Abstract

Acquired or inherited junctional epidermolysis bullosa are skin diseases characterized by a separation between the epidermis and the dermis. In inherited nonlethal junctional epidermolysis bullosa, genetic analysis has identified mutations in the COL17A1 gene coding for the transmembrane collagen XVII whereas patients with acquired diseases have autoantibodies against this protein. This suggests that collagen XVII participates in the adhesion of basal keratinocytes to the extracellular matrix. To test this hypothesis, we studied the behavior of keratinocytes with null mutations in the COL17A1 gene. Initial adhesion of mutant cells to laminin 5 was comparable to controls and similarly dependent on α3β1 integrins. The spreading of mutant cells was, however, enhanced, suggesting a propensity to migrate, which was confirmed by migration assays. In addition, laminin 5 deposited by collagen XVII-deficient keratinocytes was scattered and poorly organized, suggesting that correct integration of laminin 5 within the matrix requires collagen XVII. This assumption was supported by the co-distribution of the two proteins in the matrix of normal human keratinocytes and by protein-protein-binding assays showing that the C-terminus of collagen XVII binds to laminin 5. Together, the results unravel an unexpected role of collagen XVII in the regulation of keratinocyte migration.

Collagen XVII (or BPAG2, 180-kd bullous pemphigoid antigen) is expressed by epithelial cells forming hemidesmosomes (HDs), such as basal keratinocytes in skin or mucosa. HDs are multiprotein complexes connecting the intracellular keratin network to anchoring filaments and fibrils located in the basement membrane (BM) and the upper dermis, respectively.1 Collagen XVII is expressed as a transmembrane full-length entity that is in part converted to an extracellular protein by shedding.2–4 Because the full-length protein is anchored in a type II orientation in the plasma membrane, its N-terminus is intracellular and the C-terminus, or ectodomain, is extracellular. The intracellular domain of collagen XVII is located in the cytoplasmic plaque of HDs where it co-localizes and interacts with the intracellular tail of the integrin β4 subunit, BPAG1 (230-kd bullous pemphigoid antigen) and HD1/plectin,5 which in turn acts as a molecular bridge to the keratin-based cytoskeleton.1 A further interaction occurs between extracellular stretches adjacent to the transmembrane domains of collagen XVII and integrin α6 subunit.6

The collagen XVII ectodomain is located in the anchoring filaments extending from the HDs and spanning the lamina lucida to reach the lamina densa.7 There it co-localizes with laminin 5, the extracellular ligand for the α6β4 integrin.8 The ectodomain comprises three identical subunits containing 15 collagenous sequences interspaced by 16 noncollagenous segments9 assembled into a 60- to 70-nm N-terminal rod and a 100- to 130-nm C-terminal flexible tail.7,10 The function of the ectodomain is still elusive although clinical, immunological, and genetic studies suggest that it participates in the adhesion of basal keratinocytes to the extracellular matrix (ECM). Patients with bullous pemphigoid, an acquired disorder, have autoantibodies against the ectodomain and are prone to subepidermal blistering.11 Mutations in the COL17A1 gene leading to either absence of collagen XVII12,13 or expression of a structurally altered protein14 are associated with nonlethal junctional epidermolysis bullosa (nJEB), a disorder also characterized by subepidermal blistering and immature HDs.12,13 In contrast, deletion of the collagen XVII cytoplasmic domain leads to epidermolysis bullosa simplex, ie, disruption within the basal keratinocytes, while the BM and the anchoring filaments remain structurally normal.15

Based on these observations, the collagen XVII ectodomain is predicted to play a role in the anchorage of basal keratinocytes to the BM and in the stability of the dermal-epidermal junction. However, the potential ligand(s) and the function of the ectodomain remain to be characterized. To address these issues, we used several functional assays to compare the behavior of collagen XVII-deficient (C17−/−) keratinocytes from nJEB patients to that of normal human keratinocytes (NHKs). Further, we tested recombinant fragments of collagen XVII in binding assays to laminins. Our results do not support the prediction that collagen XVII is a true cell-matrix receptor, however, they reveal that an important function of the ectodomain is to bind laminin 5 and to regulate the mobility and the anchorage of basal keratinocytes.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Mutation Analysis

Human samples were obtained from individuals with their or their parent’s informed consent. Mutation screening of the COL17A1 gene was performed using polymerase chain reaction amplification of all exons from genomic DNA isolated from peripheral blood and heteroduplex analysis by conformation sensitive gel electrophoresis.16 For screening of the mutations, the following primers were used for polymerase chain reaction amplification of exon 8: sense primer 5′-TCAGCCTAAAGGTCCATCTG-3′ and anti-sense primer 5′-AGCACTAGCCCTGGAAATCT-3′. Heteroduplex forming polymerase chain reaction products were subjected to automated sequencing. Mutation analysis of P2 and P3 has been performed with the same methods and described elsewhere.17,18

Cell Cultures

Primary keratinocyte cultures were initiated from skin biopsies and maintained in low-calcium, serum-free, keratinocyte growth medium as described.19 At subconfluency, keratinocytes were harvested using 0.05% trypsin and 0.02% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4. The spent culture media were collected and kept at −20°C in the presence of protease inhibitors. Cells in the second and third passages were used for experiments. Daily monitoring of the cultures did not reveal differences in proliferation and adhesion of controls and patients’ keratinocytes.

Immunofluorescence

Skin cryosections were fixed in methanol at −20°C and keratinocytes grown on glass coverslips for 3 days were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 1 minute. Antibodies (Abs) used for stainings were mouse monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) BM165 and 6F12 against human laminin α3 and β3 chains, respectively (a gift from Dr. RE Burgeson, Cutaneous Biology Research Center, Boston, MA); P1B5, P4C10, and 3E1 (all from Chemicon, Hofheim, Germany) against human integrin α3, β1, or β4 chains; rat mAbs GoH3 (Chemicon) or 9EG7 (a gift from Dr. D Vestweber, University of Münster, Münster, Germany) against integrin α6 and β1 subunits, respectively; and rabbit NC16a Ab against collagen XVII. Fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled second Abs (Dianova, Hambourg, Germany) were used alone whereas Cy3-conjugated second Abs (Jackson, distributed through Dianova) were applied together with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated phalloidin (Sigma-Aldrich, Deisenhofen, Germany). For triple immunofluorescence staining of cells, rabbit NC16a was applied first, followed by Cy3-conjugated donkey Abs against rabbit Igs, and then by mouse mAb BM165 followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat Abs against mouse Igs together with phalloidin-coumarin-phenyl isothiocyanate (Sigma-Aldrich). Staining was analyzed by light microscopy with epifluorescence optics or by confocal laser or two photon-scanning microscopy (Leica Instruments).

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Immunoblotting

Proteins released in the culture medium were precipitated with chloroform/methanol or ethanol. The cell layers were directly resuspended in Laemmli buffer or extracted with either 1% Nonidet P-40 in 0.1 mol/L NaCl, 20 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, containing protease inhibitors2 or by three incubations (10 minutes each) with 0.5% sodium deoxycholate in 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. The substratum-attached, detergent-insoluble material was suspended using a rubber policeman into 1% SDS-PAGE buffer containing 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, immunoblotted with rabbit Abs to subdomains of collagen XVII or with mAbs BM165 or D4B5 (Chemicon) against laminin α3 and γ2 chains, respectively, and Ab sc7651 (Santa Cruz, Heidelberg, Germany) against the laminin β3 chain followed by appropriate alkaline phosphatase-conjugated (Sigma Aldrich) or horseradish peroxidase-conjugated (DAKO) Igs.

