus macaques, APV infection in turkeys has a short incubation and excretion period (2 and 8 days, respectively), occurs primarily in ciliated respiratory epithelial cells, and is associated with superficial erosive and inflammatory changes. In contrast to hMPV infection, APV antigen is not present in alveolar macrophages or alveolar walls. However, this difference may be explained, at least in part, by the intratracheal application of hMPV in macaques (this study) compared to the conjunctival and intranasal application of APV in experimentally infected turkeys.33

The results of this study provide the first characterization of the viral excretion, viral distribution and associated lesions of hMPV infection in cynomolgus macaques, and help to understand the pathology of this infection in human beings. The immunohistochemical method described above may be useful for retrospective analysis of respiratory tissues of human patients with respiratory disease of unknown viral origin, and to study the possible role of hMPV as a co-pathogen in patients with SARS.

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Dias d’Ullois, Frank van der Panne, and Dr. Guus Rimmelzwaan for assistance with animal care, figure preparation, and organization of the experiment, respectively.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Thijs Kuiken, Department of Virology, Erasmus Medical Center, P.O. Box 1738, 3000 DR Rotterdam, the Netherlands. E-mail: t.kuiken@erasmusmc.nl.

Supported in part by the Sophia Foundation for Medical Research. R.F. is a fellow of the Royal Dutch Academy of Arts and Sciences.

T.K. and B.G.V.D.H. contributed equally to this work.