Cell Adhesion Assays

Tissue culture wells (96-well plates; Costar, Bodenheim, Germany) were coated with laminin-nidogen complex (20 μg/ml), referred hereafter as laminin 1, purified from the mouse Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm tumor (kindly provided by Dr. R Timpl, Max-Planck Institute for Biochemistry, Martinsried, Germany), collagen IV (5 μg/ml) extracted from human placenta (kindly provided by Dr. K Kühn, Max-Planck Institute for Biochemistry, Martinsried, Germany) and laminin 5 (2 μg/ml) purified from the cell culture medium of NHKs or SCC25 cells by affinity chromatography as previously reported.20 Stained SDS-PAGE gels, immunoblotting and MALDI-TOF/mass spectrometry indicated >95% purity and semiprocessing of laminin 5 (165 kd for α3, 140 kd for β3, 155 and 105 kd for γ2 chains). After saturation of the wells with 1% bovine serum albumin (Fraction V, Sigma-Aldrich), equal numbers of NHKs and C17−/− keratinocytes were directly seeded in coated triplicate wells for 30 minutes according to a previously reported protocol.20 For integrin inhibition experiments, mAb P4C10 against β1 or P1B5 against α3 (Chemicon) were added to the assay medium. At the end of the experiments, adherent cells were fixed, stained with crystal violet, and quantified using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader as previously reported.20 To quantify spreading, photographs of the adherent cells were taken under phase contrast microscopy and round (no cytoplasm visible) and spread cells (identified by a distinct cytoplasm) were counted. For each assay point, at least 200 cells were counted.

Cell Migration Assays

Equal numbers of NHKs and C17−/− keratinocytes were seeded on duplicate wells (24-well plates, Costar) coated with laminin 5. After 2.5 hours the cell monolayers were wounded by a scratch with a pipette tip. Photographs of the wound margins were taken immediately and after 2 and 5 hours at an identical position along the scratch. The distance covered by the cells into the denuded area was measured at five different positions on each photograph. The migration was expressed in arbitrary units (distance covered in 5 hours expressed as cm on photographs; mean of 10 measurements). In another assay, drops (10 μl) containing equal numbers of NHKs and C17−/− keratinocytes were deposited in the center of wells (one drop/well) to produce small colonies of confluent cells. After 60 minutes the wells were filled with keratinocyte growth medium and photographs were taken immediately (T0) and every 2 hours up to 8 hours at the border of the colonies. The number of cells that had emigrated from the colonies was counted on the photographs.

Recombinant Fragments of Collagen XVII

Two recombinant fragments of human collagen XVII were expressed in eukaryotic cells. One, rCol15, contains the 241 residues (amino acids 567 to 807) of the Col15 domain.21 The second, rEcto2, spans the 324 most distal C-terminal residues (amino acids 1175 to 1497). The corresponding cDNA was amplified by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction from mRNA of NHKs, cloned into a modified episomal expression vector pCEP-4 (InVitrogen, Leek, The Netherlands) and used to stably transfect human kidney 293-EBNA cells. Cell transfection, selection, and expansion were performed as previously described for rCol15.21 For harvesting, 50 μg/ml of ascorbate (Fluka, Deisenhofen, Germany) was added every 24 hours. The media was collected every 48 hours and enriched in the recombinant fragment by DEAE-cellulose chromatography. After elution with a linear gradient of 0 to 0.6 mol/L NaCl, the fractions containing the 38-kd recombinant polypeptide were identified by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining of the gels or immunoblotting with Ab-Ecto3. The collagenous nature of rEcto2 was confirmed by digestion at 37°C for 2 hours with 40 U/ml of highly purified bacterial collagenase (Advanced Biofactures Inc., Lynbrook, NY). Overnight treatment of rEcto2 with 10 U/ml N-glycosidase F (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) at 37°C resulted in a 3-kd shift in the electrophoretic migration, indicating correct glycosylation of the fragment.

Protein-Protein-Binding Assays

ELISA titration and protein-binding assays followed a previously described protocol.22 For ELISA titration, 96-well plates were coated with laminins or recombinant fragments (0.5 μg/well). After blocking unspecific binding sites with 1% bovine serum albumin, serial dilutions of domain-specific Ab Ecto3 and Ab Col15-2 were applied, followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated second Abs (DAKO) and tetramethylbenzidine as color reagent. For protein-protein-binding assays, wells coated with laminins and postcoated with 1% bovine serum albumin were incubated overnight at 4°C with rEcto2 or rCol15 diluted in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin. After extensive washing with 0.5% Tween in PBS, rEcto2 or rCol15 fragments retained by specific binding to the coated proteins were detected by ELISA using Ab Ecto3 and Ab Col15-2, respectively, at a 1:1000 dilution.

Results

Identification of Keratinocytes with Mutations in the COL17A1 Gene

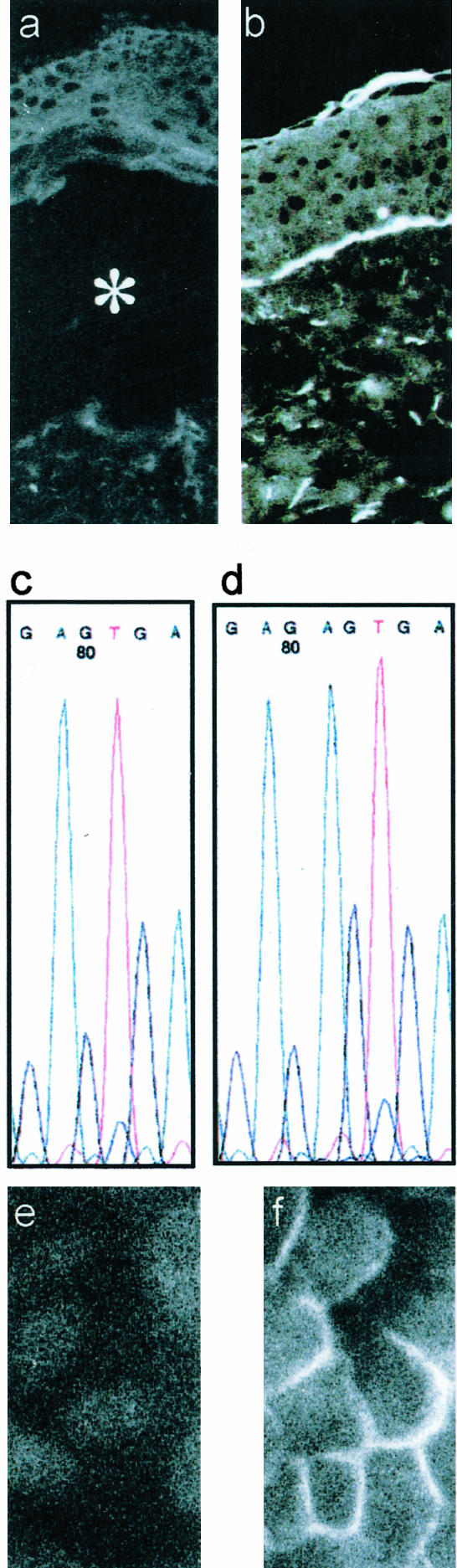

Skin biopsies from patients with nonlethal epidermolysis bullosa were immunostained with a panel of Abs against hemidesmosomal and BM proteins. As shown for patient 1 (P1), staining of collagen XVII was negative (Figure 1a). The distribution of other proteins in spontaneous blisters was typical of junctional epidermolysis bullosa, ie, tissue separation along the lamina lucida with the α6 and β4 integrin subunits, keratins 5 and 14, BP230, and plectin in the blister roof; and laminin α3, β3, and γ2 chains, collagens IV and VII, and nidogen in the blister floor (not shown). Mutation screening of the COL17A1 gene of P1 revealed the homozygous mutation 520delAG (Figure 1c). With the same protocol, we previously identified the two other nJEB patients included in this study. Patient 2 (P2) is compound heterozygous for mutations R1226X/L855X18 and patient 3 (P3) is homozygous for the mutation R1226X.17 All mutations led to premature termination codons.

Figure 1.

Characterization of C17−/− keratinocytes. Immunostaining of collagen XVII with Ab NC16a is negative in the skin of P1 (a) whereas it is positive in normal human skin (b). In a the asterisk denotes the blister cavity. Analysis of genomic DNA of P1 showed a homozygous 2-bp deletion at nucleotide position 520, 520delAG, of the COL17A1 gene XVII (c). The normal sequence is shown in d. Immunofluorescence staining of keratinocytes from P1 shows lack of collagen XVII expression (e), whereas the NC16a Ab decorates the plasma membrane of NHKs (f).

Keratinocytes were cultured from skin biopsies of P1, P2, and P3. Immunostaining with Ab NC16a against collagen XVII was negative for the patients’ cells (Figure 1e), whereas NHKs were labeled (Figure 1f). Immunoblotting of the culture medium and cell extracts with different collagen XVII Abs confirmed absence of the protein in the keratinocyte cultures of P1, P2, and P3 (not shown),17,18 whereas both the full-length and shed forms of collagen XVII were present in NHKs.

Enhanced Spreading of C17−/− Keratinocytes

The role of α3β1 integrins in the initial adhesion of NHKs to laminin 5 has been established.20,23 To test the prediction that collagen XVII could also participate in the process, we compared C17−/− keratinocytes to NHKs in short-term adhesion assays on laminins 1 and 5. The adhesion of C17−/− keratinocytes was equivalent to that of NHKs on both tested proteins and was inhibited to the same extent by the function-blocking mAb P4C10 against β1 integrins (Figure 2). The involvement of α3β1 integrins was more precisely analyzed by using a mAb against the integrin α3 subunit, which prevented the adhesion of C17−/− keratinocytes and NHKs to laminin 5 (Figure 3, a and c) but not to collagen IV (Figure 3, b and d) used as a negative control. Thus, the initial adhesion of both C17−/− keratinocytes and NHKs to laminin 5 is similarly dependent on α3β1 integrins.

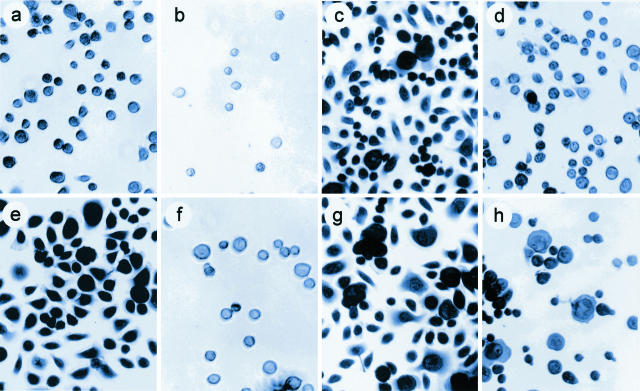

Figure 2.

Adhesion and spreading of C17−/− keratinocytes and NHKs. NHKs (a–d) and keratinocytes from P1 (e–h) were seeded on laminin 1 (a, b, e, f) or laminin 5 (c, d, g, h) in the presence (b, f, d, h) or absence (a, e, c, g) of mAb P4C10 against the integrin β1 subunit (1:1000 dilution). After 30 minutes of adhesion, adherent cells were fixed, stained, and photographed as described in Materials and Methods. Note that in all cases mAb P4C10 inhibits cell adhesion.

Figure 3.

Adhesion of C17−/− keratinocytes to laminin 5 is mediated by α3β1 integrins. C17−/− keratinocytes from P2 (a, b) and NHKs (c, d) were seeded on laminin 5 (a, c) or collagen IV (b, d) in the absence (white columns) or presence of function-blocking Abs against β1 (black columns) or α3 (hatched columns) integrins. After 30 minutes, adherent cells were fixed, stained, and the extent of adhesion was measured by color reading as described in Materials and Methods. Adhesion to laminin 5 of NHKs and C17−/− keratinocytes is inhibited by mAbs against β1 (clone P4C10,1:500) or α3 (clone P1B5, 1:400) integrins. Adhesion to collagen IV is inhibited by P4C10 only. The values represent the average of triplicate wells ± SEM.

Adherent C17−/− keratinocytes were, however, remarkably flatter and larger than NHKs because they displayed more lamellipodia (Figure 4). A quantitative analysis showed that the spreading of C17−/− cells was more pronounced than that of NHKs, in particular on laminin 1 (P1 and P2, Table 1). Thus, absence of collagen XVII improves the spreading rather than reduces the attachment of keratinocytes.

Figure 4.

C17−/− keratinocytes display more lamellipodias than NHKs. NHKs (a–c) and C17−/− keratinocytes from P2 (d–f) were seeded on laminin 1 (a, d), laminin 5 (b, e), or collagen IV (c, f). After 30 minutes of adhesion, adherent cells were fixed, stained, and photographed under phase contrast microscopy. Compared to NHKs (top), most C17−/− keratinocytes (bottom) form lamellipodia.

Table 1.

Spreading of C17−/− Keratinocytes and NHKs on Laminin 1 and Laminin 5

| Cells | Spread keratinocytes (in %) on

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Laminin 1 | Laminin 5 | |

| C17−/− (patient 1) | 80.55 ± 2.85 | 83.07 ± 4.28 |

| NHK (control 1) | 54.75 ± 6.26 | 72.60 ± 2.57 |

| C17−/− (patient 2) | 82.69 ± 3.54 | 91.92 ± 2.17 |

| NHK (control 2) | 59.16 ± 1.93 | 92.01 ± 3.01 |

Keratinocytes were counted on photographs as those shown in Figures 2 and 4. Cells with or without a distinct cytoplasm were counted as spread or not spread, respectively. The values (mean ± SEM) express the percent of spread cells out of at least 200 cells/field.