References

- van den Hoogen BG, de Jong JC, Groen J, Kuiken T, de Groot R, Fouchier RAM, Osterhaus ADME. A newly discovered human pneumovirus isolated from young children with respiratory tract disease. Nat Med. 2001;7:719–724. doi: 10.1038/89098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Hoogen BG, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Analysis of the genomic sequence of a human metapneumovirus. Virol. 2002;295:119–132. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockton J, Stephenson I, Fleming D, Zambon M. Human metapneumovirus as a cause of community-acquired respiratory illness. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:897–901. doi: 10.3201/eid0809.020084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jartti T, van den Hoogen B, Garofalo RP, Osterhaus ADME, Ruuskanen O. Metapneumovirus and acute wheezing in children. Lancet. 2002;360:1393–1394. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11391-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freymouth F, Vabret A, Legrand L, Eterradossi N, Lafay-Delaire F, Brouard J, Guillois B. Presence of the new human metapneumovirus in French children with bronchiolitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:92–94. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200301000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggi F, Pifferi M, Vatteroni M, Fornai C, Tempestini E, Anzilotti S, Lanini L, Andreoli E, Ragazzo V, Pistello M, Specter S, Bendinelli M. Human metapneumovirus associated with respiratory tract infections in a 3-year study of nasal swabs from infants in Italy. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:2987–2991. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.7.2987-2991.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viazov S, Ratjen F, Scheidhauer R, Fiedler M, Roggendorf M. High prevalence of human metapneumovirus infection in young children and genetic heterogeneity of the viral isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:3043–3045. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.7.3043-3045.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peret TCT, Boivin G, Li Y, Couillard M, Humphrey C, Osterhaus ADME, Erdman DD, Anderson LJ. Characterization of human metapneumoviruses isolated from patients in North America. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:1660–1663. doi: 10.1086/340518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esper F, Boucher D, Weibel C, Martinello RA, Kahn JS. Human metapneumovirus infection in the United States: clinical manifestations associated with a newly emerging respiratory infection in children. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1407–1410. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.6.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiris JS, Tang WH, Chan KH, Khong PL, Guan Y, Lau YL, Chiu SS. Children with respiratory disease associated with metapneumovirus in Hong Kong. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:628–633. doi: 10.3201/eid0906.030009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebihara T, Endo R, Kikuta H, Ishiguro N, Yoshioka M, Ma X, Kobayashi K. Seroprevalence of human metapneumovirus in Japan. J Med Virol. 2003;70:281–283. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissen MD, Siebert DJ, Mackay IM, Sloots TP, Withers SJ. Evidence of human metapneumovirus in Australian children. Med J Aust. 2002;176:188. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Hoogen BG, Osterhaus ADME, Fouchier RAM. Clinical impact and diagnosis of hMPV infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:525–532. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000108190.09824.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poutanen SM, Low DE, Henry B, Finkelstein S, Rose D, Green K, Tellier R, Draker R, Adachi D, Ayers M, Chan AK, Skowronski DM, Salit I, Simor AE, Slutsky AS, Doyle PW, Krajden M, Petric M, Brunham RC, McGeer AJ. Identification of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Canada. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1995–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiris JS, Lai ST, Poon LL, Guan Y, Yam LY, Lim W, Nicholls J, Yee WK, Yan WW, Cheung MT, Cheng VC, Chan KH, Tsang DN, Yung RW, Ng TK, Yuen KY. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1319–1325. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouchier RA, Kuiken T, Schutten M, van Amerongen G, Van Doornum GJ, van den Hoogen BG, Peiris M, Lim W, Stöhr K, Osterhaus AD. Aetiology: Koch’s postulates fulfilled for SARS virus. Nature. 2003;423:240. doi: 10.1038/423240a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiken T, Fouchier RA, Schutten M, Rimmelzwaan GF, van Amerongen G, van Riel D, Laman JD, de Jong T, van Doornum G, Lim W, Ling AE, Chan PK, Tam JS, Zambon MC, Gopal R, Drosten C, van der WS, Escriou N, Manuguerra JC, Stohr K, Peiris JS, Osterhaus AD. Newly discovered coronavirus as the primary cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;362:263–270. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13967-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin G, Abed Y, Pelletier G, Ruel L, Moisan D, Côté S, Peret TCT, Erdman DD, Anderson LJ. Virological features and clinical manifestations associated with human metapneumovirus: a new paramyxovirus responsible for acute respiratory-tract infections in all age groups. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:1330–1334. doi: 10.1086/344319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouchier RA, Bestebroer TM, Herfst S, Van Der Kemp L, Rimmelzwaan GF, Osterhaus AD. Detection of influenza A viruses from different species by PCR amplification of conserved sequences in the matrix gene. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:4096–4101. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.11.4096-4101.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maertzdorf J, Wang CK, Brown JB, Quinto JD, Chu M, De Graaf M, van den Hoogen BG, Spaete R, Osterhaus ADME, Fouchier RAM. A real-time RT-PCR assay for the detection of human metapneumoviruses from all known genetic lineages. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:981–986. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.3.981-986.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Hoogen BG, Van Doornum GJ, Fockens JC, Cornelissen JJ, Beyer WE, Groot RR, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Prevalence and clinical symptoms of human metapneumovirus infection in hospitalized patients. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:1571–1577. doi: 10.1086/379200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier G, Déry P, Abed Y, Boivin G. Respiratory tract re-infections by the new human metapneumovirus in an immunocompromised child. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:976–978. doi: 10.3201/eid0809.020238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cane PA, van den Hoogen BG, Chakrabarti S, Fegan CD, Osterhaus AD. Human metapneumovirus in a haematopoietic stem cell transplant recipient with fatal lower respiratory tract disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;31:309–310. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ksiazek TG, Erdman D, Goldsmith C, Zaki SR, Peret T, Emery S, Tong S, Urbani C, Comer JA, Lim W, Rollin PE, Dowell SF, Ling AE, Humphrey CD, Shieh WJ, Guarner J, Paddock CD, Rota P, Fields B, DeRisi J, Yang JY, Cox N, Hughes JM, LeDuc JW, Bellini WJ, Anderson LJ. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1953–1966. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls JM, Poon LLM, Lee KC, Ng WF, Lai ST, Leung CY, Chu CM, Hui PK, Mak KL, Lim W, Yan KW, Chan KH, Tsang NC, Guan Y, Yuen KY, Peiris JSM. Lung pathology of fatal severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1773–1778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13413-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks TJ, Chong PY, Chui P, Galvin JR, Lourens RM, Reid AH, Selbs E, McEvoy CP, Hayden CD, Fukuoka J, Taubenberger JK, Travis WD. Lung pathology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): a study of 8 autopsy cases from Singapore. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:743–748. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(03)00367-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craighead JE. Influenza viruses. San Diego: Academic Press; Pathology and Pathogenesis of Human Viral Disease. 2000:pp 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Peeples ME, Boucher RC, Collins PL, Pickles RJ. Respiratory syncytial virus infection of human airway epithelial cells is polarized, specific to ciliated cells, and without obvious cytopathology. J Virol. 2002;76:5654–5666. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.11.5654-5666.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn WC, Jr, Walker DH. Viral infections. Pulmonary Pathology. Dail DH, Hammar SP, editors. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1994:pp 429–464. [Google Scholar]

- Neilson KA, Yunis EJ. Demonstration of respiratory syncytial virus in an autopsy series. Pediatr Pathol. 1990;10:491–502. doi: 10.3109/15513819009067138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siani V, Netter J-C, Gorguet B, Carles D, Pellegrin de Villeneuve M. Mise en évidence du virus respiratoire syncytial par méthode immuno-histochimique: à propos de 53 cas de mort subite du nourrisson. Ann Pathol. 1999;19:99–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RR. Viral infections of the respiratory tract. Pathology of the Lung. Thurlbeck WM, Churg AM, editors. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 1995:pp 195–222. [Google Scholar]

- Jirjis FF, Noll SL, Halvorson DA, Nagaraja KV, Shaw DP. Pathogenesis of avian pneumovirus infection in turkeys. Vet Pathol. 2002;39:300–310. doi: 10.1354/vp.39-3-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]