C17−/− Keratinocytes Are More Motile than NHKs

Lamellipodia are dynamic structures governing cell spreading and migration and their presence is characteristic of motile cells.24 To test whether the morphology displayed by C17−/− keratinocytes is related to a motile phenotype, migration assays were performed with NHKs and keratinocytes of P2 that were available in sufficient amounts. In in vitro wound healing assays, the C17−/− keratinocytes repopulated the wound faster than NHKs (Figure 5; a to c). Another assay was used to measure cell scattering. To that end, NHKs and C17−/− keratinocytes were seeded as small colonies and migration of the cells out of the colonies was monitored (Figure 5, d and e). Compared to NHKs, larger numbers of C17−/− keratinocytes escaped the colonies (Figure 5f), indicating again that keratinocytes lacking collagen XVII are more motile than control cells.

Figure 5.

C17−/− keratinocytes are more motile than NHKs. a–c: In vitro wound closure assays. NHKs (a) and C17−/− keratinocytes from P2 (b) were seeded at the same density on duplicate wells coated with laminin 5. After 2.5 hours a scratch was made in the monolayers and photographs of the wound edge were taken immediately (T0) and after 2 (T2) and 5 hours (T5). The dotted line indicates the position of the wound margin at T0. c: The migration of NHKs (white columns) and C17−/− keratinocytes (black columns) was measured on photographs and expressed in arbitrary units (distance covered by the cells between photographs T0 and T5; mean of 10 measurements ± SEM). The results are shown for two experiments (experiment 1 and experiment 2) performed on different days. d–f: Scattering assays. Equal numbers of NHKs (d) and C17−/− keratinocytes from P2 (e) were seeded as small colonies in the center of tissue culture wells. After 60 minutes the wells were filled with keratinocyte growth medium and photographs of the colony margins were taken immediately (T0) and after 2, 4, 6, and 8 hours (T8). The dotted line marks the margin of the colonies at T0. f: The number of cells that had emigrated from three individual colonies of NHKs (open circles) and C17−/− keratinocytes (filled circles) was counted on photographs taken at different times after onset of the experiment as indicated. Both assays were repeated on 2 consecutive days.

Targeting of α6β4 Integrins to Cell-Matrix Contacts in C17−/− Keratinocytes

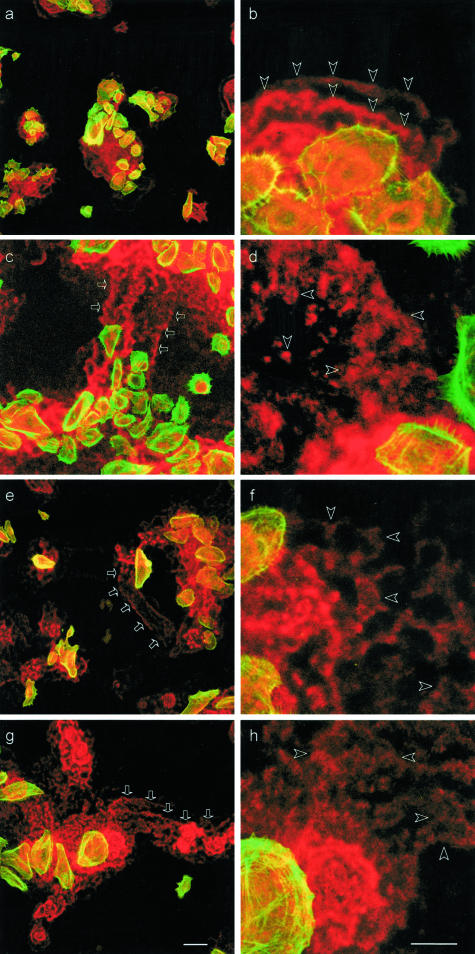

In vitro analysis has shown that anchorage of NHKs to laminin 5 is a sequential process. It requires first the engagement of α3β1 integrins in transient focal adhesions subsequently replaced by HD-like structures involving α6β4 integrins.25,26 To determine whether α6β4 integrin-mediated adhesions are formed in the absence of collagen XVII, the two integrin subunits were labeled by indirect immunofluorescence. Analysis of the stainings by confocal laser-scanning microscopy revealed that, as in NHKs, the α6 and β4 subunits are targeted to the basal surface of C17−/− keratinocytes (Figure 6). However, while for NHKs the two subunits are concentrated and confined to areas underneath or close to the cell bodies (Figure 6, a and b), for C17−/− keratinocytes they are not restricted to these areas and they are scattered over the culture support (Figure 6; c to h). Staining of the integrin α3 and β1 subunits also showed a scattered pattern for the C17−/− keratinocytes (not shown). This is typical of motile cells that leave integrin trails where they had resided before27–29 and confirm the results obtained in migration assays. Thus, targeting of α6β4 integrins to cell-matrix adhesions is not sufficient to confer a stationary phenotype to C17−/− keratinocytes.

Figure 6.

The α6β4 integrin is targeted to cell-matrix contacts in both C17−/− keratinocytes and NHKs. Immunostainings for β4 (a, c, e, g) or α6 (b, d, f, h) integrins (in red) are positive in NHKs (a, b) and keratinocytes from nJEB patients (P1, c and d; P2, e and f; P3, g and h). Labeling of fibrillar actin (superimposed green) was used to delineate cell bodies. The stainings were observed with a laser confocal microscope at the plane of cell-substrate contacts. In NHK, the β4 (a) and α6 (b) integrins are restricted to patches underneath or in the vicinity of cell bodies. For keratinocytes of nJEB patients (c–h), both subunits are targeted to cell-matrix adhesions underneath the cells and, in addition, integrin remnants are scattered on the culture support. Scale bar, 50 μm.

C17−/− Keratinocytes Do Not Correctly Organize Laminin 5

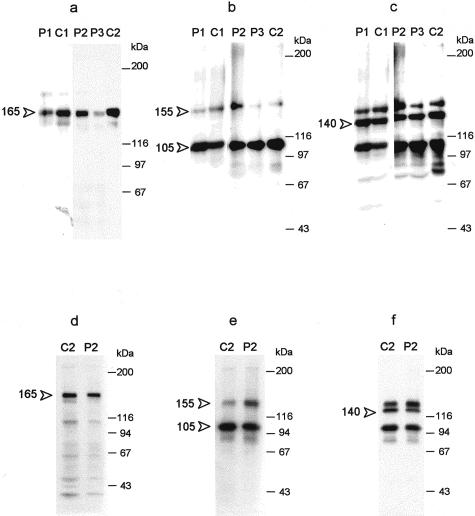

Besides being involved in migration, cellular interactions with the ECM play an important role in the elaboration, deposition, and organization of extracellular proteins.30,31 The major ECM ligand for NHKs is laminin 5, which undergoes a series of processing steps critical for its maturation, deposition, and function.32–34 The processing of soluble laminin 5 was examined by immunoblotting of the culture media of NHKs and C17−/− keratinocytes. Both types of media contained the semiprocessed (165 kd) α3A chain (Figure 7a), the unprocessed (155 kd), and processed (105 kd) forms of the γ2 chain (Figure 7b) and the 140-kd β3 chain (Figure 7c). Analysis of insoluble laminin 5 by immunoblotting of the material associated with the cell layers also showed the same processing in NHKs and C17−/− keratinocytes (Figure 7; d to f). In addition, these data indicate that NHKs and C17−/− keratinocytes secrete and deposit laminin 5 in equivalent quantities. The deposition of laminin 5 in the cell layers was examined by immunostaining and confocal laser-scanning microscopy. Laminin 5 was deposited in a concentrated pattern underneath and in the vicinity of NHKs (Figure 8, a and b; arrowheads in b). In contrast, in the cultures of C17−/− keratinocytes laminin 5 was deposited over larger areas and scattered away from the cells (Figure 8; c to h). In addition, tracks of laminin 5 were frequently observed in these cultures (Figure 8; c, e, and g; arrows), indicating that C17−/− keratinocytes had moved from one place to another leaving behind paths printed with laminin 5. Observation at higher magnification revealed that laminin 5 was concentrated in distinctly organized waves underneath or close to NHKs (Figure 8b; arrowheads), while it was scattered as a lace-like meshwork extending away from C17−/− keratinocytes (Figure 8; d, f, and h; arrowheads). Thus, in the absence of collagen XVII, laminin 5 is aberrantly deposited in the cell layers although it is still correctly processed. Moreover, the occurrence of scattered and track-like deposition of laminin 5 by C17−/− keratinocytes again reflects a motility higher than NHKs.

Figure 7.

NHKs and C17−/− keratinocytes produce and process laminin 5 similarly. The media (a–c) or cell extracts (d–f) of NHKs (C1, C2) and cells from nJEB patients (P1, P2, P3) were fractionated by SDS-PAGE, electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and immunoblotted with BM165 (a, d) or D4B5 (b, e) against the laminin α3 or γ2 chains, respectively. The blots shown in b and e were reblotted with a goat Ab against a C-terminal peptide of the laminin β3 chain (c, f). Molecular weight markers are indicated at the right of the blots. Note that similar amounts of the processed α3 chain (165 kd, arrowhead in a and d), the unprocessed and processed γ2 chain (155 and 105 kd, arrowheads in b and e) and the β3 chain (140 kd, arrowhead in c and f) are present in NHKs and C17−/− keratinocytes.

Figure 8.

Scattered deposition of laminin 5 by C17−/− keratinocytes. NHKs (a, b) and keratinocytes of nJEB patients (P1, c and d; P2, e and f; P3 g and h) were double stained for laminin 5 (mAb BM165) and fibrillar actin. Laser-scanning microscopy images at low and high magnification recorded at the interface between cells and the culture support show the superimposed stainings of laminin 5 (red) and fibrillar actin (green) used to visualize the cell bodies. Laminin 5 is deposited by NHKs in well-limited areas (a), in the typical belt-like manner, and exclusively in the close vicinity of cells (b, arrowheads). Keratinocytes from nJEB patients deposit laminin 5 in a lacy manner underneath and away from the cells (d, f, h, arrowheads) and leave laminin 5-rich paths on the culture support (c, e, and g, arrows). Scale bars: 100 μm (a, c, e, g); 50 μm (b, d, f, h).

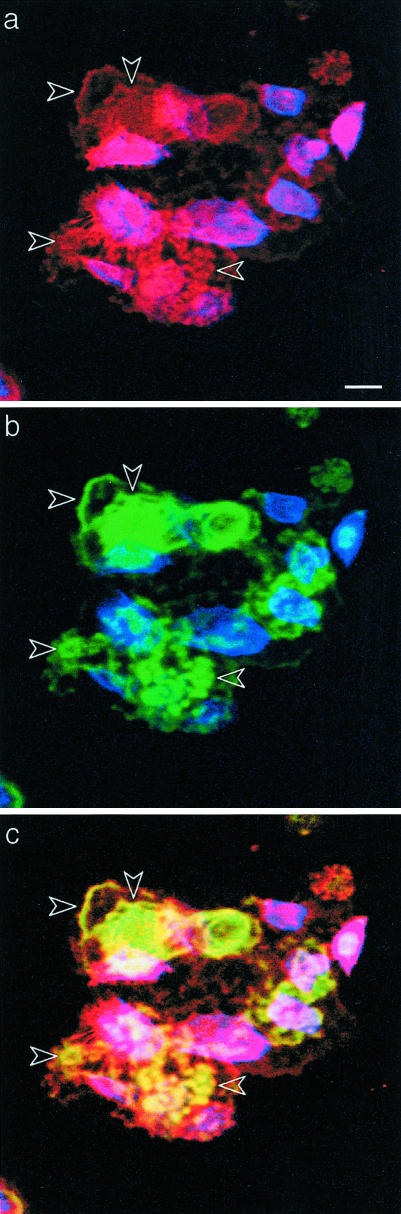

Collagen XVII Co-Distributes with Laminin 5 in the ECM of NHKs

The aberrant deposits of laminin 5 by C17−/− keratinocytes suggests that collagen XVII participates in the organization of laminin 5 in the matrix. Triple immunostaining of collagen XVII, laminin 5, and fibrillar actin to visualize cell bodies revealed that collagen XVII (Figure 9a) and laminin 5 (Figure 9b) co-distribute not only underneath the cells but also in cell-free deposits (Figure 9c). The positive collagen XVII staining in the extracellular compartment could reflect the presence of the shed ectodomain. This was confirmed by immunoblotting of the material bound to the culture support after NHKs were released by deoxycholate. This fraction contained both the full-length form (180 kd) and the shed (120 kd) ectodomain of collagen XVII (Figure 10). The extracellular co-localization of collagen XVII and laminin 5 raised the possibility of a direct interaction between the two proteins.

Figure 9.

Collagen XVII and laminin 5 co-distribute in the matrix of NHKs. NHKs were sequentially stained with NC16a against collagen XVII (a, red), BM165 against laminin 5 (b, green) followed by appropriate fluorochrome-conjugated second Abs and phalloidin coumarin phenyl isothiocyanate to delineate the cell bodies (a, b; blue). Two photon-scanning microscopy images were recorded at the cell/substrate interface. Collagen XVII (a, red) and laminin 5 (b, green) are present underneath the cells (blue) and in the ECM left by cells on the culture support. Superimposition of the three fluorochromes (c) shows that collagen XVII and laminin 5 co-distribute in cell-free deposits. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Figure 10.

Deoxycholate-insoluble forms of collagen XVII are present in the ECM of NHKs. The medium of NHKs was collected and the cell layer was extracted by successive incubations with 0.5% sodium deoxycholate. The detergent-insoluble material was resuspended into Laemmli buffer containing 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol and fractionated by SDS-PAGE. After electrophoretic transfer to nitrocellulose, immunoblotting with Abs against collagen XVII was used to detect full-length (180 kd) and shed (120 kd) forms of collagen XVII (arrows). Lane 1, cell layer, deoxycholate extract; lanes 2 and 3, deoxycholate-insoluble matrix; lane 4, medium.

Direct Interaction between Laminin 5 and the C-Terminus of Collagen XVII

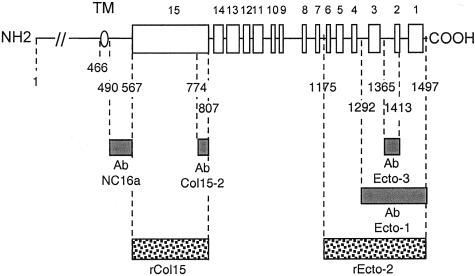

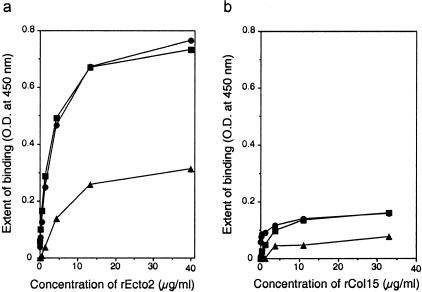

To test whether collagen XVII directly binds to laminin 5, we performed protein-protein interaction assays. Binding of recombinant collagen XVII fragments was detected by ELISA using Abs that specifically recognize the fragments. One fragment, rCol15, represents the largest N-terminal collagenous domain and the other, rEcto2, spans the six most C-terminal collagenous and noncollagenous domains (Figure 11). Ab Col15-2 and Ab Ecto3 react specifically with rCol15 and rEcto2, respectively, and do not cross-react with each other or with laminin 1 or laminin 5 (not shown). In protein-protein interaction assays, rEcto2 distinctly binds to laminin 5 in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 12a) whereas the binding of the fragment to laminin 1 was of much lower amplitude (Figure 12a). In comparison, the binding of rCol15 to laminin 1 or laminin 5 was marginal (Figure 12b). These results demonstrate that the C-terminal region of collagen XVII has a distinct affinity for laminin 5.

Figure 11.

Representation of collagen XVII and mapping of the reagents used in the study. The ectodomain of collagen XVII contains 15 collagenous (white boxes) and 16 noncollagenous (black lines) segments. The oval marks the transmembrane domain (TM). Dotted boxes correspond to the recombinant fragments rEcto2 and rCol15 and the gray boxes indicates previously described domain-specific Abs11,21 used in this study.

Figure 12.

The C-terminal domain of collagen XVII binds to laminin 5. Multiwell plates coated with laminin 1 (triangles) or two different batches of laminin 5 (squares and circles) were incubated with increasing concentrations of rEcto2 (a) or rCol15 (b) recombinant fragments. Binding of the fragments was detected by ELISA using domain-specific Ab Ecto3 and Ab Col15-2, respectively, followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated second Abs and color reaction. A distinct binding is detected for rEcto2 on laminin 5 coats only.

Discussion

Collagen XVII is one of the components of HDs, structures securing basal keratinocytes to the underlying BM in the skin. The intracellular portion of collagen XVII is in the cytoplasmic plaque of HDs and the ectodomain is in the anchoring filaments connecting HDs to the lamina densa of the BM. Collagen XVII is predicted to contribute to the stability of HDs because lack of cohesion between dermis and epidermis is the hallmark of inborn and acquired disorders targeting collagen XVII. Autoantibodies against collagen XVII ectodomain in bullous pemphigoid11 or null mutations in the COL17A1 gene in nJEB,12,13 lead to disruption of the anchoring filaments and subepidermal blisters. In contrast, deletion of only the intracellular domain of collagen XVII leaves the anchoring filaments intact and causes epidermolysis bullosa simplex, ie, intrakeratinocyte fracture.15 It suggests that the cytoplasmic and ectodomain of collagen XVII may have separate functions and that solely the ectodomain is important for the formation and the stability of the anchoring filaments tethering basal keratinocytes to the underlying BM. The molecular mechanism and the extracellular interaction(s) endowing the ectodomain with such a function have remained elusive.

Absence of collagen XVII has marked consequences on cell behavior because C17−/− keratinocytes have a migratory phenotype, a property appearing to be intrinsic to the cells because they develop lamellipodia on different substrates. It is well established that adhesion of NHKs to laminin 5 requires the recruitment of α3β1 integrins in transient focal adhesions, followed by the clustering of α6β4 integrins and the formation HD-like structures.23,25,26 As for NHKs, adhesion of C17−/− keratinocytes to laminin 5 is mediated by α3β1 integrins, indicating that collagen XVII is not needed at this point. In the following step, targeting of α6β4 integrins to cell matrix contacts occurs for both types of cells, however, and in contrast to NHKs, it does not lead to immobilization of C17−/− keratinocytes. In vivo, HD integrity is associated with stable anchorage of the keratinocytes whereas HD disassembly is required for keratinocyte migration. In particular, absence of the integrin β4 subunit is not compatible with HD formation in vivo35,36 and increased migration has been observed in vitro for keratinocytes lacking the integrin β4 subunit or expressing truncation mutants of it37,38 or lacking its laminin 5 ligand.39 Interactions between the cytoplasmic domain of the integrin β4 subunit and plectin have been shown to be sufficient for the nucleation of HD-like structures in vitro and collagen XVII is integrated at a later stage by aggregation of its N-terminus to the intracellular domain of the integrin β4 subunit.5,40 Thus integration of collagen XVII in the keratinocyte attachment complexes is likely to represent one of the final steps in the sequence of events regulating migration. Moreover, collagen XVII is still targeted to the ventral surface of basal keratinocytes in the epidermis of humans or mice with a deletion of the integrin α6 or β4 subunit35–37,40,41 or expressing an integrin β4 subunit without its cytoplasmic domain.42,43 Furthermore, deletion of the integrin β4 subunit does not prevent laminin 5 from incorporating into anchoring filaments.35 The above observations imply that in the absence of interactions between laminin 5 and α6β4 integrins, collagen XVII is targeted to the basal cell membrane independently of its binding to the cytoplasmic domain of the integrin β4 subunit. A likely explanation, provided by our study, is that collagen XVII is targeted to cell-substrate contacts by binding to laminin 5.

To strengthen this hypothesis, we could show that the C-terminus of the ectodomain of collagen XVII has affinity for laminin 5 and that both proteins co-distribute in the ECM of NHKs. This agrees well with their in vivo co-localization in anchoring filaments.7 The presence of the 120-kd collagen XVII ectodomain in the deoxycholate-insoluble matrix of cultured NHKs (this report) or in cutaneous tissue3 strongly supports the notion of a stable association of the domain with the ECM. The supramolecular organization of BMs requires multiple and stable interactions between constituting molecules, including laminins.44 Laminin 5, however, does not self-associate like other laminins and its binding to scaffolding proteins, such as collagens, is likely to be necessary for its integration in the BM architecture.45 It has been proposed that anchoring filaments are tethered to the stromal compartment by an interaction between laminin 5 and collagen VII.46,47 This, however, does not seem to be necessary to maintain the integrity of anchoring filaments because they are intact in the skin of patients with dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa who lack collagen VII.48 Laminin 5 deposited by C17−/− keratinocytes is not concentrated as in NHKs, although it is similar in terms of quantity, chain composition, and immunological reactivity toward several different Abs. In addition, processing of laminin 5, which is needed for its integration in the BM,32–34 was not altered in C17−/− keratinocytes, excluding the possibility that the scattered deposition of laminin 5 is caused by a deficient cleavage of the molecule. Our results rather suggest that collagen XVII is needed for the correct organization of the laminin 5 matrix. Collagen XVII may therefore have a dual role, one in the formation of HDs through its intracellular domain interacting with hemidesmosomal proteins and one in the establishment of anchoring filaments through binding of its ectodomain to laminin 5, an event that may control cell motility and cell arrest. Moreover, collagen XVII may contain additional cryptic activities because one of its fragments, Col15, induces cell adhesion and migration after denaturation.21,49 Regulation of cell migration by collagen XVII was suggested by studies showing that during skin wound healing collagen XVII is diffusely distributed within the cytoplasm of keratinocytes forming the leading edge of the migration sheet while it is located along the basal membrane of the cells in stationary epithelium.50 We recently showed that increased shedding of the ectodomain of collagen XVII correlates with decreased cell motility and that addition of the ectodomain to migrating cells inhibits their migration.4 Together these results strongly argue for an inhibition of keratinocyte migration by collagen XVII and we anticipate that incorporation of the ectodomain of collagen XVII in the laminin 5-rich matrix leads to stabilization of the substrate and cell immobilization.

An optimum in adhesion strength is required for cell migration, so that too weak adhesion is inadequate for cell traction whereas too strong adhesion is incompatible with cell deadhesion required for migration.51 The lack of a strong adhesion of C17−/− keratinocytes in vitro, reflected by their higher motility compared to controls, agrees well with the weakening in the anchorage of basal keratinocytes to the BM and the formation of blisters in vivo in nJEB patients despite the presence of laminin 5.12,13 The role of collagen XVII for the stabilization of epithelial cells on their ECM in vitro provides an explanation for the lack of cohesion of the dermal-epidermal junction in nJEB. Under these conditions, interactions between laminin 5 and α6β4 integrins are not sufficient to maintain the basal keratinocytes firmly attached to the BM and, consequently, laminin 5 remains in the blister floor whereas the integrins separate into the roof. We speculate that in nJEB patients the formation of blisters results from the absence of the stabilizing interaction between laminin 5 and collagen XVII. Indeed patients lacking laminin 5 have a more severe phenotype probably because they lack interactions of laminin 5 with both integrins and collagen XVII.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. R. E. Burgeson, E. Kohfeldt, K. Kühn, U. Mayer, R. Timpl, and D. Vestweber for gifts of reagents; Mrs. Margit Schubert, Monika Pesch, and Anja Mattila for excellent technical assistance; and Dr. Francesco Rivero for his valuable help with two photon microscopy.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Prof. Monique Aumailley, Institute for Biochemistry II, Joseph-Stelzmann-Str. 52, 50931 Köln, Germany. E-mail: aumailley@uni-koeln.de.

Supported by the Academy of Finland (to K.T.), the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (to K.T.), the Oulu University Hospital (to K.T.), the European Community (EU contract QLRT-2000-02007 to L.B.-T.), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Br 1475/6-2 and SFB 293/B3 to L.B.-T., and AU 86/5-3 and AU 86/8-1 to M.A.), and the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (01GM0301 to L.B.-T. and M.A.).

M.A. is a researcher of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique at the University of Cologne.

K.T. and L.T. contributed equally to this work.

References

- Fuchs E, Yang Y. Crossroads on cytoskeletal highways. Cell. 1999;98:547–550. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäcke H, Schumann H, Hammami-Hauasli N, Raghunath R, Bruckner-Tuderman L. Two forms of collagen XVII in keratinocytes. A full-length transmembrane protein and a soluble ectodomain. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25937–25943. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirako Y, Usukura J, Uematsu U, Hashimoto T, Kitajima Y, Owaribe K. Cleavage of BP180, a 180-kDa bullous pemphigoid antigen, yields a 120-kDa collagenous extracellular polypeptide. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9711–9717. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzke CW, Tasanen K, Schäcke H, Zhou Z, Tryggvason K, Mauch C, Zigrino P, Sunnarborg S, Lee DC, Fahrenholz F, Bruckner-Tuderman L. Transmembrane collagen XVII, an epithelial adhesion protein, is shed from the cell surface by ADAMs. EMBO J. 2002;21:5026–5035. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster J, Geerts D, Favre B, Borradori L, Sonnenberg A. Analysis of the interactions between BP180, BP230, plectin and the integrin α6β4 important for hemidesmosome assembly. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:387–399. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkinson SB, Jones JC. The N terminus of the transmembrane protein BP180 interacts with the N-terminal domain of BP230, thereby mediating keratin cytoskeleton anchorage to the cell surface at the site of the hemidesmosome. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:277–286. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.1.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka S, Ishiko A, Masunaga T, Akiyama M, Owaribe K, Shimizu H, Nishikawa T. The extracellular domain of BPAG2 has a loop structure in the carboxy-terminal flexible tail in vivo. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:89–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousselle P, Lunstrum GP, Keene DR, Burgeson RE. Kalinin: an epithelium-specific basement membrane adhesion molecule that is a component of anchoring filaments. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:567–576. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.3.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giudice GJ, Emery DJ, Diaz LA. Cloning and primary structural analysis of the bullous pemphigoid autoantigen BP180. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;99:243–250. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12616580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Areida SK, Reinhardt DP, Müller PK, Fietzek PP, Köwitz J, Marinkovich MP, Notbohm H. Properties of the collagen type XVII ectodomain. Evidence for N- to C-terminal triple helix folding. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1594–1601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008709200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumann H, Baetge J, Tasanen K, Wojnarowska F, Schäcke H, Zillikens D, Bruckner-Tuderman L. The shed ectodomain of collagen XVII/BP180 is targeted by autoantibodies in different blistering skin diseases. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:685–695. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64772-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonkman MF, de Jong MC, Heeres K, Pas HH, van der Meer JB, Owaribe K, Martinez de Velasco AM, Niessen CM, Sonnenberg A. 180-kD bullous pemphigoid antigen (BP180) is deficient in generalized atrophic benign epidermolysis bullosa. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:1345–1352. doi: 10.1172/JCI117785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JA, Gatalica B, Christiano AM, Li K, Owaribe K, McMillan JR, Eady RA, Uitto J. Mutations in the 180-kD bullous pemphigoid antigen (BPAG2), a hemidesmosomal transmembrane collagen (COL17A1), in generalized atrophic benign epidermolysis bullosa. Nat Genet. 1995;11:83–86. doi: 10.1038/ng0995-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leusden MR, Pas HH, Gedde-Dahl T, Jr, Sonnenberg A, Jonkman MF. Truncated type XVII collagen expression in a patient with non-herlitz junctional epidermolysis bullosa caused by a homozygous splice-site mutation. Lab Invest. 2001;81:887–894. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber M, Floeth M, Borradori L, Schäcke H, Rugg EL, Lane B, Frenk E, Hohl D, Bruckner-Tuderman L. Deletion of the cytoplasmatic domain of BP180/collagen XVII causes a phenotype with predominant features of epidermolysis bullosa simplex. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:185–192. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatalica B, Pulkkinen L, Li K, Kuokkanen K, Ryynänen M, McGrath J, Uitto J. Cloning of the human type XVII collagen gene (COL17A1), and detection of novel mutations in generalized atrophic benign epidermolysis bullosa. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:352–365. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumann H, Hammami-Hauasli N, Pulkkinen L, Mauviel A, Küster W, Lüthi U, Owaribe K, Uitto J, Bruckner-Tuderman L. Three novel homozygous point mutations and a new polymorphism in the COL17A1 gene: relation to biological and clinical phenotypes of junctional epidermolysis bullosa. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:1344–1353. doi: 10.1086/515463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floeth M, Fiedorowicz J, Schäcke H, Hammami-Hauasli N, Owaribe L, Trüeb RM, Bruckner-Tuderman L. Novel homozygous and compound heterozygous COL17A1 mutations associated with junctional epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:528–533. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruckner-Tuderman L, Nilssen O, Zimmermann DR, Dours-Zimmermann MT, Kalinke DU, Gedde-Dahl T, Jr, Winberg JO. Immunohistochemical and mutation analyses demonstrate that procollagen VII is processed to collagen VII through removal of the NC-2 domain. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:551–559. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.2.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousselle P, Aumailley M. Kalinin is more efficient than laminin in promoting adhesion of primary keratinocytes and some other epithelial cells and has a different requirement for integrin receptors. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:205–214. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.1.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasanen K, Eble JA, Aumailley M, Schumann H, Baetge J, Tu H, Bruckner P, Bruckner-Tuderman L. Collagen XVII is destabilized by a glycine substitution mutation in the cell adhesion domain Col15. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3093–3099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aumailley M, Wiedemann H, Mann K, Timpl R. Binding of nidogen and the laminin-nidogen complex to basement membrane collagen type IV. Eur J Biochem. 1989;184:241–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter WG, Ryan MC, Gahr PJ. Epiligrin, a new cell adhesion ligand for integrin α3β1 in epithelial basement membranes. Cell. 1991;65:599–610. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90092-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams JC. Regulation of protrusive and contractile cell-matrix contacts. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:257–265. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter WG, Kaur P, Gil SG, Gahr PJ, Wayner EA. Distinct functions for integrins α3β1 in focal adhesions and α6β4/bullous pemphigoid antigen in a new stable anchoring contact (SAC) of keratinocytes: relation to hemidesmosomes. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:3141–3154. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.6.3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchisio PC, Bondanza S, Cremona O, Cancedda R, De Luca M. Polarized expression of integrin receptors (α6β4, α2β1, α3β1, and αvβ5) and their relationship with the cytoskeleton and basement membrane matrix in cultured human keratinocytes. J Cell Biol. 1991;112:761–773. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.4.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regen CM, Horwitz AF. Dynamics of β1 integrin-mediated adhesive contacts in motile fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:1347–1359. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.5.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palecek SP, Huttenlocher A, Horwitz AF, Lauffenburger DA. Physical and biochemical regulation of integrin release during rear detachment of migrating cells. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:929–940. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.7.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirfel G, Rigort A, Borm B, Schulte C, Herzog V. Structural and compositional analysis of the keratinocyte migration track. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2003;55:1–13. doi: 10.1002/cm.10106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aumailley M, Pesch M, Tunggal L, Gaill F, Fässler R. Altered synthesis of laminin 1 and absence of basement membrane component deposition in β1 integrin-deficient embryoid bodies. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:259–268. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Harrison D, Carbonetto S, Fässler R, Smyth N, Edgar D, Yurchenco PD. Matrix assembly, regulation, and survival functions of laminin and its receptors in embryonic stem cell differentiation. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:1279–1290. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfinger LE, Stack MS, Jones JC. Processing of laminin-5 and its functional consequences: role of plasmin and tissue-type plasminogen activator. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:255–265. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.1.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnoux-Palacios L, Allegra M, Spirito F, Pommeret O, Romero C, Ortonne JP, Meneguzzi G. The short arm of the laminin γ2 chain plays a pivotal role in the incorporation of laminin 5 into the extracellular matrix and in cell adhesion. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:835–850. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.4.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunggal L, Ravaux J, Pesch M, Smola H, Krieg T, Gaill F, Sasaki T, Timpl R, Mauch C, Aumailley M. Defective laminin 5 processing in cylindroma cells. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:459–468. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64865-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling J, Yu QC, Fuchs E. β4 integrin is required for hemidesmosome formation, cell adhesion and cell survival. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:559–572. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.2.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Neut R, Krimpenfort P, Calafat J, Niessen CM, Sonnenberg A. Epithelial detachment due to absence of hemidesmosomes in integrin β4 null mice. Nat Genet. 1996;13:366–369. doi: 10.1038/ng0796-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niessen CM, van der Raaij-Helmer MH, Hulsman EH, van der Neut R, Jonkman MF, Sonnenberg A. Deficiency of the integrin β4 subunit in junctional epidermolysis bullosa with pyloric atresia: consequences for hemidesmosome formation and adhesion properties. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:1695–1706. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.7.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geuijen CAW, Sonnenberg A. Dynamics of the α6β4 integrin in keratinocytes. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:3845–3858. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-01-0601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnoux-Palacios L, Vailly J, Durand-Clement M, Wagner E, Ortonne JP, Meneguzzi G. Functional re-expression of laminin-5 in laminin-γ2-deficient human keratinocytes modifies cell morphology, motility, and adhesion. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18437–18444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nievers MG, Kuikman I, Geerts D, Leigh IM, Sonnenberg A. Formation of hemidesmosome-like structures in the absence of ligand binding by the α6β4 integrin requires binding of HD1/plectin to the cytoplasmic domain of the β4 integrin subunit. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:963–973. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.6.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzzi L, Gagnoux-Palacios L, Pinola M, Belli S, Meneguzzi G, D’Alessio M, Zambruno G. A homozygous mutation in the integrin α6 gene in junctional epidermolysis bullosa with pyloric atresia. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2826–2831. doi: 10.1172/JCI119474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murgia C, Blaikie P, Kim N, Dans M, Petrie HT, Giancotti FG. Cell cycle and adhesion defects in mice carrying a targeted deletion of the integrin β4 cytoplasmic domain. EMBO J. 1998;17:3940–3951. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.3940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonkman M, Pas H, Nijenhuis M, Kloosterhuis G, Steege G. Deletion of a cytoplasmic domain of integrin β4 causes epidermolysis bullosa simplex. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:1275–1281. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.19609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timpl R. Macromolecular organization of basement membranes. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:618–624. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aumailley M, El Khal A, Knöss N, Tunggal L. Laminin 5 processing and its integration into the ECM. Matrix Biol. 2003;22:49–54. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(03)00013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousselle P, Keene DR, Ruggiero F, Champliaud MF, van der Rest M, Burgeson RE. Laminin 5 binds the NC-1 domain of type VII collagen. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:719–728. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.3.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Marinkovich MP, Veis A, Cai X, Rao CN, O’Toole EA, Woodley DT. Interactions of the amino-terminal noncollagenous (NC1) domain of type VII collagen with extracellular matrix components. A potential role in epidermal-dermal adherence in human skin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14516–14522. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee PH. Pathology of the Skin. London: Gower Medical Publishing,; 1989 [Google Scholar]

- Nykvist P, Tasanen K, Viitasalo T, Kapyla J, Jokinen J, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Heino J. The cell adhesion domain of type XVII collagen promotes integrin-mediated cell spreading by a novel mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38673–38679. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102589200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gipson IK, Spurr-Michaud S, Tisdale A, Elwell J, Stepp MA. Redistribution of the hemidesmosome components α6β4 integrin and bullous pemphigoid antigens during epithelial wound healing. Exp Cell Res. 1993;207:86–98. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palecek SP, Loftus JC, Ginsberg MH, Lauffenburger DA, Horwitz AF. Integrin-ligand binding properties govern cell migration speed through cell-substratum adhesiveness. Nature. 1997;385:537–540. doi: 10.1038/385537a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]